1. Introduction

In the context of economic globalization, higher vocational education has gradually become a key force in promoting economic growth and technological innovation. As one of the world’s largest manufacturing powerhouses, higher vocational education of China is particularly prominent in terms of scale and influence. There are currently 1580 higher vocational colleges in China, covering a total of 16,937,700 students [

1]. Similar to undergraduate students, academic adjustment is a major challenge for higher vocational college students after entering college [

2].They must adapt to new academic environments and navigate the transition into early adulthood roles [

3,

4,

5].

Academic adjustment refers to the process in which students strive to adjust themselves to maintain a balance between psychological and behavioral activities with the academic

environment based on their environment and academic

demands.This process involves students’ motivation and attitudes towards learning, the learning strategies they employ, as well as their level of learning engagement [

6,

7]

. Students who are well-adjusted are more likely to achieve academic success, whereas students who are maladjusted are prone to experiencing a variety of challenges including decreased academic performance, mental health issues, and difficulties with social adjustment 8]. Comparing to the general undergraduate students, higher vocational college

students faced more complex challenges, because they might have problems like weaker learning foundation, poorer learning habits, and lack of learning motivation [

9,

10]

, which influence their academic performance, personal development and career planning. However, higher vocational education and its students fail to receive sufficient social and academic attention compared to other forms of higher education [

11]

.The difficulties faced by higher vocational college

students in academic adjustment have not been thoroughly investigated and comprehended, along with the factors and mechanisms that contribute to these challenges.

The academic adjustment of higher vocational college students is a complex process, involving factors such as perceived academic progress, interactions with peers and faculty, and satisfaction with the learning environment [

12]. It is influenced by a combination of individual characteristics and environmental factors [

13], specifically by perceived peer support, academic hope, and professional identity. Conservation of Resources (COR) theory and Social Support Resource (SSR) theory provide valuable frameworks for understanding this process, emphasizing the significance of individual resource management and social support to mitigate the negative impact of stressful situations [

14,

15,

16]. This study aims to examine how perceived peer support affects the academic adjustment of higher vocational college students, and how academic hope and professional identity contribute to this adjustment process. Additionally, it seeks to explore potential differences among students from diverse educational backgrounds.

1.1. The Influence of Perceived Peer Support on Academic Adjustment

SSR theory suggests that perceived peer support significantly contributes to individual adjustment and health, offering emotional, informational, material, and evaluative support [

16]. In adolescent school life, perceived peer support significantly influences daily behaviors, including preferences and classroom performance in school life and commitment to after-school assignments.

It is evident that perceived peer interaction and support could motivate students and enhance their academic performance [

17,

18]. Additionally, perceived peer support is a crucial source of assistance for students transitioning from high school to college, especially for those in unfamiliar surroundings and facing challenges in forming social connections [

19]. Students who receive perceived peer support tend to have higher academic self-efficacy and greater motivation to learn [

20]. A recent study found a positive correlation between perceived peer support and college students’ academic resilience, strengthening over time [

21].

The above clearly demonstrates the significant role of perceived peer support in enhancing college students’ academic adjustment. Considering the unique challenges faced by higher

vocational college students, perceived peer support is more important in their academic adjustment. This was confirmed by research involving 239 students from 12 higher education institutions in California.The study found that perceived peer interactions, such as information and experience sharing, could help students understand and adapt to their majors, thereby enhancing their learning and vocational skill development [

22]. Based on these findings, we propose that perceived peer support is essential for promoting academic adjustment among higher vocational colleges students of China.

1.2. The Mediating Effect of Academic Hope

In the area of psychology, hope is widely recognized as a key dynamic and cognitive process for individuals to achieve their goals. It is an ability to identify and mobilize oneself towards a desired goal, as defined by Snyder and colleagues [

23]. This view not only underscores the goal-oriented nature of hope but also underscores its motivational and cognitive dimensions. Research has demonstrated a strong correlation between social support and levels of hope [

24]. Especially, social support has been identified as a key factor in predicting hope among children left behind, underscoring its crucial role in nurturing and boosting hope [

25]. COR theory suggests that social support can foster the construction of positive psychological resources [

14,

26].

Research in the area of positive psychology has highlighted the importance of psychological capital, specifically hope, in predicting college students’ academic adjustment [

27]. A recent study demonstrated a significant correlation between academic hope and academic adjustment among freshman, with academic hope emerging as a key positive predictor [

3]. Students’ academic performance and overall level of adjustment can be significantly enhanced by nurturing academic hope [

28]. These findings emphasize the importance of exploring and clarifying academic hope for academic adjustment in educational psychology research and practice. Academic hope which relates to individual’s optimistic outlook for the future directly influences their motivation, persistence, and approach to learning. Sympson (1999) defined academic hope as an individual’s specific hope within the academic sphere [

29]. Subsequent studies have consistently demonstrated that academic hope is a stronger predictor of educational outcomes than general hope [

30,

31]. However, these studies have not yet been validated for higher vocational colleges students of China, leaving room for exploration of the influence of academic hope on this specific group. Based on previous research and analyses, it can be inferred that perceived peer support, an important source of social support, could enhance the academic hope of higher vocational college students.

A recent study discovered that social support, especially perceived peer support, indirectly boosted academic adjustment in vocational high school students by augmenting psychological capital. Hope, identified as a central component of psychological capital, was shown to significantly promote academic adjustment, more so than other components like optimism, resilience, and self- efficacy [

32]. This finding suggests that academic hope might mediate the relationship between perceived peer support and academic adjustment among higher vocational college students. These initial results offer fresh insights into the relationship between perceived peer support, academic hope, and academic adjustment in higher vocational college students. COR theory could be used to explain how academic hope mediates the relationship between perceived peer support and academic adjustment. According to this theory, accessed resources not only aid individuals in coping with pressure but also encourage the further accumulation of resources, thereby creating a positive cycle [

14]. Within this framework, academic hope may serve as a mediating variable between perceived peer support and the academic adjustment of higher vocational college students.

1.3. The Mediating Effect of Professional Identity

Professional identity, a crucial aspect of self-identity, reflects students’ understanding, acceptance, and acknowledgment of their major. This process involves both their understanding of professional knowledge and dynamic psychological experiences of the learning process [

33]. Social support, including perceived peer support, is significantly predicting college students’ professional identity [

34]. A recent qualitative research further confirms the importance of support from key individuals in influencing doctoral students’ professional identity levels [

35]. Under the background of higher vocational education, peer groups play a crucial role in shaping students’ social identities and their support can greatly enhance the sense of identification with professional communities. Professional identity could positively predict academic adjustment of college students [

36,

37].

A comprehensive review of existing studies has revealed a significant connection between social support, professional identity, and academic adjustment. Recent research indicates that professional identity acts as a mediator in the relationship between social support and academic adjustment for vocational high school students [

32]. Given that perceived peer support is a critical dimension of social support, it is plausible to consider that professional identity may also act as a mediator between perceived peer support and students’ academic adjustment in higher vocational colleges.

