1. Introduction

The importance of healthcare quality is beyond doubt! The vigorous development of the healthcare industry and the rapid development of medical technology have resulted in the increasing demands of the public on healthcare quality. Under the goal of pursuing efficiency and improving healthcare quality, it has become an important competitive factor for the healthcare industry to face competition and meet consumer needs [

3,

15,

16]. Therefore, how to improve and enhance the quality of healthcare has been increasingly valued by hospital administrators, and will be an important trend in the management of healthcare institutions in the future.

On the other hand, today’s healthcare practices are generally commercialized. The public’s requirements for healthcare quality are gradually increasing, and the trust in medical staff is decreasing year by year. Furthermore, there have been endless health insurance and medical disputes recently. To improve the healthcare quality to meet the needs of patients is a critical and important management issue for hospital managers [

19]. Hospitals are entrusted with the responsibility of caring for the general public, as non-profit organizations. It should not have been for profit. However, the overall healthcare environment is changing rapidly. Under the pressure of peer competition, hospitals must improve operating efficiency and healthcare quality in order to achieve sustainable operation goals.

Accordingly, healthcare service quality assessment is a very important part of the modern healthcare system. It indeed can help patients and the public understand the performance of healthcare institutions and doctors in terms of professionalism, service quality, safety, etc., so as to further improve the healthcare quality and protect the rights and interests of patients [

2]. However, there are also some problems in the assessment of healthcare quality. First of all, the evaluation standards and indicators are not perfect and comprehensive, and some important aspects may be overlooked, affecting the accuracy and reliability of the evaluation results. Secondly, there are also problems with the impartiality and objectivity of the evaluation results, which may be affected by the subjective factors and conflicts of interests of the evaluators, thus affecting the evaluation results. In addition, the frequency and scope of healthcare quality assessment are limited, making it impossible to detect and solve health care quality problems in a timely manner.

The evaluation of healthcare quality therefore needs to be continuously improved and perfected, and more comprehensive, objective and fair evaluation indicators and standards should be established. It should also strengthen the training and management of assessors to improve the accuracy and reliability of assessments [

13,

23]. At the same time, the assessment process also needs to strengthen the self-assessment and management of medical institutions and doctors, establish a more complete healthcare quality management system, and improve healthcare quality and service levels.

Healthcare quality evaluation indicators include both objective indicators and subjective indicators, and these multiple dimensional indicators have their own unique advantages and limitations [

5]. Objective indicators mainly evaluate the quality of healthcare from the aspects of the patient’s health status, the implementation of medical procedures, and the efficiency of the use of medical resources [

16]. The results are usually more objective and accurate. However, objective indicators often only reflect superficial phenomena, lacking in-depth evaluation and analysis.

On the contrary, subjective indicators usually evaluate healthcare quality from different perspectives and experiences of patients and family members, doctors and nurses, and medical management personnel, which can more comprehensively reflect the real situation of healthcare quality and the good degree of doctor-patient relationship. However, subjective indicators are easily affected by human factors, and the evaluation results may be affected by subjective consciousness and cultural background, so there is a certain degree of subjectivity and uncertainty. Consequently, in the selection and application of healthcare quality evaluation indicators, it is necessary to rationally use objective and subjective indicators according to the specific situation and purpose, give full play to their advantages, and avoid their limitations and shortcomings, so as to improve the accuracy and effectiveness of healthcare quality evaluation [

1].

However, assessing the quality of healthcare services is a complex task, essentially a group multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) problem, since various criteria must be considered during the evaluation process [

1,

3,

14,

16,

17,

18]. In fact, in the process of evaluating self-advantages and technical capabilities of the performance of medical institutions, the judgments of evaluators are mostly determined by qualitative representations such as past experience, vague and imprecise knowledge, or subjective cognition. The content is mainly numerical, interval, and linguistic, and the evaluation levels are uneven. Integrating this information becomes an important management topic. Therefore, this paper attempts to propose an objective and systematic mechanism and platform for evaluating the service quality of healthcare.

Furthermore, in the decision-making process of measuring the healthcare service quality, evaluators are committed to making judgments through empirical cognition and subjective perception. However, there is a considerable degree of uncertainty, ambiguity, and heterogeneity [

12]. This situation is not uncommon. In addition, information loss is prone to occur in the process of evaluating data integration, resulting in the evaluation results of service level may not be consistent with the evaluator’s expectations. Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop a simple method to calculate performance ratings while integrating the evaluation process and properly manipulating the operation of qualitative factors and expert judgment in the healthcare quality evaluation process. In this paper, we propose a suitable model based on 2-tuple fuzzy linguistic information to evaluate healthcare service quality. The proposed method not only inherits the existing features of fuzzy language assessment, but also overcomes the information loss problem of other fuzzy language assessment methods.

This article is organized as follows.

