Submitted:

02 April 2024

Posted:

04 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

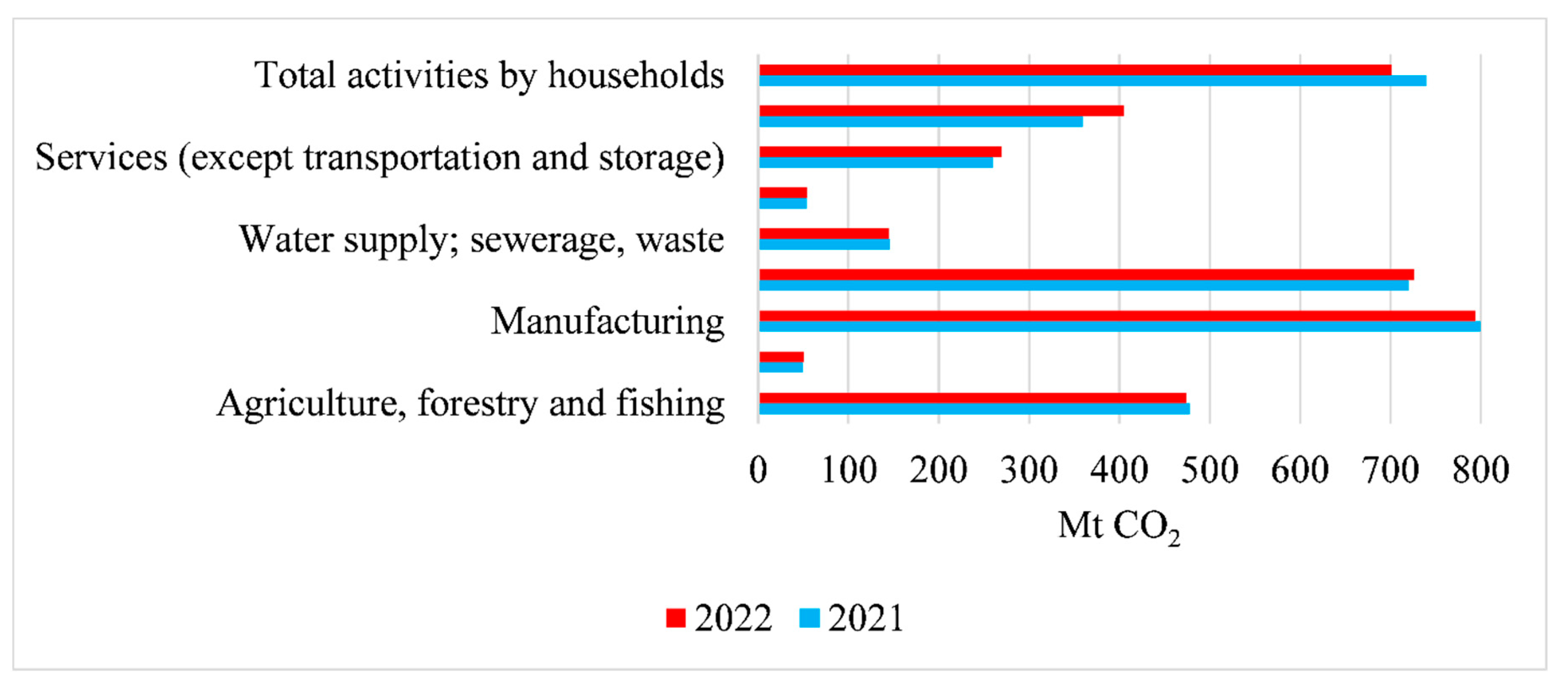

2. War and Pandemic Impact on Climate Strategy and Energy Policy

2.1. Impact in the European Union

- reduce GHG emissions by 40% until 2030 compared with 1990 levels.;

- increase the energy consumption from renewable energy sources up to 32% until 2030;

- improve the energy efficiency of the EU’s final energy consumption by 32.5% until 2030.

- reduce GHG emissions by 55% until 2030 compared with 1990 levels;

- increase the energy consumption from renewable energy sources up to 45% until 2030;

- improve the energy efficiency of the EU’s final energy consumption by 42.5% until 2030.

- to save energy;

- to produce clean energy from renewable sources;

- to diversify the energy supplies.

- the carbon tax;

- the EU ETS (Emission Trading System).

2.2. Impact in Romania as a European Union Member

- reduce the emissions from ETS sectors up to 43.9% compared with 2005 levels and 2% from non-ETS sectors compared with 2005 levels;

- increase to 30.7% the energy from renewable sources from the final energy consumption;

- reduce the final energy consumption by 40.4% compared with the 2007 projection.

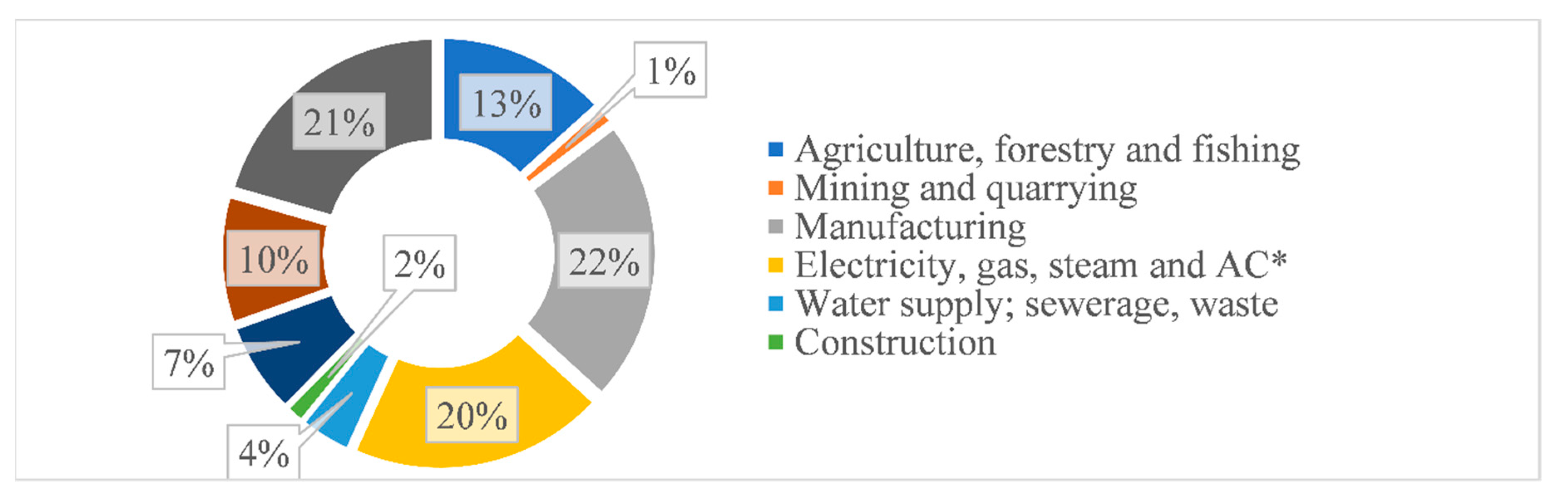

3. Energy in the European Union and Romania

- Energy production (or primary energy consumption), which is energy obtained from another source, in a form that can be used for human needs;

- Energy consumption (or final energy consumption), which is energy in a specific form, used by humans for specific purposes.

