1. Introduction

Many global economies face significant long-term fiscal challenges that are likely to jeopardize the delivery of essential projects and public services in the future (Evenett, 2019). Thus, several governments have adopted creative financing solutions and a stricter fiscal discipline. Over the past few years, both federal and state governments have shown renewed interest in “public-private partnerships” (PPPs), as a way to the provisioning of public assets and services across the sector (Bayliss & Waeyenberge, 2018). The PPP model, particularly in developing economies, is most commonly used in infrastructure projects and involves the sharing of risks and rewards between public and private sector investors.

Given the multidimensional nature of PPPs, academics have been studying them from several perspectives, including economic, financial, engineering, political, governance, and sociological (Baker et al., 2019). Surprisingly, despite the rising popularity of PPP projects globally, academic research on their myriad dimensions is sparse within the broad realm of management studies (Zhang et al., 2020). In fact, even fewer studies have focused on the economic drivers of PPPs from the perspective of ‘expected returns’. Additionally, empirical studies on the determinants of financial risk in PPPs, interrelationships between risk-related elements in PPPs, and their relationship with the extent of private investments in projects have also been rare (Zhang et al., 2020). We attempt to address these gaps in the literature.

In the following sections, we first provide an overview of the function and scope of PPPs, followed by a brief literature review, and then discuss the role of risk relationships in PPPs, vis-à-vis the need for the study. We then identify and discuss the variables included in our research model, highlight issues within the general framework of our research, and present our hypotheses. Next, we discuss our methodology, present our findings, discuss the implications of our findings, and conclude by noting the limitations of our study, as well as avenues for future research in this area.

2. Function and Scope of PPPs

PPP is a contractual arrangement between a public agency and a private sector entity in which the skills and assets of each sector are pooled together to deliver a service or facility for the public good. Interestingly, there is no internationally accepted definition of PPPs. The World Bank Group of affiliated entities defined it as "a long-term contract between a private party and a government entity, for providing a public asset or service, in which the private party bears significant risk and management responsibility, and remuneration is linked to performance" (World Bank, 2014). Standard and Poor's (2005) definition of PPP states that ‘any medium- to long-term relationship between the public and private sectors, involving the sharing of risks and rewards of multisector skills, expertise, and finance to deliver desired policy outcomes’. However, when properly structured and managed, PPPs can help finance and deliver large-scale infrastructure projects that might otherwise not be feasible for governments to fund and execute independently (Gansler & Lucyshyn, 2016). Successful PPP projects arguably provide "value for money" (VFM), where VFM is construed as an optimal combination of quantity, quality, features and expected cost over the life of the project (Almarri & Boussabaine, 2017). An OECD literature review that compared the ex-post performance of successful PPPs to traditional infrastructure procurement in terms of the actual cost and time required to launch operations found that PPPs effectively outperform traditional procurement in terms of both, with outperformance on cost being the most significant (OECD, 2011). There are several reasons for this: successful PPPs allocate risks to parties that are best able to control or mitigate risks. This enables governments to focus on their role as service providers, as opposed to developers, while mitigating most of the state’s risks. Hodge and Greve (2017a) asserted that a PPP structure requires: (a) private financing because public finance is either unavailable or politically unattractive in meeting the government’s infrastructure policy projects; (b) with private financing, the private sector has an incentive to become fully engaged in the project, and the structure is, therefore, an effective way to secure a project over its long life, on time, and on budget. Another study by Trebilcock and Rosenstock (2015) indicated that although PPPs are more efficient than the traditional procurement methods used by the public sector, there is evidence of improvements in efficiency when private sector involvement is mixed. These studies have called for further empirical research to better understand the efficacy of PPP projects.

The PPP model is unique because a contract underpins the relationship between government and private parties, known as a "special purpose vehicle" (SPV), which refers to a company that is legally and specifically incorporated into the project (Burke and Demirag, 2019). A contract is usually drawn in the form of a concession agreement or a take agreement defining the rights and responsibilities of both parties as well as revenue-sharing mechanisms. The functions for which the private party is responsible can vary depending on the type of assets and services involved. Typical PPP functions involve design (engineering), construction and rehabilitation, financing, operations, and maintenance (Ye 2009).

There is a huge need for arguments regarding the use of PPPs. For instance, the McKinsey Global Institute forecasted that the world would need to invest an average of $3.7 trillion in roads, railways, ports, airports, power, water, and telecoms, every year through 2035, to keep pace with the projected GDP growth, especially with emerging economies accounting for nearly two-thirds of that investment need (Hussain et al., 2019). The European Court of Auditors (2018) reported that since the 1990s, about 1,750 PPPs worth a total of €336 billion had reached financial closure in the EU, with the UK leading the way, with over 700 PPP transactions. Within the same time frame, over 280 PPP projects worth CAD$130 billion were executed in Canada (Siemiatycki, 2015). Interestingly, the U.S., in contrast, used PPPs in a limited manner. However, its potential is huge, given the country's massive and growing unfunded infrastructure needs. According to the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE, 2013), the cumulative infrastructure investment needs in the U.S. alone are projected to be worth approximately $10 trillion by 2040. Of this, anticipated funding would cover only about half of this needed investment, leaving thereby an estimated private sector financing requirement of about $4.7 trillion by 2040. It may be reiterated that both the scale and scope of investment in PPPs are not limited to developed countries. A World Bank report (2020) estimated that between 1990-2020, approximately 8,300 PPP projects in developing nations alone garnered approximately $1,980 billion in private sector investments. Because of this, multilateral institutions such as the OECD, World Bank, Asian Development Bank, International Finance Corporation, ASEAN, and European Commission have all been broadly advocating the PPP concept. The PPP Knowledge Lab, recently established by the World Bank, supports this advocacy (World Bank, 2021). Collectively, these compelling statistics, along with continued institutional support, argue that PPPs will play a greater role in global infrastructure development over the next several decades.

3. Need for the Study

Most studies in the field of Management have either been descriptive in nature (Hodge & Greve, 2017), or have comprised a compilation of literature reviews (Cui et al., 2018; Neto et al., 2016), or focused on a single dimension of PPPs (e.g., ‘VFM’) (Palaco et al., 2019). Neto et al. (2016), while conducting a comprehensive bibliometric analysis of 600 papers relating to PPPs and PFIs (private finance initiatives), published between 1990 and 2014, found that PPP studies appear to have steady momentum towards growth, but primarily in engineering or law journals. Approximately two-thirds of the papers in that study (Neto et al., 2016) were authored by researchers based in Europe and Asia, covering aspects such as design implications or contractual obligations. This establishes that research on broader Business Management issues has indeed been limited while reinforcing that growing economies should also be considered (Osei-Kyei & Chan, 2015).

