1. Introduction

Research into sports performance has increasingly highlighted the fundamental role of the psychological dimension in performance [

1,

2]. In this sense, Castro Sanchez et al. [

3] and Ring et al. [

4] indicated that, besides the fact that psychological factors are able of strongly affecting athletes’ behavior, their own performances can be significantly attributed to cognitive and emotional changes they undergo. Thus, the trend in investigation shows the search for the development of optimal mental well-being among athletes, which optimizes and supports their performance.

In relation to Mental Well-Being, one of these factors, perhaps the most prominent and desired optimal mental state, is the Flow State [

5,

6]. The flow state has been associated with an optimal mental state of deep concentration and attention [

7]. Also, it has been correlated with increased productivity and improved performance [

8,

9], with the involvement of positive emotions, happiness, and well-being [

10,

11] and with an adequate direction of attention to the task at hand, without the need for effort [

12]. One of the estimates is that by being in flow, athletes are able, even under pressure, to expand their mental state beyond a state of tension, anxiety and need for self-control [

13].

The search for this optimal mental state has directed research not only to verify the factors that influence and correlate with flow state and its effects on athletes’ behavior, but also intervention strategies that might induce it.

Previous research has suggested that mental training based on mindfulness may be associated as a predictor-facilitator for the athlete to improve dispositional flow state (as a latent projective trait) and achieve flow state in action (flow experience) [

14,

15,

16]. Besides that, these interventions based on mindfulness have been used as mental training that not only brings emotional-psychological well-being to athletes [

17], but also allows, among other possibilities, the reduction of the risk of injuries [

18], the increase of cognitive and emotional flexibility [

19,

20], the decrease of stress and anxiety levels, decrease of negative thoughts and self-criticism [

21,

22], and the possibility of coping with challenging situations [

25,

26].

A widely accepted concept of mindfulness describes the quality of paying attention to the present moment, in an intentional manner, with curiosity, openness and without judgment [

25]. Mindfulness involves the condition of consciously relating to one’s own feelings, emotions, and thoughts, without resistance or experiential avoidance [

26,

27,

28].

Acknowledging that an athlete’s high performance is associated with meditation in movement [

29], some authors have sought to highlight the possible correlations between mindfulness and flow. Hence, Carraça et al. [

30] demonstrates that there is a possible experiential compatibility between them, since both are not only associated with an optimal mental state, but mainly because they work in favor of regulated activity. Differently from the wandering state of mind, since no intentional activity occurs in this condition. Schutte and Malouff [

15] underscored the extent to which high levels of mindfulness are associated with higher levels of flow.

Gardner and Moore [

31] indicated that there is an overlap between the constructs involving flow and mindfulness. For example, knowing that attention, as meta-cognition, plays a regulatory role both on flow state, by bringing order to consciousness, and on mindfulness, by allowing reality to be presented where attention is directed to, it is possible to point out an experiential compatibility between both, mainly because they work in favor of regulated activity [

30,

32]. Jackson and Csikszentmihalyi [

6] point out that one of the ways to enter flow is to focus on the present moment.

Broadly, this study is justified by the comprehension that flow training based on mindfulness not only improves athletes’ mental wellbeing but develop their awareness in the present moment. Besides that, it influences athletes to stablish a relation of acceptance, non-judgement and defusion of their most perturbing malfunctioning thoughts [

2]. Training can also lead them to psychological flourishing, as it induces self-compassion, sports assertiveness, and emotional self-regulation. This would provoke the decrease of reactivity in favor of an intentional action [

33,

34].

This context becomes relevant once there is still a need for investigation that clarifies the advantages of the flow state, mainly regarding the cognitive and emotional processes that mediate the athlete’s performance [

35]. As far as it is known, there are still few studies that can analyze it along with tactical decision-making processes in team sports (e.g., handball), especially when analyzing the effects of the flow state on tactical elements of performance [

16].

Therefore, the main goal of this study was to analyze whether there was an effect of a flow training program based on mindfulness on mental well-being, mindful trait in daily life, mindfulness in sport and decision making in handball athletes. The research analyzed the following hypotheses: H1 – the flow training program based on mindfulness has an impact on dispositional flow state, decision making, mental well-being, mindfulness in sport, and mindful trait in daily life; H2 – the dispositional flow state and mindfulness in sport positively correlate with mental well-being, mindful trait in daily life and decision making; H3 – both dispositional flow state and mindfulness are predictors of athletes’ mental well-being and decision making.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methods

This research is characterized as quantitative, which used the quasi-experimental, non-randomized research method, pre- and post-test and descriptive data analysis.

2.2. Sample

The sample included 105 athletes, 51 female and 54 male. Furthermore, 58 athletes belonged to the adult category and 47 to the youth category. The participants were divided into the experimental group (n=53) and control group (n=52). The composition of the groups by sex, category, average age, years of practice, and weekly hours of training were distributed according to

Table 1.

The athletes who participated in this study were recruited, firstly by invitation and consent by the club / institution where they play. Secondly, a meeting, with all the athletes who were interested, was conducted to clarify aspects regarding the research. Finally, each participant demonstrated voluntary acceptance of participation.

The inclusion criteria for the study were the following: i) the athlete was actively training in a club/institution; ii) he or she was in the youth or adult category; and iii) he or she was available to follow the evaluation protocol (for the control group) or the intervention program based on mindfulness combined with the evaluation protocol (for the experimental group).

The exclusion criteria were: i) the non-signing of the Informed Consent Form by the athlete (in this case, athletes over 18 years old) or by their parents or guardians (in this case, athletes under 18); ii) athletes who were undergoing drug treatment regarding psychological disorders; and iii) athletes who have already participated in a meditation practice protocol or program. Athletes in the control group were offered the possibility of participating in the intervention program based on mindfulness after completing all stages of the research [

6,

36,

37].

2.3. Instruments

1. Sociodemographic Questionnaire (SDQ), prepared for the purposes of this research. This questionnaire contained general identification data (age, gender, level of education). It also posed closed questions that met the inclusion/exclusion criteria (e.g., How long have you been practicing this sport? How many hours of training per week? Are you on any type of drug treatment for psychological disorders? Have you ever participated or are participating in any meditation practice?).

