1. Introduction

After completing the census of all the cultural assets within Schools, Departments and professors’ offices at the University of Genoa (UniGe), Italy, in July 2021, it was immediately clear to all the people involved in that process that such a remarkable cultural heritage should be accessible without any structural, organizational, or architectural constraints. In this respect, it was decided to set up a University Museum System (hereinafter referred to as SMA, i.e., “Sistema Museale di Ateneo”, in Italian), aiming to house, in a single online space, the whole cultural heritage of the university, properly digitized and archived, so that it is accessible to everyone like an interactive exhibition. Indeed, it is a huge amount of assets, including four structured museums, seven “ex-museums” with large collections, two botanical gardens, two biobanks, three large archives, over twenty smaller collections and more than thirty smaller archival funds.

Only thanks to digitization and transcription such a cultural heritage can be more easily discoverable, comprehensible, and freely accessible to the public for educational, research, and sharing purposes, in full adherence to the FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) [

1] and Open Science principles [

2]. However, for what concerns the transcription of manuscripts, despite several studies report good results in the use of Optical Character Recognition (OCR) and Handwritten Text Recognition (HTR), we observe that these tools are not sufficiently accurate for recognizing particularly fine handwriting or interferences caused by corrections, variations in stroke thickness, or the context in which the text is embedded, such as captions or signs [

3], as is the case of the majority of manuscripts in the UniGe collection.

For this reason, we decide to create a novel document transcriptions system relying on humans’ abilities and intuition rather than on automated systems. Hence, we decided to involve volunteer citizens in the transcription process, embracing the concepts of Citizen Science [

4], crowdsourcing, and public engagement [

5,

6], which represents the so-called “third mission”, i.e., the complex of activities aiming at generating knowledge outside the academic environment to the benefit of the social, cultural, and economic development. While the utilization of crowdsourcing initiatives is widespread and widely adopted nowadays, it has been shown that it is crucial to keep users consistently engaged. This not only helps mitigate the risk of not fully reaping the benefits of the initiative but also prevents the emergence of harmful behaviors resulting from the adopted solutions [

7]. Crowdsourcing, coupled with a competitive game design, motivates platform users not only to strive for improved performance but also to undertake a more extensive array of tasks [

8]. For this reason, an increasing number of crowdsourcing platforms are incorporating game-inspired techniques to boost user participation and enhance the quality of the produced work [

9]. The idea at the basis of such a novel system is captivating as many people as possible in the transcription activity -that is normally considered unappealing- making it an interesting and engaging experience, by using gamification mechanics and dynamics.

