1. Introduction

Fatigue syndrome (FS) is defined as abnormal exhaustion after engaging in regular activities. The syndrome is associated with both physical and mental health problems. Physical health issues include anemia, autoimmune diseases, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease while mental health issues associated with fatigue include; physical strain, sleep deprivation, antidepressant use. Other health issues associated with this syndrome include; headache, dizziness, dyspnea, and increased number of suicide cases [

1].

Globally, different populations experience fatigue syndrome at different rates. There are usually sub-group in a population where fatigue is more common. In Brazil, the prevalence of fatigue among the adult in the general population was found to be 11.9%, with 8.5% of men and 14.9% of women experiencing it [

2]. On the other hand, the Australian Medical Association discovered that, of 716 doctors, 53% were more likely to experience fatigue while performing their duties [

3]. Moreover, another study noted that about 85% of patients with head and neck cancer reported feeling more tired [

4]. Furthermore, fatigue was a common issue for college students, especially those taking health-related courses [

5].

People today often experience stress due to the level of physical exhaustion, an overwhelming mental workload, depression, and irritability. In addition to the symptom causing enormous tragedies to the families, the unexpected death brought on by chronic fatigue has detrimental effects on social production [

6]. Among the students, there are several factors that contribute to fatigue syndrome, including the amount of work they are engaged in, level of competition, frequent evaluations tests, and peer pressure [

7]. Further, it is noted that the level of fatigue experienced by the students during an ongoing semester session and at the end of semester is based on the level of depression experienced during the semester session which also affects their functioning and health of affected students [

8]. Medical students are not immune to the disorder; in fact, their risk is higher than that of the general student population, which has a significant impact on their quality of life and in health sector at large [

9]. Therefore, it is important to comprehend the prevalence of fatigue and the factors associated with it in order to reduce the possibility of detrimental health effects among the medical students. Although similar or related studies have been carried out in Saudi Arabia, none of the recent studies has focused on all medical student in the general population in Saudi Aribia. Given the existing knowledge gaps, this research sought to assess the prevalence of fatigue syndrome (FS) and its association with depression and anxiety, among the medical students in Saudi Arabia.

2. Materials and Methods

Study Design and Setting

An observational descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted from February to July 2023. Its objectives were to estimate the prevalence of fatigue syndrome (FS) and its association with depression and anxiety, among the medical students in Saudi Arabia.

2.1. Sampling

Using the Raosoft website, with an estimated population of 26,216, a 95% confidence level, a standard deviation of 0.5, and a margin of error of 5%, the required sample size was determined to be 379. Nevertheless, 740 medical students aged above 18 residing in Saudi Arabia participated by completing the online questionnaire.

2.2. Data Collection

An online survey was chosen for its convenience and to maximize student participation. The survey questionnaire was designed on the Google Forms platform and disseminated through email and social media platforms such as WhatsApp, telegram to the selected medical students in various medical colleges nationwide. Ethical clearance was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of Qassim University, Saudi Arabia (Approval No.23-30-07). The participants filled in the survey questionnaire after receiving informed electronic consent. They were assured of confidentiality and given the freedom to opt-out at any stage.

The information consisted in the questionnaire used included:

Socio-demographic Information:

Age, height, weight, Nationality, academic year, marital status, Substance and tobacco use, daily exercise routine, gender.

Chalder Fatigue Questionnaire (CFQ):

It was created by Chalder et al., in 1993, this 11-item questionnaire, validated for the Brazilian primary care setting, measures both psychological and physical fatigue experienced over the past 6 months. Scoring is based on a 4-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 (less than usual) to 3 (much more than usual), the cut-off score for fatigue diagnosis is 22 [

10].

9-item Primary Health Questionnaire (PHQ):

This was translated and validated by

AlHadi et al., it gauges depression symptoms over the last 2 weeks. Its total score spans from 0 to 27, with a diagnostic cut-off of 10 for depression [

11].

GAD-7 Questionnaire:

Also validated and translated by

AlHadi et al., this instrument evaluates anxiety symptoms in the preceding 2 weeks. The scoring threshold for diagnosing anxiety is 10 [

11].

Data Analysis:

Analysis was executed using SPSS version 25.0. Descriptive statistics assessed the prevalence of fatigue syndrome with qualitative results presented as numbers and percentages (N & %) and quantitative results as mean and standard deviation (mean+/-SD). To explore the association between fatigue syndrome (FS) and depression and anxiety, four simple linear regressions and the Chi-square test were utilized. Differences in (FS) across demographic categories were analyzed through an independent sample t-test, Pearson’s correlation, a one-way ANOVA, and Spearman’s rho correlation.

