Submitted:

11 April 2024

Posted:

14 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

1.1. Study Design

1.2. Period and Location of the Study

1.3. Population or Sample, Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

1.4. Study Instrument

1.5. Data Collection and Operational Strategies

1.5.1. Vaccination Completeness

1.6. Statistical Analysis

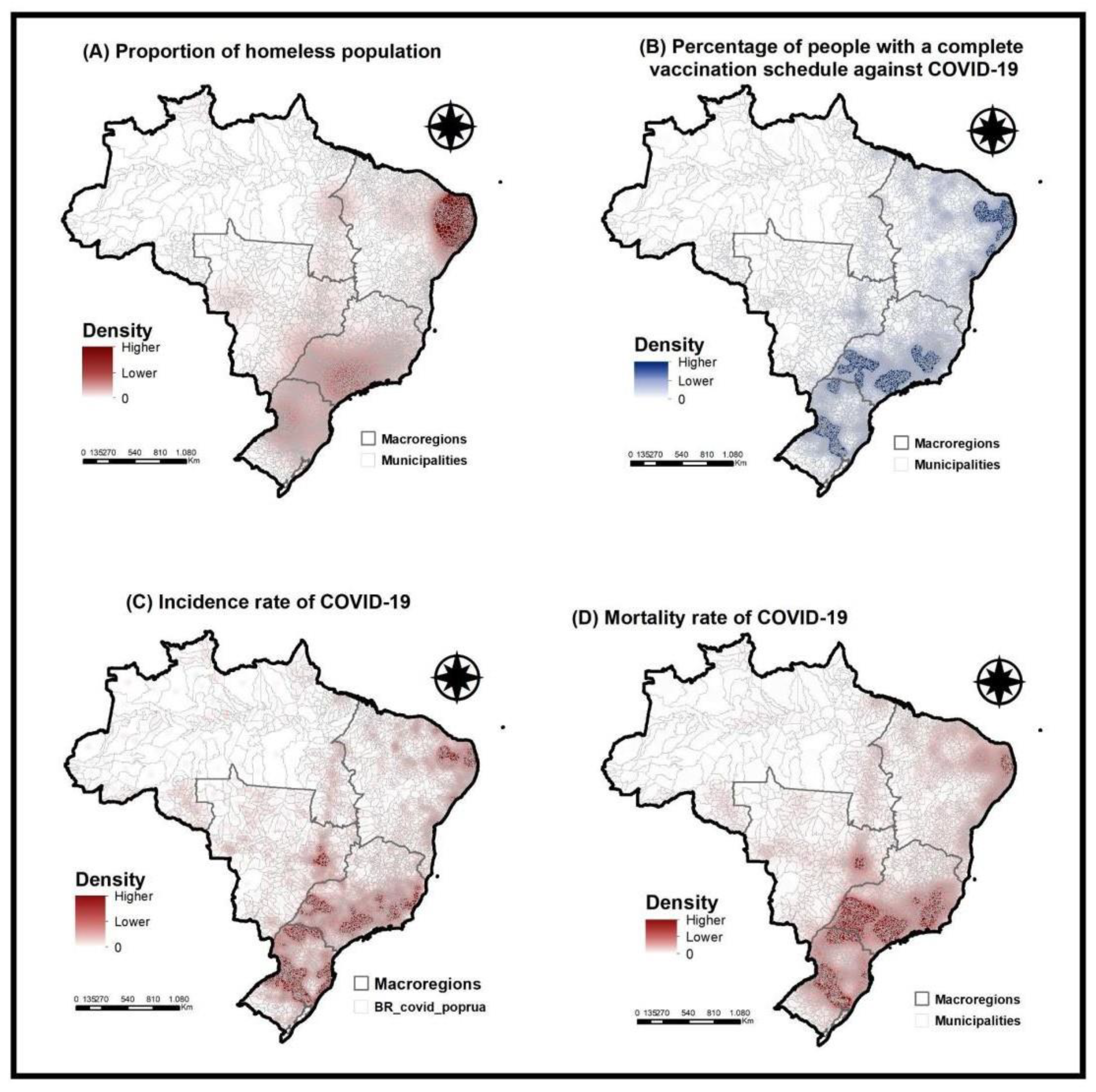

1.6.1. Stage I - Situational Diagnosis

1.6.2. Stage II - Primary Data Analysis

1.7. Ethical Aspects

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vilhena A, Bardanachvili E. National Immunization Program (PNI) and Covid-19: challenges to a history of almost half a century of success. Fiocruz Antonio Ivo de Carvalho Center for Strategic Studies. 2021. https://cee.fiocruz.br/?q=Programa- Nacional-de-Imunizacoes-PNI-e-Covid-19 (accessed April 7, 2024).

- Souza LEPF de, Buss PM. Global challenges for equitable access to COVID-19 vaccination. Cad Saúde Pública 2021;37:e00056521. [CrossRef]

- Brazil. Recommendations for the prevention and control of COVID-19 due to the increase in cases of the disease and the circulation of new subvariants of Omicron (VOC). Information Note. State Health Surveillance Center. Rio Grande do Sul Health Department. 2022.

- Brazil. Operational Technical Report on Vaccination Against Covid-19. Ministry of Health. 2023. https://www.gov.br/saude/pt-br/assuntos/covid-19/informes- tecnicos/2023/informe-tecnico-operacional-de-vacinacao-contra-a-covid-19/view (accessed April 7, 2024).

- Brito, C.; da Silva, L.N.; Xavier, C.C.L.; Antunes, V.H.; Costa, M.S.; Filgueiras, S.L. The way of life of the unhoused people as an enhance for COVID-19 care. Rev. Bras. de Enferm. 