Submitted:

17 April 2024

Posted:

17 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Preparation and Characterization of Bemotrizinol Loaded Nanostructured Lipid Carriers (NLC)

2.3. Preparation of O/W Emulsions

2.4. Stability Tests on O/W Emulsions

2.5. Spreadability

2.6. Occlusion Factor

2.7. Viscosity

2.8. In Vitro Release of Bemotrizinol

2.9. Determination of In Vitro Sun Protection Factor (SPF)

2.10. Sensory Evaluation

2.11. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sikora, E. Cosmetic Emulsions. Krakow 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gold, M.H.; Nestor, M.S. A Supersaturated Oxygen Emulsion for Wound Care and Skin Rejuvenation. J Drugs Dermatol 2020, 19, 250–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campanholi, K. da S.S.; da Silva, J.B.; Batistela, V.R.; Gonçalves, R.S.; Said dos Santos, R.; Balbinot, R.B.; Lazarin-Bidóia, D.; Bruschi, M.L.; Nakamura, T.U.; Nakamura, C.V.; et al. Design and Optimization of Stimuli-Responsive Emulsion-Filled Gel for Topical Delivery of Copaiba Oil-Resin. J Pharm Sci 2022, 111, 287–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Shang, Y.; Zeng, X. Study on the Development of Wax Emulsion with Liquid Crystal Structure and Its Moisturizing and Frictional Interactions with Skin. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 2018, 171, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyja, R.; Jankowski, A. The Effect of Additives on Release and in Vitro Skin Retention of Flavonoids from Emulsion and Gel Semisolid Formulations. Int J Cosmet Sci 2017, 39, 442–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Zou, H.; Wang, R.; Zhang, Z.; Qiu, S. Salt of Organosilicon Framework as a Novel Emulsifier for Various Water–Oil Biphasic Systems and a Catalyst for Dibromination of Olefins in an Aqueous Medium. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2021, 13, 33693–33703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Hu, Q.; Li, X.; Ma, C. Systematic Comparison of Structural and Lipid Oxidation in Oil-in-water and Water-in-oil Biphasic Emulgels: Effect of Emulsion Type, Oil-phase Composition, and Oil Fraction. J Sci Food Agric 2022, 102, 4200–4209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, F.; Gómez, J.M.; Ricardez-Sandoval, L.; Alvarez, O. Integrated Design of Emulsified Cosmetic Products: A Review. Chemical Engineering Research and Design 2020, 161, 279–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wibowo, C.; Ng, K.M. Product-oriented Process Synthesis and Development: Creams and Pastes. AIChE Journal 2001, 47, 2746–2767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, T.M.; Mijaljica, D.; Townley, J.P.; Spada, F.; Harrison, I.P. Vehicles for Drug Delivery and Cosmetic Moisturizers: Review and Comparison. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Jung, E.-C.; Zhu, H.; Zou, Y.; Hui, X.; Maibach, H. Vehicle Effects on Human Stratum Corneum Absorption and Skin Penetration. Toxicol Ind Health 2017, 33, 416–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karadzovska, D.; Brooks, J.D.; Monteiro-Riviere, N.A.; Riviere, J.E. Predicting Skin Permeability from Complex Vehicles. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2013, 65, 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nohynek, G.J.; Schaefer, H. Benefit and Risk of Organic Ultraviolet Filters. Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology 2001, 33, 285–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montenegro, L.; Turnaturi, R.; Parenti, C.; Pasquinucci, L. In Vitro Evaluation of Sunscreen Safety: Effects of the Vehicle and Repeated Applications on Skin Permeation from Topical Formulations. Pharmaceutics 2018, 10, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikolić, S.; Keck, C.M.; Anselmi, C.; Müller, R.H. Skin Photoprotection Improvement: Synergistic Interaction between Lipid Nanoparticles and Organic UV Filters. Int J Pharm 2011, 414, 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wissing, S. Cosmetic Applications for Solid Lipid Nanoparticles (SLN). Int J Pharm 2003, 254, 65–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souto, E.B.; Jäger, E.; Jäger, A.; Štěpánek, P.; Cano, A.; Viseras, C.; de Melo Barbosa, R.; Chorilli, M.; Zielińska, A.; Severino, P.; et al. Lipid Nanomaterials for Targeted Delivery of Dermocosmetic Ingredients: Advances in Photoprotection and Skin Anti-Aging. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, L.A.; Contri, R. V.; Beck, R.C.R.; Pohlmann, A.R.; Guterres, S.S. Improving Drug Biological Effects by Encapsulation into Polymeric Nanocapsules. WIREs Nanomedicine and Nanobiotechnology 2015, 7, 623–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jee, J.-P.; Lim, S.-J.; Park, J.-S.; Kim, C.-K. Stabilization of All-Trans Retinol by Loading Lipophilic Antioxidants in Solid Lipid Nanoparticles. European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics 2006, 63, 134–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, R.H.; Radtke, M.; Wissing, S.A. Nanostructured Lipid Matrices for Improved Microencapsulation of Drugs. Int J Pharm 2002, 242, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemiyeh, P.; Mohammadi-Samani, S. Solid Lipid Nanoparticles and Nanostructured Lipid Carriers as Novel Drug Delivery Systems: Applications, Advantages and Disadvantages. Res Pharm Sci 2018, 13, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, R.H.; Mäder, K.; Gohla, S. Solid Lipid Nanoparticles (SLN) for Controlled Drug Delivery- a Review of the State of the Art. European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics 2000, 50, 161–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puglia, C.; Santonocito, D.; Bonaccorso, A.; Musumeci, T.; Ruozi, B.; Pignatello, R.; Carbone, C.; Parenti, C.; Chiechio, S. Lipid Nanoparticle Inclusion Prevents Capsaicin-Induced TRPV1 Defunctionalization. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santonocito, D.; Raciti, G.; Campisi, A.; Sposito, G.; Panico, A.; Siciliano, E.A.; Sarpietro, M.G.; Damiani, E.; Puglia, C. Astaxanthin-Loaded Stealth Lipid Nanoparticles (AST-SSLN) as Potential Carriers for the Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease: Formulation Development and Optimization. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Eroğlu, C.; Sinani, G.; Ulker, Z. Current State of Lipid Nanoparticles (SLN and NLC) for Skin Applications. Curr Pharm Des 2023, 29, 1632–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samee, A.; Usman, F.; Wani, T.A.; Farooq, M.; Shah, H.S.; Javed, I.; Ahmad, H.; Khan, R.; Zargar, S.; Kausar, S. Sulconazole-Loaded Solid Lipid Nanoparticles for Enhanced Antifungal Activity: In Vitro and In Vivo Approach. Molecules 2023, 28, 7508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassano, R.; Serini, S.; Curcio, F.; Trombino, S.; Calviello, G. Preparation and Study of Solid Lipid Nanoparticles Based on Curcumin, Resveratrol and Capsaicin Containing Linolenic Acid. