Submitted:

09 April 2024

Posted:

10 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Biodiversity Hotspot Areas and Protected Areas

1.2. The History of Protected Areas in Myanmar

1.3. Rresearch Objectives

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Species

2.2. Species Distribution Model

2.3. Environmental Parameters

2.4. Protected Area Data

3. Results

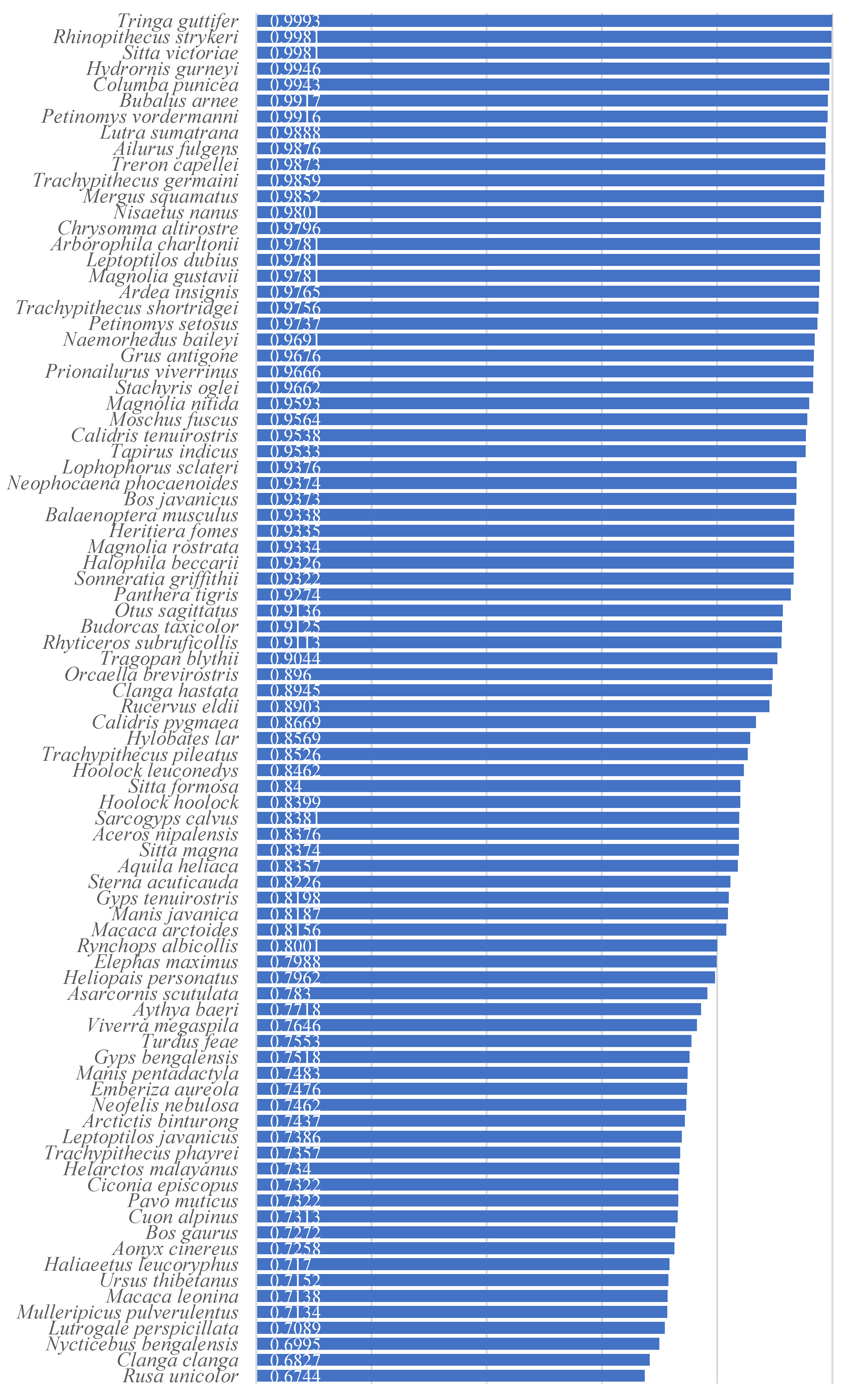

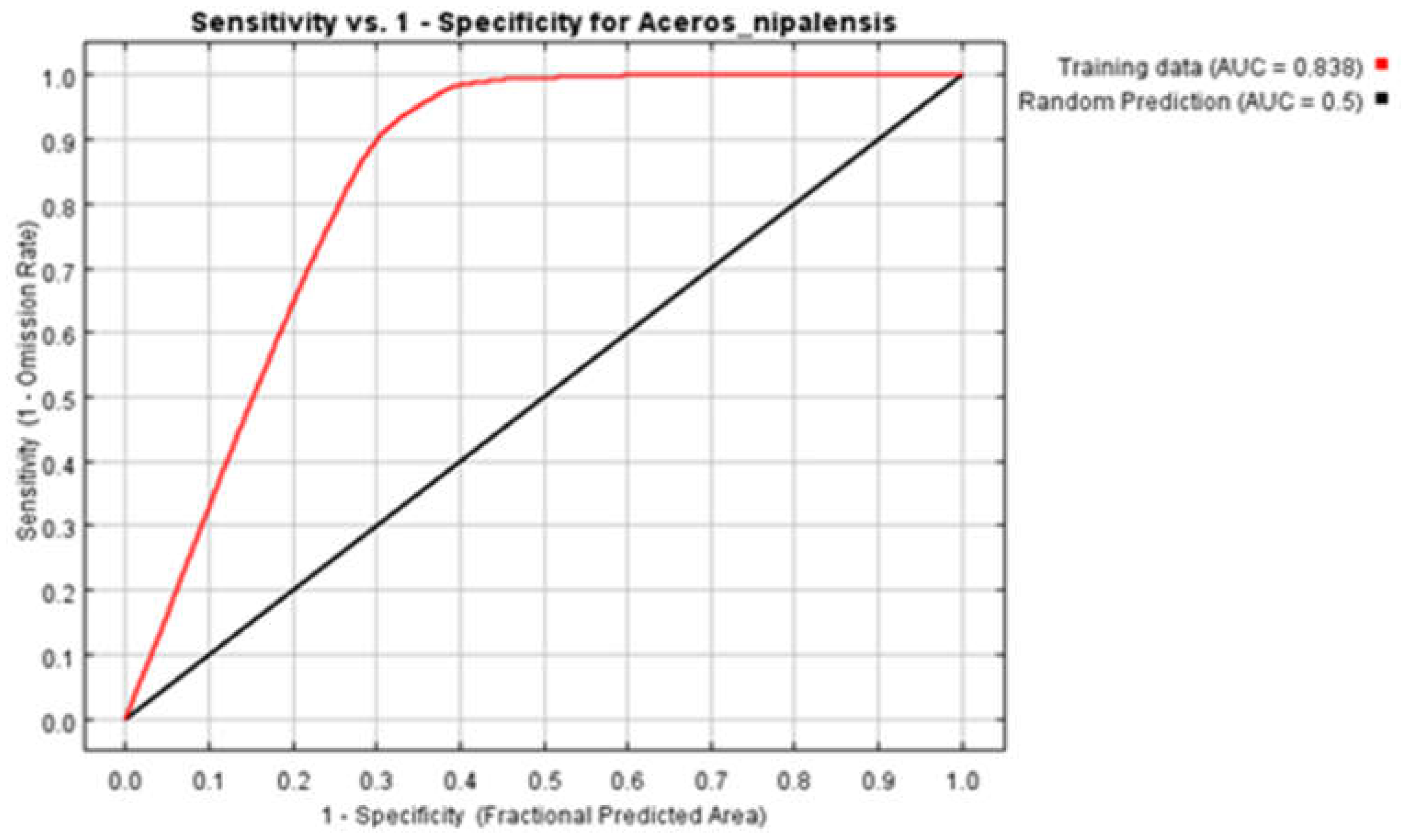

3.1. Evaluation of the Prediction Results from the Maximum Entropy Model

3.1.1. Factors Influencing the Potential Distribution of Species

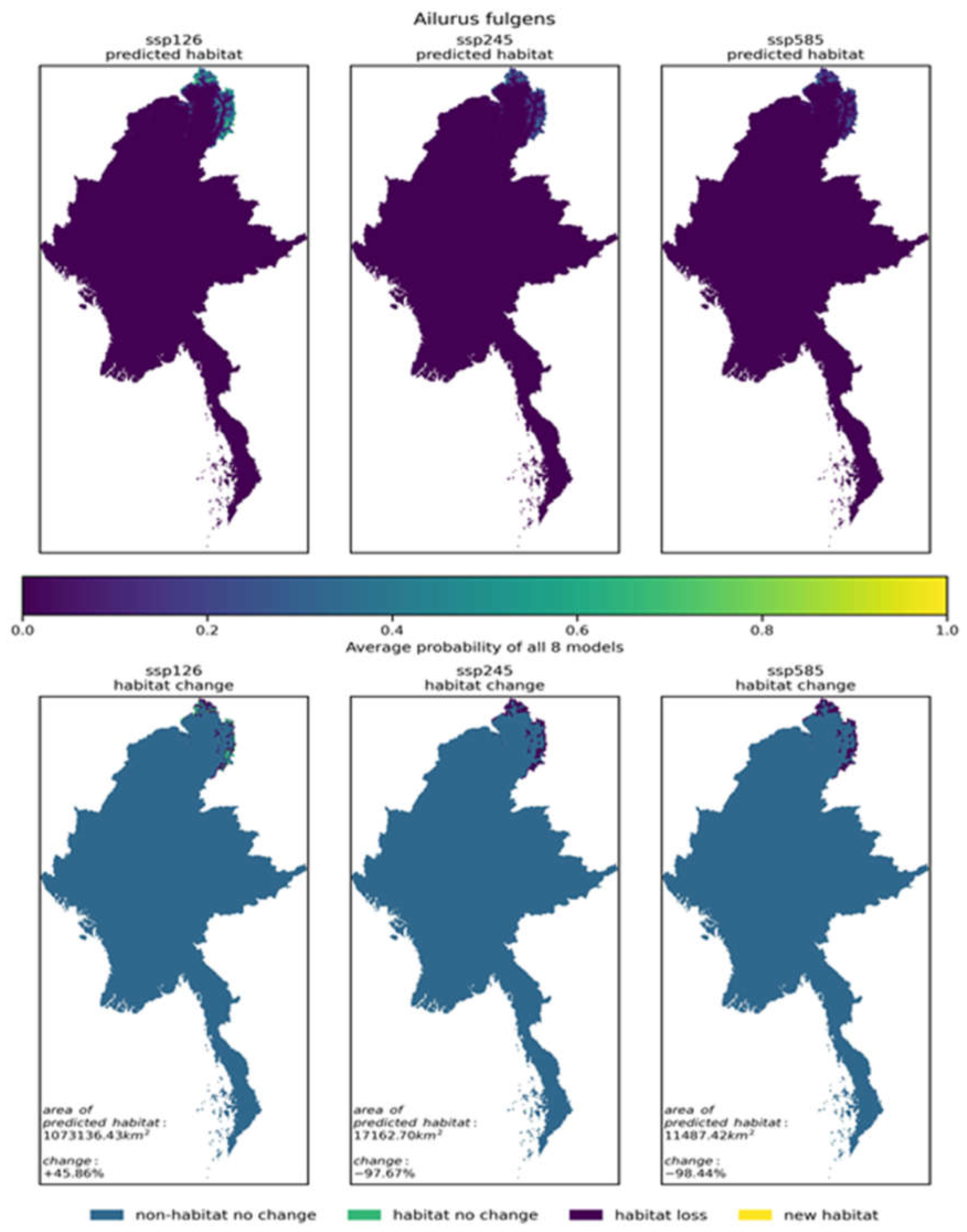

3.1.2. Predicting the Potential Distribution of Species

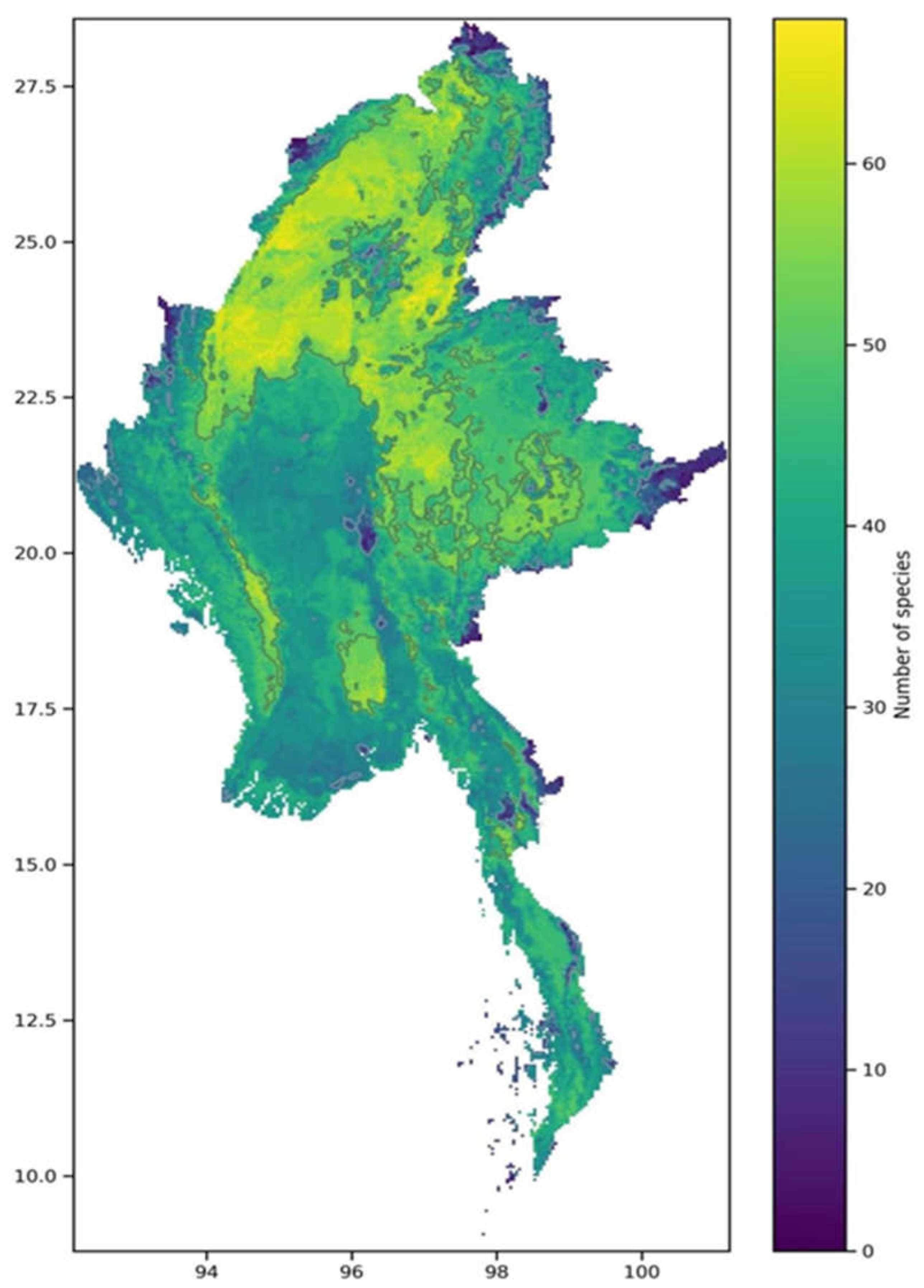

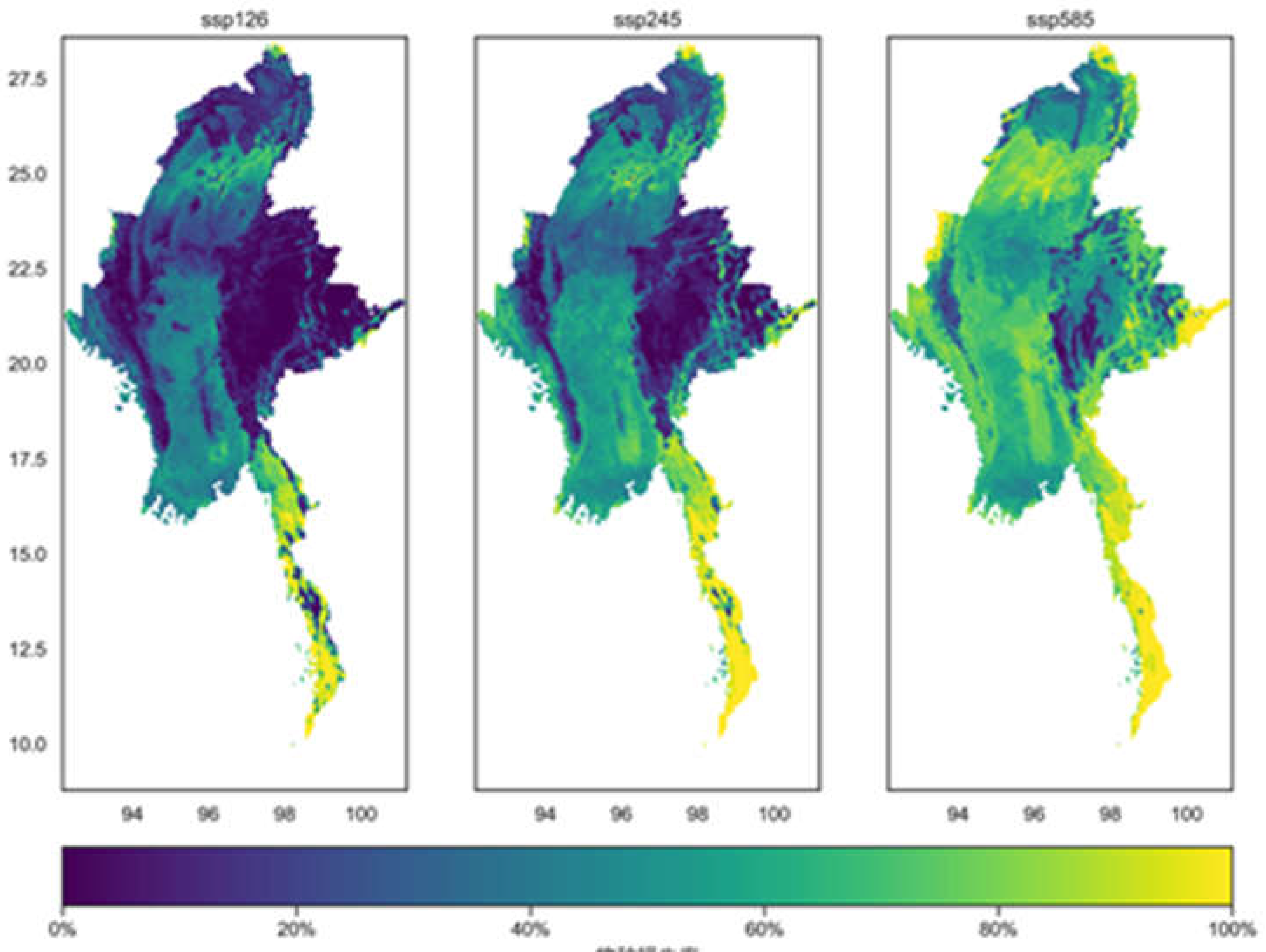

3.1.3. Spatial Distribution Pattern and Its Changes of Species Richness

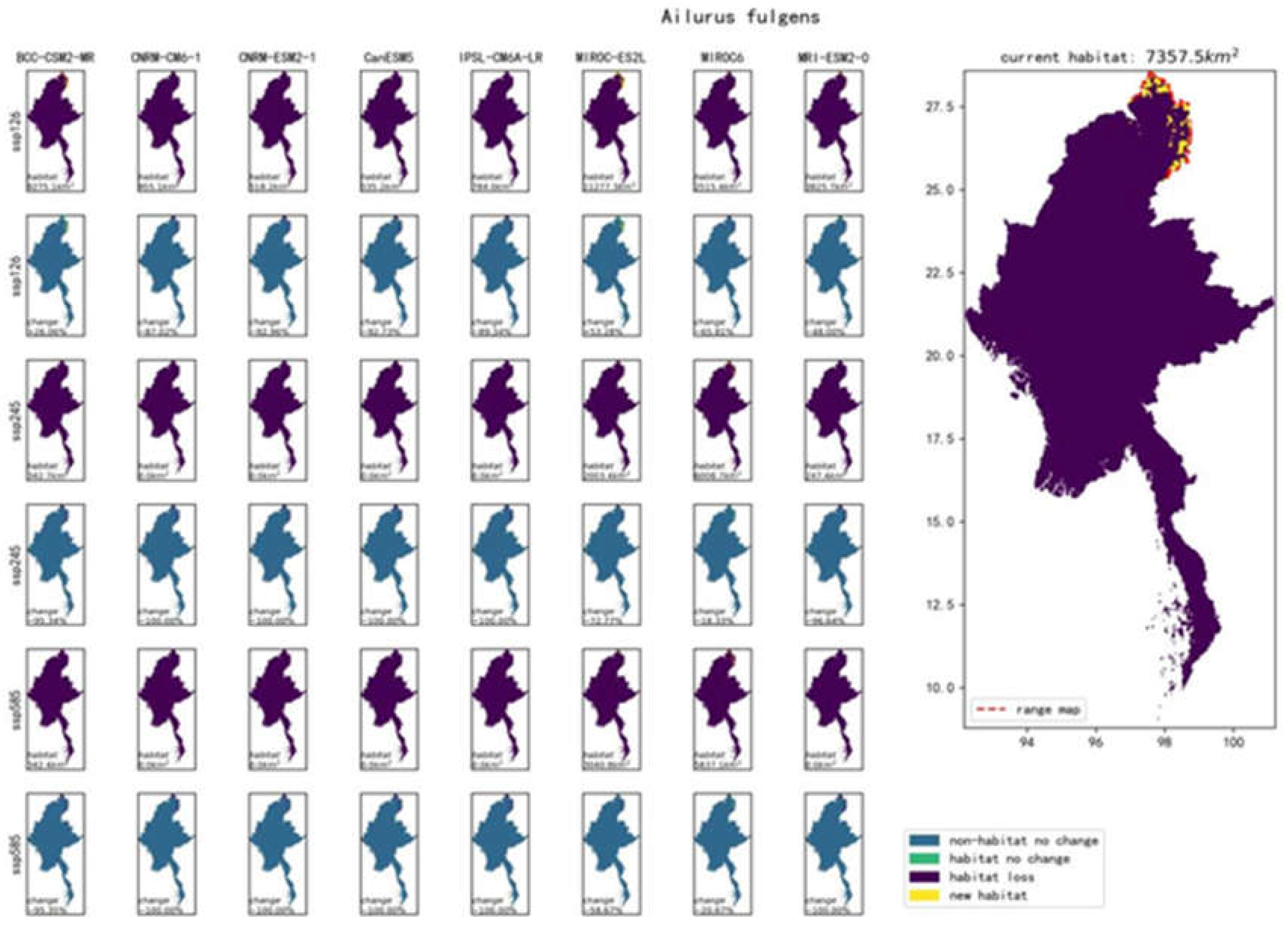

