1. Introduction

Social interaction and community engagement have evolved remarkably with the advent of technology (Zhang et al., 2017). In his seminal 2000 essay (Putnam, 2000), Robert Putnam argues that television and urban sprawl have contributed to a decline in social capital and civic engagement in America over the second half of the 20th century. However, the proliferation of digital technologies, social media (Bolton et al., 2013), and internet connectivity (Li et al., 2012) have given rise to new forms of social connection, communication, and value creation. This transformation is especially evident in the behavior and preferences of Generation Z (Duffett, 2020), those born after 1995. Unlike the trends identified by Putnam, this cohort of true digital natives (Bassiouni & Hackley, 2014) is redefining social capital and engagement through their fluency in using technology to create online communities, co-create value with brands, and rely on peer opinions and reviews.

Generation Z is the first cohort to grow up entirely immersed in digital technology and social media (Duffett, 2020). As digital natives, their comfort and skill with technology distinguishes them from older generations. According to a 2018 Pew Research study (Barroso et al., 2020), 95% of teens aged 13-17 reported they have access to a smartphone and 88% have access to a desktop or laptop computer. A 2020 study by McKinsey (Kim et al., 2020) found that Gen Z spends over 7 hours per day engaging with media content across devices. Their innate familiarity with the virtual world provides Gen Z unparalleled opportunities for social connection, access to information, and creative expression.

However, some researchers (Bassiouni & Hackley, 2014; Dimock, 2019; Hossain, 2018; Kim et al., 2020)argue this immersion in the digital realm has made Gen Z more isolated and less likely to interact in person. Jean Twenge's research (Twenge, 2011) finds that adolescents who spend more time on digital devices are more likely to report mental health issues than those who engage in more face-to-face social interaction. But other researchers counter that online interaction supplements rather than replaces in-person engagement for Gen Z. A study by Monica Anderson and Jingjing Jiang (Anderson & Jiang, 2018) found 52% of teens reported social media makes them feel more connected with their friends’ feelings and daily lives. The debate continues on whether digital immersion cultivates or hinders meaningful social connection for this cohort.

Regardless, it is undeniable that Gen Z relies heavily on digital communication to develop social capital and engage with their community. On social media, they co-create value with brands by promoting products they enjoy and providing user-generated content. They rely deeply on peer reviews and influencer opinions to make purchasing decisions. Through content creation and online personas, Gen Z displays a level of virtual civic engagement that contrasts Putnam's diagnosis of an increasingly isolated society.

While studies have explored social media usage patterns across generations (Barroso et al., 2020; Twenge, 2011; Zhang et al., 2017), there remain significant gaps in understanding the nuanced ways in which Gen Z interacts with technology and how this defines their sense of identity and community. Limited research has longitudinally examined the trajectory of in-person versus online friendship development for Gen Zers compared to previous generations. Additionally, more investigation is needed to analyze how emerging technologies like artificial intelligence (AI) (Baidoo-Anu & Owusu Ansah, 2023), virtual reality (VR) (Bec et al., 2019) and augmented reality (AR) (Loureiro et al., 2020) may shape the social behaviors and preferences of Gen Z as they enter adulthood. This study aims to help fill these research gaps and further the discourse on how evolving technologies intersect with adolescent and young adult psychology.

This paper will provide an in-depth analysis of Generation Z and how their ubiquitous use of technology and social media is redefining social connection, communal value, and brand relationships. First, it will outline key demographic and psychographic characteristics that distinguish Gen Z from Millennials and other preceding generational cohorts. Their unique mindset, values, and tendencies as digital natives will be explored as critical underpinnings of their online habits and engagement. Secondly, the paper will examine Gen Z’s interaction with social media and emerging metaverse technologies. Instagram, TikTok, gaming platforms, and new immersive digital spaces are key forums where Gen Z congregates, communicates, and co-creates value through user-generated content. Different types of virtual communities and networks will be analyzed as conduits for Gen Z to build diverse social connections untethered to physical geography. The influence of peers, influencers, and viral trends on Gen Z’s purchasing decisions and brand allegiances will also be discussed.

Emerging technologies on the horizon, including artificial intelligence, virtual reality, and augmented reality, will also be discussed speculatively in terms of their potential impact on future consumer behavior. As these technologies infiltrate commerce and communication, they are likely to significantly influence how individuals across generations interface with businesses, brands, products, and each other. Gen Z, as earliest adopters, will provide key insights into consumer readiness and willingness to engage with immersive digital experiences. Subsequently, the paper will analyze what the research findings mean for businesses and marketers aiming to engage effectively with Generation Z. Strategic recommendations will be offered based on Gen Z’s preferences for digital communication, desire for personalized interactions, and reliance on influencer marketing. The importance of brand authenticity and corporate social responsibility will also be underscored, as these attributes resonate strongly with socially-conscious Gen Z consumers (Duffett, 2020).

