Submitted:

08 April 2024

Posted:

09 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

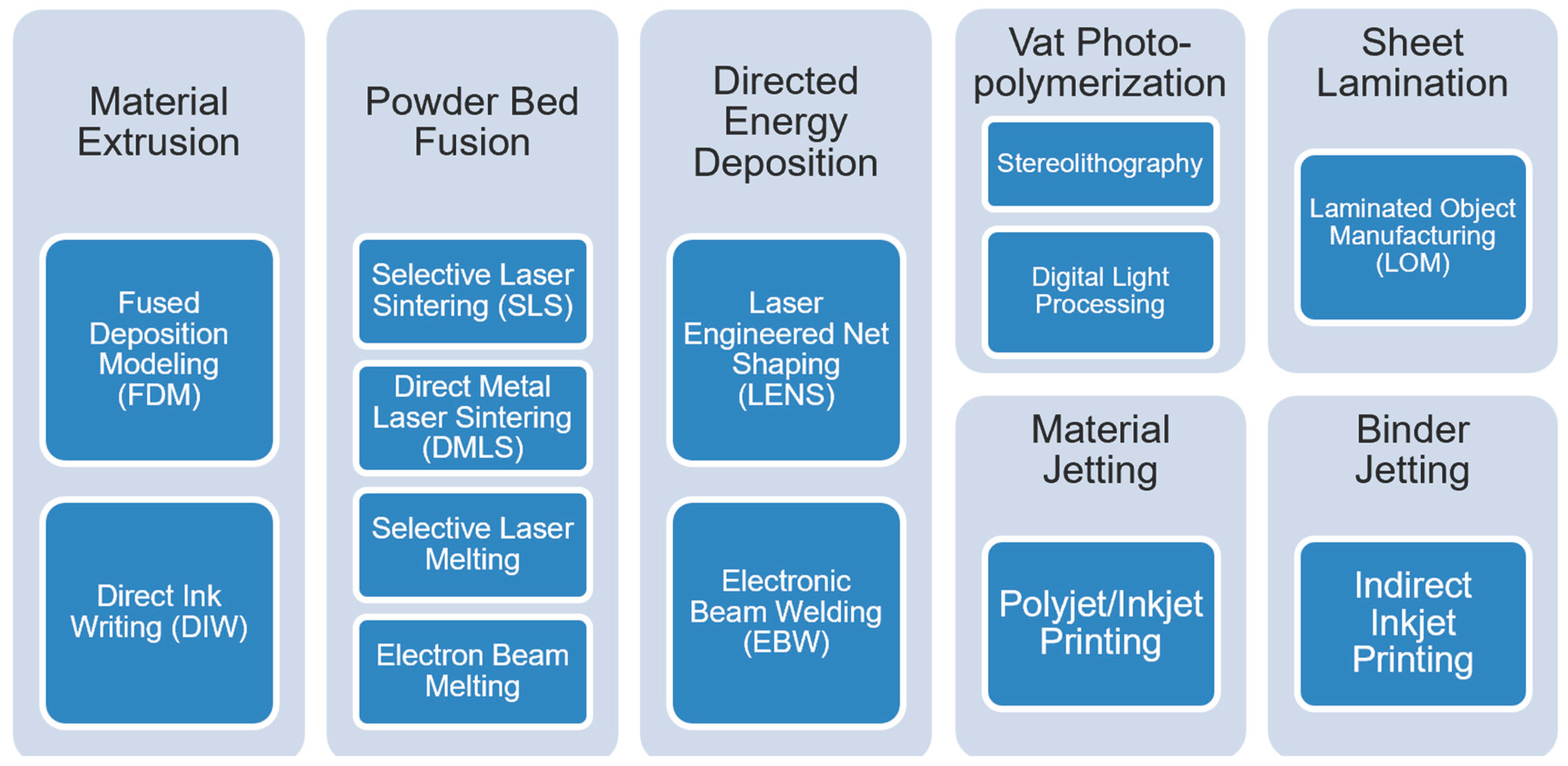

1. Introduction

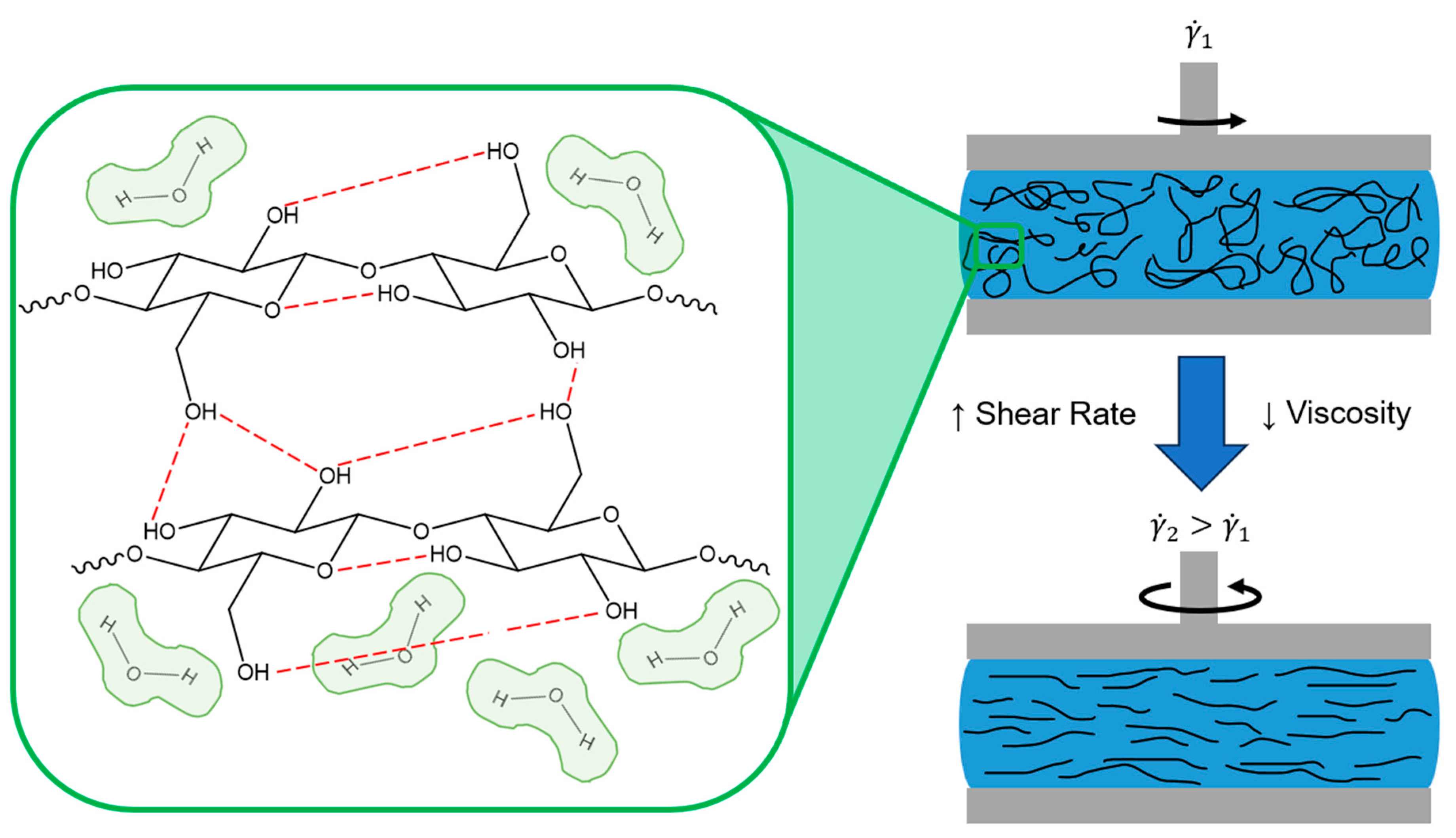

2. 3D Printing with Cellulose

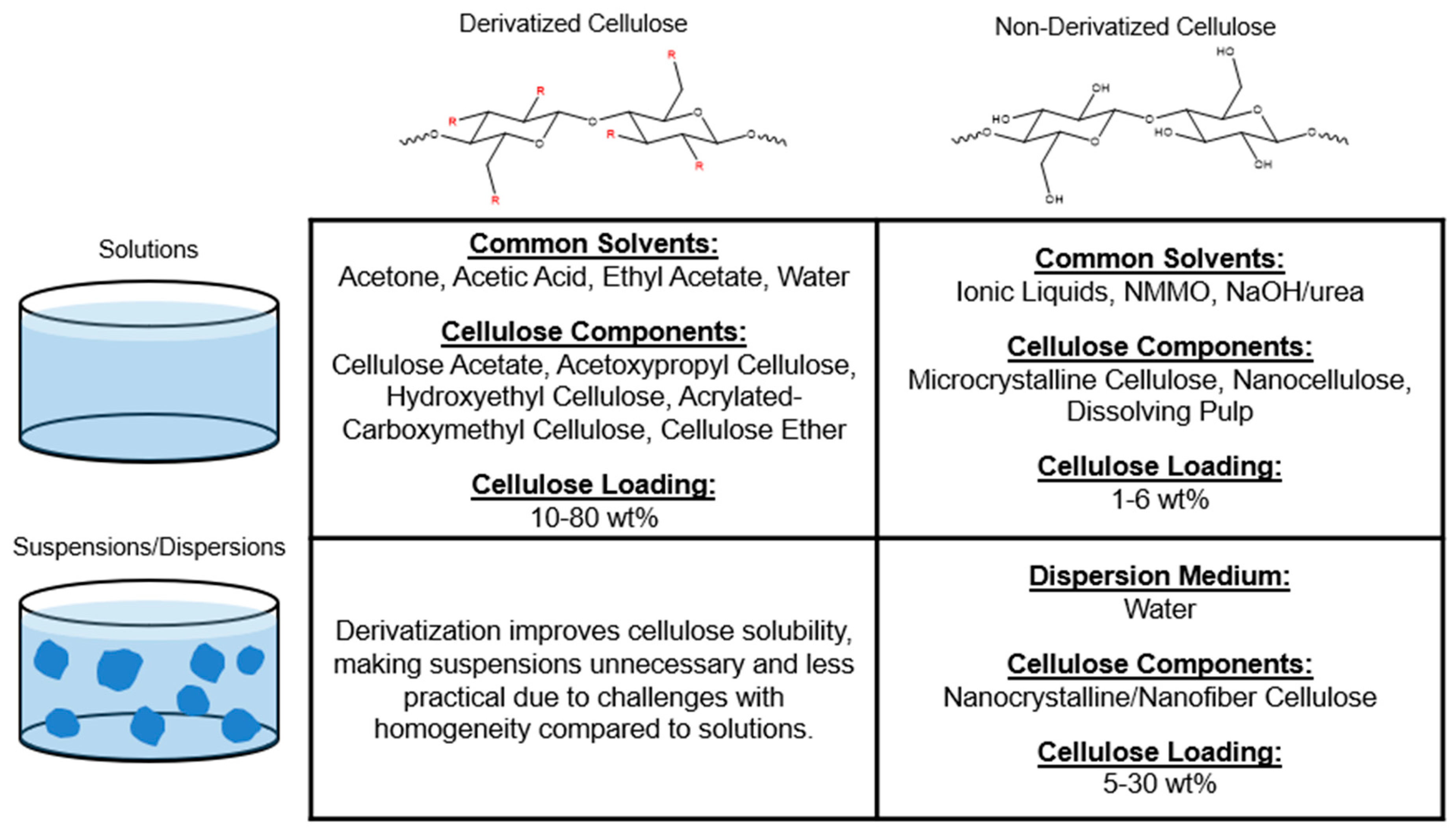

2.1. Cellulosic Materials for 3D Printing

2.1.1. Derivatized Cellulose

2.1.2. Non-Derivatized Cellulose

2.1.3. Cellulose Sources

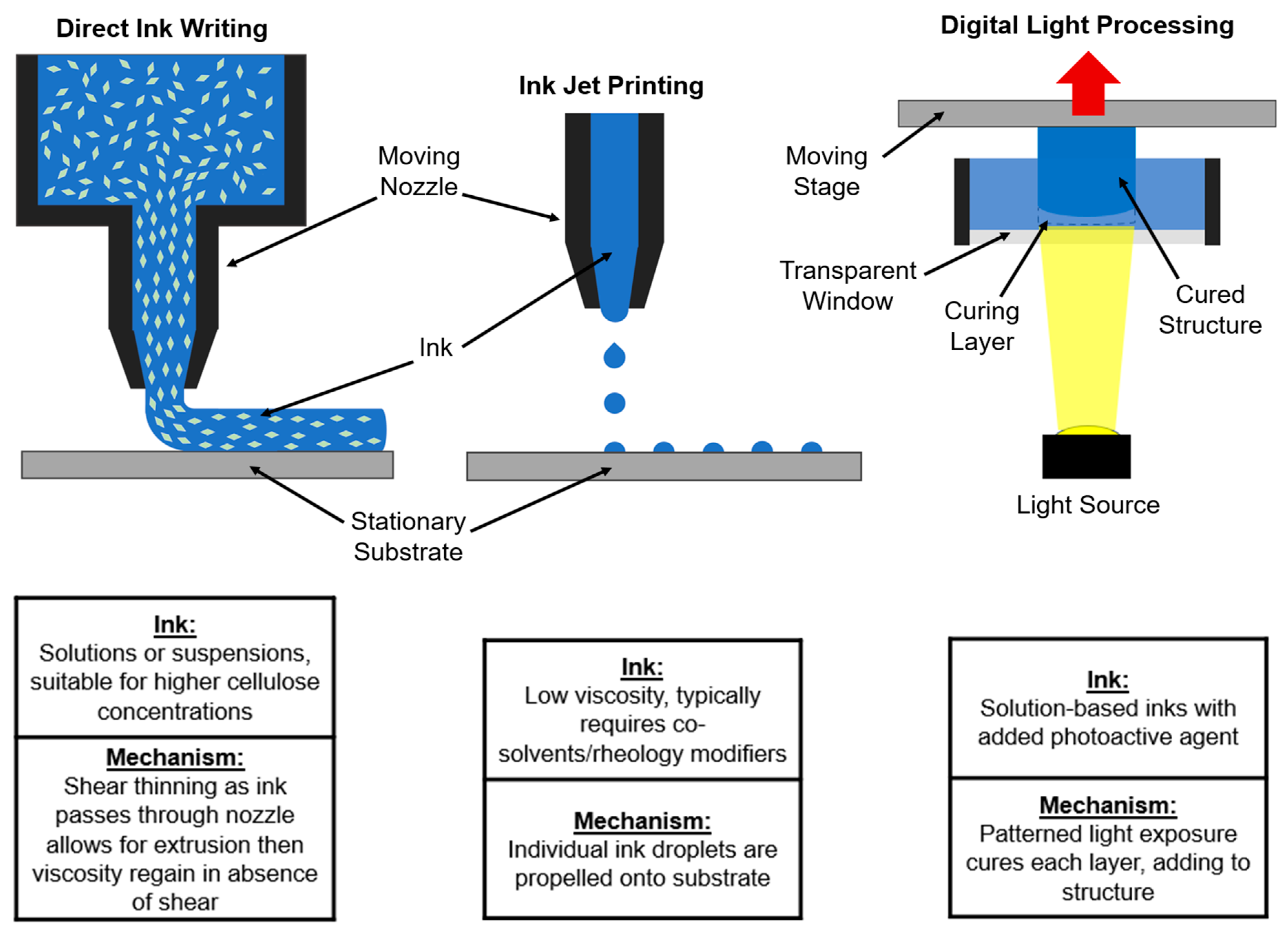

2.2. Printing Methods

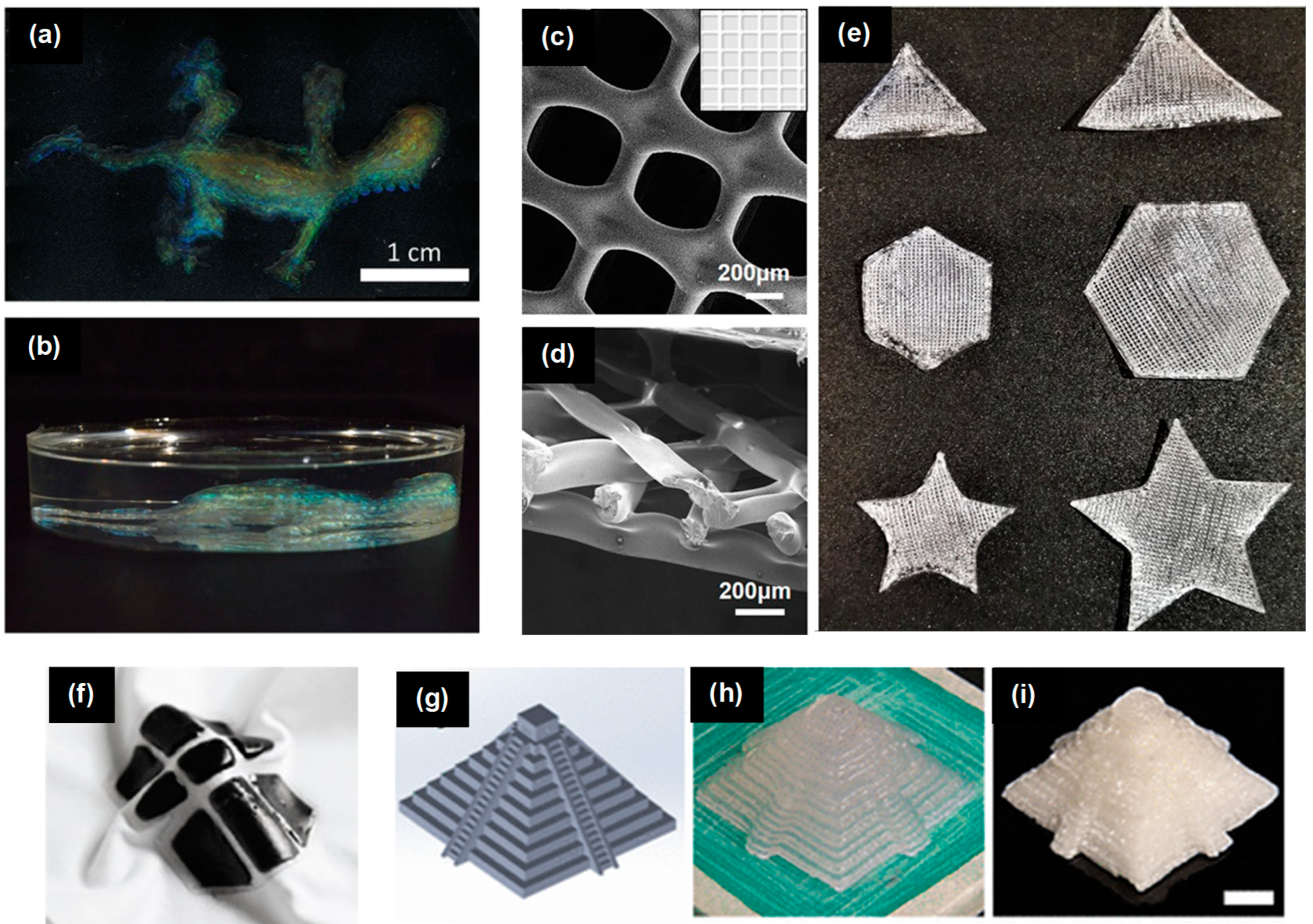

2.2.1. Direct Ink Writing

2.2.2. Other Printing Techniques: Ink-Jet and Digital Light Processing

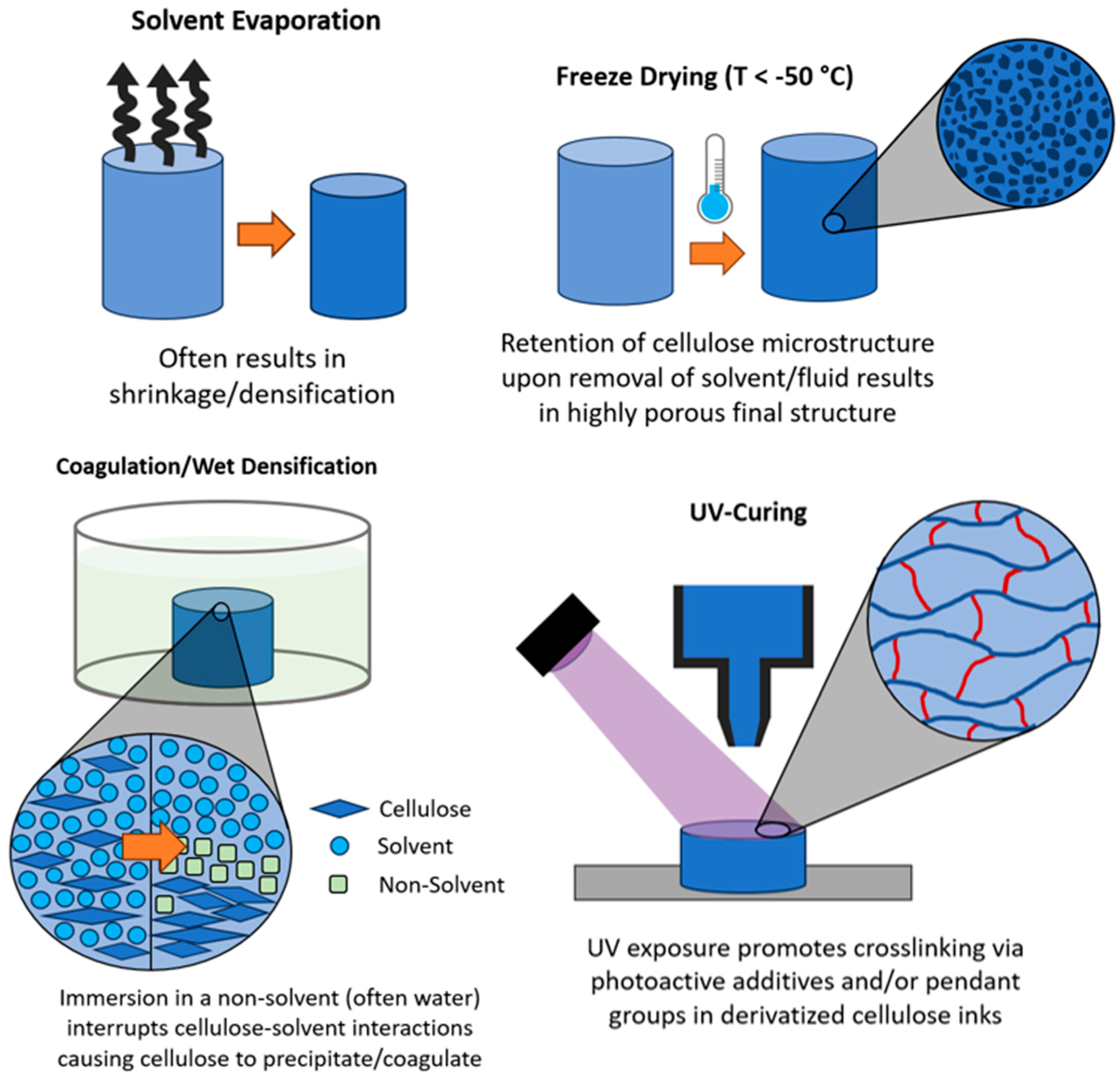

2.3. Post-Processing

2.3.1. Solvent Evaporation

2.3.2. Freeze Drying

2.3.3. Coagulation/Wet Densification

2.3.4. UV-Curing

2.4. Print Properties and Applications

2.4.1. Robust and Tunable Mechanical Properties

2.4.2. Objects with Tailored Functionality