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sohaib, M.; Shah, S.U.; Shah, K.U.; Shah, K.U.; Khan, N.R.; Irfan, M.M.; Niazi, Z.R.; Alqahtani, A.A.; Alasiri, A.; Walbi, I.A.; et al. Physicochemical Characterization of Chitosan-Decorated Finasteride Solid Lipid Nanoparticles for Skin Drug Delivery. Biomed Res Int 2022, 2022, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shidhaye, S.; Vaidya, R.; Sutar, S.; Patwardhan, A.; Kadam, V. Solid Lipid Nanoparticles and Nanostructured Lipid Carriers – Innovative Generations of Solid Lipid Carriers. Curr Drug Deliv 2008, 5, 324–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montenegro, L.; Lai, F.; Offerta, A.; Sarpietro, M.G.; Micicchè, L.; Maccioni, A.M.; Valenti, D.; Fadda, A.M. From Nanoemulsions to Nanostructured Lipid Carriers: A Relevant Development in Dermal Delivery of Drugs and Cosmetics. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol 2016, 32, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santonocito, D.; Vivero-Lopez, M.; Lauro, M.R.; Torrisi, C.; Castelli, F.; Sarpietro, M.G.; Puglia, C. Design of Nanotechnological Carriers for Ocular Delivery of Mangiferin: Preformulation Study. Molecules 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puglia, C.; Blasi, P.; Ostacolo, C.; Sommella, E.; Bucolo, C.; Platania, C.B.M.; Romano, G.L.; Geraci, F.; Drago, F.; Santonocito, D.; et al. Innovative Nanoparticles Enhance N-Palmitoylethanolamide Intraocular Delivery. Front Pharmacol 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viegas, C.; Patrício, A.B.; Prata, J.M.; Nadhman, A.; Chintamaneni, P.K.; Fonte, P. Solid Lipid Nanoparticles vs. Nanostructured Lipid Carriers: A Comparative Review. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katari, O.; Jain, S. Solid Lipid Nanoparticles and Nanostructured Lipid Carrier-Based Nanotherapeutics for the Treatment of Psoriasis. Expert Opin Drug Deliv 2021, 18, 1857–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souto, E.B.; Baldim, I.; Oliveira, W.P.; Rao, R.; Yadav, N.; Gama, F.M.; Mahant, S. SLN and NLC for Topical, Dermal, and Transdermal Drug Delivery. Expert Opin Drug Deliv 2020, 17, 357–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montenegro, L.; Sarpietro, M.G.; Ottimo, S.; Puglisi, G.; Castelli, F. Differential Scanning Calorimetry Studies on Sunscreen Loaded Solid Lipid Nanoparticles Prepared by the Phase Inversion Temperature Method. Int J Pharm 2011, 415, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wissing, S.A.; Müller, R.H. Solid Lipid Nanoparticles as Carrier for Sunscreens: In Vitro Release and in Vivo Skin Penetration. Journal of Controlled Release 2002, 81, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puglia, C.; Damiani, E.; Offerta, A.; Rizza, L.; Tirendi, G.G.; Tarico, M.S.; Curreri, S.; Bonina, F.; Perrotta, R.E. Evaluation of Nanostructured Lipid Carriers (NLC) and Nanoemulsions as Carriers for UV-Filters: Characterization, in Vitro Penetration and Photostability Studies. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2014, 51, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacatusu, I.; Badea, N.; Murariu, A.; Bojin, D.; Meghea, A. Effect of UV Sunscreens Loaded in Solid Lipid Nanoparticles: A Combinated SPF Assay and Photostability. Molecular Crystals and Liquid Crystals 2010, 523, 247/[819]–259/[831]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E Chatelain; B Gabard Photostabilization of Butyl Methoxydibenzoylmethane (Avobenzone) and Ethylhexyl Methoxycinnamate by Bis-Ethylhexyloxyphenol Methoxyphenyl Triazine (Tinosorb S), a New UV Broadband Filter. Photochem Photobiol. 2001, 74, 401–406. [CrossRef]