2. Mindfulness Inventory for Sport (MIS-original) [

38]; Brazilian version [

39]. The inventory assesses the quality of athletes’ mindfulness. It consists of 15 items, equally distributed in 3 subscales that can assess the following factors: awareness; non-judgment; and refocusing. Each item is answered using a 6-point Likert scale limited by the extremes 1=not at all and 6=very much.

3. Tactical Intelligence Test in Handball [

40,

41]. The declarative tactical knowledge level protocol verifies the levels of cognitive processes of handball athletes (the level of perception and decision making in game problem-situations) through scenes recorded on video. There are 11 scenes of a handball game, each scene lasting an average of 8 to 10 seconds and focusing on the offensive situations of the attacking player with the ball. It was necessary to make the decision to pass, feint or shoot in each of these scenes. There was a total correctness template, and the athlete received the respective classification score.

4. Dispositional Flow State (DFS) [

42]; Brazilian version [

43]. This instrument assesses an athlete’s perception of several indicators of predisposition to the flow state. This version consisted of 36 items representing the nine dimensions of flow: i) challenge-skill balance (CSB), ii) action-awareness merging (AAM), iii) clear goals (CG), iv) unambiguous feedback (UF), v) total concentration (TC), vi) sense of control (SC), vii) loss of self-consciousness (LSC), viii) transformation of time (TT) and ix) autotelic experience (AE). In addition to total dispositional flow state (DFS

total). Each item was answered on a 5-point Likert scale (1 – Never; 5 – Always).

5. Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale (WEMWBS – Brazilian Version [

44]. It is a scale that allows the measurement of the mental well-being of the general population in a unidimensional way and composed of 14 items measured on a 5-point Likert scale (1=never; 5=always).

6. Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS) [

45]; Brazilian version [

46]. The Scale was used to measure people’s tendency to be fully attentive in daily life, that is, how much internal and external dispositions are fully perceived in the present moment. It is a scale with a single general dimension composed of 15 items, with each item being answered on a 6-point Likert scale (1=almost always; 6=almost never).

2.4. Procedures

The period of recruitment of athletes began in September 2022. For the experimental and control groups (both male and female), the period of recruitment and pre-intervention assessments took place between the 6th and 21st of September and post-intervention assessments took place between November 25th and December 12th, 2022. The nine-week intervention program took place between September 22nd and November 24th, 2022. Both pre-intervention and post-intervention assessments happened face to face, in a room offered by the club/institution. The assessment instruments, as well as the test administrator, was always the same. In both moments (pre and post intervention), the athletes individually filled out the forms related to the instruments in an individual device.

