1. Introduction

We define ecosystemic services as those services that provide material or non-material benefits to the inhabitants of a landscape from its water, food, medicines and raw materials. They are grouped into four types: provisioning, regulating, supporting and cultural. Ecosystemic Cultural Services (ECS) provide non-material benefits (education, cultural diversity, sources of inspiration, spirituality and religious values, aesthetic enjoyment, social relations, rootedness or belonging, cultural heritage, recreational and ecotourism services, scientific knowledge).

2. Objectives

We seek to classify the ECSs according to the facet in which they offer this benefit and to analyse their nature in each of them, in order to outline some Areas of Presumed Character or areas of homogeneous and very marked potential dynamics, which can be identified by their physical and social characteristics, and serve for land-use planning.

3. ECS Analysis Facets

The cultural landscape is created from a natural landscape by a cultural group. Culture is the agent, nature is the medium, the cultural landscape is the result [

1]. Thus, the term cultural landscape encompasses a diversity of manifestations of the interactions between humankind and its natural environment [

2]. These interactions can be classified into three domains [

3]: the geo-system (environment and ecology) [

4]; the socio-system (systems of production and power) [

5]; and the cultural system (collective identity). We propose these three: memory, image and socio-system.

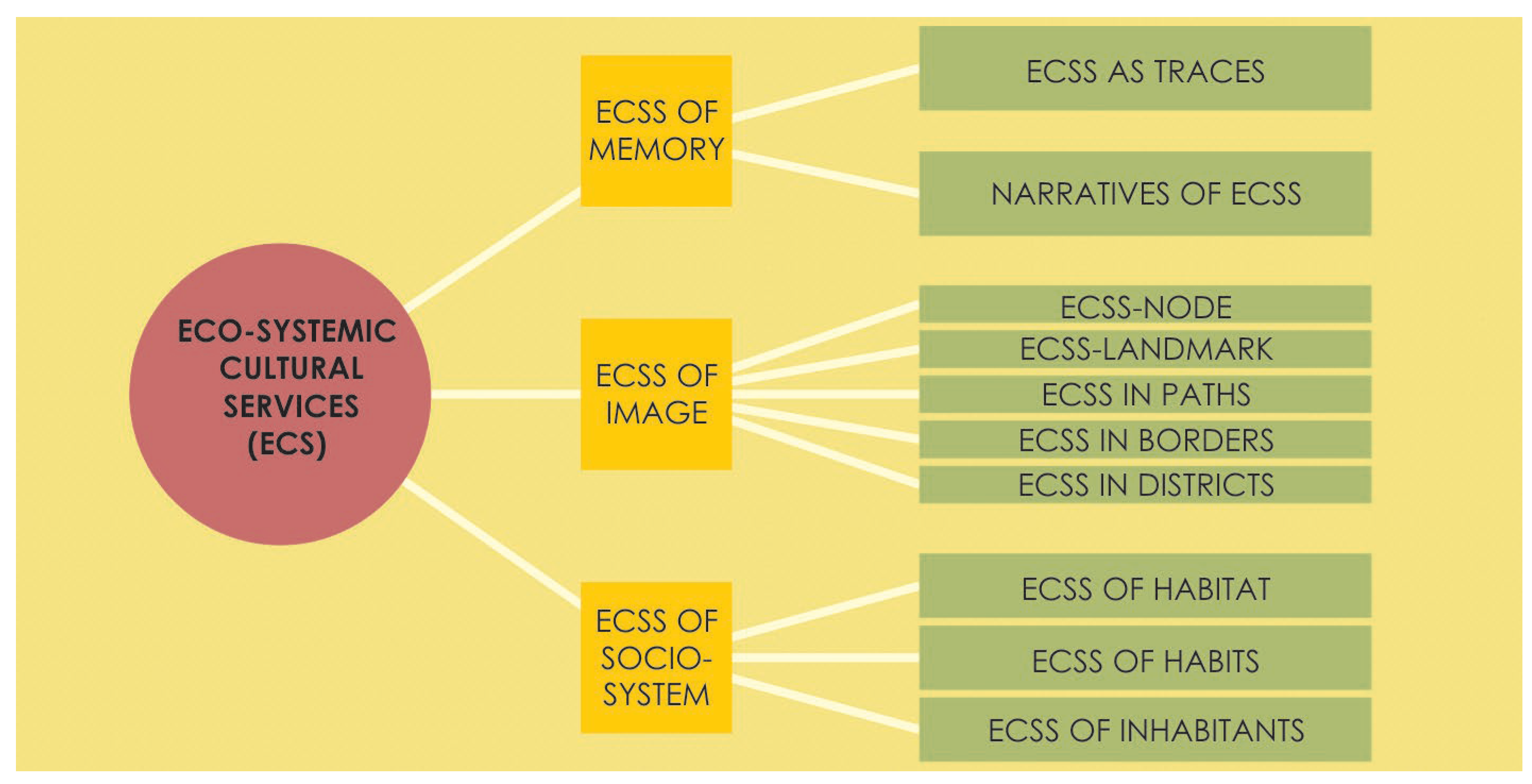

Figure 1.

Facets of ECS analysis.

Figure 1.

Facets of ECS analysis.

In the socio-system, we estimate the economic value of cultural value. The utility, price and importance that individuals or markets assign to commodities cannot be transposed directly to culture because, in culture, value is not attributed. This cultural value subsists as an indication of the merit or importance of a work, an object, an experience or any other cultural element [

6]. However, cultural materialism provides the means to reintegrate culture into the same material and natural world as the economy [

7]. This allows defining ECS as a resource of a socio-system or human habitat with interaction with the environment, studied from Landscape Ecology or Geoecology [

8]. This approach must be complemented with a Capital Analysis [

9].

Landscapes as potential integrators of fragmented heritage [

10] are an expression of the diversity of the cultural and natural heritage and a foundation of identity [

11]. The Geography of Memory [

12] locates history and its representations in space and landscape. It answers the question of where memory is in terms of places and sites that empty a certain vision of history into a mould of commemorative permanence [

13]. Some ECSs become lieux de memoire. They are significant units, of a material or ideal order, of which the will of men or the work of time has made a symbolic element of the heritage of memory of any community [

14].

The landscape as part of the territory, as perceived by the population [

15] acquires a socially constructed "image" defined by the points of coincidence that can be expected to appear in the interaction of a unique physical reality, a common culture and a basic physiological nature [

16]. The Geography of Perception [

17] identifies the elements of the image and their relationships. They are reflected in mental maps of the environment that the viewer constructs, as the result of learning and as determinants of human behaviour [

18].

4. ECSs of Memory

Collective memory is spatially constructed through its anchoring in certain material places [

19]. These places become meaningful when activated by a narrative [

20]. If such a narrative is imposed as a mass-marketed memory that we consume, it becames, at first glance, nothing but an "imagined memory", and are thus much more easily forgotten than lived memories [

21]. To avoid this, narratives must be both scientific and popular.

