Submitted:

17 April 2024

Posted:

17 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Application

2.2. Patient Selection

2.3. Date Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

References

- Ogle, O.E. and L.R. Halpern, Odontogenic Infections: Anatomy, Etiology, and Treatment. Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Medicine, and Pathology for the Clinician, 2023: p. 227-241.

- Ogle, O.E., Odontogenic infections. Dental Clinics, 2017. 61(2): p. 235-252.

- Islam, B., S.N. Khan, and A.U. Khan, Dental caries: from infection to prevention. Medical Science Monitor, 2007. 13(11): p. RA196-RA203.

- Prakash, S.K., Dental abscess: A microbiological review. Dental research journal, 2013. 10(5): p. 585.

- López-Píriz, R., L. Aguilar, and M.J. Giménez, Management of odontogenic infection of pulpal and periodontal origin. Medicina Oral, Patología Oral y Cirugía Bucal (Internet), 2007. 12(2): p. 154-159.

- Rastenienė, R.; Pūrienė, A.; Aleksejūnienė, J.; Pečiulienė, V.; Zaleckas, L. Odontogenic Maxillofacial Infections: A Ten-Year Retrospective Analysis. Surg. Infect. 2015, 16, 305–312, . [CrossRef]

- Nadig, K.; Taylor, N.G. Management of odontogenic infection at a district general hospital. Br. Dent. J. 2018, 224, 962–966, . [CrossRef]

- Bowe, C.M.; O’neill, M.A.; O’connell, J.E.; Kearns, G.J. The surgical management of severe dentofacial infections (DFI)—a prospective study. Ir. J. Med Sci. (1971 -) 2018, 188, 327–331, . [CrossRef]

- Allareddy, V., et al., Hospitalizations primarily attributed to dental conditions in the United States in 2008. Oral surgery, oral medicine, oral pathology and oral radiology, 2012. 114(3): p. 333-337.

- Neal, T.W.; Schlieve, T. Complications of Severe Odontogenic Infections: A Review. Biology 2022, 11, 1784, . [CrossRef]

- Ullah, M.; Irshad, M.; Yaacoub, A.; Carter, E.; Thorpe, A.; Zoellner, H.; Cox, S. Dental Infection Requiring Hospitalisation Is a Public Health Problem in Australia: A Systematic Review Demonstrating an Urgent Need for Published Data. Dent. J. 2023, 11, 97, . [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Liau, I.; Bayetto, K.; May, B.; Goss, A.; Sambrook, P.; Cheng, A. The financial burden of acute odontogenic infections: the South Australian experience. Aust. Dent. J. 2019, 65, 39–45, . [CrossRef]

- Neal, T.W.; Hammad, Y.; Carr, B.R.; Schlieve, T. The Cost of Surgically Treated Severe Odontogenic Infections: A Retrospective Study Using Severity Scores. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2022, 80, 897–901, . [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir, D. Dental Caries : The Most Common Disease Worldwide and Preventive Strategies. Int. J. Biol. 2013, 5, p55, . [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.; Chambers, I. Dental emergencies presenting to a general hospital emergency department in Hobart, Australia. Aust. Dent. J. 2014, 59, 329–333, . [CrossRef]

- Biggs, A., Overview of Commonwealth involvement in funding dental care. 2008.

- Fu, B.; McGowan, K.; Sun, H.; Batstone, M. Increasing Use of Intensive Care Unit for Odontogenic Infection Over One Decade: Incidence and Predictors. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2018, 76, 2340–2347, . [CrossRef]

- Michael, J.A.; Hibbert, S.A. Presentation and management of facial swellings of odontogenic origin in children. Eur. Arch. Paediatr. Dent. 2014, 15, 259–268, . [CrossRef]

- Cope, A.L.; Chestnutt, I.G.; Wood, F.; A Francis, N. Dental consultations in UK general practice and antibiotic prescribing rates: a retrospective cohort study. Br. J. Gen. Pr. 2016, 66, e329–e336, . [CrossRef]

- Liau, I.; Han, J.; Bayetto, K.; May, B.; Goss, A.; Sambrook, P.; Cheng, A. Antibiotic resistance in severe odontogenic infections of the South Australian population: a 9-year retrospective audit. Aust. Dent. J. 2018, 63, 187–192, . [CrossRef]

- Sundararajan, K., et al., Morbidity and mortality in patients admitted with submandibular space infections to the intensive care unit. Anaesthesia & Intensive Care, 2015. 43(3): p. 420-2.

