Submitted:

10 April 2024

Posted:

11 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

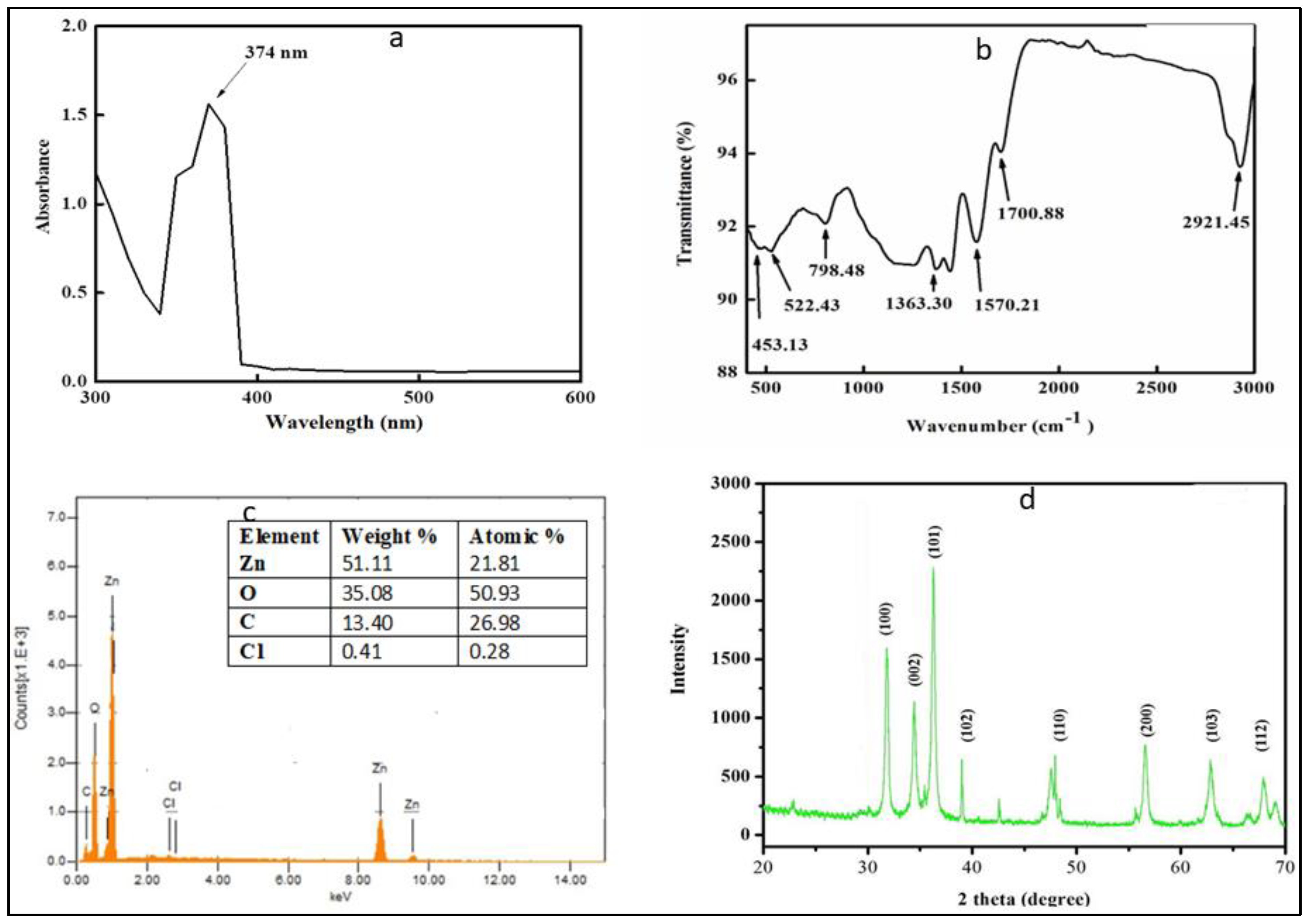