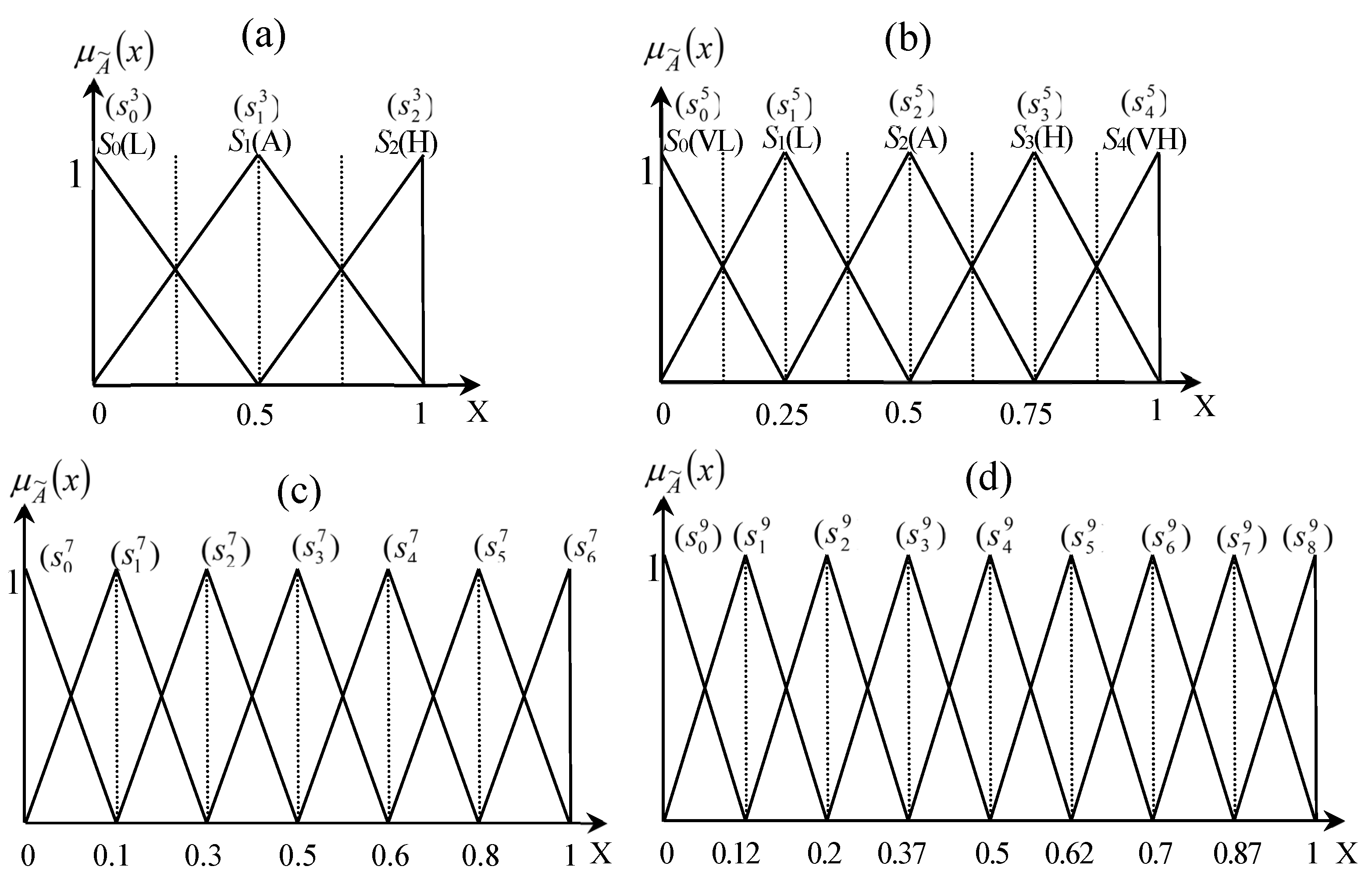

Section 2 describes the measurement dimensions of healthcare quality assessment. In Section III, we introduce the basic definitions and notations of fuzzy language representations and operations of fuzzy numbers, linguistic variables, and 2-tuple fuzzy linguistic representation and operation, respectively.

Section 4 proposes a healthcare quality evaluation approach based on 2-tuple fuzzy linguistic information. The proposed model is then illustrated by taking a diverse hospital in Taiwan as an example.

Section 5 concludes the paper.

2. Determinants of Healthcare Service Quality

The Materials and Methods should be described with sufficient details to allow others to replicate and build on the published results. Please note that the publication of your manuscript implicates that you must make all materials, data, computer code, and protocols associated with the publication available to readers. Please disclose at the submission stage any restrictions on the availability of materials or information. New methods and protocols should be described in detail while well-established methods can be briefly described and appropriately cited.

Healthcare is a fundamental and considerable social welfare issue whose importance deeply affects all levels of society. Its quality has been defined as “the ability to use legitimate means to achieve a desired objective,” with the implicit ideal being “an attainable state of health. Namely, healthcare quality can be viewed as a means of achieving improved health outcomes for consumers. Nonetheless, essential prerequisites for quality healthcare include medical quality, appropriate technology, timely treatment, adequate services according to needs, and assurance of acceptable standards of medical practice. More importantly, from a business perspective, healthcare quality is a surefire way to expand the customer base and thereby gaining a competitive advantage, and ensuring economic viability and long-term profitability. Consequently, it is an indispensable topic for the healthcare industry to establish an objective, systematic, and profitable mechanism and platform for evaluating the healthcare service quality [

1,

2,

16].

In general, with the rapid development of information and communication technology (ICT), the cloud, Internet of Things, AI and other technologies, the global healthcare industry has begun to integrate with technology, and is developing towards intelligence under the leadership of government policies in various countries. There is also a wave of intelligence in medical services, and smart hospitals are an inevitable trend. The business opportunities brought about by it include drug automation system, logistics tracking system, health management system, information security system, patient process management system, intelligent ward system, etc. Therefore, smart hospital management, intelligent medical material system, and precision medical services are bound to lead the way [

15].

