Submitted:

05 April 2024

Posted:

08 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods and Materials

Participants and Setting

Animals in the Tropical House

Data Collection

Data Analysis

Results

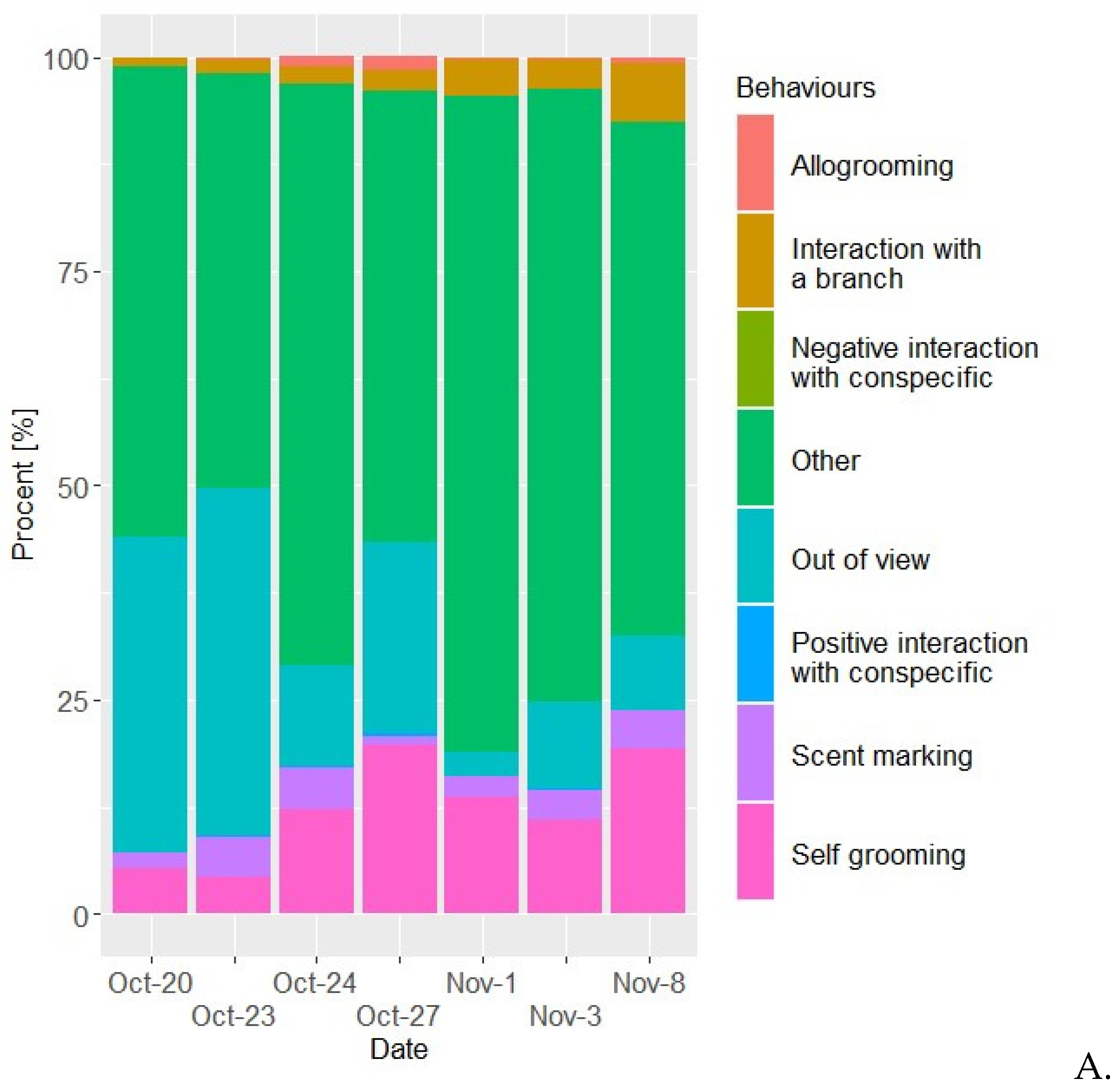

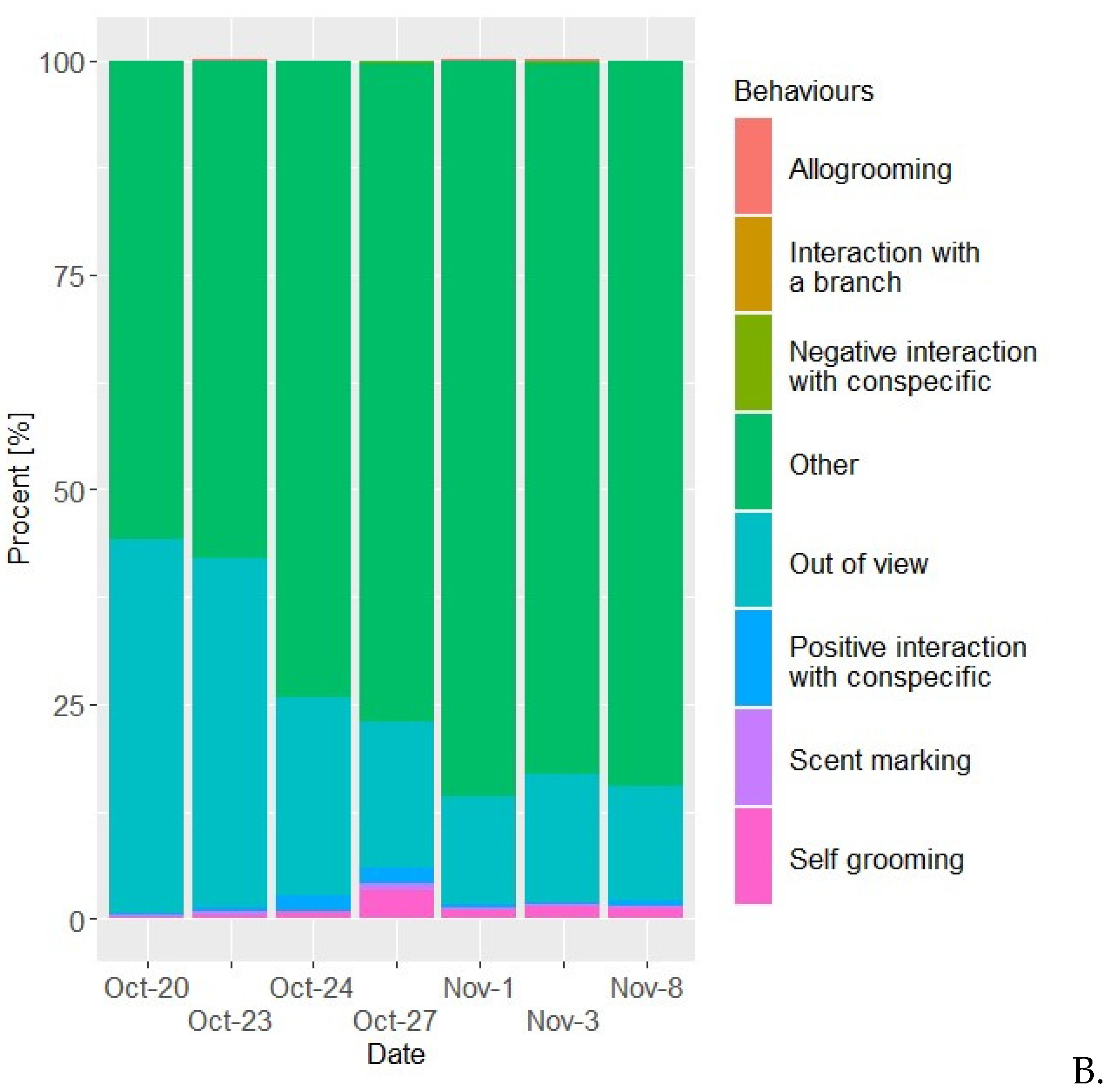

Distribution of Behaviours

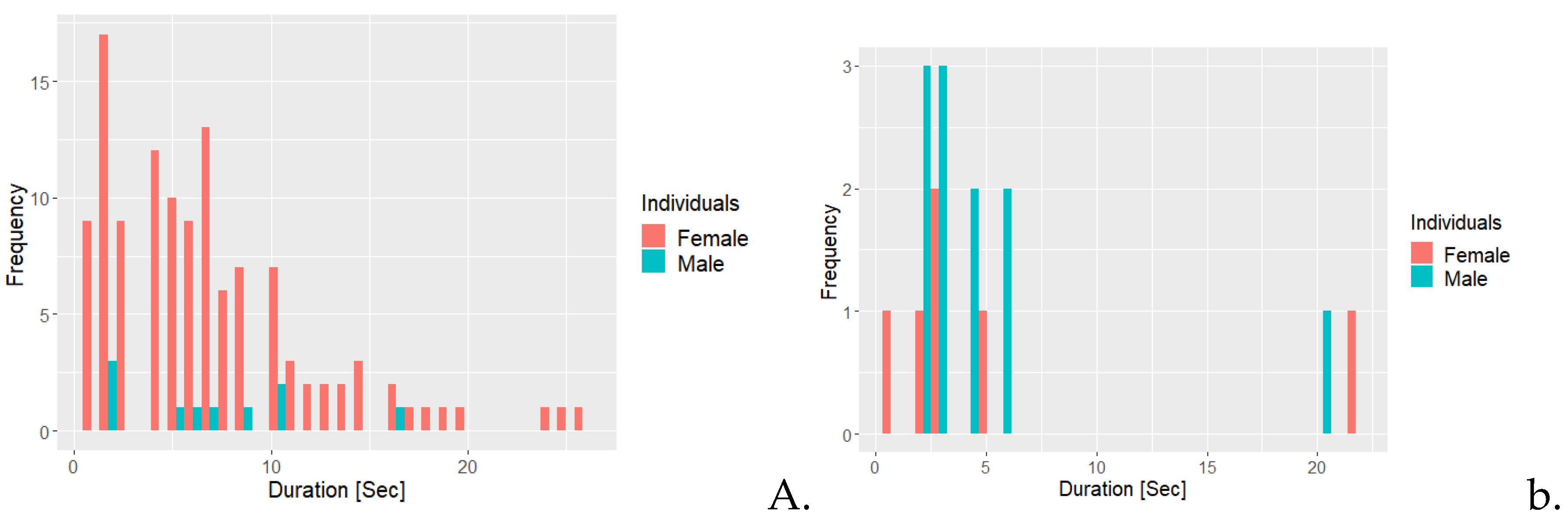

