1. Introduction

Technology advancements in the area of energy storage are expected to accelerate the transition to a global energy sector with a significant minimization of air pollutant emissions by limiting the combustion of fossil fuels. Inter alia, some key features that will be enabled are the maximum possible exploitation of renewable energy sources (RES), through temporal power flexibility, and the electrification of mobility. The ongoing progress in research, industry, and policymaking emerge lithium-ion battery as the main solution in the field of energy storage.

From a technological point of view, the turning point for the establishment of lithium-ion battery as a mass energy storage option is marked by certain breakthroughs; i) the significant increase in battery energy and power density and, therefore, the reduction of raw material cost, ii) the optimization of the life-cycle logistics of raw materials in a sustainable and environment-friendly manner, and, iii) the optimal integration of batteries within broader energy systems, such as electric vehicles (EVs), distributed generation plants and large continental power grids. A key process in succeeding the latter is creating an efficient and accurate framework in battery modeling.

Regarding this process, the battery model should satisfy the need to be able to be coupled with models of multi-domain physical systems. For example, an EV includes mechanical, electrical, electronic, and hydraulic subsystems that should be studied, on the level of an integrated system. Authors of [

1] denote two approaches to perform multi-domain modeling; co-simulation of specialized professional software for each subdomain or utilization of a unified multi-domain modeling language. The second approach offers the advantageous feature of convenient coupling between system models. The language Modelica belongs to this category [

2].

The most commonly used battery models are i) the electrochemical model [

3], ii) the data-driven model (e.g. artificial neural network – ANN) [

4], and, iii) the equivalent circuit model (ECM) [

5,

6]. The battery is integrated within broader systems, such as in the case of EVs, through a battery management system (BMS) that targets optimal performance in terms of energy performance, safety, and remaining lifetime. The most commonly used battery modeling technique in BMS is the ECM, which enables the representation of the dynamics of battery operation without diving into complex electrochemical internal phenomena, ensuring, however, adequately high accuracy within its applicable scope. This is achieved through the limitation of, primarily, the large computational power needed by the electrochemical models and, secondly, the large experimental datasets needed by ANN models.

ECM utilizes an equivalent electric circuit to capture the battery response dynamics. The circuit encompasses parameterized components of a voltage source, a series resistance, and multiple RC branches. In [

7], an ECM with a capacity degradation component has been developed with Modelica for a lithium iron phosphate (LFP) Li-ion battery cell. Manufacturer datasheets and test cycles have been used to validate the models. The simulations refer only to a single-cell operation and are not focused on the battery pack and its integration within an EV. Bairwa et al. [

8] have designed a battery model to create an EV powertrain system model with MATLAB Simulink in order to evaluate the performance of different combinations of possible battery and motor technologies. However, the battery model has been designed at a pack level with the use of a series resistance and only two capacitors. On top of that, the applied load refers to a short period of 20 seconds and, most importantly, it is not related to any standardized driving cycle. In [

9], the authors have developed an integrated EV system model in MATLAB Simulink to study the behavior of the Mercedes-Benz EQS 350 under the Worldwide Harmonized Light Vehicles Test Procedure (WLTP) driving cycle, but the effect of the battery pack is completely ignored. Meszaros et al. [

10] have considered a battery cell model with 1 RC branch for an EV powertrain system model, along with vehicle dynamics, electric motor, and power electronics models, to examine different options in braking control for the maximization of recuperated energy. The authors have performed simulations for the UDDS driving cycle; though the outdated ADVISOR database for Toyota Prius and guess values have been utilized for the selection of system parameters. Adegbohun et al. [

11] have used MATLAB/Simulink to model and simulate an EV powertrain and results have been compared against drive cycle test measurements. However, a significantly simplified battery model has been used, neglecting transient voltage response and dependence on variable SoC and temperature. In [

12], a commercial Modelica library devoted exclusively to battery modeling at the cell level is presented. However, the parameter estimation stage is only available through the purchase of proprietary Battery and Optimization libraries developed by Modelon and detailed verification results are not shared. Qin et al. [

1] have reproduced an ECM battery model of an LFP battery cell with Modelica language, involving hysteresis effects and a third-order circuit. The model has been validated after the application of the Urban Dynamometer Driving Schedule (UDDS) driving cycle with an average error of 0.23%, yet only at a cell level. At an EV system level, only the theoretical mileage is reported as a verification indicator, and the deviation between this value and the simulation results equals 0.54%.

This work focuses on filling in the aforementioned research gaps of recent literature in developing ECM battery models for EV applications, with the utilization of physical modeling languages. This is attained through the development of a second-order ECM in Modelica for 4 commonly used Li-ion cells with different positive electrode materials. To ensure acceptable model accuracy for battery integration into EV applications, an EV powertrain system is modeled, and the simulation results are compared against a MATLAB reference application, for verification purposes. The battery load profile is determined by importing the widely approved FTP75 driving cycle. The applied profile tests the developed model in actual applications and can provide sufficient information about battery and vehicle energy performance, such as the remaining state of charge (SoC), energy consumption, and fuel economy. The monitored output variables have been compared against the corresponding results of the MATLAB application at different powertrain points, i.e. the battery pack, the motor, and the entire EV body. Creating a tested virtual EV representation model with Modelica language that covers a wide range of battery chemistry type options, paves the way for the exploration and evaluation of the energy performance of numerous battery-powertrain coupling configurations, in terms of specifications and architecture.

In a nutshell, the main contributions of this work compared to previous studies, lie on:

the creation of battery models at the cell level using the second-order ECM representation technique

the integration of the battery model with the other subsystems of the broader powertrain system in an EV-level application that is exclusively designed with Modelica language

the utilization of the standardized FTP75 driving cycle for evaluating battery energy performance

the verification of the model results against a well-established MATLAB EV reference application

This paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 describes the theoretical background and the development of the modeling process. The setup and the results of model verification are presented in

Section 3. Finally, the conclusions of this work are consolidated in Section 4.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Equivalent Circuit Model Background

The most widespread battery cell modeling technique that ensures a good trade-off between accuracy and computational complexity is the ECM [