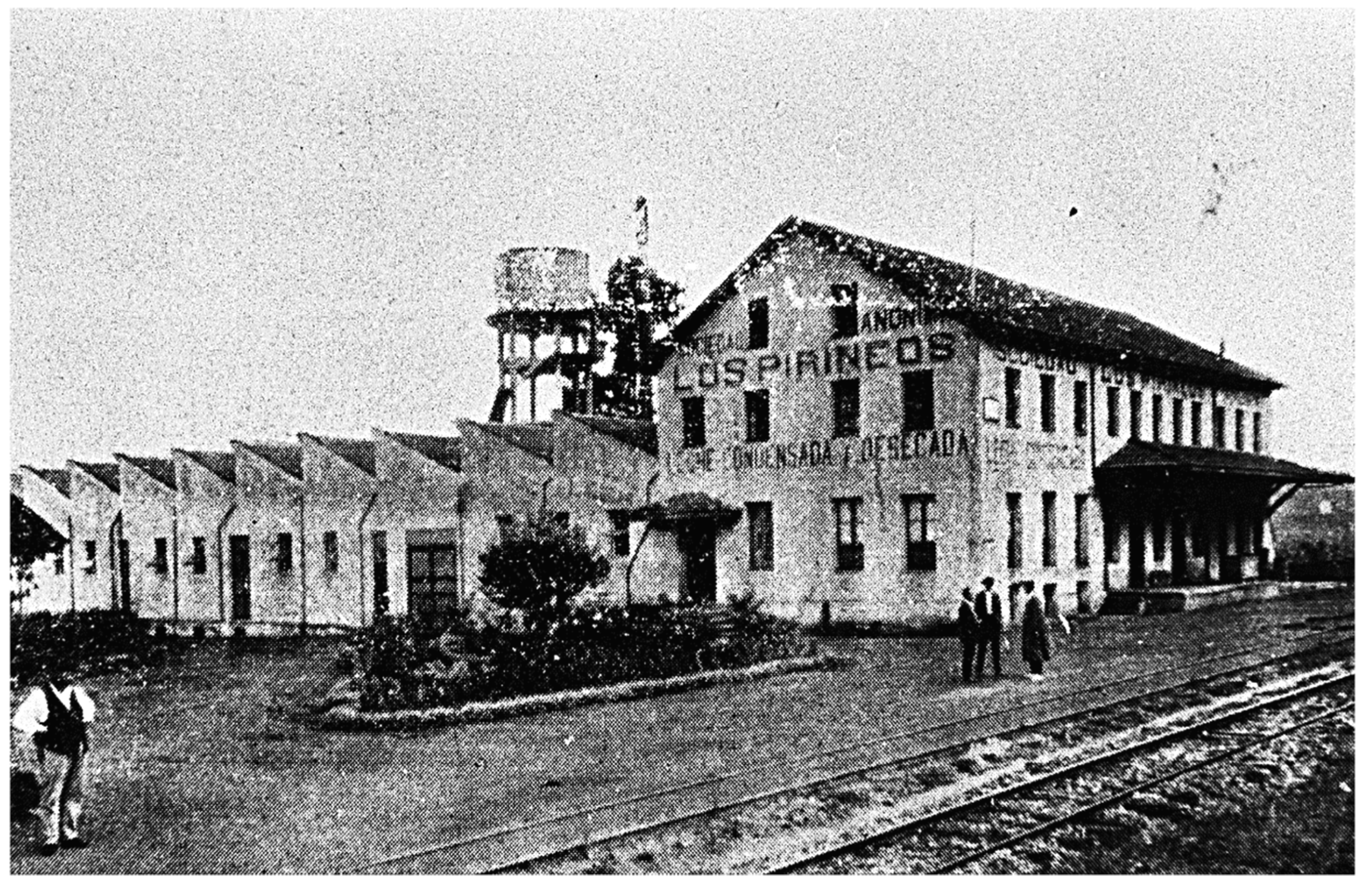

Figure 2.

ECSs of memory: "Los Pirineos" factory (1913), with the water tank in the background, as a trace activated by the narrative of the industrialisation of Gernika (Bizkaia) before the Spanish Civil War. Source: Gernikazaharra archive.

Figure 2.

ECSs of memory: "Los Pirineos" factory (1913), with the water tank in the background, as a trace activated by the narrative of the industrialisation of Gernika (Bizkaia) before the Spanish Civil War. Source: Gernikazaharra archive.

4.1. Narratives "of History" as Activators of ECSs of Memory

To construct the "narratives of history" we must analyse place names, review written, graphic and audiovisual sources, aerial photography, cartography and handle, if possible, all existing editions, which allow an evolutionary approach, and the scales most appropriate to the dimension and characteristics of the landscape of cultural interest [

22].

4.2. Traces "of History" as ECSs of Memory

Some ECSs of memory -sometimes only the shadows that remain of them hidden among later factories in time- seem to tell us, like Horace, non omnis moriar, I shall not die at all [

23]. These are cases of absent memory or deliberate forgetting, due to the conception of the past as something alien to the present [

24]. Society feels the need to endow space with positive meanings [

25].

4.3. Narratives "of Stories" as Activators of ECSs of Memory

According to some authors, we are facing a crisis of the conception of history as a tool for social transformation" [

26], a disaffection towards "dead memory" [

27]. It is collective memory, and not so much history, that influences society [

28], generating feelings of belonging, of anchorage, desires to inhabit.

Memory will be determined by a subjective view of the traces of the past. These traces are not reliable records of what actually happened, but the traces that events have left in matter (living or inert) to be interpreted and used later [

29]. This perception varies over time. Memory is always transitory, notoriously unreliable, haunted by the spectre of oblivion, in short: human and social [

30]. It presents the ductility of a social construction of memory [

31] which is periodically revived through ceremonies and public rites, forms a kind of common heritage that the individual encounters from birth and which is imbricated with his or her own individual memories [

32]. The importance of these rites as narratives assumed by the collective is based on the triple shift of social disciplines towards the subjective, the narrative and the hermeneutic [

33].

4.4. Traces "of the Stories" as ECSs of Memory

The social construction of these narratives allows the identification of ECSs of belonging, popular cultural heritage, cultural diversity, sources of inspiration and religious values.

5. ECSs of Image

Each individual has a mental image of his or her living space depending on where he or she lives. They dominate the area between their home and the place where they work or shop and socialise on a daily basis; they also have a clear image of the suburbs due to travelling outside their area. The rest of the landscape he inhabits he knows mainly from the media, because he does not really use it [

34].

Figure 3.

ECSs of the image: water tank of "Los Pirineos" (1913) as a visual reference of image for the residents of Gernika (Bizkaia).

Figure 3.

ECSs of the image: water tank of "Los Pirineos" (1913) as a visual reference of image for the residents of Gernika (Bizkaia).

What is remarkable is that we can (partially) share with other living beings those images that we capture in our own brain cave. For this to happen, their brains must be able to generate image maps, as we do. According to Damasio, this is what the brain is all about, being able to construct maps. In this it differs from the minds possessed by many other living beings, which only process information [

35].

