Submitted:

01 April 2024

Posted:

02 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Morality versus Ethics in the Food Industry

Cultural Considerations in Food Ethics

Religious Foods

Food and Spirituality

Food Dynamics

GMOs, Ethics and Neophobia

Food Regulation

Food Safety and Quality Standards and Ethics

Food Fraud

Mouth—The Sacred Gateway to the Body

Significance of Oral Health in the Food Chain

Economic Implications and Ethics in the Prevention and/or Provision of Oral Health

Discussion

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- El Bilali, H.; Strassner, C.; Ben Hassen, T. Sustainable Agri-Food Systems: Environment, Economy, Society, and Policy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bindi, L.; Belliggiano, A. A Highly Condensed Social Fact: Food Citizenship, Individual Responsibility, and Social Commitment. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugo-Morin, D. R. Ethical Perspectives on Food Morality: Challenges, Dilemmas and Constructs. Food Ethics 2024, 9, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varzakas, T., G. Zakynthinos, C. Proestos. 2018b. Effect of food processing, quality, and safety with emphasis on kosher, halal, vegetarian, and GM food. Chapter 10. In: Preparation and Processing of Religious and Cultural Foods, Woodhead Publishing Series in Food Science, Technology and Nutrition, Edited by Md. Eaqub Ali and Nina Naquiah Ahmad Nizar. pp. 193-214. Elsevier.

- Monterrosa, E, E. Frongillo, A. Drewnowski, Saskia de Pee, and Stefanie Vandevijvere. 2020. Sociocultural Influences on food choices and implications for sustainable healthy diets. Food and Nutrition Bulletin 41 (2suppl): 59S-73S. [CrossRef]

- Wei, Yaoqi. Human morality: from evolutionary to future perspectives. Communications in Humanities Research 2023, 9, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askegaard, S., N. Ordabayeva, P. Chandon, T. Cheung, Z. Chytkova, Yann Cornil, Canan Corus, Julie Edell, Daniele Mathras, A. Franziska Junghans, D. Kristensen, I. Mikkonen, E. Miller, N. Sayarh, and C. Werle. Moralities in food and health research. Journal of Marketing Management 2014, 30, 1800–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez E, Llonch P, Turner PV. Applied Animal Ethics in Industrial Food Animal Production: Exploring the Role of the Veterinarian. Animals (Basel). 2022, 12, 678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldaco R, Hoehn D, Laso J, Margallo M, Ruiz-Salmón J, Cristobal J, Kahhat R, Villanueva-Rey P, Bala A, Batlle-Bayer L, Fullana-I-Palmer P, Irabien A, Vazquez-Rowe I. Food waste management during the COVID-19 outbreak: a holistic climate, economic and nutritional approach. Sci Total Environ. 2020, 742, 140524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, D., H. Smyth, D. Cozzolino, and M. Gidley. 2022. Holistc approach to effects of foods, human physiology, and psychology on food intake and appetite (satiation & satiety). Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. [CrossRef]

- Hargreaves, S. M., A. Raposo, Z. Saraiva, and R. Puppin. Vegetarian diet: An overview through the perspective of quality of life domains. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2021, 18, 4067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Traverso-Yepez, M. , & Hunter, K. (2016). From “Healthy Eating” to a Holistic Approach to Current Food Environments. Sage Open, 6(3). [CrossRef]

- Borgdorf, L. 2024. Book review: Josh Milburn’s just fodder: the ethics of feeding animals. Food Ethics.

- Milburn, J. 2024. Relational animal ethics (and why it isn’t easy). Food Ethics 9: 6. [CrossRef]

- Varzakas, T.; Smaoui, S. Global Food Security and Sustainability Issues: The Road to 2030 from Nutrition and Sustainable Healthy Diets to Food Systems Change. Foods 2024, 13, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruben, R., R. Cavatassi, L. Lipper, E. Smaling, and P. Winters. Towards food systems transformation—five paradigm shifts for healthy, inclusive and sustainable food systems. Food Security 2021, 13, 1423–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stein, A., and F. Santini. 2021. The sustainability of local food: a review for policy-makers. Review of Agricultural Food and Environmental Studies 103: 77–89. [CrossRef]

- Carolan, M. 2022. Ethical eating as experienced by consumers and producers: when good food meets good farmers. Journal of Consumer Culture 22 (1): 103–123. [CrossRef]

- Betancur, G. E. 2016. La ιtica y la moral: paradojas del ser humano. Revista CES Psicologia 9 (1): 109–121.

- Dasuky, S. 2010. Cuatro versiones de la ιtica y la moral [notas de clase]. Medellνn: Universidad Pontificia Bolivariana. http://cmap.upb.edu.co/rid=1GCFQ5KLN-T0G1NL-9W/cuatro%20versiones%20de%20la%20%C3%A9tica.pdf. (accessed on 12 March 2024).

- Huxley, T. H. 1911. Evolution and ethics. New York: D. Appleton and Company.

- Hauser, M. 2006. Moral minds: the nature of right and wrong. New York: Harper Perennial.

- de Waal, F. B. M. , & Aureli, F. (1996). Consolation, reconciliation, and a possible cognitive difference between macaques and chimpanzees. In A. E. Russon, K. A. Bard, & S. T. Parker (Eds.), Reaching into thought: The minds of the great apes (pp. 80–110). Cambridge University Press.

- Shaw, J. C. Plato’s Anti-hedonism and the 'Protagoras'. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015. viii, 222. ISBN 9781107046658.

- Lazari-Radek, K. D, and Singer P. 2017. Origins, utilitarianism: a very short introduction, very short introductions, online ed. Oxford Academic. [CrossRef]

- West, H. 2003. An introduction to Mill’s utilitarian ethics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Kant’s Moral Philosophy. First published Mon Feb 23, 2004; substantive revision Fri Jan 21, 2022. Available online: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/kant-moral/. (accessed on March 2024).

- Granja, D. M. Kant: conciencia reflexiva y proceso humanizador. Sociolσgica 2004, 19, 213–226. [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Cueto, F. , and A. Olsen. The multifaceted dimensions of food choice and nutrition. Nutrients 2020, 12, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Resnik, D. 2018. Moral Theory. In The Ethics of Research with Human Subjects. International Library of Ethics, Law, and the New Medicine, vol. 74 Cham: Springer. [CrossRef]

- Atteshli-Theotoki, P. 2023. The great voyage of the soul. Part I. Your wings to fly Part II. The Stoa Series, Cyprus.

- Botti, S., S. Iyengar, and A. McGill. Choice freedom. Journal of Consumer Psychology 2023, 33, 143–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouraqui, J.-P., D. Turck, A. Briend, D. Darmaun, A. Bocquet, F. Feillet, M.-L. Frelut, J.-P. Girardet, D. Guimber, R. Hankard, A. Lapillonne, N. Peretti, J.-C. Roze, U. Simioni, C. DuPont, the Committee on Nutrition of the French Society of Pediatrics. Religious dietary rules and their potential nutritional and health consequences. International Journal of Epidemiology 2021, 50, 12–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz, J. A. Derechos morales: concepto y relevancia. Isonomνa 2001, 15, 55–79. [Google Scholar]

- Kelsen, H. La doctrina del derecho natural y el positivismo juridico. Acadιmica Revista sobre enseρanza del Derecho 2008, 12, 183–198. [Google Scholar]

- Lugo-Morin, D. R. Frolich, and T. Magal-Royo. Relacion ser humano-naturaleza: debatiendo el Desarrollo sostenible desde la filosofνa de la ciencia. European Scientific Journal 2015, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Lugo-Morin, D. R. Restoring the food systems resilience through the dialogue of knowledge: a case study from Mexico. Forum for Development Studies 2023, 50, 183–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorichanaz, Tim. "A Compass for What Matters: Applying Virtue Ethics to Information Behavior" Open Information Science, vol. 7, no. 1, 2023, pp. 20220151. [CrossRef]

- Berti, E. 2008. Las razones de Aristσteles. Buenos Aires: Oinos.

- Durant, W. [1978]. 1994. Historia de la Filosofνa. La vida y el pensamiento de los mαs grandes filσsofos del mundo. Ciudad de Mιxico: Editorial Diana.

- Conroy, M. , Malik, A.Y., Hale, C. et al. Using practical wisdom to facilitate ethical decision-making: a major empirical study of phronesis in the decision narratives of doctors. BMC Med Ethics 22, 16 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Schroeder N. B.A., MORAL DILEMMAS IN CONTEMPORARY VIRTUE ETHICS. A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The Department of Philosophy and Religious Studies University of New Orleans, 2008 May 2011. Available online: chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://repository.lsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1640&context=gradschool_theses. Accessed March 2024.

- Smith M., B. (2017). Values, self and society: Toward a humanist social psychology. Routledge. 10.4324/9781351316682.

- Weber, E. T. (2008). Religion, public reason, and humanism: Paul Kurtz on fallibilism and ethics. Contemporary Pragmatism, 5(2), 131-147. Retrieved from https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/rodopi/cpm/2008/00000005/00000002/art00007.

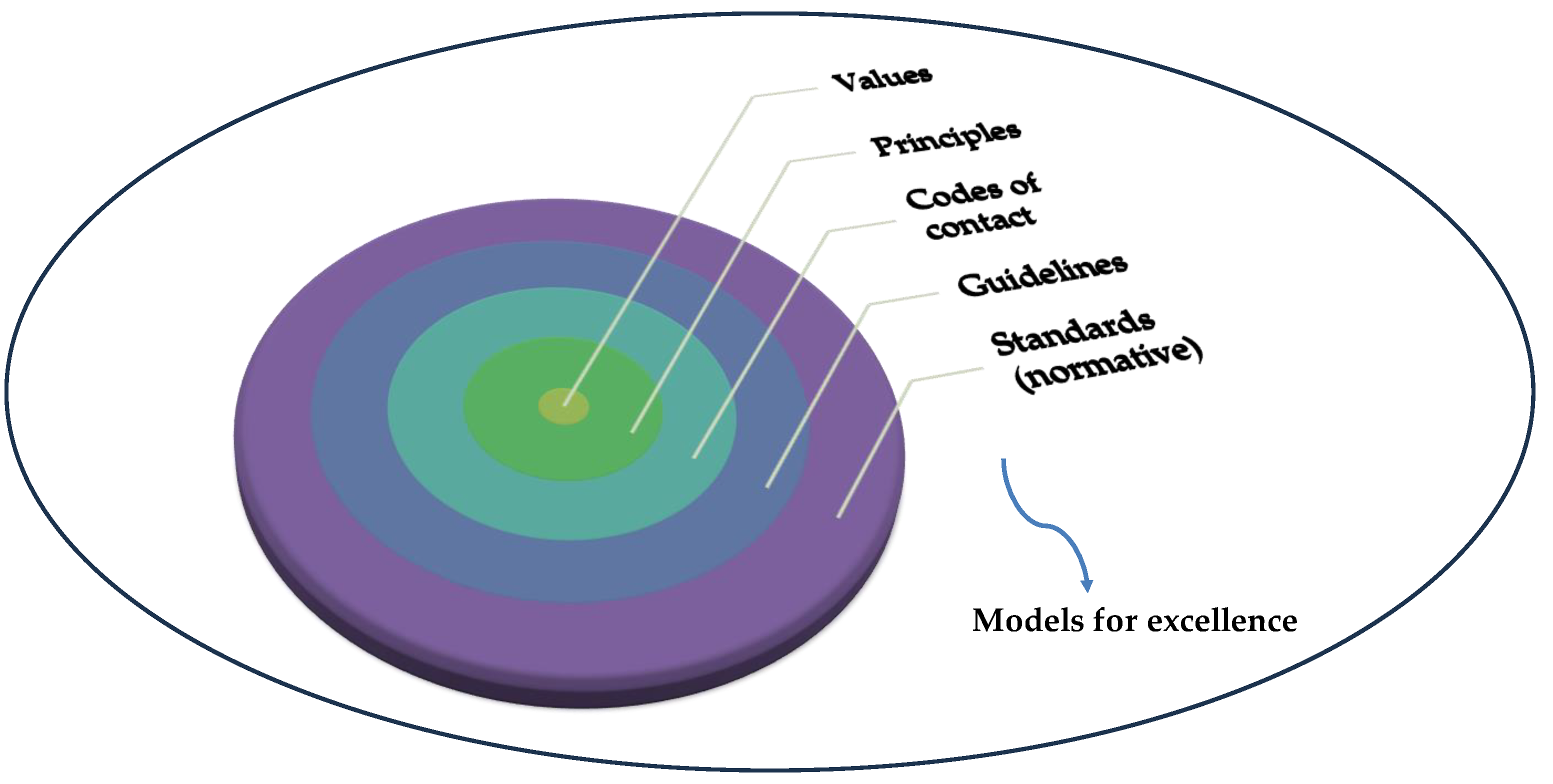

- Giannouli, V. 2024. Ethics and Ethical Values. Business Ethics in Healthcare: The Case of Greece. Source Title: Research Anthology on Business Law, Policy, and Social Responsibility. In book: Examining Ethics and Intercultural Interactions in International Relations Pages: 23. [CrossRef]

- Mayo, E. (2017). Values: How to bring values to life in your business. Routledge. 10.4324/9781351283847.