Finally, the conclusion will summarize the paper’s key findings regarding how Gen Z is driving the evolution of social capital and engagement in the digital era. Their generational impact on consumer behavior will be contextualized within broader technological and cultural shifts. The paper will culminate with proposing future research directions to build understanding of emerging technologies’ influence on social connection and recommendations for fostering healthy digital engagement among youth.

In summary, this paper aims to provide a comprehensive analysis of Generation Z as a uniquely Generation Z whose social relationships and communal engagement play out vibrantly across technology platforms. Their unprecedented access to and facility with virtual networks provide intriguing opportunities to reimagine social capital and value co-creation in the modern age. By improving understanding of this vital cohort, their social motivations, and their digital habits, important insights will be gained to help parents, educators, policy makers, and businesses in better nurturing future generations.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Generation Z Consumers

Generation Z refers to the cohort born after Millennials in the 1990s to early 2000s, with varying proposed start dates (Addor, 2011; Iorgulescu, 2016; Seemiller & Grace, 2017; Tulgan, 2013). As the first true "digital natives," Gen Z grew up with internet-connected technology and virtual interactions as the norm (Kebritchi & Sharifi, 2016; Turner, 2015). This unprecedented access to information and global connectivity has shaped Gen Z's worldviews and imperatives (Rehman, 2017). Gen Z is also the most ethnically diverse generation in America so far (Shatto & Erwin, 2016).

According to an Accenture (2017) survey, social media wields greater influence on Gen Z consumers than previous generations. Key purchase decision factors include lowest price, product display, and user reviews. Gen Z heavily weighs suggestions from family and friends. However, an Ernst and Young (2015) study found Gen Z less brand loyal than Millennials and less price-conscious. This contradicts Accenture's conclusions, highlighting the need for further research on Gen Z's distinctive purchase motivations.

Seemiller and Grace (2017) note that while Gen Z shares some Millennial traits, they are a distinct cohort shaped by their own times. With widespread digitalization, Gen Z is forecasted to account for 40% of global consumers by 2020, representing tremendous purchasing power (Lanvin & Evans, 2016). However, academic research on Gen Z remains limited (Chillakuri & Mahanandia, 2018; Haddouche & Salomone, 2018).

Overall, Gen Z is the rising generation that came of age in a digital, globally connected era. While they share similarities with Millennials, Gen Z has distinctive characteristics still being defined. Their purchasing decisions appear strongly shaped by digital sources and social influences. However, contradictions in existing research signal a need for deeper investigation into the nuances of Gen Z consumer behavior across demographic segments and cultural contexts. As Gen Z enters adulthood, they are poised to disrupt consumer markets through their digital fluency and differentiated preferences.

2.2. Social Media and Value Co-Creation

With the rapid development of social media platforms and social interaction technologies, consumers and companies are mutually informed, connected, networked, and empowered on a tremendous scale more than ever (Luo, Zhang, & Liu, 2015). Based on information and communication technology, social media enables the integration of capabilities, competences and knowledge that underpins value co-creation among stakeholders in dynamic relationships (Srivastava & Gnyawali, 2011). Particularly, the unprecedented direct-to-consumer processes and new distribution channels based on social media platforms increasingly bridge the gap between the company and consumers (Pan & Li, 2011). Social media plays the role of systems resource integrator to provide a technological platform that facilitates resource formations through dialogue and exchanges between firms and consumers (Singaraju, Nguyen, Niininen, & Sullivan-Mort, 2016).

A recent stream of marketing literature demonstrates that consumers are no longer merely passive recipients of value propositions offered by companies, but active participants in the value co-creation process (Prahalad & Ramaswamy, 2004b). This notion suggests the value of a product or service is not solely created by the manufacturer/supplier, but jointly co-created with the consumer of the product or service (See-To & Ho, 2014). Accordingly, it emphasizes that value is embedded into the co-creation process through communication and interaction between the company and active consumers. To seek new opportunities and gain competitive advantage, many companies (e.g., Dell, Marriott, Nike, and Starbucks) take actions to engage with consumers and involve them into the process of collective value creation. Specifically, the diverse functions offered by social media platforms (e.g., identity, conversations, sharing, reputation, groups) allows consumers and firms to more seamlessly integrate their own resources for the mutual benefit of all actors in service exchanges (Singaraju et al., 2016).

The aforementioned characteristics of the Generation Z and the unique characteristics of young Chinese consumers can, under certain cultural and social conditions, offer numerous opportunities for both local and international companies to engage with the Generation Z to co-create and enhance perceived value by innovating means of social media usage. As noted previously, one description of the Generation Z is premised on the observation that most members grew up with the computer/internet. As such, they have mastered its use for many aspects of their lives, particularly communication. These digital natives, who are either students or relatively recent entrants to the workforce, are often described as technologically savvy and the most visually sophisticated of any generation. The need to interact with others is a key reason for the Generation Z’s use of social media (Zhang et al., 2017). Social media users 20 to 37 years old are more likely than older age groups to prefer adoption of social media for interactions with acquaintances, friends and family. They are also more likely to value others’ opinions in social media and to feel important when they provide feedback about the brands or products they use. These characteristics seem to be even more pronounced within the Chinese subset of the Generation Z.