5.1. ECSs of Image: Nodes

Nodes are the strategic foci at which the observer can enter, typically confluences of paths or concentrations of a certain feature [

36]. The nodes are areas of confluence of flows of very different kinds, whether of people or of the transport that contains them: bus terminals, railway stations, airports; but also parks, squares, pedestrian areas, banks, hospitals or meeting places: street corners, cafés, dance halls. They are true signs of internal polarity, in close association with the paths that facilitate convergence and closely linked to neighbourhood life as a factor of social rapprochement [

37]. They are understood as points in the city - most often street intersections - that act as nodes or focal points. The citizen can enter or pass through these nodes, so they represent easily identifiable phases of movement within the city. They are often clearly delimited physical elements, such as a square. They are nodes, for example, Piccadilly Circus, Times Square, Red Square and I'Etoile [

38]. Their crossroads nature will accentuate their character. It is because as decisions must be made at junctions, people sharpen their attention at these places and perceive neighbouring elements with a greater clarity of flow [

39].

5.2. ECSs of Image: Landmarks

Landmarks are reference points that are considered external to the observer. They are simple physical elements that in scale can vary considerably [

40]. Many serve to orient us. The use of landmarks implies the choice of one element from a multitude of possibilities. The key physical characteristic of this class is uniqueness, an aspect that is unique or memorable in context [

41]. In Lynch's essays, the concatenation of landmarks make more sense when a consecutive series of landmarks, in which one detail evokes in anticipation the next and in which key details elicit specific movements of the observer, appear as a common form of movement in the city [

42].

5.3. ECSs of Image: Footpaths

Paths are the conduits that the observer normally, occasionally or potentially follows [

43]. They do not need to have physical continuity; the mere fact of being on a street that by its name extends into the heart of the city, however far away it may be, gives a pleasant feeling of relatedness [

44]. This is because people tend to think in terms of destinations of paths and points of origin [

45]. They must, however, have character. When the main paths lacked identity or were easily confused with each other, the whole image of the city presented difficulties [

46]. This character is defined by formal aspects. In the simplest sense, streets that suggest extremes of width or narrowness attract attention [

47].

5.4. ECSs of Image: Borders

Some image ECSs mark a more or less permeable barrier in the systemic relations of landscapes. They are edges or linear elements that are not considered as paths. They are usually the boundaries between areas of two different classes [

48].

5.4. ECSs of Image: "Districts"

Neighbourhoods or districts are the relatively large urban areas which the observer can enter by thought and which have a certain character in common [

49]. They resemble "patches" or areas of land relatively homogeneous internally with respect to structure and vegetative age [

50]. They are superficial in nature, neither punctuated like nodes or landmarks nor linear like footpaths. They are homogeneous, with thematic continuities that can consist of an infinite variety of constituent parts, such as texture, space, form, detail, symbols, building type, use, activity, inhabitants, degree of maintenance and topography [

51].

6. ECSs of the Socio-System

Figure 4.

ECSs of the socio-system: "Los Pirineos" water tank (1913) integrated in the extension of a supermarket as an icon of the identification with the town of Gernika (Bizkaia) of the international chain that runs it.

Figure 4.

ECSs of the socio-system: "Los Pirineos" water tank (1913) integrated in the extension of a supermarket as an icon of the identification with the town of Gernika (Bizkaia) of the international chain that runs it.

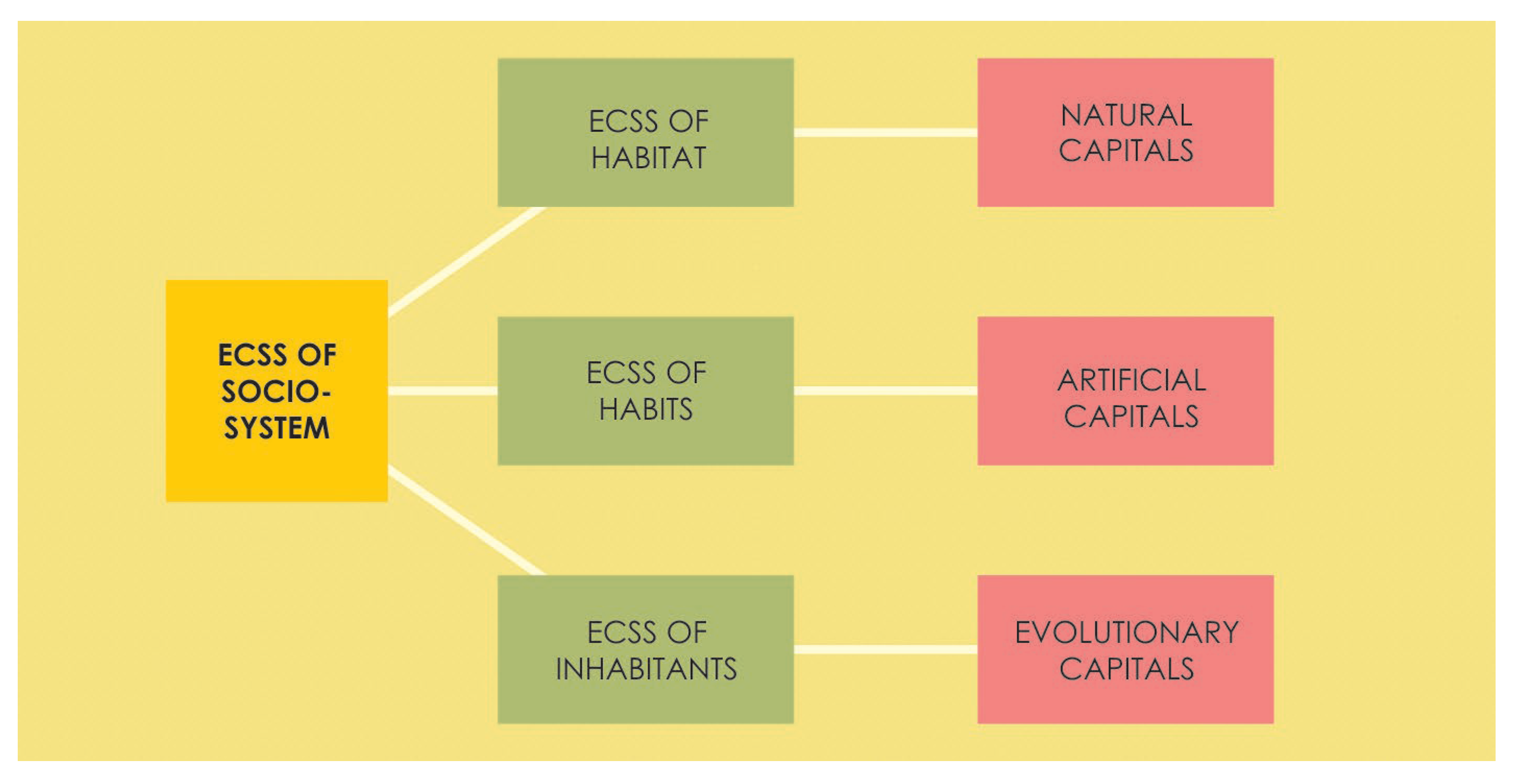

Figure 5.

Classification of ECSs in the socio-system.

Figure 5.

Classification of ECSs in the socio-system.