5,

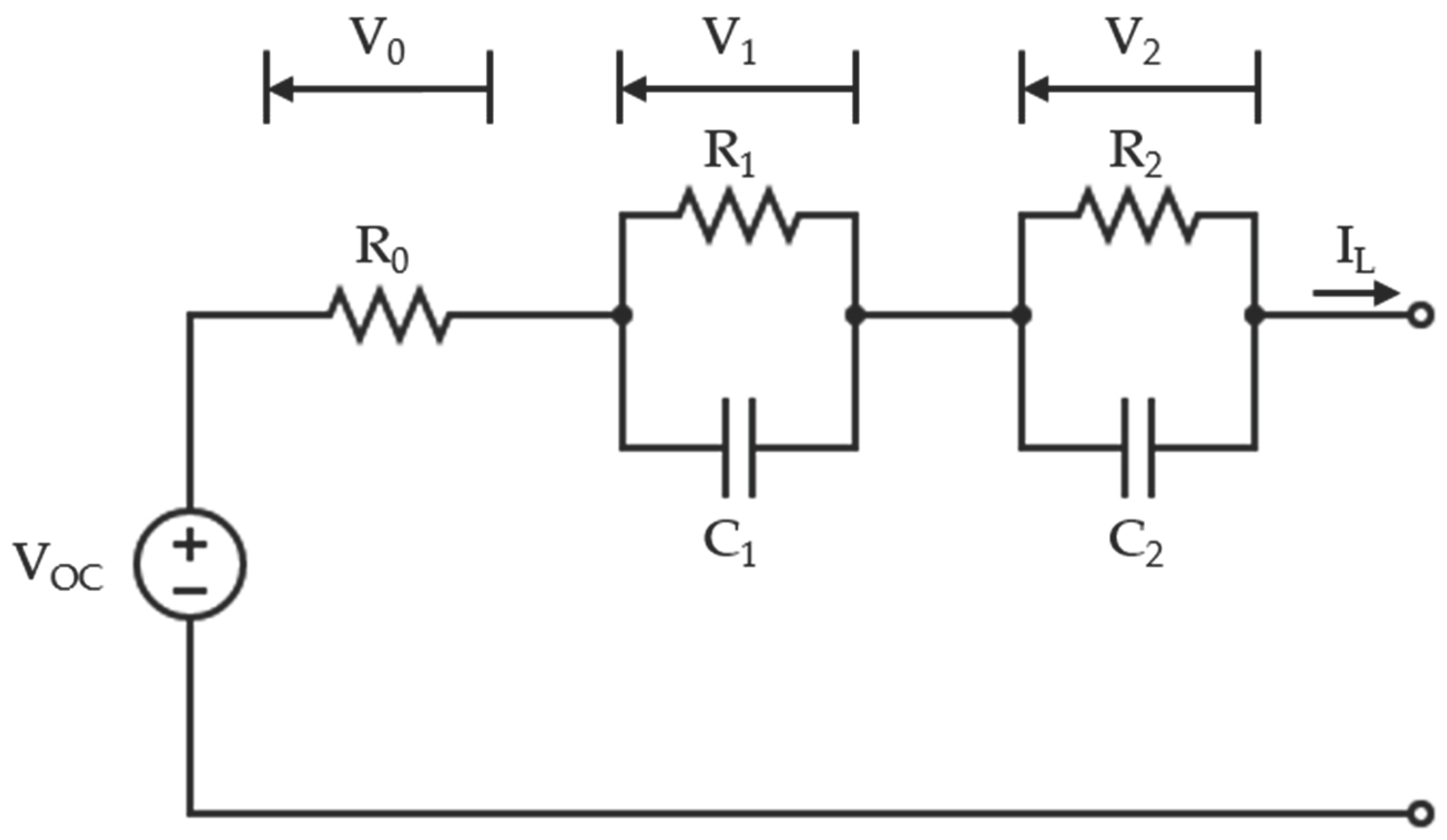

6]. This combination is a key element for reproducibility within effective BMS, in which high accuracy and minimum possible computational time must be ensured. ECM technique allows the representation of the complex internal electrochemical phenomena of the battery cell through an equivalent circuit of electrical components, namely a voltage source, a single resistor, and -n- parallel resistor-capacitor subcircuits, connected in series. The ECM order number -n- can vary to achieve the desired characteristics of each application, but in general, the second-order (n=2) ensures an effective balance between complexity and accuracy. The topology of a second-order equivalent electric circuit is presented in Figure 5.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the topology of a second-order Equivalent Circuit Model.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the topology of a second-order Equivalent Circuit Model.

The voltage source of the circuit is denoted as VOC in the figure circuit and is named open-circuit voltage, whereas the voltage drop V0 across the series resistance, which is denoted as R0 in the circuit, represents the instantaneous voltage drop due to an applied current profile and the transient voltage drop V1+V2 across the 2 RC branches, which are denoted as R1-C1 and R2-C2 in the circuit, is captured by the 2 corresponding time constants introduced and is connected with diffusion effects. IL is the current supplied by (positive) or injected to (negative) the battery cell through its terminals.

Characterization tests may include i) the capacity test, ii) the pulse discharge test, and iii) the hybrid pulse power characterization (HPPC) test. Voltage response is monitored, and the measurements are utilized for parameter fitting. A detailed description of the implementation of the parameter extraction process through experimental measurements has been given in [

13]. Tran et al. [

14] have recently published the parameter datasets extracted from measurements of four different lithium-ion battery chemistry types. These chemistry types classified by the positive electrode material, are lithium iron phosphate (LFP), lithium manganese oxide (LMO), lithium nickel cobalt aluminum oxide (NCA), and lithium nickel manganese cobalt oxide (NMC). The authors have also proceeded to the validation of the battery model for each chemistry type through 2 different applied current profiles. The extracted OCV-SOC curves and the parameter lookup tables for each lithium-ion battery chemistry are retrieved from this source and are reproduced in the current study. An important aspect is that these cells refer to 4 chemistry types of battery cells that are commonly used in EV battery applications. This is an important aspect for the reproduction of the model developed in this research work for a wide range of applications with different operating requirements (e.g. high-power or high-energy battery cells could be selected depending on the application).

The specifications of the four cells are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Cell specifications for each chemistry type [

14].

Table 3.

Cell specifications for each chemistry type [

14].

| Chemistry |

Manufacturer |

Cell name |

Nominal capacity (mAh) |

Nominal voltage (V) |

Voltage range (V) |

| LMO |

EFEST |

IMR18650V1 |

2600 |

3.70 |

2.50–4.20 |

| LFP |

K2 Energy Solutions, Inc. |

LFP26650P |

2600 |

3.20 |

2.00–3.65 |

| NMC |

Samsung SDI |

INR18650-20S |

2000 |

3.60 |

2.50–4.20 |

| NCA |

Panasonic |

NCR18650B |

3200 |

3.60 |

2.50–4.20 |

The equation set of the second-order ECM is as follows:

2.2. Battery Model with Modelica

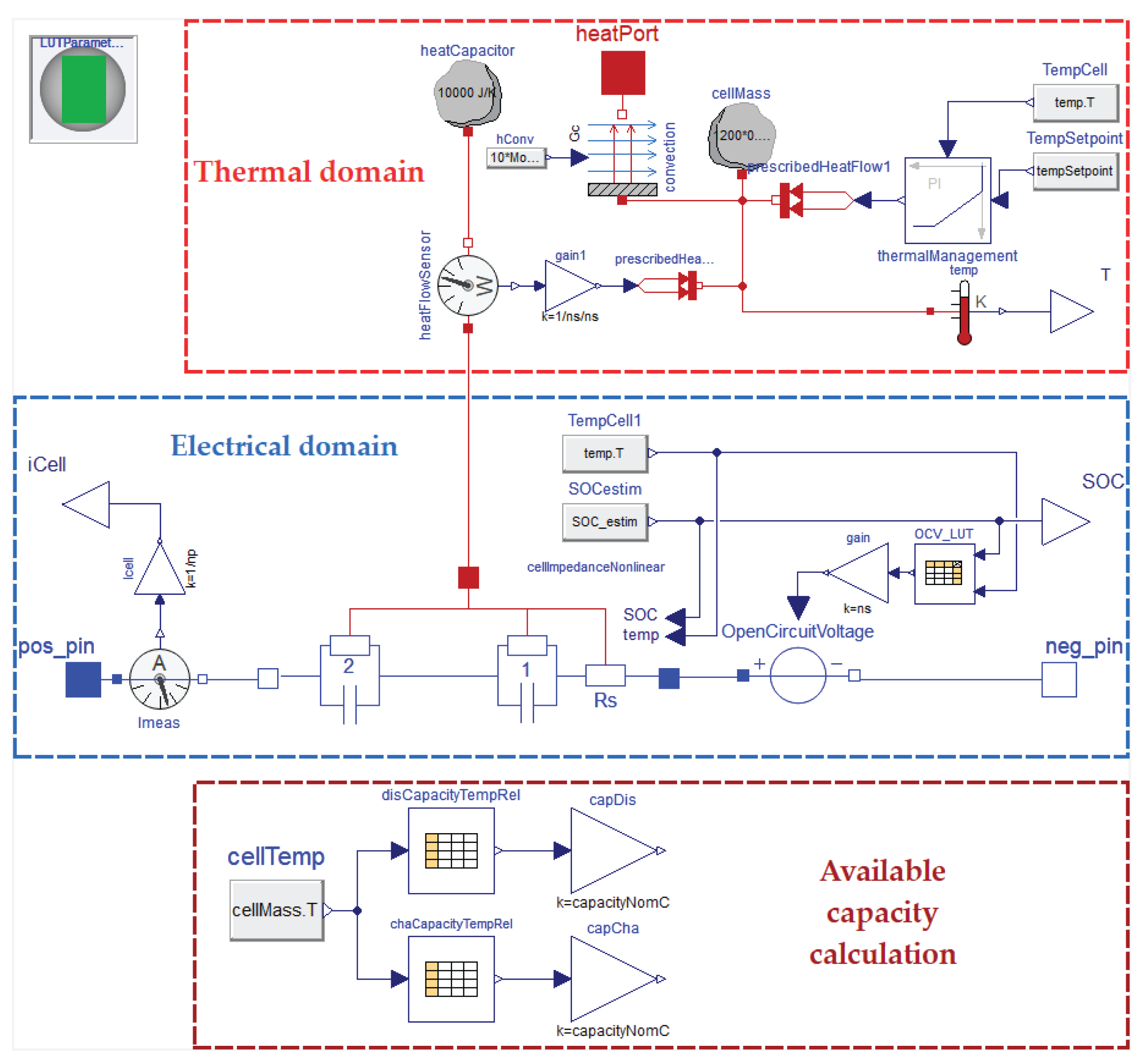

The graphical representation of the model of a single cell developed with Modelica within the Dymola user interface is presented in