1.4. The Chain-Mediating Effect of Academic Hope and Professional Identity

The limited studies provide a foundation for the significance of academic hope in professional identity and its influence on academic adjustment. Research has shown that hope plays a crucial role in shaping adolescents’ professional identities, particularly in assisting urban adolescents in over- coming obstacles to career development and shaping their future career aspirations [

38]. Subsequent studies have further validated the significant positive impact of psychological capital, specifically hope, on professional identity [

39,

40]. These findings underscore the positive relationship between academic hope and professional identity, as well as the beneficial role of hope in fostering

professional identity and career advancement. Moreover, Wang’s study offers a deeper understanding of how social support initially enhances the psychological capital of vocational high school students, leading to improved professional identity and academic adjustment. In this process, hope, a critical component of psychological capital, not only received a significant positive boost from social support but also contributed to the enhancement of professional identity and academic adjustment [

32]. Consequently, Therefore, perceived peer support may affect academic adjustment of higher vocational college students through the chain-mediating effect of academic hope and professional identity.

1.5. The Moderating Role of Educational Background

The student body in higher vocational colleges has become increasingly diverse with the expansion of higher vocational education, encompassing both traditional general high school graduates and vocational high school graduates. According to COR theory, individuals actively seek

to maintain, protect, and accumulate resources in their favor, among which environmental factors and individual differences play a crucial role in the process of resource access and conservation [

14]. This theoretical perspective highlights the significant differences in educational environments and resource access between students from general and vocational high schools. General high schools prioritize cultural literacy and comprehensive academic development, offering abundant learning resources and opportunities to foster students’ academic and personal growth. In contrast, vocational high schools emphasize technical and vocational training, with less focus on critical thinking, creativity, and advanced academic knowledge [

41]. However, vocational high school students often encounter limitations in financial, facilities, and faculty [

42], which restricts their access to resources essential for their academic development. Therefore, COR theory suggests that significant differences in resource access and utilization, stemming from varying educational backgrounds, may moderate the influence of perceived peer support on the academic hope of higher vocational college students.

1.6. The Current Study

Existing studies have extensively explored key factors influencing academic adjustment, such as perceived peer support, academic hope, and professional identity. However, these studies primarily concentrated on general undergraduate and vocational high school students, and existing research lacks a systematic explanation within a robust theoretical framework on the impact of these factors.

Furthermore, current studies do not comprehensively analyze the chain effect of academic hope and professional identity among perceived peer support and academic adjustment of higher vocational college students. Additionally, some studies suggest that educational backgrounds, such as whether they come from vocational or general high schools, may influence academic adjustment. Few studies have explore how this background influences the specific mechanisms of academic adjustment, particularly in relation to perceived peer support and academic hope.

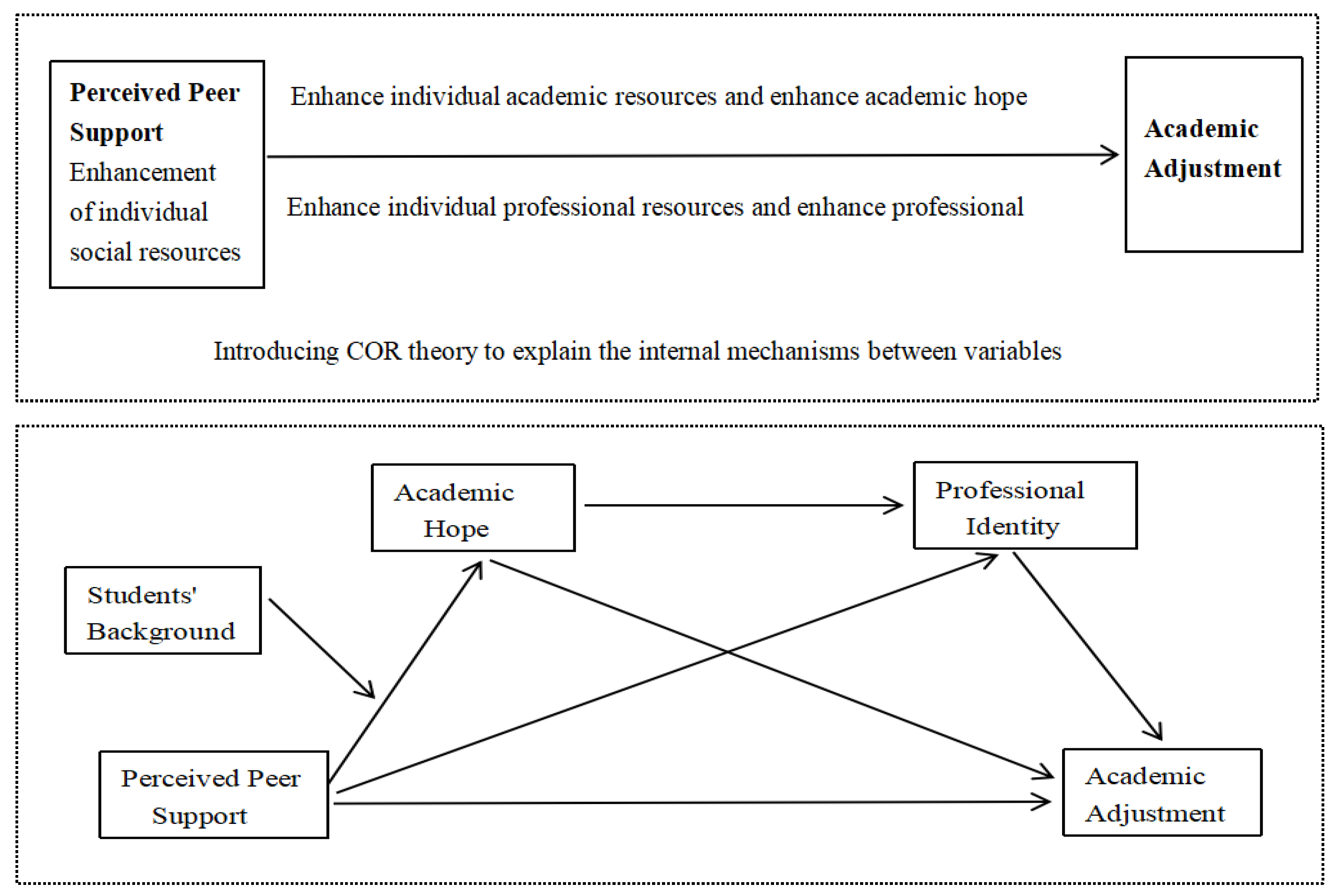

The aim of this study is to employ COR theory as the foundational research framework, integrating SSR theory to offer novel insights and conduct a comprehensive analysis of academic adjustment among higher vocational college students. Firstly, this study aims to construct a chain mediation model that combines perceived peer support, academic hope, and professional identity to provide a comprehensive framework for understanding how these factors influence the academic adjustment of higher vocational college students. Secondly, this study aims to investigate the moderating role of educational background on the relationship between perceived peer support and academic hope.This study will test the following five research hypotheses (

Figure 1):

Hypothesis 1: Perceived peer support is predicted to positively influence academic adjustment among higher vocational college students.

Hypothesis 2: Academic hope acts as a mediator in the relationship between perceived peer support and academic adjustment among higher vocational college students.

Hypothesis 3: Professional identity serves as a mediator between perceived peer support and academic adjustment among higher vocational college students.

Hypothesis 4: Academic hope and professional identity play a chain-mediating role between perceived peer support and academic adjustment of higher vocational college students .

Hypothesis 5: The educational background of students moderates relationship between perceived peer support and academic hope among higher vocational college students. Specifically, students from vocational high schools are hypothesized to exhibit a more significant effect of perceived peer support on academic hope compared to their counterparts from general high schools.

The theory of COR is taken as the theoretical basis of the whole research framework.

Figure 1.

Theoretical research model of the study.

Figure 1.

