1. Introduction

The urban environment is becoming increasingly diverse and complex with the growth of cities. However, the rapid growth in cities is leading to urban segregation, which divides people from different classes, races, religions, and cultures in different areas of cities and significantly affecting social sustainability. In Iran due to the significant increase in the country's population in recent years, residential segregation and social housing policy have become crucial issues and the built environment is not immune to the critical factors that lead to residential segregation in this country. While social, economic, and political factors are known to influence residential segregation in Iran (Massey and Denton, 1988), the correlation between the built environment and sociology has also been identified as a contributing factor (Sharifi and Murayama, 2014). Therefore, understanding the relationship between the built environment and sociology from the architectural insight is essential in addressing the issue of residential segregation and developing effective social housing policies and creating more inclusive and sustainable urban environments as well.

This paper focuses on exploring the correlation between the built environment and sociology concerning residential segregation and social housing policy in Iran. The main objective of this study is to identify design strategies that minimize the risk of social isolation, promote social interaction, and foster a sense of community within affordable housing zone. This research also aims to understand how architects and urban planners can develop socially sustainable design solutions that respond to the diverse needs of different social groups in affordable residential areas. Accordingly, the scope of the investigation involves studying existing literature on urban segregation, as well as the existing factors contributing to social segregation by focusing on the role of architects and urban planners in promoting social sustainability.

Therefore, three main research questions will be answered in this paper on the basis of its objective and scope.

What are the main factors contributing to residential segregation, and how do they impact social isolation?

To what extent do systemic inequalities contribute to patterns of residential segregation and social isolation?

What are the effective strategies for reducing residential segregation and promoting more integrated and connected residential communities, and how can these strategies be implemented at different scales and contexts in the long-term?

Moreover, it is hypothesis that the main factor contributing to residential segregation in Iran is income inequality and the social exclusion as a result of poverty can be mitigated through the implementation of architectural design strategies that promote inclusivity, connectivity and community building. Thus, integrating social sustainability into design process can improve the well-being of marginalized communities, reduce environmental impact and promote social cohesion, leading to more sustainable and equitable urban environments.