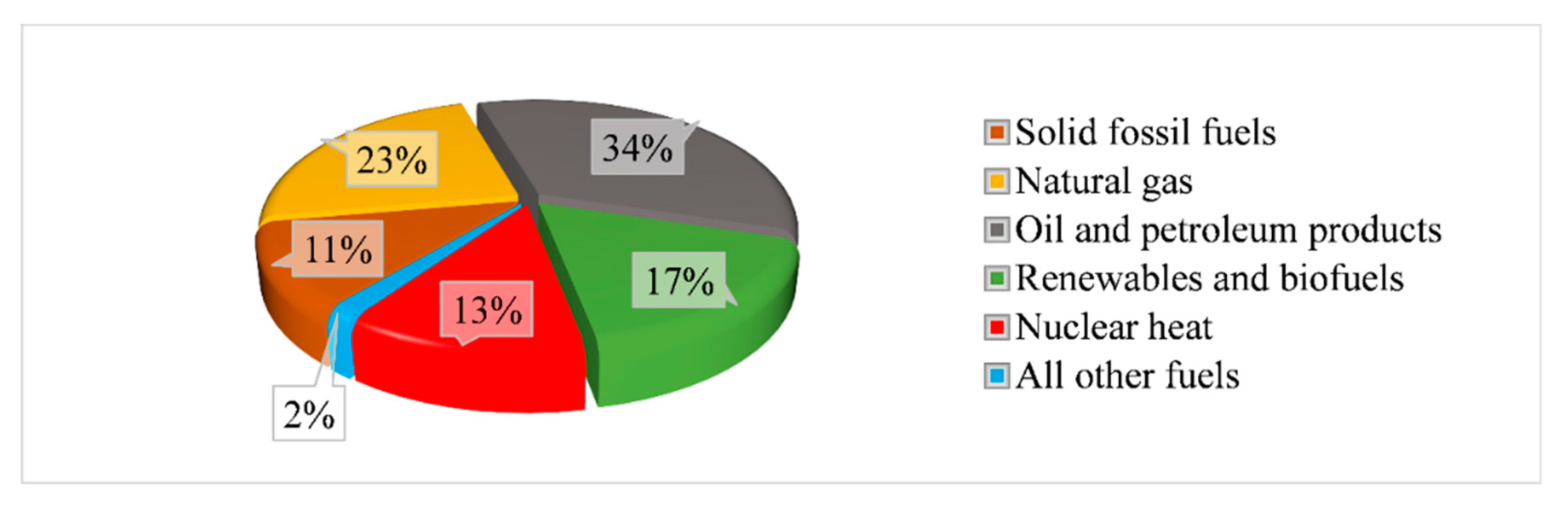

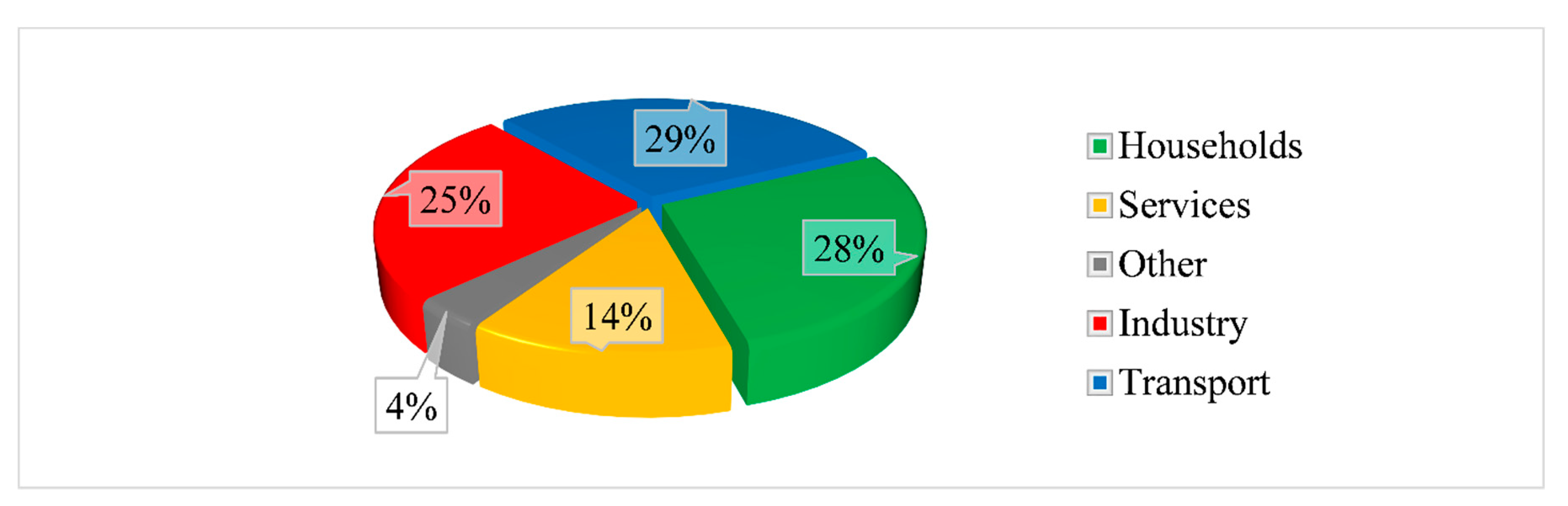

3.1. Energy in the European Union

| 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude oil | 146.18 | 137.63 | 116.98 | 113.34 | 94.8 |