3. Method

The research focuses on two research questions. First, how does China’s Generation Z consumers co-create values through social media? Second, why do they engage with social media to co-create values with the firm? To shed light on the research conceptualization and the motives behind the attitudinal and behavioral intentions towards value co-creation, the study follows the recommendations for scale development (DeVellis, 2016) and adopts motivational analysis to identify the motives behind the value co-creation behaviors via social media. The procedures for scale development are discussed in detail in the subsequent paragraphs.

3.1. Qualitative Inquiry and Scale Development

Qualitative methods are used to enable researchers to understand the complex, inter-related patterns, relationships, and issues. Qualitative marketing research provides information useful in developing marketing strategies, communication, idea generation, product and concept development, and the development of questionnaires (Carson, Gilmore, Perry, & Gronhaug, 2001; Dubois & Gadde, 2002). We chose the qualitative methodology to explore the factors that influence China’s young consumers to embrace social media to engage with companies. Specifically, we used in-depth interviews to examine study subject attitudes, social norms, and competence that either encouraged or discouraged engagement activities. In-depth interviews enable researchers to understand target subjects by making inquiries into how and why certain activities happen. Thus, the in-depth interview methodology fits well with our study scope and purpose.

The informants selected for this study are members of the Generation Z who were born after 1990 and have been active users of social media to co-create values with firms and other stakeholders. Due to the study budget, the informant selection employed a convenience sampling technique. Total of 110 university students in Beijing and Shanghai, China were recruited through interviews. In order to target China’s Generation Z group, personal background was examined to ensure participants were born and raised in China. The average participant was 25 years old, with the interviewee gender distribution of 48% male vs. 52% female. Half (50%) of the interviewees performed value co-creation through social media for 4-6 years.

A human ecological perspective, which recognizes the complex and interdependent nature of people and their environment, guides the researcher in developing the interview guide. A semi-structured interview guide was developed to ascertain the multiple roles that study participants might play in the adoption of social media to co-create value with companies. The researcher used the interview guide to collect data from China’s young consumers regarding attitudes and beliefs about the value co-creation activities performed on the social media platforms. Each interview lasted one-and-a-half to two hours. Participants were asked to reflect on a recent (within the past six months) social media experience related to value co-creation activities which served as the basis for completing the survey. They were then asked to describe the circumstances that led to their engagement with value co-creation using social media platforms and to describe the reason(s) they thought would impact their adoption of social media utilization to engage with the companies. The description was used to get the respondent to clearly think about the specific social media experience for value co-creation activities before answering the questions of interest in this study. Measuring customers’ actual behaviors rather than behavioral intentions also contributes to the current state of knowledge about social media usage for value co-creation activities. This knowledge is gained by providing a better understanding of the customer’s point of view, which can inform companies interested in the influential factors leading to the Generation Z’s engagement with the company. Once understood, the value co-creation purposes can be used to improve the value co-creation process.

According to Creswell and Creswell (2017), the results of interviews and the transcripts must be thoroughly reviewed to identify the different topics and issues described by the respondents. Following Creswell and Creswell (2017), analysis began with several readings of each transcript for subsequent open coding. Similarities and differences among the respondent’s comments create categorical data which are then aggregated into themes (i.e., specific value co-creation activities). Finally, themes were developed and compared with published literature. The responses for each of the themes were reviewed and influential factors were identified within the responses. Influential factors were classified and relationships with other scripts or outcomes were noted.

Table 1 depicts the measurement statements for China’s Generation Z’s value co-creation behaviors through social media.

Based on the analysis, four items were categorized into the theme “seek information about the company/brand via social media”. These items summarize seeking information through social media and consist of: 1) search company news, 2) look for product/service updates, 3) watch video ads, and 4) follow the company’s social media page. “Provide feedback to the company/brand via social media” was identified as another emerging theme of value co-creation behaviors. It consists of four items that address actions taken by consumers to inform the company via social media: 1) take surveys, 2) provide comments about good service experience, 3) provide comments about bad service experiences, and 4) posting “likes”. The theme “suggest improvements to the company/brand via social media” is comprised of three items: 1) let the company know the customer’s idea, 2) comment on the posts, and 3) send messages to the company. “Spread positive eWOM about the company/brand via social media” emerged as one of the important factors for co-creation behaviors. Four items were generated under this theme: 1) recommend this company to others, 2) share positive views, 3) hashtag this company, and 4) refer this company to friends. Additionally, “seek help from the company via social media” was identified as another underlying theme consisting of three items: 1) contact the company when issues are encountered, 2) send messages when problems occur, and 3) post comments about questions.