The limited management research available thus far on understanding the effectiveness of a PPP model as a tool to deliver public services efficiently has yielded mixed results. One possible reason for this could be that the success of a PPP project depends on several interrelated factors, such as the structure of the PPP deal, type of asset and sector, sophistication of PPP regulations, and governing institutions in the country where the projects are being delivered, and the PPP experience of the parties involved, among others (PPI report 2019). Very few comprehensive empirical studies have provided a more encompassing and compelling argument for the performance of PPPs (Vecchi et al., 2022). Governments around the world continue to consider the adoption of PPPs; however, there is an obvious need to address these knowledge gaps, both in terms of understanding PPP elements and PPP performance (Rybnicek et al., 2020).

Researchers recognize that each PPP project is unique and deeply embedded within its local context. However, common critical factors determine their success and are often marked by similar experiences across multiple projects and national boundaries. These commonalities could provide a basis for broader PPP studies (Palcic & Siemiatycki, 2019). A recent literature review (Cui et al., 2018) concluded that most existing studies on PPPs in the management stream could broadly be categorized into economic viability and VFM, financing of PPP projects, PPP success factors, determinants of the award of PPP contract management, and governance and regulatory issues. The interplay between the risk relationships among PPP parties has not been explored in depth (Khahro et al., 2021). Using social network analysis tools, Wang et al. (2018) conducted a comprehensive review of papers published in public administration journals and obtained similar results.

Thus, we take a deep dive into the specifics of risk relationships among several PPP elements within India while controlling for extraneous risk factors such as cross-border effects. Specifically, we examine embedded subsidies, risks related to bid criteria, the level of risk assumed by the two parties during the life of a project, and financial risk (leverage in the capital structure). India was selected for 2008–2012 and was the top recipient of PPI activities (Mishra et al., 2013). In 2011, India alone accounted for almost half of the investments in new PPI projects in developing countries. This was the result of regulatory and institutional initiatives undertaken by relevant government institutions to support changes in public policy. According to a Report of the Committee on Revisiting and Revitalising Public Private Partnership Model of Infrastructure (2015), commonly referred to as the ‘Kelkar Committee Report’, "India offers today the world's largest market for PPPs … As the PPP market in infrastructure matures in India, new challenges and opportunities have emerged and will continue to emerge." More importantly, the report noted: "the dominant, primary concern of the Committee was the optimal allocation of risks across PPP stakeholders. Inefficient and inequitable allocation of risk in PPPs can be a major factor in PPP failures… The Committee noted that the adoption of the Model Concession Agreement (MCA) has meant that project implementation authorities rarely address project-specific risks in this ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach." Periodic studies across countries, including India, are therefore needed to address any issues that may arise as a consequence of policies put in place to ensure the success of the PPP model. This study contributes to the literature in this direction.

4. Literature Review

4.1. PPPs and Risk

Brown et al. (2016) stated that, in general, risks should be borne by the party that can carry them at a minimal cost. Our review of the literature on risks in PPPs shows that it has mainly focused on specific case studies, sectors, and/or regions. For example, Carbonara et al. (2015) focused their review on risk management in motorway PPPs, while Hellowell (2016) looked at the cost-benefits of PPP structures in healthcare infrastructures. Callens et al. (2022) studied PPP structures in transportation infrastructure, whereas Alam et al. (2014) studied generic trends in PPP in Australia. Sarmento and Renneboog (2016) examined the role of renegotiations in PPP contracts, while Warsen et al. (2018) explored specific risk-related factors such as the role of trust. Other studies on risks in PPPs have focused either on simply identifying general risk factors (Li & Wang, 2019), risk allocation issues (Ke et al., 2010a; Nguyen et al., 2018), or on ways to undertake a risk assessment (Li & Zou, 2011). A recent study (Rybnicek et al., 2020) identified genetic risk factors in PPPs while conceptually relating them to risk-management frameworks. Interestingly, no ‘in-depth’ studies (conceptual or empirical) have explored the relationships between the multiple elements of risk embedded in PPP structures (Hu & Hooy, 2022). It may also be noted that extant research seems to have been bifurcated in terms of its focus on either private or public institutions, without giving equal consideration to their partnership and risk interdependencies. Researchers have long advocated for a partial merger of the two research streams on the grounds that private and public interests cannot be holistically studied if conceived independently (Mahoney et al., 2009). Based on some of these gaps and limitations identified in the literature, we examine the interrelationships between multiple PPP risk elements from the viewpoint of both private investors and public participants. We believe our exploration would provide a holistic insight in terms of understanding how risks embedded in structural elements (e.g., subsidies provided by the public partner) or process elements (e.g., bid criteria for evaluating competitive bids) effectively relate to investments made by private sector participants. This would help PPP managers better understand the impact of risk interrelationships, such that project structures can be tweaked to best position all parties to work towards a common goal of ensuring project success.

