Main

Australia identifies as a global leader in marine conservation1. As a commitment to the protection of biodiversity, including marine species, Australia is a Party to all of the major international conservation treaties. The protection and regulation of international trade of Australia’s native species is legislated by the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act of 1999 (henceforth the Act). It is no secret, however, that the state of Australia’s biodiversity is grim, and the Act is ineffective at protecting biodiversity 2,3,4. The Australian Government is reforming its environmental laws to better protect its threatened species, with draft legislation expected to be released for public comment in early 2024. Here, we propose 3 recommendations relevant to the protection of threatened marine species, focusing on those with commercial value in international markets.

Australian commercial fisheries catch species on the Act’s list of 583 (44 are marine species) threatened Australian fauna5. Compliance of commercial fisheries with the Act is the responsibility of the Australian Fisheries Management Authority (henceforth the Fisheries Authority). The trade of species caught in commercial fisheries regulated by the Act (Part 13A) must align with Australia’s obligations to the two main international treaties that coordinate protection and regulate trade of threatened biodiversity: the Convention on Migratory Species (CMS) and the Convention of International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). The interaction of listed species with multiple regulatory and management frameworks was highlighted as a weakness of the Act in an independent review (Samuel Review 4). The concern is that these species, including commercially fished listed species, could be in decline due to inconsistent regulatory and management frameworks. We analyzed seafood trade data to determine the extent that listed species are caught in and exported from Australia to formulate our recommendations for Australia’s threatened species policy reform6.