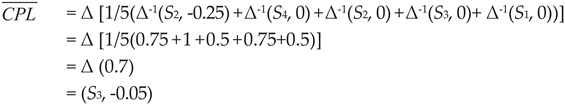

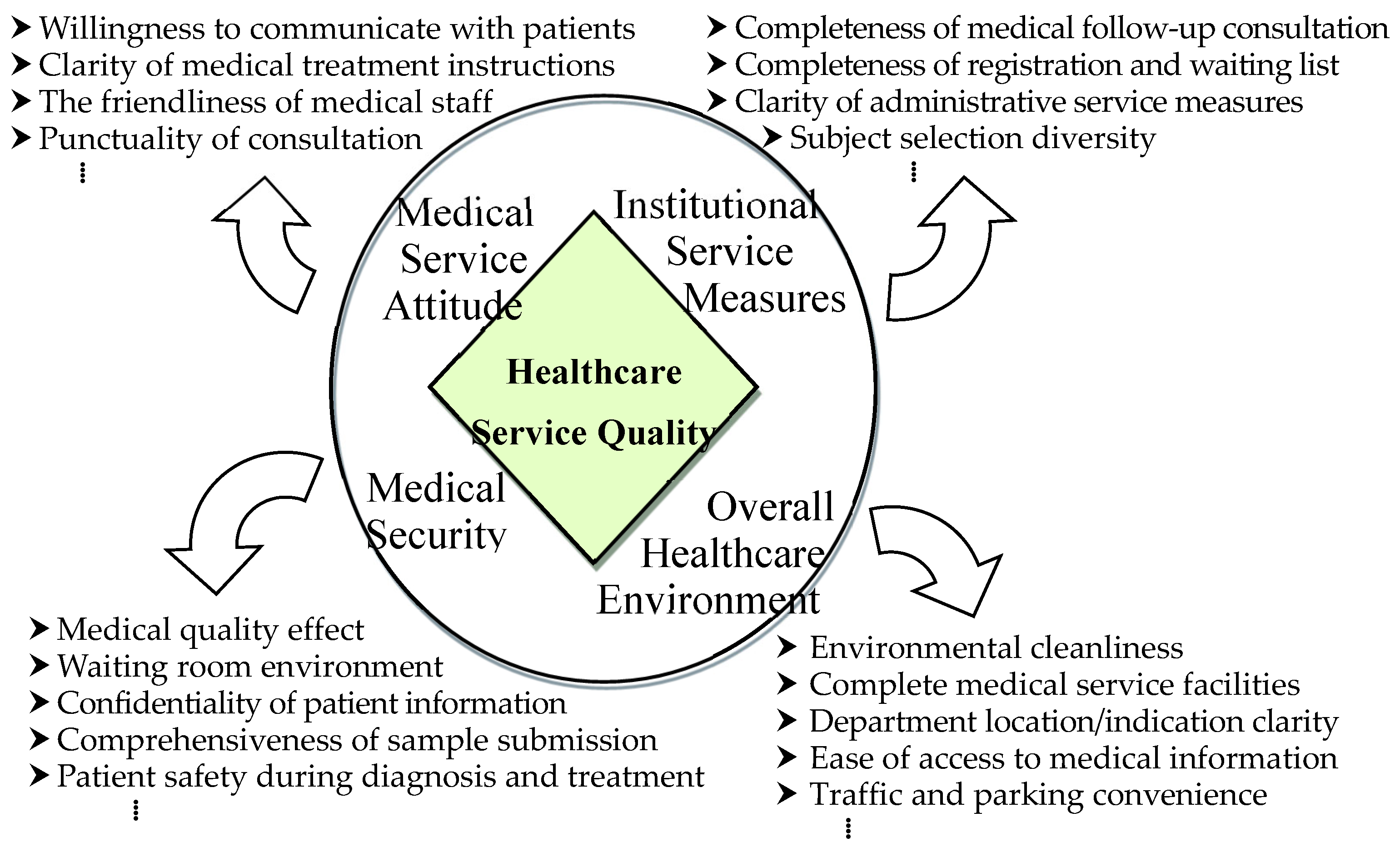

For all intents and purposes in the conduct of practice or research, overall service quality of healthcare can be regarded as a multidimensional entity, influenced by various interacting aspects and participants: the agencies that organize and finance healthcare, healthcare providers, and front-line professionals meet the needs of patients in diagnosis, treatment and, over recent years, rehabilitation. Lupo [

16] proposed the three main dimensions of healthcare quality, which are management quality, professional quality, and stakeholder perceived quality, respectively. This study integrates it into three perspectives for exploration; that is, from the perspective of managers; from the perspective of professional medical personnel; and from the perspective of patients and users (

Figure 1).

- ➤

The managerial perspective involves efficient and effective resource utilization and management to deliver services that meet stakeholder needs.

- ➤

The Professional/Technical Perspective includes the views of healthcare experts and professionals on the medical aspects of healthcare.

- ➤

Stakeholder perspectives include public/patient perceptions of aspects of healthcare involving accessibility, responsiveness, interpersonal relationships, hospitality, and other service characteristics.

The definition of medical quality by the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organization (JCAHO): Given the current state of medical knowledge, healthcare services are provided to patients that increase the likelihood of benefit to the patient while reducing the degree of possible disadvantage to the patient.

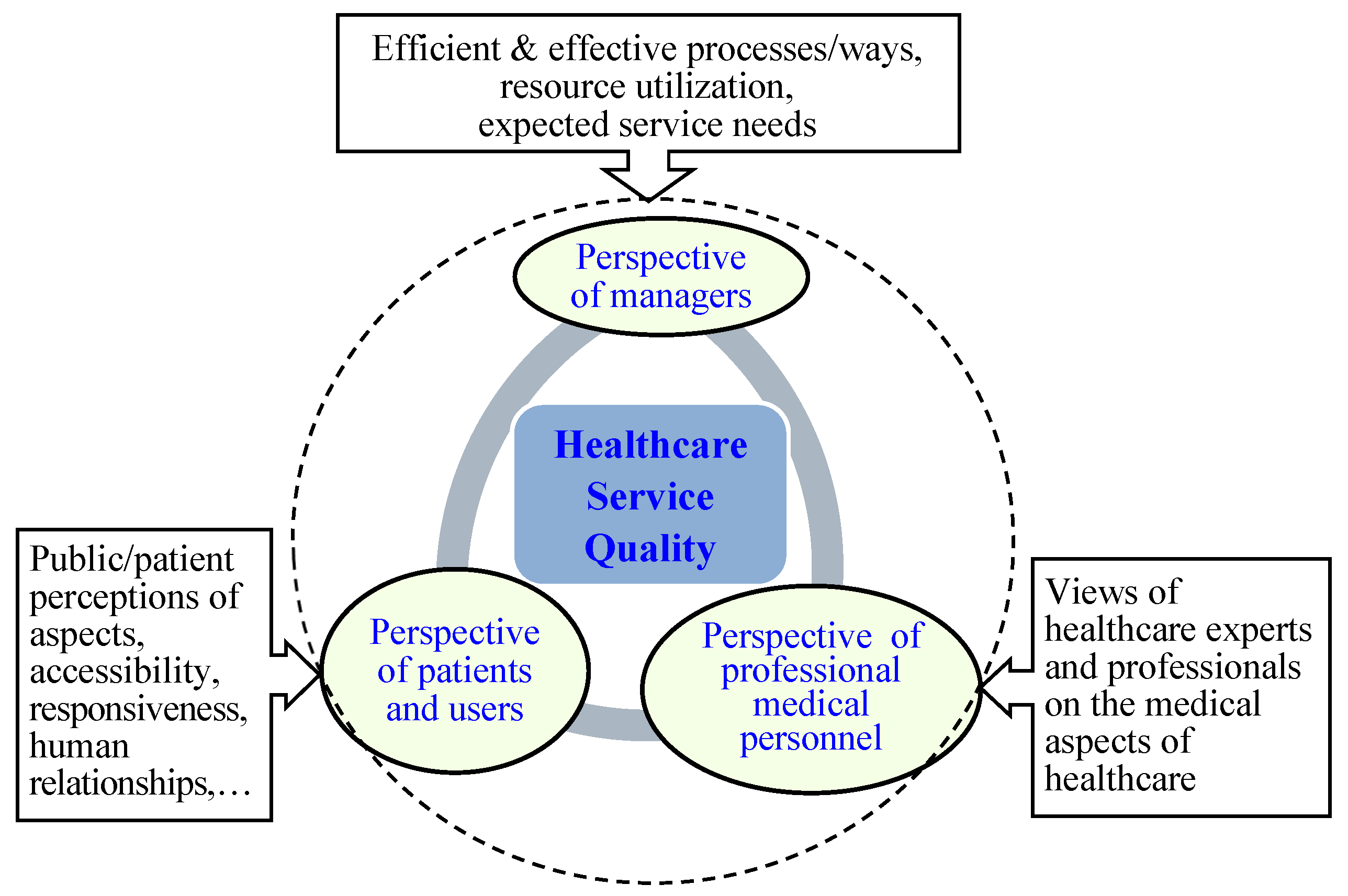

The healthcare service quality indicators are an important basis for evaluating the performance of medical institutions and doctors in terms of professional level, service quality, and safety. It is also an important means to improve the healthcare quality [

2,

6]. A collection of many studies [

1,

6,

13,

14,

17,

18,

19,

20] pointed out that an effective healthcare quality evaluation index (EHQEI) must have five characteristics, namely Reliability, Validity, Sensitivity, Operability and Comparability, respectively. (as shown in

Figure 2).

Based on above-mentioned characteristics, effective healthcare quality evaluation indicators should be comprehensive, objective, reliable, effective, operable and comparable, and can provide useful feedback and improvement directions for healthcare institutions and doctors, thereby improving healthcare quality and service levels.

