2. Naval Combat and Maritime Strategy

In the turbulent seas of the medieval period, merchant ships were not merely vessels of trade but pivotal components in naval warfare, especially when specialized warships were in short supply. In the kingdom of Castile, for instance, the naval arsenal was limited, with only a handful of warships dedicated to safeguarding the strategic Strait of Gibraltar against incursions from the Muslim kingdom of Granada and the Berber states. Consequently, during times of conflict, reliance on commercial and fishing vessels became a necessity. These ships were hastily equipped and armed for battle, transforming them into improvised menofwar. Beyond the official royal navy, which was under the direct command of captains appointed by the monarchy, private fleets and occasionally individual ships also engaged in maritime skirmishes. These privateers operated under royal sanction, granted through letters of marque and reprisal, which authorized them to disrupt the economic stability of adversaries by targeting their merchant ships. The goal was not to engage enemy warships in direct combat but to capture or destroy the commercial vessels, seizing both the ships and their cargoes as war prizes. These spoils remained with the victors, although at times a portion was remitted to the crown as fiscal dues. The oversight of these privateering activities by the rulers was often lax, leading to instances where the privateers exceeded their mandates. In their zeal, they sometimes violated treaties and attacked neutral ships, harming individuals as well as property, blurring the lines between sanctioned acts of war and outright piracy. Such actions, while intended to serve the interests of the state, frequently strayed into lawlessness, reflecting the chaotic and unregulated nature of maritime conflict during the era. The distinction between privateering and piracy was, therefore, a fine one, often defined more by the presence of a royal license than by the conduct of the mariners themselves (Jasper, 2008; Suárez, 1950).

The activities undertaken by Biscayan ships, which included both formal military engagements and privateering, particularly those initiated by the inhabitants of Bilbao, against French interests, present a complex historical tapestry that is often challenging to unravel. These maritime endeavors, rooted in the sociopolitical dynamics of the time, reflect a nuanced interplay of regional power struggles, economic ambitions, and the broader geopolitical landscape of the era. The distinction between statesanctioned naval operations and privately sponsored maritime raids is frequently blurred, making it difficult to categorize the actions definitively. This ambiguity is further compounded by the sporadic nature of historical records, which can obscure the full extent and motivations behind these confrontations. As such, a comprehensive understanding of the Biscayan maritime practices against France requires meticulous examination of the available historical evidence, a task that demands both scholarly rigor and a discerning eye for the subtleties of historical context. (Eddison, 2018; Dirk, 2009). In the year 1500, a formidable fleet was assembled, with the town of Portugalete supplying the necessary armed forces for embarkation. Meanwhile, in 1503, Bilbao played a significant role by equipping four ships for service in the conflict against France. As a result of this war, the ruling monarchs issued an edict for the expulsion of all French nationals under penalty of death, with exceptions made only for longterm residents in Castilian territories, such as Juan de León in Durango, and in Bilbao, inhabitants as Juan de Francia, Pierres Morroson, Juan Luxuer, Juan Mixaot, Juan Galarte Bonet, Guillemalo Mirez, Juan de Bayona, Pedro de los Ríos Bonet, and Juan Rey. In the same year, the destruction wrought by marauding French caravels along the Galician shores necessitated the deployment of a caravel from Pedro González de Galaza of Portugalete, accompanied by three other armed ships and a crew of 330 men, to thwart these incursions. Upon their arrival in La Corunna, these ships were outfitted with all essential supplies and equipment by the governor of the Kingdom of Galicia, including a twomonth provision of bread, calculated at one bushel per man per month (Archivo General de Simancas [hereafter: AGS], Registro General del Sello [Hereafter: RGS], 149409, 138; 149607, 84, 124. AGS, Patronato Real [hereafter: PTR], legajo 52, documents 49, 51, 54; AGS, Cámara Castilla [hereafter: CC], Cédulas [hereafter: CED] 6, 70, 2; 9, 115, 3). Throughout history, the establishment of naval fleets has been a pivotal aspect of a nation's assertion of power and protection of its interests. The fleets commissioned by the Crown were no exception, embodying a range of purposes from defense to diplomacy. Notably, in 1491, the Royal Council of Castile recognized the need to secure commercial routes in the Bay of Biscay, a crucial maritime zone plagued by threats that jeopardized trade. In response, they contemplated the creation of an armed fleet dedicated to safeguarding Castilian merchant ships. This initiative was to be financed by a levy imposed on the very vessels it aimed to protect, with the amount determined by the value of the cargo they transported. Such a measure was not only strategic but also reflected the collective responsibility of the beneficiaries to contribute to their own defense. This early form of maritime security underscores the complexities of trade, governance, and military logistics of the end of the Middle Ages, revealing the intricate balance between the needs of the state and the welfare of its merchants. The proposal by the Royal Council was a forwardthinking resolution to a persistent issue, highlighting the evolving nature of naval defense and the proactive steps taken to ensure the uninterrupted flow of commerce, which was the lifeblood of the nation's economy. The consideration of such a fleet marked a significant moment in maritime history, laying the groundwork for future naval strategies and the concept of mutualized defense costs, which would become a cornerstone of collective security in maritime law. This historical account serves as a testament to the ingenuity and adaptability of past governance in the face of emerging challenges in maritime trade (Enríquez, 1999, 2000, 2002a, 2002b, 2002c; García Arancón, 1985; Hidalgo, 1987).

In the late 15th century, the maritime practices of the Spanish monarchy often involved the conscription of civilian vessels into royal fleets. These fleets, assembled for various purposes such as combat or exploration, sometimes incorporated ships through voluntary service, incentivized by payment. However, there were instances where ships were commandeered against their will, disrupting commercial activities and trade routes. Notably, in 1476, King Fernando issued letters of safeguard to the shipmasters of Bilbao, ensuring their participation in a naval force being organized to confront the French. These letters assured that once the ships were unloaded and refitted for military use, they would be given priority in future commercial engagements postconflict, mitigating the potential loss of trade. Furthermore, the king extended an invitation to any vessel from Biscay to join the royal navy.

By 1487, the crown had raised another fleet, prompting a directive that barred shipmasters and captains of vessels from Biscay and Guipúzcoa, particularly those commanding ships and caravels over 30 tuns, from departing port without explicit permission. They were ordered to remain available for royal service. This mandate led to significant contention, especially from the University of merchants of Burgos, who argued that the policy effectively halted all maritime activity along the coast, affecting both laden and unladen ships. The situation was exacerbated when several ships, ready to embark for destinations like Flanders, England, Rouen, and La Rochelle with cargoes of iron and wool, were detained in Bilbao and Laredo. The prolonged detainment threatened the viability of the wool, risking its spoilage.

Amid these tensions, a vessel owned by an individual named Barraondo, laden with cloth and bound for Bilbao, sought refuge in Guetaria due to adverse weather conditions. There, it was seized under the royal embargo. Determined to reach Bilbao and offload the cargo, the ship's captain attempted to leave Guetaria but was pursued and captured by two armed pinnaces, forcing a return to the port. This incident prompted the University of merchants to appeal to the monarchs for the release of this ship and nine others, a request that was eventually granted. However, the practice of arresting ships for royal service resurfaced in 1495 with the assembly of another fleet, only to be lifted once the fleet set sail. This historical account highlights the complex interplay between royal authority and merchant interests during a period marked by naval expansion and economic ambition. In the year 1519, King Carlos I of Spain commissioned the assembly of an additional naval force, a move that had significant implications for the wool trade. Concurrently, a fleet prepared to embark from the port of Portugalete, destined for Flanders, found itself unexpectedly detained. The ships, laden with valuable wool, were barred from setting sail and mandated to remain in port. This directive was not without consequence; it necessitated a period of waiting, during which the vessels and their cargoes were held in abeyance, pending further orders. This incident underscores the intricate interplay between maritime endeavors and the economic currents of the time, reflecting the extent to which political decisions could abruptly alter the course of commerce and trade routes during the early 16th century (Enríquez, 1999, 2001, 2008; Recalde, 1988; Labayru, 1895).

