1. Introduction

The rainfall within the watershed generates runoff, which flows towards the lowland plains under the influence of gravity, eventually collecting into lakes. Dramatic changes in terrain during this process lead to a reduction in flow velocity, causing sediment carried by the water to deposit at the entrance of the lake. This deposition promotes the formation of alluvial plains. Over time, a complex network of waterways gradually develops around the lake. As lake water further flows into downstream rivers, the lake becomes influenced by both internal and external rivers, giving rise to more complex hydrological phenomena. Lakes of this type are referred to as “connected lakes” in our study. It’s worth noting that due to the unique geographical characteristics of these lakes and their surrounding areas, they often become prone to frequent and severe flooding during the rainy season. For instance, Lake Malawi in Africa [

1], Lake Victoria in Kenya [

2], and China’s Poyang Lake and Dongting Lake [

3] have all suffered from severe floods in the past few decades, causing tremendous disasters to the coastal residents.

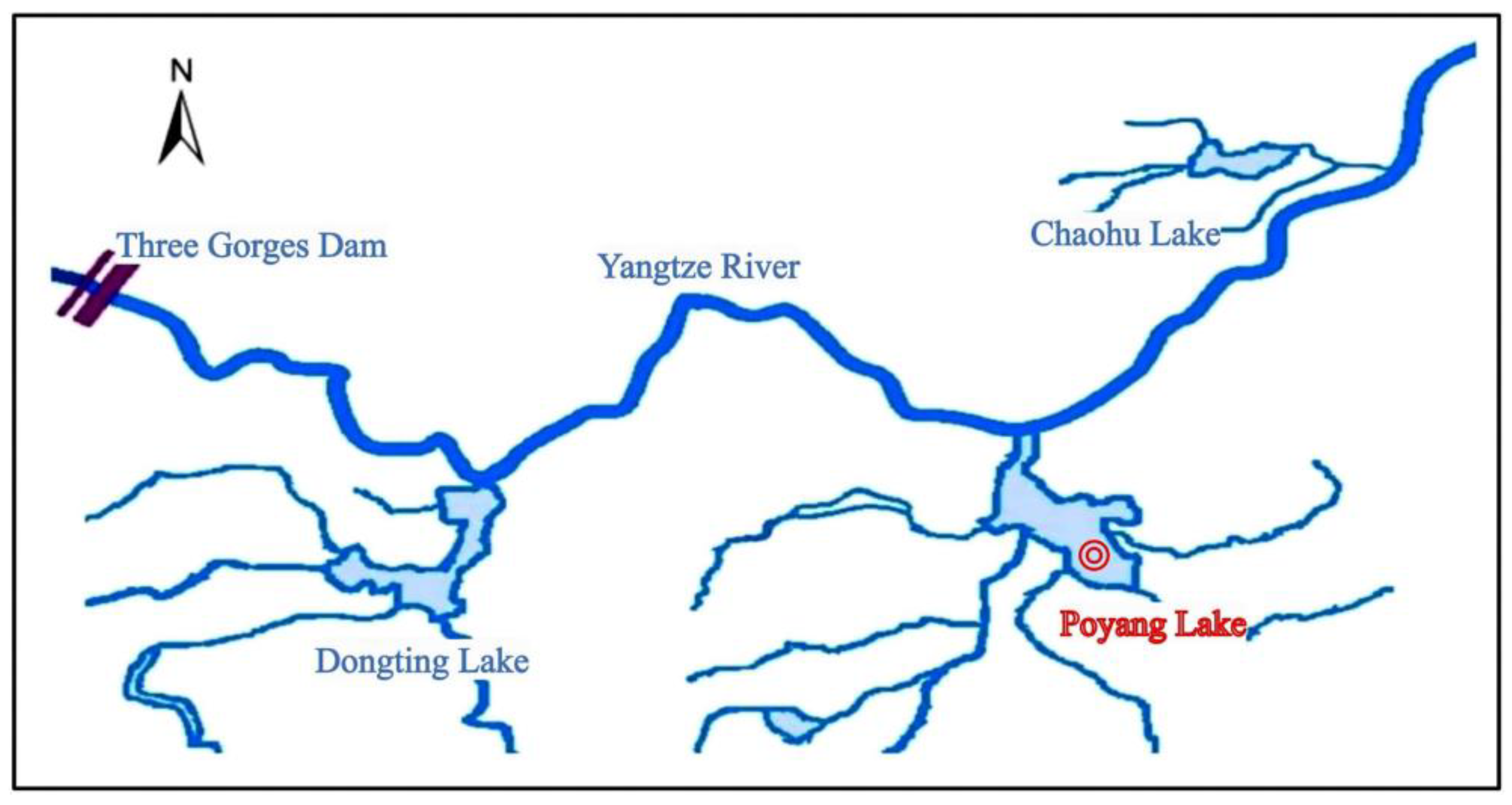

Figure 1.

The river-connected lakes distributed in the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River.

Figure 1.

The river-connected lakes distributed in the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River.

Currently, 23% of the global population is under the threat of flooding, with China leading the list with 395 million people at risk [

4]. The Poyang Lake region is one of the hardest-hit areas. As the largest connected lake in the Yangtze River basin, Poyang Lake’s flood formation and development are jointly influenced by the inflow from five major rivers within the watershed (Gan River, Fu River, Xin River, Rao River, and Xiu River, collectively known as the “Five Rivers”) and floods from the Yangtze River. Under normal circumstances, the main flood season of the Poyang Lake watershed and the middle reach of the Yangtze River are staggered by 1 to 2 months to avoid triggering major floods. However, when floods from the river and the lake converge, they create a strong top-supporting effect, making it difficult for the lake to discharge, and keeping Poyang Lake at a high water level for an extended period and leading to flooding disasters. The flat terrain, vast water surface, and 2,946 kilometers of main dikes around Poyang Lake pose significant challenges to flood defense efforts in the region. Additionally, the fertile alluvial plains surrounding Poyang Lake are important grain-producing areas, with cultivated land accounting for 39% of the region’s area. The region also includes economically developed and densely populated cities such as Nanchang and Jiujiang. Despite occupying only 30% of the province’s area, the region is home to 50% of the population and generates over 60% of the province’s economic output. These advantages bring prosperity but also exacerbate flood risks and defense pressures. For example, the 1998 Poyang Lake flood affected 20.09 million people and damaged 15,840 square kilometers of crops in Jiangxi Province [

5].

For a long time, many scholars have been committed to studying the flood characteristics and risk management of the Poyang Lake region to reduce flood losses in the area. In terms of flood control and emergency response, numerous studies have deeply analyzed the application strategies and flood diversion effects of flood diversion areas and semi-restoration polder areas around the lake, proposing corresponding optimal scheduling measures [

6,

7,

8]. Meanwhile, to more accurately simulate and predict floods in Poyang Lake, experts have adopted various technical means, including water level-storage capacity curves, water balance methods, hydrological models, hydrodynamic models, and artificial neural network models [

9,

10,

11]. Due to the intricate river-lake-river interaction phenomena in Poyang Lake, its flood characteristics and influencing factors have become hot research topics [

8,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16].

Poyang Lake is mainly influenced by the runoff of the “Five Rivers,” causing significant periodic fluctuations in lake water levels [

13]. During the flood season of the Yangtze River, the top-supporting effect of high water levels on the lake area is a crucial factor causing rapid water level rise in Poyang Lake [

14]. Additionally, Poyang Lake plays a significant role in regulating and storing inland river floods. However, its regulation and storage capacity significantly decrease when floods from the Yangtze River and Poyang Lake converge [

8,

15]. Therefore, rational use of existing water conservancy projects and optimizing strategies for flood encounters at the lake’s inlet control stations have become crucial methods to mitigate the severity of floods in Poyang Lake [

16]. Overall, the characteristics of Poyang Lake floods are a complex phenomenon shaped by river input within the watershed, the influence of the Yangtze River’s main stream, and human engineering regulation. Effective management and flood control require comprehensive consideration of multiple factors.

Thanks to the continuous efforts of scholars and government departments, significant achievements have been made in flood control in Poyang Lake. For example, during the historically largest flood in Poyang Lake in 2020, the number of affected people and the area of affected crops in Jiangxi Province decreased by 66% and 53%, respectively, compared to 1998 [

5]. However, the flood problem in Poyang Lake remains complex and influenced by various factors, requiring further exploration to achieve precise prediction. Especially for plain lakes affected by upstream and downstream river networks, a deep understanding of the spatiotemporal characteristics of flood propagation and evaluation of the impact on the lake’s hydrological environment during this process is the foundation for accurate flood prediction and risk management. This is also the phenomenon and law that this article aims to reveal by studying the spatiotemporal characteristics of flood propagation in Poyang Lake, hoping to provide beneficial insights for regions facing similar flood threats globally.