Healthcare quality can be an issue in any kind of healthcare delivery [

2,

19]. The broad sense of “quality” includes not only the healthcare quality defined above, but also the quality of medical services, medical expenses, qualifications of medical service personnel, safety and suitability of equipment provided by medical services, and the satisfaction level of the hardware or software facilities prepared by medical services. Establishing an effective method for evaluating the healthcare quality is the primary task of improving medical quality. However, healthcare quality is not easy to quantify and standardize, but it tends to use more objective evidence to monitor the healthcare quality. The definition and measurement of healthcare quality indicators vary according to the times and needs. Focusing on the overall quality of medical services, analyzing service providers in terms of structure, process and results, or investigating the relationship between users of medical resources Satisfaction is a method for evaluating healthcare quality indicators.

Regarding the establishment of evaluation indicators for overall healthcare service quality, the previous literature mostly started from three aspects [

1,

2,

15,

17]. The first is structural indicators: it is to evaluate whether the organization has sufficient resources to provide good medical and healthcare, including hardware equipment, service scope, organizational attributes, number of personnel and professional qualifications, equipment and other factors. However, the disadvantage of structural indicators is that they cannot fully evaluate the connotation of healthcare quality, especially the level of interaction at the level of interpersonal relationships. The second is the process level index: it is the standard for detecting diagnosis and treatment behavior activities or providing care, including accessibility, continuity, coordination, etc. The third is the outcome index: it measures the frequency of expected or unexpected events after receiving medical care.

Usually, the outcome indicators [

6,

19] can be evaluated using the following five items: (1) Biological effectiveness, such as incidence rate, survival rate, and disease-free survival rate; (2) Functional effectiveness: such as the quality of life of the patient; (3) Patient satisfaction (4) medical expenses; and (5) cost-effectiveness (cost-effectiveness)]. Among them, medical expenses are the easiest to measure. However, in empirical experience, medical expenses are not necessarily a guarantee of healthcare quality. Therefore, how to establish a multi-level healthcare quality evaluation standard and avoid an evaluation method that emphasizes economic interests and healthcare structure is worthy of further discussion and development.

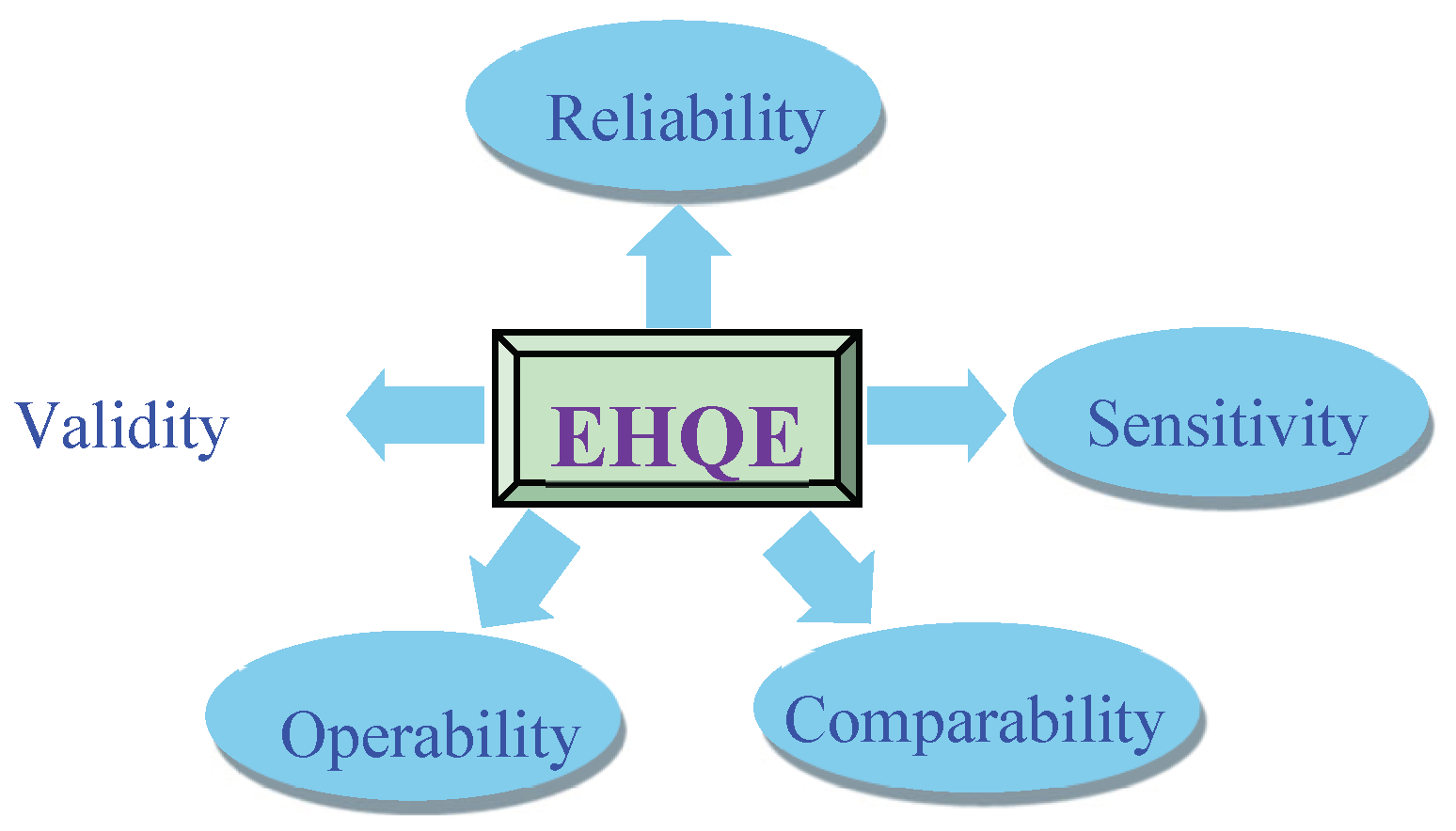

Furthermore, the healthcare service quality evaluation process has many intangible or qualitative standards and sub-standards. It is difficult and laborious to directly use traditional crisp values to measure the healthcare service quality. That is to say, the service itself has intangible characteristics and is not easy to measure; it is often ambiguous in cognition, such as “satisfied”, “normal”, and “dissatisfied” and other words, there are degrees of difference in everyone’s cognition different [

21]. Therefore, this study takes fuzzy theory into consideration and evaluates the quality of healthcare services.

Consequently, the linguistic variables represent ratings that are beneficial for evaluators to express and evaluate the service quality provided by healthcare institutions in suchlike situation. The fundamentals of 2-tuple fuzzy linguistic approach are to use linguistic variables to express the difference of degree and to implement processes of computing with words easier and without information loss during the integration procedure [

7,

20,

21]. Namely, decision-making participants or evaluators can apply linguistic variables to estimate measure items and get final evaluation results with appropriate linguistic variables. It is an effective method to reduce decision-making time and errors in information translation and avoid information loss through text calculation. Therefore, this paper researches the required healthcare service quality assessment facet, factors and service quality assessment items. Accordingly, this paper establishes the required healthcare service quality evaluation model.

4. The Proposed Approach in Healthcare Service Quality Evaluation

In the near future, a medical institution hopes to self-assess the quality of its healthcare services through a systematic, organized, and logical scientific method, so as to achieve the following objectives, and enhance its overall competitive advantage.

