Preprint

Article

Unveiling the Secret Sauce: Unravelling How Teachers Decode School Culture for Optimal Learner Retention in Schools That Are in Adverse Conditions

Altmetrics

Downloads

104

Views

36

Comments

0

This version is not peer-reviewed

Embedding Sustainability in Organizations through Climate, Culture and Leadership

Submitted:

07 April 2024

Posted:

10 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Alerts

Abstract

This paper explores teachers’ professional practices to gain a thorough grasp and a deep understanding of what it takes to retain learners in an environment where most schools fail to do so. I approach the study using a qualitative multiple case study design and position it within the interpretive paradigm. I purposively selected 50 post-level one teachers from five schools. Cavanagh and Dellar’s theory on culture of school improvement, which emphasizes the transformation of schools into learning communities through social interaction, interpersonal relationships, and support among various stakeholders, including parents, teachers, and learners, was used as theoretical lens for this research. To generate data, I used focus group discussions. I present and discuss data through four themes namely, fundamental values, ethics and behaviour in the classroom, their influence in building learners’ moral vocabulary in the classroom, Classroom rituals in running the classroom smoothly and learner productivity, the effects of the celebrations on the classroom-learning communities, role served by heroes and heroines in learners learning together. In conclusion, one dynamic that stood out is that not all values that teachers had were mutually consistent or harmoniously realisable. Despite that, teachers focused on the central task of teaching, learning and management with a sense of responsibility, purpose and commitment. Teachers seemed to have mind-sets that supported a good work ethic, achievement, commitment, passion and love to attend their teaching duties diligently. Teachers uphold the values through rituals that symbolised order, that prepared students for learning and helped in binding learners of the school and teachers to each other and emphasised the unique values of the school culture. They also uphold them by celebrating academic achievement and had learners and other people who were taken as heroes and heroines of the school and were looked up to by other learners and members of the staff and generally set the tone for the way things were done.

Keywords:

Subject: Social Sciences - Education

1. Introduction

Nearly 25 years since this country’s first democratic elections, the school system unfortunately still confronts many difficulties, partly because of South Africa’s historic legacy of apartheid.

A number of writers referenced in the National Planning Commission report (Berg et al., 2011) on raising the standard of education in South Africa describe the country’s educational system as being divided into two distinct parts: the historically disadvantaged system, which serves the majority of students, and the system that serves black and coloured children.

Research indicates that the organizational life and educational quality of schools located in these disadvantaged socioeconomic contexts—whose cultures were severely disturbed prior to 1994—remain poor (Berg et al., 2011; Westhuizen et al., 2005 Fleisch & Shindler, 2007; Sayed & Ahmed, 2011). Research on learner retention rates reveals that most classes have between 60 and 80 students, that schools lack enough resources and facilities, and that a small percentage of students have access to learning support services and resources to assist them explore and discover career alternatives. (Grossen, 2017; Kriek & Grayson, 2009; Magopeni & Chiwula, 2010; Ndimande, 2012).

The second national school sub-system produces educational achievement which is closer to the norms of developed countries and those schools historically serve white and Indian children, although black and coloured middle-class children are increasingly migrating to these schools (Department of Education, 2013b). Students in Grade 5 at historically white schools are performing twice as well as students in historically black schools, according to literacy and numeracy tests conducted as part of the National School Effectiveness Study (NSES). In traditionally white schools, students are taught in their mother tongue in order to increase their chances of passing year-end examinations (Levine & Lezotte, 1990).

The government of democratic, post-apartheid South Africa faces many important issues, one of which is rebuilding an education system that will reestablish and instill a culture of teaching and learning. According to research, our nation’s schools—particularly the historically black schools—remain marked by high dropout rates, erratic attendance from both students and instructors, and unsatisfactory Grade 12 scores. A culture of learning and teaching (COLT) is largely impossible (Nxumalo, 1995; Lethoko et al., 2001). The large percentages of repeaters and high dropout rates, among other indicators, point to the absence of a suitable or appropriate environment or climate.

2. Background of School Culture as a Determinant of Learner Retention

The foundation of organizational learning is school culture. Like glue, culture unites individuals and gives those impacted by it hope and faith. Acquiring this knowledge can help pinpoint the positive components of school culture that need to be strengthened. In a 2007 article for The Times, Jansen detailed a South African educational setting. He explained using the body language of a teacher as a metaphor, pointing out that whereas teachers in certain schools walk from point A to point B, in others they almost run, indicating that they wish to get somewhere quickly, possibly so they can instruct their students. Jansen (2007) asserts that walking conveys a carefree, informal attitude. This makes it possible to refer to schools as having distinct cultures, which are made up of a variety of attitudes, values, and behaviors that set good schools apart from unproductive ones.

Jansen establishes a clear connection, explaining why the academic performance of schools with teachers who run—referred to as “white, Afrikaans schools”—is (on average) higher than that of schools whose teachers walk—previously disadvantaged “black” schools in rural areas and the townships. According to him, this isn’t just because the former enjoy a relatively privileged position with respect to resources; rather, it’s because their culture hasn’t been disrupted by changes in the political environment. Grant et al.s’ (2018) study on teacher leadership in deprived contexts revealed that while some schools in these contexts are dysfunctional, others are able to rise above their circumstances and offer their students high-quality educations. Deprived school contexts can be challenging educational environments or impoverished communities located in townships or rural areas (Hanley, Winter, & Burrel, 2020; Myende & Chikoko, 2018; Chikoko, 2018; Muller & Goldberg, 2020).

Learner dropout percentage from 2007 to 2021 is displayed in Table 1.2. With the dropout rate in schools reaching 49%, as Table 1.2 illustrates, it is clear that the Department of Education has not addressed this issue in the last 10 years. Learners leave the schooling system without acquiring the skills to support the nation’s economy (Shepard & Mohohlwane, 2021). According to figures from Statistics South Africa, the country’s youth unemployment rate was 67% in 2021, and 34% of young people between the ages of 15 and 24 were not enrolled in school, received no training, or not worked.

According to the Department of Basic Education’s 2018 School Monitoring Survey, teachers do not always show up for class. On any given day, up to 10% of teachers are absentwork without permission. According to the data, the percentage of absent teachers rose from less than 8% in 2011 to more than 10% in 2017–18. The kind of school culture that teachers hope to foster in order to support students’ learning is determined by the way they collaborate as well as the shared values, beliefs, and presumptions that they hold.