2. Data and Methods

2.1. Study Area

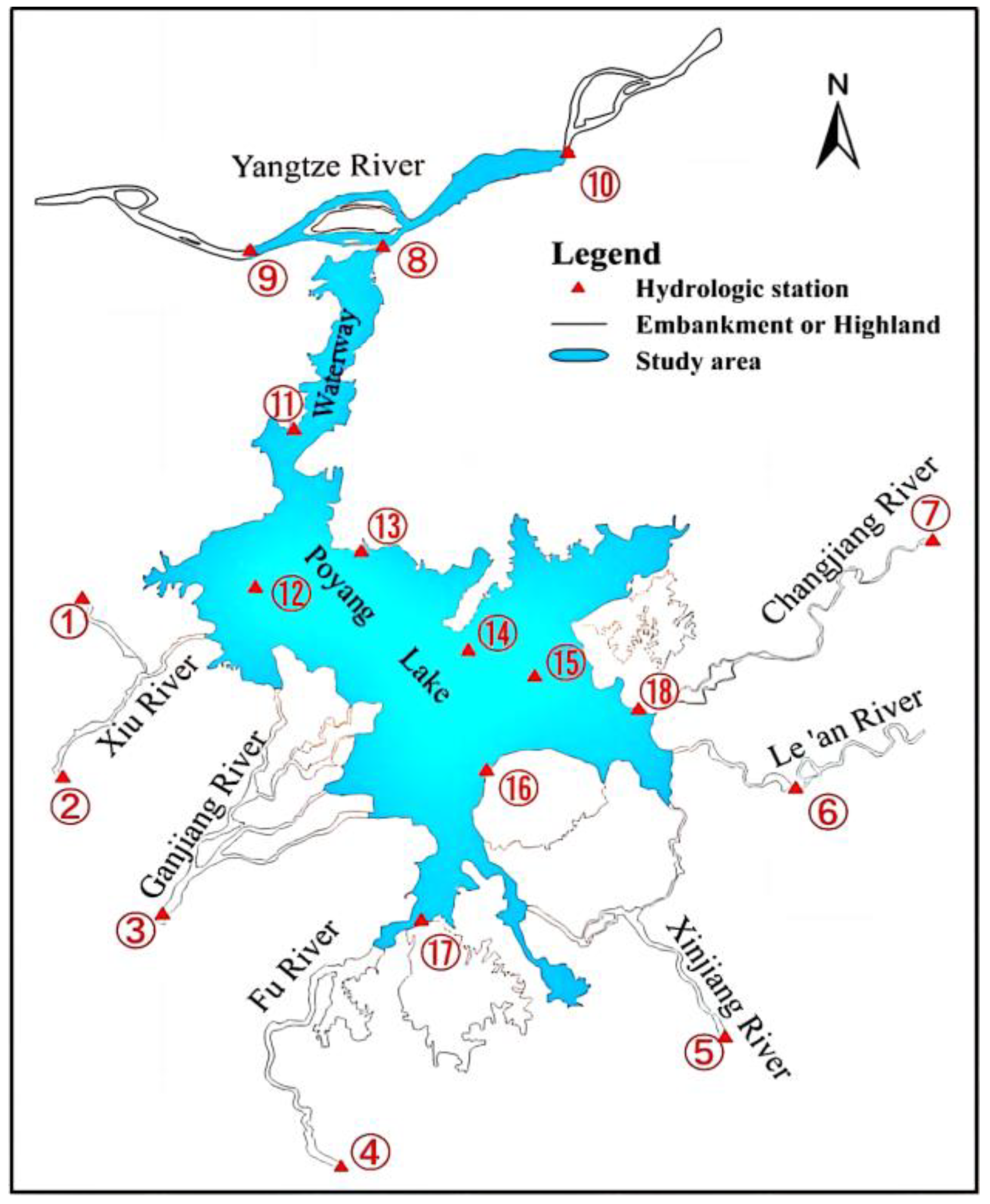

Poyang Lake is located in Jiangxi Province, on the south bank of the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River. Its basin converges five major rivers, namely, the Gan River, Fu River, Xin River, Rao River, and Xiu River (collectively referred to as the “Five Rivers”). These rivers flow from south to north and eventually merge into the Yangtze River at Hukou [

17,

18]. The scope of this study encompasses Poyang Lake and the connected section of the Yangtze River mainstream in Jiangxi (see

Figure 2), covering a total area of 3,606.6 square kilometers. Within this range, Poyang Lake specifically refers to the vast water area from the estuaries of the “Five Rivers” to Hukou, with an area of 3,219.1 square kilometers determined through comprehensive analysis of remote sensing images of flood inundation over the years and surrounding embankment data. The Yangtze River mainstream section refers to the main river segment between Jiujiang and Pengze, covering an area of 387.5 square kilometers.

2.2. Data and Analysis

This study adopts several key data authoritatively provided by the Jiangxi Provincial Institute of Water Sciences, including detailed hydrological data from hydrological stations over the years, precise embankment information for Poyang Lake, high-resolution digital topographic maps of Poyang Lake, and comprehensive records of flooded areas over the years. Additionally, the core data on natural resources and socio-economics cited in the text originate from two important planning documents: “Ecological Economic Zone Planning of Poyang Lake” and “The Rise of Poyang Lake Ecological Economic Zone Construction to National Strategy,” ensuring the authority and accuracy of the research data.

2.2.1. Hydrological Data

As the largest freshwater lake in China, changes in the hydrological characteristics of Poyang Lake are of great significance to the ecological environment and regional development. To monitor these changes in real-time, multiple hydrological monitoring stations have been carefully arranged in the Poyang Lake basin.

Table 1 and

Figure 2 detail the information of 18 key hydrological stations in the study area, which play an indispensable role in data collection and monitoring.

Among these stations, Xingzi Hydrological Station ⑪ stands out due to its unique geographical location. It is situated on a key passage after the convergence of the Five Rivers in the lake area and is located on the left bank of the waterway from Poyang Lake to the Yangtze River, making it a landmark hydrological station of Poyang Lake. This location enables Xingzi Station to accurately capture important changes in the lake’s hydrological characteristics.

Meanwhile, Hukou Hydrological Station ⑧ and Jiujiang Hydrological Station ⑨ also play crucial roles. Hukou Hydrological Station, located at the foot of Shizhong Mountain in Hukou County, Jiujiang City, serves as the control station for the Poyang Lake basin’s entrance into the Yangtze River. Jiujiang Hydrological Station, located on the Yangtze River mainstream, is a key hydrological station connecting the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River. The water level and flow rate data from these two stations during the flood season are extremely valuable for studying the complex relationship between Poyang Lake and the Yangtze River.

In addition, the data on the inflow of the “Five Rivers” into the lake in this study originate from the hydrological data collected by the corresponding control stations ①~⑦. These data provide accurate information about river flow rates. Meanwhile, monitoring data from other stations in the lake area, especially water level data, is widely used in the calibration of hydrodynamic models to ensure their accuracy and reliability.

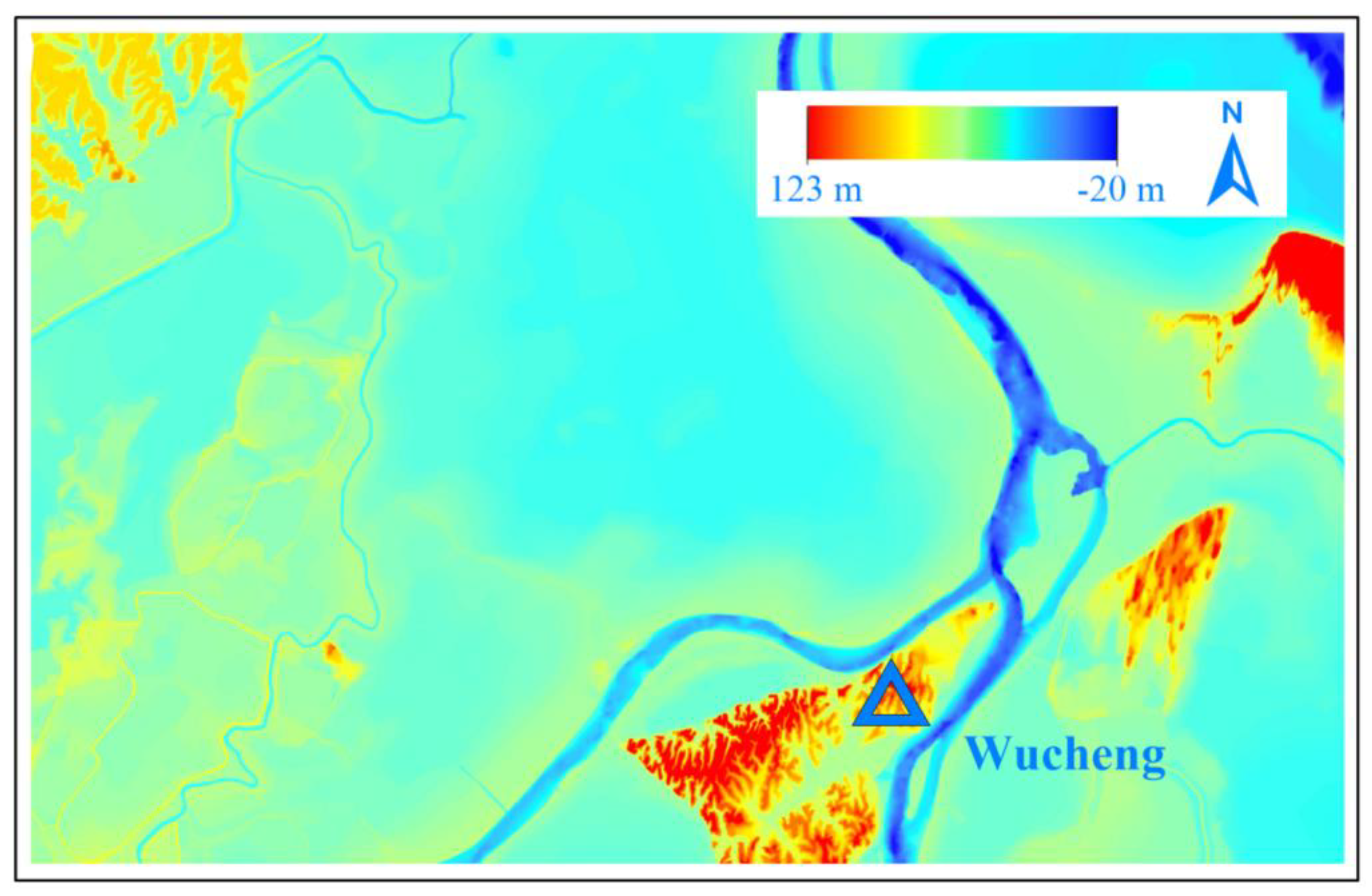

2.2.2. Topographic Data

This study adopts high-precision topographic data of Poyang Lake and the Yangtze River mainstream provided by the Jiangxi Provincial Institute of Water Sciences. Specifically, the topographic data of Poyang Lake is based on a 10m*10m resolution digital terrain model collected in 2011, while the topographic data of the Yangtze River mainstream is derived from 1:1000 high-resolution scattered elevation data obtained in 2017. It’s worth emphasizing that comprehensively measuring the lake basin topography of Poyang Lake is an extremely challenging task due to its vast area. Therefore, the topographic data adopted in this study is the latest available information. Actually, only when significant erosion and deposition changes occur in the lake basin will a complete re-measurement be considered. Currently, uninterrupted terrain monitoring of key sections of the lake is still ongoing.