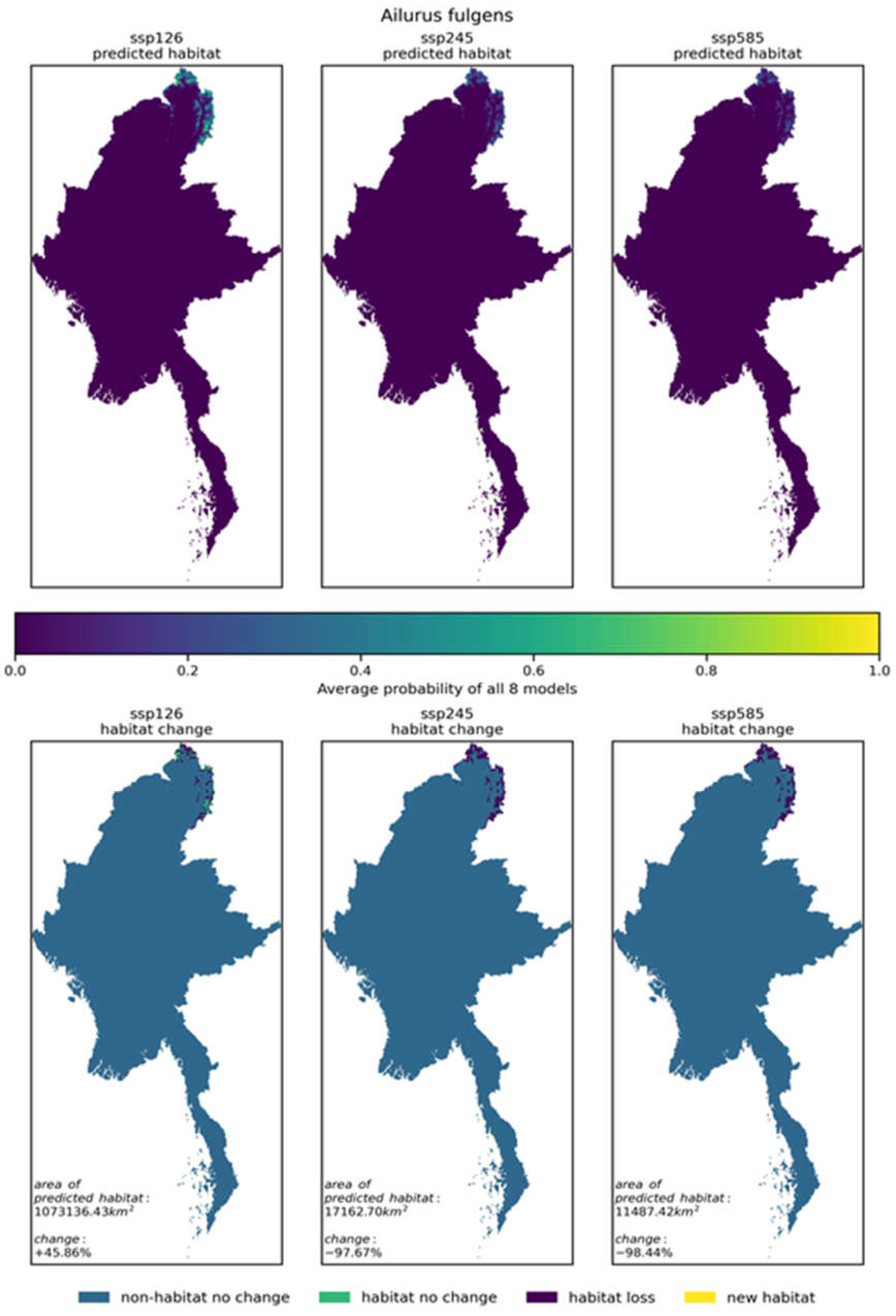

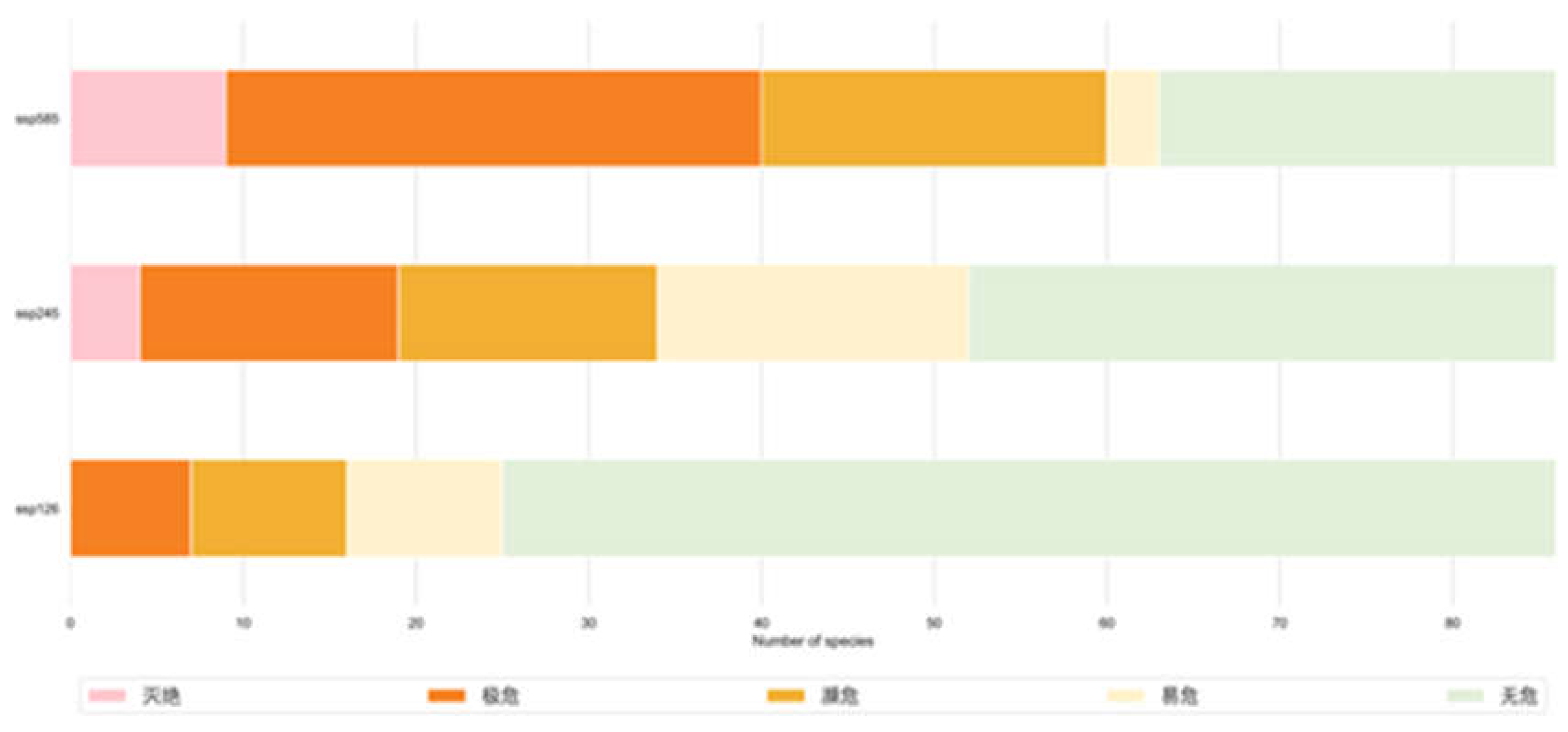

3.1.4. Changes in the Proportion and Area of Protected Habitats for Representative Species in Myanmar

| Changes in Habitats | Species | Current Habitats | 2081-2100 Rate of Change in Habitat Area | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SSP126 | SSP245 | SSP585 | |||

| Increase | Leptoptilos javanicus | 422736.6km² (63.17%) | +8.53% | +5.09% | +6.62% |

| Asarcornis scutulata | 264736.2km² (39.56%) | +16.29% | +30.04% | +53.02% | |

| Sterna acuticauda | 192782.6km² (28.81%) | +11.03% | +19.55% | +31.43% | |

| Hoolock leuconedys | 139346.1km² (20.82%) | +23.89% | +70.77% | +87.35% | |

| Trachypithecus pileatus | 123368.1km² (18.43%) | +7.23% | +16.56% | +31.83% | |

| Orcaella brevirostris | 113058.2km² (16.89%) | +41.13% | +66.00% | +66.02% | |

| Balaenoptera musculus | 33089.5km² (4.94%) | +168.79% | +180.58% | +218.70% | |

