Submitted:

05 April 2024

Posted:

08 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Participants and Ethical Issues

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Anthropometric Measurements

2.4. Sarcopenia Screening

2.5. Sarcopenia Diagnosis

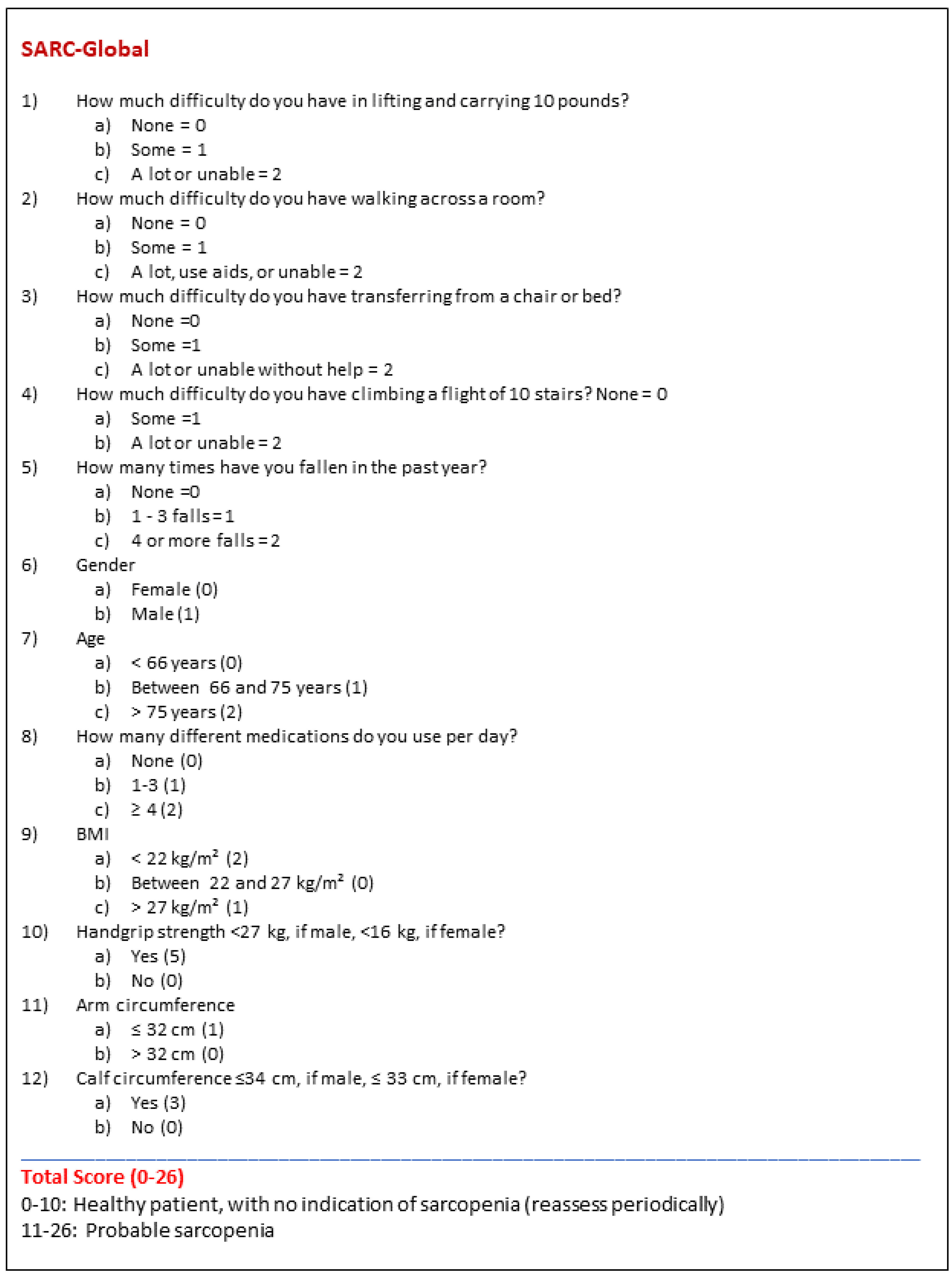

2.6. Creation of the New Sarcopenia Risk Screening Tool

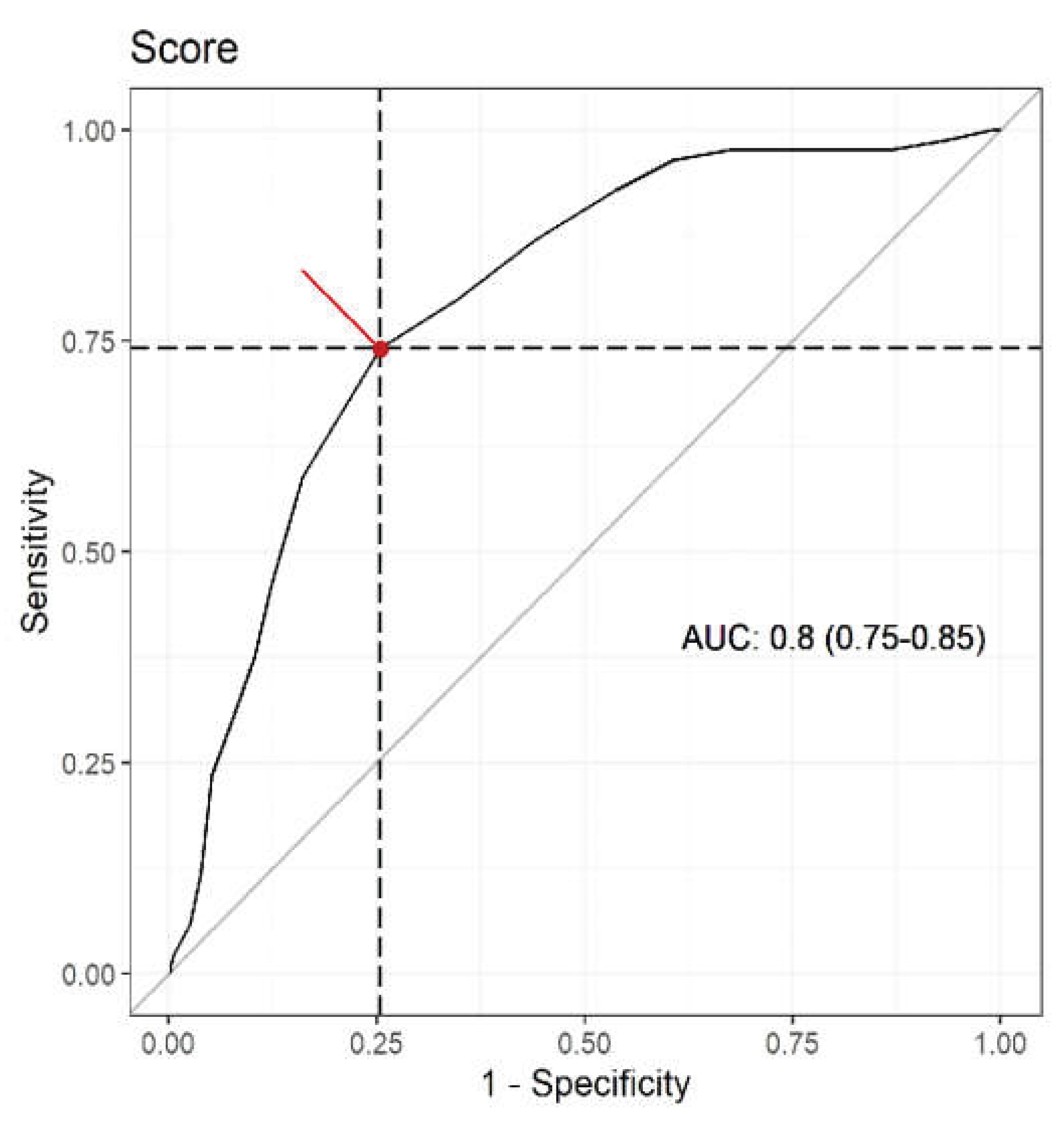

2.7. Validation of the New Sarcopenia Screening Tool

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Data

3.2. Creation of the New Sarcopenia Risk Screening Tool—Sarc-Global

3.3. Validation of the New Sarcopenia Risk Screening Tool—The Sarc-Global

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Baeyens, J.P.; Bauer, J.M.; Boirie, Y.; Cederholm, T.; Landi, F. et al. European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People. Sarcopenia: European consensus on definition and diagnosis: Report of the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People. Age Ageing, 2010; 39, 412-23. [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner, R.N.; Koehler, K.M.; Gallagher, D.; Romero, L.; Heymsfield, S.B.; Ross, R.R.; Garry, P.J.; Lindeman, R.D. Epidemiology of sarcopenia among the elderly in New Mexico. Am J Epidemiol 1998, 147, 