3. Results

As represented in (

Table 1) 740 medical students agreed to participate in this study. The proportion of female students 516 (69.7%) was significantly higher compared to male students 224 (30.3%). Most of the participants were between 18-24 years old 610 (82.4%). The proportion of Saudi students 687 (92.8%) in the study outnumbered the non-Saudis 53 (7.2%), and 160 (21.6%) studied at Qassim University. The fifth-year medical students were 187 (25.5%) and were the highest out of all the academic years, followed by sixth year 139 (18.8%). Moreover, most of the participants 708 (95.7%) were single. In addition, most of the respondents 618 (83.5%) had never smoked before, 719 (97.2%) had never used substance before, 259 (35%) were not doing exercises, 249 (45.9%) exercised by walking and 343 (52.4%) had normal weight.

The data collected revealed that there was a significant difference between women (

M=1.40,

SD=0.63) and men (

M=1.20,

SD=0.60) (P<0.05). (See Supplementary

Figure 1).

However, the results showed a statistically significant relationship between fatigue syndrome and height indicating that shorter students experience greater scores. And there was a statistically significant relationship between fatigue syndrome (FS) and weight indicating obese students reported a higher score than normal weight and obese students. A statistically significant difference between obese and normal weight students (

p=0.041). As well as between obese and overweight students (

p = 0.039). (

Table 1 & supplementary

Figure 2).

Besides, a statistically significant difference was identified between students who use substances and those who have never used substances. Students who used substances experienced a lower score than those who had never used substances before and those who are not using substances but used to. (Supplementary

Figure 3).

