Submitted:

16 April 2024

Posted:

16 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Measures

3. Results

3.1. Statistical Analysis

3.2. Preliminary Analysis

3.3. Predictors of Psychological Well-Being

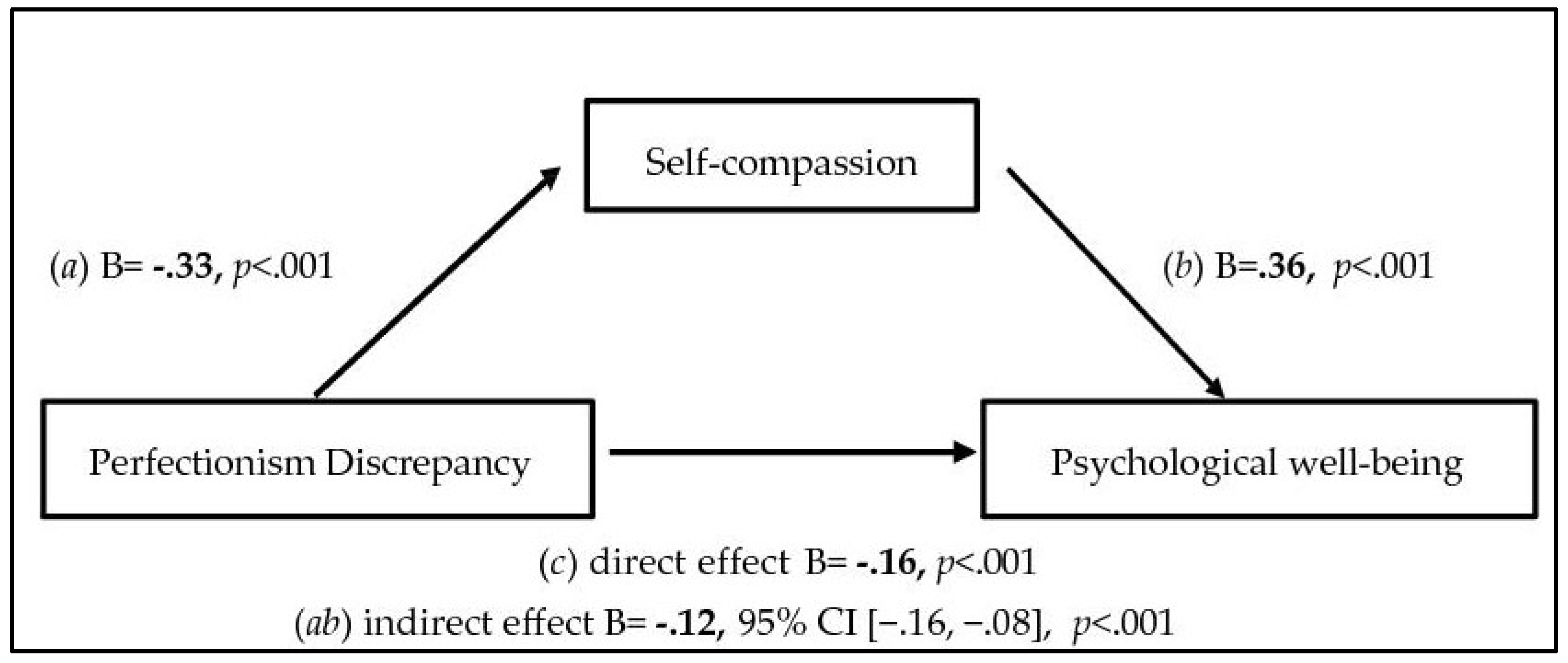

3.4. Mediational Model

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bardone-Cone, A.M.; Wonderlich, S.A.; Frost, R.O.; Bulik, C.M.; Uppala, S.; Simonich, H. Perfectionism and eating disorders: Current status and future directions. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2007, 27, 384–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flett, G. L.; Hewitt, P. L. Reflections on three decades of research on multidimensional perfectionism: An introduction to the special issue on further advances in the assessment of perfectionism. J. Psychoed. Assess. 2020, 38, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, R.O.; Marten, P.; Lahart, C.M.; Rosenblate, R. The dimensions of perfectionism. Cogn. Ther. Res. 1990, 14, 449–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flett, G. L.; Hewitt, P. L. Perfectionism and maladjustment: An overview of theoretical, definitional, and treatment issues. In Perfectionism: Theory, research, and treatment; Flett, G.L., Hewitt, P.L., Eds.; American Psychological Association, 2002; pp. 5–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirois, F. M.; Molnar, D. S.; Hirsch, J. K. A meta-analytic and conceptual update on the associations between procrastination and multidimensional perfectionism. EJP 2017, 31, 137–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamacheck, E. Psycodynamics of normal and neurotic perfectionism. Psychol., 1978, 15, 27–33. [Google Scholar]