In 1481, the authority of Guipúzcoa was asked to supply ships for a naval force, but instead, the monarchs levied a tax of 1.2 million maravedis. The inhabitants of Guipúzcoa resisted this tax, leading to enforced collection by the chief royal accountant. However, by 1484, after contributing three ships to the crown's military efforts in the Granada War, Guipúzcoa was forgiven its previous debt. Despite its initial reluctance to join the royal navy, Guipúzcoa was quick to mobilize its own fleet when its interests were threatened. This was evident in 1487 when, claiming they had been attacked by French and Breton ships, they armed several caravels to capture any encountered vessels. This aggressive defense strategy prompted the University of merchants of Burgos to intervene, fearing the repercussions of such actions. They demanded that fleets not be raised without sureties from the arming towns to ensure the safety of their commercial allies. The situation escalated when Rentería's inhabitants captured two French ships, risking retaliation against their own vessels and goods. The Castilian monarchs eventually agreed to the merchants' requests. In 1498, with French armed ships in the English Channel, Guipúzcoa's Board of procurators sought a royal license to form a defensive navy, which was granted on the condition that, as before, sureties were provided to protect Castilian and allied interests from harm (Recalde, 1988).

The increasingly frequent international conflicts of the fifteenth century posed significant obstacles to maritime trade. Merchants from warring nations faced not only the threat of assault, robbery, and capture but also the risk of imprisonment or execution in enemy lands. Moreover, engaging in commerce or providing services—be it maritime, financial, diplomatic, or as intermediaries—could lead to accusations of treason by their own governments. Consequently, the Castilian monarchs often prohibited their subjects from conducting any form of business, including trade, with adversary states during periods of conflict.

During the tumultuous period of the Castilian succession crisis, Portugal sided with Juana, the daughter of Enrique IV, against her aunt, Queen Isabel. This conflict led the Catholic Monarchs to prohibit their subjects from engaging in trade with the neighboring kingdom. In response to this ban, in 1478, Martín Ochoa de Sasiola and the pilot Miguel de Barrasueta were granted authorization to partake in privateering. They were given the right to use their caravels, shipping companies, and armed forces to navigate to Portuguese waters with the intent of capturing any Castilian ships they encountered, especially those carrying horses, iron, steel, and provisions. The goal of these actions was to inflict maximum damage on the Portuguese king and his subjects. As a reward for their efforts, they were permitted to claim any seized goods as their own. However, they were expressly forbidden from capturing any merchants or goods that were protected by a royal license for trade with Portugal. This historical episode reflects the complex interplay of politics, economics, and warfare during a pivotal moment in Iberian history (SolórzanoTelechea, 2023; Recalde, 1988).

In the year 1478, a significant commercial license was issued under the protection of the Catholic Monarchs. This particular license was awarded to Juan de Mele, a native of SaintPoldeLéon in Brittany. Mele's vessel was laden with an array of goods, including textiles such as cloth and canvas, as well as brass candleholders, various pieces of artillery, and an assortment of other valuable items. The total cargo carried by his ship was estimated to be worth around 2,000 gold crowns, a considerable sum for that period. This transaction not only highlights the vibrant trade that existed during the time but also underscores the importance of maritime commerce in the expansion of economic frontiers. The granting of such a license to a foreign merchant like Mele reflects the interconnected nature of European trade networks and the role of the Catholic Monarchs in fostering economic growth and crosscultural exchanges during the late Middle Ages (AGS, RGS, leg. 147811, 52).

In the late 15th century, maritime piracy was a significant threat to merchants and seafarers. One such incident involved a vessel that was overtaken and plundered near the Portuguese coast by two ships commanded by Pedro de Bilbao, a notorious pirate from Portugalete. After his raid, Bilbao sought refuge in Puerto de Santa María. The reigning monarchs, upon hearing of this lawlessness, decreed that Bilbao must return the stolen merchandise. Defiantly, Bilbao attempted to negotiate a ransom for the goods, but the sovereigns reiterated their command, insisting on the restitution of the goods without any form of compensation. In an ironic twist of fate, Pedro de Bilbao himself fell victim to piracy when, on October 25, 1493, while navigating from Faro to Flanders, his ship, laden with valuable cargo, was captured by the Portuguese. The ship, its contents, and the freight, valued at 3,000 ducats, were all confiscated, turning the predator into prey in the perilous waters of the Age of Discovery. This historical account not only highlights the risks of maritime trade during this era but also reflects the complex interplay of power, law, and morality on the high seas (González Arce, 2021). The Catholic Monarchs, in a display of diplomatic foresight, sought safeguarding for him from the Portuguese monarch, honoring the treaties established between the two sovereignties. This strategic move underscored the intricate web of alliances that shaped European politics, where royal decrees and agreements were pivotal in securing the safety and support of individuals across borders. Such actions were emblematic of the era's complex interkingdom relations, where protection and patronage were often exchanged in the pursuit of greater geopolitical stability and mutual benefit.

In the turbulent aftermath of armed skirmishes, the year 1476 witnessed the Catholic Monarchs bestowing clemency upon Rodrigo de Fagaza, a Bilbao merchant and captain of the Santo Espíritu, which had docked in Flanders the preceding year. This pardon came as a result of the Santo Espíritu's sustained damages, compelling Fagaza to chart a course for Andalusia. Tragically, during this journey, he endured the loss of his pilot, necessitating the hiring of a foreign replacement. The ship's deteriorated state, coupled with adverse meteorological conditions, forced him to seek refuge in Cascais, where he solicited a safeconduct from the Portuguese authorities, as Portugal was then embroiled in conflict with Castile. The Portuguese acquiesced, stipulating that Fagaza must pledge to undertake a return cargo trip from Flanders, laden with wine, oil, and assorted goods. Fagaza, constrained by circumstance, consented to the terms but staunchly declined any further commerce with Portugal, despite lucrative offers, to avoid contravening the edicts of Castilian royalty. Resuming his voyage to Bilbao, Fagaza commandeered a Portuguese caravel en route, repurposing it for the Castilian crown's military campaigns against the French and Portuguese. The royal pardon granted to Fagaza shielded him from arrest or incarceration for his breach of the embargo on trade with Portugal, whether by kingdom officials or licensed privateers (Enríquez, 2002b).

The clemency extended by the sovereigns was solely in recognition of services rendered with excessive zeal, rather than for any breach of their directives. This act of mercy underscores the distinction between enthusiasm in duty and disobedience of command, acknowledging the former while maintaining the sanctity of the latter. It serves as a nuanced acknowledgment that while fervor in one's service is commendable; it must be balanced with adherence to the established mandates of authority. Such pardons are a testament to the monarchs' understanding of human nature, allowing for a measure of grace in the face of overeagerness, yet drawing a clear line when it comes to the outright defiance of their edicts. This delicate balance between leniency and discipline reflects the intricate dance of governance, where the rulers must weigh the intentions behind actions against the outcomes they yield (González Arce, 2021). In 1477, Juan Ochoa of Bilbao, serving as a royal official, embarked on a mission sanctioned by the monarchs to disrupt French and Portuguese maritime interests, as well as those of the Moors. Accompanying him were his brother Pedro de Elguera, his cousin Juan de Rabanza, who captained the ship used in their privateering endeavors, and several others including Pedro and Sancho de Vañales, Juan de Sangronis, and Ochoa de Elguera. Their campaign was marked by the capture of ships and merchandise, and confrontations that resulted in injuries and fatalities. Concurrently, England had commandeered numerous vessels, appropriating them along with their cargoes for the crown. This series of events instilled a fear among the privateers of potential legal repercussions and personal vendettas. In response, they sought clemency from the sovereigns, who, acknowledging the privateers' past services and anticipating future contributions, granted a royal pardon. This act of mercy, issued by the monarchs' own volition and the full extent of their authority, provided the privateers and their possessions with protection under the crown, absolving them of any dishonor or infamy incurred by their actions, whether in fact or by law. Nevertheless, this pardon explicitly excluded crimes such as betrayal, treason, murder, or the illicit export of precious metals from the realm. A parallel instance occurred that year when Pero Ruiz de Munchaca and Diego López de Aresmendi received a similar pardon for their unpaid service in the royal navy against Portugal (Enríquez, 2002a).