- Fehrenbach, M.J. and S.W. Herring, Spread of dental infection. Practical Hygiene, 1997. 6: p. 13-19.

- Mathew, G.C.; Ranganathan, L.K.; Gandhi, S.; Jacob, M.E.; Singh, I.; Solanki, M.; Bither, S. Odontogenic maxillofacial space infections at a tertiary care center in North India: a five-year retrospective study. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2012, 16, e296–e302, . [CrossRef]

- Robertson, D.P.; Keys, W.; Rautemaa-Richardson, R.; Burns, R.; Smith, A.J. Management of severe acute dental infections. BMJ 2015, 350, h1300–h1300, . [CrossRef]

- Bridgeman, A.; Wiesenfeld, D.; Hellyar, A.; Sheldon, W. Major maxillofacial infections. An evaluation of 107 cases. Aust. Dent. J. 1995, 40, 281–288, . [CrossRef]

- Fu, B.; McGowan, K.; Sun, J.; Batstone, M. Increasing frequency and severity of odontogenic infection requiring hospital admission and surgical management. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2020, 58, 409–415, . [CrossRef]

- Uluibau, I.; Jaunay, T.; Goss, A. Severe odontogenic infections. Aust. Dent. J. 2005, 50, S74–S81, . [CrossRef]

- Kisely, S.; Baghaie, H.; Lalloo, R.; Siskind, D.; Johnson, N.W. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Association Between Poor Oral Health and Severe Mental Illness. Psychosom. Med. 2015, 77, 83–92, doi:10.1097/psy.0000000000000135.

- Kusumoto, J.; Iwata, E.; Huang, W.; Takata, N.; Tachibana, A.; Akashi, M. Hematologic and inflammatory parameters for determining severity of odontogenic infections at admission: a retrospective study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, 1–11, . [CrossRef]