2.1. UV-Visible Spectrophotometry and Fourier Transform Infrared Analysis

2.2. Energy-Dispersive X-Ray and X-Ray Diffraction Analysis

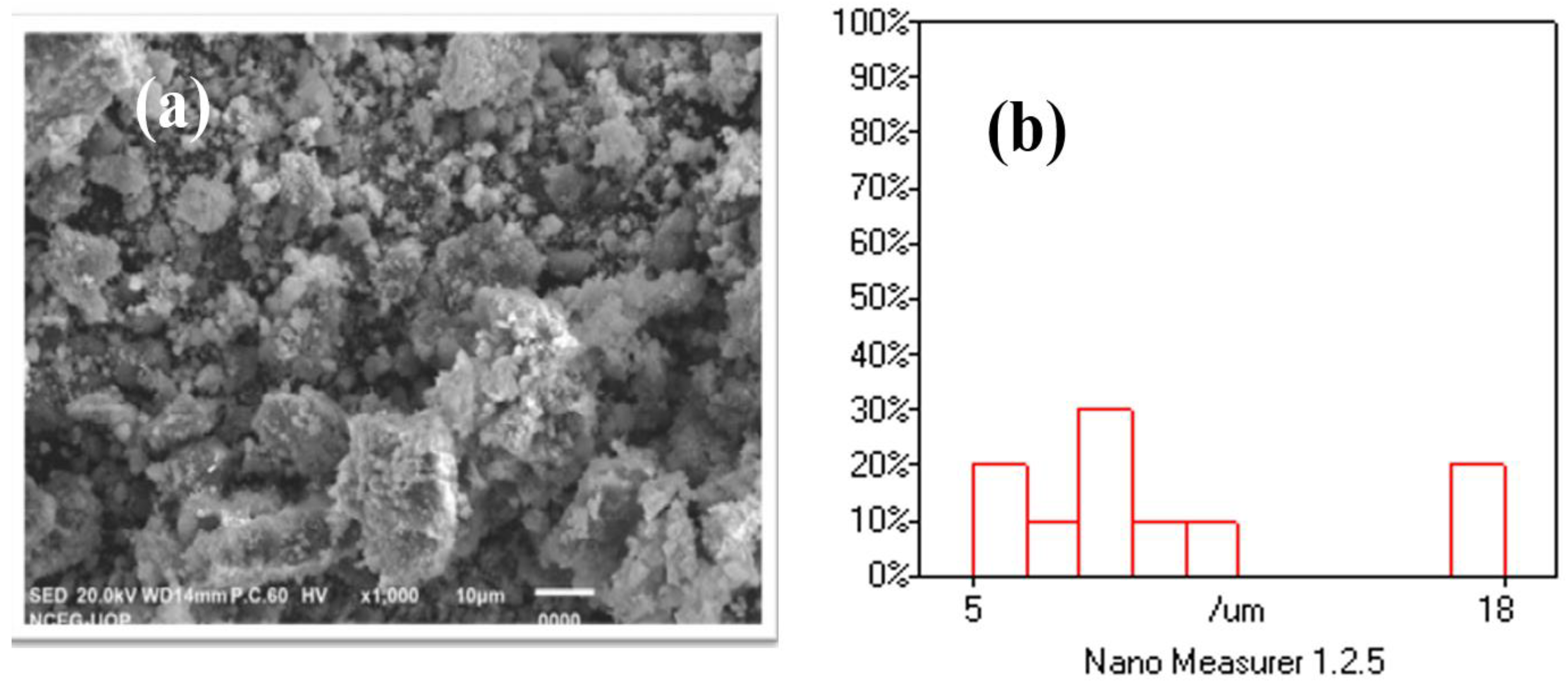