The cessation of hostilities with Portugal in 1479 marked a pivotal moment in history, yet the ink on the peace treaty had scarcely dried when certain shipmasters, previously sanctioned to raid as privateers, chose to disregard the newfound peace. Among them was Juan Íñiguez de Bermeo, a notable figure from Bilbao, who, through his agent Pedro Ortiz de Bolívar, commandeered a caravel brimming with valuable commodities such as wax, honey, oil, and orcein. This vessel, owned by Portuguese nationals Martín Alonso and Juan Yáñez of Porto, was captured in the waters near SaintNazaire. Despite the peace treaty's explicit terms, the seizure was justified under the guise of the surety it provided, revealing the complexities and challenges of enforcing peace in an era where maritime law was as turbulent as the seas themselves. This incident underscores the intricate web of loyalty, economics, and power that defined the end of the Middle Ages, a time when the allure of wealth often eclipsed the call for diplomacy and peace (González Arce, 2021).

In the bustling port of Laredo in Castile, a dispute arose that would assess the authority of local and royal jurisdictions. Portuguese sailors, aggrieved by the actions of a Bilbao shipmaster, sought justice for the unauthorized appropriation of their caravel. The justice of Laredo, upholding the law of the land, decreed that the vessel be returned or placed under local authority—a mandate the shipmaster brazenly defied, fleeing to Bilbao. In Bilbao, the corregidor, an official appointed by Queen Isabel I, seized the caravel, although much of its cargo was already sold or damaged. This act of defiance spurred the Portuguese to seek compensation from the highest authority, appealing to the Catholic Monarchs for redress amounting to 2,000 doblas de la banda.

The monarchs, recognizing the gravity of the situation, agreed to the Portuguese demands, ordering the seizure of assets from the offenders or their guarantors. Yet, the execution of this order stalled in 1480, as the Castilians argued that the peace treaty, though signed at the time of the seizure, had not been officially proclaimed. The impasse deepened, prompting the monarchs to instruct Biscayan justices to enforce the return of the seized goods and ensure the Portuguese were compensated for their losses and damages. They underscored the urgency with a stern warning: failure to comply would result in the funds being extracted directly from the county of Biscay or its citizens.

Amidst these tensions, Ortiz Bolívar, implicated in the seizure, sought to limit his liability to only his share of the responsibility. The monarchs, in their quest for equitable resolution, ordered a San Sebastian townsman, also involved, to do likewise. This historical episode illustrates the complexities of maritime law, the reach of royal authority, and the intricate dance of justice and diplomacy in the late 15th century. It is a narrative that echoes the challenges of governance, the pursuit of justice, and the delicate balance of power between local and central authorities. Subsequently, Juan Íñiguez, having petitioned the sovereigns, ensured that his crew aboard the caravel under Bolívar's command, with Guillaume, the Briton, as pilot, along with numerous other sailors, were obliged to return a portion of the bounty they had received. This measure was to prevent Íñiguez, as the shipowner, from shouldering the entire cost. The financial responsibility for their share of the bounty was thus distributed among the crew members, save for the three officers previously mentioned, who were to assume full responsibility. The complexity of the case escalated to the point where the monarchs delegated the matter to the corregidor of Biscay. The provost of Bilbao’s decision necessitated this action to release Íñiguez from incarceration without seizing his assets, a move that Íñiguez exploited by seeking support from the county to oppose what he claimed were oppressive royal decrees. He went so far as to threaten harm to the Portuguese if they continued to insist on his imprisonment and asset seizure. The corregidor, bound by duty, was compelled to fulfill the royal command, resulting in the detention of Íñiguez and his crew. To compensate the Portuguese, the corregidor was instructed to reference the letters of averages provided by the ship and the notarial document that detailed the agreedupon division of spoils among the attackers. (Enríquez, 2002b, 2002c; Torre del Cerro & Suárez, 1963.

Privateering attacks during the 15th century were a significant aspect of maritime conflict, affecting not only the nationals of enemy states but also merchants from allied and neutral territories. This was exemplified by the Bretons, whose relations with the French crown were contentious at the time. In 1458, the Bilbao town council imposed an embargo on the merchandise of Saint Malo merchants, amounting to 8,000 maravedíes, as a punitive measure. This action was in response to the privateering activities of Saint Malo citizens, who had appropriated goods and wines from Bilbao merchants. In an attempt to resolve the situation, a Saint Malo merchant, representing others, journeyed to Bilbao to negotiate the release of five sacks of wool that had been seized. The Bilbao authorities consented to return the confiscated goods once the Saint Malo merchants compensated for the theft with 8,000 maravedíes. This incident highlights the complex interplay of commerce, conflict, and diplomacy in a period where maritime law was still in its infancy and privateering was a widespread practice used to exert economic pressure and retaliate against perceived injustices. It also underscores the intricate relationships between different maritime communities, where alliances could be both fluid and fraught with tension. The resolution of this dispute reflects the pragmatic approach often adopted by merchant communities to safeguard their economic interests, even in the face of broader political hostilities. The willingness to negotiate and settle disputes through compensation, rather than escalating conflict, indicates a sophisticated understanding of the importance of maintaining trade relationships, even among adversaries. This historical account provides a window into the challenges faced by merchants and authorities in navigating the treacherous waters of 15thcentury trade and diplomacy (Enríquez, 1995).

In the year 1483, the Breton people endured further assaults, this time at the hands of Captain Martín de Zarauz, a native of Zumaya. Commandeering his armed ship was Ochoa de Asúa, hailing from the Asúa region near the Nervión estuary. Together, they launched an attack on Artur de Lili and his ship as it navigated off the Saltes coast, carrying goods valued at 6,000 gold doblas destined for Jerez. This incident highlights the perilous nature of maritime trade during that era, where piracy and privateering were common threats to merchants and seafarers alike. The value of the cargo indicates the significance of the merchandise being transported, reflecting the economic vitality and the wealth that was at stake in these maritime ventures. Such events were not isolated incidents but part of a larger tapestry of maritime conflict that characterized the late medieval period, underscoring the constant danger that loomed over those who sought to conduct trade across the treacherous waters of the time (González Arce, 2021). In the late 15th century, a violent skirmish resulted in the death of two men. The perpetrators, in defiance of existing treaties with the Duke of Brittany, plundered the weaponry, provisions, and other supplies from the ship. The Bretons, seeking justice for this blatant disregard for the accord, took their plea to the Castilian throne. The monarchs responded by instructing the admiral and captain of the nascent navy, then preparing to combat the Moslesm, to apprehend the culprits, present them to the judiciary, and confiscate their possessions. Concurrently, a Breton named Ivan Santibáñez, hailing from Colcarneo or Colcartebo, lodged a similar complaint. He recounted his ordeal of having been robbed by Bilbao locals—Juan Íñiguez de Gangure, Juan Ortiz de Guecho, among others—years prior, suffering financial losses amounting to 200 crowns and sustaining a nearly lethal arrow injury. The Castilian sovereigns delegated the resolution of this grievance to the corregidor of Biscay. However, the legal proceedings were still pending as the year 1484 dawned, leaving the matters unsettled and the quest for justice ongoing. This historical account underscores the complexities of maritime law and the challenges faced in enforcing justice across different authorities during a time when piracy and privateering were rampant on the high seas (Enríquez, 2002c, 2002d).

