Submitted:

06 April 2024

Posted:

08 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

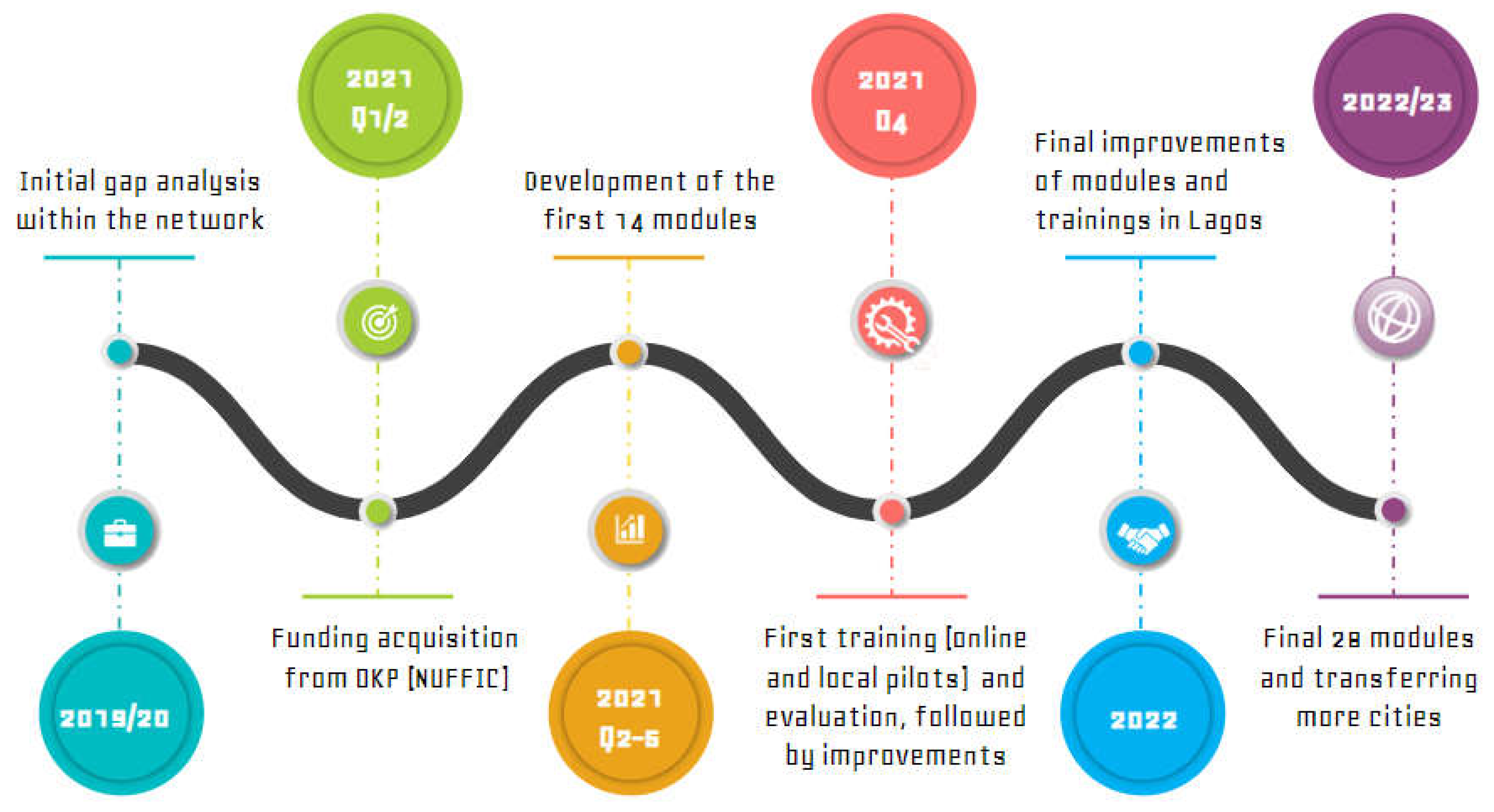

2.1. Co-Design of the Training Outline with Community Groups

2.2. Principles of the Initial Material Development

2.3. Piloting, Feedback, and Oversight by Community-Based Organizations

2.4. Refinement and Public Release of the Materials

- Instructions: This provides guidance for the trainer(s) on delivering the training, as well as a participant assessment form and attendance sheet.