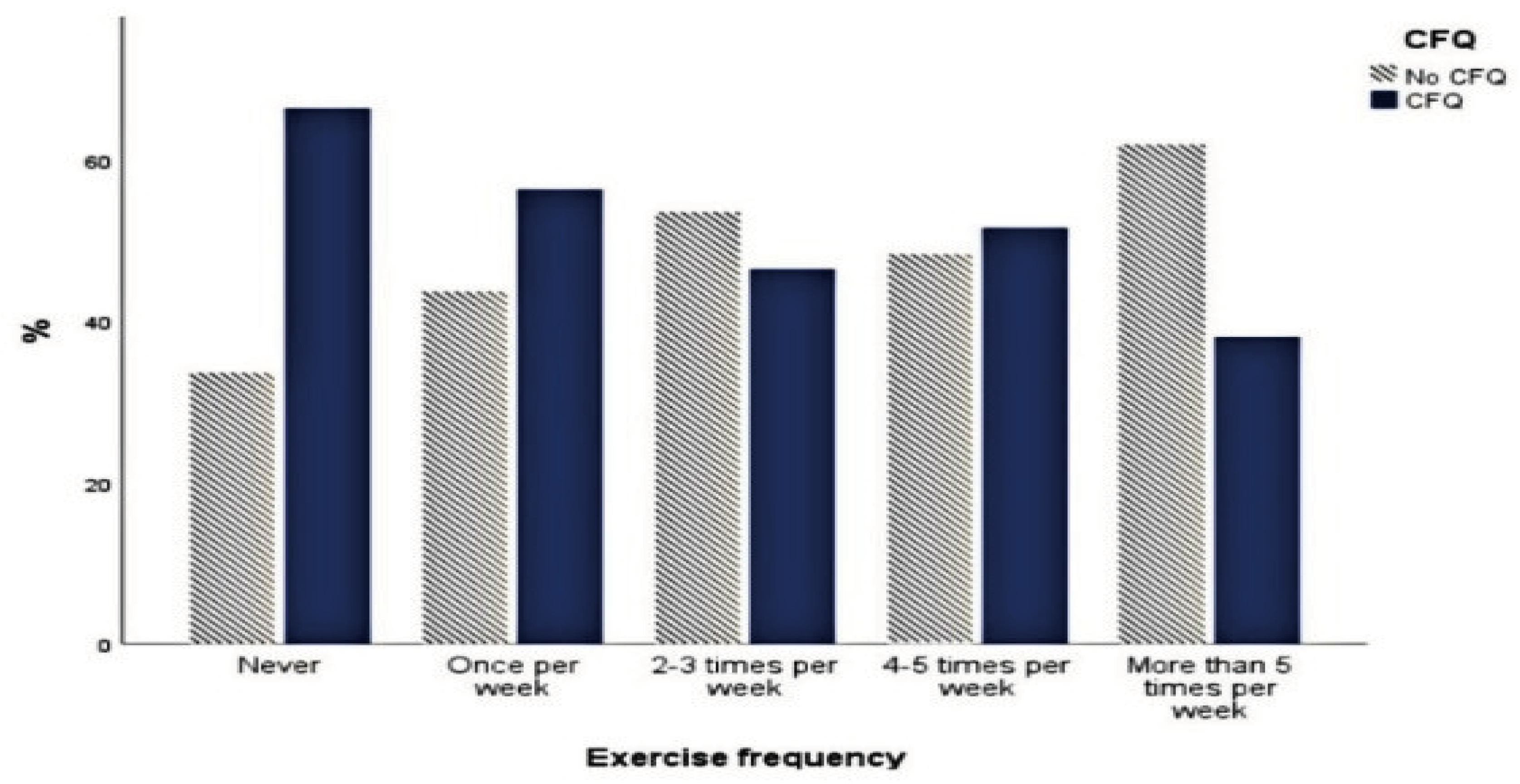

Furthermore, the association between fatigue syndrome (FS) and exercise frequency was evaluated which indicated a statistically significant negative weak relationship (P<0.05). This means that individuals who exercise more frequently experience lower scores. (

Table 2 &

Figure 1).

3.1. Prevalence of Fatigue Syndrome

A descriptive analysis was performed to assess the prevalence of fatigue syndrome (FS) (N = 740). Overall, 56.4% (

n = 417) of the individuals met the fatigue syndrome (FS) diagnostic criteria, while 43.6% were not (

n = 323). Descriptive and frequency analysis on fatigue syndrome (FS) prevalence (see supplementary

Table 1 descriptive analysis; supplementary

Table 2 for frequency analysis).