3. Conclusions and Future Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jakus, A.E. An Introduction to 3D Printing – Past, Present, and Future Promise. In 3D Printing in Orthopaedic Surgery; Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2018; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, W.; Zhang, Y.; Ramanujan, D.; Ramani, K.; Chen, Y.; Williams, C.B.; Wang, C.C.L.; Shin, Y.C.; Zhang, S.; Zavattieri, P.D. The status, challenges, and future of additive manufacturing in engineering. Computer-Aided Design 2015, 69, 65–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, I.; Gurley, M. 3D Printing Trend Report 2022: Market changes and technological shifts in the 3D printing market. Available online: https://4075618.fs1.hubspotusercontent-na1.net/hubfs/4075618/020%203DP%20Trend%20report%202022_DEF(April%202022).pdf (accessed on 21 November 2023).

- Wang, Q.; Sun, J.; Yao, Q.; Ji, C.; Liu, J.; Zhu, Q. 3D printing with cellulose materials. Cellulose (London) 2018, 25, 4275–4301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iftekar, S.F.; Aabid, A.; Amir, A.; Baig, M. Advancements and Limitations in 3D Printing Materials and Technologies: A Critical Review. Polymers 2023, 15, 2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Firmanda, A.; Syamsu, K.; Sari, Y.W; Cabral, J.; Pletzer, D.; Mahadik, B.; Fisher, J.; Fahma, F. 3D printed cellulose based product applications. Mater. Chem. Front. 2022, 6, 254–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 3D printing with PLA, vs. ABS: What's the difference? Available online:. Available online: https://www.hubs.com/knowledge-base/pla-vs-abs-whats-difference/ (accessed on 21 November 2023).

- Mohan, D.; Teong, Z.K.; Bakir, A.N.; Sajab, M.S.; Kaco, H. Extending cellulose-based polymers application in additive manufacturing technology: A review of recent approaches. Polymers 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egan, J.; Salmon, S. Strategies and progress in synthetic textile fiber biodegradability. SN Appl. Sci. 2022, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauss, C.; Pickering, K.L.; Muthe, L.P. The use of cellulose in bio-derived formulations for 3D/4D printing: A review. Compos. C: Open Access 2021, 4, 