1. Introduction: Last Chance Tourism and Ecological Grief

This review synthesizes key scientific works on Last Chance Tourism (hereafter LCT) and Ecological Grief and argues for an emplacement of grief and mourning in LCT and sustainable tourism research in general. Rather than providing an exhaustive review of papers on these topics, it aims to provide a conceptual underpinning for future research that can fruitfully combine these concepts, which can further serve as a pointer towards improving tourism praxis in LCT destinations. The case of the Arctic is highlighted both owing to the high ecological sensitivity of the region in the face of intensifying climate change effects, as well as its position in both LCT and Ecological Grief-related literature.

Last Chance Tourism is defined as a niche form of tourism where “tourists explicitly seek vanishing landscapes or seascapes, and/or disappearing natural and/or social heritage” [

1]. LCT destinations span the globe and range from the tropical Great Barrier Reef and African rainforests to the icy worlds of Antarctica and the Arctic [

2,

3,

4,

5]. The Arctic is a major frontier for LCT, with the term initially gaining significance as a form of tourism that was borne out of the interest of cold places [

6,

7], and therefore climate change effects played a major part in defining LCT destinations from the outset [

7]. However, while LCT has an apparent connection with environmental change, it is not necessarily strongly coupled with the concerns for sustainability or sustainable tourism [

7] and in fact, self-fulfillment and personal satisfaction remain primary motivational factors behind many forms of LCT [

8]—aspects that will be discussed in more detailed below.

Ecological Grief is a concept that has steadily gained traction in environmental studies literature for over a decade now [

9]. Ecological Grief is defined as “the grief felt in relation to experienced or anticipated ecological losses, including the loss of species, ecosystems and meaningful landscapes due to acute or chronic environmental change” [

9,

10]. The ongoing pervasive human modification of the biosphere and intensifying environmental crises are pivotal behind this concept [

9,

11]; as it calls for mourning and explicit forms of expression of sorrow toward empowering forms of ecological care and planetary wellbeing [

11,

12], also speaking for environmental justice in the process [

13]. Dying rainforests, the vanishing cryosphere, oceanic acidification, and species extinction are all foci of ecological grief research [

11]—and notably, the changes in the Arctic have played a vital part behind the development of this concept [

14].

The Arctic as a place that in many ways embodies the intensifying anthropogenic modification of the biosphere and the consequent repercussions on local lifeways and culture has emerged at the forefront of both scientific and social research for some time now [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. Tourism is deeply entwined with the ideals of development in the Arctic [

20], and the global tourism industry is increasingly a key player in the region [

21,

22,

23]—and this has led to calls for deeper, reflexive and more collaborative forms of research in tourism that strives to understand the inherent plurality of the Arctic [

24,

25]. These key works are also indicative of a developing tension between the intensifying touristic consumption/development discourses of the Arctic and an ecological anxiety that justifies further scholarly engagement with the region.

In the subsequent sections, the article provides overviews of the LCT and Ecological Grief concepts; introduces some key aspects/contours of the ecological transformation of the Arctic; provides a concise discussion that seeks to combine LCT and Ecological Grief research; and presents a brief conclusion.

2. Last Chance Tourism and Cryospheric Change in the Arctic

As already noted above, LCT is seen as a niche form of tourism where tourists seek to encounter endangered landscapes/landmarks or species. A full summary of LCT trends can be found in Lemelin and Whipp (2019) [

26]. In one of the earlier works on LCT, Lemelin et al. (2010) described it as an offshoot or complementary development out of the more generic ‘dark tourism’—the key difference being that rather than revisiting memories of war or social disturbances, tourists in LCT seek to engage with the anthropogenic transformation of ‘formerly remote areas’ [

1]. The interest in a vulnerable yet visually beautiful cryosphere has long framed tourism activities in polar regions [

27]. Major attractions of polar tourism include landscapes, endangered polar megafauna, and indigenous cultures—and some signature sites mentioned by Lemelin et al. (2010) are the Illulissat Icefjord of Greenland, the Kluane / Wrangell-St. Elias / Glacier Bay / Tatshenshini-Alsek World Natural Heritage Site of Canada and the US, and the popular polar-bear viewing destination of Churchill in Manitoba, Canada [

1]. Concerns about change in polar environments feature in several papers on LCT [

3,

28,

29,

30]. While describing LCT in Kaktovik, Alaska (another popular destination for polar bear-viewing tourists), Miller et al. (2020) observe that “..a worthy goal of LCT would be to increase the awareness and conservation actions of visitors to these locations, perhaps mitigating impacts contributing to their demise” [

31]. They further argue that the deeper and more extensive the immersion of the tourist into the environment, the higher the probability that some type of pro-environmental behavior or awareness would be observed among visitors. Additionally, Powell et al. (2011) suggested that visitor impressions of the Antarctic included five ‘awe’ elements that included spiritual connection, transformative experience, and a sense of feeling humbled [

32]. Such studies suggest that it is plausible that LCT as an activity could lead to heightened environmental awareness and potentially to ambassadorship for conservation.

Yet, as numerous studies also clearly highlight, currently LCT activities (including those in the Arctic) fall short of fulfilling a substantial role in addressing/mitigating ecological concerns. Eijgelaar et al.’s (2010) study found no evidence that Antarctic cruises resulted in any meaningful awareness of the GHG emission problem [

29] and Vila et al. (2016) observed that while trips to Antarctica modified the thinking of visitors, the reported change in perspectives does not necessarily favor ecological concern and therefore the perceived ‘ambassadorship’ role of LCT tourists in Antarctica could not be established from visitor responses [

33]. Groulx et al.’s (2019) study on the two cases of LCT Churchill (polar bear viewing) and the Jasper National Park (glacier tourism) in Canada also support this paradox of tourists attaching a high ‘value’ to endangered landscapes/biota yet refusing to become self-critical regarding GHG emissions from their own travel [

34]. Regarding tourism in the Arctic, the general backdrop of a rapid, several-fold increase in visitor numbers over the last decade or so [

35] must also be kept in mind, as this creates a real and tangible footprint on the Arctic environment that cannot merely be wished away with good thoughts.