Even while free and compulsory education as well as the school nutrition program in South Africa have contributed to an increase in enrollment, particularly in primary school, the internal efficiency of schools—which is determined by secondary school learner retention—remains concerning (UNESCO, 2012). Numerous research have been conducted on how to reorganize and enhance schools, with an emphasis on enforcing new policies and procedures. (Darling-Hammond, Cobb, and Bullmaster, 2021; Department of Education, 2013b; Woods, Jeffrey, Troman, & Boyle, (2019; Zolghadr & Asgari, 2016); Liddicoat et al., 2018; Rumberger, 2001; Tinto, 2003). Little is known about the cultures of schools that, in spite of difficult circumstances, offer their students excellent educational possibilities. Seeking to contribute to this body of work, the study explored the nature of school cultures as explained by the teachers that in fact enable and sustain learners.

The main question that arises from the aforementioned scenario is the following:

- How do teachers describe and explain the culture of their school in relation to high learner retention rates?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Elements of School Culture

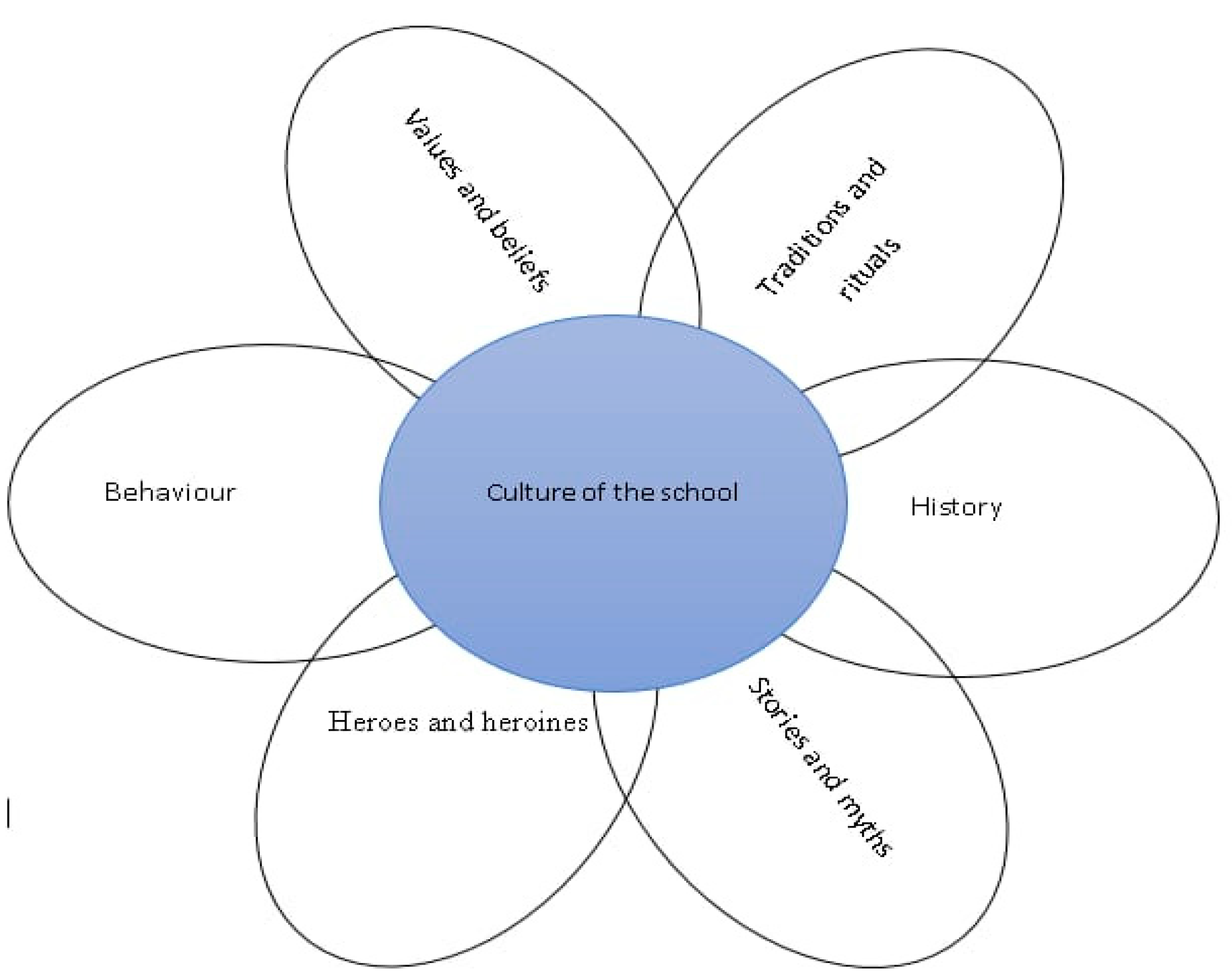

An overview of the values and beliefs, behavior, traditions, history, heroes and heroines, and stories that shape the school’s culture comprise the symbolic elements of school culture. When someone walks into a school, everything they see, hear, and feel about the environment—including the words and actions of the teachers and students—relates to the underlying stream of rituals and values that spread throughout schools. This underlying stream is the school’s culture. People’s attitudes, values, and beliefs define an organization’s culture, which is mirrored in how we conduct business here (Schein, 2003). According to Stoll (2000), school culture include specific concerns such as learners’ emotional and physical safety, classroom order, and the extent to which the school values and promotes racial, ethnic, and cultural diversity. School culture is formed and molded through conversations with others and introspection about life and the wider world. As seen in Figure 1.1, culture is shaped and characterized by the intersection and overlapping of symbolic elements across time.

2.1.1. Values and Beliefs

Values are described by Deal and Peterson (2016) as a system of guidelines for what constitutes excellence, goodness, and quality. The foundation of what the school values is its values. What is appreciated are values. They explain the character traits that direct our behavior, how we treat ourselves and other people, and how we engage with the outside environment. A school’s core values define the qualities that are foundationally desired to be modelled by the educational practices within a school and to be internally established in the practices of its students (Hinde, 2004).

Deal and Peterson (2016) define beliefs as consciously held mental opinions about what is true and real. These are comprehensions of the environment we live in. Teachers share their beliefs regarding the importance of education in the classroom. A teacher might think that experience learning is important. Her behavior then reflects this belief, which is an indication of culture. The school management has certain views regarding innovation, social class and ethnicity, and the role that instructors have in fostering students’ learning. A school’s belief about learning forms the basis for teaching and learning practices and decisions.

Research about school culture indicates that a positive environment is created when the basic values of the school community are established and embraced by the school community. Understanding and upholding the school’s standards fosters a sense of community and belonging, making learners feel good about the school and increasing their motivation to learn (Fincher & Mullis, 1996; Cowen & Lawton, 2001). Most learners achieve academic success in schools with strong value cultures (Christie, 2001; Lee, 2001). For instance, teachers modeling positive values in the classroom creates a pleasant learning environment and give learners the mindset they need to excel in school.

