Introduction

Paramedicine is a domain of practice and health profession that is enacted using a range of healthcare models including, but not limited to, emergency and primary care. Paramedics provide care in a variety of clinical settings such as paramedic services, hospitals, clinics, and in the community as well as non-clinical roles, such as education, leadership, policy work, public health, and research.[

1] The settings in which paramedics practice and the roles they enact are constantly evolving, which presents challenges when attempting to describe them.

Paramedic practice in Canada was previously described in the 2011 Paramedic Association of Canada (PAC)

National Occupational Competency Profile (NOCP) that outlined the competencies required of a competent paramedic.[

2] The document described 37 general competencies across eight competency areas. The 37 general competencies were supported by 233 specific competencies, which were further supported by over 1300 sub-competencies. Since its publication in 2011, paramedics have expanded their clinical scope of practice, broadened their contexts of practice, and assumed roles and responsibilities reflective of shifting societal needs.[

3,

4] For example, in addition to the ‘traditional’ role that involves treatment and emergency transport to the hospital, paramedics also increasingly provide home-based care through community paramedicine programs [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9], and employ virtual care solutions to expand equitable access to healthcare.[

10,

11] Recent years have prioritized the health and wellbeing of all health care providers internationally, including paramedics [

12,

13], the need to embrace advances in health professions education [

14], and team based care or interprofessional practice.[

15,

16] Given how such advances are under- or mis-represented in the NOCP, the existing description of practice and supporting competencies has become poorly aligned. The NOCP formed the foundation of paramedic education program accreditation; subsequently resulting in poorly aligned education and assessment models that may not adequately prepare learners for the realities of complex professional practice.

Since then, efforts have been made in the Canadian context to offer corrections and better alignment. For example, authors introduced the various roles paramedics might need to adopt to function effectively.[

17] They identified that variable contexts of practice, the need to rethink care as a health and social obligation and the need to organise paramedics and paramedicine within additional team settings were new ways to think about paramedicine. The Canadian Organization of Paramedic Regulators (COPR) also developed a regulator-focused competency framework that describes current responder and paramedic practice in Canada.[

18] However, these efforts were limited in their engagement with the influencing role of context and did not attempt to identify how to respond to the dynamic nature of professional practice. Others have made renewed efforts to provide this needed future-looking perspective. The Paramedic Chiefs of Canada (PCC) identified several new principles to guide the profession at a system level, introducing new ways of thinking about and representing paramedicine, with implications for what this means for paramedics.[

15,

19] Additionally, authors have identified emerging concepts in the paramedicine literature related to shifting societal expectations of health professions.[

3] Finally, recent advances have been made in how best to develop competency frameworks that have shed light on new ways to examine professions[

20] that have not yet been applied in this context. Collectively, this suggested the need to examine the profession in more detail and develop a competency framework that attended to advances and any existing limitations to further describe and ultimately holistically represent paramedic practice in Canada.

Aim

We aimed to develop a competency framework that reflected the needs of contemporary paramedic practice in Canada.

Philosophical and Theoretical Positions

This project was approached from a pragmatic perspective, whereby we considered human experience as the primary means for building knowledge and understanding paramedic practice, as opposed to relying on absolute truths. We used both qualitative and quantitative methodologies and multiple methods of data collection to investigate different components of the project. We were guided by a systems-thinking approach that was founded in third-wave systems thinking, which we next describe as a foundation of our conceptual framework.

Conceptual Framework

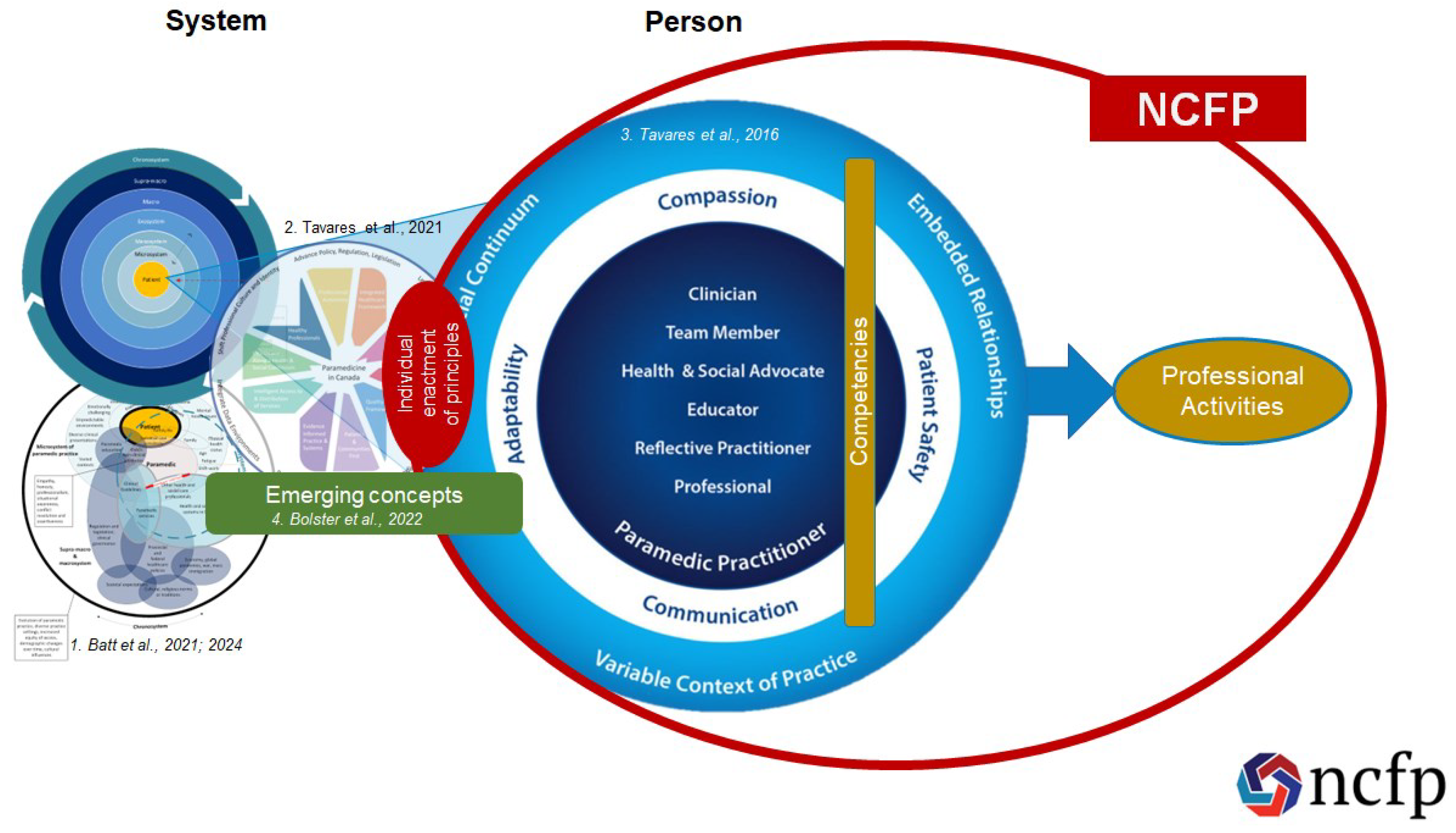

In this project we leveraged existing frameworks to structure a conceptual framework to guide our overall approach. This included merging a novel systems thinking approach[

20] with existing and published Canadian frameworks available at the time. Guided by earlier research that used systems thinking to strengthen the development of competency frameworks[

20], we leveraged earlier work that identified the features of the system of paramedic practice in Canada.[

21] Briefly, that study revealed that paramedic practice considers the person-receiving care, caregivers, and paramedics. It highlighted several issues for us to consider when developing the NCFP including ensuring culturally competent paramedics; engaging meaningfully with Indigenous communities; involving other health and social care professionals, people receiving care, caregivers, and the public; seeking insights from those with contextual expertise; and attending to the variations in regulation, education, funding, and scope of practice across Canada as just some examples.[

21]

We combined the findings of this systems thinking approach with three conceptual models to structure our understanding of the system (place) and the paramedic’s (person) role in it. The first of these publications was the PCC ‘

Principles to Guide the Future of Paramedicine in Canada’.[

15,

19] This framework outlines key issues that paramedicine as a system, and paramedics as individuals need to engage with to improve and evolve practice to meet changing societal needs. These include for example, further integrating with the healthcare system, acknowledging the interaction between health and social needs, and putting patients and their communities first. Some of these principles are systems level concerns, while others can be enacted at both a systems level and an individual level. The second was the PAC ‘

Canadian Paramedic Profile and Roles’.[

17,

22,

23] This framework describes the roles that individual paramedics enact in practice, such as clinician, team-member, and health and social advocate. We structured the ‘

Person’ focus of the NCFP by organising the competencies required to perform professional activities by the roles. Finally, the ‘

Emerging Concepts in the Paramedicine Literature’ review, which outlines key social and societal issues that paramedics must attend to in their practice, such as planetary health, social responsiveness, virtual care, and anti-racism.[

3] As with the principles, some of these concepts are systems level concerns, while others can be enacted at an individual level.