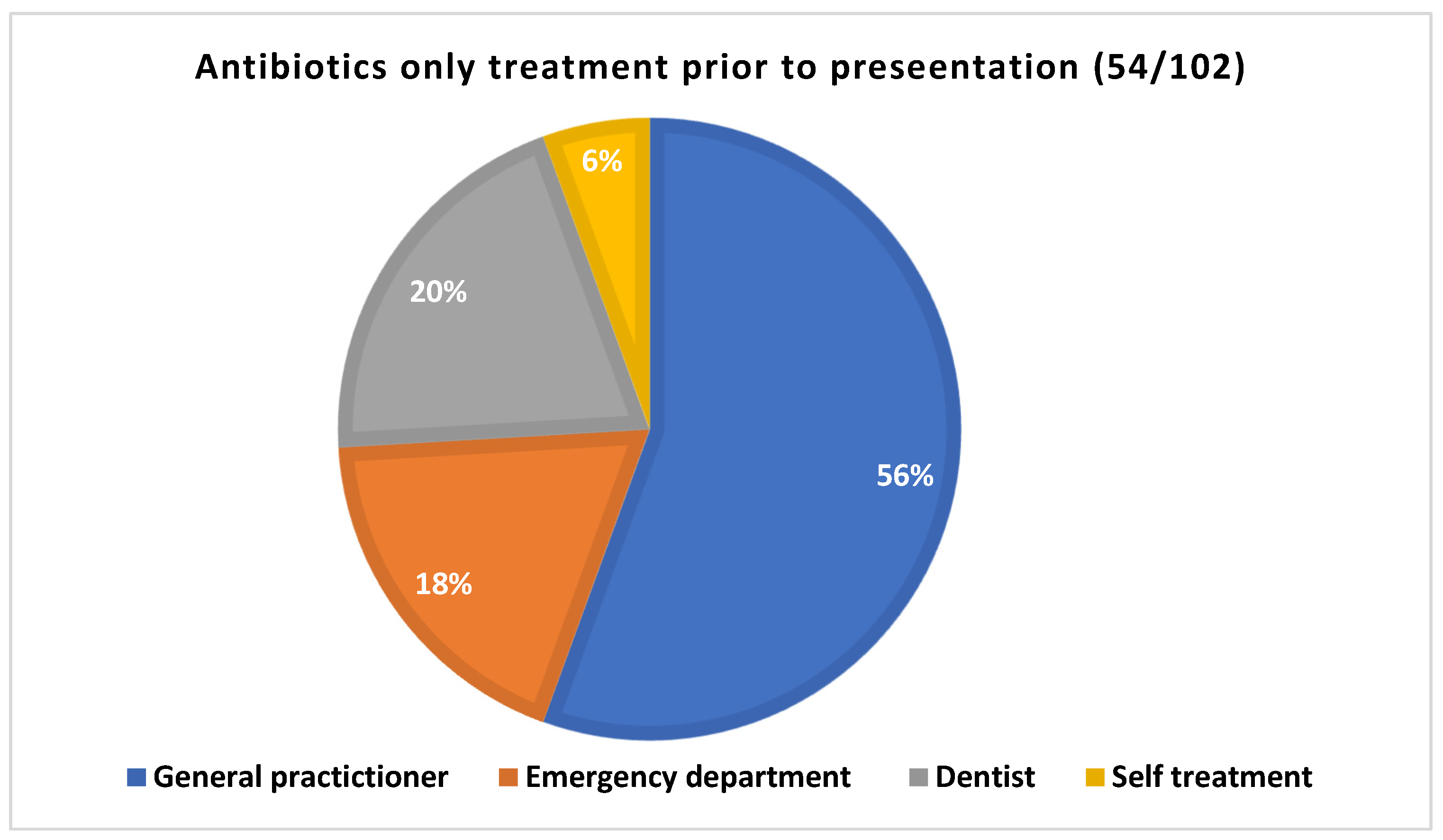

| Previous treatment | 68 (66.7%) | |

| Antibiotics only | 54 (52.9%) | |

|

Time of prescription (n=51) |

More than a week | 11 |

| Less than a week | 40 | |

| Two or more than two prescriptions | 11 | |

| Dental treatment | Extractions +/- Antibiotics | 12 |

| Pulp extirpations +/- Antibiotics | 8 | |

|

Type of antibiotics prescribed prior to presentations (Multiple prescriptions were reported in 11 cases) |