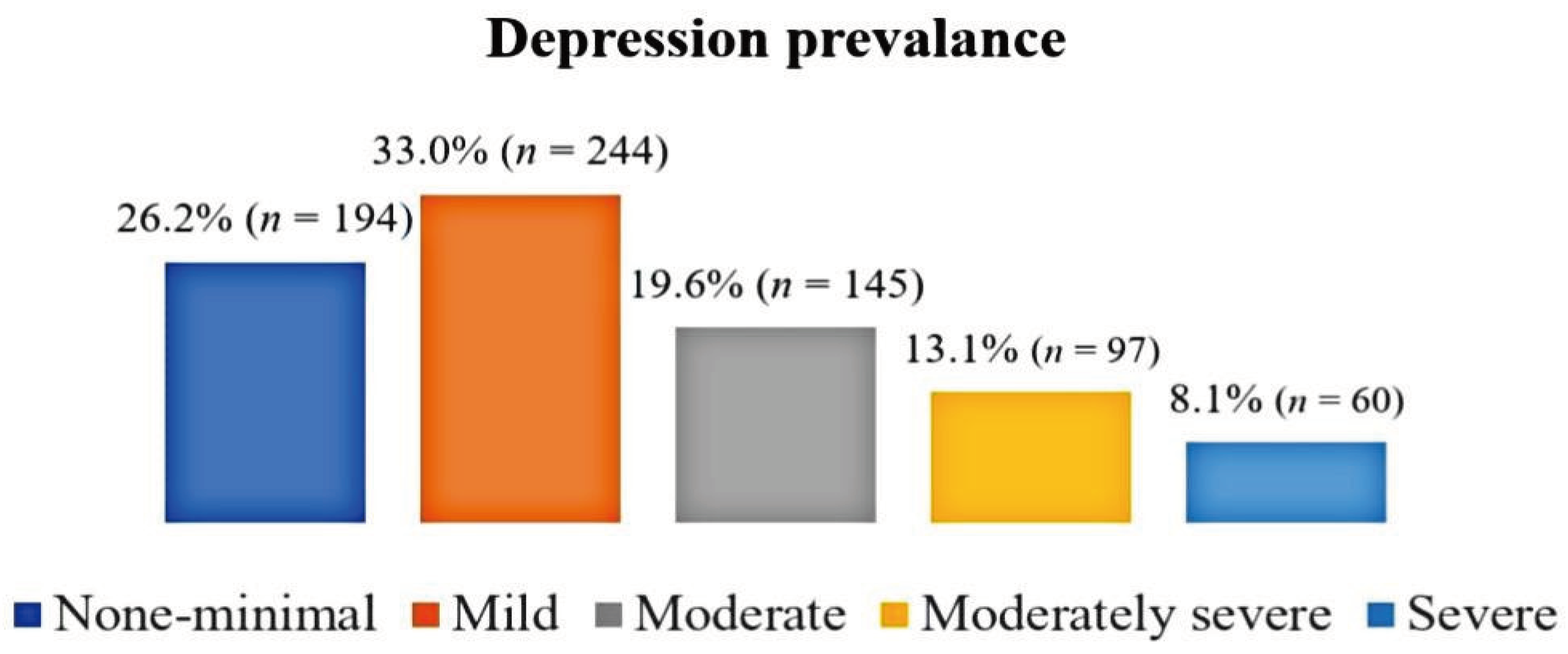

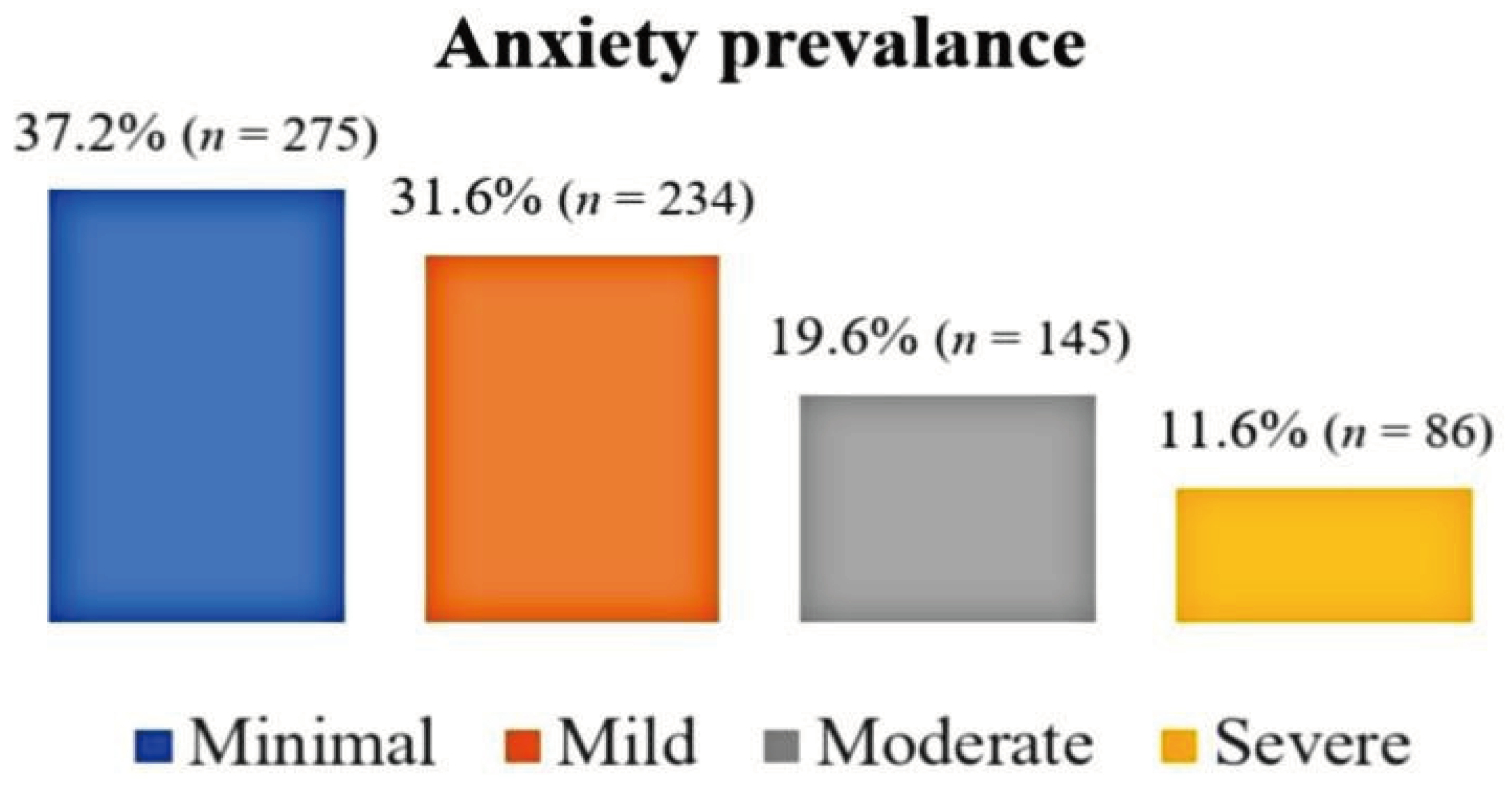

3.2. Depression and Anxiety Prevalence

A frequency analysis was performed to assess the prevalence of depression and anxiety. (See

Figure 2 &

Figure 3 for frequency analysis).

3.3. Hypothesis Testing

3.3.1. H1a to H1b

A simple linear regression analysis was conducted to evaluate if fatigue syndrome (FS) was a statistically significant predictor of depression (N = 740) (H

1a). The analysis showed a statistically significant model,

F (1, 738) = 629.01,

p < .001, which accounted for 45.9% of the variance in depression, (

R2 = .460;

R2adj. = .459). Fatigue syndrome (FS) was a statistically significant positive predictor of depression, indicating that individuals with higher FS scores are more likely to experience greater depression (see

Table 3 for regression coefficients).

Also, a simple linear regression analysis was performed to evaluate if fatigue syndrome (FS) was a statistically significant predictor of the impact of depression on everyday life (N = 740) (H

1b). A statistically significant model was identified,

F (1, 738) = 421.44,

p < .001, which accounted for 36.3% of the variance in the impact of depression on everyday life, (

R2 = .363;

R2adj. = .363). Fatigue syndrome (FS) was a statistically significant positive predictor of the impact of depression on everyday life, suggesting that individuals with higher FS Scores are more likely to experience a greater impact of depression on their everyday life (

see Table 4 for regression coefficients).