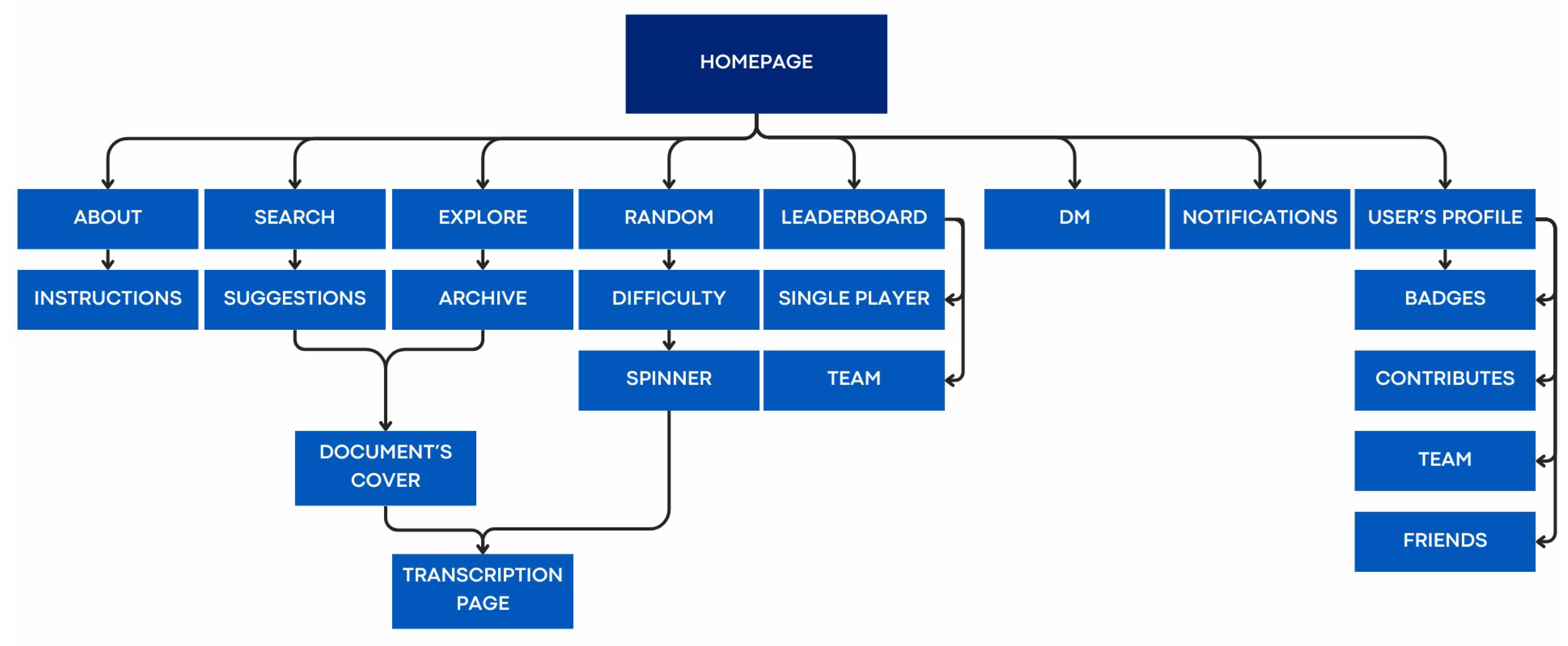

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. The ’Related Works’ section presents a comprehensive overview of similar endeavors in significant institutions globally, offering valuable perspectives on how these organizations have tackled the challenges associated with the transcription and digitization of cultural heritage. Subsequently, in

Section 3, the narrative shifts to a detailed exploration of the "University Museum System" at the University of Genoa (SMA-UniGe). This portion delves deep into the methodologies and goals of the project, which are centered around the consolidation and digital accessibility of the university’s extensive cultural heritage.

Section 4 is devoted to the gamification strategies proposed for the project. It provides an in-depth analysis of the integration of game-like elements within the system, aiming to significantly boost user engagement and participation. This section examines a variety of transcription methodologies, alongside the implementation of reward systems and scoring mechanisms, highlighting the crucial roles of competition and collaboration among users. Finally,

Section 5 discusses reflections and outlines future directions, underscoring the critical need for ongoing observation and adaptation of the platform to align with evolving user requirements and enhance its efficacy.

3. The University Museum System at UniGe (SMA-UniGe)

3.1. Methodology & Goals

The SMA-UniGe project arises from the need to consolidate the extensive cultural heritage of UniGe into a single repository and make it readily accessible online through a user-friendly interface and an engagement system specifically designed for this purpose. The primary goal was to capture, using high-performance 2D and 3D scanners, images of each individual page of ancient tomes, manuscripts, postcards, labels, cartography, and even exam papers, ensuring their high-definition presentation to all individuals interested in participating in their digitization process or those who simply wish to remotely browse through them. The census of these documents was completed in July 2021, resulting in a significant amount of documents that need to be digitized and categorised to prevent them from being lost or scattered. The mission of the project is evident: to make the cultural heritage of the Genoa University discoverable, understandable, and accessible to individuals worldwide. By doing so, researchers, students, professors, and enthusiasts will have the entire archive of UniGe’s cultural heritage at their fingertips with a simple click, regardless of their location.

The transcription of scanned documents will be carried out by the so-called “digital volunteers”. A digital volunteer can be anyone, from a university professor to a student, from an enthusiast to a curious individual. They will be the driving force behind the transcription process and are the ones who, out of experience, passion, or simply for fun, dedicate their time to deciphering each individual character that composes the works in the archive. Digital volunteers resemble the role of paid solvers of CAPTCHAs (Completely Automated Public Turing test to tell Computers and Humans Apart) [

18]. CAPTCHAs are sequences of distorted letters and numbers often displayed in a confusing background and are typically encountered at the end of online registrations or used as a Turing test to confirm one’s human nature and keep malicious bots at bay. Similarly, digital volunteers use their free time to decipher the often complex and challenging documents presented on the platform. However, their motivations are different from simply seeking monetary gain. In fact, in the SMA-UniGe, there is no monetary reward. However, engagement is fuelled by a gamification system that includes an immersive setting, various gameplay modes, as well as interaction with other volunteers. This system also allows volunteers to earn experience points and receive rewards from affiliated organizations.

