1. Introduction

Since the 1970s, the ethical concern regarding our relationship with animals has shifted from relatively limitated [

1] to progressively growing, almost exponentially, in recent times [

2,

3,

4]. This surge has directly impacted legislation, making it increasingly protective of animal welfare [

5]. Human ethics are crucial as they can justify obligations towards animals [

6,

7,

8] and are rooted in Ethics or Moral Philosophy [

9] by addressing imperatives that compel humans to act in specific ways ([

10]. Yet, understanding animal biology is necessary when delineating these obligations [

11,

12].

A significant ethical consideration is firmly rooted in society's agreement that animals shouldn’t suffer [

13,

14]. However, the extent to which animals can be utilized as models in clinical trials for human pain treatment raises questions [

15,

16]. While not delving into animal suffering and consciousness, no harm should be caused to animals, including that which may arise from their participation in human entertainment activities [

17,

18,

19]. Legal considerations, or alternatively, deontological aspects, further add to these debates [

20]. The Five-Domains Model for animal welfare assessment en compasses scientific issues relate to this discipline [

21], however, it can also be used in conjunction with ethical theories to clarify our relationship with animals in various production or entertainment contexts [

22,

23,

24].

It is also necessary to differentiate between animal welfare and the ethical issue arising from our coexistence with nonhuman sentient beings capable of experiencing physical suffering. Animal welfare involves an organism whose neuroendocrine system, akin to humans, should not exhibit physiological alterations. Emotional manifestations (e.g., fear or stress) should not deviate from what occurs in normal conditions [

25,

26,

27]. Practically, welfare is assessed through animal behavior observation [

28]. Positive human-animal relationships have been highlighted by several authors to contribute intrinsically to animal welfare [

29,

30,

31,

32].

The Five Domains Model (since 1994) for animal welfare assessment provides specific guidance on how to evaluate the negative and/or positive impacts of human behavior on animals [

21]. This model facilitates systematic and structured assessment of positive as well as negative welfare-related affects, the circumstances that give rise to them and potential interactions between both types of affects, all of which extend the utility of the model [

33]. The Five Domains are clearly of use to animal behavior and welfare scientists because they can embrace new knowledge and understanding and provide pointers for new study. They can also be used for in-depth analysis of the impact of specific management practices (human actions) on animal welfare [

34].

Numerous ethical theories focus on the human-animal bond, with most centered-on animal suffering [

4,

35]. The theory of reciprocal recognition suggests avoiding animal cruelty by recognizing the harm caused, considering both animal and human interests [

36]. This ideology aligns with a derivative of utilitarianism [

37,

38], which advocates maximizing pleasure and minimizing suffering for sentient beings—forming the basis of ethics and obligations towards animals [

18,

39,

40]. Such utilitarianism is common among professionals working with animals, aiming to prevent suffering and enhance animal welfare in livestock production [

28,

41].

The responsibility to ensure animal welfare is rooted in the established fact that animals experience physical pain and suffering [

16,

42]. Therefore, causing unjustified suffering, such as in entertainment involving cruelty, mistreatment, or unnatural conditions contrary to their physiological and behavioral needs, is not morally acceptable [

6].

University education in agronomy promotes the human-animal bond in a practical academic learning environment, sensitizing students to animal welfare as they progress through their study programs [

43], considering socio-demographic attributes of the student population. This study aimed to determine the perceptions of agronomy university students concerning animal welfare in livestock production systems.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source

The data used was collected from the Animal Welfare survey administered to students majoring in Agronomy Engineering at the Costa Rica Institute of Technology (ITCR) as part of an exploratory study on attitudes, behaviors, and perceptions toward animal welfare and meat consumption among Agronomy Engineering students at ITCR between May and July 2023. The survey gathered a wide range of information, including the participants' sociodemographic aspects, interaction with pet animals, general information about animal welfare, knowledge on the ethical dimension of animal welfare, consumption of animal products, consumption of meat and other animal-derived meat products, as well as attitudes towards meat products within animal welfare considerations. The data is available on the Open Science Framework. All interviewees were 18 years or older.

2.2. Data Collection

Data were collected in person through a survey. Prior to this, each participant was sent a consent form for participation, use of collected information, and data treatment within the framework of the research study. From the total respondents (n = 150), students who did not consent to participate in the research or were under 18 years old (n = 6) were excluded from the statistical analysis. A total of 144 surveys were analyzed.

The questionnaire comprised four parts distributed as follows: 1) Participant sociodemographic aspects, 2) Generalities on animal welfare, 3) Ethical and bioethics dimension of animal welfare, and 4) Animal welfare within the framework of bio-law.

To develop the questionnaire, recommendations were followed to maintain the wording as simple and direct as possible, using symmetric response scales and framing elements both positively and negatively. Moreover, an expert consultation phase was included before the questionnaire's administration. Regarding differences in response scale usage, the recommendations were to employ symmetric bipolar response scales with a clear midpoint.