- Pacht A., R. Reflections on perfection. Am. Psychol. 1984, 39, 386–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoeber, J.; Otto, K. Positive Conceptions of Perfectionism: Approaches, Evidence, Challenges. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2006, 10, 295–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoeber, J.; Rennert, D. Perfectionism in School Teachers: Relations with Stress Appraisals, Coping Styles, and Burnout. Anxiety, Stress Coping 2008, 21, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hewitt, P. L.; Flett, G. L. Perfectionism in the self and social contexts: Conceptualization, assessment, and association with psychopathology. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev 1991, 60, 456–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.M.; Hewitt, P.L.; Sherry, S.B.; Flett, G.L.; Ray, C. Parenting behaviors and trait perfectionism: A meta-analytic test of the social expectations and social learning models. J. Res. Pers. 2022, 96, 104180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slaney, R. B.; Rice, K. G.; Mobley, M.; Trippi, J.; Ashby, J. S. The Revised Almost Perfect Scale. Meas. Ev. Couns. Dev. 2001, 34, 130–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limburg, K.; Watson, H.J.; Hagger, M.S.; Egan, S.J. The relationship between perfectionism and psychopathology: a meta-analysis. J. Clin. Psychol. 2017, 73, 1301–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patterson, H.; Firebaugh, C. M.; Zolnikov, T. R.; Wardlow, R.; Morgan, S. M.; Gordon, B. A Systematic Review on the Psychological Effects of Perfectionism and Accompanying Treatment. Psychol. 2021, 12, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, A.T.; Cabaços, C.; Araújo, A.; Amaral, A.P.; Carvalho, F.; Macedo, A. COVID-19 psychological impact: The role of perfectionism. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2022, 184, 111160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chufar, B.M.; Pettijohn II, T.F. Meeting high standards: the effect of perfectionism on task performance, self-esteem, and self-efficacy in college students. Psychol. Behav. Sci. 2013, 2, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.; Heo, C.; Kim, J. S.; Rice, K. G.; Kim, Y. H. How does perfectionism affect academic achievement? Examining the mediating role of accurate self-assessment. Int. J. Psychol. 2020, 55, 936–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badri, S.K.Z.; Kong, M.Y.; Wan Mohd Yunus, W.M.A.; Nordin, N.A.; Yap, W.M. Trait emotional intelligence and happiness of young adults: The mediating role of perfectionism. IJERPH 2021, 18, 10800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suh, H.; Gnilka, P. B.; Rice, K. G. Perfectionism and well-being: A positive psychology framework. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2017, 111, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M. M.; Saklofske, D. H.; Yan, G. Perfectionism, trait emotional intelligence, and psychological outcomes. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2015, 85, 155–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, K. G.; Ashby, J. S.; Slaney, R. B. Self-esteem as a mediator between perfectionism and depression: A structural equations analysis. J. Couns. Psychol. 1998, 45, 304–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besser, A.; Flett, G.L.; Hewitt, P.L. Perfectionistic Self-Presentation and Trait Perfectionism in Social Problem-Solving Ability and Depressive Symptoms. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 40, 2121–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoeber, J.; Lalova, A. V.; Lumley, E. J. Perfectionism, (self-)compassion, and subjective well-being: A mediation model. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2020, 154, 109708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, K. Self-compassion: An alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self Identity, 2003, 2, 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehr, K.E.; Adams, A.C. Self-Compassion as a Mediator of Maladaptive Perfectionism and Depressive Symptoms in College Students. J. Coll. Stud. Psych. 2016, 30, 132–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, M.; Yap, K.; Scott, N.; Einstein, D. A.; Ciarrochi, J. Self-Compassion Moderates the Perfectionism and Depression Link in Both Adolescence and Adulthood. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0192022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tobin, R.; Dunkley, D. M. Self-critical perfectionism and lower mindfulness and self-compassion predict anxious and depressive symptoms over two years. Behav. Res. Ther. 2021, 136, Article–103780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryff, C. D. Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 57, 1069–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C. D.; Singer, B. H. Know thyself and become what you are: A eudaimonic approach to psychological well-being. J. Happiness Stud. 2008, 9, 13–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosewich, A.D.; Kowalski, K.C.; Sabiston, C.M.; Sedgwick, W.A. Self-Compassion: A potential resource for young women athletes. JSEP 2011, 33, 103–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Li, L.; Shi, J.; Liang, H.; Yang, X. Self-compassion mediates the perfectionism and depression link on Chinese undergraduates. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2021, 10, 1950–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahin, E.E. Self-Compassion as a Mediator Between Perfectionism and Life-Satisfaction Among University Students. IJPE 2021, 17, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippello, P.; Sorrenti, L.; Buzzai, C.; Costa, S. The Almost Perfect Scale-Revised: An Italian adaptation. GIP 2016, 43, 911–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, K.D. The development and validation of a scale to measure self-Compassion. Self Identity 2003, 2, 223–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veneziani, C. A.; Fuochi, G.; Voci, A. Self-compassion as a healthy attitude toward the self: Factorial and construct validity in an Italian sample. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2017, 119, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C. D.; Keyes, C. L. M. The structure of psychological well-being revisited. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 69, 719–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruini, C.; Ottolini, F.; Rafanelli, C.; Ryff, C.; Fava, G. A. La validazione italiana delle Psychological Well-being Scales (PWB) [Italian validation of Psychological Well-being Scales (PWB)]. Riv. Psichiatr. 2003, 38, 117–130. [Google Scholar]