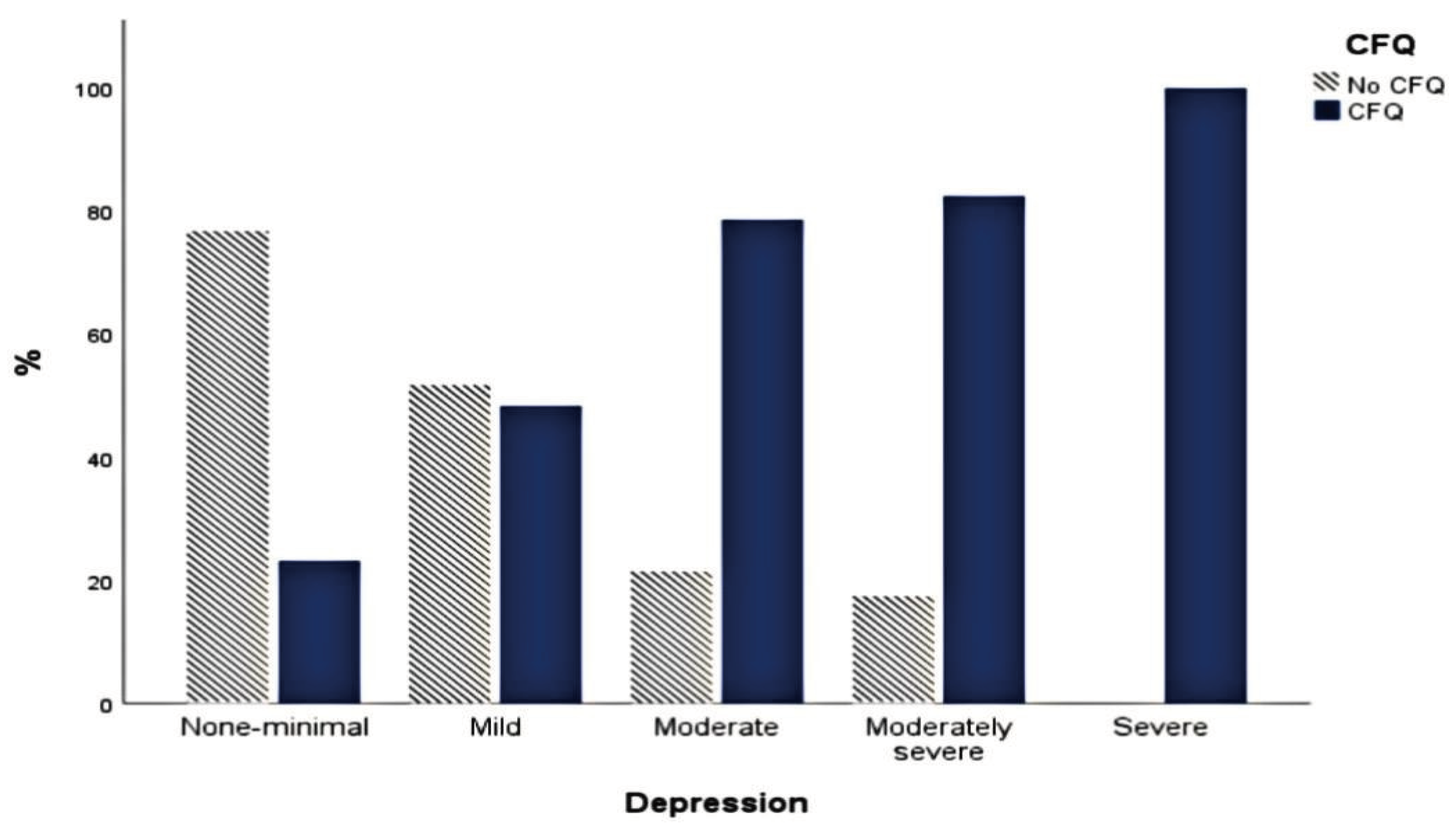

3.3.2. H2

A chi-square test of association was conducted to assess if there was a statistically significant relationship between fatigue syndrome (FS) and depression (N = 740). The analysis indicated a statistically significant relationship, χ

2 (4) = 195.66,

p < .001, Cramer’s

V = 0.51. Relationships between fatigue syndrome (FS) and depression (see

Table 5 &

Figure 4 for contingencies).

3.3.3. H3a to H3b

A simple linear regression analysis was conducted to evaluate if fatigue syndrome (FS) was a statistically significant predictor of anxiety (N = 740) (H

2a). The analysis showed a statistically significant model,

F (1, 738) = 307.92,

p < .001, which accounted for 29.3% of the variance in anxiety, (

R2 = .294;

R2adj. = .293). Fatigue syndrome (FS) was a statistically significant positive predictor of anxiety, indicating that individuals with higher FS score are more likely to experience greater anxiety (see

Table 3 for regression coefficients).

Furthermore, a simple linear regression analysis was performed to evaluate if fatigue syndrome (FS) was a statistically significant predictor of the impact of anxiety on everyday life (N = 740) (H

1b). A statistically significant model was identified,

F (1, 738) = 267.69,

p < .001, which accounted for 26.5% of the variance in the impact of anxiety on everyday life, (

R2 = .266;

R2adj. = .265). Fatigue syndrome (FS) was a statistically significant positive predictor of the impact of anxiety on everyday life, suggesting that individuals with higher FS Score are more likely to experience a greater impact of anxiety in their everyday life (see

Table 4 for regression coefficients).