Augmentin | 19 |

| Augmentin plus metronidazole | 1 | |

| Amoxicillin | 15 | |

| Amoxicillin plus Metronidazole | 5 | |

| Keflex | 2 | |

| Cephalexin | 1 | |

| Cephalexin plus metronidazole | 1 | |

| Clindamycin | 1 | |

| Clindamycin plus metronidazole | 1 | |

| Flucloxacillin plus metronidazole | 1 | |

| metronidazole | 1 | |

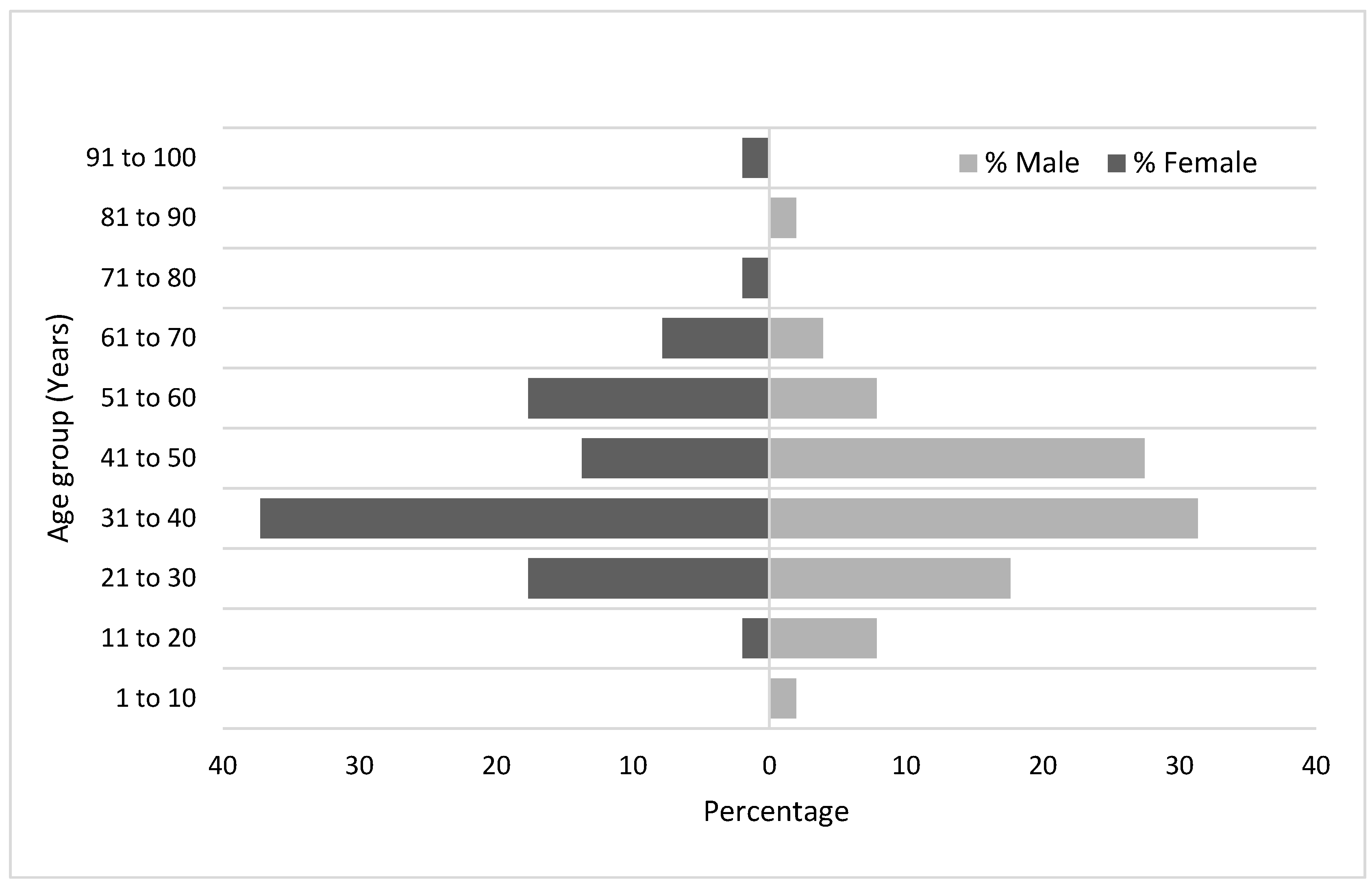

| Gender | M | 51 (50%) |

| F | 51 (50%) | |

| Age (Years) | Mean | 40.14 |

| Median | 37.5 | |

| Range | 6 to 93 | |

| Country of Birth | Australia | 84 (82.35 %) |

| Overseas | 18 (17.65 %) | |

| Aboriginality status | Aboriginal or Torres straits islanders | 7 (6.86 %) |

| Smoking status | Smokers | 53 (51.96 %) |

| Non-smokers | 49 (48.04 %) | |

| Smoking Frequency (cigarette per day) | Mean | 3-30 |

| Range | 13.62 | |

| Co-morbidity (n=52) | Mental Health Issues | 25 (34.2%) |

| Drug Use | 17 (23.3%) | |

| Allergy to penicillin | 10 (13.7%) | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 5 (6.8%) | |