Following the conflicts with Portugal, France emerged as the principal adversary of the Catholic Monarchs in Europe, enduring through the latter part of their reign. This period was marked by recurrent maritime skirmishes, instigated not only by Castilians but also by the French, extending beyond declared wars. The year 1484 resonated with the aftershocks of the CastileFrance strife, particularly in regions where Biscayan citizens were sanctioned to engage in privateering against the ships and traders of France. This practice, while sanctioned, inadvertently inflicted harm upon their own maritime community. In the early months of 1484, an English trader named Juan Cot collaborated with Ochoa Martínez of Ondárroa to secure a cargo agreement in Portland's port with Juan Ibarra from Lequeitio, taking charge of a caravel laden with specific goods destined for Biscay. The Biscayan trader's cargo comprised distinct items including cloth, precious metals, and assorted merchandise collectively valued at 500 gold crowns; concurrently, the English merchant contributed a diverse assortment of goods such as vetch, beans, and textiles. This historical account underscores the intricate web of commerce and conflict during the reign of the Catholic Monarchs, reflecting the complexities of international relations and trade in the late 15th century (González Arce, 2021). En route along the coast of Brittany, they were intercepted by a French fleet commanded by Juan Breton, acting on behalf of the King of France. Breton captured Cot and his merchandise, sparing only the vetch and beans, likely due to the challenges of transferring such bulk from one ship to another. In the process, 140 gold crowns were seized from Martínez. Martínez protested, citing the prevailing peace, and understanding between France and Castile. The French captain conceded slightly, returning 20 crowns and instructing the Castilian to recoup the balance through the sale of the grain. He directed the shipmaster to sell the goods at the intended port and compensate Martínez with the proceeds. Yet, upon arrival in Lequeitio and after claiming his cargo, the captain reneged on this directive and failed to remit the funds due to Ochoa Martínez. Consequently, Ochoa Martínez sought redress from the Catholic Monarchs, who delegated the matter to the corregidor of Biscay with orders to resolve the dispute without recourse to a trial (Enríquez, 2002d).

Maritime conflicts between France and Castile escalated over two decades, culminating in a significant incident in 1491. Martín de Eguía, a Bilbao resident, found his vessel besieged while laden with textiles and goods owned by associates of the Burgos’ University of Merchants. Following the attack, the institution filed a formal grievance with the Catholic Monarchs. The ship, having departed from London, was commandeered by French forces to Honfleur, near Le Havre, and there, its cargo, property of Burgos' residents, was confiscated. Interestingly, items belonging to Bilbao's nationals and other Castilian regions were left untouched, suggesting possible collusion and deceit involving the ship's captain and pilot, who might have colluded with those spared from the robbery. Consequently, the University of Burgos petitioned the monarchs to seize the unstolen goods in Honfleur as potential compensation for its affiliates during the case's inquiry. The royal sovereigns entrusted the matter to the principal royal accountant, charging him with its resolution. In the ensuing months, Burgos merchants—Pedro de Arango, Diego de Soria, Andrés de la Cadena, Diego de Contreras, and Fernando Faece—approached the monarchs, alleging their London representatives had engaged Martín de Eguía's shipping services to transport textiles and other merchandise to Castile, valued at 15,000 gold crowns. In an unfortunate turn of maritime events, a vessel laden with goods was overtaken by French marauders. These opportunistic thieves, with the covert approval and active participation of the shipmaster, Eguía, laid claim to the cargo. Eguía, whose financial standing was in dire straits, found himself detained, unable to settle his debts. His freedom was contingent upon the provision of adequate sureties, a challenging feat given his lack of tangible assets in Bilbao or elsewhere. Contrary to the stipulated conditions, Eguía was inexplicably released without the required sureties, much to the chagrin of the Burgos merchants. These aggrieved traders vehemently protested, insisting on Eguía's recapture to account for the losses incurred. Their demands underscored the gravity of the breach of trust and sought to uphold the integrity of maritime commerce. This incident not only highlights the perils of seafaring trade but also the intricate web of trust that binds the commercial entities and individuals involved in such transactions. The merchants of Burgos, in their pursuit of justice, stood firm against the malpractices that threatened their livelihood, signaling a strong message to all parties engaged in the mercantile exchange. The case of Eguía serves as a cautionary tale, reminding us of the delicate balance between risk and regulation that navigates the uncertain waters of international trade (AGS, RGS 149109, 207; 149111, 111). During the late 15th and throughout the 16th century, a series of intermittent and persistent hostilities broke out between the Hispanic and French kingdoms. These conflicts manifested in various forms, from commercial warfare involving the assault and seizure of vessels, to the abduction of traders and their goods, reflecting the intense rivalry for maritime dominance. The strife extended to brutal and extensive military engagements, as well as specific, isolated events of significant impact. This period was marked by a volatile geopolitical landscape, where the quest for power, territorial expansion, and control over trade routes frequently led to clashes. The repercussions of these conflicts were farreaching, influencing the political, economic, and social spheres of the time. The era was characterized by a complex web of alliances and enmities, with the Hispanic and French crowns often at the center of the European power struggle. The maritime confrontations were particularly fierce, as control over the seas was crucial for the burgeoning colonial empires and their global trade networks. The kidnapping of merchants and commandeering of commodities were common tactics employed to disrupt the economic stability of the rival kingdom. Military confrontations, on the other hand, could escalate into fullscale wars, drawing in various European powers and sometimes spreading beyond the continent. These incidents, whether largescale wars or targeted attacks, had profound implications for the course of European history, shaping the destiny of nations and the lives of countless individuals. The period also saw the emergence of new military technologies and strategies, as the kingdoms sought to gain an upper hand in the conflicts. The continuous state of hostility fostered an environment of perpetual uncertainty and tension, which would eventually contribute to the reshaping of the European political landscape. The legacy of these hostilities is still evident in the historical narratives of the countries involved, and their study provides valuable insights into the complexities of international relations during the early modern period.