- Slides: We provide visuals to help to deliver engaging, informative training. The slides can be projected, though in most cases, the content can alternatively be delivered using a whiteboard or flipchart paper and the 2-page handout (below). (Slides are not required for the training but are an important orientation for trainers).

- Handout: Handouts can be distributed during the training (paper copies) and/or made available for reference after the training (e.g., via WhatsApp). We recommend printing a few copies and laminating them for reuse (to reduce printing).

- Videos: Most modules are accompanied by a short video describing how to deliver the materials and/or demos of the tools used. (Videos are not required for the training but can be shared with training participants and are an important orientation for trainers).

2.5. The Importance of Female Leadership

3. Results

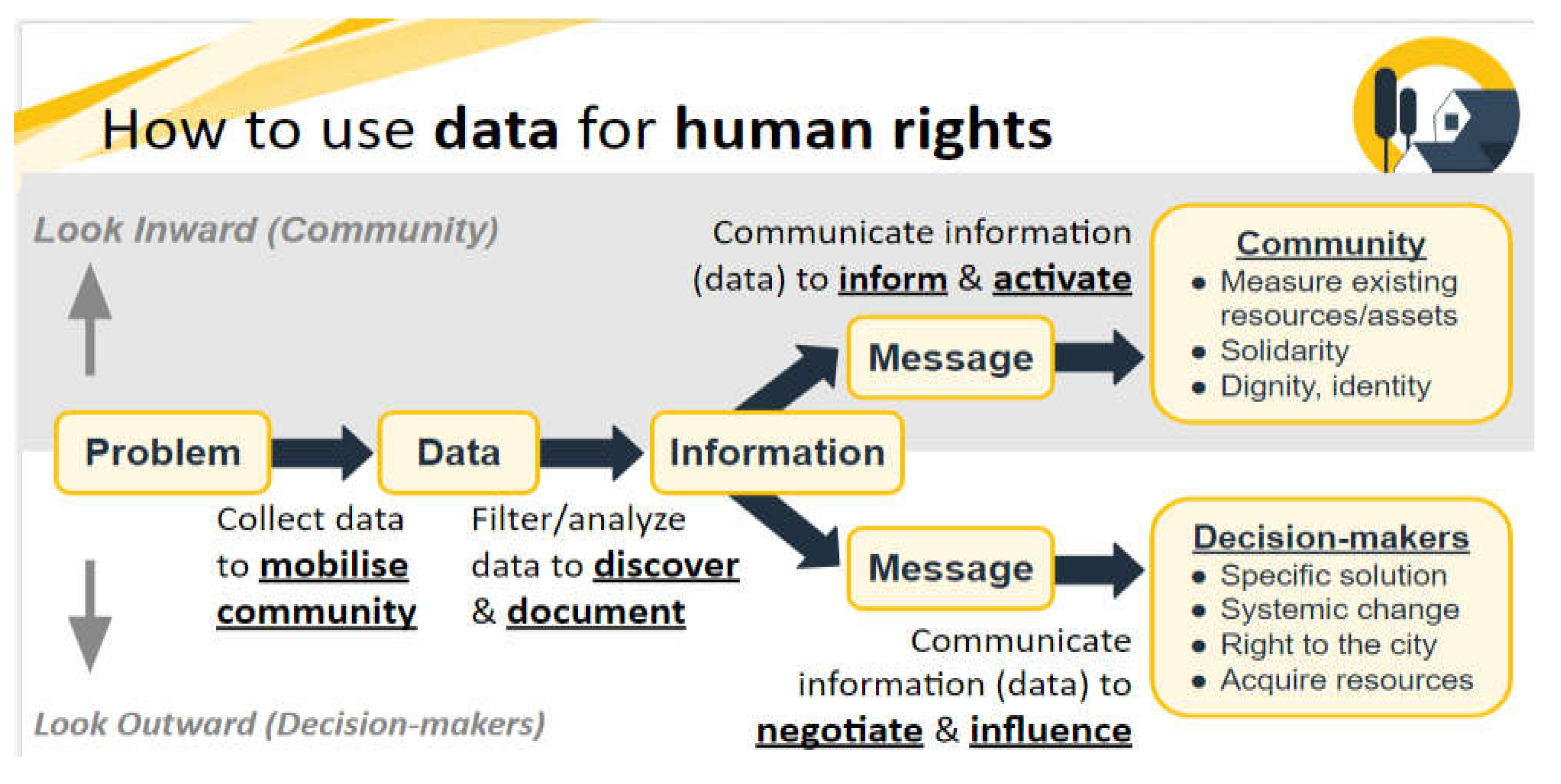

3.1. The developed Data4HumanRights training materials

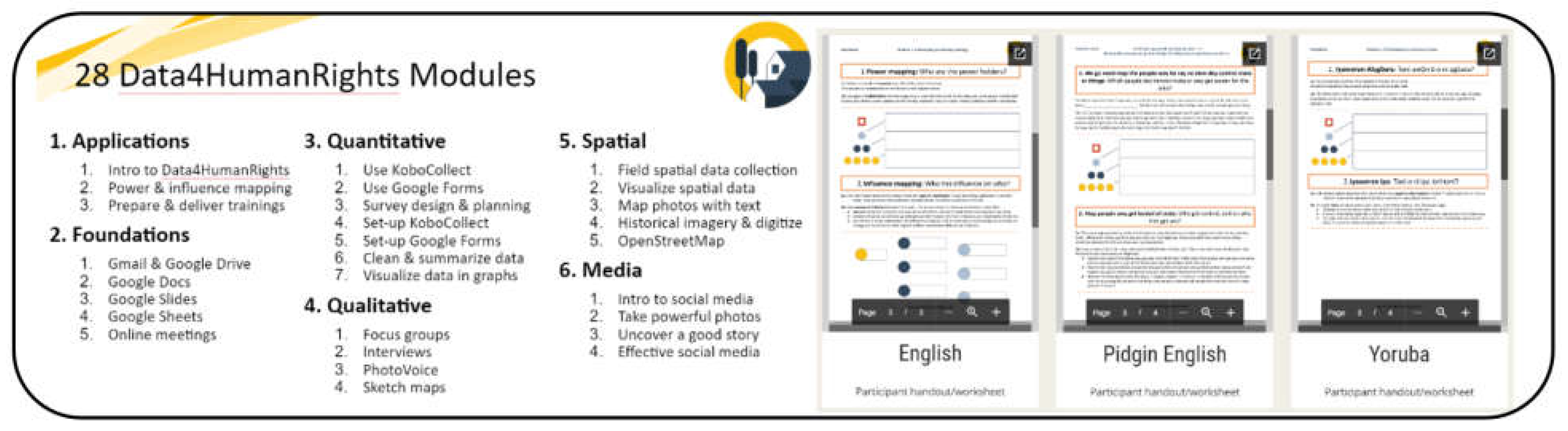

- Applications: These modules set the scene for understanding the importance of data for community building, advocacy, and campaigning for human rights. Topics include an introduction to Data for human rights, Power and influence mapping, and How to prepare and deliver community training.

- Foundations: These modules provide the basics of working with a smartphone (instead of a computer) to organize information and communication. Topics include working with Google Drive and Docs, Making presentations with Google Slides, and using Online meeting tools.

- Quantitative methods: these modules allow data collection on questions about what is happening in communities. Topics include data collection tools such as KoboCollect and Google Forms, Survey design, sampling, and planning, Survey set-up in different tools, and working with Tables and Presenting data (e.g., graphs).

- Qualitative methods: these modules allow data collection on ‘why’ questions. Topics include Focus Group Discussions, Interviews, PhotoVoice and Sketch maps and reconnaissance surveys.