4.2. Hypotheses Development

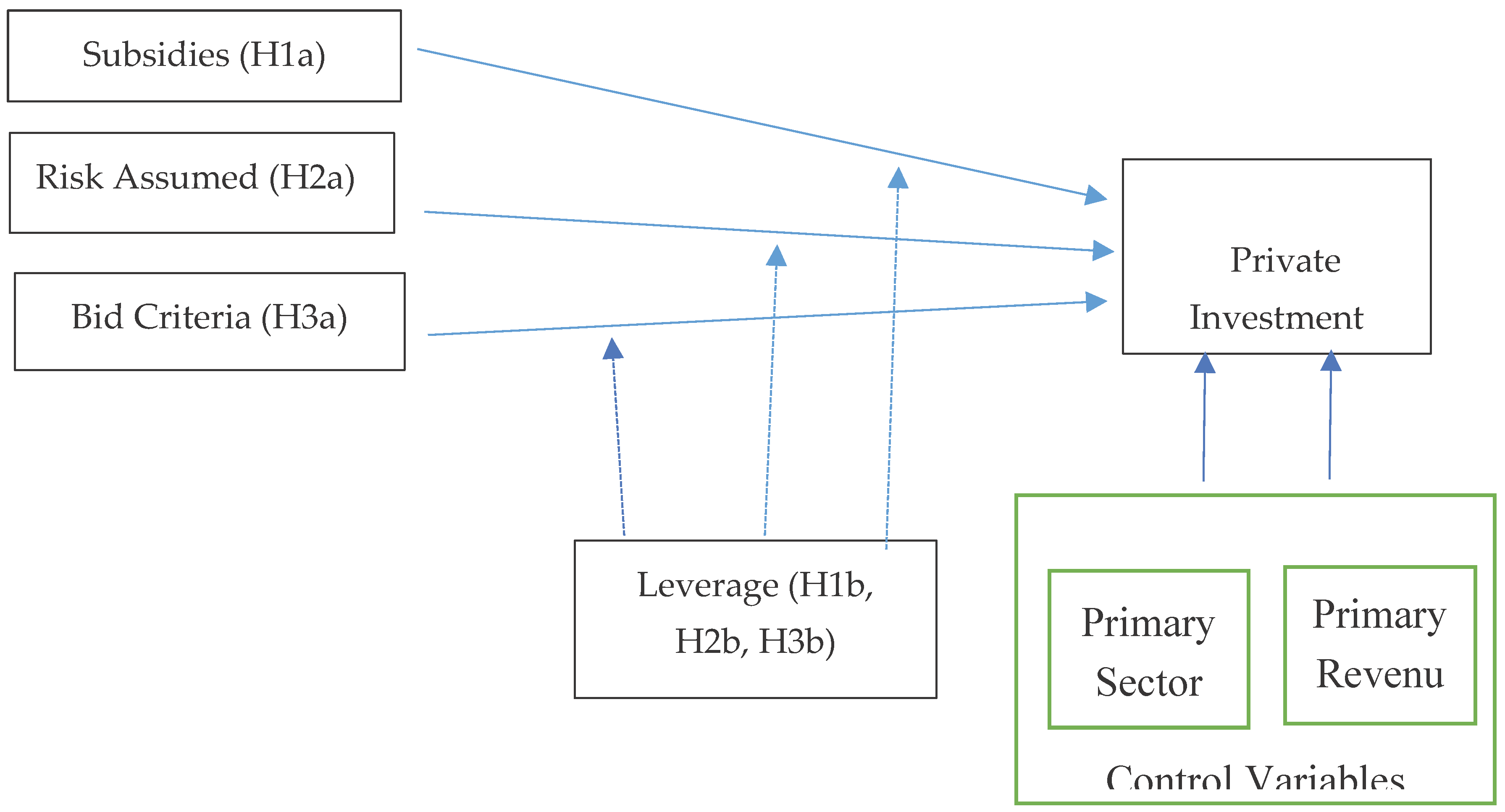

In this section, we present a theoretical model to study the four PPP structural elements from a common perspective of ‘embedded financial risk’ to better understand whether these elements are related and how much equity private investors are willing to put into PPP projects. We present hypotheses linking the three independent risk-related variables. They include Subsidies (S) provided by the public sector partner, Risk Assumed (RA) by the private sector partner, and the Bid Criteria (BC) applied by the public sector to the dependent variable - the level of Private Investment (PI) in a PPP project. Also, we propose a fourth risk variable, i.e., financial leverage (FL), which would serve as a moderating factor in these relationships. We then test our hypotheses using data from an extensive World Bank database and present the results.

4.2.1. Moderating Role of Leverage in PPPs

The relationships among subsidies, assumed risk, bid criteria, and the extent of private investment are affected by the amount of leverage in the capital structure of the SPV (Hu & Hooy, 2022). It may be noted that PPP project financing normally consists of a mix of equity provided by private investors, loans provided by banks or other financial institutions, and issuance of debt such as bonds. Equity providers refer to private investors and shareholders in SPV; they receive their returns only after payment of operating costs, capping of required financial reserves, and servicing costs associated with debt. Furthermore, they absorb the first loss when there is a shortfall in the contract payments and/or increased operational costs. Like most capital financing, equity investors take a higher risk than debt providers, owing to which they expect higher returns.

In PPPs, leverage is determined by a number of risk factors such as country and political risk, the risk of technology reliability that would be employed for the project, and credit ratings of equity providers, among others (Wang et al., 2019).

Project financing in PPP is often considered ‘limited-recourse financing because lender security is normally limited solely to the project's cash flows. On the other hand, the sponsor’s equity invested in SPV is effectively ring-fenced from the rest of the sponsor's business interests. Therefore, there is a clear management focus on the full transparency of cash flows throughout the life of the project. Notably, sponsors do not guarantee the project as a whole; lenders, on the other hand, rely primarily on the cash flow of the project for debt service. Because the sole recourse of debt providers is linked to the assets of the SPV and because the physical assets in a PPP (e.g., a road or an airport) have little value if they are not used in the context of the project, the main assets that lenders tend to rely on, as security, are the contract between the public authority and the private sector project entity, including the cash flows derived from this contract. As a result, SPV may also be subject to several restrictive and affirmative covenants, such as restrictions on sale of assets, restrictions on incurring additional debt backed by SPV assets, interest rate hedges, and requirements to provide periodic compliance reports. Thus, in a typical PPP project, the greater the financial leverage in the capital structure, the greater the expected level of private investment. Thus, there is a need to study the unique moderating role of leverage in the risk relationships among Indian PPPs.

4.2.2. Subsidies and Private Investments (PI)

There are many implicit ways to financially help a PPP project, usually in terms of providing subsidies, concessional loans, guarantees, or paying for project preparation; however, ‘subsidies’ is most common way. In theory, subsidies to PPPs serve a single purpose: to make sure projects that will produce a net economic or social gain can be commercially financed" (World Bank Institute Report, 2019). One reason why Subsidies are popular because they can be structured in several ways, depending on the cash flows of the project. At times, governments provide subsidies by making upfront cash contributions to pay the capital costs. This is the case when partners agree that the project might not be financially viable but is required for the delivery of social goods. On the other hand, governments can make regular subsidy payments to private companies based on both the availability and quality of the service, albeit as a function of the expected revenue stream over project life (pppinindia.gov.in, 2020). Another reason for offering subsidies is to invite broader private participation in the project bid. Generally, when subsidies are offered, other private investors (those with no other contractual relationship with the project) are incentivized to align with the primary private partner to ensure that the PPP project is viable and succeeds. The literature on the relationship between government support subsidies focuses primarily on the elements of government policies that support PPP project performance, the level of private investment (Osei-Kyei & Chan, 2017; Silaghi & Sarkar, 2021), and/or whether both loans and subsidies influence the structure of PPP projects (Vecchi et al., 2022).