- ➤

Provide better patient care: medical institutions are committed to providing the best patient care, improving the quality of medical services can ensure that patients receive appropriate attention, care and treatment during treatment, and improve patient satisfaction and curative effect.

- ➤

Ensuring safety and quality: Improving the quality of medical services helps ensure that medical facilities operate in accordance with safety standards and best practices. By establishing standard operating procedures and implementing monitoring and evaluation, medical institutions can improve the accuracy and efficiency of medical operations and reduce errors and complications.

- ➤

Enhancing the image of medical professionals: providing high-quality medical services helps to establish a good image of medical professionals. This is critical to the reputation and brand image of a medical institution, attracting more patients and medical professionals, and gaining the trust and support of the community and partners.

- ➤

Meet regulations and regulatory requirements: Medical institutions need to comply with various regulations and regulatory requirements to ensure that the medical services provided meet the corresponding standards and requirements. Improving the quality of medical services can help meet these requirements and reduce possible legal risks and penalties.

- ➤

Improve comprehensive medical experience: Improving the quality of medical services can improve the comprehensive medical experience of patients and their families. This includes providing a more convenient appointment system, shortening waiting time, improving communication and information sharing, and providing humanized environment and facilities, so that patients can feel more comfortable and caring during the medical treatment process.

Generally speaking, it is to be able to improve the quality of its healthcare services, have definite goals and directions, and ultimately ensure that the public receives the best healthcare. According to the concepts of fuzzy linguistic computing method, this study proposes a 2-tuple-based evaluation approach to measure the healthcare service quality level of an actual hospital in Taiwan. Suppose there are n criteria Ci(i = 1, 2, …, n) and each criterion contains several sub-criteria in the healthcare service quality performance evaluation framework. The proposed method can help the medical institution to effectively improve the quality of healthcare service related problems, and proficiently apply the limited medical resources. All in all, the following questions can be responded:

How to establish the facet factors and evaluation items of healthcare service quality evaluation?

Determination of the weights of the hospital service quality evaluation facet factors and service quality evaluation items.

Introduce the fuzzy multi-criteria evaluation method to obtain the performance of hospital service quality.

Explore the impact of the hospital’s inclusion of medical quality indicators on its operating efficiency.

Explore the impact of hospitals’ inclusion of medical quality indicators on medical investment resources.

What aspects should be included in the establishment of healthcare service quality indicators in the past? How to create meaningful and effective indicators? There is no consistent consensus. In order to construct a healthcare service quality measurement index with a high degree of theoretical basis, high applicability and verifiability, the research method and structure data source designed in this study firstly compiles the aspects and indicators that may be considered in the measurement of healthcare service quality based on relevant literature, and the preliminary healthcare service quality indicators are established. In order to take into account the professionalism and representativeness of the indicators, five senior executives of the designated healthcare institute in this paper formed a self-evaluation committee and interviewed each other to integrate their views and opinions. And carry out various indicator corrections to establish dimensions and indicators suitable for evaluating the quality of healthcare services. Through fieldwork and in-depth discussions with the general public, experts, operators, and front-line medical staff, it can be concluded that the main concerns of measuring the quality and performance of healthcare services are as follows (as shown in

Figure 5.):

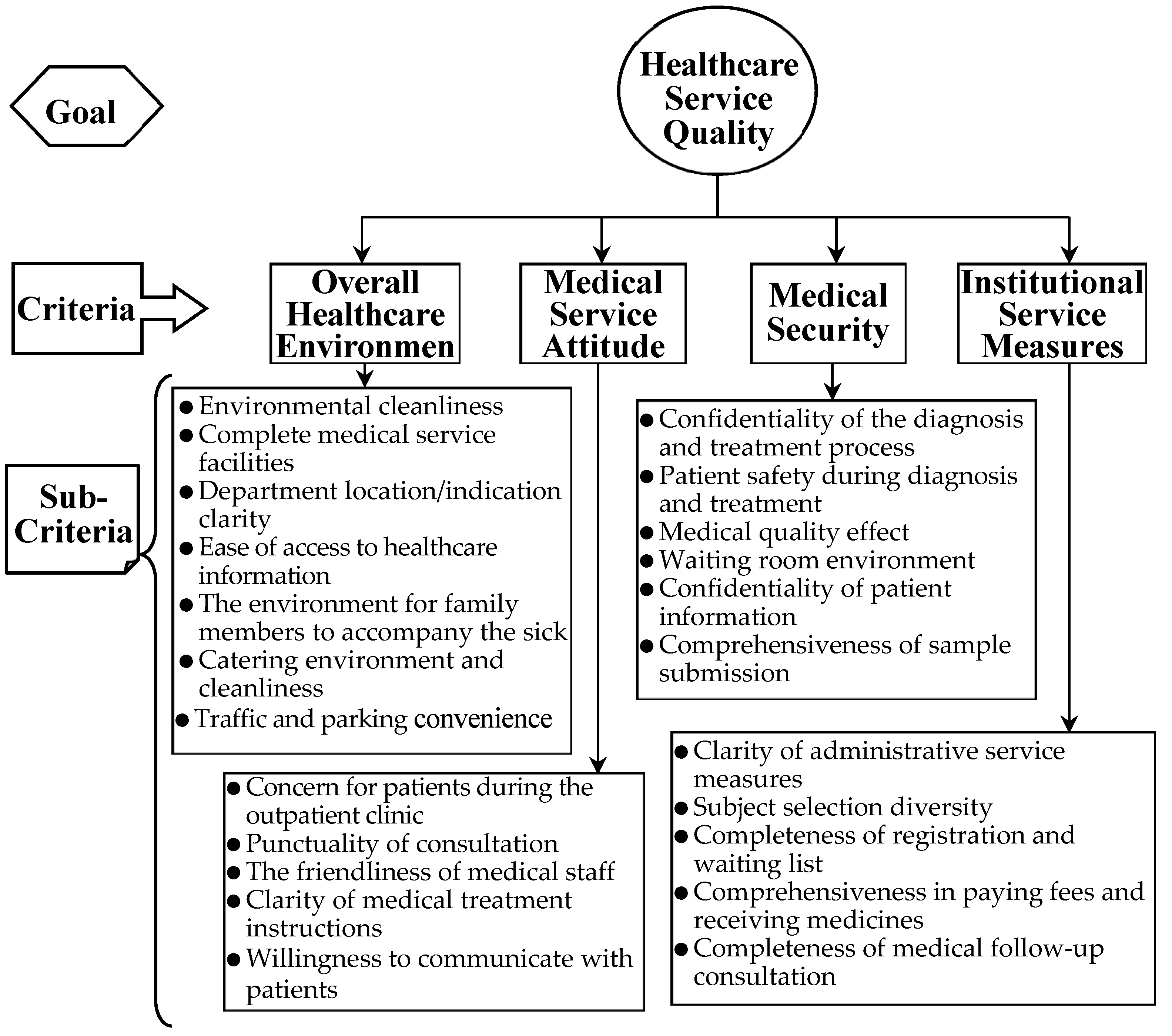

The core viewpoints of each criterion and sub-criteria are briefly described below, and their hierarchical structure is shown in

Figure 6.