100113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utz, J.U.; Zubizarreta, J.; Geis, N.; Immonen, K.; Kangas, H.; Ruckdäschel, H. 3D Printed Cellulose-Based Filaments—Processing and Mechanical Properties. Materials 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchesne, L.C.; Larson, D.W. Cellulose and the evolution of plant life. BioScience 1989, 39, 238–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieyra, H.; Molina-Romero, J.M.; Calderon-Najera, J.D.; Santana-Diaz, A. Engineering, Recyclable, and Biodegradable Plastics in the Automotive Industry: A Review. Polymers 2022, 14, 3412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackburn, R. Sustainable Textiles: Life Cycle and Environmental Impact; Woodhead Publishing Ltd.: Oxford, United Kingdom, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ergun, R.; Guo, J.; Huebner-Keese, B. Cellulose. Encyclopedia of Food and Health 2015, 694–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewin, M. Handbook of Fiber Chemistry, 3rd ed.; CRC Press, Boca Raton, United States of America, 2007; Volume 16.

- Nishiyama, Y.; Johnson, G.P.; French, A.D.; Forsyth, V.T.; Langan, P. Neutron Crystallography, Molecular Dynamic, and Quantum Mechanics Studies of the Nature of Hydrogen Bonding in Cellulose Iβ. Biomacromolecules 2008, 9, 3133–3140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, L.; Cheng, T.; Duan, C.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, W.; Zou, X.; Aspler, J.; Ni, Y. 3D printing using plant-derived cellulose and its derivatives: A review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 203, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, A.; Zhang, S.; Bhagia, S.; Yoo, C.G.; Ragauskas, A.J. 3D printing of biomass-derived composites: Application and characterization approaches. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 21698–21723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arfin, T. Cellulose and hydrogel matrices for environmental applications. In Sustainable Nanocellulose and Nanohydrogels from Natural Sources; Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2020; pp. 255–274. [Google Scholar]