2.5. Study Design

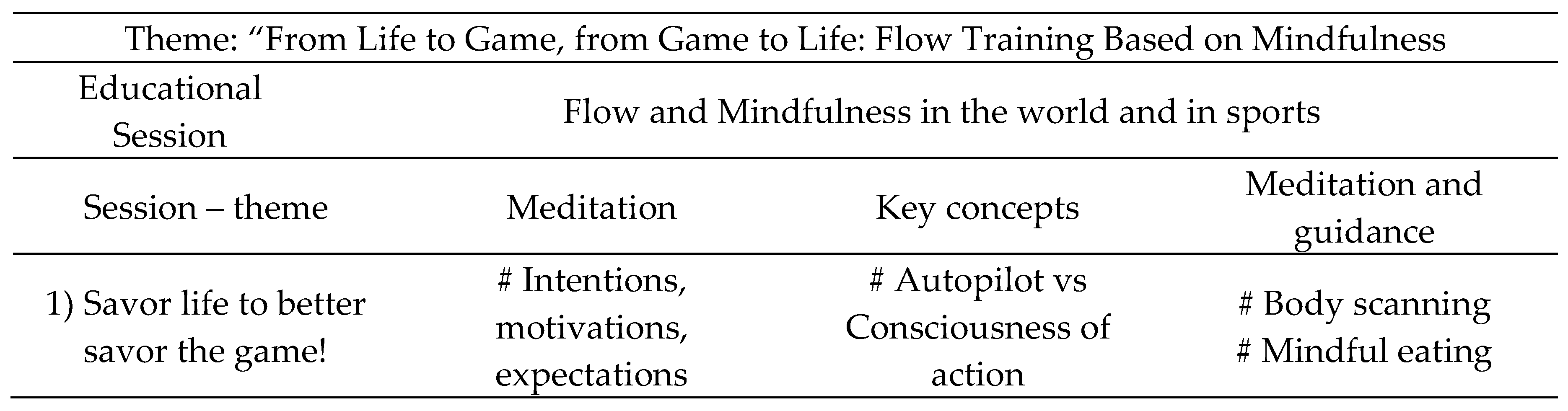

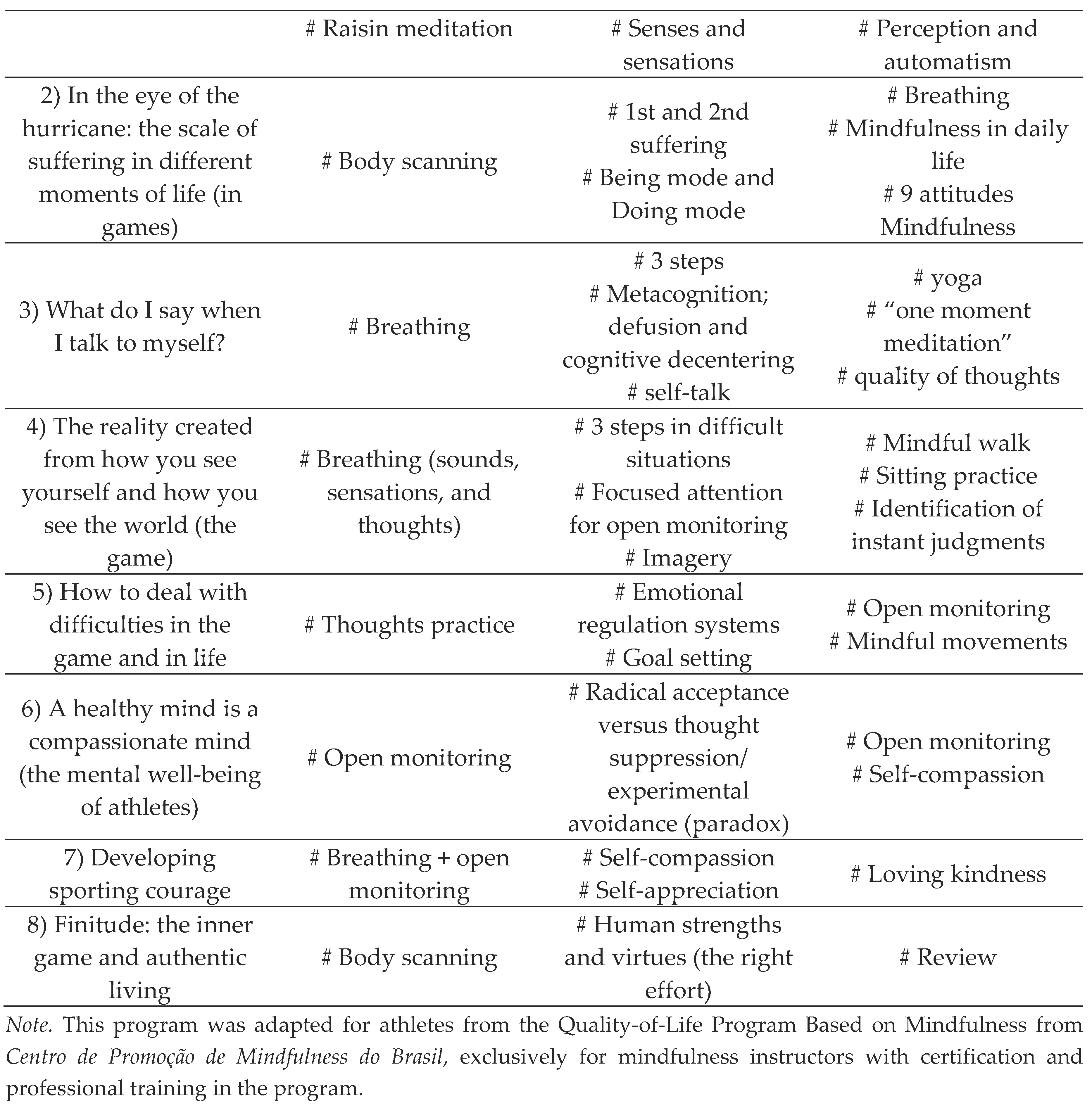

The experimental groups (male adult, female adult, male youth, and female youth) participated individually in the nine-week mindfulness intervention program, with the first week providing clarification on how the program worked and education about flow (adapted) [

47] and about mindfulness [

48,

49]. The following eight weeks consisted of the application of the training program itself. This program followed all MBI-TAC recommendations and guidelines for what a mindfulness intervention program should contain [

50,

51], thus guaranteeing at least 30 minutes per session of exclusive meditation and inquiry practices, as well as the provision of meditation exercises at home.

The sessions also contained psycho-educational exercises with the aim of improving sporting performance, developing psychological skills and their effects, and exercises about compassion, acceptance, and commitment [

30,

37,

52,

53,

54] and their relationships with mental well-being and flow. The sessions occurred face-to-face, once a week for each experimental group individually, in a room offered by the club/institution, and lasted between 90 and 120 minutes. All home meditation sessions were directed according to the mindfulness-based stress reduction program [

25,

48] and the MBSoccer program in the sports context [

37,

52,

55].

Figure 1 presents a more detailed version of the intervention.

2.6. Data Analysis

Statistical analyzes were performed using JAMOVI program (2022 version 2.3). After controlling and correcting non-response to the item (per protocol sample – missing data analysis by analysis), the repeated t-test was applied to verify the assumptions of normality and homogeneity on the pre- and post-intervention measures and the independent t-test to verify significant differences between groups in relation to the variables dispositional flow state and its respective dimensions, mindfulness applied to sport and its respective factors, mindful trait in daily life, decision making and mental well-being before intervention.

ANOVA tests for repeated measures were performed to examine intragroup and intergroup differences (experimental versus control) pre- and post-intervention, with

Post hoc analysis with Scheffe correction when necessary. It was presented, in repeated ANOVA measures, the effect size in partial eta square (n

2p). For interpretation purposes, it was adopted the following reference values: n

2p=.0099 (small effect), n

2p=.0588 (medium effect) and n

2p=.1379 (large effect) [

56]. Pearson’s correlation was also applied to verify the strength of the relationship between the pre- and post-intervention variables and linear regression to examine the differences in the post-test between athletes in the intervention group and the control group, covaried by Mindfulness and flow (baseline) to signal possible variables that predict Decision Making and the Mental Well-Being of athletes.

2.7. Ethical Considerations

The study was submitted and approved under number 5.625.093 by the Ethics Committee of the Instituto Federal do Rio Grande do Norte (IFRN-Brasil). All participants (athletes) were invited to participate anonymously, confidentially, and voluntarily in the study. Everyone received explanations about the objectives of the study and read and signed the Informed Consent Form in accordance with CNS resolution nº466/12. The study does not foresee any risk or harm to the participants.

3. Results

According to the Kolmogorov-Smirnov normality test, the variables decision making, Challenge-skill balance and autotelic experience presented a non-normal distribution (p<0.05, respectively). Using Levene’s homogeneity test, it was found that all research variables (dispositional flow state and its respective dimensions, mindfulness applied to sport and its respective factors, mental well-being, mindful trait in daily life and decision making), are homogeneous (p>0.05). In the independent t-test, the non-parametric Mann-Whitney test was adopted for the variable’s decision making, challenge-skill balance and autotelic experience.

The independent t-test identified that there were significant differences between the groups (control versus experimental) in the pre-test, only in the internal dimensions of dispositional flow state (challenge-skill balance – CSB (U= 962, p<0.016), clear goals - CG (t (101) = -3.314, p< 0.001) and unambiguous feedback - UF (t (101) = -2.233, p< 0.028).