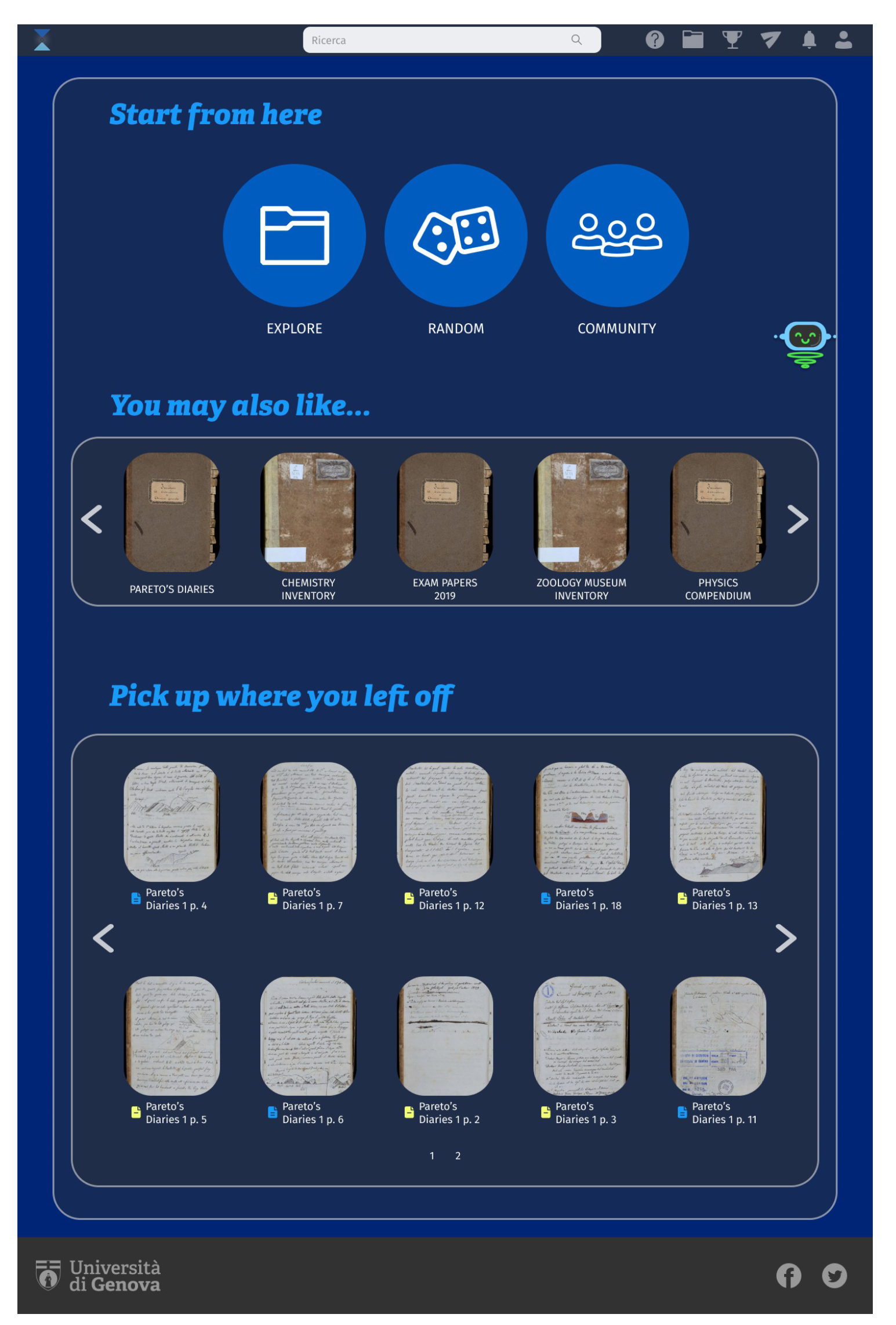

Figure 1.

Homepageafter login.

Figure 1.

Homepageafter login.