The relationship between these four conceptual elements (systems thinking, principles, profile/roles, and emerging concepts) is outlined in

Figure 1.

Methods

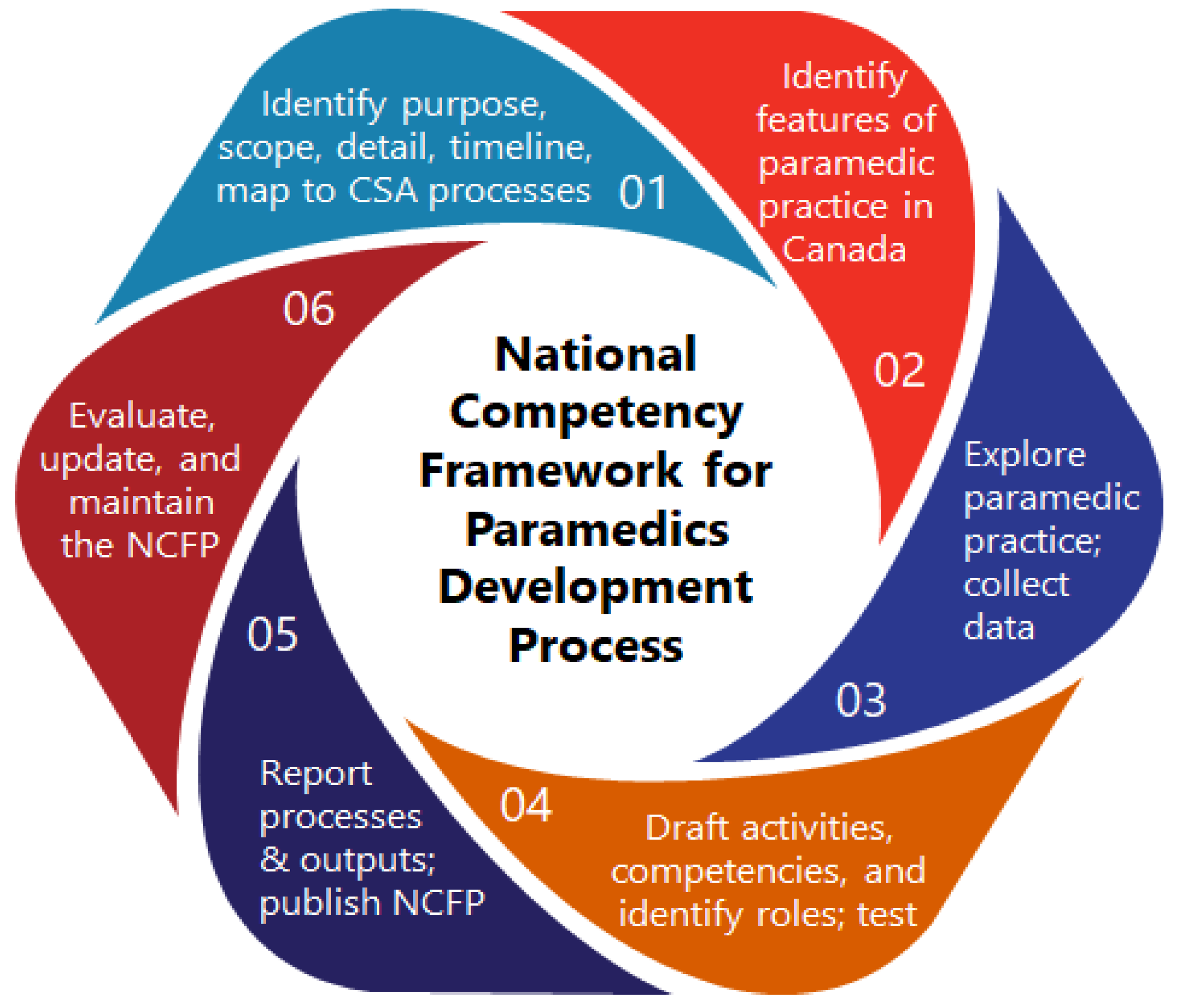

Six-Step Development Model

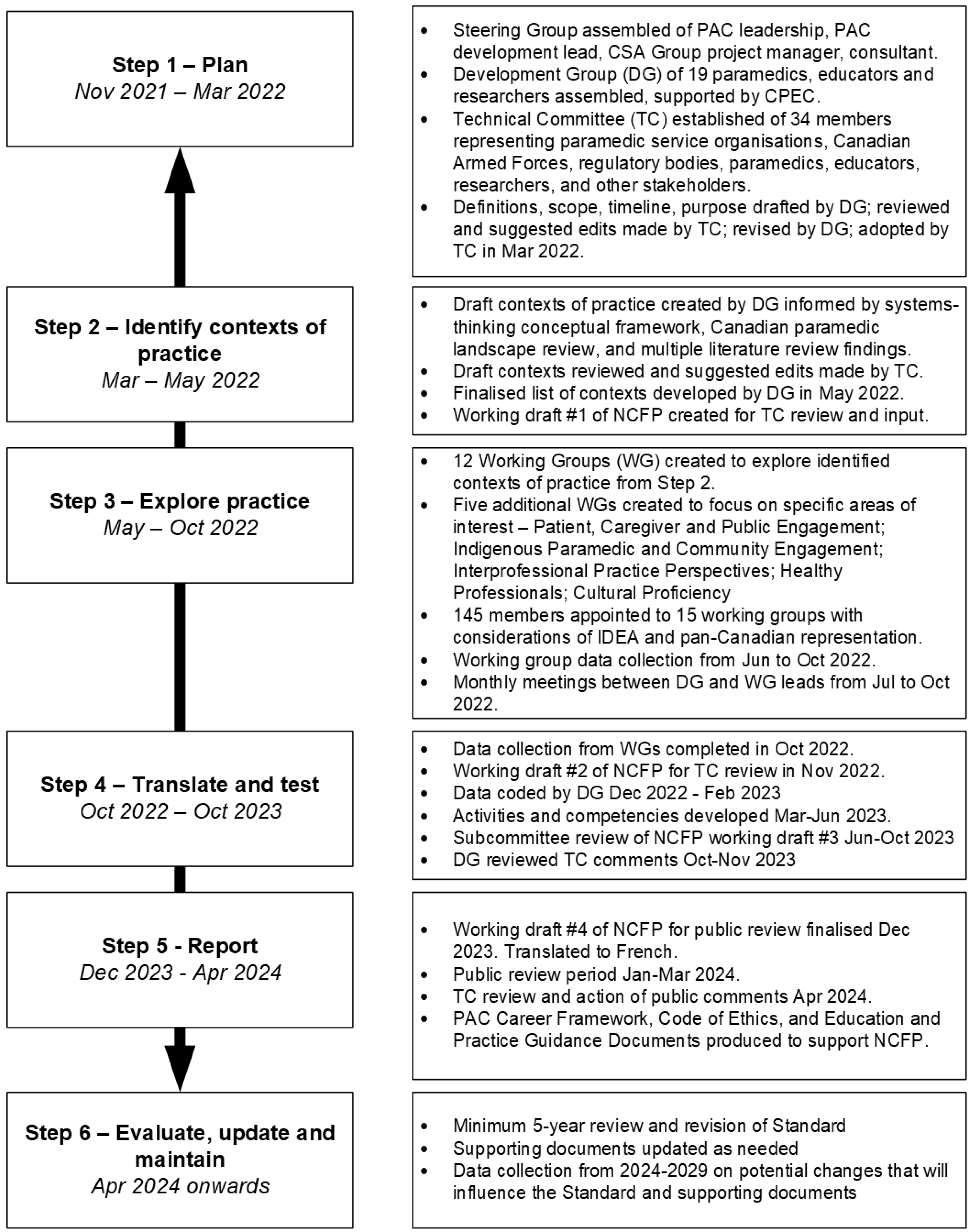

This project used a contemporary six-step model for developing competency frameworks[

24] (see

Figure 2). The model highlights the need for a theoretically informed approach to describing and exploring practice that is appropriate[

20] and offers guidance for developers on reporting the development process and outputs.[

25] Multiple professions have used this model to guide the development of competency frameworks, including occupational health, health research ethics, dietetics, intimate partner violence specialists, and mental health nursing.[

26,

27,

28,

29,

30] The steps include [

1] identifying purpose, intended uses, scope, and stakeholders; [

2] theoretically informed ways of identifying the contexts of complex, “real-world” professional practice, which includes [

3] aligned methods and means by which practice can be explored; [

4] the identification and specification of competencies required for professional practice, [

5] how to report the process and outputs of identifying such competencies, and [

6] built-in strategies to continuously evaluate, update and maintain competency framework development processes and outputs. Next, we describe the people and groups involved in the development process, and then outline each step of the development process in detail.