2021, 74, e20200832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, L.J.F.; Aragão, F.B.A.; Cunha, J.H.D.S.; Carneiro, T.G.; Fiorati, R.C. Accessibility and quality of life of homeless people and primary care. Revista Família, Ciclos de Vida e Saúde no Contexto Social 2022, 10, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honorato, B.E.F.; Oliveira, A.C.S. Homeless people and COVID-19. Rev Adm Pública 2020, 54, 1064–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natalino M. Nota Técnica no 103. Estimativa da Populacão em Situação de Rua no Brasil (2012-2022). Directorate of Social Studies and Policies (Disoc) 2023.

- Meehan, A.A.; Yeh, M.; Gardner, A.; DeFoe, T.L.; Garcia, A.; Kelen, P.V.; Montgomery, M.P.; Tippins, A.E.; Carmichael, A.E.; Gibbs, C.R.; et al. COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptability Among Clients and Staff of Homeless Shelters in Detroit, Michigan, February 2021. Heal. Promot. Pr. 2021, 23, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahillan, T.; Emmerson, M.; Swift, B.; Golamgouse, H.; Song, K.; Roxas, A.; Mendha, S.B.; Avramović, E.; Rastogi, J.; Sultan, B. COVID-19 in the homeless population: a scoping review and meta-analysis examining differences in prevalence, presentation, vaccine hesitancy and government response in the first year of the pandemic. BMC Infect. Dis. 2023, 23, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramovich, A.; Pang, N.; Kunasekaran, S.; Moss, A.; Kiran, T.; Pinto, A.D. Examining COVID-19 vaccine uptake and attitudes among 2SLGBTQ+ youth experiencing homelessness. BMC Public Heal. 2022, 22, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacoella, C.; Ralli, M.; Maggiolini, A.; Arcangeli, A.; Ercoli, L. Acceptance of COVID-19 vaccine among persons experiencing homelessness in the City of Rome, Italy. Eur Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci 2021, 25, 3132–3135. [Google Scholar]