Figure 2. In the electrical domain, a variable voltage source component is used to incorporate the open-circuit voltage, whereas the components of a series resistance and 2 RC branches correspond to the R

s and R

1C

1, R

2-C

2 circuit elements, respectively, according to the notation of

Section 2.1. The battery terminals correspond to the positive and negative pin. SoC is continuously estimated based on the applied terminal current and available capacity varies depending on the cell temperature and whether a charging or discharging operation is underway, as can be seen in the highlighted available capacity calculation area. In the thermal domain, heat is stored through a heat capacitor with a mass equal to the battery cell mass, whereas heat transfer with the surroundings takes place through the convection mechanism. The cooling load for keeping the temperature value between the desired levels is calculated through a PI controller. The cell quantities are scaled up to the entire pack level, based on the number of cells connected in series and in parallel within the battery pack configuration. An alternative option supported by the developed models is to automatically create as many cell models as the involved battery cells and make the predefined connections. However, since capacity imbalance between cells is neglected in this study, the scaled model is used.

An additional remark for future model replication is that even though users currently can select the lookup table parameters between the 4 available chemistry types, the modeling technique followed allows the extension of the model application to account for any extracted battery parameter dataset and, hence, any cell chemistry type and specifications.

2.3. EV Model with Modelica

To verify the developed battery model, an EV application has been selected as a test case. For this purpose, the recently published and well-documented MATLAB/Simscape EV reference application [

15] is selected for benchmarking the developed models, among several available software solutions for EV simulation. The selected application focuses on EV system-level simulation, taking into account all of its powertrain and control subsystems.

These include i) the driver’s control actions to close the gap between the requested and the actual vehicle velocity, ii) the controllers of the battery management system (BMS) that ensure operation within allowed technical limits, iii) the power recovery through regenerative braking, iv) the EV powertrain including physical models of the battery pack (array of cells connected in series and in parallel), the electric motor, the electric drive and the mechanical drivetrain of the vehicle.

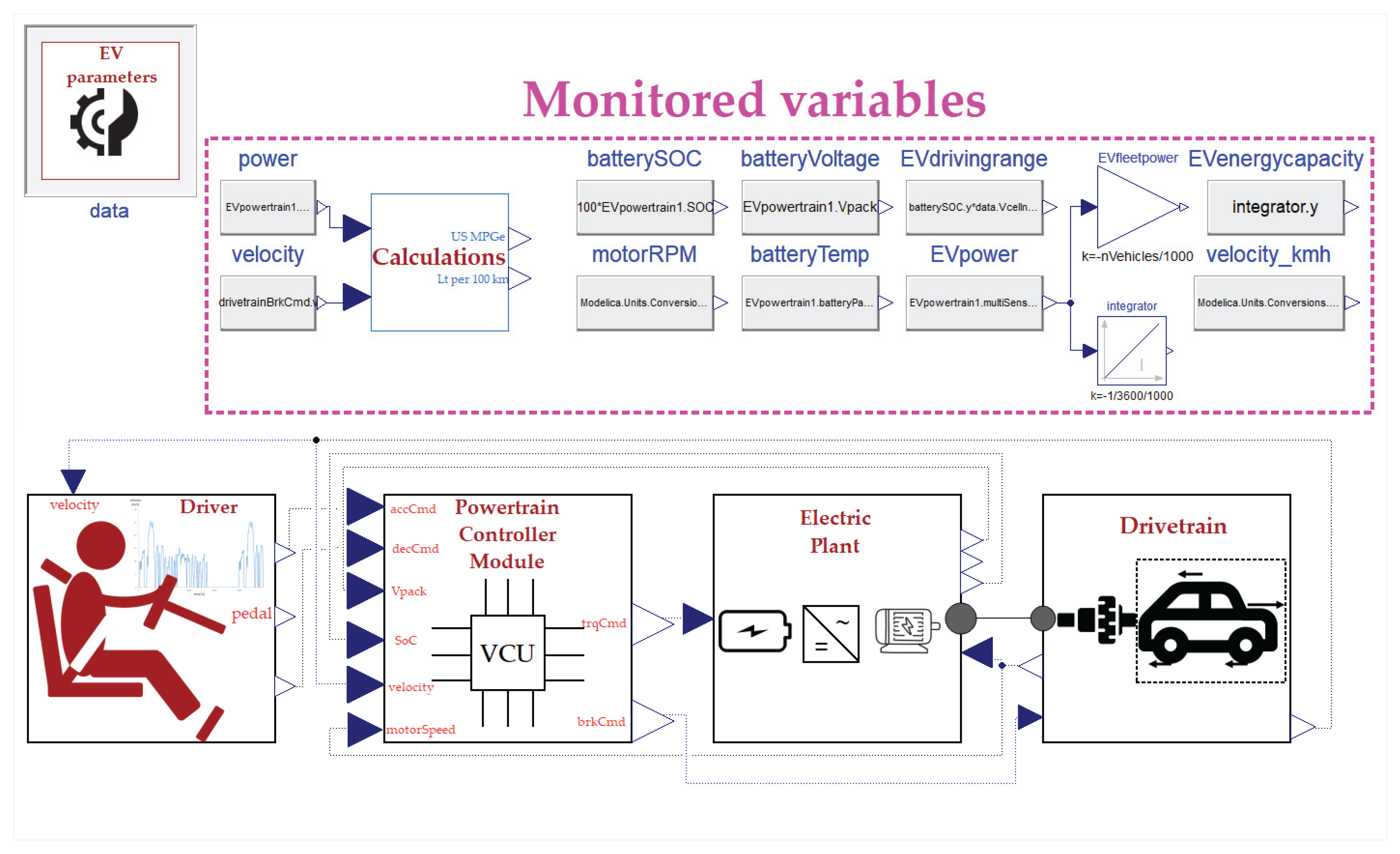

The EV system-level model is presented in

Figure 3. The model consists of the subsystems of the driver, powertrain control module, electric plant, and drivetrain. Based on the input velocity profile, the controllers actuate on the EV powertrain, which in turn transfers the required power to the vehicle drivetrain.

2.3.1. Driver Subsystem

The driver subsystem, models the user response to the requested velocity profile through a proportional controller. A normalized signal of the pedal position command is adjusted to minimize the error between the velocity profile and the measured velocity of the vehicle body. These signal values range from -1 to 0 when decelerating and from 0 to 1 when accelerating. The output command is fed to the powertrain control unit.

2.3.2. Powertrain Control Module Subsystem

The Powertrain Control Module (PCM) is the operation control center of the EV. Based on the requested pedal position, which is received as input from the driver subsystem, the torque that should be applied by the motor concerning the operating limits is produced as the output. Intermediate blocks are designed to limit discharge or charge power according to SoC and current limits and to arbitrate torque according to the wheels’ rotational speed. Moreover, a power management algorithm is incorporated into the PCM block. Except for complying with the power limits, it is responsible for the estimation of the required electric power to supply the necessary mechanical power based on the motor efficiency map. The efficiency map of the EV motor used for the simulations is retrieved from predefined tables of the MATLAB application and is plotted in

Figure 4.