The school’s mission statements are firmly grounded in the values and beliefs, which also serve as a basis for the policies, choices, and processes of the institution (Heystek et al., 2008). School mottos serve as a crystallization of values, reflecting the school’s actual actions and views. Other schools use symbols to convey their ideals and beliefs. For instance, some schools use a plant as a symbol to represent their core beliefs. A plant represents the school’s dedication to providing all students with the love and care that makes them feel like princesses and princes.

According to Cowen and Lawton (2001), school communities can embrace countless values. Some schools have determined that the best values are cooperation, honesty, persistence, respect, personal integrity, equity, academic excellence, diligence, intellectual curiosity, and an appreciation of diversity. It is crucial to instill strong moral principles in students because attitudes influence behavior, and learners’ decisions reflect the school’s values and beliefs. Students’ mindsets are shaped by the excellent moral ideals that are taught in them, and this is reflected in their behavior and attitude. Values and beliefs cover the things that are truly significant to an organization, such as creativity, excellence, transparency, quality, teamwork, and the allocation of group members’ energy.

2.1.2. Rituals

Rituals are defined by Deal and Peterson (2016) as regular school activities that honor significant morals and unite individuals through shared experiences. Rituals, when well-crafted, involve the school community in educational experiences that present students to the fundamental principles of the institution (Fincher & Mullis, 1996). Children’s customs such as walking or standing in lines and using bells to guide them from one area to another contribute to the blending of school cultures.

According to Sinden, Hoy, and Sweetland (2004), rituals effectively unite families, staff, and students into a single community. At the start of each day, having a morning assembly when teachers and learners come together and pray is one way to foster a sense of connection between students and staff. An assembly this well-planned could set a great example for both teachers and students. Students learn the importance of group prayer at the calmest assembly of the school. Some schools have rituals that include morning announcements at assembly. These announcements serve as a sign of order and help pupils get ready for class. When these customs are well-planned, they emphasize the distinctive characteristics of the school culture and serve to strengthen the bonds between teachers and students.

Rituals, according to Fincher and Mullis (1996), contribute to the creation of a cohesive culture of excellence that enhances the school’s internal environment. Rituals are essential for establishing, maintaining, and changing the interpersonal aspects of the organizational culture of the institution. A comforting atmosphere, a cooperative attitude, an academic atmosphere that supports student success, and a friendly interpersonal environment are other interpersonal aspects of the school that rituals improve. According to Deal and Peterson (2016), regular rituals that foster and sustain motivation and focus can enhance learning for both teachers and students. There are many distinct kinds of rituals in schools, each with their own significance. While certain rituals help promote student retention, others cannot.

2.1.3. Ceremonies

According to Stoll (2000), rituals are intricate occurrences that ceremonially convey the deeper symbolic bonds that unite a school. They are therefore considered aspects of school culture. Conversely, Deal and Peterson (2016) characterize ceremonies as unique occasions that unite the past, present, and future, strengthen the school’s social responsibility, and reenergize people for upcoming difficulties. Consequently, ceremonies serve to maintain a connection between organizational members and the deeper ideals of the organization by serving as cultural events or as a means of showcasing important aspects of culture on a regular basis. School ceremonies serve as a platform for showcasing cultural values by reciting essential narratives and honoring significant persons’ accomplishments.

Research on school culture reveals that not all school rituals are meaningful and alive; some are dead, others promote negativity, and some are just mandates (Deal & Peterson, 2016; Marcoulides, George, Marcoulides, Heck, Papanastasio, 2005). The school’s values and its future goals should be reflected in and communicated through ceremonies. Successful schools, for instance, use these occasions to acknowledge the unique contributions made by parents, students, and instructors, honor student accomplishment, and spread values. Schools use a variety of rituals to convey and uphold the standards and values that its members hold dear. The establishment of the Quality Learning and Teaching Committee (QLTC), which is made up of teachers, parents, community members, SGB, district officials, and the principal in some South African schools, is another illustration of mirroring strong values. The committee has a year-long schedule of school events focused on high-quality instruction and learning. These include ceremonies that integrate ethnic, social, and religious groups and are typically held during heritage month; ceremonies that foster a sense of history and continuity through the valedictory ceremony for matric students; and ceremonies that foster pride and respect by acknowledging exceptional achievements to particular groups and individuals. Every year, festivals that support native games are conducted in several schools. Schools compete with one another to popularize this through the Department of Sport and Culture.

2.1.4. Heroes and Heroines

Heroes and heroines set the tone for the school and embody its traditions, values, and beliefs, they are the ones that other students look up to (Stoll, 2015). Teachers, students, parents, or anybody else the school community is proud of who qualifies for special status through words or performances can all be considered heroes and heroines. A student who excels academically and is admired by others, or a sports hero who attended the school and is currently competing for the league, are examples of heroes. Schools honor the heroes with wall art, medals, and plaques displayed, as well as with special ceremonies and ceremonies.

2.1.5. Stories

Telling of stories and articulating significant events in the organization’s history can both reinforce the organization’s traditional values and beliefs and transmit positive messages about the organization’s past (Stoll, 2000). The stories are interpreted and transmitted in different ways by those who communicate the organization’s traditions, strengthening the cultural values.

Schein (2004) asserts that stories, as cultural components, convey information about a school and help new employees understand the school’s culture by providing the necessary emotions to go through trying times. Stories can introduce what is valued, humanize abstract concepts into concrete terms, and make emotional connections between academic concepts and real-world experiences (Deal & Peterson, 2016). Stories are a powerful tool for reinforcing values and ideas and shaping school culture. The fundamental principles of a school can be communicated to its students through anecdotes of exceptional achievement that are steeped in history and sentimentality within the school community. By exchanging tales about the challenges and incidents that educators and students deal with daily,

Additionally, it may strongly evoke something special, which inspires support and loyalty. The cultural values that successful schools uphold via storytelling benefit the community, employees, and students and are likely to keep students in the classroom.

2.1.6. History

Deal and Peterson (1999) described history as a chronicled map of the people, events, crises, and values that shaped it into what it is. One of the most crucial components of a school is its history, which covers the significant occasions, topics, and figures that have influenced the school’s culture over time. Moreover, Deal and Peterson (2016) contend that a school lacking solid cultural foundations would veer aimlessly between challenging circumstances, frequently repeating the same mistakes without any opportunity to grow from them. “People without the knowledge of their past history, origin, and culture are like a tree without roots,” as Marcus Garvey once said. According to Deal and Peterson (2016), understanding the present requires.