- Ioelovich, M.; Tercjak, A. (Eds.) Adjustment of Hydrophobic Properties of Cellulose Materials. Polymers (Basel) 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Xu, J.; Wang, K.; Cao, X.; Sun, R. Cellulose acetate fibers prepared from different raw materials with rapid synthesis method. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 137, 685–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erdal, N.; Hakkarainen, M. Degradation of Cellulose Derivatives in Laboratory, Man-Made, and Natural Environments. Biomacromolecules 2022, 23, 2713–2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bifari, E.N.; Khan, S.B.; Alamry, K.A.; Asiri, A.M.; Akhtar, K. Cellulose Acetate Based Nanocomposites for Biomedical Applications: A Review. Current Pharm. Design 2016, 22, 3007–3019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erdmann, R.; Kabasci, S.; Heim, H. Thermal Properties of Plasticized Cellulose Acetate and Its β-Relaxation Phenomenon. Polymers (Basel) 2021, 13, 1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Bhat, M.H.; Kim, C.; Kim, J.; Lee, K. Improved 3D-Printability of Cellulose Acetate to Mimic Water Absorption in Plant Roots through Nanoporous Networks. Macromolecules 2022, 55, 1855–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattinson, S.W.; Hart, A.J. Additive Manufacturing of Cellulosic Materials with Robust Mechanics and Antimicrobial Functionality. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2017, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenhunen, T.M.; Moslemian, O.; Kammiovirta, K.; Harlin, A.; Kääriäinen, P.; Österberg, M.; Tammelin, T.; Orelma, H. Surface tailoring and design-driven prototyping of fabrics with 3D-printing: An all-cellulose approach. Materials and Design 2018, 140, 409–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, J.J.; Lim, G.J.H.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, X.; Ding, J.; He, C. 3D-Printed Anti-Fouling Cellulose Mesh for Highly Efficient Oil/Water Separation Applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 13787–13795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giachini, P.A.G.S.; Gupta, S.S.; Wang, W.; Wood, D.; Yunusa, M.; Baharlou, E.; Sitti, M.; Menges, A. Additive manufacturing of cellulose-based materials with continuous, multidirectional stiffness gradients. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cafiso, D.; Septevani, A.A.; Noè, C.; Schiller, T.; Pirri, C.F.; Roppolo, I.; Chiappone, A. 3D printing of fully cellulose-based hydrogels by digital light processing. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2022, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.L.C.; Lei, I.M.; van de Kerkhof, G.T.; Parker, R.M.; Richards, K.D.; Evans, R.C.; Huang, Y.Y.S.; Vignolini, S. 3D Printing of Liquid Crystalline Hydroxypropyl Cellulose—toward Tunable and Sustainable Volumetric Photonic Structures. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindman, B.; Karlstrom, G.; Stigsson, L. On the mechanism of dissolution of cellulose. J. Mol. Liq. 2010, 156, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markstedt, K.; Sundberg, J.; Gatenholm, P. 3D bioprinting of cellulose structures from an ionic liquid. 3D Print. Addit. Manuf. 2014, 1, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunasekera, D.H.A.T.; Kuek, S.; Hasanaj, D.; He, Y.; Tuck, C.; Croft, A.K.; Wildman, R.D. Three dimensional ink-jet printing of biomaterials using ionic liquids and co-solvents. Faraday Discuss. 2016, 190, 509–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Wu, J.; Zhang, J.; Li, H.; Zhang, Y.; He, J. Room temperature ionic liquids (RTILs): A new and versatile platform for cellulose processing and derivatization. Chem. Eng. J. 2009, 147, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehrhofer, A.F.; Goto, T.; Kawaka, T.; Rosenau, T.; Hettegger, H. The in vitro synthesis of cellulose – A mini-review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chopra, L; Manikanika. Extraction of cellulosic fibers from the natural resources: A short review. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 48, 1265–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahiri, D.; Nag, M.; Dutta, B.; Dey, A.; Sarkar, T.; Pati, S.; Edinur, H.A.; Kari, Z.A.; Noor, N.H.M.; Ray, R.R.; Lee, J. (Eds.) Bacterial Cellulose: Production, Characterization, and Application as Antimicrobial Agent. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, M.M.; Wang, H.; Lau, K.T.; Cardona, F. Chemical treatments on plant-based natural fibre reinforced polymer composites: An overview. Compos. B Eng. 2012, 43, 2883–2892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dittenber, D.B.; Gangarao, H.V. Critical review of recent publications on use of natural composites in infrastructure. Compos. A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2012, 43, 1419–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. Chemical Composition and Characterization of Cotton Fibers. In Cotton Fiber: Physics, Chemistry and Biology; Fang, D., Ed.; Springer, Cham: New York, United States of America, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C. Natural Textile Fibres. In Textiles and Fashion: Materials, Design and Technology; Sinclair, R., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, United Kingdom, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotton Morphology and Chemistry. Available online: https://www.cottoninc.com/quality-products/nonwovens/cotton-fiber-tech-guide/cotton-morphology-and-chemistry/ (accessed on 10 March 2024).

- Sanjay, M. R.; Siengchin, S.; Parameswaranpillai, J.; Jawaid, M.; Pruncu, C.I.; Khan, A. (2019). A comprehensive review of techniques for natural fibers as reinforcement in composites: Preparation, processing and characterization. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 207, 108–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, C.C.S.; Michelin, M.; Cerqueira, M.A.; Goncalves, C.; Tonon, R.V.; Pastrana, L.M.; Freitas-Silva, O.; Vicente, A.A.; Cabral, L.M.C.; Teixeira, J.A. Cellulose nanocrystals from grape pomace: Production, properties, and cytotoxicity assessment. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 192, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romruen, O.; Karbowiak, T.; Tongdeesoontorn, W.; Shiekh, K.A.; Rawdkuen, S. Extraction and Characterization of Cellulose from Agricultural By-Products of Chiang Rai Province, Thailand. Polymers (Basel) 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; Qin, Z.; Chen, Y.; Hy, S.; Ren, Z.; Zhu, M. Efficient Extraction of Cellulose Nanocrystals through Hydrochloric Acid Hydrolysis Catalyzed by Inorganic Chlorides under Hydrothermal Conditions. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 4656–4664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schieppati, D.; Patience, N.A.; Galli, F.; Dal, P.; Seck, I.; Patience, G.S.; Fuoco, D.; Banquy, X.; Boffito, D.C. Chemical and Biological Delignification of Biomass: A Review. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2023, 62, 12757–12794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriksson, M.; Henriksson, G.; Berglund, L.A.; Lindstrom, T. An environmentally friendly method for enzyme-assisted preparation of microfibrillated cellulose (MFC) nanofibers. Eur. Polym. J. 2007, 43, 3434–3441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egan, J.; Wang, S.; Shen, J.; Baars, O.; Moxley, G.; Salmon, S. Enzymatic textile fiber separation for sustainable waste processing. Resour. Environ. Sustain. 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Egan, J.; Salmon, S. Preparation and characterization of cotton fiber fragments from model textile waste via mechanical milling and enzyme degradation. Cellulose 2023, 30, 10879–10904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- What is FDM (fused deposition modeling) 3D printing? Available online:. Available online: https://www.hubs.com/knowledge-base/what-is-fdm-3d-printing/ (accessed on 21 November 2023).