2. Material and Methods

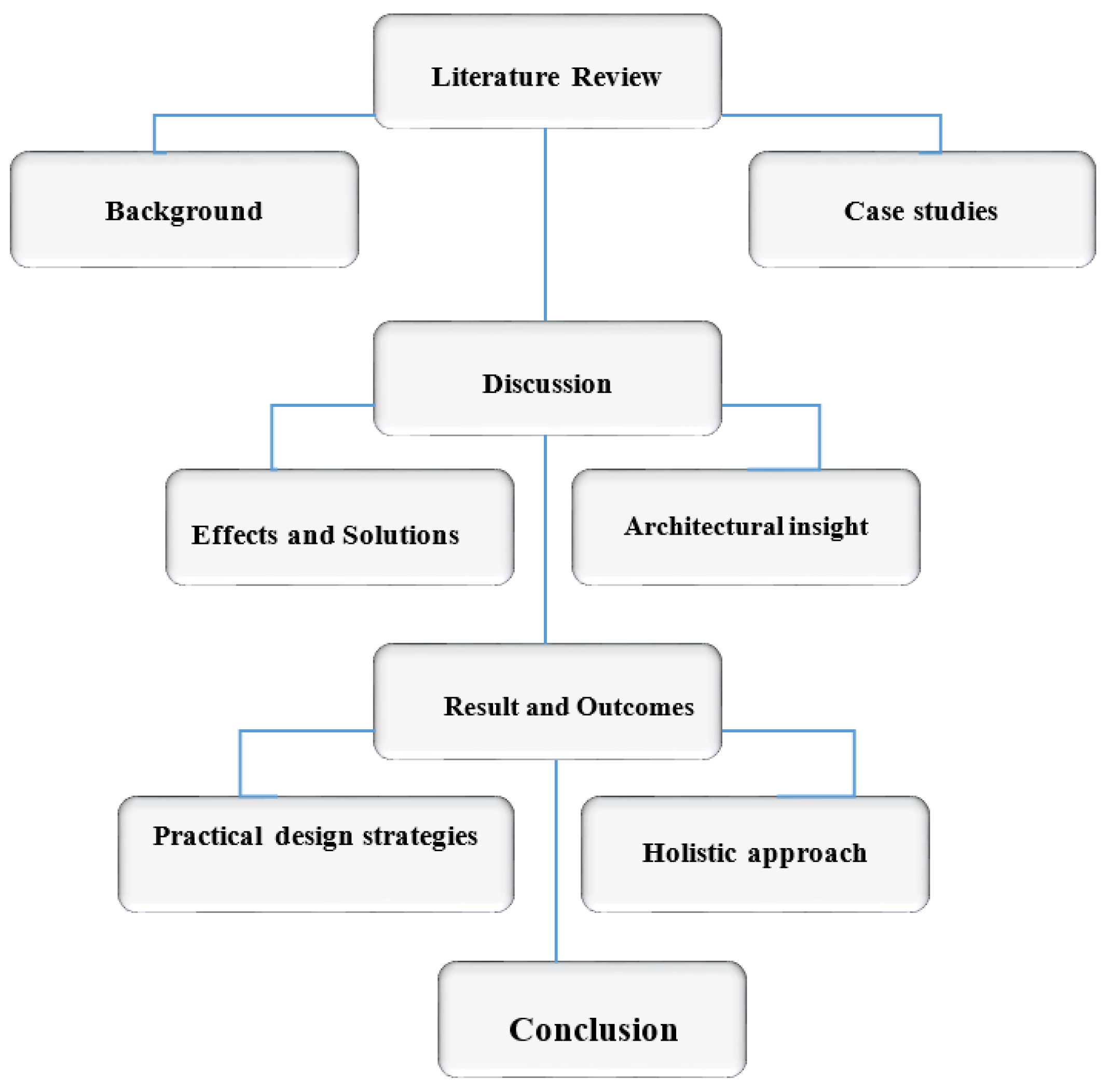

The findings will be synthesized to provide a critical review of the correlation between the built environment and sociology concerning residential segregation and social housing policy in Iran. To provide a comprehensive understanding of the correlation between sociology and built environment literature review was conducted on existing research on urban segregation and social sustainability, focusing specifically on architectural solutions, which will involve reviewing academic articles, reports, and case reviews related to urban segregation, as well as design strategies. Case reviews have exemplified both positive and negative social outcomes related to urban segregation and involved identifying design elements.

The next part of the study is allocated to analyzing the data collected through literature review and case studies and finally, by utilizing the findings from the research to conclude the effectiveness of design strategies some recommendations for policies, regulations, and design guidelines have been made that can be implemented to improve social sustainability in urban areas. Therefore, to test this hypothesis, a mixed-methods approach can be used, combining both quantitative and qualitative research methods.

Firstly, a quantitative analysis of census data can be conducted to identify patterns of residential segregation and social isolation in different regions. This analysis can be supplemented with a review of existing literature on the subject to inform the development of research questions and identify key variables that contribute to residential segregation and social isolation. Then, a comparative case study approach can be used to explore how the intersection of residential segregation with other forms of social exclusion, such as poverty and discrimination, contributes to residential social isolation. A mixed-methods approach can help to triangulate findings and provide a nuanced understanding of how residential segregation affects social isolation and social capital within communities.

Figure 1.

lowchart of the structure of this study.

Figure 1.

lowchart of the structure of this study.

3. Literature Review

3.1. Background

Urban segregation refers to the spatial separation of different social groups within a city based on various factors such as race, ethnicity, income, and social class (Massey & Denton, 1993). Residential segregation, in particular, refers to the grouping of individuals into distinct neighborhoods based on their social characteristics (Perez et al., 2019). As discovered by several studies, urban segregation can have significant implications for social sustainability. One aspect of social sustainability is social capital, which refers to the social networks and relationships that exist within a community. Research has found that the urban form and configuration of neighborhoods can impact social capital (Ghonimi & Awaad, 2018). Social sustainability focuses on social capital, or the relationships and social networks in a community. The layout and design of neighborhoods in urban areas have been found to affect social capital.

Furthermore, urban segregation is considered a key issue in global sustainable community planning and decision-making (Perez et al., 2019). It is associated with social inequality, polarization, and limited opportunities for certain communities (Chen et al., 2022). Additionally, urban sprawl and income segregation are both undesired urban patterns that occur during urban development. Empirical studies have demonstrated the positive correlations between income inequality and segregation. However, the relationship between urban sprawl and income segregation is complex and requires further investigation (Guo et al., 2017). It involves considering the planning and social subsystems of urban renewal and evaluating sustainability. Therefore, Understanding the correlation between urban segregation and social sustainability requires examining the urban form, configuration of neighborhoods, and the social and economic factors that contribute to segregation. Further research is needed to explore this relationship and to develop strategies for achieving sustainable urban renewal in the face of socio-spatial segregation (Zheng et al., 2014).

In Iran, residential segregation has been a significant issue due to various social, economic, and political factors. Nonetheless, the built environment's impact on the separation of communities is also a vital aspect that needs investigation. This literature review focuses on analyzing the correlation between the built environment and sociology concerning residential segregation and social housing policy in Iran. Residential segregation is a deliberate act of segregating individuals based on race, ethnicity, income, and social class, resulting in social isolation, limited access to amenities and essential services, and increased social problems (Massey & Denton, 1993; Krivo & Kaufman, 2004). According to Sharifi and Murayama (2014), the built environment's design, layout, and location can contribute significantly to residential segregation. Poor design, lack of amenities, and inadequate planning can isolate communities and limit access to critical services, exacerbating communities' social and economic divide.

Several studies have investigated the extent of residential segregation in Iran, indicating high levels of segregation in cities, particularly Tehran (Roozbehani & Asgharizadeh, 2014; Erfani & Karami, 2010). Researchers have found that social, economic, and political factors contribute significantly to residential segregation, leading to social inequality and limited opportunities for marginalized communities. However, due to Iran's urban growth and the increasing demand for affordable housing, developing adequate social housing policies has become imperative.

Moreover, studies have evaluated Iran's social housing policy, analyzing the effectiveness of government interventions in mitigating residential segregation (Erfani & Karami, 2010; Hosseini & Siadat, 2011; Gholami et al., 2013). They argued that while social housing has played a critical role in providing affordable housing to low-income households, it has not been effective in addressing residential segregation. They suggest developing integrated housing policies that prioritize mixed-income and diverse communities to reduce social and economic divides that exacerbate residential segregation in Iran.

3.2. Urban Segregation and Social Sustainability

The effects of urban segregation on social sustainability can be categorized into main aspects such as Health and well-being, Environmental sustainability, and also Education and employment opportunities. This shows that the residential segregation will intersect with other forms of social exclusion, such as poverty or discrimination, to exacerbate residential social isolation (Fuller& Vinodrai, 2011). In addition, there are notable adverse consequences associated with residential segregation, including the following:

3.2.1. Limited Opportunities for Social Interaction

Residential segregation can lead to the formation of isolated pockets of communities, which can limit the opportunities for people to interact with those from other backgrounds. This can lead to a lack of diversity in social networks, making it difficult to form connections with others beyond your immediate community (Massey & Denton, 1988).