6.1. ECSs with "Natural" or Socio-Environmental Capitals

Natural capitals are understood in ecological economics as the free gifts of Nature that pre-exist the foundation of the city, mainly the natural settings determined by the geographical position [

52]. Their measure depends on geographical location and climate, orography, hydrography, geology and seismology, and natural connectivity [

53]. We can group them under three headings: socio-environmental assets, socio-environmental resources and socio-environmental corridors.

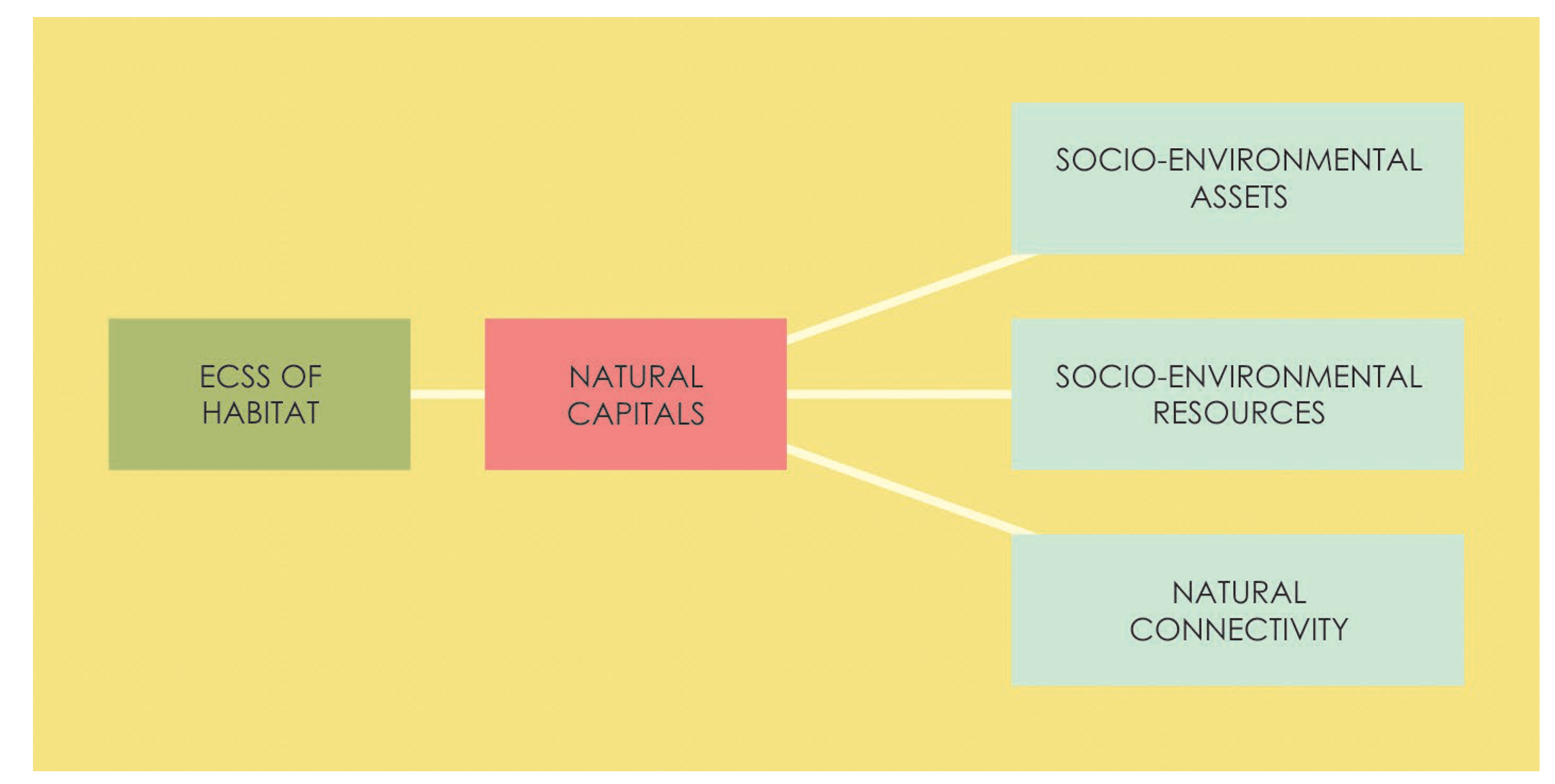

Figure 6.

ECSs with natural capitals.

Figure 6.

ECSs with natural capitals.

6.1.1. ECSs with Socio-Environmental Assets

Socio-environmental assets are those places that contribute to making the stay in the considered landscape pleasant. They are becoming increasingly important, as a more concrete and more positive attitude towards our social system implies, at the same time, the study of the problem of leisure [

54]. They are manifested if there is a perception of a nature that is not anthropised, native animal and plant species, areas that are not altered by constructions or artificial infrastructures. The ECSs that are generated for their enjoyment (trekking, mountain biking, cyclo-cross, mycology) can contribute to the character of this lived space or, if unregulated, can cause discomfort to its inhabitants.

Socio-environmental assets are not natural capital in the Malthusian sense of political economy. We do not consider their direct utility for the production of goods and services. They condition the environmental balance and biodiversity, the comfort or enjoyment that beauty, for example, can provide. Areas of naturalistic interest with figures of protection, those that form part of the socio-ecological infrastructure, and areas that help to define the "environmental sensitivity map" and which are not included in the above (natural spaces of geological interest, wetlands, marine habitats, summits, other areas of catalogued interest) will be considered as ECSs with socio-environmental assets.

6.1.2. ECSs with Socio-Environmental Resources

Socio-environmental resources can be considered physical capital (material goods that contribute to the production of other goods) [

55]. We are talking about raw materials or foodstuffs offered by nature, the exploitation of which has characterised local cultures (agro-livestock or forestry farms in the traditional area of influence of some urban centres, for example).

6.1.2. ECSs as Socio-Environmental Corridors

The connectivity or natural isolation of the landscape depending on its orography (plains or passable valleys, among the positive factors; mountain ranges among the negative or barriers) is also a physical capital. The corridors thus generated would be considered ECSs that determine the culture of the place, facilitating certain communications and exchanges between inhabitants.

