Submitted:

02 April 2024

Posted:

03 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

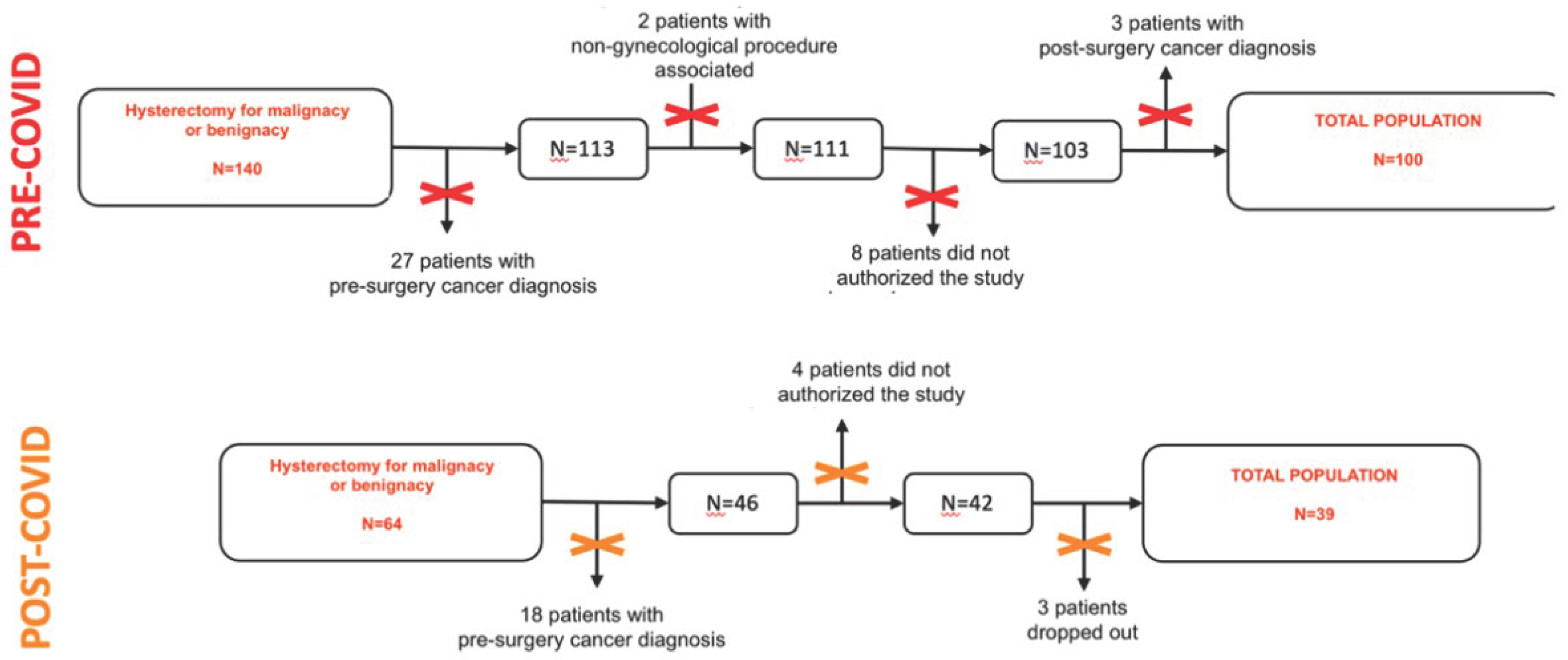

2. Materials and Methods

- T1: pre-surgery consulting by a gynecologist, from one month to one week before the interventions. Here patients have been asked to join the study. Those who accepted, had to fill out a social-demographic questionnaire and the HADS scale;

- T2: first post-surgery day. Patients had to fill out HADS and PCL-5 scales;

- T3: 3 months after surgery. Each patient has been called and the HADS and PCL-5 scales were administrated.

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics

3.2. Psychopathological Characteristics

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- R. El-Gabalawy et al., «Post-traumatic stress in the postoperative period: current status and future directions», Can. J. Anesth. Can. Anesth., vol. 66, fasc. 11, pp. 1385–1395, nov. 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. Casarin et al., «Post-traumatic stress following total hysterectomy for benign disease: an observational prospective study», J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynecol., vol. 43, fasc. 1, pp. 11–17, gen. 2022. [CrossRef]

- C. L. Liu, L. C. L. Liu, L. Liu, Y. Zhang, X. Z. Dai, e H. Wu, «Prevalence and its associated psychological variables of symptoms of depression and anxiety among ovarian cancer patients in China: a cross-sectional study», Health Qual. Life Outcomes, vol. 15, fasc. 1, p. 161, dic. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. Brennan, A. C. Brennan, A. Worrall-Davies, D. McMillan, S. Gilbody, e A. House, «The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale: A diagnostic meta-analysis of case-finding ability», J. Psychosom. Res., vol. 69, fasc. 4, pp. 371–378, ott. 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Hoskins et al., «Pharmacotherapy for post-traumatic stress disorder: Systematic review and meta-analysis», Br. J. Psychiatry, vol. 206, fasc. 2, pp. 93–100, feb. 2015. [CrossRef]

- N. Poloni et al., «Oral Antipsychotic Versus Long-Acting Injections Antipsychotic in Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorder: a Mirror Analysis in a Real-World Clinical Setting», Psychopharmacol. Bull., vol. 49, fasc. 2, pp. 17–27, giu. 2019.

- Weathers, F. W. , Palmieri, P. A, Marx, B. P., Schnurr, P. P, Litz, B., e Keane, T. M., «The PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) – Standard [Measurement instrument].» 2013.

- «SPSS Inc. (released software 2015, IBM SPSS statistics for Mac)».