Theoretical research model of the study.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Participants were recruited from 35 higher vocational colleges across 13 provinces and cities in China for this study, including Shandong, Anhui, Fujian, Guangxi, Hubei, Jiangsu, Inner Mongolia, Sichuan, Shanxi, Henan, Zhejiang, Shanghai, and Shenzhen. This study adopted a random sampling method, and a total of 9782 (M = 19.50 years,SD = 1.45, range 17 to 22) valid questionnaires were obtained. Among the participants, there were 4892 (50.01%) male and 4890 (49.99%) female students; 6091 (61.53%) freshmen, 3232 (33.04%) sophomores, and 531 (5.43%) juniors; 6038 (61.72%) graduated from general high schools, while 3743 (38.28%) graduated from vocational high schools.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Self-Compiled Academic Adjustment Scale for Higher Vocational College Students

In this study, a self-compiled Academic Adjustment Scale was developed specifically for higher vocational college students. Initially, the structure and dimensions of academic adjustment among higher vocational college students were explored through the existing scales and semi-structured interviews with 42 students from a higher vocational college in Shandong Province of China. After extensive discussions with three psychology professors and three doctoral students, an initial 61-item scale was created. Subsequently, a questionnaire survey was conducted with 1045 first- to third-year students from 10 higher vocational colleges in China, resulting in 917 valid responses. Through item analysis and exploratory factor analysis, a 19-item academic adjustment scale for higher vocational college students encompassing dimensions of learning engagement, learning strategies, and learning motivation was established. The factor load between 0.50 to 0.82 per item, explaining 59.47% of the total variance. Further validation was carried out in 11 higher education institutions, gathering 881 valid responses from 1023 students. The scale demonstrated strong internal consistency (Cronbach’s α coefficient of 0.94), good model fit, and significant correlation with Academic Adjustment Scale for College Students (

r = 0.72,

p < 0.05) [

43], indicating robust validity.

Finally, the questionnaire was administered to 9782 participants across 35 higher vocational colleges in 13 provinces and cities in China.The self-administered Academic Adjustment Scale for Vocational College Students, with a Cronbach’s α coefficient of 0.91, was utilized for this purpose. The results of the validated factor analyses showed x²/ df = 62.52, RMSEA = 0.08, SRMR = 0.05, NFI = 0.91, CFI = 0.91, and GFI = 0.93. Despite the x²/df ratio exceeding the ideal value, likely due to the large sample size, all other fit indices satisfied the standard criteria, indicating a good fit for the scale.

2.2.2. Perceived Peer Support Scale

The perceived peer support scale used in this study is based on 9 items specific to peer support in the multidimensional social support scale developed by Zhanget al. [

44]. The original scale, consisting of 27 items, encompassed emotional, instrumental, and informational support dimensions, as well as parental, peer, and teacher support dimensions. Use the 5-point Likert scale for scoring(1= strongly disagree, 5= strongly agree). The Cronbach’s α coefficients for the original scale ranged from 0.89 to 0.95, with an overall reliability of 0.96 and strong validity indicators. In this study, the selected Perceived Peer Support Scale demonstrated a Cronbach’s α coefficient of 0.94. Factor analysis results from a sample of 9782 participants revealed

x²/df = 59.36, RMSEA = 0.08, SRMR = 0.05, NFI = 0.91, CFI = 0.91, and GFI = 0.91. Despite slightly elevated x²/d

f values attributed to the large sample size, all other fit indices surpassed the desired thresholds, indicating strong construct validity of the scale.

2.2.3. Academic Hope Scale

The Academic Hope Scale utilized in this research is adapted from the Domain Specific Hope Scale-Revised , specifically developed to evaluate pathways thinking and motivated thinking within an academic context [

45]. The scale comprises three 'pathways' items (e.g., “I can come up with multiple methods to achieve good grades”) and three 'agency' items (e.g., “I feel motivated to achieve good grades in school”). Previous studies have demonstrated the scale's robust reliability and validity, with an internal consistency coefficient exceeding 0.89. Ratings on the scale employ a five-point likert format (1= strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree), where higher scores denote greater academic hope.The scale demonstrated high internal consistency, evidenced by Cronbach’s α coefficients of 0.93 for the overall scale, 0.87 for the ‘pathways’ dimension, and 0.89 for the ‘agency’ dimension. Factor analysis results (

N = 9782) indicated good fit indices, with

x²/df = 55.25, RMSEA = 0.08, SRMR = 0.01, NFI = 0.99, CFI = 0.99, and GFI = 0.98, suggesting excellent structural validity despite some limitations in x²/

df values due to the large sample size.

2.2.4. Professional Identity Scale

The Professional Identity Scale for College Students, developed by Qin Panbo (2009), consists of four dimensions: cognitive identity, affective identity, behavioral identity, and aptitude identity, totaling 23 question items [

33]. The scale utilizes a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (completely), where higher scores indicate stronger professional identity. The original scale showed good reliability and validity. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the entire scale was 0.96, with coefficients for the four dimensions ranging from 0.79 to 0.89, indicating high internal consistency and ensuring measurement reliability. Factor analysis results for the sample size of 9,782 participants showed

x²/df = 25.27, RMSEA = 0.06, SRMR = 0.03, NF I= 0.96, CFI = 0.968, and GFI = 0.94. While x²/

df did not meet the standard due to the large sample size, other fit indexes indicated good construct validity of the scale.

2.2.5. Self-assessment of Academic Grades

Participants in this study were asked to evaluate their academic performance in class by reviewing their recent test scores, following the methodology used by Lu et al. [

46]. The assessment criteria included three levels: lower-middle, Middle and upper-middle.

2.3. Procedure

Data collection for this study took place from late October to late December 2023. Paper questionnaires were distributed in classrooms by cooperating faculty members. Participants were assured that their responses would remain confidential and used solely for academic research. Emphasis was placed on the voluntary nature of participation to protect participant rights and uphold ethical standards.

2.4. Data Analyses

Prior to commencing data analysis, we implemented several critical steps to ensure the high quality of the collected data. First, a thorough review of the three polygraph questions in the questionnaire was conducted. These questions are designed specifically to determine whether participants responded earnestly to certain aspects of the questionnaire. Any inconsistencies in responses led to the exclusion of the respective questionnaire data from the final database. Subsequently, a completeness check was carried out, with questionnaires not fully answered being excluded to ensure comprehensive responses. Following these data cleaning procedures, the valid questionnaire data was manually input into an electronic database to prevent missing data. Utilizing the well-prepared database, basic statistical analyses, including descriptive statistics, correlation analysis, and ANOVA, were performed using SPSS 24.0 software. To delve deeper into intricate data relationships, such as mediating and moderating effects, the PROCESS macro plug-ins in SPSS 24.0, specifically plugins 6 and 83, were employed. Furthermore, Amos 26.0 software was used to validate the accuracy of date. This meticulous process ensured the rigor and robustness of our data analysis, ultimately yielding reliable findings.

3. Results

3.1. Common Method Variance Test

To ensure the scientific validity of the study results and minimize any potential distortion of correlations between variables, various measures were implemented to address common method bias. Participant response bias was mitigated by collecting questionnaires anonymously [

47]. The analysis, based on Harman’ s single-factor test, identified seven factors with eigenvalues greater than 1. The first principal factor explained 38.11% of the total variance, below the critical 40% threshold, indicating no significant common method bias. One-way validated factor analysis (

N = 9782) showed

x²/df = 133.49, RMSEA = 0.12, SRMR = 0.09, NFI = 0.52, CFI = 0.66, and GFI = 0.52. Although these results indicate that the model’s fit to the data did not meet standard criteria for adequacy, they also suggest that the study data were not substantially influenced by common method bias.