Gamification is the process of transforming a non-game activity by incorporating game elements and game design techniques to make it more captivating, thereby stimulating cognitive processes associated with satisfaction and providing an additional positive impetus for accomplishing that activity [

19]. The ultimate aim of gamification is not to create an immensely complex triple-A title, but rather to devise effective methods that enhance individual motivation in both work and personal daily objectives [

20,

21]. Gamification prompts individuals to improve their online and offline behaviours through the utilization of game mechanics that ensure a constant state of engagement. By actively engaging the user, the experience becomes closely linked to the message being conveyed, resulting in enhanced comprehension. Gamification offers benefits such as enhancing communication, collaboration, and creative skills while stimulating learning, motivation, and user interest in an enjoyable, competitive, and simplified manner [

22].

The design of our gamified platform is based on the MDA framework created by Hunicke et al. [

23]. The MDA framework consists of three components: Mechanics, Dynamics, and Aesthetics. Mechanics refers to the game’s specific components and algorithms. Dynamics describes how these mechanics interact and behave in real-time. Aesthetics focuses on eliciting desired emotional responses from players when they engage with the game. The framework emphasizes that games are designed artifacts, with behaviour and interaction being more important than the media presented to the player. This perspective supports clear design choices and analysis throughout the development process. The platform’s design aimed to take into account both the selected objectives for the platform itself and the intrinsic motivations of the users. It sought to choose the most suitable mechanics based on the needs and motivations of the end-users, offering a flexible structure for the experience, allowing users to personalize their journey according to their specific requirements [

24].

In order to study the different personas that could potentially interact with our gamified platform and predict how they would engage with it, we analysed various player types. According to Richard Bartle [

25], players can be categorized into four distinct profiles:

Achiever: This player embarks on gaming experiences with the goal of obtaining all possible badges and achievements, which they proudly showcase on their dashboard.

Explorer: The explorer is drawn to the world presented to them and enjoys the thrill of uncovering secrets and Easter eggs, finding fulfilment in the discovery of new experiences.

Socializer: The socializer prioritizes collaboration and socialization, dedicating less attention to competition. Their primary objective is to connect and engage with others.

Killer: Similar to achievers, killers find gratification in acquiring badges and achievements. However, what sets them apart is their intense competitiveness and the subsequent satisfaction derived from seeing others lose.

The conducted analysis served the purpose of selecting the most effective mechanics and internal rules within the platform to achieve the goal of making the potentially tedious experience of transcription engaging. By understanding the different player types, we aimed to incorporate game elements that would cater to each user’s motivational needs. The objective is to prevent premature abandonment of the platform by ensuring that users find mechanics that align with their individual preferences, thereby making the offered content more appealing. However, the assistance of all digital volunteers is crucial to maximize the addition of as many documents as possible. Therefore, it is important for each individual to feel active and satisfied in their contribution, so that the cultural heritage of UniGe can be continuously enriched with new and available content day by day.

3.2. The Target

The target audience for which the experience is intended is very broad and, in particular, includes curious people, experts in a specific field of work, study or research and students of secondary schools undertaking transversal skills and orientation path (“PCTO”, “Percorsi per le Competenze Trasversali e l’Orientamento”, in Italian). For this reason it was decided to create three user profiles. The first two can be selected during the sign-in process while the last can be obtained after interacting for a certain time within the platform:

“Curious” user: the curious user has the possibility to browse, transcribe, review, earn experience points and badges and manage his dashboard independently via favorite topics selected during registration or elaborated based on his search preferences.

“PCTO” user: the profile is reserved for students who have undertaken the Transversal Skills and Orientation Path and it is linked directly to the young user’s school email address. This type of profile has a personalized user experience to allow the student to complete the tasks required by the PCTO activity. In fact, the student must complete some tasks shown in his dashboard previously selected by the tutor professor who will see the work done once it is finished. Depending on the amount of time expected from the PCTO activity, the state of progress - and therefore the time spent active on the platform - will be considered based on the level reached within the game system. Once the PCTO period has ended, the student will be able to request, via a specific button in the account settings, to change it to a “Curious” user.

“Expert” user: as soon as the user reaches level 20, the account is upgraded to “Expert” status. The “Expert” user has gained the trust of the community and, therefore, can review a transcript and mark it as "complete" without the intervention of a moderator.