The results of the ANOVA repeated measures obtained statistically significant differences between the groups (control versus experimental), pre-and post-intervention in relation to some of the measures (

Table 2). A significant effect of the intervention emerged in relation to decision making (DM) with a medium to large effect size. The experimental group obtained a statistically significant mean difference in accuracy in decision making when compared to the control group. In the

post hoc analysis, significant differences were found in the group*gender interaction. The female experimental group had a significantly higher mean accuracy rate compared to the female control group (M= -1.122; SD = .260; p

scheffe<.001.).

Regarding dispositional flow state, there were significant differences between the groups in five dimensions, plus the total dispositional flow state. The challenge-skill balance (CSB) dimension showed significant differences between the groups with a large effect. Thus, on average, the experimental group was able to better perceive and balance the challenge required by the task in relation to the skills they had available. The dimension clear goals (CG) also showed significant differences between the groups with a large effect size. In this way, the experimental group managed, on average, to have more clarity about the objectives to be achieved in relation to the control group.

Unambiguous feedback was another dimension that showed significant differences between groups with a large effect size. The experimental group tended to understand more clearly the feedback received about their performance. In post hoc analyses, significant differences in the group*category interaction could also be seen. The youth experimental group tends to have a better understanding, on average, of the feedback received than the adult control (M =-.483; SD = .162; pscheffe<.035) and youth control (M = -.845; SD= .172; pscheffe<.001). The data revealed that the adult experimental group managed to have, on average, better knowledge about the feedback they receive about their performance in relation to the youth control group (M = -.659; SD=.166; pscheffe<.002).

Total concentration on the task (TC) also showed statistically significant differences between groups with a medium effect size. Accordingly, the experimental group, on average, increased its ability to concentrate on the tasks to be performed compared to the control group. sense of control (SC) was another dimension that showed statistically significant differences between the groups with a medium to large effect size. The experimental group, on average, tends to believe that they have better control over the situation and feel more confident compared to the control group.

The experimental group showed, on average, a better total dispositional flow state (DFStotal), with a medium to large effect size, in relation to the control group. In post hoc analyses, there were significant differences in the group*category interaction. The youth experimental group tends to have a better disposition, on average, for the flow state in relation to the youth control group (M= -.476; SD; 0.124; pscheffe<.003).

Regarding the mindfulness inventory for sport (MIS), ANOVA results indicated statistically significant differences between groups with medium effect size on the non-judgment factor (MIS-NJ). The control group, on average, obtained higher application of non-judgment in relation to the experimental group.

The refocusing factor (MIS-RE) also showed statistically significant differences between the groups with a medium effect size. Thus, on average, the experimental group was better able to re-perceive their experiences in the present moment, better than the control group.

Regarding mental well-being (MWB), the ANOVA analysis showed significant differences with a medium effect size. On average, the intervention improves the mental well-being of athletes in the experimental group compared to the control group.

In relation to athletes’ mindful trait in daily life (MAAS), there was also a significant difference with a medium effect size. So, the athletes in the experimental group showed improved mindfulness in different moments of their daily life.

To analyze the strengths of the relationships between the evaluated constructs, Pearson’s correlation was applied between the pre(a) and post-intervention(p) measurements (

Table 3).

The total dispositional flow state (DFSta), in addition to presenting the expected correlations between its own internal dimensions, presented moderate to good positive correlations with the awareness (AWp) factors (r=.426, p<.001, 95%CI [.254-.572]), refocusing (REp) (r=.374, p<.001, 95%CI [.195-.529], mental well-being (MWBp) (r=.477, p< .001, 95%CI [.312-.614]) and mindful trait in daily life (MAASp) (r=.328, p<.001, 95%CI [.144-.491]). Awareness, which is a factor of the mindfulness in sport (MIS-AW), obtained weak to moderate positive correlations with the internal dimensions of the dispositional flow state total concentration on the task (TCp) (r=.236, p=.016, 95% CI [ .045-.411]), autotelic experience (AEp) (r=.307, p=.002, 95%CI [.120-.472] and mental well-being (MWBp) (r=.272 , p=.005, 95% CI [.083-.441].

Refocusing, another factor of the mindfulness in sport (MIS-REa) also showed weak to moderate positive correlations with the clear goals (CGp) dimensions (r=.208, p=.035, 95%CI[.015-.386]), total concentration (TCp) (r= .333, p<.001, 95%CI [.149-494]), sense of control (SCp) (r= .284, p=.004, 95%CI [.096- .453], loss of self-consciousness (LSCp) (r=.213, p=.030, 95%CI [.201-.391]), autotelic experience (AEp) (r=.222, p=.024, 95%CI [.030-.399]) and the total dispositional flow state (DFStotalp) itself (r=.245, p=.012, 95% CI [.054-.419]). Furthermore, MIS-REa presented moderate positive correlation with mental well-being (MWBp) (r= .329, p<.001, 95% CI [.145-490] and weak positive correlation with mindful trait in daily life (MAASp) (r=.267, p= .006, 95% CI [.078-.437]).

The non-judgment factor of mindfulness in sport (MIS-NJa) was the only pre-intervention factor that showed a weak to moderate inverse correlation with post-intervention decision making (DMp) (r=-.269, CI95 % [-.439- -.081].

Simple linear regression analyzes were carried out to verify, from the baseline, the influence of dispositional flow state, mindfulness with their respective factors for sport (awareness, non-judgment and refocusing), on the mental well-being of athletes, mindful trait in daily life and decision-making post-intervention (

Table 4).

The results indicated that the dispositional flow state (DFS) was a predictor for the factors awareness (MIS-AW) and refocusing (MIS-RE) of mindfulness in sport. DFS was also a predictor for mental well-being (MWB) and mindful trait in daily life (MAAS). The results also showed that the factor awareness (MIS-AW) and the factor refocusing (MIS-RE) were also predictors of the athletes’ mental well-being. Furthermore, the factor refocusing (MIS-RE) was a predictor of dispositional flow state (DFS) and mindful trait in daily life (MAAS). Finally, the factor non-judgment (MIS-NJ) was an inverse predictor of decision making (DM).

4. Discussion

The flow training program based on mindfulness proved to be effective in improving the decision-making process of athletes in the experimental group in relation to the control group, pre- and post-intervention. There were also significant results on dispositional flow state, in the factors non-judgment and refocusing of mindfulness in sport, mental well-being and mindful trait in daily life. Besides that, studies have found that there is a relationship between increased flow and mental well-being, achieved through mindfulness training, pre- and post-intervention, as well as mental resistance, coping strategies and psychological flexibility [

20,

57,

58,

59].