3.2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis of Variables

This study investigated the correlations among student leadership status, educational background (with general high school students as the reference group), self-assessed achievement, perceived peer support, academic hope, professional identity, and academic adjustment. The analyses indicated significant positive correlations across all examined variables, except for educational background. Specifically, educational background was significantly negatively correlated with leadership status, self-assessed achievement, academic hope, and academic adjustment. In contrast, the associations between educational background and perceived peer support, as well as professional identity, did not reach statistical significance. For detailed statistics, see

Table 1.

3.3. Test the Differences between Educational Backgrounds for Variables

The independent samples t-test was utilized to examine the variances among variables of different sources of higher vocational college students

.The results, displayed in

Table 2, revealed a significant distinction between vocational high school students and general high school students in terms of academic adjustment (

t = 4.86,

p < 0.001) and academic hope (

t = 5.47,

p < 0.001). Both academic adjustment and academic hope were notably lower for vocational high school students compared to general high school students. Conversely, no significant variances were observed in the variables of professional identity (

t =1.18,

p = 0.24) and perceived peer support (

t = -0.03,

p = 0.98). Nonetheless, there were marginally significant differences between vocational high school students and general high school students in the dimensions of perceived peer emotional support (

t =1.91,

p = 0.05) and perceived peer instrumental support (

t = -1.94,

p = 0.05). Specifically, vocational high school students perceived lower peer emotional support compared to general high school students, while they perceived higher instrumental support. The variance in perceived peer information support between vocational high school students and general high school students was not significant (

t = 0.16,

p = 0.87).

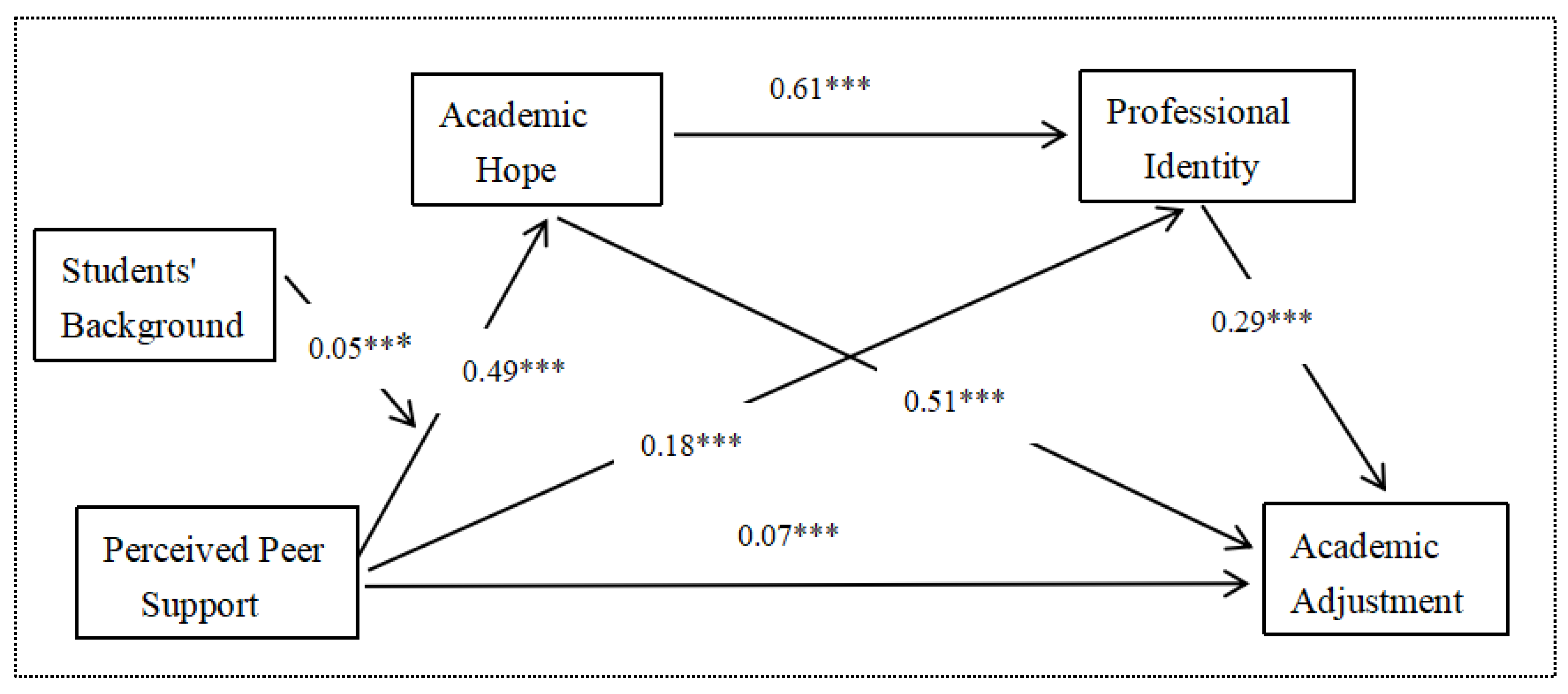

3.4. Moderated Chain-Mediating Model Test

In this study, student leader status and self-assessed grade level were considered control variables due to their significant correlations with perceived peer support, academic hope, professional identity, and academic adjustment. Perceived peer support was considered as the independent variable, academic adjustment as the dependent variable, and academic hope and professional identity as mediating variables. The SPSS macro program PROCESS model 6 by Hayes (2013) was utilized to examine the chain mediation effect of academic hope and professional identity [

48].The results were described in

Table 3 and

Table 4.The results indicated that perceived peer support as a significant positive predictive effect on academic adjustment (

β = 0.07, SE = 0.01,

p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis 1. Additionally, perceived peer support significantly positively predicted academic hope (

β = 0.51, SE = 0.01,

p < 0.001), which in turn positively predicted academic adjustment (

β = 0.07, SE = 0.01,

p < 0.001). The Bootstrap method with bias correction at the percentile validated the significant mediating effect of academic hope between perceived peer support and academic adjustment

, with a mediating effect value of 0.26 and a 95% confidence interval of [0.24, 0.27]. The mediating effect of academic hope accounted for 55.32% of the total effect, which is consistent with Hypothesis 2. Similarly, perceived peer support has a significant predictive effect on professional identity (

β = 0.18, SE = 0.02,

p < 0.001) and professional identity on academic adjustment (

β = 0.29, SE = 0.01,

p < 0.001). The mediating effect of professional identity was also significant, with a mediating effect value of 0.05 and a 95% confidence interval of [0.04, 0.06]. This mediating effect accounted for 10.64% of the total effects , confirming Hypothesis 3. Additionally, academic hope has a significant predictive effect on professional identity (

β = 0.61

, SE = 0.03,

p < 0.001) and professional identity on academic adjustment (

β = 0.29, SE = 0.01,

p < 0.001). The chain mediation effect of academic hope and professional identity between perceived peer support and academic adjustment was significant, with a mediation effect value of 0.09 and a 95% confidence interval of [0.08, 0.10]. This mediation effect represented 19.15% of the total effect, supporting Hypothesis 4.