3.3. The Environment

To immerse the digital volunteer in a hi-tech environment and with the aim of maintaining the visual identity of the University of Genoa, a color palette has been chosen and it includes two of the primary colors of University’s corporate identity: “Blu UniGe” (HEX: 002677) and light blue (HEX: 199BFC). To these two main colors, a gray for written texts (HEX: 333333), a contrasting blue (HEX: 005DBF), and a neon green (HEX: 48E55A) for links and hover state activation for some clickable elements on the screen have been added (

Figure 2).

The homepage after logging in (

Figure 1) is structured to allow the user to reach all the pages of interest for the transcription and the features inserted to appreciate the experience. The page is designed with a central layout and is divided into three main sections:

Additionally, it features a navbar that provides access to the search bar, instructions, archive, rankings, messages, notifications, and the user’s profile (

Figure 3).

4. Proposed Gamification Strategies

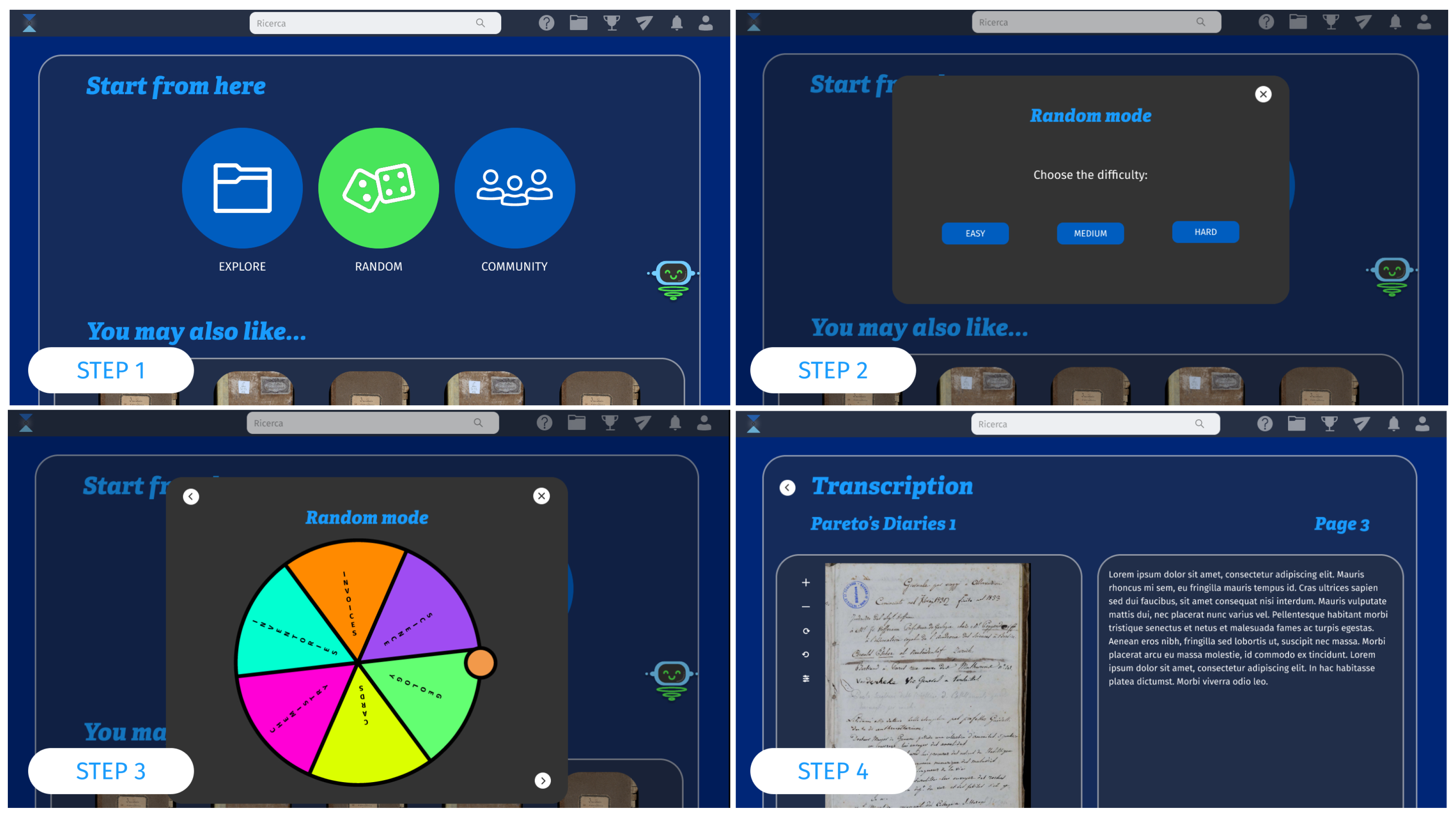

Once logged into the platform, the player will have the option to choose a document to transcribe in three different modes through the “Classic Mode”. The first mode is through a search bar located on the homepage, where suggested documents based on user-entered keywords will be displayed. The second mode is accessed via a dedicated button positioned in the centre of the homepage, which leads to the catalogue page equipped with a search bar and filters. The content can be filtered by “category”, “difficulty”, and “document conditions”. Lastly, there will be a section dedicated to recommended documents within the homepage. However, to cater to the needs of Explorers, a “Random Mode” has been devised, allowing the player to engage in transcribing a random document (

Figure 4). The player will need to select a difficulty level from “Easy”, “Medium”, or “Hard” to initiate a “Wheel of Fortune Game” [

26] containing all the categorized document categories. When the wheel stops, it will randomly and automatically open a document for transcription from scratch or one that has been started by another user but remains unfinished, encouraging the player to try their luck with a psychological mechanism of information-seeking similar to the famous Google’s “I’m Feeling Lucky” button [

27].

The Achievers will derive their satisfaction within the experience by collecting and acquiring rewards such as badges, experience points, and items, while the Killers strive to achieve higher rankings compared to other users. Therefore, various collectible items have been selected, based on the actions undertaken by the players. Players can earn badges within the platform, which will be displayed on their profiles. Badges are unlocked upon the completion of specific tasks indicated by the platform through special missions or upon reaching a certain level or ranking. The requirements for obtaining each badge are clearly stated, enhancing the player’s sense of autonomy and satisfaction by increasing positive feelings [

28]. Additionally, obtaining all available badges to showcase to other players serves as an extra incentive that can influence player behavior, particularly among achievers who are motivated to earn them all [