2.3. Scanning Electron Microscopic and Nano Measurer Particle Size Analysis

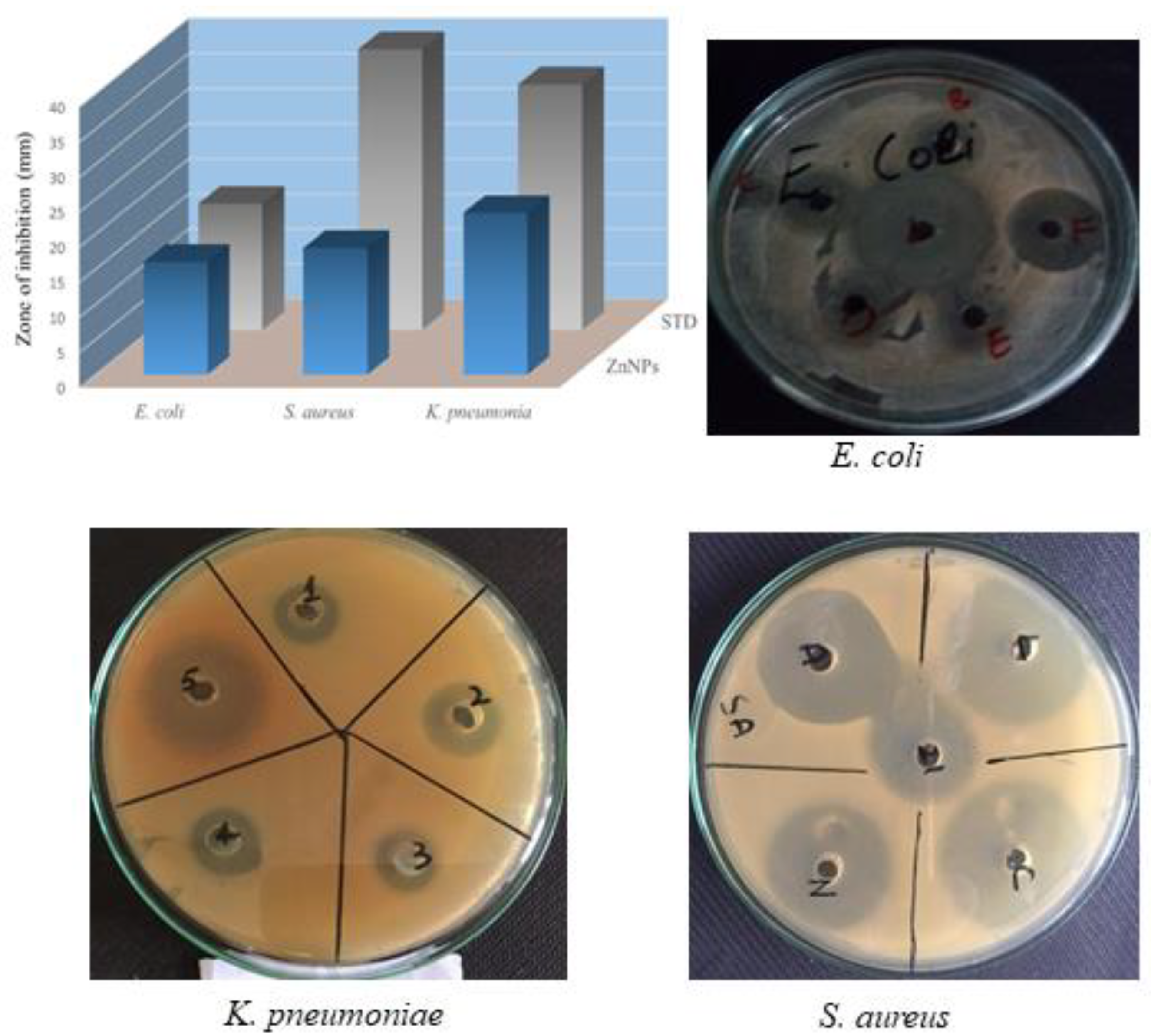

2.4. Antibacterial Activity