- Philosophical and Sociological Dictionary. (1995). (Vol. 1). Athens: Kapopoulos Publishing.

- Diamantopoulos, D. (2002). Modern dictionary of the basic concept of the material-technical, spiritual and ethical civilization. Athens: Patakis.

- Mohammadi, A. Vanaki Z. Memarian R. Fallahrafie R. A. (2019). Islamic and Western ethical values in health services management: A comparative study.International Journal of Nursing Knowledge, 30(4), 239–250. [CrossRef]

- Jackson, T. (2015). 15 Managing managers across cultures: Different values, different ethics. In WilkinsonA.TownsendK.SuderG. (Eds.), Handbook of Research on Managing Managers (pp. 283–306). Edward Elgar Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Pletz, J. Being Ethical. Nova Science Publishers Inc (27 October 1999).

- Harris J., R. (1990). Ethical values of individuals at different levels in the organizational hierarchy of a single firm.Journal of Business Ethics, 9(9), 741–750. [CrossRef]

- Kanungo, R. N. (2001). Ethical values of transactional and transformational leaders. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences/Revue Canadienne des Sciences de l'Administration, 18(4), 257-265. [CrossRef]

- Landau R. Osmo R. (2003). Professional and personal hierarchies of ethical principles.International Journal of Social Welfare, 12(1), 42–49. [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, J. (2013). Universal human rights in theory and practice. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Schwartz S., H. Bardi A. (2001). Value hierarchies across cultures taking a similarities perspective.Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 32(3), 268–290. [CrossRef]

- Curley, E. 1994. Spinoza Reader THE ETHICS AND OTHER WORKS. Benedict de Spinoza. Princeton University Press.

- Costa Depra, M., R. Rodrigues Dias, L. Queiroz Zepka, Eduardo Jacob-Lopes. 2022. Building cleaner production: How to anchor sustainability in the food production chain? Environmental Advances 9, 100295. [CrossRef]

- Vikram R. Niranjan, Vikas Kathuria, Venkatraman J and Arpana Salve. Oral Health Promotion: Evidences and Strategies. Published: 20 September 2017. From Insights into Various Aspects of Oral Health. Edited by Jane Manakil. [CrossRef]

- Viles, E., F. Kalemkerian, Jose Arturo Garza-Reyes, Jiju Antony, Javier Santos. Theorizing the Principles of Sustainable Production in the context of Circular Economy and Industry 4.0. Sustainable Production and Consumption. Volume 33, September 2022, Pages 1043-1058. [CrossRef]

- Mastos, T.; Gotzamani, K. Sustainable Supply Chain Management in the Food Industry: A Conceptual Model from a Literature Review and a Case Study. Foods 2022, 11, 2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mardian, Yan, Kathryn Shaw-Shaliba, Muhammad Karyana, and Chuen-Yen. Lau. 2021. Sharia (Islamic Law) perspectives of COVID-19 vaccines. Frontiers in Tropical Diseases 2: 788188. [CrossRef]

- Nungesser F, Winter M. Meat and social change: Sociological perspectives on the consumption and production of animals. OZS Osterr Z Soziol. 2021, 46, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murcott, Anne. 1982. The cultural significance of food and eating. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society 41: 203–210. [CrossRef]

- Tranchant, J.-P. , Gelli, A., Bliznashka, L., Diallo, A.S., Sacko, M., Assima, A., Siegel, E.H., Aurino, E., Masset, E., 2019. The impact of food assistance on food insecure populations during conflict: Evidence from a quasi-experiment in Mali. World Development 119, 185–202.

- Mary, S. , 2022. A replication note on humanitarian aid and violence. Empirical Economics 62, 14651494.

- Koppenberg M.; Ashok K. Mishra Stefan Hirsch. Food Aid and Violent Conflict: A Review of Literature. IZA DP No. 16574. November 2023. Available online: chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://docs.iza.org/dp16574.pdf.

- Nunn, N. , Qian, N., US Food Aid and Civil Conflict. American Economic Review 2014, 104, 16301666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mary, S. , Mishra, A.K., Humanitarian food aid and civil conflict. World Development 2020, 126, 104713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunn, N. , Qian, N., 2016. The Determinants of Food-Aid Provisions to Africa and the Developing World, in: Edwards, S., Johnson, S., Weil, D.N. (Eds.), African Successes Volume IV: Sustainable Growth. National Bureau of Economic Research, pp. 161–178.

- Christian, P. , Barrett, C.B., 2017. Revisiting the Effect of Food Aid on Conflict: A Methodological Caution. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 8171.

- Christian, P. , Barrett, C.B., 2021. Spurious Regressions and Panel IV Estimation: Revisiting the Causes of Confict. http://barrett.dyson.cornell.edu/files/papers/Christian%20&%20Barrett%20June%202021%20 resubmitted%20with%20appendices.pdf. (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Feeley-Harnik, G. , Religion and food: an anthropological perspective. J. Am. Acad. Relig. 1995, 63, 565–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casanova, J. 2010. “Interdisciplinary Challenges to the Study of Religion.” In The Challenges of Religion, edited by A. Bäckström and P. Petterson, 33–37. Uppsala (Sweden): Uppsala University.

- Cohen A. You can learn a lot about religion from food. Current Opinion in Psychology Volume 40, August 2021, Pages 1-5. [CrossRef]

- Markowitz, F. , & Nir Avieli (2022) Eating religiously: food and faith in the 21st century, Food, Culture & Society, 25:4, 640-646. [CrossRef]

- Pomeranz, J. , and K. Brownell. Portion sizes and beyond — government’s legal authority to regulate food-industry practices. The New England Journal of Medicine 2012, 367, 1383–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Garcia, R. 2016. Food law in Mexico: regulatory framework and public policy strategies to address the obesity crisis in Latin America. In International food law and policy, ed. G. Steier and K. Patel. Cham: Springer. [CrossRef]

- Sarri, K.O. , Linardakis, M.K., Bervanaki, F.N., Tzanakis, N.E., Kafatos, A.G., Greek Orthodox fasting rituals: a hidden characteristic of the Mediterranean diet of Crete. British Journal of Nutrition 2004, 92, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varzakas, T., P. Kandylis, D. Dimitrellou, C. Salamoura, G. Zakynthinos, C. Proestos. 2018a. Innovative and fortified food: Probiotics, prebiotics, GMOs, and superfood., Chapter 6. In: Preparation and Pro-cessing of Religious and Cultural Foods, Woodhead Publishing Series in Food Science, Technology and Nutrition Edited by Md. Eaqub Ali and Nina Naquiah Ahmad Nizar. pp. 67-129 Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Meigs. A.S. Food, Sex, and Pollution: A New Guinea Religion. (1991).

- Hopkins, E.W. , The buddhistic rule against eating meat. J. Am. Orient. Soc. 1906, 27, 455–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarao, K.T.S. , 2008. Buddhist attitude towards meat-eating. Tibet J. 33 91-.

- Nath, J. , “God is a vegetarian”: the food, health and bio-spirituality of Hare Krishna, Buddhist and Seventh-day Adventist devotees. Health Sociol. Rev. 2010, 19, 356–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testoni, I. , Ghellar, T., Rodelli, M., Cataldo, L.D., Zamperini, A., Representations of death among italian vegetarians: an ethnographic research on environment, disgust and transcendence. Eur. J. Psychol. 2017, 13, 378–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzworksy, R. , From the marketplace to the dinner plate: the economy, theology, and factory farming. J. Bus. Ethics 2001, 29, 177. [Google Scholar]

- Michopoulou, Eleni and Pijus Jauniškis. Exploring the relationship between food and spirituality: A literature review. International Journal of Hospitality Management 2020, 87, 102494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- .Arnett. L. D The Soul: A Study of Past and Present Beliefs.The American Journal of Psychology, Vol. 15, No. 2 (Apr., 1904), pp. 121-200 (80 pages). [CrossRef]

- Buser, J.K. , Parkins, R.A., Buser, T.J., 2014. Thematic analysis of the intersection of spirituality and eating disorder symptoms. J. Addict. Offender Couns. 35, 97–113. [CrossRef]

- Reicks, M. , Mills, J., Henry, H., 2004. Qualitative study of spirituality in a weight loss program: contribution to self-efficacy and locus of control. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 36, 13–19. [CrossRef]

- Patel, R. , Lycett, D., Coufopoulos, A., Turner, A., 2017a. A feasibility study of taste & see: a church based programme to develop a healthy relationship with food. Religions 8, 29. [CrossRef]

- Patel, R. , Lycett, D., Coufopoulos, A., Turner, A., 2017b. Moving forward in their journey: participants’ experience of taste & see, a church-based programme to develop a healthy relationship with food. Religions 8, 14. [CrossRef]

- Lafrance, A. , Loizaga-Velder, A., Fletcher, J., Renelli, M., Files, N., Tupper, K.W., 2017. Nourishing the spirit: exploratory research on Ayahuasca experiences along the continuum of recovery from eating disorders. J. Psychoactive Drugs 49, 427–435. [CrossRef]

- Savoldi, R., D. Polari, J. Pinheiro-da-Silva, P. F. Silva, B. Lobao-Soares, M. Yonamine, Fulvio A. M. Freire, and A. C. Luchiari. Behavioral Changes Over Time Following Ayahuasca Exposure in Zebrafish. Front Behav Neurosci. 2017, 11, 139. [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez-Clave, E. , Soler, J., Pascual, J.C., Elices, M., Franquesa, A., Valle, M., Alvarez, E., Riba, J., 2019. Ayahuasca improves emotion dysregulation in a community sample and in individuals with borderline-like traits. Psychopharmacology 236, 573–580. [CrossRef]

- Uthaug, M.V. , van Oorsouw, K., Kuypers, K.P.C., van Boxtel, M., Broers, N.J., Mason, N.L., Toennes, S.W., Riba, J., Ramaekers, J.G., 2018. Sub-acute and long-term effects of ayahuasca on affect and cognitive thinking style and their association with ego dissolution. Psychopharmacology 235, 2979–2989. [CrossRef]

- Re, T. , Palma, J., Martins, J.E., Simoes, M., Transcultural perspective on consciousness: traditional use of ayahuasca in psychotherapy in the 21st century in western world. Cosmos Hist. J. Nat. Soc. Philos. 2016, 12, 237. [Google Scholar]

- Dell, M.L. , Josephson, A.M., 2007. Religious and spiritual factors in childhood and adolescent eating disorders and obesity. South. Med. J. 100 628-.