- Dahlenburg, S.C.; Gleaves, D.H.; Hutchinson, A.D. Anorexia nervosa and perfectionism: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Eat. Dis. 2019, 52, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Zhao, X.; Liu, W. Are Perfectionists Always Dissatisfied with Life? An Empirical Study from the Perspective of Self-Determination Theory and Perceived Control. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawamoto, A.; Sheth, R.; Yang, M.; Demps, LT.; Sevig, T. The Role of Self-Compassion Among Adaptive and Maladaptive Perfectionists in University Students. Couns. Psychol. 2023, 51, 113–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De-Juanas, Á.; Bernal Romero, T.; Going, R. The Relationship Between Psychological Well-Being and Autonomy in Young People According to Age. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 559976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhang, X.; Lin, X.; Sun, Y.; Wang, N.; Wang, J.; Luo, F. The Relationship between Perfectionism and Social Anxiety: A Moderated Mediation Model. IJERPH 2022, 19, 12934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Huang, Y.; Xiao, Y. The Mediating Effect of Social Problem-Solving Between Perfectionism and Subjective Well-Being. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 764976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoeber, J.; Harris, R. A.; Moon, P. S. Perfectionism and the experience of pride, shame, and guilt: Comparing healthy perfectionists, unhealthy perfectionists, and nonperfectionists. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2007, 43, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, R. W.; Huelsman, T. J.; Araujo, G. Perfectionistic concerns suppress associations between perfectionistic strivings and positive life outcomes. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2010, 48, 584–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudreau, P.; Thompson, A. Testing a 2×2 model of dispositional perfectionism. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2010, 48, 532–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H. J.; Jeong, D. Y. Psychological Well-Being, Life Satisfaction, and Self-Esteem among Adaptive Perfectionists, Maladaptive Perfectionists, and Nonperfectionists. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2015, 72, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, T.A.; Koestner, R.; Zuroff, D.C.; Milyavskaya, M.; Gorin, A.A. The effects of self-criticism and self-oriented perfectionism on goal pursuit. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2011, 37, 964–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neff, K. Self-Compassion, Self-Esteem, and Well-Being. Soc. Pers. Psychol. Compass. 2011, 5, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zessin, U.; Dickhäuser, O.; Garbade, S. The Relationship Between Self-Compassion and Well-Being: A Meta-Analysis. AP:HWB 2015, 7, 340–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leary, M. R.; Tate, E. B.; Adams, C. E.; Batts Allen, A.; Hancock, J. Self-compassion and reactions to unpleasant self-relevant events: the implications of treating oneself kindly. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 92, 887–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, C.W.; Lee, E.B.; Petersen, J.M.; Levin, M.E.; Twohig, MP. Is perfectionism always unhealthy? Examining the moderating effects of psychological flexibility and self-compassion. J. Clin. Psychol. 2021, 77, 2576–2591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koutra, K.; Mouatsou, C.; Psoma, S. The Influence of Positive and Negative Aspects of Perfectionism on Psychological Distress in Emerging Adulthood: Exploring the Mediating Role of Self-Compassion. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wegerer, M. Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment of Perfectionism: An Overview of the State of Research and Practical Therapeutical Procedures. Verhaltenstherapie 2024, 34, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, T.; Hill, A. P. Young people’s perceptions of their parents’ expectations and criticism are increasing over time: Implications for perfectionism. Psychol. Bull. 2022, 148, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domocus, I.; Damian, L.E. The role of parents and teachers in changing adolescents' perfectionism: A short-term longitudinal study. Pers. Individ. Diff. 2018, 131, 244–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, P.-E.; Dundas, I.; Stige, S.H.; Hjeltnes, A.; Woodfin, V.; Moltu, C. Becoming aware of inner self-critique and kinder toward self: A qualitative study of experiences of outcome after a brief self-compassion intervention for university level students. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James, K.; Rimes, K.A. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy versus pure cognitive behavioural self-help for perfectionism: A pilot randomised study. Mindfulness, 2018, 9, 801–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodfin, V.; Molde, H.; Dundas, I.; Binder, P.E. A randomized control trial of a brief self-compassion intervention for perfectionism, anxiety, depression, and body image. Front. Psychol. 2021, 9, 751294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| APS 1. High Standards |