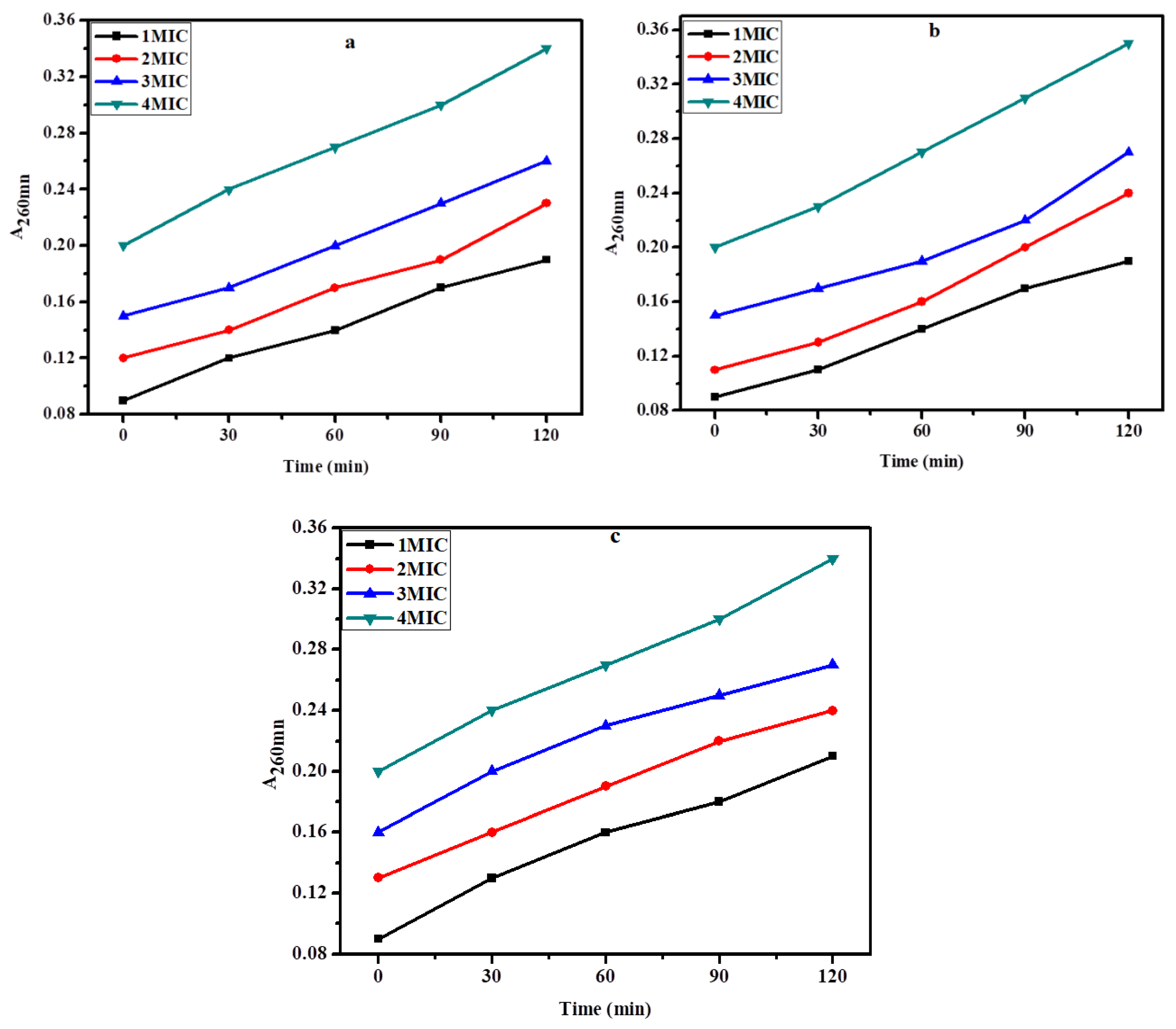

2.5. Membrane Damage Bioassay

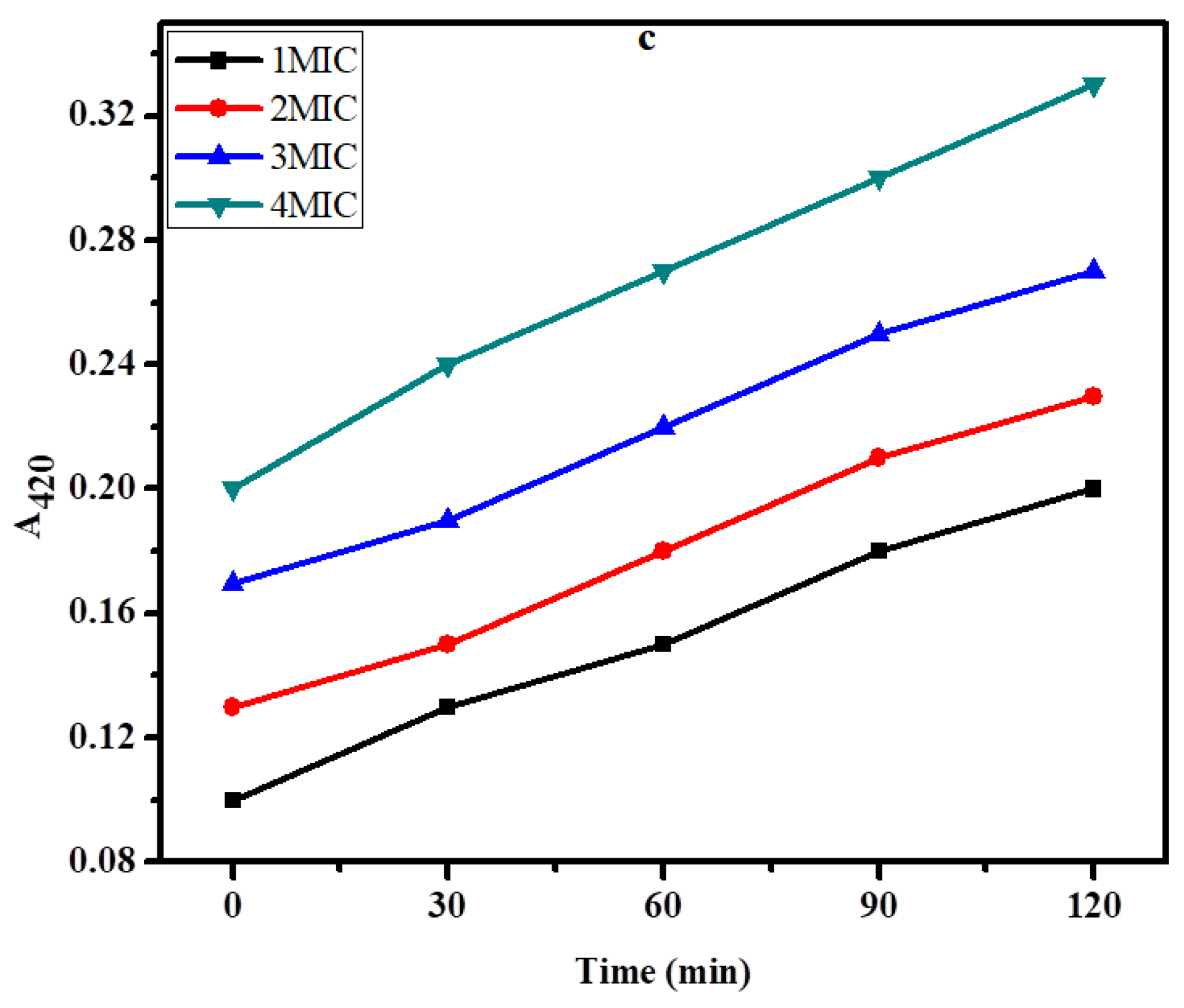

2.6. Inner Membrane Permeability Bioassay