- Matusek, J.A. , Knudson, R.M., 2009. Rethinking recovery from eating disorders: spiritual and political dimensions. Qual. Health Res. 19, 697–707. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Martin, B.C. , Gallego-Arjiz, B., 2018. Overeaters anonymous: a mutual-help fellowship for food addiction recovery. Front. Psychol. 9. [CrossRef]

- Exline, J.J. , Homolka, S.J., Harriott, V.A., 2016. Links with body image concerns, binging, and compensatory behaviours around eating. Ment. Health Relig. Cult. 19, 8–22. [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.-M. , Chan, C.K.Y., Reidpath, D.D., 2014. Faith, food and fettle: is individual and neighborhood Religiosity/Spirituality associated with a better diet? Religions 5, 801–813. [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.-M. , Chan, C., Reidpath, D., 2016. Religiosity, dietary habit, intake of fruit and vegetable, and vegetarian status among Seventh-Day Adventists in West Malaysia. J. Behav. Med. 39, 675–686. [CrossRef]

- Dittmann, K.A. , Freedman, M.R., 2009. Body awareness, eating attitudes, and spiritual beliefs of women practicing yoga. Eat. Disord. 17, 273–292. [CrossRef]

- 105. Neumark-Sztainer D, Watts AW, Rydell S. Yoga and body image: How do young adults practicing yoga describe its impact on their body image? Body Image. [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez-Moya, E. , Adenso-Díaz, B., Lozano, S., 2021. Analysis and vulnerability of the international wheat trade network. Food Security 13 (1), 113–128. [CrossRef]

- Machado, V. A., D. P. Auler, and R. Teixeira. Food safety in global supply chains: a literature review. Journal of Food Science 2020, 85, 883–891. [Google Scholar]

- Moosavi, J, A. Fathollahi-Fard, and M. Dulebenets. 2022. Supply chain disruption during the COVID-19 pandemic: recognising potential disruption management strategies. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 75: 102983. [CrossRef]

- Kemper, J., A. Kapetanaki, F. Spotswood, R. Rajshri, H. Hassen, A. Uzoigwe, and I. Fifita. 2023. Food practices adaptation: exploring the coping strategies of low-socioeconomic status families in times of disruption. Appetite 186: 106553. [CrossRef]

- Magano, N., H. Tuorila, and H. De Kock. 2023. Food choice drivers at varying income levels in an emerging economy. Appetite 189: 107001. [CrossRef]

- WHO. Food safety. 19 May 2022. Available online from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/food-safety.

- Fernandez, Antonio, and Claudia Paoletti. 2021. What is unsafe food? Change of perspective. Trends in Food Science & Technology 109: 725–728. [CrossRef]

- Çakmakçı, R.; Salık, M.A.; Çakmakçı, S. Assessment and Principles of Environmentally Sustainable Food and Agriculture Systems. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogiemwonyi, O. M. Tahir Jan. The correlative influence of consumer ethical beliefs, environmental ethics, and moral obligation on green consumption behavior. Resources, Conservation & Recycling Advances. Volume 19, November 2023, 200171. [CrossRef]

- Fallah Shayan, N.; Mohabbati-Kalejahi, N.; Alavi, S.; Zahed, M.A. Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as a Framework for Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR). Sustainability 2022, 14, 1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega Rodríguez, A.; Rodríguez-Oramas, C.; Sanjuán Velázquez, E.; Hardisson de la Torre, A.; Rubio Armendáriz, C.; Carrascosa Iruzubieta, C. Myths and Realities about Genetically Modified Food: A Risk-Benefit Analysis. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 2861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, S.; Inbar, Y.; Wirz, C.; Brossard, D.; Rozin, P. An Overview of Attitudes Toward Genetically Engineered Food. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2018, 38, 459–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rose, K.; Brossard, D.; Scheufele, D. Of Society, Nature, and Health: How Perceptions of Specific Risks and Benefits of Genetically Engineered Foods Shape Public Rejection. Environ. Commun. 2020, 14, 1017–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telem, R. , Wani, S. H., Singh, N., Nandini, R., Sadhukhan, R., Bhattacharya, S. & Mandal, N. Cisgenics-A Sustainable Approach for Crop Improvement. Current Genomics 2013, 14, 468. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Myskja, B. The Moral Difference between Intragenic and Transgenic Modification of Plants. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2006, 19, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ankeny, R.; Bray, H. Genetically Modified Food; Oxford Handbooks Online: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Schouten, H.J.; Krens, F.A.; Jacobsen, E. Cisgenic plants are similar to traditionally bred plants: International regulations for genetically modified organisms should be altered to exempt cisgenesis. EMBO Rep. 2006, 7, 750–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laros, F. J. M. & Steenkamp, J.-B. E. M. (2004). Importance of fear in the case of genetically modified food. Psychology and Marketing, 21(11), 889–908. Retrieved from. [CrossRef]

- Lieberman, S. , & Gray, T. (2008). GMOs and the Developing World: A Precautionary Interpretation of Biotechnology. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 10(3), 395-411. [CrossRef]

- Deane-Drummond, C. , Grove-White, R. & Szerszynski, B. Genetically modified theology: the religious dimensions of public concerns about agricultural biotechnology. Studies in Christian Ethics 2001, 14, 23–41. [Google Scholar]

- Gregorowius, D. , Lindemann-Matthies, P. & Huppenbauer, M. Ethical Discourse on the Use of Genetically Modified Crops: A Review of Academic Publications in the Fields of Ecology and Environmental Ethics. Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics 2012, 25, 265–293. [Google Scholar]

- Kaptan, G., Fischer, A. R. H., & Frewer, L. J. (2018). Extrapolating understanding of food risk perceptions to emerging food safety cases. Journal of Risk Research, 21(8), 996-1018. [CrossRef]

- Mielby, H., P. Sandøe and J. Lassen. 2013. The role of scientific knowledge in shaping public attitudes to GM technologies. Public Understanding of Science. 22(2) 155–168. [CrossRef]

- Robinson, E. L. (2013). Unnatural selections: the role of institutional confidence in consumer choice of genetically modified food in the United States. A Thesis. Washington, D.C. Availiable from: https://repository.library.georgetown.edu/bitstream/handle/10822/558604/Robinson_georgetown_0076M_12161.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- Schuppli, C. A., Molento, C. F. & Weary, D. M. (2013). Understanding attitudes towards the use of animals in research using an online public engagement tool. Public Understanding of Science.

- Wansink, B. , Tal, A. & Brumberg, A. (2014). Ingredient-based Food Fears and Avoidance: Antecedents and Antidotes. Food Quality and Preference.

- Siddiqui, S.A.; Asif, Z.; Murid, M.; Fernando, I.; Adli, D.N.; Blinov, A.V.; Golik, A.B.; Nugraha, W.S.; Ibrahim, S.A.; Jafari, S.M. Consumer Social and Psychological Factors Influencing the Use of Genetically Modified Foods—A Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilella-Vila, M. , Costa-Font, J. & Mossialos, E. (2005). Consumer involvement and acceptance of biotechnology in the European Union: a specific focus on Spain and the UK. International Journal of Consumer Studies. Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=psyh&AN=2005-07485-.

- Kim, S.-H. (2012). Testing Fear of Isolation as a Causal Mechanism: Spiral of Silence and Genetically Modified (GM) Foods in South Korea. International Journal of Public Opinion Research. WAPOR.

- Maria Antoniadou & Theodoros Varzakas (2021) Breaking the vicious circle of diet, malnutrition and oral health for the independent elderly, Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 61:19, 3233-3255. [CrossRef]

- Hwang H, Nam SJ. The influence of consumers' knowledge on their responses to genetically modified foods. GM Crops Food. 2021, 12, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uzogara, S.G. The impact of genetic modification of human foods in the 21st century: a review. Biotechnol. Adv. 2000, 18, 179–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faccio, E.; Guiotto Nai Fovino, L. Food Neophobia or Distrust of Novelties? Exploring Consumers’ Attitudes toward GMOs, Insects and Cultured Meat. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 4440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, R. F.; Arthington, J. D.; Staples, C. R.; Thatcher, W. W.; Lambof, G. C. . Effects of supplement type on performance, reproductive, and physiological responses of Brahman-crossbred females. J. Anim. Sci. 2007, 85, 2564–2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knight, J. G., Holdsworth, D. K. & Mather, D. W. (2008). GM food and neophobia: connecting with the gatekeepers of consumer choice. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. Retrieved from. [CrossRef]

- Varzakas, T. , and Tzanidis, T. 2016. Genetically Modified Foods: Risk Assessment, Legislation, Consumer Behavior, and Ethics. In: Caballero, B., Finglas, P., and Toldrá, F. (eds.) The Encyclopedia of Food and Health vol. 3, pp. 204-210. Oxford: Academic Press.

- Gargano D, Appanna R, Santonicola A, De Bartolomeis F, Stellato C, Cianferoni A, Casolaro V, Iovino P. Food Allergy and Intolerance: A Narrative Review on Nutritional Concerns. Nutrients. 2021 May 13;13(5):1638. [CrossRef]

- Gil-Humanes, J. , Piston, F.,Altamirano-Fortoul, R. Real,A.,Comino, I., Sousa,C., Rosell, C.M.etal. Reduced-gliadin wheat bread: analternative to the gluten-free diet. for consumers suffering gluten-related pathologies. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e90898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weale A. Ethical arguments relevant to the use of GM crops. N Biotechnol. 2010 Nov 30;27(5):582-7. [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, B.K.; Yu, C.Y.; Kim, W.-R.; Moon, H.-S.; Lee, J.; Kim, S.H.; Chung, I.M. Assessment of Benefits and Risk of Genetically Modified Plants and Products: Current Controversies and Perspective. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairbairn, M. , & Emily Reisman (2024) The incumbent advantage: corporate power in agri-food tech, The Journal of Peasant Studies. [CrossRef]

- Green, Jonathan, Michael Barrat, Michael Kinch, and Jeffrey Gordon. 2017. Food and microbiota in the FDA regulatory framework. Science 357 (6346): 39–40. [CrossRef]

- Van Eenennaam, Alison, Kevin Wells, and James Murray. 2019. Proposed U.S. regulation of geneedited food animals is not fit for purpose. npj Science of Food 3: 3. [CrossRef]

- Zwietering, M.H. 2015. Risk assessment and risk management for safe foods: assessment needs inclusion of variability and uncertainty, management needs discrete decisions. International Journal of Food Microbiology 213: 118–123. [CrossRef]

- Ververis, E., R. Ackerl, D. Azzollini, et al. 2020. Novel foods in the European Union: scientific requirements and challenges of the risk assessment process by the European Food Safety Authority. Food Research International 137: 109515. [CrossRef]

- Santeramo, F. , Gaetano, D. Carlucci, B. De Devitiis, et al. 2018. Emerging trends in European food, diets and food industry. Food Research International 104: 39–47. [CrossRef]

- Kearney, J. 2010. Food consumption trends and drivers. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London Series B Biological sciences 365 (1554): 2793–2807. [CrossRef]

- Little, Daniel. 2020. Governments as regulators. In A New Social Ontology of Government. Foundations of Government and Public Administration. Cham: Palgrave Pivot. [CrossRef]

- Rose, N., B. Reeve, and K. Charlton. 2022. Barriers and enablers for healthy food systems and environments: the role of local governments. Current Nutrition Reports 11: 82–93. [CrossRef]

- Mozaffarian, D., S. Angell, T. Lang, and J. Rivera. 2018. Role of government policy in nutrition—barriers to and opportunities for healthier eating. BMJ 361: k2426. [CrossRef]

- Kjaer, Poul, and Antje Vetterlein. 2018. Regulatory governance: rules, resistance and responsibility. Contemporary Politics 24 (5): 497–506. [CrossRef]

- Canfield, Matthew, Jessica Duncan, and Priscilla Claeys. 2021. Reconfiguring food systems governance: the UNFSS and the battle over authority and legitimacy. Development 64: 181–191. [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, M. , John Ejaz; Dixon, and Mellissa Wood. 2015. Public policies for improving food and nutrition security at different scales. Food Security 7: 393–403. [CrossRef]

- Malik, M. , Mahmood, F., Sarwar, N. et al. Ethical leadership: Exploring bottom-line mentality and trust perceptions of employees on middle-level managers. Curr Psychol 42, 16602–16617 (2023). [CrossRef]

- The economist. Leadership Ethics: Building Trust and Integrity in the Workplace. Last Updated: Oct 22, 2023, 09:14:00 PM IST. Available online: https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/jobs/c-suite/leadership-ethics-building-trust-and-integrity-in-the-workplace/articleshow/104631305.cms?utm_source=contentofinterest&utm_medium=text&utm_campaign=cppst.