Overall Healthcare Environment: It refers to various factors and elements inside and outside the medical institution, including the physical environment, personnel composition, management system, facilities and equipment, and service quality, which have an impact on the medical experience and results of patients and medical staff. The sub-criteria are as follows:

Environmental cleanliness

Complete medical service facilities

Department location/indication clarity

Ease of access to medical information

The environment for family members to accompany the sick

Catering environment and cleanliness

Traffic and parking convenience

Medical service attitude: It refers to the attitude and behavior of medical personnel when treating patients and providing medical services. It is an important part of the quality of medical services and has a significant impact on patient satisfaction, treatment outcomes and medical experience. The sub-criteria are as follows:

Concern for patients during the outpatient clinic

Punctuality of consultation

The friendliness of medical staff

Clarity of medical treatment instructions

Willingness to communicate with patients

Medical security: It refers to ensuring that patients are not subject to unnecessary harm caused by medical activities or possible medical errors and accidents during the medical process. It is an important aspect of the quality of medical care, aimed at minimizing medical risks and providing a safe medical environment. The sub-criteria are as follows:

Confidentiality of the diagnosis and treatment process

Patient safety during diagnosis and treatment

Medical quality effect

Waiting room environment

Confidentiality of patient information

Comprehensiveness of sample submission

Administrative service measures of institutions: It refers to various measures and methods adopted by institutions to provide efficient and high-quality administrative services. It involves all aspects of the internal administration of the organization, aimed at improving administrative efficiency and meeting the needs and requirements of the organization and beyond. The sub-criteria are as follows:

Clarity of administrative service measures

Subject selection diversity

Completeness of registration and waiting list

Comprehensiveness in paying fees and receiving medicines

Completeness of medical follow-up consultation

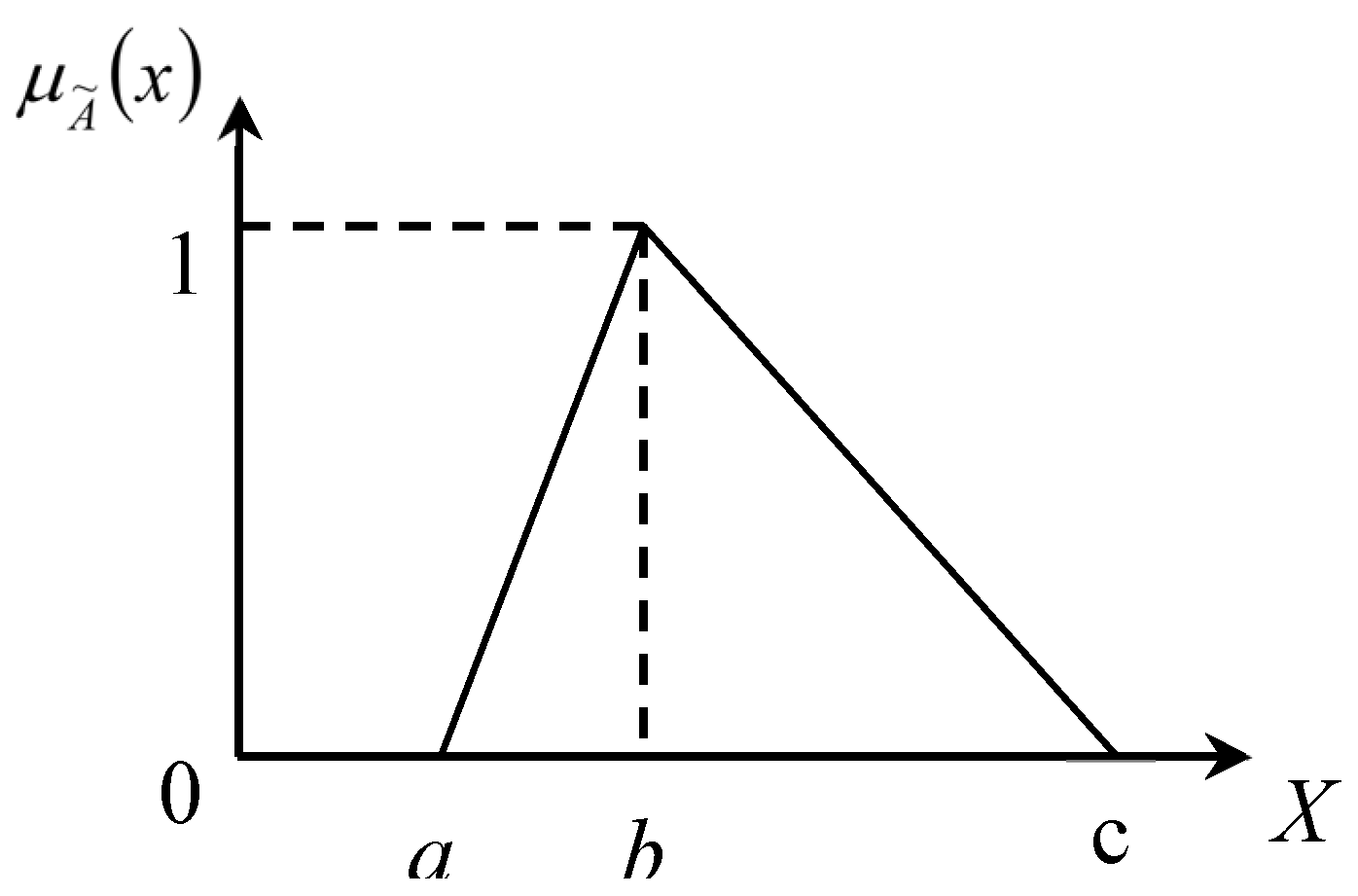

After preliminary and careful screening of relevant materials and the above-mentioned healthcare service quality evaluation literature, a commissioning evaluation committee is composed of 5 senior medical service quality practitioners to conduct self-evaluation for the healthcare service quality currently provided by the designated medical institution. First, all evaluators were asked to judge the overall performance of the designated medical institution’s healthcare service quality according to five levels (imperfect, unsatisfactory, passable, hopefully better, and perfect). That is, each evaluator expresses his personal opinion based on his own knowledge, expertise and experience, and infers the overall performance level of medical service quality for the case hospital. By using linguistic variables, the inferences are “hopefully better”, “Perfect”, “passable”, “hopefully better”, “passable”, respectively, namely (

S3, 0), (

S4, 0), (

S2, 0), (

S3, 0) and (

S2, 0). In addition, four related evaluation criteria and their corresponding sub-criteria lead to further assessments, as shown in

Figure 5. According to the algorithm of the proposed approach as shown in

Figure 4, the health care service quality level evaluation procedure is summarized as follows.