755-63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandre, T.S.; Duarte, Y.A.; Santos, J.L.; Wong, R.; Lebrão, M.L. Prevalence and associated factors of sarcopenia among elderly in Brazil: findings from the SABE study. J Nutr Health Aging, 2014; 18, 284-90. [Google Scholar]

- Arango-Lopera, V.E.; Arroyo, P.; Gutiérrez-Robledo, L.M.; Pérez-Zepeda, M.U. Prevalence of sarcopenia in Mexico City. European Geriatric Medicine, 2012; 3, 157-160. [Google Scholar]

- Beaudart, C.; Reginster, J.Y.; Petermans, J.; Gillain, S.; Quabron, A.; Locquet, M.; Slomian, J.; Buckinx, F.; Bruyère, O. Quality of life and physical components linked to sarcopenia: The SarcoPhAge study. Exp Gerontol, 2015; 69, 103-10. [Google Scholar]

- Landi, F.; Liperoti, R.; Russo, A.; Giovannini, S.; Tosato, M.; Capoluongo, E.; Bernabei, R.; Onder, G. Sarcopenia as a risk factor for falls in elderly individuals: results from the ilSIRENTE study. Clin Nutr, 2012; 31, 652-658. [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa-Silva, T.G.; Bielemann, R.M.; Gonzalez, M.C.; Menezes, A.M. Prevalence of sarcopenia among community-dwelling elderly of a medium-sized South American city: results of the COMO VAI? study. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2016, 7, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitamura, A.; Seino, S.; Abe, T.; Nofuji, Y.; Yokoyama, Y.; Amano, H.; Nishi, M.; Taniguchi, Y.; Narita, M.; Fujiwara, Y.; Shinkai, S. Sarcopenia: prevalence, associated factors, and the risk of mortality and disability in Japanese older adults. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle, 2021; 12, 30-38. [Google Scholar]

- Bertschi, D.; Kiss, C.M.; Beerli, N.; Kressig, R.W. Sarcopenia in hospitalized geriatric patients: insights into prevalence and associated parameters using new EWGSOP2 guidelines. Eur J Clin Nutr, 2021; 75, 653-660. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Sousa, M.Á.; Pozo-Cruz, J.D.; Cano-Gutiérrez, C.A.; Izquierdo, M.; Ramírez-Vélez, R. High Prevalence of Probable Sarcopenia in a Representative Sample From Colombia: Implications for Geriatrics in Latin America. J Am Med Dir Assoc, 2021; 22, 859-864.e1. [Google Scholar]

- Laviano, A.; Gori, C.; Rianda, S. Sarcopenia and nutrition. Adv Food Nutr Res, 2014; 71, 101-136. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, M.H.; Buehring, B. Novel Approaches to the Diagnosis of Sarcopenia. J Clin Densitom, 2015; 18, 472-477. [Google Scholar]

- Visser, M.; Schaap, L.A. Consequences of sarcopenia. Clin Geriatr Med. 2011; 27, 387-399. [Google Scholar]