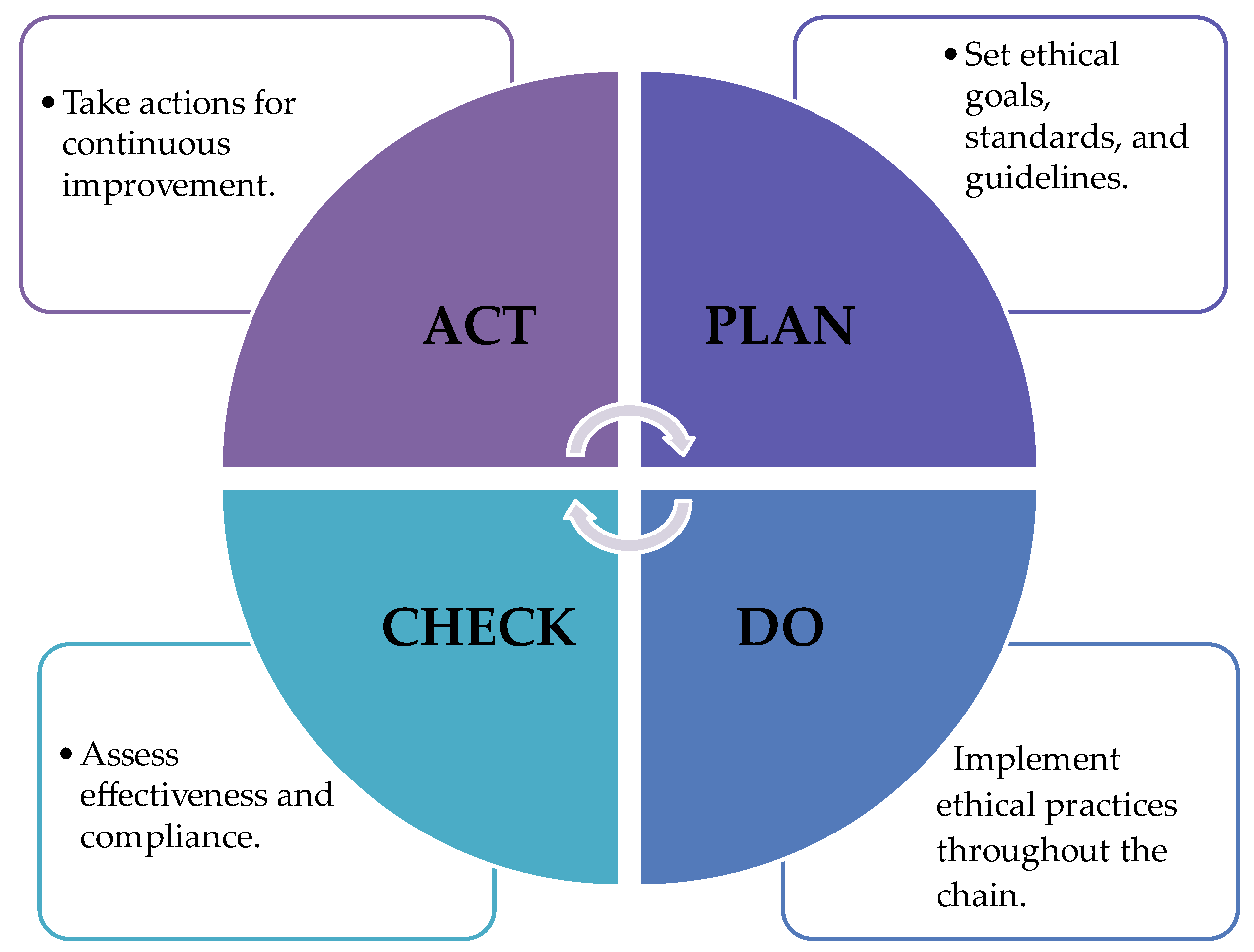

- Gartner, William B., M. James Naughton. The Deming Theory of Management Reviewed Works: A Review of Out of the Crisis by W. Edwards Deming; Deming Guide to Achieving Quality and Competitive Position by Howard W. Gitlow, Shelly J. Gitlow; The Keys to Excellence: The Story of the Deming Philosophy by Nancy Mann; The Deming Route to Quality and Productivity: Roadmaps and Roadblocks by William W. Scherkenbach; The Deming Management Method by Mary Walton. The Academy of Management Review, Vol. 13, No. 1 (Jan., 1988), pp. 138-142 (5 pages). [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.C.; Neonaki, M.; Alexopoulos, A.; Varzakas, T. Case Studies of Small-Medium Food Enterprises around the World: Major Constraints and Benefits from the Implementation of Food Safety Management Systems. Foods 2023, 12, 3218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daraba, A. , Varzakas, T., and Lee, J. 2022. IMPLEMENTATION OF FSMS AND CORRELATION WITH MICROBIOLOGICAL CRITERIA, SYSTEMS THINKING, AND FOOD SAFETY CULTURE. Food Safety Magazine. Column Process Control. https://digitaledition.food-safety.com/december-2022-january-2023/column-process-control/.

- Lee, Jocelyn C. , Aura Daraba, Chrysa Voidarou, Georgios Rozos, Hesham A. El Enshasy and Theodoros Varzakas. Implementation of Food Safety Management Systems along with Other Management Tools (HAZOP, FMEA, Ishikawa, Pareto). The Case Study of Listeria monocytogenes and Correlation with Microbiological Criteria. Foods 2021, 10, 2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 31000:2018 available from : https://knowledge.bsigroup.com/categories/machine-safety-in-manufacturing?creative=689218225134&keyword=bs%20iso%2031000&matchtype=b&network=g&device=c&gad_source=1&gclid=CjwKCAjw5ImwBhBtEiwAFHDZx3mRaECIC-4CWRZJhF3E5t_sPoOCC-xGwkwF4ht34Byy1PDfQccaOxoCPwsQAvD_BwE&gclsrc=aw.ds.

- Leroy, F., F. Abraini, T. Beal, P. Dominguez-Salas, P. Gregorini, P. Manzano, J. Rowntree, S. van Vliet. Animal board invited review: Animal source foods in healthy, sustainable, and ethical diets – An argument against drastic limitation of livestock in the food system. Animal, Volume 16, Issue 3, March 2022, 100457. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, P. Food and Agricultural Biotechnology: Incorporating Ethical Considerations. Prepared for The Canadian Biotechnology Advisory Committee. Project Steering Committee on the Regulation of Genetically Modified Foods. October 2000. Available online from: https://www.iatp.org/sites/default/files/Food_and_Agricultural_Biotechnology_Incorporat.htm.

- Ispas, L.; Mironeasa, C.; Silvestri, A. Risk-Based Approach in the Implementation of Integrated Management Systems: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regulation (ΕU) 2021/382. available from: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2021/382/oj.

- Jacob-John, J., N. K. Veerapa, and C. Eller. 2020. Responsible Food Supply Chain Management: Cases of Irresponsible Behaviour and Food Fraud. N. Mitra, R. Schmidpeter (eds.), Corporate Social Responsibility in Rising Economies, CSR, Sustainability, Ethics & Governance, Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2020. [CrossRef]

- Amaeshi, K. , Osuji, O. & Nnodim, P. Corporate Social Responsibility in Supply Chains of Global Brands: A Boundaryless Responsibility? Clarifications, Exceptions and Implications. J Bus Ethics 81, 223–234 (2008). [CrossRef]

- Macgregor, S. F. J. (2008). Exploring the fit between CSR and innovation.

- Carter, C. , & Rogers, D. A framework of sustainable supply chain management: Moving toward new theory. International Journal of Physical Distribution and Logistics Management 2008, 38, 360–387. [Google Scholar]

- Linnenluecke &, A. Griffiths (Eds.), Chapter 2: The threat of climate change. In M. K. The climate resilient organization: Adaptation and resilience to climate change and weather extremes. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, B. G. Developing sustainable food supply chains. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2008, 363, 849–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wognum, P. M. , Bremmers, H., Trienekens, J. H., Van Der Vorst, J. G. A. J., & Bloemhof, J. M. Systems for sustainability and transparency of food supply chains – Current status and challenges. Advanced Engineering Informatics 2011, 25, 65–76. [Google Scholar]

- Rasul, G. , & Thapa, G. B. Sustainability of ecological and conventional agricultural systems in Bangladesh: An assessment based on environmental, economic and social perspectives. Agricultural Systems 2004, 79, 327–351. [Google Scholar]

- Spink, J. , & Moyer, D. C. Defining the public health threat of food fraud. Journal of Food Science 2011, 76, R157–R163. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yang Y, Huisman W, Hettinga KA, Liu N, Heck J, Schrijver GH, et al. Fraud vulnerability in the Dutch milk supply chain: assessments of farmers, processors and retailers. Food Control. 2019, 95, 308–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everstine K, Spink J, Kennedy S. Economically motivated adulteration EMA of food: common characteristics of EMA incidents. J Food Prot. 2013, 76, 723–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McElwee G, Smith R, Lever J. Illegal activity in the UK halal sheep supply chain: towards greater understanding. Food Policy. 2017, 69, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Meulen, B. Is current EU food safety law geared up for fighting food fraud? Journal für Verbraucherschutz und Lebensmittelsicherheit. 2015, 101, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, CY. Institutional isomorphism and food fraud: a longitudinal study of the mislabeling of rice in Taiwan. J Agric Environ Ethics. 2016, 29, 607–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nöhle, U. Food fraud, food crime oder kalter kaffee? J Consum Protect Food Saf. (2017) 12:197–9. [CrossRef]

- 185. Spink J, Moyer DC. Defining the public health threat of food fraud. J Food Sci. (. [CrossRef]

- 186. Manning L, Soon JM. Developing systems to control food adulteration. Food Policy. (. [CrossRef]

- 187. Bouzembrak Y, Steen B, Neslo R, Linge J, Mojtahed V, Marvin H. Development of food fraud media monitoring system based on text mining. Food Control. (. [CrossRef]

- 188. Zhang W, Xue J. Economically motivated food fraud and adulteration in China: an analysis based on 1,553 media reports. Food Control. (. [CrossRef]

- 189. Schaefer KA, Scheitrum D, Nes K. International sourcing decisions in the wake of a food scandal. Food Policy. (. [CrossRef]

- 190. Rocchi B, Romano D, Sadiddin A, Stefani G. Assessing the economy-wide impact of food fraud: a SAM-based counterfactual approach. Agribusiness. (. [CrossRef]

- Akkoc, R. (2014). Popular with celebrities but could that manuka honey in your cupboard be fake? Telgraph.