Regarding deceleration, based on the deceleration normalized command (-1 to 0) the brake pressure that should be applied to the wheels is calculated. Next, the maximum available regenerative torque is calculated and exploited for motor braking. The mechanical parts of the transmission system and the dependence of the regenerative torque on the vehicle's instant speed are considered. The regenerative torque limits the torque applied by the brake on the wheel during deceleration. The regenerative torque is subtracted from the total required brake torque and the residual is an output torque that feeds the drivetrain subsystem, where it is applied to the vehicle wheels.

2.3.3. Electric Plant Subsystem

The electric plant subsystem models all the vehicle components engaged in power transfer, i.e. the battery, the power converter, and the motor. The battery pack model is based on the battery cell model described thoroughly in

Section 2.1 and can provide instantaneous response estimations of battery voltage and SoC for the selected cell specifications (e.g. configuration, chemistry type, capacity). Inside the electric drive subsystem, the operation of both motor and power converter are incorporated. Namely, depending on the instantaneous value of the wheels’ rotation speed, the requested torque is limited. A tabular characteristic torque-speed curve should be imported into the model.

Furthermore, the motor efficiency map, also used in the PCM unit, is used to consider the electric drive losses. The final power demand consumption is modeled by a variable resistance, continuously adjusted by an integrator, and connected with the battery pack terminals.