- Makiura, D.; Ono, R.; Inoue, J.; Fukuta, A.; Kashiwa, M.; Miura, Y.; Oshikiri, T.; Nakamura, T.; Kakeji, Y.; Sakai, Y. Impact of Sarcopenia on Unplanned Readmission and Survival After Esophagectomy in Patients with Esophageal Cancer. Ann Surg Oncol, 2018; 25, 456-464. [Google Scholar]

- Bouchard, D.R.; Dionne, I.J.; Brochu, M. Sarcopenic/obesity and physical capacity in older men and women: data from the Nutrition as a Determinant of Successful Aging (NuAge)-the Quebec longitudinal Study. Obesity, 2009; 17, 2082-2088. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.W.; Yu, K.; Shyh-Chang, N.; Li, G.X.; Jiang, L.J.; Yu, S.L.; Xu, L.Y.; Liu, R.J.; Guo, Z.J.; Xie, H.Y.; Li, R.R.; Ying, J.; Li, K.; Li, D.J. Circulating factors associated with sarcopenia during ageing and after intensive lifestyle intervention. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle, 2019; 10, 586-600. [Google Scholar]

- Ohtsubo, T.; Nozoe, M.; Kanai, M.; Yasumoto, U.K. Association of sarcopenia and physical activity with functional outcome in older Asian patients hospitalized for rehabilitation. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2021. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Bahat, G.; Bauer, J.; Boirie, Y.; Bruyère, O.; Cederholm, T. et al. Writing Group for the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People 2 (EWGSOP2), and the Extended Group for EWGSOP2. Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing, 2019; 48, 16-31. [Google Scholar]

- Malmstrom, T.K.; Morley, J.E. SARC-F: a simple questionnaire to rapidly diagnose sarcopenia. J Am Med Dir Assoc, 2013; 14, 531-532. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, J.; Leung, J.; Morley, J.E. Validating the SARC-F: a suitable community screening tool for sarcopenia? J Am Med Dir Assoc, 2014; 15, 630-634. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Rodríguez, D.; Marco, E.; Dávalos-Yerovi, V.; López-Escobar, J.; Messaggi-Sartor, M.; Barrera, C. et al. Translation and Validation of the Spanish Version of the SARC-F Questionnaire to Assess Sarcopenia in Older People. J Nutr Health Aging, 2019; 23, 518-524. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Kong, Y.; Chen, H.; Chu, A.; Song, G.; Cui, Y. Accuracy and prognostic ability of the SARC-F questionnaire and Ishii's score in the screening of sarcopenia in geriatric inpatients. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2019; 52, e8204. [Google Scholar]

- Zasadzka, E.; Pieczyńska, A.; Trzmiel, T.; Pawlaczyk, M. Polish Translation and Validation of the SARC-F Tool for the Assessment of Sarcopenia. Clin Interv Aging, 2020; 22, 567-574. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Kim, M.; Won, C.W. Validation of the Korean Version of the SARC-F Questionnaire to Assess Sarcopenia: Korean Frailty and Aging Cohort Study. J Am Med Dir Assoc, 2018; 19, 40-45. [Google Scholar]

- Malmstrom, T.K.; Miller, D.K.; Simonsick, E.M.; Ferrucci, L.; Morley, J.E. SARC-F: a symptom score to predict persons with sarcopenia at risk for poor functional outcomes. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle, 2016; 7, 28-36. [Google Scholar]

- Bahat, G.; Yilmaz, O.; Kılıç, C.; Oren, M.M.; Karan, M.A. Performance of SARC-F in Regard to Sarcopenia Definitions, Muscle Mass and Functional Measures. J Nutr Health Aging, 2018; 22, 898-903. [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa-Silva, T.G.; Menezes, A.M.; Bielemann, R.M.; Malmstrom, T.K.; Gonzalez, M.C. Enhancing SARC-F: Improving Sarcopenia Screening in the Clinical Practice. J Am Med Dir Assoc, 2016; 17, 1136-1141. [Google Scholar]

- Voelker, S.N.; Michalopoulos, N.; Maier, A.B.; Reijnierse, E.M. Reliability and Concurrent Validity of the SARC-F and Its Modified Versions: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc, 2021; 16. [Google Scholar]