The analyzes of the correlations between the measures showed the extent to which flow, and mindfulness are interrelated. And both converge and correlate positively with the athlete’s Mental Well-Being. Schutte and Malouff [

15] indicated not only a strong association between mindfulness and flow but also a connection with a variety of beneficial results for practitioners. Therefore, the improvement of mental well-being can not only be accompanied by an excellent disposition for flow and an adequate level of mindfulness but can also be an excellent indicator of improved athlete performance [

9,

47,

60].

Another important correlation identified was dispositional flow state (DFS) to mindful trait in daily life (MAAS). This positive correlation indicates, initially, that the program can offer the athletes the ability to experience and increase their disposition to flow and mindfulness for other activities that take place outside the context of the courts.

One of the theoretical understandings of the program established this relationship between the game context and personal life. The program assumed that both are not dissociated and that, therefore, the mental state that the athletes get to the court may be related to their behavior outside of it. And this has implications for how they feel, how they direct their decisions and how this reflects on their behaviors. Considering a wider context, the associations between dispositional flow state (DFS), mindfulness in sport (MIS), mindful trait in daily life (MAAS) and mental well-being (MWB) guide us to this analysis [

17,

37].

Mindfulness not only offers the athletes the possibility of making a reperception of their own reality (without judgment of personal value) but also a reorientation on action to break with response patterns [

61]. It is in this sense, when it comes to decision making processes, that a correlation between dispositional flow state and the factors of mindfulness in sports was expected. In this study, this correlation, even though an inverse one, occurred only with the non-judgment factor. However, this result may indicate that both dispositional flow state and the factors awareness and refocusing may occupy a more mediating, indirect, or resulting role rather than a predictor of decision making.

The results even confirm that neither the dispositional flow state, nor the factors refocusing and awareness themselves, were evidenced as predictors of decision making. Despite this, these results point to possible other variables that were not tested and that could explain the emergence of this correlation. Perhaps psychological flexibility itself [

52], attention [

62], or even the role of memory [

63] or self-criticism itself [

21,

22] as factors influencing the performance.

Another important result was the identification of variables that function as predictors. This is the case for dispositional flow state (DFS) and the factor refocusing in sports context as predictor variables for each other; DFS as a predictor for the improvement of mental well-being and athlete’s mindful trait in daily life; and the factors awareness and refocusing as predictors of mental well-being. This comprehension may even indicate that flow and mindfulness may work in favor of regulated activity and for the benefit of the athlete’s better internal functioning [

8,

9,

32]. This may be related to the fact that high levels of mindfulness are associated with high levels of flow, mainly dispositional flow [

15]. However, there is a need for more exploratory studies for better understanding this relationship.

It is significant to point out that the factor non-judgment had an inverse prediction with decision making. This result opens the discussion about a possible ambivalent or diffuse function of the factor non-judgment, from the perspective of the athletes’ understanding. While athletes need to understand the problem-situation of the game (judging and analyzing all relevant signs) to then make a decision, they need to accept (without judgment) their internal states, in order to be able to self-regulate their response so as not to react automatically. In general, people who are able to act non-automatically are the ones who can better self-regulate their responses, present a better disposition for mindfulness and tend not to make judgement [

64].

Therefore, this contradiction about the factor, on the one hand, indicates the need for better clarification and practice time for the full development of the factor non-judgment with the athletes [

39]. On the other hand, perhaps it signals that this factor is expandable and/or that there are other factors that influence the decision-making process. In any case, it is pertinent to point out that athletes constantly place themselves in situations that can trigger internal conflicts, such as making mistakes or not achieving great performance [

22]. However, these inadequate feelings lead the athletes to interpret them as a threat to their self-concept and self-image. These intimidating situations, in addition to causing stress, can lead the athletes to maladaptive coping strategies [

19].

Often, when seeking to protect themselves, the athletes end up attacking themselves, in a process of constant self-criticism. Perhaps the contradiction regarding the factor non-judgment becomes even more evident when it is showed, for example, that self-criticism for some athletes can be considered a primary factor in the pursue for excellence in performance [

33]. The critical point is that, often, these criticisms are accompanied by an excess of constant judgments, usually harsh, condemnatory, and punitive and, as such, trigger dysfunctional internal processes [

65].

These processes, among other disturbances, trigger exaggerated effort, hyper-focus, excessive control, constant tension, anxiety, low self-esteem, and overthinking. Therefore, in addition to leading the athletes to enter a cycle of exhaustion and mental rumination that ends up developing a hyper-identification with the situations that lead them to act in an automatic and reactive manner, they are considered potential factors detrimental to performance [

66]

The studies by Ferguson et al. [

33,

34] and Mosewich et al. [

67] indicated a better psychological flourishing of athletes (e.g., greater autonomy, mastery, growth) when there was the development of self-compassion, sporting assertiveness and emotional self-regulation from the reduction and/or regulation of critical judgment about oneself, until experiential acceptance (non-judgment). In other words, a decrease in reactivity in favor of more intentional action.

Thus, unlike a self-critical mind, which is focused on threats, there would be a more compassionate mind, which offers the possibility of a more conscious and deliberate choice in face of each situation. Therefore, non-judgment could help the athletes to have a better internal balance and a better flow of thoughts, which could lead to a better perception of reality.

If the fact of perceiving and better thinking improves the choices that are made and the decisions that are taken on the court, then it is necessary to understand how to improve the quality of the relationship between (non-)judgment and the role of perception and thoughts in decision making in sports context. This is because players who understand and think better tend to be more decisive when playing. This is why this result of non-judgment as an inverse predictor of athletes’ decision making requires more exploratory studies for a better understanding.

5. Conclusions

The results of this study suggest that the flow training program based on mindfulness has an effect on developing mindful trait in daily life and factors associated with mindfulness in sport, as well as an improvement in the dispositional flow state, as mental well-being and in the decision making of athletes, confirming Hypothesis 1.