2.3. Measures

In the present paper, the sociodemographic variables are gender, age, career level, upbringing environment, and income. The remaining questions were selected and categorized into three thematic groups: 1) ethical, consisting of 7 questions; 2) bioethical, 5 questions, and 3) legal, 5 questions. All responses are categorical.

The survey comprised questions related to the ethical, bioethical, and legal dimensions of animal welfare that were utilized in this study. Participants were asked various questions regarding animal use. Additionally, inquiries were made about suffering, sentience, and cruelty toward nonhuman animals, addressing the ethical, bioethical, and legal dimensions of animal welfare that extend beyond livestock production. Participants responded to items on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (very good) to 5 (very bad). Subsequently, responses were recoded into good or bad and yes or no categories.

2.4. Perceived Animal Ethics, Bioethics and Legal Issues

Agronomy engineering students were surveyed on topics related to animal ethics to understand perceptions based on sociodemographic variables such as gender, age, education level, geographic origin, and income. The questions are as follows:

"In general, how do you believe farm animals are treated?"

"Provide an assessment of how you believe the following farm animals are generally treated."

"Would you be willing to pay more for a product if it helped improve animal welfare?"

"Do you believe humans should be respectful towards animals?"

"Do you consider animal cruelty to be a condemnable behavior?"

"Do you consider it ethical and responsible for social movements to aim at using 'humane' methods to exterminate crop pests?"

"How do you assess the act of humans killing other animals for food?"

The questions related to life sciences and the interaction animal sciences and environment that could form the bioethical foundations of agronomy students were:

“How would you rate your level of concern for animal welfare?”

“Regarding animal suffering, do you believe some animals are more valuable than others?”

“How do you assess nonhuman animals preying on each other?”

“How do you assess animal research, specifically using them as models in trials to test new drugs for humans?”

“How do you feel about the idea of witnessing an animal suffer?”

The questions related to legal and regulatory aspects that could contribute to developing the argumentation on animal welfare within the framework of bio-law among agronomy students were as follows:

“Do you find it ethical to practice "hunting" sports while complying with established regulations for it? “

“Do you consider that animals subjected to hunting (even when each country's regulations are followed) limit their well-being?”

“If you admit that animals should not suffer, would you be willing to use animals in scientific experimentation as models for the study of human diseases?”

"If you acknowledge that animals are not mere objects, do you believe that animals should be granted 'rights'?"

“Do you consider granting rights as the only way to protect the interests of animals?”