In the age of sail, piracy was not solely the domain of the lawless; it was often a pursuit undertaken by enterprising merchants. These individuals were not professional pirates in the traditional sense but were opportunistic in nature, seizing chances for profit on the high seas. Frequently, these same seafarers operated as privateers, wielding official licenses granted by sovereign states or regional authorities, blurring the lines between legitimate commerce and piracy. The distinction between privateering and piracy was nebulous, as actions under a letter of marque—a governmentissued commission authorizing private individuals to capture enemy vessels—could closely resemble those of pirates. Indeed, discerning whether these actors were engaged in statesanctioned privateering or unsanctioned piracy was often challenging. Regardless, privateering was at times a more lucrative venture than traditional merchant activities, offering substantial financial rewards for those willing to navigate its risks and moral ambiguities. This dual nature of seafaring commerce, where one could oscillate between merchant and pirate, privateer, and outlaw, reflects the complex maritime landscape of the time. It was a world where allegiance and legality were as fluid as the oceans, and where fortune favored the bold and the cunning (Liddy, 2005). As previously noted, the year 1487 marked a significant turn of events for the citizens of San Sebastián. In a bold display of maritime strategy, they assembled a formidable flotilla of caravels. This was not an act of aggression but a calculated response to the persistent and troubling robberies inflicted upon their ships and people by French marauders. The San Sebastián flotilla's mission was clear: to locate, board, and seize control of the French and Breton vessels responsible for these acts of piracy. This decisive action by the citizens was emblematic of their resilience and determination to protect their interests and assert their rights on the high seas. It reflected the turbulent times, where the law of the sea was enforced not just by nations, but also by the will of the people who braved its waters. The capture of these vessels served as a stark warning to those who would dare threaten the livelihood and safety of the people of San Sebastián. It underscored the community's capability to organize and execute a complex naval operation, demonstrating their navigational skills, tactical acumen, and unyielding spirit. This episode in history is a testament to the enduring human spirit in the face of adversity and the lengths to which individuals will go to defend their rights and secure justice (Rose, 2018). The members of the University of Burgos harbored reservations, apprehensive about the potential for equivalent retaliatory actions from France that might adversely affect their clientele and business associates in other nations, including the French. They were particularly concerned about the repercussions of assaults initiated by the natives of Guipúzcoa, which, due to their haphazard execution, could inadvertently harm Castilian goods being transported on French vessels. Consequently, they insisted on obtaining financial guarantees from the towns involved to compensate for any potential damages. In the wake of these events, in the year 1489, the Catholic Monarchs took more drastic measures in response to the escalating disorder in commercial and maritime activities, which was largely attributed to the rampant privateering and piracy conducted by their subjects, occasionally sanctioned by the Crown itself, along the Castilian shores (Fernández Duro, 1972). In the annals of maritime history, the fluctuating legality of privateering stands out as a testament to the complex interplay between national interests and international law. The year in question marked a significant shift in policy, as the ruling monarchy issued a royal decree that unequivocally prohibited all privateering pursuits, effectively invalidating any existing letters of marque. This sweeping edict reflected a momentary desire for peace and order on the high seas, a stark contrast to the rampant privateer activity that had characterized previous decades. Yet, the cessation of such practices was not to endure. In the face of unrelenting hostilities, particularly with the perennial adversary France, the crown found itself compelled to once again sanction privateering. By 1495, letters of marque were reissued, signaling a return to the statesponsored piracy that served as a strategic tool in the ongoing conflict. This ebb and flow of authorization not only highlights the volatile nature of wartime policy but also underscores the intricate balance of power that nations navigated during this tumultuous period. The regranting of these letters underscored the pragmatic approach of the monarchy, willing to adapt its stance on privateering in response to the shifting tides of war and diplomacy. It is a narrative thread that weaves through the fabric of naval warfare, reflecting the everchanging dynamics of geopolitical strategy and the lengths to which states would go to assert their dominance on the world stage.

In the wake of privateering's rampant growth, a more restrained approach emerged, allowing private entities to seek recompense for wartime losses from foreign nations or individuals through the issuance of letters of marque and reprisal. This shift was necessitated by the excesses and malpractices of privateering, compelling monarchs to introduce regulations to curb these nearly piratical acts of vengeance. They instituted permits or marques delineating the extent, duration, and terms under which fleets, or individual ships initially purposed for commerce, were converted into vessels of war under extraordinary circumstances. Originating in Castile, the letters of marque and reprisal authorized holders to recover losses incurred from being seized or plundered at sea by targeting ships from the same nation or city as the aggressors, extending even to allied domains. These documents served as a legal framework, sanctioning specific retaliatory actions against those responsible for maritime depredations, thereby providing a measure of justice and financial restoration for the aggrieved parties. The evolution from unrestrained privateering to the regulated issuance of letters of marque and reprisal represents a significant development in maritime law, reflecting the growing need for sovereign states to exert control over private warfare at sea. This transition also underscores the complexities of naval warfare and commerce during times of conflict, where the lines between economic pursuits and military engagements often blurred. The letters of marque and reprisal thus played a pivotal role in the history of naval warfare, balancing the scales between private interests and state sovereignty, and shaping the conduct of maritime conflicts for centuries to come.

3. City Alliances: Exploring Urban Diplomacy in Bilbao and Nantes

From the 13th century, merchants and mariners hailing from the northern Atlantic coast of Spain were instrumental in establishing a network of burgeoning settlements. This expansion was pivotal in integrating the northern peninsular maritime towns into the bustling trade routes of Western Europe. It is widely acknowledged that the Cantabrian traders made significant contributions, notably in recognizing the strategic importance of certain French Atlantic ports like Nantes and La Rochelle. Furthermore, they played a key role in fostering the regional interactions among Brittany, Normandy, Anjou, and Poitou, which were crucial to the late medieval Atlantic trade dynamics (SolórzanoTelechea, 2009). In the 13th and 14th centuries, historical records reveal the presence of merchants, sailors, captains, and pirates from Northern Spain, specifically from regions such as La Coruña, Avilés, Santander, Laredo, and Bilbao, in various significant and midsized European port towns. This presence grew even more pronounced in the 15th century. During this time, these individuals either operated as representatives for the prominent international traders based in Burgos, Medina del Campo, and Seville, or they conducted their business autonomously. They engaged in a range of activities, including commerce, transportation, piracy, and privateering. Their influence and activities were a testament to the dynamic maritime culture of the time, reflecting the complex interplay of economics, politics, and social dynamics that characterized the era's trade and navigation (Thompson, 1994).

Historically, the intricacies of the relationships between merchants and ship operators from Bilbao and their counterparts in Nantes during the late Middle Ages have remained somewhat obscure. The establishment of corporative institutions aimed at resolving disputes related to commerce and navigation further complicates the understanding of these interactions. Despite the significance of these connections in shaping early trade networks, details about them have been limited and lacking in precision. This gap in historical knowledge has persisted, leaving a nebulous understanding of the economic and social dynamics of the period. Efforts to clarify these relationships and institutional roles are crucial for a comprehensive grasp of the mercantile and maritime history of the Late Middle Ages (Sarrazin, 1991; Rivera, 2018). The historical presence of a Castilian settlement in the Sainte-Croix parish from the 13th century remains a subject of debate, though records from the subsequent century confirm its existence. These early institutions laid the groundwork for enduring and fruitful bilateral ties, transcending conventional trade relationships by recognizing each other as preferred trading partners and bestowing mutual benefits akin to those granted to the most favored nations in international trade. The efficacy of these diplomatic tools was evident in the 15th century when trade was particularly robust—Brittany, then a semiautonomous duchy with an economy that complemented Castile's, especially along the Cantabrian coast, saw the establishment of the Cofradía de la Contratación (Guild of Contracting). Even after the French monarchs assumed the title of Duke of Brittany later in the century, these advantageous connections were quickly reestablished after sporadic conflicts, despite the ongoing hostilities between the French and Spanish crowns. By the 16th century, the entity responsible for mediating peace and conducting negotiations between Nantes and Bilbao had evolved into the Compañía del Salvo Conducto (Greif, 2006).