One the other hand, both the dispositional flow state and the mindfulness in sport factors awareness and refocusing act in an integrated way between them and were predictors of the athletes’ mental well-being, partially confirming Hypotheses 2 and 3. In any case, the program also seems to function as a link between the athletes’ off-court life and their behavior when playing.

Another point to highlight is the factor non-judgment as a predictor of decision making. This note demonstrates the extension to which the relationship between acceptance, quality and flow of thoughts can predict the quality of decision making made by the athletes in games. However, the discovery of the factor non-judgment as a predictor of decision making indicates the need for more exploratory studies.

In this study it was not confirmed that the dispositional flow state and the factor refocusing are predictors of decision-making process. This indicates that other factors may be involved. In any case, both need more studies to better clarify the role they play in decision making. Since, for example, decision making involves perception and the factor refocusing allows not only a re-perception of the experience, but also a departure from the pattern of habitual (automated) responses. Finally, it may be the case that the relationship between flow and decision making is not a matter of disposition (latent personality trait) or projection, but of direct experience (experiential flow).

As for practical implications, the positive impact of the flow training program based on mindfulness on athletes’ performance and daily life offers important evidence that the program has a potential of being replicated for this population. The results show positive effects on athletes’ mental well-being, decision making, mindfulness in sports and in daily life. These positive results indicate that the training shares important features with holistic approaches, which impact athletes’ behavior on a broad perspective.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.E.M., G.D., J.P.F., and Ru. M.; methodology, L.E.M.; formal analysis, L.E.M.; investigation, L.E.M; resources, L.E.M.; data curation, L.E.M.; writing—original draft preparation, L.E.M.; writing—review and editing, all authors.; visualization, all authors; supervision, G.D., J.P.F., Ru. M.; project administration, L.E.M; funding acquisition, G.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Instituto Federal do Rio Grande do Norte – IFRN-BRASIL (protocol code 5.625.093 approved in 09/05/22).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the athletes who participated in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Limitations

Although the results of this investigation were promising, there are some limitations to be considered in future investigations. The first one is to increase the sample size per category. One suggestion is to apply the program with only one category and gender, but with a larger sample. Another suggestion is to apply the program with athletes from other team sports (e.g., basketball, football) and evaluate the effects.

Even though the results regarding decision making are successful, it is important to highlight that the test has its limitations in the transposition to the real context. In fact, other factors involving decision making were not measured. Mentioned here is the time it takes the athletes to make the decision, reaction time, memory, and anticipation. Finally, a future research suggestion involves associating training based on mindfulness, with the athletes’ creativity, originality and fluency in decision making based on an observational flow scale. Or even relate mental well-being as a predictor of decision making and autotelic experiences.

References

- Lange-Smith, S.; Cabot, J.; Coffee, P. ; Gunnell, k, & David Tod. The efficacy of psychological skills training for enhancing performance in sport: A review of reviews. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Park I & Jeon, J. Psychological skills training for athletes in sports: Web of science bibliometric analysis. Healthcare (Basel), 2023 11(2), 259.

- Castro-Sánchez, M.; Zurita-Ortega, F.; Chacón-Cuberos, R.; López-Gutiérrez, C.J.; Zafra-Santos, E. Emotional Intelligence, Motivational Climate and Levels of Anxiety in Athletes from Different Categories of Sports: Analysis through Structural Equations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ring, C.; Kavussanu, M.; Ali Al-yaaribi, A.S.; Tenenbaum, G.; Stanger, N. Effects of Antisocial Behaviour on Opponent’s Anger, Attention, and Performance. Journal of Sports Science 2019, 37, 871–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Flow and the Foundations of Positive Psychology: The Collected Works of Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi; Springer: Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, S.A.; Csikszentmihalyi, M. Flow in Sports: The Keys to optimal experiences and performances; Human Kinetics: United States of America, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience; Harper and Row: New York, United States of America, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, W.F.; Codonhato, R.; Mizoguchi, M.V.; do Nascimento Junior, J.R.A.; Aizava, P.V.S.; Ribas, M.L.; Caruzzo, A.M.; Vissoci, J.R.N.; Vissoci, J.R.N.; Fiorese, L. Dispositional Flow and Performance in Brazilian Triathletes. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, D.J. , Allen, K. L., Vine, S.J., & Wilson, M. R. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the relationship between flow states and performance. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 2023 16(1), 693-721.

- Alexander, R.; Aragón, O.R.; Bookwala, J.; Cherbuin, N.; Gatt, J.M.; Kahrilas, I.J.; Kästner, N.; Lawrence, A.; Lowe, L.; Morrison, R.G. The Neuroscience of Positive Emotions and Affect: Implications for Cultivating Happiness and Wellbeing. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 2021, 121, 220–249.

- Jackson, S. Joy, Fun, and Flow State in Sport. In Emotions in Sport; Hanin, Y., Eds.; Human Kinetics: United States of America, 2000, pp. 135-156.

- Marty-Dugas, J.; Smilek, D. Deep, effortless concentration: re-examining the flow concept and exploring relations with inattention, absorption, and personality. Psychological Research 2019, 83, 1760–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, S. A. , Thomas, P. R., Marsh, H. W., & Smethurst, C. J. Relationships between flow, self-concept, psychological skills, and performance. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 2001, 13(2), 129–153.

- Aherne, C.; Moran, A.; Lonsdale, C. The Effect of Mindfulness Training on Athletes’ Flow: An Initial Investigation. Sport Psychology 2011, 25, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schutte, N. , & Malouff, J. The connection between mindfulness and flow: A meta-analysis. Personality and Individual Differences, 2023, 200.