Based on the above findings, one would assume that there would be a positive relationship between the subsidy provided and total private investment; the greater the subsidy, the more private investors (s) would be incentivized to invest in the PPP project. Conversely, one can argue that if the subsidy is relatively high, it probably means that the public partner has predetermined the cash flows from the project and is suspected of the economic viability of the PPP. In such cases, the primary private investor would not need to invest as much, would be less accountable, and may be willing to walk away if the project does not generate adequate returns. For example, a recent study used principal-agent theory to show that while government subsidies are related to expected revenue and costs, governments' altruism in terms of providing subsidies can undermine investors' enthusiasm in terms of cooperation and risk-sharing propensity (Wang et al., 2020). For the private partner, the investment made comes from its own balance sheet, combined with funding from ‘other investors’ (e.g., private equity, investment banks) who help capitalize on the transaction. Based on this understanding, subsidies should ideally be structured in light of the projected cash flows from the PPP but should be kept under consideration of both the scope and leverage of private investment (Farquharson et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2019). A detailed study of subsidies (provided through ‘Viability gap fund’ VGF) in India reveals that private players benefit greatly from subsidies and contribute a very low percentage of equity funding (World Bank report, 2014).

The VGF program may not be ideal, and certainly has some drawbacks or questionable criteria. However, given the enthusiasm for and sheer number of private sector participants in PPP projects in India, our position is that the provision of subsidies to PPPs in India has generally been successful. Interestingly, the Kelkar Committee Report of 2015 held a similar stance. However, they made multiple recommendations to rectify the issues associated with the provisioning of subsidies in Indian PPPs.

From a financial perspective, the certainty of government support programs such as the VGF could decrease risk in the private sector, incentivizing it to make more investments (Urpelainen & Yang, 2017).

Table 1a and

1b outline the distribution of the percentage of subsidies received across 136 PPP projects in India and the nature of risk associated with each PPP model (i.e., risk assumed).

The distribution is evenly spread, although many projects received subsidies in the range of 31-40%. We also noticed that within this range, almost all the projects received the maximum subsidy–40%–as capped under the Indian government policies for VGF. From these observations, it can be concluded that the public sector probably engages in some sort of revenue projection (even though these are not made publicly available) to decide on the amount of subsidy to be awarded to a PPP project. Moreover, this also leads us to believe that a significant number of PPP projects in India would probably not be economically viable on their own. Thus, subsidies in the form of VGF are essential for substantial Private Investment (PI) to take place in Indian PPPs. Furthermore, it may be noted that the provision of subsidies shows commitment from the public sector; in addition, it incentivizes private sector players to bid on the project and to have more skin in the game. Notably, the amount of external support (or leverage in the project) influences the relationship between subsidies and the PI. Subsidies, PI, and funding from third-party providers (which impact leverage) shall, taken together, determine the final capital structure of the project. Therefore, we propose that the amount of private investment in Indian PPP projects is positively related to the overall subsidies provided. Additionally, this relationship is moderated by leverage in transactions. This leads us to propose our first set of hypotheses.

H1(a): Subsidies and Private Investment (PI), in Indian PPPs will be positively related.

H1(b): Leverage would moderate the relationship between Subsidies and Private Investment (PI).

4.2.3. Risk Assumed (RA) and Private Investment

Risk Assumed (RA) is inherently difficult to deal with, and risk allocation within PPP projects is particularly complicated. Governments floating tenders for a PPP project typically state their preferences upfront as to how project risks are shared. Private investors then assess their capacity to take risks and bid accordingly (Warsen et al., 2018). Theoretically, ‘risk’ should be allocated to the party that can best manage it at minimum cost (Leo-olagbaye and Odeyinka, 2020). Notably, in a PPP contract, the optimal risk allocation strategy is not to pass all risks to the private sector but to do so in a manner that there is a fine balance between efficient management and total costs to both the public and private sectors. However, in practical terms, extant research shows that the private sector usually ends up taking the most risks at the project level (Mazhar et al., 2020).

At one end of the risk assumption spectrum, where the PPP project may be in the form of a ‘service contract’ or ‘delegated management contract’, the private sector partner assumes minimal risk. In a service contract, the private sector provides support, but the public sector is responsible for operations. In fact, the private sector does not influence how services are distributed, although to a certain extent, it is dependent on the public sector for generating profits. Delegated management contracts, on the other hand, are similar in that the public sector retains the overall ownership of assets, but delegates operational responsibility to private investors. However, the most wide-ranging form of PPP contract requires the private operator to be involved in the design and construction phases of the new infrastructure. In these cases, the risk to private players is relatively high and varies because of the various types of involvement. In India, the four most common forms of PPP contracts are – built-operate-transfer (BOT), build-own-operate (BOO), build-rehabilitate-operate-transfer (BROT), and rehabilitate-operate-transfer (ROT). Brief descriptions of these four types of arrangements in terms of project design and construction elements and the associated degree of risk assumed by the private sector partner are shown in

Table 2.

In almost all cases, private investments in Indian PPPs come from (a) private developers and concession operators (the ‘private sector partner’s partner) and (b) supporting partners that provide funding, such as banks, other financial institutions looking to invest, and indirect investors. Therefore, one would expect that the higher the risk assumed by the private sector partner, the lower the level of financial support that third-party lenders (banks, financial institutions, and other investors) would be willing to contribute to the capital structure to minimize their risk exposure in the project. In addition, high investment by the private sector partner should incentivize the private player to do everything to make the project successful.

Because Indian PPPs involve varying amounts of assumed risk wherein the exact nature of inherent risks is significantly unknown at the time of initiation of the project, public partners and the Indian Government have often struggled to forge new, successful partnerships with private players. The Kelkar Committee report pointed out: "attempts to improve well-defined expected service outcomes and equitable sharing of risks has met with limited success." Since project offerings are not explicitly tied to assumed risk, they compete more on the basis of governmental policies and standard contracts across sectors, and under conditions of expected but unknown cash flows, as well as associated subsidies, the amount of which is decided primarily by the public partner. We posit that the risk assumed by private investors would be closely analyzed, and cash flows would be projected across multiple scenarios, with investments made accordingly. Furthermore, it may be noted that when the broad private investor group (lead investors and supporting investors) reaches a consensus regarding the amount of investment that needs to be made by the private sector partner, as well as the amount of leverage required in the project, which will be acceptable to all participants in the private consortium. This discussion leads to our second set of hypotheses.

H2(a): Risk Assumed (RA) and Private Investment (PI), in the context of Indian PPPs, will be positively related.

H2(b): Leverage will moderate the relationship between Risk Assumed (RA) and Private Investment (PI).