- Spatial methods: these modules relate to ‘where’ questions in communities, enabling them to understand the geographic context. Topics include Field spatial data collection in QField (Mobile), Visualize data in Google Maps app (Mobile), Map photos and text in Google Maps (Computer), Historical imagery and digitize data in Google Earth (Computer), and Adding to and editing OpenStreetMap.

- Media methods: these modules support communities by communicating about advocacy and awareness campaigns. Topics include an Introduction to social media, Taking powerful photos, Uncovering a good story, and Effective social media posts.

3.2. Training of Trainers in Lagos (Nigeria)

- The sustainability of the training is supported by publishing the training materials as open-access material on our website – which allows community data collectors, CBOs, and NGOs to reuse the materials.

- Within community training in Sudan (Figure 8), the training materials have been used and were adapted and translated (Arabic) for training sessions with CBOs and NGOs: https://www.idea-maps.net/workshops/community/.

- The training materials are presently adapted by CommunityMappers (in Kenya) to fit the needs of community data collection on human rights in Kenya (https://www.communitymappers.com). This will also include a translation to Swahili.

4. Discussion

- The importance of co-designing the material with community leaders and activists. The material had several rounds of review and improvements – to simplify the material and adapt it to situations where no computers and projectors were available.

- The training material has been split into different levels – basic training units and advanced training units to enable suitability for different contexts, as well as deeper learning for those interested/able.

- The training material has been translated into local languages – handouts for running community training in communities without access to computers and projectors.

- Publishing of all 28 training units as open-access material on our website. All groups with interest can pick up the materials and adapt the training to local needs.

- Outreach to related projects in Nigeria, Kenya, and Sudan. This supported the uptake of training materials for ongoing work in other communities.

- Network of community co-researchers who can support research on communities. Within the training, we stressed the importance of co-researchers from communities. The expected impact is to increase the recognition of the importance of working with co-researchers (for the academia) and to generate livelihood opportunities for community data collectors.

- The importance of developing materials that do not rely on computers but are built on the use of smartphones, which are commonly available in communities and easily allow replicating the training.

- The importance of supporting female leaders, developing role models of female leadership, and finding innovative solutions for female trainers to overcome challenges (e.g., the commonly softer voices by using amplification methods).

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Patel, S., C. Baptist and C. D'Cruz. "Knowledge is power - informal communities assert their right to the city through SDI and community-led enumerations." Environment and Urbanization 24 (2012): 13-26. [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, A., B. Wilson, S. Sarraf and A. Jana. "Open data for informal settlements: Toward a user׳s guide for urban managers and planners." Journal of Urban Management 4 (2015): 74-91. [CrossRef]

- Oluoch, I., M. Kuffer and M. Nagenborg. "In-Between the Lines and Pixels: Cartography’s Transition from Tool of the State to Humanitarian Mapping of Deprived Urban Areas." Digital Society 1 (2022): 5. [CrossRef]

- Abascal, A., N. Rothwell, A. Shonowo, D. R. Thomson, P. Elias, H. Elsey, G. Yeboah and M. Kuffer. "“Domains of deprivation framework” for mapping slums, informal settlements, and other deprived areas in LMICs to improve urban planning and policy: A scoping review." Computers, Environment and Urban Systems 93 (2022): 101770. [CrossRef]

- Wanjiru, N. Community Voices #1: Waste Management Solutions. Vice Versa: 2021.

- Gulyani, S., E. M. Bassett and D. Talukdar. "A tale of two cities: A multi-dimensional portrait of poverty and living conditions in the slums of Dakar and Nairobi." Habitat International 43 (2014): 98-107. [CrossRef]

- Zanoni, W., P. Acevedo and D. A. Guerrero. "Do slum upgrading programs impact school attendance?" Economics of Education Review 96 (2023): 102458. [CrossRef]

- Kuffer, M., J. Wang, D. R. Thomson, S. Georganos, A. Abascal, M. Owusu and S. Vanhuysse. "Spatial Information Gaps on Deprived Urban Areas (Slums) in Low-and-Middle-Income-Countries: A User-Centered Approach." Urban Science 5 (2021): 72. [CrossRef]

- SDI. Strategic Plan 2018 – 2022. Cape Town, South Africa: 2018.