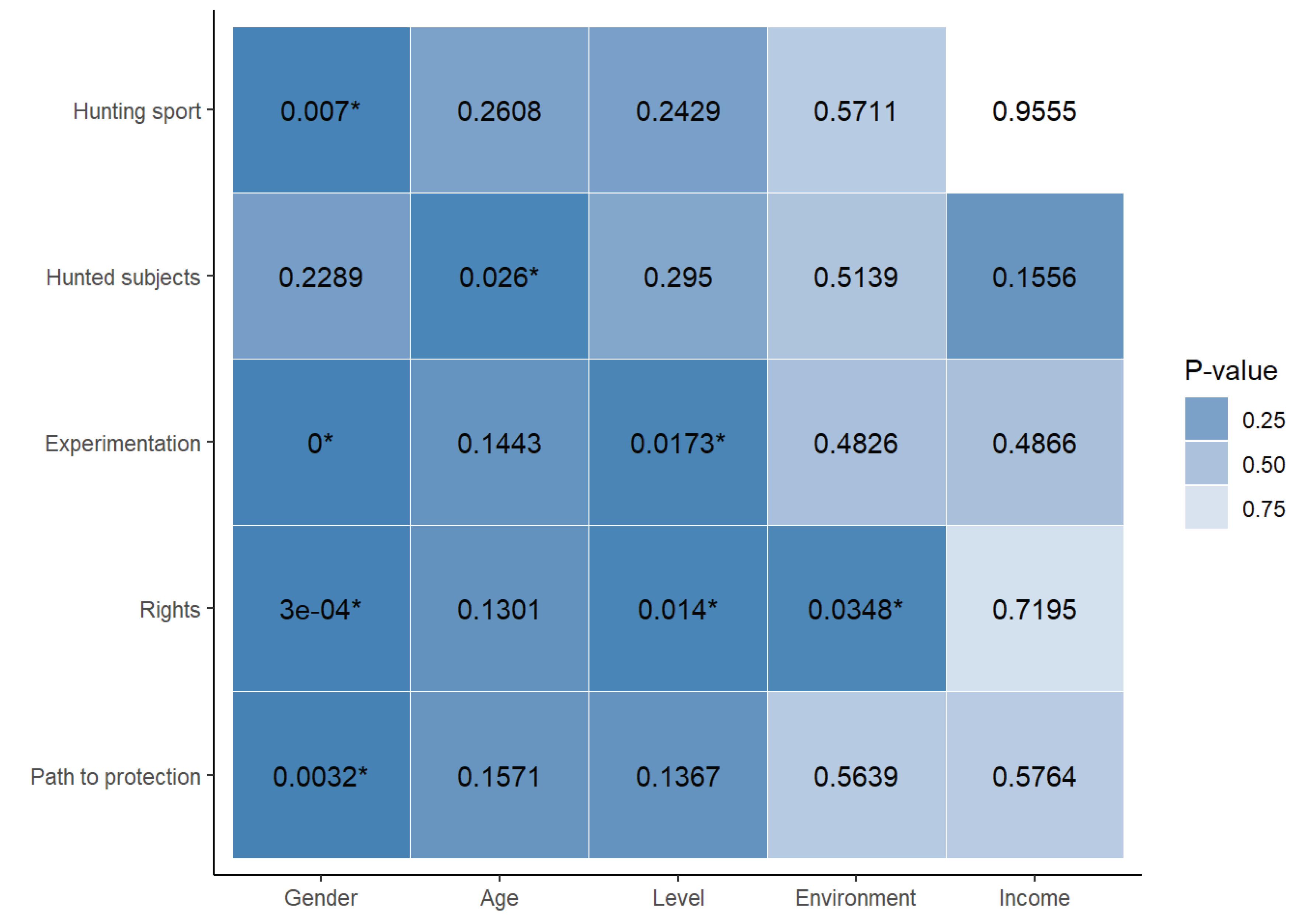

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed in R version 4.3.1 [

44] and RStudio version 2022.7.1.554 [

45], using packages ggplot2 [

46] for figures and gtsummary [

47] for tables. The Chi-square test of independence was used to assess the association between the participants' characteristics and each question within the thematic groups. In cases where the expected frequency was less than 5, the Fisher's exact test was employed, and statistical significance was determined as a p value below 0.05. When skewness was present, response categories were collapsed to the subsequent level.

2.4.1. Quantitative Analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using R software (v4.2.2, R Core Team, 2021), and summary statistics were computed for all variables of interest. Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were used to analyze all Likert scale questions to determine if students' responses differed among them. For each question, Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were conducted with the five Likert scale categories included (i.e., 1 = High; 2 = Medium or Low) or (1 = Yes, 2 = No, 3 = I am indifferent).