- Martiny, L. E.; Theil, L. Z.; Maciel Neto, E.; Dias, G.; Ferreira, J. P.; Mendes, R. Effects of Flow States on Elite Athletes in Team Sports: A Systematic Review. Revista Foco 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazli, Z.; Ghahari, S. The Relationship Between Mindfulness and Psychological Well-being and Coping Strategies with Stress Among Female Basketball Athletes in Tehran. British Journal Of Pharmaceutical Research 2017, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadeh, M.; Ajilchi, B.; Salman, Z.; Kisely, S. Effect of a Mindfulness Programme Training to Prevent the Sport Injury and Improve the Performance of Semi-professional Soccer Players. Australasian Psychiatry 2019, 27, 589–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carraça, B.; Serpa, S.; Rosado, A.; Guerrero, J.P.; Magalhães, C. Mindfull Compassion Training on Elite Soccer: Effects, Roles and Associations on Flow, Psychological Distress and Thought Suppression. Revista Iberoamericana de Psicologia del Ejercicio y el Deporte 2019, 14, 141–149. [Google Scholar]

- Lundgren, T.; Reinebo, G.; Reinebo, G.; Näslund, M.; Parling, T.; Parling, T. Acceptance and Commitment Training to Promote Psychological Flexibility in Ice Hockey Performance: A Controlled Group Feasibility Study. Journal Of Clinical Sport Psychology 2020, 14, 170–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killham, M.; Mosewich, A.; Mack, D.; Gunnell, K.; Ferguson, L. Women athletes’ self-compassion, self-criticism, and perceived sport performance. Sport, Exercise and Performance Psychology, 2018, 7, 297–307.

- Ataabadi, Y.; Cormier, D.; Kowalski, K.; Oates, A.; Ferguson, L.; Lanovaz, J. The Associations Among Self-compassion, Self-esteem, Self-criticism, and Concern over Mistakes in Response to Biomechanical Feedback in Athletes. Front Sports Act Living 2022, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Dehghani, M.; Delbar Saf, A.; Vosoughi, A.; Tebbenouri, G.; Ghazanfari Zarnagh, H. Effectiveness of the Mindfulness-acceptance-commitment-based Approach on Athletic Performance and Sports Competition Anxiety: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Electronic Physician 2018, 10, 6749–6755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidic, Z.; St. Martin, M.; Oxhandler, R. Mindfulness Intervention with a U.S. Women’s NCAA Division I Basketball Team: Impact on Stress, Athletic Coping Skills and Perceptions of Intervention. The Sport Psychologist 2017, 31, 147–159.

- Kabat-Zinn, J. Atenção plena para iniciantes: usando a prática de mindfulness para acalmar a mente e desenvolver o foco no momento presente. Sextante: Rio de Janeiro, Brasil, 2019.

- Shapiro, S.; Siegel, R.; Neff, K. (2018). Paradoxes of Mindfulness. Mindfulness 2018, 9, 1693–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, S.L.; Carlson, L.E.; Astin, J.A.; Freedman, B. (2006). Mechanisms of mindfulness. Journal of Clinical Psychology 2018, 62(3), 373–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Röthlin, P.; Birrer, D.; Horvath, S.; Grosse Holtforth, M. Psychological skills training and a mindfulness-based intervention to enhance functional athletic performance: design of a randomized controlled trial using ambulatory assessment. BMC Psychology 2016, 4, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colzato, L.S.; Colzato, L.S.; Colzato, L.S.; Kibele, A. How Different Types of Meditation Can Enhance Athletic Performance Depending on the Specific Sport Skills. Journal of Cogn Enhanc 2017, 1, 122–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carraça, B.; Magalhães, C.; Martiny, L.; Rosado, A. Mindfulness, flow e flexibilidade compassiva no esporte, In Sawitzki, R., Borges, R., Martiny, L., e Roveda, G. (Eds). Vida, Vivência e Experiência de Professores (as) de Educação Física: Os processos de formação, a Prática Profissional e Estudos sobre o flow. Unijuí: Ijuí, Brasil, 2023.

- Gardner, F.L.; Moore, Z.E. A Mindfulness-acceptance-commitment-based Approach to Athletic Performance Enhancement: Theoretical Considerations. Behavioral Therapy 2004, 35, 707–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- et al. , 2017 Harris, D.J., Vine, S.J., Wilson, M.R. Neurocognitive mechanisms of flow state. Prog Brain Res 2017, (234), 221–243. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, L.; Adam, M.; Gunnell, K.; Kowalski, K.; Mack, D.; Mosewich, A.; Murphy, N. Self-compassion or Self-criticism? Predicting Women Athletes’ Psychological Flourishing in Sport in Canada. Journal of Happiness Studies 2021, 23, 1923–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, L.; Kowalski, K.; Mack, D.; Sabiston, C. Exploring self-compassion and eudaimonic well-being in young women athletes. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 2014, 36, 203-216.

- Roebuck, G.S.; Fitzgerald, P.B.; Urquhart, D.M.; Ng, S.-K.; Cicuttini, F.M.; Fitzgibbon, B.M. The Psychology of Ultra-marathon Runners: A Systematic Review. Psychology of Sport and Exercise 2018, 37, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swann, C. Flow in sport. In Flow Experience: Empirical Research and Applications Harmat, L., Andersen, F., Ullen, F., Wright, J., Sadlo, G., Eds.; Springer: Switzerland, 2016; pp. 51–64. [Google Scholar]

- Carraça, B.; Serpa, S.; Rosado, A.B.; Guerrero, P.; Ozbayer, C.; Kurt, H. Mindfulness and Compassion Strategies on Elite Soccer: Conceptualization of Mindfulness-based Soccer Program (mbsoccerp). Cuadernos de Psicología Del Deporte, 2019, 14, 62–85.

- Thienot, E.; Thienot, E.; Jackson, B.; Dimmock, J.A.; Grove, J.R.; Bernier, M.; Bernier, M.; Fournier, J.F. Development and Preliminary Validation of the Mindfulness Inventory for Sport. Psychol. Sport Exerc 2014, 15, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martiny, L.; Carraça, B.; Magalhães, C.; Dias, G.; Ferreira, P. ; Mendes, R; Validação das propriedades Psicométricas do Inventário da Atenção Plena para Atletas de Handebol do Brasil (MIS-Hbr) Revista Contemporânea, 2024, 4, 481–523.

- Caldas, I. Validação e aplicação de um protocolo do nível de conhecimento tático declarativo no handebol. Tese de doutoramento, Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, Recife, Brasil, 2015.

- Caldas, I.; Viana, M.; Sougey, E. Aplicativo para avaliar o nível de conhecimento tática declarativo no handebol. Revista de Ciencias del Deporte 2017, 13, 77–84. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, S.A.; Eklund, R.C. Assessing Flow in Physical Activity: The Flow State Scale–2 and Dispositional Flow Scale–2. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 2002, 24, 133–150.