4.2.4. Bid Criteria and PI

In PPPs, there are several types of procurement options, viz., bid criteria to choose a winning bid, and they are made known by the public sector party before inviting the bids. Bids can be invited using an open procedure, wherein everyone is allowed to bid, and they can also be made via selective or restrictive procedures that involve an additional pre-qualification step. However, in some cases, the invitation to bid might be offered only to a select group of bidders, an option known as ‘limited procedure’. Other procurement options could be through a ‘negotiated procedure’ that allows bidders to propose different solutions, which are then negotiated to reach a best-and-final-offer ("BAFO") for evaluation purposes.

Importantly, when only one bid criterion is involved, such as the lowest average tariff, royalty, subsidy, or net present value (NPV), the evaluation process for bids is quite straightforward. However, when there is more than one bid criterion, this issue becomes more complex. This may call for a multi-criteria decision analysis to select the winning bid. World Bank data show that PPPs in India essentially use one of the four types of bid criteria (given in

Table 3); the four types of bid criteria contain varying degrees of risk.

Importantly, when the bid criterion is the ‘lowest cost of construction or operation,’ the private partner asserts that it can deliver the project at the lowest cost from construction to the end of the operation. In other words, it promises to provide the most value for money (VFM). However, risk-sharing plays a fundamental role in determining whether a PPP would yield VFM. This is a key mechanism to ensure that a private partner performs as efficiently as possible. A good measure for the VFM criteria is to compare the net present value (NPV) of various bids (Tallaki and Bracci, 2021), which private players more commonly use. For the public partner, cost-benefit analysis (CBA) or cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) is more appropriate. In the CBA approach, both benefits and costs are quantified to a large extent in monetary value, whereas the CEA approach is primarily a cost-minimization technique. Importantly, both CBA and CEA consider a broader socio-economic assessment and the net contribution of an activity or project to overall benefits. They are relatively more complicated in PPP projects, in which most benefits cannot be readily monetized (Sdoukopoulus et al., 2019). Under this ‘lowest cost of construction or operation’ bid criterion, the public sector partner carries minimal risk, whereas the level of risk carried by the private sector partner is high; but it could vary, depending on its knowledge-base and experience, ability to take advantages of economies of scale, and managerial skills over the entire life-cycle of the project from design stages to end of the concession period.

Specifically, when the bid criterion is ‘lowest government payments’ into the PPP project, the primary risk for the private party alludes to a political risk. Thus, the bid is made under the assumption that the public partner would deliver on its commitments in terms of issues such as timely acquisition and deliverance of land, shifting of utilities, and right-of-way issues and that the project would proceed fluidly without any major interruptions, project-related scandals, or other delays that might add uncertainty to the expected cash flows from the project. Importantly, the risk to private partners is fairly high because there are multiple ways in which a PPP project might be delayed. On the other hand, the risk to the public partner is relatively low because the key criterion is the lowest payment commitment. If the bid criterion is ‘lowest subsidy required’ by the private partner from the public partner, the risks to the private party are primarily in the construction phase and in the form of financing risk. An inadequate upfront subsidy can result in a higher financing risk or total cost to the private party, and if the subsidy is delayed, the cost of capital can be much higher. Therefore, under these bid criteria, the risk to the private partner is relatively high, and the risk to the public partner is relatively low. On the other hand, when the bid criterion is the ‘lowest average tariff’ charged by the concessionaire, the primary risk includes demand risk. In the context of Indian PPPs, in the absence of substantiated cash flow projections, the public sector has historically often underestimated tariff revenues to the private sector from PPPs, resulting in a substantial loss of ‘potential revenues’ to the public sector. This is evident from several case studies of Indian PPPs, such as those on the now-defunct Delhi Gurgaon Tollway (Delhi and Mahalingam, 2020; Kudtarkar, 2020). In other words, demand risk is usually low for private partners, whereas the risk of losing out on project upside benefits, such as potential revenue, is high for public partners.

We posit that the greater the amount of risk related to the bid criteria, the higher the private investment required by private players, and leverage moderates this relationship. Therefore, we hypothesize as follows:

H3(a): In India-based PPPs, there is a significant and positive relationship between Bid Criteria (BC) and Private Investment (PI).

H3(b): Leverage will moderate the relationship between Bid Criteria (BC) and Private Investment (PI).

4.2.5. Conceptual Model

Our model tests the relationship among subsidy, assumed risk, bid criteria, and private investment (PI), which is a dependent variable. PI is a key component of PPPs and is especially significant in emerging markets. Without the support of private players, governments often find it difficult to develop infrastructure projects. Governments in emerging markets such as India are, therefore, highly incentivized to provide all kinds of direct and indirect support to private investors. A high PI can be used as a surrogate measure of project attractiveness. It also represents a commitment to and confidence in the success of a PPP from the private partner's perspective. We controlled for the sector in which these projects were operational, as well as for primary revenue sources (Wang et al., 2019), to enhance the internal validity of the study (Becker, 2005).

We considered leverage as the moderating variable, and our empirical model proposes that leverage in the transaction would affect the relationship between assumed risk, bid criteria, subsidy, and PI. The empirical model tested is shown in

Figure 1.

5. Methods, Analysis and Results

This study used the World Bank Database for PPPs, comprising 10,450 global PPP projects from 1990 to 2019.

Table 3 summarizes the projects across the various variables of the conceptual model developed for this study.

Of these 10 K+ projects, 9583 were active, 380 were canceled, 226 were concluded, and 262 were distressed. These projects were spread across six regions: Africa, Latin America, South Asia, East Asia, the Middle East, North Africa, and East Europe. These projects include greenfield projects, brownfield projects, Divestitures, and Management and Lease contracts. The nature of investments in these projects covered a vast spectrum and fell into the following categories: Full Investment, Build-Lease-Transfer, Build-Operate-Transfer, Build-Own-Operate, Build-Rehabilitate-Operate-Transfer, Lease Contracts, Management Contracts, Rehabilitate-Lease-Transfer, Rehabilitate-Operate-Transfer, and Rental. We screened the entire database thoroughly to identify missing values. The data for 157 projects were complete. Most of these (N = 136) were PPPs based in India; of these, 112 projects operated as brownfield projects, whereas the remaining operated as greenfield projects. Since most of the projects (136 out of 157) were from India, we considered it appropriate to test the model for PPP’s in India only. The projects belonged to three sectors (Energy -5, Transport 128, and Water and Sewage 3), and the primary revenue sources for these projects included annuity (74), purchase agreement (3), and user fees (58). Both of these variables were controlled for, to restrict their impact on the outcome. The aim was to understand the impact of predictor variables on the dependent variables irrespective of the sector of the project and revenue sources.