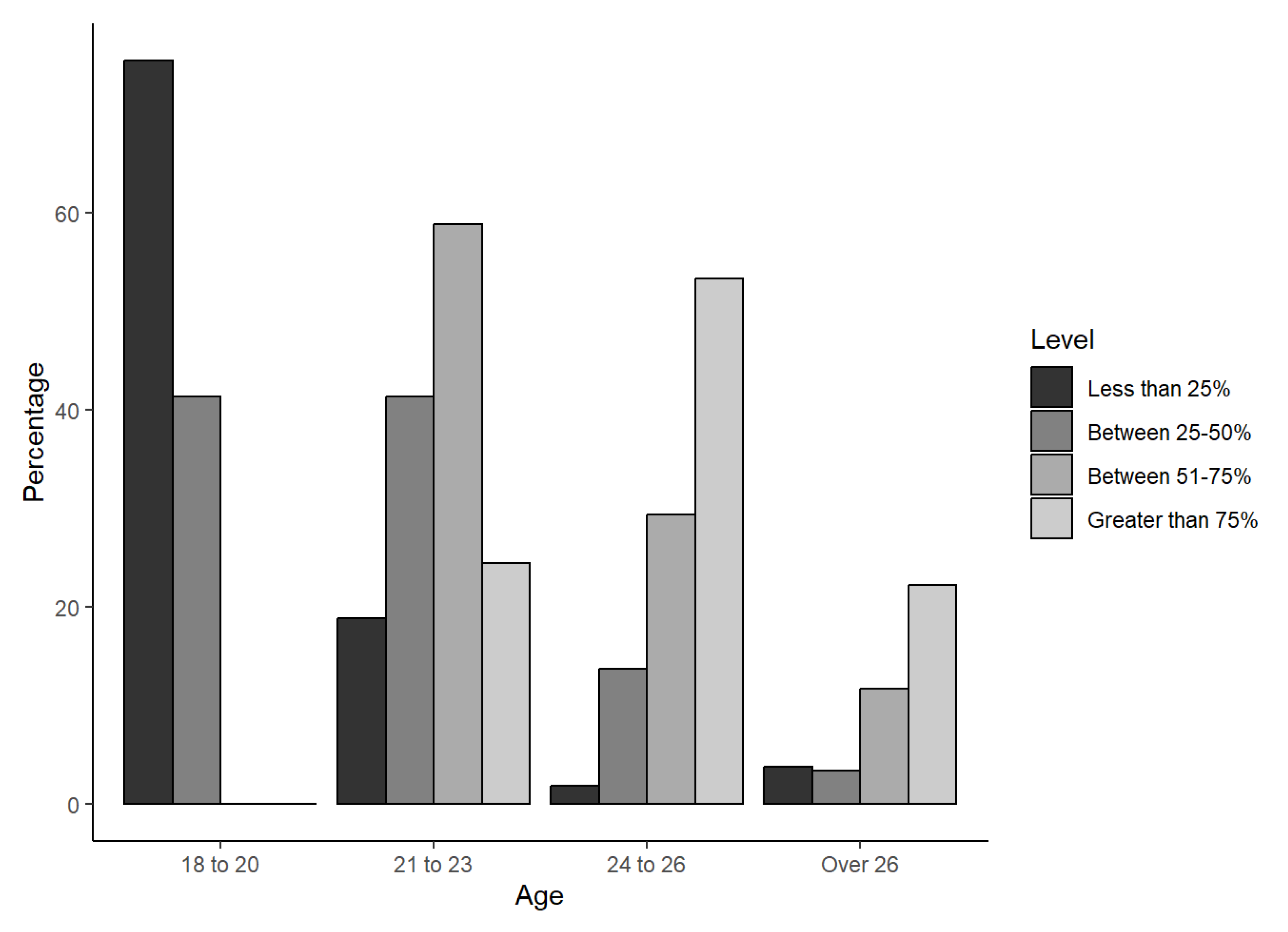

Based on the results of the Wilcoxon signed-rank test, only questions that were significantly different from each other (p < 0.05) were further analyzed. Ordinal logistic regression assuming proportional odds was employed to assess the relationship between Likert responses and respondents' demographic factors. Demographic factors considered for regression analysis were gender (male or female), age in years (18-20; 21-23; 24-26; over 26), progression level in the agronomy curriculum (less than 25%; between 25-50%; between 51-75%; over 75%), hometown type (rural or urban), agricultural background (originating from a farm or not), and experience with animals (yes or no). Model selection was performed through backward elimination based on parameter significance (P ≤ 0.05), retaining only significant parameters in the final models.

4. Discussion

Animal welfare is currently a fundamental component of animal production systems [

3,

35,

48] because it directly impacts the quality of meat, milk, eggs, wool, leather, and all derivatives thereof industries. Typically, agronomical engineering schools in Costa Rica do not offer courses on animal welfare in their curricula; instead, they focus on livestock production in theoretical and practical courses on production systems. The results of this study indicate that most undergraduate agronomy students stated that animal welfare was important within livestock production systems. This assessment aligns with the widespread social perception of how animals should be treated, where animal welfare involves reducing suffering in different livestock production systems [

49]. The notion that causing animals to suffer is not acceptable is an ethical judgment that the science of animal welfare can utilize to promote the necessity for improving welfare to benefit the groups associated with the livestock industry and all recognized forms of human-animal relationships [

50,

51].

The study results highlight differences in animal welfare perceptions among animal categories. The variability in students' perceptions regarding the treatment of different animal species may be explained by the level of interaction individuals have with specific species due to their upbringing or environment. Various studies have demonstrated that experience in an agricultural or rural context and being male diminish perceptions of the importance of animal welfare [

52,

53,

54]. However, several socio-demographic factors can influence individual perceptions of animal welfare. This underscores a somewhat variable sense of responsibility toward certain animal species, especially regarding wildlife or domestic species used in food production [

55,

56,

57].

Understanding what perspectives could underlie perceptions and assessments on livestock non-human animals is relevant aimed at proposing new teaching activities, materials, and research [

58]. We find two general positions currently, with different variants: the first one claims that human beings are different from the other species (we may call it anthropologism instead of anthropocentrism); there are some variants of this position [

59,

60]. Here we adopt, without any further analysis, that there exist biological species, as claimed, for example, by biological taxonomists [

61].

The second position considers that human being is part of the order of nature [

62]. It is claimed that we share with other species most aspects including biological mechanisms, ingredients of life, and even cognitive structures [

63]. It does not claim that capabilities are the same along the natural order, but that different species share them with different degrees and differences [

64].

When our results about perceptions were analyzed, most respondents held positive attitudes toward improving animal welfare [

65,

66]. These perceptions were linked to key concepts: animal suffering, animal research, willingness to pay for products with guaranteed animal welfare, using 'humane' methods for crop pest control, and the moral conception of harvesting animals for meat consumption and animal-origin products. It is ethically desirable to address moral arbitrariness where they were not previously found, due to considering them as natural variation [

67]. If we acknowledge that animal suffering poses an ethical issue, we must investigate when and how animals suffer to address the problem based on evidence [

14,

16]. Here, we must employ the scientific method to conduct experiments associating the results with our current understanding in fields such as zoology, animal husbandry, genetics, evolutionary biology, and all sciences focused on living organisms. Livestock production is often criticized for certain animal management practices, such as confinement systems and procedures like castration or dehorning are controversial [

68,

69]. This awareness is evident among students and reflects in their ethical and bioethical perceptions regarding welfare and nonhuman animal suffering. However, this tends to increase as they progress through the agronomy curriculum. Regarding nonhuman animal suffering, it cannot be claimed that avoiding suffering makes a good person due to the recognition of their right “not to suffer”, because these are different categories [

13], not extended on this article.