| Hepatitis C | 4 (5.5%) | |

| Cancer | 2 (2.7%) | |

| Fatty liver | 2 (2.7%) | |

| Myocardial infarction | 1 (1.7%) | |

| Cardiomyopathy | 1 (1.7%) | |

| COPD | 1 (1.7%) | |

| Epilepsy | 1 (1.7%) | |

| Osteoporosis | 1 (1.7%) | |

| Crohn’s disease | 1 (1.7%) | |

| Heavy alcohol | 1 (1.7%) | |

| Hypothyroid | 1 (1.7%) | |

| BMI (n=89) | Mean | 29.9 |

| Median | 29.14 | |

| Range | 16.59 to 75.99 |

| Pain (n=102) | 101 (99 %) | |

| Facial Swelling (n=102) | 102 (100 %) | |

| Trismus (n=102) | 41 (40.2 %) | |

| Dysphagia (n=102) | 28 (27.4 %) | |

| Respiratory rate (n=86) (Number of breathings pre minute) |

Mean | 18.49 |

| Median | 18 | |

| Range | 14-31 | |

| >20 | 8 | |

| Oxygen Saturation (%) (n=100) | Mean | 97.6 |

| Median | 98 | |

| Range | 95-100 | |

| Pulse Rate (n=101) | Mean | 91.16 |

| Median | 89 | |

| Range | 61-165 | |

| >100 | 25 | |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) (n=96) |

Mean | 132.51 |

| Median | 130 | |

| Range | 102-189 | |

| >140 | 28 | |

| Diastolic blood pressure (n=95) (mm Hg) | Mean | 81.97 |

| Median | 82 | |

| Range | 52-114 | |

| >90 | 13 | |

| Mean Arterial pressure (n=94) ) (mm Hg) | Mean | 97.65 |

| Median | 98 | |

| Range | 39.4-125 | |

| >100 | 39 | |

| Temperature (°C) (n=100) | Mean | 36.64 |

| Median | 36.6 | |

| Range | 35.5-39.2 | |

| 37.1-38 | 18 | |

| >38 | 3 | |

| Random blood sugar level (mmol/L) Nondiabetic patients (n=62) |

Mean | 5.27 |

| Median | 5.25 | |

| Range | 3.7-7.2 | |

| Random blood sugar level (mmol/L) Diabetic patients (n=4) |

Mean | 15.7 |

| Median | 17.15 | |

| Range | 5-23.5 | |

|

1 space (n=37) (36%) |

Buccal | 27 | |||||

| Canine | 8 | ||||||

| Sub-masseteric | 1 | ||||||

| Lower lip | 1 | ||||||

| 2 spaces (n=40) (39%) | Buccal | Submandibular | 11 | ||||

| Buccal | Canine | 8 | |||||

| Buccal | Maxillary sinus | 7 | |||||

| Canine | Upper lip | 3 | |||||

| Canine | Orbital | 3 | |||||

| Buccal | Masticator | 2 | |||||

| Buccal | Palatal | 1 | |||||

| Buccal | Sublingual | 1 | |||||

| Buccal | sub masseteric | 1 | |||||

| Submandibular | Submental | 1 | |||||

| Submandibular | Masticator | 1 | |||||

| Submental | Lower lip | 1 | |||||

|

3 spaces (n=21) (21%) |

Canine | Buccal | Maxillary sinus | 4 | |||

| Canine | Buccal | Upper lip | 4 | ||||

| Buccal | Submandibular | Masticator | 2 | ||||

| Submandibular | Masticator | Pharyngeal | 2 | ||||

| Buccal | Sub-masseteric | Pharyngeal | 1 | ||||

| Buccal | Sub-masseteric | Submandibular | 1 | ||||

| Buccal | Sub-masseteric | Masticator | 1 | ||||

| Buccal | Sub-masseteric | Maxillary sinus | 1 | ||||

| Buccal | Sublingual | Submandibular | 1 | ||||

| Buccal | Sublingual | Submental | 1 | ||||

| Buccal | Maxillary sinus | Orbital | 1 | ||||

| Buccal | Canine | Orbital | 1 | ||||

| Sublingual | Submandibular | Masticator | 1 | ||||

| ≥ 4 spaces (n=4) (4%) | Buccal | Sublingual | Submandibular | Pharyngeal | 1 | ||