Four types of models were used to finance these projects: the Rehabilitate Operate Transfer (ROT) model (six projects), Build Rehabilitate Operate and Transfer (BROT) model (106 projects), Build Own Operate (BOO) model (seven projects), and Build Operate Transfer (BOT) model 38 projects. Additionally, these projects were categorized as per the ‘bid criteria’ used to finance them – ‘lowest cost of construction or operation' (59 projects), ‘lowest government payment (27 projects), ‘lowest subsidy required' (66 projects); and ‘lowest tariff’ (5 projects). Table 5 shows the corresponding number of PPPs in India. All projects were funded through private investment, which is taken at its dollar value and serves as a dependent variable as per our model. Finally, based on the data given for debt and equity funding for each project, we calculated leverage and categorized them as follows: low-leverage projects (leverage < 0.25), moderately leveraged projects (leverage between 0.26 and 0.5), and highly leveraged projects (leverage > 0.5). We calculated the ‘leverage’ using a standard formula of debt as a proportion of total capital (debt and equity). The subsidy in a project was calculated by deducting equity and debt investments from the project's total investment. Projects were mapped against the percentage of subsidy received for the project (i.e., the funding gap received after debt and/or equity funding for the project).

The study sought to investigate the relationship between the predictors - Risk Assumed, Subsidy, and Bid Criteria with Private Investment (PI) as the dependent variable and leverage as the moderating variable. The data was analyzed using SPSS 24 and PROCESS macro. The overall regression is significant for this model (R2 = 0.453). The value of the adjusted R2 was 0.416, which shows that 41.6% of the variance was accounted for by the following predictors: BC, Subs, and RA collectively (F(5, 131) =8.76; p<0.000). The F value was 8.760 at p ≤ 0.000, indicating that the overall regression was significant. The predictor variables forecasted the response variable PI as the beta values were significant (

Table 4a and

4b).

Next, we tested the moderating effect on the relationship between the predictor variables and PI, as shown in our research model. First, we test the impact of leverage on the relationship between subsidies and PI.

The interaction effect between leverage and the predictor was found to be significant in the case of subsidies and PI (beta = 178.30, SE = 77.35, and p = 0.0023). The moderating effect of leverage on this relationship was found to be both positive and significant, supporting Hypothesis (H1b). Second, the impact of leverage on the assumed risk and PI was analyzed; it was not found to be significant (beta = 44.54, SE = 55.88, and p = 0.4098). Finally, the moderating effect of leverage was observed on bid criteria and PI (beta = 85.12; SE = 81.71; p = 0.2994). The moderating effect was positive and insignificant in both relationships (

Table 5); these findings do not support Hypotheses (H2b and H3b).

Table 5 gives a summary of all the hypotheses for the moderating variable and their results. We explain the results in detail in the following section, and the implications for practice and research are discussed.

6. Discussion

We study financial risk-related factors in the context of PPPs in India and their relationship with the amount and extent of investments made by private partners (s). Our hypotheses posited relationships that may seem contrary to the commonly held notion of risk relationships. However, we framed our arguments in the Indian context given the country’s unique PPP landscape. Importantly, legal and regulatory frameworks often lack transparency in terms of cash flows (actual or projected) and the Indian Government’s motivation to incentivize private participation in these projects. Our results show that subsidies and private investments are directly related to Indian PPPs, and that leverage plays a moderating role in this relationship. Subsidies guiding investments in PPPs are strong in developing economies (Wang et al., 2019). As India is an emerging and fast-developing nation, government spending is huge and private participation is encouraged. To ensure the success of government projects, the private sector is incentivized by offering high subsidies. For example, the majority of the projects received subsidies between 31%-40% (69 projects), whereas 113 received subsidies between 11% and 40%. Thus, our understanding that the government uses VGF as a lever to attract private investment has emerged strongly. We also note that assumed risk and private investment are directly related and that leverage does not moderate this relationship. Furthermore, traditional thinking believes that in order to protect downside risk, the greater the risk assumed by the private partner, the lower the investment in the project. Our hypothesis argued for the contrary and found empirical support for our position. Interestingly, leverage does not act as a moderating factor in this relationship. There could be two reasons for this anomaly: (a) most projects belong to the BOT or BROT category, ensuring they are eventually transferred to the government. Therefore, although these projects would be risky (Wang et al., 2019), handing over the project to the government is a reasonable assurance that private players assume higher risk is unaffected by project leverage. b. Secondly, most of the projects belonged to sectors wherein either the central or the state government had focused on budgetary allocations and had set sectoral development targets. Sectors, such as ‘transport’ and ‘energy’, for instance, have received an immense boost from governments recently, motivating the private sector to take up higher risks despite higher leverage. Finally, we posit that bid criteria and private investment are directly related and moderated by leverage. Our findings support the former but negate the latter relationship. The support for the former relationships, that is, the nature of bid criteria, impacts private investment, has been posited in the literature and is evident in Indian PPPs; however, the relationship remains unaffected by project leverage. Although this finding is surprising, it can be explained by arguing that India is a fast-growing and emerging nation that attracts private investors who are willing to take risks, which are perceived to be less than the opportunities provided by the government across sectors, resulting in long-term growth prospects. We also validate this with the GDP figures and the FDI inflows during these years.

7. Conclusion

Empirical support for our findings is both interesting and significant. We conclude that subsidies are often a necessary condition for investment by private players in Indian PPPs, wherein leverage in total financing affects the total capital contribution. In the absence of sophisticated cash flow projection models and sensitivity analysis, the presence of subsidies is often a reassuring component that demonstrates the commitment of the public partner. In addition, from a broader and somewhat unique perspective, the private investor group looks at other financial risk factors, such as assumed risk, bid criteria, and leverage, and makes investment decisions that they believe are optimal given the overall assessment of project risk.

8. Contribution of the Study

Our findings contribute to the literature in several ways. First, we believe this is among the first studies to understand the relationships between risk elements and resultant private investment in India's PPPs. Our findings are critical for both private and public participants in terms of the financial considerations for PPP projects. We highlight that financial risk-related relationships are intricately situated within the context of a country’s PPP environment. Therefore, participants must contextualize the findings within their geographical and political contexts to understand what modes of financial commitment and risk-taking are appropriate for them. Third, although the literature emphasizes leverage as a significant moderator of these relationships, our findings do not completely support them. In turn, we highlight the reasons for this anomaly, and we believe that more empirical studies could further validate these findings.