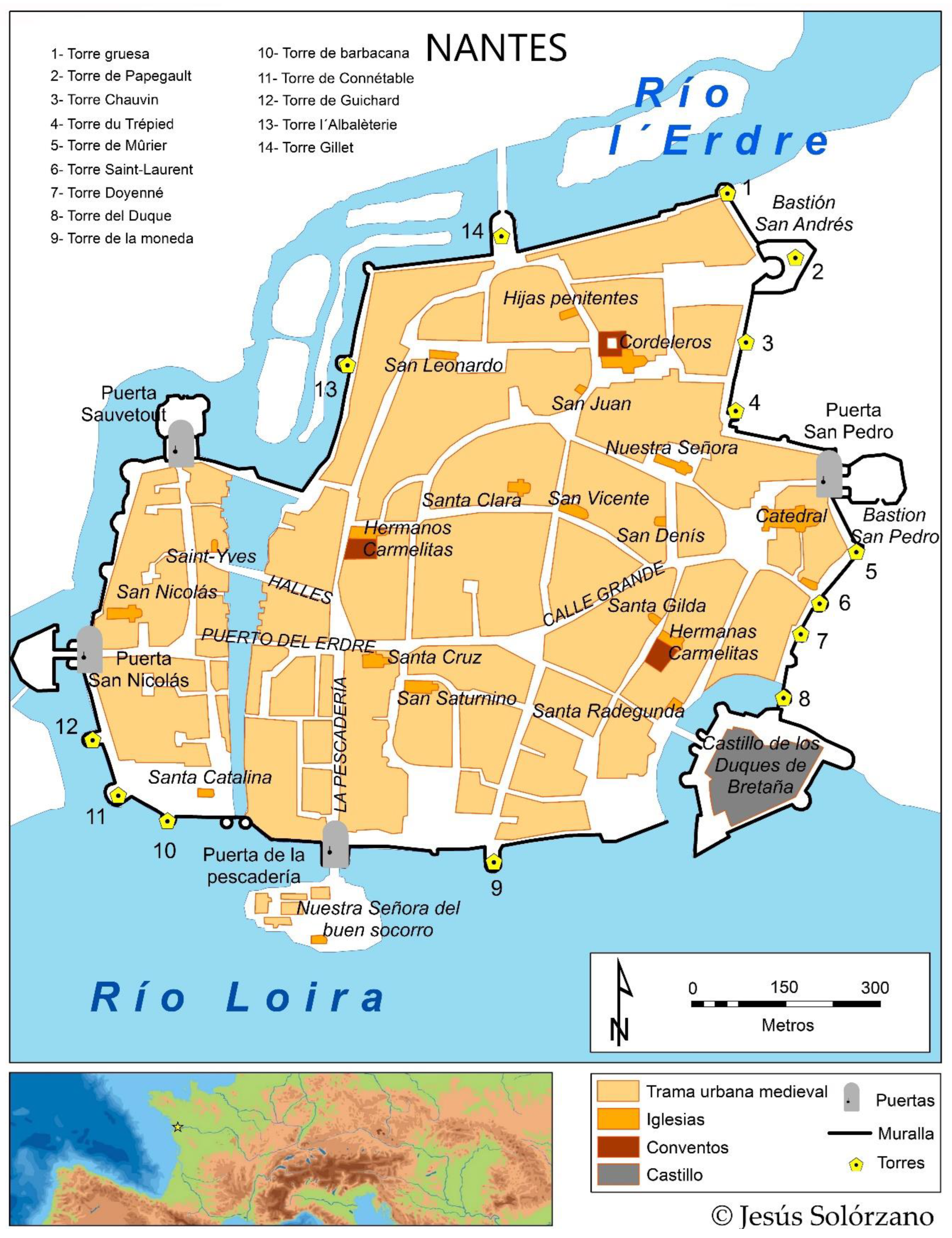

Figure 1.

Nantes in the 15th century.

Figure 1.

Nantes in the 15th century.

Figure 1.

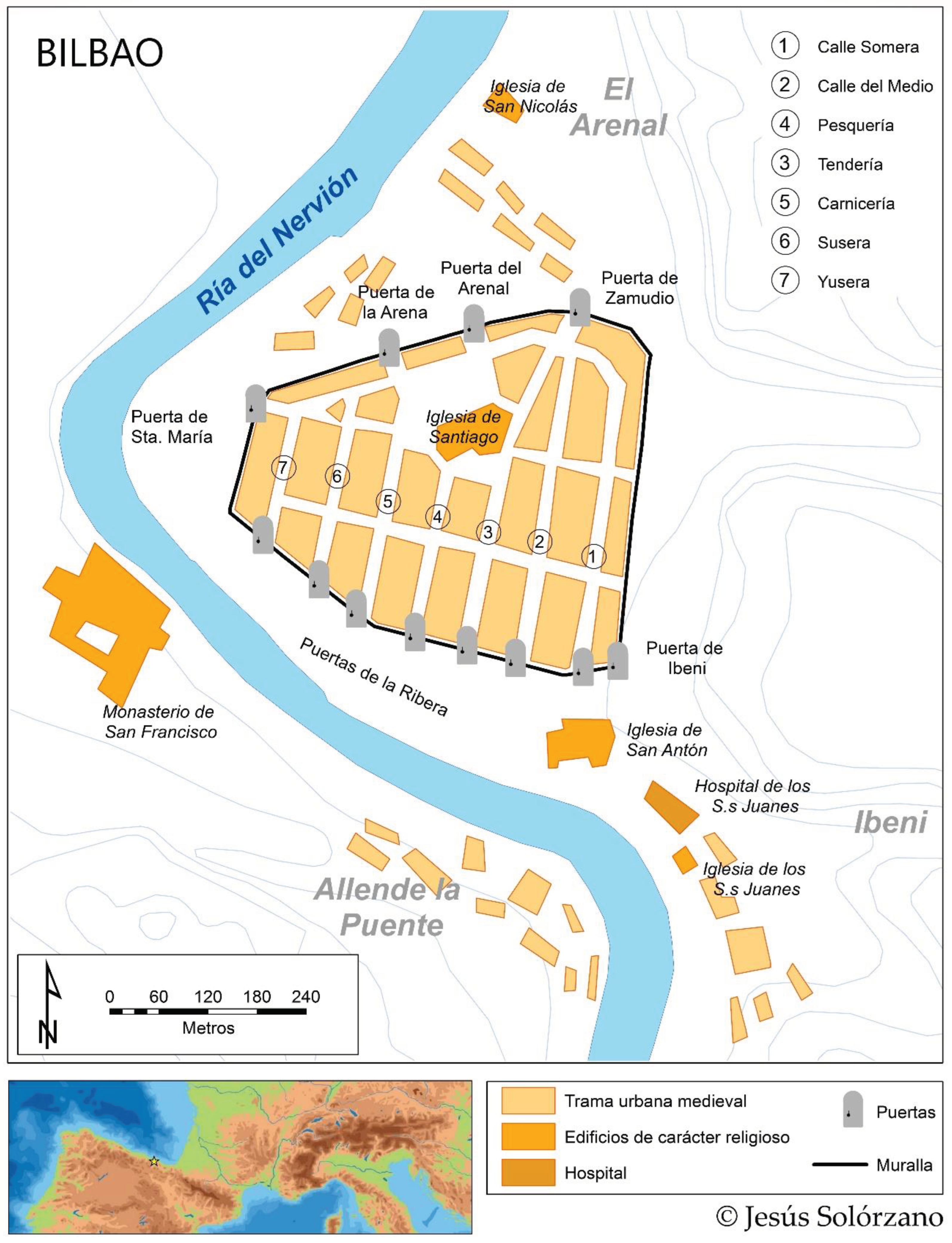

Bilbao in the 15th century.

Figure 1.

Bilbao in the 15th century.

