Submitted:

10 April 2024

Posted:

11 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

DNA Methylation

DNA Damage Repair

Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tsukada, Y.; Fang, J.; Erdjument-Bromage, H.; Warren, M.E.; Borchers, C.H.; Tempst, P.; Zhang, Y. Histone Demethylation by a Family of JmjC Domain-Containing Proteins. Nature 2006, 439, 811–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klose, R.J.; Yamane, K.; Bae, Y.; Zhang, D.; Erdjument-Bromage, H.; Tempst, P.; Wong, J.; Zhang, Y. The Transcriptional Repressor JHDM3A Demethylates Trimethyl Histone H3 Lysine 9 and Lysine 36. Nature 2006, 442, 312–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloos, P.A.C.; Christensen, J.; Agger, K.; Maiolica, A.; Rappsilber, J.; Antal, T.; Hansen, K.H.; Helin, K. The Putative Oncogene GASC1 Demethylates Tri- and Dimethylated Lysine 9 on Histone H3. Nature 2006, 442, 307–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, X.; Tian, S.; Meng, Q.; Kim, H.-M. Histone Demethylase AMX-1 Regulates Fertility in a P53/CEP-1 Dependent Manner. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 929716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swahari, V.; West, A.E. Histone Demethylases in Neuronal Differentiation, Plasticity, and Disease. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2019, 59, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Lan, F.; Matson, C.; Mulligan, P.; Whetstine, J.R.; Cole, P.A.; Casero, R.A.; Shi, Y. Histone Demethylation Mediated by the Nuclear Amine Oxidase Homolog LSD1. Cell 2004, 119, 941–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wang, F.; Wan, K.; Yamane, K.; Zhang, Y.; Lei, M. Crystal Structure of Human Histone Lysine-Specific Demethylase 1 (LSD1). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2006, 103, 13956–13961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burg, J.M.; Link, J.E.; Morgan, B.S.; Heller, F.J.; Hargrove, A.E.; McCafferty, D.G. KDM1 Class Flavin-Dependent Protein Lysine Demethylases. Biopolymers 2015, 104, 213–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karytinos, A.; Forneris, F.; Profumo, A.; Ciossani, G.; Battaglioli, E.; Binda, C.; Mattevi, A. A Novel Mammalian Flavin-Dependent Histone Demethylase*. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 17775–17782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosammaparast, N.; Shi, Y. Reversal of Histone Methylation: Biochemical and Molecular Mechanisms of Histone Demethylases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2010, 79, 155–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