As this discussion shows, there are two major paradoxes of LCT in polar environments: (i) the personal motivations of the visitors may not necessarily align with ecological concerns and (ii) the very act of engaging in LCT can further pressurize/transform these vulnerable environments. Regarding visitor motivations, studies report of self-fulfillment, longing to see iconic places and animals (or plants) before they disappear, and seeing/experiencing exotic cultures of remote places [

3,

7,

8]. Dawson et al. (2011) provide two important observations in this regard: firstly that “LCT is more about: (1) the perception of vulnerability among the general public and (2) that which is perceived to be vulnerable (i.e. landscapes, seascapes, flora, fauna, built environments, or cultures), than it is about the exact attributes of a particular destination” and that LCT research should move on from judging whether LCT is intrinsically good or bad to examining which aspects of LCT are good or bad in what type of contexts [

3]. An important caveat that follows from the first observation is that much of the LCT in practice is currently influenced by media and popular ‘imagery’ of the place rather than in-depth academic knowledge, which is connected to the risk that LCT activities are prone to engaging with the destinations in a superficial manner.

There are numerous works that highlight the fundamental conundrum of any LCT involving travel to remote locations which in turn means that the carbon footprint of such travel sits at odds with any noble aims that the tourists or the tour-operators might have [

8,

22,

29,

36]. The key lesson here is that because anthropogenic climate change is the key driver of disruptive change in most LCT destinations—and certainly the case for the Arctic—any rhetorical solution is ultimately devoid of meaning as the very act of traveling to those locations adds up further CO

2 in the atmosphere and accelerate the demise of the places the tourists are willing to visit. This situation also lays bare the deeply consumptive nature of LCT—i.e. that those engaging in LCT are nevertheless willing to travel to remote places when there is overwhelming evidence of the disproportionate carbon footprint of long-distance travel within the tourism sector which in turn translates to a major share in tourism’s contribution to climate change [

37,

38].

There is a third angle regarding that deserves particular attention, especially in the case of the Arctic. This is the ‘ethical’ issue of visiting endangered species and rapidly changing places/communities for self-fulfillment, thereby subjecting them to an act of ‘ocular consumption’. Dawson et al. (2011) touch upon this aspect by observing that what we ‘should do’ is an ethical question that requires case-by-case analysis. Several researchers have reported critically on endangered polar wildlife such as the polar bear being subjected to intense ocular consumption—without any meaningful commitment on the part of the tourists to conserve the species or its habitat [

39,

40,

41]. What is less often reported is a possible bias, even among researchers, to

accept the ongoing change and thus

normalizing it in tourism research-related discourses. Woosnam et al. (2021) report that LCT research literature tends to fall under either of the two camps of visitors and local tourism stakeholders [

42]. While there is some focus on host communities in LCT [

43], there is also the tendency to relate the ongoing change to the concept of ‘resilience’ perhaps all too easily [

22]; which translates to an inadequate understanding of the vulnerabilities and potential loss of connectivities between Arctic (especially indigenous) communities and a rapidly changing cryosphere. For example, a recent paper by Minor et al. (2023) that social exposure to climate change varies even within the Arctic—with Greenlanders being twice more likely to experience rapid change in the cryosphere and local ecosystems compared to other Arctic countries, and the possibility that the pace and trajectories of change may outstrip local reserves of social capital/preparedness. Grimwood (2014) made a similar observation regarding indigenous communities in the Canadian Arctic by noting that LCT narratives typically conceal the narratives of the indigenous communities [

28]. LCT destinations are also lived places, and environmental change is felt in a fundamentally different manner by these communities and also implies fundamental changes to their lifeworlds.

3. Ecological Grief and Its Relevance for LCT in the Arctic

Ecological Grief is seen as a direct response to global environmental change and research on this concept has also been termed as a response to climate change [

10]. It is also therefore a call for action on ecological destruction—through sharing affect, sympathies, support, and sorrow [

13]. An excellent and exhaustive review of the scientific literature on Ecological Grief can be found in Pikhala (2024) [

44]. Although Kevorkian (2024) makes a distinction between

environmental grief and

ecological grief where environmental grief is seen as grief stemming from the loss of ecosystems and ecological grief more as a form of sorrow arising out of our disconnection from the natural world [

45], it is clear that the two terms share a large amount of overlap. Ecological grief research has gained momentum over the last decade [

10] and the most important thread connecting various case studies is the sense of loss shared by communities as well as scientists/researchers. Cunsolo and Ellis (2018) [

9] remains a key paper that sums up the conceptual foundations as well as the current research frontier on Ecological Grief. In this paper the authors make several important observations such as ecological grief is generally disenfranchised or mostly left unconsidered in climate change narratives and policy research; that the loss of local ecological knowledge can be a trigger for ecological grief; and that Arctic (Inuit) communities typically encounter a disproportionate share of ecological grief which reflects the sudden shift and erosion of traditional lifeways/knowledge gained over multiple generations. One of the earliest expressions of ecological grief in English literature can be found in Aldo Leopold’s reflections; and perhaps more importantly the seminal work ‘Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor’ by Rob Nixon (2011) in which he analyzes the disproportionate effect of environmental change on the poor and those people who share a close connection with the land [

46]. In this work, Nixon also explicitly mentioned the ‘thawing cryosphere’ as a key element of such change [

46]. Among other key works is the essay by Phyllis Windle (1992) who elaborated on the emotional attachments scientists (ecologists) have with ecosystems and species [

47]. It should also be noted that the role of grief and mourning as a powerful tool for protesting the degradation of complex ecological systems and therefore a means to fulfill our ethical responsibility towards nonhumans is also present in the works of feminist scholars such as Butler (2006)—whose thoughts influenced this concept (48, 9).