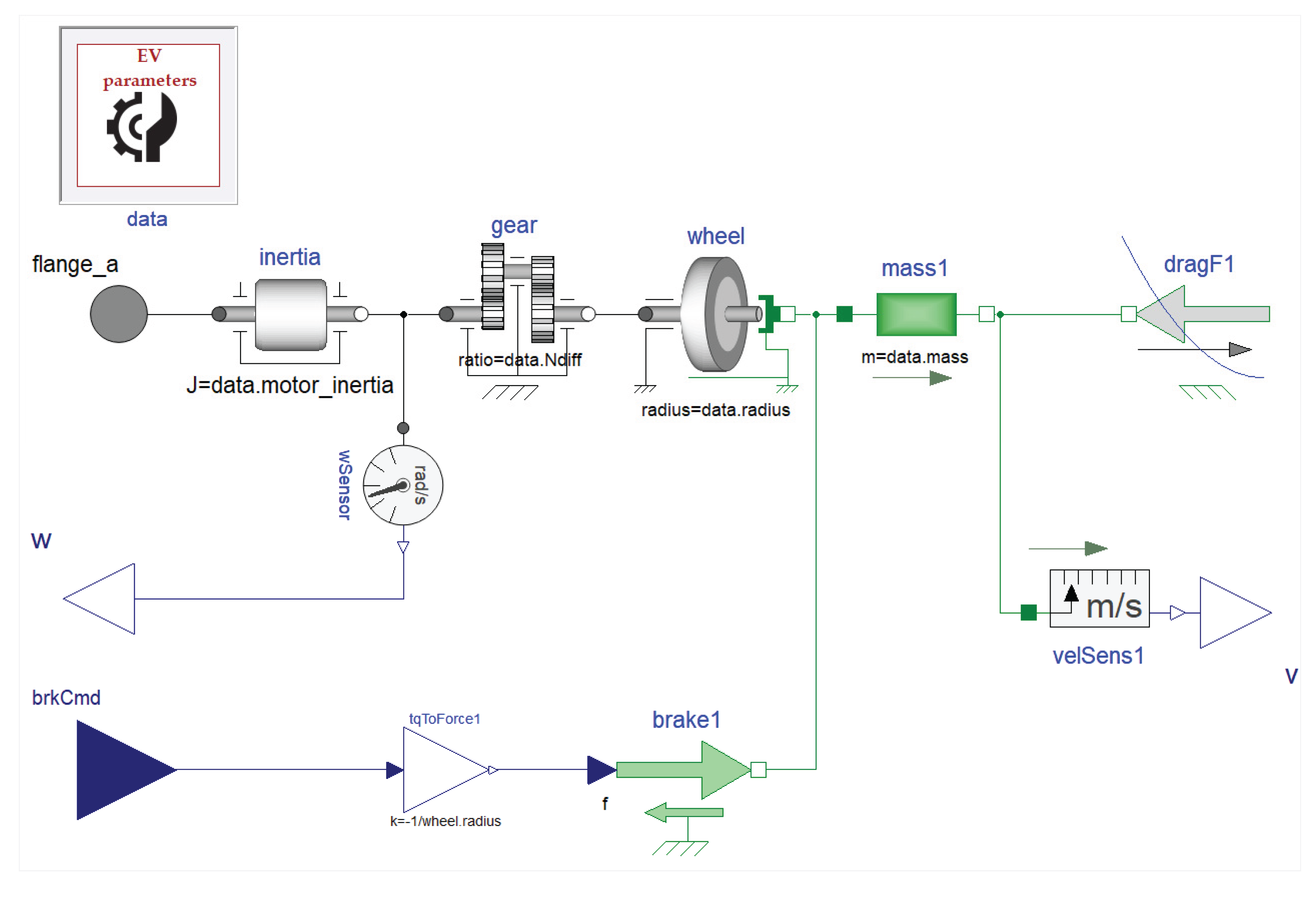

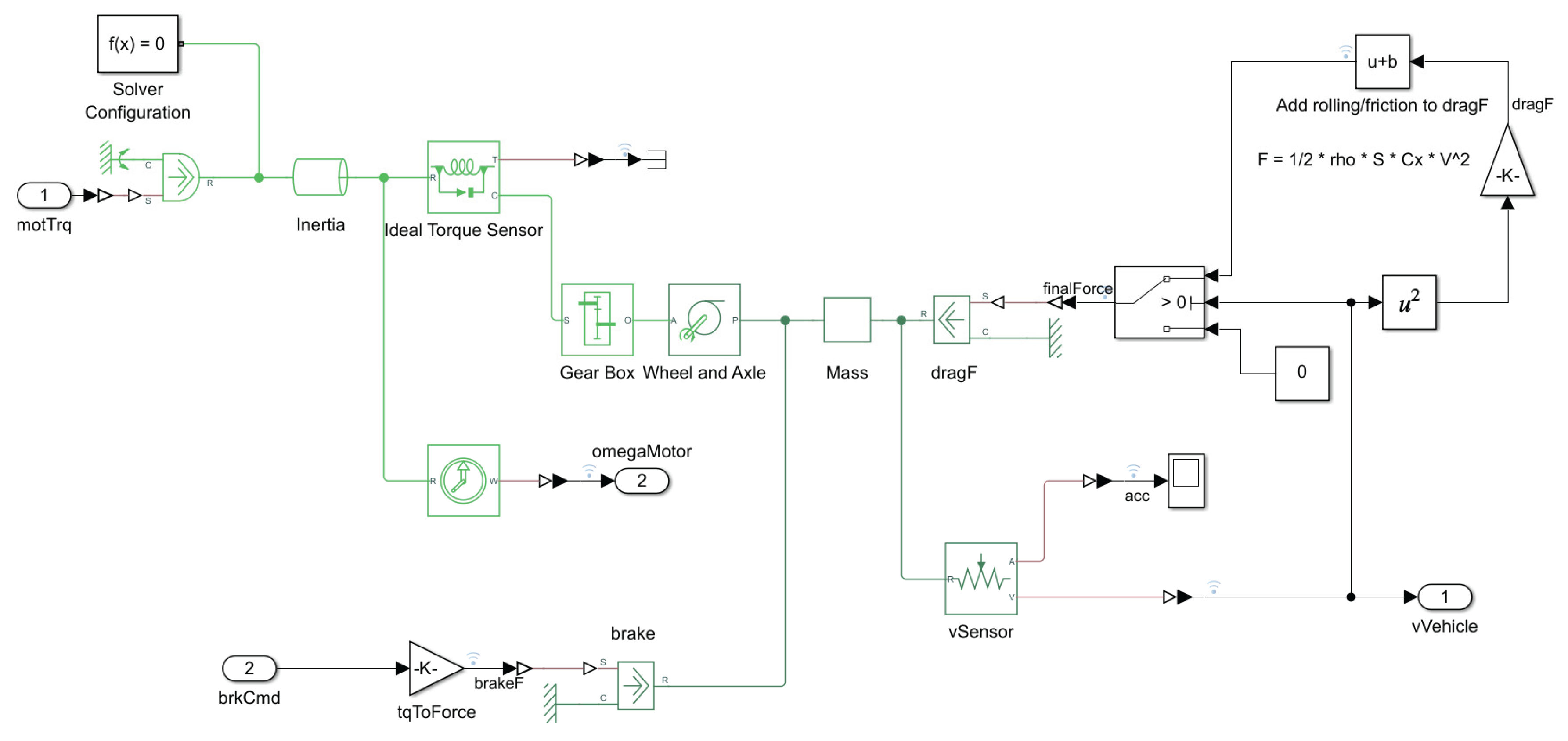

2.3.4 Drivetrain Subsystem

To proceed with the EV system simulation, a model for the drivetrain is also necessary. However, since the special focus of this study is given to the electric propulsion system the drivetrain model can be kept simple and effective in terms of computational time. The applied forces in the vehicle body include the motor tractive force, the braking force, the aerodynamic drag force, and the rolling resistance force. A flat ground is considered, neglecting the effect of gravitational force on vehicle motion. The corresponding model is built with the use of components of the Modelica Standard Library 4.0.0 [

16] by extending the main idea of the drivetrain model of the EHPT Modelica library [

17] and is presented in

Figure 5.

2.4. EV Model Modifications with MATLAB Simscape

To move forward with a meaningful comparison of the two software EV system-level models, a prerequisite step is to apply the necessary simplifications to the detailed existing drivetrain model of the MATLAB EV application to align with the Modelica model that is described in

Section 2.3. In the available model of MATLAB application, 3 degrees of freedom are considered for vehicle body motion and whether differential axle coupling is made to the front or rear wheel is taken into account to give high-accuracy quantity estimations for the interacting mechanical parts. To avoid implying errors in the verification process due to complex modeling of mechanical components, a less thorough approach is followed. As a result, a simplified model is developed within the Simulink environment with the utilization of the Simscape libraries and is presented in

Figure 6.

3. Results

3.1. Model Verification Setup

As mentioned in

Section 2.3, a MATLAB EV reference application has been selected to verify model results. The Federal Test Procedure FTP75 driving cycle, introduced by the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) [

18], has been used to import the user velocity profile for model verification. Furthermore, the model input parameters and assumptions must be common in both software applications. The input data of both applications are categorized as follows:

The parameters used for the simulations in both software to achieve a meaningful comparison of the results are listed in

Table 2. All of the required inputs are retrieved by a combination of available data from the MATLAB application and the EHPT Modelica library.

Moreover, to proceed with a proper evaluation of the simulation results, some critical quantities have been selected to verify the accuracy of the developed models at certain system points. These include:

the vehicle velocity against the requested velocity profile (driving cycle),

the deviation between simulated and requested vehicle velocity,

the current injected to/supplied by the battery by/to the motor,

the power injected to/supplied by the battery by/to the motor,

the battery pack state-of-charge,

the voltage at battery pack terminals,

the torque applied by the motor,

the motor rotational speed,

the fuel economy

the brake, drag, and rolling resistance forces applied to the vehicle body

3.2. Model Verification Results

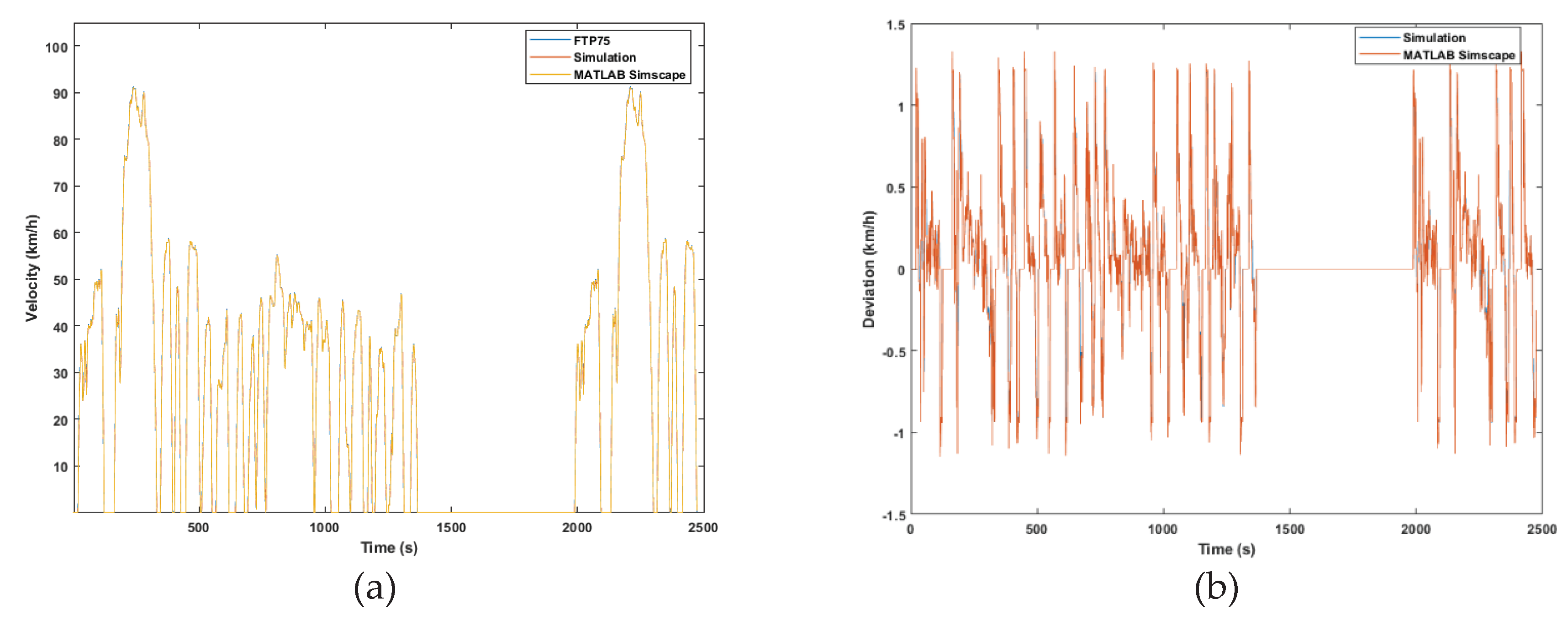

The key verification results of the battery models are presented in this section. Results at all EV system points indicate a strong match between the results of the developed models and MATLAB reference application. More specifically, in

Figure 7a, the simulated vehicle velocity is plotted against the requested velocity profile, imported by the FTP75 driving cycle, and the corresponding MATLAB results. First of all, the operation of the designed control algorithm and all subsystems ensures that the desired driving behavior is achieved through the developed models. In

Figure 7b, the relatively low values of instantaneous deviation between the desired and output velocity can be observed, leading to a strengthened model validity. The maximum absolute value of 0.34 m/s is equivalent to 1.22 km/h, which can be considered acceptable considering that the latency of the driver’s response is taken into account.

