Submitted:

09 April 2024

Posted:

10 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Sample

2.3. Study Variables

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Data Analysis

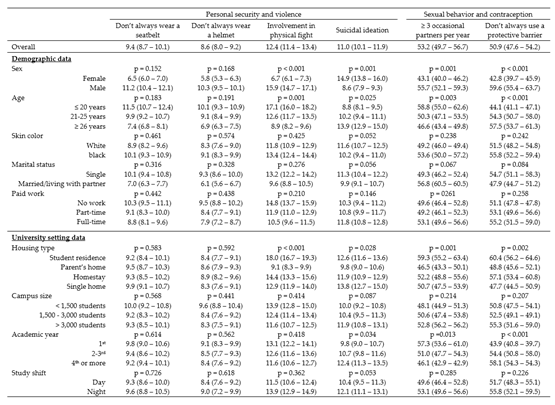

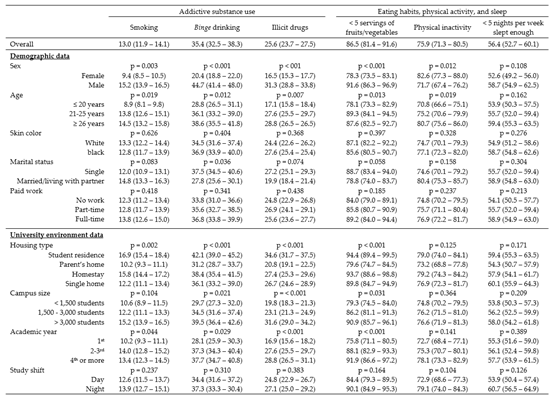

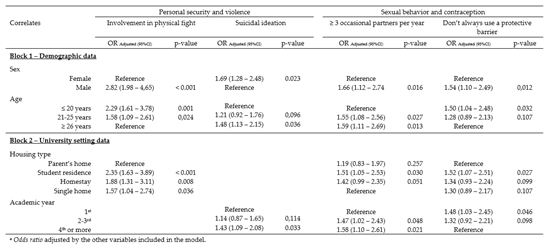

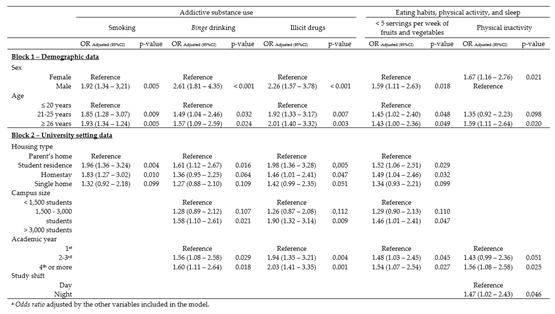

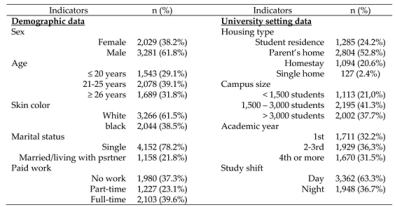

3. Results

|

|

|

|

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zimmermann, M.; O’Donohue, W.; Vechiu, C. A Primary Care Prevention System for Behavioral Health: The Behavioral Health Annual Wellness Checkup. J Clin Psychol Med Settings 2020, 27, 268–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO – World Health Organization. World Health Statistics 2018: Monitoring Health for the SDGs, Sustainable Development Goals. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2018.

- Beaudry, K.M.; Ludwa, I.A.; Thomas, A.M.; Ward, W.E.; Falk, B.; Josse, A.R. First-year university is associated with greater body weight, body composition and adverse dietary changes in males than females. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0218554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, J.; Baber, M.; Byrom, N. , Meade, L.; Nouri, K. Changes in student physical health behaviour: an opportunity to turn the concept of a Healthy University into a reality. Perspect Public Health 2018, 138, 316–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Ansari, W.; Ssewanyana, D.; Stock, C. Behavioral health risk profiles of undergraduate university students in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland: A cluster analysis. Front Public Health 2018, 6, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, J.J.; MacDonncha, C.; Murphy, M.H.; Murphy, N.; Timperio, A.; Leech, R.M.; et al. Identification of health-related behavioural clusters and their association with demographic characteristics in Irish university students. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peltzer, K.; Pengpid, S.; Mohan, K. Prevalence of health behaviors and their associated factors among a sample of university students in India. Int J Adolesc Med. Health 2014, 26, 531–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shekari, F.; Habibi, P.; Nadrian, H.; Mohammadpoorasl, A. Health-risk behaviors among Iranian university students, 2019: A web-based survey. Arch Public Health 2020, 78, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ansari, W.E.; Khalil, K.A.; Ssewanyana, D.; Stock, C. Behavioral risk factor clusters among university students at nine universities in Libya. AIMS Public Health 2018, 5, 296–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amiri, M.; Raei, M.; Sadeghi, E.; Keikavoosi-Arani, L.; Khosravi, A. Health-promoting lifestyle and its determining factors among students of public and private universities in Iran. J Educ Health Promot 2023, 12, 239. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Caballero, L.G.R.; Delgado, E.M.G.; López, A.L.M. Prevalence of modifiable behavioral risk factors associated to non-communicable diseases in Latin American college students: A systematic review. Nutr Hosp 2017, 34, 1185–1197. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, D.A.S.; Petroski, E.L. The simultaneous presence of health risk behaviors in freshman college students in Brazil. J Community Health 2012, 37, 591–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American College Health Association-National College Health Assessment (ACHA-NCHA). Reference Group Data Report - Fall 2019. American College Health Association. Silver Spring, Maryland. 2020.