- Leak, J. (2013). Food fraud buzz over fake manuka honey. The Australian.

- Singuluri, H. , & Sukumaran, M. (2014). Milk adulteration in Hyderabad, India-a comparative study on the levels of different adulterants present in milk. Journal of Chromatography and Separation Techniques, 5, 1.

- Agriopoulou, S. , Tarapoulouzi, M., and Varzakas, T. 2023. Chemometrics and Authenticity of foods of plant origin. CRC press, Taylor and Francis group. ISBN 9781032199450.

- Bhaskaran, M. (2015). White poison: Why drinking milk could prove fatal for you. Accessed July 19, 2023, from https://indianexpress.com/article/lifestyle/health/white-poison-why-drinkingmilk-could-prove-fatal-for-this-generation/.

- Fassam, L. , Dani, S. & Hills, M. (2015). Supply chain food crime & fraud: a systematic literature review of food criminality.

- Niu L, Chen M, Chen X, Wu L and Tsai F-S (2021) Enterprise Food Fraud in China: Key Factors Identification From Social Co-governance Perspective. Front. Public Health 9:752112. [CrossRef]

- Pearson, HH. The mouth is the gateway to the body. J Dent Que. 1971, 8, 8–9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Parvati, I. Oral Cavity is the Gateway to the Body: Role of Oral Health Professionals: A Narrative Review. Journal of the California Dental Association 2023, 51, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prioreschi, Plinio (1998). A History of Medicine: Roman medicine. Edwin Mellen Press. p. 360. ISBN 978-1-888456-03-5.

- Van der Eijk, Philip, editor. "WINE AND MEDICINE IN ANCIENT GREECE." Greek Medicine from Hippocrates to Galen: Selected Papers, by Jacques Jouanna and Neil Allies, Brill, LEIDEN; BOSTON, 2012, pp. 173–194. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.1163/j.ctt1w76vxr.15. Accessed 18 Dec. 2023.

- Gritzalis, Konstantinos C. (2011). "Gout in the Writings of Eminent Ancient Greek and Byzantine Physicians". Acta Med-hist Adriat. 9 (1): 83–8. PMID 22047483.

- Bujalkova M, Straka S, Jureckova A. Hippocrates' humoral pathology in nowaday's reflections. Bratisl Lek Listy. 2001, 102, 489–492. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Skiadas PK, Lascaratos JG. Dietetics in ancient Greek philosophy: Plato's concepts of healthy diet. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2001 Jul;55(7):532-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkins J et al.1995. Food in antiquity. University of Exeter Press. P. 345. ISBN 0-85989-418-5.

- Ancient Greek Medicine. World History Encyclopedia. Availiable online from : https://www.worldhistory.org/Greek_Medicine/. Accessed March 2024.

- Davison G, Kehaya C, Wyn Jones A. Nutritional and Physical Activity Interventions to Improve Immunity. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2014 Nov 25;10(3):152-169. [CrossRef]

- Macdiarmid, JI. Seasonality and dietary requirements: will eating seasonal food contribute to health and environmental sustainability? Proc Nutr Soc. 2014 Aug;73(3):368-75. [CrossRef]

- Bartos, H. Philosophy and dietetics in the Hippocratic on regimen: a delicate balance of health. Boston: Brill. Edited by Hippocrates (2015).

- Curd, P. (2007). Anaxagoras of Clazomenae. Fragments and Testimonia. Toronto, University of Toronto Press.

- Curd, P. (2015). “Anaxagoras”. In: ZALTA, E. N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Winter 2015 Edition. Available at: https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2015/entries/anaxagoras/.

- Luchte, J. Wandering Souls: The Doctrine of Transmigration in Pythagorean Philosophy. Philosophical Writings. Published with minor variations by Bloomsbury as Pythagoras and the Doctrine of Transmigration: Wandering Souls in 2009Aviailiable online from : https://luchte.wordpress.com/wandering-souls-the-doctrine-of-transmigration-in-pythagorean-philosophy/.

- Dye (1999). Explaining Pythagorean Abstinence from Beans. Available online at Internet Archive: http://web.archive.org/web/20140126011358/http://users.ucom.net/~vegan/beans.htm.

- Nutton, V. (1999). "Healing and the healing act in Classical Greece". European Review. 7 (1): 30. [CrossRef]

- Huffman, C. (2014). “Pythagoras”. In: ZALTA, E. N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Summer 2014 Edition. Available at: https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2014/entries/pythagoras/.

- Dalby, A. (2003). Food in the Ancient World from A to Z. London/New York, Routledge. 30 Rev. Archai (ISSN: 1984-249X), n. 29, Brasília, 2020, e02904.

- Graham, D. W. (2010). The Texts of Early Greek Philosophy. The Complete Fragments and Selected Testimonies of the Major Presocratics. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

- Edelstein, L. (1967). The Relation of Ancient Philosophy to Medicine. In: TEMKIN, O.; TEMKIN, C. L. (eds.). Ancient Medicine. Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press, p. 349-366.

- Garnsey P (1999). Food and Society in Classical Antiquity. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

- Flint-Hamilton, Kimberly B. (1999). "Legumes in Ancient Greece and Rome: Food, Medicine, or Poison?". Hesperia: The Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens. 68 (3): 374. [CrossRef]

- Delatte, A. (1955). Le Cycéon, breuvage habitual des mystères d’Éleusis. Paris, Belles Lettres.

- Dombrowski, D. A. (1984). The Philosophy of Vegetarianism. Amherst, University of Massachusetts Press.

- Kirk, G. S.; Raven, J. E.; Schofield, M. (1984). The Presocratic Philosophers. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

- Matthew 15:10-14. Bible. availiable online from https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Matthew%2015%3A1-10&version=NIV.

- Hawks S (2004).Spiritual Wellness, Holistic Health, and the Practice of Health Education. Journal of Health Education 35(1). [CrossRef]

- Chan C, Ho PS, Chow E. A body-mind-spirit model in health: an Eastern approach. Soc Work Health Care. 2001;34(3-4):261-82. [CrossRef]

- Spanemberg JC, Cardoso JA, Slob EMGB, López-López J. Quality of life related to oral health and its impact in adults. J Stomatol Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2019 Jun;120(3):234-239. [CrossRef]

- Fiorillo, L. Oral Health: The First Step to Well-Being. Medicina (Kaunas). 2019 Oct 7;55(10):676. [CrossRef]

- Kossioni AE, Hajto-Bryk J, Janssens B, Maggi S, Marchini L, McKenna G, Müller F, Petrovic M, Roller-Wirnsberger RE, Schimmel M, van der Putten GJ, Vanobbergen J, Zarzecka J. Practical Guidelines for Physicians in Promoting Oral Health in Frail Older Adults. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2018, 19, 1039–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henni SH, Skudutyte-Rysstad R, Ansteinsson V, Hellesø R, Hovden EAS. Oral health and oral health-related quality of life among older adults receiving home health care services: A scoping review. Gerodontology. 2023, 40, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong FMF, Ng YTY, Leung WK. Oral Health and Its Associated Factors Among Older Institutionalized Residents-A Systematic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019, 16, 4132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeuchi N, Sawada N, Ekuni D, Morita M. Association between oral condition and subjective psychological well-being among older adults attending a university hospital dental clinic: A cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2023, 18, e0295078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson WM, Broder HL. Oral-Health-Related Quality of Life in Children and Adolescents. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2018, 65, 1073–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaffee BW, Rodrigues PH, Kramer PF, Vítolo MR, Feldens CA. Oral health-related quality-of-life scores differ by socioeconomic status and caries experience. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2017, 45, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyling MMG, Frieling ME, Vervoort JPM, Feijen-de Jong EI, Jansen DEMC. Health problems experienced by women during the first year postpartum: A systematic review. Eur J Midwifery. 2023 Dec 18;7:42. Erratum in: Eur J Midwifery. 2024 Feb 05;8: PMID: 38111746; PMCID: PMC10726257. [CrossRef]

- Kazemi S, Savabi G, Khazaei S, Savabi O, Esmaillzadeh A, Keshteli AH, Adibi P. Association between food intake and oral health in elderly: SEPAHAN systematic review no. 8. Dent Res J (Isfahan). 2011, 8 (Suppl 1), S15–S20. [Google Scholar]

- Sensoy, I. A review on the food digestion in the digestive tract and the used in vitro models. Curr Res Food Sci. 2021, 4, 308–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, AML, CE Sørensen, GB Proctor, GH Carpenter. Salivary functions in mastication, taste and textural perception, swallowing and initial digestion. Volume24, Issue8. 18. Pages 1399-1416. 20 November. [CrossRef]

- Lizal F, Elcner J, Jedelsky J, Maly M, Jicha M, Farkas Á, Belka M, Rehak Z, Adam J, Brinek A, Laznovsky J, Zikmund T, Kaiser J. The effect of oral and nasal breathing on the deposition of inhaled particles in upper and tracheobronchial airways. J Aerosol Sci. 2020, 150, 105649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deo PN, Deshmukh R. Oral microbiome: Unveiling the fundamentals. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2019, 23, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatnagar, DM. Oral Health: A Gateway to Overall Health. Contemp Clin Dent. 2021, 12, 211–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO's Global Oral Health Status Report. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240061484, accessed March 2024.

- Barranca-Enríquez A, Romo-González T. Your health is in your mouth: A comprehensive view to promote general wellness. Front Oral Health. 2022, 3, 971223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Abreu MHNG, Cruz AJS, Borges-Oliveira AC, Martins RC, Mattos FF. Perspectives on Social and Environmental Determinants of Oral Health. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021, 18, 13429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazir MA, Izhar F, Akhtar K, Almas K. Dentists' awareness about the link between oral and systemic health. J Family Community Med. 2019, 26, 206–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee YH, Chung SW, Auh QS, et al. Progress in oral microbiome related to oral and systemic diseases: an update. Diagn (Basel). 2021, 11, 1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapila, YL. Oral health’s inextricable connection to systemic health: special populations bring to bear multimodal relationships and factors connecting periodontal disease to systemic diseases and conditions. Periodontol 2000. 2021, 87, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romandini M, Baima G, Antonoglou G, Bueno J, Figuero E, Sanz M. Periodontitis, Edentulism, and Risk of Mortality: A Systematic Review with Meta-analyses. J Dent Res. 2021, 100, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwarz C, Hajdu AI, Dumitrescu R, Sava-Rosianu R, Bolchis V, Anusca D, Hanghicel A, Fratila AD, Oancea R, Jumanca D, Galuscan A, Leretter M. Link between Oral Health, Periodontal Disease, Smoking, and Systemic Diseases in Romanian Patients. Healthcare (Basel). 2023, 11, 2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimopoulou, M.; Antoniadou, M.; Amargianitakis, M.; Gortzi, O.; Androutsos, O.; Varzakas, T. Nutritional Factors Associated with Dental Caries across the Lifespan: A Review. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 13254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang L, Zhi Q, Jian W, Liu Z, Lin H. The Oral Microbiome Impacts the Link between Sugar Consumption and Caries: A Preliminary Study. Nutrients. 2022, 14, 3693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shetty Shodhan A, Shenoy R, Dasson Bajaj P, Rao A, Ks A, Pai M, Br A, Jodalli P. Role of nutritional supplements on oral health in adults -A systematic review. F1000Res. 2023, 12, 492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antoniadou, M.; Varzakas, T. Diet and Oral Health Coaching Methods and Models for the Independent Elderly. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 4021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente-Suárez VJ, Beltrán-Velasco AI, Redondo-Flórez L, Martín-Rodríguez A, Tornero-Aguilera JF. Global Impacts of Western Diet and Its Effects on Metabolism and Health: A Narrative Review. Nutrients. 2023, 15, 2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peponis, M.; Antoniadou, M.; Pappa, E.; Rahiotis, C.; Varzakas, T. Vitamin D and Vitamin D Receptor Polymorphisms Relationship to Risk Level of Dental Caries. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 6014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldens CA, Pinheiro LL, Cury JA, Mendonça F, Groisman M, Costa RAH, Pereira HC, Vieira AR. Added Sugar and Oral Health: A Position Paper of the Brazilian Academy of Dentistry. Front Oral Health. 2022, 3, 869112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicklisch N, Oelze VM, Schierz O, Meller H, Alt KW. A Healthier Smile in the Past? Dental Caries and Diet in Early Neolithic Farming Communities from Central Germany. Nutrients. 2022, 14, 1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Oral health. https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/topics/topic-details/GHO/oral-health#:~:text=The%20World%20Health%20Assembly%20approved,in%20universal%20health%20coverage%20programs. Accessed March 2024.

