Submitted:

07 April 2024

Posted:

08 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- (1)

- water content in the combined organic solvent on the deacidification process and the quality of the raffinate streams (deacidified BO);

- (2)

- content of carboxylic acids in the feed (bio-oil) on the deacidification process and the quality of the raffinate streams;

- (3)

- temperature on the deacidification process and the quality of the raffinate streams;

- (4)

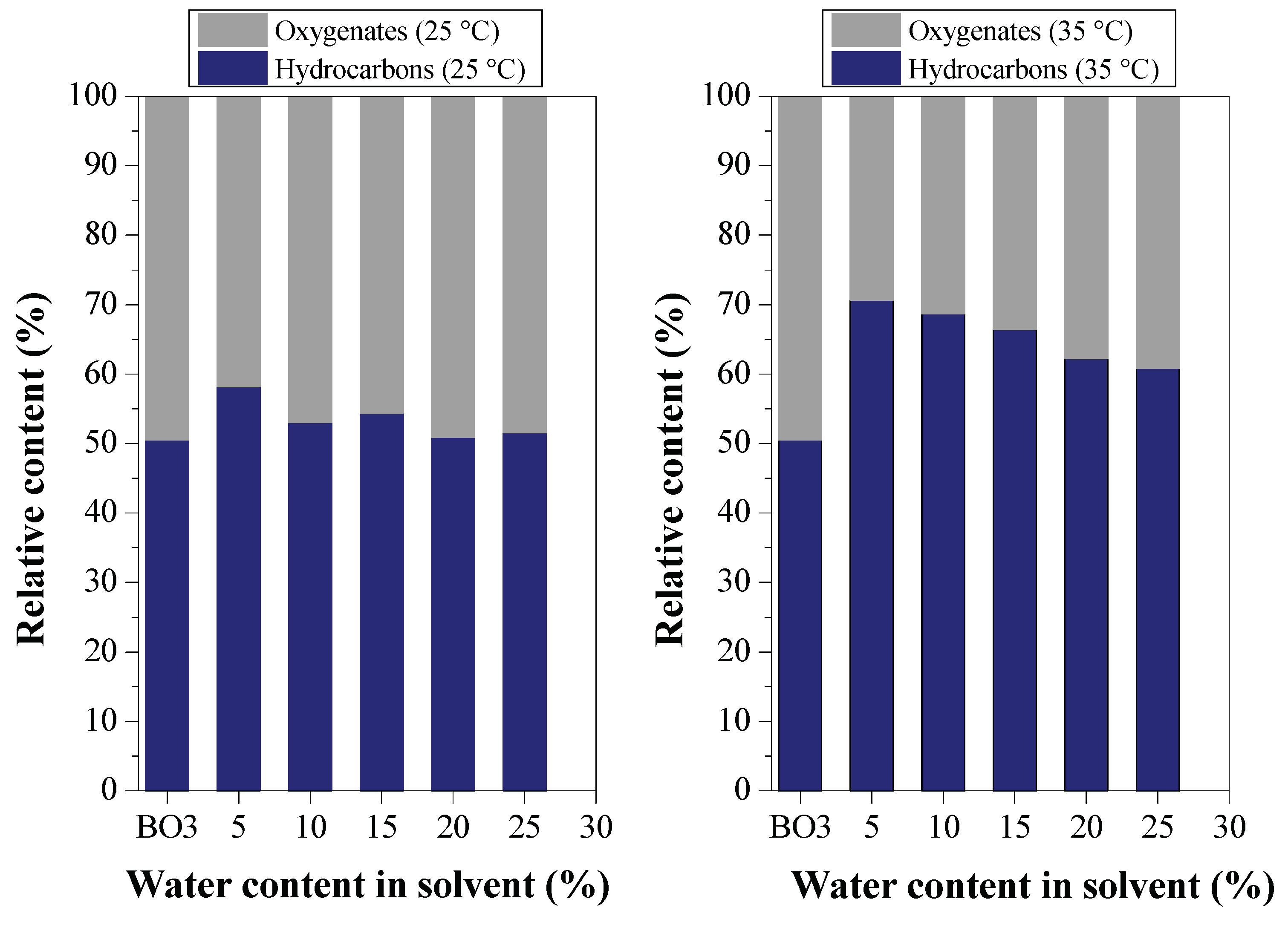

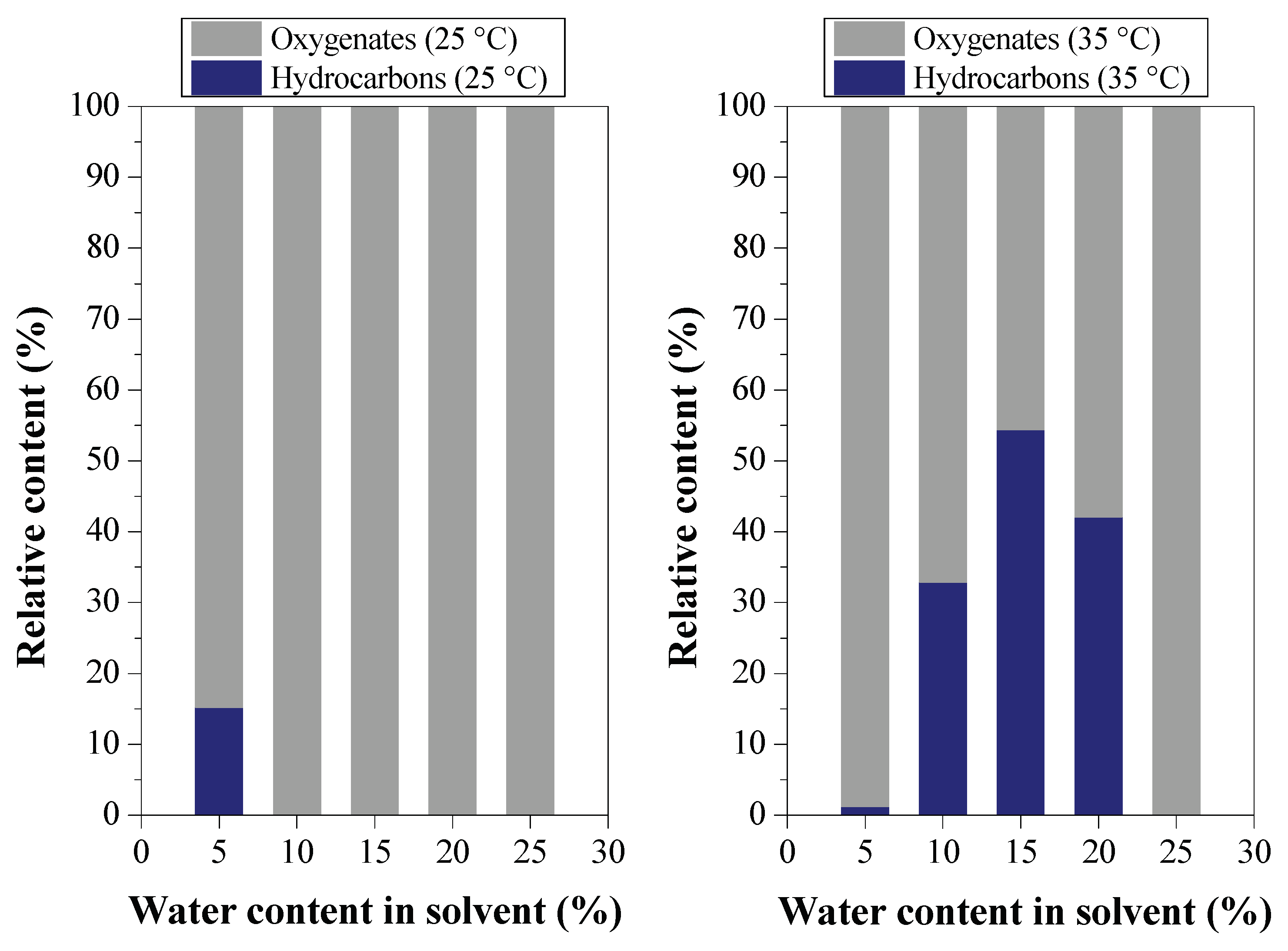

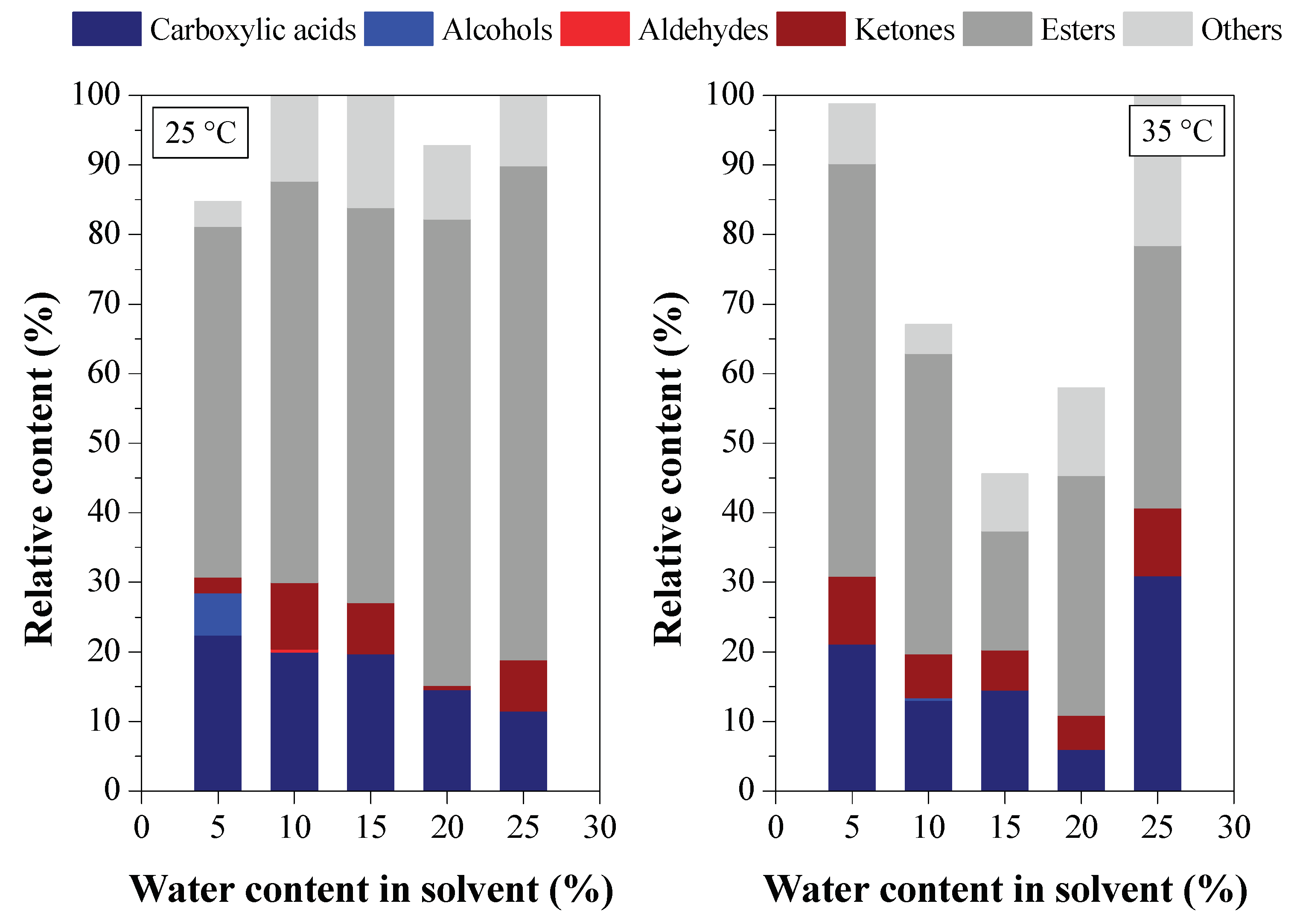

- water content in the solvents on the distribution of hydrocarbons versus the distribution of oxygenated compounds in both the raffinate and the extract;

- (5)