As already mentioned, cryospheric change and community perceptions in the Arctic played an essential part in the development of the ecological grief concept from the outset. Early studies covered situations in Nunatsiavut, Canada as well as the circumpolar region in general [

49]. In the opening of the volume ‘Mourning Nature: Hope at the Heart of Ecological Loss and Grief’, Cunsolo (2018;a) describes how stories from the Inuit people in Nunatsiavut were instrumental behind the formation of the concept. Recounting the sorrow of a particular Inuit woman, she writes how the tears of that woman moved and transformed her own thoughts [

50]. In a subsequent chapter, Cunsolo (2018;b) sums up this process as ‘to mourn beyond the human’—revealing the central importance of nonhumans/more-than-humans in the narratives of ecological grief [

51]. Thus, while the expression of grief is a cultural process and ecological knowledge, mindfulness, and emotions of the local communities (as well as researchers) are key elements, the deep connections between the local inhabitants and terrestrial/marine ecosystems surrounding them elicit this cultural process, which in turn means that the process transcends immediate human concerns and extends to the many species and ecosystems that together make the Iniut lifeworld. Accordingly, Cunsolo and Ellis (2018) observed that there are three types of ecological grief: (i) grief associated with physical ecological losses, (ii) grief associated with the loss of environmental knowledge, and (iii) grief associated with anticipated future losses. Firstly, grief associated with tangible ecological losses may include the degradation or actual disappearance of certain species/ecosystems/landscapes—relevant examples included Inuit grief in the face of changes witnessed in the landscape that inhibited the ability to travel on ice to procure food. Regarding grief associated with environmental knowledge, disruptive and sudden climate change-related effects were observed to lead to sadness and distress among the Inuit as traditional knowledge about ice, seasonal patterns, and animal behavior could no longer be considered reliable. Finally, grief pertaining to future ecological losses includes anxiety and uncertainty over what the future holds—exhibited by Sami reindeer herders who are apprehensive of future climate change effects on their resources and lifestyle [

9].

From this discussion, it is clear that while there has been no formal effort yet to combine them, both LCT and ecological grief have several aspects in common. These include (i) the actual physical setting (ii) the experiences encountered and (iii) what the future holds. The actual physical setting of LCT (in this case the focus is on the Arctic but it could be elsewhere such as Antarctica, rainforests or coral reefs, and still the same will apply) is also a landscape/seascape (or multiple landscapes/seascapes) of disruptive change and loss. However, the major difference between the two is that while in the LCT visitors are primarily motivated by self-fulfillment and the global tourism industry packages those landscapes/seascapes for consumption of (mostly affluent) tourists who are not primarily affected by the changes, ecological grief is felt acutely by the communities who share a primary connection with the changing landscapes and seascapes and therefore experience the disruptive change firsthand. Regarding the future, it is perhaps obvious that both LCT and ecological grief will be further affected/amplified as changes in the cryosphere accelerate and accumulate—resulting in a possible depletion of LCT resources and cascading changes to the lifeworlds of the indigenous communities and their knowledge systems. This strand of discussion will be revisited in the synthesis section below, but before that, it is necessary to briefly revisit some of the key changes in the Arctic environments.

4. Ongoing and Accelerating Changes in the Arctic environments

This section adds a brief note explaining some important trajectories of environmental change currently occurring in the Arctic. A comprehensive review of the changes is beyond the scope of this section (and the paper) and as such, this section should be read as an interlude to further relate the LCT and ecological grief concepts with the immediate realities of environmental change in the Arctic.