| Halophila beccarii | 33023.8km² (4.93%) | +159.56% | +178.95% | +221.00% | |

| Sonneratia griffithii | 32579.4km² (4.87%) | +159.07% | +159.97% | +210.87% | |

| Heritiera fomes | 31835.0km² (4.76%) | +174.29% | +182.08% | +256.89% | |

| Neophocaena phocaenoides | 27278.3km² (4.08%) | +151.88% | +155.14% | +224.12% | |

| Calidris tenuirostris | 19394.8km² (2.90%) | +38.69% | +44.48% | +10.10% | |

| Chrysomma altirostre | 11358.0km² (1.70%) | +65.36% | +78.33% | +683.16% | |

| Uncertain | Haliaeetus leucoryphus | 474587.9km² (70.91%) | -5.96% | -5.68% | +1.05% |

| Ciconia episcopus | 428993.9km² (64.10%) | +1.96% | -2.68% | -3.49% | |

| Trachypithecus phayrei | 423846.2km² (63.33%) | +3.00% | -5.93% | -8.50% | |

| Aonyx cinereus | 418913.5km² (62.59%) | +8.53% | +8.55% | -20.88% | |

| Cuon alpinus | 388990.2km² (58.12%) | +2.41% | +2.99% | -23.62% | |

| Turdus feae | 326416.3km² (48.77%) | +11.01% | +24.58% | -46.45% | |

| Heliopais personatus | 248315.0km² (37.10%) | +1.12% | -11.96% | -28.01% | |

| Rynchops albicollis | 242712.3km² (36.27%) | +1.54% | -19.08% | -34.80% | |

| Gyps tenu-irostris | 193558.3km² (28.92%) | -16.01% | -0.89% | +28.31% | |

| Sitta formosa | 119479.4km² (17.85%) | +12.71% | -4.28% | -49.46% | |

| Rucervus eldii | 81429.0km² (12.17%) | -10.72% | +9.95% | +46.26% | |

| Rhyticeros subruficollis | 56339.7km² (8.42%) | -32.88% | -36.83% | +113.61% | |

| Magnolia nitida | 20776.6km² (3.10%) | +74.80% | -0.67% | -8.56% | |

| Moschus fuscus | 17163.1km² (2.56%) | +35.87% | -82.13% | -89.11% | |

| Leptoptilos dubius | 10690.4km² (1.60%) | +20.27% | -20.56% | -82.19% | |

| Ailurus fulgens | 7357.4km² (1.10%) | +45.86% | -97.67% | -98.44% | |

| Rhinopithecus strykeri | 3182.8km² (0.48%) | +51.90% | -98.80% | -100.00% | |

| Decrease | Rusa unicolor | 601176.8km² (89.83%) | -20.23% | -26.46% | -60.08% |

| Clanga clanga | 586027.6km² (87.56%) | -24.35% | -38.89% | -67.76% | |

| Nycticebus bengalensis | 522585.9km² (78.09%) | -22.35% | -43.96% | -73.20% | |

| Lutrogale perspicillata | 516162.0km² (77.13%) | -32.18% | -53.32% | -76.81% | |

| Mulleripicus pulverulentus | 475195.8km² (71.00%) | -13.10% | -24.08% | -51.94% | |

| Ursus thibetanus | 460878.1km² (68.86%) | -12.19% | -33.90% | -76.96% | |

| Macaca leonina | 451414.2km² (67.45%) | -24.65% | -36.91% | -77.68% | |

| Pavo muticus | 436904.7km² (65.28%) | -11.16% | -33.16% | -64.89% | |

| Bos gaurus | 424608.9km² (63.45%) | -19.22% | -33.25% | -78.50% | |

| Helarctos malayanus | 387404.0km² (57.89%) | -11.14% | -41.30% | -79.75% | |

| Emberiza aureola | 386723.6km² (57.78%) | -28.85% | -42.49% | -78.59% | |

| Arctictis binturong | 357410.7km² (53.40%) | -10.22% | -33.96% | -75.55% | |

| Neofelis nebulosa | 357072.1km² (53.35%) | -23.12% | -39.36% | -79.87% | |

| Manis pentadactyla | 354014.9km² (52.90%) | -16.99% | -27.47% | -78.71% | |

| Gyps bengalensis | 343440.2km² (51.32%) | -7.32% | -2.17% | -54.71% | |

| Viverra megaspila | 332328.7km² (49.66%) | -28.97% | -40.56% | -67.73% | |

| Aythya baeri | 299043.2km² (44.68%) | -28.05% | -46.80% | -61.93% | |

| Elephas maximus | 253161.3km² (37.83%) | -39.20% | -59.28% | -88.28% | |

| Manis javanica | 189200.6km² (28.27%) | -32.66% | -61.18% | -85.57% | |

| Macaca arctoides | 169347.3km² (25.30%) | -27.90% | -27.24% | -75.83% | |

| Sitta magna | 145239.9km² (21.70%) | -26.77% | -65.45% | -96.53% | |

| Sarcogyps calvus | 141399.4km² (21.13%) | -26.36% | -23.12% | -90.33% | |

| Aceros nipalensis | 137273.8km² (20.51%) | -25.67% | -35.03% | -82.36% | |

| Hoolock hoolock | 127788.6km² (19.09%) | -24.86% | -52.04% | -92.76% | |

| Aquila heliaca | 125941.0km² (18.82%) | -12.38% | -51.60% | -81.15% | |

| Calidris pygmaea | 100693.4km² (15.05%) | -38.15% | -78.15% | -98.54% | |

| Hylobates lar | 98024.8km² (14.65%) | -21.46% | -44.91% | -93.17% | |

| Clanga hastata | 62676.9km² (9.37%) | -37.78% | -96.06% | -99.97% | |

| Tragopan blythii | 56152.2km² (8.39%) | -23.74% | -39.64% | -74.65% | |

| Bos javanicus | 52225.4km² (7.80%) | -45.70% | -67.12% | -72.61% | |

| Panthera tigris | 51492.0km² (7.69%) | -55.12% | -76.26% | -99.52% | |

| Otus sagittatus | 47055.9km² (7.03%) | -52.65% | -54.27% | -92.10% | |

| Budorcas taxicolor | 47053.5km² (7.03%) | -37.80% | -45.91% | -89.16% | |

| Tapirus indicus | 31179.7km² (4.66%) | -63.72% | -83.39% | -99.60% | |

| Magnolia rostrata | 28979.7km² (4.33%) | -25.58% | -54.56% | -94.81% | |

| Lophophorus sclateri | 25407.5km² (3.80%) | -2.33% | -50.72% | -88.73% | |

| Grus antigone | 18674.7km² (2.79%) | -15.90% | -84.90% | -100.00% | |

| Ardea insignis | 16872.4km² (2.52%) | -73.87% | -96.49% | -97.40% | |

| Stachyris oglei | 14861.8km² (2.22%) | -78.27% | -89.01% | -94.37% | |

| Prionailurus viverrinus | 13669.1km² (2.04%) | -17.97% | -75.80% | -94.43% | |

| Petinomys setosus | 12456.8km² (1.86%) | -93.12% | -91.28% | -99.38% | |

| Naemorhedus baileyi | 12265.1km² (1.83%) | -21.61% | -58.42% | -94.89% | |

| Trachypithecus shortridgei | 10162.7km² (1.52%) | -21.50% | -78.04% | -99.63% | |