The following aspects of the school’s history are mentioned by Stoll (2000): the school’s leadership, its guiding principles, its conflicts and crises, the people who helped shape it, the relationships that grew over time, the changes that brought back vivid memories for teachers, students, and the community, and the manner in which the school handled program changes and goal modifications. Old minute books, time books, awards, staff and student photos, student architecture, and spending time with the school elders are additional items that are seen to be treasure troves for comprehending school culture through history. Prosperous educational institutions preserve the heritage that has led them to this point and draw lessons and values from both recent and historical events.

Numerous countries around the world have published empirical research on learner retention, including China (Huang, 2005), the United States (Moore and Fetzner, 2009), Australia (Lamb, Walstab, Teese, Vickers, & Rumberger, 2004; Gray, Hackiling, & Cowan, 2009), and Nigeria (Inuwa and Yusof, 2012; Essack, 2012). The elements that assist students’ persistence in learning include pleasant learning experiences, positive teaching, encouragement and helpful contact, and feedback, according to a study on learner retention and support conducted in China (Huang, 2005). Giving feedback is a way to apply positive learning since it can help students feel like they are making progress and achieving their academic goals, which can encourage them to stick with their studies.

Enhancing the quality of teaching by specializing in a few streams will help attract qualified teachers in the subjects, which is the first step toward retaining students, especially those who are at-risk, according to a study by Moore and Fetzner (2009) that examined American institutions that achieve high course completion rates. The belief that all teachers can teach students to learn and that all students can learn well and master what they are taught (Block & Burns, 1976) is an ancient mastery learning philosophy theory and practice that they adopted. Students and teachers with similar specializations joined online groups, and any assistance needed by the students was promptly provided. In Australia, there was a decade during which she saw a significant increase in senior school enrollment, as its states made notable progress toward creating mass or universal secondary education systems (Lamb, Walstab, Teese, Vickers, & Rumberger, 2004). To accommodate a wider spectrum of students, numerous governments made significant revisions to the senior secondary school curriculum. As a result, in order for students to continue their education, their aspirational, social, and intellectual requirements must be met.

Gray, Hackiling, & Cowan, (2009) identified what students regard as a healthy secondary school culture; that is, a culture conducive to a positive and productive experience in terms of learner retention, participation and achievement. These include, respect (mutual, acceptance, belonging, intellectual challenge, appropriate curriculum), relationship (confidence, support, involvement, young adult environment, pedagogy, guidance), and responsibility (independent learning, balance, flexibility, discipline, opportunities). The level of social and academic engagement of learners influences the quality of their participation and retention. A study by Inuwa & Yusof (2013) in Nigeria discovered that effective methods of keeping students in secondary government-owned schools included creating a positive learning environment with effective tools for instruction and professional development, as well as refocusing government attention to raise the bar for public secondary education and instill confidence in others, which in turn raised teachers’ morale toward work ethics.

2. Research Methodology

I employed purposive sampling, in this qualitative study, deliberately selecting research participants based on their suitability for advancing the research objectives. Five schools situated in the Eastern Cape Province were specifically chosen due to their relevance to the research problem. These schools, located in adverse conditions yet able to retain their students, were ideal for the study’s purposes. Through purposive sampling, I handpicked six post-level one teachers from each school, totaling 30 participants. Selection criteria prioritized experienced teachers with seniority in the school, measured by the number of years they have been teaching there. This choice was based on the assumption that seasoned post-level one teachers possess a deep understanding of the school’s operations compared to newcomers, as they directly engage with students in the classroom, facilitating effective learning environments until students complete their schooling. To collect data, focus group interviews with teachers were conducted as the primary method. The subsequent analysis involved subjecting interview transcriptions to thematic analysis. This approach was chosen because it aligned with pre-existing topics derived from the theoretical framework. By analyzing the data, I constructed detailed participant descriptions, identified pertinent themes, and ultimately provided substantial explanations.