29]. The inclusion of challenges within gamification, for instance, those that must be completed to earn badges, along with a user-centered design, enhances user performance [

30].

The primary form of rewards is experience points, and a level advancement system has been devised for them, following the Fibonacci sequence in the hundreds. Each number in the Fibonacci sequence is generated by adding the two preceding numbers. By assigning appropriate values to the first two numbers, the entire sequence can be defined. This recursive formula ensures that each term in the sequence relies on or “recurs” the values of the previous terms, specifically the last two numbers. The Fibonacci sequence is often denoted by the symbol F(n), where n represents any natural number, and F(n) represents the corresponding number in the Fibonacci sequence [

31].

This means that reaching level 1 will require earning 100 experience points, progressing from level 1 to level 2 will require an additional 100 experience points, and advancing from level 2 to level 3 will require 200 points, and so on, as outlined in

Table 1.

The presence of a significantly high maximum level, which entails a substantial increase in experience points, serves as a strong incentive for achievers and killers to persist in their transcription efforts [

32]. It caters to their ambitions of collecting badges, attaining higher levels, and competing with fellow users. Moreover, this gradual levelling system enables long-term engagement with the platform, fostering an increasingly immersive experience. Experience points within the platform can be earned through three actions:

1. Document transcription: each character, including spaces, is equivalent to 2 experience points, which are immediately credited upon saving. However, the content may undergo verification by other users capable of reviewing it for adherence to the original text.

2. Revision: each reviewed character of a transcribed document is worth 0.5 experience points during the revision process, which are earned upon validation of the review.

3. Daily logins: by accessing the platform for five consecutive days, experience points are awarded according to the guidelines outlined in

Table 2. The consecutive day count resets after the five-day period.

The acquisition of experience points can be expedited through the presence of the 2x Boost. The 2x Boost is a condition that, when triggered, doubles the recently acquired or yet to be acquired experience points. Specifically, this enhancement occurs in two circumstances. The first circumstance occurs when a document transcription is completed and saved as “Ready for Review.” This triggers a 2x Boost, effectively doubling the experience points just obtained, making longer documents significantly more rewarding. The second circumstance arises when reaching two thousand typed characters within a single session. This situation activates a 2x Boost that doubles the value of all characters from the two-thousand-and-first character onward, even if they are typed in another document. It’s important to note that the boost is only applicable during the current session and will be nullified upon logging out.