Recent studies have shown that the erosion of Poyang Lake is mainly concentrated in the tail channels of the lake and the northern lake area’s waterway to the Yangtze River, manifesting as a phenomenon of deep channel incision [

19,

20,

21]. This incision phenomenon has a relatively small impact on wide and shallow cross-sections. Meanwhile, the bedrock of Shizhong Mountain at the entrance of Poyang Lake into the Yangtze River possesses excellent erosion resistance, maintaining relative stability in recent years [

22]. Furthermore, with the gradual strengthening and improvement of Poyang Lake’s protection measures, the direct impact of human activities on the lake basin topography has been significantly reduced [

23]. According to the latest research results on erosion and deposition evolution, the main lake area of Poyang Lake has basically maintained a balance between erosion and deposition, with relatively little impact on the lake basin topography [

24]. In summary, using the 2011 topographic data of Poyang Lake for recent flood process simulation in this study fully meets the accuracy requirements.

Figure 3.

Digital Terrain of the Downstream Local Area of Wucheng Hydrological Station ⑫ in Poyang Lake.

Figure 3.

Digital Terrain of the Downstream Local Area of Wucheng Hydrological Station ⑫ in Poyang Lake.

2.2.3. Tributaries Diversion Ratios

As the river winds its way into the Poyang Lake delta region, its many tributaries spread like vines, forming a complex network of waterways. This unique topographical feature not only endows Poyang Lake with rich ecological value but also poses unprecedented technical challenges for flood model construction. Especially in relatively narrow and steep areas, floods propagate much faster in the river channels than on the open lake area, increasing the complexity and difficulty of simulation.

To balance the accuracy and efficiency of the model, this study appropriately simplifies the simulation area. Specifically, we move the model’s entries to the estuaries of various tributaries. The adjusted model entries will allocate the inflow of upstream hydrological stations based on actual measured diversion ratio data to ensure the accuracy and validity of the simulation.

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. Implementing a Special Open Boundary Condition

When two rivers converge, their flows generate a top-supporting effect in the confluence zone, and the strength of this effect directly affects the degree of water level rise. This top-supporting phenomenon is particularly notable during the confluence of floods from Poyang Lake into the Yangtze River. Especially when a massive flow exceeding 80,000 m³/s surges into a river channel less than 2 km wide, the intense top-supporting effect and the resulting extremely high water level rise are incredible. This was one of the main reasons for the historic floods encountered by Poyang Lake in 2020. Records show that on July 11 of that year, the combined flow at Hukou and Jiujiang stations reached a staggering 85,900 m³/s. Furthermore, this interaction between the lake and the river is not limited to the confluence zone, with its influence extending up to 200 km downstream [

25]. As a result, in downstream areas close to such confluence zones, the water level is directly affected by the top-supporting interaction, exhibiting an irregular and uncertain “loop” phenomenon in relation to the flow rate [

26].

Although this hydrological phenomenon is common in estuarine areas, hydrodynamic models face methodological limitations when dealing with such open boundary conditions. Traditional methods, such as presetting water levels or defining “water level-flow rate relationships” based on semi-empirical formulas, are not applicable in these confluence zones. Because, in these regions, while the design flood flow rate may be known, the water level cannot be determined beforehand. Therefore, these methods cannot effectively simulate flood combination problems under the influence of top-supporting.

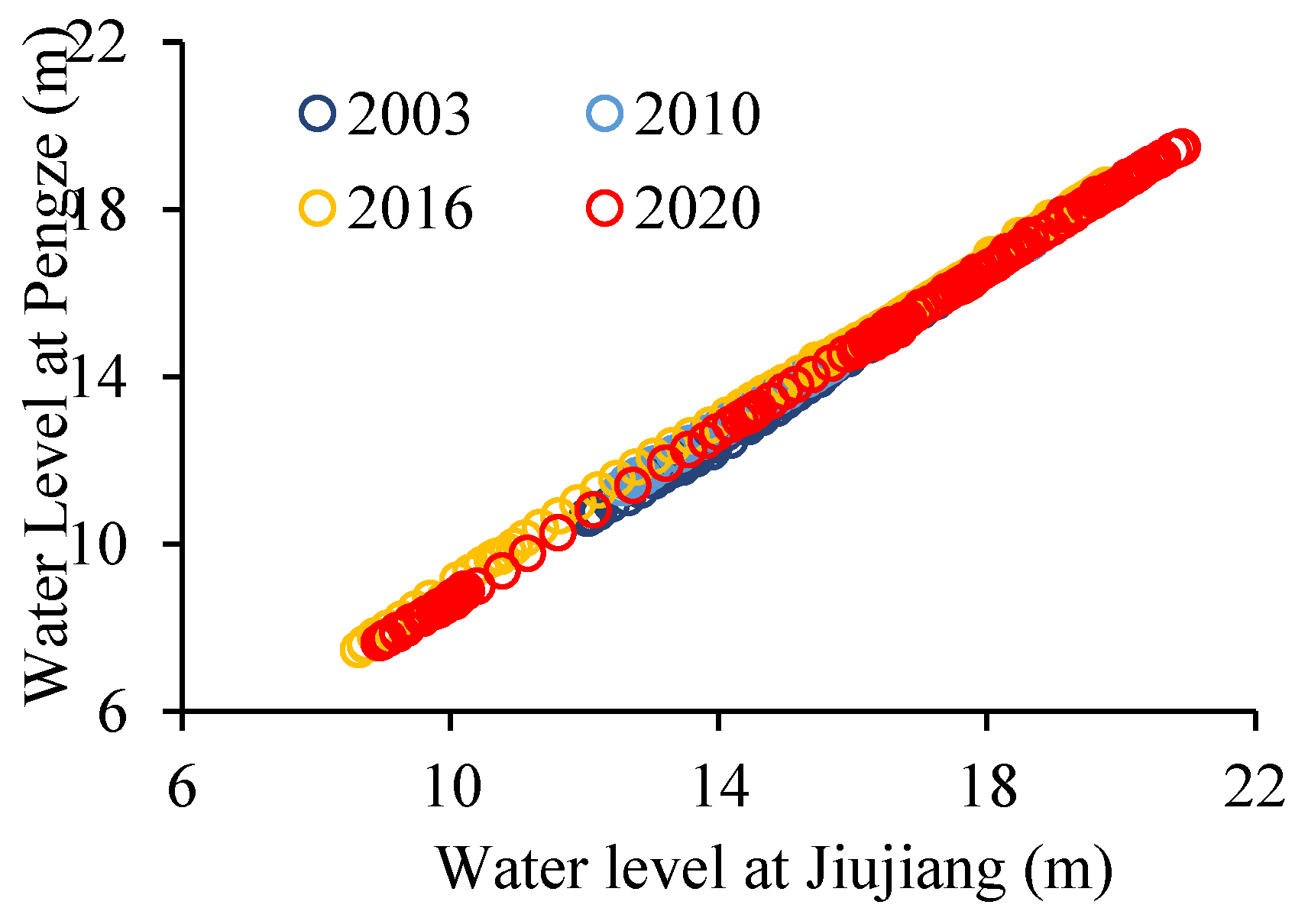

To overcome this limitation, this study innovatively introduces the concept of “water level correlation” [

20], commonly used in hydrology, into the hydrodynamic model. For large deep rivers with gentle slopes, the wave speed of floods is significantly faster than the flow speed, resulting in a close correlation between upstream and downstream water levels (see

Figure 4). Based on this principle, using flood data from 2003 to 2020, we successfully fitted a water level relationship formula (1) between Jiujiang station and Pengze station. This formula serves as the lower boundary condition for the hydrodynamic model, enabling more effective simulation and prediction of flood behavior in rivers confluence zones.

In the formula, and represent the water level of Pengze station and Jiujiang station respectively.

2.3.2. Construction of the Hydrodynamic Flood Evolution Model

In this study, commercial software DHI MIKE was used to draw grids for different regions in the study area, such as deltas, deep troughs, and shoals. To ensure grid continuity and integrity, the self-developed grid editing software “Grid Manager 1.0” was further utilized for grid stitching operations. Considering the complex and changing terrain, the grid size was set in the range of 100~600m. The final constructed model contained 27,944 grids and a corresponding number of nodes.

To reasonably set the open boundary conditions of the model under the top-supporting effects, we specially developed the “Poyang FS 1.3” software using the FORTRAN language. This software not only adopts the classic finite volume method to efficiently solve the two-dimensional shallow water equations [

27] but also innovatively integrates the setting function of the “water level correlation” open boundary.