- C. Callegari et al., «Paroxetine versus Vortioxetine for Depressive Symptoms in Postmenopausal Transition: A Preliminary Study», Psychopharmacol. Bull., vol. 49, fasc. 1, pp. 28–43, feb. 2019.

- W. Li et al., «The Prevalence of Psychological Status During the COVID-19 Epidemic in China: A Systemic Review and Meta-Analysis», Front. Psychol., vol. 12, p. 614964, mag. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Y.-J. Zhao et al., «The prevalence of psychiatric comorbidities during the SARS and COVID-19 epidemics: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies», J. Affect. Disord., vol. 287, pp. 145–157, mag. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Necho, M. M. Necho, M. Tsehay, M. Birkie, G. Biset, e E. Tadesse, «Prevalence of anxiety, depression, and psychological distress among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis», Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry, vol. 67, fasc. 7, pp. 892–906, nov. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Deng et al., «The prevalence of depression, anxiety, and sleep disturbances in COVID-19 patients: a meta-analysis», Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci., vol. 1486, fasc. 1, pp. 90–111, feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. Lakhan, A. R. Lakhan, A. Agrawal, e M. Sharma, «Prevalence of Depression, Anxiety, and Stress during COVID-19 Pandemic», J. Neurosci. Rural Pract., vol. 11, pp. 519–525, set. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Gultekin et al., «Perspectives, fears and expectations of patients with gynaecological cancers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A Pan-European study of the European Network of Gynaecological Cancer Advocacy Groups (ENGAGe)», Cancer Med., vol. 10, fasc. 1, pp. 208–219, gen. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. R. Kibbe, «Surgery and COVID-19», JAMA, vol. 324, fasc. 12, p. 1151, set. 2020. [CrossRef]

- D. W. Franco et al., «Medical adherence in the time of social distancing: a brief report on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on adherence to treatment in patients with diabetes», Arch. Endocrinol. Metab., apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- C. López-Medina et al., «Treatment adherence during the COVID-19 pandemic and the impact of confinement on disease activity and emotional status: A survey in 644 rheumatic patients», Joint Bone Spine, vol. 88, fasc. 2, p. 105085, mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

| Socio-demographic | Pre COVID-19 (N=100) |

Post COVID-19 (N=39) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Age <40 40-50 >50 |

51 (36-77) 4 (4%) 45 (45%) 51 (51%) |

47 (36-71) 4 (10%) 24 (62%) 11 (28%) |

0.10 |

|

Menopause Yes No |

27 (27%) 73 (73%) |

14 (36%) 25 (64%) |

0.44 |

|

Education Primary Secondary High school Degree |

0 (0%) 33 (33%) 50 (50%) 17 (17%) |

2 (5%) 10 (26%) 20 (51%) 7 (18%) |

0.14 |

|

Employment Employee Unemployed Housewife Retiree |

73 (73%) 16 (16%) 9 (9%) 2 (2%) |

29 (74%) 5 (13%) 3 (8%) 2 (5%) |

0.75 |

|

Marital status Married Unmarried Divorced Widowed |

64 (64%) 22(22%) 12 (12%) 2 (2%) |

28 (72%) 7 (18%) 4 (10%) 0 (0%) |

0,72 |

|

Parity 0 1 >1 |

29 (29%) 22 (22%) 49 (49%) |

6 (16%) 13 (33%) 20 (51%) |

0.11 |

|

Living with Alone Family Parents Other |

15 (15%) 77 (77%) 3 (3%) 5 (5%) |

3 (8%) 34 (87%) 1 (2,5%) 1 (2,5%) |

0.59 |

|

Pharmacological therapy No therapy Therapy Antidepressants Anxiolytics/hypnotic Combined |

80 (80%) 20 (20%) 4 (4%) 14 (14%) 2 (2%) |

34 (87%) 5 (13%) 0 (0%) 5 (13%) 0 (0%) |

0.46 |

| Surgery |

Pre COVID-19 (N=100) |

Post COVID-19 (N=39) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Surgical indication Fibromatosis Endometriosis Genital prolapse Abnormal bleeding uterus Endometrial hyperplasia Other |

71 (71%) 10 (10%) 14 (14%) 3 (3%) 2 (2%) 0 (0%) |

28 (72%) 5 (13%) 2 (5%) 1 (2.5%) 1 (2.5%) 2 (5%) |

0.20 |

|

Surgical approach Laparoscopic Laparotomy Others |

90 (90%) 1 (1%) 9 (9%) |

37 (95%) 2 (5%) 0 (0%) |

0.06 |

|

Oophorectomy Yes No |

25 (25%) 75 (75%) |

14 (36%) 25 (64%) |

0.21 |

|

Post-surgery complications Yes No |

10 (10%) 90 (90%) |

7 (18%) 32 (82%) |

0.25 |

| Pre-COVID-19 | Post-COVID-19 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (range) | P-value | Median (range) | P-value | |

|

HADS ANXIETY SCORE T1 T2 T3 |

7 (0-21) 6 (0-18) 4 (0-20) |

0.01 |

6 (0-16) 5 (0-18) 5 (0-12) |

0.02 |

|

HADS DEPRESSION SCORE T1 T2 T3 |

3 (0-14) 3 (0-15) 2 (0-17) |

0.20 |

5 (0-16) 4 (0-16) 4 (0-14) |

0.66 |

|

HADS DEPRESSION SCORE Negative T1 cut-off T1 T2 T3 |

3 (0-7) 3 (0-12) 4 (0-15) |

<0.001 |

4 (0-8) 3 (0-9) 3 (0-8) |

0.56 |

|

HADS DEPRESSION SCORE Positive T1 cut-off T1 T2 T3 |

13 (8-21) 11 (5-18) 7 (0-20) |

0.10 |

10 (8-12) 7 (2-16) 7 (0-14) |

0.02 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).