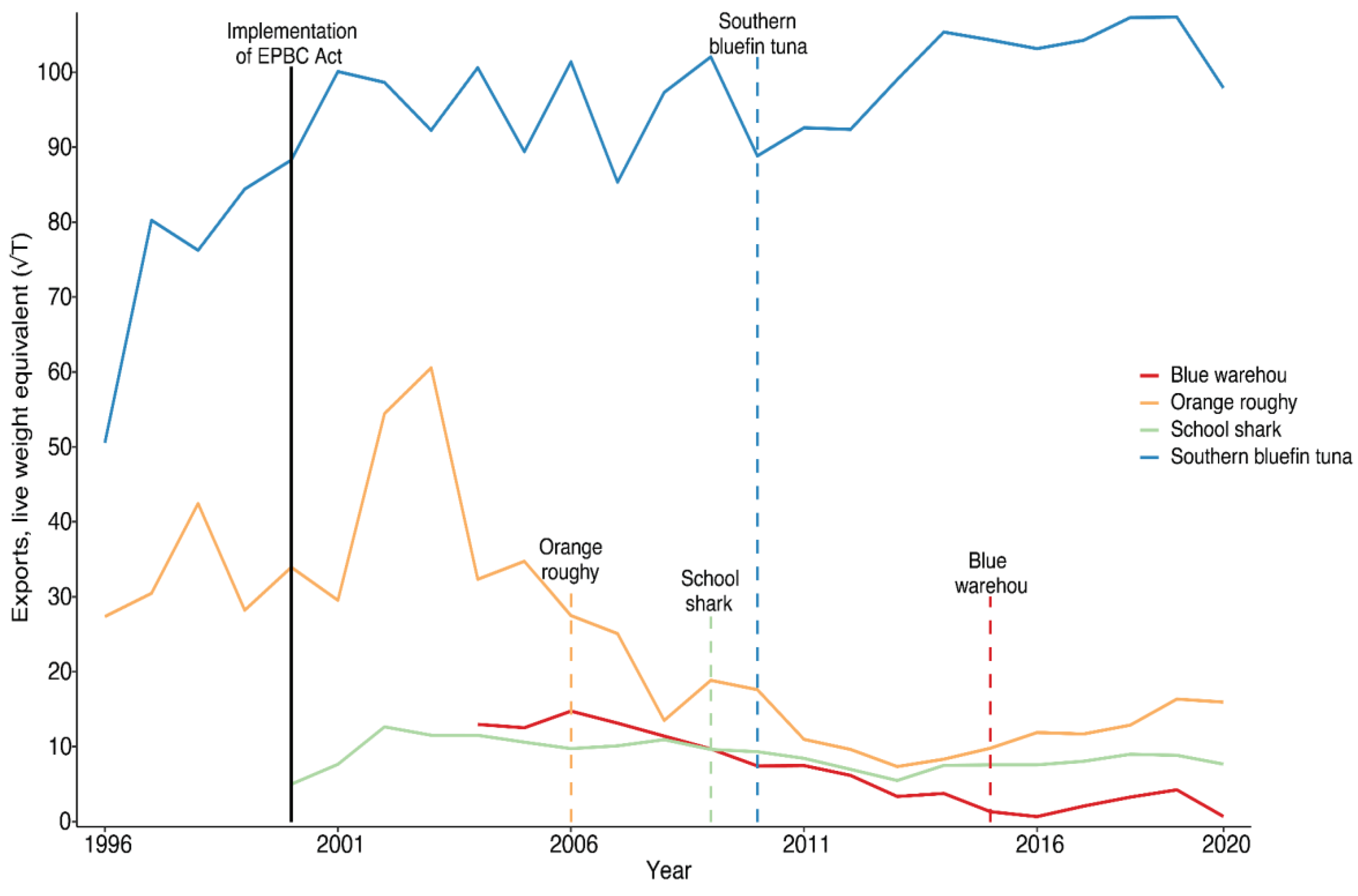

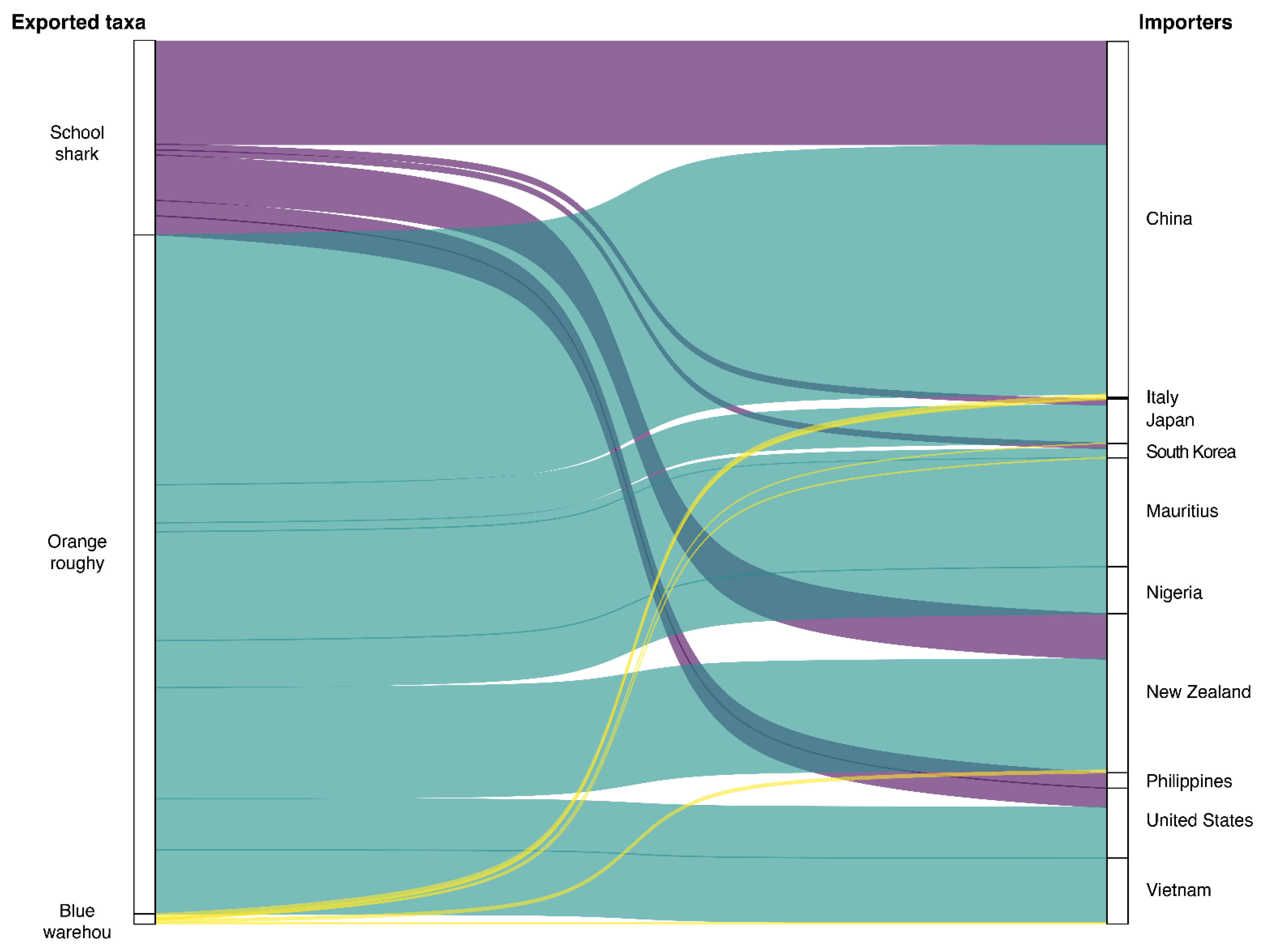

Since the inception of the the Act, 107KT of four listed threatened species were caught in commercial fisheries and identified to be exported as seafood (

Figure 1), primarily to Japan, China, New Zealand, Mauritius, and the USA (

Figure 2): school shark (

Galeorhinus galeus), orange roughy (

Hoplostethus atlanticus), blue warehou (

Seriolella brama), and southern bluefin tuna (

Thunnus maccoyii). These four species are categorized as Conservation Dependent, instead of the more standard denominations: Critically Endangered, Endangered, Threatened, and Vulnerable. This category is unique to Australia and only contains eight marine species caught in commercial fisheries. The Conservation Dependent category is used to exempt commercially harvested species from regulations that would apply if it were listed using the standard categories. For example, all species listed as Conservation Dependent, were assessed as Critically Endangered (blue warehou, southern bluefin tuna) or Endangered (orange roughy, scalloped hammerhead, Harrison’s dogfish, school shark, southern dogfish and gemfish), but were subsequently categorized as Conservation Dependent

7 - 11 (

Sup. Table S1). Interestingly, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature’s (IUCN) Red List of threatened species historically contained a Conservation Dependent category, but it was applied to low risk species, which is a stark contrast to the Act.

When a species is listed as threatened under the Act, conservation advice and, in some cases, a recovery plan, is developed to assist its recovery. However, Conservation Dependent species are not eligible for recovery plans, and currently none have conservation advice (

Sup. Table S1). Instead, the management of these species is the responsibility of the Fisheries Authority, which has been largely ineffective, with the exception of the southern bluefin tuna

4. Several school shark, blue warehou, and orange roughy stocks have not improved, remain overfished, or are unassessed in Australia

12 (

Sup. Table S1). The multiple regulatory and management frameworks used for these Conservation Dependent species are inadequate for ensuring their conservation.

We recommend that Australia’s new legislation treats commercially harvested threatened species the same as other threatened species. Each threatened species must have a species recovery plan that corresponds to its highest eligible threat category. These plans must demonstrate improvements in the species conservation status and be overseen by a single independent environment commission4. Fisheries management decisions must operate within the bounds of this recovery plan. This recommendation may result in omission of the Conservation Dependent category from the new legislation - but only as a means to strengthen, not weaken, the protection of commercially harvested threatened species.