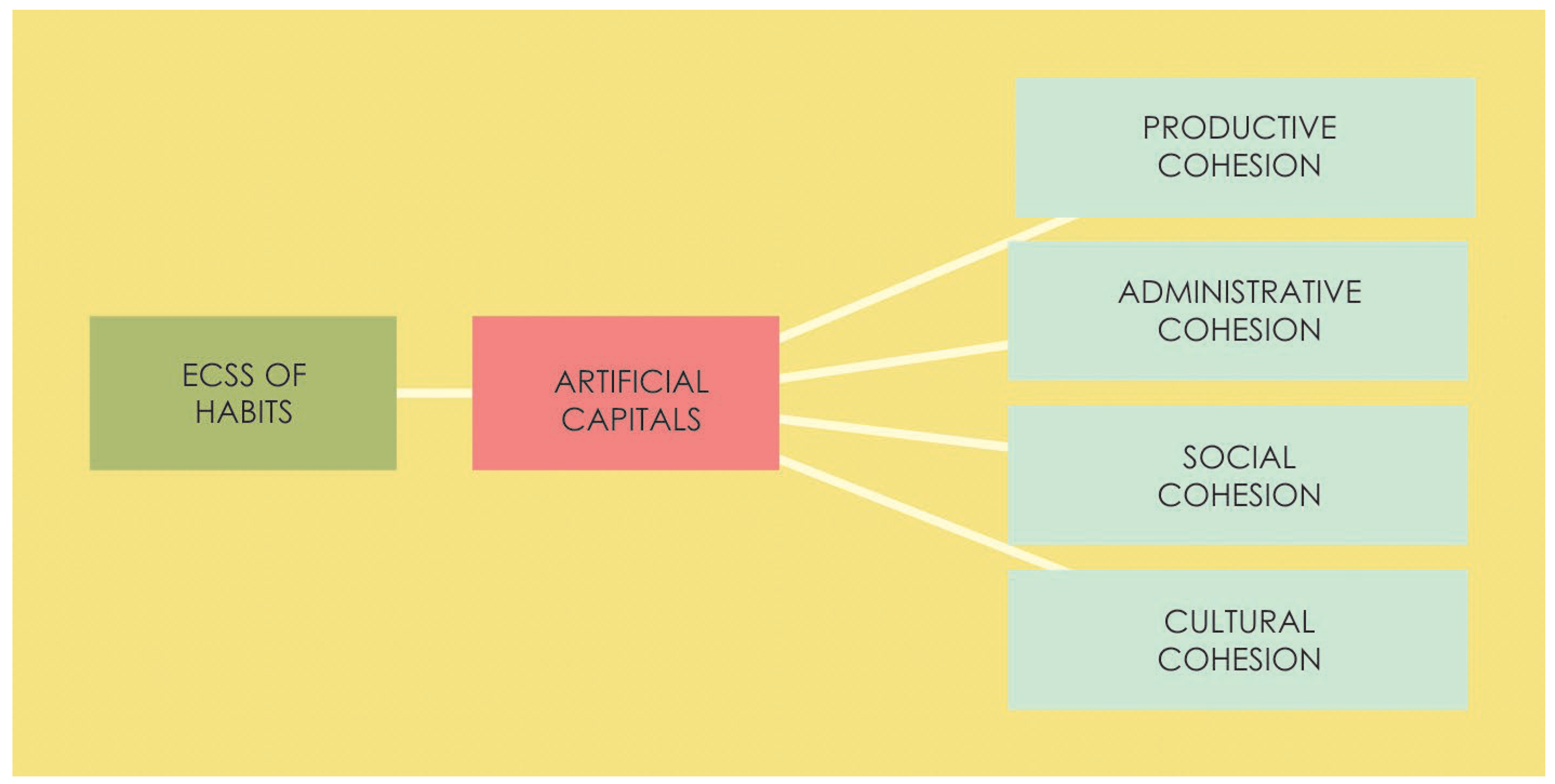

6.2. ECSs with Artificial Capitals

Artificial capitals can be defined as those that are the product of human activity throughout history and have left a physical, social, economic or cultural imprint [

56]. They can be probed with objective indicators, but their reality is changeable and subjective. The discovery that approximate knowledge exists turns the systemic approach into a science [

57].

Artificial capitals fall into four main groups: political demarcation (territory and governance), people, agents and culture.

Political demarcation would include local authorities, territorial boundaries, places in the immediate environment.

People's capitals include ethnic diversity, linguistic diversity, demographic configuration, migration.

Those of the agents include industry, trade and mobility.

Culture capitals include dynamism in this field [

58].

We identify artificial capitals by measuring the rootedness of the habits of a social group according to its level of cohesion in the productive, administrative, social and cultural spheres [

59].

Figure 7.

ECSs providing artificial capitals.

Figure 7.

ECSs providing artificial capitals.

6.2.1. ECSs for Productive Cohesion

Productive cohesion includes what is related to socio-economic development.

Its indicators are the number and nature of industries, the type and size of services provided in the tertiary sector, and the ease and variety of communications. We will measure the sense of perceived dynamism by weighing up proposals for economic activity put forward in a Social Dialogue process. This will subsequently enable us to delimit ECSs linked to the recycling of spaces already built. In the current ecological situation, the choice against the model of change and in favour of maintenance and preservation becomes an essential imperative [

60].

6.2.2. ECSs for Administrative Cohesion

Administrative cohesion has two aspects. On the one hand, its territorial dimension, reflected in the adequacy of governance boundaries. On the other hand, its institutional aspect (authority, agility in decision-making), as a tool for project leadership.

The non-coincidence of the administrative territory with the natural territory of the community generates tensions in the anchoring of its members. The identification of the citizens with the administrators, the capacity of the technical staff to solve and manage, the potential support of the private economic agents they can count on, the level of political stability, the resources derived from taxation managed by the very institutions that decide on the projects, and the degree of coordination and harmony of the different layers of power reinforce multilevel governance. The “landscape” is not saved if the "country" is not saved [

61].

We can see these capitals reflected in the capacity of the administrations to call on citizens during public socialisation sessions. Also in the agility of the responses of the administrations themselves to requests for the provision of documentation and the quality of these responses.

6.2.3. ECSs for Social Cohesion

There is no univocal definition of social cohesion [

62]. However, social cohesion can be defined as the degree of consensus of the members of a social group on the perception of belonging to a common project or situation. In this definition the emphasis is on perceptions and not on mechanisms [

63]. Indirectly, social cohesion is based on the conformity that arises from segmented similarities, related to territory, traditions and group uses [

64].

On the one hand, we will identify social cohesion by the dialectic between the instituted mechanisms of social exclusion/inclusion and the responses, perceptions and dispositions towards the way these mechanisms operate [

65].

The mechanisms include, among others, employment, educational systems, entitlement and policies to promote equity, welfare and social protection [

66].

On the other hand, we will analyse the behaviours and values of the subjects as a substantial part of the habits of the society to which they belong.

A socially cohesive community is characterised by a recognition of differences and tolerance, and a significantly equitable access to social services [

67].

Social cohesion is quantified by the percentages obtained in the Social Dialogue in response to the question of inclusiveness.

6.2.4. ECSs for Cultural Cohesion

Cultural cohesion is studied as independent of social cohesion [

68], in two aspects:

That relating to cultural facilities and artistic production, in which a set of economic, non-economic and institutional actors decide to use some of the shared idiosyncratic resources (artistic, cultural, social, environmental), in order to develop a common project, which is simultaneously an economic project and a life project [

69].

That reflected in cultural tourism, with issues such as the right to cultural heritage, to the preservation of cultural memory, and of the identity of ethnic groups and differentiated cultural groups [

70].

To establish the degree of cultural cohesion, the density of cultural endowments and the presence of active cultural associations are measured.