- WHO. Sugars and dental caries. 2017. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/sugars-and-dental-caries#:~:text=Teeth%20affected%20by%20caries%20are,infection%20or%20adverse%20growth%20patterns. Accessed March 2024.

- Sabharwal, A. , Stellrecht, E. & Scannapieco, F.A. Associations between dental caries and systemic diseases: a scoping review. BMC Oral Health 21, 472 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Karnaki, P.; Katsas, K.; Diamantis, D.V.; Riza, E.; Rosen, M.S.; Antoniadou, M.; Gil-Salmerón, A.; Grabovac, I.; Linou, A. Dental Health, Caries Perception and Sense of Discrimination among Migrants and Refugees in Europe: Results from the Mig-HealthCare Project. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 9294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO 2017. Nityanand Jain, Upasna Dutt, Igor Radenkov, Shivani Jain. WHO's global oral health status report 2022: Actions, discussion and implementation Editorial. First published: 20 January 2023. [CrossRef]

- Giordano-Kelhoffer B, Lorca C, March Llanes J, et al. Oral microbiota, its equilibrium, and implications in the pathophysiology of human diseases: a systematic review. Biomedicines. 2022, 10, 1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuyama Y, Tsakos G, Listl S, Aida J, Watt RG. Impact of Dental Diseases on Quality-Adjusted Life Expectancy in US Adults. J Dent Res. 2019, 98, 510–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell V, Rodrigues AR, Antoniadou M, Peponis M, Varzakas T, Fernandes T. An Update on Drug-Nutrient Interactions and Dental Decay in Older Adults. Nutrients. 2023, 15, 4900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aida J, Takeuchi K, Furuta M, Ito K, Kabasawa Y, Tsakos G. Burden of Oral Diseases and Access to Oral Care in an Ageing Society. Int Dent J. 2022, 72, S5–S11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Putten, G.-J.; de Baat, C. An Overview of Systemic Health Factors Related to Rapid Oral Health Deterioration among Older People. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 4306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng X, Cheng L, You Y, Tang C, Ren B, Li Y, Xu X, Zhou X. Oral microbiota in human systematic diseases. Int J Oral Sci. 2022, 14, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radaic A, Yvonne L. Kapila The oralome and its dysbiosis: New insights into oral microbiome-host interactions. Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal. 2021, 19, 1335–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleinstein SE, Nelson KE, Freire M. Inflammatory networks linking oral microbiome with systemic health and disease. J Dent Res. 2020, 99, 1131–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sedghi L, DiMassa V, Harrington A, Lynch SV, Kapila YL. The oral microbiome: Role of key organisms and complex networks in oral health and disease. Periodontol 2000. 2021, 87, 107–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilian M, Chapple IL, Hannig M, et al. The oral microbiome -an update for oral healthcare professionals. Br Dent J. 2016, 221, 657–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deo PN, Deshmukh R. Oral microbiome: unveiling the fundamentals. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2019, 23, 122–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edlund A, Santiago-Rodriguez TM, Boehm TK, Pride DT. Bacteriophage and their potential roles in the human oral cavity. J Oral Microbiol. 2015, 7, 27423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parras-Moltó M, López-Bueno A. Methods for enrichment and sequencing of oral viral assemblages: saliva, oral mucosa, and dental plaque viromes. Methods Mol Biol. 2018, 1838, 143–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelbary MMH, Hatting M, Bott A, et al. The oral-gut axis: salivary and fecal microbiome dysbiosis in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022, 12, 1010853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitamoto S, Nagao-Kitamoto H, Hein R, Schmidt TM, Kamada N. The bacterial connection between the oral cavity and the gut diseases. J Dent Res. 2020, 99, 1021–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atarashi K, Suda W, Luo C, et al. Ectopic colonization of oral bacteria in the intestine drives TH cell induction and inflammation. Science. 2017, 358, 359–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuraji R, Sekino S, Kapila Y, Numabe Y. Periodontal disease-related nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: an emerging concept of oral-liver axis. Periodontol 2000. 2021, 87, 204–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoneda M, Naka S, Nakano K, et al. Involvement of a periodontal pathogen, porphyromonas gingivalis on the pathogenesis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. BMC Gastroenterol. 2012, 12, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe K, Fujita M, Hayashi M, Okai K, Takahashi A, Ohira H. Gut and oral microbiota in autoimmune liver disease. Fukushima J Med Sci. 2020, 65, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao E, Mattos M, Vieira GHA, et al. Diabetes enhances IL-17 expression and alters the oral microbiome to increase its pathogenicity. Cell Host & Microbe. 2017, 22, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsha TE, Prince Y, Davids S, et al. Oral microbiome signatures in diabetes mellitus and periodontal disease. J Dent Res. 2020, 99, 658–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Negrini TC, Carlos IZ, Duque C, Caiaffa KS, Arthur RA. Interplay among the oral microbiome, oral cavity conditions, the host immune response, diabetes mellitus, and its associated-risk factors-an overview. Frontiers in Oral Health. 2021, 2, 697428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleury V, Zekeridou A, Lazarevic V, et al. Oral dysbiosis and inflammation in parkinson’s disease. J Parkinson’s Dis. 2021, 11, 619–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 286. Fan Z, Li Z, Zhao S, et al. Salivary Aβ1–42 may be a quick-tested biomarker for clinical use in Alzheimer’s disease: a meta-analysis. J Neurol. [CrossRef]

- 287. Liu S, Dashper SG, Zhao R. Association between oral bacteria and alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Alzheimer Dis. [CrossRef]

- Li C, Chen Y, Wen Y, et al. A genetic association study reveals the relationship between the oral microbiome and anxiety and depression symptoms. Front Psychiatry. 2022, 13, 960756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simpson CA, Adler C, du Plessis MR, et al. Oral microbiome composition, but not diversity, is associated with adolescent anxiety and depression symptoms. Physiol Behav. 2020, 226, 113126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wingfield B, Lapsley C, McDowell A, et al. Variations in the oral microbiome are associated with depression in young adults. Sci Rep. 2021, 11, 15009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahrens AP, Sanchez-Padilla DE, Drew JC, Oli MW, Roesch L, Triplett EW. Saliva microbiome, dietary, and genetic markers are associated with suicidal ideation in university students. Sci Rep. 2022, 12, 14306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blekkenhorst LC, Bondonno NP, Liu AH, et al. Nitrate, the oral microbiome, and cardiovascular health: a systematic literature review of human and animal studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 2018, 107, 504–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang J, Xie M, Huang X, et al. The effects of porphyromonas gingivalis on atherosclerosis-related cells. Front Immunol. 2021, 12, 766560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cobb CM, Kelly PJ, Williams KB, Babbar S, Angolkar M, Derman RJ. The oral microbiome and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Int J Women Health. 2017, 9, 551–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balan P, Chong YS, Umashankar S, et al. Keystone species in pregnancy gingivitis: a snapshot of oral microbiome during pregnancy and postpartum period. Front Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye C, You M, Huang P, et al. Clinical study showing a lower abundance of Neisseria in the oral microbiome aligns with low birth weight pregnancy outcomes. Clin Oral Investig. 2022, 26, 2465–2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alwithanani N, Bissada NF, Joshi N, et al. Periodontal treatment improves prostate symptoms and lowers serum PSA in men with high PSA and chronic periodontitis. Dentistry. 2015, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng Z, Do T, Mankia K, et al. Dysbiosis in the oral microbiomes of anti-CCP positive individuals at risk of developing rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021, 80, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corrêa JD, Calderaro DC, Ferreira GA, et al. Subgingival microbiota dysbiosis in systemic lupus erythematosus: association with periodontal status. Microbiome. 2017, 5, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao B, Lou J, Lu H, et al. Oral microbiome characteristics in patients with autoimmune hepatitis. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021, 11, 656674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi Y, Wu HM, Yang Z, et al. New insights into the role of oral microbiota dysbiosis in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2022, 67, 42–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mammen MJ, Sethi S. COPD and the microbiome. Respirology. 2016, 21, 590–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak JL, Yan Y, Zhang Q, Wang L, Ge L. The role of oral microbiome in respiratory health and diseases. Respir Med. 2021, 185, 106475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters BA, Wu J, Pei Z, et al. Oral microbiome composition reflects prospective risk for esophageal cancers. Cancer Res. 2017, 77, 6777–6787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan S, Fang C, Leng WD, et al. Oral microbiota in the oral-genitourinary axis: identifying periodontitis as a potential risk of genitourinary cancers. Mil Med Res. 2021, 8, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaba FI, González RC, Martïnez RG. The role of oral Fusobacterium nucleatum in female breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Dent. 2022, 2022, 1876275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tutuncu EE, Ozgur D, Karamese M. Saliva samples for detection of SARS-CoV-2 in mildly symptomatic and asymptomatic patients. J Med Virol. 2021, 93, 2932–2937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coker MO, Lebeaux RM, Hoen AG, et al. Metagenomic analysis reveals associations between salivary microbiota and body composition in early childhood. Sci Rep. 2022, 12, 13075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawes C, Wong D. Role of saliva and salivary diagnostics in the advancement of oral health. J Dent Res. 2019, 98, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landry V, Coburn P, Kost K, Liu X, Li-Jessen N. Diagnostic accuracy of liquid biomarkers in airway diseases: toward point-of-care applications. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022, 9, 855250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkell, JS. Movement goals and feedback and feedforward control mechanisms in speech production. J Neurolinguistics. 2012, 25, 382–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slavkin HC, Dubois PA, Kleinman DV, Fuccillo R. Science-Informed Health Policies for Oral and Systemic Health. J Healthc Leadersh. 2023, 15, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gkavela, G., A. Kossioni, G. Lyrakos, H. Karkazis, K. Volikas. Oral health related quality of life in older people: Preliminary validation of the Greek version of the Geriatric Oral Health Assessment Index (GOHAI). European Geriatric Medicine. Volume 6, Issue 3, 15, Pages 245-250. 20 June. [CrossRef]

- Paredes-Rodríguez VM, Torrijos-Gómez G, González-Serrano J, López-Pintor-Muñoz RM, López-Bermejo MÁ, Hernández-Vallejo G. Quality of life and oral health in elderly. J Clin Exp Dent. 2016, 8, e590–e596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossioni, A.; Bellou, O. Eating habits in older people in Greece: The role of age, dental status and chewing difficulties. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics. Volume 52, Issue 2, March–11, Pages 197-201. 20 April. [CrossRef]

- Bhatnagar, DM. Oral Health: A Gateway to Overall Health. Contemp Clin Dent. 2021, 12, 211–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruk ME, Gage AD, Arsenault C, Jordan K, Leslie HH, Roder-DeWan S, Adeyi O, Barker P, Daelmans B, Doubova SV, English M, García-Elorrio E, Guanais F, Gureje O, Hirschhorn LR, Jiang L, Kelley E, Lemango ET, Liljestrand J, Malata A, Marchant T, Matsoso MP, Meara JG, Mohanan M, Ndiaye Y, Norheim OF, Reddy KS, Rowe AK, Salomon JA, Thapa G, Twum-Danso NAY, Pate M. High-quality health systems in the Sustainable Development Goals era: time for a revolution. Lancet Glob Health. . Epub 2018 Sep 5. Erratum in: Lancet Glob Health. 2018 Sep 18;: Erratum in: Lancet Glob Health. 2018, 6, e1162. Erratum in Lancet Glob Health. 2021, 9, e1067. 2018, 6, e1196–e1252. [CrossRef]

- Oral Health in America: Advances and Challenges [Internet].. Section 1Effect of Oral Health on the Community, Overall Well-Being, and the Economy. Chapter 1: Status of Knowledge, Practice, and Perspectives. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research(US); 2021 Dec. available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK578297/.