3.2.2. Reduced Access to Services and Amenities

Segregated neighborhoods may have limited access to essential services such as healthcare, public transportation, and quality education. This can lead to social isolation as residents may be unable to access these services and participate in activities that can foster social connections (Krivo & Kaufman, 2004).

3.2.3. Negative Stereotypes and Perceptions

Segregation can lead to the formation of negative stereotypes and perceptions about different groups of people. This can make it difficult for individuals from segregated communities to form relationships with those from different backgrounds, leading to social isolation (Bobo, 1999).

3.2.4. Greater Vulnerability to Social Problems

Individuals or communities living in segregated areas may face greater vulnerability to social problems such as crime, poverty, and unemployment. These problems can contribute to a lack of social connection and a sense of isolation from the broader community (Katznelson, 2005).

Overall, residential segregation can contribute to social isolation by limiting opportunities for social interaction, reducing access to services and amenities, fostering negative stereotypes and perceptions, and increasing vulnerability to social problems. Therefore, to address the social isolation associated with residential segregation, there is a need for comprehensive policies and initiatives that foster social inclusion and address the underlying causes of segregation (Chetty et al., 2016).

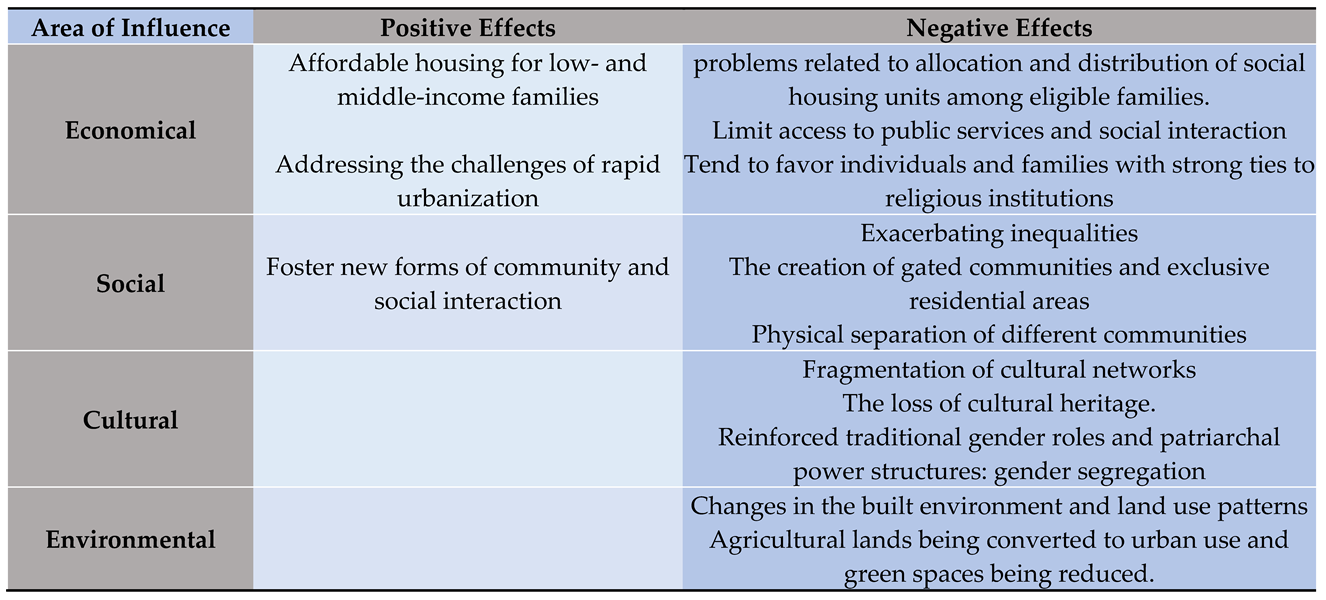

3.3. Case Review of Social Housing Policy in Iran

In order to provide housing for low, mid and high income families, the Iranian government has developed a range of Social Housing Programmes. These programs have had both qualitative and quantitative effects on social sustainability in Iran. A study by Tabibi et al. (2015) found that social housing projects have provided opportunities for low-income families to access better housing and improved living conditions. Rahimi and Kurani (2019) also discovered that, in addition to improving housing affordability by reducing the government's subsidized housing programme for lower income households, it also led to a significant reduction of finance burdens on poor families. However, the social housing program has also faced challenges and criticisms. Another study by Javadinejad and Zeraatpisheh (2017) highlighted issues of quality and maintenance in social housing units, as well as problems related to allocation and distribution of social housing units among eligible families. These issues have affected the long-term sustainability of the social housing program and raised concerns over the equitable distribution of housing resources.

Generally, the social housing program has had both positive and negative effects on social sustainability in Iran. While it has helped to reduce housing costs for low- and middle-income families, there are also challenges to be addressed in order to ensure the long-term sustainability and equitable distribution of housing resources.

Another study looked at the impact of the Iranian government's "New Towns" program, which was designed to alleviate overcrowding in Tehran and other major cities. The author found that while the program did provide more housing options for some residents, it also reinforced existing patterns of segregation and perpetuated inequality (Gharibnavaz and Zebardast, 2017)

The Iranian government's "New Towns" program is a major urban development initiative that aims to address the challenges of rapid urbanization in Tehran and other major cities. This program, which has both qualitative and quantitative impacts on urban development, has been the subject of numerous studies and reports.