Stakeholders, Rightsholders, and System Partners

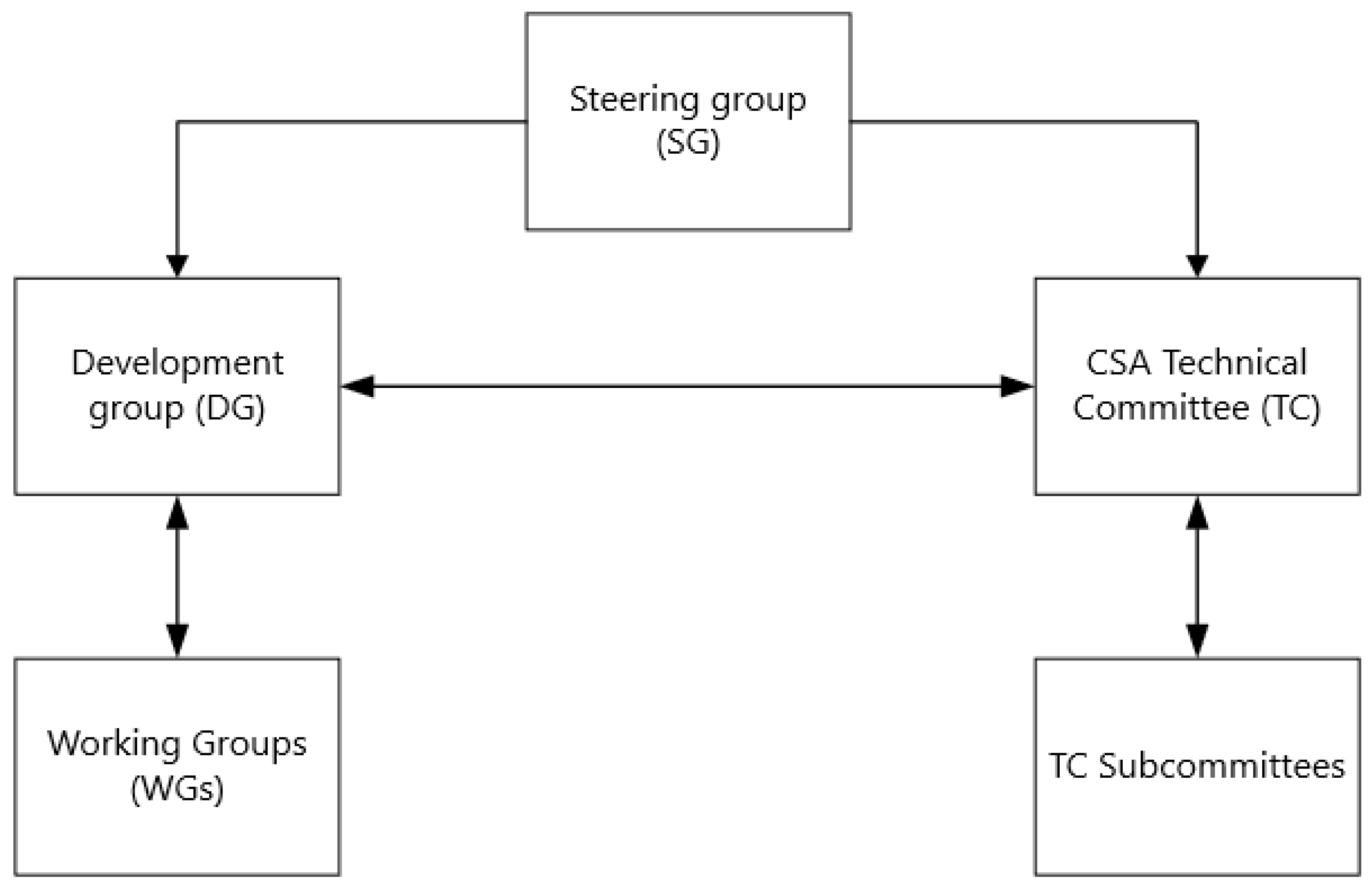

Steering Group

A steering group was convened and comprised of the NCFP Development Lead (AB), the President of PAC, a CSA Group Project Manager, an independent standards consultant, and two officials from PAC - the Director of Standards, Research and Government Relations (PP), and the Chief Operating Officer (DC). This group commissioned and funded the project, provided strategic direction, issued updates to the community, and provided oversight of the development process.

Figure 3 outlines the relationship between the various groups involved in developing the NCFP.

CSA Group Technical Committee

A technical committee (TC) was recruited of 34 members from across Canada, representing diverse sectors of paramedicine (e.g., clinicians, education institutions, service operators, regulators, professional associations, and unions) and those intersecting with or supporting paramedicine (e.g., researchers, accreditation bodies). The group reviewed materials provided and created by the Development Group (DG), suggested edits and comments, approved drafts, and voted on the final version of the standard. Five subcommittees of the TC reviewed each domain of the draft NCFP and reported back to the TC. The TC was chaired by PP.

Development Group

A development group (DG) led the data collection, analysis, and drafting of the competency framework for the NCFP project. The DG lead (AB) recruited members to represent a variety of intersecting clinical practice, education, research, governance, regulatory, policy, leadership, and advocacy experiences within and outside of paramedicine. The DG was composed of 19 individuals from across Canada with experience across multiple contexts of paramedic practice in urban and rural settings, including emergency care, community, military, remote and isolated, critical care, substance use, special operations, interprofessional primary care, and palliative care. They also had experience in regulation, clinical governance, health systems leadership, research, education, policy and strategy, social work, and private industry. Most of the group identified as Canadian, female, and white, had postgraduate qualifications, and resided in Ontario, followed by British Columbia. Several of the group were bilingual (English and French), while the remainder spoke English as their primary language. PM is a member of the Mohawks of the Bay of Quinte First Nation.

This collaborative project was conducted on colonised Indigenous lands now referred to as Canada. These lands are home to the many diverse First Nations, Inuit, and Métis Peoples whose ancestors have stewarded this land since time immemorial. The NCFP was developed with a commitment from the outset of the project to action the

Truth and Reconciliation Commission's Calls to Action[

31], particularly the calls related to health (#18 to 24), and professional development and training for public servants (#57).

Working Groups

Details of working groups (WG) including membership and process are described under Step 2. Individual membership of the various groups is outlined in Supplementary File 1.

Trustworthiness and Rigour

We enacted measures to improve the trustworthiness and rigour of our processes and outputs. We identified the features of the system of paramedic practice in Canada via a robust systems-thinking approach.[

20] This preliminary step ensured the NCFP development process considered the features of contemporary paramedic practice. We engaged members of the profession to provide descriptions of what they do and where they do it without imposing restrictions on how this data was provided. The DG and TC recruited individuals across various sectors of paramedicine (e.g., clinical practice, education, research, leadership, regulation). We ensured a clear audit trail, capturing all documents, codes, activity statements, mapping exercises, and edits throughout multiple drafts. All public facing materials were open-access and archived on the Open Science Framework (OSF). The six-step development model[

24] was mapped to and aligned with the CSA Group’s standard development organisation (SDO) processes.[

32] We engaged people receiving care, care partners, members of the public, members of Indigenous communities, and the broader profession throughout the development process and public review period, through both broad and targeted measures. Finally, we report the development process in accordance with the CONFERD-HP reporting guideline for the development of competency frameworks in health professions.[

25]

Software

We used Google Office Suite for collaborative writing and document management; secure Google Drive folders for cloud storage; Webex, Zoom, and Microsoft Teams for video conferencing; Google Jamboard for interactive whiteboards; Dedoose for qualitative data analysis; Zotero for reference management; and Signal for group messaging. We used Microsoft PowerPoint, Microsoft Visio and miMind to generate presentations, figures, flowcharts, mind maps, and timeline diagrams. We used voicebooking.com to generate the AI voiceover for the conceptual framework video.