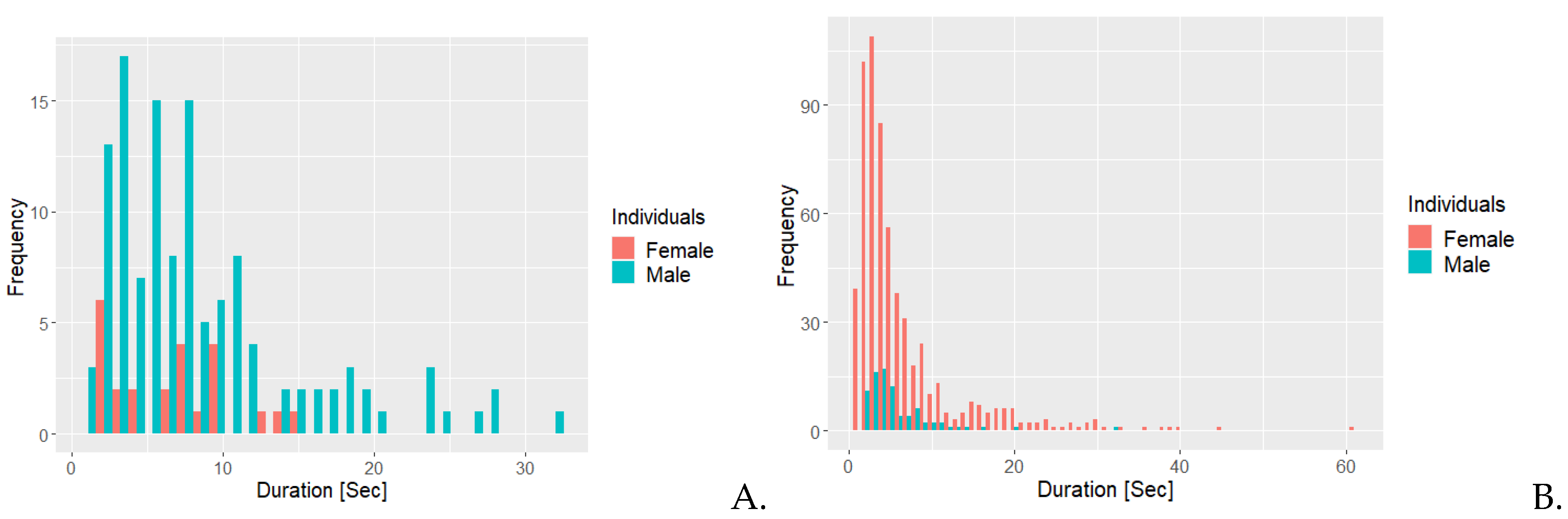

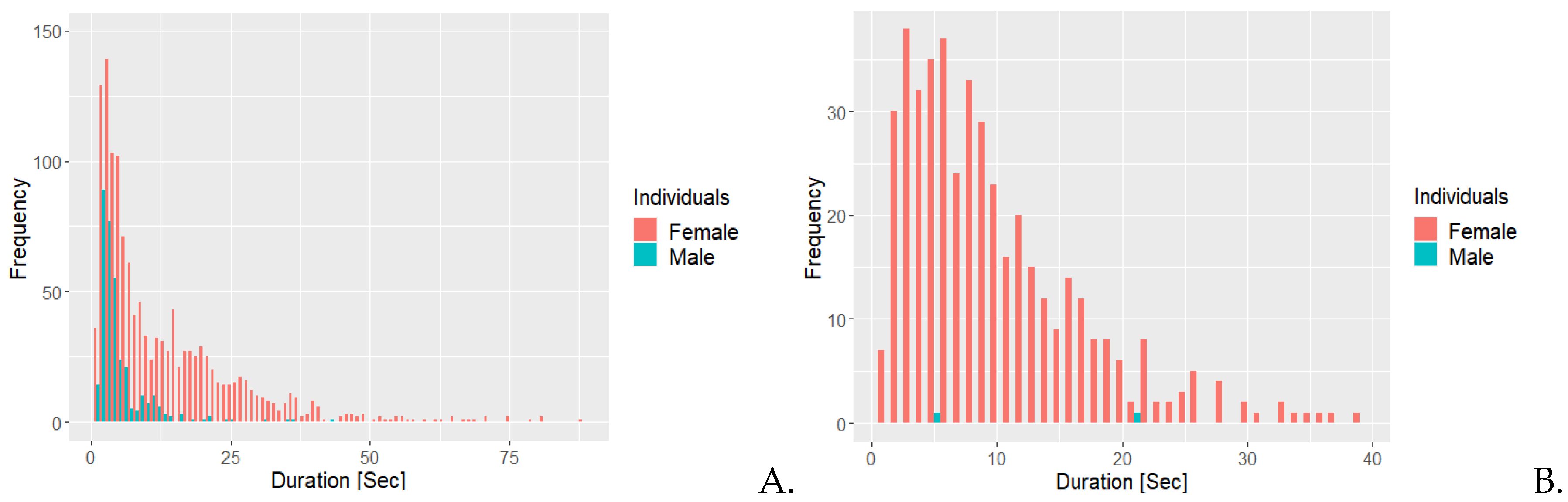

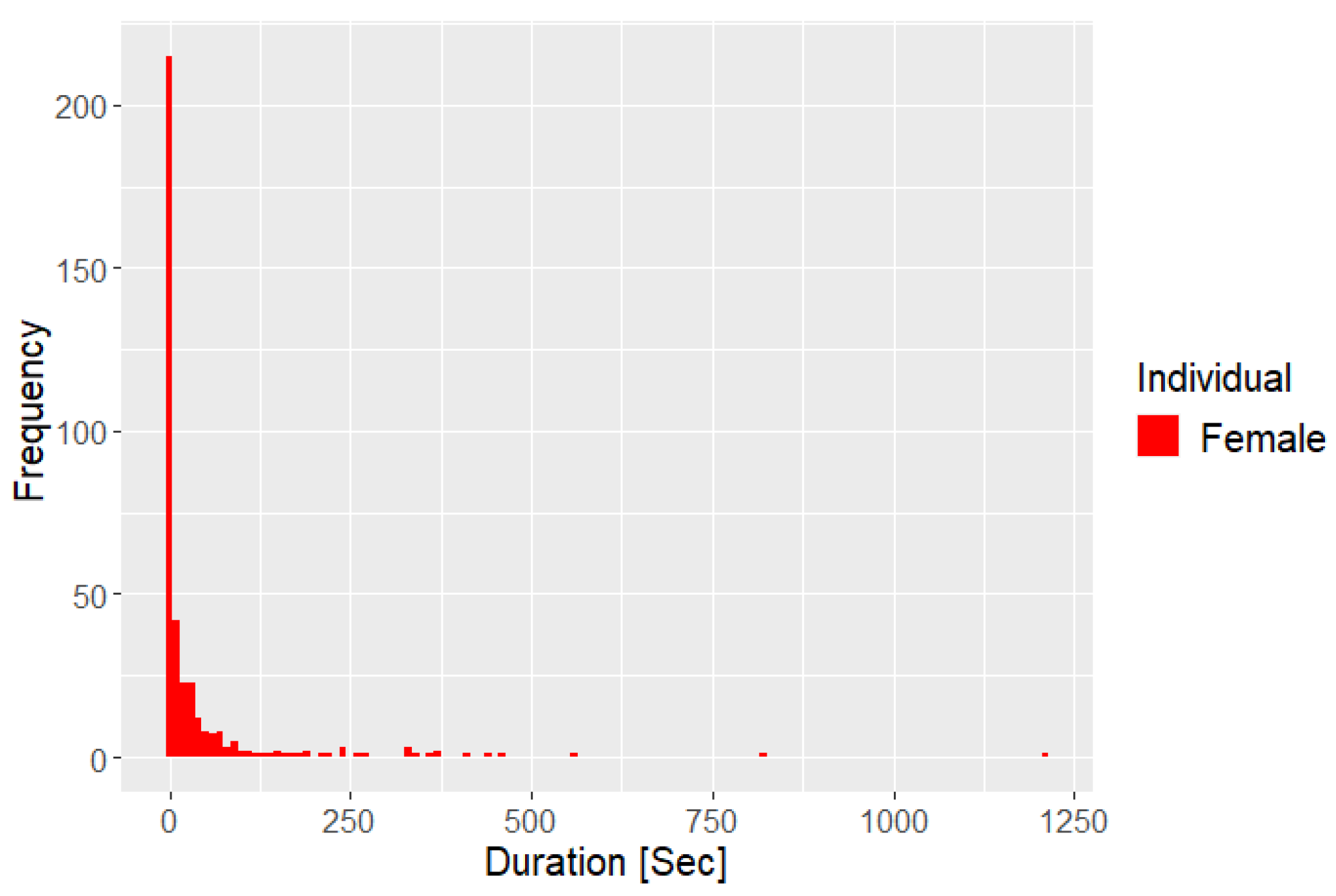

Frequency of Duration for the Expressed Behaviours

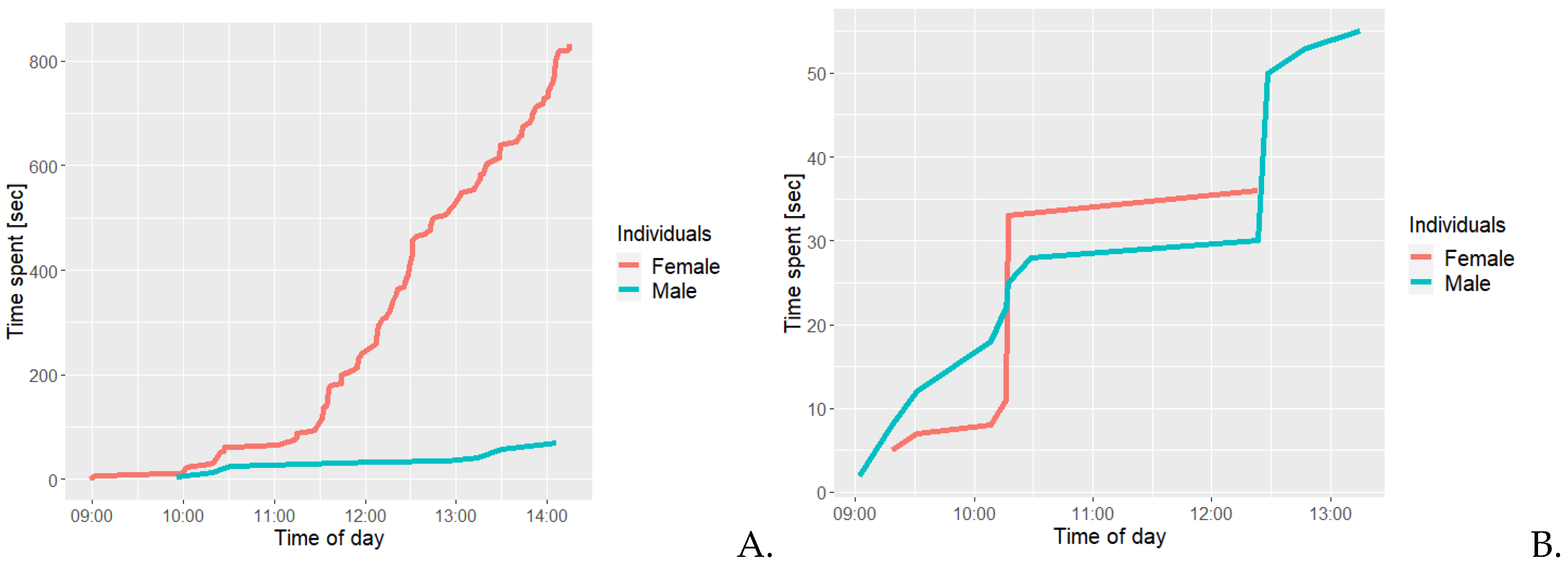

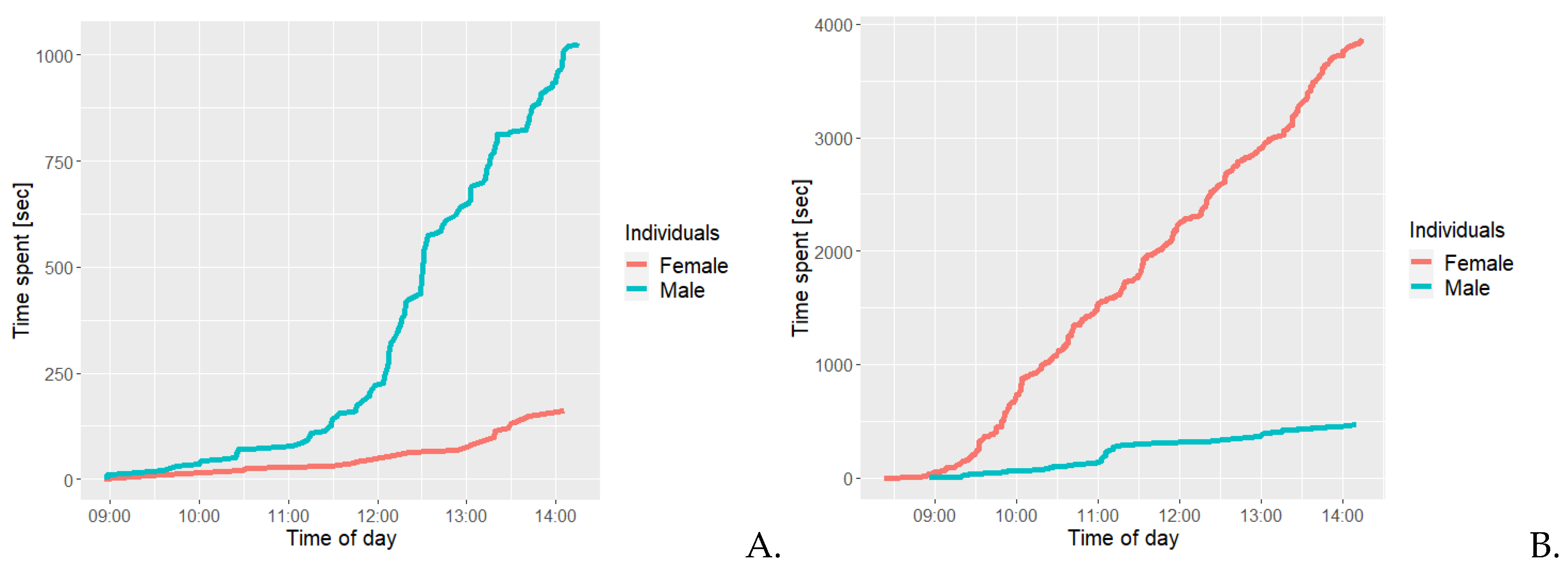

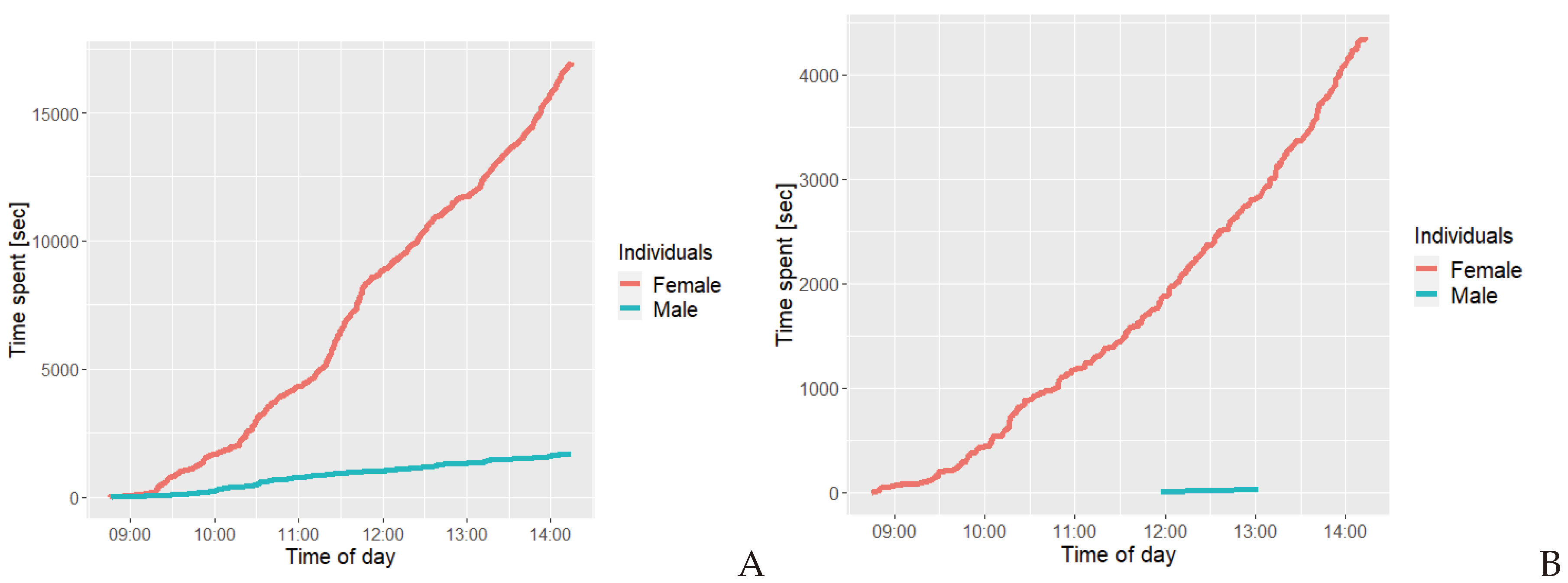

Cumulative Amount of Time Spent on Behaviours