The southern bluefin tuna presents a unique case relative to the other three species, as it accounts for a majority of the Act’s listed species exports (91.2%), is not currently assessed as overfished, includes wild-caught fisheries and ranching, and an intergovernmental organization (Commission for the Conservation of Southern Bluefin Tuna) is responsible for its management, which includes a rebuilding strategy and internationally managed quota. The international management of southern bluefin tuna insulates the species management from domestic politics, potentially contributing to its recovery. The management of this species is internationally contentious, due to its recent history of decline from overfishing. The IUCN Red List classified it as endangered but recovering in 2021, a less threatened category since its previous two assessments in 1996 and 2011 (

Sup. Table S1). Australia’s Threatened Species Scientific Committee has only assessed the species three times: in 2005, 2010, and it is currently under review (

Sup. Table S1). In light of this,

we recommend that Australia’s new threatened species legislation mandate an annual review of the status of all threatened species informed by changes in their population size or other proxies that correspond directly to the new legislation’s listing categories 13. This will ensure that species can be delisted when their population is no longer at risk of extinction, as may happen with southern bluefin tuna.

The Act’s threatened species list has been criticized as incomplete, not representing the range of threatened species in Australia. Thus, we questioned if it has omitted exported species that are globally recognized as threatened. We found that Australia exported an additional 49KT of 13 commercially fished species since their listing under the IUCN Red List, 11 of which are assessed as declining (

Sup. Table S1). We looked at historical listing documents from the Act to determine if other exported species have been proposed for assessment and found two: Patagonian toothfish (

Dissostichus eleginoides) and porbeagle shark (

Lamna nasus). Although the population of the Patagonian toothfish is stable

5, the porbeagle shark’s declining population is globally acknowledged through its listing under the IUCN Red List (globally vulnerable in 1996 with a decreasing population), CMS (Appendix II, 2009), and CITES (Appendix II, 2015). The porbeagle was proposed for assessment under the Act twice (2011, 2012) but not assessed due to data deficiency. Since its listing under CMS and the IUCN Red List, this species has been exported to China, but there have been no further reported exports since its listing under CITES (

Sup. Table S1). Based on reported data, our analysis confirms that Australia adheres to regulations and does not export species listed under both the Act and CITES. However, the export of threatened species is likely to occur as catch data is often reported in broad groups (e.g. ‘sharks and rays’), masking species identity

6, and DNA studies of internationally traded seafood show that threatened species are often sold under other names

14,15. In light of these findings,

we recommend species acknowledged as threatened on global conventions (e.g., IUCN Red List, CMS, and CITES) be assessed in Australia’s new threatened species legislation and, if data deficient, the precautionary principle should apply 16. This recommendation is subject to the caveat that Australia must not be allowed to take out reservations for threatened species if it weakens the protection for that species. CMS and CITES allow parties to take out reservations for species listed, which means the convention’s regulations do not apply to those species in that country. This creates a loophole that could undermine the protection of certain species

17. Currently, Australia has reservations on ten CMS species, all sharks, which is more than any other country.

Australia does not export threatened terrestrial species, only marine species. Since 2000, approximately 10% of the volume of Australia’s exported commercially harvested seafood was listed under the Act, the legislation that was designed to protect threatened species 6. The Act’s Conservation Dependent category, where these species are listed, was not explicitly mentioned in The Samuel Review 4 - threatened species in this category have been overlooked for decades, highlighting the importance of our recommendations. The export of threatened species must cease if Australia is serious about meeting its international conservation and sustainability obligations outlined in the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals and Convention on Biological Diversity. Our three recommendations for Australia’s environmental legislation reform are critical to ensuring the protection of its marine biodiversity. Given the ubiquitous trade of globally threatened marine species for seafood 18, these recommendations may be applicable to other countries' environmental legislation. In addition, countries that import seafood can also adopt regulations that limit the import of threatened species. The USA, for example, is the third biggest importer of Australia’s threatened species but has unique legislation that can ban imports of species that are endangered in its originating country 19. Without adoption of these recommendations, Australia’s marine biodiversity is at risk.