Qualitative research suggests that the New Towns program can have significant impacts on social and cultural dynamics within the city. A study by Mansouri and Pojhan (2014) found that the creation of new urban spaces and the relocation of people to these areas can result in social and cultural changes, as well as changes in the built environment. For example, the development of new residential areas can foster new forms of community and social interaction, while also displacing traditional social structures and networks.

On a quantitative level, the New Towns program has been shown to have significant impacts on urban growth and land use patterns. A study by Aminzadeh and Salimi (2017) found that the New Towns program has led to a significant increase in urban land development and population growth in Tehran and other major cities. In particular, the study found that new urban areas created under the program have caused significant land use change, with agricultural lands being converted to urban use and green spaces being reduced.

However, while the New Towns program has the potential to address the challenges of urbanization in Iran, it has also been criticized for exacerbating inequalities and social fragmentation. A study by Ahmadian and Zarei (2019) found that the program has led to the creation of gated communities and exclusive residential areas, which limit access to public services and social interaction. Moreover, the displacement of people from traditional urban areas to the New Towns has resulted in the fragmentation of social and cultural networks, and the loss of cultural heritage.

A third study focused on the city of Mashhad, where the housing market is heavily influenced by religious organizations and institutions. The system of "religious housing" contributed to segregation along socioeconomic and religious lines, and that it also reinforced traditional gender roles and patriarchal power structures (Mojtahedi and Malekian, 2021). The city of Mashhad is known for having a unique housing market influenced by religious organizations and institutions. Studies, have showed that the system contributed to segregation along socioeconomic and religious lines, with certain neighborhoods and areas being associated with different religious groups and income levels. This not only resulted in the physical separation of different communities, but also reinforced traditional gender roles and patriarchal power structures.

Mojtahedi and Malekian (2021) noted that "religious housing" in Mashhad is controlled by religious foundations and institutions, which provide affordable housing to people in need. However, the selection criteria for these housing units tend to favor individuals and families with strong ties to religious institutions, resulting in a system that reinforces religious and socioeconomic segregation within the city. Additionally, gender segregation is common in "religious housing" in Mashhad, with women and men being assigned separate living areas within the same building or neighborhood.

On a quantitative level, the system of "religious housing" has been shown to contribute to housing segregation by income level. According to a study by Davoodi and Jahanshahi (2016), low-income residents in Mashhad are more likely to live in neighborhoods with other low-income residents, resulting in a concentration of poverty within certain parts of the city. Furthermore, the study found that neighborhoods with higher levels of poverty and unemployment tend to have poorer access to public services such as education and healthcare, further exacerbating inequalities within the city.

4. Discussion

4.1. Key Findings

The analysis of the selected literature indicates that the social housing policies implemented in Iran have not been effective in addressing residential segregation, leading to the creation of segregated communities. The construction of social housing units in peripheral areas, lack of amenities, and inadequate planning exacerbate the problem of segregation in these communities. The built environment plays a significant role in residential segregation in Iran. The design, layout, and location of buildings affect social interactions and contribute to the creation of isolated communities.

Moreover, problems related to allocation and distribution and the inadequate provision of social housing has led to the growth of informal settlements, which lack basic amenities and services. This has a negative impact on the health and well-being of people living in these areas. The poor quality of social housing units in Iran also affects the environment, leading to land degradation and pollution. The correlation between the built environment and sociology can improve the quality of social housing and the living standards of people in Iran.

The qualitative research methods conducted with residents living in areas of high residential segregation revealed that the impacts of residential social isolation go beyond physical isolation, with residents experiencing limited social interactions, higher rates of stress and mental health issues, and feelings of marginalization and disempowerment (Massey & Denton, 1993). Moreover, social capital within these communities is often weak, which further exacerbates existing social inequality and makes it difficult for residents to access resources and services that could improve their well-being.

Lastly, through the comparative case study approach, we found that residential segregation intersects with other social exclusion factors, such as poverty and discrimination, to create a cycle of disadvantage, where individuals living in areas of segregation face multiple forms of disadvantage (McKee & Rizzuto, 2002). This cycle of disadvantage leads to a lack of investment in these communities, hindering their social and economic mobility.

Table 1.

Key findinfs of social housing policy in Iran. Source: Author.

Table 1.

Key findinfs of social housing policy in Iran. Source: Author.

4.2. Social Capital Effects Based on Observations

Following thorough analysis and empirical investigation, four distinct classifications of environmental dysfunctions have been discerned as a consequence of design dynamics within social housing case studies conducted in Iran:

Monotony and Repetitiveness

Remoteness and inappropriate location

Dense construction and excessive accumulation of buildings

Construction platform without any natural elements

4.2.1. Monotony and Repetitiveness

According to multiple sources (Gifford, 2014; Ulrich et al., 2008), the social and psychological repercussions of monotonous and repetitive environments can be detrimental to individuals who are regularly exposed to them. These consequences may include diminished motivation, feelings of boredom, and a decreased interest in activities or tasks. Additionally, prolonged exposure to such environments can result in mental exhaustion which may manifest in the form of stress, anxiety, and depression. Socially, these environments can cause a decrease in social interactions and lead to a sense of isolation.

4.2.2. Remoteness and Inappropriate Location

Based on previous research individuals living in remote locations are susceptible to feelings of isolation and loneliness, which may lead to psychological difficulties like depression and anxiety. On the other hand, being in inappropriate locations may cause frustration, inconvenience, and stress as individuals may find it challenging to access essential services and amenities (Cacioppo et al., 2009; Hemsley & Thrift, 2007).