- Thomson, D. R., M. Kuffer, G. Boo, B. Hati, T. Grippa, H. Elsey, C. Linard, R. Mahabir, C. Kyobutungi, J. Maviti, et al. "Need for an Integrated Deprived Area “Slum” Mapping System (IDEAMAPS) in Low- and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs)." Social Sciences 9 (2020): 80.

- Beukes, A. and D. Mitlin. Know your city: Community profiling of informal settlements. International Institute for Environment and Development., 2014.

- Patel, S. and C. Baptist. "Editorial: Documenting by the undocumented." Environ. Urban. 24 (2012): 3-12. [CrossRef]

- Merodio Gómez, P., O. J. Juarez Carrillo, M. Kuffer, D. R. Thomson, J. L. Olarte Quiroz, E. Villaseñor García, S. Vanhuysse, Á. Abascal, I. Oluoch, M. Nagenborg, et al. "Earth Observations and Statistics: Unlocking Sociodemographic Knowledge through the Power of Satellite Images." Sustainability 13 (2021): 12640. [CrossRef]

- IdeaMapsNetwork. Community Mappers identify and respond to needs in informal settlements during COVID-19. 2020.

- de Albuquerque, J. P., G. Yeboah, V. Pitidis and P. Ulbrich. "Towards a participatory methodology for community data generation to analyse urban health inequalities : a multi-country case study. In " Presented at Proceedings of the 52nd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, 2019. 3926-25. [CrossRef]

- UN-Habitat. Human rights in cities handbook series–The human rights-based approach to housing and slum upgrading. UN-Habitat, 2017.

- Oloko, A., K. Fakoya, S. Ferse, A. Breckwoldt and S. Harper. "The Challenges and Prospects of Women Fisherfolk in Makoko, Lagos State, Nigeria." Coastal Management 50 (2022): 124-41. [CrossRef]

- Dobson, S. "Community-driven pathways for implementation of global urban resilience goals in Africa." International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 26 (2017): 78-84. [CrossRef]

- Corburn, J., D. Vlahov, B. Mberu, L. Riley, W. T. Caiaffa, S. F. Rashid, A. Ko, S. Patel, S. Jukur, E. Martínez-Herrera, et al. "Slum Health: Arresting COVID-19 and Improving Well-Being in Urban Informal Settlements." Journal of Urban Health (2020). [CrossRef]

- Amnesty International. Key Principles And Approaches For Capacity Building In Amnesty International. 2008.

- Hopkins, K. "Amnesty International's Methods of Engaging Youth in Human Rights Education: Curriculum in the United States and Experiential Learning in Burkina Faso." Journal of Human Rights Practice 3 (2011): 71-92. [CrossRef]

- Kuffer, M., I. M. M. Ali, A. Gummah, A. D. S. Mano, W. Sakhi, I. Kushieb, S. Girgin, N. Eltiny, J. Kumi, M. Abdallah, et al. "IDeaMapSudan: Geo-Spatial Modelling of Urban Poverty." Presented at 2023 Joint Urban Remote Sensing Event (JURSE), 2023. 1-4. [CrossRef]

- Adebayo, B. "Thousands of Nigerian slum dwellers left homeless after mass eviction." CNN 2020. https://edition.cnn.com/2020/01/22/africa/nigeria-tarkwa-bay-evictions-intl/index.html.

- HotOSM. "Learn OSM: English Learning Guides." 2017. https://github.com/hotosm/learnosm/wiki/English-Learning-Guides/.

- Haridarshan, P. "Voices of Women within the Devanga Community, Bangalore, India." Education Sciences 11 (2021): 547.

- Kouladoum, J.-C. "Digital infrastructural development and inclusive growth in Sub-Saharan Africa." Journal of Social and Economic Development 25 (2023): 403-27. [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Access to electricity (% of population), retrieve from http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/EG.ELC.ACCS.ZS. 2020.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).