- Kwan, M.Y.W.; Faulkner, G.E.J.; Arbour-Nicitopoulos, K.P.; Cairney, J. Prevalence of health-risk behaviours among Canadian post-secondary students: descriptive results from the National College Health Assessment. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.B.; Pan, X.F.; Chen, J.; Cao, A.; Xia, L.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Combined lifestyle factors, all-cause mortality and cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. J Epidemiol Community Health 2021, 75, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brasil. Presidência da República. Secretaria Nacional de Políticas sobre Drogas/SENAD. [National Survey on the Use of Alcohol, Tobacco and Other Drugs among University Students in the 27 Brazilian Capitals]. Brasília, DF: Secretaria Nacional de Políticas sobre Drogas. 2010.

- Oliveira, C.S.; Gordia, A.P.; Quadros, T.M.B.; Campos, W. [Physical activity of Brazilian university students: A literature review]. Rev Atenção Saúde 2014, 12, 71–77. [Google Scholar]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P.; STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Prev Med 2007, 45, 247–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American College Health Association. American College Health Association-National College Health Assessment II (ACHA): Reliability and Validity Analyses 2011. Hanover, MD: American College Health Association. 2013.

- Rahn, R.N.; Pruitt, B.; Goodson, P. Utilization and limitations of the American College Health Association’s National College Health Assessment instrument: a systematic review. J Am Coll Health 2016, 64, 214–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guedes, D.P.; Teixeira, M. Semantic and conceptual equivalences of the National College Health Assessment II. Cad Saude Publica 2012, 28, 806–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guedes, D.P.; Silva, A.L.S. National College Health Assessment II: Psychometric properties and concordance attributes of printed and online formats. Saude Pesq 2020, 13, 143–55. [Google Scholar]

- Feroz, U.; Jami, H.; Masood, S. Role of early exposure to domestic violence in display of aggression among university students. Pak J Psychol Res 2015, 30, 323–342. [Google Scholar]

- Straus, M.A.; Ramirez, I.L. Gender symmetry in prevalence, severity, and chronicity of physical aggression against dating partners by university students in Mexico and USA. Aggress Behav 2007, 33, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.H.; Stevens, C.; Wong, S.H.M.; Yasui, M.; Chen, J.A. The prevalence and predictors of mental health diagnoses and suicide among US college students: implications for addressing disparities in service use. Depress Anxiety 2019, 36, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaesin, S.; Siyoung, C.C.; Beom-Young, C.C.; Jean-Philippe, C.; Jounghee, L.; Sungiae, H. Sex and Racial/Ethnic Differences in Suicidal Consideration and Suicide Attempts among US College Students, 2011-2015. Am J Health Behav 2020, 44, 214–231. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Long, L.; Cai, H.; Wu, Y.; Xu, J.; Shu, C.; et al. Contraception and unintended pregnancy among unmarried female university students: a cross-sectional study from China. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0130212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ssewanyana, D.; Sebena, R.; Petkeviciene, J.; Lukács, A.; Miovsky, M.; et al. Condom use in the context of romantic relationships: A study among university students from 12 universities in four Central and Eastern European countries. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care 2015, 20, 350–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertoli, R.S.; Scheidmantel, C.E.; Carvalho, N.S. College students and HIV infection: A study of sexual behavior and vulnerabilities. Braz J Sex Transm Dis 2016, 28, 90–95. [Google Scholar]

- Larimer, M.E.; Kilmer, J.R.; Lee, C.M. College student drug prevention: a review of individually-oriented prevention strategies. J Drug Issues 2005, 35, 431–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. [III National Survey on Drug Use by Brazilian Population (III LNUD)]. Rio de Janeiro: Laboratório de Informação em Saúde. Instituto de Comunicação e Informação Científica e Tecnológica. Fundação Oswaldo Cruz. 2017.