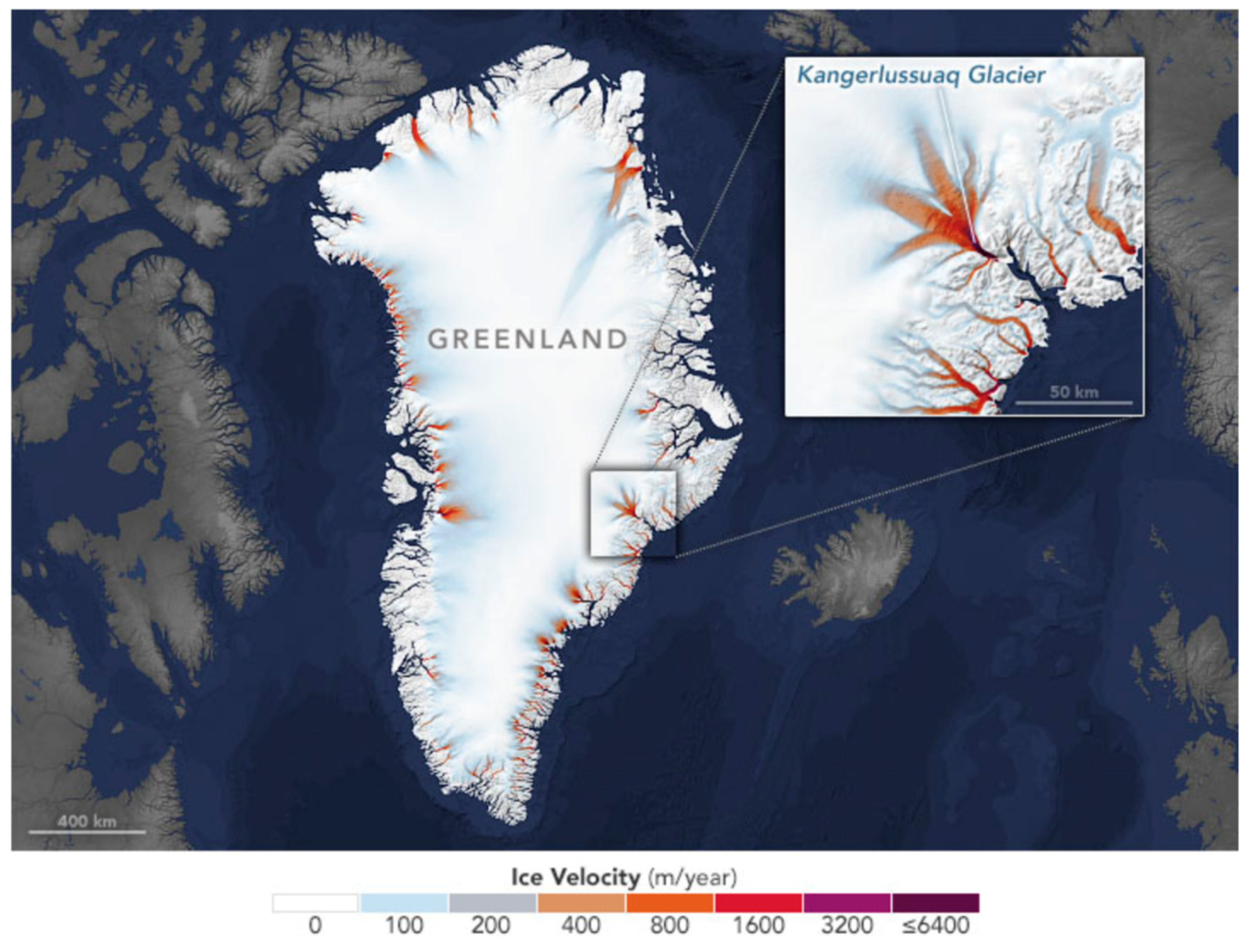

Firstly, regarding the effects of climate change, it has been widely reported that the Arctic is warming much faster than the global average, via a phenomenon known as the Arctic Amplification. There is some uncertainty on the rate of this warming—with studies variously reporting the amplification effect as twice, thrice, or even four times the global average [

52,

53,

54]. Rantanen et al.’s (2022) paper, by analyzing multiple datasets over the Arctic since 1979, reports that the Arctic is likely to be warming as much as four times the global average [

54]. Effects of this change are manifest over land and sea ice [

55,

56,

57]. Enhanced precipitation, increase in sea surface temperature and storminess, change in the cryosphere, intensified hydrological cycles, and coastal erosion are reported from across the Arctic [

58]. As it is clear from several of these studies, much of the change on the land relates to the condition of the Greenland Ice Sheet. While some scientists have reported a progressive change in ice rheology over the entire Holocene that resulted in thicker ice at the center of the sheet [

59], others have noted the progressive thinning of the sheet over the Holocene [

60]; with recent warming effects along the periphery being widespread and disruptive to the stability of the entire sheet [

61,

62 (for the graphic)]. Notably, Vinther et al.’s (2009) work identified the likelihood that far from being passive and stable as commonly understood, the Greenland Ice Sheet has had a history of vigorously interacting with climate fluctuations during the Holocene [

60]. This is an important realization as it presents the likelihood of the ice sheet behaving stochastically and in an increasingly fluctuating manner as climate change effects intensify. Regarding sea ice, it has been reported that Arctic sea ice showed negative trends throughout the year over the last three decades—with an abrupt regime-changing (negative) shift in ice thickness occurring in 2007 in the Fram Strait sea ice that constitutes a lion’s share of the outflowing sea ice from the Arctic to the Sub-Arctic [

63]. The authors of this study also reported shorter residence time and reduced thickness of sea ice in general, which translates to the loss of multi-year ice.

Figure 2.

Some notable examples of Arctic marine megafauna. Top (left to right): Arctic Tern, Atlantic Cod, Walrus. Center (left to right): Boreo-Atlantic Armhook Squid, Common Eider, White-beaked dolphin. Bottom (left to right): Bearded seal, Polar cod, Polar bear. Reprinted from Trends Ecol. Evol. Grémillet, D.; Descamps, S. Ecological impacts of climate change on Arctic marine megafauna. 38(8) 773-783. 2023, with permission from Elsevier.

Figure 2.

Some notable examples of Arctic marine megafauna. Top (left to right): Arctic Tern, Atlantic Cod, Walrus. Center (left to right): Boreo-Atlantic Armhook Squid, Common Eider, White-beaked dolphin. Bottom (left to right): Bearded seal, Polar cod, Polar bear. Reprinted from Trends Ecol. Evol. Grémillet, D.; Descamps, S. Ecological impacts of climate change on Arctic marine megafauna. 38(8) 773-783. 2023, with permission from Elsevier.

The effect of sea ice reduction on the Arctic marine ecosystem cannot be emphasized enough, sea ice is crucial for marine species survival in the area and plays a definitive role in biogeochemical mechanisms [

64]. Regional distributions of plankton, fish populations, and benthic biodiversity are all dependent on sea ice [

64,

65,

66]. Spatiotemporal heterogeneity plays an important role in the terrestrial biodiversity of the Arctic as well [

67]. In recent years, the expansion of northern temperate boreal species; expansion of parasites and non-indigenous species, and changes in the food-web and predator-prey dynamics which lead to transformational change in the trophic cascades have been reported [

68,

69,

70,

71]. Grémillet and Descamps (2023), in their analysis of the Arctic marine megafauna, cautioned that while changes in the Arctic Ocean ecosystems are observable, there are many uncertainties due to our incomplete understanding of the key species in those ecosystems and called for combining citizen-science based inquiries to understand ecosystem dynamics in the area better [

71]. One example of poorly understood megafauna is the Greenland Shark, which is still not adequately described in science but remains vulnerable due to overharvesting in the past and the proliferation of shipping and commercial fishing in its habitat [

72,

73]. In addition, as a study on musk oxen and caribou helped to illuminate, many Arctic land species have evolved in synchrony with the climate. They are easily affected by climate and landscape change dynamics [

74,

75,

76,

77]. Species such as the caribou have deep cultural significance for indigenous herders, whose voices were often unheard during phases of developing the Arctic through extractive and modern industries [

78,

79].