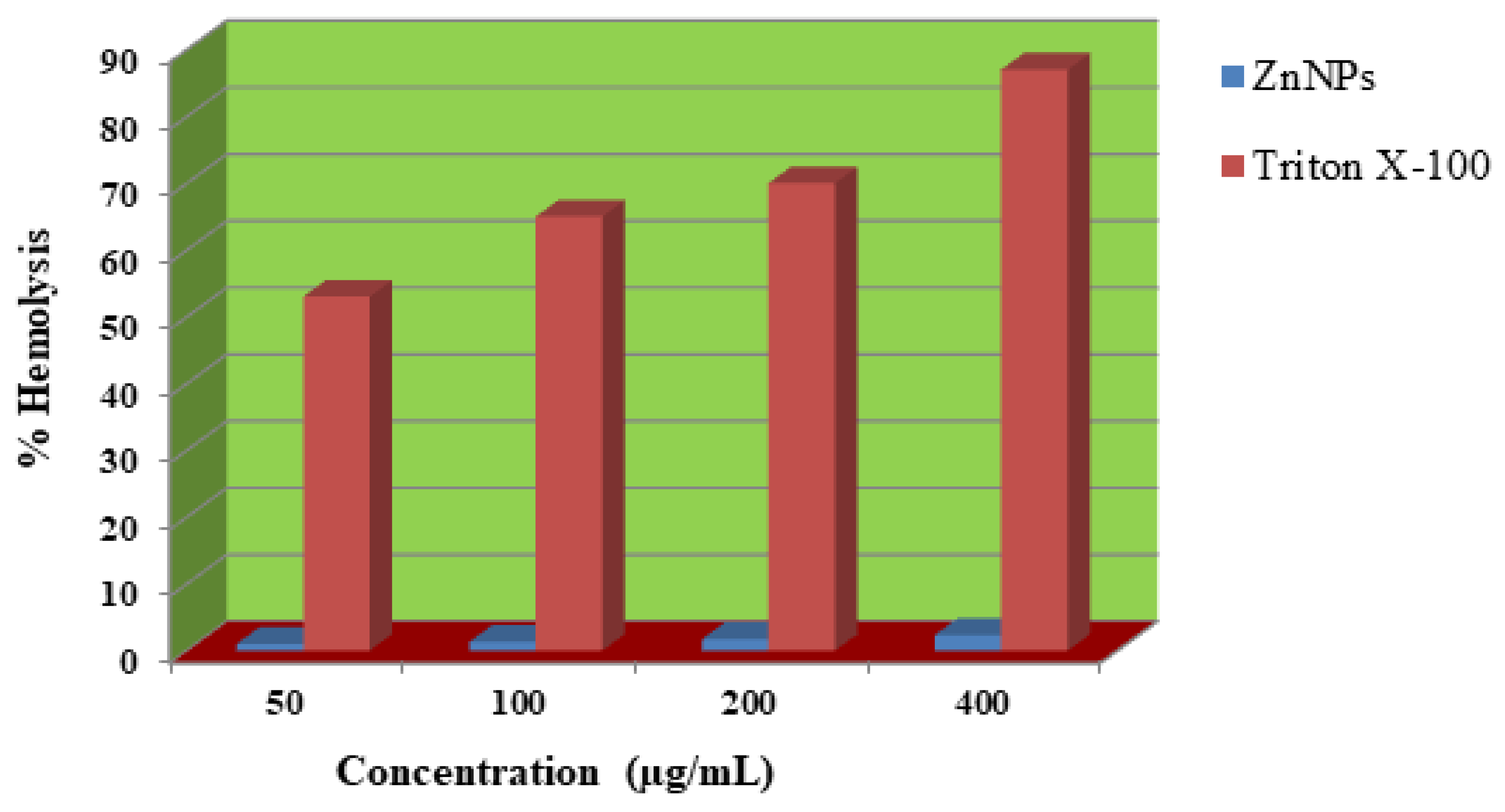

2.7. Hemolytic Activity

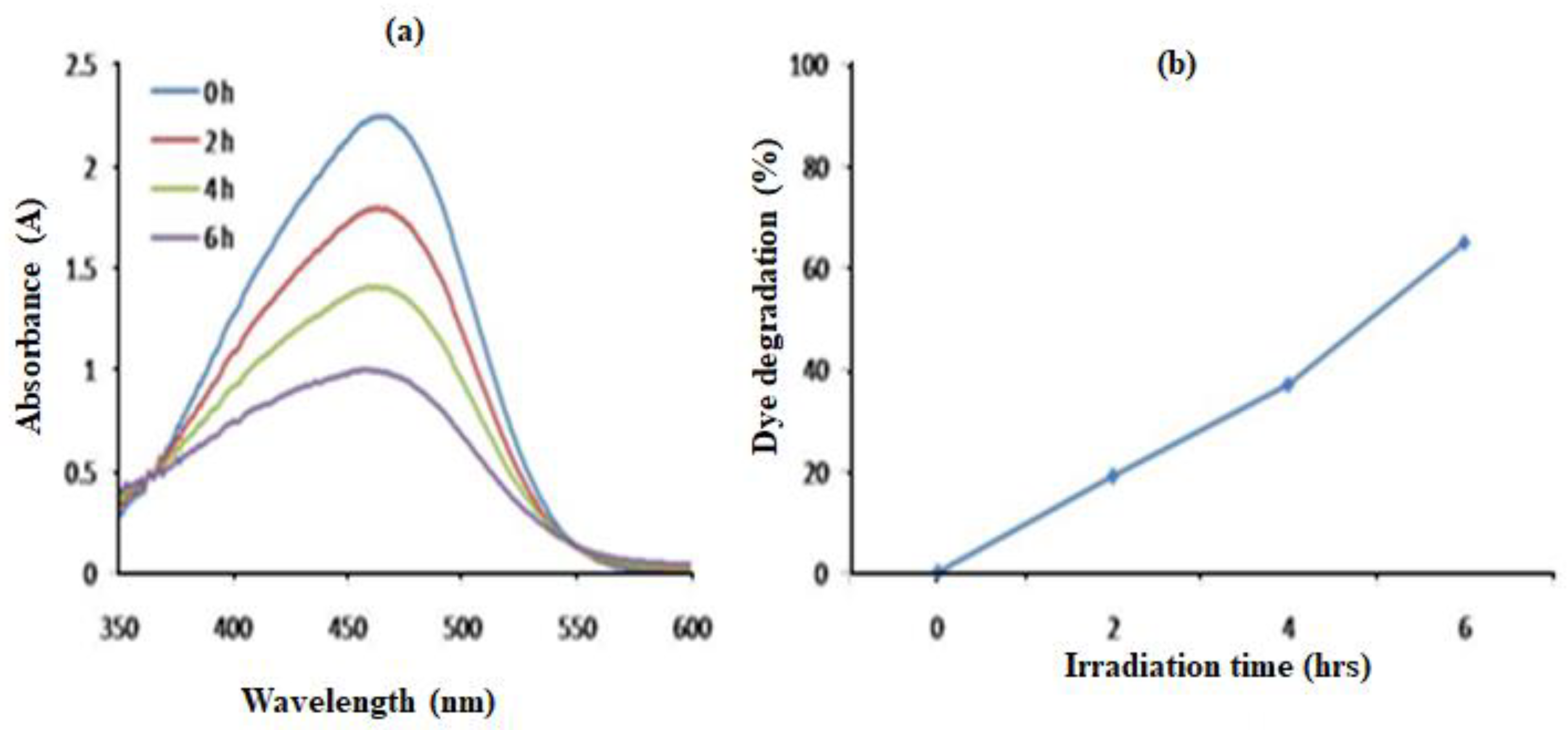

2.8. Photocatalytic Degradation of Synthetic Methyl Orange Dye

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Collection of Plant and Preparation of Plant Extract