- Bittencourt, I.I.; Freires, L.A.; Lu, Y.; Challco, G.C.; Fernandes, S.C.S.; Coelho, J.A.P. de M.; Costa, J.; Pian, Y.; Marinho, A.; Isotani, S. Validation and Psychometric Properties of the Brazilian-portuguese Dispositional Flow Scale 2 (DFS-BR). Plos one, 2021, 16(7).

- Santos, J.; Costa, T.; Guilherme, J.; Silva, W.; Abentroth, L.; Krebs, J.; Sotoriva, P. Adaptation and cross-cultural validation of the Brazilian version of the Warwick-Edinburgh mental well-being scale. Rev Assoc Med Bras 2015, 61, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, K.W.; Ryan, R.M. The Benefits of Being Present: Mindfulness and Its Role in Psychological Well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 2003, 84, 822–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Barros, V.; Kozasa, E.H.; Weiss de Souza, I.C.; Weiss de Souza, I.C.; Ronzani, T.M. Validity Evidence of the Brazilian Version of the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS). Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica, 2015, 28, 87-95.

- Norsworthy, C.; Thelwell, R.C.; Weston, N.J.V.; Jackson, S.A. Flow Training, Flow States, and Performance in Elite Athletes. International Journal of Sport Psychology 2018, 49, 134–152. [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn, J. Viver a catástrofe total: como utilizar a sabedoria do corpo e da mente para enfrentar o estresse, a dor e a doença; Palas Athena: São Paulo, Brasil, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mumford, G.; Jackson, P. The Mindful Athlete: Secrets to Pure Performance; Parallax Press: Berkeley, United States of America, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Crane, R.; Eames, C.; Kuyken, W.; Hastings, R.P.; Williams, J.M.G.; Bartley, T.; Evans, A.; Silverton, S.; Soulsby, J.G.; Surawy, C. Development and Validation of the Mindfulness-based Interventions - Teaching Assessment Criteria (MBI:TAC). Assessment 2013, 20, 681–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crane, R.; Brewer, J.A.; Feldman, C.H.; Kabat-Zinn, J.; Santorelli, S.F.; Williams, J.; Kuyken, W. What Defines Mindfulness-based Programs? the Warp and the Weft. Psychological Medicine 2017, 47, 990–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carraça, B.; Serpa, S.; Rosado, A.; Guerrero, J.P. A Pilot Study of a Mindfulness-based Program (mbsoccerp): The Potential Role of Mindfulness, Self-compassion and Psychological Flexibility on Flow and Elite Performance in Soccer Athletes. Revista Iberoamericana de Psicologia del Ejercicio y el Deporte 2019, 14, 34–40. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, P. Terapia focada na compaixão, 4th ed.; Hogrefe: São Paulo, Brasil, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Neff, C. , & Germer, C. Manual de mindfulness e autocompaixão: um guia para construir forças internas e prosperar na arte de ser seu melhor amigo. Artmed: Porto Alegre, Brasil, 2019.

- Carraça, B.; Serpa, S.; Rosado, A.; Palmi, J. The Mindfulness – Based Soccer Program (MBSoccerP): Effects on Elite Athletes. El Programa Basado en Mindfulness nel Fútbol (MBSoccerP): Efectos en los Atletas de Élite. Cuadernos de Psicología del Deporte, 2018, 18, 62-85.

- Espírito-Santo, H. , & Daniel, F. Calcular e apresentar tamanhos de efeito em trabalhos científicos (3): Guia para reportar os tamanhos de efeito par análises de regressão e ANOVAs. Revista Portuguesa de Investigação Comportamental e Social, 2018, 4, 43-60.

- Chen, J.-H.; Tsai, P.-H.; Tsai, P.-H.; Lin, Y.-C.; Chen, C.-K.; Chen, C.-K.; Chen, C.-Y.; Chen, C.-Y. Mindfulness Training Enhances Flow State and Mental Health Among Baseball Players in Taiwan. Psychology Research and Behavior Management 2018, 12, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, J.; Hao, Q.; Huang, D. Effects of “Mindfulness Acceptance Insight Commitment” Training on Flow State and Mental Health of College Swimmers: A Randomized Controlled Experimental Study. Front Psychol 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vella-Fondacaro, D.; Romano-Smith, S. The Impact of a Psychological Skills Training and Mindfulness-Based Intervention on the Mental Toughness, Competitive Anxiety, and Coping Skills of Futsal Players—A Longitudinal Convergent Mixed-Methods Design. Sports 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, P. The Relationship Between Trait Mindfulness and Well-Being in College Students: The Serial Mediation Role of Flow Experience and Sports Participation. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2023, 16, 2071–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bishop, S.; Lau, M.; Shapiro, S.; Carlson, L.; Anderson, N.; Carmody, J.; Segal, Z.; Abbey, S.; Speca, M.; Veltin, D.; Devins, G. Mindfulness: a proposed operational definition. Clinical Psychology 2019, 9, 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malinowski, P. Neural mechanisms of attentional control in mindfulness meditation. Frontier Neuroscience 2013, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afonso, J.; Garganta, J.; Mesquita, I. A tomada de decisão no desporto: O papel da atenção, da antecipação e da memória. Revista Brasileira de Cineantropometria e Desempenho Humano 2012, 14, 592–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Short, M.; Mazmanian, D.; Oinonem, K.; Mushquash, C. Executive function and self-regulation mediate dispositional mindfulness and well-being. Personality and Indididual Differences 2016, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, S.; Cunha, M.; Rosado, A.; Ferreira, C. How Athletes’ Perception of Coach-related Critical Attitudes Affect Their Mental Health? the Role of Self-criticism. Curr Psychol 2022, 42, 18499–18506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josefsson, T. , Ivarsson, A., Gustafsson, H. et al. Effects of Mindfulness-Acceptance-Commitment (MAC) on sport-specific dispositional mindfulness, emotion regulation, and self-rated athletic performance in a multiple-sport population: An RCT study. Mindfulness, 2019; 10, 1518–1529. [Google Scholar]

- Mosewich, A.; Ferguson, L.; McHugh, T.; Kowalski, K. Enhancing capacity: Integrating self-compassion in sport. Journal of Sport Psychology in Action 2019, 1, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).