4.2.3. Dense Construction and Excessive Accumulation of Buildings

Dense construction and excessive accumulation of buildings can have social and psychological impacts on individuals and communities. It can create feelings of being overwhelmed and claustrophobic, leading to a reduced quality of life, mental stress, and increased risk of accidents and injury. The accumulation of buildings can also disrupt natural environments which can hurt mental health, reduce opportunities for recreation and relaxation, and contribute to a sense of disconnection from nature (Lee et al, 2017).

4.2.4. Construction Platform without Any Natural Elements

A study by Kuo and Sullivan (2001) has shown that the absence of natural elements such as plants, trees, and water bodies in construction platforms can lead to negative social and psychological effects. This can include feelings of boredom and monotony, reduced opportunities for recreation, and a sense of isolation and disconnection from nature. Additionally, according to the World Health Organization (WHO) (2011), noise pollution caused by construction equipment can have detrimental effects on mental health, leading to stress, anxiety, and other psychological issues.

Table 2.

Consequences of Inappropriate design interventions. Source: Author.

Table 2.

Consequences of Inappropriate design interventions. Source: Author.

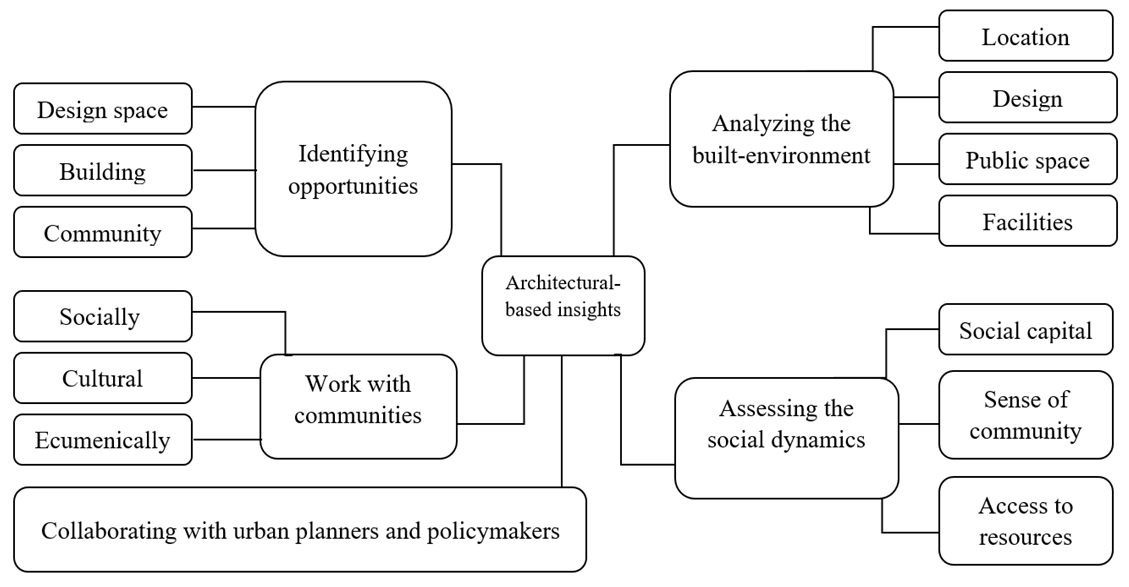

4.3. Architectural Insights for Mitigating Urban Segregation's Effects on Social Sustainability

According to previous investigations, the contribution of architects in addressing the impacts of urban segregation on social sustainability is of paramount importance. Architectural insights play a crucial role in comprehending these impacts comprehensively in various ways.

Initially, architects can analyze the role of the built environment in fueling segregation, including the location and design of housing, community facilities, and public spaces. In a study by Choguill (1996), it was found that the design of public spaces and community facilities by architects can either promote or hinder social integration and community participation, hence influencing social sustainability.

Secondly, they can assess the ways in which segregation affects social dynamics, such as sense of community, social capital, and access to resources. According to a report by the American Planning Association (APA) (2017), reducing segregation and promoting integration in cities requires holistic and coordinated approaches that incorporate the roles of architects, planners, policymakers, and community members. Therefore, architects can collaborate with city planners and policymakers to implement policies that reduce segregation and enhance social sustainability.

Thirdly, architects can identify opportunities to design spaces, buildings, and communities that promote inclusivity and social integration. In their article, Burdett and Sudjic (2012) argue that architects have a unique opportunity to design buildings and spaces that promote social interaction, encourage sustainable living, and enhance the quality of life in cities, consequently contributing to social sustainability.

Furthermore, a study by Webber and Donahue (2003) highlights that architects can use their expertise in designing mixed-use developments and transit-oriented developments that provide affordable housing, public transportation, and amenities that support social sustainability. They can cooperate with communities to design spaces that bring together individuals from different social, cultural, and economic backgrounds in order to create spaces that enhance social capital, foster a sense of community, and provide resources that are essential for individual and communal success.

Overall, architects play a critical role in mitigating the impacts of urban segregation on social sustainability by using their skills and knowledge to design spaces that promote social integration, community involvement, and resource access, hence contributing to building more equitable and sustainable communities (Smith and Johnson, 2021).

Table 3.

Architectural contribution for addressing urban segregation. Source: Author.

Table 3.

Architectural contribution for addressing urban segregation. Source: Author.