- Dovjak, P. Polypharmacy in elderly people. Wien Med Wochenschr, 2022; 172, 109-113. [Google Scholar]

- Schenker, Y.; Park, S.Y.; Jeong, K.; Pruskowski, J.; Kavalieratos, D.; Resick, J.; Abernethy, A.; Kutner, J.S. Associations Between Polypharmacy, Symptom Burden, and Quality of Life in Patients with Advanced, Life-Limiting Illness. J Gen Intern Med, 2019; 34, 559-566. [Google Scholar]

- Abe, N.; Kakamu, T.; Kumagai, T.; Hidaka, T.; Masuishi, Y.; Endo, S.; Kasuga, H.; Fukushima, T. Polypharmacy at admission prolongs length of hospitalization in gastrointestinal surgery patients. Geriatr Gerontol Int, 2020; 20, 1085-1090. [Google Scholar]

- Salinas-Rodríguez, A.; Manrique-Espinoza, B.; Rivera-Almaraz, A.; Ávila-Funes, J.A. Polypharmacy is associated with multiplem health-related outcomes in Mexican community-dwelling older adults. Salud Publica Mex, 2020; 62, 246-254. [Google Scholar]

- Romano-Lieber, N.S.; Corona, L.P.; Marques, L.F.G.; Secoli, S.R. Survival of the elderly and exposition to polypharmacy in the city of São Paulo, Brazil: SABE Study. Rev Bras Epidemiol, 2019; 21. [Google Scholar]

- Moreira, V.G.; Perez, M.; Lourenço, R.A. Prevalence of sarcopenia and its associated factors: the impact of muscle mass, gait speed, and handgrip strength reference values on reported frequencies. Clinics, 2019; 8. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, H.C.; Denison, H.J.; Martin, H.J. et al. A review of the measurement of grip strength in clinical and epidemiological studies: towards a standardised approach. Age Ageing, 2011; 40, 423-429. [Google Scholar]

- Carnevale, V.; Castriotta, V.; Piscitelli, P.A.; Nieddu, L.; Mattera, M.; Guglielmi, G.; Scillitani, A. Assessment of Skeletal Muscle Mass in Older People: Comparison Between 2 Anthropometry-Based Methods and Dual-Energy X-ray Absorptiometry. J Am Med Dir Assoc, 2018; 19, 793-796. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, J.; Morley, J.E.; Schols, A.M.W.J.; Ferrucci, L.; Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Dent, E.; Baracos, V.E.; Crawford, J.A.; Doehner, W.; Heymsfield, S.B.; Jatoi, A.; Kalantar-Zadeh, K.; Lainscak, M.; Landi, F.; Laviano, A.; Mancuso, M.; Muscaritoli, M.; Prado, C.M.; Strasser, F.; von Haehling, S.; Coats, A.J.S.; Anker, S.D. Sarcopenia: A Time for Action. An SCWD Position Paper. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle, 2019; 10, 956-961. [Google Scholar]

- da Luz, M.C.L.; Pinho, C.P.S.; Bezerra, G.K.A. et al. SARC-F and SARC-CalF in screening for sarcopenia in older adults with Parkinson's disease. Experimental Gerontology. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, G.R.; Al-Obaidi, M.; Dai, C.; Bhatia, S.; Giri, S. SARC-F for screening of sarcopenia among older adults with cancer. Cancer, 2021; 127, 1469-1475. [Google Scholar]

- Ushiro, K.; Nishikawa, H.; Matsui, M.; Ogura, T.; Takeuchi, T.; Goto, M. et al. Comparison of SARC-F Score among Gastrointestinal Diseases. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 2021; 10, 4099. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, X.; Tian, Z.; Thapa, S.; Sun, H.; Wen, S.; Xiong, H.; Yu, S. Comparing SARC-F with SARC-CalF for screening sarcopenia in advanced cancer patients. Clin Nutr, 2020; 39, 3337-3345. [Google Scholar]