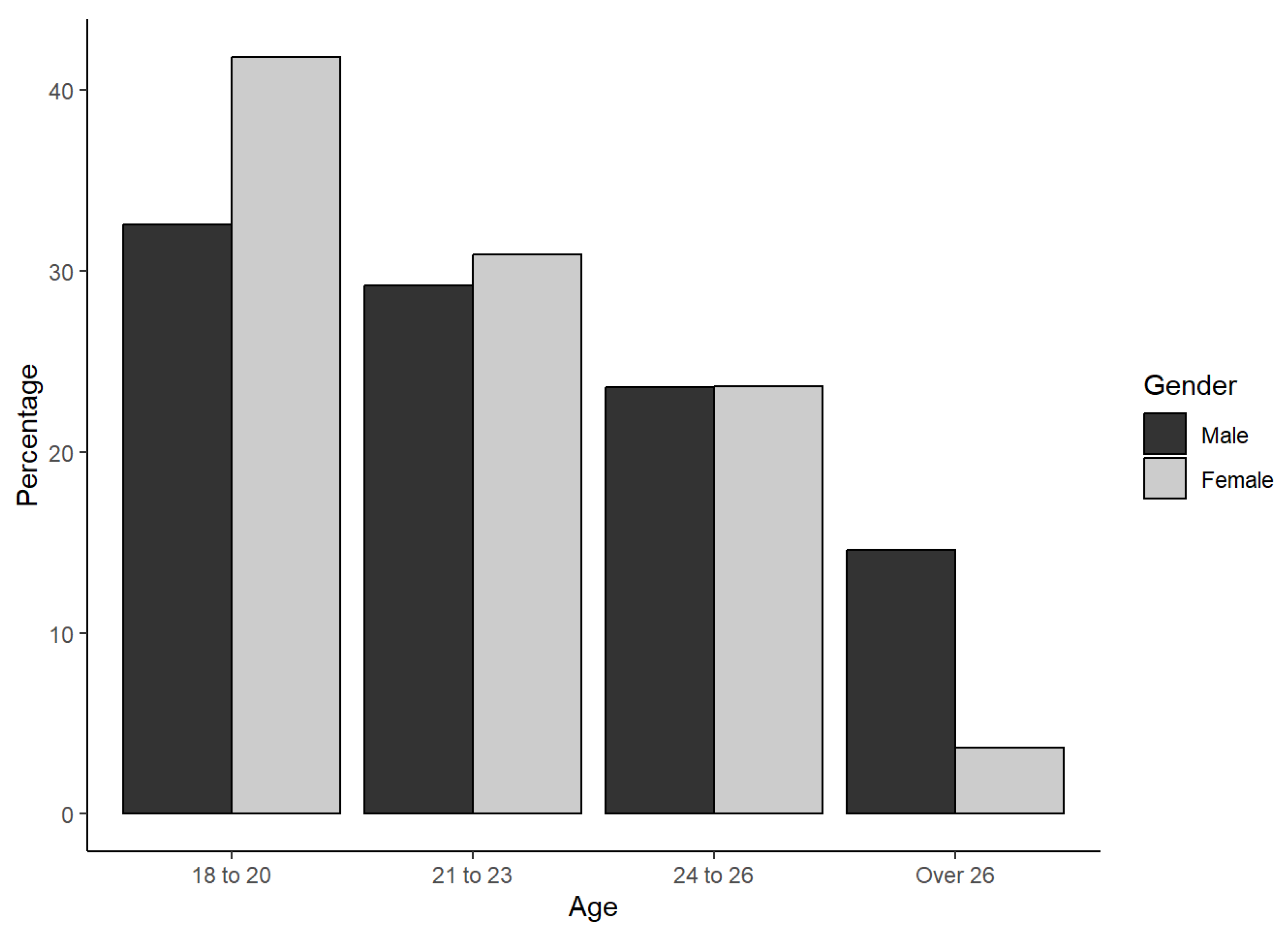

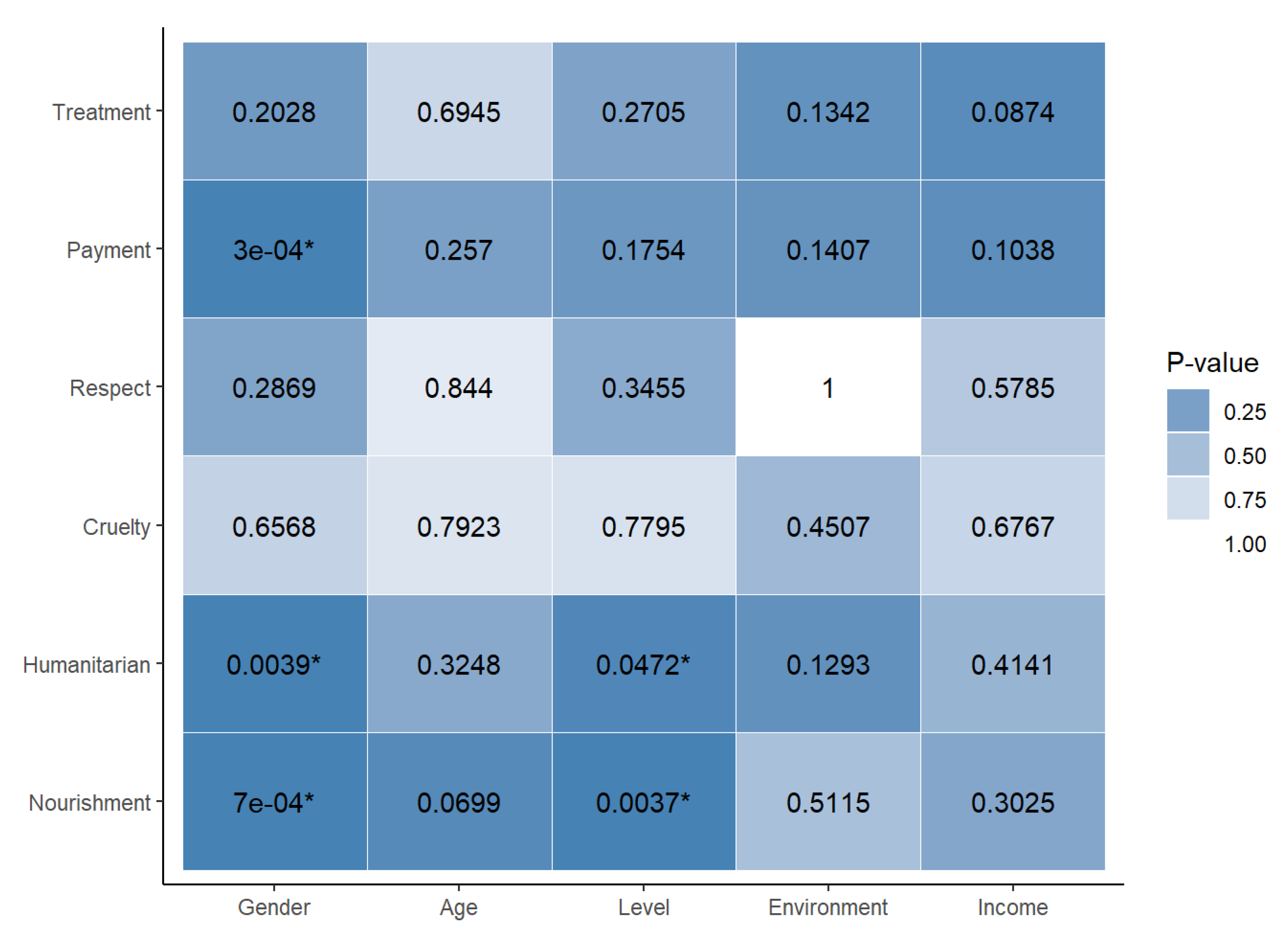

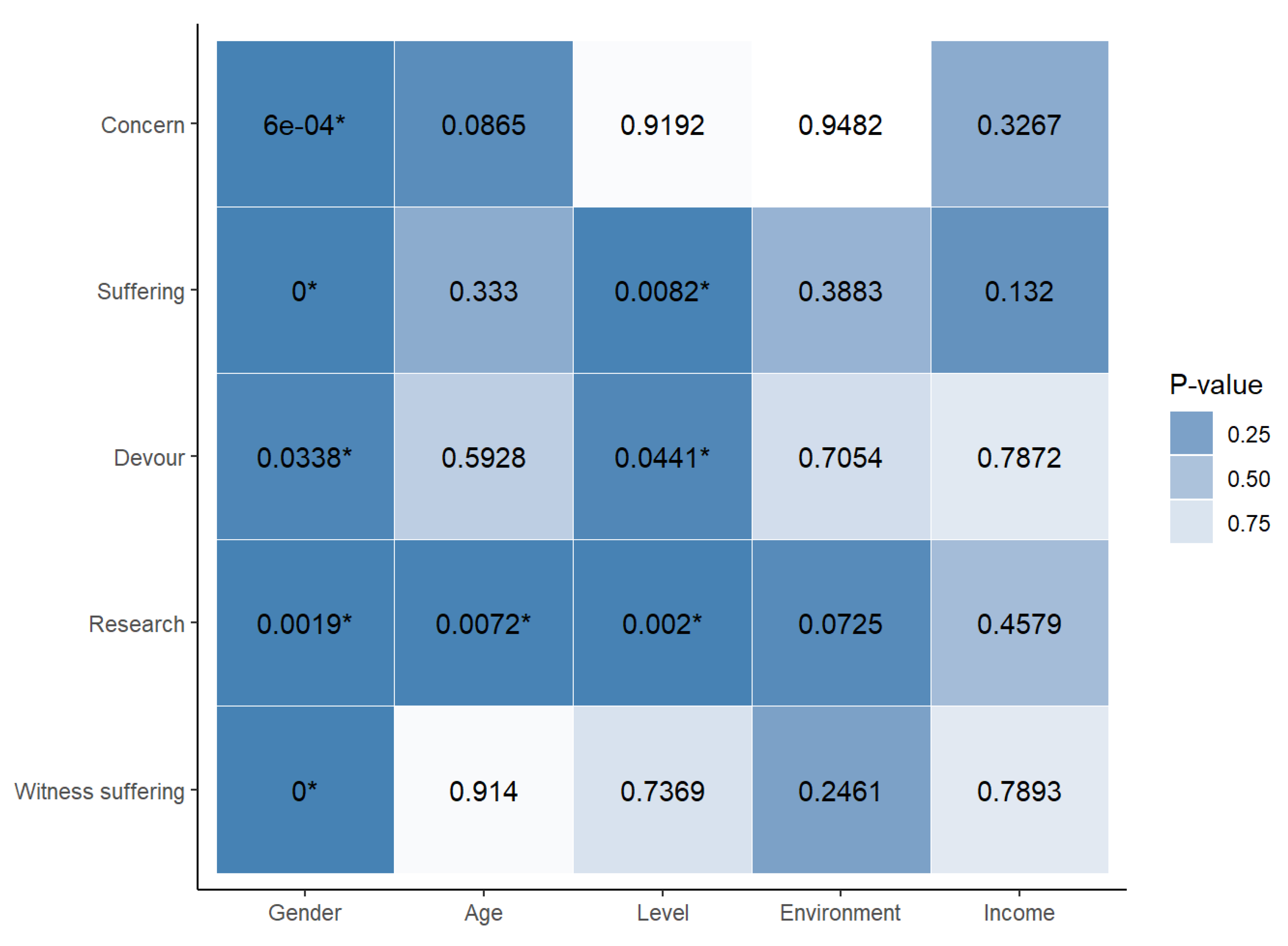

Attitudes toward animal welfare differed based on sociodemographic characteristics and the level of concern. Women, younger participants, and those with more education showed higher levels of concern and held more negative attitudes toward animal abuse and suffering. They were also more likely to pay for animal-origin products with welfare seals (WTP - willing-to-pay) and welfare-friendly products (WFP), indicating awareness of responsibly consuming animal-origin products and a potential market conscious of the value animals provide as protein sources in human diets [

41,

70]. Women held more negative attitudes regarding animal research involving their suffering and expressed greater concerns for animal welfare. Regarding gender, some authors highlight the role of women and their solidarity-driven roles in society [

71], which could explain their more empathetic perceptions about welfare concerns compared to men. Students entering agronomy programs might have increased access to information about production systems through social media, influencing their level of concern for animal treatment. However, this study demonstrates that perceptions of agricultural production systems tend to change more positively as students’ progress through the curriculum. This change could be associated with advanced-level courses on animal production, sensibilizing their perception objectively towards the