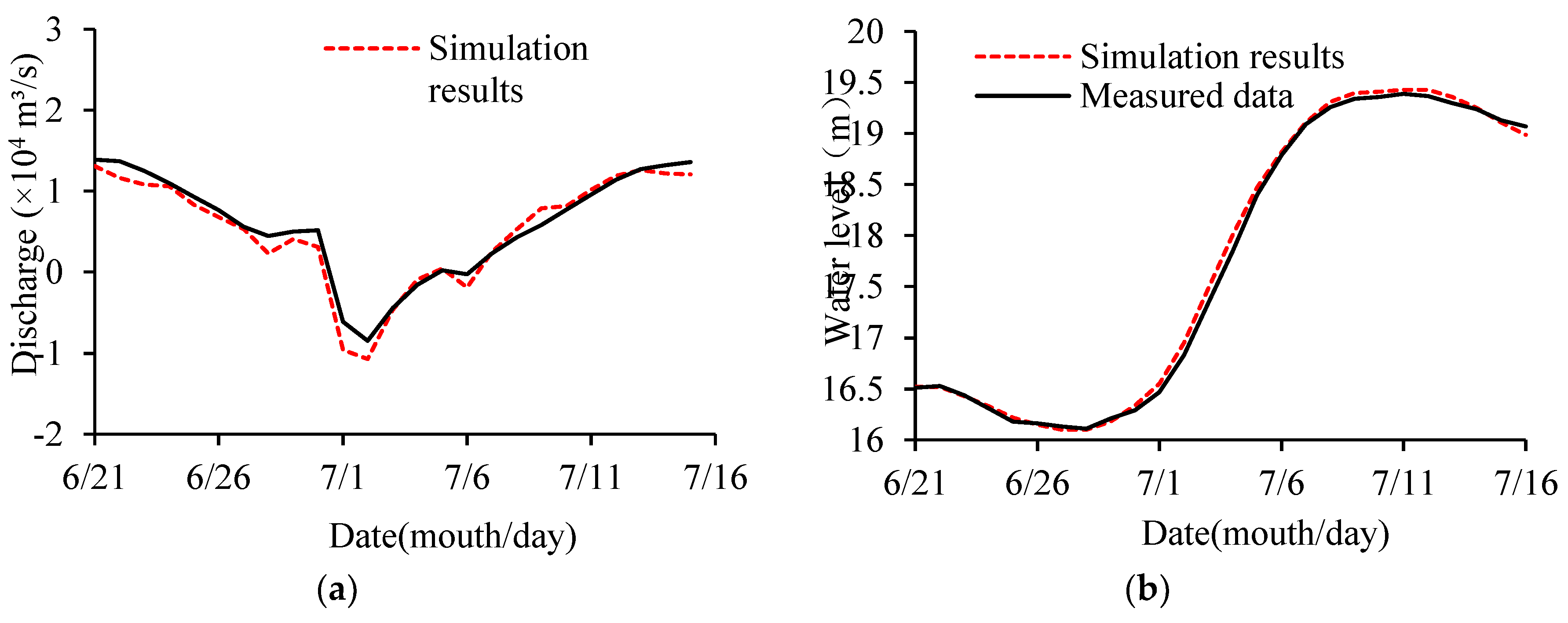

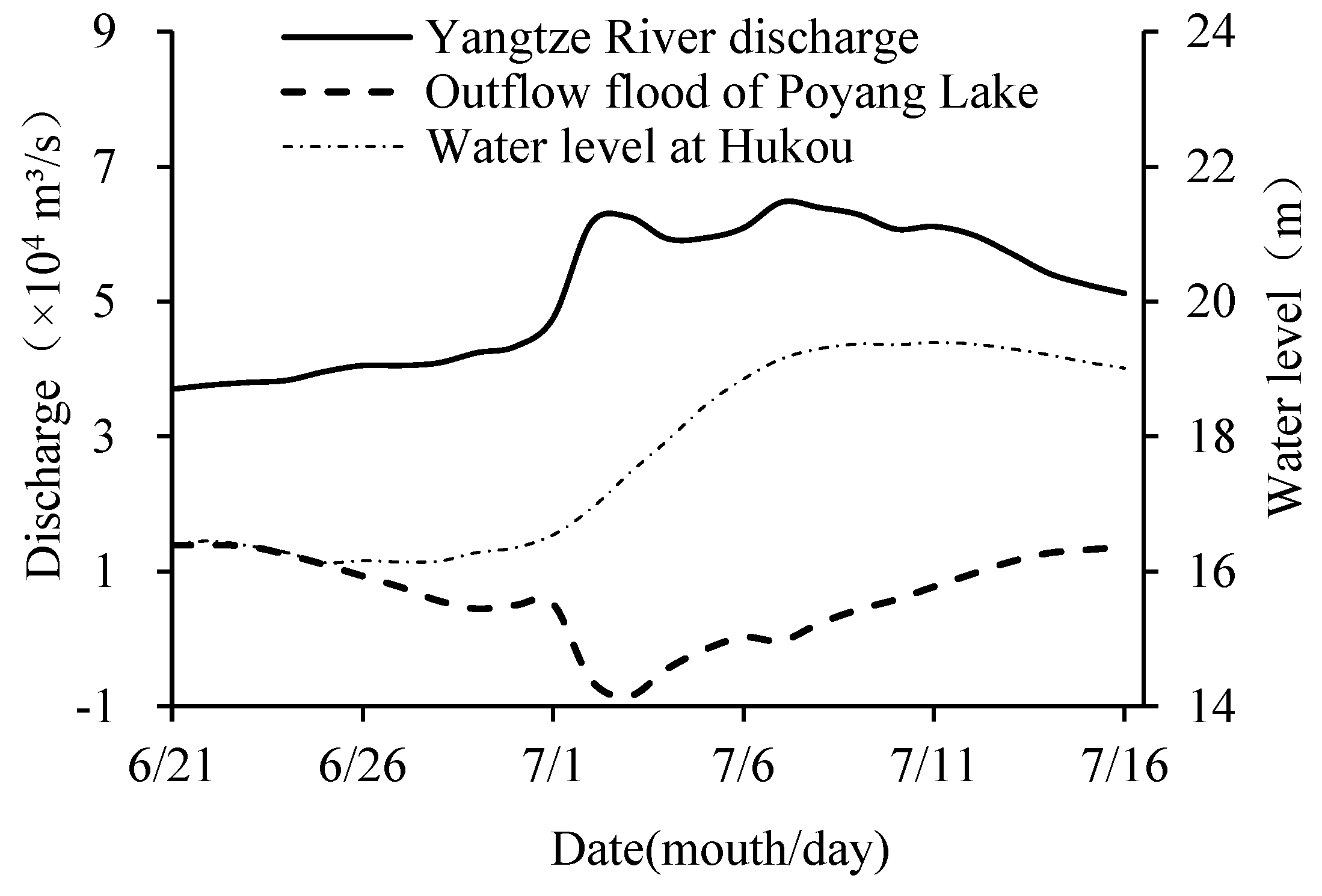

Given the top-supporting and emptying effects, and significant water level fluctuations in the lake system during the flood fluctuation process in Poyang Lake, we selected the flood event from June 21, 2016, to July 16, 2016, for simulation verification (see

Figure 4). The comparison between the simulation results and the measured data showed a high degree of consistency (see

Figure 5), with a correlation coefficient R2 of 0.998. Specifically, the average relative error of the simulated outflow from the lake was only 6.55%, and the root mean square error (RMSE) of the water level was as low as 0.04m. These simulation results fully comply with the industry specifications, which require a water level error of less than 0.1m and a flow error of less than 10%, demonstrating the excellent accuracy and reliability of the model.

2.3.3. Flood Combination

In large shallow lakes, the diversity of flood propagation paths can lead to significant differences in water level distribution. This is an important reason for establishing numerous hydrological stations in Poyang Lake. However, despite these observation points, it remains a challenge to accurately set a realistic and continuous initial water level distribution on the hydrodynamic model. To effectively study flood combination problems, we adopted an innovative approach: superimposing typical flood peak processes on a steady flow. Specifically, we selected a relatively balanced period of Yangtze River and the “Five Rivers”. Using the time-averaged flow rates of various inflow hydrological stations during this period as steady inflow conditions, and the “water level correlation” open boundary as the outflow condition, to simulate until the water flow reached a steady state. Subsequently, typical flood peak processes were superimposed on different river entrances to analyze the dynamic effects of flood propagation.

To implement this method, we first calculated the key parameters in a stable state using hydrological data from May 23 to June 2, 2016: the inflow rate into the lake was 11,150 m³/s, the Yangtze River flow rate was 35,500 m³/s, the outflow rate from the lake was 11,150 m³/s, and the water level at Hukou was 15.5m. Then, we selected the flow rate data from the Waizhou station from July 7 to 16, 2020, as a typical flood process and superimposed it on the inflow of the “Five Rivers” for simulation.

3. Results Analysis

3.1. Interaction between River and Lake Floods

The flood propagation process in plain-type river-connected lakes is profoundly influenced by the combined effects of the scale of inflow floods and the strength of river-lake top-supporting interaction. Through an in-depth analysis of historical hydrological data, this study aims to explore the mechanisms of river-lake top-supporting interactions and reveal the dominant factor in flood propagation.