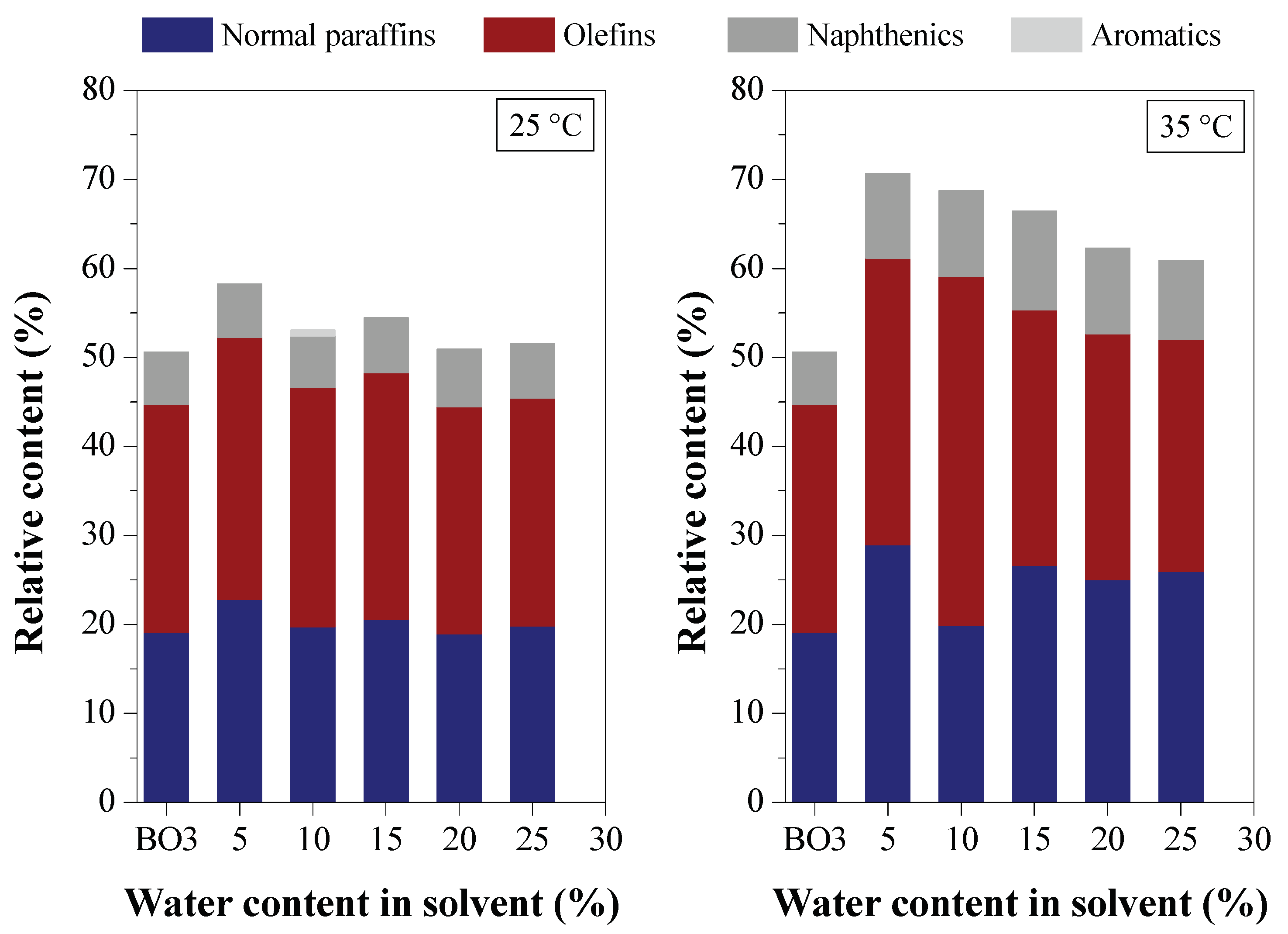

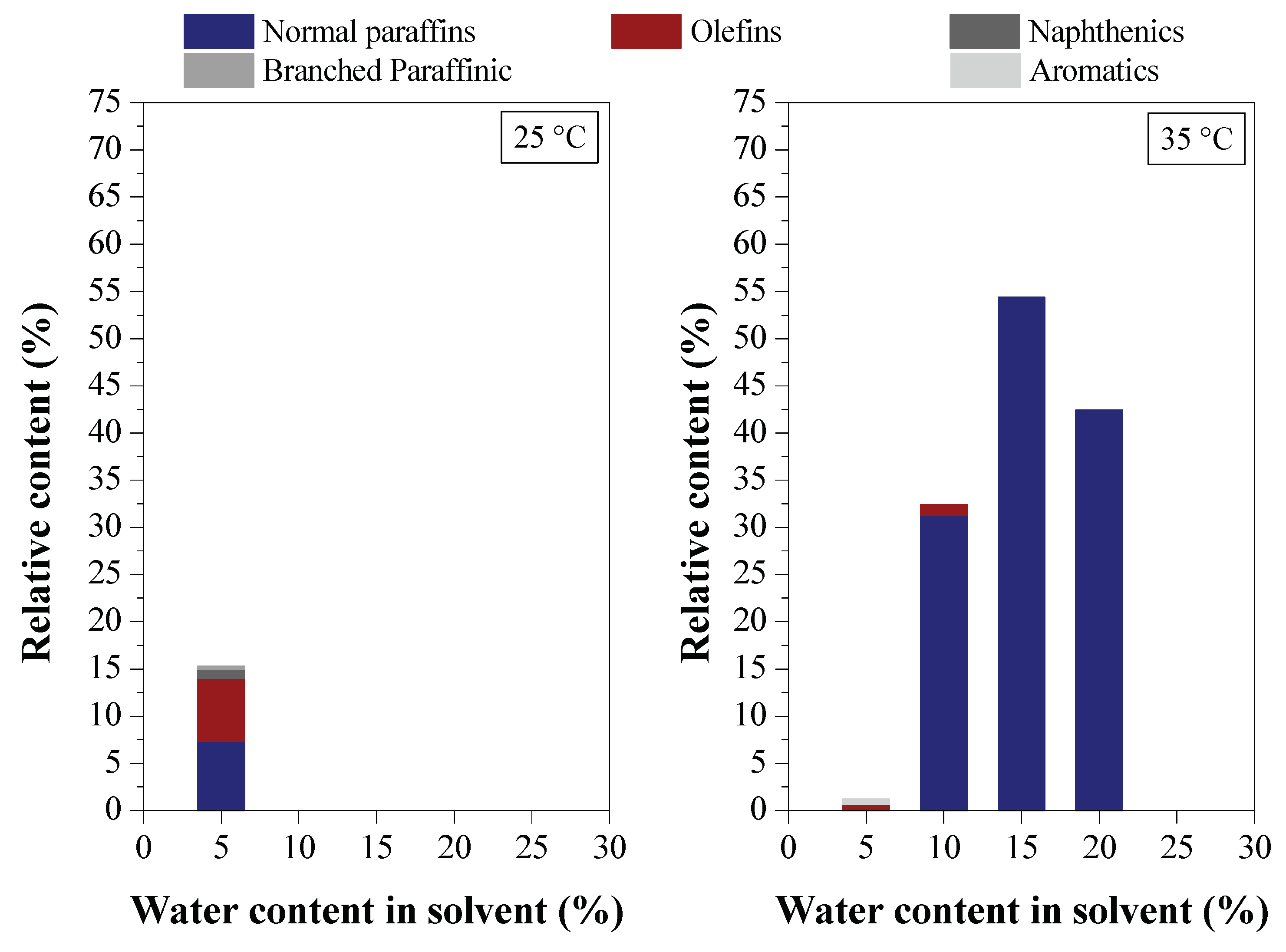

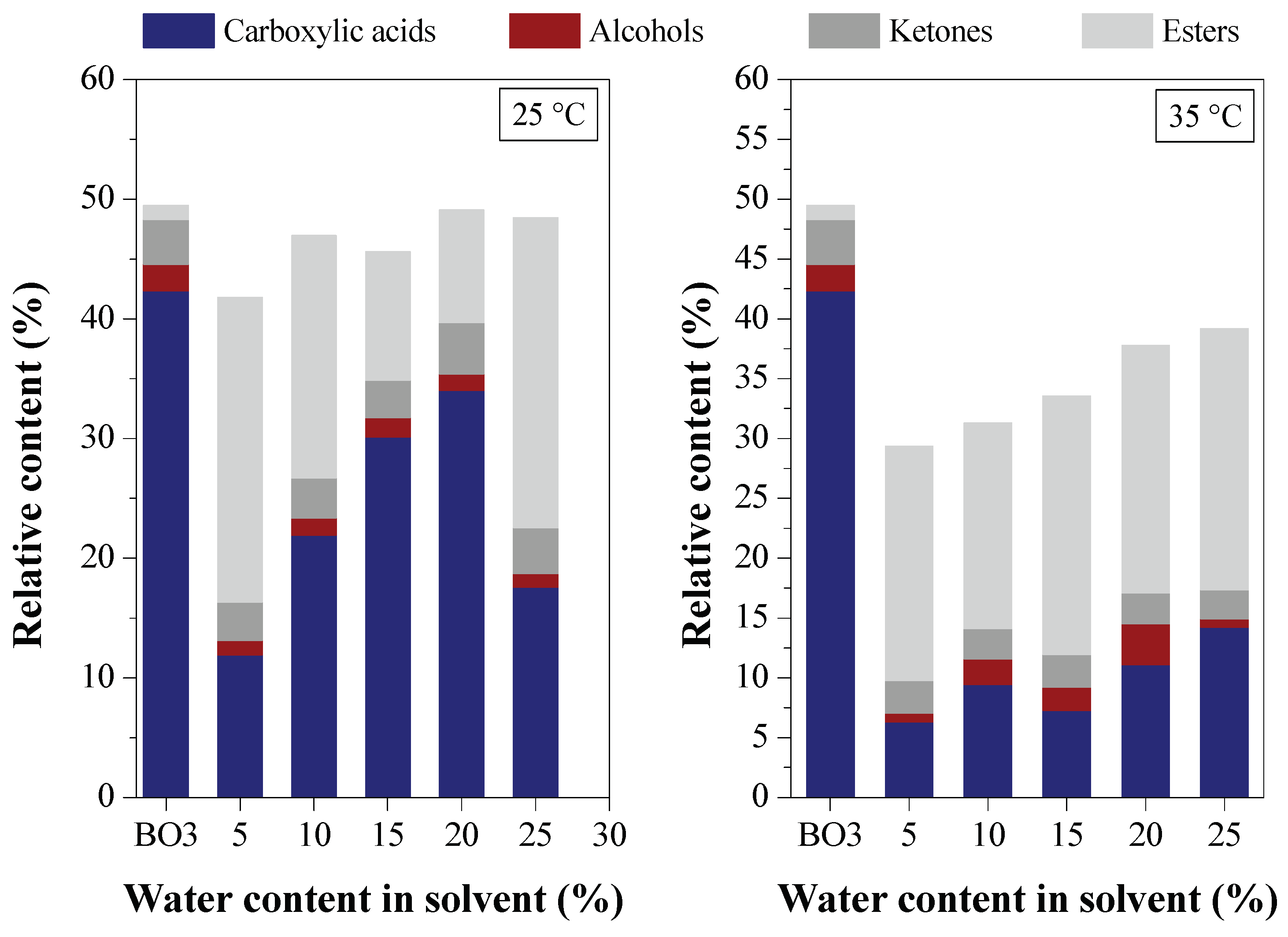

- water content in the solvents on the distribution of the classes of oxygenated compounds in both the raffinate and the extract;

- (6)