- Jacob, L.; Freyn, M.; Kalder, M.; Dinas, K.; Kostev, K. Impact of tobacco smoking on the risk of developing 25 different cancers in the UK: A retrospective study of 422,010 patients followed for up to 30 years. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 17420–17429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wicki, M.; Kuntsche, E.; Gmel, G. Drinking at European universities? A review of students’ alcohol use. Addict Behav 2010, 35, 913–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hallett, J.; Howat, P.M.; Maycock, B.R.; McManus, A.; Kypri, K.; Dhaliwal, S.S. Undergraduate student drinking and related harms at an Australian university: Web-based survey of a large random sample. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heradstveit, O.; Skogen, J.C.; Brunborg, G.S.; Lonning, K.J.; Sivertsen, B. Alcohol-related problems among college and university students in Norway: extent of the problem. Scand J Public Health 2021, 49, 402–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, D.K.; Waddell, J.T.; Addictions Research Team. Indirect associations between impulsivity and alcohol outcomes through motives for drinking responsibly among U.S. college students: An integration of Self-Determination Theory and the acquired preparedness model. Addict Res Theory 2023, 31, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, H.R.; McMorris, B.J.; Catalano, R.F.; Fleming, C.B.; Haggerty, K.P.; Abbott, R.D. Increases in alcohol and marijuana use during the transition out of high school into emerging adulthood: the effects of leaving home, going to college, and high school protective factors. J Stud Alcohol 2006, 67, 810–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peltzer, K.; Pengpid, S. Nocturnal sleep problems among university students from 26 countries. Sleep Breath 2015, 19, 499–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sa, J.; Choe, S.; Cho, B.Y.; Chaput, J.P.; Kim, G.; Park, C.H. Relationship between sleep and obesity among U.S. and South Korean college students. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brinks, H.; Vincent, G.E.; Irwin, C.; Heidke, P.; Vandelanotte, C.; Williams, S.L.; et al. Associations between sleep and lifestyle behaviours among Australian nursing students: A cross-sectional study. Collegian 2020, 28, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, R.W.; Vissa, K.; Hall, C.; Poling, K.; Athey, A.; Alfonso-Miller, P.; et al. Sleep problems are associated with academic performance in a national sample of collegiate athletes. J Am Coll Health 2021, 69, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irish, L.A.; Kline, C.E.; Gunn, H.E.; Buysse, D.J.; Hall, M.H. The role of sleep hygiene in promoting public health: a review of empirical evidence. Sleep Med Rev 2015, 22, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carone, C.M.M.; Silva, B.P.; Rodrigues, L.T.; Tavares, O.S.; Carpena, M.S.; Santos, I.S. Factors associated with sleep disorders in university students. Cad Saude Publica 2020, 36, e00074919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aune, D.; Giovannucci, E.; Boffetta, P.; Fadnes, L.T.; Keum, N.; Norat, T.; et al. Fruit and vegetable intake and the risk of cardiovascular disease, total cancer and all-cause mortality - A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Int J Epidemiol 2017, 46, 1029–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, V.M.; Bray, J.; Fernandes, A.C.; Bernardo, G.L.; Hartwell, H.; Martinelli, S.S.; et al. Vegetable consumption and factors associated with increased intake among college students: a scoping review of the last 10 years. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, E.J.; Caine-Bish, N. Effect of nutrition intervention using a general nutrition course for promoting fruit and vegetable consumption among college students. J Nutr Educ Behav 2009, 41, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wardle, J.; Haase, A.M.; Steptoe, A.; Nillapun, M.; Jonwutiwes, K.; Bellisle, F. Gender differences in food choice: the contribution of health beliefs and dieting. Ann Behav Med 2004, 27, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirabitur, E.; Peterson, K.E.; Rathz, C.; Matlen, S.; Kasper, N. Predictors of college-student food security and fruit and vegetable intake differ by housing type. J Am Coll Health 2016, 64, 555–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Small, M.; Bailey-Davis, L.; Morgan, N.; Maggs, J. Changes in eating and physical activity behaviors across seven semesters of college: living on or off campus matters. Health Educ Behav 2013, 40, 435–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnes, S.; Brown, K.; McDermott, R.; Bryant, C.A.; Kromrey, J. Perceived parenting style and the eating practices of college freshmen. Am J Health Educ 2012, 43, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, A.; Steptoe, A.; Sallis, J.F.; Wardle, J. Leisure-time physical activity in university students from 23 countries: associations with health beliefs, risk awareness, and national economic development. Prev Med 2004, 39, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keating, X.D.; Guan, J.; Piñero, J.C.; Bridges, D.M. A meta-analysis of college students physical activity behaviors. J Am Coll Health 2005, 54, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Departamento de Análise em Saúde e Vigilância de Doenças Não Transmissíveis. [Vigitel Brasil 2023: Surveillance of risk and protective factors for chronic diseases by telephone survey: estimates on the frequency and sociodemographic distribution of risk and protective factors for chronic diseases in the capitals of the 26 Brazilian states and the Federal District in 2023]. Ministério da Saúde, Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde, Departamento de Análise em Saúde e Vigilância de Doenças não Transmissíveis. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde, 2023.