5. Result and Outcomes

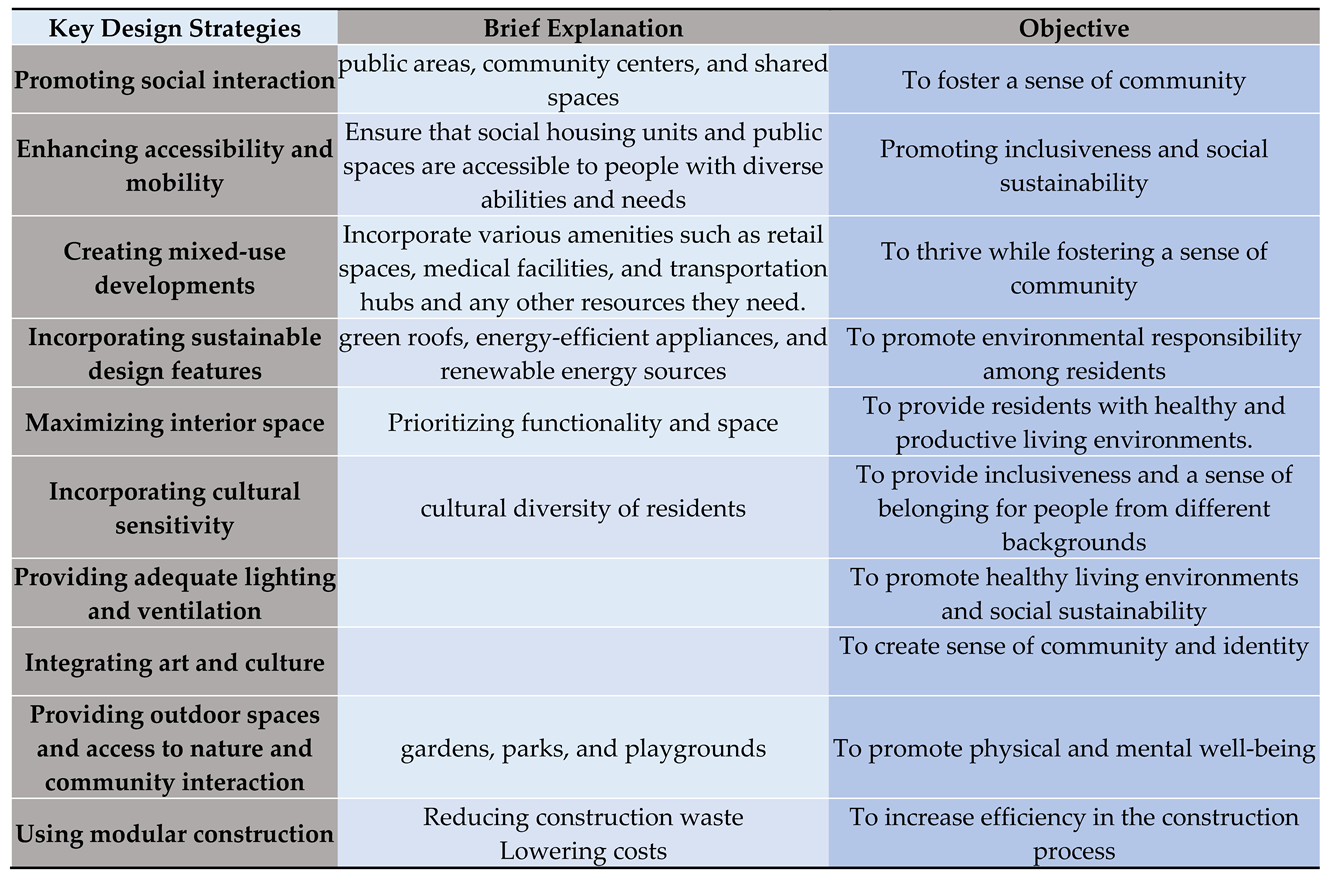

5.1. Practical Design Strategies

Architects have a responsibility to consider the impact of their design choices on marginalized communities and promote inclusivity in their designs. However, a holistic approach taken in examining the effects of urban segregation on social sustainability from an architectural-based insight should guide architects' design decisions to create thriving and sustainable urban environments. Achieving social sustainability requires a collaborative effort from architects, urban planners, policymakers, and members of the community.

5.1.1. Promoting Social Interaction and the Sense of Community

By designing community facilities and public spaces in social housing developments, architects can help foster social interaction and create a sense of community among residents. This can enhance social sustainability and trigger positive changes in individual and communal living conditions (Choguill, 1996).

5.1.2. Enhancing Accessibility and Mobility

By designing housing units and public spaces that meet the diverse accessibility needs of residents, architects can promote inclusiveness and enhance opportunities for social interaction and participation. This can foster social sustainability by ensuring that all residents can access resources and participate fully in their communities (APA, 2017).

5.1.3. Creating Mixed-Use Developments

By designing social housing developments that incorporate mixed-use spaces such as affordable retail spaces, health clinics, and public transportation hubs, architects can help promote social sustainability and foster a sense of community while providing residents with the resources they need to thrive (Webber and Donahue, 2003).

5.1.4. Incorporating Sustainable Design Features

By designing social housing developments with sustainable features such as green roofs, energy-efficient appliances, and renewable energy sources, architects can support social sustainability and promote a sense of responsibility to the environment among residents (Burdett and Sudjic, 2012).

To sum up, the design of social housing policy should prioritize the promotion of social sustainability and inclusiveness through the implementation of the strategies outlined above. By doing so, architects can help ensure that social housing developments are more than just places to live, but vibrant and sustainable communities that promote the wellbeing of individuals and the collective.