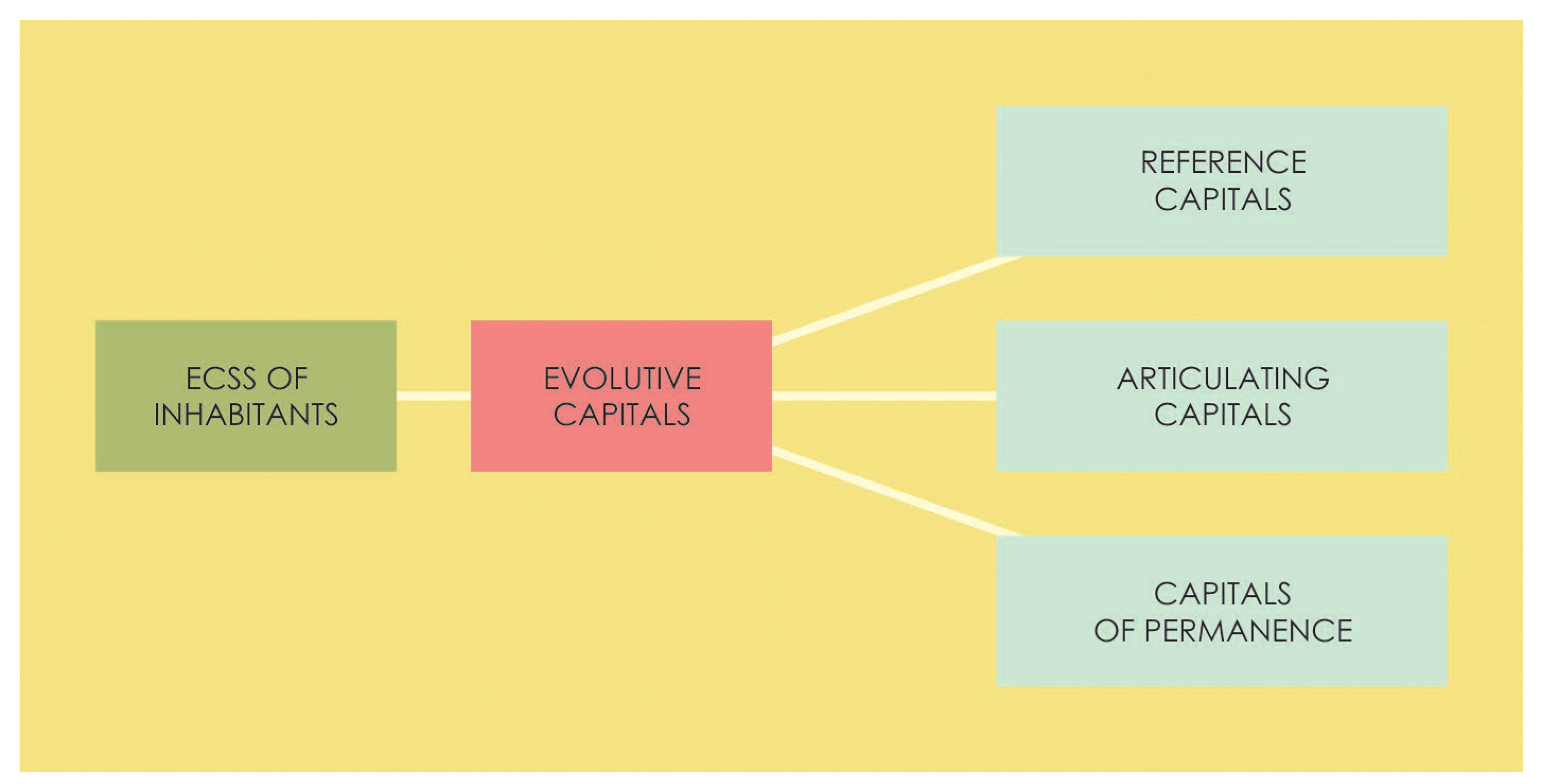

6.3. ECSs with Evolutive Capitals

Figure 8.

ECSs providing evolutive capitals.

Figure 8.

ECSs providing evolutive capitals.

Evolutive capitals are defined as those that constitute the current qualification or evolutionary potential of that city, in terms of collective competencies for sustainability [

71]. They derive from the vitality, transformation potential and collective competencies of its inhabitants [

72]. They are classified into three groups: referential (identity), articulating (relational capacity) and permanence (resilience) [

73].

6.3.1. ECSs to Strengthen Referential Capitals

Referential capitals are related to the feeling of anchoring.

To evaluate them, the "desire to inhabit" and the attachment to the place where one lives are measured. They will be reflected in a higher percentage participation in meetings to decide their future. The percentage of contributions on the topic of heritage and identity is also taken into account.

6.3.2. ECSs to Strengthen Articulating Capitals

The articulating capitals indicate the capacity of the inhabitants to establish internal and external relationships that strengthen the group as a society and allow generating contacts (social welcoming capacity or friendliness).

The diversity of neighborhood associations (non-cultural) that have taken part in meetings with citizens is measured.

6.3.3. ECSs to Reinforce the Permanence Capitals

The permanence capitals represent the resilience to changes due to evolution of structures (internal receptivity) or to external input (innovation) [

74].

Those of internal receptivity are the potential factors of endogenous development, defined as the capacity of a territory to transform its socioeconomic system and its ability to react to challenges [

75] (educational value, scientific knowledge and recreational services or spirituality, reflected in ECSs).

Those of innovation are reflected in the contributions in areas of Social Dialogue such as Mobility, Natural Resources and Waste, Economic Activity and Climate Change.

7. Conclusions

The character of the ECSs present in them allows us to classify Areas of Presumed Character (APCs) into:

- -

Unitary Areas in each facet.

- -

Gateway Areas of natural and traditional connection

- -

Transition Areas

- -

Hybrid Areas

The Unitary Areas of Memory have heritage character determined by remarkable narratives in them.

Image Unit Areas will be those structured by nodes, landmarks, edges, perceptual itineraries and districts.

Socio-system Unit Areas are characterized by natural, artificial and/or evolutionary capitals.

Gate Areas have natural connectivity to neighboring territories.

Transition Areas do not fall into any of these categories. They would be susceptible to host buffers or expansion zones.

Hybrid Areas can be assimilated to "Intermediate Territories" [

76].

The characterization of these APCs based on the nature of their ECSs constitutes the basis for the management of one of the layers of the territory: that of Landscape, Cultural and Natural Heritage and Tourism Resources.

References

- SAUER, Carl O. "The Morphology of Landscape", in University of California Publications in Geography nº 2, 1925, pp. 19-54.

- Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention. World Heritage Centre, 1999.

- RODRÍGUEZ, José, "La ciencia del Paisaje a la luz del paradigma ambiental", Revista trimestral Geonotas, vol. 2, nº 1, Departamento de Geografía-Universidad Estatal de Maringá, Brasil, www.dge.uem.br/geonotas/vol2-1/geoteoria.htm. 1998.

- ROUGERIE, Gabriel y BEROUCHACHVILI, Nikolaj, "Géosystèmes et paysages. Bilan et méthodes", París, Armand Colin (ed.), 1991.

- BERKES, Fikret y FOLKE, Carl, "Linking social and ecological systems for resilience and sustainability", in Berkes, F. & Folke, C. (Eds.). Linking social and ecological systems: Management practices and social mechanisms for building resilience, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 1998 pp 1-26.

- THORSBY, David, "Economy and Culture", Cambridge University Press, 2001, p 33.

- JACKSON, William A. "Cultural materialism and institutional economics", in Review of Social Economy, nº 54, 1996, pp. 221-244.