- Listl S, Galloway J, Mossey PA, Marcenes W. Global economic impact of dental diseases. Journal of Dental Research. 2015, 94, 1355–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Righolt AJ, Jevdjevic M, Marcenes W, Listl S. Global-, regional-, and country-level economic impacts of dental diseases in 2015. Journal of Dental Research. 2018, 97, 501–507.

- Australian Research Centre for Population Oral Health, The University of Adelaide, South Australia. Productivity losses from dental problems. Australian Dental Journal. 2012, 57, 393–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guarnizo-Herreño CC, Wehby GL. Children’s dental health, school performance, and psychosocial well-being. The Journal of Pediatrics. 2012, 161, 1153–1159.

- 323. Hayes A, Azarpazhooh A, Dempster L, Ravaghi V, Quiñonez C. Time loss due to dental problems and treatment in the Canadian population: analysis of a nationwide cross-sectional survey. BMC Oral Health.

- Singhal S, Correa R, Quinonez C. The impact of dental treatment on employment outcomes: a systematic review. Health Policy. 2013, 109, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasseh K, Vujicic M, Glick M. The relationship between periodontal interventions and healthcare costs and utilization. Evidence from an integrated dental, medical, and pharmacy commercial claims database. Health Economics. 2017, 26, 519–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernabé E, Masood M, Vujicic M. The impact of out-of-pocket payments for dental care on household finances in low and middle income countries. BMC Public Health. 2017, 17, 109. [Google Scholar]

- Allareddy V, Rampa S, Lee MK, Allareddy V, Nalliah RP. Hospital-based emergency department visits involving dental conditions: profile and predictors of poor outcomes and resource utilization. Journal of the American Dental Association. 2014, 145, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vujicic M, Nasseh K. A decade in dental care utilization among adults and children (2001–2010). Health Services Research. 2014, 49, 460–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh A, Peres MA, Watt RG. The relationship between income and oral health: a critical review. Journal of Dental Research. 2019, 98, 853–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeffcoat MK, Jeffcoat RL, Gladowski PA, Bramson JB, Blum JJ. Impact of periodontal therapy on general health: evidence from insurance data for five systemic conditions. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2014, 47, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avalare Health LLC, based in Washington DC[…],.

- Heng, C. Tooth Decay Is the Most Prevalent Disease. Fed Pract. 2016, 33, 31–33. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- NHI. National institute of dental and craniofacial research. Dental Caries (Tooth Decay). https://www.nidcr.nih.gov/research/data-statistics/dental-caries.

- WHO's Global Oral Health Status Report. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240061484.

- WHO Oral health. 2021 proposal.Availiable online from https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/topics/topic-details/GHO/oral-health.

- Varenne B, Fox CH. The Role of Research in the WHO Oral Health Resolution. JDR Clinical & Translational Research. 2021, 6, 112–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamster, IB. The 2021 WHO Resolution on Oral Health. Int Dent J. 2021, 71, 279–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalpe, S. Anmol Mathur, Priyanka Kharat. How fad diets may jeopardize your oral well-being: The hidden consequences. Human Nutrition & Metabolism. 2023, 33, 200214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Bussel, L. M. , Kuijsten, A., Mars, M., & van ‘t Veer, P. Consumers’ perceptions on food-related sustainability: A systematic review. Journal of Cleaner Production 2022, 341, 130904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheisary Z, Mahmood R, Harri Shivanantham A, et al. The clinical, microbiological, and immunological effects of probiotic supplementation on prevention and treatment of periodontal diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients. 2022, 14, 1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voidarou, C.; Antoniadou, M.; Rozos, G.; Alexopoulos, A.; Giorgi, E.; Tzora, A.; Skoufos, I.; Varzakas, T.; Bezirtzoglou, E. An In Vitro Study of Different Types of Greek Honey as Potential Natural Antimicrobials against Dental Caries and Other Oral Pathogenic Microorganisms. Case Study Simulation of Oral Cavity Conditions. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 6318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath S, Zilm P, Jamieson L, et al. Development and characterization of an oral microbiome transplant among Australians for the treatment of dental caries and periodontal disease: a study protocol. PLoS One. 2021, 16, e0260433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glick, M. , Urquhart, O., Bhosale, A.S. et al. A unified voice to drive global improvements in oral health. BMC Global Public Health 2023, 1, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher J, Berman R, Buse K, Doll B, Glick M, Metzl J, Touger-Decker R. Achieving Oral Health for All through Public Health Approaches, Interprofessional, and Transdisciplinary Education. NAM Perspect. 2023, 2023, 10–31478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jhala CI, Jhala KN. The Hippocratic oath: a comparative analysis of the ancient text's relevance to American and Indian modern medicine. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2012, 55, 279–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, BJ. Ethics and artificial nutrition towards the end of life. Clin Med (Lond). 2010, 10, 607–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardenas, D. Ethical issues and dilemmas in artificial nutrition and hydration. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2021, 41, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thiermann UB, Sheate WR, Vercammen A. Practice Matters: Pro-environmental Motivations and Diet-Related Impact Vary With Meditation Experience. Front Psychol. 2020, 11, 584353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozin P, Haidt J, Fincher K. Psychology. From oral to moral. Science. 2009, 323, 1179–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Region | Legislation | Key Points |

|---|---|---|

| United States | Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA) | Focuses on prevention of foodborne illnesses |

| Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act | Regulates food safety, labeling, and additives | |

| European Union | General Food Law Regulation | Ensures food safety, traceability, and labeling |

| Regulation (EC) No 178/2002 | Establishes general principles and requirements of food law | |

| Regulation (EU) No 1169/2011 | Deals with food information provided to consumers | |

| China | Food Safety Law | Regulates food safety standards and management |

| Food Safety Law (Revised in 2015) | Enhances supervision and management of food safety | |

| India | Food Safety and Standards Act, 2006 | Establishes food safety standards and regulations |

| Food Safety and Standards (FSSAI) Act, 2006 | Sets up the Food Safety and Standards Authority of India | |

| Australia | Food Standards Australia New Zealand | Develops and administers the Australia New Zealand Food Standards Code |