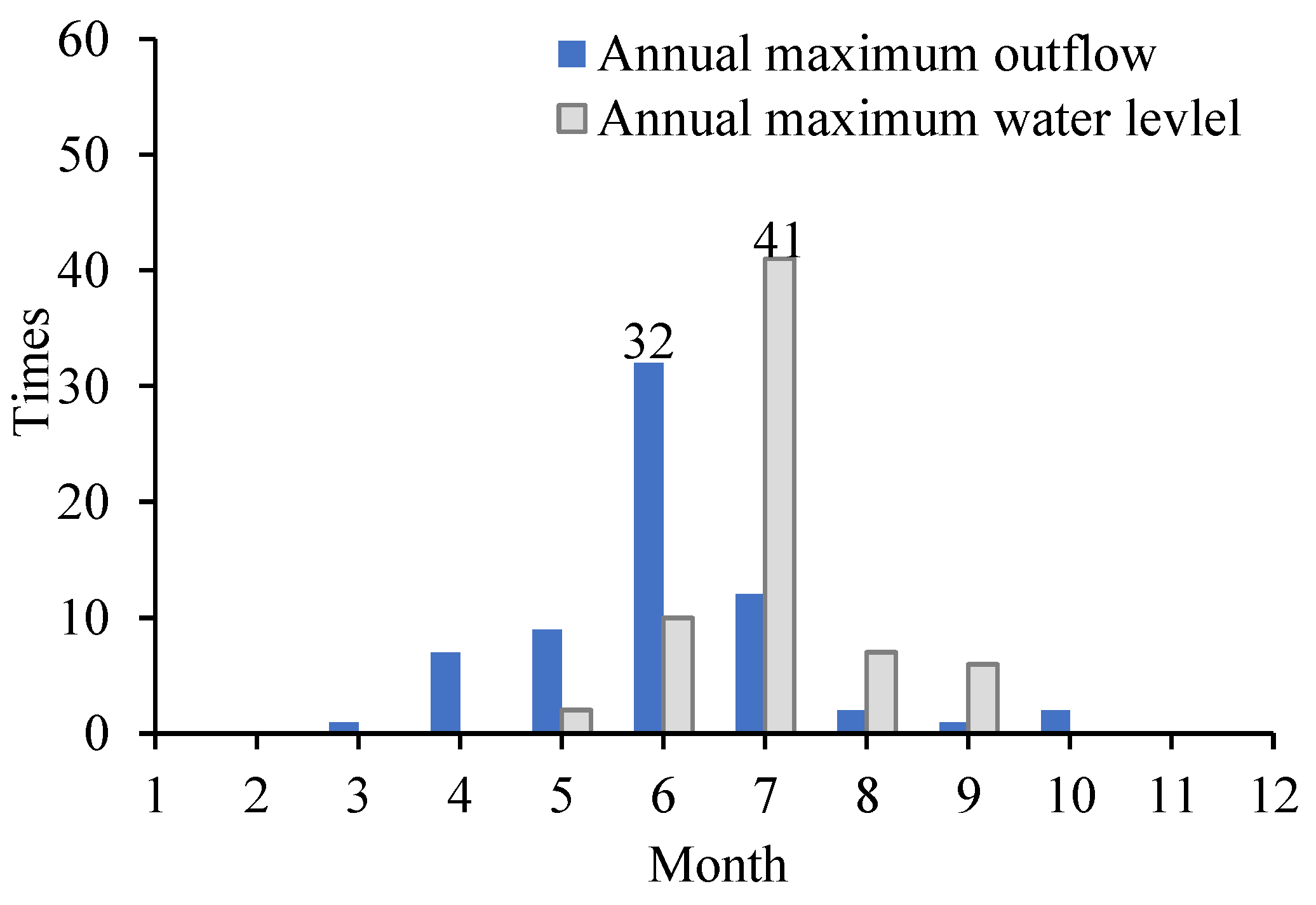

Figure 6 details the frequency of the annual maximum discharge and the highest water level at Hukou station from 1955 to 2020. Notably, the highest water level and maximum discharge in Poyang Lake do not occur simultaneously. Specifically, the maximum discharge mainly concentrates in June, coinciding with the main flood season of Poyang Lake, indicating that floods within the Poyang Lake basin play a dominant role in determining the annual maximum outflow from the lake. In contrast, the highest water level mainly occurs in July, aligning with the main flood season of the Yangtze River, suggesting that the Yangtze River floods predominantly influence the annual highest lake water level.

Figure 6.

Simulation results. (a) lake outflow. (b) lake water level.

Figure 6.

Simulation results. (a) lake outflow. (b) lake water level.

Figure 7.

Monthly occurrence of the annual maximum outflow and highest water level at Hukou station from 1955 to 2020.

Figure 7.

Monthly occurrence of the annual maximum outflow and highest water level at Hukou station from 1955 to 2020.

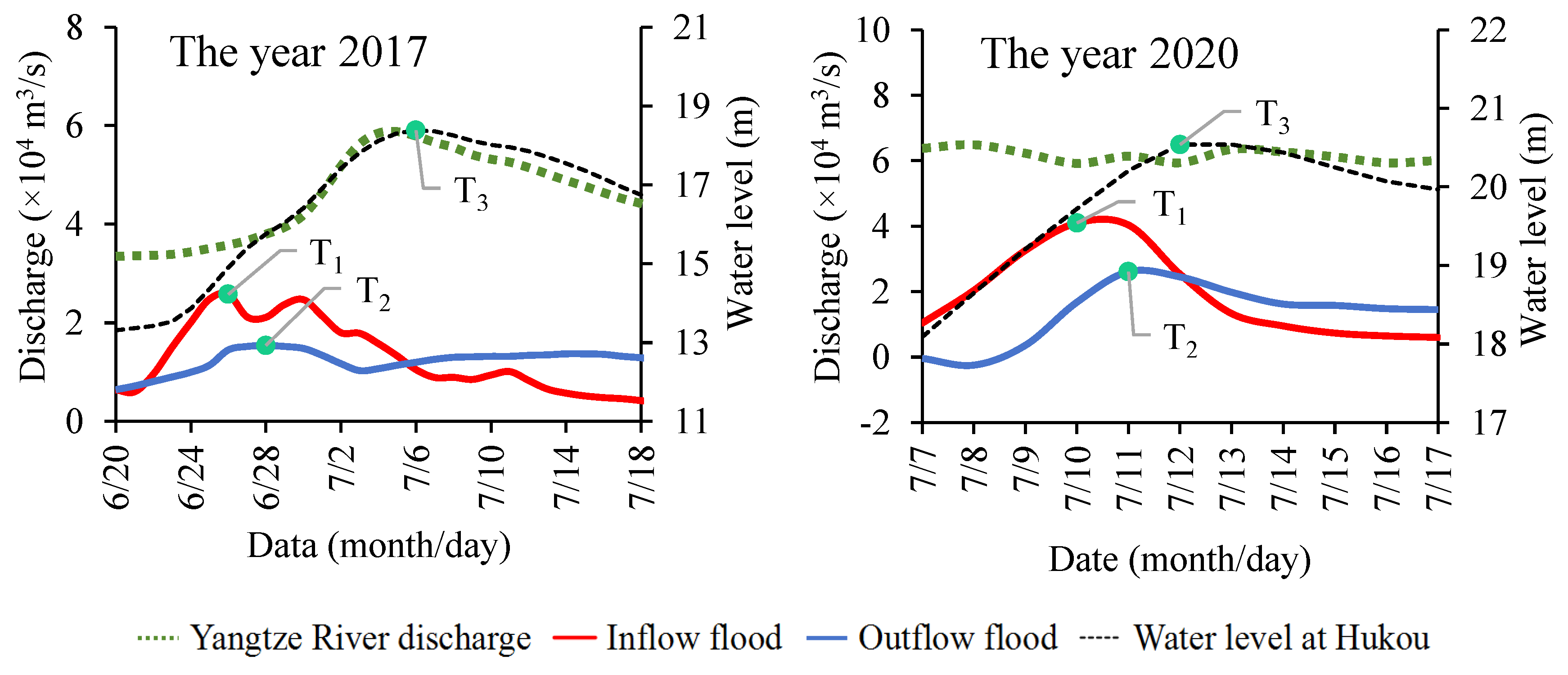

To further validate these observations, we conducted an in-depth analysis of historical major flood events from 1998 to 2020. The data in

Table 2 shows that the interval between the time of the incoming flood peak (T1) and the time of the peak outflow (T2) is less than or equal to 2 days. This suggests that the incoming flood peak can reach the lake outlet in a very short time, further supporting the view that floods within the Poyang Lake basin dominate the outflow. Additionally, the water volume stored in the lake enhances the outflow, potentially reducing the time it takes for the peak outflow to occur (T2-T1).

However, changes in the peak water level time exhibit more complex characteristics compared to the outflow. The interval between the time of the water level peak at Hukou (T3) and the time of the incoming flood peak (T1) can reach up to 10 days, primarily due to the influence of river-lake top-supporting interaction. This interaction prolongs the residence time of floods in the lake, resulting in a significant lag in the water level peak relative to the incoming flood peak.

Based on this, we discuss two scenarios of river-lake flood interaction:

Stable inflow from the Yangtze River: Taking July 2020 as an example (see

Figure 8), the Yangtze River flood was maintained within the range of 59,200 m³/ s to 64,900 m³/ s. In this case, the stable top-supporting effect of the Yangtze River on Poyang Lake makes making the floods of the “Five Rivers” become the main factor leading the lake flood process, including changes in the outflow and water level of the lake. Therefore, the time of peak outflow T2 in this flood is very close to the time of water level peak T3 (see

Table 2).

(2) Increasing inflow from the Yangtze River: Using July 2017 as an example (see

Figure 8), as the floods into the lake gradually weakened, the Yangtze River discharge continuously increased, causing the lake water level to rise. In this scenario, the Yangtze River floods become the key factor influencing changes in the lake water level. Therefore, the time of water level peak T3 lags significantly behind the time of peak outflow T2.

3.2. Changes in Lake Water Level under River-Lake Interaction

When the Yangtze River and the “Five Rivers” become the dominant factors influencing the flood process in Poyang Lake, the lake’s water level exhibits distinct variation characteristics. Specifically, the Yangtze River flood significantly raises the water level in the river-lake confluence zone through its strong top-supporting effect, thus effectively controlling the lake’s outlet. In this context, if the inflow from the “Five Rivers” decreases, the lake’s water level is mainly influenced by its outlet water level, resulting in a relatively flat lake surface resembling a reservoir. Conversely, an increase in inflow from the “Five Rivers” causes varying degrees of surface slope within the lake.