| Step 1. |

Form a healthcare multi-expert evaluation committee, set up relevant healthcare quality evaluation frameworks and criteria, and transform them into their corresponding positive and negative criteria. Five senior employees or supervisors (or more) from different sectors or departments can be appropriately selected to form the service quality review committee. They professionally and objectively evaluate the performance of each criterion and sub-criteria and their corresponding weights. According to Table 1, except for the first and fifth evaluators who use a three-term linguistic variable, the rest of the evaluators use a five-term linguistic variable. |

| Step 2. |

The experts determine the required linguistic term set, individual weight, and performance ratings for each criterion (or subcriteria). Every decision-maker chooses one kind of linguistic variables from the selective categories (Table 1), say, a five-term linguistic variable, to determine the importance of each criterion and the performance of each sub-criterion with respect to each criterion. Afterward the rating outcome is shown in Table 2 and Table 3. |

| Step 3. |

For each criterion, aggregate the fuzzy linguistic assessments of the N experts, and calculate their fuzzy aggregated ratings, respectively.The 2-tuple fuzzy linguistic aggregation method is employed to compute fuzzy evaluation and weighting value of each sub-criterion. For example, fuzzy rating and weighting value of sub-criteria “Traffic and parking convenience” with respect to criterion “Overall Health care Environment” are computed as

five evaluators, the average evaluation value was calculated as

five evaluators, the average evaluation value was calculated as

And then the computational results are shown in Table 4. |

| Step 4. |

Summarize and calculate the overall performance level of healthcare service quality. The aggregated weighting value of each criterion can be calculated as follows; for example, the calculation of the weight of “Medical Service Attitude (MSA)” is as follows.

For example, the weighted rating of “Medical Security” can be calculated as

The right-hand side of Table 4 displays the foregoing outcomes. |

Table 2.

Linguistic assessments of each evaluator for each sub-criteria.

Table 2.

Linguistic assessments of each evaluator for each sub-criteria.

| Criteria |

Members of Evaluation Committee |

| E1

|

E2

|

E3

|

E4

|

E5

|

|

| C1: Overall Healthcare Environment (OHE) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| C11: Environmental cleanliness |

NG |

VG |

A |

VG |

A |

|

| C12: Complete medical service facilities |

G |

G |

G |

G |

NG |

|

| C13:Department location/indication clarity |

G |

G |

A |

G |

G |

|

| C14:Ease of access to medical information |

NG |

A |

VG |

A |

NG |

|

| C15:Environment for family members to accompany the sick |

G |

VG |

G |

VG |

G |

|

| C16:Catering environment and cleanliness |

G |

G |

A |

G |

A |

|

| C17:Traffic and parking convenience |

A |

A |

G |

A |

G |

|

| C2: Medical Service Attitude (MSA) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| C21: Concern for patients during the outpatient clinic |

NG |

A |

VG |

VG |

A |

|

| C22: Punctuality of consultation |

A |

A |

A |

B |

NG |

|

| C23: The friendliness of medical staff |

G |

VG |

A |

G |

A |

|

| C24: Clarity of medical treatment instructions |

NB |

A |

A |

A |

A |

|

| C25: Ability to fill emergency orders |

A |

G |

VG |

VG |

G |

|

| C26: Willingness to communicate with patients |

G |

VG |

VG |

G |

A |

|

| C3: Medical Security (MS) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| C31: Confidentiality of diagnosis and treatment process |

G |

A |

A |

VG |

A |

|

| C32: Patient safety during diagnosis and treatment |

NG |

VG |

A |

VG |

G |

|

| C33: Medical quality effect |

A |

A |

VG |

VG |

A |

|

| C34: Waiting room environment |

A |

G |

G |

VG |

NG |

|

| C35: Confidentiality of patient information |

NG |

G |

VG |

A |

G |

|

| C36: Comprehensiveness of sample submission |

G |

A |

VG |

G |

A |

|

| C4: Institutional Service Measures (ISM) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| C41: Clarity of administrative service measures |

G |

A |

A |

VG |

A |

|

| C42: Subject selection diversity |

G |

VG |

VG |

VG |

NG |

|

| C43: Completeness of registration and waiting list |

A |

A |

G |

VG |

A |

|

| C44: Comprehensiveness in paying fees and receiving medicines |

A |

A |

A |

G |

A |

|

| C45: Completeness of medical follow-up consultation |

NG |

G |

VG |

A |

G |

|

| Step 5. |

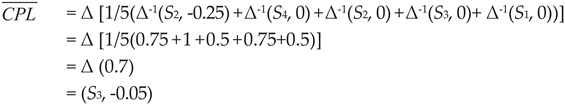

Summarize the current improvement focus of healthcare quality from the results, as well as the strategic goals for future development and management. On the basis of weighted rating values and the aggregated weighting of each criterion, the “comprehensive performance level” (CPL) for the case hospital can be computed as:

|

In contrast with the linguistic term set S, the obtained comprehensive performance level (CPL) of the medical service quality of the designated medical institution, the converted value (S3, -0.011), indicates that it is not as good as “hopefully better”. Such a result is intuitively reasonable. In other words, the final evaluation results of the proposed method are consistent with the initial judgments made by the five evaluators on the overall performance assessment. Furthermore, based on the preliminary inferences made by the five evaluators, the average evaluation value was calculated as

Table 3.

Linguistic assessments of each criterion and corresponding sub-criteria.

Table 3.

Linguistic assessments of each criterion and corresponding sub-criteria.