| Natural gas | 102.61 | 93.51 | 90.3 | 96.18 | 39.85 |

| Coal | 64.82 | 54.96 | 44.02 | 51.21 | 25.62 |

| Liquified natural gas | 1.19 | 3.87 | 4.75 | 7.02 | 8.57 |

| Petroleum oil from natural gas | 0.45 | 0.64 | 0.72 | 1.01 | 1.12 |

| Coke | 0.56 | 0.67 | 0.55 | 0.82 | 0.37 |

| Peat | 0.11 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.21 | 0.12 |

| Lignite | 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0 |

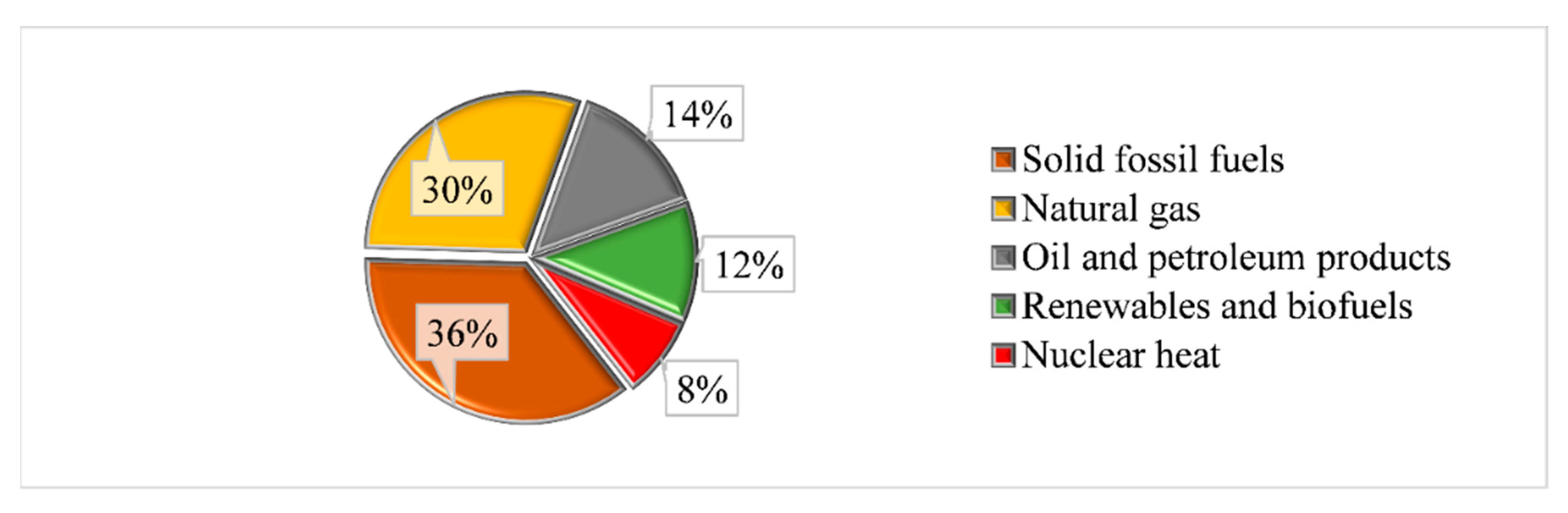

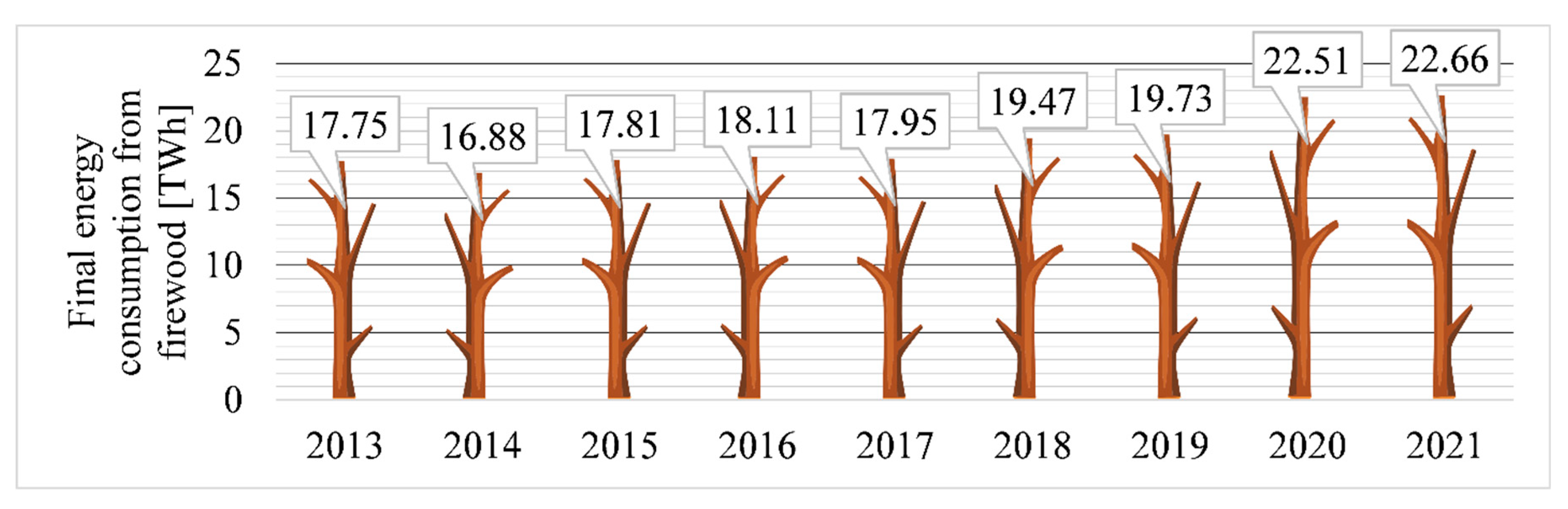

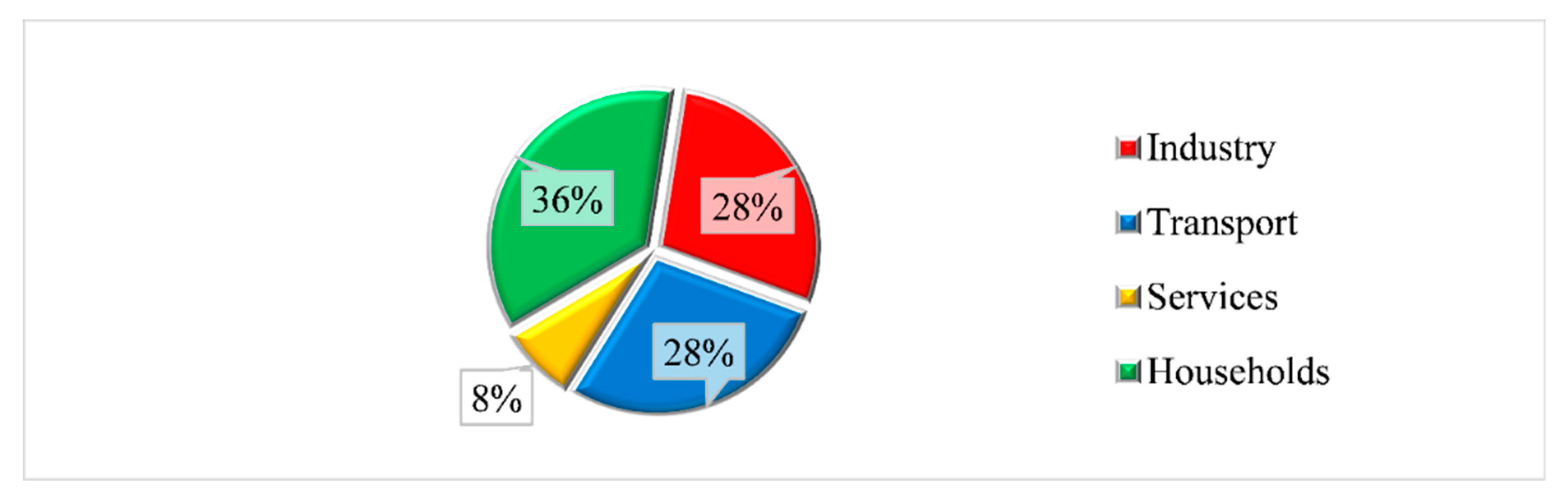

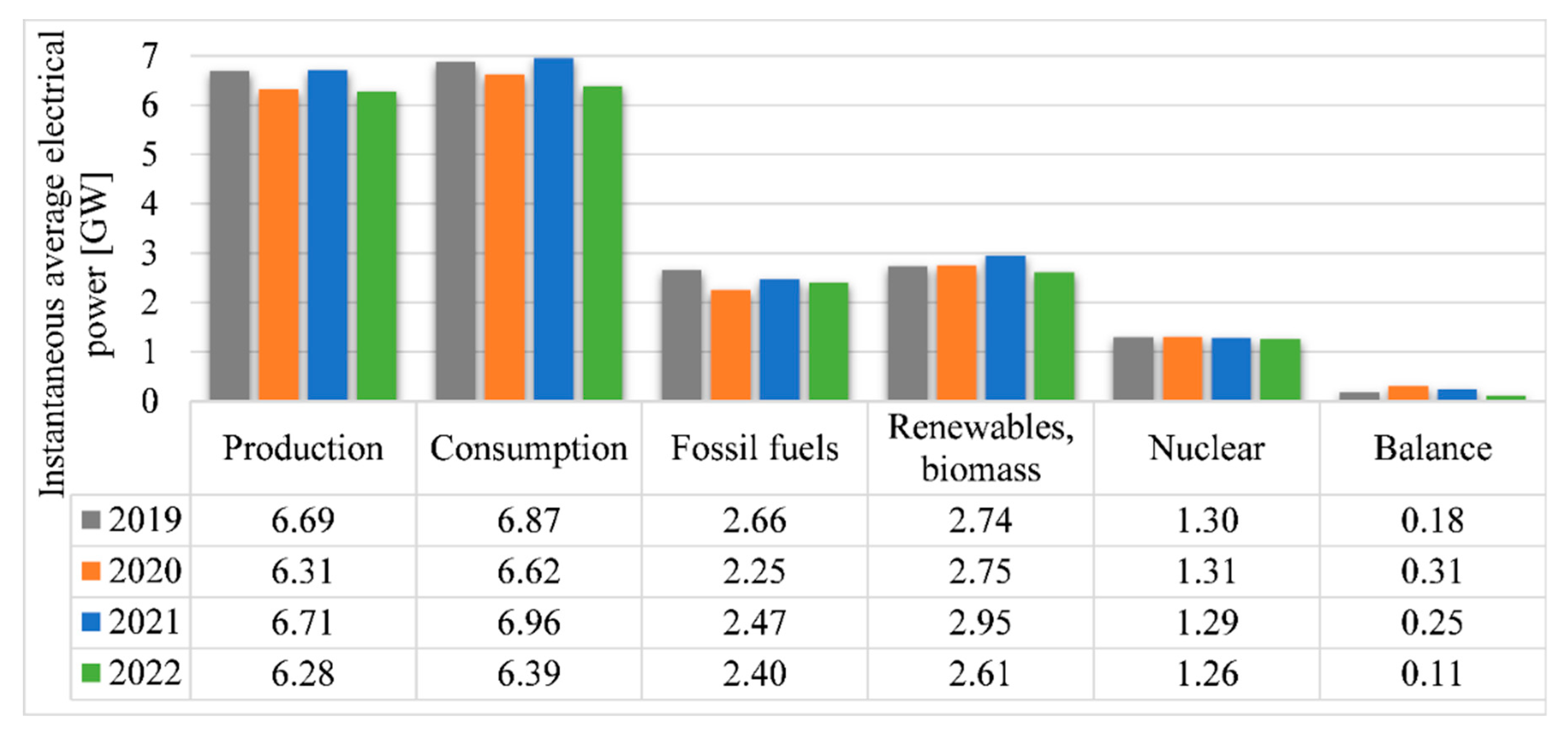

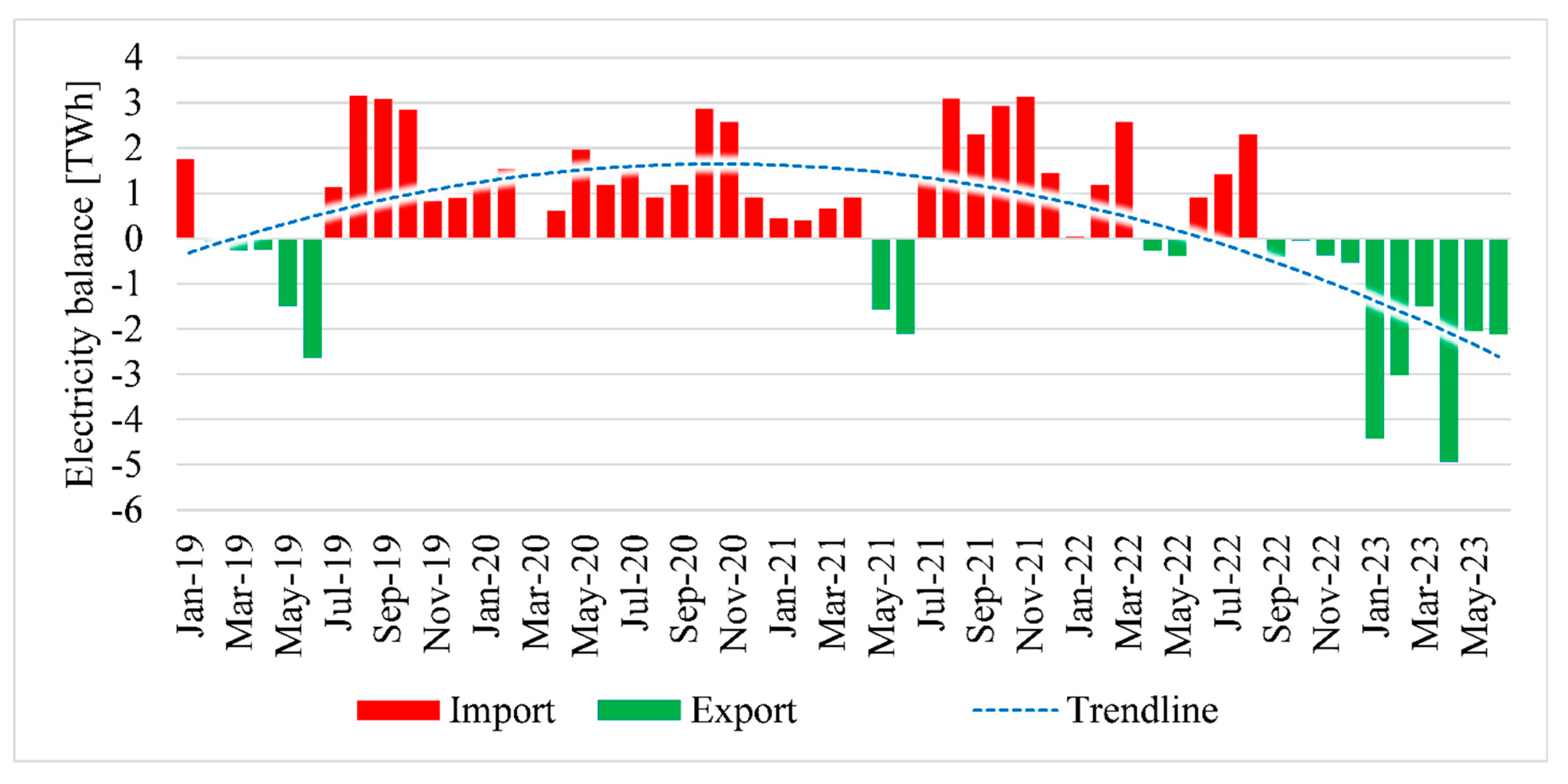

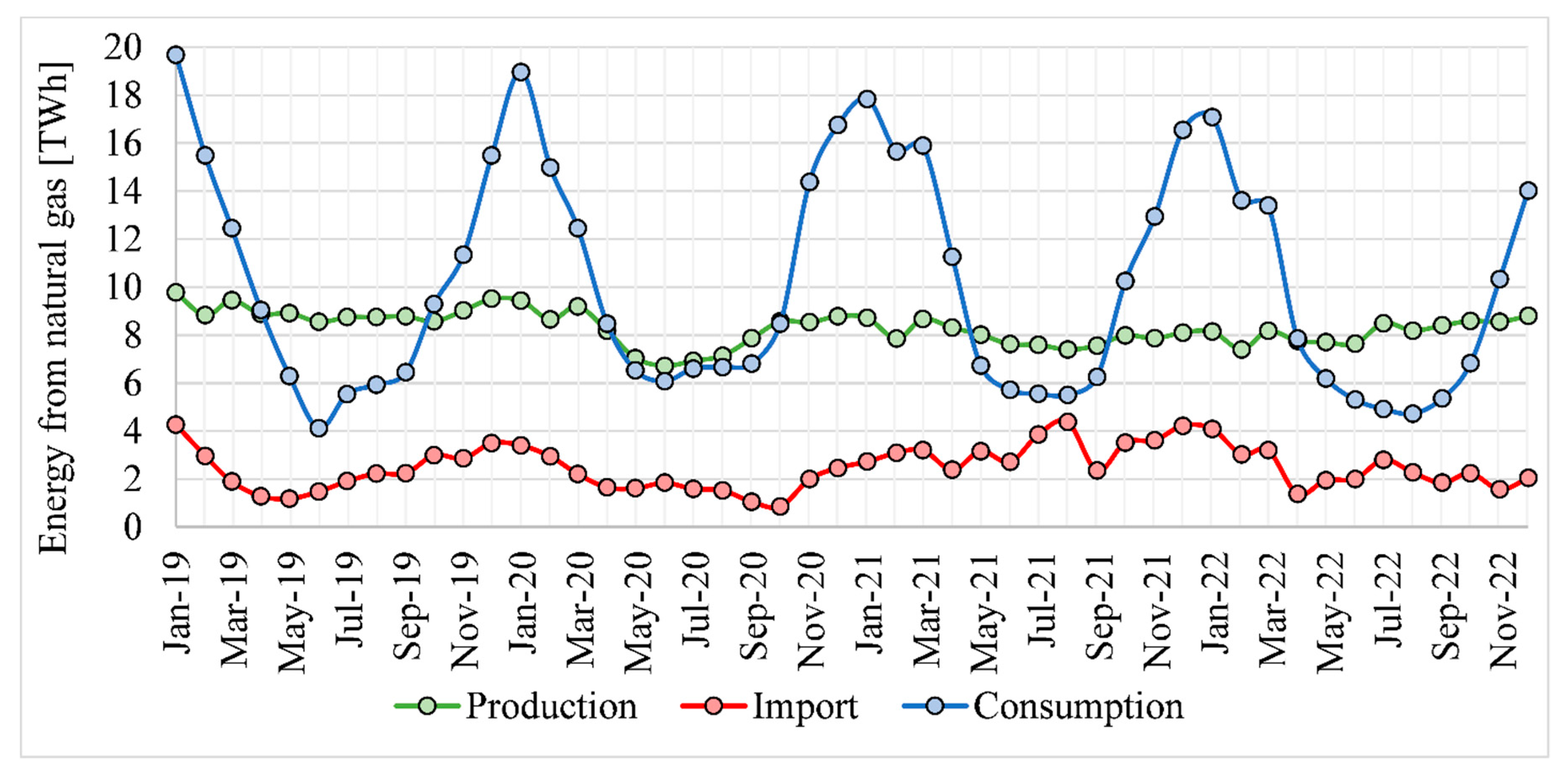

3.2. Energy in Romania

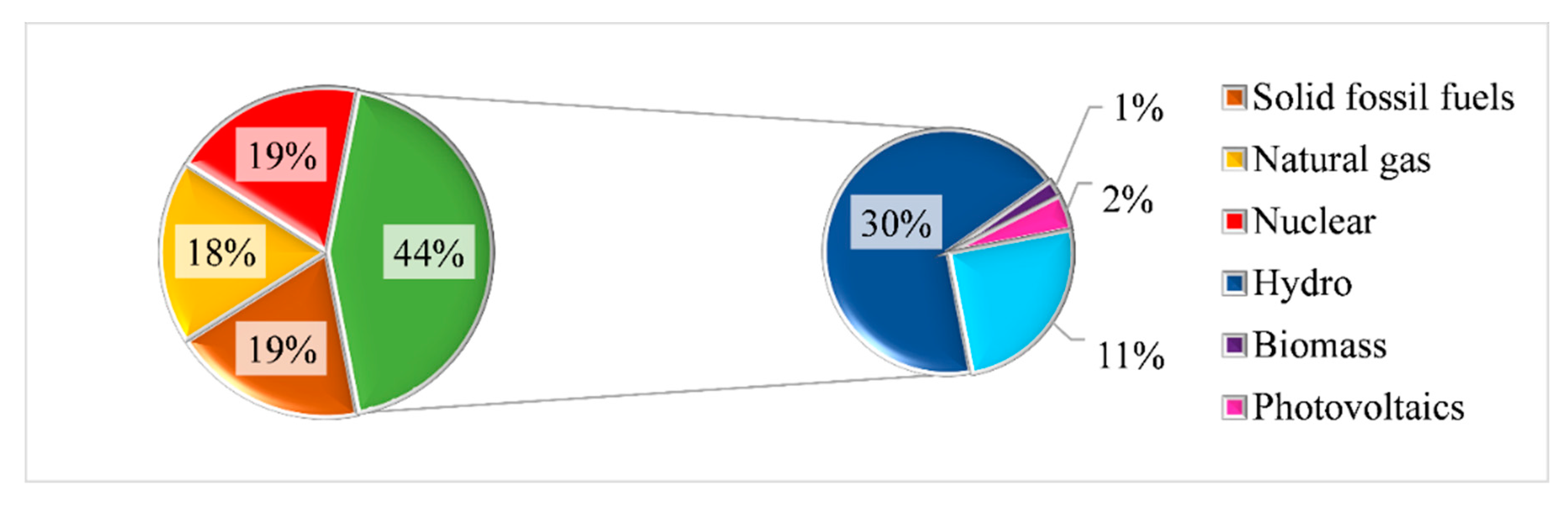

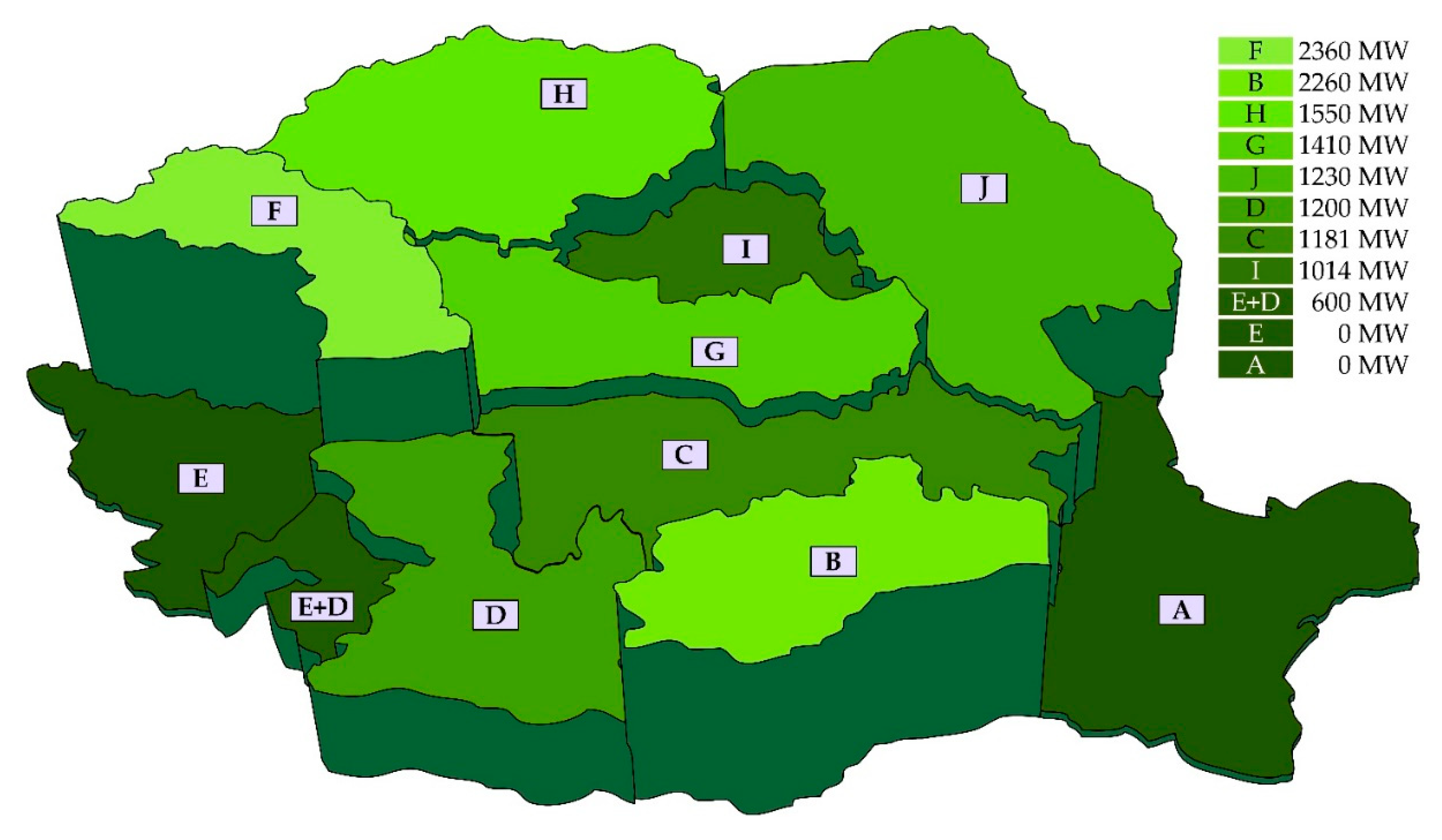

3.3. Romania’s Potential for Greener Electricity Production

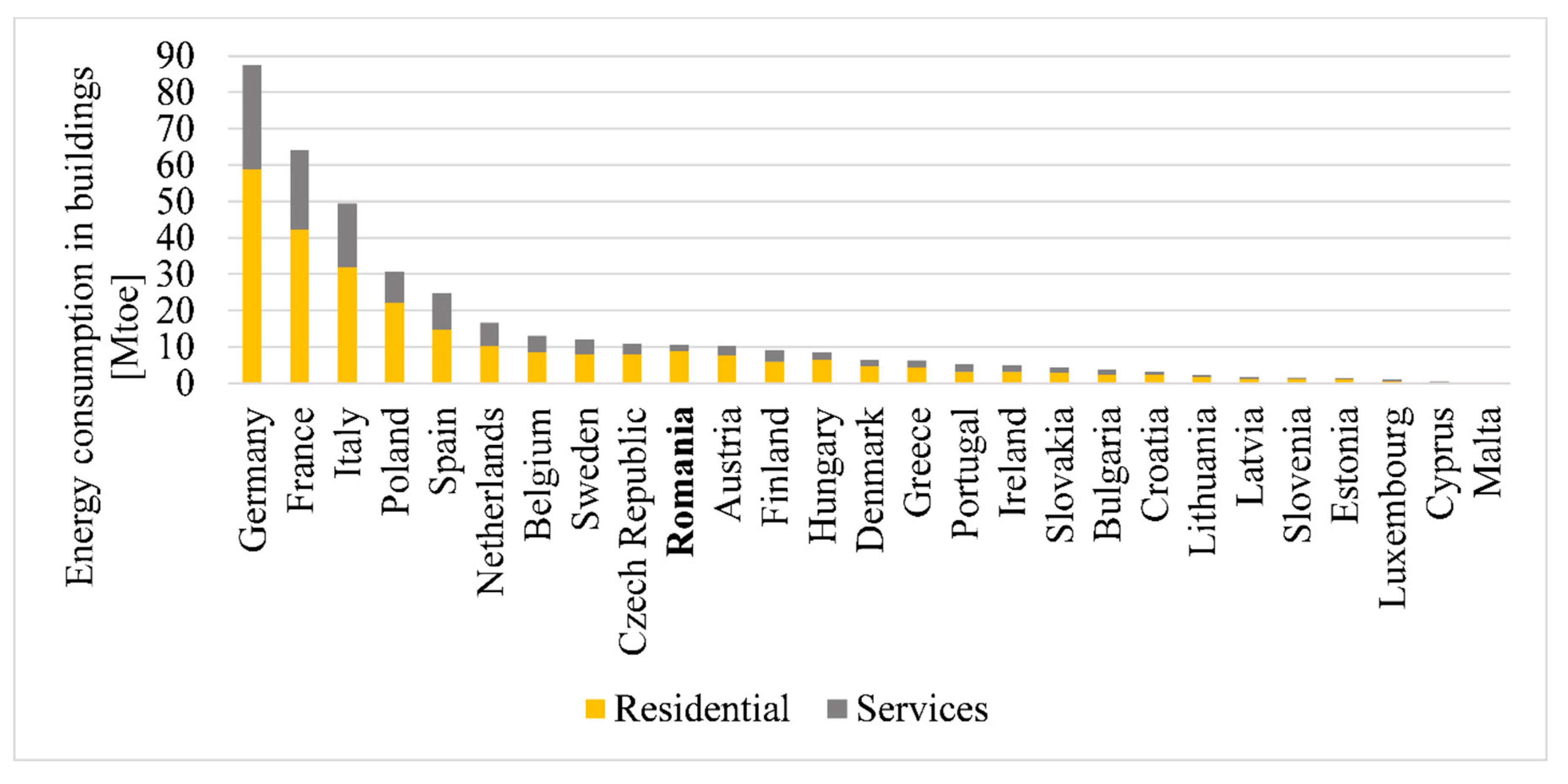

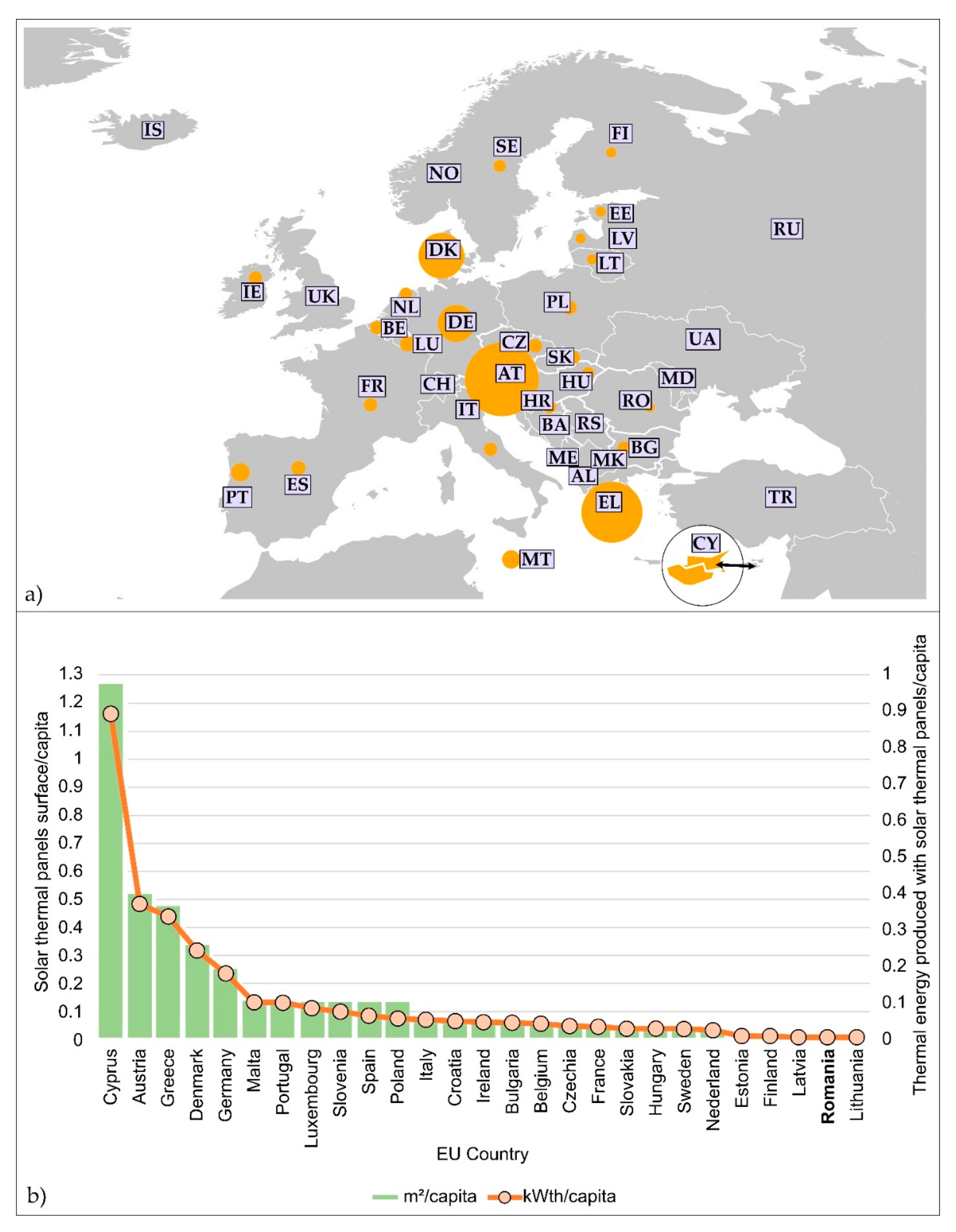