The documents on the platform will be categorized into different completion statuses that users can easily understand through a color-coded system. Specifically, the documents can have the following states (

Figure 5):

1. Not Started: A document present in the archive that has not yet been transcribed. The document icon will be displayed in grey.

2. In Progress: When a digital volunteer starts transcribing a document but does not complete it, saving only the work done up to that point, the icon on the main page will appear in yellow.

3. Pending Review: Once the transcription is completed, the digital volunteer can confirm their work by clicking the “Ready for Review” button. In this case, the icon will change to blue, indicating that another volunteer is needed to perform the review.

4. Reviewed: Anyone has the opportunity to review a document, but the contributors’ names are not shown during the review process. Once the review is completed, the icon will turn green.

Social interaction plays a crucial role in fostering engagement within the platform, especially in a voluntary activity [

33]. As a result, we decided to create an environment where digital volunteers can connect, send friend requests, exchange messages in private chats, leave comments in a dedicated section on the document pages, and even form work teams to compete against one another and compare their experience points on a team leaderboard. Players will have the ability to create work groups consisting of their friends, each with a unique team identification code. The group leader will choose a name for the team, which will be displayed as an abbreviation on each member’s profile along with an image uploaded by the creator. Having a team can greatly enhance users’ motivation by fostering a sense of involvement and collaboration through teamwork [

34].

Leaderboards are a crucial tool for engaging and motivating users, fostering competitiveness, and inspiring them to strive for higher rankings [

35]. The leaderboards will be based on the results achieved in single player, displaying the names of individual users alongside their respective counts of badges and transcribed characters, and team mode, showcasing the names of teams along with the cumulative count of badges and transcribed characters achieved by all team members.