treatment of animals in different livestock species, as well as caring more for the wellbeing of the species they will continue to interact with in livestock production. Further supporting the role of social media in agricultural education, a notable example is a study where Instagram was used effectively to educate and engage the public about dairy cow nutrition and welfare. This initiative successfully communicated scientific knowledge to a wider audience, creating a community engaged in the welfare of dairy cows. Such innovative approaches in digital outreach highlight the evolving landscape of agricultural education and the growing importance of accessible and interactive platforms for public engagement [

72].

Analyzing perceptions of animal welfare based on sociodemographic variables could be explained through the human-animal bond. An interdisciplinary approach to addressing this bond could generate new knowledge related to the bioethics of animal welfare, where ethical issues about our relationship with animals [

6,

10] interact with knowledge of animal biology [

73], the latter being something that agronomy students learn in the early years of their program. The bioethical principle of autonomy recognizes the telos, i.e., the fundamental biological and psychological essence of any animal based on Aristotle’s principles [

9]. According to this doctrine, the purposes of humans and nonhuman animals do not need coincide, the decision to ethically treat animals is a moral stance specific to humans, therefore, it is not a biological purpose but an ethical decision [

74]. In accordance with the ethics of animal husbandry, nonhuman animals currently serve human rational purposes through breeding and good livestock practices.

Sociodemographic variables such as gender, students’ upbringing environment, and their progress within the curriculum directly influenced ethical and bioethical perceptions regarding the human-animal bond and animal welfare. In this study, most students (85%) came from rural backgrounds compared to 15% from urban areas. This differs from data reported by some authors that underscore a current trend regarding the backgrounds of students studying agronomical sciences who are not from rural environments [

75,

76]. The correlation between sociodemographic variables and the degree of ethical concern for animal welfare might stem from the animal interest movement that gained momentum after the publication of the book ‘Animal Liberation’[

77], marking a turning point in civil society, increasingly concerned about how animals were treated [

78,

79,

80,

81] or treated on farms or livestock production facilities [

23,

82].

The equal consideration of interests introduced by Peter Singer in 1975 (

Animal Liberation) is an interesting qualification of non-human animals. He introduces it as an ethical principle and not as a description of facts. What this does is to prescribe the correct way of understanding and of behavior that we should adapt in connection with other living organisms [

83].