- Barud, H.S.; de Araujo Junior, A.M.; Santos, D.B.; de Assuncao, R.M.N.; Meireles, C.S.; Cerqueira, D.A.; Filho, G.R.; Ribeiro, C.A.; Messaddeq, Y.; Ribeiro, S.J.L. Thermal behavior of cellulose acetate produced from homogeneous acetylation of bacterial cellulose. Thermochim. Acta 2008, 471, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Lee, J.; Jeon, H.; Park, H.; Oh, S.; Chung, I. (2020). Studies on the melt viscosity and physico-chemical properties of cellulose acetate propionate composites with lactic acid blends. Mol. Cryst. Liq. Cryst. 2020, 707, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuladhar, S.; Clark, S.; Habib, A.; Paz, R. (Eds.) Tuning Shear Thinning Factors of 3D Bio-Printable Hydrogels Using Short Fiber. Materials (Basel) 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrada-Manchon, H.; Rodriguez-Gonzalez, D.; Fernandez, M.A.; Kucko, N.W.; Barrere-de Groot, F.; Aguilar, E. Effect on Rheological Properties and 3D Printability of Biphasic Calcium Phosphate Microporous Particles in Hydrocolloidal-Based Hydrogels. Gels 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Xiong, X.; Liu, X.; Cui, R.; Wang, C.; Zhao, G.; Zhi, W.; Lu, M.; Duan, K.; Weng, J.; Qu, S.; Ge, J. 3D Bioprinting of shear-thinning hybrid bioinks with excellent bioactivity derived from gellan/alginate and thixotropic magnesium phosphate-based gels. J. Mater. Chem. B 2020, 8, 5500–5515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Therriault, D.; White, S.R.; Lewis, J.A. Rheological Behavior of Fugitive Organic Inks for Direct-Write Assembly. Appl. Rheol. 2007, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolek-Tryznowska, Z. Rheology of Printing Inks. In: Printing on Polymers: Fundamentals and Applications. William Andrew: Norwich, United States of America, 2016.

- Saadi, M.A.S.R.; Maguire, A.; Pottackal, N.T.; Thakur, M.S.H.; Ikram, M.M.; Hart, A.J.; Ajayan, P.M.; Rahman, M.M. Direct Ink Writing: A 3D Printing Technology for Diverse Materials. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrulas, R.V.; Corvo, M.C. Rheology in Product Development: An Insight into 3D Printing of Hydrogels and Aerogels. Gels 2023, 9, 986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bercea, M.; Garcia-Gonzalez, C.A. (Eds.) Rheology as a Tool for Fine-Tuning the Properties of Printable Bioinspired Gels. Molecules 2023, 28, 2766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gericke, M.; Schlufter, K.; Liever, T.; Heinze, T.; Budtova, T. Rheological Properties of Cellulose/Ionic Liquid Solutions: From Dilute to Concentrated States. Biomacromolecules 2009, 10, 1188–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sescousse, R.; Le, K.A.; Ries, M.E.; Budtova, T. Viscosity of Cellulose−Imidazolium-Based Ionic Liquid Solutions. J. Phys. Chem. B 2010, 114, 7222–7228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuang, Q.L.; Zhao, J.; Niu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Z. Celluloses in an ionic liquid: the rheological properties of the solutions spanning the dilute and semidilute regimes. J. Phys. Chem. B 2008, 112, 10234–10240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Zhu, Y.; Yang, J. 3D bioprinting of cellulose with controlled porous structures from NMMO. Mater. Lett. 2018, 210, 136–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Oguzlu, H.; Jiang, F. 3D printing of lightweight, super-strong yet flexible all-cellulose structure. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 405, 126668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, C.; Bian, H.; Gao, T.; Jiang, F.; Kierzewski, I.M.; Wang, Y.; Yao, Y.; Chen, L.; Shao, Z.; Zhu, J.Y.; Hu, L. Thermally Stable Cellulose Nanocrystals toward High-Performance 2D and 3D Nanostructures. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 28922–28929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siqueira, G.; Kokkinis, D.; Libanori, R.; Hausmann, M.K.; Gladman, A.S.; Neels, A.; Tingaut, P.; Zimmermann, T.; Lewis, J.A.; Studart, A.R. Cellulose Nanocrystal Inks for 3D Printing of Textured Cellular Architectures. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2017, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, V.C.F.; Dunn, C.K.; Zhang, Z.; Deng, Y.; Qi, H.J. Direct Ink Write (DIW) 3D Printed Cellulose Nanocrystal Aerogel Structures. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, V.C.F.; Mulyadi, A.; Dunn, C.K.; Deng, Y.; Qi, H.J. Direct Ink Write 3D Printed Cellulose Nanofiber Aerogel Structures with Highly Deformable, Shape Recoverable, and Functionalizable Properties. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 2011–2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Huang, X.; Huang, Y.; Yuan, J.; Huang, D.; Cheng, G.J.; Zhang, L.; Chang, C. Additive Printed All-Cellulose Membranes with Hierarchical Structure for Highly Efficient Separation of Oil/Water Nanoemulsions. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 44375–44382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klar, V.; Pere, J.; Turpeinen, T.; Kärki, P.; Orelma, H.; Kuosmanen, P. Shape fidelity and structure of 3D printed high consistency nanocellulose. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausmann, M.K.; Siqueira, G.; Libanori, R.; Kokkinis, D.; Neels, A.; Zimmermann, T.; Studart, A.R. Complex-Shaped Cellulose Composites Made by Wet Densification of 3D Printed Scaffolds. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, T.; Nishiyama, Y.; Putaux, J.; Vignon, M.; Isogai, A. Homogeneous Suspensions of Individualized Microfibrils from TEMPO-Catalyzed Oxidation of Native Cellulose. Biomacromolecules 2006, 7, 1687–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uddin, M.J.; Hassan, J.; Douroumis, D. Thermal Inkjet Printing: Prospects and Applications in the Development of Medicine. Technologies 2022, 10, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Ali, S.; Bermak, A. Smart Manufacturing Technologies for Printed Electronics. In Hybrid Nanomaterials: Flexible Electronics Materials; IntechOpen: London, United Kingdom, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Duenas, L.; Gomez, E.; Larranaga, M.; Blanco, M.; Goitandia, A.M.; Aranzabe, E.; Vilas-Vilela, J.L.; Sahatiya, P. (Eds.) Review on Sustainable Inks for Printed Electronics: Materials for Conductive, Dielectric and Piezoelectric Sustainable Inks. Materials (Basel) 2023, 16, 3940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davoudinejad, A. Vat photopolymerization methods in additive manufacturing. In Additive Manufacturing; Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Amini, A.; Guijt, R.M.; Themelis, T.; De Vos, J.; Eeltink, S. Recent developments in digital light processing 3D-printing techniques for microfluidic analytical devices. J. Chromatogr. A 2023, 1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhary, R.; Fabbri, P.; Leoni, E.; Mazzanti, F.; Akbari, R.; Antonini, C. Additive manufacturing by digital light processing: a review. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 8, 331–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luongo, A.; Falster, V.; Doest, M.B.; Ribo, M.M.; Eiriksson, E.R.; Pedersen, D.B.; Frisvad, J.R. Microstructure Control in 3D Printing with Digital Light Processing. Computer Graphics Forum 2019, 39, 347–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprioli, M.; Roppolo, I.; Chiappone, A.; Larush, L.; Pirri, C.F.; & Magdassi, S.; & Magdassi, S. 3D-printed self-healing hydrogels via Digital Light Processing. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 2462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowak, D.; Jakubczyk, E. The Freeze-Drying of Foods – The Characteristic of the Process Course and the Effect of Its Parameters on the Physical Properties of Food Materials. Foods 2020, 9, 1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hakansson, K.M.O.; Henriksson, I.C.; de la Pena Vazquez, C.; Kuzmenko, V.; Markstedt, K.; Enoksson, P.; Gatenholm, P. Solidification of 3D Printed Nanofibril Hydrogels into Functional 3D Cellulose Structures. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2016, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavrel, M.; Bross, D.; Funke, M.; Buchs, J.; Spiess, A.C. High-throughput screening for ionic liquids dissolving (ligno-)cellulose. Bioresour. Technol. 2009, 100, 2580–2587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voet, V.S.D.; Guit, J.; Loos, K. Sustainable Photopolymers in 3D Printing: A Review on Biobased, Biodegradable, and Recyclable Alternatives. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2020, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Print Speed | Solidification Time | Print Feature Resolution |