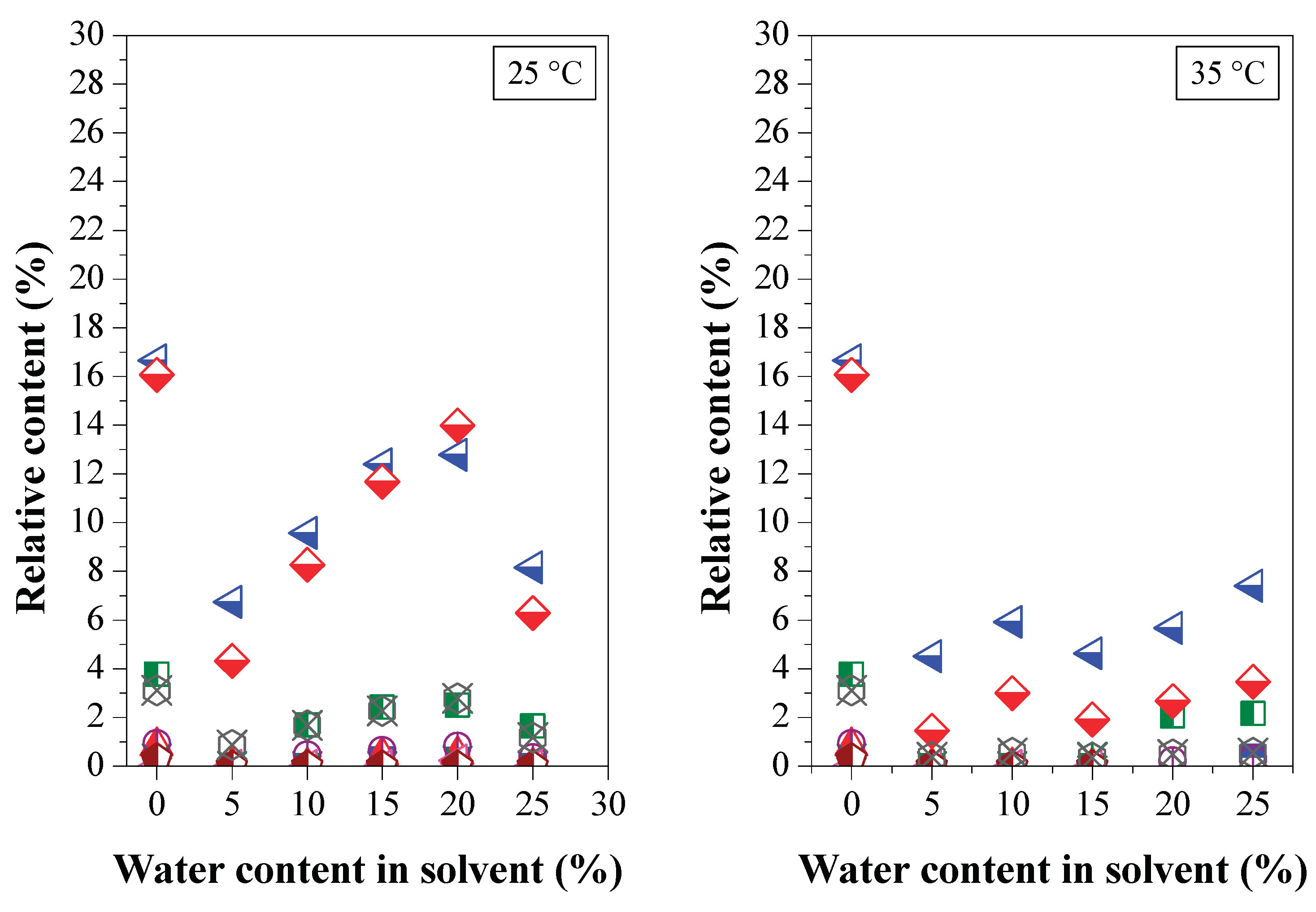

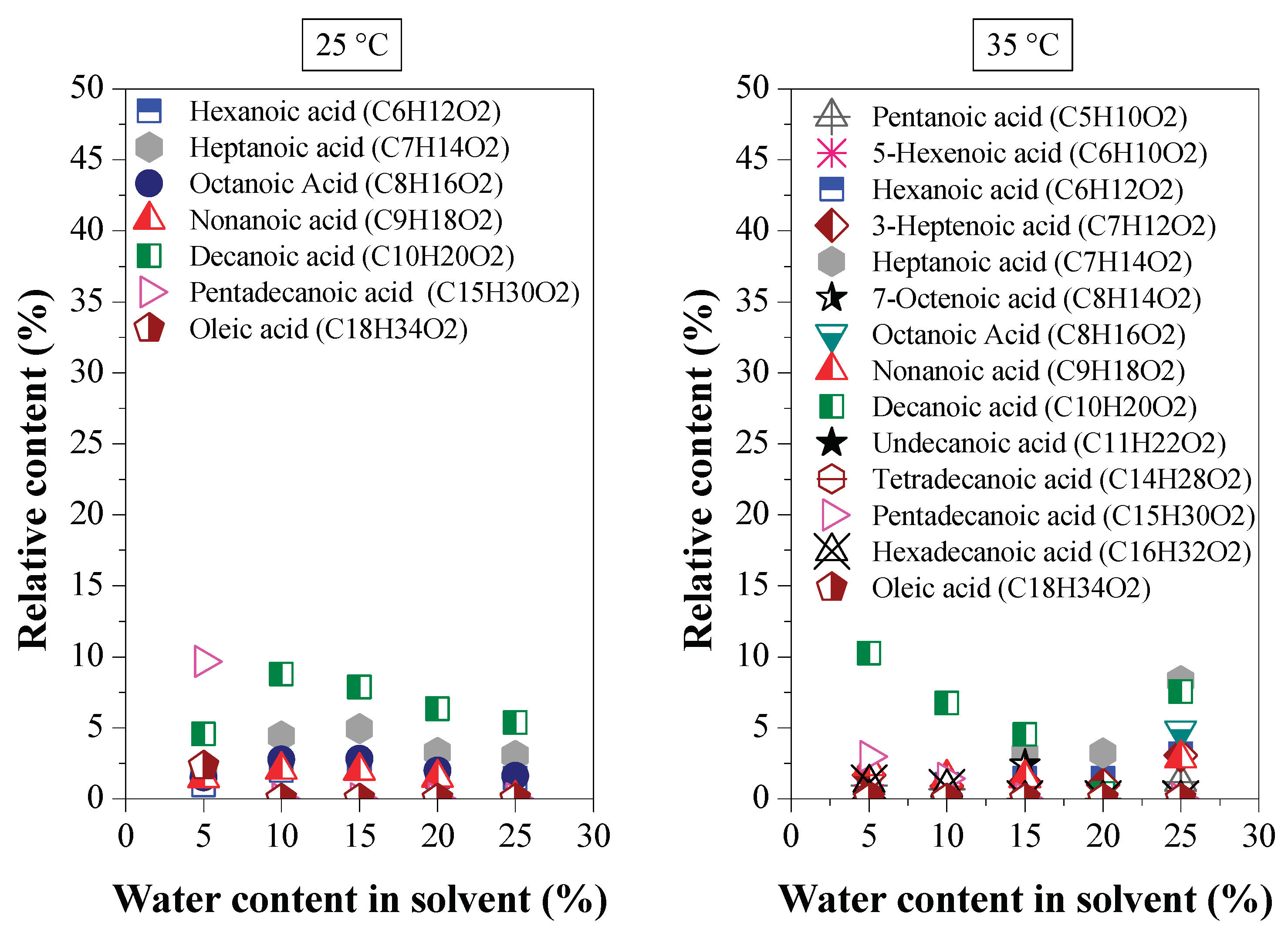

- water content in the solvents in the distribution of free fatty acids in both raffinate and extract.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Preliminary Tests

2.3. Experimental Procedure

2.3.1. Deacidification of BOs by LLE (Group of Experiments I)

2.3.2. Deacidification of BOs by LLE (Group of Experiments II)

2.4. Analytical Methods

2.4.1. Physical-Chemical Analysis

2.4.2. FTIR Analysis

2.4.3. Chemical Derivatization

2.4.4. GC-MS Analysis

2.5. Determination of LLE Process Parameters

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Deacidification of BOs by LLE (Experiment Group I)