- Goode, J.-V.R.; Cook, P.; Cuttino, S.; Gatewood, S.B.S. Early experience with COVID-19 vaccine in a Federally-Qualified Healthcare Center for the homeless. Vaccine 2021, 39, 7131–7134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.A.; Alagbo, H.O.; Hassan, T.A.; Mera-Lojano, L.D.; Abdelaziz, E.O.; The, N.P.N.; Makram, A.M.; Makram, O.M.; Elsheikh, R.; Huy, N.T. Vaccine acceptance, determinants, and attitudes toward vaccine among people experiencing homelessness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect. Dis. 2023, 23, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roederer, T.; Mollo, B.; Vincent, C.; Leduc, G.; Sayyad-Hilario, J.; Mosnier, M.; Vandentorren, S. Estimating COVID-19 vaccine uptake and its drivers among migrants, homeless and precariously housed people in France. Commun. Med. 2023, 3, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Sun, Q.; Liu, Q.; Pang, Y.; Tang, S. SARS-CoV-2 incidence, seroprevalence, and COVID-19 vaccination coverage in the homeless population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Public Heal. 2023, 11, 1044788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolfarine H, Bussab WDO. Elements of sampling. São Paulo: Edgar Blücher; 2005.

- Etikan, I.; Musa, S.A.; Alkassim, R.S. Comparison of Convenience Sampling and Purposive Sampling. Am. J. Theor. Appl. Stat. 2016, 5, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedro, A.R.; Gama, A.; Soares, P.; Moniz, M.; Laires, P.A.; Dias, S. COVID-19 Barometer: Social Opinion – What Do the Portuguese Think in This Time of COVID-19? Port. J. Public Heal. 2020, 38, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, J.B.V.; de Freitas, D. Método DELPHI: caracterização e potencialidades na pesquisa em Educação. 2018, 29, 389–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarili, T.F.T.; Castanheira, E.R.L.; Nunes, L.O.; Sanine, P.R.; Carrapato, J.F.L.; Machado, D.F.; Ramos, N.P.; Mendonça, C.S.; Nasser, M.A.; Andrade, M.C. Delphi technique in the validation process of the Primary Care Evaluation Questionnaire (QualiAB) for national application. Saude soc 2021, 30, e190505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Minor, B.L.; Elliott, V.; Fernandez, M.; O’Neal, L.; McLeod, L.; Delacqua, G.; Delacqua, F.; Kirby, J.; et al. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J. Biomed. Inform. 2019, 95, 103208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Thielke, R.; Payne, J.; Gonzalez, N.; Conde, J.G. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Inform. 2009, 42, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, K.; Li, X.; Yang, D.; Chan, S.C.; Zhou, J.; Wan, E.Y.; Chui, C.S.; Lai, F.T.; Wong, C.K.; Chan, E.W.; et al. Risk of autoimmune diseases following COVID-19 and the potential protective effect from vaccination: a population-based cohort study. EClinicalMedicine 2023, 63, 102154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazil. Brazilian Observatory of Public Policies with the Homeless Population. Faculty of Law. Federal University of Minas Gerais. 2022. https://obpoprua.direito.ufmg.br/ (accessed April 7, 2024).

- Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics. Estimates of the resident population for municipalities and federation units. 2023.https://www.ibge.gov.br/estatisticas/sociais/populacao/9103-estimativas-de- populacao.html (accessed April 7, 2024).

- Brasil. Ministério da Saúde Coronavírus Brasil. Brasília. 2021. Available online: https://covid.saude.gov.br (accessed on 12 October 2020).

- Brazil. COVID-19 Vaccinometer. Ministry of Health. 2024. https://infoms.saude.gov.br/extensions/SEIDIGI_DEMAS_Vacina_C19/SEIDIGI_ DEMAS_Vacina_C19.html (accessed April 7, 2024).