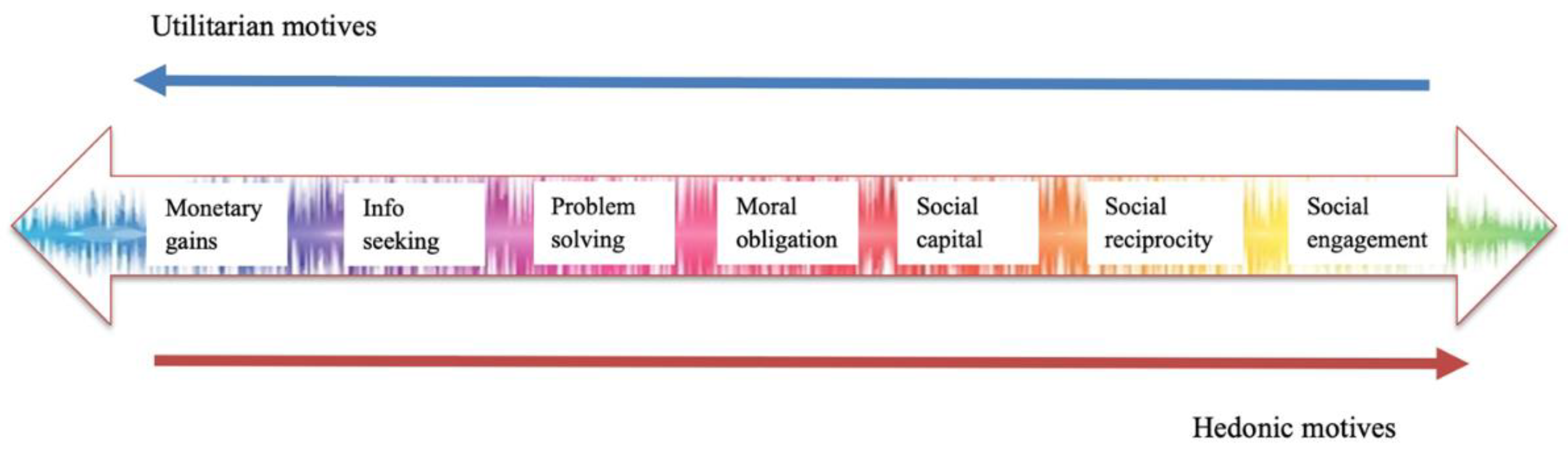

3.2. Crafting the Spectrum of Hedonic and Utilitarian Motives of Value Co-Creation through Social Media

Additionally, conceptual definitions of the motives following the spectrum of utilitarian and hedonic motivational factors from the qualitative data were developed. The spectrum is outlined and discussed in light of theoretical advancements in the following paragraphs.

Motivations are the basis for how individuals behave and make choices. Psychologists and social scientists have categorized motivations into utilitarian and hedonic aspects ( Hartman, Shim, Barber, & O'Brien, 2006). Initial consumer behavior studies recognized the utilitarian aspect and proclaimed that consumers make rational preferences and act upon their functional objectives (Batra & Ahtola, 1991). Later studies questioned the information processing view and raised the concept of experiential view to pinpoint the neglected aspects—fantasies, feelings, and fun that emerged during consumers’ activities. (Babin, Darden, & Griffin, 1994). Hence, the hedonic dimension of consumer behavior was emphasized in regard to the multi-sensory, fantasy, and emotive sights. According to the qualitative data collected from the in-depth interviews supplemented by the related literature review, the researchers identified seven motives for China’s young consumers to engage in value co-creation through social media. Namely: monetary gains, information seeking, problem solving, moral obligations, social capital, social reciprocity, and social engagement. Based on respondent provided assessments, the spectrum of utilitarian and hedonic motives (see

Figure 1) was created as follows.

Monetary gains. Over 80% of participants reported that they gained monetary benefits from the company when they engaged in value co-creation through social media. This is consistent with Grönroos and Helle (2010)’s assertion that value has a monetary dimension. Accordingly, consumer’s perceptions of the monetary value dimension is dependent on how the technical value dimension is affected by the supplier. For example, companies provided digital coupons, “digital points” redeemable for special discounts, money awards for providing service/product feedback, or for sharing shopping/product experiences on social media. Among participants who mentioned monetary gains they perceived resulted from value co-creation activities, each categorized the factor into utilitarian motive rather than hedonic motive.

Information seeking. Information seeking was discussed frequently during participant interviews. Sixty percent of participants mentioned “getting useful information”, “getting to know the news”, and “keeping updated about what is happening with the brand/company” during their interviews with the researcher. Likewise, Dennis, Bourlakis, Alamanos, Papagiannidis & Brakus (2017) suggested that information seeking is one of the important factors involved in the value co-creation process. When asked to assign perceived percentages related to information seeking, the average score given by respondents was 90% utilitarian and 10% hedonic. Respondents reported that they acquired useful information from value co-creation activities while also feeling slightly pleasant and emotive arousal when they gained the desired information by communicating with the firm through social media.