Discussion

Expression of Individual Behaviours

The Time Distribution of Behaviours Exhibited Vary

The Repetitive Self-Directed- and Social Behaviours of the Individuals

Limitations

Conclusion

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Altmann, J., 1974. Observational Study of Behaviour: Sampling Methods. Behaviour.

- Anzenberger, G. & Falk, B., 2012. Monogamy and family life in callitrichid monkeys: deviations, dynamics and captive management. International Zoo Yearbook. [CrossRef]

- Bryan, K., Harrison, S. B., Price, E. & Wormell, D., 2017. The Impact of Exhibit Type on Behaviour of Caged and Free-ranging Tamarins. Applied Animal Behaviour Science. [CrossRef]

- Bufalo, F. S., Galetti, M. & Culoy, L., 2016. Seed Dispersal by Primates and Implications for the Conservation of a Biodiversity Hotspot, the Atlantic Forest of South America. International Journal of Primatology. [CrossRef]

- Burell, A. M. & Altman, J. D., 2006. The Effect of the Captive Environment on Activity of Captive Cotton-top Tamarins (Saquinus oedipus). Applied Animal Welfare Science.

- Candland, D. K., Blumer, E. S. & Mumford, M. D., 1980. Urine as a communicator in a New World primate, Saimiri sciureus. Animal Learning and Behaviour. [CrossRef]

- Carlstead, K. & Shepherdson, D. J., 2000. The Biology of Animal Stress: Basic Principles and Implications for Animal Welfare - Alleviating stress in zoo animals with environmental enrichment. s.l.:CABI Publishing.

- Davey, G., 2007. Visitor's Effects on the Welfare of Animals in the Zoo. Applied Animal Welfare Science.

- Dietz, J. M., 2000. Endangered Animals. s.l.:Green Wood Press.

- Franklin, S. P., 2004. Predator Influence on Golden Lion Tamarin Nesy Choice and Presleep Behaviour. s.l.:Departmnet of Biology.