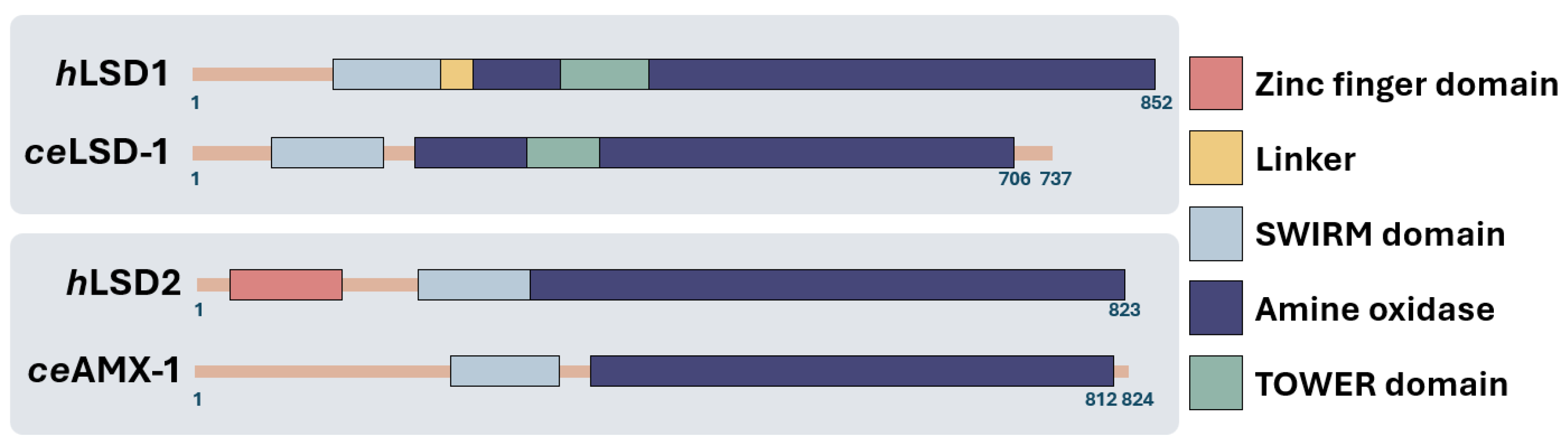

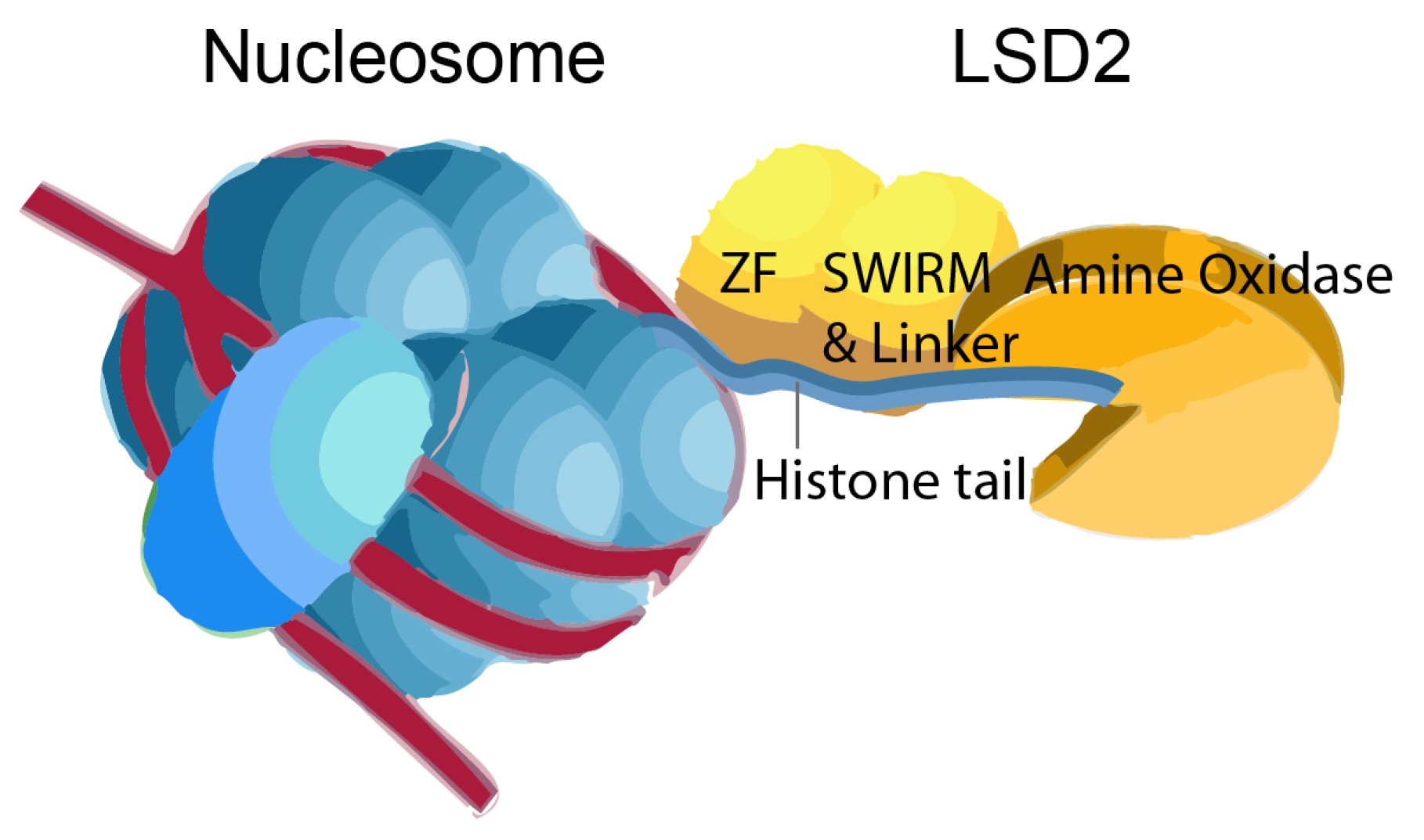

- Chen, F.; Yang, H.; Dong, Z.; Fang, J.; Wang, P.; Zhu, T.; Gong, W.; Fang, R.; Shi, Y.G.; Li, Z.; et al. Structural Insight into Substrate Recognition by Histone Demethylase LSD2/KDM1b. Cell Res. 2013, 23, 306–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, R.; Barbera, A.J.; Xu, Y.; Rutenberg, M.; Leonor, T.; Bi, Q.; Lan, F.; Mei, P.; Yuan, G.-C.; Lian, C.; et al. Human LSD2/KDM1b/AOF1 Regulates Gene Transcription by Modulating Intragenic H3K4me2 Methylation. Mol. Cell 2010, 39, 222–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Qi, S.; Xu, M.; Yu, L.; Tao, Y.; Deng, Z.; Wu, W.; Li, J.; Chen, Z.; Wong, J. Structure-Function Analysis Reveals a Novel Mechanism for Regulation of Histone Demethylase LSD2/AOF1/KDM1b. Cell Res. 2013, 23, 225–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Jiang, J.; Stewart, D.M.; Qi, S.; Yamane, K.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wong, J. AOF1 Is a Histone H3K4 Demethylase Possessing Demethylase Activity-Independent Repression Function. Cell Res. 2010, 20, 276–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Tian, S.; Beese-Sims, S.E.; Chen, J.; Shin, N.; Colaiácovo, M.P.; Kim, H.-M. Histone Demethylase AMX-1 Is Necessary for Proper Sensitivity to Interstrand Crosslink DNA Damage. PLOS Genet. 2021, 17, e1009715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciccone, D.N.; Su, H.; Hevi, S.; Gay, F.; Lei, H.; Bajko, J.; Xu, G.; Li, E.; Chen, T. KDM1B Is a Histone H3K4 Demethylase Required to Establish Maternal Genomic Imprints. Nature 2009, 461, 415–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Essen, D.; Zhu, Y.; Saccani, S. A Feed-Forward Circuit Controlling Inducible NF-κB Target Gene Activation by Promoter Histone Demethylation. Mol. Cell 2010, 39, 750–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, S.-L.; Chang, D.C.; Lin, C.-H.; Ying, S.-Y.; Leu, D.; Wu, D.T.S. Regulation of Somatic Cell Reprogramming through Inducible Mir-302 Expression. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, 1054–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katz, T.A.; Huang, Y.; Davidson, N.E.; Jankowitz, R.C. Epigenetic Reprogramming in Breast Cancer: From New Targets to New Therapies. Ann. Med. 2014, 46, 397–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, T.A.; Vasilatos, S.N.; Harrington, E.; Oesterreich, S.; Davidson, N.E.; Huang, Y. Inhibition of Histone Demethylase, LSD2 (KDM1B), Attenuates DNA Methylation and Increases Sensitivity to DNMT Inhibitor-Induced Apoptosis in Breast Cancer Cells. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2014, 146, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin Chen, S.N.V. Functional Characterization of Lysine-Specific Demethylase 2 (LSD2/KDM1B) in Breast Cancer Progression. Oncotarget 2017, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Sun, L.; Luo, Y.; He, S. Knockdown of KDM1B Inhibits Cell Proliferation and Induces Apoptosis of Pancreatic Cancer Cells. Pathol. - Res. Pract. 2019, 215, 1054–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Testa, U.; Pelosi, E.; Castelli, G. Colorectal Cancer: Genetic Abnormalities, Tumor Progression, Tumor Heterogeneity, Clonal Evolution and Tumor-Initiating Cells. Med. Sci. 2018, 6, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, J.; Zhang, Z.-M.; Xia, Y.; Liao, G.-Q.; Pan, Y.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, Z.-S. LSD1-Mediated Epigenetic Modification Contributes to Proliferation and Metastasis of Colon Cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2013, 109, 994–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, S.; Wang, J.; Zeng, W.; Cheng, X.; Liu, L.; Li, W. Lysine-Specific Histone Demethylase 1B (LSD2/KDM1B) Represses P53 Expression to Promote Proliferation and Inhibit Apoptosis in Colorectal Cancer through LSD2-Mediated H3K4me2 Demethylation. Aging 2020, 12, 14990–15001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Yin, X.; Yang, H.; Xu, Y. Histone Demethylase LSD2 Acts as an E3 Ubiquitin Ligase and Inhibits Cancer Cell Growth through Promoting Proteasomal Degradation of OGT. Mol. Cell 2015, 58, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.G.; Wynder, C.; Schmidt, D.M.; McCafferty, D.G.; Shiekhattar, R. Histone H3 Lysine 4 Demethylation Is a Target of Nonselective Antidepressive Medications. Chem. Biol. 2006, 13, 563–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binda, C.; Valente, S.; Romanenghi, M.; Pilotto, S.; Cirilli, R.; Karytinos, A.; Ciossani, G.; Botrugno, O.A.; Forneris, F.; Tardugno, M.; et al. Biochemical, Structural, and Biological Evaluation of Tranylcypromine Derivatives as Inhibitors of Histone Demethylases LSD1 and LSD2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 6827–6833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vianello, P.; Botrugno, O.A.; Cappa, A.; Dal Zuffo, R.; Dessanti, P.; Mai, A.; Marrocco, B.; Mattevi, A.; Meroni, G.; Minucci, S.; et al. Discovery of a Novel Inhibitor of Histone Lysine-Specific Demethylase 1A (KDM1A/LSD1) as Orally Active Antitumor Agent. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 1501–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicosia, L.; Boffo, F.L.; Ceccacci, E.; Conforti, F.; Pallavicini, I.; Bedin, F.; Ravasio, R.; Massignani, E.; Somervaille, T.C.P.; Minucci, S.; et al. Pharmacological Inhibition of LSD1 Triggers Myeloid Differentiation by Targeting GSE1 Oncogenic Functions in AML. Oncogene 2022, 41, 878–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