9. Limitations of the Study

As in most empirical studies, this study has several limitations. First, we focused on India. Testing the hypotheses with data from other emerging economies will provide additional validation and generalizability to our findings. Second, the risks and challenges in developed countries may differ from those in developing countries. Additionally, the process or approach to managing risk in the two contexts might also differ. Therefore, further research is needed to understand the differences between developed and developing countries in terms of risk and risk management in PPPs. Third, we only considered financial risk factors; however, other risk-related factors, such as political risk, partner selection criteria, governance risk, currency risk, and repatriation risk, can impact financial risk relationships. Analyzing these factors in detail could provide helpful information for PPP project practitioners.

Author Contributions

Both the authors have contributed equally to this article.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data for this research has been accessed from the World Bank database for the Public Private Partnerships. Link for the website -

https://ppi.worldbank.org/en/ppi

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

References

- Alam, Q. , Kabir, M. H., and Chaudhri, V. 2014. "Managing infrastructure projects in Australia: A shift from a contractual to a collaborative public management strategy." Administration & Society, 46(4): 422–449. [CrossRef]

- Almarri, K.; Boussabaine, H. Interdependency of Value for Money and Ex-Post Performance Indicators of Public Private Partnership Projects. . 2017, 7, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engineers, A.S.O.C. Failure to Act; American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE): Reston, VA, United States, 2013. American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE): Reston, VA, United States, 2013; ISBN 9780784478783. [Google Scholar]

- Bayliss, K. , and Waeyenberge, E. 2018. "Unpacking the Public Private Partnership Revival." Journal of Development Studies. 54(4): 577-593.

- Baker, N.B.; Khater, M.; Haddad, C. Political Stability and the Contribution of Private Investment Commitments in Infrastructure to GDP: An Institutional Perspective. Public Perform. Manag. Rev. 2019, 42, 808–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, T.E. Potential Problems in the Statistical Control of Variables in Organizational Research: A Qualitative Analysis With Recommendations. Organ. Res. Methods 2005, 8, 274–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T. L., M. Potoski, and D. Van Slyke. 2016. "Managing Complex Contracts: A Theoretical Approach." Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 26(2): 294-308.

- Burke, R.; Demirag, I. Risk management by SPV partners in toll road public private partnerships. Public Manag. Rev. 2018, 21, 711–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callens, C.; Verhoest, K.; Boon, J. Combined effects of procurement and collaboration on innovation in public-private-partnerships: a qualitative comparative analysis of 24 infrastructure projects. Public Manag. Rev. 2021, 24, 860–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbonara, N.; Costantino, N.; Gunnigan, L.; Pellegrino, R. Risk Management in Motorway PPP Projects: Empirical-based Guidelines. Transp. Rev. 2015, 35, 162–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leo-Olagbaye, F.; Odeyinka, H.A. An assessment of risk impact on road projects in Osun State, Nigeria. Built Environ. Proj. Asset Manag. 2020, 10, 673–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, C.; Liu, Y.; Hope, A.; Wang, J. Review of studies on the public–private partnerships (PPP) for infrastructure projects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2018, 36, 773–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delhi, V.S.K.; Mahalingam, A. Relating Institutions and Governance Strategies to Project Outcomes: Study on Public–Private Partnerships in Infrastructure Projects in India. J. Manag. Eng. 2020, 36, 04020076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ECA (European Court of Auditors), 2018. "Public Private Partnerships in the EU: Widespread Shortcomings and Limited Benefits." Luxembourg: European Court of Auditors.

- Evenett, S.J. Protectionism, state discrimination, and international business since the onset of the Global Financial Crisis. J. Int. Bus. Policy 2019, 2, 9–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farquharson, E. , Mastle, C., Yescombe, E. and Encinas, J. 2011. "How to Engage with the Private Sector in Public-Private Partnerships in Emerging Markets." PPIAF, The World Bank.

- Gansler, J. , and Lucyshyn, W. 2016. "Public-Private Partnerships: Leveraging Private Resources for the Public Good.

- Government of India Report, 2005. "Scheme and Guidelines for Financial Support to Public Private Partnerships in Infrastructure," Ministry of Finance, Department of Economic Affairs, New Delhi, India.

- Government of India Report, 2015. "Report of the Committee on Revisiting and Revitalising Public Private Partnership Model of Infrastructure," Ministry of Finance, Department of Economic Affairs, New Delhi, India.

- Government of India. 2020. "Guidelines for Forwarding Proposals for Financial Support to Public Private Partnerships in Infrastructure under the Viability Gap Funding Scheme." Note F.No.1/4/2005-PPP, Ministry of Finance, Department of Economic Affairs, New Delhi, India.

- Hellowell, M. 2016. B: "The Price of Certainty.

- Hodge, G. , and Greve C., 2013. "Introduction: public-private partnership in turbulent times" in C. Greve and G. A. Hodge (Eds.), Rethinking Public-Private Partnerships: Strategies for Turbulent Times, Abingdon: Routledge, 1-32.

- Hodge, G. A. , and C. Greve. 2017a. "Private Finance: What Problems Does It Solve, and How Well?" In The Oxford Handbook of Megaproject Management, edited by B. Flyvbjerg, 362–388. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hodge, G. , and Greve, C. 2017. "Contemporary Public-Private Partnership: Towards a Global Research Agenda." Financial Accountability and Management 1-14.

- Hu, X.; Nor, E.; Hooy, C.-W. Optimal Capital Structure of PPP Projects: A Review of the Literature. J. Contemp. Issues Thought 2022, 12, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A. et al. 2019. "Unlocking Private-Sector Financing in Emerging Markets Infrastructure." McKinsey Insights article, October, McKinsey & Co.

- Ke, Y. , Wang, S., Chan, A. and Lam, P. 2010. "Preferred Risk Allocation in China's Public- Private Partnership (PPP) Projects." International Journal of Project Management, 28: 482-492.