- Ishida, Y.; Maeda, K.; Ueshima, J. et al. The SARC-F Score on Admission Predicts Falls during Hospitalization in Older Adults. J Nutr Health Aging. 2021, v.25, p399–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malas, F.Ü.; Kara, M.; Özçakar, L. SARC-F as a case-finding tool in sarcopenia: valid or unnecessary? Aging Clin Exp Res 2021, 33, 2305–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piotrowicz, K.; Głuszewska, A.; Czesak, J.; Fedyk-Łukasik, M.; Klimek, E.; Sánchez-Rodríguez, D.; Skalska, A.; Gryglewska, B.; Grodzicki, T.; Gąsowski, J. SARC-F as a case-finding tool for sarcopenia according to the EWGSOP2. National validation and comparison with other diagnostic standards. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2021, v.33, p1821–1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, Y.H.; Zhong, J.; Dong, X.; Su, Y.D.; Deng, W.Y.; Yao, X.M.; Liu, B.B.; Wang, X.Q.; Wang, X.H. Comparison of Three Screening Methods for Sarcopenia in Community-Dwelling Older Persons. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2021, 22, 746-750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.; Hu, X.; Xie, L.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, J.; Lin, J. et al. Screening Sarcopenia in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: SARC-F vs SARC-F Combined with CalF Circumference (SARC-CalF). J Am Med Dir Assoc 2018, 19, 277.e1-277.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahat, G.; Oren, M.M.; Yilmaz, O.; Kılıç, C.; Aydin, K.; Karan, M.A. Comparing SARC-F with SARC-CalF to Screen Sarcopenia in Community Living Older Adults. J Nutr Health Aging 2018, 22, 1034-1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, F.W.; Burgel, C.F.; Brito, J.E.; Baumgardt, E.; de Araújo, B.E.; Silva, F.M. SARC-CalF tool has no significant prognostic value in hospitalized patients: a prospective cohort study. Nutr. Clin. Pract 2021, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaiwat, O.; Wongyingsinn, M.; Muangpaisan, W.; Chalermsri, C.; Siriussawakul, A.; Pramyothin, P.; Thitisakulchai, P.; Limpawattana, P.; Thanakiattiwibun, C. A simpler screening tool for sarcopenia in surgical patients. PLoS One 2021, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simsek, H.; Meseri, R.; Sahin, S.; Kilavuz, A.; Bicakli, D.H.; Uyar, M. ; Savas. S.; Sarac, F.; Akcicek, F. Prevalence of sarcopenia and related factors in community-dwelling elderly individuals. Saudi Med J 2019, 40, 568-574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swan, L.; Warters, A.; O'Sullivan, M. Socioeconomic Disadvantage is Associated with Probable Sarcopenia in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: Findings from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. J Frailty Aging 2022, 11, 398-406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.H.; Chen, K.T.; Hou, M.T.; Chang, Y.F.; Chang, C.S.; Liu, P.Y.; Wu, J.; Chiu, C.J.; Jou, I.M.; Chen, C.Y. Prevalence and associated factors of sarcopenia and severe sarcopenia in older Taiwanese living in rural community: the Tianliao Old People study 04. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2014, 14, 69-75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohannon, R.W. Grip Strength: An Indispensable Biomarker For Older Adults. Clin Interv Aging 2019, 14, 1681–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Celis-Morales, C.A.; Welsh, P.; Lyall, D.M.; Steell, L.; Petermann, F.; Anderson, J.; Iliodromiti, S.; Sillars, A.; Graham, N.; Mackay, D.F.; Pell, J.P.; Gill, J.M.R.; Sattar, N.; Gray, S.R. Associations of grip strength with cardiovascular, respiratory, and cancer outcomes and all cause mortality: prospective cohort study of half a million UK Biobank participants. BMJ 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Hermosillo, H.; de León-González, E.D.; Medina-Chávez, J.H.; Torres-Naranjo, F.; Martínez-Cordero, C. , Ferrari, S. Hand grip strength and early mortality after hip fracture. Arch Osteoporos 2020, 15, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- König, M.; Spira, D.; Demuth, I.; Steinhagen-Thiessen, E.; Norman, K. Polypharmacy as a Risk Factor for Clinically Relevant Sarcopenia: Results From the Berlin Aging Study II. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2017, 73, 117-122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, J.; Xie, W.; Wang, X.; Dong, X.; Mo, Y.; Liu, D. et al. The Prevalence of Sarcopenia among Hunan Province Community-Dwelling Adults Aged 60 Years and Older and Its Relationship with Lifestyle: Diagnostic Criteria from the Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia 2019 Update. Medicina 2022, 58, 1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, S.T.H.; Tey, S.L.; Yalawar, M. et al. Prevalence and associated factors of sarcopenia in community-dwelling older adults at risk of malnutrition. BMC Geriatr 2022, 22, 997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- König, M.; Spira, D.; Demuth, I.; Steinhagen-Thiessen, E.; Norman, K. Polypharmacy as a Risk Factor for Clinically Relevant Sarcopenia: Results From the Berlin Aging Study II. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2017, 73, 117-122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pana, A.; Sourtzi, P.; Kalokairinou, A.; Velonaki, V.S. Sarcopenia and polypharmacy among older adults: A scoping review of the literature. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2022, 98, 104520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mabuchi, T.; Hosomi, K.; Yokoyama, S.; Takada, M. Polypharmacy in elderly patients in Japan: Analysis of Japanese real-world databases. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2020; 45, 991-996. [Google Scholar]