3. Theoretical Framework Used in School Culture

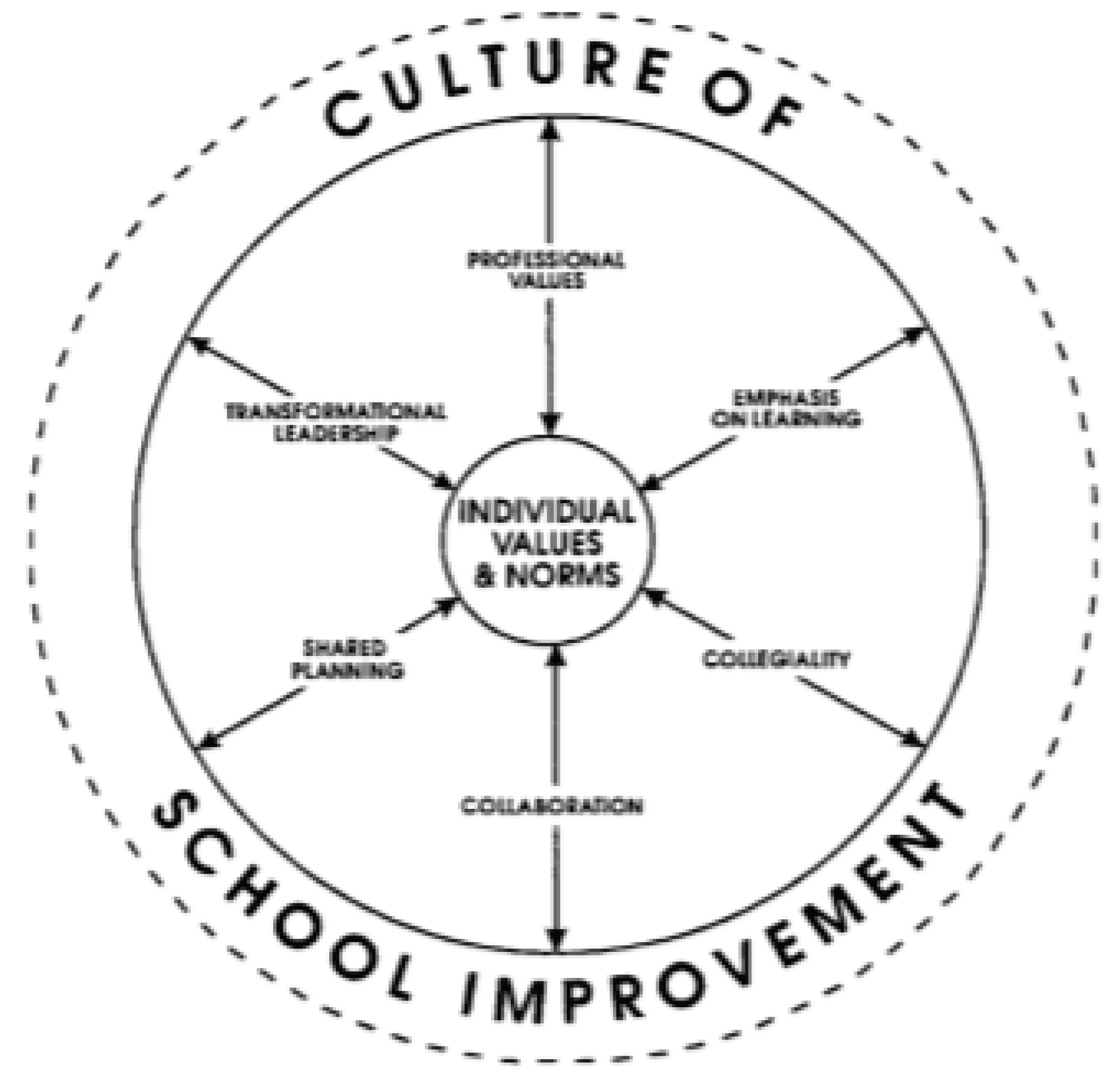

Cavanagh and Dellar’s (1998) theory on the culture of school improvement highlights the significance of fostering a conducive environment within schools that promotes continual self-improvement. This theory emphasizes the transformation of schools into learning communities through social interaction, interpersonal relationships, and support among various stakeholders, including parents, teachers, and learners.

Central to this theory is the notion that a culture of school improvement is characterized by enhanced educational outcomes, a focus on learning, collaboration, collegiality, shared planning, transformative leadership, and professional values. Cavanagh and Dellar identify six forms of culture that contribute to a school’s improvement, including a culture of professional values grounded in pedagogical principles, a culture of emphasis on learning characterized by the development of learning communities and teacher commitment to professional growth, a culture of collegiality that fosters supportive relationships among teachers, and a culture of shared planning that engages teachers in working together toward the school’s vision and development processes. This is created by social processes, interactive and interdependent cultural elements, shown in Figure 2.5. Overall, this theory underscores the importance of nurturing a positive and collaborative school culture to facilitate ongoing improvement.

4. Presentation of Empirical Evidence

In exploring and defining a school’s culture, I found it important to identify several elements that are valuable tools and may assist in defining and developing a clear understanding of the culture of schools. I discussed the fundamental values and beliefs. I looked at the school’s beliefs and key values and how they were upheld through rituals, ceremonies, through story-telling and through history. I interviewed the teachers from five different schools. I wanted their views on what informed their schools to do well, irrespective of their adverse conditions. In practice, values should underpin all that is done at school; what is done and said (behaviour) is determined by thoughts, and what is valued. The school’s fundamental values define the best practices that the school members desire to be modelled in the school and to be reinforced in the practices of the learners.

The selection of Eastern Cape Province for the study was deliberate, chosen for its alignment with the issues under investigation. Both the district and the schools were chosen because they met the criteria of operating in challenging circumstances while still managing to retain their student populations. The enduring challenges stemming from the apartheid era have left some schools in Eastern Cape Province significantly disadvantaged. In response, the Eastern Cape Department of Education (ECDoE) has had to confront the substantial inequalities within the province, resulting from the integration of education departments from Ciskei, Transkei, and the former Republic of South Africa, thereby replacing the inadequately managed homeland system. The homeland system comprises schools with poor infrastructure, including buildings made of cardboard, zinc, prefabs, and mud. All the schools are located in deep rural areas and one in an informal settlement. Despite operating in deprived contexts and facing various socio-economic challenges such as poverty in income, capability, health, and nutrition, these schools demonstrate academic productivity and are successful in retaining learners. I used the following fictitious name to identify the schools; Samantha Fields, Marcus Johnson, Olivia Carter, Elijah Rodriguez, and Maya Pate.

3.1. Teachers’ Description of the Schools’ Values and How They Upheld Them

In discussions with the teachers from Samantha Fields High School, they mentioned that their key values were respect and honouring teaching-learning time. Talking about respect in the classroom, teachers reported that they showed respect in the classroom by listening to their learners when they put forward an opinion, and by doing that, they maintained their dignity and the dignity of the learners. This was their stance:

Learners have a lot of information that we are not aware of. We give them a chance to voice out their opinions. Sometimes, they share what they know of a certain section and tell us how they want to be taught. We respect them by listening to their views so that they can do the same.

To uphold this value, the group of teachers from Samantha Fields reported that one of their classroom rituals involved connecting and interacting positively with the learners. This is the view:

When the teacher enters the classroom, for the first time in any school day, learners stand up and greet the teacher.

Another view from the group was that showing respect helped them to mind themselves, be aware of the tone of their voices when addressing learners, mind their body language, and remove emotions from learners’ destructive behaviours. This is the view they shared:

Some teachers are harsh to learners. To make what we promised in the School’s mission statement relevant, we became aware of our harshness when talking to the learners. We learned that learners’ misbehaviour is not directed at the teachers personally. We treated every learner with the respect h/she deserves. They are confident and participate actively in the classroom. They feel happy about themselves, and a comfortable learning environment develops.

The group acknowledged that respecting one another increased connectedness to the School, learners attended School regularly, and they cared about their learning. This was their overall view:

Our learners are getting attached to the school day by day. Their class attendance has improved. There is a free flow of communication with learners. Classroom disturbances are minimized, and this has resulted in a healthy learning environment

About valuing contact time, the view from the group of teachers was that learning was the most important process of gaining education, and effective and efficient use of contact time optimised learning opportunities for learners. They shared this opinion:

Our learners get education through learning. Therefore, teaching and learning are both important ways of getting an education. Both can be achieved through proper time management by ensuring that those tasked to deliver learning use the time allocated to it, even if it means sacrificing their own time. And those who want to learn to use the time available efficiently. Learning is maximized when we use teaching and learning time in the best and most favourable way.

In further discussing this, another view from the group was that to get learners on board, teachers modelled the expected positive behaviour. This is how they expressed the perspective:

Learners copy what their teachers do. If you come to class late, they will wait for you outside, in the toilets or next to the tap and go to class with you. We arrive early every school day, prepare for our lessons and go to our classes on time. They do the same. Going to class and teaching is second nature to us. The deputy principal encourages us to always be in class and teach. It has become a habit that when we are not in class, it is like committing a crime. Whenever he enters a staffroom and finds teachers, he asks if we are all free. Sometimes he comes with a piece of paper listing the names of people who are supposed to be in class at that time. We feel uncomfortable when we are in the staffroom, and we prefer to be in class to teach.