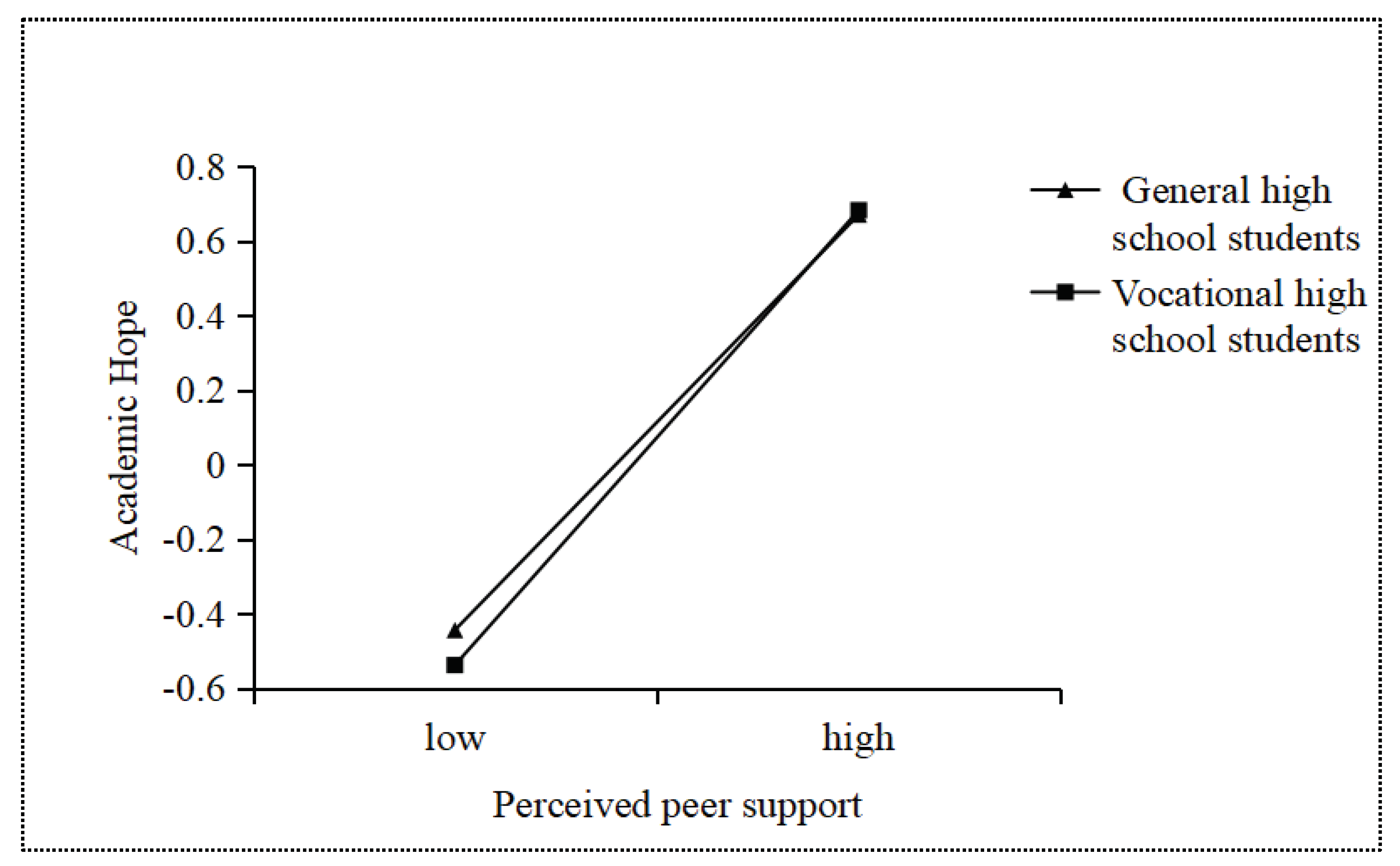

In exploring the moderated mediation model, this study used the PROCESS Model 83 to test the moderating effect of educational backgrounds (using general high school students as a reference). Results indicated (see

Figure 2 and

Table 3) that the interaction between perceived peer support and educational backgrounds had a significant positive predictive effect on academic hope (

β = 0.05, SE = 0.02,

p<0.001), suggesting that educational backgrounds played a moderating role in the relationship between perceived peer support and academic hope. Specifically, a simple slope test revealed (see

Figure 3) that students from vocational high schools (

β = 0.54,

t = 40.31,

p<0.001, 95% CI [0.51, 0.56]) experienced a greater improvement in academic hope due to perceived peer support compared to students from general high schools (

β = 0.49,

t = 46.60,

p<0.001, 95% CI [0.47, 0.51]).

Note2:This diagram represents a streamlined version of the mediation-moderation model, with control variables omitted for simplicity. It includes the results of the mediating effect test, as well as the moderating influence of the interaction between perceived peer support and educational backgrounds on the initial stage of academic hope.

In this study, we utilized the product coefficient method to investigate the significance of the moderated chained-mediating effect. The results indicated that the interaction coefficient (0.05) multiplied by the coefficients of the mediating variables (0.61 and 0.29) yielded a statistically significant value (0.05 × 0.61 × 0.29 = 0.009,

p< 0.05), suggesting that educational backgrounds played a moderator role in the chained-mediation effect [

48,

49]. Furthermore, according to the methods of Edwards and Lambert,the analysis of the moderated chained-mediating effect revealed that for vocational high school students[

49]. The results (see

Table 5) showed that vocational high school students, the indirect effect of peer support through academic hope and professional identity on academic adjustment was 0.16, with a 95% confidence interval [0.14, 0.17] excluding zero, indicating significance. Similarly, for general high school students, the indirect effect was 0.14, with a 95% confidence interval [0.13, 0.16] also excluding zero. The comparison across educational back grounds showed a difference in the indirect effect of the chain-mediating pathway of “perceived peer support - academic hope - professional identity - academic adjustment ” , with a value of 0.01 and a 95% confidence interval [0.001, 0.011], further supporting Hypothesis 5.

4. Discussion

4.1. A Positive Effect of Perceived Peer Support on Academic Adjustment

The study supported Hypothesis 1 by showing that perceived peer support significantly and positively predicted the academic adjustment of higher vocational college students, which is consistent with previous research [19–22]. According to SSR theory, perceived peer support has been considered a vital social capital that contributes to an individual’ s adjustment and growth through emotional, informational, material, and evaluative support [

15]. This study highlighted the unique value and essential role of perceived peer support in the academic adjustment of higher vocational college students, emphasizing the practical implications of SSR theory in the higher education context. Perceived peer support has served as a mechanism and resource to alleviate stress and has aided higher vocational college students in adapting to new academic and social environments [

50].

Perceived peer support has been found to enhance students’ understanding of learning importance and help address learning obstacles, encouraging active engagement in learning activities [

51]. Additionally, emotional support from peers improves higher vocational college students’ attitudes towards school and peers, boosts learning motivation, and enhances adaptability.Therefore, from the analysis of multiple theoretical frameworks and the empirical results of this study, perceived peer support is an important factor in promoting academic adjustment of higher vocational college students. This finding not only provides new evidence for the study of academic adjustment of higher vocational college students, but also provides a theoretical basis for designing effective perceived peer support intervention strategies.

4.2. The Mediating Effect of Academic Hope

The study findings demonstrated that perceived peer support played a crucial role in higher vocational college students’ academic adjustment by positively influencing academic hope, which is consistent with previous researches [

3,

31,

32], further emphasizing the importance of academic hope as a key psychological and cognitive driving force in enhancing the academic achievement expectations and self-confidence of higher vocational college students. The results can be analyzed through the lenses of COR theory and SSR theory. Perceived peer support, a valuable social resource, not only offered emotional support and practical assistance to higher vocational college students but also aided in the accumulation and preservation of academic hope, creating a positive cycle of resource gain [14–16]. This process has enhanced students’ motivation, learning capacity, self - efficacy, and academic achievement. Additionally, by imitating successful peer behaviors, students can improve their academic adjustment.