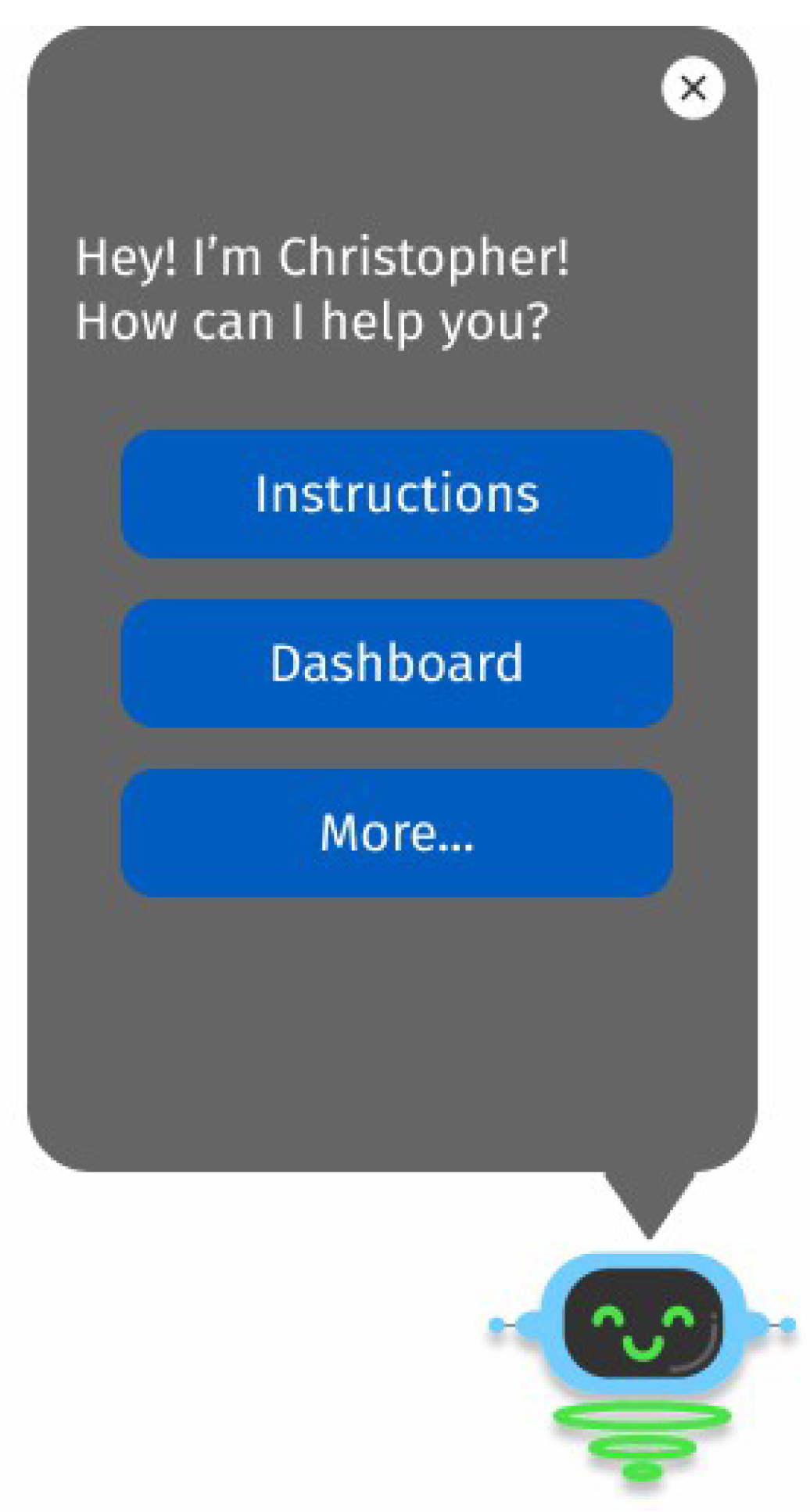

To accompany the digital volunteer on this journey, they will have a companion named Christopher (

Figure 6), a virtual entity who guides the player into the realm of transcription and remains with them throughout the entire experience. Christopher will keep the player informed about updates, and can provide assistance in navigating the platform, if needed. The interaction with the buddy helps the user become acquainted with the environment and develop an emotional connection [

36]. Christopher’s demeanour will vary based on the player’s actions in the game. If the player experiences more defeats, the buddy will become sadder, motivating the player to strive for improvement and avoid disappointing their friend.

5. Conclusions and Future Works

In this paper, we have observed, through the analysis of portals that have already experimented how to engage people in transcription tasks by designing an engagement system with gamification mechanics, how it is possible to create an even more captivating and enjoyable transcription experience for users. Through this innovative dynamic, both curious individuals and experts are actively involved in transcription and data creation, according to the principles of FAIR, Citizen Science, and Open Science. This process will be carried out following clear and detailed instructions, ensuring the regulation of all activities performed on the platform and the assurance that no deviations or issues arise that could compromise the serenity of the community.

To ensure constant evolution and improvement of the platform, the launch of version 1.0 is planned, which will be carefully monitored over time. This will allow for the identification of aspects that are most valued by users during their interaction, in order to make improvements and meet their needs more effectively.

Gamification has demonstrated its ability to enhance people motivation and performance across different academic disciplines and institutional settings, while also improving their analytical and problem-solving skills [

37,

38]. However, it is important to ascertain whether the selected game mechanics result in a superficial and mechanical acquisition of the content included in the transcriptions due to the utilization of inefficient gaming processes for the established objective, or if they lead to an effective assimilation of the produced material [

39]. In fact, one of the aspects that remains to be explored is the practical evaluation of whether the gamified structure implemented can effectively address the needs and motivations of the students. The project’s aim is to keep users engaged while letting them free to choose whether or not to participate in transcriptions, with no tangible rewards other than their ranking position or the acquisition of new badges to display on their profiles. Consequently, it will be necessary to test and, if needed, adapt a structure capable of catering to the individual needs and natural motivations of the players who require it [

40].

An additional possible improvement for achievers could be the opportunity to win University of Genoa merchandise (e.g., T-shirts, sweaters, and water bottles), books of the Genova University Press (GUP), reproductions of UniGe cultural heritage items such as 3D prints of important items or high-quality prints of drawings and documents, discounts or complimentary museum entries, all upon completing short quests. An alternative opportunity can be that of establishing agreements with Museums and Departments that house the manuscripts included in the platform’s database to “open” their archives to digital volunteers for a day, in order to show all the curation work that is undertaken every day behind the scenes. This would allow digital volunteers to discover the value of preserving these cultural assets in a shared experience of enhancement of the University cultural heritage.

Gamification plays a fundamental role in various life contexts and contributes to the establishment of good practices within the community through engaging experiences [

41]. For future projects, it could be interesting to immerse users in a context guided by precise storytelling. This would further enrich the transcription experience by providing an engaging and stimulating narrative framework. Through a compelling plot, users could feel part of an exciting adventure, thereby increasing their motivation and involvement in contributing to data transcription.