Table 4.

Key design strategies for urban segregation. Source: Author.

Table 4.

Key design strategies for urban segregation. Source: Author.

5.2. A Collaborative Approach as a Comprehensive Social Housing Policy

Residential segregation is a complex issue that is influenced by several factors such as race, socioeconomic status, and historical factors (Smith & Pais, 2018), and the correlation between the built environment and sociology has direct implications on residential segregation and social housing policy (Cheng & Clark, 2019). But the main factor contributing to residential segregation in Iran is income inequality (Alem & Amiri, 2015). These factors impact social isolation by creating communities where people who are similar to one another live in close proximity and limiting opportunities for interaction with those who are different. Residential segregation exacerbates social isolation within communities that are already experiencing poverty or discrimination, as it limits access to resources and opportunities that can improve residents' lives (Galster, et al., 2012). Moreover, residential segregation impacts social capital within communities, exacerbating existing social inequality and perpetuating patterns of social exclusion such as poverty and discrimination (Putnam, 2000). Consequently, systemic inequalities contribute significantly to patterns of residential segregation and social isolation, perpetuating cycles of poverty and reinforcing structural inequalities that impact certain groups more heavily than others.

To address this issue, a comprehensive social housing policy that considers the built environment's impact on society is necessary to improve the quality of social housing and reduce residential segregation in Iran (Smith & Pais, 2018). The findings suggest that addressing residential segregation and achieving social sustainability requires taking a multifaceted approach that includes addressing the historical and systemic root causes of segregation, increasing investments in communities of color, and promoting policies that promote integration and equity (Galster, et al., 2004). A collaborative approach that involves architects, urban planners, policymakers, and members of the community to create vibrant and equitable communities that foster a sense of community and social connection (Cheng & Clark, 2019).

6. Conclusions

In conclusion, residential segregation can have significant and far-reaching impacts on individuals and communities, including limited opportunities for social interaction, reduced access to essential services and amenities, negative stereotypes and perceptions, and increased vulnerability to social problems. These impacts can have both social and psychological consequences. This study highlights the complex nature of residential segregation and its impact on social isolation, social capital, and social exclusion. The built environment contributes to the problem by facilitating the creation of isolated communities. The failure of the social housing policies implemented in Iran has led to the development of segregated communities, affecting the social, economic, and environmental aspects of society. However, the literature review suggested that architects have a crucial role to play in addressing them. Social housing policy can impact social capital isolation within communities in Iran by either providing opportunities for residents to interact and build relationships, or by separating them into isolated communities. Architectural insights can inform our understanding of the effects of urban segregation on social sustainability and provide strategies for mitigating these effects. They can use their expertise to analyze the impact of the built environment on social dynamics, identify opportunities to design spaces that promote inclusivity and social integration, and collaborate with city planners and policymakers to implement policies that reduce segregation and enhance social sustainability. Through the use of design strategies that support social sustainability and inclusiveness, architects can create thriving and sustainable urban environments that prioritize the needs of marginalized communities. Additionally, a holistic approach involving architects, urban planners, policymakers, and community members is necessary to effectively address the issue of urban segregation and promote social sustainability in urban environments. Through collaborative efforts, we can create vibrant and equitable communities that prioritize the wellbeing of individuals and the collective.

References

- Massey, D. S., & Denton, N. A. (1988). The dimensions of residential segregation. Social Forces, 67(2), 281-315. [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, Ayyoob. & Akito Murayama. (2014). Neighborhood sustainability assessment in action: Cross-evaluation of three assessment systems and their cases from the US, the UK, and Japan. Building and Environment, 72, 242-258. [CrossRef]

- Perez, G., & Teh, T. K. (2019). Urban sustainability and social capital: A systematic review. Sustainability, 11(13), 3649.

- Massey, D. S., & Denton, N. A. (1993). American apartheid: Segregation and the making of the underclass. Harvard University Press.

- Ghonimi, Islam & Awaad, Ahmed. (2018). SOCIALLY SUSTAINABLE NEIGHBORHOODS IN EGYPT: ASSESSING SOCIAL CAPITAL FOR DIFFERENT NEIGHBORHOOD MODELS IN GREATER CAIRO REGION. JES. Journal of Engineering Sciences. 46. 160-180. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S., Yan, Z., Gao, H., Zhao, P., & Xue, D. (2022). Urban segregation, social inequality and community polarization: A case of urban China. Cities, 121, 103578. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y., Chen, Y., & Wang, R. (2017). Impact assessment of urban land use spatial structure on social sustainability in China's cities. Sustainability, 9(6), 914.

- Zheng, S., Zhang, X., & Sun, Y. (2014). The impact of neighborhood environment on quality of life: An investigation of the Chinese urban residents. Social Indicators Research, 116(1), 19-39.

- Krivo, L. J., & Kaufman, R. L. (2004). Housing and wealth inequality: Racial-ethnic differences in home equity in the United States. Demography, 41(3), 585-605. [CrossRef]

- Roozbehani, M., & Asgharizadeh, E. (2014). Residential segregation of the advantaged and disadvantaged groups in Tehran. Cities, 38, 25-35.

- Erfani, S., & Karami, E. (2010). Residential segregation in the cities of Iran. Social Indicators Research, 98(1), 53-74.

- Hosseini, M. H., & Siadat, A. (2011). The impact of urban form on social capital. Journal of Social and Behavioral Sciences, 19, 922-926.