Data Stewardship

All public facing materials related to the project were archived via OSF in a publicly available project (

https://osf.io/escxk). The CSA Group maintains a copy of all standards development materials used by the TC, and TC members have continued access to all materials shared on the CSA Communities workspace for this project. All materials and inputs received from Indigenous communities were managed in accordance with OCAP® principles.[

33]

Knowledge Brokering

Core to the development of the NCFP was an ongoing knowledge translation and information sharing strategy. The DG published seven updates from 2022 to 2024 as open access articles in ‘

Canadian Paramedicine’ (a national trade magazine)[

34], which were also uploaded to ResearchGate, OSF, and shared via website posts and social media platforms (LinkedIn, Twitter/X, and Facebook) to keep the paramedic community apprised of the development process. Members of the DG presented the NCFP development process in oral and poster format over 30 times at invited talks, conferences, and workshops across Canada, Australia, Ireland, the UK, and Japan. The DG presented to, and solicited feedback from paramedics, federal and provincial professional associations, leaders of paramedic services, educators, unions, regulators, Indigenous communities, research conference attendees, accreditation groups, other health professions, and paramedic students. This was achieved via direct requests, questions submitted via email, and in-person discussion. The NCFP development lead (AB) met regularly with the consultant leading the COPR regulatory requirements project to share mutual updates. All feedback was memoed and referenced in Steps 3 and 4 when developing professional activities and competencies. A comprehensive public engagement strategy was conducted during the public review period. Full details of the knowledge brokering strategy are outlined in Supplementary File 2.

Ethics Approval

This was a standards development project conducted under the auspices of the CSA Group’s standards development process and thus was not subject to ethics approval. We maintained awareness of the rights of all people who contributed across the project and aimed to ensure equity of representation at every step of the process.

Results—Development Process

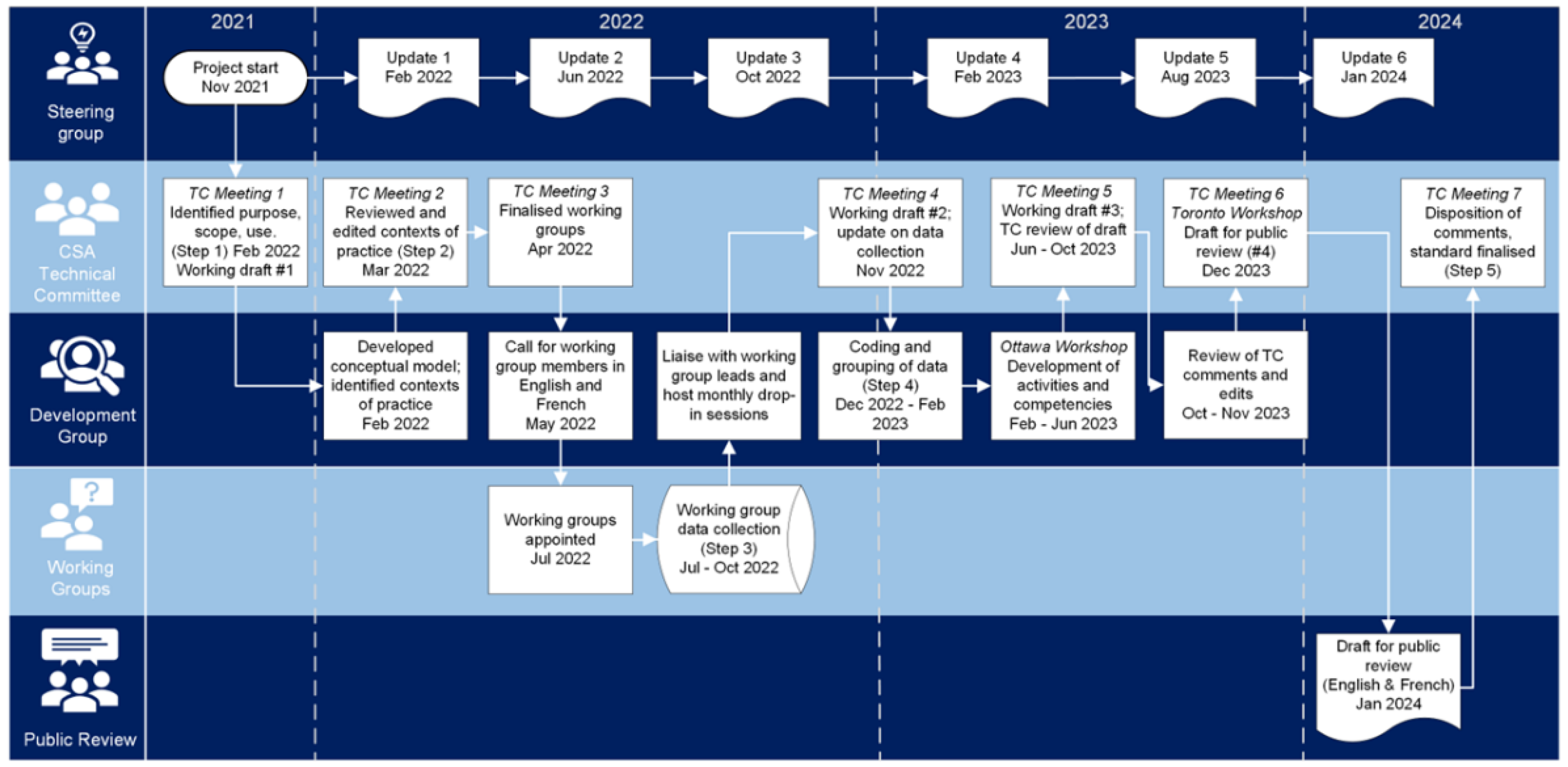

Step 1. Identify Purpose, Scope, Use, and Timeline of the Framework

The SG, DG, and TC collaboratively drafted the purpose, intended uses, terminology, timeline, and scope of the NCFP. The NCFP was intended to describe the professional activities performed by paramedics, and the core competencies required to enact professional, person-oriented practice in diverse contexts. Our aims were not to consider, nor describe competencies related to the Emergency Medical Responder (EMR), service leadership, education, research, policy, or specialist roles that paramedics may fulfil in Canada. Nor did we intend to provide curriculum guidance or career pathway options. EMR competencies are already outlined in the 2015

PAC Emergency Medical Responder Competency Profile[

35], while leadership competencies are addressed via the 2016

PCC Leadership Competency Framework.[

36] The TC considered education, research, and policy competencies out of scope, and recommended that specialist clinical competencies be identified via separate context-specific projects in the future. We elected to describe scope of practice separately to the NCFP, acknowledging that we expect all paramedics in Canada to have the same common competencies which may be enacted in different ways depending on clinical scope, context, and jurisdiction. Scope of practice, education guidance, and ethics will be addressed through the creation of a suite of supporting documents for the NCFP. Working draft #1 of the NCFP was created in February 2022 which described the purpose, scope, and use of the framework. The timeline and workflow of the project as enacted is outlined in

Figure 4, and detail on each step of the development process is provided in

Figure 5. At the end of this step, we had clearly outlined the scope, purpose, and boundaries of the project, which informed the development of the conceptual framework and the identification of the system in Step 2.[

21]

We identified system partners and end-users to be involved during the development of the NCFP. Guided by the findings of Lepre et al[

37], we sought to ensure input from practitioners, academics, employers, regulators, service users, policy makers, other health and social care professionals, and educators. Specific initiatives to seek input from under-represented voices were included at various stages in the process. We elected to structure the NCFP using the concept of professional activities. We define a professional activity for the purpose of this project as

“a synthesis of multiple competencies that requires the integration of knowledge, skills, and attitudes”.[

38] While similar in concept to EPAs, professional activities are not always ‘entrustable’, and are not task driven. We adopted Epstein & Hundert’s definition of competence

“The habitual and judicious use of communication, knowledge, technical skills, clinical reasoning, emotions, values, and reflection in daily practice for the benefit of the individual and the community being served.”[

39] At the end of this step, we had a clear scope, a project plan, interim definitions, a proposed timeline, and a stakeholder engagement plan.

Step 2. Identify Contexts of Paramedic Practice in Canada

We identified contexts of paramedic practice in Canada by using a comprehensive systems-thinking approach, the details of which we published separately.[

21] The contexts of practice were explored in this project through 15 pan-Canadian working groups (WGs) – see

Table 1 for details. The project advertised applications to serve on working groups via email and social media, in both English and French in May 2022, and closed in June 2022. From the 165 applications we received and reviewed, we appointed 154 applicants to 15 working groups. WG members and leads were appointed with considerations of inclusion, diversity, equity, and accessibility (IDEA), and geographical representation across Canada. Members appointed to working groups had expertise with the assigned context of practice, which we defined as

“Practice, research, education, policy, and/or lived or living experience with the context.” Each WG had an identified lead person(s) appointed, along with a liaison person from the DG.