| Food Act 1984 (Victoria) | Regulates food safety, handling, and hygiene |

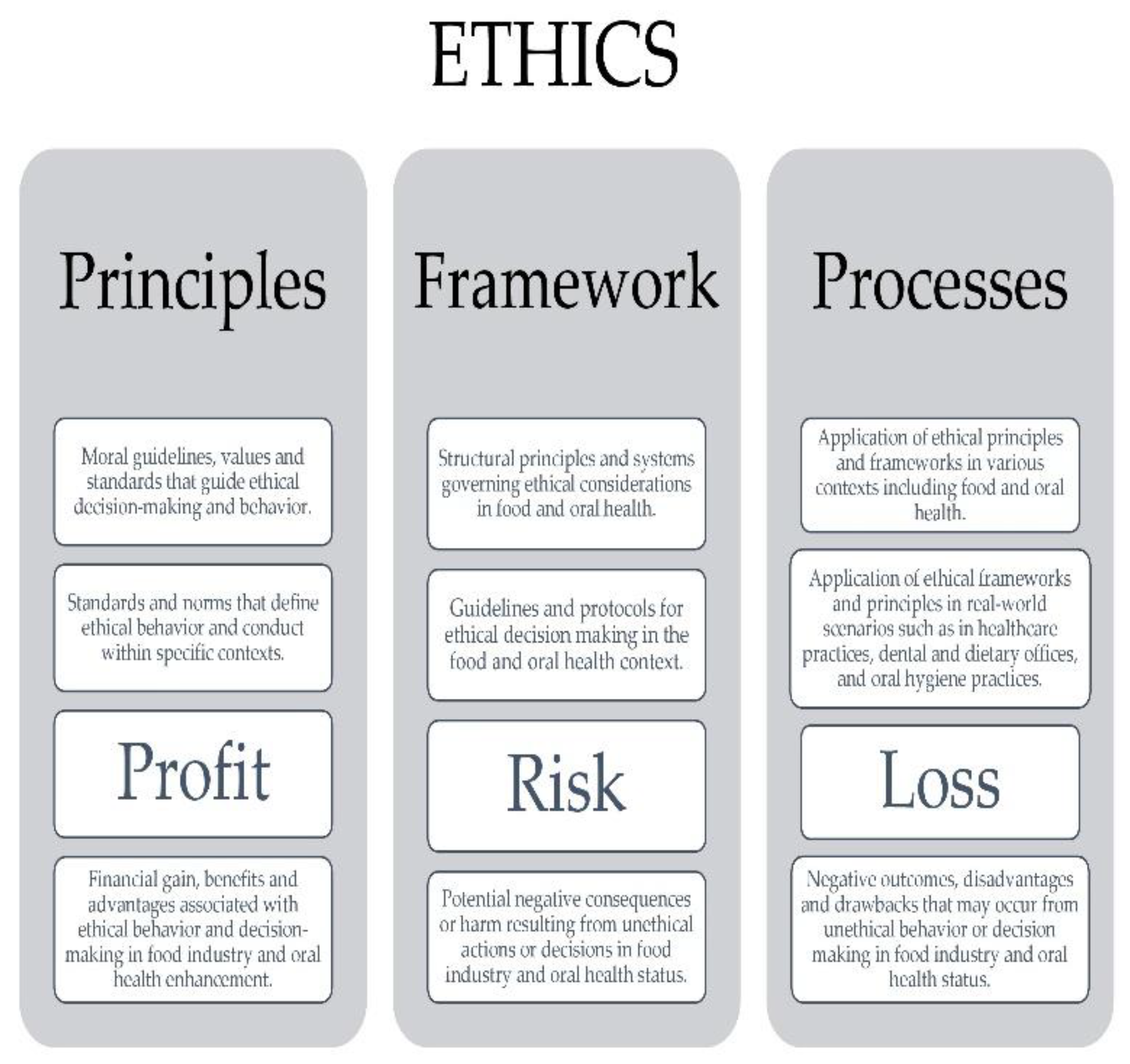

| Ethical principles | Application in the food industry |

|---|---|

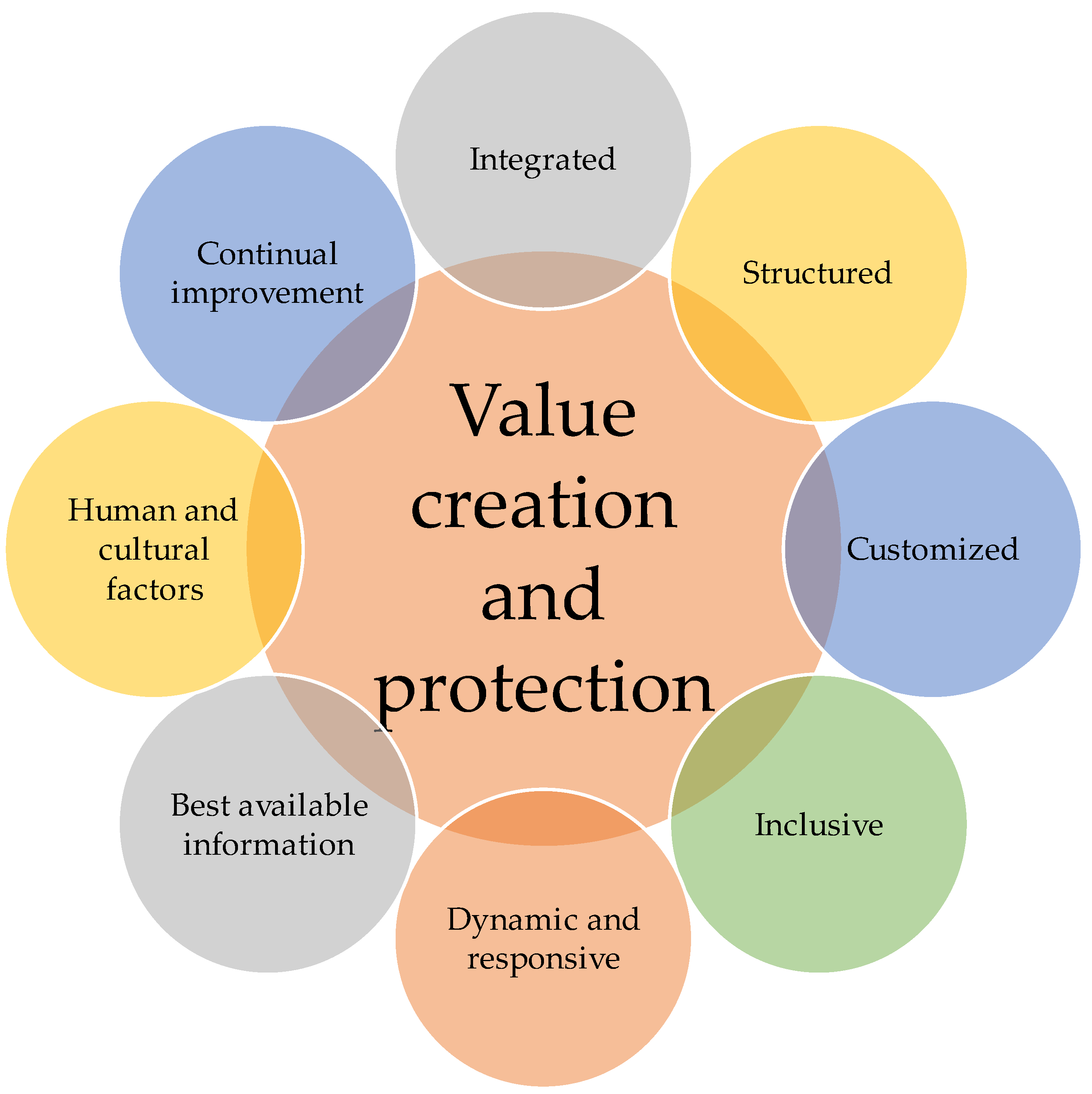

| Value creation and protection | This component emphasizes the importance of creating and protecting value within the food industry. This involves not only generating profit but also ensuring that ethical considerations are prioritized to protect the well-being of consumers, workers, and the environment. |

| Integrated | The food industry must integrate ethical considerations into all aspects of its operations, including production, distribution, marketing, and waste management. This integration ensures that ethical values are embedded throughout the entire supply chain. |

| Structured | Ethical decision-making processes should be structured and systematic, guided by clear principles and guidelines. This ensures consistency and transparency in how ethical dilemmas are addressed within the food industry. |

| Customized | Recognizing that different contexts may require tailored ethical approaches, the food industry should customize its ethical practices to suit specific situations, regions, or cultural norms. This flexibility allows for more effective and culturally sensitive ethical decision-making. |

| Inclusive | Ethical practices in the food industry should be inclusive, considering the perspectives and needs of all stakeholders, including consumers, producers, workers, communities, and regulatory bodies. Inclusivity fosters collaboration and ensures that diverse voices are heard in ethical decision-making processes. |

| Dynamic and responsive | Ethical considerations in the food industry should be dynamic and responsive to changing circumstances, emerging issues, and stakeholder feedback. This adaptability enables the industry to address new challenges and seize opportunities for improvement. |

| Best available information | Ethical decision-making in the food industry should be informed by the best available information, including scientific research, industry standards, consumer preferences, and expert advice. This ensures that decisions are based on evidence and expertise rather than speculation or bias. |

| Human and cultural factors | Ethical practices in the food industry should consider the human and cultural factors that influence food consumption, production, and distribution. This includes considerations of food traditions, dietary preferences, labor rights, and social norms. |

| Continual improvement | The food industry should strive for continual improvement in its ethical practices, seeking to raise standards, address shortcomings, and innovate new solutions. This commitment to ongoing improvement ensures that ethical considerations remain at the forefront of industry efforts. |

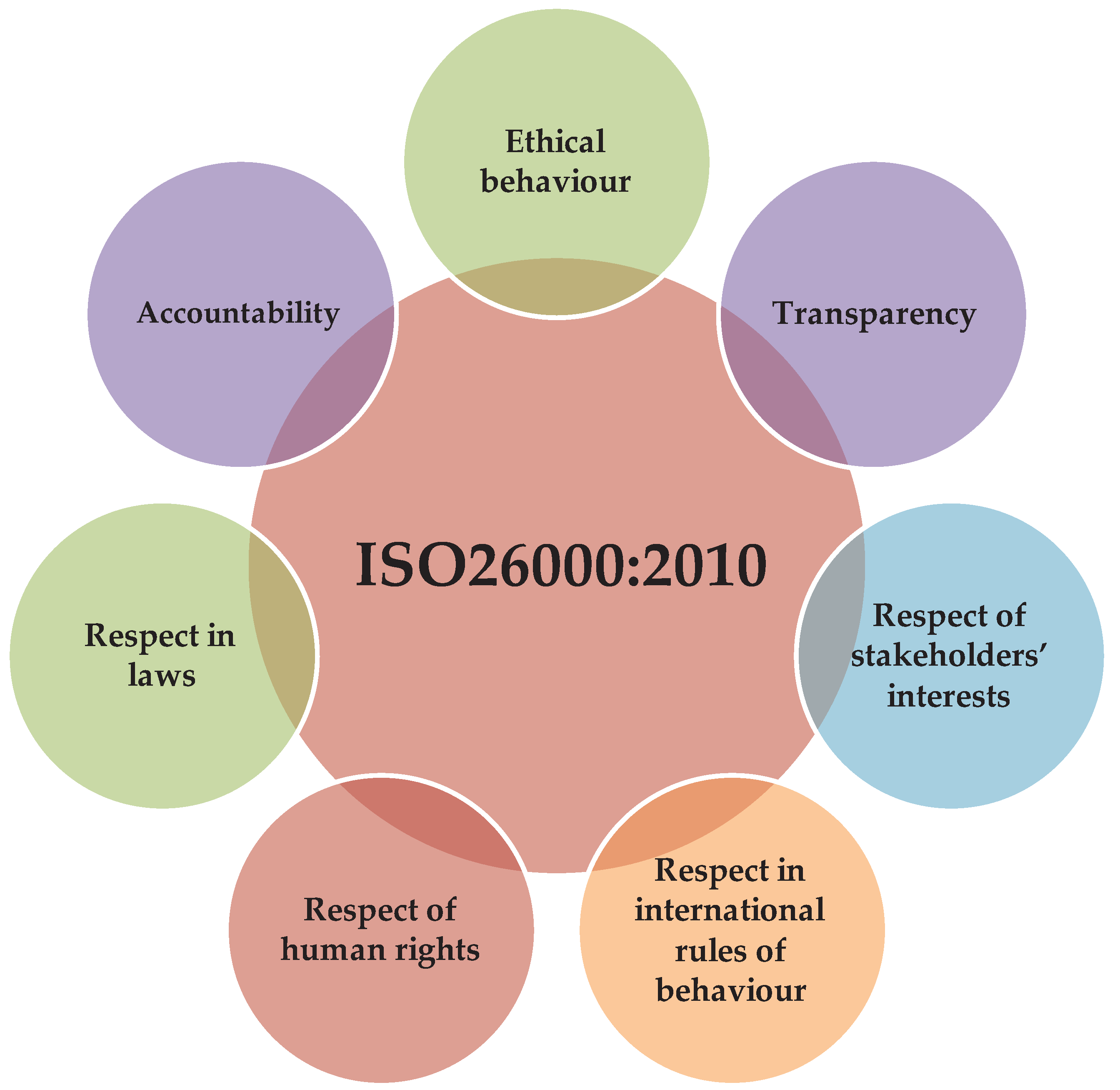

| ISO Standard | Title |

|---|---|

| ISO 26000: 2010 | Guidance on social responsibility |

| ISO 22000:2018 | Food safety management systems |

| ISO 14001:2015 | Environmental management systems |

| ISO 9001: 2015 | Quality management systems |

| ISO 31000:2018 | Risk management |

| ISO 45001:2018 | Occupational health and safety management systems |

| ISO 20400:2017 | Sustainable procurement |

| ISO 50001:2018 | Energy management |

| ISO 22301:2021 | Security and resilience |

| ISO 27001:2018 | Information security management system (ISMS) |

| ISO 37001:2016 | Anti-bribery management systems |

| Food fraud type | Description | Consumer countermeasures |

|---|---|---|

| Mislabeling | Deliberate substitution, addition, tampering, or false/misleading statements for gain | Demand transparency in labeling and certification processes, verify product authenticity, report suspicions |

| Adulteration | Addition of unauthorized substances like formalin, urea, starch, etc. for economic gain | Support stringent quality control measures, seek products with reputable certifications, report suspicions |

| Lack of trust in supply chain | Distrust among supply chain actors, leading to increased vulnerability to fraud | Choose products from transparent and accountable supply chains, support ethical brands, demand traceability |

| Opportunistic behavior | Supply chain partners exploiting situations for personal gain | Enhance fair business practices, endorse initiatives fostering integrity and accountability. |

| Inadequate supply chain governance | Poor oversight and control mechanisms within the supply chain, enabling fraudulent activities | Advocate for regulatory reforms, support initiatives enhancing governance and accountability |

| Complexity of supply chain | Complexity of supply chain operations contributing to increased risk of fraud | Support simplified and transparent supply chain structures, favor local and short supply chains |

| Government regulation | Insufficient regulatory frameworks and enforcement contributing to fraud vulnerabilities | Implement stricter regulations and enforcement, support initiatives promoting regulatory compliance |

| Social governance | Social factors influencing fraud susceptibility within the supply chain | Promote consumer awareness and education, support initiatives fostering social responsibility and transparency |

| Detection techniques | Inadequate fraud detection methods and technologies, allowing fraud to go undetected | Invest in advanced detection technologies, support initiatives improving fraud detection, share information |

| Aspect of oral health | Significance |

|---|---|

| Digestion | Begins in the mouth through chewing (mastication), which breaks down food into smaller particles, facilitating digestion and nutrient absorption. Saliva, produced by salivary glands, contains enzymes that initiate carbohydrate breakdown. |

| Respiratory system | The mouth and nasal cavities are interconnected with the respiratory system, facilitating proper breathing and oxygen intake. |