- Bakker, E.A.; Lee, D.C.; Hopman, M.T.E.; Oymans, E.J.; Watson, P.M.; Thompson, P.D.; et al. Dose-response association between moderate to vigorous physical activity and incident morbidity and mortality for individuals with a different cardiovascular health status: A cohort study among 142,493 adults from the Netherlands. PLoS Med 2021, 18, e1003845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meader, N.; King, K.; Moe-Byrne, T.; Wright, K.; Graham, H.; Petticrew, M.; et al. A systematic review on the clustering and co-occurrence of multiple risk behaviours. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eratay, E.; Aydoğan, Y. Study of the relationship between leisure time activities and assertiveness levels of students of Abant Izzet Baysal University. Procedia Soc Behav Sci 2015, 191, 2213–2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mielke, G.I.; Ramis, T.R.; Habeyche, E.C.; Oliz, M.M.; Tessmer, S.; Azevedo, M.R.; et al. Physical activity and associated factors among first-year university students. Braz J Phys Act Health 2010, 15, 57–64. [Google Scholar]

- Keating, X.D.; Guan, J.; Piñero, J.C.; Bridges, D.M. A meta-analysis of college students physical activity behaviors. J Am Coll Health 2005, 54, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deforche, B.; Van Dyc, D.; Deliens, T.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I. Changes in weight, physical activity, sedentary behaviour and dietary intake during the transition to higher education: a prospective study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2015, 12, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauman, A.E.; Reis, R.S.; Sallis, J.F.; Wells, J.C.; Loos, R.J.; Martin, B.W. Correlates of physical activity: why are some people physically active and others not? Lancet, 2012; 380, 258–2571. [Google Scholar]

| Questions | Answer options | Risk definitions |

|---|---|---|

| Personal security and violence | ||

| (a) Within the last 12 months, how often did you wear a seatbelt when you rode in a car? (b) Within the last 12 months, how often did you wear a helmet when you rode a bicycle/motorcycle/skating? (c) Within the last 12 months were you in a physical fight? (d) Have you ever seriously considered suicide? |

“Never”, “rarely”, “sometimes”, “most of the time”, “always”. “Never”, “rarely”, “sometimes”, “most of the time”, “always”. “No”, “yes”. “No”, “yes”. |

“Never”, “rarely”, “sometimes”. “Never”, “rarely”, “sometimes”. “Yes” “Yes” |

| Sexual behavior and contraception | ||

| (a) Within the last 12 months, with how many partners have you had oral sex, vaginal intercourse, or anal intercourse? (b) Within the last 30 days, how often did you or your partner(s) use a condom or other protective barrier (e.g., male condom, female condom, dam, glove) during oral sex, vaginal intercourse, or anal intercourse? |

Participants pointed out the number of partners. “Never”, “rarely”, “sometimes”, “most of the time”, “always”. |

≥ 3 partners. “Never”, “rarely”, “sometimes”. |

| Addictive substance use | ||

| (a) Within the last 30 days, on how many days did you use tobacco and derivatives (e.g., cigarettes, e-cigarettes, hookah, cigars, smokeless tobacco)? (b) Over the last two weeks, how many times have you had ≥ 5 drinks of alcohol at a sitting (e.g., beer, wine, distilled drinks)? (c) Within the last 30 days, on how many days did use illicit drugs (e.g., marijuana, cocaine, opiates, inhalants, ecstasy)? |

“No days”, “1-2 days”, “3-5 days”, “6-9 days”, “10-19 days”, “20-29 days” “daily”. Participants pointed out the number of times. “No days”, “1-2 days”, “3-5 days”, “6-9 days”, “10-19 days”, “20-29 days”, “daily”. |

Any frequency of use. Any frequency of use. Any frequency of use. |

| Eating habits, physical activity, and sleep | ||

| (a) How many servings of fruits and vegetables do you usually have per day (1 serving = 1 medium piece of fruit; ½ cup fresh, frozen, or canned fruits/vegetables; ¾ cup fruit/vegetable juice; 1 cup salad greens; or ¼ cup dried fruit? (b) On how many of the past 7 days did you do physical activity of moderate to vigorous intensity (caused a noticeable or large increase in breathing or heart rate, such as a brisk walk or jogging) for at least 30 minutes? (c) On how many of the past 7 nights did you get enough sleep so that you felt rested when you woke up in the morning? |

“No servings per day”, “1-2 servings per day”, “3-4 servings per day”, “≥ 5 servings per day”. Participants pointed out the number of days, from none to 7 days. Participants pointed out the number of nights, from none to 7 nights. |

< 5 servings per day. < 5 days per week. < 5 nights per week. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).