Central to the development of the NCFP was a conscious effort to engage with system partners and end-users with considerations of Indigeneity, cultural proficiency, and IDEA. As such, we established an Indigenous Paramedic and Communities Engagement Working Group, an Interprofessional Perspectives Working Group, a Patient, Caregiver, and Public Engagement Working Group, a Cultural Proficiency Working Group, and a Healthy Professionals Working Group. All working groups represented various intersections of roles, gender, disability, sexual identity, race, ethnicity, age, and other identities.

Indigenous Paramedic and Communities Engagement

An Indigenous paramedic service representative was appointed to the TC to provide a critical strategic perspective, while an Indigenous Paramedic and Communities Engagement working group liaised with Indigenous paramedics and communities from across Canada. This group synthesized the

TRC Calls to Action[

31], the

UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples[

40], the

First Peoples, second class treatment report[

41], the

Final Report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls[

42], and other foundational documents to inform the overall project. In addition, we committed to, undertook, and supported Indigenous community consultations during Step 5.

Patient, Caregiver, and Public Engagement

This working group led the development, implementation and evaluation of a patient, caregiver, and public engagement strategy for the NCFP. Patients, caregivers, and members of the public were engaged at various points during the development process via co-creation and/or consultation. We sought patient and caregiver feedback on the framework during Step 5.

Interprofessional Perspectives

This working group leveraged social media and personal networks to solicit input from nurses, physicians, social workers and other allied health and social care professionals on their perspectives of paramedic work, competencies, and roles using an online survey. This is important because limiting the conceptualisation of paramedic competence to that determined by paramedics may not provide insight into the complexity of healthcare and may fail to address the needs of all those who will use the framework.

Cultural Proficiency

The Cultural Proficiency working group aimed to engage diverse clinicians and experts, and the literature related to the context of culture in paramedic practice across Canada. The group sought to explore health along a health and social continuum and promote enhanced understanding of the implications of intersectionality and social determinants of health on healthcare experiences, health status and outcomes. Recognizing that cultural proficiency is not a static competency, the working group aimed to develop evidence-informed recommendations to inform development of iterative standards to better prepare students for entry to practice in paramedicine and advance the NCFP by including cultural proficiency across all professional domains.

Healthy Professionals

This working group, comprised experts in paramedic wellbeing, professional identity, occupational safety and mental health, developed a framework for wellbeing leveraging subject matter expertise, a review of the relevant peer-reviewed literature, and the extant work developed for the PCC ‘Principles and Enabling Factors Guiding Paramedicine in Canada’ and the COPR ‘Health of Professional’ with the goal to create complementary content so that leaders, regulators, and paramedics would have a shared focus on wellbeing from both systems and person perspectives.

Procedure for Working Groups

We provided each WG lead with guidance on the aim, process, procedures, and anticipated outputs of the working groups. We equipped the WGs with Zoom meeting rooms and secure Google Drive storage for collaborative work and data storage. To ensure safe data storage, we created backups of the Google Drive folders at monthly intervals, storing them on a password-protected hard drive accessible only to the PI (AB). The DG and WG leads held monthly drop-in sessions via Zoom, offering WG leads an opportunity to hear updates and ask questions. Additionally, DG members met with WG leads on an ad-hoc basis on over 40 occasions from June to October 2022. At the end of this step, we had identified contexts of paramedic practice in Canada, issues that required focused attention, and assembled 15 working groups of over 140 paramedics, other health professionals, and Indigenous People to provide expert insight and explore paramedic practice in Canada.

Step 3. Explore Paramedic Practice in Canada

The DG supported working groups in the collection of data from June to October 2022. The working groups faced numerous challenges. For example, some working groups reported a lack of literature and resources to inform their discussions (e.g., Indigenous settings), while others were limited in membership numbers from the outset or due to attrition throughout the lifetime of the WG (e.g., industrial paramedicine). As a result, no standard requirements were placed on data collection methods. Some groups had access to existing competencies (e.g., palliative care[

43]), while many others had no existing competencies to refer to. All groups had access to a review of Canadian paramedicine literature[

3] and a standards roadmap produced as part of another CSA Group and PAC project.[

4] In addition, AB, JB, and ML ensured that WGs were provided with additional resources they requested such as reports or published papers. Outlined in

Table 1 is a brief overview of the methods employed by each WG to generate descriptions of practice to inform the development of the NCFP. The DG developed working draft #2 of the NCFP in November 2022 which detailed the contexts of practice and working group processes. The WGs provided descriptions of practice to the DG in October 2022, and these were combined with feedback on existing competencies from the 2011 NOCP where applicable. AB reviewed and collated the data in Dedoose in November 2022. At the end of this step, we had gathered 34 documents that described paramedic practice across varying contexts in Canada.

Step 4. Translate and Test

Translate Data to Activities and Competencies

Initial coding was performed by AB, JB, and ML in Dedoose from December 2022 to February 2023, using an abductive coding approach. See

Table 2 for details. Inductive coding against the data provided by the working groups ensured the codes represented the data, while deductive coding against existing documents, principles, concepts, and roles ensured the data could be viewed in various ways to inform structure and used to further existing descriptions of practice. A total of 310 codes were applied 3034 times across 34 documents, outlined in Supplementary File 3.

The DG reviewed codes, grouped similar ones, and collapsed them into parent codes during February 2023. They further examined these parent codes in February and March 2023 and identified potential relationships through grouping. In March 2023, members of the DG participated in a two-day intensive in-person workshop. During the workshop, the DG reviewed and used excerpts for codes to draft professional activity statements. The DG then mapped these professional activity statements to predominant roles[

23], principles enacted[

19], and drafted competencies required for each professional activity. We were sensitised to additional competencies that will be required in the near future of paramedic practice based on emerging societal issues and healthcare trends identified in Bolster et al[

3]. Throughout the workshop, AB captured all outputs by DG members and took detailed notes on the process and outputs.

Following the workshop, AB, JB, and ML reviewed the draft items and cross-referenced each professional activity, description, and individual competency with the coded data and workshop notes. This ensured all concepts from the data and DG deliberations had been captured and appropriately represented. In addition, the identified professional activities were cross-referenced for broad alignment with existing frameworks guiding health professionals (e.g., patient safety, interprofessional practice, caregiver support) and the Government of Canada’s Skills for Success framework to guide K-12 education programs.[

46] A full list of the cross-referenced and mapped documents is contained in Supplementary File 3. The DG considered any issues that were not well represented during a comprehensive review and feedback period in May 2023.

Test the Framework for Validity

A competency framework is an instrument that reflects the activities, characteristics, or intentions of a profession. Evaluating a competency framework, like other instruments used to measure activities, should involve investigating reliability, validity, and other properties regarding its application.[

47,

48] If the benefits of a competency framework are recognized by clinicians, educators, researchers, or decision makers, then evaluation and judgement can represent a preliminary step to generate evidence that will later contribute to a validity argument.[

49,

50] Validation has long been described as determining if a framework or instrument does what it is designed to do[

51]. More often, end-users are seeking evidence that supports a framework or instrument being "fit for purpose" when questioning its validity. Validation is not a "one-and-done" process; rather it is the accumulation of multiple pieces of evidence that support the purpose and application of the framework. Initial testing of the NCFP investigated the appropriateness of competencies by exploring practice and generating content validation evidence by examining existing competencies, exploring contemporary practice, and identifying intended uses. This was furthered by using the CSA Group’s standard development process - a rigorous method with broadly recognized credibility. A combination of consensus as the foundation of the process; the use of a balanced matrix to promote fairness; aiming for substantial agreement during consensus; the use of a public review period for feedback; and a clear eight-stage development process supported exploring if the competencies were valued and had perceived utility.