| Magnolia gustavii | 9758.6km² (1.46%) | -27.12% | -36.25% | -99.79% | |

| Arborophila charltonii | 9145.4km² (1.37%) | -75.23% | -98.85% | -100.00% | |

| Nisaetus nanus | 7553.6km² (1.13%) | -92.78% | -100.00% | -100.00% | |

| Mergus squamatus | 6565.9km² (0.98%) | -97.62% | -98.51% | -100.00% | |

| Trachypithecus germaini | 6326.0km² (0.95%) | -70.69% | -99.67% | -99.67% | |

| Lutra sumatrana | 5909.2km² (0.88%) | -46.93% | -94.82% | -97.10% | |

| Treron capellei | 4940.9km² (0.74%) | -11.45% | -16.95% | -92.38% | |

| Hydrornis gurneyi | 4274.8km² (0.64%) | -84.79% | -98.53% | -100.00% | |

| Petinomys vordermanni | 3780.1km² (0.56%) | -60.79% | -97.79% | -95.03% | |

| Bubalus arnee | 3564.3km² (0.53%) | -65.58% | -5.85% | -90.38% | |

| Columba punicea | 2957.5km² (0.44%) | -89.65% | -100.00% | -100.00% | |

| Sitta victoriae | 1196.4km² (0.18%) | -96.66% | -100.00% | -100.00% | |

| Tringa guttifer | 272.1km² (0.04%) | -92.31% | -100.00% | -100.00% | |

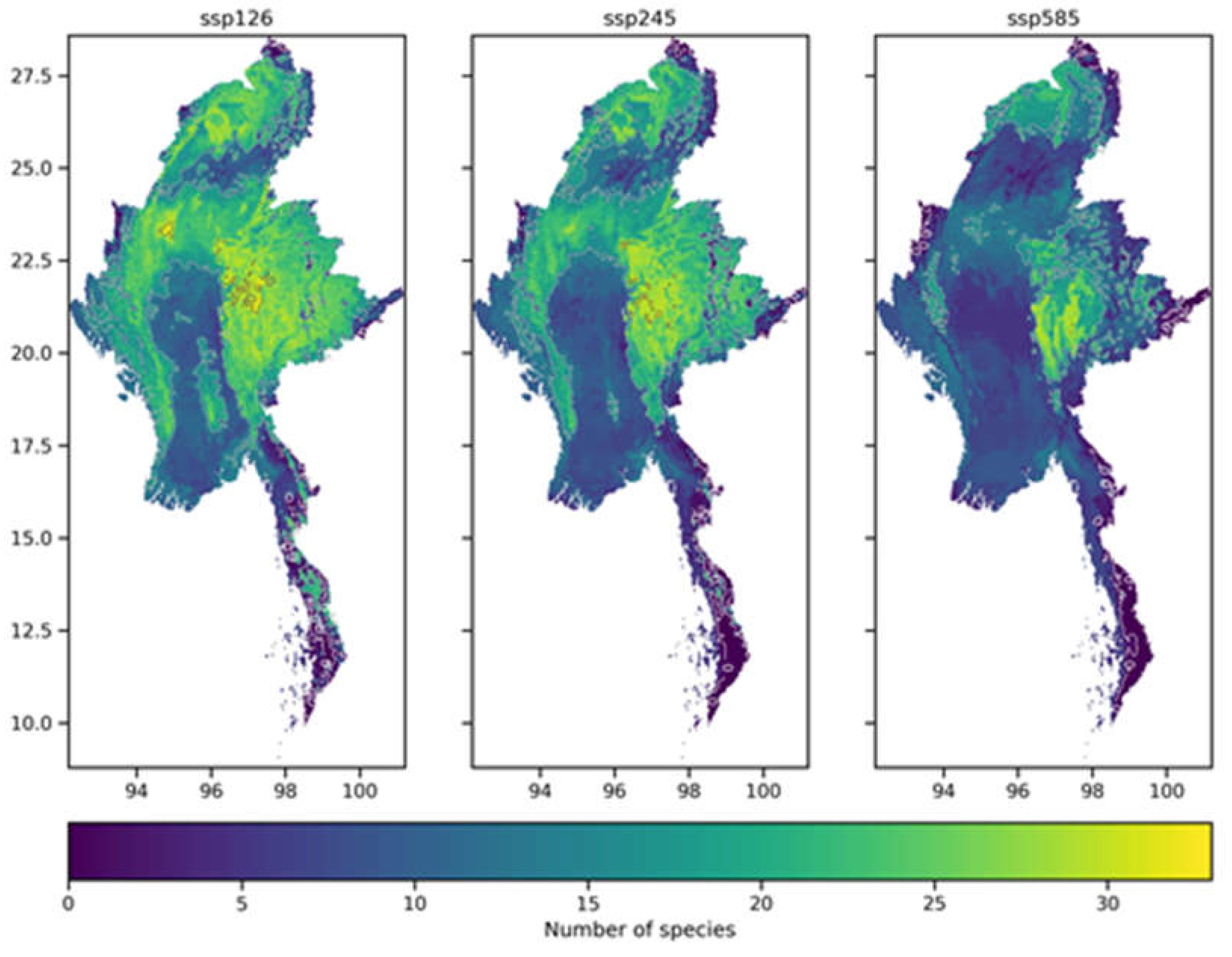

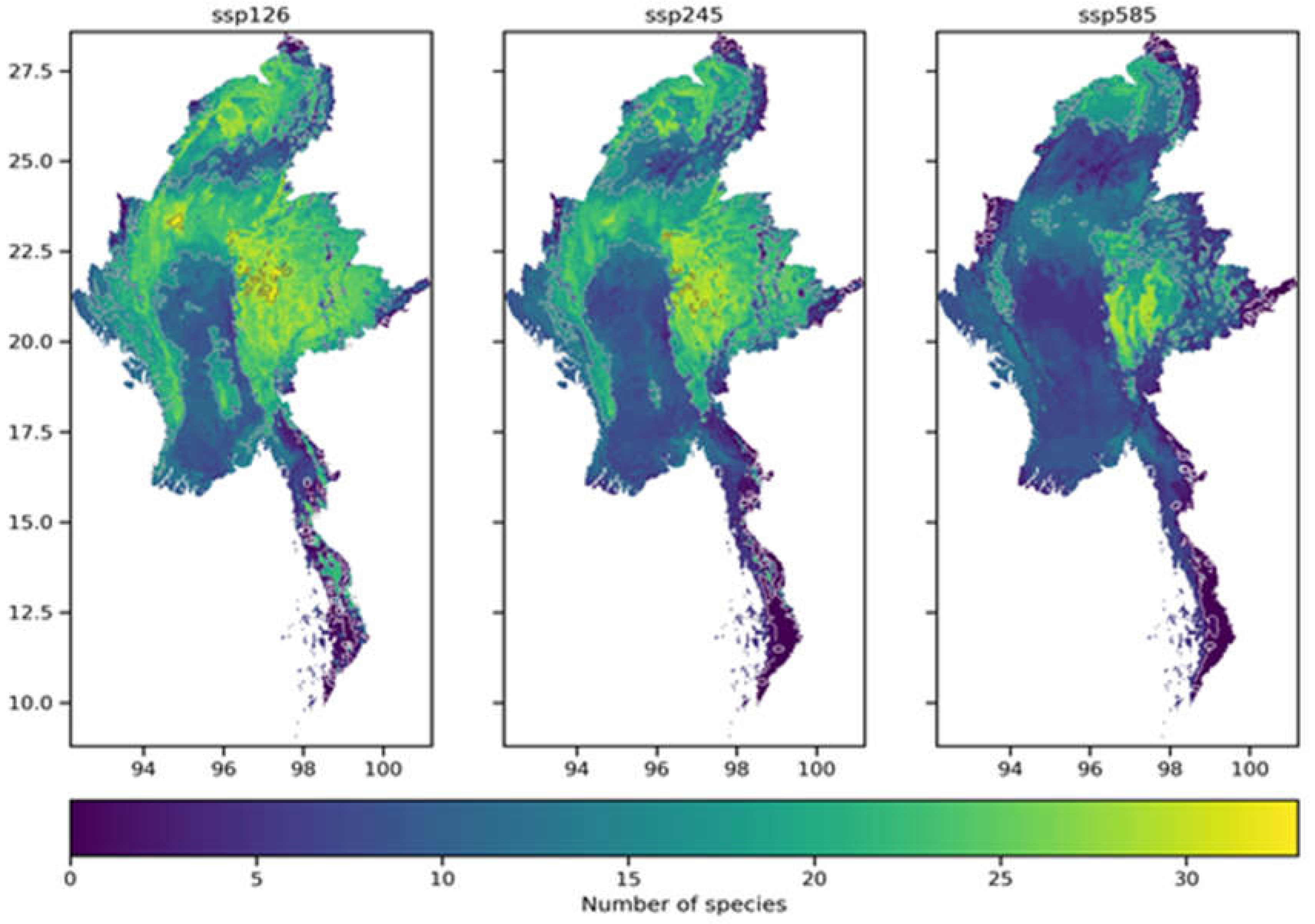

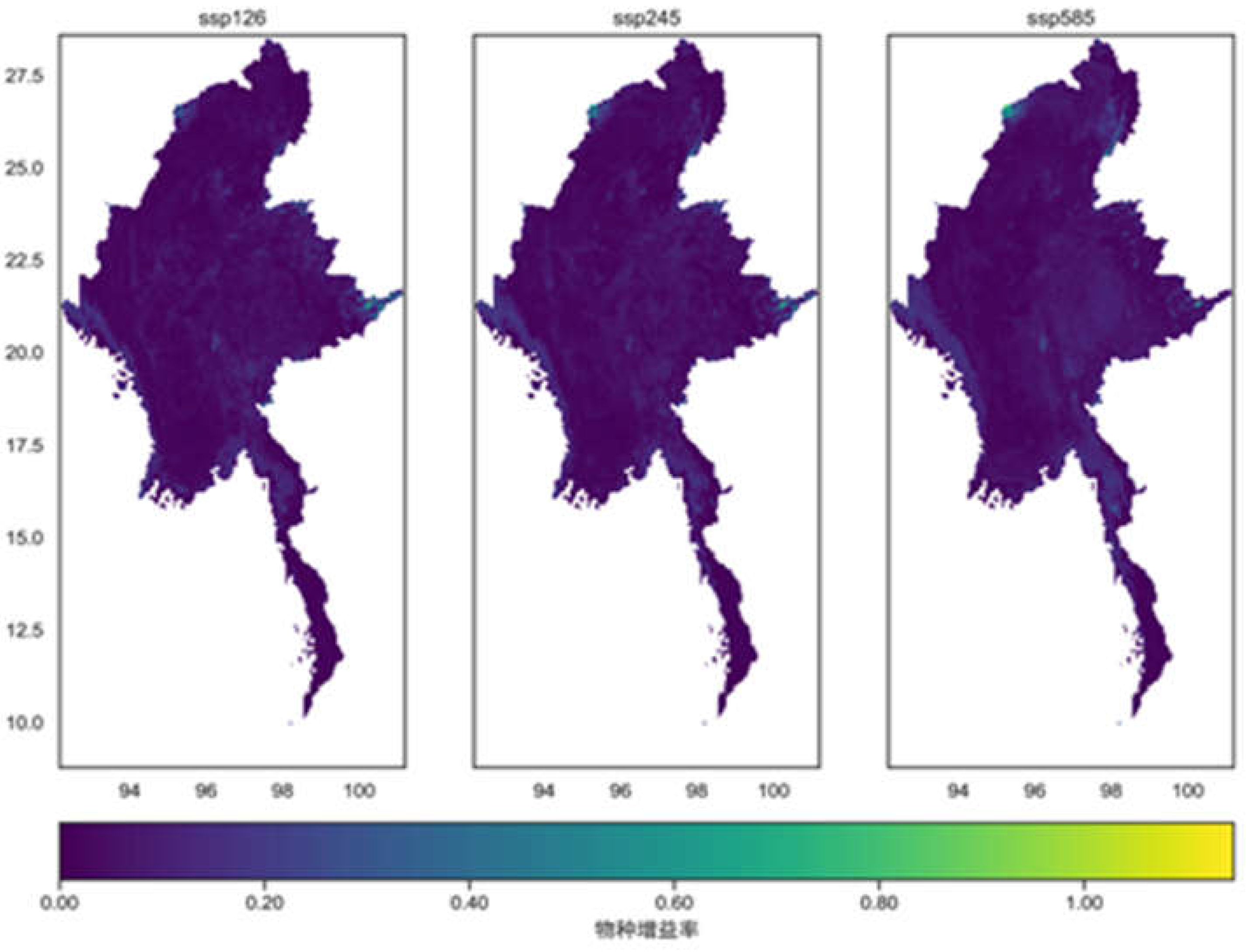

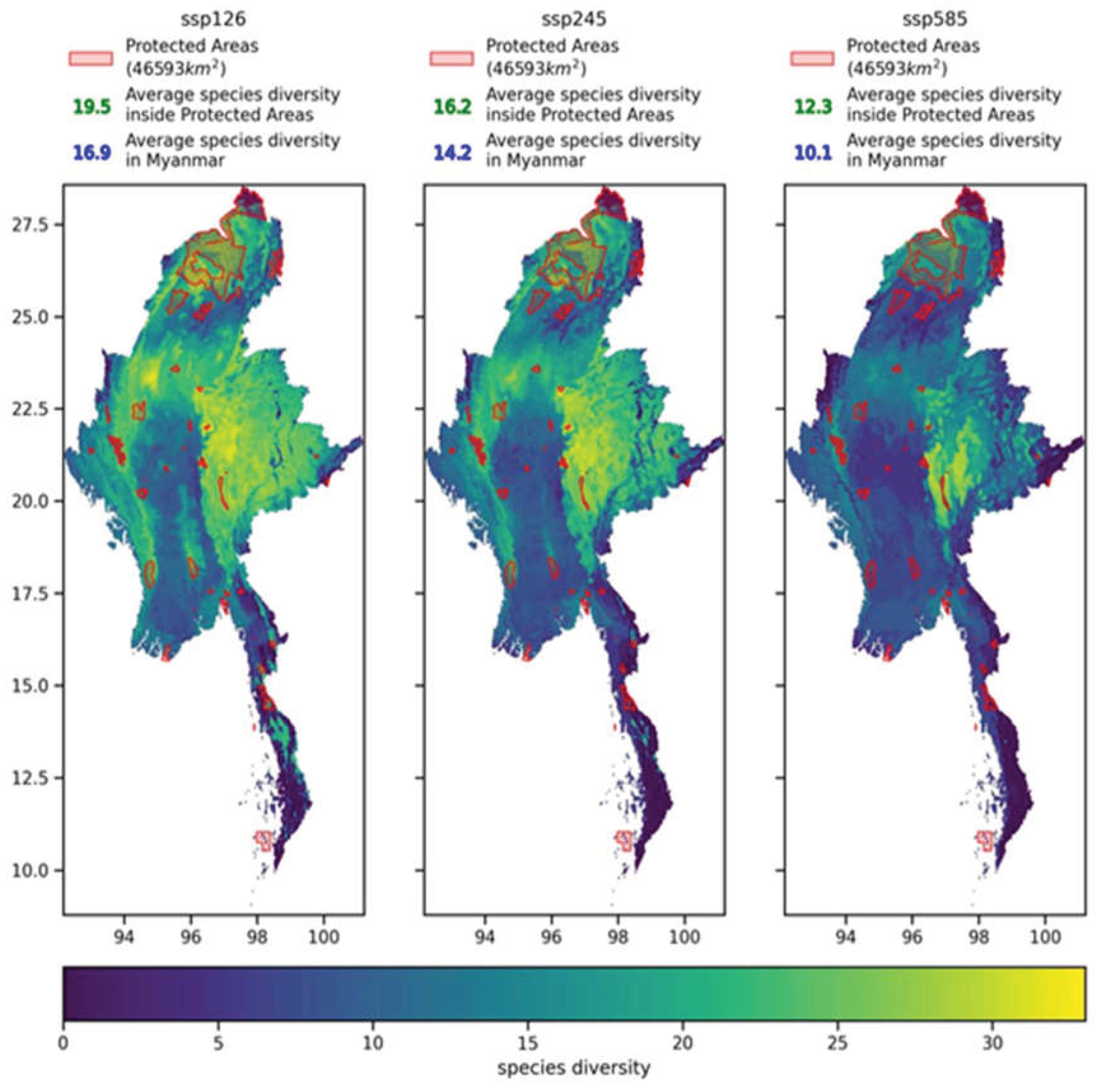

3.1.5. Predicting the Pattern of Species Richness in Myanmar

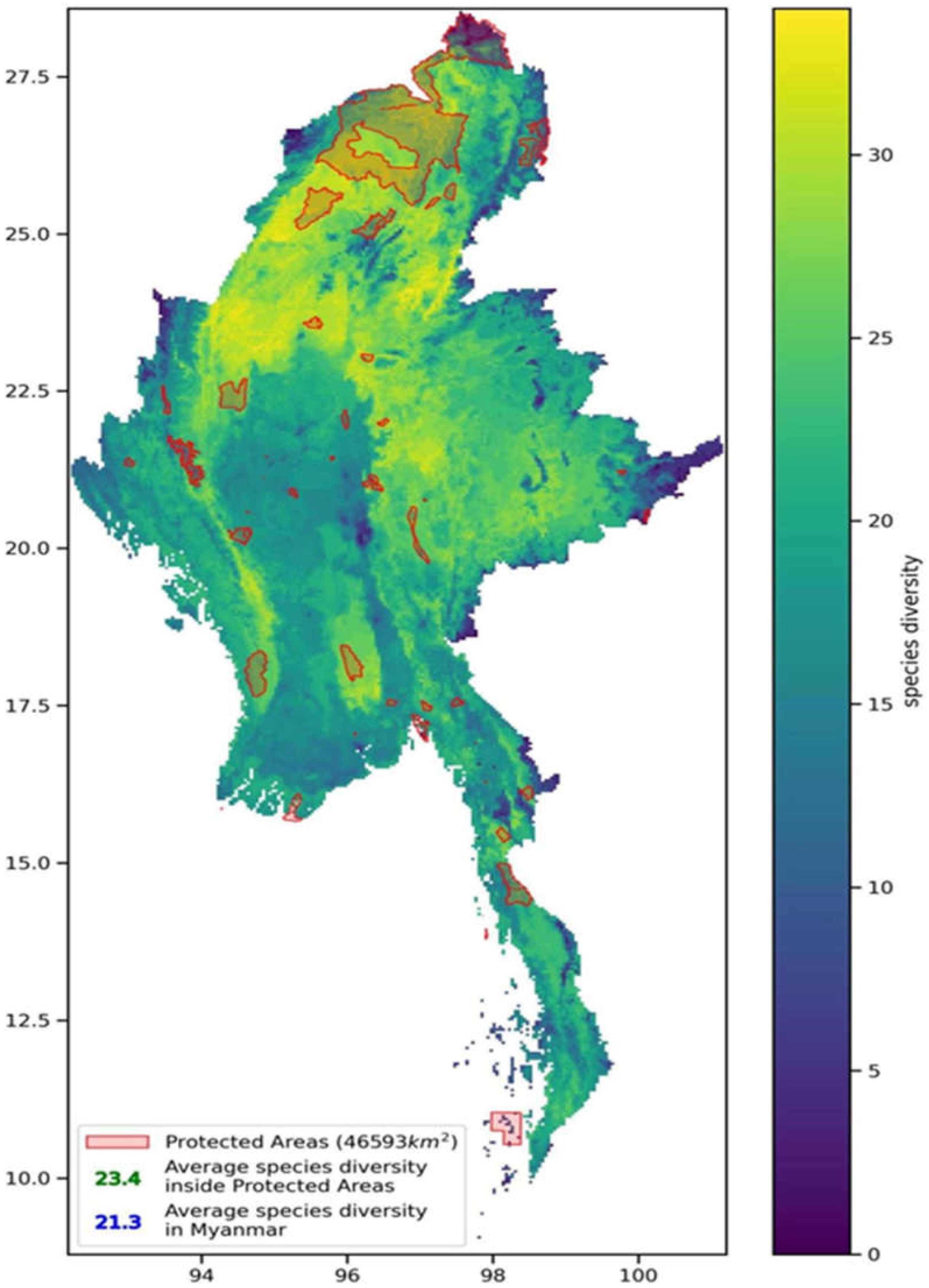

3.1.6. The Effectiveness of Protected Areas

3.1.7. The proportion of Species Distribution Area within Protected Areas

4. Discussion

4.1. Discussion on the Advantages and Disadvantages of Species Distribution Models

4.2. The Controversy Surrounding IUCN Expert Range Map

4.3. Protected Area under Threat

4.4. The Protected Area Network of Myanmar

4.5. Effectiveness of Protected Areas

5. Conclusions

References

- Hoban, S.; Bruford, M.W.; da Silva, J.M.; Funk, W.C.; Frankham, R.; Gill, M.J.; Grueber, C.E.; Heuertz, M.; Hunter, M.E.; Kershaw, F. Genetic diversity goals and targets have improved, but remain insufficient for clear implementation of the post-2020 global biodiversity framework. Conservation Genetics 2023, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Gatiso, T.T.; Kulik, L.; Bachmann, M.; Bonn, A.; Bösch, L.; Eirdosh, D.; Freytag, A.; Hanisch, S.; Heurich, M.; Sop, T. Effectiveness of protected areas influenced by socio-economic context. Nature Sustainability 2022, 5, 861-868. [CrossRef]

- McRae, L.; Freeman, R.; Geldmann, J.; Moss, G.B.; Kjær-Hansen, L.; Burgess, N.D. A global indicator of utilized wildlife populations: Regional trends and the impact of management. One Earth 2022, 5, 422-433. [CrossRef]

- Ceballos, G.; Ehrlich, P.R. The misunderstood sixth mass extinction. Science 2018, 360, 1080-1081. [CrossRef]

- Martin, P.A.; Green, R.E.; Balmford, A. The biodiversity intactness index may underestimate losses. Nature Ecology & Evolution 2019, 3, 862-863.

- Kimmel, K.; Clark, M.; Tilman, D. Impact of multiple small and persistent threats on extinction risk. Conservation Biology 2022, 36, e13901. [CrossRef]

- Margulies, J.D.; Moorman, F.R.; Goettsch, B.; Axmacher, J.C.; Hinsley, A. Prevalence and perspectives of illegal trade in cacti and succulent plants in the collector community. Conservation Biology 2022, e14030. [CrossRef]

- Chichorro, F.; Urbano, F.; Teixeira, D.; Väre, H.; Pinto, T.; Brummitt, N.; He, X.; Hochkirch, A.; Hyvönen, J.; Kaila, L. Trait-based prediction of extinction risk across terrestrial taxa. Biological Conservation 2022, 274, 109738. [CrossRef]

- Myers, N.; Mittermeier, R.A.; Mittermeier, C.G.; Da Fonseca, G.A.; Kent, J. Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature 2000, 403, 853-858. [CrossRef]

- Mittermeier, R.A.; Turner, W.R.; Larsen, F.W.; Brooks, T.M.; Gascon, C. Global biodiversity conservation: the critical role of hotspots. Biodiversity hotspots: distribution and protection of conservation priority areas 2011, 3-22.

- Gibbs, H.K.; Ruesch, A.S.; Achard, F.; Clayton, M.K.; Holmgren, P.; Ramankutty, N.; Foley, J.A. Tropical forests were the primary sources of new agricultural land in the 1980s and 1990s. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2010, 107, 16732-16737. [CrossRef]

- Bhagwat, T.; Hess, A.; Horning, N.; Khaing, T.; Thein, Z.M.; Aung, K.M.; Aung, K.H.; Phyo, P.; Tun, Y.L.; Oo, A.H. Losing a jewel—Rapid declines in Myanmar’s intact forests from 2002-2014. PloS one 2017, 12, e0176364.

- Webb, E.L.; Jachowski, N.R.; Phelps, J.; Friess, D.A.; Than, M.M.; Ziegler, A.D. Deforestation in the Ayeyarwady Delta and the conservation implications of an internationally-engaged Myanmar. Global Environmental Change 2014, 24, 321-333. [CrossRef]

- Kattelus, M.; Rahaman, M.M.; Varis, O. M yanmar under reform: Emerging pressures on water, energy and food security. In Proceedings of the Natural Resources Forum, 2014; pp. 85-98.