| Sublingual* | Submandibular* | Submental | Sub-masseteric | 1 | |||

| Canine | Buccal space | Maxillary sinus | Orbital | 1 | |||

| Buccal | Submandibular | Masticator | Pharyngeal | 1 | |||

| Total | 102 | ||||||

| Aetiology (n=102) | Dental caries (n=64) | Un-restored caries | 46 (45.5%) |

| Retained roots caries | 14 (13.9%) | ||

| Restored caries | 3 (3%) | ||

| Periapical cyst | 1 (1%) | ||

| Periodontal origin (n=10) | Pericoronitis | 6 (5.9%) | |

| Periodontal abscess | 4 (4%) | ||

| Post extraction | 13 (12.9%) | ||

| Post pulp extirpation | 8 (7.9%) | ||

| Failed root canal treatment | 4 (4%) | ||

| Occlusal wear | 2 (2%) | ||

| Tooth fracture | 1 (1%) | ||

| Jaw Involvement | Upper jaw (Maxilla) | 49 (48%) | |

| Lower jaw (Mandible) | 53 (52%) | ||

| Jaw side involvement | Right | 50 (49%) | |

| Left | 52 (51%) | ||

|

Teeth involvement (Some cases had multiple teeth involved) |

Anterior teeth | Incisor teeth | 19 (15.6%) |

| Canine teeth | 13 (10.6%) | ||

| Premolar teeth | 39 (32%) | ||

| 1st and 2nd molar teeth | 38 (31.1%) | ||

| 3rd molar teeth | 12 (9.8%) | ||

| Deciduous teeth | 1 (0.8 %) | ||

| Investigations | White blood cell count (n=91) (Valuex109/L) |

Mean | 11.16 |

| Median | 11.2 | ||

| Range | 1.5-20.8 | ||

| Less than 4 | 1 | ||

| 4 to 11 | 43 | ||

| More than 11 | 47 | ||

| C-reactive protein (n=73) (mg/L) | Mean | 47.71 | |

| Median | 35 | ||

| Range | 3-186 | ||

| 3 to 10 | 16 | ||

| More than 100 | 8 | ||

| Imaging | Orthopantomogram | 91 (89.2%) | |

| Contrast CT | 75 (73.5%) | ||

| Contrast CT results (n=75) | Inflammatory changes | 75 (100%) | |

| Frank collection | 19 (25.3%) | ||

| Management | Non-surgical management (antibiotics only) | 24 (23.5%) | |

| Surgical management | 78 (76.5%) | ||

| Anaesthesia | LA (Dental facility-NCOH) | 44 (56.4%) | |

| GA (Hospital Facility) | 34 (43.6%) | ||

| Surgical options | Extractions | 63 (61.8%) | |

| Incision and drainage (n=38) (37.2%) |

Intra oral | 33 (32.3%) | |

| Extra oral | 1 (1%) | ||

| Combined | 4 (3.9%) | ||

| Pulp extirpation | 4 (3.9) | ||

| Referral to dentist for extraction or pulp extirpation | 11 (10.8%) | ||

| Intravenous antibiotics (n=102) | Augmentin alone | 71 (69.6%) | |

| Augmentin plus metronidazole | 14 (13.7%) | ||

| Benzylpenicillin plus metronidazole | 4 (3.9%) | ||

| Clindamycin | 3 (2.9%) | ||

| Clindamycin plus metronidazole | 4 (3.9%) | ||

| Metronidazole alone | 1 (1%) | ||

| Ceftriaxone | 1 (1%) | ||

| Bactrim plus metronidazole | 1 (1%) | ||

| Cephazolin | 1 (1%) | ||

| Cephazolin plus metronidazole | 1 (1%) | ||

| Augmentin plus metronidazole, BenPen PICC line | 1 (1%) | ||

| Change of Intravenous antibiotics | 5 | ||

| Consultation with infectious disease specialist | 2 | ||

| Antibiotic on discharge (n=97) |

Augmentin | 77 (79.4%) | |

| Augmentin plus metronidazole | 4 (4.1%) | ||

| Amoxicillin plus metronidazole | 2 (2%) | ||

| Benzylpenicillin plus metronidazole | 2 (2%) | ||

| Clindamycin | 5 (5.1%) | ||

| Clindamycin plus metronidazole | 3 (3.1%) | ||

| Bactrim plus metronidazole | 1 (1%) | ||

| Metronidazole | 1 (1%) | ||

| Keflex | 1 (1%) | ||

| Keflex plus metronidazole | 1 (1%) | ||

| Length of hospital stay (days) | Total days | 271 | |

| Ward days | 256 | ||

| Intensive care unit days | 15 | ||

| Mean | 2.66 | ||

| Median | 2 | ||

| Range | 1-8 | ||

| Microbiological Studies | Swab culture | 31 |

| Blood culture | 1 | |

| PCR | 2 | |

| Culture Growth | No Growth | 12 |

| Growth | 19 | |

|

Microorganisms Isolated |

Normal flora | 12 |

| Streptococcus Milleri group | 4 | |

| Candida | 4 | |

| Staph aureus | 2 | |

| Staph epidermis | 1 | |

| Lactobacilli | 1 | |

| Streptococcus oralis | 1 | |

| Viridin group of streptococci | 1 | |

| Yeast cells | 1 | |

|

Susceptibility test (n=3) |

Staph aureus | 2 |

| Strep Milleri group | 1 | |

| Resistance to penicillin | 2 | |

|

Gram staining (n=14) |

G+ve polymorphs | 14 |

| G+ve Cocci | 10 | |

| G+ve Rods | 5 | |

| G-ve Rods | 1 | |

| Complications | Airway related complications | 5 |

| Eye related complication (blurred vision, Diplopia) | 1 | |

| Osteomyelitis | 1 | |

| Severe hypotension | 1 | |

| Hardware infection | 1 | |

| Mortality | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).