To uphold this value, one participant from the group shared a good and an encouraging way through healthy competition among the learners that he used to celebrate the culture of learning in his classes. He shared the following:

I bought two beautiful trophies for the two subjects that I teach. The best performing learner in a test gets the trophy. The learner has to protect the trophy, i.e., he/she excels in every formal assessment across the four academic terms. If the learner protects the trophy, I engrave the name on it, and h/she takes it home permanently. This encourages sacrifice, dedication, and value for learning.

The group of teachers from Marcus Johnson High school reported continuous improvement of their practice and respect as their values. Regarding continuously improving their practice, the view from group was that improving their practice was mainly about honing their teaching skills and knowledge to improve the quality of their lessons. This is how they expressed their view:

Improving the way we teach learners involves self-development on the subjects you teach. Some teachers in the school are members of district subject committees and others of cluster subject committees. In these committees, challenging sections are identified and solved, and development opportunities to improve classroom practice are shared. Other teachers make use of suggestion boxes, where learners reflect anonymously about their teaching. Taken positively, the comments help us to improve our teaching.

Another view from the same focus group was that teachers who continuously upgrade themselves either through self-study or being part of professional learning communities were able to adjust their teaching strategies to fit different learners’ needs. Their view was:

Some of us develop our knowledge and skills to stay abreast of developments in our subjects. We have, for example, teachers who further their studies with distance learning institutions, there are skills workshops that are organised by the district offices that are SACE approved, some of us attend workshops that are organised at a provincial level, some at a district level on their specialisation subjects. Teachers who frequently make time for these workshops respond positively to the challenges and are very much equipped with the skills and knowledge that improves their teaching.

Coming to respect, the group reported that they showed respect to their learners by discussing and negotiating the classroom rules with the learners of each class. This is how they put it:

We involve learners when crafting classroom rules as a way of showing respect by allowing them to participate in making decisions as active members of the school. Every classroom has its own ground rules. The class teachers formulate, and discuss the ground rules with the learners concerned. The rules range from taking care of the classroom, taking care of the furniture, treating each other well, respecting teachers, period attendance, submission of tasks etc. They are kept visible in class, reminding everyone what is acceptable and not acceptable.

The group added that to show respect, they preserved a tradition whereby learners stand up to greet the teacher when he/she enters the classroom. This is a recognition of school authority; teachers are expected to be shown respect. They said:

It’s our cultural thing that learners stand up to greet the teacher when walking into the classroom. Some rush quickly to their desks, others woke up from sleeping. Greeting teachers is a sign of respect and it connects us with learners. The classroom would be silent immediately to show readiness to be taught.

The group added that:

A positive relationship with the learners and a positive tone that encourages learning is created.

The focus group acknowledged that respecting one another in the school has built trust between them. This is their view:

The respect we show to our learners, helped in improving our relationship. Classroom rules that are not forced on learners, are agreed upon, are honoured, learners identify with the rules; they own them, to the extent that when the rules are broken, they reprimanded each other. They monitor each other, because they do not want to let down the teachers they trust. There is order in most classrooms. Learners obey rules, there is a healthy climate for teaching and learning.

The focus group from Olivia Carter High School also shared that they valued teamwork, not limited to teachers who taught the same subject, but collaborating with every teacher in the school. They explained that a lot of subjects integrate, as they plan together, they were able to identify areas where integration occurs. They taught these sections at the same time, so that a concept that appeared in one subject was reinforced in another subject.

Because we want our learners to do well, we team up across subjects. We note integration in different subjects, for example, Geography Mapwork integrates with Maths Literacy, History integrates with Economics, Accounting with Business economics and Economics, etc. We have a thorough joint planning. We make sure that sections that integrate are taught in the same week across the subjects, so that concept that appears in one subject is reinforced in another subject

The group added that collaboration across disciplines helped learners to see interconnections between different subjects, and they had a deeper understanding of concepts as they were taught from different perspectives.

Learners do not see subjects as separate; they see interconnection which helps in developing a positive attitude in all subjects. If a learners did not understand the concept in one subject, as it is reinforced in other subjects and by different people, it becomes more clearer and understandable.

Moving on to Elijah Rodrigues High School, the teachers focus group’s key values were positive relationships with learners, commitment and dedication to their work, and subject matter knowledge. With regard to the relationships with learners, the group reported that building meaningful, strong teacher-learner relationships led to improved student engagement and better classroom environment. Their view was:

Learners spend a lot of time with us, in the classroom. We build strong relations with them. Caring about them involves knowing them individually. Getting to know one’s parents, for example, where he/she stays, and his goals in life. Learners are easily motivated to attend classes if they know that you care about them. Knowing our learners and having a close relationship with them improved and strengthened classroom behaviour. Most of the classrooms have an ideal environment, where learners are excited to learn, they engage themselves in lessons and are less likely to need discipline in class.

Coming to the teachers’ subject matter knowledge, the focus group reported that thorough knowledge of the subject matter in the subjects they taught and in-depth understanding of the subject they possessed led to successful learning in the classroom. They said the following:

Teachers specialise in one or two subjects. We learn a lot about them. We are constantly improving our knowledge; we are part of learning communities of teachers in the cluster. Being part of the learning communities help us to read widely on the subjects we teach. Some teachers in the school are members of subject associations, for example Natural science and Social science. They hold sharing sessions where they share their experiences, learn and develop their own thoughts. Some of us upgrade their studies through distance learning.

Teachers revealed that they are dedicated to their job, and they hold themselves accountable for the performance of the learners. To show their commitment and dedication, they shared that they taught learners within and outside school hours, they make pledges of quality results, distinctions, and 100%. This is what they shared:

Instead of spending time with our families, we go to school on weekends and on holidays, we give learners extra classes, free of charge, because we want to help our learners with their studies. We do not want any excuses when it comes to learner performance.

The group added that they value a direct focus on teaching and learning. They reported that they made their lessons relevant and interesting by making them interactive, making learners do most of the work. They said:

We discovered that it is impossible for learners to sleep through the class when they are actively involved in the lesson. We talk less and involve them more. For example, in English literature, we assign them different stories to read, and when they come to class, they relate the stories to other learners. We use hands on learning to engage them on a deeper level.

Moving on to the teachers at Maya Pate High school. They believed in academic excellence, by working closely with other teachers, showing love, care and kindness to the learners and providing support.

Starting with academic excellence, teachers from Maya Pate High School revealed that at the beginning of each year Grade 12 learners made academic pledges of commitment to their studies. In this way, they are encouraging them to take ownership of their own learning. This is their view:

Learners sign pledges of their academic performance in the beginning of the year. They commit on the grades they want to achieve in each of the four school terms. We follow up their commitments on a monthly basis, checking if their performance in tests and classroom tasks tallies with the commitments made.