- LaJeunesse Connette, K.J.; Connette, G.; Bernd, A.; Phyo, P.; Aung, K.H.; Tun, Y.L.; Thein, Z.M.; Horning, N.; Leimgruber, P.; Songer, M. Assessment of mining extent and expansion in Myanmar based on freely-available satellite imagery. Remote Sensing 2016, 8, 912. [CrossRef]

- Nicholas, K.M.; Fanzo, J.; MacManus, K. Palm oil in Myanmar: a spatiotemporal study of how industrial farming affects biodiversity loss and the sustainable diet. The FASEB Journal 2017, 31, 788.736-788.736. [CrossRef]

- Prescott, G.W.; Sutherland, W.J.; Aguirre, D.; Baird, M.; Bowman, V.; Brunner, J.; Connette, G.M.; Cosier, M.; Dapice, D.; De Alban, J.D.T. Political transition and emergent forest-conservation issues in Myanmar. Conservation Biology 2017, 31, 1257-1270.

- Gawecka, K.A.; Pedraza, F.; Bascompte, J. Effects of habitat destruction on coevolving metacommunities. Ecology Letters 2022, 25, 2597-2610. [CrossRef]

- Monk, J.D.; Smith, J.A.; Donadío, E.; Perrig, P.L.; Crego, R.D.; Fileni, M.; Bidder, O.; Lambertucci, S.A.; Pauli, J.N.; Schmitz, O.J. Cascading effects of a disease outbreak in a remote protected area. Ecology Letters 2022, 25, 1152-1163.

- Maxwell, S.L.; Cazalis, V.; Dudley, N.; Hoffmann, M.; Rodrigues, A.S.; Stolton, S.; Visconti, P.; Woodley, S.; Kingston, N.; Lewis, E. Area-based conservation in the twenty-first century. Nature 2020, 586, 217-227. [CrossRef]

- Díaz, S.; Settele, J.; Brondízio, E.S.; Ngo, H.T.; Agard, J.; Arneth, A.; Balvanera, P.; Brauman, K.A.; Butchart, S.H.; Chan, K.M. Pervasive human-driven decline of life on Earth points to the need for transformative change. Science 2019, 366, eaax3100. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, A.S.; Andelman, S.J.; Bakarr, M.I.; Boitani, L.; Brooks, T.M.; Cowling, R.M.; Fishpool, L.D.; Da Fonseca, G.A.; Gaston, K.J.; Hoffmann, M. Effectiveness of the global protected area network in representing species diversity. Nature 2004, 428, 640-643. [CrossRef]

- Cooke, R.; Mancini, F.; Boyd, R.J.; Evans, K.L.; Shaw, A.; Webb, T.J.; Isaac, N.J. Protected areas support more species than unprotected areas in Great Britain, but lose them equally rapidly. Biological Conservation 2023, 278, 109884. [CrossRef]

- Rosenzweig, M.L. Species diversity in space and time; Cambridge university press: 1995.

- Cavender-Bares, J.; Schneider, F.D.; Santos, M.J.; Armstrong, A.; Carnaval, A.; Dahlin, K.M.; Fatoyinbo, L.; Hurtt, G.C.; Schimel, D.; Townsend, P.A. Integrating remote sensing with ecology and evolution to advance biodiversity conservation. Nature Ecology & Evolution 2022, 6, 506-519. [CrossRef]

- Gorczynski, D.; Hsieh, C.; Luciano, J.T.; Ahumada, J.; Espinosa, S.; Johnson, S.; Rovero, F.; Santos, F.; Andrianarisoa, M.H.; Astaiza, J.H. Tropical mammal functional diversity increases with productivity but decreases with anthropogenic disturbance. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 2021, 288, 20202098.

- Margules, C.R.; Pressey, R.L. Systematic conservation planning. Nature 2000, 405, 243-253.

- Llorente-Culebras, S.; Ladle, R.J.; Santos, A.M. Publication trends in global biodiversity research on protected areas. Biological Conservation 2023, 281, 109988. [CrossRef]

- Fa, J.E.; Peres, C.A.; Meeuwig, J. Bushmeat exploitation in tropical forests: an intercontinental comparison. Conservation biology 2002, 16, 232-237. [CrossRef]

- Almeida, R.J.; Bonachela, J.A.; Lockwood, J.L. Multiple co-occurring bioeconomic drivers of overexploitation can accelerate rare species extinction risk. Journal of Applied Ecology 2023. [CrossRef]

- Corlett, R.T. The impact of hunting on the mammalian fauna of tropical Asian forests. Biotropica 2007, 39, 292-303. [CrossRef]

- Spencer, K.L.; Deere, N.J.; Aini, M.; Avriandy, R.; Campbell-Smith, G.; Cheyne, S.M.; Gaveau, D.L.; Humle, T.; Hutabarat, J.; Loken, B. Implications of large-scale infrastructure development for biodiversity in Indonesian Borneo. Science of the Total Environment 2023, 866, 161075. [CrossRef]

- Rao, M.; Myint, T.; Zaw, T.; Htun, S. Hunting patterns in tropical forests adjoining the Hkakaborazi National Park, north Myanmar. Oryx 2005, 39, 292-300. [CrossRef]

- Estrada, A.; Garber, P.A.; Gouveia, S.; Fernández-Llamazares, Á.; Ascensão, F.; Fuentes, A.; Garnett, S.T.; Shaffer, C.; Bicca-Marques, J.; Fa, J.E. Global importance of Indigenous Peoples, their lands, and knowledge systems for saving the world’s primates from extinction. Science advances 2022, 8, eabn2927.

- Fordham, D.A.; Brook, B.W. Why tropical island endemics are acutely susceptible to global change. Biodiversity and conservation 2010, 19, 329-342. [CrossRef]

- Strauß, L.; Baker, T.R.; de Lima, R.F.; Afionis, S.; Dallimer, M. Limited integration of biodiversity within climate policy: Evidence from the Alliance of Small Island States. Environmental Science & Policy 2022, 128, 216-227. [CrossRef]

- Roth, M.P. Global organized crime: A 21st century approach; Taylor & Francis: 2017.

- Laurance, W.F.; Carolina Useche, D.; Rendeiro, J.; Kalka, M.; Bradshaw, C.J.; Sloan, S.P.; Laurance, S.G.; Campbell, M.; Abernethy, K.; Alvarez, P. Averting biodiversity collapse in tropical forest protected areas. Nature 2012, 489, 290-294. [CrossRef]

- Clemens, R.S.; Herrod, A.; Weston, M.A. Lines in the mud; revisiting the boundaries of important shorebird areas. Journal for Nature Conservation 2014, 22, 59-67. [CrossRef]

- Clemens, R.; Weston, M.; Haslem, A.; Silcocks, A.; Ferris, J. Identification of significant shorebird areas: thresholds and criteria. Diversity and Distributions 2010, 16, 229-242. [CrossRef]

- Maslo, B.; Zeigler, S.L.; Drake, E.C.; Pover, T.; Plant, N.G. A pragmatic approach for comparing species distribution models to increasing confidence in managing piping plover habitat. Conservation Science and Practice 2020, 2, e150. [CrossRef]

- Chen, I.-C.; Hill, J.K.; Ohlemüller, R.; Roy, D.B.; Thomas, C.D. Rapid range shifts of species associated with high levels of climate warming. Science 2011, 333, 1024-1026. [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, S. Threatened species could be more vulnerable to climate change in tropical countries. Science of The Total Environment 2023, 858, 159989. [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, S.; Irl, S.D.; Beierkuhnlein, C. Predicted climate shifts within terrestrial protected areas worldwide. Nature communications 2019, 10, 4787. [CrossRef]

- Loarie, S.R.; Duffy, P.B.; Hamilton, H.; Asner, G.P.; Field, C.B.; Ackerly, D.D. The velocity of climate change. Nature 2009, 462, 1052-1055. [CrossRef]

- Shipley, B.R.; McGuire, J.L. Disentangling the drivers of continental mammalian endemism. Global Change Biology 2023. [CrossRef]

- Finocchiaro, M.; Médail, F.; Saatkamp, A.; Diadema, K.; Pavon, D.; Meineri, E. Bridging the gap between microclimate and microrefugia: A bottom-up approach reveals strong climatic and biological offsets. Global Change Biology 2023, 29, 1024-1036. [CrossRef]

- Ludovicy, S.; Noroozi, J.; Semenchuk, P.; Moser, D.; Wessely, J.; Talebi, A.; Dullinger, S. Protected area network insufficiently represents climatic niches of endemic plants in a Global Biodiversity Hotspot. Biological Conservation 2022, 275, 109768. [CrossRef]

- Burrows, M.T.; Schoeman, D.S.; Richardson, A.J.; Molinos, J.G.; Hoffmann, A.; Buckley, L.B.; Moore, P.J.; Brown, C.J.; Bruno, J.F.; Duarte, C.M. Geographical limits to species-range shifts are suggested by climate velocity. Nature 2014, 507, 492-495. [CrossRef]

- Carlson, C.J.; Albery, G.F.; Merow, C.; Trisos, C.H.; Zipfel, C.M.; Eskew, E.A.; Olival, K.J.; Ross, N.; Bansal, S. Climate change increases cross-species viral transmission risk. Nature 2022, 607, 555-562. [CrossRef]

- Ward, M.; Saura, S.; Williams, B.; Ramírez-Delgado, J.P.; Arafeh-Dalmau, N.; Allan, J.R.; Venter, O.; Dubois, G.; Watson, J.E. Just ten percent of the global terrestrial protected area network is structurally connected via intact land. Nature communications 2020, 11, 4563. [CrossRef]

- Mills, S.C.; Socolar, J.B.; Edwards, F.A.; Parra, E.; Martínez-Revelo, D.E.; Ochoa Quintero, J.M.; Haugaasen, T.; Freckleton, R.P.; Barlow, J.; Edwards, D.P. High sensitivity of tropical forest birds to deforestation at lower altitudes. Ecology 2023, 104, e3867. [CrossRef]

- Elsen, P.R.; Monahan, W.B.; Merenlender, A.M. Global patterns of protection of elevational gradients in mountain ranges. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2018, 115, 6004-6009. [CrossRef]

- Guisan, A.; Thuiller, W. Predicting species distribution: offering more than simple habitat models. Ecology letters 2005, 8, 993-1009. [CrossRef]

- van Proosdij, A.S.; Sosef, M.S.; Wieringa, J.J.; Raes, N. Minimum required number of specimen records to develop accurate species distribution models. Ecography 2016, 39, 542-552. [CrossRef]

- Elsen, P.R.; Monahan, W.B.; Dougherty, E.R.; Merenlender, A.M. Keeping pace with climate change in global terrestrial protected areas. Science advances 2020, 6, eaay0814. [CrossRef]

- Staude, I.R.; Navarro, L.M.; Pereira, H.M. Range size predicts the risk of local extinction from habitat loss. Global Ecology and Biogeography 2020, 29, 16-25. [CrossRef]

- Bálint, M.; Domisch, S.; Engelhardt, C.; Haase, P.; Lehrian, S.; Sauer, J.; Theissinger, K.; Pauls, S.; Nowak, C. Cryptic biodiversity loss linked to global climate change. Nature climate change 2011, 1, 313-318. [CrossRef]

- Keeton, C.L. King Thebaw and the Ecological Rape of Burma: The Political and Commercial Struggle Between British India and French Indo-China in Burma, 1878-1886; Delhi: Manohar Book Service: 1974.

- Karlsson, M.; Alfredsson, E.; Westling, N. Climate policy co-benefits: a review. Climate Policy 2020, 20, 1-25. [CrossRef]

- Aung, U.M. Policy and practice in Myanmar’s protected area system. Journal of Environmental Management 2007, 84, 188-203. [CrossRef]

- Stebbing, E.P. The forests of India; J. Lane: 1926; Volume 3.

- Bryant, R.L. The Political Ecology of Forestry in Burma, 1824-1994: 1824-1994; University of Hawaii Press: 1997.

- Evans, G.P.E. Big Game Shooting in Upper Burma; Longmans, Green: 1911.

- Burton, R. Game sanctuaries in Burma (pre-1942) with present status of rhinoceros and thamin. Journal of the Bombay natural history society 1951, 49, 729-737.

- Blower, J. Nature conservation in Burma. Office of the FAO Representative, Rangoon, Burma 1980.

- Groombridge, B.; Jenkins, M. Biodiversity data sourcebook. 1994.

- Tan, A.K. Preliminary Assessment of Myanmar’s Environmental Law. APCEL Report: Myanmar. ASEAN Environmental Law (ASEAN 10): Myanmar. http://sunsite. nus. edu. sg 1998.

- Howell, A.H.; Kellogg, R.; Miller, G.S. List of Recent Literature. Journal of Mammalogy 1936, 17, 423-437. [CrossRef]

- Bank, W. World development report 1992: development and the environment; The World Bank: 1992.

- MacKinnon, J.R.; MacKinnon, K. Review of the protected areas system in the Indo-Malayan realm. 1986.

- Leete, F. Reserves and working plans. Indian Forester 1908, 34, 270-280.

- Walker, H. Working-plans in Burma. Indian Forester 1916, 42, 108-118.

- Smith, H. Criminal Law--Right to Waive Jury Trial over the Objection of the State’s Attorney. Kentucky Law Journal 1935, 23, 12.

- Aung, M.; Swe, K.K.; Oo, T.; Moe, K.K.; Leimgruber, P.; Allendorf, T.; Duncan, C.; Wemmer, C. The environmental history of Chatthin Wildlife Sanctuary, a protected area in Myanmar (Burma). Journal of Environmental Management 2004, 72, 205-216. [CrossRef]

- Borrini, G. Beyond fences seeking social sustainability in conservation; [sn]: 1997.

- Tilson, R. Preserving critical habitat: the Minnesota Zoo’s adopt-a-park program. In Proceedings of the Annu conf Am Assoc Zoo Prk Aquar, 1991; pp. 386-390.

- Turnell, S. A survey of microfinance institutions in Burma. Burma Economic Watch 2005, 1, 26-50.

- Sharpe, G.W. Self-guided trails. Interpreting the Environment (pp. 247Á/269). New York: Wiley & Sons 1976.

- McShane, T.O.; Wells, M.P. Getting biodiversity projects to work: towards more effective conservation and development; Columbia University Press: 2004.

- Kamaljit Bawa, S.; Reinmar, S.; Peter Raven, H. Reconciling conservation paradigms. Conservation Biology 2004, 18, 859-860.

- MacKenzie, D.I.; Nichols, J.D.; Lachman, G.B.; Droege, S.; Andrew Royle, J.; Langtimm, C.A. Estimating site occupancy rates when detection probabilities are less than one. Ecology 2002, 83, 2248-2255.

- Gu, W.; Swihart, R.K. Absent or undetected? Effects of non-detection of species occurrence on wildlife–habitat models. Biological conservation 2004, 116, 195-203. [CrossRef]

- Elith*, J.; H. Graham*, C.; P. Anderson, R.; Dudík, M.; Ferrier, S.; Guisan, A.; J. Hijmans, R.; Huettmann, F.; R. Leathwick, J.; Lehmann, A. Novel methods improve prediction of species’ distributions from occurrence data. Ecography 2006, 29, 129-151.

- Hernandez, P.A.; Graham, C.H.; Master, L.L.; Albert, D.L. The effect of sample size and species characteristics on performance of different species distribution modeling methods. Ecography 2006, 29, 773-785. [CrossRef]

- Phillips, S.J.; Anderson, R.P.; Schapire, R.E. Maximum entropy modeling of species geographic distributions. Ecological modelling 2006, 190, 231-259. [CrossRef]

- Phillips, S.J.; Dudík, M.; Schapire, R.E. A maximum entropy approach to species distribution modeling. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the twenty-first international conference on Machine learning, 2004; p. 83.

- Grendár Jr, M.; Grendár, M. Maximum entropy: Clearing up mysteries. Entropy 2001, 3, 58-63.