|---|---|---|

| 20 mm/s (DIW) [70] 12-15 s/layer (DLP) [31] |

60 s (Solvent Evaporation) [27,28] 12 hrs (Freeze Drying) [67] 30 min – 2 hrs (Wet Densification) [35] 3 min (UV-Curing) [31] |

~200 µm (DIW) [70,71] 21 µm (Ink-Jet) [35] 27 µm DLP [31] |

| Cellulose Content |

Printing Method |

Solidification Mechanism |

Product/ Proposed Use |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNC (15 wt%) |

DIW | Freeze Drying | Biocompatible porous structures | Jia, et al. [69] |

| CNC (0.5 - 40 wt%) |

DIW | Evaporation | Solid structures | Siqueira, et al. [70] |

| CNC (11.8 – 30 wt%) |

DIW | Freeze Drying | Complex porous structures |

Li, et al. [71] |

| CNF (2.8 wt%) |

DIW | Freeze Drying/Oven | Highly deformable, shape recoverable, and functionalized solid objects | Li, et al. [72] |

| CNC (1 − 5 wt%) |

Ink-Jet | Evaporation | Oil/water separating membrane | Li, et al. [73] |

| Enzymatically fibrillated CNC (15.5 - 25 wt%) |

DIW | Evaporation | Objects with high mechanical properties | Klar, et al. [74] |

| CNC/ CNF (20 wt% / 1 wt%) |

DIW | Wet Densification | Objects with high mechanical properties | Hausmann, et al. [75] |

| Cellulose Content |

Solvent1 | Printing Method |

Solidification Mechanism |

Product/ Proposed Use |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BC, Avicel, and Dissolving pulp (each 1 - 4 wt%) |

EmimAc (≥ 90%) |

DIW | Coagulation | Porous gel structures | Markstedt, et al. [34] |

| MCC (1 - 4.8 wt%) |

EmimAc (> 95%), BmimAc (> 95%); rheology modifiers: 1-butanol, DMSO |

Ink-Jet | Coagulation | Droplets | Gunasekera, et al. [35] |

| CA (30 wt%) |

Acetic Acid | DIW | Evaporation | Rigid structures, refractive printing material (reflective beads) | Tenhunen, et al. [28] |

| APC (80 wt%) |

Acetone | DIW | Evaporation | Flexible structures, thermo-responsive designs | Tenhunen, et al. [28] |

| Dissolving Pulp (5 wt%) |

NMMO (50 wt%) |

DIW | Freeze Drying | Objects with high mechanical properties | Li, et al. [67] |

| CA (25 - 35 wt%) |

Acetone | DIW | Evaporation | Objects with high mechanical properties | Pattinson and Hart [27] |

| CA (22 wt%) |

Ethyl Acetate | DIW | Evaporation | Anti-fouling cellulose mesh for oil/ water separation | Koh, et al. [29] |

| HEC (10 wt%) |

Water | Adapted DIW | Evaporation | Materials with stiffness gradients | Giachini, et al. [30] |

| Whatman TM #1 filter paper (1 - 6 wt%) |

NaOH / Urea (7.0 wt% / 12.0 wt%) |

DIW | Coagulation/Freeze Drying | Lightweight, strong, flexible honeycomb structure objects | Jiang, et al. [68] |

| Acrylated-CMC (2 wt%) |

Water, BAPO-OH (photoinitiator), Green Dye | DLP | UV-Curing | Hydrogels | Cafiso, et al. [31] |

| Methacrylate- functionalized HPC (64 - 68 wt%) |

Water | DIW | UV-Curing | Objects with structural colors | Chan, et al. [32] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).