- Zuur, A.F.; Ieno, E.N.; Elphick, C.S. A protocol for data exploration to avoid common statistical problems. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2010, 1, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, V.; Dasgupta, S.; Weller, D.L.; Kriss, J.L.; Cadwell, B.L.; Rose, C.; Pingali, C.; Musial, T.; Sharpe, J.D.; Flores, S.A.; et al. Patterns in COVID-19 Vaccination Coverage, by Social Vulnerability and Urbanicity — United States, December 14, 2020–May 1, 2021. MMWR. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2021, 70, 818–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claude, K.M.; Serge, M.S.; Alexis, K.K.; Hawkes, M.T. Prevention of COVID-19 in Internally Displaced Persons Camps in War-Torn North Kivu, Democratic Republic of the Congo: A Mixed-Methods Study. Glob. Heal. Sci. Pr. 2020, 8, 638–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacDonald, N.E.; Eskola, J.; Liang, X.; Chaudhuri, M.; Dube, E.; Gellin, B.; Goldstein, S.; Larson, H.; Manzo, M.L.; Reingold, A.; et al. Vaccine Hesitancy: Definition, Scope and Determinants. Vaccine 2015, 33, 4161–4164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhn, R.; Henwood, B.; Lawton, A.; Kleva, M.; Murali, K.; King, C.; Gelberg, L. COVID-19 vaccine access and attitudes among people experiencing homelessness from pilot mobile phone survey in Los Angeles, CA. PLOS ONE 2021, 16, e0255246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dula, J.; Mulhanga, A.; Nhanombe, A.; Cumbi, L.; Júnior, A.; Gwatsvaira, J.; Fodjo, J.N.S.; Villela, E.F.d.M.; Chicumbe, S.; Colebunders, R. COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptability and Its Determinants in Mozambique: An Online Survey. Vaccines 2021, 9, 828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harapan, H.; Wagner, A.L.; Yufika, A.; Winardi, W.; Anwar, S.; Gan, A.K.; Setiawan, A.M.; Rajamoorthy, Y.; Sofyan, H.; Mudatsir, M. Acceptance of a COVID-19 Vaccine in Southeast Asia: A Cross-Sectional Study in Indonesia. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiar A, Meireles P, Rebelo R, Barros H. COVID-19 and homelessness: No one can be left behind 2020.

- Wood, S.P. Vaccination Programs among Urban Homeless Populations: A Literature Review. J. Vaccines Vaccin. 2012, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hino, P.; Santos, J.d.O.; Rosa, A.d.S. People living on the street from the health point of view. Rev. Bras. de Enferm. 2018, 71, 684–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.; Hu, Z.; Zhao, Q.; Alias, H.; Danaee, M.; Wong, L.P. Understanding COVID-19 vaccine demand and hesitancy: A nationwide online survey in China. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2020, 14, e0008961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corrêa SMC, Vasconcelos PF de, Passos JS dos, Marques VG, Tanajura NPM, Nascimento DR do, et al. The possible causes of non-adherence to immunization in Brazil: a literature review | Revista Eletrônica Acervo Saúde 2021.

- Knight, K.R.; Duke, M.R.; Carey, C.A.; Pruss, G.; Garcia, C.M.; Lightfoot, M.; Imbert, E.; Kushel, M. COVID-19 Testing and Vaccine Acceptability Among Homeless-Experienced Adults: Qualitative Data from Two Samples. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2021, 37, 823–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brazil. Manual on health care for the homeless population. Ministry of Health. Health Care Secretariat. Department of Primary Care. DF: Brasília: Ministry of Health; 2012.

- Brazil. Manual on health care for the homeless population. Ministry of Health. Health Care Secretariat. Department of Primary Care. DF: Brasília: Ministry of Health; 2015.

- Mecenero AC. Homeless Population and Social Rights, 2022.

- Platt, L.; Rathod, S.D.; Cinardo, P.; Guise, A.; Hosseini, P.; Annand, P.; Surey, J.; Burrows, M. Prevention of COVID-19 among populations experiencing multiple social exclusions. J. Epidemiology Community Heal. 2021, 76, 107–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Frequency (n) |

% |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 961 | 69,0 |

| Female | 429 | 30,8 |

| Others | 2 | 0,2 |

| Race/Color | ||

| Black/Brown | 1097 | 78,8 |

| White | 295 | 21,2 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single, Divorced, Widowed | 1247 | 89,6 |