In

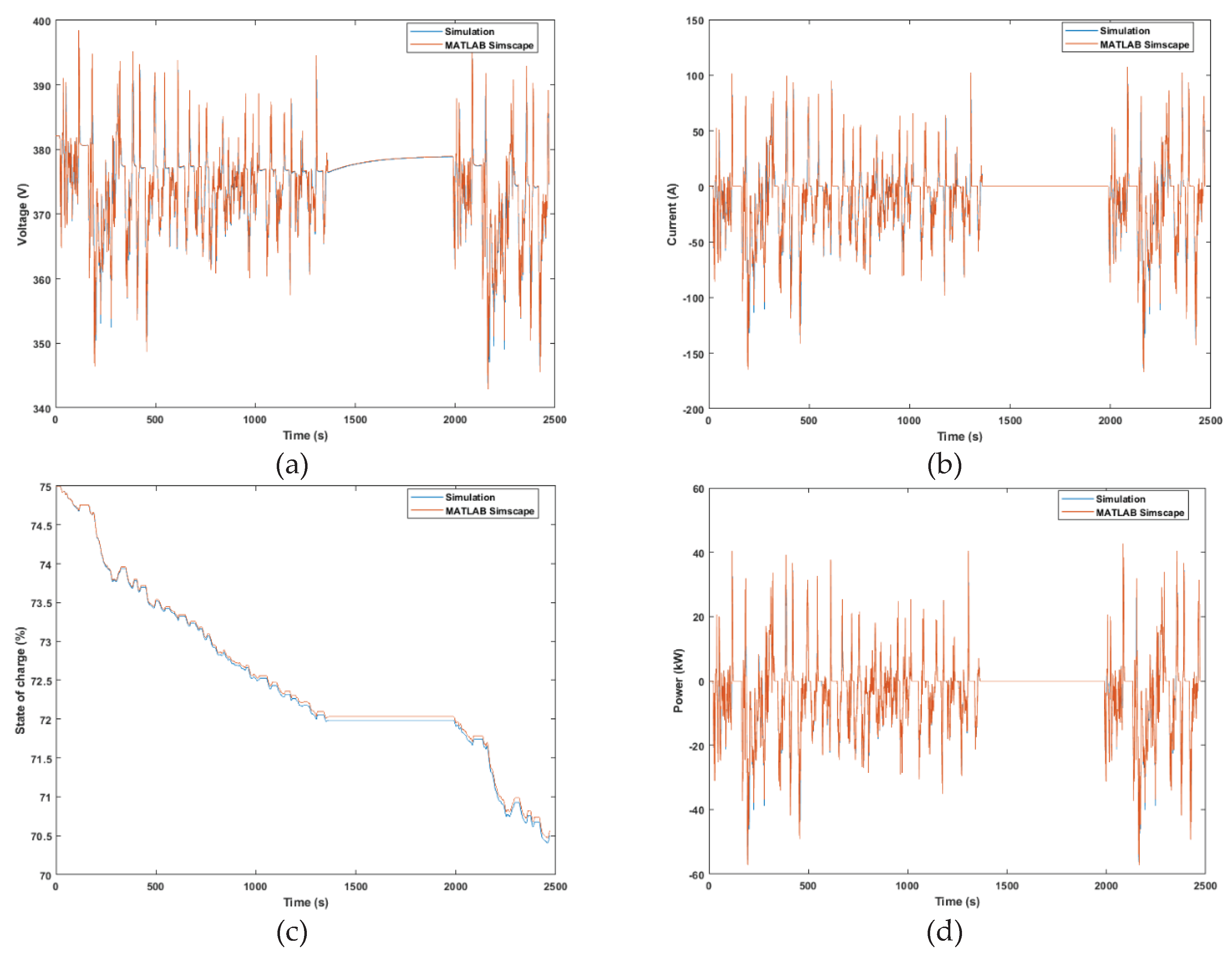

Figure 8, the simulation results associated with the battery pack are presented. Namely, in

Figure 8a, the evolution of the battery voltage throughout the FTP75 cycle is plotted against the corresponding results from MATLAB. As can be seen, the voltage curve consistently follows the trend of the transient response that is incorporated in MATLAB simulations. The maximum value of the relative deviation equals 1.49% during steep changes in desired velocity. In

Figure 8b, by convention, the current is positive when injected into the battery and negative when supplied by the battery. Multiple spikes denote that current changes sharply to succeed fast changes in velocity rate of change, i.e. vehicle acceleration. A slight difference that is observed in the amplitude of a few instantaneous current spikes can be associated with a similar deviation of the torque requested by the driver control subsystem that is described in the related figure. This amplitude deviation is carried to the SoC graph in

Figure 8c, where the maximum deviation is limited to 0.08%. SoC is exported after the integration of current timeseries, therefore the final divergence of the two curves can be explained by the accumulation of instantaneous deviations of current curves. In

Figure 8d the evolution of the power injected into the battery is plotted and is also in line with MATLAB results, which is expected from the aforementioned similarity of current and voltage curves. These results allow the conclusion that accurate estimations of power transactions throughout the EV powertrain take place.

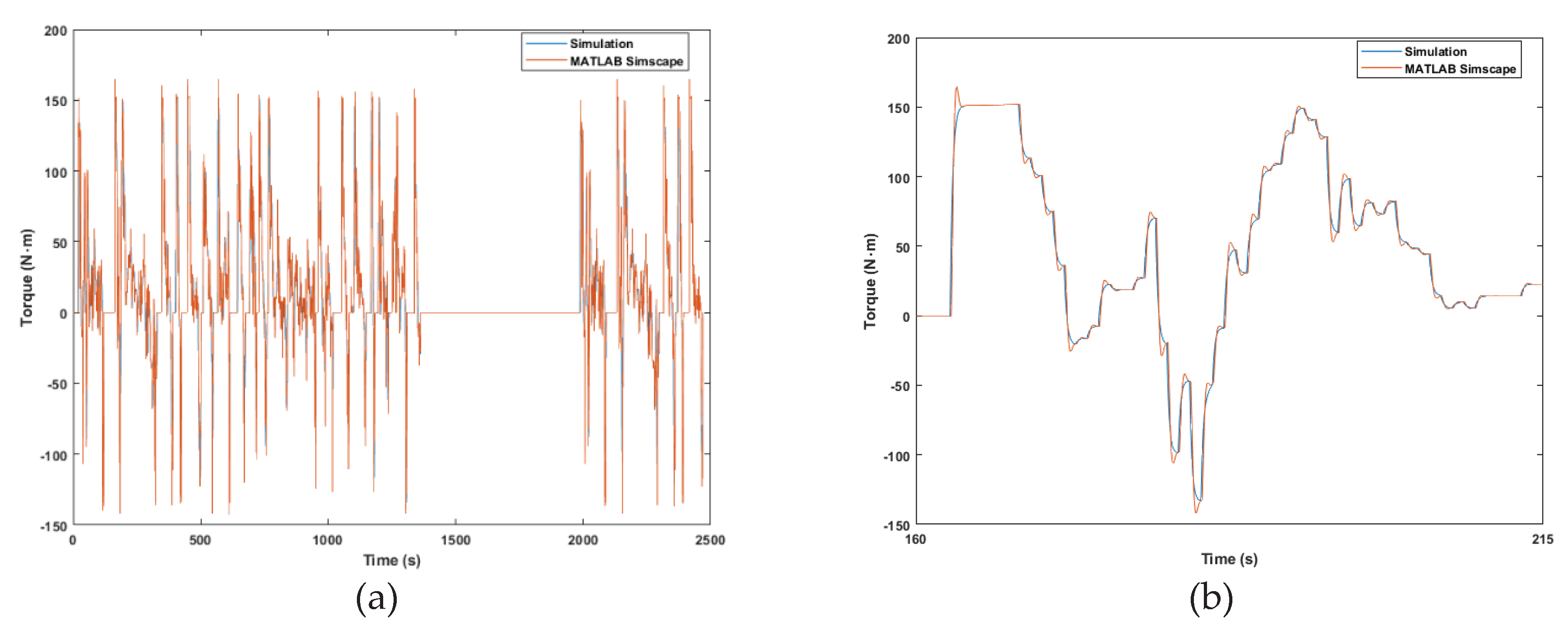

Next, the focus is given to the simulation results of the motor subsystem. In

Figure 9, the results of the torque applied by the motor show an accurate match of the solutions of the two software. The evolution of torque throughout the entire cycle is depicted in

Figure 9a whereas a more detailed view, between 160s and 215s, is shown in

Figure 9b to highlight the nature of the instantaneous divergence of the applied torque. Divergence is connected with the requested control command. Model control achieves a more smooth response of the requested torque command in comparison with MATLAB. This fact is only related to the selection of PI controller constants of the driver subsystem in MATLAB and does not imply any model malfunction. Nevertheless, the overshoot that is avoided in the simulations of the developed model can provide an explanation for the mismatch between the amplitude of torque instantaneous spikes, and as a consequence the corresponding mismatch of current values referred to in

Figure 8b. Overall, curves of the torque applied by the motor present a significant similarity throughout the FTP75 cycle.