5.33 | 0.80 | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| 2. Discrepancy | 4.07 | 1.34 | .01 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| 3. Order | 5.24 | 0.95 | .30** | .07 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| SCS 4. Self-Kindness |

3.07 | 0.90 | -.05 | -.47** | -.09 | 1 | |||||||||||

| 5. Self-Judgment | 2.90 | 0.94 | -.05 | -.63** | .00 | .13* | 1 | ||||||||||

| 6. Common Humanity | 3.22 | 0.89 | -.03 | -.29** | -.07 | .61** | .03 | 1 | |||||||||

| 7. Isolation | 2.89 | 1.06 | .10 | -.63** | -.03 | .15** | .71** | .08 | 1 | ||||||||

| 8. Mindfulness | 3.28 | 0.86 | .10 | -.33** | -.13 | .67** | .12* | .56** | .17** | 1 | |||||||

| 9. Over-identification | 2.86 | 1.04 | .12 | -.66** | -.07 | .09 | .76** | .01 | .76** | .12* | 1 | ||||||

| PWS 10. Positive relations |

4.14 | 0.90 | .06 | -.40** | .06 | .30** | .09 | .23** | .09 | .22** | .10 | 1 | |||||

| 11. Self-acceptance | 3.90 | 1.00 | .18** | -.69** | .03 | .63** | .16** | .49** | .12* | .53** | .14* | .47** | 1 | ||||

| 12. Purpose in life | 4.15 | 0.94 | .29** | -.63** | .05 | .46** | .17** | .36** | .17** | .45** | .18** | .53** | .82** | 1 | |||

| 13. Autonomy | 4.28 | 0.80 | .11 | -.37** | .01 | .28** | .03 | .24** | .04 | .28** | .03 | .34** | .46** | .44** | 1 | ||

| 14. Enviromental | 3.91 | 0.60 | .29** | -.53** | .19** | .46** | .11* | .36** | .08 | .42** | .10 | .45** | .74** | .70** | .45** | 1 | |

| 15. Personal growth | 4.78 | 0.70 | 17* | -.41** | .04 | .37** | .05 | .40** | .02 | .32** | .03 | .50** | .60** | .60** | .52** | .55** | 1 |

| Model | Unstandardised Coefficients |

Standardised Coefficients |

95% Confidence Interval for B |

|||||

| B | SE | β | t | Sig. | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | ||

| 1 | (Costant) | 5.24 | .09 | 59.66 | ‹.001 | 5.06 | 5.41 | |

| ALMOST – Discrepancy | -.28 | .02 | -.68 | -13.64 | ‹.001 | -.32 | -.24 | |

| 2 | (Costant) | 4.39 | .19 | 22.99 | ‹.001 | 4.01 | 4.77 | |

| ALMOST – Discrepancy | -.28 | .02 | -.68 | -14.42 | ‹.001 | -.32 | -.24 | |

| ALMOST – High Standard |

.16 | .03 | .23 | 4.92 | ‹.001 | .10 | .22 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).