| Criteria |

Members of Evaluation Committee |

| E1

|

E2

|

E3

|

E4

|

E5

|

|

| C1: Overall Healthcare Environment (OHE) |

VI |

VI |

VI |

I |

I |

|

| C11: Environmental cleanliness |

A |

VI |

A |

A |

A |

|

| C12: Complete medical service facilities |

I |

A |

I |

I |

I |

|

| C13:Department location/indication clarity |

NI |

I |

VI |

VI |

NI |

|

| C14:Ease of access to medical information |

I |

I |

A |

I |

A |

|

| C15:Environment for family members to accompany the sick |

I |

I |

VI |

I |

I |

|

| C16:Catering environment and cleanliness |

NI |

VI |

VI |

VI |

NI |

|

| C17:Traffic and parking convenience |

I |

VI |

I |

VI |

I |

|

| C2: Medical Service Attitude (MSA) |

I |

I |

VI |

I |

VI |

|

| C21: Concern for patients during the outpatient clinic |

I |

A |

VI |

A |

NI |

|

| C22: Punctuality of consultation |

I |

I |

VI |

I |

NI |

|

| C23: The friendliness of medical staff |

NI |

I |

A |

VI |

A |

|

| C24: Clarity of medical treatment instructions |

A |

I |

A |

A |

I |

|

| C25: Ability to fill emergency orders |

NI |

VI |

VI |

VI |

I |

|

| C26: Willingness to communicate with patients |

I |

VI |

I |

VI |

A |

|

| C3: Medical Security (MS) |

VI |

VI |

I |

VI |

VI |

|

| C31: Confidentiality of diagnosis and treatment process |

NI |

I |

A |

VI |

I |

|

| C32: Patient safety during diagnosis and treatment |

NI |

I |

I |

VI |

I |

|

| C33: Medical quality effect |

A |

VI |

VI |

A |

NI |

|

| C34: Waiting room environment |

I |

VI |

I |

A |

A |

|

| C35: Confidentiality of patient information |

I |

A |

VI |

VI |

NI |

|

| C36: Comprehensiveness of sample submission |

A |

I |

I |

I |

I |

|

| C4: Institutional Service Measures (ISM) |

I |

I |

VI |

I |

I |

|

| C41: Clarity of administrative service measures |

NI |

VI |

A |

I |

NI |

|

| C42: Subject selection diversity |

I |

A |

I |

VI |

I |

|

| C43: Completeness of registration and waiting list |

I |

I |

I |

I |

I |

|

| C44: Comprehensiveness in paying fees and receiving medicines |

A |

VI |

A |

VI |

I |

|

| C45: Completeness of medical follow-up consultation |

I |

A |

VI |

I |

A |

|

From the overall results in

Table 4, the current service level of specific medical institutions is the best in both C

15(Environment for family members to accompany the sick) and C

42(Subject selection diversity), with a high score of 0.95. In other words, the evaluated medical institution is superior in both C

15 and C

42 criteria. Administrators can therefore make good use of these two advantages to create and improve the quality of medical services. In addition, C

25(Ability to fill emergency orders), C

26 (Willingness to communicate with patients) and C

32(Patient safety during diagnosis and treatment) also have an outstanding performance of 0.85 points. On the other hand, it has unsatisfactory evaluations in C

22(Punctuality of consultation) and C

24(Clarity of medical treatment instructions), and even C

24 only has a score of 0.45, which is a part that needs to be strengthened urgently. That is, the main disadvantages of the designated medical institution are C

22 and C

24. Therefore, the management must seek to improve these criteria of performance practices. Observing the four evaluation criteria, C

1(Overall Healthcare Environment, OHE) currently has the best overall performance, followed by C

3 (Medical Security, MS), C

4 (Institutional Service Measures, ISM) and C

2 (Medical Service Attitude, MSA). Therefore, according to the current overall health care service quality of the designated hospital, it is urgent to improve C

2.

Table 4.

Aggregation results.

Table 4.

Aggregation results.

| Criteria |

Mean rating |

Mean weighting |

Weighted rating |

Aggregated weighting |

| C1: Overall Healthcare Environment (OHE) |

| C11: Environmental cleanliness |

(S3, 0) |

(S2, 0.1) |

(S3, 0.0143) |

(S3, 0.01535) |

| C12: Complete medical service facilities |

(S3, 0.05) |

(S3, 0.05) |

| C13:Department location/indication clarity |

(S3, 0.05) |

(S3, 0.1) |

| C14:Ease of access to medical information |

(S3, -0.05) |

(S3, -0.05) |

| C15:Environment for family members to accompany the sick |

(S4, -0.05) |

(S4, -0.1) |

| C16:Catering environment & cleanliness |

(S3, -0.05) |

(S4, -0.1) |

| C17:Traffic and parking convenience |

(S2, 0.15) |

(S4, -0.05) |

| C2: Medical Service Attitude (MSA) |

| C21: Concern for patients during the outpatient clinic |

(S3, 0) |

(S3, 0) |

(S3, -0.0583) |

(S3, -0.0479) |

| C22: Punctuality of consultation |

(S2, 0) |

(S3, 0.1) |

| C23: The friendliness of medical staff |

(S3, 0) |

(S3, -0.05) |

| C24: Clarity of medical treatment instructions |

(S2, -0.05) |

(S2, 0.15) |

| C25: Ability to fill emergency orders |

(S3, 0.1) |

(S4, -0.05) |

| C26: Willingness to communicate with patients |

(S3, 0.1) |

(S3, 0.1) |

| C3: Medical Security (MS) |

| C31: Confidentiality of diagnosis &treatment process |

(S3, -0.05) |

(S3, 0.05) |

(S3, 0.0833) |

(S3, 0.01053) |

| C32: Patient safety during diagnosis & treatment |

(S3, 0.1) |

(S3, 0.1) |

| C33: Medical quality effect |

(S3, -0.05) |

(S3, 0) |

| C34: Waiting room environment |

(S3, 0) |

(S3, 0) |

| C35: Confidentiality of patient information |

(S3, 0.05) |

(S3, 0.1) |

| C36: Comprehensiveness of sample submission |

(S3, 0) |

(S3, 0) |

| C4: Institutional Service Measures (ISM) |

| C41: Clarity of administrative service measures |

(S3, -0.05) |

(S3, 0) |

(S4, -0.0281) |

(S3, -0.03) |

| C42: Subject selection diversity |

(S4, -0.05) |

(S3, 0.1) |

| C43: Completeness of registration &waiting list |

(S2, 0.15) |

(S3, 0.1) |

| C44: Comprehensiveness in paying fees & receiving medicines |

(S2, 0.05) |

(S3, 0.05) |

| C45: Completeness of medical follow-up consultation |

(S3, 0) |

(S3, 0) |

| Comprehensive performance level (CPL) |

(S3, -0.011) |

In addition, from the perspective of the four evaluation criteria, the members of the evaluation committee tend to pay more attention to the quality of health care services from the perspective of C1(Overall Healthcare Environment, OHE, (S3, 0.01535), quite important). Although C2(Medical Service Attitude, MSA, (S3, -0.0479), not so important) is the major of most judges, they don’t pay much attention to it. In terms of the reason, they are confident in their profession, but as for the professional peripheral supporting services, it is not the quality of health care service that they care about. For example, C22, (S3, -0.0479), Punctuality of consultation, is limited by surgery or other administrative affairs, delays in meetings, and …, making it impossible to conduct outpatient consultations on time, which is not what outpatient physicians would like to see.

Because the case hospital is close to the seaside, the wind is usually strong, not to mention the northeast monsoon has a great impact; so it is different from the traditional space design arrangement, and the main administrative services such as registration, price approval, drug collection, inspection, and most outpatient services are combined. The locations are all arranged on the first floor of the basement. This is a relatively unique design method, and it is also affirmed by the public. This can be seen from the high evaluation of the hospital in item C4 (Institutional Service Measures, ISM, (S4, -0.0281)).

It is worth mentioning that the medical institution of the case is located in a rural area, but its performance in C17 ((S2, 0.15) means unsatisfactory performance) is mediocre, reflecting that although the location is not ideal, if the traffic flow, tour pick-up, parking arrangements and surrounding services can be done well support and preparation can still prevent patients or family members from having to take this unfavorable factor into consideration. From another point of view, in terms of criteria C17 and C25 that most evaluators consider very important (considers their average weight to be very high, say (S4, -0.05)), the performance of the case hospital is not satisfactory. That is, none stand out. That is to say, on these key factors that everyone thinks are very important, some more breakthrough methods must be made in order to demonstrate a more ideal quality of health care services and win the trust of the public.