The educational level was linked to greater concern for welfare, with those who had studied longer expressing more affinity and concern for it. Those with more technical knowledge also reported higher concerns, similar to those more familiar, for instance, those who previously lived in rural areas, owned farms, or worked in livestock activities. This explains how prior knowledge of activities can sensitize attitudes and perceptions, along with knowledge transmitted through formal education, to avoid misconceptions about animal production that could potentially affect attitudes.

Some studies have analyzed sociodemographic characteristics and their relation to perceptions and attitudes about animal welfare and haven’t reported significant differences attributable to socioeconomic factors, such as in the present study with family income level [

84,

85]. Student preferences indicate they would pay a differentiated price to improve welfare. Although the effect was significant when analyzing gender, this could provide market niches and should be analyzed in producer associations to assess the costs associated with animal welfare and the benefits of investments made following ethical criteria. Some studies suggest the need for interdisciplinary work because it’s challenging to generate a global concept of welfare that satisfies all involved parties [

86]. The best way to build a just multispecies society may not be known in the present moment, but accepting this responsibility will impact positively to find it out [

87].

Negative perceptions and concerns associated with animal welfare were confined to a zoocentric or anthropocentric view. Perceptions about welfare from an animal perspective are based on animals’ ability to express emotions and feel pain [

10], ergo the observable behavior that would elicit an uncomfortability response in humans. In this regard, the perception that animals may have a value greater than utilitarian value for humans becomes relevant. However, the utilitarian argument for animal welfare lies in the fact that subsequent animal products will be better for the quality and safety of humans consuming them. Conversely, some people's concerns about animal welfare were motivated by their own well-being, seemingly avoiding anthropomorphism. This was reflected in educational levels; in the initial years of the program, there was a negative perception of meat consumption, and as students progressed in their university careers, this perception significantly shifted positively toward meat consumption. Understanding livestock production systems might sensitize this perception change. However, the criterion that animals are treated inadequately or even cruelly remained constant. Some authors have described consuming animal meat as a human right [

88]. The centric view can also offer another form of dissonance, seeing animals as objects rather than sentient beings [

60,

89]. This constitutes a scientific problem and should be addressed as such, without our opinions on animal rights or obligations intervening or interacting. Welfare legislation will consider these scientific issues and will likely affect production systems because consumers are concerned about the welfare of farm animals, leading to social pressure that will affect new legislation. Certain production systems have numbered days, such as foie gras, where force-feeding induces fatty liver in ducks and geese to obtain the "delicacy" product, an act that could be labeled barbaric [

90].

Although most students didn't have negative perceptions of regulated activities like hunting to control species overpopulation, recreational fishing, and pest control, this could be explained by their interaction within agronomy programs involving courses related to agricultural crops, where they engage in supervised practices for biological and/or chemical pest control in crops [

91,

92]. Animals related to fishing and hunting, not being livestock species, might denote a gradient in the value attributed to species closer to humans due to the human-animal bond [

13], for example, mammals, and within these, the establishment of scales for assessing suffering, with primates at the forefront, followed by pets and then livestock animals.

Concerning animal rights, experimentation with them, and ways to protect animal interests, these considerations were not independent of gender, educational level, or students' upbringing environments. Students' assessments regarding bio-rights-related questions suggest a positive stance regarding granting rights to animals, with 70% of respondents indicating that rights should be granted. Granting rights to animals is a complex issue studied in various works [

60,

87,

93,

94,

95]. However, granting rights should go hand in hand with acquiring duties [

96,

97], and the predominant question is, can rights be granted without assuming duties? From a broader perspective, production animals exist under the biopower exerted upon them by the human species, an act defined by Foucault [

98,

99], as the subjugation and disposal of their bodies and population control. Therefore, discussions about animal welfare will be directed toward recognizing this power relationship and seeking to reduce mistreatment linked to domination rather than aiming for a 'liberation' from the breeding and production process for harvesting and generating animal-origin foods. Biopower also functions as a technology of the humanist ideological system to differentiate people from the rest of the animals, as our rationality both dominates and excludes them from the social contract. This implies that animals aren't accountable for their behaviors within the system that surveils and punishes, yet they also don't possess rights or sovereignty over their bodies [

100]. It's incongruous to grant rights to production animals because they exist to be 'utilized' by the human species, and they could never emancipate themselves from this power relationship. Even attempting to grant them rights is another act of domination through rationality and social agreement systems. Instead, it's pertinent of the dominant species, to ensure their welfare from the inherent responsibility and the moral duty to prevent harm and, furthermore, from a zootechnical commitment to responsible animal production that respects animals and ensures productive quality.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.V., J.A.G., E.R.S.R. and F.S.; methodology, J.A.G, F.S. and A.V.; software, A.V.; validation, J.A.G., F.S., and A.V.; formal analysis, A.V.; investigation, J.A.G., F.S., and A.V.; resources, A.V.; data curation, A.V.; writing—original draft preparation, J.A.G. and A.V.; writing—review and editing, S.M., J.A.G., E.R.S.R., C.V., F.S., R.G., and A.V.; visualization, S.M., E.R.S.R., C.V., R.G., and A.V.; supervision, A.V.; project administration, A.V.; funding acquisition, A.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.