Traditional approaches to establishing ‘validity’ evidence such as a survey of professionals were deemed inappropriate in this project for a few reasons. First, we sought to generate a multitude of sources of evidence[

47] (e.g., via rigorous development process, broad stakeholder engagement, and ongoing feedback and drafting throughout) that contribute to an overall validity argument, in determining whether the NCFP is “fit-for-purpose”. Second, health professionals have been over-burdened with survey requests, particularly since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. This has led to survey fatigue, resulting in drastically reduced response rates (in particular representative response rates), and as a result poor data collection quality.[

52,

53] Collectively, these present a risk to the validity of any results gathered via these means.[

54,

55,

56] Third, the NCFP contains competencies that are supported by evidence as ‘values based’ but not necessarily demonstrated in current practice with broad prevalence. For example, as health professionals, all paramedics

should be enacting the

TRC Calls to Action[

31], even though there may not be strong empirical evidence to support that they are accomplishing these in current practice. Such competencies cannot be meaningfully ‘validated’ via measures of use, importance, and frequency due to their very nature. That does not detract from their necessity as competencies for professional practice. Finally, the mapping of the NCFP to multiple national frameworks adds the varying validity evidence of those individual frameworks to the overall validity argument of the NCFP. The validity argument for the NCFP will be further clarified and strengthened through engagement with and use of the framework leading to ongoing evaluation and maintenance of its utility in practice. At the end of this step, we had drafted the domains of professional activities performed by paramedics in Canada, mapped to the principles, supported by descriptions, and enacted via competencies arranged by role.

Step 5. Report Results of Development (Process) and Findings (Output)

The DG presented working draft #3 of the NCFP to the TC in June 2023. This draft outlined the elements of contemporary paramedic practice in Canada under five proposed domains: person-centred care, collaborative care, safe care, self care, and professional care. The domains were informed by grouping parent codes from Step 4. A total of 27 professional activities were grouped under these domains, and the professional activities were supported by 369 competencies. The TC formed five sub-committees to review each domain of practice and provide detailed feedback on the draft from June to October 2023. Sub-committees were asked to review each professional activity, description, and competency within the working draft for clarity, suitability, and detail. They were also asked to suggest items they considered were missing from the draft. The DG made further revisions to the working draft in November 2023 based on TC subcommittee feedback.

The TC finalised a draft of the NCFP for public review (draft #4) during a two-day hybrid TC meeting in December 2023. During this meeting the TC members reviewed every activity, description, and competency for clarity, granularity, duplication, and language. The revised draft contained 27 activities supported by 323 competencies and was translated to French. The CSA Group conducted a public review period from January 19

th to March 19

th, 2024. During this period, we engaged patient and caregiver groups, Indigenous communities, and marginalised and under-served populations to seek their input and feedback. We achieved this by travelling to Indigenous communities to seek direct feedback and sharing the public review link with partners in patient advocacy, caregiver, and marginalised population groups to review and provide feedback. A full list of individuals and organisations who we shared the request with, and who provided feedback and commentary on the draft is contained in Supplementary File 2. In addition, WT and AB submitted competencies related to paramedics in interprofessional primary care initiatives on behalf of the Team Primary Care funded ‘

IMPACC’ project for review by the TC.[

57] In 2023, the Public Services Health and Safety Association (PSHSA) conducted a stakeholder engagement session with various leaders, educators and paramedics to discuss the healthy and safe longevity of a paramedic’s career. The feedback from this session was also submitted to the TC.

Following the closure of the public review period on March 19th, 2024, the TC considered and actioned 142 public review comments and 14 comments from the PSHSA feedback at a hybrid meeting on April 5th, 2024. This was guided by the CSA Group processes, whereby all comments were collated and discussed in turn for possible action. Actions taken by the TC included accepting proposed changes, reverting comments back to the DG for action, marking the comment as addressed previously in the development process, or rejecting the proposed changes (e.g., out of scope, unclear, irrelevant). All actions were reached via consensus. Following these edits, a mapping exercise was conducted in April 2024 between the NCFP and the COPR competency framework.

At the end of this step, we had developed the NCFP and critically revised it based on broad profession, system partner, and public feedback. The NCFP describes the professional activities of paramedics under five domains (see

Figure 6). A full list of the domains and activities is contained in Supplementary File 4. The detailed competency statements are contained in the CSA Group Standard

Z1660:2024 National Competency Framework for Paramedics, a National Standard of Canada, which will be available to view on the CSA Group website.

Step 6. Evaluate, Update, and Maintain the Framework

The findings of this project serve as an important step in better understanding professional paramedic practice in Canada. The NCFP provides a holistic description on which future contextually bounded advanced practice competencies may be developed. However, this framework must be tested in the coming months and years by diverse users. Future research on the ‘validity’ and utility of the NCFP is needed as described in Step 4, and we consider this to be a living document that will need to change and adapt over time as paramedic practice and societal expectations change. The results of real-world testing must be considered when updating and maintaining this competency framework. Feedback from implementing the framework in different contexts will be key to ensuring it remains applicable, useful, and relevant for the paramedic profession in Canada, now and in the future. We have already started the process of seeking feedback to inform change. For example, we began outreach activities in April 2024, using the Skills for Success mapping to inform discussions with K-12 teachers. In addition, the development of the suite of supporting documents to help with implementing the NCFP is nearing completion, and these will be reported in future publications.

Discussion

We developed a competency framework for paramedics in Canada using a rigorous standards development process that attended to contextual differences, cultural proficiency, and sought input from a wide range of system partners. The NCFP provides a contemporary description of paramedic practice in Canada via 27 professional activities that are organised under five domains of practice.

The description of paramedic practice in Canada that the NCFP offers is different to existing descriptions in several ways. First, the development process was theoretically informed using a systems thinking approach.[

20] Risks of not using theoretically informed approaches include overlooking features of practice, and as a result, producing an output that has some level of face and content validity, but is insufficiently aligned with the realities and complexities of practice.[

20,

58] As examples, efforts are being made across other health professions competency spheres to address the shortcomings of existing frameworks in relation to cultural proficiency, virtual care, and planetary health.[

59,

60,

61,

62] We identified many of these concerns in our initial exploration of the system, which afforded us the opportunity to integrate practice features and their interactions toward an improved and more representative and holistic competency framework.[

21]

Second, the NCFP development via the CSA Group process employed consensus as a foundation of decision-making.[

32] Seeking to produce a document that meets the needs of diverse groups is challenging. To mitigate this, we established a clear frame of reference at the beginning related to the scope of the framework, intended uses and users, and who to engage throughout the development process. This step provided boundaries that supported decision making throughout the project, but flexibility in that decisions could be revisited and discussed. In addition, the overarching guiding principle of co-creation we employed throughout the duration of the project [

63], and the cross-appointment of individuals between the DG, WGs and the TC supported critical discourse and the opportunity for a shared voice to emerge.

We engaged with paramedics, people receiving care, Indigenous communities, and many other health and social care professions to gain descriptions of paramedic practice. This aligns with the contemporary development advice of Lepre et al[

37] and Murray et al[

64] who offer that those developing competency frameworks should seek to engage a variety of system partners including people receiving care, other health professions and the community. Conceptualising paramedic competency as something that is informed or determined by paramedics alone may hinder our ability to see the broader influences on practice from other perspectives.[

37] Remaining focused only on features of current practice or those within the remit of one sector of the broader profession results in a lack of attendance to larger societal influences, and the somewhat predictable evolving needs of paramedics. This may result in features that remain hidden when developing a competency framework, which can result in poor alignment of any such competency framework with the realities of practice expectations.[

20] Research in other professions has highlighted the disconnect between current competency frameworks and evolving societal expectations.[

65,

66,

67,

68] Without engaging with such evolving competencies, we risk maintaining the status-quo and continuing to perpetuate a state whereby professions are poorly prepared to respond to evolving demands based on their static competency descriptions.

Finally, we anchored our development of the NCFP to existing models and descriptions of practice through our conceptual framework. These models become complementary in their enactment over time, whereby advances or insights produced by one can inform the continued evolution of the others. The advances must be thoughtful, and where possible, based on the findings from implementing, using, and evaluating other models. In this spirit, we directly adopted the terminology from the models used in our conceptual framework and will use insights gained from implementing the NCFP to suggest if changes to these models should be considered in the future. As we look forward, we envision a future state of one holistic description of paramedic practice in Canada, one through which the needs of all system partners, and the continued evolution of paramedicine across Canada can be realised.

Reflections on Using the Six-Step Model

This was our second time using the six-step development model, and we offer two critical insights at this point. The first is the importance of a guiding conceptual framework by which to inform decisions within the six-step model. Developing an overall guiding framework on how we conceptualised the role of the NCFP helped to keep the project focused on scope, intended uses, and on the ‘person’ level. The second insight we offer is the need for a clear project management strategy when using the six-step model that operationalises the six steps into actionable items and steps. While a variety of project management techniques and methods could be adopted by those developing competency frameworks, the SDO processes we engaged with through the CSA Group offered a defensible and rigorous project management solution. We offer some guidance by mapping the six-step model to SDO processes and project management fundamentals in Supplementary File 5.