5. Synthesis: Combining Ecological Grief and LCT to Better Inform Travel in the Arctic

It is clear from the preceding discussion that while there is considerable interest and awareness of the Arctic environments and the effects of disruptive climate change among tourists, the current praxis of LCT is generally not based on ecological sensitivities. There is currently a major ‘rush’ to develop tourism in the Arctic which is seen as the ‘last frontier’ [

80]. The lack of ecological insights applies to an extent to LCT research as well, necessitating efforts to bridge the gap between the lucrative business of satisfying wealthy tourists as the Arctic becomes increasingly approachable for short-term visits, and the changing lifeworlds of communities who experience the effects of the diminishing cryosphere and associated changes firsthand and over the longer term. It can also be emphasized that human inhabitants alone are not the full story, nonhuman species and elements (such as snow, ice, water, rocks) are all essential parts of the Arctic community. Therefore, a traditional community-based approach is also likely to fall short in fully appreciating the contours of changes in the Arctic and a broader, fuller ecological concern that requires affect, empathy, and sensitivity toward the conditions of the wider human-nonhuman-more-than-human communities is required.

A section of tourism scholars has pertinently observed that despite its best efforts, tourism cannot decouple itself from its earthy entanglements [

81] in the Anthropocene when the human species has emerged as a major geological force that influences the trajectories of the Earth System [

82]. Recently, important markers in this regard have been laid down by Ren et al. 2023, Rantala et al. (2024), and Ren et al. (2024) in tourism research [

25,

83,

84]. In their paper Ren et al. (2023) called for ‘critical proximity’ in tourism research that upholds the need for discovering multiple attachments and entanglements between the researcher and the ‘field’—an approach that consciously refrains from making grand claims about phenomena and instead values fine-grained details and pluralities within them [

83]. Rantala et al. (2024) call for ‘proximity’ in tourism research, emphasizing the need to ascribe agency to both humans and nonhumans [

84]. As noted earlier, Ren et al. (2024) explore the specific case of Greenland and posit the term ‘connectivity’ as a further key to exploring the multiple relationalities/associations among humans and nonhumans in the Arctic [

25]. Elsewhere, some papers call for ‘emplacing’ nonhuman voices in tourism research and recognizing a new ‘value’ for nature that is based on its vulnerability [

85,

86].

Taking these views into account, and based on the discussion in the earlier sections, this article extends/complements them by arguing for the need to account for ‘ecological grief’ in LCT in the Arctic. The connection between ecological grief and the unfolding change in tourism destinations is so far inadequately addressed in tourism literature. The contention here is that, while it is necessary to celebrate the multiple relationalities and the entanglements of humans and nonhumans—in the Anthropocene there is an equally important duty to mourn the loss/diminution of many connections and particularly nonhuman counterparts/elements of the natural world that leave indelible imprints on the human lifeworld. That such accounts of loss and grief are rarely featured in the dominant narrative is precisely the reason to focus on them, because without understanding/appreciating the sense of loss, we cannot realistically achieve a fuller understanding of the changes currently unfolding in the Arctic. As pointed out in the previous sections, the Arctic cryosphere—manifested through the mechanisms of the Greenland Ice Sheet or Arctic sea ice—is a dynamic, vibrant entity, or rather a multitude of entities, that has the capability of interacting vigorously with the climate, geomorphological features, ecosystems, and societies. In addition, the dynamic cryosphere of the Arctic has been a key player in the evolution of species and their habitats, which in turn underpins the lifeways of the indigenous people and is a source of both traditional and scientific knowledge. The Arctic cryosphere in this sense is a sustaining force behind human creativity, culture, and science—and disruptive change in the wellbeing of this system has the potential to unhinge many ecological and cultural functions the effect of which would surely reverberate beyond the Arctic itself. Portraying the Arctic cryosphere as a mere backdrop for ongoing change, or a relic of the past that would inevitably change in the Anthropocene is therefore both short-sighted in a scientific sense and short of empathy from a cultural/emotional standpoint. Taking the emotive accounts of grief and loss associated with the changes in the cryosphere, and emplacing both human and nonhuman voices in those multiple narratives of loss and disenfranchisement allows us to ultimately look forward with hope, a hope of understanding the Arctic—both as a lived space and a tourism frontier—in a fuller manner.

Finally, it is useful to provide some broad contours of what LCT stakeholders might do in this regard. Due to the heightened interest in the Arctic in a time of rapid change, there will always be the global tourism industry that seeks to exploit the resources of the Arctic, and therefore mass-based and larger-scale versions of LCT are probably inevitable. Similarly, it is unrealistic to hope that LCT in the Arctic will achieve the ideals of ‘sustainable tourism’—notwithstanding the dichotomies inherent in that term itself. It will be equally impossible to completely replace the current dominant narratives based on resource consumption in LCT. However, by explicitly addressing loss and sorrow, it is possible to produce a powerful counter-narrative, one that can be useful to reclaim

travel in the age of tourism dominated by market forces. This counter-narrative can also chart a pathway where travelers consciously seek self-transformative experiences, along the lines of Stavans and Ellison (2015) [

87]. Side by side, LCT researchers may renew their focus on aspects such as: (i) What ecological issues are there in the Arctic? (ii) How can tourism contribute to ecologically informed outcomes? (iii) What level of willingness and awareness do visitors and stakeholders have towards that end? and (iv) How can travel in those destinations be self-reflexive and transformational?

Although not explicitly related to tourism, Varutti (2024) has given some important clues in this regard. She argues for the need for publicly grieving and mourning—which would unshackle mutual ecological sensitivities and empathies and help people to connect with one another through those acts. Furthermore, she mentions some useful approaches such as (i) developing ecological skills, (ii) intimacy, (iii) mental flexibility, and (iv) creativity [

13]. Developing ecological skills implies the cultivation of communicative skills that are based on ecological awareness and are aimed at ecological action. This facet could be vital as a resource for LCT guiding and interpretation. Intimacy helps us with the potential of sharing empathy and concern with others, and it may be observed, including nonhuman others. Mental flexibility and creativity could further enhance the two former facets, as the magnitude and rate of unfolding change in the Arctic cryosphere always require us to be prepared for the unexpected.