- Jaynes, E.T. Information theory and statistical mechanics. Physical review 1957, 106, 620. [CrossRef]

- Jaynes, E.T. On the rationale of maximum-entropy methods. Proceedings of the IEEE 1982, 70, 939-952. [CrossRef]

- Golan, A.; Judge, G.; Miller, D. Maximum entropy econometrics: Robust estimation with limited data. 1997.

- Roussev, V. Data fingerprinting with similarity digests. In Proceedings of the Advances in Digital Forensics VI: Sixth IFIP WG 11.9 International Conference on Digital Forensics, Hong Kong, China, January 4-6, 2010, Revised Selected Papers 6, 2010; pp. 207-226.

- Frieden, B.R. Restoring with maximum likelihood and maximum entropy. JOSA 1972, 62, 511-518. [CrossRef]

- Gull, S.; Newton, T. Maximum entropy tomography. Applied optics 1986, 25, 156-160. [CrossRef]

- Merow, C.; Wilson, A.M.; Jetz, W. Integrating occurrence data and expert maps for improved species range predictions. Global Ecology and Biogeography 2017, 26, 243-258. [CrossRef]

- Herkt, K.M.B.; Skidmore, A.K.; Fahr, J. Macroecological conclusions based on IUCN expert maps: A call for caution. Global Ecology and Biogeography 2017, 26, 930-941. [CrossRef]

- Sagarin, R.D.; Gaines, S.D.; Gaylord, B. Moving beyond assumptions to understand abundance distributions across the ranges of species. Trends in ecology & evolution 2006, 21, 524-530. [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.L. Research and societal benefits of the Global Biodiversity Information Facility. BioScience 2004, 54, 485-486. [CrossRef]

- McPherson, J.M.; Jetz, W. Type and spatial structure of distribution data and the perceived determinants of geographical gradients in ecology: the species richness of African birds. Global Ecology and Biogeography 2007, 16, 657-667. [CrossRef]

- Fourcade, Y. Comparing species distributions modelled from occurrence data and from expert-based range maps. Implication for predicting range shifts with climate change. Ecological Informatics 2016, 36, 8-14. [CrossRef]

- Alhajeri, B.H.; Fourcade, Y. High correlation between species-level environmental data estimates extracted from IUCN expert range maps and from GBIF occurrence data. Journal of Biogeography 2019, 46, 1329-1341. [CrossRef]

- Girardin, C.A.; Jenkins, S.; Seddon, N.; Allen, M.; Lewis, S.L.; Wheeler, C.E.; Griscom, B.W.; Malhi, Y. Nature-based solutions can help cool the planet—if we act now. Nature 2021, 593, 191-194. [CrossRef]

- Hoegh-Guldberg, O.; Jacob, D.; Taylor, M.; Guillén Bolaños, T.; Bindi, M.; Brown, S.; Camilloni, I.A.; Diedhiou, A.; Djalante, R.; Ebi, K. The human imperative of stabilizing global climate change at 1.5 C. Science 2019, 365, eaaw6974. [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.; Arneth, A.; Barnes, D.K.; Ichii, K.; Marquet, P.A.; Popp, A.; Pörtner, H.O.; Rogers, A.D.; Scholes, R.J.; Strassburg, B. How do we best synergize climate mitigation actions to co-benefit biodiversity? Global Change Biology 2022, 28, 2555-2577.

- Wemmer, C.; Kress, W.; Zug, G. Smithsonian collaborations in Myanmar: a compilation of projects and activities between 1994–2003. Smithsonian Institution, Washington 2004.

- Shepherd, C.R.; Nijman, V. Elephant and ivory trade in Myanmar; Citeseer: 2008.

- Woodroffe, R.; Thirgood, S.; Rabinowitz, A. People and wildlife, conflict or co-existence?; Cambridge University Press: 2005; Volume 9.

- Woods, K. Intersections of land grabs and climate change mitigation strategies in Myanmar as a (post-) war state of conflict. MOSAIC Working Paper Series 2015, 3.

- Platt, S.G.; Lwin, T.; Win, N.; Aung, H.L.; Platt, K.; Rainwater, T.R. An interview-based survey to determine the conservation status of softshell turtles (Reptilia: Trionychidae) in the Irrawaddy Dolphin Protected Area, Myanmar. Journal of Threatened Taxa 2017, 9, 10998-11008. [CrossRef]

- Kelly, D.S. Habitat Selection in Declining Elephant Populations of Alaungdaw Kathapa National Park, Myanmar (Burma). George Mason University, 2005.

| WDPA_ID |

Name |

Type |

IUCN Category |

Establishment Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1235 | Kyauk Pan Taung Wildlife Sanctuary | Wildlife Sanctuary | IV | 2013 |

| 1236 | Shwesettaw Wildlife Sanctuary | Wildlife Sanctuary | IV | 1940 |

| 1237 | Shwe-U-Daung Wildlife Sanctuary | Wildlife Sanctuary | IV | 1927 |

| 1238 | Minwuntaung Wildlife Sanctuary | Wildlife Sanctuary | IV | 1971 |

| 1239 | Kaylatha Wildlife Sanctuary | Wildlife Sanctuary | IV | 1942 |

| 8005 | Pidaung Wildlife Sanctuary | Wildlife Sanctuary | IV | 1927 |

| 8006 | Chatthin Wildlife Sanctuary | Wildlife Sanctuary | IV | 1941 |

| 8008 | Wetthikan Bird Sanctuary | Wildlife Sanctuary | IV | 1939 |

| 8009 | Taunggyi Bird Sanctuary | Wildlife Sanctuary | IV | 1920 |

| 8010 | Kahilu Wildlife Sanctuary | Wildlife Sanctuary | IV | 1928 |

| 8011 | Mulayit Wildlife Sanctuary | Wildlife Sanctuary | IV | 1935 |

| 8012 | Moscos Islands Wildlife Sanctuary | Wildlife Sanctuary | IV | 1927 |

| 8013 | Thamihla Kyun Wildlife Sanctuary | Wildlife Sanctuary | IV | 1970 |

| 8022 | Hlawga Park | Nature Park | IV | 1989 |

| 8024 | Moeyungyi Wetland Wildlife Sanctuary | Wildlife Sanctuary | IV | 1988 |

| 8027 | Natmataung National Park | Wildlife Sanctuary and ASEAN Heritage Park | II | 2010 |

| 8029 | Popa Mountain Park | Nature Park | II | 1989 |

| 8033 | Meinmahla Kyun Wildlife Sanctuary | Wildlife Sanctuary and ASEAN Heritage Park | IV | 1993 |

| 8035 | Lampi Marine National Park | Marine National Park and ASEAN Heritage Park | II | 1996 |

| 11752 | Alaungdaw Katthapa National Park | National Park and ASEAN Heritage Park | II | 1989 |

| 11813 | Inlay Lake Wildlife Sanctuary | Wildlife Sanctuary and ASEAN Heritage Park | IV | 1985 |

| 312896 | Loimwe Protected Area | Nature Reserve | IV | 1996 |

| 312897 | Parsar Protected Area | National Park | IV | 1996 |

| 312898 | Kyeikhtiyoe Wildlife Sanctuary | Wildlife Sanctuary | III | 2001 |

| 312899 | Lawkananda Sanctuary | Wildlife Sanctuary | IV | 1995 |

| 312900 | Rakhine Yoma Elephant Range | Wildlife Sanctuary | IV | 2002 |

| 312902 | Panlaung and Padalin Cave Wildlife Sanctuary | Wildlife Sanctuary | IV | 2002 |

| 312903 | Minsontaung Wildlife Sanctuary | Wildlife Sanctuary | IV | 2001 |

| 312904 | Hukaung Valley Wildlife Sanctuary (extension) | Wildlife Sanctuary | IV | 2010 |

| 312906 | Hponkanrazi Wildlife Sanctuary | Wildlife Sanctuary | IV | 2003 |

| 312910 | Bumpha Bum Wildife Sanctuary | Wildlife Sanctuary | IV | 2004 |

| 312911 | Pyin-O-Lwin Bird Sanctuary | Wildlife Sanctuary | IV | 1927 |

| 312912 | Htamanthi Wildlife Sanctuary | Wildlife Sanctuary and ASEAN Heritage Park | IV | 1974 |

| 555547903 | Taninthayi Nature Reserve | Nature Reserve | Ia | 2005 |

| 555624187 | Indawgyi Wildlife Sanctuary | Wildlife Sanctuary and ASEAN Heritage Park | IV | 2004 |

| 555624679 | Meinmahla Kyun Wildlife Sanctuary | Ramsar Site, Wetland of International Importance | Not Reported | 2017 |

| 555624853 | Gulf of Mottama | Ramsar Site, Wetland of International Importance | Not Reported | 2017 |

| 555626065 | Chungponkan Wildlife Sanctuary | Wildlife Sanctuary | IV | 2013 |

| 555626071 | Bwe Par Taung National Park | National Park | II | 2019 |

| 555626073 | Hkakaborazi National Park | National Park and ASEAN Heritage Park | II | 1998 |

| 555626074 | Hugaung Valley Wildlife Sanctuary | Wildlife Sanctuary | IV | 2004 |

| 555626075 | Inkhain Bum National Park | National Park | II | 2017 |

| 555626076 | North Zamrari Wildlife Sanctuary | Wildlife Sanctuary | IV | 2014 |

| 555626077 | Inlay Wetland W.S | UNESCO-MAB Biosphere Reserve | Not Applicable | 2015 |

| 555626078 | Indawgyi W.S | UNESCO-MAB Biosphere Reserve | Not Applicable | 2017 |

| 555626080 | Moyungyi Wetland W.S | Ramsar Site, Wetland of International Importance | Not Reported | 2004 |

| 555626095 | Indawgyi Wildlife Sanctuary | Ramsar Site, Wetland of International Importance | Not Reported | 2016 |

| 555637436 | Inlay Lake Ramsar Site | Ramsar Site, Wetland of International Importance | V | 2018 |

| 555651506 | Hpabaubg Taung Managed Nature Reserve | Nature Reserve | Not Reported | 2018 |

| 555651507 | Se Taung Wildlife Sanctuary | Wildlife Sanctuary | Not Reported | 2018 |

| 555651508 | Htaungwi Taung Geo-features Significant Area | Geo-features Significant Area | Not Reported | 2018 |

| 555703462 | Emawbum National Park | National Park | II | 2020 |

| 555703463 | Ichasaya Cave Wildlife Sanctuary | Wildlife Sanctuary | III | 2019 |

| Species | Annual Average Temperature | Daily Range of Average Temperature | Isotherm | Seasonal Variation Coefficient of Temperature | Highest Temperature in the Hottest Month | The Lowest Temperature in the Coldest Month | Annual Temperature Range | The Average Temperature of the Wettest Quarter | Average Temperature of the Driest Quarter | The Average Temperature of the Warmest Quarter | Average Temperature of the Coldest Quarter | Annual Precipitation | Precipitation in the Wettest Month | Precipitation in the Driest month | Seasonal Variation of Precipitation | Precipitation in the Wettest Quarter | Precipitation in the Driest Quarter | Precipitation in the Warmest Quarter | Precipitation in the Coldest Quarter |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aceros nipalensis | 28.18 | 0.57 | 1.29 | 2.10 | 1.69 | 0.04 | 5.40 | 5.82 | 0.05 | 0.64 | 0.94 | 1.46 | 4.92 | 15.54 | 2.23 | 16.67 | 0.70 | 10.17 | 1.58 |

| Ailurus fulgens | 4.91 | 1.78 | 1.15 | 2.68 | 3.00 | 2.31 | 2.42 | 57.88 | 2.22 | 1.72 | 0.85 | 0.27 | 0.53 | 10.05 | 1.18 | 3.32 | 3.43 | 0.05 | 0.25 |

| Aonyx cinereus | 13.39 | 2.17 | 5.76 | 14.55 | 1.79 | 0.66 | 0.63 | 0.34 | 0.09 | 1.41 | 0.28 | 15.68 | 0.91 | 4.70 | 9.81 | 4.51 | 2.32 | 11.42 | 9.58 |

| Aquila heliaca | 30.75 | 1.25 | 3.17 | 5.14 | 0.92 | 0.00 | 7.77 | 20.92 | 0.22 | 0.05 | 0.44 | 5.30 | 4.35 | 1.69 | 0.99 | 4.55 | 5.99 | 4.48 | 2.04 |

| Arborophila charltonii | 0.01 | 2.75 | 23.24 | 36.08 | 1.27 | 0.00 | 0.24 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.20 | 0.07 | 2.39 | 0.00 | 5.15 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 6.79 | 0.18 | 21.57 |

| Arctictis binturong | 6.80 | 1.61 | 2.16 | 4.01 | 0.59 | 0.37 | 3.69 | 5.01 | 0.18 | 0.68 | 0.72 | 11.54 | 0.63 | 0.82 | 4.42 | 31.95 | 16.41 | 5.03 | 3.37 |

| Ardea insignis | 0.03 | 0.75 | 12.13 | 23.57 | 0.86 | 0.07 | 0.31 | 6.36 | 0.00 | 0.21 | 0.26 | 0.11 | 0.43 | 26.34 | 1.96 | 3.55 | 0.01 | 1.76 | 21.29 |

| Asarcornis scutulata | 0.55 | 2.28 | 8.35 | 8.05 | 2.01 | 0.28 | 6.02 | 6.39 | 0.09 | 0.23 | 0.05 | 7.55 | 1.81 | 0.08 | 37.18 | 12.00 | 0.37 | 1.54 | 5.18 |

| Aythya baeri | 0.35 | 4.50 | 7.92 | 31.60 | 0.88 | 4.80 | 19.99 | 4.20 | 2.44 | 0.19 | 0.51 | 1.95 | 1.07 | 1.37 | 2.14 | 0.53 | 2.14 | 1.86 | 11.53 |

| Balaenoptera musculus | 1.67 | 1.93 | 0.05 | 2.73 | 0.88 | 0.03 | 0.62 | 3.15 | 0.79 | 1.00 | 6.48 | 1.08 | 2.13 | 1.03 | 0.07 | 73.50 | 1.55 | 0.44 | 0.86 |

| Bos gaurus | 33.19 | 0.05 | 2.42 | 4.56 | 0.12 | 1.07 | 1.46 | 3.45 | 4.79 | 0.00 | 1.31 | 29.61 | 1.03 | 0.69 | 0.95 | 2.38 | 0.90 | 4.16 | 7.87 |

| Bos javanicus | 0.08 | 1.46 | 6.28 | 17.16 | 1.13 | 0.00 | 10.16 | 2.07 | 1.82 | 0.73 | 0.01 | 3.10 | 3.11 | 0.67 | 13.40 | 5.77 | 5.70 | 5.30 | 22.06 |

| Bubalus arnee | 0.00 | 0.21 | 1.62 | 4.23 | 0.19 | 0.00 | 0.20 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 6.80 | 13.67 | 0.00 | 3.04 | 0.61 | 69.31 | 0.09 |

| Budorcas taxicolor | 1.15 | 7.90 | 5.19 | 13.16 | 0.94 | 0.33 | 0.54 | 3.42 | 0.54 | 0.08 | 1.32 | 0.36 | 0.57 | 57.28 | 1.35 | 0.60 | 0.98 | 1.26 | 3.05 |

| Calidris pygmaea | 0.24 | 1.06 | 1.66 | 23.14 | 0.26 | 1.81 | 2.99 | 0.92 | 1.41 | 0.90 | 5.78 | 4.39 | 2.37 | 0.05 | 1.79 | 50.24 | 0.65 | 0.00 | 0.34 |

| Calidris tenuirostris | 0.64 | 0.14 | 0.02 | 3.85 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.32 | 0.55 | 0.04 | 0.22 | 0.00 | 0.39 | 49.87 | 0.19 | 30.59 | 1.53 | 0.75 | 10.70 | 0.01 |

| Chrysomma altirostre | 0.45 | 0.98 | 0.01 | 2.24 | 28.82 | 0.73 | 0.42 | 0.35 | 15.27 | 1.27 | 1.16 | 0.03 | 6.71 | 0.06 | 7.37 | 29.77 | 0.81 | 2.65 | 0.90 |