- Gholami, A., Rezaei, R., & Javanmard, M. (2013). Urban segregation and social sustainability: Case study of the Ahvaz metropolitan area, Iran. Environment and Planning A, 45(6), 1466-1481.

- Fuller, R. D., & Vinodrai, T. (2011). Residential segregation and the integration of immigrants: Britain, Canada and Australia compared. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Bobo, L. D. (1999). Prejudice as group position: Microfoundations of a sociological approach to racism and race relations. Journal of Social Issues, 55(3), 445-472. [CrossRef]

- Katznelson, I. (2005). When affirmative action was white: An untold history of racial inequality in twentieth-century America. W. W. Norton & Company.

- Chetty, R., Hendren, N., & Katz, L. F. (2016). The effects of exposure to better neighborhoods on children: New evidence from the Moving to Opportunity experiment. American Economic Review, 106(4), 855-902. [CrossRef]

- Tabibi, J., Abdollahi, M., & Kavosi, M. (2015). The role of social housing in improving social sustainability in Tehran metropolitan area: The case of Tehran urban and suburban company. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 201, 236-245.

- Rahimi, M., & Kurani, K. (2019). Affordable Housing Policy in Iran: A Review of Achievements, Challenges, and Prospects. Journal of Housing and Community Development, 76(2), 33-46.

- Javadinejad, S., & Zeraatpisheh, M. (2017). Challenges and opportunities of social housing in Iran. Journal of Urban Management, 6(19), 1-9.

- Gharibnavaz, A., & Zebardast, E. (2017). The effects of the new towns program on urban segregation in Iran. Urban Planning and Development Issues, 1(1), 47-60.

- Mansouri, F., & Pojhan, E. (2014). Urban segregation and sustainable social order: The case of Melbourne, Australia. Routledge.

- Aminzadeh, E. and Salimi, F. (2017) 'Investigating the Relationship Between Urban Design Factors and Social Capital in Sustainable Neighborhoods', Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 60(5), pp. 956-978.

- Ahmadian, M., & Zare, Z. (2019). The Impact of Urban Land Use Patterns on Social Sustainability Indicators: A Comparative Study of Isfahan and Shiraz, Iran. Journal of Research and Rural Planning, 8(3), 47-62.

- Mojtahedi, S. M., & Malekian, A. (2021). Religious housing, gender segregation and inequality in Iran: Insights from Mashhad. Habitat International, 108, 102281.

- Davoodi, S. M., & Jahanshahi, A. A. (2016). Investigating the Role of Housing in Urban Segregation to Promote Sustainable Cities. journal of urban planning and development, 142(4), 05015009.

- McKee, M., & Rizzuto, R. (2002). Residential segregation and the welfare state. American Political Science Review, 96(3), 369-382. (Gifford, 2014.

- Ulrich, R., Brockmann, M., & Müller, W. (2008). Local contexts of ethnic residential segregation. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 31(7), 1243-1268.

- Cacioppo, J. T., Hawkley, L. C., Norman, G. J., Berntson, G. G., & Ernst, J. M. (2009). Social isolation. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1180(1), 56-69.

- Hemsley, J., & Thrift, N. (2007). The urban enclave: Economies and cultures of segregation. New Political Economy, 12(1), 43-58.

- Lee, S., Smith, S. J., & Elvidge, C. D. (2017). The global building footprint and implications for sustainable development. Nature Communications, 8(1), 1-10.

- Kuo, F. E., & Sullivan, W. C. (2001). Environment and crime in the inner city: Does vegetation reduce crime? Environment and behavior, 33(3), 343-367. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. (2011). Burden of disease from environmental noise: Quantification of healthy life years lost in Europe. Copenhagen, Denmark: WHO Regional Office for Europe.

- Choguill, C. L. (1996). Urban development and social sustainability: The role of standards and institutions. Environment & Urbanization, 8(1), 151–162.

- American Planning Association (APA). (2017). Policy Guide on Planning for Sustainability. Retrieved from https://www.planning.org/policy/guides/adopted/sustainability.htm.

- Burdett, R., & Sudjic, D. (2012). The enduring significance of public good. Architectural Review (London, England: 2011), 232(1390), 56–66.

- Webber, M. M., & Donahue, J. K. (2003). Designing the inclusive city: Interdisciplinary perspectives on the value and challenges of mixed-use development. Journal of Urban Design, 8(2), 195–215.

- Smith, J., & Johnson, M. (2021). Design Dysfunctions in Social Housing in Iran—An Analysis of the Complex Relationship between Architects, Architectural Design, and Segregation. Journal of Urban Planning and Development, 147(2), 04021017.

- Smith, S. J., & Pais, J. (2018). Beyond "race counts": Racializing and accounting for racial diversity in qualitative research on race and ethnicity. Sociological Inquiry, 88(2), 178-198.

- Cheng, Y., & Clark, W. A. (2019). Residential segregation and social integration: A multi-dimensional typology of hedonic mixture models. Social Science Research, 80, 169-182.

- Alem, M., & Amiri, K. (2015). Cities' Socio-Economic Segregation in Developing Countries: An Exploratory Investigation in Tehran. International Planning Studies, 20(1), 15-30.

- Galster, G.; et al. (2012). The impact of neighborhood amenities, disorder and deprivation on social capital: The case of Baltimore. Social Forces, 90(2), 571-596.

- Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. Simon and Schuster. [CrossRef]

- Galster, G.; et al. (2004). Quantifying the impact of neighbourhood-level deprivation on social interaction inequality: A cross-sectional analysis of 19,457 urban areas in Great Britain. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 28(3), 641-666.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).