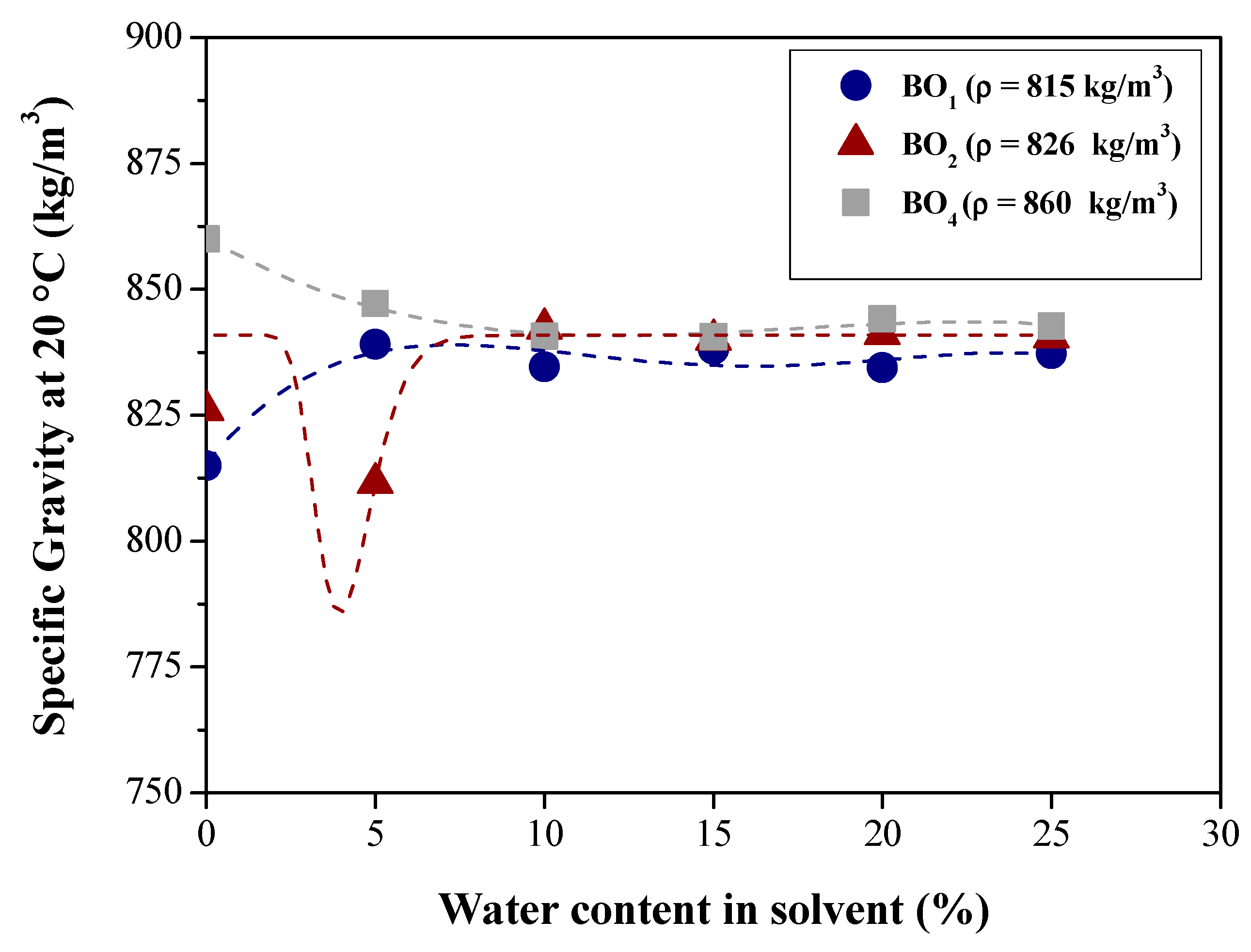

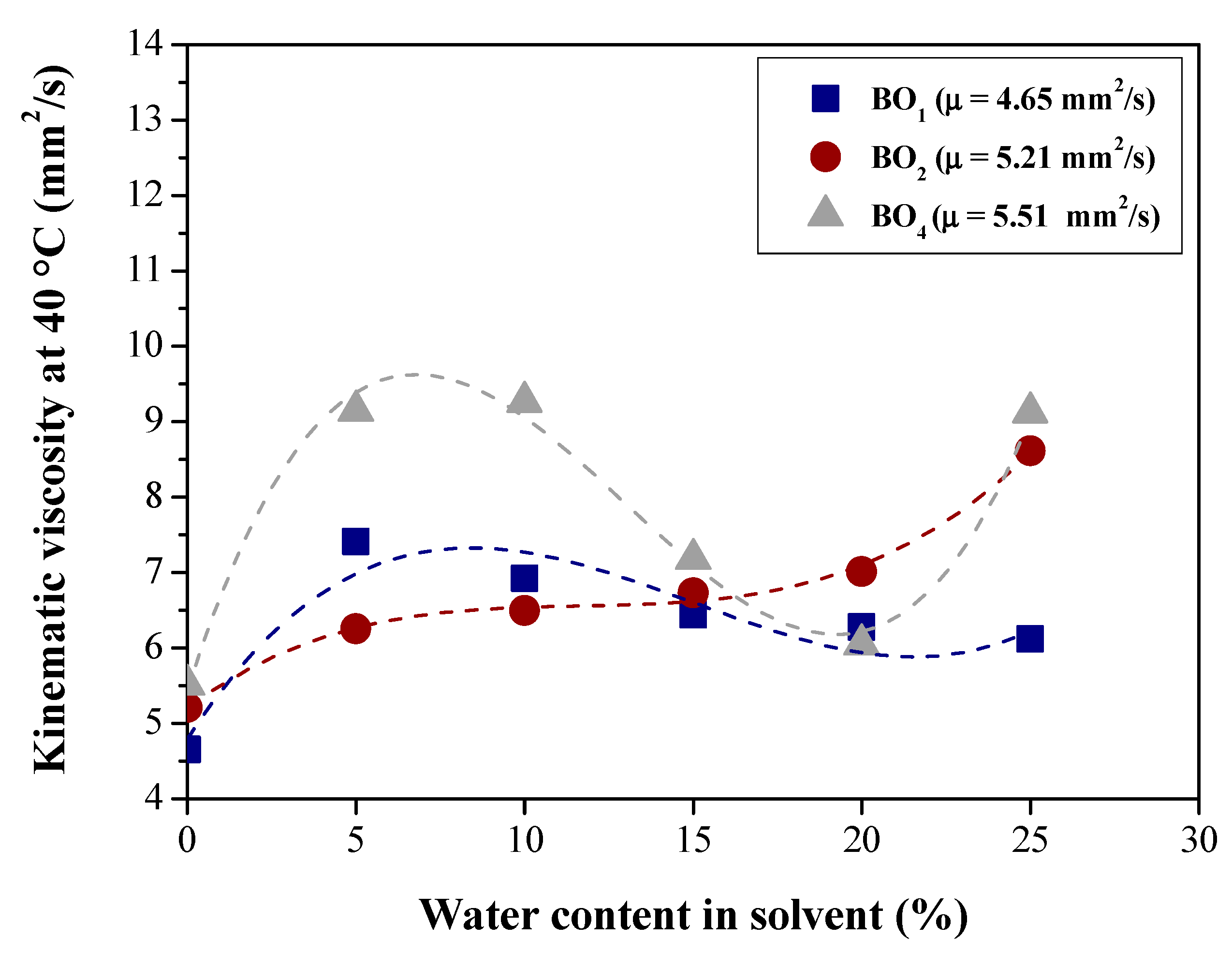

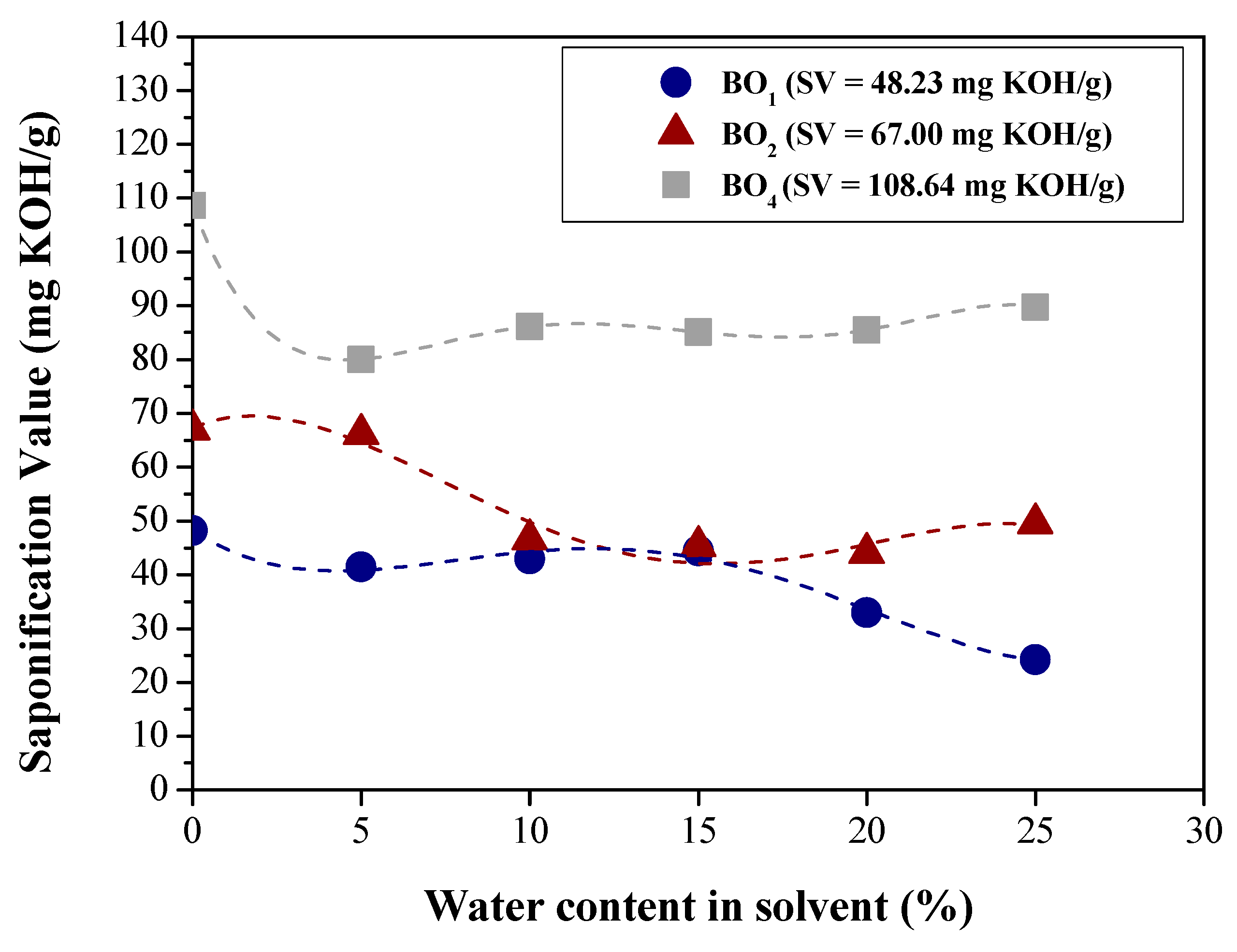

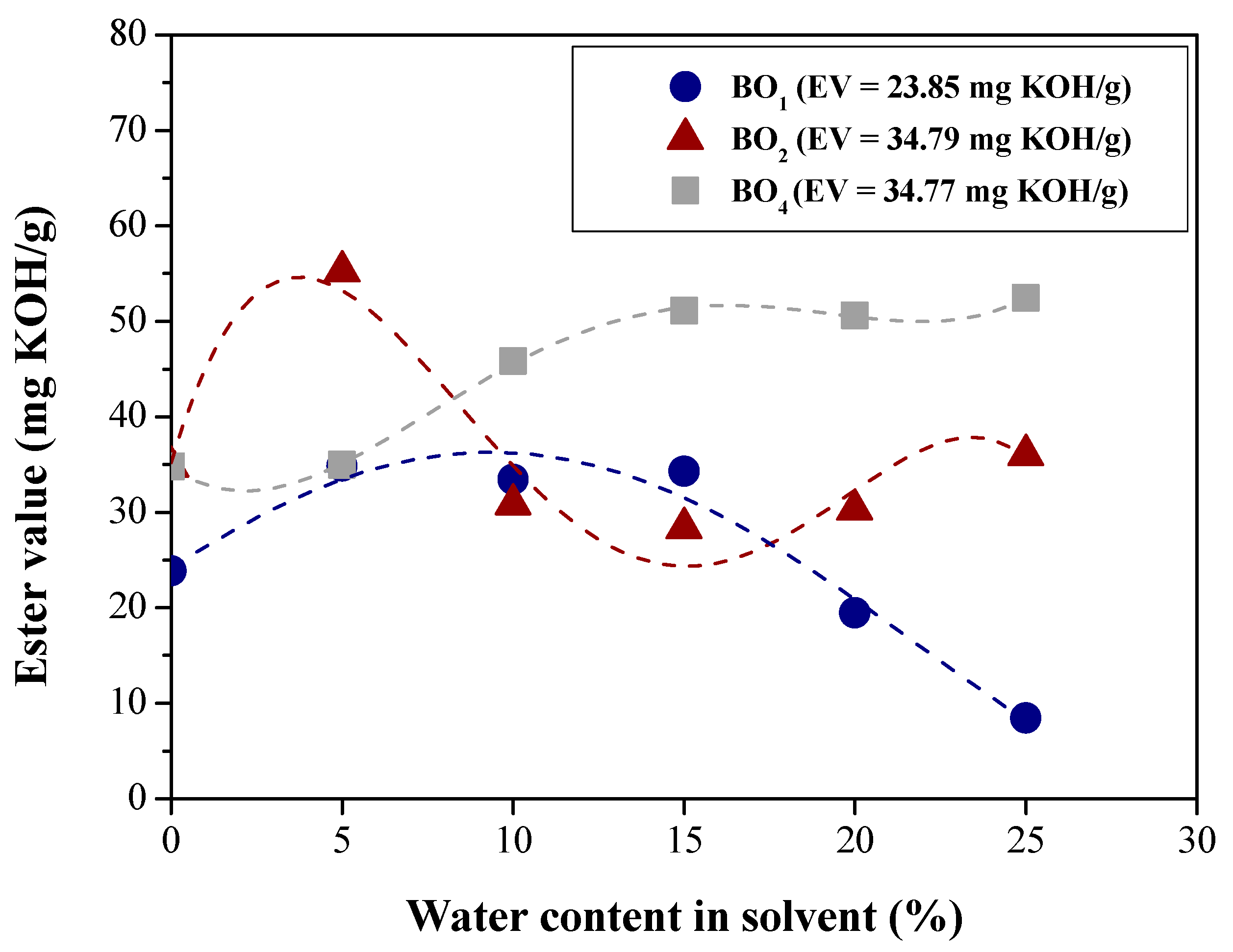

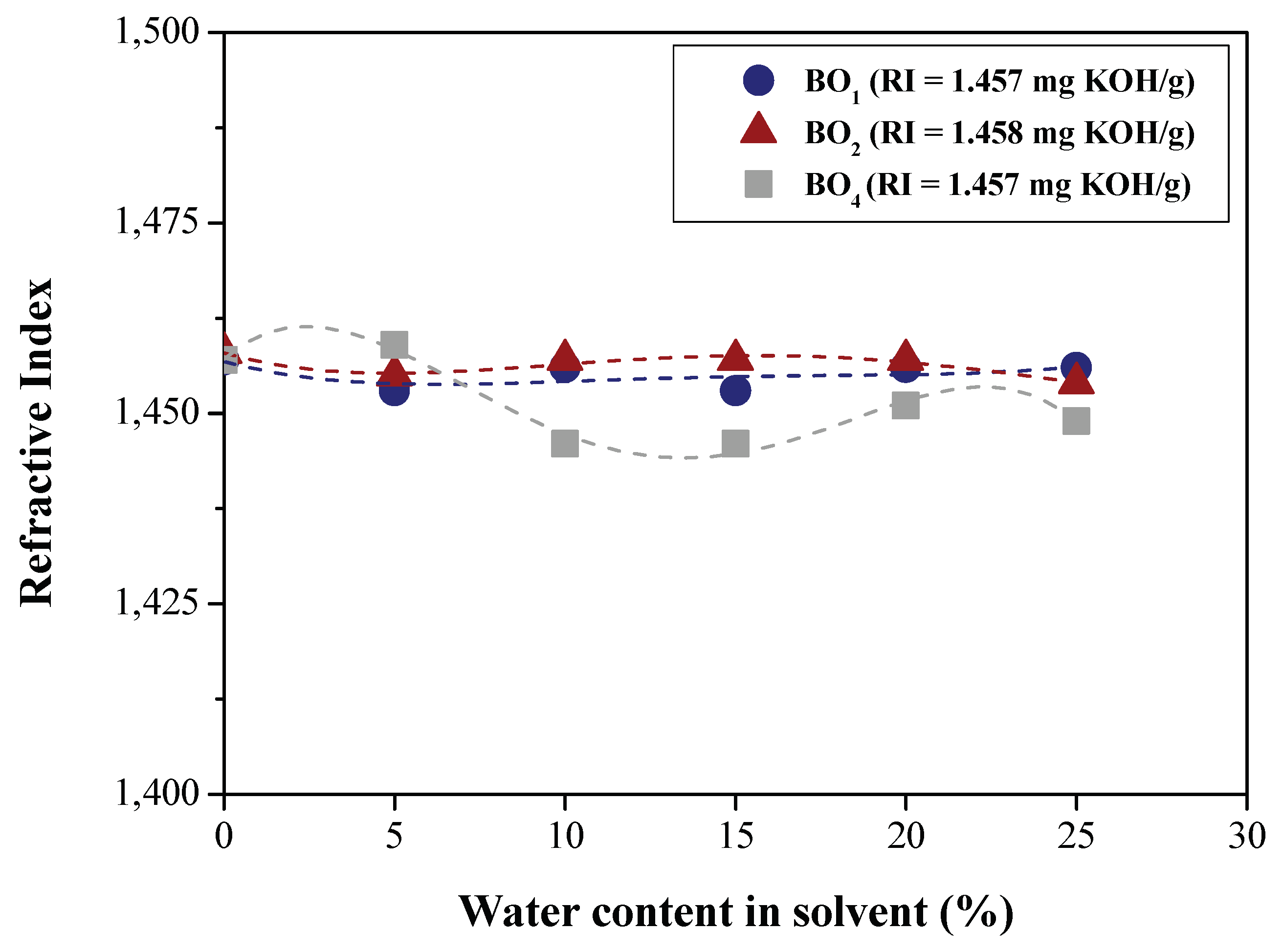

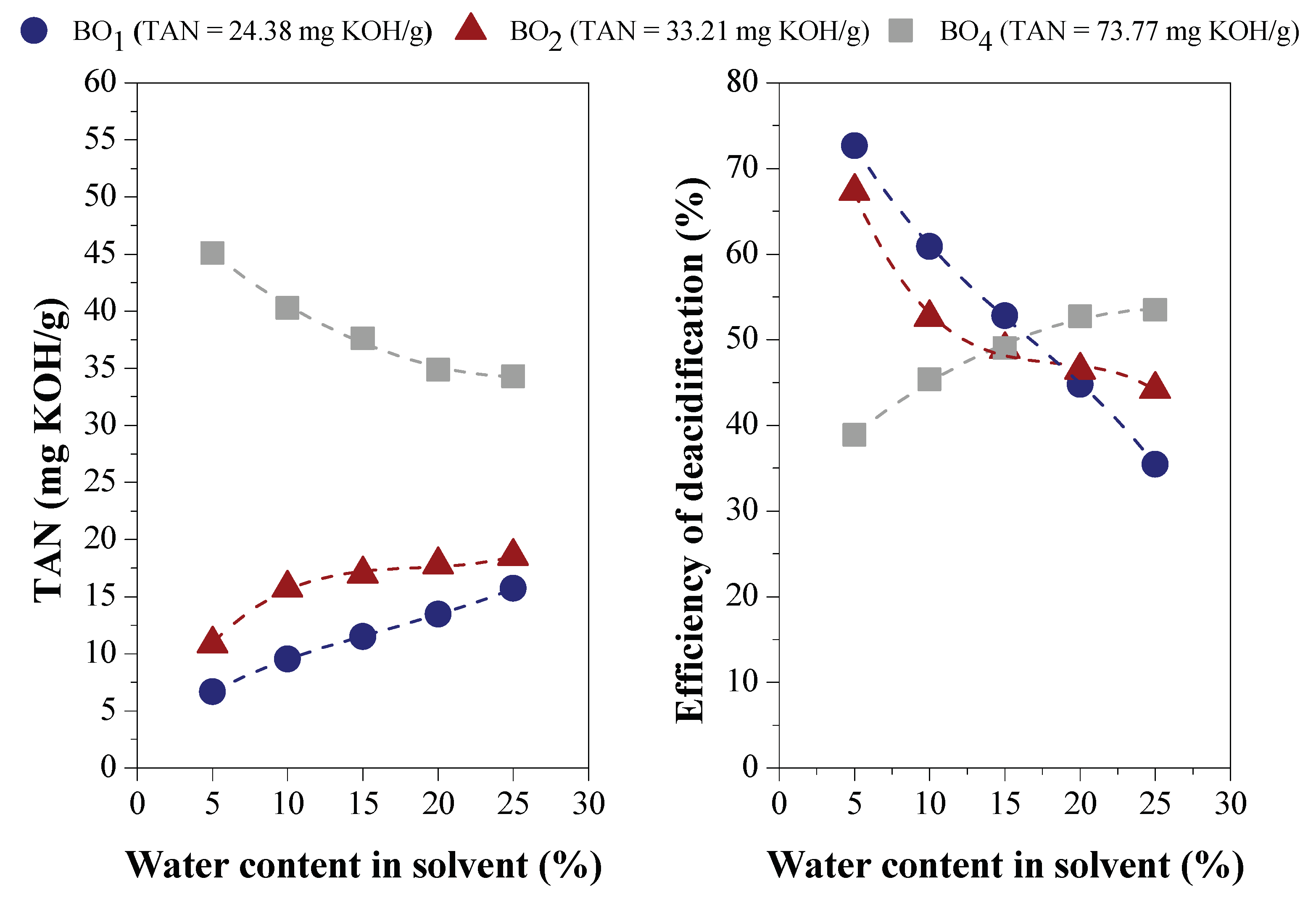

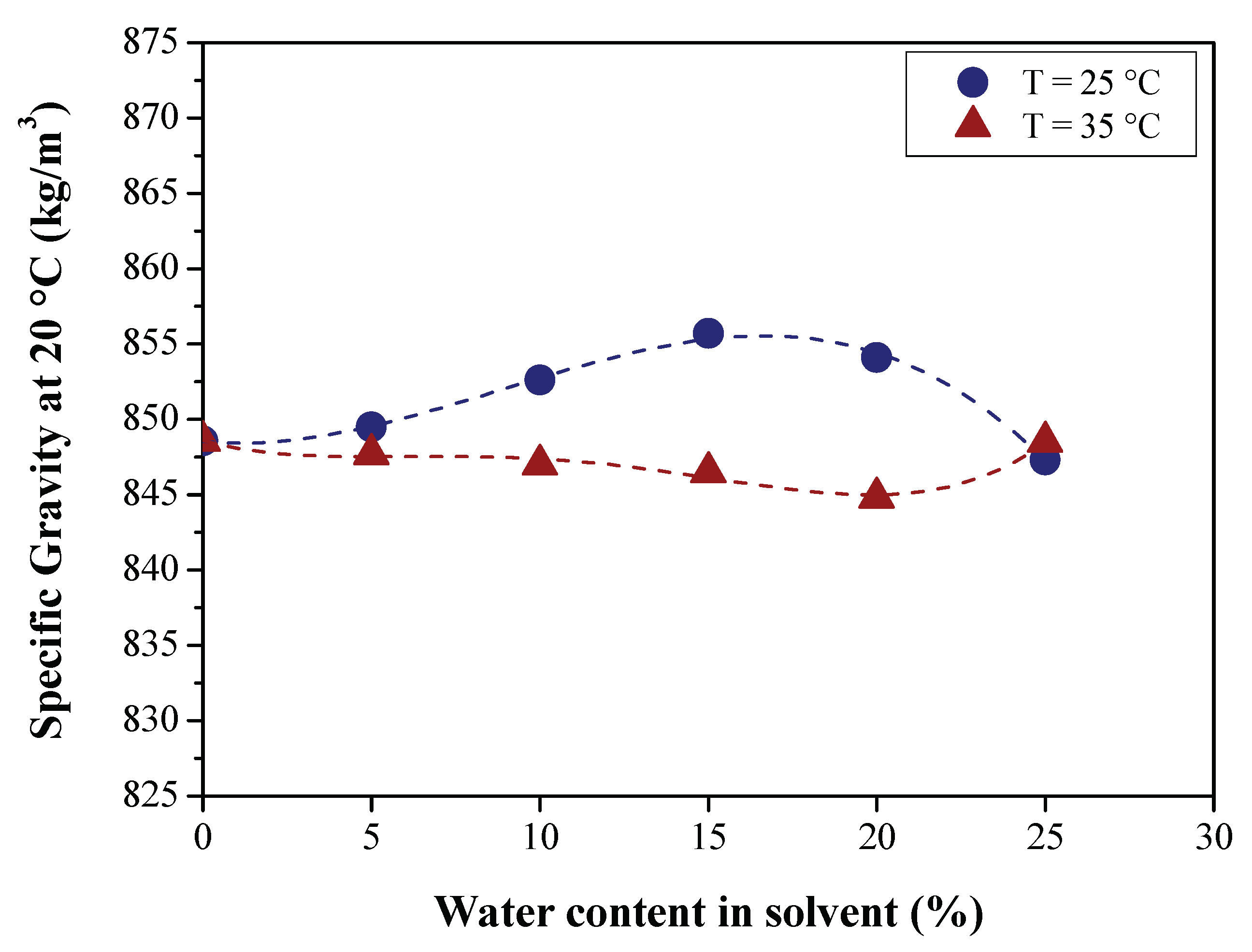

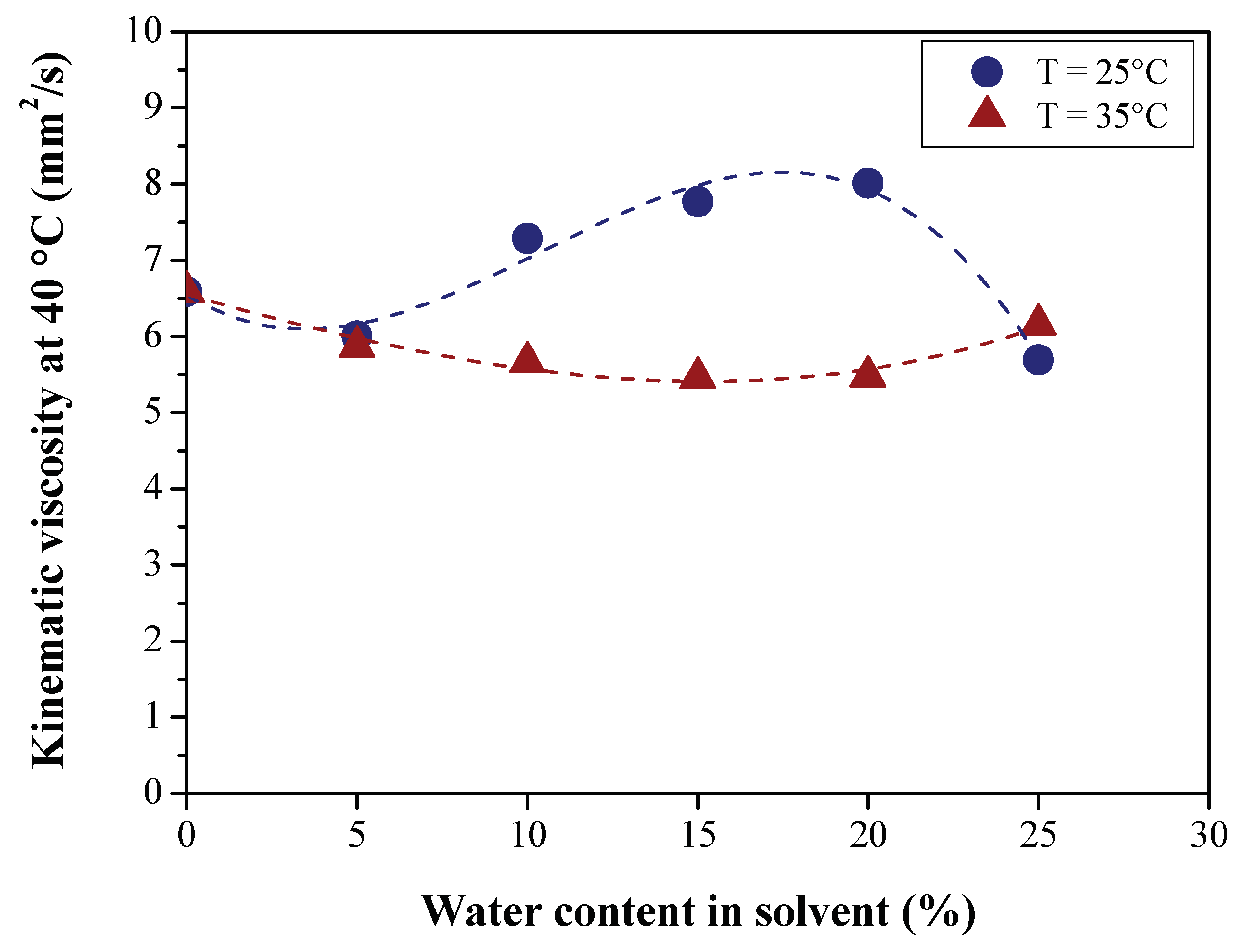

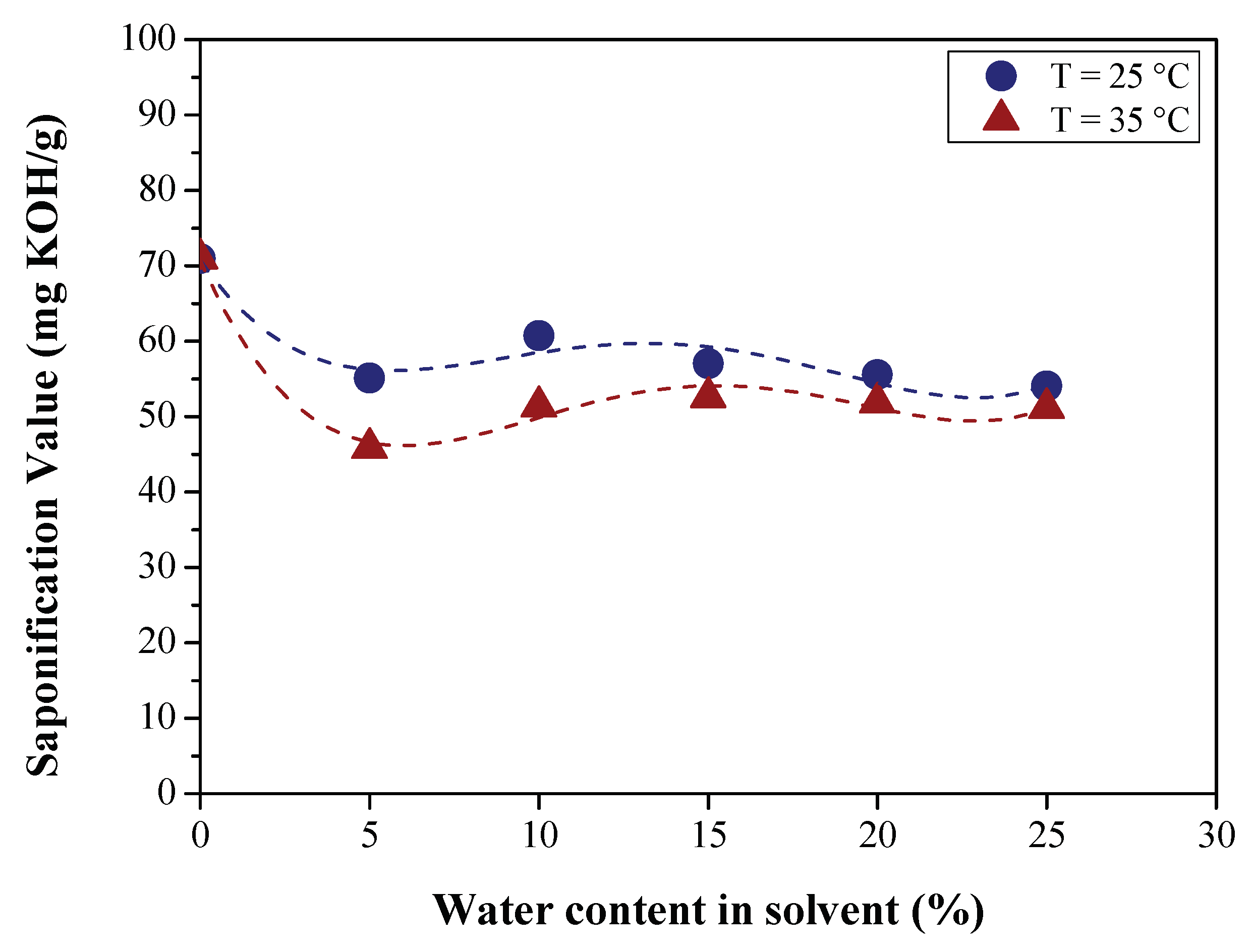

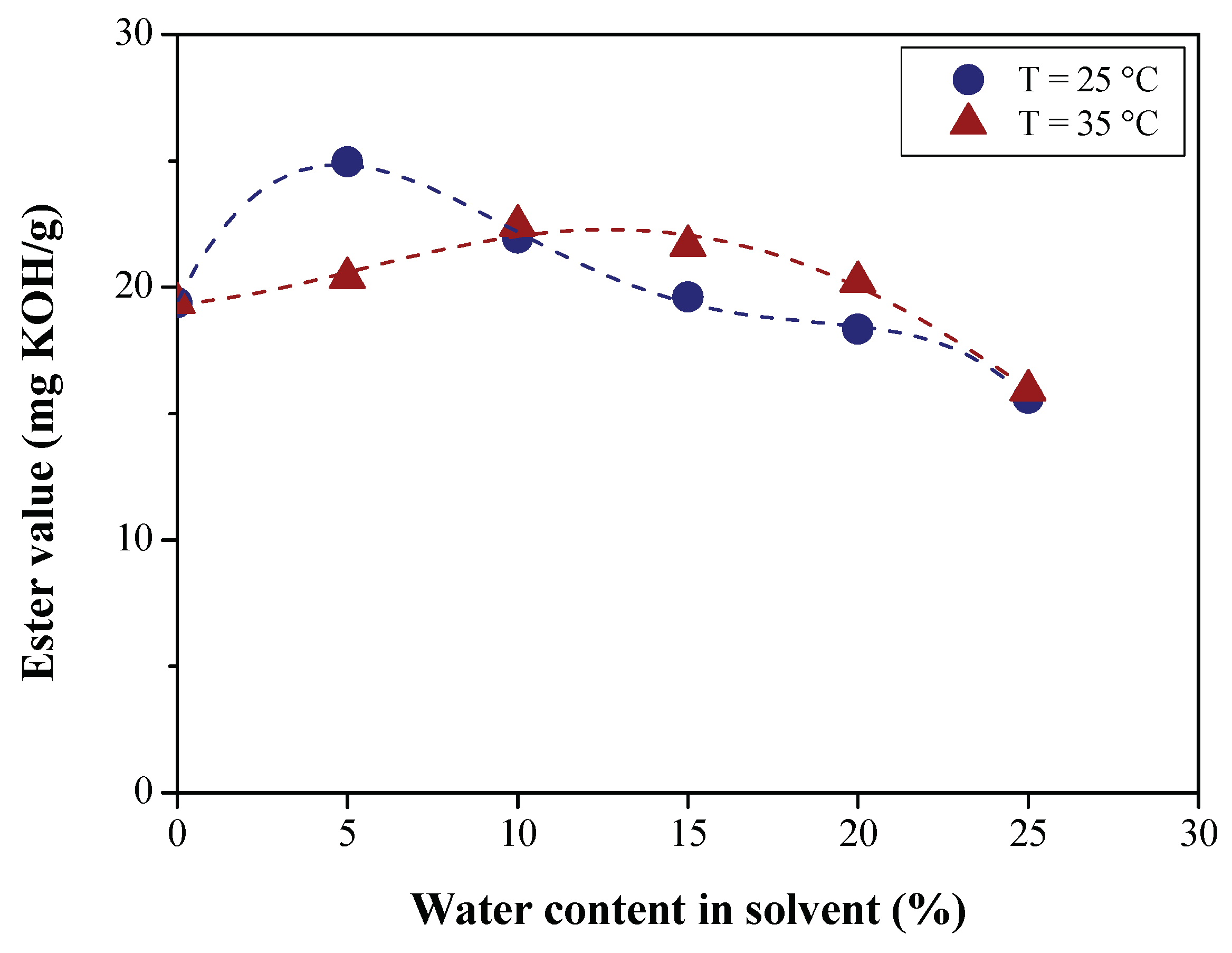

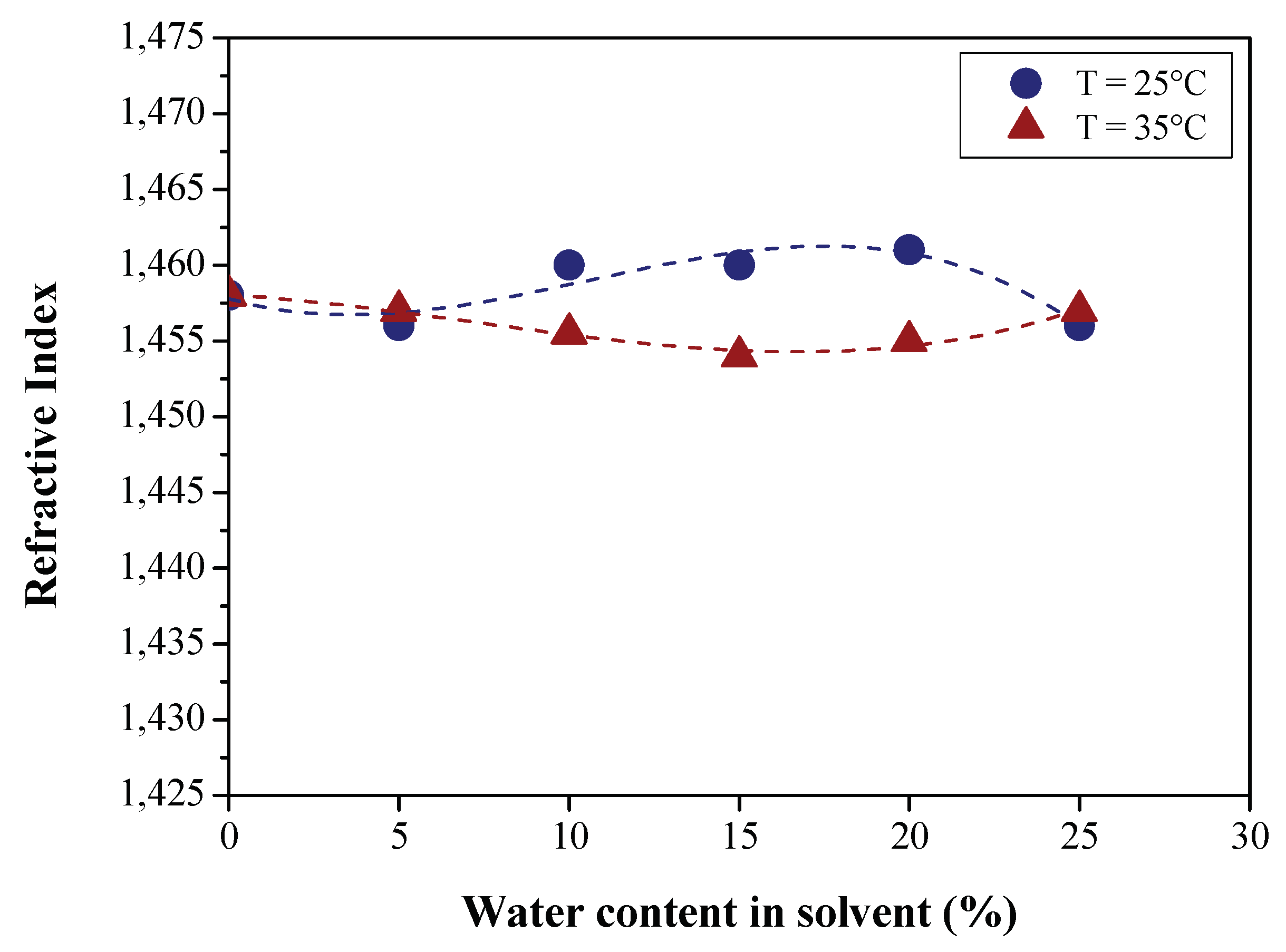

3.1.1. Effect of BO Deacidification by LLE on the Quality of Raffinates

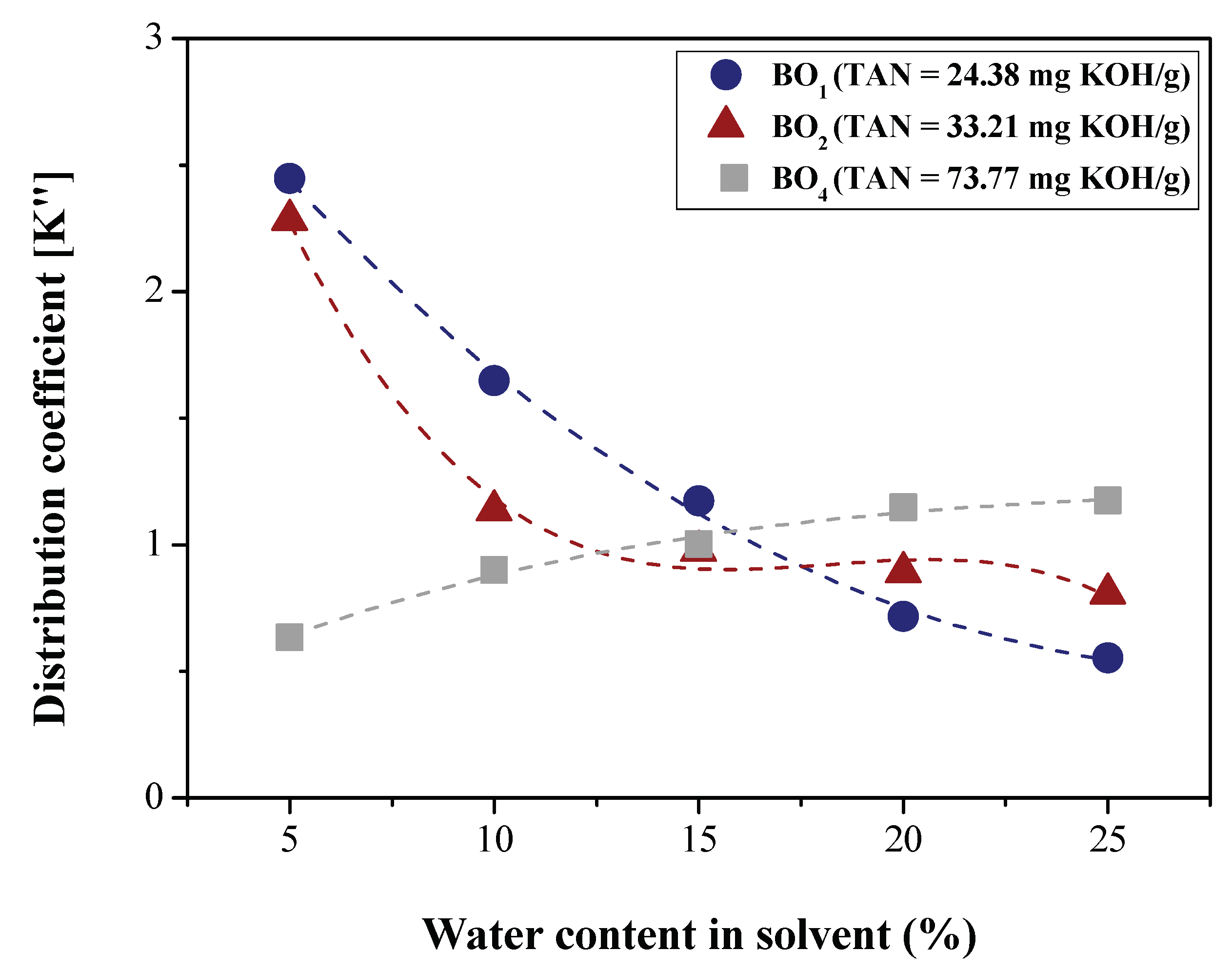

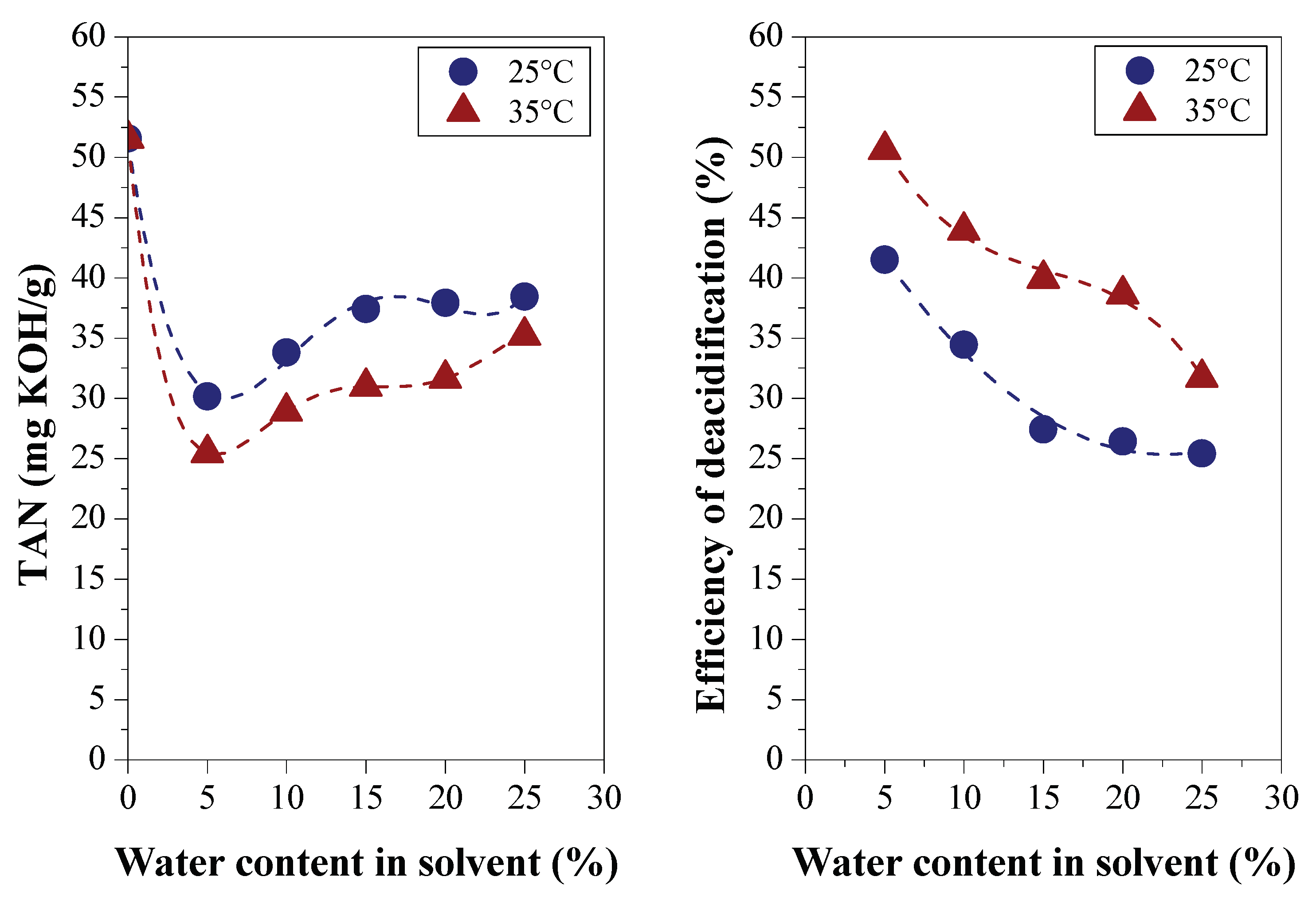

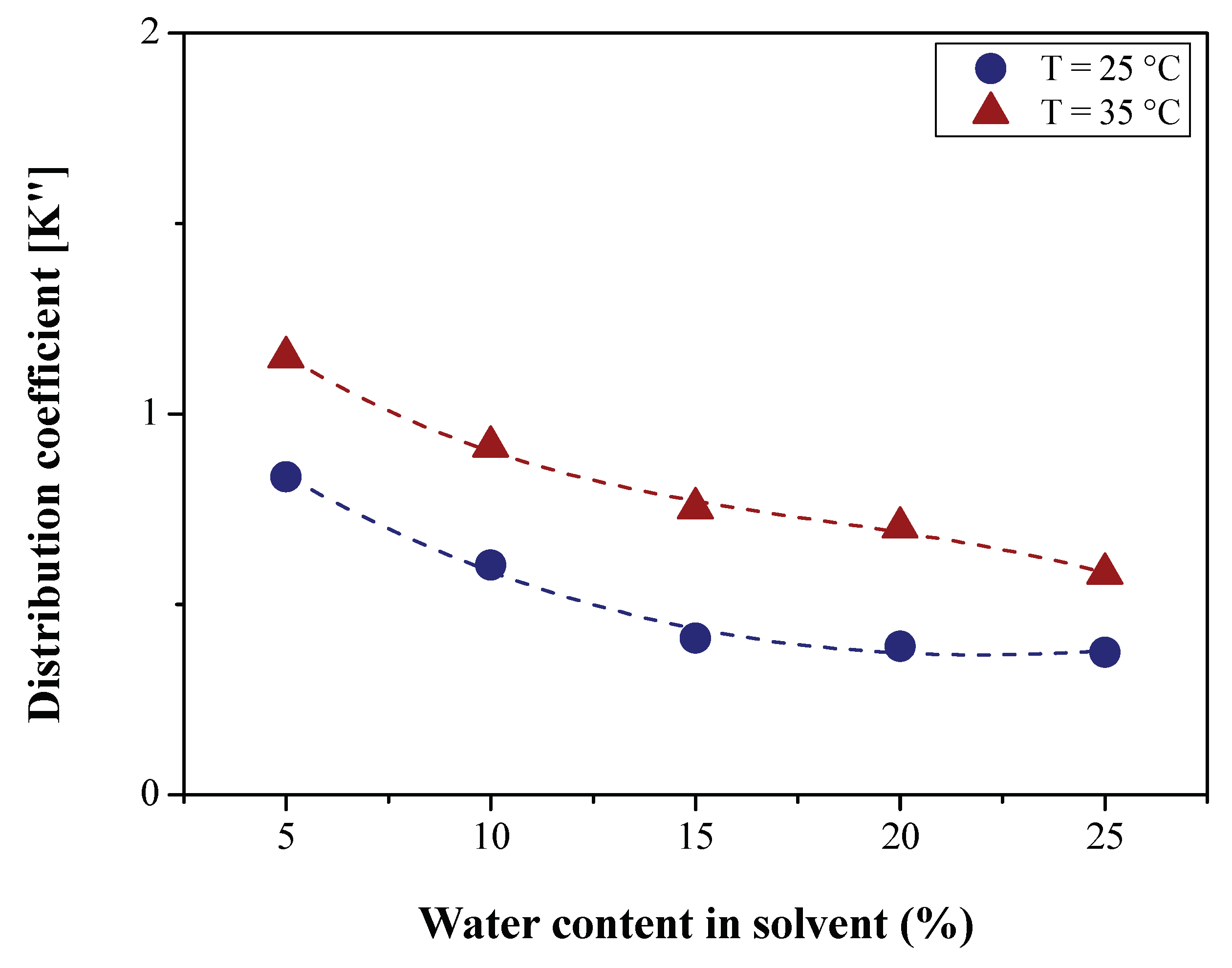

3.1.2. Efficiency of LLE Deacidification

Effect of Water Content on Deacidification

Effect of Acid Content in the Feedstock on Deacidification

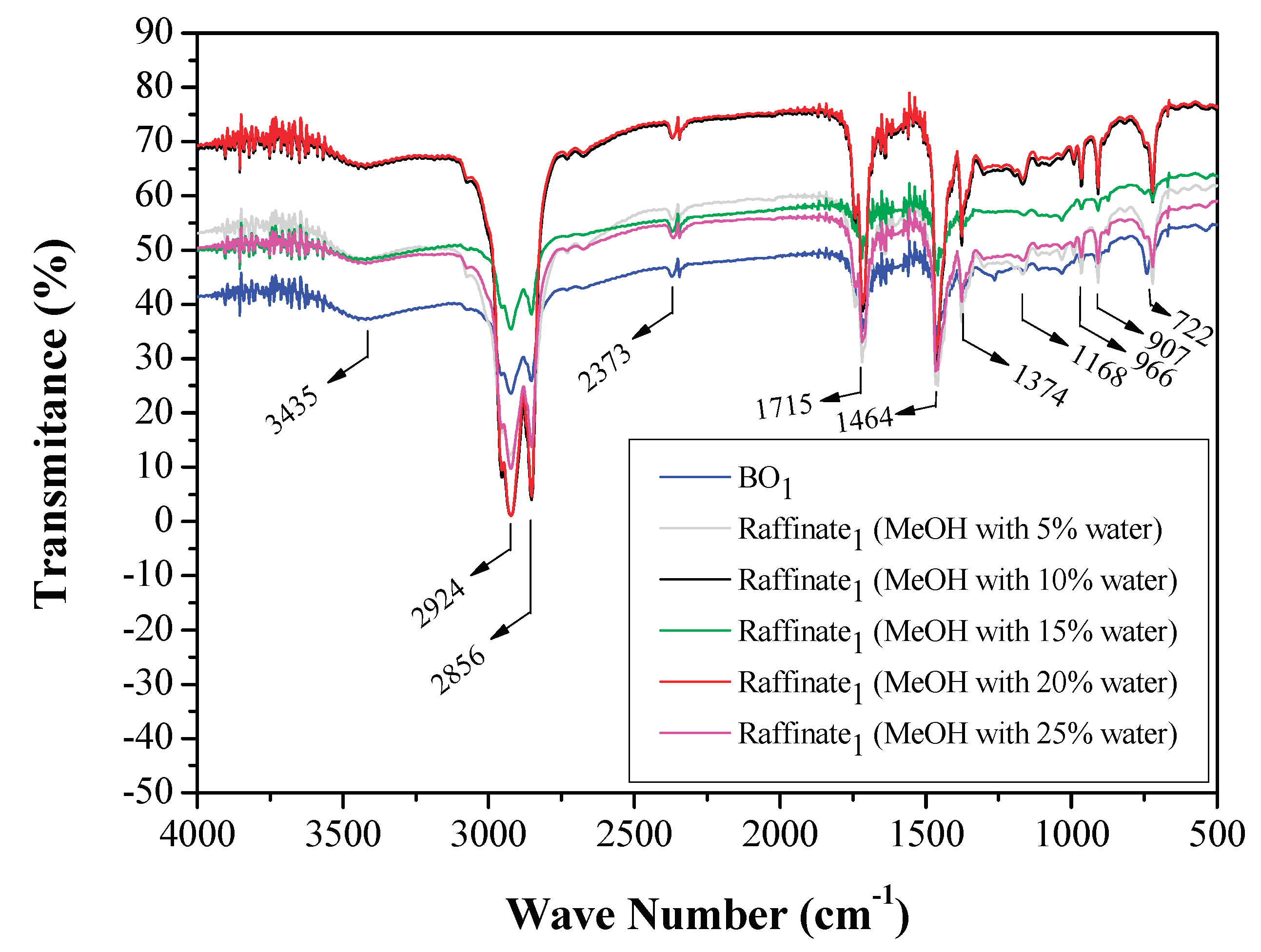

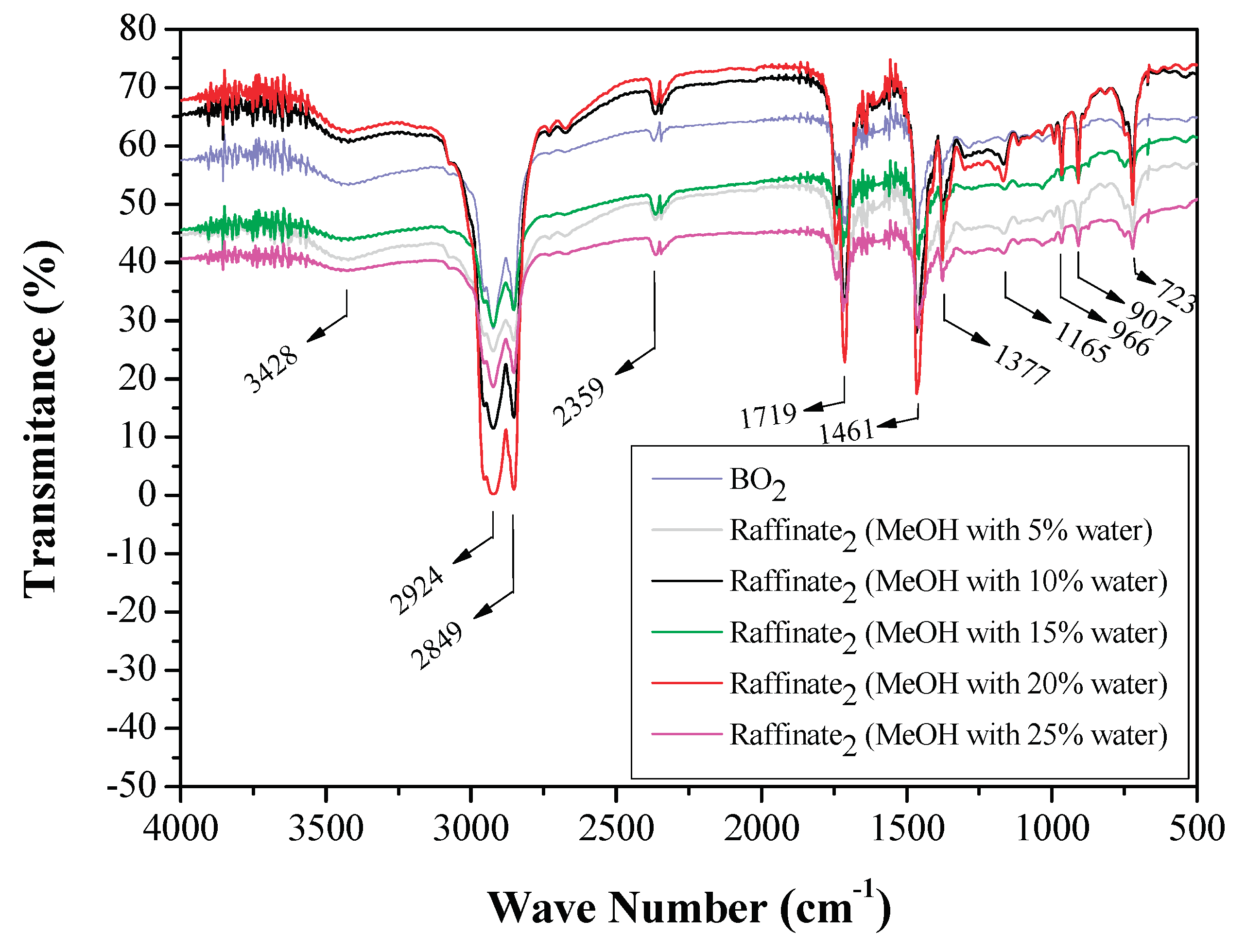

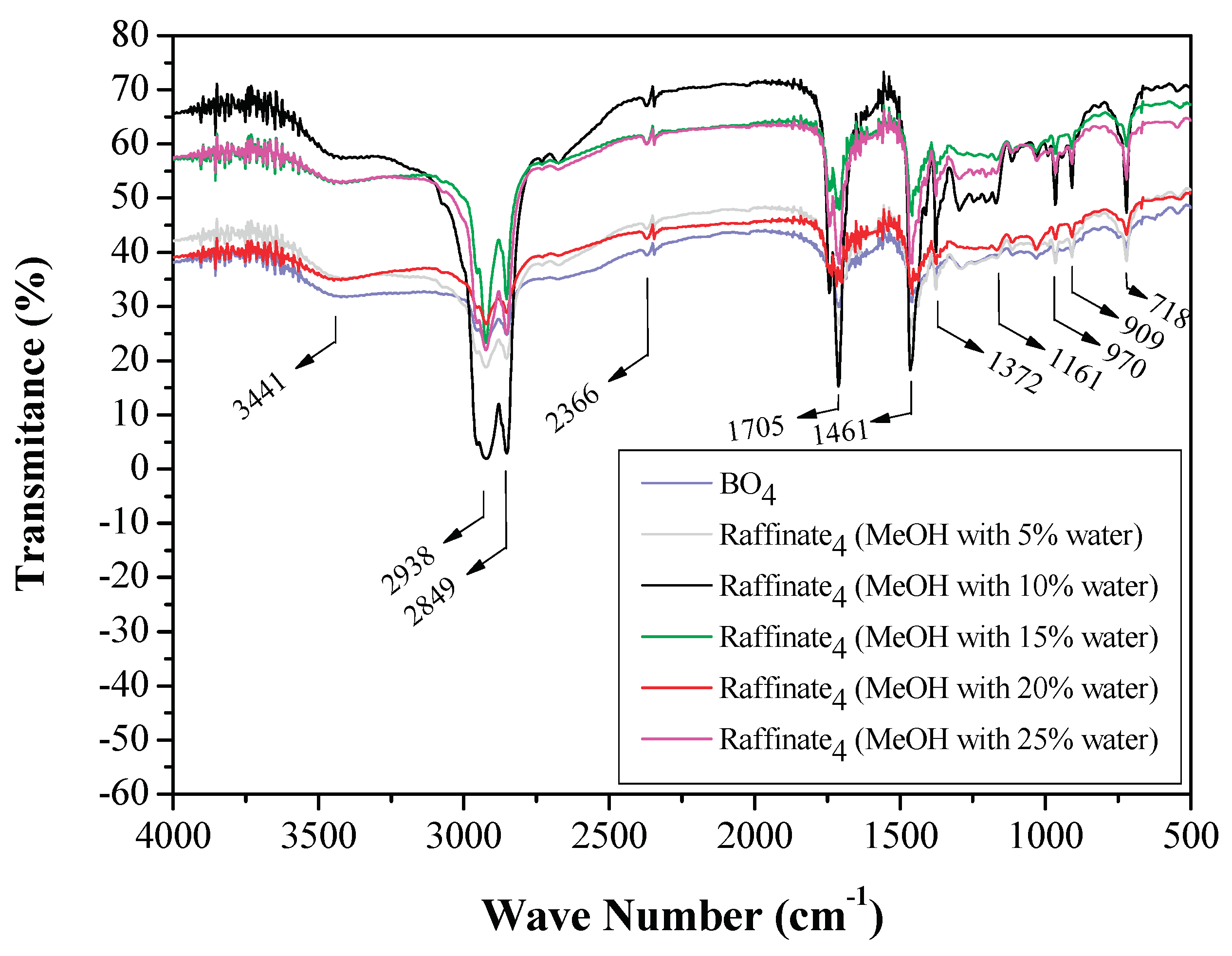

3.1.3. FTIR Analysis of Original Bio-Oils and Raffinate Streams

3.2. Deacidification of BOs by LLE (Experiment Group II)

3.2.1. Effect of BO Deacidification on the Quality of Raffinates

3.2.2. Efficiency of LLE Deacidification

3.2.2.1. Effect of Temperature on Deacidification

3.2.3. Chemical Composition