Problem solving. The qualitative results indicate that another motivation for customers to engage with social media to co-create values with the firm was problem solving. The emerging dialogues on social media imply shared learning and equal communication between problem solvers (Prahalad & Ramaswamy, 2004b). Thirty percent of participants reported that problems with products/services were satisfactorily resolved through communication with the firm(s) through social media. Respondents rated problem solving as, on average, 80% utilitarian and 20% hedonic when asked to assess motivation composition. Through interaction with firms via online social networking sites, respondents reported resolving their problems/concerns, which ultimately translated to co-creating value. They reported that they had a pleasant experience and felt emotionally satisfied when they co-created value with the firm using various social networking platforms.

Moral obligations. The qualitative interviews revealed that 50% of participants felt obligated to report failures/defects to the company in order to help improve services/products. Derived from principlism, moral obligation represents a commitment to online communities conveying a sense of duty to help peers due to the shared membership (Cheung & Lee, 2012). According to their reports, participants thought it was the right thing to share their comments and answer other customers’ concerns/questions given such behaviors are meaningful and significant to their life and belief. Respondents reported that when deciding to send feedback and/or complaints to the firm through social media, they felt sharp about themselves and expected significant results from value co-creation activities, of which both utilitarian and hedonic aspects were perceived.

Social capital. Based on interview results, 60% of participants reported the social capital—networks of relationships among the brand/company’s consumer communities they expected to gain when they co-create value with the firm through social media. Consumers often provide survey/feedback starting they perceive elevates them within the community circle and affords more chances to interact with likeminded consumers or other stakeholders. Sharing resources among members of a network shapes social capital and becomes a source of value generation (Gummesson & Mele, 2010). The motive associated with developing social capital was categorized as 40% utilitarian and 60% hedonic by the respondents. The rationale for this categorization was that both rational judgement and experiential pleasure occur within the value co-creation activities facilitated by the virtual social communities.

Social reciprocity. Half of interviewed consumers (50% of the respondents) identified social reciprocity as another motive for engaging with value co-creation through social media. According to service-dominant logic, value is dynamically co-created with consumers on the basis of reciprocal service provision (Vargo & Lusch, 2004). Interaction in a social system establish mental models of others’ behaviors (Berger & Luckmann, 1967), and these models become habituated into reciprocal relationships over time (Edvardsson, Tronvoll, & Gruber, 2011). Value co-creation cultivates back-and-forth social interactions based on perceived mutual benefits and influences upon one another. The factor social reciprocity was recognized largely as hedonic with, to a lesser degree, a utilitarian aspect perceived as s sensible recognition that one should return favors received from others.

Social engagement. A solid majority of respondents (70% of interviewees) indicated they felt socially engaged when they co-create values through social media. In accordance with Flint (2006)’s analysis, value is not static; over time, it emerges and changes for individuals as they engage in social interactions. According to interview dialogues, participants feel immersed in the socially-friendly community/society when they are encouraged to express themselves and to connect with likeminded friends. Additionally, each of the respondents who mentioned the factor of social engagement categorized this motive as a 100% hedonic motivational aspect. When engaging socially, consumers feel emotionally aroused and experience pleasant feelings of friendship and harmony with the online social community.

4. Implications

4.1. Theoretical Implications

This study contributes to the understanding of the Generation Z, value co-creation and social media literature in three areas.

First, this study explored perceived co-created values from a customer perspective based using social networking sites. This finding confirmed that consumers must be considered as the most important component of human-technology interaction in the service encounter (Edvardsson, Tronvoll, & Gruber, 2011; Lemon & Verhoef, 2016). Service encounter interactions involve various strategies including social media marketing (Kim & Ko, 2012). The role of the customer is critical in value co-creation during service exchange. Our study supports the research which recognizes that the significance of customer perceptions in a service context both traditional and social media contexts.

Second, we developed a social media co-creation value scale. Motivational analysis of social media engagement to co-create values was then performed. A spectrum of utilitarian and hedonic motives in various value co-creation behaviors via social media was identified. The seven values identified from this study in the spectrum are: monetary gains, information seeking, problem solving, moral obligations, social capital, social reciprocity, and social engagement. These identified values also confirm previous studies. For example, the social engagement and social capital elicited in this study is in-line with the findings regarding relationship equity by Kim and Ko (2012). Our findings also support the three phases of the service encounter journey (pre-core, core, and post-core) noted by Voorhees, et. al., (2017). The seven co-created values elicited by our study describe what customers perceive as necessary for a positive social networking site experience.