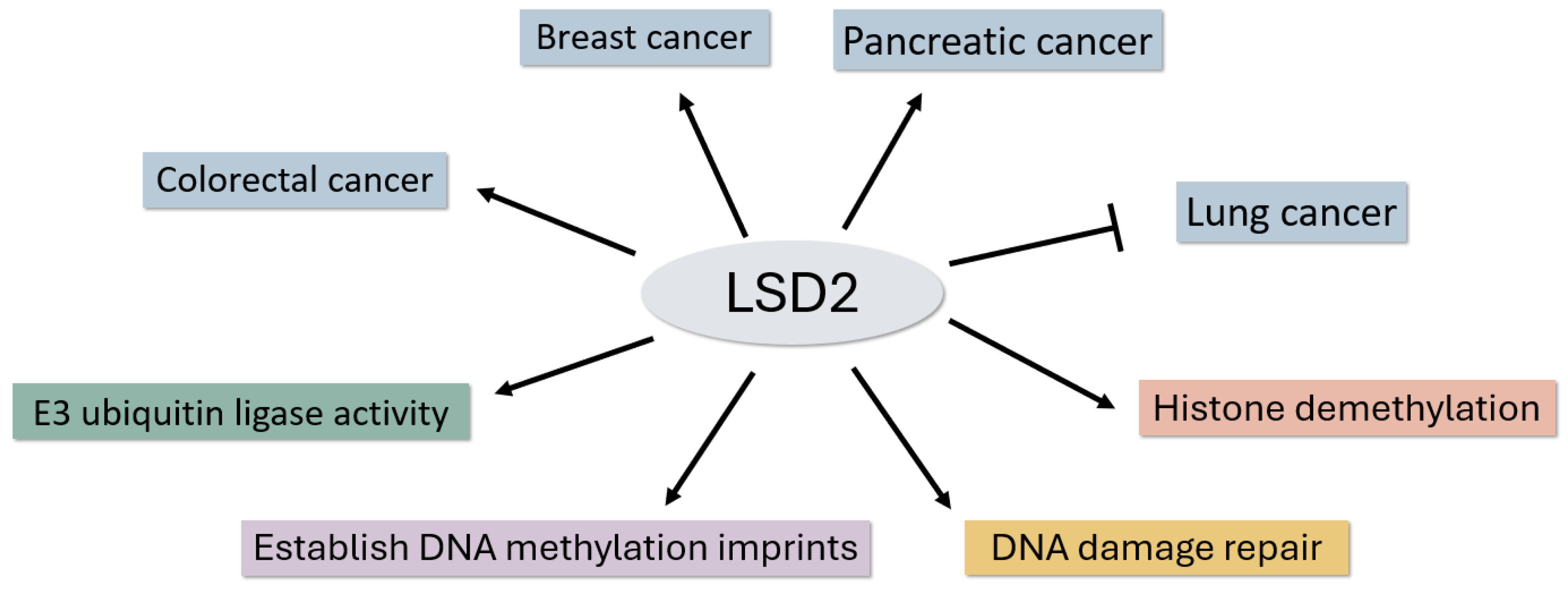

| Findings | Implication |

|---|---|

| Implicated in various cancers, with roles in promotion or suppression | Human cancer involvement: Lung, Breast, Pancreatic and Colorectal Cancer tissues or cell lines [20,21,22,25,26] |

| Involved in establishing DNA methylation imprints during oogenesis | Epigenetic regulation during oogenesis [16] |

| Implicated in non-transgenerational fertility defects in C. elegans | Role in fertility defects in model system [4] |

| Involved in ICL DNA damage repair in C. elegans | Role in DNA damage repair in model system [15] |

| Involved in E3 ubiquitin ligase activities, regulating specific genes | Role in intricate gene regulation [26] |

| Cancer Type | Experimental Results |

|---|---|

| Breast cancer | Knockdown of LSD2 inhibits breast cancer cell proliferation, migration, and invasion [21]. |

| Pancreatic Cancer | Knock down of LSD2 correlates with cell proliferation decrease and leads to apoptosis increase [22]. |

| Colorectal Cancer | Overexpression of LSD2 leads cell proliferation and apoptosis decrease [25]. |

| Lung Cancer | LSD2 inhibits lung cancer cell growth by promoting OGT degradation [26]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).