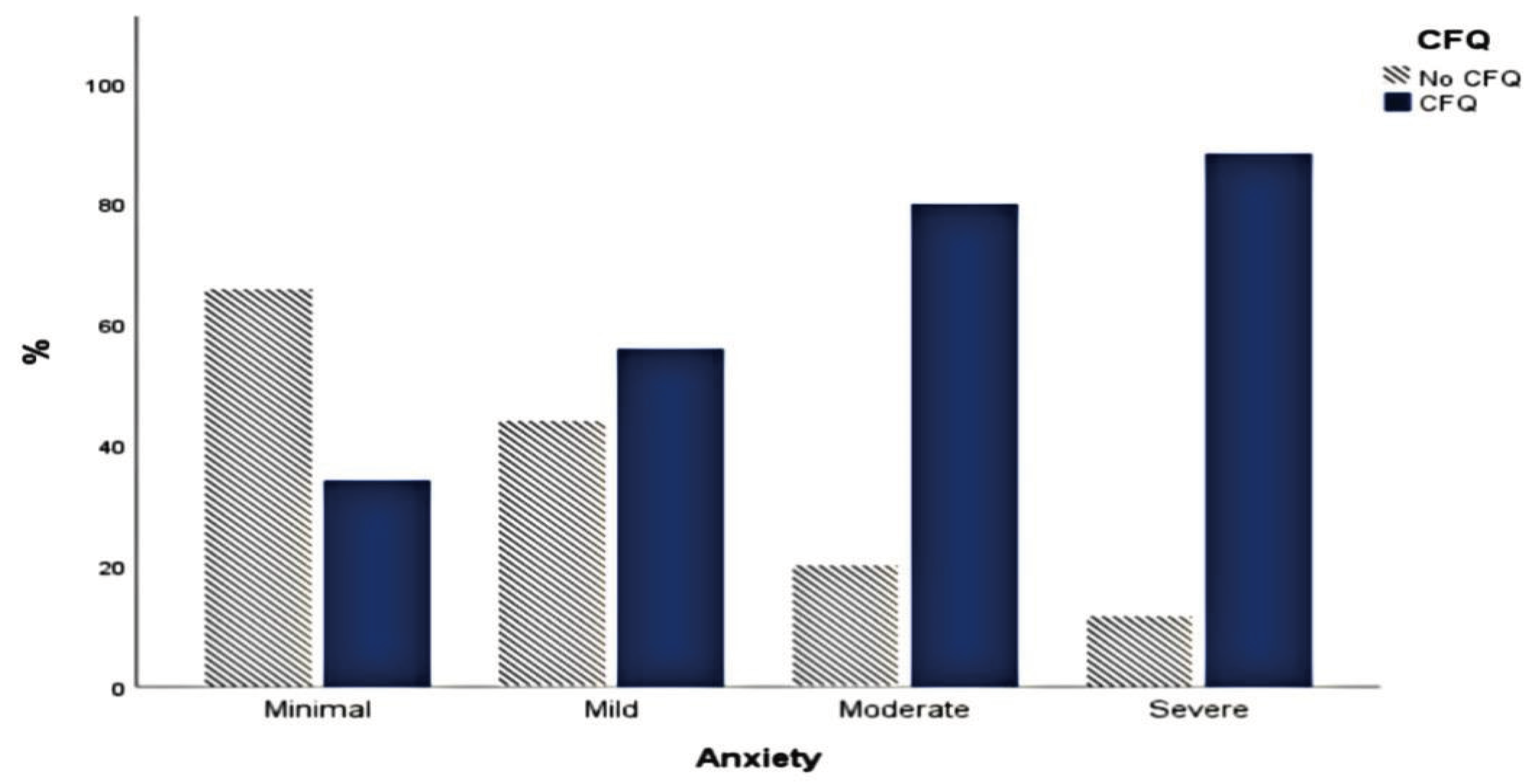

3.3.4. H4

A chi-square test of association was performed to evaluate if there was a statistically significant relationship between fatigue syndrome (FS) and anxiety (N = 740). A statistically significant relationship was identified, χ

2 (3) = 123.78,

p < .001, Cramer’s

V = 0.41. Reaction between fatigue syndrome (FS) and anxiety (see

Table 5 &

Figure 5 for contingencies).

4. Discussion

This study was focused on evaluating the prevalence of fatigue syndrome (FS) and its association with depression and anxiety, among the medical students in Saudi Arabia. The study revealed that among the (N = 740) participants who met the fatigue syndrome (FS) diagnostic criteria. The prevalence of fatigue syndrome (FS) was 56.4% (

n = 417), indicating majority of respondent had fatigue syndrome. The study also found a statistically significant difference between female and male medical students who had FS (P<0.001) with

female students having higher number 516 (69.7%)

compared to male students 224 (30.3%). In addition, the study found a statistically significant relationship between fatigue syndrome and height, weight as well as students with obese (

p < 0.001). This indicates that shorter students’ experienced greater FS scores compare tall students. On the other hand, overweight and obese students reported a higher FS score than normal weight students. The study by

Pokhrel et al., also indicated a statistically significantly between anxiety, depression and presence of FS with the syndrome prevailing more among the female gender [

12].

Besides, a statistically significant difference was identified between students who use substances and those who have never used substances. Students who used substances experienced a lower score than those who had never used substances before and those who are not using substances but used to. Furthermore, the association between fatigue syndrome (FS) and exercise frequency was evaluated which indicated a statistically significant negative weak relationship (P<0.001). This means that individuals who exercise more frequently experience lower FS scores. This findings were also revealed in a study by

Valladares-Garrido et al., where Anxiety (PR: 1.27), depression (PR: 1.35), and stress (PR: 1.31), among other symptoms, were found to be more common in students with eating behavior disorders [

13].