Third, this study explores perceived social media co-creation values in the context of China’s Generation Z. The seven co-creation values confirmed the view of Larivière, et. al. (2017) that the customer segment, product/service category and stage of the customer experience process are interdependent. They further emphasized the need to explore specific user segments; specifically, younger customers who use, share, and interact with business providers on social networking sites. As Larivière, et. al. stated, “The position, role and interactions of customers within various social systems can have a major impact on the development of their operant resources, and on their ability to use operand resources during value co-creation” (p. 20). Thus, our study focusing on China’s Generation Z echoes this research. Our findings highlight the behaviors of Chinese customers who utilize electronic platforms and their service exchange experiences with providing organizations. In addition to identifying the role customers play as co-creators of value, this study identified perceived social capital values. The perceived social capital values confirm both the bonding and bridging social capitals that Chang and Zhu (2012) revealed influence the perceptions and expectations of service value among Chinese SNS users.

4.2. Practical Implications

Our findings provide several practical implications. The seven domains of the Utilitarian and Hedonic Motives Spectrum can provide companies valuable insights into customer motives and values which can be used to better compete in target markets. The findings also signal to companies that customers not only are willing to seek out information to engage in mutually beneficial problem solving, but they also form strong social network bonds thus enhancing their social capital with the company. By acting on this knowledge, companies can more effectively fulfill customer needs. SNS is, and will continue to be, an effective platform for interacting with customers. However, social media sites must respond to the market needs and evolving customer expectations. This can be achieved by soliciting feedback and engaging customers in the service experience.

Another practical implication of this study is to prompt a re-examination of the premise established in Putnam’s (2000) “Bowling alone” essay that Americans were becoming less socially engaged in community activities and organizations. Although this view pertained to American society, it did not anticipate the rise of the Generation Z and rapid global acceptance of SNS. Through SNS based co-creation value activities, western members of the Generation Z are joining electronic communities where members feel they are connected and can affect change. In contrast to United States, SNS compliments China’s culture, especially as it pertains to the Generation Z. Specifically, it enhances the interaction that is valued by those born into the era of China’s one child policy. Members of this generation are considered to value the Confucian philosophy of harmony – a goal obtained through returning favors to others in the form of online feedback. Additional differences are also likely to exist based on culture, environment and citizenry (Skoric, Ying, D., & Ng, Y. (2009).

In the context of this study, the conclusion that SNS provides individual consumers with a new means to connect – replacing traditional clubs and organizations with remote, but none-the-less meaningful ways to become a part of a community including companies’ SNS, fan pages. Let’s stop bowling alone, and start engaging a team of customers, services providers and others on social media networking sites.

5. Limitations and Future Research

Despite our contribution to the social media literature and practical implications in services management, several limitations exist. First, generalization of the findings. Our study is based on qualitative in-depth interviews with members of the Generation Z who were experienced using SNS. As such, the resulting scales and motivational spectrum cannot be generalized to all members of the Generation Z. Future research to explore and apply this scale and the motivational spectrum by taking a quantitative research approach is recommended.

Another limitation associated with this study is that it focused on the Generation Z in China, a collectivism culture. Further investigation in other societies and cultures (i.e., western individualism cultures; other cohorts/generations, etc.) will further validate these findings.

Furthermore, exploration of additional diverse social networking sites and user experience levels ranging from frequent users to causal users is also recommended. Other variables related to behavioral and experiential context will also contribute to increased understanding of customer engagement in social media; especially in the context of building social capital.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Tingting Zhang; methodology, Hongxuan Yu; software, Tingting Zhang; formal analysis, Tingting Zhang; investigation, Hongxuan Yu; resources, Hongxuan Yu; writing—original draft preparation, Tingting Zhang and Hongxuan Yu writing—review and editing, Tingting Zhang and Honguan Yu; visualization, Tingting Zhang. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.” Please turn to the CRediT taxonomy for the term explanation. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Anderson, M., & Jiang, J. (2018). Teens, social media & technology 2018. Pew Research Center, 31(2018), 1673–1689.

- Batra, R.; Ahtola, O.T. Measuring the hedonic and utilitarian sources of consumer attitudes. Mark. Lett. 1991, 2, 159–170, . [CrossRef]

- Berger, P. L., & Luckmann, T. (1967). The social construction of reality: a treatise in the sociology of knowledge. London: Penguin.

- Bolton, R.N.; Parasuraman, A.; Hoefnagels, A.; Migchels, N.; Kabadayi, S.; Gruber, T.; Loureiro, Y.K.; Solnet, D. Understanding Generation Y and their use of social media: a review and research agenda. J. Serv. Manag. 2013, 24, 245–267, . [CrossRef]

- Brosdahl, D.J.; Carpenter, J.M. Shopping orientations of US males: A generational cohort comparison. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2011, 18, 548–554, . [CrossRef]

- Bai̇doo-Anu, D.; Ansah, L.O. Education in the Era of Generative Artificial Intelligence (AI): Understanding the Potential Benefits of ChatGPT in Promoting Teaching and Learning. J. AI 2023, 7, 52–62, . [CrossRef]

- Barroso, A., Parker, K., & Bennett, J. (2020). As millennials near 40, they’re approaching family life differently than previous generations. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2020/05/PDST_05.27.20_millennial.families_fullreport.pdf.