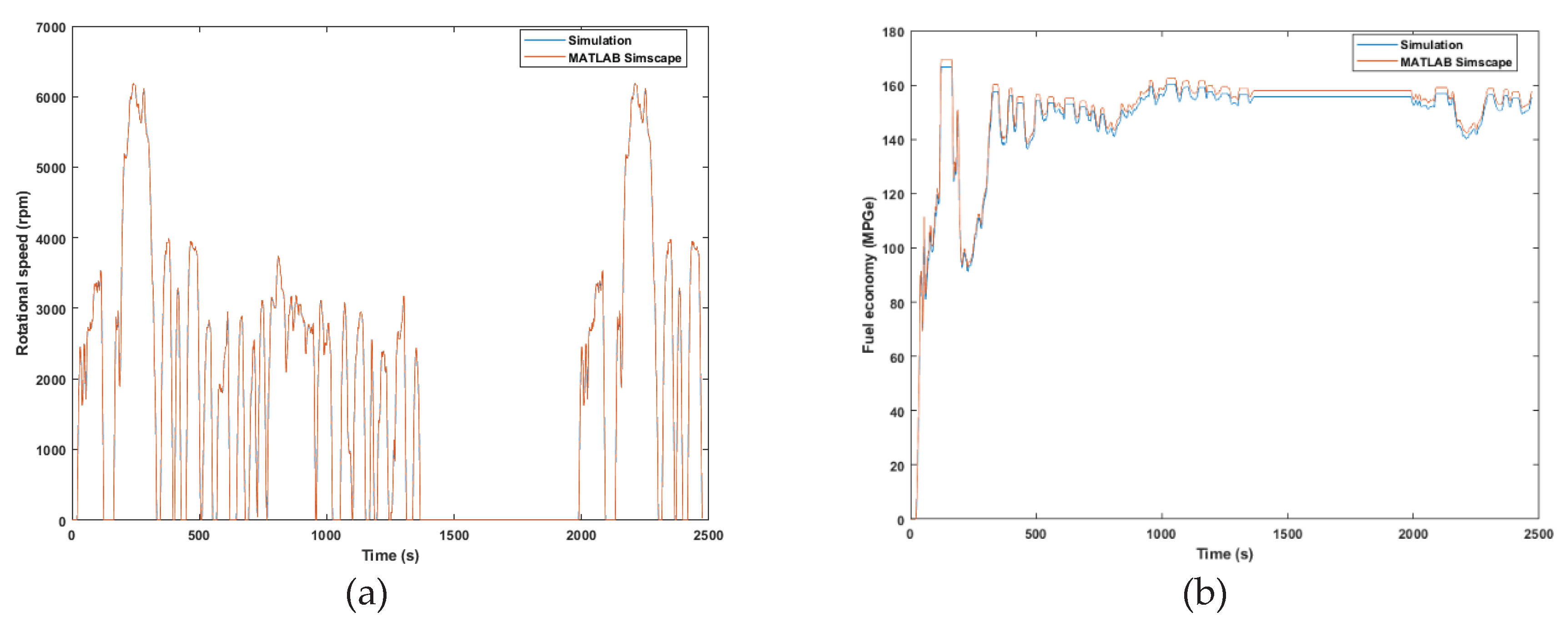

The similarity in the motor rotational speed results, shown in

Figure 10a, is anticipated based on the results presented up to this point. To measure the fuel economy, the evolution of the MPG

ge index, introduced by the US Environmental Protection Agency in 2010 [

19], is monitored and compared with MATLAB results in

Figure 10b. A slight divergence is carried throughout the simulation, leading to a final difference of 2.27 MPGe or a relative difference of 1.43%. This index evolves cumulatively in time so, in the same way, that is explained for SoC quantity, instantaneous value deviations during peak currents lead to the carried-out divergence until the end of the cycle.

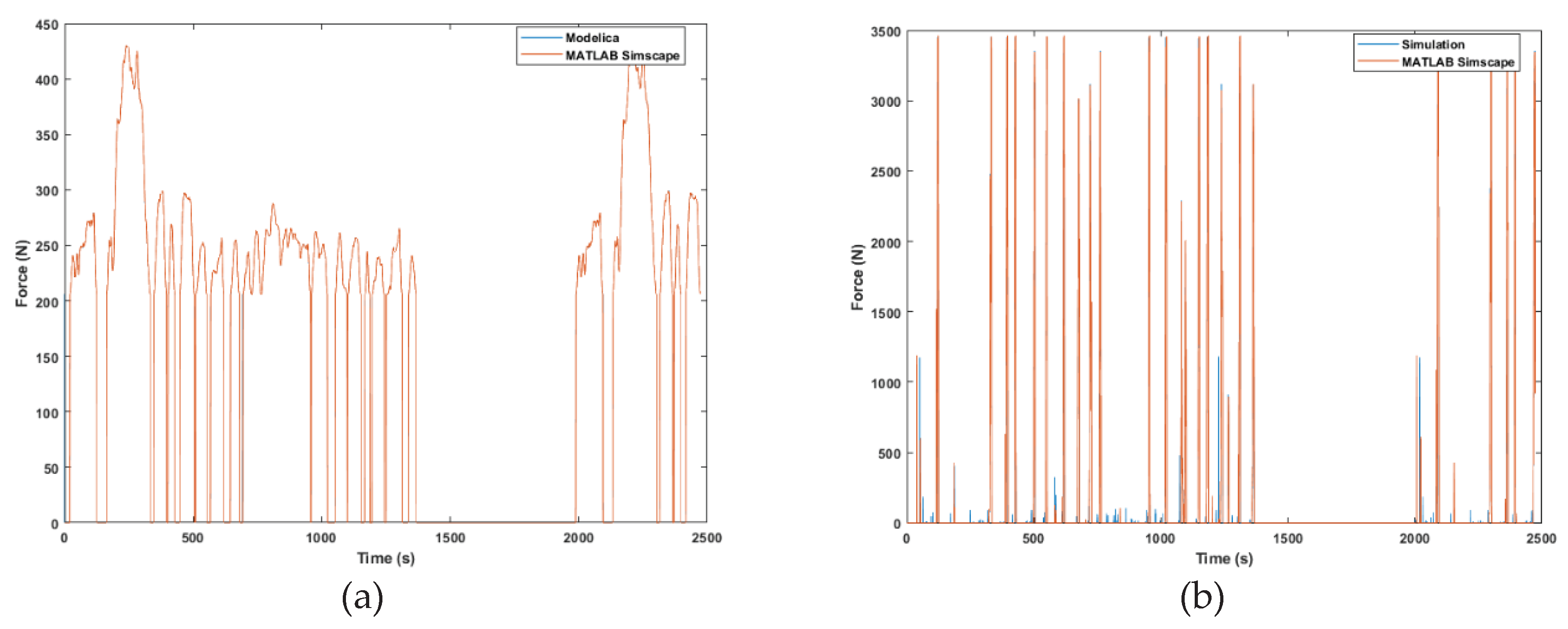

Examining the evolution of the quantities monitored in

Figure 11 is also necessary to verify the simplifications made in the coupling of the drivetrain components and the vehicle kinetics. Results show that the estimations of the applied forces of aerodynamic drag and rolling resistance are in agreement with the ones exported from MATLAB. The quantity of total EV brake force is generally close to the MATLAB curve, except for certain instantaneous deviations that can also be explained by the aforementioned peak torque mismatches.