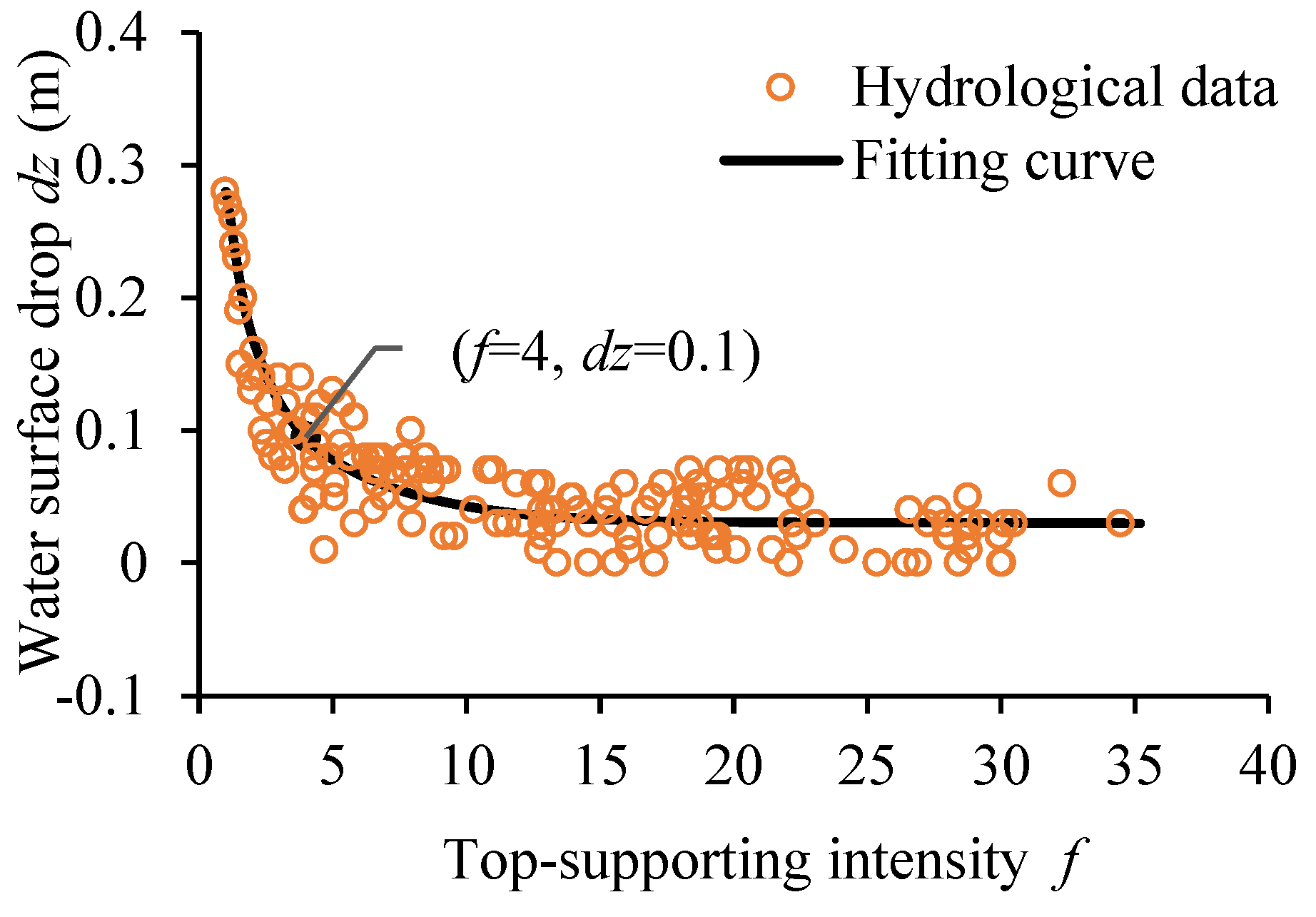

The Three Gorges Reservoir, located upstream of the confluence of the Yangtze River and Poyang Lake (see

Figure 1), was fully completed in 2009 and has effectively regulated the Yangtze River floods since then. To investigate the relationship between lake surface slope and river-lake top-supporting effects, we analyzed hydrological data during periods when Poyang Lake’s water level exceeded the flood warning level after 2010 (see

Figure 9). We used the water level difference between Tangyin and Xingzi stations (dz) to represent the lake surface slope and the ratio of Yangtze River discharge to the “Five Rivers” discharge (f) to measure the strength of the top-supporting effect. The results show that when the f value exceeds 4, indicating that the Yangtze River’s flood discharge is more than four times that of the “Five Rivers”, Poyang Lake’s surface remains relatively flat. Otherwise, the lake surface slope increases rapidly.

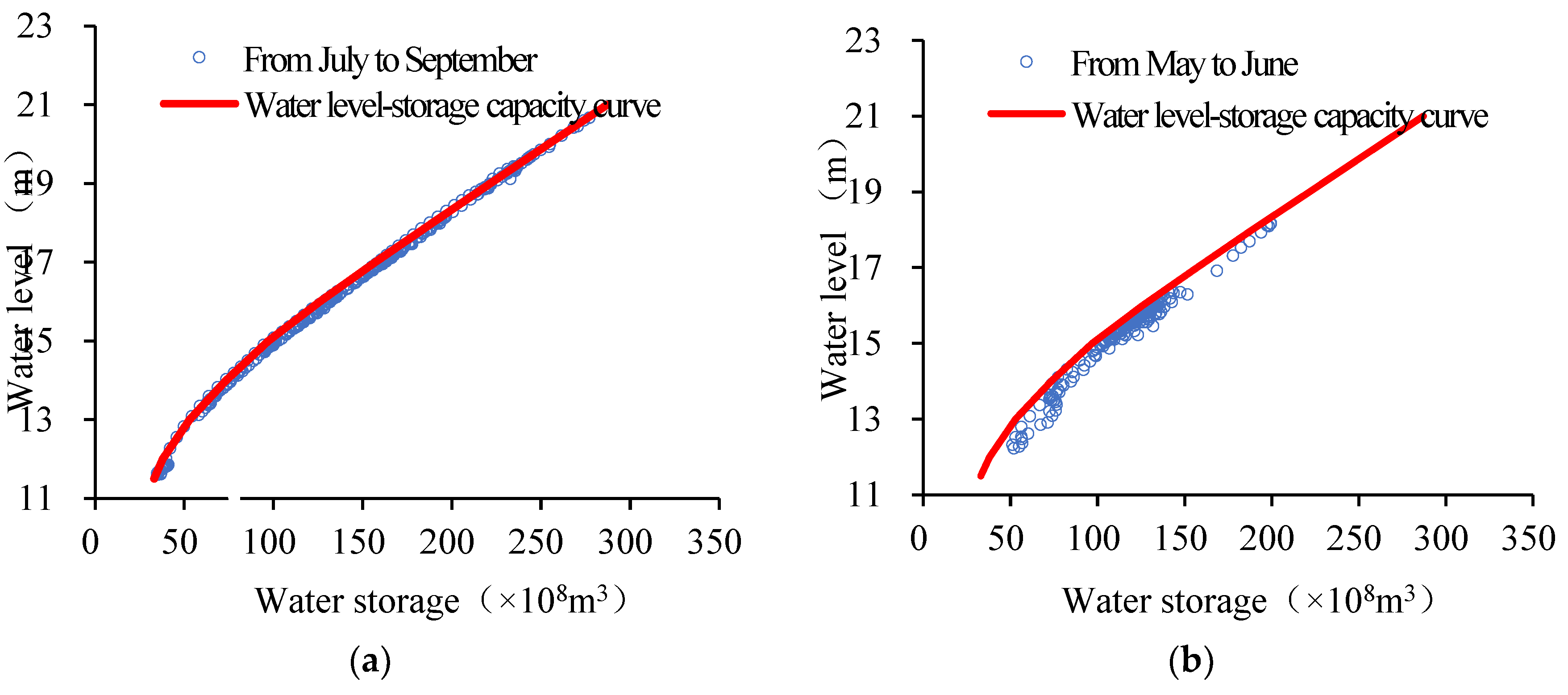

In flood analysis of Poyang Lake, researchers often use the relationship curve between the water level at Xingzi and the lake’s water storage capacity, known as the “water level-storage capacity curve” [

27]. However, this curve is typically based on the assumption of a flat lake surface. Therefore, once the lake surface slope increases, the lake’s actual storage capacity exceeds the calculated value based on the curve. The excess water storage capacity, defined as “dynamic storage capacity”, reflects the additional water volume due to surface slope changes. This data is crucial for accurate flood predictions in Poyang Lake and assessing the actual flood control benefits.

To further analyze the characteristics of “dynamic storage capacity” changes, we applied the same “water level-storage capacity curve” drawing method and obtained the research area’s curve (see

Figure 10). Additionally, we used the Poyang Lake flood evolution model to simulate the hydrological process from May to September in typical years (2010, 2012, 2016, and 2020). Based on the simulation results, we plotted a scatter plot showing the correlation between the water level at Xingzi and the lake’s water storage capacity (see

Figure 10). The simulation dataset for the Yangtze River’s flood season from July to September shows a clear band distribution, closely matching the “water level-storage capacity curve”. This emphasizes the critical role of the Xingzi water level in representing the “water level-storage capacity” relationship in Poyang Lake and verifies the accuracy of the correlation curve method during this period. However, the simulation data points for Poyang Lake from May to June are significantly lower than the correlation curve, indicating that the “dynamic storage capacity” affects the accuracy of the correlation curve method during this period. Further analysis of the simulation results reveals that the average “dynamic storage capacity” of the lake reaches 840 million cubic meters during the “Five Rivers” main flood season. Influenced by the strength of the river-lake top-supporting effect, the variation range of this “dynamic storage capacity” can be as high as 2.2 billion cubic meters.