The cognitive theory of hope emphasizes motivation-oriented goal setting and path-oriented planning to achieve these goals [

23,

29]. Perceived peer support in higher education helps students identify diverse paths to achieve academic goals, enhancing problem-solving strategies and resilience. Additionally, positive interactions and experience sharing among peers motivate students to persevere through challenges and pressures, boosting self-confidence and expectations of completing their studies.

In summary, this study found that perceived peer support significantly and positively influenced higher vocational college students’ academic adjustment through the mediation of academic hope, which not only enriches the research field of academic adjustment theory, but also provides important strategic guidance for higher education practice, especially in designing perceived peer support systems and promoting academic hope strategies. These findings underscore the importance of implementing perceived peer support programs and academic hope interventions in higher vocational colleges.

4.3. The Mediating Effect of Professional Identity

In this study, we explored the mechanism of perceived peer support in facilitating higher vocational college students’ academic adjustment and found that professional identity played a mediating role in this process. This finding is consistent with the existing studies [34–37] and reinforced in-depth understanding of the mechanism of the mediating role of professional identity in perceived peer support for higher vocational college students’ academic adjustment. The findings of this study can be interpreted from two theoretical perspectives: COR theory [

14] and social identity theory [53].From the perspective of COR theory, individuals enhance adaptation by accumulating and conserving personal resources [

14], and perceived peer support, as an important social resource [

16], not only directly provided emotional and informational support, but also indirectly promoted academic adjustment by enhancing professional identity. Professional identity, as an intrinsic resource, enhanced students’ sense of professional belonging and value identity [

45], which in turn promoted the accumulation of resources in their learning process, forming a positive cycle of resource gain [

14]. Social Identity theory explains how individuals form their self-identity through the social groups they are from and how this identity influences their behaviors and attitudes [

52]. Perceived peer support among higher vocational college students strengthened their sense of belonging to their professional group, leading to a deeper identification with their majors [

53]. Positive peer-to-peer communication not only boosted students’ identification with their professional group, but also increased their awareness of the value and importance of their majors, thereby sparking intrinsic motivation for learning [

54]. When students were interested in their major and recognize its value, they were more likely to invest effort and achieve better achievements [

55]. Moreover, a strong professional identity helped higher vocational college students in academic adjustment by encouraging the use of effective learning strategies.

In summary, perceived peer support indirectly enhanced academic adjustment of higher vocational college students by promoting professional identity, a process that not only reflects the resource gain principle of COR theory, but also confirms the applicability of social identity theory in higher vocational education.

4.4. The Chain-Mediating Effect of Academic Hope and Professional Identity

The study supported Hypothesis 4 by showing that academic hope and professional identity played a chain- mediating role between perceived peer support and academic adjustment, which is consistent with previous research [

32,

39,

40]. This finding is strongly supported by COR theory, particularly the theory’s view on the principle of resource gain. In this theoretical perspective, perceived peer support is an important social resource [

16], and it is particularly important for higher vocational college students because the dual challenges of academic and career readiness require them to be able to adapt quickly in changing educational and professional environments. Perceived peer support not only provided emotional support and validation, which helped students minimize the potential loss of resources in the face of academic challenges, but also helped them build and sustain academic hope. Academic hope and professional identity were considered important individual resources for higher vocational college students [

14]. Academic hope reflected students’ confidence and motivation to achieve their academic goals, enabling them to maintain a positive attitude and proactively seek solutions in the face of academic challenges [

23,

29]. This positive attitude motivates them to take action to maintain and increase this resource. When higher vocational college students have higher hopes and expectations for their academic and future careers, they are more likely to explore related career fields in depth, thus enhancing their sense of identity with their majors [

38].This sense of identity not only enhances their confidence in career decision-making, but also promotes more positive learning attitudes and behaviors. As a key bridge connecting academic hope and academic adjustment, professional identity had a significant impact on academic adjustment of higher vocational college students. Enhanced professional identity led students to be more actively engaged in the learning process and to better utilize learning resources, thus enhancing their academic adjustment [

32].

In a word, it has been observed that in the higher vocational education, perceived peer support, academic hope and professional identity together constitute a dynamic system that promotes academic adjustment, perceived peer support, as an external resource to initiates the system, activates the two key internal resources of academic hope and professional identity. Perceived peer support first strengthened academic hope, then further promoted professional identity through academic hope, and ultimately this chain gain effect promoted academic adjustment. This process reflected the accumulation and transformation of resources, where each step was the result of resource gains that interacted with each other to drive the final academic adjustment. This chain mediation not only has enriched our understanding of the resource gain process, but also has provided a new perspective for understanding the academic adjustment and a theoretical basis for designing interventions in improving the academic adjustment of higher vocational college students.

4.5. The Moderating Effect of Educational Backgrounds

Our study further identified a significant moderating role of students’ backgrounds in the effect of perceived peer support on their academic hope. Although perceived peer support appeared to be critical for all students, it had a stronger positive predictive effect on the academic hope of students from vocational high schools. This result was in line with the expectations of COR theory, that environmental factors and individual differences jointly influence the process of resource retention and accumulation [

14]. In addition, this study also found that there were significant differences in perceived peer support among higher vocational college students from different educational backgrounds, with students from vocational high schools performing better than students from general high schools in perceived instrumental support, and students from general high school backgrounds performing better in perceived emotional support. These differences not only reflected the different needs of the two groups for types of support, but also provided important insights into our understanding of why perceived peer support had a more significant effect on the academic hopes of higher vocational college students from vocational high schools.

For higher vocational college students with vocational high school backgrounds, instrumental peer support (e.g., academic guidance and experience sharing), had a critical effect on their academic development [

56]. This support directly addressed their need for specific, practical resources [

57] and provided them with the confidence and motivation to achieve their academic goals, thus positively contributing to their academic hopes. In contrast, for higher vocational college students from general high schools may face academic and personal development pressures of a different nature and rely more on emotional support from peers to cope with these challenges [

58]. Emotional support, while helpful in relieving stress and enhancing feelings of self-worth and belonging, was however, relatively ineffective in directly promoting academic hope because of its more indirect effect on academic hope and its potential shortcomings in providing specific strategies and resources for achieving academic goals.

These findings suggested that when considering the relationship of perceived peer support with academic hope for higher vocational college students., it was important not only to focus on the overall level but also to explore in depth how different dimensions of support affected students differently based on their specific backgrounds. This not only enriched the application of COR theory in education, but also provided important guidance for the targeted development of educational interventions and perceived peer support strategies for academic hope enhancement. For higher vocational college students from vocational high school backgrounds, interventions that enhanced instrumental support were particularly critical for enhancing academic hope.

5. Theoretical Innovations and Practical Implications

5.1. Theoretical Innovations

Firstly, COR theory was initially widely used in the fields of organizational psychology and health psychology to explain how individuals manage stress and conserve their resources. The application of COR theory to educational psychology, particularly in exploring academic adjustment of higher vocational college students, showcased its innovative cross-domain application.This migration not only enriched the theoretical foundation of educational psychology, but also provided new perspectives for understanding the problem of academic adjustment of higher vocational college students.