During the 14th century, merchants from Nantes established themselves in Bilbao, and not long after, Bilbao's merchants reciprocated by settling in the Breton town. This mutual exchange fostered a collaborative relationship, leading to a reciprocal privileged treatment. The partnership was solidified when Bilbao extended the same rights and privileges to the merchants and sailors from Nantes as it did to its own citizens. Nantes, in turn, reaped the benefits of a neutrality policy set by the Duke of Brittany. This policy positioned Nantes as one of the four Castilian trading posts, alongside La Rochelle, Rouen, and Bruges, strategically placing it to influence the control of the lucrative wool trade (Brown, 2018). In the year 1372, a significant commercial treaty was orchestrated by Duke Jean IV of Brittany, engaging with the Biscayan towns, a precursor to a subsequent agreement. This earlier accord was followed by a notable 1430 treaty cosigned by his successor, Jean V, and the Castilian monarch, King Juan II. This latter treaty heralded the inception of a substantial Castilian settlement within the city of Nantes. As stipulated within the treaty's provisions, this colony was to be administered by a consul, notary, and purser, collectively exercising jurisdiction over the Spanish mercantile community in Brittany. The year 1435 marked the ratification of a camaraderie pact between Bilbao's merchants and their counterparts in Nantes. This pact, imbued with devotional elements, laid the groundwork for what would evolve into an international mercantile brotherhood, the Cofradía de la contratación, a guild alliance of a unique international character (Archives Départementales de Loire [hereafter: ADL], E 124; Blanchard, 1890). The accord in question was rooted in precedents established in 1428, when Castile and the Duke of Burgundy entered into a series of agreements. These early treaties conferred certain rights upon Castilian traders operating within Flanders, a region of high commercial importance at the time. The significance of these privileges was further underscored when, several decades later, they received the formal endorsement of Charles VIII. As both the reigning monarch of France and the duke consort of Brittany, his sanction in the years 1487 and 1491 lent considerable weight to the original terms, thereby reinforcing the stature of Castilian merchants within the European trade networks of the late Middle Ages. This sequence of events not only highlights the interconnected nature of European polities but also underscores the enduring influence of commercial interests in shaping diplomatic relations (ARCV, Pergaminos, 104, 4; Moal, 2008; Guiard, 1913). The establishment of this fraternal bond resulted in the creation of a mutual tribunal endowed with consular authority, a subject we will explore through particular instances. Additionally, the Nantes traders designated an envoy in Bilbao, authorized to partake in the tribunal's sessions and contribute to its discussions, while the Bilbao merchants were accorded similar privileges in Nantes. Likewise, the Castilian wool incurred minimal taxation in Nantes, just as the levies on Breton cloth imports remained low in Bilbao. Overall, the accords yielded benefits for both municipalities.

The Guild of the Contratation established its base within the Saint Francis monastery's chapel in Nantes, a place where Basque merchants had conducted their trade for years. It was in this sacred space that the guild convened to deliberate, worship, and perform its ceremonial duties. Governed by regulations set forth by the Bilbao consuls, the guild operated under a framework that was welldocumented in the late fifteenthcentury port records of Bilbao, which referred to the "cónsoles de los mercaderos de la Naçión de España, estantes en la çiudad de Nantes" (the consuls of the merchants of the Nation of Spain residing in the city of Nantes). These consuls mandated tolls on all maritime commerce and goods arriving at the port from Castile, with the collected funds earmarked for the maintenance and repair of the guild's fa-cilities, as well as other services essential to the merchant community. However, in 1476, a dispute arose when the Bilbao consuls reported that certain merchants, especially those from Guipúzcoa, were defying the longstanding obligation to pay these fees. This defiance prompted the Catholic Monarchs to step in, decreeing that the statutes authored by the Castilian consuls in Nantes be maintained and adhered to without exception (Mathorez, 1912; Recalde, 1988).

For over a century, Brittany had been a key commercial partner of Castile, particularly the city of Bilbao, with which it had established strong trade connections and signed agreements that designated them as preferred associates. Despite this longstanding partnership, disputes did occasionally emerge, leading to confrontations and the issuance of letters of marque and reprisal. In 1488, the Catholic Monarchs responded to a petition from Juan de Arbolancha, a merchant from Bilbao, who sought redress for wrongs inflicted by certain Breton individuals. The monarchs' letter stipulated a thirty day waiting period before any action could be taken, during which time they hoped the conflict would be resolved. This grace period was later extended by an additional fifty days amidst ongoing negotiations involving the Castilian rulers and the Duke of Brittany. Should Arbolancha have detained any Bretons during this time, he was instructed to release them upon posting a bond, en suring compensation in the event the talks failed. If no settlement was reached within the allotted time, Arbolancha was authorized to target subjects of the Duchy of Brittany, capturing their ships and goods to recover his losses, all without facing legal repercussions (AGS, RGS, 1488-01, 260).

The robust economic ties between Biscay and Brittany were so crucial for the flourishing of both regions that it was deemed prudent to mitigate the effects of potential commercial conflicts that might arise, leading to reciprocal punitive actions. The harmonious relationship between the Castilian traders and the Breton mariners was evident in the utilization of Breton vessels for the conveyance of goods along the maritime path connecting Flanders and Castile. In the year 1483, grievances were lodged in the courts of England by an emissary of the "Consuls of the Nation of Spain in Bruges", identified as Pedro de Salamanca, acting in a legal capacity, on account of several Spanish nationals who had suffered the wrongful confiscation of their merchandise transported on Breton ships (Childs, 1978). In the year 1489, an intriguing pact was forged between the Biscayans and the Bretons, stipulating that Breton traders operating in Castile were obliged to pay merely 3% of their goods' value. This measure was to circumvent any retaliatory actions sanctioned by the letter of marque possessed by Arbolancha. Essentially, it was agreed that the Bretons would collectively shoulder the repercussions associated with this letter of marque, apportioning the said percentage across their merchandise. This was a strategic move to prevent the potential confiscation of all goods belonging to those randomly targeted. Should any individual decline to comply with this arrangement willingly, they would be subjected to the stipulations of the preceding letter of marque. In enforcing this agreement, Arbolancha and his representatives were authorized to compel Breton merchants and their associates to swear an oath on the goods they had disembarked. Furthermore, these merchants were required to present a comprehensive list of their cargo upon their arrival in Castilian harbors, thereby enabling the collection of the aforementioned 3% levy (AGS, RGS, 1489-01, 381).

The essence of such a letter of marque and reprisal is captured within a historical document dating back to the year 1492. This type of letter was a government license that authorized a private person, known as a privateer, to attack and capture vessels of a nation at war with the issuer. It was a significant part of naval warfare during the age of sail, serving as a legal form of piracy. The document from 1492 likely detailed the terms and conditions under which the privateer could operate, the specific targets, and the division of spoils. It would have served as a crucial piece of authorization, empowering individuals to act on behalf of their nation against enemy states during times of conflict. Letters of marque and reprisal were a testament to the complexities of maritime law and the interplay between private interests and national authority during the last decades of the 15th century (AGS, RGS, 149212, 206). In a manner akin to other decrees of its kind, the monarchs relayed orders to both civil and military officials, as well as to the naval contingent from Biscay and Guipúzcoa, regarding the ship owned by Juan de Arbolancha, which he coowned with his siblings and was captained by Lope de Arbolancha, one of his brothers. This ship was subject to boarding in the year 1484. During the time of this event, the vessel was laden with an assortment of goods including kermes and woolen fabrics, small wares, leather goods, and metals such as tin and lead, in addition to sacks filled with wool. This cargo was aboard near the English harbor of Antona, known today as Southampton, situated on the isle of Oyque, or Wight. The offensive was executed by a flotilla of five ships acting under the authority of the Duke of Brittany, notwithstanding the ongoing truce and active alliances between the Duchy of Brittany and the Kingdom of Castile. This action was in direct violation of the assurances and safeconduct documents issued by the Duke, which were in the possession of the ship's master. The duke had previously assured his protection and safeguarding of the ship, and there were no recorded transgressions committed by the vessel or its crew against the Duchy or its people. Among the aggressor ships was La Figa, helmed by Captain Juan Viemo of Morlaix; La Grifona, commanded by Rochar Hetiena with a certain Robert serving as pilot; La Picada, under the leadership of Juan de Esquilen and Guillaume Picart; and La Barca of Morlaix, steered by Yvo Lamrux and Yvo Bramaner. Accompanying these ships were numerous constables, shipowners, sailors, and denizens of the Breton Duchy.