4. Buildings Sector

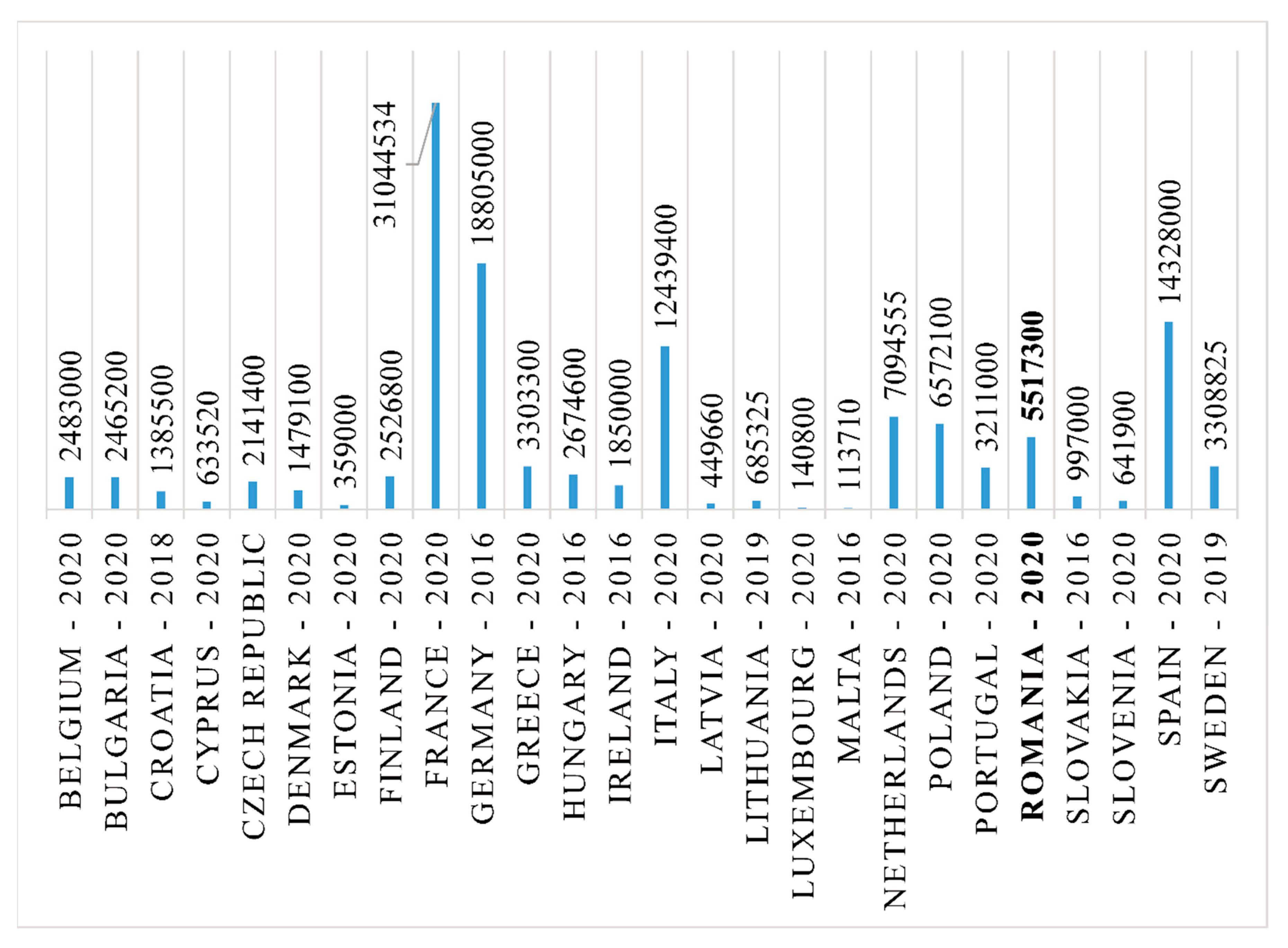

4.1. Buildings in the European Union

- all new buildings must be zero emission buildings from 2028;

- all new public buildings must be zero emission buildings from 2026;

- all new buildings need to have solar technology from 2028;

- all residential buildings that need renovation need to have solar technology from 2032;

- residential buildings need to reach class E by 2030 and class D by 2033;

- non-residential and public buildings need to achieve class E by 2027 and class D by 2030;

- fossil fuel in new heating systems will be totally eliminated by 2035.

4.2. Buildings in Romania

5. Discussion

6. Conclusion and Policy Implications

- reduce the GHG emissions by 55% until 2030, 95% until 2040 and 100% by 2050;

- reduce the emissions from ETS sectors up to 43.9% and 2% from non ETS sectors;

- increase the primary energy consumption from renewables up to 45% until 2030;

- improve the energy efficiency for EU’s final energy consumption by 42.5% until 2030;

- increase to 30.7% the energy from renewable sources from the final energy consumption;

- reduce the final energy consumption by 40.4% compared with the 2007 projection;

- all new buildings must be zero emissions buildings from 2026 and 2028 onwards;

- all new buildings need to have solar technology from 2028;

- all residential buildings that need renovation need to have solar technology from 2032;

- residential buildings need to reach class E by 2030 and class D by 2033;

- non-residential and public buildings need to achieve class E by 2027 and class D by 2030;

- fossil fuel in new heating systems will be totally eliminated by 2035;

- revised the Romanian Energy Strategy in 2022 with the regional power provider in mind;

- started the Recovery and Resilience plan, funded by the EU, to help with post-pandemic and war effects on energy.