6. Conclusion

This review synthesized key literature about LCT and Ecological Grief concepts. While LCT has emerged as a new research frontier as well as an increasingly popular form of tourism, it has so far remained mainly preoccupied with tourist and stakeholder priorities and there are no reliable indications that current forms of LCT lead to ecological outcomes. This situation necessitates a counter-narrative that can forcefully address the vulnerabilities of both human and nonhuman communities. The Arctic provides a particularly instructive case in this regard, as it is a region that finds itself at the forefront of rapid and disruptive climate change. The concept of ecological grief can help us engage with the vanishing cryosphere—and the landscapes, species, and communities that have co-evolved with it—from an alternative angle of sharing sorrow, empathy, and concern. It also helps us to realize that the cryosphere of the Arctic is not a mere backdrop for change, but a vigorous and inherently pluralistic entity that fosters equally dynamic and multitudinous webs of life. While it may not entirely replace the dominant narratives of LCT whereby the Arctic is the last exotic frontier of tourism, such realization may enable tourism researchers to critically engage with and reclaim travel at multiple levels.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

“Not applicable.”

Conflicts of Interest

“The author declares no conflicts of interest.”

References

- Lemelin, H; Dawson, J.; Stewart, E.J. et al. Last-chance tourism: The boom, doom, and gloom of visiting vanishing destinations. Curr. Issues Tourism, 2010, 13(5), 477-493. [CrossRef]

- Piggott-McKellar, A.E.; McNamara, K.E. Last chance tourism and the Great Barrier Reef. J.Sustain. Tour., 2016, 25(3), 397-415. [CrossRef]

- Abrahams, Z.; Hoogendoorn, G.; Fitchett, J.M. Glacier tourism and tourist reviews: An experiential engagement with the concept of “Last Chance Tourism”. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2021, 22(1), 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Lamers, M.; Eijgelaar, E.; Amelung, B. Last chance tourism in Antarctica. In Last Chance Tourism: Adapting Tourism opportunities in a Changing World, Lelemin, R.H et al. (Eds). Routledge, London, UK. 2012. 25-41.

- Johnston, M.; Viken, A.; Dawson, J. First and lasts in Arctic tourism: Last chance tourism and the dialectic of change. In Last Chance Tourism: Adapting Tourism opportunities in a Changing World, Lelemin, R.H et al. (Eds). Routledge, London, UK. 2012. 10-24.

- Groulx, M.; Lemieux, C.; Dawson, J. et al. Motivations to engage in last chance tourism in the Churchill Wildlife Management Area and Wapusk National Park: The role of place identity and nature relatedness. J. Sustain. Tour. 2016, 24(1), 1523-1540. [CrossRef]

- Dawson, J.; Johnston, M.J.; Stewart, E.J. et al. Ethical considerations of last chance tourism. J. Ecotourism, 2011, 10(3). 250-265. [CrossRef]

- Hindley, A.; Font, X. Values and motivations in tourist perceptions of Last-chance tourism. Tourist Studies, 2015, 18(1). 3-14. [CrossRef]

- Cunsolo, A.; Ellis, N.R. Ecological grief as a mental health response to climate change-related loss. Nat. Clim.Change 2018, 8. 275-281. [CrossRef]

- Cunsolo, A.; Harper, S.L.; Minor, K. et al. Ecological grief and anxiety: The start of a healthy response to climate change? The Lancet 2020, e261-e263. [CrossRef]

- Cunsolo, A.; Landman, K. (Eds). Mourning Nature: Hope at the Heart of Ecological Loss & Grief. McGill Queen’s University Press, Canada. 2017.

- Barnett, J.T. Mourning in the Anthropocene: Ecological Grief and Earthly Coexistence. Michigan State University Press, USA. 2022.

- Varutti, M. Claiming ecological grief: Why are we not mourning (more and more publicly) for ecological destruction? Ambio, 2024, 53. 552-564. [CrossRef]

- Cunsolo Willoux, A.; Harper, S.L.; Ford, J.D. et al. “From this place and of this place:” Climate change, sense of place, and health in Nunatsiavut, Canada. Soc.Sci. Med. 2012. 75(3), 538-547. [CrossRef]

- Meltofte, H.; Christensen, T.R.; Elberling, B. et al. (Eds). High-Arctic Ecosystem Dynamics in a Changing Climate. Academic Press, Amsterdam, the Netherlands. 2008.

- Hobbie, J.E.; Kling, G.W. (Eds). Alaska's Changing Arctic: Ecological Consequences for Tundra, Streams, and Lakes. Oxford University Press, London, UK. 2014.

- Nord, D. The Changing Arctic: Consensus Building and Governance in the Arctic Council. Palgrave MacMillan, UK. 2016.

- Nuttall, M. Under the Great Ice: Climate, Society and Subsurface Politics in Greenland. Routledge, London, UK. 2017.

- Minor, K.; Jensen, M.L.; Hamilton, L. et al. Experience exceeds awareness of anthropogenic climate change in Greenland. Nat. Clim. Change. 2023. 13, 661-670. [CrossRef]

- Hall, D. Tourism, Climate Change and the Geopolitics of Arctic Development: The Critical Case of Greenland. CABI, Wallingford, UK. 2021.

- Mason, P.; Johnston, M.; Twynam, D. The World Wide Fund for Nature Arctic Tourism Project. J. Sustain. Tour. 2010. 8(4), 305-323. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.S.; Wang, W.; Kim, H.; Liu, W. Climate change model on Arctic tourism: Perspectives from tourism professionals. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2022 (Online version). [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Chen, J.S.; Prebensen, N.K. Market analysis of value-minded tourists: Nature-based tourism in the Arctic. J. Destin. Mark. Manage. 2018, 8. 82-89. [CrossRef]

- Hansen, A.M.; Ren, C. (Eds). Collaborative Research Methods in the Arctic: Experiences from Greenland. Routledge, London, UK. 2020.