4.2. Biosynthesis and Characterization of Zinc Nanoparticles

4.3. Antibacterial Screening

4.4. Membrane Damage Assay

4.5. Inner Membrane Permeabilization Bioassay

4.6. Hemolytic Assay

4.7. Photocatalytic Degradation of Synthetic Methyl Orange Dye

4.8. Statistical Analysis

Conclusions

Declaration of competing interest

Acknowledgments

References

- Ahmad, A.; Khan, M.; Sufyan Javed, M.; Hassan, A.M.; Choi, D.; Khawar, M.R.; Waqas, M.; Ayub, A.; Alothman, A.A.; Almuhous, N.A. Eco-Benign Synthesis of α-Fe2O3 Mediated Trachyspermum Ammi: A New Insight to Photocatalytic and Bio-Medical Applications. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2024, 449, 115423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darra, R.; Hammad, M. Bin; Alshamsi, F.; Alhammadi, S.; Al-Ali, W.; Aidan, A.; Tawalbeh, M.; Halalsheh, N.; Al-Othman, A. Wastewater Treatment Processes and Microbial Community. In Metagenomics to Bioremediation: Applications, Cutting Edge Tools, and Future Outlook; 2022; pp. 329–355 ISBN 9780323961134.

- Salam, M.A.; Al-Amin, M.Y.; Salam, M.T.; Pawar, J.S.; Akhter, N.; Rabaan, A.A.; Alqumber, M.A.A. Antimicrobial Resistance: A Growing Serious Threat for Global Public Health. Healthc. 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sudarshan, S.; Harikrishnan, S.; RathiBhuvaneswari, G.; Alamelu, V.; Aanand, S.; Rajasekar, A.; Govarthanan, M. Impact of Textile Dyes on Human Health and Bioremediation of Textile Industry Effluent Using Microorganisms: Current Status and Future Prospects. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2023, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, T.; Repon, M.R.; Islam, T.; Sarwar, Z.; Rahman, M.M. Impact of Textile Dyes on Health and Ecosystem: A Review of Structure, Causes, and Potential Solutions; Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2023; Vol. 30; ISBN 0123456789.

- Jorge, A.M.S.; Athira, K.K.; Alves, M.B.; Gardas, R.L.; Pereira, J.F.B. Textile Dyes Effluents: A Current Scenario and the Use of Aqueous Biphasic Systems for the Recovery of Dyes. J. Water Process Eng. 2023, 55, 104125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, S.; Rauf, A. Role of Nanomaterials for Removal of Biomaterials and Microbes from Wastewater. In Nanotechnology Horizons in Food Process Engineering; 2023; pp. 303–342.

- Madhan, G.; Begam, A.A.; Varsha, L.V.; Ranjithkumar, R.; Bharathi, D. Facile Synthesis and Characterization of Chitosan/zinc Oxide Nanocomposite for Enhanced Antibacterial and Photocatalytic Activity. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 190, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motakef-Kazemi, N.; Yaqoubi, M. Green Synthesis and Characterization of Bismuth Oxide Nanoparticle Using Mentha Pulegium Extract. Iran. J. Pharm. Res. 2020, 19, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fritea, L.; Banica, F.; Costea, T.O.; Moldovan, L.; Dobjanschi, L.; Muresan, M.; Cavalu, S. Metal Nanoparticles and Carbon-Based Nanomaterials for Improved Performances of Electrochemical (Bio)sensors with Biomedical Applications. Materials (Basel). 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mba, I.E.; Nweze, E.I. Nanoparticles as Therapeutic Options for Treating Multidrug-Resistant Bacteria: Research Progress, Challenges, and Prospects. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thambirajoo, M.; Maarof, M.; Lokanathan, Y.; Katas, H.; Ghazalli, N.F.; Tabata, Y.; Fauzi, M.B. Potential of Nanoparticles Integrated with Antibacterial Properties in Preventing Biofilm and Antibiotic Resistance. Antibiotics 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, M.; Kumar, S.; Saxena, N.; Nafees, A. Photocatalytic Degradation of Dyes Present in Industrial Effluents: A Review. ChemistrySelect 2023, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hachem, K.; Ansari, M.J.; Saleh, R.O.; Kzar, H.H.; Al-Gazally, M.E.; Altimari, U.S.; Hussein, S.A.; Mohammed, H.T.; Hammid, A.T.; Kianfar, E. Methods of Chemical Synthesis in the Synthesis of Nanomaterial and Nanoparticles by the Chemical Deposition Method: A Review. Bionanoscience 2022, 12, 1032–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qamar, S.U.R.; Ahmad, J.N. Nanoparticles: Mechanism of Biosynthesis Using Plant Extracts, Bacteria, Fungi, and Their Applications. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezealigo, U.S.; Ezealigo, B.N.; Aisida, S.O.; Ezema, F.I. Iron Oxide Nanoparticles in Biological Systems: Antibacterial and Toxicology Perspective. JCIS Open 2021, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafey, A.M. El Green Synthesis of Metal and Metal Oxide Nanoparticles from Plant Leaf Extracts and Their Applications: A Review. Green Process. Synth. 2020, 9, 304–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidhu, A.K.; Verma, N.; Kaushal, P. Role of Biogenic Capping Agents in the Synthesis of Metallic Nanoparticles and Evaluation of Their Therapeutic Potential. Front. Nanotechnol. 2022, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, J.; Rolta, R.; Salaria, D.; Ahmed, A.; Chandel, S.R.; Regassa, H.; Alqahtani, N.; Ameen, F.; Amarowicz, R.; Gudeta, K. In Vitro and in Silico Properties of Rhododendron Arboreum against Pathogenic Bacterial Isolates. South African J. Bot. 2023, 161, 711–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Chaudhary, S.; Harchanda, A. Rhododendron Arboreum : A Critical Review on Phytochemicals, Health Benefits and Applications in the Food Processing Industries. Curr. Nutr. Food Sci. 2021, 18, 287–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, S.; Ahmed, B.; Khan, M.S.; Al-Shaeri, M.; Musarrat, J. Inhibition of Growth and Biofilm Formation of Clinical Bacterial Isolates by NiO Nanoparticles Synthesized from Eucalyptus Globulus Plants. Microb. Pathog. 2017, 111, 375–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nisar, M.; Ali, S.; Qaisar, M. Preliminary Phytochemical Screening of Flowers, Leaves, Bark, Stem and Roots of Rhododendron Arboreum. Middle-East J. Sci. Res. 2011, 10, 472–476. [Google Scholar]