| Married/stable union | 145 | 10,4 |

| Occupation | ||

| Unemployed | 669 | 48,0 |

| Informal | 328 | 23,6 |

| Formal | 229 | 16,5 |

| Retired | 96 | 6.9 |

| Student | 70 | 5,0 |

| Education | ||

| Fundamental | 1060 | 76,1 |

| High School | 273 | 19,6 |

| Higher or more | 53 | 3,9 |

| No schooling | 6 | 0.4 |

| Income in minimum wage | ||

| Above 10 | 2 | 0,1 |

| From 1 to 5 | 648 | 46,6 |

| Variables | Frequency (n) |

% |

|---|---|---|

| Diagnosed with COVID-19 | ||

| Yes | 397 | 28,5 |

| No | 981 | 70,5 |

| I don't know | 14 | 1,0 |

|

Incomplete basic scheme against COVID-19 | ||

| Yes | 1165 | 83,7 |

| No | 227 | 16,3 |

|

Complete basic scheme against COVID- 19 | ||

| Yes | 869 | 62,4 |

| No | 523 | 37,6 |

|

Do you feel social pressure to take the COVID-19 vaccine? | ||

| Yes | 416 | 29,9 |

| No | 881 | 63,3 |

| I don't know | 95 | 6,8 |

|

Do you agree with mandatory vaccination against COVID-19? | ||

| Yes | 810 | 58,2 |

| No | 488 | 35,1 |

| I don't know | 94 | 6,8 |

| Trust in the effectiveness of vaccines | ||

| Yes | 975 | 70,0 |

| No | 325 | 23,3 |

| I don't know | 92 | 6,6 |

|

Trust in the federal government's actions on vaccines | ||

| Trust | 959 | 68,9 |

| Doesn't trust | 325 | 23,3 |

| I don't know | 108 | 7,8 |

|

Trusts the state government's actions on vaccines | ||

| Trust | 1018 | 73,1 |

| Doesn't trust | 267 | 19,2 |

| I don't know | 107 | 7,7 |

|

Trusts the actions of the municipal government on vaccines | ||

| Trust | 1014 | 72,8 |

| Doesn't trust | 271 | 19,5 |

| I don't know | 107 | 7,7 |

| Variables | Frequency (n) | % |

|---|---|---|

| Sources of official information | ||

| No | 1320 | 94,8 |

| Yes | 72 | 5,2 |

| Unofficial sources of information | ||

| No | 1305 | 93,8 |

| Yes | 87 | 6,3 |

| Health professionals | ||

| No | 1107 | 79,5 |

| Yes | 285 | 20,5 |

| Social media | ||

| No | 1234 | 88,6 |

| Yes | 158 | 11,4 |

|

NGOs, street clinics, community leaders |

||

| No | 1207 | 86,7 |

| Yes | 185 | 13,3 |

| Official press | ||

| No | 187 | 13,4 |

| Yes | 1205 | 86,6 |

| Searched for information | ||

| No | 1215 | 87,3 |

| Yes | 177 | 12,7 |

| Variable | Coefficient | Odds Ratio (95%CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender Male | -0,34 | 0,70 [0,46 - 1,06] | 0,09 |

| Received any kind of government aid | 0,45 | 1,58 [1,09 - 2,30] | 0,01* |

| Uses SUS | 0,45 | 1,58 [0,99 - 2,50] | 0,06 |

| Visited by ACS | 11,61 | 3,19 [1,95 - 5,36] | <0,01* |

| UBS in the neighborhood | -0,49 | 0,60 [0,40 - 0,91] | 0,01* |

| There was COVID-19 | 17,53 | 5,77 [3,17 - 11,15] | <0,01* |

| Do you agree with mandatory vaccinations? |

13,27 | 3,76 [2,48 - 5,76] | <0,01* |

| Believes in the effectiveness of vaccines |

13,68 | 3,92 [2,63 - 5,89] | <0,01* |

| Searched for unofficial information to stay informed about COVID-19 |

-32,17 | 0,04 [0,01 - 0,25] | <0,01* |

| He sought information from NGOs, street clinics, community leaders to keep himself informed about COVID-19 | 0,64 | 1,91 [1,01 - 3,88] | 0,04* |

| You have sought information from the official press to stay informed about COVID-19 |

-30,89 | 0,04 [0,01 - 0,23] | <0,01* |

| Did not seek information to stay informed about COVID-19 |

-0,97 | 0,37 [0,24 - 0,59] | <0,01* |

| Potential level of trust in the federal government over vaccines |

0,45 | 1,57 [1,06 - 2,31] | 0,02* |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).