- Ambrose, A.F.; Cruz, L.; Paul, G. Falls and Fractures: A systematic approach to screening and prevention. Maturitas, 2015; 82, 85-93. [Google Scholar]

- Kojima, T.; Akishita, M.; Nakamura, T.; Nomura, K.; Ogawa, S.; Iijima, K.; Eto, M.; Ouchi, Y. Polypharmacy as a risk for fall occurrence in geriatric outpatients. Geriatr Gerontol Int, 2012; 12, 425-30. [Google Scholar]

- Helgadóttir, B.; Laflamme, L.; Monárrez-Espino, J.; Möller, J. Medication and fall injury in the elderly population; do individual demographics, health status and lifestyle matter? BMC Geriatr, 9: v.23, p.14, 2014; 14, 92. [Google Scholar]

- Veronese, N.; Stubbs, B.; Noale, M.; Solmi, M.; Pilotto, A.; Vaona, A.; Demurtas, J.; Mueller, C.; Huntley, J.; Crepaldi, G.; Maggi, S. Polypharmacy Is Associated With Higher Frailty Risk in Older People: An 8-Year Longitudinal Cohort Study. J Am Med Dir Assoc, 2017; 18, 624-628. [Google Scholar]

- Saum, K.U.; Schöttker, B.; Meid, A.D.; Holleczek, B.; Haefeli, W.E.; Hauer, K.; Brenner, H. Is Polypharmacy Associated with Frailty in Older People? Results From the ESTHER Cohort Study. J Am Geriatr Soc, 2017; 65, e27-e32. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, M.; Hu, X.; Xie, L.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, J.; Lin, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Han, Z.; Zhang, D.; Zuo, Y.; Li, Y. Comparing Mini Sarcopenia Risk Assessment With SARC-F for Screening Sarcopenia in Community-Dwelling Older Adults. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2019, 20, 53–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossi, A.P.; Micciolo, R.; Rubele, S.; Fantin, F.; Caliari, C.; Zoico, E.; Mazzali, G.; Ferrari, E.; Volpato, S.; Zamboni, M. Assessing the Risk of Sarcopenia in the Elderly: The Mini Sarcopenia Risk Assessment (MSRA) Questionnaire. J Nutr Health Aging 2017, 21, 743-749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Plano Nacional de Saúde 2020-2023. Brasília/DF, Fevereiro de 2020.