- EU saved 20% of energy consumption in 2022;

- Russian gas imports in EU dropped to 8% in September 2022 compared to August 2021;

- EU photovoltaics capacity increased to 47% in 2022 compared to 2021;

- electricity generated from renewables in EU increased to 22%, overtaking natural gas for the first time by 2.5%;

- it is estimated that fossil fuel usage in EU will register a 20% drop in 2023 compared to 2022;

- energy imports from Russia decreased with 90% in March 2023 compared with the monthly figures from 2019 to 2022 in EU;

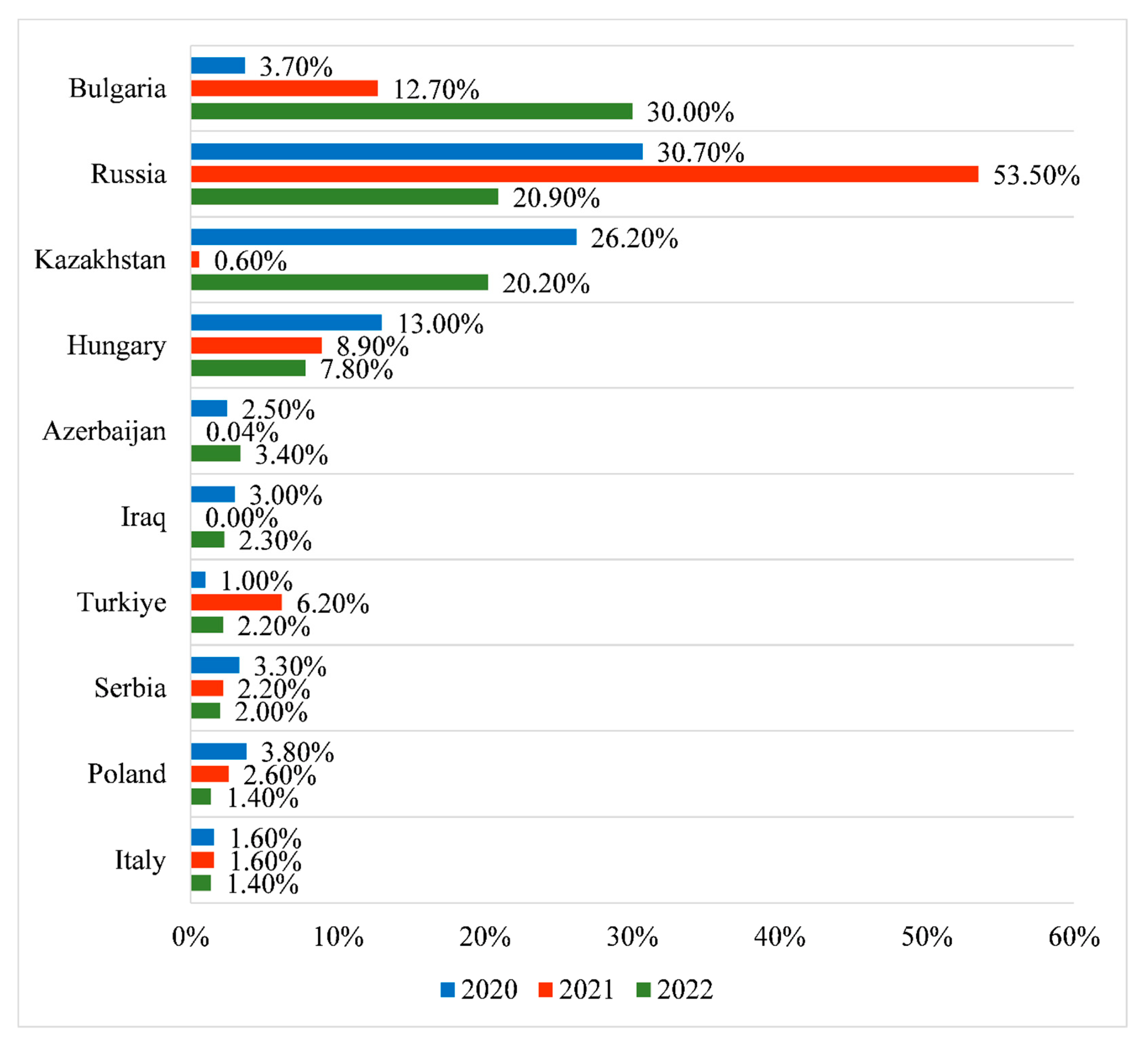

- energy imports from Russia decreased from 53.50% in 2021 to 20.90% in 2022 in Romania;

- Romania ended the import trend and exported electrical energy since July 2022 each consecutive month with efforts to become a regional provider.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Han, Y.; Jin, B.; Qi, X.; Zhou, H. Influential Factors and Spatiotemporal Characteristics of Carbon Intensity on Industrial Sectors in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cîrstea, S.D.; Martis, C.S.; Cîrstea, A.; Constantinescu-Dobra, A.; Fülöp, M.T. Current Situation and Future Perspectives of the Romanian Renewable Energy. Energies 2018, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busch, H.; Ruggiero, S.; Isakovic, A.; Hansen, T. Policy Challenges to Community Energy in the EU: A Systematic Review of the Scientific Literature. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 151, 111535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oprea, S.V.; Bâra, A.; Majstrovic, G. Aspects Referring Wind Energy Integration from the Power System Point of View in the Region of Southeast Europe. Study Case of Romania. Energies 2018, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Saidi, M. White Knight or Partner of Choice? The Ukraine War and the Role of the Middle East in the Energy Security of Europe. Energy Strateg. Rev. 2023, 49, 101116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, B.; Zhang, M. Evolutionary Game on International Energy Trade under the Russia-Ukraine Conflict. Energy Econ. 2023, 106827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vezzoni, R. Green Growth for Whom, How and Why? The REPowerEU Plan and the Inconsistencies of European Union Energy Policy. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2023, 101, 103134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EUROSTAT. Available online: https://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/submitViewTableAction.do (accessed on 7 September 2022).

- Bertsch, G.; Elliott-Gower, S. The Impact of Governments on East-West Economic Relations; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 1991; ISBN 978-1-349-12419-0. [Google Scholar]

- Koltsaklis, N.E.; Dagoumas, A.S.; Seritan, G.; Porumb, R. Energy Transition in the South East Europe: The Case of the Romanian Power System. Energy Reports 2020, 6, 2376–2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colesca, S.E.; Ciocoiu, C.N. An Overview of the Romanian Renewable Energy Sector. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 24, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popovici, V. 2010 Power Generation Sector Restructuring in Romania—A Critical Assessment. Energy Policy 2011, 39, 1845–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastasiu, N.; Simionescu, B.C.; Popa, M.E.; Mihai, M.; Rusu, R.D.; Predeanu, G. Romanian Coal Reserves and Strategic Trends. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2018, 198, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Năstase, G.; Şerban, A.; Florentina Năstase, A.; Dragomir, G.; Ionuţ Brezeanu, A.; Fani Iordan, N. Hydropower Development in Romania. A Review from Its Beginnings to the Present. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costea, G.; Pusch, M.T.; Bănăduc, D.; Cosmoiu, D.; Curtean-Bănăduc, A. A Review of Hydropower Plants in Romania: Distribution, Current Knowledge, and Their Effects on Fish in Headwater Streams. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 145, 111003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragomir, G.; Şerban, A.; NǍstase, G.; Brezeanu, A.I. Wind Energy in Romania: A Review from 2009 to 2016. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 64, 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Năstase, G.; Șerban, A.; Dragomir, G.; Brezeanu, A.I.; Bucur, I. Photovoltaic Development in Romania. Reviewing What Has Been Done. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 94, 523–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakeri, B.; Paulavets, K.; Barreto-Gomez, L.; Echeverri, L.G.; Pachauri, S.; Boza-Kiss, B.; Zimm, C.; Rogelj, J.; Creutzig, F.; Ürge-Vorsatz, D.; et al. Pandemic, War, and Global Energy Transitions. Energies 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osička, J.; Černoch, F. European Energy Politics after Ukraine: The Road Ahead. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2022, 91, 102757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umar, M.; Riaz, Y.; Yousaf, I. Impact of Russian-Ukraine War on Clean Energy, Conventional Energy, and Metal Markets: Evidence from Event Study Approach. Resour. Policy 2022, 79, 102966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Bouri, E.; Fareed, Z.; Dai, Y. Geopolitical Risk and the Systemic Risk in the Commodity Markets under the War in Ukraine. Financ. Res. Lett. 2022, 49, 103066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aharon, D.Y.; Qadan, M. Infection, Invasion, and Inflation: Recent Lessons. Financ. Res. Lett. 2022, 50, 103307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/ (accessed on 7 September 2022).

- Dhawan, M.; Choudhary, O.P.; Priyanka; Saied, A.A. Russo-Ukrainian War amid the COVID-19 Pandemic: Global Impact and Containment Strategy. Int. J. Surg. 2022, 102, 106675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Parliment News: “Renewable Energy: MEPs Strike Deal with Council to Boost Use of Green Energy”. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/press-room/20230327IPR78523/renewable-energy-meps-strike-deal-with-council-to-boost-use-of-green-energy (accessed on 7 July 2023).

- Röck, M.; Baldereschi, E.; Verellen, E.; Passer, A.; Sala, S.; Allacker, K. Environmental Modelling of Building Stocks – An Integrated Review of Life Cycle-Based Assessment Models to Support EU Policy Making. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 151, 111550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mišík, M.; Oravcová, V. Ex Ante Governance in the European Union: Energy and Climate Policy as a ‘Test Run’ for the Post-Pandemic Recovery. Energy Policy 2022, 167, 113076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delbeke, J.; Runge-Metzger, A.; Slingenberg, Y.; Werksman, J. The Paris Agreement. Towar. a Clim. Eur. Curbing Trend 2019, 24–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission: “European Climate Law”. Available online: https://climate.ec.europa.eu/eu-action/european-green-deal/european-climate-law_en (accessed on 7 July 2023).