The regression analysis showed a statistically significant relationship between FS and depression,

F (1, 738) = 629.01,

p < .001, which accounted for 45.9% of the variance in depression, (

R2 = .460;

R2adj. = .459). Fatigue syndrome (FS) was a statistically significant positive predictor of depression, indicating that individuals with higher FS scores are more likely to experience greater depression. This findings were in line with results obtained in a study by

Obeid et al., which noted that higher FS scores were linked to individual with psychological difficulties (Beta = 5.547; CI 4.430–6.663) and distress (Beta = 7.455; CI 5.945–8.965) than to individuals who their level of wellbeing is high [

14].

Further, the regression analysis indicated that FS is the predictor of the impact of depression on everyday life. The association was statistically significant

F (1, 738) = 421.44,

p < .001, indicating that FS accounted for 36.3% of the variance in the impact of depression on everyday life, (

R2 = .363;

R2adj. = .363). This suggest that individuals with higher FS Scores are more likely to experience greater impact of depression on their everyday life. In consistence to the finding obtained in a study by Hou et al., the prevalence of FS among the health care workers was reported to be

56.7% with a number healthcare workers with FS being noted to have higher level of depression and anxiety oftenly [

15]

. The Chi-square test also indicated a statistically significant relationship between fatigue syndrome (FS) and depression, χ

2 (4) = 195.66,

p < .001, Cramer’s

V = 0.51. In a study by Luo et al., the results from univariate analysis indicated that the level of fatigue syndrome among the university students surveyed was based on the sleep quality, anxiety, depression, study habits, alcohol use, exercise, and overnight stays. This association was found to statistically significant (P < 0.001) [

16].

The regression analysis further showed a statistically significant relationship between Fatigue syndrome (FS) and individual with anxiety,

F (1, 738) = 307.92,

p < .001, indicating that FS accounted for 29.3% of the variance in anxiety, (

R2 = .294;

R2adj. = .293). This suggest that individuals with higher FS score are more likely to experience greater anxiety.

Al Houri et al., also indicated in their study that among the undergraduate medical students surveyed, most of the anxiety reported was connected to their studies. Among participants, most of them had moderate stress levels (37.0%; n = 545) and mild stress levels (50.6%; n = 745) [

17].

Furthermore, the linear regression analysis showed that fatigue syndrome (FS) is the predictor of the impact of anxiety on everyday life. The association was statistically significant,

F (1, 738) = 267.69,

p < .001, indicating that FS accounted for 26.5% of the variance in the impact of anxiety on everyday life, (

R2 = .266;

R2adj. = .265). This suggest that individuals with higher FS Score are more likely to experience a greater impact of anxiety in their everyday life. The study by

Sacramento et al., indicated that among the FS group, anxiety symptoms were present in 30.8% of cases, while depression symptoms were present in 36.0%. There was a statistically significant correlation between gender, age, and sexual orientation and the crude and adjusted PR for anxiety symptoms. Gender, ethnicity/skin color, and sexual orientation were statistically significantly correlated with the crude and adjusted PR for depressive symptoms [

18]. The Chi-square test of the association between fatigue syndrome (FS) and anxiety also showed a statistically significant relationship, χ

2 (3) = 123.78,

p < .001, Cramer’s

V = 0.41. Based on another study conducted among

health sciences undergraduate students, a number of stress cases (74.6%) and depression cases (66.2%) were normal-to-mild levels. On the other hand, 74.6% of them had moderate-to-extremely severe anxiety. The correlation between the year of study and the stress score were statistically significant. Based on their findings, low-grade fever and recurrent headaches were risk factors for stress and anxiety, while exhaustion and poor sleep quality were risk factors for anxiety and depression [

19].

The study had some limitations, therefore, care should be taken when interpreting the results. The temporal relationship between the exposures and outcomes could not be established due to the use of a cross-sectional research design. So, longitudinal studies should be taken into consideration by future researchers. The results could have been impacted by social desirability and memory recall biases resulting from the self-reporting mechanism in the questionnaire. This may be enhanced in subsequent research by adding comprehensive diagnostic questionnaires to the evaluation. Furthermore, a general study of Saudi medical students was conducted. Scoping the future research based on the medical program and its departments would give special characteristics that shape students’ viewpoints. So, a single-centered study that assesses the degree of fatigue syndrome according to the medical curriculum would help in understanding the level of FS among medical students in Saudi better.