| Ciconia episcopus | 0.00 | 0.06 | 29.97 | 18.47 | 0.23 | 0.01 | 0.75 | 0.04 | 1.56 | 0.00 | 1.61 | 1.59 | 0.02 | 0.58 | 5.35 | 0.10 | 1.11 | 2.37 | 36.15 |

| Clanga clanga | 13.65 | 0.78 | 6.48 | 22.91 | 0.93 | 0.00 | 2.84 | 1.36 | 0.16 | 0.28 | 0.03 | 6.12 | 0.49 | 1.41 | 12.47 | 0.59 | 0.15 | 2.38 | 26.96 |

| Clanga hastata | 0.31 | 1.23 | 5.27 | 15.61 | 1.65 | 0.04 | 5.64 | 2.45 | 2.15 | 0.02 | 0.54 | 0.91 | 1.05 | 0.20 | 0.17 | 3.59 | 56.90 | 0.66 | 1.62 |

| Columba punicea | 0.00 | 0.12 | 0.14 | 10.71 | 11.14 | 0.16 | 0.23 | 0.48 | 2.18 | 0.31 | 0.13 | 0.02 | 0.59 | 0.02 | 0.99 | 46.61 | 0.09 | 21.90 | 4.18 |

| Cuon alpinus | 1.42 | 4.58 | 31.37 | 8.33 | 1.59 | 3.36 | 0.25 | 0.99 | 0.22 | 1.05 | 3.58 | 1.59 | 1.33 | 0.89 | 20.62 | 0.08 | 17.34 | 0.88 | 0.54 |

|

Elephas maximus |

16.01 | 0.64 | 7.54 | 22.93 | 0.45 | 0.08 | 0.98 | 2.63 | 2.37 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 20.06 | 2.16 | 0.17 | 10.18 | 0.01 | 9.19 | 4.00 | 0.58 |

| Emberiza aureola | 13.04 | 3.56 | 5.86 | 9.03 | 4.89 | 1.30 | 0.45 | 1.15 | 4.42 | 4.03 | 19.96 | 0.19 | 0.77 | 0.87 | 8.82 | 0.00 | 0.24 | 1.45 | 19.97 |

| Grus antigone | 0.03 | 1.46 | 8.19 | 38.61 | 0.04 | 0.47 | 9.65 | 0.12 | 0.49 | 0.03 | 0.13 | 2.91 | 0.45 | 4.86 | 1.64 | 0.27 | 7.27 | 0.55 | 22.83 |

| Gyps bengalensis | 0.00 | 0.19 | 2.65 | 27.05 | 1.08 | 0.01 | 0.44 | 1.58 | 0.08 | 1.32 | 34.11 | 16.66 | 1.34 | 0.68 | 0.48 | 0.40 | 1.21 | 1.97 | 8.75 |

| Gyps tenuirostris | 0.57 | 0.69 | 10.50 | 27.90 | 0.36 | 4.86 | 10.44 | 0.33 | 0.59 | 1.36 | 15.28 | 0.72 | 0.61 | 8.93 | 5.48 | 0.21 | 1.02 | 9.45 | 0.72 |

| Haliaeetus leucoryphus | 0.00 | 0.04 | 42.37 | 4.07 | 0.60 | 0.03 | 3.10 | 2.42 | 5.47 | 0.67 | 2.26 | 5.24 | 1.31 | 0.74 | 0.37 | 0.11 | 1.71 | 1.76 | 27.74 |

| Halophila beccarii | 0.80 | 2.71 | 0.08 | 1.41 | 0.54 | 1.89 | 1.39 | 2.32 | 3.64 | 0.08 | 8.55 | 1.41 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 1.90 | 71.27 | 0.29 | 0.22 | 1.48 |

| Helarctos malayanus | 8.10 | 6.37 | 2.95 | 2.74 | 0.55 | 0.00 | 0.75 | 6.42 | 0.32 | 19.67 | 0.27 | 28.41 | 0.33 | 0.92 | 0.59 | 13.26 | 1.07 | 3.53 | 3.75 |

| Heliopais personatus | 0.65 | 0.87 | 13.04 | 9.46 | 2.44 | 0.13 | 1.80 | 0.85 | 1.07 | 1.61 | 0.00 | 1.65 | 0.11 | 1.31 | 1.09 | 3.50 | 3.25 | 1.51 | 55.66 |

| Heritiera fomes | 1.23 | 1.88 | 0.04 | 0.69 | 0.08 | 1.64 | 2.18 | 2.45 | 0.08 | 1.16 | 7.95 | 1.07 | 2.34 | 1.09 | 1.61 | 72.69 | 0.20 | 0.35 | 1.29 |

| Hoolock hoolock | 0.14 | 24.33 | 11.09 | 2.97 | 0.90 | 0.79 | 0.79 | 1.78 | 0.51 | 0.00 | 9.58 | 0.38 | 1.90 | 4.14 | 36.29 | 0.00 | 2.55 | 0.84 | 1.04 |

| Hoolock leuconedys | 1.85 | 0.82 | 7.80 | 59.86 | 1.83 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 7.21 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 1.00 | 0.71 | 1.70 | 1.24 | 12.89 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.73 | 1.22 |

| Hydrornis gurneyi | 2.59 | 0.22 | 18.78 | 44.27 | 0.11 | 0.19 | 0.93 | 0.29 | 6.70 | 0.00 | 0.16 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 7.72 | 4.84 | 0.95 | 11.37 | 0.00 | 0.82 |

| Hylobates lar | 0.00 | 0.99 | 38.52 | 14.09 | 1.12 | 0.00 | 0.17 | 19.11 | 0.02 | 2.18 | 0.40 | 1.31 | 0.18 | 2.69 | 0.59 | 6.76 | 4.23 | 6.71 | 0.92 |

| Leptoptilos dubius | 0.00 | 12.73 | 7.10 | 40.32 | 0.79 | 0.00 | 0.30 | 6.65 | 4.51 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.31 | 2.73 | 0.00 | 1.19 | 19.57 | 1.71 | 2.08 | 0.01 |

| Leptoptilos javanicus | 0.12 | 0.56 | 23.21 | 17.27 | 0.36 | 0.53 | 0.31 | 0.73 | 0.63 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 1.49 | 0.47 | 0.98 | 9.74 | 0.33 | 0.05 | 1.23 | 41.99 |

| Lophophorus sclateri | 20.53 | 11.21 | 0.99 | 1.20 | 1.00 | 0.62 | 0.00 | 3.06 | 1.00 | 0.24 | 6.66 | 0.38 | 0.07 | 41.75 | 2.74 | 0.10 | 0.66 | 0.97 | 6.81 |

| Lutra sumatrana | 2.06 | 3.85 | 1.38 | 2.91 | 1.07 | 0.19 | 2.01 | 8.14 | 0.07 | 0.30 | 0.18 | 3.68 | 0.27 | 18.48 | 0.13 | 2.11 | 1.66 | 31.19 | 20.34 |

| Lutrogale perspicillata | 9.82 | 0.82 | 2.12 | 38.93 | 0.14 | 0.11 | 2.38 | 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.32 | 2.09 | 0.35 | 2.94 | 2.64 | 1.88 | 0.19 | 3.29 | 31.69 |

| Macaca arctoides | 1.40 | 6.64 | 2.30 | 6.57 | 0.89 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 6.76 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 3.78 | 5.66 | 1.08 | 2.57 | 6.81 | 33.13 | 6.91 | 2.71 | 12.74 |

| Macaca leonina | 24.93 | 0.07 | 4.70 | 15.86 | 1.73 | 0.00 | 1.43 | 4.43 | 0.42 | 0.14 | 0.98 | 24.99 | 0.38 | 0.41 | 5.21 | 2.50 | 0.19 | 2.32 | 9.32 |

| Magnolia gustavii | 9.40 | 0.65 | 31.96 | 29.50 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 1.95 | 6.56 | 4.89 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 1.07 | 2.32 | 0.08 | 0.34 | 3.61 | 5.66 | 0.27 | 1.64 |

| Magnolia nitida | 6.10 | 0.04 | 18.57 | 9.81 | 1.31 | 0.41 | 0.08 | 3.03 | 0.23 | 2.26 | 6.16 | 7.08 | 0.21 | 18.68 | 10.01 | 0.51 | 3.53 | 2.83 | 9.14 |

| Magnolia rostrata | 17.50 | 4.63 | 15.32 | 3.68 | 1.35 | 0.61 | 0.48 | 2.78 | 1.27 | 1.24 | 1.23 | 0.03 | 0.24 | 38.69 | 0.94 | 0.31 | 2.50 | 1.61 | 5.60 |

| Manis javanica | 6.65 | 1.14 | 1.86 | 53.79 | 1.51 | 0.17 | 1.86 | 6.03 | 11.10 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.15 | 1.24 | 1.06 | 0.26 | 0.95 | 2.83 | 8.02 | 1.23 |

| Manis pentadactyla | 0.00 | 0.10 | 1.99 | 10.03 | 0.97 | 0.05 | 1.10 | 1.10 | 0.31 | 0.06 | 49.67 | 18.25 | 0.51 | 0.65 | 1.67 | 0.11 | 2.52 | 1.83 | 9.08 |

| Mergus squamatus | 0.46 | 11.26 | 2.84 | 4.93 | 0.37 | 0.02 | 1.55 | 15.28 | 0.64 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 9.46 | 0.02 | 0.63 | 8.02 | 1.64 | 4.11 | 38.08 | 0.67 |

| Moschus fuscus | 36.81 | 2.89 | 11.96 | 4.73 | 0.04 | 0.32 | 0.91 | 2.33 | 2.15 | 1.54 | 3.93 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 16.82 | 1.42 | 0.90 | 3.77 | 0.74 | 8.70 |

| Mulleripicus pulverulentus | 11.19 | 1.59 | 5.05 | 31.97 | 0.97 | 0.67 | 1.40 | 0.14 | 2.18 | 0.82 | 3.35 | 2.59 | 0.76 | 1.90 | 17.09 | 0.31 | 0.66 | 4.00 | 13.35 |

| Naemorhedus baileyi | 29.66 | 1.06 | 38.47 | 0.97 | 1.50 | 1.63 | 0.10 | 2.25 | 3.16 | 2.43 | 0.18 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 13.22 | 1.95 | 0.99 | 0.01 | 0.36 | 2.03 |

| Neofelis nebulosa | 29.69 | 0.71 | 8.66 | 8.57 | 1.24 | 0.00 | 2.23 | 1.60 | 0.40 | 0.16 | 2.94 | 13.69 | 1.60 | 2.75 | 1.67 | 11.27 | 1.77 | 4.30 | 6.76 |

| Neophocaena phocaenoides | 2.81 | 2.19 | 0.02 | 2.76 | 0.01 | 3.03 | 1.95 | 2.08 | 2.36 | 1.04 | 0.50 | 2.52 | 4.19 | 0.89 | 0.03 | 70.17 | 1.73 | 0.37 | 1.34 |

| Nisaetus nanus | 0.13 | 3.15 | 18.32 | 26.37 | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.85 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 5.22 | 0.16 | 0.36 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 5.13 | 0.06 | 40.04 |

| Nycticebus bengalensis | 12.39 | 0.87 | 5.52 | 10.12 | 1.06 | 0.00 | 2.22 | 3.03 | 0.29 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 33.26 | 1.10 | 0.79 | 6.84 | 2.54 | 0.22 | 4.18 | 15.52 |

| Orcaella brevirostris | 7.30 | 0.45 | 1.89 | 4.04 | 0.34 | 0.02 | 0.50 | 48.81 | 0.92 | 1.74 | 0.73 | 4.64 | 1.67 | 0.86 | 6.96 | 0.49 | 3.01 | 7.68 | 7.94 |

| Otus sagittatus | 0.00 | 2.22 | 9.48 | 63.54 | 1.52 | 0.51 | 0.07 | 6.14 | 2.49 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.33 | 0.20 | 0.44 | 0.33 | 9.85 | 1.31 | 1.15 | 0.22 |

| Panthera tigris | 0.00 | 2.73 | 3.17 | 5.82 | 0.63 | 0.00 | 6.84 | 4.58 | 3.88 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 6.56 | 0.76 | 8.21 | 0.85 | 1.41 | 2.58 | 38.47 | 13.45 |

| Pavo muticus | 5.25 | 9.71 | 7.16 | 24.23 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.55 | 0.24 | 0.47 | 0.39 | 1.11 | 1.59 | 0.13 | 1.31 | 0.53 | 2.53 | 2.62 | 0.38 | 41.70 |

| Petinomys setosus | 12.67 | 2.26 | 6.42 | 2.28 | 1.32 | 0.09 | 0.01 | 2.11 | 0.14 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 1.00 | 2.11 | 1.83 | 1.11 | 3.80 | 3.36 | 58.81 | 0.69 |

| Petinomys vordermanni | 3.61 | 3.10 | 20.10 | 46.87 | 1.24 | 0.17 | 0.86 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 6.51 | 0.00 | 9.60 | 3.37 | 0.28 | 2.95 | 1.10 | 0.00 |

| Prionailurus viverrinus | 0.29 | 1.56 | 2.02 | 20.40 | 3.38 | 0.35 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.22 | 0.10 | 0.30 | 0.00 | 5.07 | 0.18 | 0.37 | 45.31 | 12.77 | 7.55 | 0.13 |

| Rhinopithecus strykeri | 10.81 | 2.05 | 12.00 | 0.19 | 0.00 | 0.18 | 0.00 | 17.44 | 2.82 | 0.00 | 7.13 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 3.33 | 2.80 | 2.45 | 4.31 | 0.00 | 34.46 |

| Rhyticeros subruficollis | 2.80 | 1.47 | 2.20 | 63.32 | 1.50 | 0.01 | 0.13 | 7.07 | 2.74 | 0.12 | 0.24 | 4.55 | 0.84 | 1.32 | 3.41 | 4.71 | 2.13 | 0.89 | 0.54 |

| Rucervus eldii | 0.04 | 2.33 | 2.92 | 11.96 | 0.78 | 2.23 | 1.19 | 0.67 | 1.11 | 3.57 | 0.22 | 0.00 | 2.07 | 1.82 | 6.39 | 1.01 | 16.45 | 0.96 | 44.30 |

| Rusa unicolor | 12.99 | 1.06 | 6.87 | 14.33 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 2.51 | 2.50 | 0.28 | 1.33 | 1.49 | 7.18 | 1.65 | 1.53 | 18.06 | 0.72 | 0.40 | 1.81 | 24.29 |

| Rynchops albicollis | 1.44 | 8.78 | 5.55 | 10.10 | 1.46 | 0.00 | 2.50 | 1.01 | 1.00 | 0.58 | 0.51 | 3.03 | 0.06 | 1.75 | 1.28 | 0.13 | 1.41 | 4.30 | 55.10 |

| Sarcogyps calvus | 0.00 | 10.08 | 3.69 | 3.69 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.69 | 3.01 | 0.41 | 0.04 | 41.17 | 7.64 | 3.76 | 0.14 | 1.95 | 12.91 | 6.98 | 2.58 | 1.16 |

| Sitta formosa | 36.89 | 1.30 | 1.48 | 8.04 | 0.55 | 0.00 | 3.44 | 12.84 | 0.16 | 0.01 | 0.65 | 7.98 | 8.28 | 5.68 | 1.21 | 0.41 | 3.68 | 5.77 | 1.62 |

| Sitta magna | 18.21 | 21.66 | 0.98 | 18.11 | 1.05 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 20.38 | 0.62 | 0.00 | 0.16 | 6.77 | 0.04 | 2.46 | 0.58 | 5.22 | 1.25 | 2.40 | 0.09 |

| Sitta victoriae | 0.13 | 1.93 | 0.00 | 6.97 | 0.42 | 1.42 | 0.00 | 46.83 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 21.32 | 0.00 | 0.49 | 0.01 | 20.26 | 0.19 | 0.00 |