Secondly, by applying the principle of resource gain in COR theory to analyze the chain- mediating role of academic hope and professional identity between perceived peer support and academic adjustment of higher vocational college students, we not only uncovered the direct relationship between these variables but also explored how they interact through a continuous process of resource gain [

14,

16]. This analytical approach provided a more detailed and dynamic framework of understanding, which helped to reveal the deeper mechanisms of action that promote academic adjustment of higher vocational college students.

Thirdly, most previous studies have focused on the effects of environmental and individual factors on academic adjustment, and few studies have focused on the effects of the interaction of group, environmental and individual factors on academic adjustment [

13]. This study examined the moderating effect of different educational backgrounds in the effect of perceived peer support on academic hope, and it was found that perceived peer support contributed more significantly to the academic hope of higher vocational college students from vocational high schools than students from general high schools, revealing the boundary conditions under which perceived peer support affected the academic adjustment of higher vocational college students.

5.2. Practical Implications

Firstly, the study found the facilitating effect of perceived peer support on academic adjustment of higher vocational college students. This reveals that educators should strengthen perceived peer support networks and encourage positive supportive relationships among students.

Secondly, the study found that academic hope and professional identity mediate the relationship between perceived peer support and academic adjustment in higher vocational college students. This highlighted the importance for educators to implement strategies that enhance academic hope and professional identity in these students, thus aiding their academic adjustment. Educational initiatives like seminars, workshops, and personalized tutoring sessions could help students set clear academic goals, make plans to achieve them, and develop coping skills for managing challenges and stress. On the one hand, involving high-achieving students or alumni with industry experience as academic advisors or mentors could provide valuable support in overcoming academic obstacles, offering professional guidance, and strengthening students’ professional identity.

Thirdly, the study showed that perceived peer support had a stronger positive predictive power on academic hope of higher vocational college students from vocational high schools than those from general high schools.This finding underscored the importance of customizing academic support and counseling services for students from different educational backgrounds when designing educational interventions and perceived peer support strategies to meet their different learning needs and challenges.

6. Limitations and Future Directions

This study is constrained by both subjective and objective factors, leading to certain limitations and areas for improvement.

First, the cross-sectional research design used in this study did not allow for the identification of causal relationships between variables, which limited in-depth understanding of the interactions between perceived peer support, academic hope, professional identity, and academic adjustment. Future studies should use longitudinal or experimental designs to verify causality. For example, longitudinal studies to track the long-term effects of perceived peer support on academic hope and professional identity, or randomized controlled experiments to assess the effects of specific peer support interventions on academic adjustment.

Second, the sample for this study predominantly consisted of students from 35 higher vocational colleges across 13 provinces and cities in China, which may not adequately represent higher vocational college students in other regions or cultural contexts. Future research should expand the sample to include higher vocational students from different countries and cultures to explore how cultural differences affect the relationship between perceived peer support and academic adjustment, and whether the mediating roles of academic hope and professional identity are consistent across cultures.

Third, While the role of academic hope and professional identity as mediating variables has been confirmed, there are other unexplored factors that likely influence academic adjustment, for example, coping styles [

59] and proactive personalities [

60] , such factors may also affect academic adjustment of higher vocational college students. Future research should explore additional mediating variables (e.g., coping styles, proactive personality, etc.) and moderating variables (e.g., academic performance, grade level, etc.) should be explored to develop a more comprehensive theoretical model to deeply understand and reveal the complex mechanisms affecting academic adjustment of higher vocational college students.

In addition, this study mainly focuses on the analysis of the relationship between variables, and lacks the discussion of specific practical applications and interventions based on the findings of the study. In the future, empirical intervention studies should be designed based on the findings of this study, such as the development of perceived peer support enhancement programs, academic hope cultivation workshops, and professional identity enhancement activities, to evaluate the effects of these interventions on enhancing higher vocational college students’ academic adjustment

7. Conclusions

This cross-sectional study found that perceived peer support not only directly predicted the academic adjustment of higher vocational college students, but also indirectly through the independent mediating effects of academic hope and professional identity, as well as the chain-mediating effect of academic hope to professional identity. Furthermore, it was observed that higher vocational college students from vocational high school experienced a more pronounced enhancement in academic hope due to perceived peer support than those from general high school, underscoring the moderating effect of educational background on the relationship between perceived peer support and academic hope. These findings provided new theoretical insights into the complex mechanisms of academic adjustment for higher vocational students and offered valuable guidance for educational practice and policy development.

Notes

| 1 |

Source: National Statistical Bulletin on the Development of Education, 2023. http://m.moe.gov.cn/ jybsjzl/ sjzlfztjgb/202307/t20230705_1067278.html |

References

- Tao, S. Discussing College Freshmen’ s Entry Adaptation from the Perspective of Lifespan Development. J. Beijing Norm. Univ. Hum. Soc. Sci. 2000, 2, 81–87. [Google Scholar]

- Larose, S.; Duchesne, S.; Litalien, D.; Denault, A. S.; Boivin, M. Adjustment trajectories during the college transition: Types, personal and family antecedents, and academic outcomes. Res. High. Educ. 2019, 60, 684–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, W. L. L.; Cheung, S. H. The role of hope in college transition: Its cross-lagged relationships with psycho-social resources and emotional well-being in first-year college students. J. Adolesc. 2024. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donaldson, C.; Moore, G.; Hawkins, J. A systematic review of school transition interventions to improve mental health and well being outcomes in children and young people. School Ment. Health. 2023, 15, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, D.K.; Tam, D.K.Y.; Tsang, M.H.; Zhang, D.L.W.; Lit, D.S.W. Depression, anxiety and stress in different subgroups of first-year university students from 4-year cohort data. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 274, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, R.W.; Siryk, B. Exploratory intervention with a scale measuring adjustment to college. J. Couns. Psychol. 1986, 33, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, T.Y.; Li, H. Preliminary Study on academic adjustment of Contemporary College Students. New Explor. Psychol. 2002, (01), 44–48. [Google Scholar]

- Van Rooij, E. C.; Jansen, E. P.; van de Grift, W. J. First-year university students’ academic success: the importance of academic adjustment. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2018, 33, 749–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Yang, J. Comparative Study on Learning Adaptability between Higher Vocational College Students and Regular College Students. Chin. J. Spec. Educ. 2005, (11), 52–55. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.G. Study on the Relationship between Stress, Emotional Expression, and academic adjustment of Vocational College Students—Based on a Questionnaire Survey in Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region. Vocat. Tech. Educ. 2019, (02), 76–80. [Google Scholar]

- Ling, Y.; Chung, S.J.; Wang, L. Research on the reform of the management system of higher vocational education in China based on personality standard. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 42, 1225–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nel, K.; Govender, S.; Tom, R. The social and academic adjustment experiences of first-year students at a historically disadvantaged peri-urban university in South Africa. J. Psychol. Afr. 2016, 26, 384–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawis, R.V. Person-environment correspondence theory. In Career Choice and Development, 4th ed.; Brown, D., Ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2002; pp. 427–464. [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. The Influence of Culture, Community, and the Nested-Self in the Stress Process: Advancing Conservation of Resources Theory. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 50, 337–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E.; Freedy, J.; Lane, C.; Geller, P. Conservation of social resources: Social support resource theory. J. Soc. Pers. Relat. 1990, 7, 465–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho-Morles, J.; Slemp, G. R.; Pekrun, R.; Loderer, K.; Hou, H.; Oades, L.G. Activity achievement emotions and academic performance: A meta-analysis. Educ.Psychol. Rev. 2021, 33, 1051–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wentzel, K. R.; Jablansky, S.; Scalise, N. R. Peer social acceptance and academic achievement: A meta-analytic study. J. Educ. Psychol. 2021, 113, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wider, W.; Tanucan, J. C. M.; Lin, J.; Jiang, L.; Udang, L. N. Who makes a better university adjustment wingman: Parents or friends? PLoS One. 2023; 18. [Google Scholar]