- Filipović, S.; Lior, N.; Radovanović, M. The Green Deal – Just Transition and Sustainable Development Goals Nexus. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 168, 112759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Council: “Fit for 55”. Available online: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/green-deal/fit-for-55-the-eu-plan-for-a-green-transition/ (accessed on 28 July 2023).

- European Commision Plan REPowerEU; Bruxelles, 2022.

- European Parliment News: “Reducing Carbon Emissions: EU Targets and Policies”. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/headlines/society/20180305STO99003/reducing-carbon-emissions-eu-targets-and-policies?&at_campaign=20234-Green&at_medium=Google_Ads&at_platform=Search&at_creation=RSA&at_goal=TR_G&at_audience=carbon emissions&at_topic (accessed on 7 July 2023).

- Reuters: “EU Told to Slash Greenhouse Gas Emissions 90-95% by 2040”. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/sustainability/eu-told-slash-greenhouse-gas-emissions-90-95-by-2040-2023-06-14/ (accessed on 7 July 2023).

- Financial Times. Available online: https://www.ft.com/content/2624cc0f-57b9-4142-8bc1-4141833a73dd (accessed on 7 September 2022).

- European Commission: “REPowerEU”. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal/repowereu-affordable-secure-and-sustainable-energy-europe_en (accessed on 8 July 2023).

- Alam, H.A.; Kottasová, I.; Dewan, A.; Ramirez, R. CNN. Available online: https://edition.cnn.com/2022/07/06/world/eu-votes-natural-gas-nuclear-green-sustainable-climate/index.html (accessed on 28 July 2022).

- Fortune: “The EU Is Calling Natural Gas ‘Green,’ but Critics Aren’t Buying It”. Available online: https://fortune.com/2022/08/08/eu-calls-natural-gas-green-critics-dont-buy-it/ (accessed on 8 July 2023).

- Abnett, K.; Strauss, M. REUTERS. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/business/sustainable-business/eu-parliament-supports-green-label-gas-nuclear-investments-2022-07-06/ (accessed on 22 July 2022).

- POWER: “Europe Ramps Renewables, Looks for New Gas to Reduce Reliance on Russia”. Available online: https://www.powermag.com/europe-ramps-renewables-looks-for-new-gas-to-reduce-reliance-on-russia/ (accessed on 8 July 2023).

- Energy Monitor: “Europe: Renewables in 2022 in Five Charts – and What to Expect in 2023”. Available online: https://www.energymonitor.ai/tech/renewables/europe-renewables-in-2022-in-five-charts-and-what-to-expect-in-2023/ (accessed on 8 July 2023).

- EMBER: “European Electricity Review 2023”. Available online: https://ember-climate.org/insights/research/european-electricity-review-2023/ (accessed on 8 July 2023).

- Umit, R.; Schaffer, L.M. Attitudes towards Carbon Taxes across Europe: The Role of Perceived Uncertainty and Self-Interest. Energy Policy 2020, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braungardt, S.; Tezak, B.; Rosenow, J.; Bürger, V. Banning Boilers: An Analysis of Existing Regulations to Phase out Fossil Fuel Heating in the EU. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 183, 113442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tax Foundation: “Carbon Taxes in Europe”. Available online: https://taxfoundation.org/carbon-taxes-in-europe-2022/ (accessed on 8 July 2023).

- Ferrara, A.R.; Giua, L. Indirect Cost Compensation under the EU ETS: A Firm-Level Analysis. Energy Policy 2022, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The World Bank: “Carbon Pricing”. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/programs/pricing-carbon (accessed on 8 July 2023).

- Nadirov, O.; Vychytilová, J.; Dehning, B. Carbon Taxes and the Composition of New Passenger Car Sales in Europe. Energies 2020, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank, “Carbon Pricing Dashboard”. Available online: https://carbonpricingdashboard.worldbank.org/ (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- Union, E. Consolidated Versions of the Treaty on European Union and of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union: Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union; Office for Official publications of the European Communities, 2010; ISBN 9282425770.

- Matlary, J.H. Energy Policy in the European Union; Springer, 1997; ISBN 0333643496.

- Cernat, F.; Nica, M.; Dãdârlat, A. Agerpres - Electrican Energy Production Capacity in Romania. Available online: https://www.agerpres.ro/economic-intern/2022/03/13/romania-are-o-capacitate-de-productie-a-energiei-electrice-de-18-545-mw--883323 (accessed on 24 July 2022).

- Institutul Național de Statistică: “Statistica Energiei”. Available online: https://insse.ro/cms/ro/content/statistica-energiei (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- E.E.M.A., M. Strategia Energetică a României 2020-2030 , Cu Perspectiva Anului 2050. 2020, 72.

- Davis, M.; Okunlola, A.; Di Lullo, G.; Giwa, T.; Kumar, A. Greenhouse Gas Reduction Potential and Cost-Effectiveness of Economy-Wide Hydrogen-Natural Gas Blending for Energy End Uses. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 171, 112962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caspian News: “Azerbaijan Boosts Natural Gas Exports to European Markets”. Available online: https://caspiannews.com/news-detail/azerbaijan-boosts-natural-gas-exports-to-european-markets-2023-5-25-0/ (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- Economica: “Linia Electrică Suceava-Bălți, Prin Care Rețeaua Republicii Moldova Se Leagă La Cea Româneacă, Pe Lista Cu Proiecte Propuse de România Pentru Finanțare Din RePowerEU”. Available online: https://www.economica.net/linia-electrica-suceava-balti-prin-care-reteaua-republicii-moldova-se-leaga-la-cea-romaneaca-pe-lista-cu-proiecte-propuse-de-romania-pentru-finantare-din-repowereu_655289.html (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- Three Seas Projects: “BRUA”. Available online: https://projects.3seas.eu/projects/brua-development-on-the-territory-of-romania-of-the-national-gas-transmission-system-along-the-corridor-bulgaria-romania-hungary-austria-(brua-phase-1-and-2)-and-enhancement-of-the-bidirectional-gas-transmission-corridor (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- SNTGN TRANSGAZ SA MEDIAŞ Planul de Dezvoltare a Sistemului Național de Transport Gaze Naturale 2021-2030. 2021.

- Transelectrica - Romanian Electrical Energy Transport and System Operator. Available online: https://web.transelectrica.ro/harti_crd_tel/ (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Romanian Law 157/2022. Available online: https://legislatie.just.ro/Public/DetaliiDocumentAfis/255688 (accessed on 28 July 2023).

- Caleaeuropeana: “OMV Petrom a Descoperit Noi Resurse de Țiței Și Gaze Naturale În Oltenia Și Muntenia. Descoperirile Se Ridică La Peste 30 Milioane Bep”. Available online: https://www.caleaeuropeana.ro/omv-petrom-a-descoperit-noi-resurse-de-titei-si-gaze-naturale-in-oltenia-si-muntenia-descoperirile-se-ridica-la-peste-30-milioane-bep/ (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- Euronews: "România va Extrage Gaze Din Marea Neagră În Aproape Patru Ani. ”Va Deveni Un Jucător Pe Piaţa Regională” Informaţiile Publicate de <a Href="Https://Euronews.Ro">euronews.Ro</A> Pot Fi Preluate Doar În Limita a 500 de Caractere Şi Cu Citarea În. Available online: https://www.euronews.ro/articole/romania-va-extrage-gaze-din-marea-neagra-in-aproape-patru-ani-va-deveni-un-jucato (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- European Commission: “Energy Efficiency Directive”. Available online: https://energy.ec.europa.eu/topics/energy-efficiency/energy-efficiency-targets-directive-and-rules/energy-efficiency-directive_en (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- European Environment Agency: “Energy Efficiency”. Available online: https://climate-energy.eea.europa.eu/topics/energy-1/energy-efficiency/data/energy-efficiency (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- Eurostat: “Energy Statistics”. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Energy_statistics_-_an_overview (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- European Council on Foreign Relations: "Conscious Uncoupling: Europeans’ Russian Gas Challenge in 2023". Available online: https://ecfr.eu/article/conscious-uncoupling-europeans-russian-gas-challenge-in-2023/ (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- Eurostat: “Mar '23: EU Slashes Russian Oil; Emergency Stocks up”. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/w/ddn-20230619-3 (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- Statista: “Volume of Energy Imports from Russia to the European Union (EU) from 2018 to 2022, by Product”. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1302646/eu-energy-import-volume-from-russia-by-product/ (accessed on 25 July 2023).

- Tsemekidi Tzeiranaki, S.; Economidou, M.; Bertoldi, P.; Thiel, C.; Fontaras, G.; Clementi, E.L.; Franco De Los Rios, C. “The Impact of Energy Efficiency and Decarbonisation Policies on the European Road Transport Sector.”. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2023, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ember: “European Electricity Review 2022”. Available online: https://ember-climate.org/insights/research/european-electricity-review-2022/ (accessed on 19 July 2023).

- European Commission Romania Energy Snapshot. 2022.

- Transelectrica: “Production, Consumption and Sold Energy from Romanian Electrical System”. Available online: https://www.transelectrica.ro/widget/web/tel/sen-grafic/-/SENGrafic_WAR_SENGraficportlet (accessed on 19 July 2023).

- Romanian National Statistics Institute: “Households Fund”. Available online: https://insse.ro/cms/ro/content/fondul-de-locuinţe-6 (accessed on 2 August 2023).

- National Institute of Statistics. Available online: https://insse.ro/cms/ro/search/node/lemn?page=2 (accessed on 9 September 2022).

- Romanian Forestry Code. Available online: https://lege5.ro/Gratuit/geztkojz/raspunderi-si-sanctiuni-codul-silvic?dp=giztgobwhe3ds (accessed on 2 August 2023).

- Statistica: “Final Energy Consumption in Romania from 2017 to 2021, by Sector”. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1383110/romania-final-energy-consumption-2021-by-sector/ (accessed on 19 July 2023).

- Mungiu-Pippidi, A.; Dusu, A.E. Civil Society and Control of Corruption: Assessing Governance of Romanian Public Universities. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2011, 31, 532–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pârvu, L. Hotnews. Available online: https://www.hotnews.ro/stiri-politic-25423001-virgil-popescu-romania-nu-redeschide-alte-mine-creste-capacitatea-extractie-carbunelui-complexul-energetic-oltenia.htm (accessed on 25 July 2022).