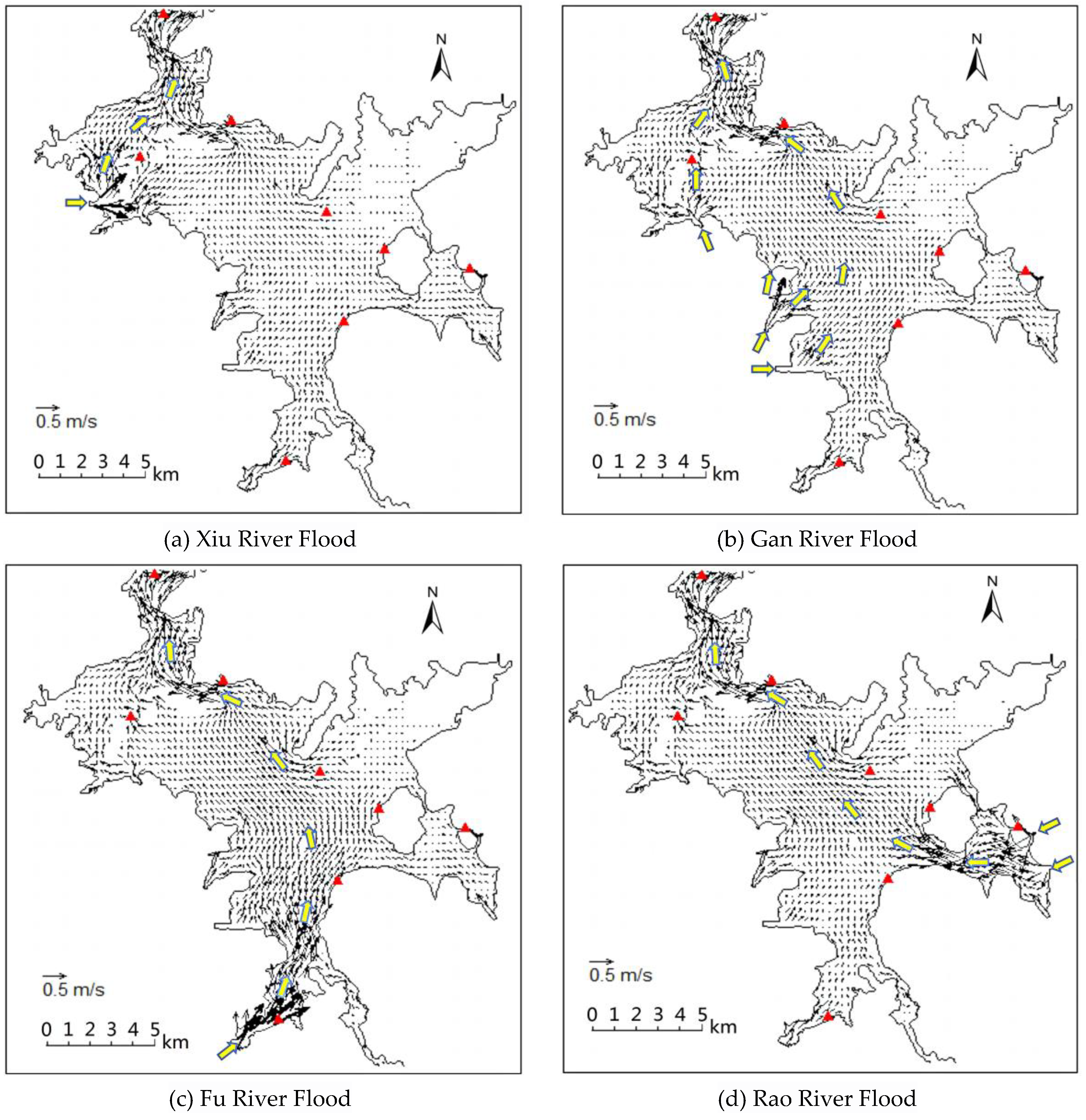

3.3. Propagation Characteristics of Floods from the “Five Rivers” into the Lake

In addition to the significant influence of the river-lake top-supporting effects on flood propagation in Poyang Lake, differences in flood propagation paths from different rivers into the lake cannot be ignored. These differences result in inconsistent flood peak propagation times and varying degrees of water level rise in different parts of the lake. To delve deeper into these impacts, typical flood processes were superimposed onto the five rivers and added into the Poyang Lake flood model for simulation.

Based on the simulation results, we plotted the flow field diagram of Poyang Lake at the 48 hours after the flood peak of the “Five Rivers” (see Figure 11). Based on the flow field information, this study connected areas with high and concentrated flow velocities, delineated the mainstream line, and measured its length as the flood propagation path. Among them, the Xiu River flood enters the lake, passes through Wucheng, and directly flows into the northern waterway leading to the lake outlet, with the shortest propagation distance and the fastest flood peak reaching the lake outlet, the time of water level peak taking only 50 hours (see

Table 3).

The Gan River diverges into four tributaries before entering Poyang Lake in Nanchang, namely the “Main Branch, North Branch, Middle Branch, and South Branch”. The South Branch converges with the waters of the Fu River and the West Branch of the Xin River at Kangshan, then flows northward through Tangyin and Duchang, and finally merges into the waterway leading to the lake outlet from the north side of Songmen Mountain. This propagation path is longer compared to the Xiu River and covers a wider area. The Main Branch exhibits similar characteristics to the Xiu River, while floods from the North and Middle Branches enter the lake along the delta region. Due to the combined effects of topographical inclination and lake water level support, these floods rapidly spread towards the central lake area. Consequently, during the propagation of Gan River floods to Hukou, their influence scope and distance exceed those of the Xiu River, resulting in a longer propagation time for the water level peak (see

Table 3).

The Fu River, due to its considerable distance from the lake outlet, requires its flood wave to pass through Sanyang and Kangshan before entering the main lake area of Poyang Lake and propagating to the waterway leading into the Yangtze River. Its influence and propagation range are more extensive compared to the Gan River. The Rao River converges into Poyang Lake via its two major tributaries, the Chang River and the Le’an River, and then flows from east to northwest through the main lake area, significantly impacting the eastern region of the lake, with a more prominent effect compared to other rivers. The Xin River enters Poyang Lake through two branches, east and west. The flood propagation paths of the two branches are similar to those of the Rao and Fu Rivers respectively. Despite differences in the flood propagation paths of these three rivers, the lake areas they involve are all quite extensive. Consequently, the regulation and storage of lakes have a particularly significant impact on the flooding of these rivers, resulting in a relatively more serious energy dissipation during the propagation of flood waves. As a result, the peak water levels of the Fu, Rao, and Xin Rivers all reach the lake outlet at 56 hours, lagging behind the Xiu and Gan Rivers (see

Table 3). This phenomenon reflects the significant impact of the complexity of the Poyang Lake hydrological system and the diversity of flood propagation paths from various rivers into the lake.

Figure 12.

Flow field diagram of the lake area at the 48th hour after the flood peak.

Figure 12.

Flow field diagram of the lake area at the 48th hour after the flood peak.

There is a clear proportional relationship between the time it takes for the peak discharge and water level of each river to reach the lake outlet and their respective distances to the outlet. Detailed data can be found in

Table 3 and

Table 4. It’s worth noting that the regulation and storage function of Poyang Lake influences the time of water level peak at the lake outlet, causing a certain lag relative to the time of peak outflow. Comprehensive data analysis reveals that the average propagation time for the peak discharge of the “Five Rivers” is 48.4 hours, while the peak water level propagates relatively slower, with an average time of 54 hours.

Differences in flood propagation paths can lead to varying degrees of water level rise at monitoring stations (see

Table 5). Specifically, the broader the flood wave’s propagation range, the higher water level rise at the stations it passes through. This is because as the propagation range expands, the kinetic energy of the flood wave gradually dissipates and converts into potential energy. Regarding the influence of various flood sources in the basin, the northern lake region experiences comparatively minimal effects. For instance, the maximum water level rise recorded at the Xingzi station varies by less than 0.02 meters. However, the central and southern lake areas are more significantly impacted, especially by floods from the Fu River, which surpass the influence of the Xiu River and Gan River. Taking the Tangyin and Kangshan stations as examples, floods from different sources cause maximum water level rise variations of up to 0.06 meters and 0.09 meters in the central and southern lake areas, respectively.

4. Discussion and Suggestions

(1) Within a watershed, major floods often create a distinct water surface slope in plain lakes, and the “dynamic storage capacity” contained in this process is frequently overlooked in traditional hydrological forecasting. Notably, the lake’s water surface slope is not only determined by floods within the watershed, but also by the top-supporting effect of floods both inside and outside the watershed. Using Poyang Lake as a reference, future research could explore the correlation and patterns between the strength of river-lake top-supporting (f) and the lake surface slope (dz) through statistical methods.This understanding can enhance traditional hydrological forecasting. By continuously monitoring and evaluating the top-supporting (f), the corresponding surface slope (dz) can be precisely pinpoint. Subsequently, by multiplying this dz value by the lake area (A), we can calculate the “dynamic storage capacity”. This approach provides a more accurate and scientific basis for calculating and revising the actual water storage capacity of such lakes.