- Ren, C.; Jóhannesson, G.T.; Ásgeirsson, M.H. et al. Rethinking connectivity in Arctic tourism development. Ann. Tour. Res. 105, 103705. [CrossRef]

- Lemelin, H.; Whipp, P. Last chance tourism: A decade in review. In Handbook of Globalization and Tourism, Timothy, D.J (Ed), Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, UK. 2019. 316-322.

- Hall, C.M; Johnston, M.E. (Eds). Polar Tourism: Tourism in the Arctic and Antarctic. John Wiley & Sons, 1995. New York, USA.

- Grimwood, B. Advancing tourism’s moral morphology: Relational metaphors for just and sustainable arctic tourism. Tourist Studies, 2014, 15(1), 3-26. [CrossRef]

- Eijgelaar, E.; Thaper, C.; Peeters, P. Antarctic cruise tourism: The paradoxes of ambassadorship, “last chance tourism” and greenhouse gas emissions. J. Sustain. Tour. 2010, 18(3), 337-354. [CrossRef]

- Tejedo, P.; Benayas, J.; Cajiao, D. et al. What are the real environmental impacts of Antarctic tourism? Unveiling their importance through a comprehensive meta-analysis. Jour. Environ. Manage. 2022, 308, 114634. [CrossRef]

- Miller, L.B.; Hallo, J.C.; Dvorak, R.G. et al. On the edge of the world: Examining pro-environmental outcomes of last chance tourism in Kaktovik, Alaska. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28(11), 1703-1722. [CrossRef]

- Powell, R.B.; Brownlee, M.T.J.; Kelert, S.R.; Ham, S.M. From awe to satisfaction: Immediate affective responses to the Antarctic tourism experience. Polar Record 2011, 48(2), 145-156. [CrossRef]

- Vila, M.; Costa, G. et al. Contrasting views on Antarctic tourism: ‘last chance tourism’ or ‘ambassadorship’ in the last of the wild. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 111. 451-460. [CrossRef]

- Groulx, M.; Boluk, K.; Lemieux, C.J.; Dawson, J. Place stewardship among last chance tourists. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 75, 202-212. [CrossRef]

- Runge, C.A.; Daigle, R.M.; Hausner, V.H. Quantifying tourism booms and the increasing footprint in the Arctic with social media data. PLoS ONE 2020 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0227189.

- D’Souza, J.; Dawson, J.; Groulx, M. Last chance tourism: A decade review of a case study on Churchill, Manitoba’s polar bear viewing industry. J. Sustain. Tour. 2023, 31(1), 14-31. [CrossRef]

- Lenzen, M.; Sun, Y.Y. et al. The carbon footprint of global tourism. Nat. Clim. Change. 2018. 8, 522–528. [CrossRef]

- Perkins, S. Tourism is four times worse for the planet than previously believed. Science (News) 2018. [CrossRef]

- Lemelin, R.H. The Gawk, The Glance, and The Gaze: Ocular Consumption and Polar Bear Tourism in Churchill, Manitoba, Canada. Curr. Iss. Tour. 2006, 9(6), 516-534. [CrossRef]

- Yudina, O.; Grimwood, B. Situating the wildlife spectacle: Ecofeminism, representation, and polar bear tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 24(5), 715-734. [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, S. Defining a visual metonym: A hauntological study of polar bear imagery in climate communication. Trans Inst Br Geogr. 2022, 47. 1104–1119. https://www.doi.org/10.1111/tran.12543.

- Woosnam, K.M.; Ribeiro, M.A.; et al. Psychological Antecedents of Intentions to Participate in Last Chance Tourism: Considering Complementary Theories. J. Travel. Res. 2022, 61(6). 1342-1357. [CrossRef]

- Schweinsberg, S.; Wearing, S.; Lai, P.H. Host communities and last chance tourism. Tourism Geographies 2021, 23(5-6), 945-962. [CrossRef]

- Pikhala, P. Ecological Sorrow: Types of Grief and Loss in Ecological Grief. Sustainability 2024. 16(2) 849. [CrossRef]

- Kevorkian, K. A Dying World (Website) 2024. URL https://drkkevorkian.com/ecological-environmental-grief/.

- Nixon, R. Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor. Harvard University Press, USA 2011.

- Windle, P. The ecology of grief. BioScience 1992, 42, 363-366. [CrossRef]

- Butler, J. Precarious Life: The Powers of Mourning and Violence. Verso, 2006.

- Cunsolo Willox, A. Stephenson, E. et al. Examining relationships between climate change and mental health in the Circumpolar North. Regional Environ. Change. 2015, 15, 169-182. [CrossRef]

- Cunsolo A. Prologue: She was bereft. In Mourning Nature: Hope at the Heart of Ecological Loss & Grief.Cunsolo, A.; Kandman, K. (Eds). McGill Queen’s University Press, Canada. 2017. Xii.

- Cunsolo, A. Introduction, to mourn beyond the human. In Mourning Nature: Hope at the Heart of Ecological Loss & Grief.Cunsolo, A.; Kandman, K. (Eds). McGill Queen’s University Press, Canada. 2017. 3-26.

- Yu, L.; Zhong, S.; Vihma, T.; Sun, B. Attribution of late summer early autumn Arctic sea ice decline in recent decades. npj Clim Atmos Sci 2021, 4 (3) https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-020-00157-4.

- Walsh, J.E. Intensified warming of the Arctic: Causes and impacts on middle latitudes. Glob. Planet. Change 2014, 117. 52-63. [CrossRef]

- Rantanen, M., Karpechko, A.Y., Lipponen, A. et al. The Arctic has warmed nearly four times faster than the globe since 1979. Nat. Commun Earth Environ, 2022, 3, 168 https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-022-00498-3.