- Khahro, S.H.; Ali, T.H.; Hassan, S.; Zainun, N.Y.; Javed, Y.; Memon, S.A. Risk Severity Matrix for Sustainable Public-Private Partnership Projects in Developing Countries. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudtarkar, S.G. Failure of Operational PPP Projects in India Leading to Private Developer’s Apathy to Participate in Future Projects: A Case Study Based Analysis. Indian J. Finance Bank. 2020, 4, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zou, P.X.W. Fuzzy AHP-Based Risk Assessment Methodology for PPP Projects. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2011, 137, 1205–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, X. USING FUZZY ANALYTIC NETWORK PROCESS AND ISM METHODS FOR RISK ASSESSMENT OF PUBLIC-PRIVATE PARTNERSHIP: A CHINA PERSPECTIVE. J. Civ. Eng. Manag. 2019, 25, 168–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sdoukopoulos, A.; Pitsiava-Latinopoulou, M.; Basbas, S.; Papaioannou, P. Measuring progress towards transport sustainability through indicators: Analysis and metrics of the main indicator initiatives. Transp. Res. Part D: Transp. Environ. 2018, 67, 316–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, J. McGahan, A. and Pitelis, C. 2009. "The Interdependence of Private and Public Interests." Organization Science, 20(6): 1034-1052.

- Mazher, K.M.; Chan, A.P.C.; Zahoor, H.; Khan, M.I.; Ameyaw, E.E. Fuzzy Integral–Based Risk-Assessment Approach for Public–Private Partnership Infrastructure Projects. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2018, 144, 04018111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.; Narendra, K.; Kar, B. Growth and infrastructure investment in India: Achievements, challenges, and opportunities. Èkon. Anal. 2013, 58, 51–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Castro e Silva Neto, D.; Cruz, C.O.; Rodrigues, F.; Silva, P. Bibliometric Analysis of PPP and PFI Literature: Overview of 25 Years of Research. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2016, 142, 06016002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Hua, Y.; Fu, Y. Impacts of risk allocation on conflict negotiation costs in construction projects: Does managerial control matter? Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2020, 38, 188–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.A.; Garvin, M.J.; Gonzalez, E.E. Risk Allocation in U.S. Public-Private Partnership Highway Project Contracts. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2018, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osei-Kyei, R. , and Cjan, A. 2017. "Factors Attracting Private Sector Investments in Public-Private Partnerships in Developing Countries." Journal of Financial Management of Property and Construction, 22(1): 92-111.

- https://www.oecd.org/dac/developmentco-operationreport2011.htm - Development Cooperation Report 2011 (OECD), accessed 20th 22. 20 May.

- Palaco, I.; Park, M.J.; Kim, S.K.; Rho, J.J. Public–private partnerships for e-government in developing countries: An early stage assessment framework. Evaluation Program Plan. 2018, 72, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palcic, D. , Reeves, E, and Siemiatycki, M. 2019. "Performance: The Missing 'P' in PPP Research?" Annals of Public & Cooperative Economics, Vol. 90(2): 221-226.

- Osei-Kyei, R.; Chan, A.P.C. Review of studies on the Critical Success Factors for Public–Private Partnership (PPP) projects from 1990 to 2013. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2015, 33, 1335–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybnicek, R. , Plakolm, J. and Baumgartner, L. 2020. "Risks in Public–Private Partnerships: A Systematic Literature Review of Risk Factors, Their Impact and Risk Mitigation Strategies. 1: Public Performance & Management Review, 43(5), 1174. [Google Scholar]

- Sarmento, J. , and Renneboog, L. 2016. "Anatomy of public-private partnerships: Their creation, financing and renegotiations." International Journal of Managing Projects in Business, 9(1): 94-122.

- Tallaki, M. , & Bracci, E. (2021). Risk allocation, transfer and management in public–private partnership and private finance initiatives: a systematic literature review. International Journal of Public Sector Management.

- Siemiatycki, M. Public-Private Partnerships in Canada: Reflections on twenty years of practice. Can. Public Adm. 2015, 58, 343–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silaghi, F.; Sarkar, S. Agency problems in public-private partnerships investment projects. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2020, 290, 1174–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trebilcock, M.; Rosenstock, M. Infrastructure Public–Private Partnerships in the Developing World: Lessons from Recent Experience. J. Dev. Stud. 2015, 51, 335–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urpelainen, J.; Yang, J. Policy Reform and the Problem of Private Investment: Evidence from the Power Sector. J. Policy Anal. Manag. 2016, 36, 38–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchi, V.; Cusumano, N.; Casalini, F. Investigating the performance of PPP in major healthcare infrastructure projects: the role of policy, institutions, and contracts. Oxf. Rev. Econ. Policy 2022, 38, 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, Y.; Xiong, W.; Song, J. The moderating role of governance environment on the relationship between risk allocation and private investment in PPP markets: Evidence from developing countries. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2019, 37, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, Y.; Xiong, W.; Zhu, D. Government Support Programs and Private Investments in PPP Markets. Int. Public Manag. J. 2018, 22, 499–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Xiong, W.; Wu, G.; Zhu, D. Public–private partnership in Public Administration discipline: a literature review. Public Manag. Rev. 2017, 20, 293–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Gao, R.; Hwang, B.-G.; Liu, J. GOVERNMENT SUBSIDIES IN PUBLIC-PRIVATE PARTNERSHIP PROJECTS BASED ON ALTRUISTIC THEORY. Int. J. Strat. Prop. Manag. 2020, 24, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warsen, R.; Nederhand, J.; Klijn, E.H.; Grotenbreg, S.; Koppenjan, J. What makes public-private partnerships work? Survey research into the outcomes and the quality of cooperation in PPPs. Public Manag. Rev. 2018, 20, 1165–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank Institute. 2012. Best Practices in Public-Private Partnerships Financing in Latin America: The role of subsidy mechanisms. Washington, DC. World Bank Institute. 2012. Best Practices in Public-Private Partnerships Financing in Latin America: The role of subsidy mechanisms. Washington, DC.

- World Bank. 2019. Public-Private Partnership (PPP) Practice Operational Note: Viability Gap Financing Mechanisms for PPPs. Washington, DC. World Bank. 2019. Public-Private Partnership (PPP) Practice Operational Note: Viability Gap Financing Mechanisms for PPPs. Washington, DC.

- World Bank. 2014. Public-Private Partnerships: Reference Guide Version 2.0. Washington, DC. World Bank. 2014. Public-Private Partnerships: Reference Guide Version 2.0. Washington, DC.

- Ye, S. (2009). Patterns of financing PPP projects. In Policy, Management and Finance of Public-Private partnerships eds. Akintola Akintoye and Matthias Beck, pp 181 – 196. Blackwell Publishing, 2009, UK.

- Zhang, Y.-C.; Luo, W.-Z.; Shan, M.; Pan, D.-W.; Mu, W.-J. Systematic analysis of PPP research in construction journals: from 2009 to 2019. Eng. Constr. Arch. Manag. 2020, 27, 3309–3339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).