(2) When a plain lake is essentially a vast floodplain, utilizing surrounding flood diversion areas for flood regulation becomes a crucial method to reduce flood damage in the region. To effectively respond to extreme floods, Jiangxi Province has strategically established four flood storage areas around Poyang Lake: Kangshan, Zhuhu, Huanghu, and Fangzhou Xietang, covering a total area of 506 square kilometers with an effective flood storage capacity of 2.5 billion cubic meters. Additionally, 229 Semi-Restoration polder areas are scattered around the lake, which can divert a cumulative 2.6 billion cubic meters of floodwater when necessary, further enhancing the region’s flood control capabilities. Despite the establishment of eight hydrological stations around the lake, comprehensive monitoring of such a vast lake remains challenging. Currently, most studies on the effectiveness of these flood diversion areas are based on the assumption of a flat lake surface, using water levels from hydrological stations near the flood diversion areas as boundary conditions for flood diversion calculations. However, this study found that major floods within the watershed can cause higher water level rise phenomena, in lake areas along their propagation paths. Simultaneously, under the influence of river-lake top-supporting effects, the overall water surface drop (dz) of the lake can reach up to 0.28 meters. These factors undoubtedly interfere with the accuracy of the original flood diversion calculation scheme in the flood diversion areas. Therefore, it’s recommended to utilizing a two-dimensional hydrodynamic model to obtain more precise external lake water level process data for the flood diversion areas during major floods within the watershed, especially when the river-lake top-supporting intensity (f) is less than 4. Based on these data, we can conduct more accurate flood diversion calculations to effectively respond to flood threats and ensure regional safety.

(3) Major floods within a watershed often trigger localized extraordinary water level rise phenomena in plain lakes, and these phenomena locations are closely related to the flood propagation path. Therefore, by deeply analyzing the propagation path and influence range of incoming floods, it becomes possible to anticipate potential areas of extraordinary water level rise based on the source of the floods. This predictive capability enables the implementation of focused protective measures, effectively mitigating flood risks. Additionally, different flood propagation paths have significant impacts on lakes. Taking the “Five Rivers” as an example, when they experience floods of the same magnitude, their impacts on Poyang Lake vary. By utilizing the maximum water level rise at stations as an indicator to assess impact, the influence hierarchy of the “Five Rivers” on the lake can be approximated as follows: Fu River ≈ Xin River ≈ Rao River > Gan River > Xiu River. A greater impact naturally implies a corresponding increase in flood control pressure. Therefore, it is feasible to optimize the scheduling management of the lake’s flood control projects based on the flood distribution characteristics resulting from different source floods. For instance, under the same regulation scheme, regulating floods from the Fu River, Xin River, and Rao River can more effectively change the water level in the central and southern regions of Poyang Lake compared to the Xiu River and Gan River, thereby reducing flood control pressure and ensuring the safety of the lake and surrounding areas.

5. Conclusions

(1) Flood propagation characteristics in Poyang Lake

As a typical plain lake connected to rivers, Poyang Lake’s annual maximum outflow is mainly influenced by floods within the watershed, while its annual highest water level is determined by floods from the Yangtze River outside the watershed. Based on historical hydrological data and simulation analysis, the flood peak discharge usually reaches the lake outlet within 48 hours, while the flood peak water level takes an average of 54 hours to propagate. It’s worth noting that the lake’s preexisting water storage can accelerate the arrival time of the peak discharge. However, when lake floods encounter Yangtze River floods, the peak water level’s arrival time may be extended by up to 10 days due to river-lake top-supporting effects.

(2) Flood propagation paths and their impacts

Floods from different sources follow distinct propagation paths after entering Poyang Lake. These paths not only affect the travel time of floods but also directly relate to the degree of impact on the lake area. Specifically, after the floods from the “Five Rivers” enter the lake,the flood peak transmission distance is ordered as Xiu River < Gan river < Rao River < Xin River < Fu River, resulting in the flood peak of the Xiu River reaching the lake outlet 8 hours earlier than the Fu River. Additionally, the propagation paths make a greater impact on the central and southern lake areas, especially floods from the Fu River, which cause significantly highest water level rise in the lake compared to other rivers under the same flow rate.

(3) Poyang Lake Water surface slope and Yangtze River top-supporting effects

The water surface slope of Poyang Lake is significantly influenced by the top-supporting effects of the Yangtze River. When the flood flow rate of the Yangtze River reaches more than four times that of the “Five Rivers” (i.e., the top-supporting intensity f value exceeds 4), the lake Water surface remains relatively flat, exhibiting reservoir-like characteristics. Conversely, during major floods within the watershed, the water surface slope in the lake rises rapidly, and the “dynamic storage capacity” inherent in the surface slope can reach up to 840 million cubic meters. This important factor may not have received due attention in traditional hydrological forecasting.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft preparation, Q.W. and Z.W.; writing—review and editing, Z.W. and Z.H.; supervision, X.X. and W.Y.; funding acquisition, T.W. and X.Y.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Key R&D Program of China (Grant No. 2022YFC3201804, 2022YFC3202603), the Major Science and Technology Program of the Ministry of Water Resources of China (Grant No. SKS- 2022010), the Jiangxi Province Key R&D Program Projects (Grant No. 20213AAG01012), the Science and Technology Project of the Water Resources Department of Jiangxi Province (Grant No. 202124ZDKT02, 202224ZDKT13, 202325ZDKT04, 202426ZDKT33).

Data Availability Statement

All data of the model used in this research can be requested from the corresponding author through the indicated e-mail.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bhave, A.G.; Bulcock, L.; Dessai, S.; et al. Lake Malawi’s threshold behaviour: A stakeholder-informed model to simulate sensitivity to climate change. Journal of Hydrology 2020, 584, 124671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opere, A.; Ogallo, L.A. Natural disasters in Lake Victoria Basin (Kenya): Causes and impacts on environment and livelihoods. United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), Pan AfricanSTART Secretariat (PASS), 2006, 135-148.

- Wan, R.; Yang, G.; Wang, X.; et al. Research progress on the relationship between rivers and lakes in the middle reaches of the Yangtze River. Lake Science 2014, 26, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- McDermott, T.K.J. Global exposure to flood risk and poverty. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, S. Review and Reflection on the Floods of Poyang Lake in 2020. Water Resources Protection 2021, 37, 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, C.; Yang, H. Optimized Scheduling of Semi-restoration polder areas Flood Control in Poyang Lake. Yangtze River 2009, 40, 9–11. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, C.; Chen, L.; Chen, Y.; Liu, X.; Peng, Z. The overall idea of optimizing the scheme of dealing with super standard flood in Poyang Lake area. Yangtze River 2021, 52, 29–33. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, S.; Wu, Q.; Wang, Z.; Wu, L.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, G. Investigating Flood Characteristics and Mitigation Measures in Plain-Type River-Connected Lakes: A Case Study of Poyang Lake. Water 2024, 16, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Wang, Z.; Wu, L.; et al. Hydrodynamic simulation of Poyang Lake under flooding in rivers and lakes. China Rural Water Resources and Hydropower 2023, 11, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, G.; Qin, Z. ; Calculation method for flood in the Poyang Lake section. Lake Science 1998, 10, 31–36. [Google Scholar]

- Gang, Li, Zhangjun Liu, Jingwen Zhang, Huiming Han, Zhangkang Shu,Bayesian model averaging by combining deep learning models to improve lake water level prediction. Science of The Total Environment 2024, 906, 167718. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Min, Q. Analysis of flood characteristics in Poyang Lake in the 1990s. Lake Science 2002, 14, 323–330. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Z.; Fu, J. Quantitative analysis of the hydrological relationship and evolution between the Yangtze River and Poyang Lake. Journal of Water Resources 2018, 49, 570–579. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Zhu, L.; Wang, J.; et al. Quantitative indicators for the causes and occurrence conditions of Yangtze River backflow into Poyang Lake. Progress in Water Science 2020, 31, 203–213. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Ni, Z. The Development and Evolution of Poyang Lake and the Impact of Changes in Jianghu Relations. Journal of Environmental Science 2015, 35, 1265–1273. [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang, Q.; Xiong, Z.; Si, W.; et al. A study on the evolution characteristics of flood indicators in Poyang Lake under changing environments. Jiangxi Water Conservancy Technology, 2023, 49, 213–218. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, D.; Xiong, M.; Zhang, J. Analysis of Hydrological Characteristics of Poyang Lake. People’s Yangtze River 2001, 32, 21–27. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Yu, M.; Huang, Y.; et al. The Impact of the Poyang Lake Water Conservancy Hub on the Hydrodynamic Processes during the Flood Season in the Jianghu. Journal of the Yangtze River Academy of Sciences 2023, 40, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Y.C.; Li, X.W.; Xu, H. Effects of topographic changes on the water dynamics in flood season inhe tail of Ganjiang River network. Journal of Hydropower Engineering 2022, 41, 9–21. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.L.; Tan, Z.J. Influence of sand mining on river bed in middle and lower reaches of Ganjiang River. Hydropower and New Energy 2010, 63–65. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z.W.; Xu, X.F.; Wang, Z.C.; et al. Analysis of the influence of the evolution of the water channel into the river of Poyang Lake on the water level of the lake. Water Power 2021, 47, 37–40. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.C.; Xu, X.F.; Huang, Z.W.; Wu, N.H.; Zhou, S.F. Siltation characteristics of the tail reach of Ganjiang river under the regulation of estuary gates. water science & Technology Water Supply 2020, 20, 3707–3714. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, D.Y.; Li, R.F.; Wang, Y.W. Analysis of flood control and disaster reduction situation in Poyang Lake District after removing embankments and returning farmland to the lake. Hydrology 2004, 06, 26–31. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Z.P.; Wang, S.G. Evolution of erosion and deposition in Poyang Lake and its hydrological and ecological effects. Water Resources and Hydropower Technology (Chinese and English) 2022, 53, 66–78. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; Hu, T. A study on the relationship between water level and flow rate at the mouth of Poyang Lake. China Rural Water Resources and Hydropower 2023, 11, 112–118. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, B.Y.; Li, Z.Z. Direct fitting of water level flow relationship rope loop curve during flood season. Hydrology 1998, 05, 27–30. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, C.B.; An, X.M.; Zhang, Q.H. Finite element parallel numerical simulation of two-dimensional shallow water flow. Journal of Water Resources 2002, 05, 65–68. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).