- Altermatt, E.R. Academic support from peers as a predictor of academic self-efficacy among college students. J. Coll. Student Retent. Res. Theory Pract. 2019, 21, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worley, J.T.; Meter, D.J.; Ramirez Hall, A.; Nishina, A.; Medina, M.A. Prospective associations between perceived peer support, academic competence, and anxiety in college students. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, C.A. Peers and faculty as predictors of learning for community college students. Community Coll. Rev. 2014, 42, 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, C.R. TARGET ARTICLE: Hope Theory: Rainbows in the Mind. Psychol. Inq. 2002, 13, 249–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control. J. Cogn. Psychother. 1997, (13), 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, P.; Ling, Y.; Teng, X.C. The Impact of Social Support on the Sense of Hope: A Multiple Mediation Model. Chin. J. Health Psychol. 2019, (08), 1262–1266. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, A.; Nielsen, I.; Smyth, R.; Hirst, G. Mediating role of psychological capital in the relationship between social support and wellbeing of refugees. Int. Migr. 2018, 56, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazan-Liran, B.; Miller, P. The relationship between psychological capital and academic adjustment among students with learning disabilities and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2022, 37, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, W.L.L.; Yuen, K.W.A. Online learning stress and Chinese college students’ academic coping during COVID-19: The role of academic hope and academic self-efficacy. J. Psychol. 2023, 157, 95–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sympson, S.C. Validation of the Domain Specific Hope Scale: Exploring hope in life domains. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Kansas, Lawrence, 1999.

- D’Amico Guthrie, D.; Fruiht, V. On-campus social support and hope as unique predictors of perceived ability to persist in college. J. Coll. Student Retent.: Res. Theory Pract. 2020, 22, 522–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, D.B.; Kubota, M. Hope, self-efficacy, optimism, and academic achievement: Distinguishing constructs and levels of specificity in predicting college grade-point average. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2015, 37, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.Q. The Relationship between Social Support and academic adjustment of Vocational High School Students (Master’s thesis). Hebei Normal University, 2021.

- Qin, P.B. Characteristics of College Students' Professional Identity and Related Research (Master's thesis). Southwest University, Chongqing, 2009.

- Hu, X.N. The Relationship between Social Support, Professional Identity, and Career Decision-Making Difficulties of College Students (Master’s thesis). Heilongjiang University, 2018.

- Zhao, J.L.; Jia, X.M. Study on the Mechanism of Different Motivations for Doctoral Study on Doctoral Students' Professional Identity—Based on the Perspective of Doctoral Professional Socialization Theory. Educ. Degrees Grad. Educ. 2022, (03), 74–81. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, X.Y.; Li, Y.; Huang, Z.H.; Lei, L.; Yu, M.Y. The Impact of Teacher-Student Relationships on Graduate Students’ Self-Efficacy: A Moderated Mediation Model. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2021, (02), 174–181. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, J.J.; Niu, H.W. The Influence of Metacognition, Interpersonal Quality, and Professional Identity on the Adaptation of Freshmen. Psychol. Behav. Res. 2015, (06), 778–783. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, D.; Kim, P. B.; Milne, S.; Park, I. J. A meta-analysis of the antecedents of career commitment. J. Career Assess. 2021, 29, 502–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.M.; Liu, W.J.; Zhou, C.; Sun, Y.H.; Chen, G.X. Discrimination Perception and Learning Burnout among Vocational School Students: The Mediating Role of Professional Identity and Psychological Capital. Chin. J. Spec. Educ. 2020, (04), 76–80. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, T.; Jiang, X.; Wei, J.; Zhao, J.; Li, Z.; Li, H. Mediating effects of psychological capital on the relationship between workplace violence and professional identity among nurses working in Chinese public psychiatric hospitals: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2023; 13. [Google Scholar]

- Billett, S. Vocational Education: Purposes, Traditions and Prospects. Springer, 2011.

- Shavit, Y.; Müller, W. (Eds.) Vocational secondary education in Europe. In Schooling and the Lifecourse; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000; pp. 437–456. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, T.Y.; Su, T.; Hu, X.W.; Li, H. Development of a Learning Adaptation Scale for College Students. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2006, (05), 762–769. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Zhao, M.H.; Dong, J.H.; Gong, H.L. Preliminary Development of a Multidimen- sional Social Support Scale. Psychol. Res. 2021, (05), 418–427. [Google Scholar]

- Sympson, S.C.; Snyder, C.R. Development and initial validation of the Domain Specific Hope Scale. Unpublished manuscript, University of Kansas, Department of Psychology, Lawrence, KS, 1997.

- Lu, J.M.; Liu, W.; He, W.; Yuan, J.; Zhu, P.L.; Lu, S.H.; Tian, X.Y. A Survey on the Current Status of Emotional Quality among Contemporary Adolescents. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2009, (12), 1152–1164. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, H.; Long, L.R. Statistical Tests and Control Methods for Common Method Biases. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2004, 12, 942–950. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F.; Scharkow, M. The relative trustworthiness of inferential tests of the indirect effect in statistical mediation analysis: Does method really matter? Psychol. Sci. 2013, 24, 1918–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Wen, Z.L. Analysis of Moderated Mediation Effects Based on Structural Equation Modeling. Psychol. Sci. 2018, 41, 453–458. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, R.S. From psychological stress to the emotions: a history of changing outlooks. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1993, 44, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakimzadeh, R.; Besharat, M.A.; Khaleghinezhad, S.A.; Ghorban Jahromi, R. Peers perceived support, student engagement in academic activities and life satisfaction: A Structural equation modeling approach. Sch psychology international. 2016, 37, 240–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J.C.; Austin, W.G.; Worchel, S. An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In Organizational identity: A reader; 1979; pp. 9780203505984–16.

- Chen, Y.; He, H.; Yang, Y. Effects of Social Support on Professional Identity of Secondary Vocational Students Major in Preschool Nursery Teacher Program: A Chain Mediating Model of Psychological Adjustment and School Belonging. Sustainability . 2023, 15, 5134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2000, 25, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The general causality orientations scale: Self-determination in personality. J. Res. Pers. 1985, 19, 109–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.-Y. Career development services for vocational high school students: An exploratory study on their needs and perceptions. J. Vocat. Behav. 2001, 60, 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.Y.; Chiou, H.; Cheng, C.L. Purpose trajectories during middle adolescence: The roles of family, teacher, and perceived peer support. J. Youth Adolesc. 2022; 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Stanton-Salazar, A.; Diemer, M.; Pianta, R.C.; Hamre, B.K. The role of teacher and perceived peer support in the academic achievement of urban adolescents. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2011, 48, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Yang, J. Study on Academic Adaptation of College Students from Rural and Poverty-Alleviation Special Plan under the Preferential Admission Policy—Based on an Empirical Survey of a “Double First-Class” University. Res. High. Educ. China. 2018, (07), 30–38. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Lei, L.; Wang, X.C. The Influence of Proactive Personality on Academic Performance of College Students: The Mediating Role of Academic Self-Efficacy and Learning Adaptation. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2016, (05), 579–586. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).