- TROLL, Carl, "Landscape Ecology (Geoecology) and Biogeocoenology: A Terminology study", in Geoforum, nº 8, 1971, pp. 43-46.

- CARRILLO, Francisco Javier, "Ciudades del conocimiento: El estado del arte y el espacio de posibilidades", in La innovación en la sociedad del conocimiento: Retos y oportunidades para los países iberoamericanos. Medellín, Colombia, 29 October 2004.

- LOPO, Martín, "Los "paisajes (culturales)" como potenciales integradores del patrimonio fragmentado; otro aporte para las clasificaciones desde una mirada territorial (nada apocalíptica)", in Jornadas paisajes culturales en Argentina, ICOMOS-Universidad Nacional de Rosario, 2007, p. 1.

- COUNCIL OF EUROPE, "European Landscape Convention", Madrid, Ediciones del Ministerio de Cultura, 2008; Ediciones del Ministerio de Medio Ambiente, 2007, [2000] 5.a.

- LÉVY, Jacques, LUSSAULT, Michel,. dirs. "Dictionnaire de la géographie et de l'espace des Sociétés, Paris, Belin, 2003 pp 443-604.

- FOOTE, Kenneth, AZARYAHU, Maoz, “Toward a geography of memory: Geographical dimensions of public memory and commemoration”, in Journal of Political and Military Sociology, vol. 35 (1), 2007, pp.125-144.

- NORA, Pierre, dir. “Les lieux de mémoire”, Paris, Gallimard, 1997, [1984-1992] 3 vols. II: 2.226.

- COUNCIL OF EUROPE, "European Landscape Convention", Madrid, Ediciones del Ministerio de Cultura, 2008; Ediciones del Ministerio de Medio Ambiente, 2007, [2000] 1.a.

- LYNCH, Kevin, La imagen de la ciudad, Barcelona, Gustavo Gili, 1984,1998, [Cambridge, MIT Press (ed.)1960] p 17.

- DOWNS, Roger M. "Geographic Space Perception: Past Approaches and Future Prospects", In C. Board et a/., eds., Progress in geography, no. 2,. Arnold, London. 1970, pp.65-108.

- LEWIN, Kurt A., "Dynamic Theory of Personality", McGraw-Hill, 1935.

- TOLMAN, Edward C. "Cognitive Maps in Rats and Men", in Psychology Review, no. 55, 1948, pp. 189-208.

- HALBWACHS, Maurice, "La mémoire collective" in Presses Universitaires de France, 1950 [2ème éd. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1967] p. 106.

- FOOTE, Kenneth, AZARYAHU, Maoz, "Toward a geography of memory: Geographical dimensions of public memory and commemoration", in Journal of Political and Military Sociology, vol. 35 (1), 2007, p.127.

- HUYSSEN, Andreas, "En busca del futuro perdido: Cultura y memoria en tiempos de globalización", Mexico, Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2002, p. 8.

- National Cultural Landscape PLAN, [online]. www.mcu.es/patrimonio/docs/MC/IPHE/PlanesNac/PLAN_NACIONAL_PAISAJE_CULTURAL.pdf , 2011, [accessed: [11/01/2014] pp 30-31.

- AZKARATE, Agustín, LASAGABASTER, Juan I. "Archaeology and the recovery of "forgotten architectures". La catedral de Santa María y las primitivas murallas de Vitoria-Gasteiz", in IV Congreso internacional restaurar la memoria. Archaeology, Art, Restoration, Valladolid, 2006, pp. 137-160.

- POULIOS, Ioannis, "Moving Beyond a Values-Based Approach to Heritage Conservation", in Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites, v. 12, nº 2, 2010. pp. 170-185.

- Orange, Hilary (2008): "Industrial Archaeology: Its place within the academic discipline, the public realm academic discipline, the public realm and the heritage industry", Industrial Archaeology Review, 30-2, 83-95.

- JULIÁ, Santos, "Bajo el imperio de la memoria" in Revista de Occidente, nº. 302-303, 2009, pp. 7-19.

- ERICE, Francisco, "Memoria histórica y deber de memoria: Las dimensiones mundanas de un debate académico", in Entelequia, no. 7, 2008, pp. 77-96.

- AGUILAR, Paloma, "Aproximaciones teóricas y analíticas al concepto de memoria histórica", Madrid, Instituto Universitario José Ortega y Gasset, 1996.

- ROSA, Alberto, BELLELLI, Guglielmo and BUCKHURST, David, "Representaciones del pasado, cultura personal e identidad nacional", in Educação e Pesquisa, v. 34, nº1, Jan./Apr, São Paulo, 2008, pp. 167-195.

- HUYSSEN, Andreas, "En busca del tiempo futuro", in Revista Puentes, year 1,Nº 2, December 2000, Buenos Aires, Comisión Provincial por la Memoria. Retrieved from: http://www.cholonautas.edu.pe/modulo/upload/Huyssen.pdf.

- CUESTA, Josefina, "Memoria e Historia. Un estado de la cuestión" in Ayer, nº 32, 1998, pp. 203-246.

- GARCÍA, Jacobo, "Lugares, paisajes y políticas de memoria: Una lectura geográfica", in Boletín de la A.G.E. nº 51, 2009, p 177.

- GARCÍA, Jacobo, "Lugares, paisajes y políticas de memoria: Una lectura geográfica", in Boletín de la A.G.E. nº 51, 2009, p 178.

- JONHSTON, Ron J. "Mental maps of the city: Suburban preference patterns", in Environment and Planning, 1971, vol. 3, pp. 63-72.

- ECHEVERRÍA, Javier, "Entre cavernas: De Platón al cerebro pasando por Internet", Triacastela, Madrid, 2013, ISBN: 978-84-95840-84-4, p 150.

- LYNCH, Kevin, La imagen de la ciudad, Barcelona, Gustavo Gili, 1984,1998, [Cambridge, MIT Press (ed.)1960] pp 62-63.

- ZAMORANO, Mariano, "Geografía Urbana: Formas, funciones y dinámica de las ciudades", Editorial Ceyne, Colección Geográfica, San Isidro. 1992. ISBN 950-9871-25-7 (Obra completa and 950-9871-33-8 (Volume 6) p 126.

- CARTER, Harold, "The Study of Urban Geography", Instituto de la Administración Local, Madrid, 1983, ISBN 84-7088-330-5 p 461.

- LYNCH, Kevin, La imagen de la ciudad, Barcelona, Gustavo Gili, 1984,1998, [Cambridge, MIT Press (ed.)1960] p 92.

- LYNCH, Kevin, The Image of the City, Barcelona, Gustavo Gili, 1984, 1998, [Cambridge, MIT Press (ed.)1960] p 98.

- LYNCH, Kevin, The Image of the City, Barcelona, Gustavo Gili, 1984,1998, [Cambridge, MIT Press (ed.)1960] p 98.

- LYNCH, Kevin, The Image of the City, Barcelona, Gustavo Gili, 1984,1998, [Cambridge, MIT Press (ed.)1960] p 103.

- LYNCH, Kevin, The Image of the City, Barcelona, Gustavo Gili, 1984,1998, [Cambridge, MIT Press (ed.)1960] p 68.