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chan, Y.H.; Loh, S.K.; Chin, B.L.F.; Yiin, C.L.; How, B.S.; Cheah, K.W.; Wong, M.K.; Loy, A.C.M.; Gwee, Y.L.; Lo, S.L.Y.; et al. Fractionation and Extraction of Bio-Oil for Production of Greener Fuel and Value-Added Chemicals: Recent Advances and Future Prospects. Chemical Engineering Journal 2020, 397, 125406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stedile, T.; Ender, L.; Meier, H.F.; Simionatto, E.L.; Wiggers, V.R. Comparison between Physical Properties and Chemical Composition of Bio-Oils Derived from Lignocellulose and Triglyceride Sources. Renewable & Sustainable Energy Reviews 2015, 50, 92–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Lei, H.; Wang, L.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Chen, S.; Ahring, B. Liquid–Liquid Extraction of Biomass Pyrolysis Bio-Oil. Energy & Fuels 2014, 28, 1207–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naji, S.Z.; Tye, C.T.; Abd, A.A. State of the Art of Vegetable Oil Transformation into Biofuels Using Catalytic Cracking Technology: Recent Trends and Future Perspectives. Process Biochemistry 2021, 109, 148–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, K.D.; Bressler, D.C. Pyrolysis of Triglyceride Materials for the Production of Renewable Fuels and Chemicals. Bioresour Technol 2007, 98, 2351–2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bielansky, P.; Reichhold, A.; Schönberger, C. Catalytic Cracking of Rapeseed Oil to High Octane Gasoline and Olefins. Chemical Engineering and Processing: Process Intensification 2010, 49, 873–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czernik, S.; Bridgwater, A. V. Overview of Applications of Biomass Fast Pyrolysis Oil. Energy and Fuels 2004, 18, 590–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirbas, A. Recovery of Gasoline Range Fuels from Vegetable Oils. Energy Sources Part a-Recovery Utilization and Environmental Effects 2009, 31, 420–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabie, A.M.; Mohammed, E.A.; Negm, N.A. Feasibility of Modified Bentonite as Acidic Heterogeneous Catalyst in Low Temperature Catalytic Cracking Process of Biofuel Production from Nonedible Vegetable Oils. J Mol Liq 2018, 254, 260–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, Y.K.; Bhatia, S. The Current Status and Perspectives of Biofuel Production via Catalytic Cracking of Edible and Non-Edible Oils. Energy 2010, 35, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vonghia, E.; Boocock, D.G.B.; Konar, S.K.; Leung, A. Pathways for the Deoxygenation of Triglycerides to Aliphatic Hydrocarbons over Activated Alumina. Energy & Fuels 1995, 9, 1090–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridgwater, A. V Review of Fast Pyrolysis of Biomass and Product Upgrading. Biomass Bioenergy 2012, 38, 68–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, D.G.; Soares, V.C.D.; Ribeiro, E.B.; Carvalho, D.A.; Cardoso, É.C. V; Rassi, F.C.; Mundim, K.C.; Rubim, J.C.; Suarez, P.A.Z. Diesel-like Fuel Obtained by Pyrolysis of Vegetable Oils. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis 2004, 71, 987–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taufiqurrahmi, N.; Bhatia, S. Catalytic Cracking of Edible and Non-Edible Oils for the Production of Biofuels. Energy Environ Sci 2011, 4, 1087–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, T.Y.; Mohamed, A.R.; Bhatia, S. Catalytic Conversion of Palm Oil to Fuels and Chemicals. Can J Chem Eng 1999, 77, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S. High-Efficiency Separation of Bio-Oil. In Biomass Now - Sustainable Growth and Use; Matovic, M.D., Ed.; InTech, 2013; pp. 401–418.