- Romanian Energy System. Available online: https://www.sistemulenergetic.ro/ (accessed on 24 July 2022).

- Romanian National Energy Regulatory Authority. Available online: https://www.anre.ro/ro/energie-electrica/rapoarte/puterea-instalata-in-capacitatiile-de-productie-energie-electrica (accessed on 28 July 2022).

- National Energy Regulatory Authority in Romania. Available online: https://www.anre.ro/ro/gaze-naturale/rapoarte/rapoarte-piata-gaze-naturale (accessed on 9 September 2022).

- Cristian, A. Europa Liberă România. Available online: https://romania.europalibera.org/a/rusia-taie-gazul-de-unde-importa-romania/31823857.html (accessed on 9 September 2022).

- Gazprom: “About Us”. Available online: https://www.gazprom-international.com/about/ (accessed on 28 July 2023).

- Ionescu, A. Revista Cronicile. Available online: https://cursdeguvernare.ro/romania-import-net-electricitate-2021-mai-mare-2019-nu-economie.html (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Statistica: “Distribution of Energy Products Imported in Romania from 2020 to 2022, by Country”. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1385210/romania-distribution-of-energy-products-imported-by-country/ (accessed on 20 July 2023).

- Statistica: “Dependency Rate on Energy Imports in Romania from 2000 to 2021”. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/691184/dependency-on-energy-imports-in-romania/ (accessed on 20 July 2023).

- Digi24. Available online: https://www.digi24.ro/stiri/economie/turbinele-eoliene-nu-pot-fi-amplasate-in-marea-neagra-pentru-ca-nu-se-stie-care-este-institutia-care-concesioneaza-suprafetele-1578165 (accessed on 25 July 2022).

- Romania Solar Photovoltaic (PV) Market Size and Trends by Installed Capacity, Generation and Technology, Regulations, Power Plants, Key Players and Forecast, 2021-2030. Available online: https://www.globaldata.com/store/report/romania-solar-pv-market-analysis/ (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Transelectrica: “Available Electrical Connection Capacities Map in Romania”. Available online: https://web.transelectrica.ro/harti_crd_tel/ (accessed on 25 July 2023).

- Professional Electrician: “‘Prosumer’ Electrical Installations”. Available online: https://professional-electrician.com/technical/prosumer-electrical-installations-what-are-they-eca/ (accessed on 19 July 2023).

- ANRE: “Ghidul Prosumatorului Cu Capacitate de Cel Mult 400 KW Pe Loc de Consum”. Available online: https://anre.ro/informare-de-presa-15-11-2022-ghidul-prosumatorului-cu-capacitate-de-cel-mult-400-kw-pe-loc-de-consum-a-fost-actualizat/ (accessed on 19 July 2023).

- Administrația Fondului Pentru Mediu: “Casa Verde Fotovoltaice 2023”. Available online: https://www.afm.ro/sisteme_fotovoltaice.php (accessed on 19 July 2023).

- Romanian Government: “Energy Ministry”. Available online: https://energie.gov.ro/category/electricup/ (accessed on 19 July 2023).

- Electric Up Dashboard. Available online: https://lookerstudio.google.com/u/0/reporting/1a9fa5b6-b1ae-4211-aa6f-39bf303a2d7b/page/TnEJD (accessed on 19 July 2023).

- Gherasi, N.; Marinescu, A.; Ivaşcu, A. Agerpres - Hidroelectrica Modernisation Projects. Available online: https://www.agerpres.ro/economic-intern/2020/05/15/hidroelectrica-are-proiecte-de-retehnologizare-si-modernizare-in-suma-de-circa-3-miliarde-de-lei--506528 (accessed on 24 July 2022).

- European Parliament News: “Parliament Gives Go-Ahead to €672.5 Billion Recovery and Resilience Facility”. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/press-room/20210204IPR97105/parliament-gives-go-ahead-to-EU672-5-billion-recovery-and-resilience-facility (accessed on 19 July 2023).

- Nechifor, M. Infoclima - Solar Energy in Romania. Available online: https://www.infoclima.ro/acasa/energia-solara-romnia-cum-nu-observam-potenialul (accessed on 27 July 2022).

- EPB Center: “The Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EPBD)”. Available online: https://epb.center/epb-standards/energy-performance-buildings-directive-epbd/ (accessed on 20 July 2023).

- European Commission: “Building Stock”. Available online: https://building-stock-observatory.energy.ec.europa.eu/database/ (accessed on 19 July 2023).

- Parliament, E. Energy Performance of Buildings (Recast) Amendments Adopted by the European Parliament on 14 March 2023 on the Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on the Energy Performance of Buildings (Recast) (COM(2021)0802 – C9-0469/. Representation 2023, 128. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission: “Energy Performance of Buildings Directive”. Available online: https://energy.ec.europa.eu/topics/energy-efficiency/energy-efficient-buildings/energy-performance-buildings-directive_en (accessed on 18 July 2023).

- Reuters: “Europe’s Buildings in Line for Energy-Saving Overhaul”. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/europes-buildings-line-energy-saving-overhaul-2021-12-15/ (accessed on 20 July 2023).

- Fuinhas, J.A.; Koengkan, M.; Silva, N.; Kazemzadeh, E.; Auza, A.; Santiago, R.; Teixeira, M.; Osmani, F. The Impact of Energy Policies on the Energy Efficiency Performance of Residential Properties in Portugal. Energies 2022, 15, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EnergoCertif: “Clase Energetice Clădiri”. Available online: http://energocertif.ro/clase-energetice-cladiri/ (accessed on 20 July 2023).

- Romanian Government Strategia Națională De Renovare Pe Termen Lung; Bucharest.

- Romanian Energy Ministry Strategia Energetica a Romaniei 2016-2030, Cu Perspectiva Anului 2050 2016, 116.

- EPG; ROENEF Creșterea Eficienței Energetice În Clădiri În România: Provocări, Oportunități Și Recomandări de Politici. 2018.

- EurObserv’ER Baromètres Solaire Thermique & Solaire Thermodynamique 2022. Available online: https://www.eurobserv-er.org/barometres-solaire-thermique-solaire-thermodynamique-2022/ (accessed on 24 July 2022).

- Eurostat: “Air Emissions Accounts for Greenhouse Gases by NACE Rev. 2 Activity - Quarterly Data”. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/env_ac_aigg_q/default/table?lang=en (accessed on 18 July 2023).

- Paris, B.; Vandorou, F.; Balafoutis, A.T.; Vaiopoulos, K.; Kyriakarakos, G.; Manolakos, D.; Papadakis, G. Energy Use in Open-Field Agriculture in the EU: A Critical Review Recommending Energy Efficiency Measures and Renewable Energy Sources Adoption. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 158, 112098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Environment Acengy: “Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Energy Use in Buildings in Europe”. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/ims/greenhouse-gas-emissions-from-energy (accessed on 18 July 2023).

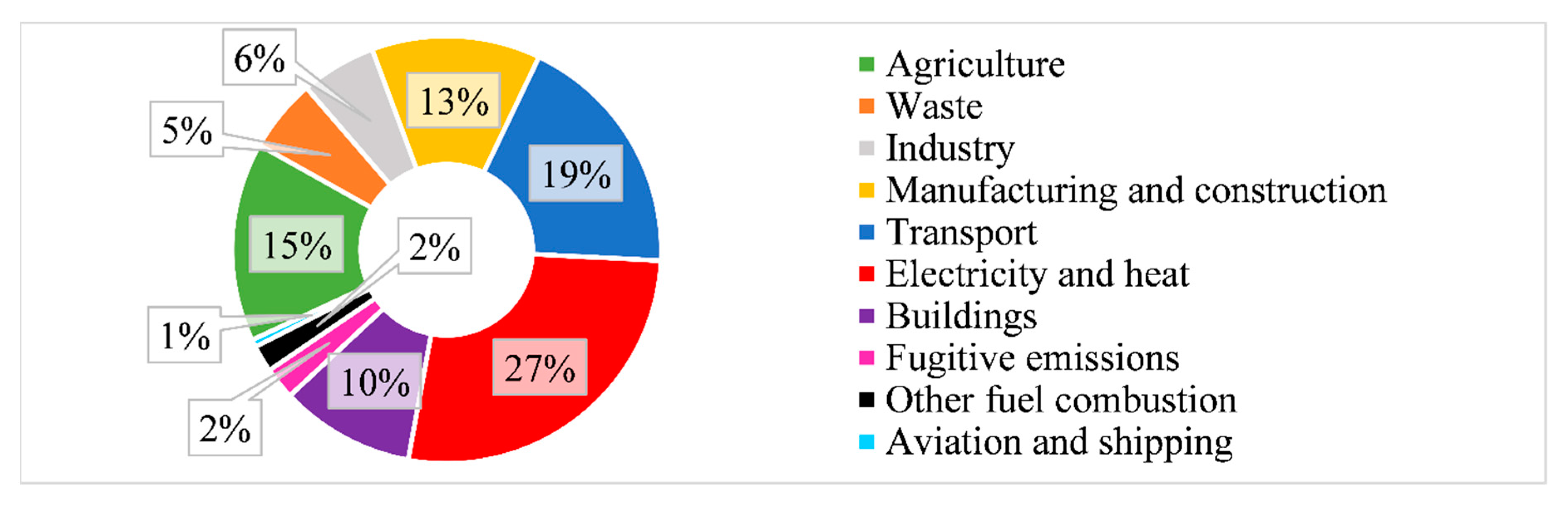

- Our World in Data: “Greenhouse Gas Emissions by Sector, Romania, 2019”. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/ghg-emissions-by-sector?time=latest&country=~ROU (accessed on 20 July 2023).

| No. | Objective |

|---|---|

| 1 | Ensuring access to electricity and heat for all consumers |

| 2 | Clean energy and energy efficiency |

| 3 | Modernization of the corporate governance system and the institutional regulatory capacity |

| 4 | Protecting the vulnerable consumer and reducing energy poverty |

| 5 | Competitive energy markets, the basis of a competitive economy |

| 6 | Increasing the quality of energy education and the continuous training of qualified human resources |

| 7 | Romania, regional energy security provider |

| 8 | Increasing Romania’s energy contribution on regional and European markets by capitalizing on national primary energy resources |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).