Limitations

The NCFP development process has several limitations that must be acknowledged. Despite our best efforts, we may not have identified all contexts of practice that informed Steps 2 and 3. Similarly, we may have over-sampled what is or should be included. However, given our focus on common elements of practice across multiple contexts, we offer that this would likely not have significantly influenced the final output. Second, we may not have captured the perspectives of all who are affected by this framework. In response, we acknowledge that this document is a living document, and we will seek and encourage broad feedback over the coming years to inform updates to this framework. Third, we did not engage with traditional approaches to “validation” such as a survey of professionals. We articulate our reasoning for this under Step 4, and offer that the continued evolution of practice, and therefore the need to continuously update competency frameworks challenges such traditional approaches. We instead offer a perspective of determining if the framework is “fit-for-purpose”, and the need to evolve how conceptualise and measure ‘validity’ when exploring complex professional practice. Finally, our engagement with those affected by the framework could be further enhanced by moving closer to a true co-creation approach. While we made deliberate efforts to engage with many diverse Indigenous, cultural, and professional voices across Canada, we must acknowledge that we can, and will seek to do better in the future. A future state of a truly co-created competency framework (between the broad profession, the diverse public, and adjacent healthcare professionals) is something we should strive for as health professionals.

Conclusion

The NCFP provides the first theoretically informed, contemporary description of paramedic practice in Canada that acknowledges the importance of practice in context, while identifying common elements of practice. As a result, the NCFP provides a holistic description for professional paramedic practice in all settings, and a foundation on which to develop contextually bounded advanced practice competencies. It places people receiving care at the core of the paramedics’ activities, attends to evolving and emerging societal concerns, and will inform downstream activities such as curriculum, assessment, and regulation, to better prepare paramedics for complex, interprofessional health and social care practice now and in the future.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Supplementary File 1 - Membership of NCFP groups. Supplementary File 2 - Knowledge brokering strategy for NCFP. Supplementary File 3 - List of cross-referenced and source materials. Supplementary File 4 - Domains and professional activities in the NCFP. Supplementary File 5 - Mapping of six-step model and SDO processes. Supplementary File 6 - CONFERD-HP reporting guideline checklist

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: AB, PP. Methodology: AB, WT. Formal analysis: AB, JB, ML, PP, DC, MA, CC, ED, BD, ND, WJ, CL, TL, PM, MO, DS, ST, CV, WT. Data Curation: AB, JB, ML. Writing - Original Draft: AB, JB, ML. Writing - Review & Editing: AB, JB, ML, PP, DC, MA, CC, ED, BD, ND, WJ, CL, MSL, TL, PM, MO, DS, ST, CV, WT. Visualisation: AB. Project administration: AB, JB, ML, PP, DC. Funding acquisition: AB, PP, DC.

Funding

The project was funded by the Paramedic Association of Canada (PAC) and the CSA Group.

Acknowledgments

We wish to gratefully acknowledge the inputs of DG members Jeanne Bank and Rene Lapierre; Ron Meyers, Project Manager, CSA Group; all members of SG, TC, DG and WGs outlined in Supplementary File 1; and all who reviewed and provided feedback during the public review period outlined in Supplementary File 2. OCAP® is a registered trademark of the First Nations Information Governance Centre (FNIGC) – see

https://fnigc.ca/ocap-training/.

Conflicts of Interest

All members of the SG, TC, and DG had to declare any potential conflicts of interest in advance. Members of the TC were reminded of conflicts of interest at the start of each TC meeting as per CSA Group procedures. AB is a former faculty member and research associate at Fanshawe College. He has received funding from CSA Group and PAC for multiple projects. AB, JB, ML were remunerated for their time on this project. Expenses for the DG workshop in Ottawa were covered under the project budget. CL is a faculty member at Fanshawe College. WT and AB received funding from Team Primary Care to develop primary care competencies for paramedics which were submitted to the NCFP project during the public review period. PP and DC are employed by PAC. AB and WT are Deputy Editors of Paramedicine, CC and EAD are Associate Editors of Paramedicine.

References

- Williams, B.; Beovich, B.; Olaussen, A. The Definition of Paramedicine: An International Delphi Study. JMDH 2021, 14, 3561–3570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paramedic Association of Canada. National Occupational Competency Profile; Paramedic Association of Canada: Ottawa, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bolster, J.; Pithia, P.; Batt, A.M. Emerging Concepts in the Paramedicine Literature to Inform the Revision of a Pan-Canadian Competency Framework for Paramedics: A Restricted Review. Cureus. 14. Epub ahead of print 23 December 2022. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batt, A.M.; Bank, J.; Bolster, J. Canadian Paramedic Landscape Review and Standards Roadmap. Toronto: CSA Group, https://www.csagroup.org/article/research/canadian-paramedic-landscape-review-and-standards-roadmap/ (2023, accessed 24 March 2024).

- CSA Group. CAN/CSA Z1630:17 Community paramedicine: Framework for program development. Toronto: CSA Group, 2017.

- Leyenaar, M. Community paramedicine: part of a modern emergency health services system. Canadian Paramedicine 2020, 43, 6–9. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal, G.; Angeles, R.; Pirrie, M.; et al. Reducing 9-1-1 Emergency Medical Service Calls By Implementing A Community Paramedicine Program For Vulnerable Older Adults In Public Housing In Canada: A Multi-Site Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial. Prehospital Emergency Care 2019, 23, 718–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashton, C.; Duffie, D.; Millar, J. Conserving Quality of Life through Community Paramedics. Healthcare quarterly (Toronto, Ont) 2017, 20, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dainty, K.N.; Seaton, M.B.; Drennan, I.R.; et al. Home Visit-Based Community Paramedicine and Its Potential Role in Improving Patient-Centered Primary Care: A Grounded Theory Study and Framework. Health Services Research 2018, 53, 3455–3470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brittain, M.; Michel, C.; Baranowski, L.; et al. Community paramedicine in British Columbia: A virtual response to COVID-19. Australasian Journal of Paramedicine 2020, 17, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renfrew County Virtual Triage and Assessment Centre. Renfrew County Virtual Triage and Assessment Centre marks one year since it launched as a pandemic healthcare service, https://rcvtac.ca/pluginfile.php/672/course/section/71/VTAC%20anniversary_MediaRelease_Mar262021.pdf (2021, accessed 2 July 2021).

- CSA Group. CSA Z1003.1:18 (R2022) Psychological health and safety in the paramedic service organization. Toronto: CSA Group, 2018.

- Nundy, S.; Cooper, L.A.; Mate, K.S. The Quintuple Aim for Health Care Improvement: A New Imperative to Advance Health Equity. JAMA 2022, 327, 521–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavares, W. Paramedicine education: Navigating moments for transformation through research. Paramedicine 2024, 27536386241232670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, W.; Allana, A.; Beaune, L.; et al. Principles to Guide the Future of Paramedicine in Canada. Prehospital Emergency Care 2021, 0, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lingard, L. Rethinking competence in the context of teamwork. In The Question of Competence; Hodges, B.D., Lingard, L., Eds.; Cornell University Press: New York, NY, US, 2012; pp. 42–70. [Google Scholar]

- Tavares, W.; Bowles, R.; Donelon, B. Informing a Canadian paramedic profile: framing concepts, roles and crosscutting themes. BMC Health Serv Res 2016, 16, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canadian Organization of Paramedic Regulators. Pan-Canadian Essential Regulatory Requirements (PERRs) for Paramedics, https://copr.ca/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/PERRS_Introduction_ENG_2023_10_31.pdf (2023, accessed 26 March 2024).

- Tavares, W.; Allana, A.; Weiss, D. Principles and Enabling Factors Guiding Paramedicine in Canada. Ottawa: Paramedic Chiefs of Canada, https://www.paramedicchiefs.ca/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/PCC-Full-Report-with-TTPS-FRexecsumm.pdf (2023, accessed 21 January 2024).