- Freeland, W. J., 1976. Pathogens and the Evolution of Primate Sociality. Biotropica. [CrossRef]

- Gottlieb, D. H., Capitanio, J. P. & McCowan, B., 2013. Risk factors for stereotypic behavior and self-biting in rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta): Animal's history, current environment, and personality. American Journal of Primatology.

- Hosey, G. R., 2005. How does the zoo environment affect the behaviour of captive primates?. Applied Animal Behaviour Science. [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, G. & Rogers, L. M., 2012. Stress and stress reduction in common marmosets. Applied Animal Behaviour Science. [CrossRef]

- Kierulff, M. C. M. et al., 2012. The Golden lion tamarin Leontopithecus rosalia: a conservation success story. Zoological Society of London, 28 February, pp. 36-45.

- Kleiman, D. G., 1981. Mammalian species - Leontopithecus rosalia. American Society of Mammalogists.

- Lapenta, M. J., Procópio de Pliveira, P. & Nogueira-Neto, P., 2007. Daily activity period, home range and sleeping sites of golden lion tamarins (Leontopithecus rosalia) translocated to the União Biological Reserve, RJ-Brazil. De Gruyter, 4 October.

- Linder, A. C. et al., 2020. Using Behavioral Instability to Investigate Behavioral Reaction Norms in Captive Animals: Theoretical Implications and Future Perspectives. Symmetry. [CrossRef]

- Lutz, C. K. et al., 2022. Nonhuman primate abnormal behavior: Etiology, assessment, and treatment. American Journal of Primatology. [CrossRef]

- Maestripieri, D., 1992. A modest proposal: displacement activities as an indicator of emotions in primates. Animal Behaviour. [CrossRef]

- Mallapur, A. & Choudhury, B. C., 2003. Behavioural Abnormalities in Nonhuman Primates. Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science.

- Mallinson, J. J. C., 1995. Conservation breeding programmes: an important ingredient for species survival. Biodiversity and Conservation. [CrossRef]

- Mason, G. & Rushen, J., 2006. Stereotypic Animal Behaviour: Fundamentals and Applications to Welfare. s.l.:s.n.

- Morgan, K. N. & Tromborg, C. T., 2007. Sources of Stress in Captivity. Applied Animal Behaviour Science.

- Pertoldi, C., Bahrndorff, S., Novicic, Z. K. & Rohde, P. D., 2016. The Novel Concept of Behavioural Instability and its Potential Applications. Symmetry. [CrossRef]

- Redshaw, M. E. & Mallinson, J. J. C., 1991. Stimulation of natural patterns of behaviour: studies with golden lion tamarins and gorillas. s.l.:s.n.

- Roberts, S. C., 2012. On the Relationship between Scent-Marking and Territoriality in Callitrichid Primates. Int J Primatol. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Miranda, C. R., Kierulff, C. & Jerusalinsky, L., 2019. Leontopithecus rosalia, Golden Lion Tamarin, s.l.: International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources.

- Ruvio, E. B. & Stevenson, M. F., 2017. EAZA Best Practice Guidelines for Callitrichidae, s.l.: EAZA.

- Sanders, K. & Fernandez, E. J., 2020. Behavioral Implications of Enrichment for Golden Lion Tamarins: A Tool for Ex Situ Conservation. Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science. [CrossRef]

- Snyder, P. A., 1974. Behavior of Leontopithecus rosalia (Golden-lion marmoset) and related species: A review. Journal of Human Evolution, March, 3(2). [CrossRef]

- Stolwijk, R., 2013. The golden lion tamarin (Leontopithecus rosalia): a flagship species for the Atlantic Forest of Brazil. Universiteit Utrecht.

- Troisi, A., 2002. Displacement Activities as a Behavioral Measure of Stress in Nonhuman Primates and Human Subjects. [CrossRef]

| Behaviour | Description |

|---|---|

| Allogrooming | Licking, scratching, and pruning the other individual gently |

| Negative interaction with conspecific | Recipient of antagonistic interactions from conspecific (threat display, teeth baring, stealing food) |

| Positive interaction with conspecific | Recipient of gentle or playful interactions from conspecific without evidence of antagonistic behaviour |

| Scent marking | Individual rubbing abdomen or genitalia on branches in enclosure |

| Self grooming | Licking, pruning, or scratching self |

| Interactions with a branch | Touching, rubbing against, or looking at specific branches in the enclosure |

| Others | Locomotion, scanning, foraging, going in nestbox, excretion, yawning, vocalisation, inactive, decreasing and increasing distance from conspecific, out of view |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).