- Bassiouni, D. H., & Hackley, C. (2014). ’Generation Z’children’s adaptation to digital consumer culture: A critical literature review. Journal of Customer Behaviour, 13(2), 113–133.

- Bec, A.; Moyle, B.; Timms, K.; Schaffer, V.; Skavronskaya, L.; Little, C. Management of immersive heritage tourism experiences: A conceptual model. Tour. Manag. 2018, 72, 117–120, . [CrossRef]

- Bolton, R.N.; Parasuraman, A.; Hoefnagels, A.; Migchels, N.; Kabadayi, S.; Gruber, T.; Loureiro, Y.K.; Solnet, D. Understanding Generation Y and their use of social media: a review and research agenda. J. Serv. Manag. 2013, 24, 245–267, . [CrossRef]

- Carson, D., Gilmore, A., Perry, C., & Gronhaug, K. (2001). Qualitative marketing research. Sage. Retrieved from http://books.google.com/books?hl=zh-CN&lr=&id=L8nSK5QEeGEC&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=%22Qualitative+marketing+research%22&ots=I_mqmykwtN&sig=8eEBrTFuVGbOxsXmPQe2uzrd1SM.

- Chang, Y.P.; Zhu, D.H. The role of perceived social capital and flow experience in building users’ continuance intention to social networking sites in China. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2012, 28, 995–1001, . [CrossRef]

- Cheung, C.M.; Lee, M.K. What drives consumers to spread electronic word of mouth in online consumer-opinion platforms. Decis. Support Syst. 2012, 53, 218–225, . [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2017). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage publications.

- Carson, D., Gilmore, A., Perry, C., & Gronhaug, K. (2001). Qualitative marketing research. Sage. http://books.google.com/books?hl=zh-CN&lr=&id=L8nSK5QEeGEC&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=%22Qualitative+marketing+research%22&ots=I_mqmykwtN&sig=8eEBrTFuVGbOxsXmPQe2uzrd1SM.

- Czepiel, J.A. Service encounters and service relationships: Implications for research. J. Bus. Res. 1990, 20, 13–21, . [CrossRef]

- Dennis, C.; Bourlakis, M.; Alamanos, E.; Papagiannidis, S.; Brakus, J.J. Value Co-Creation Through Multiple Shopping Channels: The Interconnections with Social Exclusion and Well-Being. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2017, 21, 517–547, . [CrossRef]

- DeVellis, R.F. Scale Development: Theory and Applications, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: Saunders Oaks, CA, USA, 2016; pp. 50–100.

- Dimock, M. (2019). Defining generations: Where Millennials end and Generation Z begins. Pew Research Center, 17(1), 1–7.

- Duffett, R. The YouTube Marketing Communication Effect on Cognitive, Affective and Behavioural Attitudes among Generation Z Consumers. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5075, . [CrossRef]

- Dubois, A.; Gadde, L.-E. Systematic combining: an abductive approach to case research. J. Bus. Res. 2002, 55, 553–560, . [CrossRef]

- Edvardsson, B.; Tronvoll, B.; Gruber, T. Expanding understanding of service exchange and value co-creation: a social construction approach. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2010, 39, 327–339, . [CrossRef]

- Flint, D.J. Innovation, symbolic interaction and customer valuing: thoughts stemming from a service-dominant logic of marketing. Mark. Theory 2006, 6, 349–362, . [CrossRef]

- Grönroos, C., & Helle, P. (2010). Adopting a service logic in manufacturing: Conceptual foundation and metrics for mutual value creation. Journal of Service Management, 21(5), 564-590.

- Gummesson, E.; Mele, C. Marketing as Value Co-creation Through Network Interaction and Resource Integration. J. Bus. Mark. Manag. 2010, 4, 181–198, . [CrossRef]

- Hartman, J.B.; Shim, S.; Barber, B.; O'Brien, M. Adolescents' utilitarian and hedonic Web consumption behavior: Hierarchical influence of personal values and innovativeness. Psychol. Mark. 2006, 23, 813–839, . [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M. (2018). Understanding the attitude of generation z consumers towards advertising avoidance on the internet. European Journal of Business and Management, 10(36), 86–96.

- Kim, A.J.; Ko, E. Do social media marketing activities enhance customer equity? An empirical study of luxury fashion brand. J. Bus. Res. 2011, 65, 1480–1486, . [CrossRef]

- empirical study of luxury fashion brand. Journal of Business Research, 65(10), 1480-1486.

- Kim, A., McInerney, P., Smith, T. R., & Yamakawa, N. (2020). What makes Asia–Pacific’s generation Z different. McKinsey & Company, 1–10.

- Larivière, B., Bowen, D., Andreassen, T. W., Kunz, W., Sirianni, N. J., Voss, C., ... & De Keyser, A. (2017). “Service Encounter 2.0”: An investigation into the roles of technology, employees and customers. Journal of Business Research, 79, 238-246.