| Sonneratia griffithii | 1.56 | 1.91 | 0.15 | 1.66 | 0.70 | 2.40 | 1.53 | 2.68 | 0.35 | 0.05 | 6.16 | 1.30 | 1.91 | 1.12 | 1.04 | 73.86 | 0.15 | 0.58 | 0.87 |

| Stachyris oglei | 0.60 | 0.00 | 42.29 | 1.85 | 0.53 | 0.58 | 0.01 | 6.99 | 0.76 | 0.08 | 2.56 | 1.41 | 0.05 | 30.86 | 2.28 | 0.05 | 0.84 | 4.72 | 3.53 |

| Sterna acuticauda | 2.71 | 0.30 | 13.10 | 6.90 | 1.28 | 0.02 | 0.17 | 20.23 | 0.62 | 3.49 | 0.49 | 0.61 | 3.28 | 0.16 | 9.63 | 0.09 | 1.12 | 5.17 | 30.63 |

| Tapirus indicus | 9.61 | 1.72 | 27.67 | 47.93 | 1.28 | 0.03 | 0.18 | 1.54 | 3.10 | 0.12 | 0.01 | 2.76 | 0.22 | 0.51 | 0.26 | 1.65 | 0.94 | 0.46 | 0.04 |

| Trachypithecus germaini | 0.33 | 2.21 | 39.06 | 8.10 | 0.31 | 0.00 | 12.43 | 0.90 | 0.03 | 0.21 | 0.44 | 1.21 | 16.72 | 0.14 | 0.47 | 13.50 | 3.51 | 0.40 | 0.02 |

| Trachypithecus phayrei | 0.89 | 1.80 | 16.14 | 19.63 | 0.66 | 0.00 | 2.08 | 0.37 | 1.03 | 1.79 | 0.87 | 2.63 | 0.23 | 0.98 | 1.46 | 2.25 | 2.40 | 1.69 | 43.11 |

| Trachypithecus pileatus | 0.00 | 17.07 | 11.97 | 27.83 | 1.79 | 0.00 | 0.53 | 2.27 | 0.57 | 0.24 | 0.44 | 0.20 | 0.35 | 1.48 | 30.68 | 0.55 | 1.56 | 0.68 | 1.79 |

| Trachypithecus shortridgei | 25.91 | 1.69 | 3.36 | 4.02 | 0.90 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 2.89 | 0.05 | 0.77 | 0.44 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 18.13 | 1.52 | 0.00 | 3.36 | 0.71 | 36.25 |

| Tragopan blythii | 35.69 | 42.80 | 0.07 | 0.61 | 0.14 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 10.67 | 0.21 | 0.12 | 0.53 | 4.02 | 0.36 | 0.69 | 0.67 | 0.00 | 0.14 | 1.44 | 1.71 |

| Treron capellei | 0.14 | 0.18 | 0.90 | 57.45 | 0.01 | 1.29 | 1.41 | 0.28 | 0.95 | 0.12 | 0.09 | 1.58 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 6.44 | 13.13 | 15.59 | 0.41 | 0.00 |

| Tringa guttifer | 0.00 | 0.00 | 4.38 | 20.72 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 1.10 | 0.00 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.29 | 62.56 | 0.00 | 7.09 | 1.35 | 0.00 |

| Turdus feae | 0.00 | 0.01 | 2.43 | 64.68 | 0.18 | 2.18 | 0.20 | 1.15 | 0.01 | 0.54 | 0.28 | 12.12 | 0.03 | 1.01 | 3.23 | 0.08 | 1.10 | 3.23 | 7.54 |

| Ursus thibetanus | 12.97 | 1.14 | 2.56 | 5.33 | 0.60 | 0.29 | 1.09 | 1.86 | 0.09 | 3.46 | 1.63 | 45.23 | 0.27 | 0.80 | 3.44 | 12.21 | 0.47 | 1.03 | 5.51 |

| Viverra megaspila | 8.37 | 2.11 | 8.52 | 11.85 | 2.57 | 14.97 | 2.23 | 2.82 | 4.97 | 7.09 | 0.57 | 1.25 | 0.88 | 0.83 | 11.63 | 0.16 | 0.12 | 3.36 | 15.71 |

| Species | Current | SSP126 | SSP245 | SSP585 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lutra sumatrana | 72.75% | 67.05% (-7.84%) |

59.91% (-17.65%) |

0.22% (-99.70%) |

| Sitta victoriae | 67.87% | 93.61% (+37.92%) |

extinction (NA) |

extinction (NA) |

| Bubalus arnee | 67.33% | 54.03% (-19.76%) |

53.53% (-20.50%) |

0.00% (-100.00%) |

| Stachyris oglei | 55.17% | 64.66% (+17.20%) |

30.58% (-44.57%) |

10.45% (-81.05%) |

| Ailurus fulgens | 51.07% | 17.57% (-65.61%) |

24.19% (-52.63%) |

19.75% (-61.33%) |

| Naemorhedus baileyi | 51.07% | 31.57% (-38.17%) |

27.57% (-46.02%) |

6.72% (-86.85%) |

| Panthera tigris | 41.27% | 59.20% (+43.45%) |

56.24% (+36.29%) |

1.86% (-95.49%) |

| Rhinopithecus strykeri | 38.94% | 16.59% (-57.41%) |

2.03% (-94.80%) |

extinction (NA) |

| Petinomys setosus | 38.18% | 0.00% (-100.00%) |

0.00% (-100.00%) |

0.00% (-100.00%) |

| Moschus fuscus | 36.42% | 17.22% (-52.73%) |

7.88% (-78.36%) |

5.21% (-85.69%) |

| Magnolia rostrata | 36.05% | 29.36% (-18.55%) |

18.31% (-49.20%) |

4.94% (-86.31%) |

| Budorcas taxicolor | 33.84% | 28.57% (-15.58%) |

16.65% (-50.79%) |

3.48% (-89.73%) |

| Lophophorus sclateri | 32.01% | 23.14% (-27.72%) |

13.70% (-57.21%) |

3.31% (-89.67%) |

| Ardea insignis | 25.73% | 20.62% (-19.88%) |

13.86% (-46.15%) |

6.10% (-76.28%) |

| Trachypithecus shortridgei | 23.28% | 4.88% (-79.05%) |

0.75% (-96.76%) |

0.88% (-96.23%) |

| Aceros nipalensis | 21.31% | 15.19% (-28.72%) |

13.54% (-36.46%) |

18.15% (-14.80%) |

| Tragopan blythii | 21.31% | 19.67% (-7.66%) |

19.54% (-8.30%) |

27.40% (+28.60%) |

| Magnolia nitida | 20.30% | 8.91% (-56.12%) |

7.58% (-62.67%) |

6.39% (-68.53%) |

| Trachypithecus pileatus | 20.20% | 16.84% (-16.64%) |

15.26% (-24.43%) |

15.85% (-21.51%) |

| Macaca arctoides | 19.68% | 18.80% (-4.46%) |

10.09% (-48.72%) |

8.45% (-57.09%) |

| Hoolock leuconedys | 17.93% | 15.64% (-12.77%) |

11.83% (-34.02%) |

10.93% (-39.05%) |

| Hoolock hoolock | 16.61% | 14.42% (-13.15%) |

12.66% (-23.77%) |

14.41% (-13.23%) |

| Sitta formosa | 15.23% | 11.14% (-26.85%) |

10.13% (-33.49%) |

12.14% (-20.27%) |

| Aquila heliaca | 10.82% | 8.92% (-17.61%) |

11.34% (+4.80%) |

16.85% (+55.71%) |

| Asarcornis scutulata | 10.78% | 9.49% (-12.01%) |

8.53% (-20.92%) |

7.74% (-28.25%) |

| Neofelis nebulosa | 10.70% | 12.16% (+13.58%) |

11.74% (+9.72%) |

17.54% (+63.83%) |

| Helarctos malayanus | 9.86% | 7.95% (-19.31%) |

8.98% (-8.95%) |

12.60% (+27.85%) |

| Turdus feae | 9.62% | 8.48% (-11.87%) |

7.41% (-23.00%) |

13.36% (+38.82%) |

| Elephas maximus | 9.55% | 11.09% (+16.08%) |

11.24% (+17.64%) |

16.52% (+72.96%) |

| Gyps bengalensis | 9.54% | 8.92% (-6.49%) |

7.92% (-16.94%) |

16.00% (+67.76%) |

| Manis pentadactyla | 9.44% | 9.89% (+4.77%) |

9.28% (-1.65%) |

16.69% (+76.87%) |

| Cuon alpinus | 9.41% | 9.19% (-2.39%) |

9.05% (-3.84%) |

10.98% (+16.59%) |

| Bos gaurus | 8.82% | 8.69% (-1.50%) |

7.63% (-13.54%) |

13.12% (+48.78%) |

| Arctictis binturong | 8.65% | 7.54% (-12.85%) |

7.14% (-17.43%) |

8.85% (+2.32%) |

| Aonyx cinereus | 8.51% | 7.43% (-12.69%) |

6.81% (-19.91%) |

8.13% (-4.47%) |

| Ursus thibetanus | 8.35% | 8.13% (-2.72%) |

7.79% (-6.79%) |

11.78% (+40.96%) |

| Macaca leonina | 7.50% | 7.86% (+4.71%) |

6.74% (-10.14%) |

10.24% (+36.39%) |

| Nycticebus bengalensis | 7.16% | 8.20% (+14.58%) |

9.56% (+33.48%) |

12.92% (+80.53%) |

| Viverra megaspila | 7.04% | 10.94% (+55.34%) |

12.83% (+82.17%) |

18.47% (+162.14%) |

| Haliaeetus leucoryphus | 6.79% | 6.66% (-2.04%) |

6.10% (-10.24%) |

6.34% (-6.68%) |

| Tapirus indicus | 6.55% | 9.36% (+42.89%) |

5.16% (-21.16%) |

0.00% (-100.00%) |

| Rusa unicolor | 6.45% | 7.59% (+17.57%) |

7.79% (+20.70%) |

10.94% (+69.45%) |

| Magnolia gustavii | 6.23% | 3.13% (-49.73%) |

2.43% (-61.06%) |

0.00% (-100.00%) |

| Clanga clanga | 6.10% | 7.45% (+22.12%) |

8.75% (+43.31%) |

12.81% (+109.89%) |

| Mulleripicus pulverulentus | 5.61% | 6.77% (+20.74%) |

7.08% (+26.29%) |

10.34% (+84.40%) |

| Sterna acuticauda | 5.13% | 5.66% (+10.33%) |

5.39% (+4.99%) |

3.44% (-32.95%) |

| Bos javanicus | 4.95% | 8.59% (+73.54%) |

7.59% (+53.37%) |

4.89% (-1.15%) |

| Leptoptilos dubius | 4.74% | 2.78% (-41.25%) |

2.07% (-56.26%) |

1.84% (-61.17%) |

| Rhyticeros subruficollis | 4.60% | 3.37% (-26.74%) |

2.10% (-54.40%) |

1.46% (-68.24%) |

| Columba punicea | 4.51% | 0.00% (-100.00%) |

extinction (NA) |

extinction (NA) |

| Otus sagittatus | 4.48% | 7.08% (+58.02%) |

3.67% (-18.02%) |

0.97% (-78.36%) |

| Emberiza aureola | 4.36% | 6.68% (+53.35%) |

7.62% (+74.83%) |

6.88% (+57.94%) |

| Gyps tenuirostris | 4.23% | 1.37% (-67.51%) |

3.09% (-26.89%) |

5.58% (+31.89%) |

| Leptoptilos javanicus | 4.15% | 3.83% (-7.62%) |

3.76% (-9.40%) |

4.23% (+1.92%) |

| Trachypithecus germaini | 4.12% | 1.93% (-53.22%) |

0.00% (-100.00%) |

0.00% (-100.00%) |

| Calidris pygmaea | 3.98% | 5.98% (+50.04%) |

11.98% (+200.70%) |

25.39% (+537.29%) |

| Ciconia episcopus | 3.71% | 4.39% (+18.48%) |

3.62% (-2.28%) |

3.62% (-2.36%) |

| Neophocaena phocaenoides | 3.32% | 2.77% (-16.61%) |

2.43% (-26.70%) |

2.00% (-39.87%) |

| Manis javanica | 3.31% | 2.66% (-19.52%) |

2.66% (-19.74%) |

0.64% (-80.62%) |

| Heritiera fomes | 3.23% | 2.28% (-29.55%) |

2.66% (-17.64%) |

6.87% (+112.23%) |

| Sonneratia griffithii | 3.16% | 2.36% (-25.48%) |

2.50% (-21.05%) |

2.68% (-15.36%) |

| Clanga hastata | 3.12% | 2.87% (-7.82%) |

13.60% (+336.53%) |

0.00% (-100.00%) |

| Balaenoptera musculus | 3.11% | 2.27% (-27.11%) |

2.63% (-15.33%) |

2.69% (-13.64%) |

| Halophila beccarii | 3.09% | 2.32% (-24.84%) |

2.65% (-14.13%) |

2.64% (-14.37%) |

| Rucervus eldii | 2.78% | 2.77% (-0.44%) |

2.44% (-12.06%) |

2.25% (-18.87%) |

| Aythya baeri | 2.73% | 1.91% (-29.96%) |

1.48% (-45.84%) |

1.13% (-58.48%) |

| Orcaella brevirostris | 2.39% | 4.22% (+76.72%) |

5.64% (+136.02%) |

8.16% (+241.78%) |

| Lutrogale perspicillata | 2.26% | 2.67% (+18.37%) |

2.84% (+25.97%) |

2.50% (+10.75%) |

| Hylobates lar | 2.25% | 1.96% (-13.01%) |

1.29% (-42.88%) |

0.62% (-72.64%) |

| Heliopais personatus | 2.09% | 2.30% (+10.04%) |

2.25% (+7.97%) |

2.46% (+18.10%) |

| Prionailurus viverrinus | 2.05% | 3.88% (+89.20%) |

6.36% (+210.07%) |

4.15% (+102.12%) |

| Pavo muticus | 2.00% | 1.68% (-16.12%) |

1.41% (-29.71%) |

0.95% (-52.61%) |

| Sarcogyps calvus | 1.87% | 0.60% (-67.69%) |

0.14% (-92.31%) |

1.20% (-35.82%) |

| Grus antigone | 1.79% | 0.88% (-50.89%) |

0.00% (-100.00%) |

extinction (NA) |

| Rynchops albicollis | 1.74% | 1.78% (+2.12%) |

1.78% (+1.99%) |

1.46% (-15.91%) |

| Trachypithecus phayrei | 1.63% | 1.71% (+4.71%) |

1.72% (+5.40%) |

1.88% (+15.31%) |

| Sitta magna | 1.01% | 1.21% (+20.01%) |

1.45% (+44.01%) |

0.16% (-84.09%) |

| Chrysomma altirostre | 0.05% | 0.03% (-39.53%) |

0.03% (-43.92%) |

0.33% (+547.42%) |

| Hydrornis gurneyi | 0.00% | 0.00% (NA) |

0.00% (NA) |

extinction (NA) |

| Calidris tenuirostris | 0.00% | 0.00% (NA) |

0.00% (NA) |

0.00% (NA) |

| Petinomys vordermanni | 0.00% | 0.00% (NA) |

0.00% (NA) |

0.00% (NA) |

| Treron capellei | 0.00% | 0.00% (NA) |

0.00% (NA) |

0.00% (NA) |

| Tringa guttifer | 0.00% | 0.00% (NA) |

extinction (NA) |

extinction (NA) |

| Mergus squamatus | 0.00% | 0.00% (NA) |

0.00% (NA) |

extinction (NA) |

| Arborophila charltonii | 0.00% | 0.00% (NA) |

0.00% (NA) |

extinction (NA) |

| Nisaetus nanus | 0.00% | 0.00% (NA) |

extinction (NA) |

extinction (NA) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).