Disregarding the Castilian flag and emblem, the attacking ships unleashed their cannons upon the Santiago, inflicting damage that resulted in the demise and injury of several crew members. The assault led to the plundering of the ship's cargo and equipment, culminating in a loss valued at 18,000 gold crowns. The aggressors seized control of the vessel along with the surviving crew, who, despite their appeals and references to treaties and assurances that should have protected them, were ignored. The captured crew were confined below deck, subjected to the cruelty of being given only seawater to drink and deprived of food. This inhumane treatment led to the tragic death of fifteen individuals and the poisoning from seawater of the others who remained captive. Lope de Arbolancha, in a desperate search for assistance, found none in the Breton towns of SaintPoldeLéon and Morlaix, despite reasserting his Castilian identity and the treaties that should have guaranteed the safety of the ship. The local authorities ignored his entreaties, permitting the assailants to divide the spoils of the Castilian ship amongst themselves (González Arce, 2021).

Notwithstanding, the duke of Brittany did grant the injured shipmaster a document allowing him to seek justice in these ports, and prohibiting the seizure of said assets, which could not be sold or distributed until the ducal council had ruled accordingly. However, when the plaintiff presented this order before the local authorities and the assailants, far from respecting it, they attempted to murder both Arbolancha and the ducal judge who was with him, forcing them to flee to the duke’s court in Nantes. Here, the shipmaster presented a claim before the duke and the treasurer of Brittany, keeper and justice of peace and of the alliances concluded with Castile—this position of judge keeper, or chancellor, of the alliances, is the one discussed above when describing the Castilian consulate in, as a mediator and arbitral judge between Nantes and Bilbao—against the naval delinquents and the citizens of the ports that supported them. The judge summoned the defendants before the court, of whom the plaintiff demanded the 18,000 gold crowns, plus expenses and damage. The plaintiff also requested that the defendants be captured and imprisoned. The of-fenders were sent to prison only to be liberated before Lope de Arbolancha was granted justice.

Juan de Arbolancha, acting on behalf of his sibling, sought justice from the Catholic Monarchs, urging them to intervene and ensure his grievances were heard by the duke. Despite the noble's assurance to incarcerate the culprits, re-imprisoning some, the lack of Breton witnesses to corroborate the Castilian's account, due to the isolated nature of the assault, hindered his pursuit of justice. This absence of wit-nesses led the accused to shift blame onto others. In a desperate bid for truth, Arbolancha proposed an ordeal by trial, anticipating that the accused would reveal their guilt under duress. Nevertheless, the alleged pirates were released once more, and the judge decreed the auctioning of the pilfered goods, with proceeds allocated to Arbolancha's shipping costs, disregarding his additional sufferings. Persistently, the plaintiff demanded the rearrest of the offenders, which eventually led to confessions that substantiated his allegations.

In the end, his efforts were in vain, as neither the duke nor his council would meet his demands for compensation for the damages incurred. This led him to seek a letter of marque and reprisal from Isabel and Fernando. However, before issuing such a letter, the monarchs demanded that the duchy's officials once more consider the case, directing that it be presented to two members of the ducal council. They determined that the plaintiff had indeed suffered losses to the tune of 25,000 escudos. Contrarily, the ducal council assessed the damages at a mere 6,000 francs, an amount Arbolancha found unacceptable. Persisting in his quest for justice, he sought further royal intervention and insisted on the issuance of the letter of reprisal. Amidst this backandforth, and under the looming threat of reprisal—which had been drafted to pressure the duke but had been postponed—the ducal council increased the compensation offer to 12,000 francs. Yet again, this was a figure that Arbolancha could not countenance, leading to its rejection. The Breton envoys implored the Castilian rulers to desist from granting or implementing the letter of reprisal. The Royal Council of Castile aligned with Arbolancha's stance, initially decreeing a compensation of 18,000 crowns plus expenses, which the monarchs subsequently reduced to 15,000 crowns, showing leniency towards the duke and his representatives. The ducal council contested, asserting the plaintiff was denied justice in his legitimate appeals and proposed that, to circumvent court bias, French jurors from Paris, Bordeaux, or other scholarly cities should decide in an international arbitration. However, this suggestion was belated; Arbolancha confirmed his claim for 15,000 crowns without postponement, yet the ducal chancellor declined to fulfill any payment, neglecting even the duke's directives. Consequently, the Catholic Monarchs resolved to issue the letter of marque and reprisal for 18,000 crowns and an additional 5,000 for costs, targeting Brittany nationals and their possessions, cumulating to 23,500 crowns. Moreover, the costs for enforcing the reprisal, as determined by the judicial authorities of the adjudicating cities, were to augment this amount (AGS, RGS 1492-12, 206).

In the historical context, the municipalities of Bermeo, Bilbao, La Corunna, and Betanzos collectively opposed the directives issued by Juan de Arbolancha. These directives pertained to the dissemination of his letter of reprisal among the Breton people, which imposed a tax based on the value of goods they imported. This resistance was a significant act of defiance against what was perceived as an unjust levy, reflecting the towns' commitment to protecting their economic interests and autonomy in trade matters. It underscores the complexities of trade relationships, and the measures local authorities were willing to take to safeguard their communities from financial burdens deemed excessive or unfair (Ferreira Priegue, 1988). Consequently, the provost of Bilbao, Tristán de Leguizamón, perceiving a threat to his commercial interests, joined forces with his representative, Juan de Estella, to initiate legal proceedings against Arbolancha. They leveled allegations that Arbolancha coerced certain Breton vessels departing from the respective harbors to comply with his requisitions, leveraging the menace of confiscating their vessels and merchandise. This legal action underscored the tensions arising from maritime commerce practices and the protection of local economic stakes at the end of the Middle Ages (AGS, RGS 150006, 347; AGS, CC, CED 5, 289, 1; 8, 41bis, 3). For several years, he had engaged in extortion, accumulating a fortune far exceeding his financial losses. The accused countered with a claim of possessing royal sanction to levy a 3% tax on the cargo of Breton ships, aiming to collect up to 1.04 million maravedis, an amount he had not yet fully acquired. Nevertheless, the judicial process proceeded unabated, with both parties amassing testimonies as evidence. Leguizamón insisted that Arbolancha submit to the Royal Council a documented account of the proceedings he initiated against his Breton aggressors, to ascertain the full indemnity he sought. Moreover, the Catholic Monarchs issued directives to the local magistrates in Flanders and the Duchy of Brittany, as some witnesses slated to support Leguizamón's case resided there and were required to furnish written statements in answer to a questionnaire drafted by the claimant, to be forwarded to Castile. A similar approach was taken with the officials of the coastal communities in Cantabria and Galicia (AGS, RGS 1494-07, 327; 1494-10, 250; 1494-11, 503-504; 1494-12, 187, 198-199; 1495-02, 516).

Commerce between Nantes and Bilbao remained uninterrupted at the dawn of the 16th century despite numerous challenges,. The exchange of goods between the Cantabrian seaports and Brittany flourished, largely benefiting Breton merchants and shipmasters throughout the first half of the century. Their vessels were primarily engaged in ferrying commodities such as iron, steel, oranges, and wool to Brittany. This was partly due to a scarcity of ships from the Bay of Biscay, which were otherwise occupied with even more lucrative ventures. A notable instance from 1539 highlights this era's trade dynamics: Ibon Larger, a Penmarch merchant, openly admitted to having loaded steel purchased in Bilbao onto his ship, captained by Juan L Due, a notable figure from Nantes. This period marked a significant chapter in maritime commerce, characterized by robust trade networks and the strategic utilization of available shipping resources (Archivo Histórico Provincial de Guipúzcoa, legajo 2/1883, A, f. 104r). Trade and maritime transport were essential for the inhabitants of both regions, providing crucial resources. These communities endeavored to surmount the perils of the sea by creating trust networks, bolstered by shared institutions for risk management. However, their attempts were ultimately eclipsed by sovereign policies aimed at extending state jurisdiction over maritime domains through the criminalization of certain sea activities. This was part of a broader strategy to augment state control over maritime trade.