- Varela, M.F.; Stephen, J.; Lekshmi, M.; Ojha, M.; Wenzel, N.; Sanford, L.M.; Hernandez, A.J.; Parvathi, A.; Kumar, S.H. Bacterial Resistance to Antimicrobial Agents. Antibiotics 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panchal, P.; Paul, D.R.; Sharma, A.; Choudhary, P.; Meena, P.; Nehra, S.P. Biogenic Mediated Ag/ZnO Nanocomposites for Photocatalytic and Antibacterial Activities towards Disinfection of Water. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2020, 563, 370–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frallicciardi, J.; Melcr, J.; Siginou, P.; Marrink, S.J.; Poolman, B. Membrane Thickness, Lipid Phase and Sterol Type Are Determining Factors in the Permeability of Membranes to Small Solutes. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouyahya, A.; Abrini, J.; Dakka, N.; Bakri, Y. Essential Oils of Origanum Compactum Increase Membrane Permeability, Disturb Cell Membrane Integrity, and Suppress Quorum-Sensing Phenotype in Bacteria. J. Pharm. Anal. 2019, 9, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, B.; Hashmi, A.; Khan, M.S.; Musarrat, J. ROS Mediated Destruction of Cell Membrane, Growth and Biofilms of Human Bacterial Pathogens by Stable Metallic AgNPs Functionalized from Bell Pepper Extract and Quercetin. Adv. Powder Technol. 2018, 29, 1601–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anh Tran, V.; Khoa Phung, T.; Thuan Le, V.; Ky Vo, T.; Tai Nguyen, T.; Anh Nga Nguyen, T.; Quoc Viet, D.; Quang Hieu, V.; Thi Vo, T.T. Solar-Light-Driven Photocatalytic Degradation of Methyl Orange Dye over Co3O4-ZnO Nanoparticles. Mater. Lett. 2021, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, R.; Zhu, H.Y.; Fu, Y.Q.; Jiang, S.T.; Zong, E.M.; Zhu, J.Q.; Zhu, Y.Y.; Chen, L.F. Colloidal CdS Sensitized Nano-ZnO/chitosan Hydrogel with Fast and Efficient Photocatalytic Removal of Congo Red under Solar Light Irradiation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 174, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Du, Y.; Wang, X.; Sun, L. Chitosan Kills Bacteria through Cell Membrane Damage. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2004, 95, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.K.; Park, S.C.; Hahm, K.S.; Park, Y. A Helix-PXXP-Helix Peptide with Antibacterial Activity without Cytotoxicity against MDRPA-Infected Mice. Biomaterials 2014, 35, 1025–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| S.No | Sample | MIC (µg/mL) | MBC (µg/mL) | ||||

| E. coli | S. aureus | K. pneumoniae | E. coli | S. aureus | K. pneumoniae | ||

| 1 | ZnNPS | 94±0.18 | 47±0.11 | 34±0.21 | 185.43±0.16 | 94.86±0.84 | 72.71±0.47 |

| 2 | Levofloxacin | 11.72±0.82 | 0.35±0.11 | 50.17±0.41 | 23.43±1.03 | 7.82±0.45 | 97.75±0.9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).