- LYNCH, Kevin, The Image of the City, Barcelona, Gustavo Gili, 1984,1998, [Cambridge, MIT Press (ed.)1960] p 63.

- LYNCH, Kevin, The Image of the City, Barcelona, Gustavo Gili, 1984,1998, [Cambridge, MIT Press (ed.)1960] p 70.

- LYNCH, Kevin, The Image of the City, Barcelona, Gustavo Gili, 1984,1998, [Cambridge, MIT Press (ed.)1960] p 68.

- LYNCH, Kevin, The Image of the City, Barcelona, Gustavo Gili, 1984,1998, [Cambridge, MIT Press (ed.)1960] p 66.

- LYNCH, Kevin, The Image of the City, Barcelona, Gustavo Gili, 1984,1998, [Cambridge, MIT Press (ed.)1960] p 79.

- LYNCH, Kevin, La imagen de la ciudad, Barcelona, Gustavo Gili, 1984,1998, [Cambridge, MIT Press (ed.)1960] p 84.

- MORLÁNS, Maria Cristina, "Landscape structure (matrix, patches, edges, corridors). Their functions. Fragmentation of the habitat and its edge effect" http://fahuweb.uncoma.edu.ar/archivos/ESTRUCTURA_DEL_PAISAJE.pdf, [accessed: 13/02/2014].

- LYNCH, Kevin, La imagen de la ciudad, Barcelona, Gustavo Gili, 1984,1998, [Cambridge, MIT Press (ed.)1960] p 86.

- CARRILLO, Francisco Javier, "Capital Cities: A taxonomy of capital accounts for knowledge cities", in The Journal of Knowledge Management. Vol.8, nº5, October 2004 pp 28-60.

- CARRILLO, Francisco Javier, "Capital Cities: A taxonomy of capital accounts for knowledge cities", in The Journal of Knowledge Management. Vol.8, nº5, October 2004 pp 28-60.

- UYTERHOEVEN, Hugo, "Is Economic Expansion a Necessary Condition for the Civilisation of Leisure? La civilización del ocio. Cultura moral, economía, sociología: Encuesta sobre el mundo del futuro, Madrid, 1968, p. 146.

- THORSBY, David, "Economy and Culture". Cambridge University Press, Madrid, 2001 p 58.

- CARRILLO, Francisco Javier, "Ciudades del conocimiento: El estado del arte y el espacio de posibilidades", in La innovación en la sociedad del conocimiento: Retos y oportunidades para los países iberoamericanos. Medellín, Colombia, 29 October 2004 pp 28-60.

- CAPRA, Fritjof, "The web of life. A new perspective on living systems". Anagrama, Barcelona, 1998 p 60.

- CARRILLO, Francisco Javier, "Ciudades del conocimiento: El estado del arte y el espacio de posibilidades", in La innovación en la sociedad del conocimiento: Retos y oportunidades para los países iberoamericanos. Medellín, Colombia, 29 October 2004 pp 28-60.

- CARRILLO, Francisco Javier, "Ciudades del conocimiento: El estado del arte y el espacio de posibilidades", in La innovación en la sociedad del conocimiento: Retos y oportunidades para los países iberoamericanos. Medellín, Colombia, 29 October 2004 pp 28-60.

- MAGNANO, Vittorio, "Modernità e durata. Proposte per una teoria del progetto", Skira, Milano, 1999, pp. 52-53.

- GAMBINO, Roberto, "Maniere di intendere il paesaggio", in Clementi, A. Interpretazioni di paesaggio, Meltemi editore, Roma, 2002, pp. 54-72.

- BERNARD, P. "La cohésion sociale: Critique d'un quasi-concept", in Lien social et Politiques RIAC, nº 41, 1999 pp 47-59.

- OTTONE, Ernesto (Dir.), SOJO, Ana (Coord.), "Cohesión social: Inclusión y sentido de pertenencia en América Latina y el Caribe", Naciones Unidas, Santiago de Chile, 2007 p 15.

- OTTONE, Ernesto (Dir.), SOJO, Ana (Coord.), "Cohesión social: Inclusión y sentido de pertenencia en América Latina y el Caribe", Naciones Unidas, Santiago de Chile, 2007 p 15.

- CEPAL, "Cohesión social: Inclusión y sentido de pertenencia en América Latina y el Caribe", Naciones Unidas, Santiago de Chile, 2007 p 14.

- OTTONE, Ernesto (Dir.), SOJO, Ana (Coord.), "Cohesión social: Inclusión y sentido de pertenencia en América Latina y el Caribe", Naciones Unidas, Santiago de Chile, 2007 p 15.

- RIMEZ, Marc, "OCO - URB-AL III, Talleres de Cohesión Social - ¿Cómo valorar los aportes de los aportes de los proyectos al programa URB-AL III".

- COSER, L.A. “The Functions of Social Conflict”, Free Press, Nueva York, 1956.

- GLUCKMAN, M. “Custom and Conflict in Africa”, Blackwell, Oxford, 1955.

- CAPLOW, T. “Further Development of the Theory of Coalitions in the Triad”, in The American Journal of Sociology, nº 64, 1959, 488-493.

- SCHELLING, T. “the Strategy of Conflict”, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachussets, 1960.

- BOULDING, K. “Conflict and Defence: A General Theory”, Harper and Bros. Nueva York, 1962.

- COLLINS, R. “Conflict Sociology. Toward an Explanatory Science”, Academic Press, Nueva York, 1975.

- KRIESBERG, L. “Sociología de los conflictos sociales”, Trillas, México, 1975.

- LAZZERETTI, Luziana,“El distrito cultural”, in Mediterráneo economic: Los distritos industriales, Fundación Cajamar, 2008, p 330.

- ORDUNA, "Identidad e identidades: Potencialidades para la cohesión social y territorial", in Colección de estudios sobre políticas públicas locales y regionales de cohesión social, Programa URB-AL III, Barcelona, 2012, p 15.

- CARRILLO, Francisco Javier, “Capital Cities: A taxonomy of capital accounts for knowledge cities”, en The Journal of Knowledge Management. Vol.8, nº5, octubre de 2004, pp 28-60.

- CARRILLO, Francisco Javier, “Ciudades del conocimiento: El estado del arte y el espacio de posibilidades”, en La innovación en la sociedad del conocimiento: Retos y oportunidades para los países iberoamericanos. Medellín, Colombia, 29 de octubre de 2004.

- CARRILLO, Francisco Javier, “Capital Cities: A taxonomy of capital accounts for knowledge cities”, en The Journal of Knowledge Management. Vol.8, nº5, octubre de 2004, pp 28-60.

- EDVINSSON, Leif, MALONE, Michael S. “Intellectual Capital: Realizing your company´s true value by finding its hidden roots”, Harper Bussiness, USA, 1997.

- GAROFOLI, Gioacchino, “Desarrollo económico, organización de la producción y territorio”, in Desarrollo económico local en Europa, A. Vázquez-Barquero y G. Garofoli (eds.), Colegio de Economistas de Madrid, 1995.

- AGUDO, Jorge, “Paisaje y gestión del territorio”, in Revista Jurídica de la Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, nº 15, pp198-237.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).