The group added that they worked jointly (team-teaching), to share the teaching load. They said:

We have a very strong teamwork among those who teach the same subjects. We connected to one another, We teach our classes differently, but we interact a lot.

With regard to loving and caring for learners the group revealed that teaching needs patience and understanding; without love, one could not possess these qualities. They said:

Kindness is contagious and brings joy to both learners and teachers, fostering a more encouraging environment. Teachers demonstrate kindness through gestures like singing “Happy Birthday” and sharing sweets for classmates, while also offering compliments for various actions such as reading in class or maintaining cleanliness. These acts of kindness contribute to learners’ well-being, enhancing their concentration and academic performance..

In order to uphold this value, some of the rituals that the group reported include music in the form of a happy birthday song for each classmate on his/her birthday and greeting a teacher when entering a classroom. They said these appreciation gestures reinforce classroom community. This was the view:

Music serves as a ritual in our classroom, with a joyful rendition of the “Happy Birthday” song for classmates on weekdays, fostering expressions of affection and strengthening bonds among students. Additionally, greeting teachers upon entering sets a positive tone, creating a favorable impression of the class and promoting a conducive learning environment

The group added that the appreciation gesture shown through singing builds stronger relationships among learners, and they get to know each other better. It encourages tolerance and positions students for learning. This is their view:

By celebrating learners’ birthdays collectively, minimizes the likelihood of bullying one another. They get to know each other well, and that makes them accept each other. They feel secure in class, and their grades improve.

Coming to support, the group reported teacher support to the learners in the form of warmth, affection, and understanding the learners builds friendship, trust and interest in the classroom. This was their stance:

We prioritize the well-being of the learners, addressing them personally and monitoring their progress closely. This attentive approach allows us to detect changes in their work habits. In return, learners reciprocate this concern and respect by following classroom rules and showing a genuine interest in their studies.

Drawing from the teachers’ description of school values, the values that the researched schools ascribed to were justifiable, realisable, and practical. In their own understanding values must be realised, there is no point in a school having a set of values well-articulated in the minds of teachers, on paper, values require practical interpretation and application. One dynamic was that not all values were mutually consistent or harmoniously realisable. There was diversity or tension as teachers ascribed to different set of values, it became unclear which ones to prioritise and which ones to put more emphasis on. Despite that, the school participants focused on the central task of teaching, learning and management with a sense of responsibility, purpose and commitment. Teachers seemed to have mind-sets that supported a good work ethic, achievement, commitment, passion and love to attend their teaching duties diligently. The school showed a strong teamwork among teachers, data reveal that teachers worked jointly to share the workload. Therefore, schools possessing the cultural forms focusing on school improvement, as suggested by Cavanagh and Dellar (1998) are likely to retain learners, because students’ learning is at the centre, students take ownership of their own learning and can easily set goals for themselves.

There were rituals that symbolised order, that prepared students for learning. These rituals helped in binding learners of the school and teachers to each other and emphasised the unique values of the school culture. The schools celebrated academic achievement and had learners and other people who were taken as heroes and heroines of the school and were looked up to by other learners and members of the staff and generally set the tone for the way things were done. I can say that schools that retain learners mine past and present experiences for important lessons and principles and nourish the heritage that brought them to the present.

References

- Berg, Taylor, Gustafsson, Spaull, & Armstrong. (2011). National Planning Commission : Improving Education Quality in South Africa.

- Block, J. H., & Burns, R. B. (1976). Mastery learning. Review of research in education, 4, 3-49.

- Cavanagh, R. F., & Dellar, G. B. (1998). Towards a model of school culture. American Educational Research Association (AERA).

- Chikoko. (2018). The Nature of the deprived School Context. In Vitallis Chikoko (Ed.), Leadership that Works in Deprived School Contexts of South Africa. NOVA.

- Christie, P. (2010). Landscapes of Leadership in South African Schools: Mapping the Changes. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 38(6), 694–711. [CrossRef]

- Cowen, R., & Lawton, D. (2001). Values in Education. In J. Cairns, D. Lawton, & R. Gardner (Eds.), Values, Culture and Education (1st ed.). Kogan Page educational management series.

- Darling-Hammond, L., Cobb, V., & Bullmaster, M. (2021). Professional Development Schools as Contexts for Teacher Learning and Leadership 1. In Organizational learning in schools (pp. 149-175). Taylor & Francis.

- Deal, T. E., & Peterson, K. D. (2016). Shaping school culture. (3rd ed.). Jossey-Bass.

- Department of Basic Education. (2018). School Monitoring survey.

- Department of Education. (2013b). the Internal Efficiency of the School System.

- Fincher, F. S., & Mullis, F. (1996). Using rituals to define the school community. Elementary School Guidance and Counselling, 30(4), 243–251.

- Fleisch, B., & Shindler, J. (2007). School participation from birth to twenty; patterns of schooling in an urban child cohort study in South Africa.

- Grant, C., Naicker, I., & Pillay, S. (2018). Expansive teacher leadership in deprived school contexts. In V Chikoko (Ed.), Leadership that Works in Deprived School Contexts of South Africa. NOVA.

- Gray, J., & Hackling, M. (2009). Wellbeing and retention: A senior secondary student perspective. The Australian Educational Researcher, 36, 119-145. [CrossRef]

- Grossen. (2017). Repeated retention or dropout? Disputing Hobson’s choice in South African township schools Silke. 37(2). [CrossRef]

- Hanley, T., Winter, L. A., & Burrell, K. (2020). Supporting emotional well-being in schools in the context of austerity: An ecologically informed humanistic perspective. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 90(1), 1-18. [CrossRef]

- Heystek, & Lumby, J. (2008). Race, identity and leadership in South African and English schools.

- Inuwa, A. M., & Yusof, N. B. M. (2013). Parents and students perspectives of school culture effects on dropouts and non-dropouts in Sokoto Metropolis Nigeria. Research on Humanities and Social Sciences, 3(18), 89-96.

- Jansen, J. D. (2007). Class divisions: The principal is the key to the success of a school. The Times.

- Kriek, & Grayson. (2009). A holistic development model for South African physical science teachers. South African Journal of Education, 29(22), 185–203. [CrossRef]

- Lethoko, M. X., Heystek, J., & Maree, J. G. (2001). The role of the principal, teachers and students in restoring the culture of learning, teaching and service (COLT) in black secondary schools in the Pretoria region. South African Journal of Education, 21(4), 311–317. [CrossRef]

- Levine, D. U., & Lezotte, L. W. (1990). Unusually effective schools: A review and analysis of research and practice. In National Center for Effective Schools Research and Development. WI.