- Huber, G.W.; Iborra, S.; Corma, A. Synthesis of Transportation Fuels from Biomass: Chemistry, Catalysts, and Engineering. Chem Rev 2006, 106, 4044–4098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Liu, R.H.; Yin, R.Z.; Mei, Y.F. Upgrading of Bio-Oil from Biomass Fast Pyrolysis in China: A Review. Renewable & Sustainable Energy Reviews 2013, 24, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiu, S.N.; Shahbazi, A. Bio-Oil Production and Upgrading Research: A Review. Renewable & Sustainable Energy Reviews 2012, 16, 4406–4414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsul, N.S.; Kamarudin, S.K.; Rahman, N.A. Conversion of Bio-Oil to Bio Gasoline via Pyrolysis and Hydrothermal: A Review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2017, 80, 538–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloch, H.A.; Nizamuddin, S.; Siddiqui, M.T.H.; Riaz, S.; Jatoi, A.S.; Dumbre, D.K.; Mubarak, N.M.; Srinivasan, M.P.; Griffin, G.J. Recent Advances in Production and Upgrading of Bio-Oil from Biomass: A Critical Overview. J Environ Chem Eng 2018, 6, 5101–5118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiu, S.N.; Shahbazi, A. Bio-Oil Production and Upgrading Research: A Review. Renewable & Sustainable Energy Reviews 2012, 16, 4406–4414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisniewski, A.; Wosniak, L.; Scharf, D.R.; Wiggers, V.R.; Meier, H.F.; Simionatto, E.L. Upgrade of Biofuels Obtained from Waste Fish Oil Pyrolysis by Reactive Distillation. J Braz Chem Soc 2015, 26, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, K.; Maheria, K.C.; Dalai, A.K. Bio-Oil Valorization: A Review. Renewable & Sustainable Energy Reviews 2013, 23, 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Gunawan, R.; Mourant, D.; Hasan, M.D.M.; Wu, L.; Song, Y.; Lievens, C.; Li, C.-Z. Upgrading of Bio-Oil via Acid-Catalyzed Reactions in Alcohols — A Mini Review. Fuel Processing Technology 2017, 155, 2–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, L.; Li, H.; Yuan, X.; Zhou, W.; Huang, H. Bio-Oil Upgrading by Emulsification/Microemulsification: A Review. Energy 2018, 161, 214–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.R.; Wang, Y.R.; Cai, Q.J.; Wang, X.Y.; Jin, H.; Luo, Z.Y. Multi-Step Separation of Monophenols and Pyrolytic Lignins from the Water-Insoluble Phase of Bio-Oil. Sep Purif Technol 2014, 122, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, L.K.E.; Ren, S.; Yiacoumi, S.; Ye, X.P.; Borole, A.P.; Tsouris, C. Separation of Switchgrass Bio-Oil by Water/Organic Solvent Addition and PH Adjustment. Energy and Fuels 2016, 30, 2164–2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, D.W.; Perry, R.H. Perry’s Chemical Engineers’ Handbook, Eighth Edition; 8th ed. /.; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, 2008; ISBN 9780071422949. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Steele, P.H.; Mitchell, B.; Ingram, L.L.; Yu, F. The Addition of Water to Extract Maximum Levoglucosan from the Bio-Oil Produced via Fast Pyrolysis of Pretreated Loblolly Pinewood. Bioresources 2013, 8, 1868–1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ma, H.; Wu, S.; Jiang, W.; Wei, W.; Lei, M. Fractionation of Pyrolysis Oil Derived from Lignin through a Simple Water Extraction Method. Fuel 2019, 242, 587–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, N.M.; Helle, S.S.; Duff, S.J.B. Extraction and Hydrolysis of Levoglucosan from Pyrolysis Oil. Bioresour Technol 2009, 100, 6059–6063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitasari, C.R.; Meindersma, G.W.; de Haan, A.B. Water Extraction of Pyrolysis Oil: The First Step for the Recovery of Renewable Chemicals. Bioresour Technol 2011, 102, 7204–7210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanaujia, P.K.; Naik, D. V; Tripathi, D.; Singh, R.; Poddar, M.K.; Konathala, L.N.S.K.; Sharma, Y.K. Pyrolysis of Jatropha Curcas Seed Cake Followed by Optimization of Liquid⿿liquid Extraction Procedure for the Obtained Bio-Oil. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis 2016, 118, 202–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Li, D.B.; Liu, Y.Q.; Lv, D.C.; Ye, Y.Y.; Zhu, S.J.; Zhang, B.B. Study of a New Complex Method for Extraction of Phenolic Compounds from Bio-Oils. Sep Purif Technol 2014, 134, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, D.; Farag, S.; Chaouki, J.; Jessop, P.G. Extraction of Phenols from Lignin Microwave-Pyrolysis Oil Using a Switchable Hydrophilicity Solvent. Bioresour Technol 2014, 154, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Lange, J.-P.; Van Rossum, G.; Kersten, S.R.A. Bio-Oil Fractionation by Temperature-Swing Extraction: Principle and Application. Biomass Bioenergy 2015, 83, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Xia, S.; Ma, P. Upgrading Fast Pyrolysis Oil: Solvent–Anti-Solvent Extraction and Blending with Diesel. Energy Convers Manag 2016, 110, 378–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.-S.; Wu, Y.-L.; Yang, M.-D. Fractionation of Bio-Oil Produced from Hydrothermal Liquefaction of Microalgae by Liquid-Liquid Extraction. Biomass Bioenergy 2018, 108, 487–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Lyu, H.; Chen, K.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, S.; Chen, J. Selective Extraction of Bio-Oil from Hydrothermal Liquefaction of Salix Psammophila by Organic Solvents with Different Polarities through Multistep Extraction Separation. Bioresources 2014, 9, 5219–5233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukhbaatar, B.; Steele, P.H.; Ingram, L.L.; Kim, M.G. AN EXPLORATORY STUDY ON THE REMOVAL OF ACETIC AND FORMIC ACIDS FROM BIO-OIL. Bioresources 2009, 4, 1319–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, K.R.; Daane, M.L.; Schelling, R. Processing Corrosive Crude Oils. CORROSION 99 1999, NACE–99377. [Google Scholar]

- de Bruyn, H.J. Naphthenic Acid Corrosion in Synthetic Fuels Production. CORROSION 98 1998, NACE–98576. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, D.R.; Zheng, Y.G.; Jing, H.M.; Yao, Z.M.; Ke, W. High Temperature Naphthenic Acid Corrosion and Sulphidic Corrosion of Q235 and 5Cr1/2Mo Steels in Synthetic Refining Media. Corros Sci 2006, 48, 1960–1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- qu, D.R.; Zheng, Y.G.; Jiang, X.; Ke, W. Correlation between the Corrosivity of Naphthenic Acids and Their Chemical Structures. Anti-Corrosion Methods and Materials 2007, 54, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yépez, O. On the Chemical Reaction between Carboxylic Acids and Iron, Including the Special Case of Naphthenic Acid. Fuel 2007, 86, 1162–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Jiang, L.; Gan, F. High Temperature Naphthenic Acid Corrosion of Steel in High TAN Refining Media. Anti-Corrosion Methods and Materials 2008, 55, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Mota, S.D.P.; Mancio, A.A.; Lhamas, D.E.L.; De Abreu, D.H.; Da Silva, M.S.; Dos Santos, W.G.; De Castro, D.A.R.; De Oliveira, R.M.; Ara?jo, M.E.; Borges, L.E.P.; et al. Production of Green Diesel by Thermal Catalytic Cracking of Crude Palm Oil (Elaeis Guineensis Jacq) in a Pilot Plant. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis 2014, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paquot, C. 2.203 - Determination of the Ester Value (E.V.). In Standard Methods for the Analysis of Oils, Fats and Derivatives (Sixth Edition); Pergamon, 1979; p. 60 ISBN 978-0-08-022379-7.

- Treybal, R. EXTRACCIÓN EN FASE LÍQUIDA. Pdf 1968.

- Mancio, A.A.; da Costa, K.M.B.; Ferreira, C.C.; Santos, M.C.; Lhamas, D.E.L.; da Mota, S.A.P.; Leão, R.A.C.; de Souza, R.O.M.A.; Araújo, M.E.; Borges, L.E.P.; et al. Thermal Catalytic Cracking of Crude Palm Oil at Pilot Scale: Effect of the Percentage of Na2CO3 on the Quality of Biofuels. Ind Crops Prod 2016, 91, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, L.K.E.; Liu, J.; Yiacoumi, S.; Borole, A.P.; Tsouris, C. Contribution of Acidic Components to the Total Acid Number (TAN) of Bio-Oil. Fuel 2017, 200, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oasmaa, A.; Elliott, D.C.; Korhonen, J. Acidity of Biomass Fast Pyrolysis Bio-Oils. Energy & Fuels 2010, 24, 6548–6554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.L.; Martins, D.U.; Iha, O.K.; Ribeiro, R.A.; Quirino, R.L.; Suarez, P.A. Agro-Industrial Residues as Low-Price Feedstock for Diesel-like Fuel Production by Thermal Cracking. Bioresour Technol 2010, 101, 6157–6162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buzetzki, E.; Sidorová, K.; Cvengrošová, Z.; Kaszonyi, A.; Cvengroš, J. The Influence of Zeolite Catalysts on the Products of Rapeseed Oil Cracking. Fuel Processing Technology 2011, 92, 1623–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. J. Haas Animal Fats. In Bailey’s Industrial Oil and Fat Products; Shahidi, F., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, New Jersey, 2005; pp. 267–284.

- GUNSTONE, F.D. The Chemistry of Oils and Fats: Sources, Composition, Properties and Uses; Blackwell Publishing Ltd: Oxford, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, W.-L.; Tan, Z.-Q.; Wu, G.-J.; Yuan, L.; Zhu, W.-L.; Bao, Y.-L.; Pan, L.-Y.; Yang, Y.-J.; Zheng, J.-X. Deacidification of Crude Low-Calorie Cocoa Butter with Liquid–Liquid Extraction and Strong-Base Anion Exchange Resin. Sep Purif Technol 2013, 102, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reipert, É.C.D. Babassu and Cottonseed Oils Deacidification by Liquid-Liquid Extraction. Dissertation, Universidade Estadual de Campinas (UNICAMP): Campinas, 2005.

- Oliveira, C.M.; Garavazo, B.R.; Rodrigues, C.E.C. Liquid-Liquid Equilibria for Systems Composed of Rice Bran Oil and Alcohol-Rich Solvents: Application to Extraction and Deacidification of Oil. J Food Eng 2012, 110, 418–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavia, D.L.; Lampman, G.M.; Kriz, G.S.; Vyvyan, J.R. Introduction to Spectroscopy, 4th ed.; Cengage Learning: Belmont, CA - USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein, R.M.; Webster, F.X.; Kiemle, D.J. Spectrometric Identification of Organic Compounds, 7th ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, S.; Ye, X.P.; Borole, A.P. Separation of Chemical Groups from Bio-Oil Water-Extract via Sequential Organic Solvent Extraction. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis 2017, 123, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Shafaghat, H.; Kim, J. Kon; Jeon, J.K.; Jung, S.C.; Lee, I.G.; Park, Y.K. Upgrading of Pyrolysis Bio-Oil Using WO3/ZrO2 and Amberlyst Catalysts: Evaluation of Acid Number and Viscosity. Korean Journal of Chemical Engineering 2017, 34, 2180–2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Physical-chemical property | Test Method | Feedstock (Bio-oils) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BO1 | BO2 | BO3 | BO4 | ||

| Specific gravity at 20 °C (kg/m3) | ASTM D4052 | 815.00 | 826.00 | 848.56 | 860.00 |

| Viscosity at 40 °C cSt (mm2/s) | ASTM D445 | 4.65 | 5.21 | 6.5885 | 5.51 |

| Corrosiveness to copper, 3 h at 50 °C | ASTM D130 | 1A | First | 1A | 1A |

| TAN (mg KOH/g) | ASTM D974 | 24.38 | 33.21 | 51.5600 | 73.77 |

| Saponification value (mg KOH/g) | AOCS Cd 3-25 | 48.23 | 67.00 | 70.9480 | 108.54 |

| Ester content (mg KOH/g) | Paquot [49] | 23.85 | 34.79 | 19.388 | 34.77 |

| Refractive index | AOCS Cc 7-25 | 1.457 | 1.458 | 1.4580 | 1.457 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).