- Lemon, K.N.; Verhoef, P.C. Understanding Customer Experience Throughout the Customer Journey. J. Mark. 2016, 80, 69–96, . [CrossRef]

- Li, M., Dong, Z. Y., & Chen, X. (2012). Factors influencing consumption experience of mobile commerce: A study from experiential view. Internet Research, 22(2), 120–141.

- Loureiro, S.M.C.; Guerreiro, J.; Ali, F. 20 years of research on virtual reality and augmented reality in tourism context: A text-mining approach. Tour. Manag. 2019, 77, 104028, . [CrossRef]

- Luo, N.; Zhang, M.; Liu, W. The effects of value co-creation practices on building harmonious brand community and achieving brand loyalty on social media in China. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 48, 492–499, . [CrossRef]

- Pan, B.; Li, X.(. The long tail of destination image and online marketing. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 132–152, . [CrossRef]

- Annals of Tourism Research, 38(1), 132–152.

.

- Prahalad, C. K., & Ramaswamy, V. (2000). Co-opting customer competence. Harvard Business Review, 78(1), 79–90.

- Prahalad, C. K., & Ramaswamy, V. (2002). The co-creation connection. Strategy and Business, 50–61.

- Prahalad, C.K.; Ramaswamy, V. Co-creation experiences: The next practice in value creation. J. Interact. Mark. 2004, 18, 5–14, . [CrossRef]

- Prahalad, C.; Ramaswamy, V. Co-creating unique value with customers. Strat. Leadersh. 2004, 32, 4–9, . [CrossRef]

- Prensky, M. Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants Part 1. Horiz. 2001, 9, 1–6, . [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R. D. (1995). Bowling alone: America" s declining social capital. Journal of Democracy, 6, 65-78.

- Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling alone: America’s declining social capital. In Culture and politics (pp. 223-234). Palgrave Macmillan, New York.

- Schultz, H., Ph.D, M. P. B., & Ph.D, D. E. S. (2013). Understanding China’s Generation Z: A marketer’s guide to understanding young Chinese consumers (1 edition). Prosper Business Development Corporation.

- See-To, E.W.; Ho, K.K. Value co-creation and purchase intention in social network sites: The role of electronic Word-of-Mouth and trust – A theoretical analysis. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 31, 182–189, . [CrossRef]

- Singaraju, S.P.; Nguyen, Q.A.; Niininen, O.; Sullivan-Mort, G. Social media and value co-creation in multi-stakeholder systems: A resource integration approach. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2016, 54, 44–55, . [CrossRef]

- Skoric, M.M.; Ying, D.; Ng, Y. Bowling Online, Not Alone: Online Social Capital and Political Participation in Singapore. J. Comput. Commun. 2009, 14, 414–433, . [CrossRef]

- political participation in Singapore. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 14(2), 414-433.

- Srivastava, M.K.; Gnyawali, D.R. When Do Relational Resources Matter? Leveraging Portfolio Technological Resources for Breakthrough Innovation. Acad. Manag. J. 2011, 54, 797–810, . [CrossRef]

- Soares, R.R.; Zhang, T.T.(.; Proença, J.F.; Kandampully, J. Why are Generation Y consumers the most likely to complain and repurchase?. J. Serv. Manag. 2017, 28, 520–540, . [CrossRef]

- Twenge, J.M. Generational differences in mental health: Are children and adolescents suffering more, or less?. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2011, 81, 469–472, . [CrossRef]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. Evolving to a New Dominant Logic for Marketing. J. Mark. 2004, 68, 1–17, . [CrossRef]

- Voorhees, C. M., Fombelle, P. W., Gregoire, Y., Bone, S., Gustafsson, A., Sousa, R., &.

- Voorhees, C.M.; Fombelle, P.W.; Gregoire, Y.; Bone, S.; Gustafsson, A.; Sousa, R.; Walkowiak, T. Service encounters, experiences and the customer journey: Defining the field and a call to expand our lens. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 79, 269–280, . [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; Gong, T. Customer value co-creation behavior: Scale development and validation. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1279–1284, . [CrossRef]

- Zemke, R., Raines, C., & Filipczak, B. (2013). Generations at work: Managing the clash of Boomers, Gen Xers, and Gen Yers in the workplace. AMACOM Div American Mgmt Assn.

- Zhang, T.(.; Omran, B.A.; Cobanoglu, C. Generation Y’s positive and negative eWOM: use of social media and mobile technology. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 732–761, . [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T. C., Jahromi, M. F., & Kizildag, M. (2018). Value co-creation in a sharing economy: The end of price wars? International Journal of Hospitality Management, 71, 51–58.

- Zhang, T.(.; Lu, C.; Kizildag, M. Engaging Generation Y to Co-Create Through Mobile Technology. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2017, 21, 489–516, . [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).