Regarding the performance of the Modelica-developed model, the EV application under study can be simulated for 10 repetitions of the FTP75 cycle in 25 seconds. The corresponding battery's actual operation time is 6.87 hours. This time-efficient feature is convenient for model-based optimization, given that the system model can be exported in a Functional Mockup Unit (FMU) and be coupled with software compatible with Functional Mock-up Interface (FMI) standard.

5. Conclusions

This study focuses on the development of dynamic battery models for EV applications. The models have been developed using the second-order ECM technique with Modelica language for 4 different types of Li-ion cell chemistry that are commonly found in commercial EVs. Recently published parameter datasets of the 4 Li-ion battery cells [

14] are retrieved and used for the simulations.

An EV powertrain system model is built to perform model verification against a well-established reference application designed with MATLAB Simulink/Simscape. All required subsystems for an accurate representation of the overall EV system have been developed with Modelica. Moreover, a simplified version of the drivetrain subsystem model is designed with Simscape, ensuring the alignment with the developed drivetrain model. The simplified drivetrain models reduce the dependence of the verification process on the precise representation of mechanical system interactions.

Simulation results point out that the integrated system operation ensures the desired velocity profile is followed satisfactorily. The maximum vehicle velocity deviation is 1.22 km/h which can be considered acceptable given the time required by the controller emulating the driver to respond. The evolution of battery pack quantities also illustrates an accurate match between the model and MATLAB results. Namely, the relative deviation of simulated voltage reaches its maximum value of 1.49% during increased values of acceleration or deceleration, the SoC cumulative divergence at the end of the cycle equals 0.08%, whereas the strong similarity in both current and power curves strengthens estimation accuracy. Results associated with motor performance and vehicle kinetics also agree with the ones exported from the MATLAB reference application, whereas instantaneous deviations in the requested torque that affect the estimation of cumulative quantities (SoC, fuel economy) are associated with slight differences in the driver’s control approach.

The overall correspondence of the results with the ones from MATLAB can ease drawing the conclusion that the representation of an EV system can be achieved accurately and reliably using the developed models. Moreover, the inclusion of 4 battery cell parameter datasets enables the virtual representation of a wide range of commercial EVs. The system model can be exported in an FMU and used in software that support the FMI standard.

Moreover, the exploration and early assessment of multiple approaches to battery integration into broader EV powertrain architectures is made possible and could be the subject of study in future work. Furthermore, incorporating a more detailed and sophisticated motor model could help extract useful conclusions regarding motor performance within the powertrain. On top of the above, including hardware-in-the-loop equipment could lead to fine-tuning the system control modules. Evaluating different BMS strategies for battery optimal operation within the powertrain, e.g. developing cell balancing algorithms, is also enabled. Finally, a possible next step after the verification process against reliable MATLAB results would be to validate the models with experimental measurements from the battery pack and the powertrain.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.R., P.I., N.N., D.R. and A.T.; methodology, R.R.; software, R.R.; validation, R.R.; investigation, R.R.; writing—original draft preparation, R.R., P.I., N.N., D.R. and A.T.; writing—review and editing, R.R., P.I., N.N., D.R. and A.T.; visualization, R.R.; supervision, N.N. and A.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research has been carried out in the framework of the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation programme under grant agreement 101056874 (SCALE - Smart Charging ALignment for Europe).

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Qin, D.; Li, J.; Wang, T.; Zhang, D. Modeling and Simulating a Battery for an Electric Vehicle Based on Modelica. Automot. Innov. 2019, 2, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritzson, P. Principles of Object-Oriented Modeling and Simulation with Modelica 3.3: A Cyber-Physical Approach; 2. ed.; IEEE Press [u.a.]: Piscataway, NJ, 2015; ISBN 978-1-118-85912-4.

- Doyle, M.; Newman, J.; Gozdz, A.S.; Schmutz, C.N.; Tarascon, J. Comparison of Modeling Predictions with Experimental Data from Plastic Lithium Ion Cells. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1996, 143, 1890–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamilselvi, S.; Gunasundari, S.; Karuppiah, N.; Razak RK, A.; Madhusudan, S.; Nagarajan, V.M.; Sathish, T.; Shamim, M.Z.M.; Saleel, C.A.; Afzal, A. A Review on Battery Modelling Techniques. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Rincon-Mora, G.A. Accurate Electrical Battery Model Capable of Predicting Runtime and I-V Performance. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2006, 21, 504–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huria, T.; Ceraolo, M.; Gazzarri, J.; Jackey, R. High Fidelity Electrical Model with Thermal Dependence for Characterization and Simulation of High Power Lithium Battery Cells. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE International Electric Vehicle Conference; IEEE: Greenville, SC, March, 2012; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Milishchuk, R.; Bogodorova, T. Thevenin-Based Battery Model with Ageing Effects in Modelica. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 21st Mediterranean Electrotechnical Conference (MELECON); IEEE: Palermo, Italy, June 14, 2022; pp. 243–248. [Google Scholar]

- Bairwa, B.; B, S.; Pratiksha, C.; A, S. Modeling and Simulation of Electric Vehicle Powertrain for Dynamic Performance Evaluation. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Distributed Computing and Electrical Circuits and Electronics (ICDCECE); IEEE: Ballar, India, April 29, 2023; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Chandra, S.; Nair, A.C.; Yadav, A.K.; Singhal, S. An Integrated Approach for Modelling Electric Powertrain. In Proceedings of the 2023 5th Global Power, Energy and Communication Conference (GPECOM); IEEE: Nevsehir, Turkiye, June 14 2023; pp. 175–180.

- Meszaros, S.; Bashash, S. Optimal Electric Vehicle Braking Control for Maximum Energy Regeneration. In Proceedings of the 2023 American Control Conference (ACC); IEEE: San Diego, CA, USA, May 31 2023; pp. 2475–2480.

- Adegbohun, F.; Von Jouanne, A.; Phillips, B.; Agamloh, E.; Yokochi, A. High Performance Electric Vehicle Powertrain Modeling, Simulation and Validation. Energies 2021, 14, 1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerl, J.; Janczyk, L.; Krüger, I.; Modrow, N. A Modelica Based Lithium Ion Battery Model.; March 10 2014; pp. 335–341.

- Rotas, R.; Iliadis, P.; Nikolopoulos, N.; Tomboulides, A.; Kosmatopoulos, E. Dynamic Simulation and Performance Enhancement Analysis of a Renewable Driven Trigeneration System. Energies 2022, 15, 3688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, M.-K.; DaCosta, A.; Mevawalla, A.; Panchal, S.; Fowler, M. Comparative Study of Equivalent Circuit Models Performance in Four Common Lithium-Ion Batteries: LFP, NMC, LMO, NCA. Batteries 2021, 7, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EV Reference Application - MATLAB & Simulink. Available online: https://www.mathworks.com/help/autoblks/ug/electric-vehicle-reference-application.html (accessed on 24 January 2024).

- Modelica/ModelicaStandardLibrary. Available online: https://github.com/modelica/ModelicaStandardLibrary (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- Ceraolo, M. Max-Privato/EHPT. Available online: https://github.com/max-privato/EHPT (accessed on 24 January 2024).

- US EPA, O. EPA Federal Test Procedure (FTP). Available online: https://www.epa.gov/emission-standards-reference-guide/epa-federal-test-procedure-ftp (accessed on 24 January 2024).

- US EPA, O. Text Version of the Electric Vehicle Label. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/fueleconomy/text-version-electric-vehicle-label (accessed on 26 January 2024).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).