- Batt, A.M.; Williams, B.; Brydges, M. New ways of seeing: supplementing existing competency framework development guidelines with systems thinking. Advances in Health Sciences Education. Epub ahead of print 18 May 2021. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batt, A.M.; Lysko, M.; Bolster, J.L. Identifying Features of a System of Practice to Inform a Contemporary Competency Framework for Paramedics in Canada. Epub ahead of print 26 March 2024. [CrossRef]

- Bowles, R.R.; van Beet, C.; Anderson, G.S. Four dimensions of paramedic practice in Canada: Defining and describing the profession. Australasian Journal of Paramedicine, 14. Epub ahead of print 2017. [CrossRef]

- Paramedic Association of Canada. Canadian Paramedic Profile: Paramedic Roles; Paramedic Association of Canada: Ottawa, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Batt, A.; Williams, B.; Rich, J.; et al. A Six-Step Model for Developing Competency Frameworks in the Healthcare Professions. Frontiers in Medicine 2021, 8, 2601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batt, A.M.; Tavares, W.; Horsley, T.; et al. CONFERD-HP: recommendations for reporting COmpeteNcy FramEwoRk Development in health professions. British Journal of Surgery 2023, 110, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, L.M.; Palermo, C. Using document analysis to revise competency frameworks: Perspectives from the revision of competency standards for dietitians. Front Med, 9. Epub ahead of print 4 August 2022. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhao, J.; Chen, Y. Construction of a Competency Model for Occupational Health Post for Chinese Medical Students. Epub ahead of print 28 March 2024. [CrossRef]

- Lau, Y. Working with Domestic Abuse: A Competency Framework for Psychological Professionals, https://pure.royalholloway.ac.uk/en/publications/working-with-domestic-abuse-a-competency-framework-for-psychologi (2023, accessed 28 March 2024).

- Maguire, T.; Willetts, G.; McKenna, B.; et al. Developing entrustable professional activities to enhance application of an aggression prevention protocol. Nurse Education in Practice 2023, 73, 103827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, K.L.; Baker, L.; Jenney, A.; et al. Voices of Experience: Development of the Flourishing Practice Model of Capabilities of Intimate Partner Violence Specialists. J Fam Viol 2023, 38, 1151–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truth and Reconcilliation Commission of Canada. Honouring the truth, reconciling for the future: summary of the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada., http://epe.lac-bac.gc.ca/100/201/301/weekly_acquisition_lists/2015/w15-24-F-E.html/collections/collection_2015/trc/IR4-7-2015-eng.pdf (2015, accessed 30 March 2021).

- CSA Group. CSA Group Standard Development Stages-Fact Sheet, http://d1lbt4ns9xine0.cloudfront.net/csa_core/ccurl-zip/958/302/CSAGroup-StandardDevelopmentStages-FactSheet.pdf (accessed 25 March 2024).

- The First Nations Principles of OCAP®. The First Nations Information Governance Centre, https://fnigc.ca/ocap-training/ (accessed 26 March 2024).

- Batt, A.; Poirier, P.; Bank, J.; et al. Developing the National Occupational Standard for Paramedics in Canada – update 3. Canadian Paramedicine 2022, 45, 6–8. [Google Scholar]

- Paramedic Association of Canada. Emergency Medical Responder Competency Profile; Paramedic Association of Canada: Ottawa, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Thain, N.; Heinrich, C.; Rodier, P. Leadership Competency Framework; Paramedic Chiefs of Canada: Ottawa, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lepre, B.; Palermo, C.; Mansfield, K.J.; et al. Stakeholder Engagement in Competency Framework Development in Health Professions: A Systematic Review. Frontiers in Medicine 2021, 8, 2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pangaro, L.; ten Cate, O. Frameworks for learner assessment in medicine: AMEE Guide No. 78. Med Teach 2013, 35, e1197–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epstein, R.M.; Hundert, E.M. Defining and assessing professional competence. JAMA 2002, 287, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations. United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

- Allan, B.; Smylie, J. First Peoples, second class treatment; Wellesley Institute, 2015; pp. 1–65. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Canada. Reclaiming Power and Place: The Final Report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, http://archive.org/details/mmiwg-ffada.cafinal-report (2019, accessed 6 April 2024).

- Cameron, C.; Sullivan, J.; Graham, A.; et al. The Canadian Paramedic Competency Profile for the Provision of Palliative and End of Life Care: Time for a Change? Canadian Paramedicine 2016, 39, 15–18. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Interprofessional Health Collaborative. A National Interprofessional Competency Framework. Vancouver, British Columbia: Canadian Interprofessional Health Collaborative, https://drive.google.com/file/d/1Des_mznc7Rr8stsEhHxl8XMjgiYWzRIn/view?usp=sharing&usp=embed_facebook (2010, accessed 28 February 2024).

- Parmar, J. Competency Framework — Caregiver Centered Care. University of Alberta, https://www.caregivercare.ca/competency-framework (2021, accessed 28 February 2024).

- Government of Canada. The new Skills for Success model, https://www.canada.ca/en/services/jobs/training/initiatives/skills-success/new-model.html (2021, accessed 28 February 2024).

- Cook, D.A.; Brydges, R.; Ginsburg, S.; et al. A contemporary approach to validity arguments: A practical guide to Kane’s framework. Medical Education 2015, 49, 560–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, M.T. Validation as a Pragmatic, Scientific Activity. Journal of Educational Measurement 2013, 50, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearney, M.H. Under-Appreciated Steps in Instrument Development, Part I: Starting With Validity. Research in Nursing & Health 2016, 39, 81–83. [Google Scholar]

- Kane, M.T. Current Concerns in Validity Theory. Journal of Educational Measurement 2001, 38, 319–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, P.; Fitzsimons, C.; Baker, G. Should we reframe how we think about physical activity and sedentary behaviour measurement? Validity and reliability reconsidered. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2016, 13, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Koning, R.; Egiz, A.; Kotecha, J. Survey Fatigue During the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Analysis of Neurosurgery Survey Response Rates. Frontiers in Surgery; 8, https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fsurg.2021.690680 (2021, accessed 28 February 2024).

- Gnanapragasam, S.N.; Hodson, A.; Smith, L.E.; et al. COVID-19 survey burden for health care workers: literature review and audit. Public Health 2022, 206, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morton, S.M.B.; Bandara, D.K.; Robinson, E.M.; et al. In the 21st Century, what is an acceptable response rate? Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health 2012, 36, 106–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, A.B.; Brooks, W.S.; Edwards, D.N.; et al. Survey response rates in health sciences education research: A 10-year meta-analysis. Anatomical Sciences Education 2024, 17, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.; Sagar, R. A critical look at online survey or questionnaire-based research studies during COVID-19. Asian Journal of Psychiatry 2021, 65, 102850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Team Primary Care. Paramedicine as Part of Interprofessional Primary Care Teams.pdf, 2023. https://www.dropbox.com/s/htxphbc4ucga87z/TPC%20-%20Paramedicine%20-%20Paramedicine%20as%20Part%20of%20Interprofessional%20Primary%20Care%20Teams.pdf?dl=0 (accessed 25 March 2024).

- Batt, A.M.; Tavares, W.; Williams, B. The development of competency frameworks in healthcare professions: a scoping review. Advances in Health Sciences Education 2020, 25, 913–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnabe, C.; Osei-Tutu, K.; Maniate, J.M. Equity, diversity, inclusion, and social justice in CanMEDS 2025. Canadian Medical Education Journal. Epub ahead of print 3 February 2023. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, S.; Labine, N.; Luo, O.D. Planetary Health in CanMEDS 2025. Canadian Medical Education Journal. Epub ahead of print 3 October 2022. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osei-Tutu, K.; Duchesne, N.; Barnabe, C. Anti-racism in CanMEDS 2025. Canadian Medical Education Journal. Epub ahead of print 6 February 2023. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stovel, R.G.; Dubois, D.; Chan, T.M. Virtual Care in CanMEDS 2025. Canadian Medical Education Journal. Epub ahead of print 26 September 2022. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vargas, C.; Whelan, J.; Brimblecombe, J. Co-creation, co-design, co-production for public health: a perspective on definition and distinctions. Public Health Research & Practice 2022, 32. Available online: https://apo.org.au/node/318244 (accessed on 28 March 2024).

- Murray, N.; Palermo, C.; Batt, A. Does patient and public involvement influence the development of competency frameworks for the health professions? A systematic review. Frontiers in Medicine 2022, 9. Available online: https://wwwfrontiersinorg/articles/103389/fmed2022918915 (accessed on 8 November 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osei-Tutu, K.; Ereyi-Osas, W.; Sivananthajothy, P. Antiracism as a foundational competency: reimagining CanMEDS through an antiracist lens. CMAJ 2022, 194, E1691–E1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jagals, P.; Ebi, K. Core Competencies for Health Workers to Deal with Climate and Environmental Change. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18, 3849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salhi, B.A.; Tsai, J.W.; Druck, J. Toward Structural Competency in Emergency Medical Education. AEM Education and Training. 4. Epub ahead of print February 2020. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dagnone, J.D.; Glover Takahashi, S.; Whitehead, C.; et al. Reclaiming physician identity: It’s time to integrate ‘Doctor as Person’ into the CanMEDS framework. Canadian Medical Education Journal 2020, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).