- Liddicoat, A. J., Scarino, A., & Kohler, M. (2018). The impact of school structures and cultures on change in teaching and learning: the case of languages. Curriculum Perspectives, 38(1), 3–13. [CrossRef]

- Magopeni, & Chiwula. (2010). The realities of dealing with South Africa’s past: A diversity in higher education. Paper presented at the Tenth International Conference on Diversity in Organizations, Communities & Nations, Northern Ireland, 19–21 Julyle.

- Marcoulides, G. A., Heck, R. H., & Papanastasiou, C. (2005). Student perceptions of school culture and achievement: Testing the invariance of a model. International Journal of Educational Management, 19(2), 140-152. [CrossRef]

- Moore, J. C., & Fetzner, M. J. (2009). The road to retention: A closer look at institutions that achieve high course completion rate. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 13(3), 3–22. [CrossRef]

- Müller, L. M., & Goldenberg, G. (2020). Education in times of crisis: The potential implications of school closures for teachers and students. Chartered College of Teaching.

- Myende, P., & Chikoko, V. (2018). Leadership for School-Community Partnership: A school Principal’s Experience in a deprived Context. In Vitallis Chikoko (Ed.), Leadership that Works in Deprived School Contexts of South Africa. NOVA.

- Ndimande, B. S. (2012). Race and resources: black parent’s perspectives on post-apartheid South African schools. Race, Ethnicity and Education, 15(4), 525–544. [CrossRef]

- Nxumalo, B. (1995). The culture of learning: a survey of KwaMashu schools. Indicator South Africa, 10, 55–60.

- Rumberger, R. W. (2001). Why Students Drop Out of School and What Can be Done.

- Sayed, Y., & Ahmed, R. (2011). Education quality in post-apartheid South African policy: Balancing equity, diversity, rights and participation. Comparative Education, 47(1), 103–118. [CrossRef]

- Schein, E. H. (2004). Organizational culture and leadership (3rd ed.). Jossey-Bass Publishers.

- Shepard, D. & Mohohlwane, N. 2021. The impact of COVID-19 in education more than a year of disruption. National Income Dynamic Study. Coronavirus Rapid Mobile Survey.

- Stoll, L., & Fink, D. (1996). Changing our schools: Linking school effectiveness and school improvement. Open University Press.

- Stoll, L. (1998). School culture. School Improvement Network’s Bulletin, 9.

- Sinden, E. Hoy, K & Sweetland, R. (2004). An analysis of enabling school structure: Theoretical, empirical, and research consideration. Journal of Educational Administration, 42(4), 462–478.

- Tinto. (2003). Promoting student retention through classroom practice.

- UNESCO. (2012). Report on the UN Decade of Education for Sustainable Development, Shaping the Education of Tomorrow.

- Westhuizen, P. C. Van der, Mosoge, M. J., Swanepoel, L. H., & Coetsee, L. D. (2005). Organisational culture and academic achievement in secondary schools. Education and Urban Society, 38(1), 89–109.

- Woods, P., Jeffrey, B., Troman, G., & Boyle, M. (2019). Restructuring schools, reconstructing teachers: Responding to change in the primary school. Routledge.

- Zolghadr, M., & Asgari, F. (2016). Creating a climate and culture for sustainable organizational change. Management Science Letters, 6(11), 681–690. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

1: Overlapping symbolic elements, which describe the culture of a school. Source: Schein, (2004).

Figure 1.

1: Overlapping symbolic elements, which describe the culture of a school. Source: Schein, (2004).

Figure 2.

5: Theory on the culture of school improvement (Source: adopted from Cavanagh & Dellar, 1998).

Figure 2.

5: Theory on the culture of school improvement (Source: adopted from Cavanagh & Dellar, 1998).

Table 1.

2: Learner dropout percentage in each province from 2007 to 2021.

| Province | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eastern Cape | 55,6 | 59,7 | 54,6 | 57,3 | 55,6 | 56,9 | 50,2 | 54,1 | 42,4 | 46,2 | 56,3 | 55,7 | 54,8 | 46,1 | 35,1 |

| Free State | 54,4 | 55,6 | 58,2 | 59 | 58,6 | 60,1 | 54,8 | 54,9 | 47,6 | 51,6 | 57,8 | 59,3 | 56,6 | 50,2 | 42,5 |

| Gauteng | 43,2 | 43,2 | 41,2 | 43,4 | 42,5 | 44,2 | 43,2 | 43,5 | 40,9 | 40,5 | 43,1 | 45 | 48 | 37,5 | 33,7 |

| KwaZulu-Natal | 33,8 | 39,8 | 43,6 | 44,8 | 43,5 | 43,5 | 42,1 | 46,3 | 38,2 | 44,2 | 49,9 | 52,4 | 51,4 | 41,6 | 28,8 |

| Limpopo | 47,4 | 52,6 | 53,9 | 48 | 56,3 | 54,2 | 52,5 | 57,7 | 44,6 | 46,2 | 55,5 | 58,3 | 58 | 47,3 | 31,8 |

| Mpumalanga | 40,8 | 57,2 | 44,1 | 42,6 | 45,7 | 45,9 | 46 | 50,6 | 42.4 | 42,6 | 47,9 | 50,5 | 53,2 | 37,3 | 25,5 |

| Northwest | 59 | 57,7 | 57,8 | 60 | 62,3 | 57,2 | 56,5 | 61,3 | 51,8 | 52,7 | 55 | 56,3 | 57,3 | 44,9 | 40 |

| Northern Cape | 41,9 | 57,4 | 57,1 | 53,2 | 52,1 | 56,6 | 50,8 | 58,9 | 48,1 | 54,4 | 56,7 | 57,1 | 61,9 | 52,3 | 44,7 |

| Western Cape | 48,3 | 49 | 49,4 | 42,5 | 41,3 | 36,6 | 35 | 34,7 | 32,4 | 32,9 | 32,5 | 34,2 | 33.4 | 30,1 | 29,7 |

| National | 45,9 | 49,8 | 49,2 | 48,7 | 49,8 | 49,2 | 46,8 | 50 | 41,8 | 44,6 | 50,3 | 51,9 | 52,1 | 42,1 | 32,7 |

Source: Shepard and Mohohlwane, 2021.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Copyright: This open access article is published under a Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 license, which permit the free download, distribution, and reuse, provided that the author and preprint are cited in any reuse.

MDPI Initiatives

Important Links

© 2024 MDPI (Basel, Switzerland) unless otherwise stated