- Greene, C.A., Gardner, A.S., Wood, M. et al. Ubiquitous acceleration in Greenland Ice Sheet calving from 1985 to 2022. Nature,2024, 625, 523–528. [CrossRef]

- Bochow, N., Poltronieri, A., Robinson, A. et al. Overshooting the critical threshold for the Greenland ice sheet. Nature 2023, 622, 528–536. [CrossRef]

- Khan, S., Kjær, K., Bevis, M. et al. Sustained mass loss of the northeast Greenland ice sheet triggered by regional warming. Nature Clim Change 2014, 4, 292–299. [CrossRef]

- Box, J.E.; Colgan, W.T. et al. Key indicators of Arctic climate change: 1971–2017. Env. Res. Lett. 2019, 14. [CrossRef]

- MacGreggor, J.A.; Colgan, W.T. et al. Holocene deceleration of the Greenland Ice Sheet. Science 2016, 351(6273). 590-593. [CrossRef]

- Vinther, B., Buchardt, S., Clausen, H. et al. Holocene thinning of the Greenland ice sheet. Nature 2009, 461, 385–388. [CrossRef]

- Felikson, D., Bartholomaus, T., Catania, G. et al. Inland thinning on the Greenland ice sheet controlled by outlet glacier geometry. Nature Geosci 2017, 10, 366–369. [CrossRef]

- NASA Earth Observatory. Shrinking Margins of Greenland. Image URL https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/147728/shrinking-margins-of-greenland.

- Sumata, H., de Steur, L., Divine, D.V. et al. Regime shift in Arctic Ocean sea ice thickness. Nature 2023, 615, 443–449. [CrossRef]

- Hirawake, T.; Uchida, M. et al. Responses of Arctic biodiversity and ecosystem to environmental changes: Findings from the ArCS project. Polar Science 2021, 27. 100533. [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, D.E.; Lauth, R.R. Latitudinal trends and temporal shifts in the catch composition of bottom trawls conducted on the eastern Bering Sea shelf. Deep Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography. 2012. 65-70. 251-259. [CrossRef]

- Matsuno, K.; Yamaguchi, A. et al. Seasonal changes in mesozooplankton swimmers collected by sediment trap moored at a single station on the Northwind Abyssal Plain in the western Arctic Ocean. J. Plankton. Res. 2014, 36, 490-502. [CrossRef]

- Elmendorf, S.C.; Henry, G.H.R. et al. Global assessment of experimental climate warming on tundra vegetation: Heterogeneity over space and time. Ecol. Lett. 15. 164-175. [CrossRef]

- Ingvaldsen, R.B., Assmann, K.M., Primicerio, R. et al. Physical manifestations and ecological implications of Arctic Atlantification. Nat Rev Earth Environ 2021. 2, 874–889 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Chan, F.T.; Stanislawczyk, K. et al. Climate change opens new frontiers for marine species in the Arctic: Current trends and future invasion risks. Glob. Change Biol. 2019, 25. 25-38. [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Baquerizo, M., Guerra, C.A., Cano-Díaz, C. et al. The proportion of soil-borne pathogens increases with warming at the global scale. Nat. Clim. Change. 2020.10, 550–554 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Grémillet, D.; Descamps, S. Ecological impacts of climate change on Arctic marine megafauna. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2023. 38(8) 773-783. [CrossRef]

- MacNeill, M.A.; McMeans, B.C. et al. Biology of the Greenland shark Somniosus microcephalus. Fish Biol. 2012, 80(5). 991-1018. [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.E.; Hiltz, E. et al. Advancing Research for the Management of Long-Lived Species: A Case Study on the Greenland Shark. Front. Mar. Sci. 2019. 6. [CrossRef]

- Post, E., Forchhammer, M. Living in synchrony on Greenland coasts?. Nature 2004, 427, 698 (2004). [CrossRef]

- Wilson, S.F. Crosing, W. et al. Nested population structure of threatened boreal caribou revealed by network analysis. Glob. Ecol. Conserv 2022, 40, e02327. [CrossRef]

- Neilson, E.W.; Castillo-Ayala, C. et al. The direct and habitat-mediated influence of climate on the biogeography of boreal caribou in Canada. Clim. Change Ecol. 2022, 3. 100052. [CrossRef]

- Maltman, J., Coops, N.C., Rickbeil, G.J.M. et al. Quantifying forest disturbance regimes within caribou (Rangifer tarandus) range in British Columbia. Nat. Sci Rep 14, 6520 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Hermann, T.M.; Sandström, P. et al. Effects of mining on reindeer/caribou populations and indigenous livelihoods: Community-based monitoring by Sami reindeer herders in Sweden and First Nations in Canada. The Polar Journal. 2014. 4(1). 28-51. [CrossRef]

- Raitio, K.; Allard, C.; Lawrence, R. Mineral extraction in Swedish Sápmi: The regulatory gap between Sami rights and Sweden’s mining permitting practices. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 1050001. [CrossRef]

- Huijbens, E.H. The Arctic as the Last Frontier: Tourism. In Global Arctic. Finger, M.; Rekvig, G. (eds) 2022. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Gren, M.; Huijbens, E. (Eds). Tourism and the Anthropocene. Routledge, London, UK. 2015.

- Steffen, W.; Boradgate, W. et al. The trajectory of the Anthropocene: The Great Acceleration. The Anthropocene Review 2015, 2(1), 1-18. [CrossRef]

- Ren, C.; Jóhannesson, G.T.; Van Der Duim, R. Tracing tourism with Bruno Latour: Actor-network theory, critical proximity and down to earth. Tourism Geographies 2023, 25(5). 1297-1302. [CrossRef]

- Rantala, O.; Höckert, E. et al. Proximity and tourism in the Anthropocene. Ann. Tour. Res. 2024, 105. 103733. [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, A. Emplacing non-human voices in tourism research: The role of dissensus as a qualitative method. Tourism Geographies. 2021. 23(1-2). 118-143. [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, A. Does nature matter? Arguing for a biophysical turn in the ecotourism narrative. J. Ecotour. 2019. 18(3). 243-260. [CrossRef]

- Stavans, L.; Ellison, Ellison, J. Reclaiming Travel. Duke University Press, USA. 2015.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).