| Characteristicsa | Total (n=395) | Sarc-Global Creation | Sarc-Global validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 395 | N = 277 | N = 118 | |

| Age, years | 70.7 ± 7.54 | 70.87 ± 7.75 | 70.28 ± 7.05 |

| Females, N (%) | 320 (81) | 225 (81.2) | 95 (80.5) |

| Males, N (%) | 75 (19) | 52 (18.8) | 23 (19.5) |

| Number of medications in use | |||

| None, N (%) | 47 (11.9) | 31 (11.2) | 16 (13.6) |

| One, N (%) | 57 (14.4) | 39 (14.1) | 18 (15.3) |

| Two, N (%) | 53 (13.4) | 36 (13) | 17 (14.4) |

| Three, N (%) | 39 (9.9) | 32 (11.5) | 7 (5.9) |

| Four or more, N (%) | 199 (50.4) | 139 (50.2) | 60 (50.8) |

| Weight, kg | 67.82 ± 14.24 | 67.55 ± 14.24 | 68.47 ± 14.27 |

| Height, m | 1.57 ± 0.08 | 1.57 ± 0.08 | 1.57 ± 0.08 |

| BMI, kg/m² | 27.57 ± 5.29 | 27.48 ± 5.35 | 27.77 ± 5.16 |

| AC, cm | 32.11 ± 4.49 | 31.97 ± 4.47 | 32,42 ± 4.55 |

| CC, cm | 35.91 ± 3.53 | 35.83 ± 3.60 | 36.11 ± 3.38 |

| TSFT, mm | 23.25 ± 8.85 | 23.15 ± 8.76 | 23,49 ± 9.11 |

| BSFT, mm | 15.15 ± 7.96 | 14.93 ± 7.87 | 15.67 ± 8.20 |

| SSFT, mm | 21.89 ± 9.03 | 21.69 ± 9.20 | 22.35 ± 8.63 |

| SISFT, mm | 22.67 ± 9.37 | 22.48 ± 9.19 | 23.09 ± 9.80 |

| HGS, kg | 17.13 ± 7.16 | 16.82 ± 7.0 | 17.86 ± 7.50 |

| Variable | Category | Reference | Coefficient | OR | 95%CI (OR) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medication in use | 1-3 | None | 0.686 | 1.985 | 1.278;3.084 | <0.001 |

| ≥4 | 1.107 | 3.027 | 2.055;4.459 | <0.001 | ||

| BMI (kg/m²) | >27 | 22-27 | 0.743 | 2.102 | 1.186;3.726 | <0.001 |

| <22 | 1.063 | 2.895 | 1.436;5.857 | <0.001 | ||

| Gender | Male | Female | 0.637 | 1.890 | 0.997;3.584 | 0.058 |

| Age (years) | 66-75 | <66 | 0.790 | 2.203 | 1.229;3.948 | <0.001 |

| >75 | 1.143 | 3.137 | 1.330;7.396 | <0.001 | ||

| HGS (kg) | Low (M<27; F<16) |

Normal (M≥27; F≥16) |

1.801 | 6.057 | 2.772;13.236 | <0.001 |

| AC (cm) | ≤32 | >32 | 0.738 | 2.092 | 1.423;3.076 | <0.001 |

| CC (cm) | Low (M ≤ 34; F ≤ 33) |

Normal (M >34; F>33) | 1.368 | 3.927 | 2.173;7.096 | <0.001 |

| Measure | Sarc-Global | Sarc-F | Sarc-CalF |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | 0.744 (0.699 – 0.785) | 0.696 (0.649 – 0.740) | 0.798 (0.755 – 0.834) |

| Sensitivity | 0.741 (0.639 – 0.823) | 0.212 (0.138 – 0.311) | 0.341 (0.249 – 0.447) |

| Specificity | 0.745 (0.694 – 0.791) | 0.829 (0.783 – 0.867) | 0.923 (0.887 – 0.948) |

| PPV | 0.443 (0.365 – 0.526) | 0.254 (0.166 – 0.366) | 0.547 (0.415 – 0.674) |

| NPV | 0.913 (0.871 – 0.942) | 0.793 (0.746 – 0.834) | 0.836 (0.793 – 0.872) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).