- Benevenuto, C.G.; Guerra, L.O.; Gaspar, L.R. Combination of Retinyl Palmitate and UV-Filters: Phototoxic Risk Assessment Based on Photostability and in Vitro and in Vivo Phototoxicity Assays. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2015, 68, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, T.S.; Moreira, L.M.C.C.; Oliveira, T.M.T.; Melo, D.F.; Azevedo, E.P.; Gadelha, A.E.G.; Fook, M.V.L.; Oshiro-Júnior, J.A.; Damasceno, B.P.G.L. Bemotrizinol-Loaded Carnauba Wax-Based Nanostructured Lipid Carriers for Sunscreen: Optimization, Characterization, and In Vitro Evaluation. AAPS PharmSciTech 2020, 21, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teixeira Gomes, J.V.; Cherem Peixoto da Silva, A.; Lamim Bello, M.; Rangel Rodrigues, C.; Aloise Maneira Corrêa Santos, B. Molecular Modeling as a Design Tool for Sunscreen Candidates: A Case Study of Bemotrizinol. J Mol Model 2019, 25, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Ruiz, C.D.; Plautz, J.R.; Schuetz, R.; Sanabria, C.; Hammonds, J.; Erato, C.; Klock, J.; Vollhardt, J.; Mesaros, S. Preliminary Clinical Pharmacokinetic Evaluation of Bemotrizinol - A New Sunscreen Active Ingredient Being Considered for Inclusion under FDA’s over-the-Counter (OTC) Sunscreen Monograph. Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology 2023, 139, 105344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarpietro, M.G.; Santonocito, D.; Castelli, F.; Russo, R.; Puglia, C.; Montenegro, L. Bemotrizinol-Loaded Nanostructured Lipid Carriers for the Development of Sunscreen Emulsions. Journal of Microencapsulation 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Lukic, M.; Jaksic, I.; Krstonosic, V.; Cekic, N.; Savic, S. A Combined Approach in Characterization of an Effective w/o Hand Cream: The Influence of Emollient on Textural, Sensorial and in Vivo Skin Performance. Int J Cosmet Sci 2012, 34, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montenegro, L.; Rapisarda, L.; Ministeri, C.; Puglisi, G. Effects of Lipids and Emulsifiers on the Physicochemical and Sensory Properties of Cosmetic Emulsions Containing Vitamin E. Cosmetics 2015, 2, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, B.; Verma, S. Preparation and Evaluation of Novel In Situ Gels Containing Acyclovir for the Treatment of Oral Herpes Simplex Virus Infections. The Scientific World Journal 2014, 2014, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wissing, S.; Lippacher, A.; Müller, R. Investigations on the Occlusive Properties of Solid Lipid Nanoparticles (SLN). J Cosmet Sci 2001, 52, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Montenegro, L.; Santagati, L. Use of Vegetable Oils to Improve the Sun Protection Factor of Sunscreen Formulations. Cosmetics 2019, 6, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamustafa, F.; Çelebi, N. Development of an Oral Microemulsion Formulation of Alendronate: Effects of Oil and Co-Surfactant Type on Phase Behaviour. J Microencapsul 2008, 25, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neufahrt, A.; Förster, F.J.; Heine, H.; Schaeg, G.; Leonhardi, G. Long-Term Tissue Culture of Epithelial-like Cells from Human Skin (NCTC Strain 2544). Archives for Dermatological Research 1976, 256, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puglia, C.; Tropea, S.; Rizza, L.; Santagati, N.A.; Bonina, F. In Vitro Percutaneous Absorption Studies and in Vivo Evaluation of Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Essential Fatty Acids (EFA) from Fish Oil Extracts. Int J Pharm 2005, 299, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, A.R.; Dias-Ferreira, J.; Cabral, C.; Garcia, M.L.; Souto, E.B. Release Kinetics and Cell Viability of Ibuprofen Nanocrystals Produced by Melt-Emulsification. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 2018, 166, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Madsen, F.B.; Eriksen, S.H.; Andersen, A.J.C.; Skov, A.L. A Reliable Quantitative Method for Determining CBD Content and Release from Transdermal Patches in Franz Cells. Phytochemical Analysis 2022, 33, 1257–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirk, R.D.; Akanji, T.; Li, H.; Shen, J.; Allababidi, S.; Seeram, N.P.; Bertin, M.J.; Ma, H. Evaluations of Skin Permeability of Cannabidiol and Its Topical Formulations by Skin Membrane-Based Parallel Artificial Membrane Permeability Assay and Franz Cell Diffusion Assay. Med Cannabis Cannabinoids 2022, 5, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, V.P.; Elkins, J.; Lam, S.-Y.; Skelly, J.P. Determination of in Vitro Drug Release from Hydrocortisone Creams. Int J Pharm 1989, 53, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friend, D.R. In Vitro Skin Permeation Techniques. Journal of Controlled Release 1992, 18, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Colantonio, S.; Dawson, A.; Lin, X.; Beecker, J. Sunscreen Application, Safety, and Sun Protection: The Evidence. J Cutan Med Surg 2019, 23, 357–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.; Shin, S.; Ryu, D.; Cho, E.; Yoo, J.; Park, D.; Jung, E. Evaluating the Sun Protection Factor of Cosmetic Formulations Containing Afzelin. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 2021, 69, c21-00398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breneman, A. Sun Protection Factor Testing: A Call for an In Vitro Method. Cutis 2022, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fageon, L.; Moyal, D.; Coutet, J.; Candau, D. Importance of Sunscreen Products Spreading Protocol and Substrate Roughness for in Vitro Sun Protection Factor Assessment. Int J Cosmet Sci 2009, 31, 405–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pardeike, J.; Hommoss, A.; Müller, R.H. Lipid Nanoparticles (SLN, NLC) in Cosmetic and Pharmaceutical Dermal Products. Int J Pharm 2009, 366, 170–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutra, E.A.; Oliveira, D.A.G. da C.; Kedor-Hackmann, E.R.M.; Santoro, M.I.R.M. Determination of Sun Protection Factor (SPF) of Sunscreens by Ultraviolet Spectrophotometry. Revista Brasileira de Ciências Farmacêuticas 2004, 40, 381–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayre, R.M.; Agin, P.P.; LeVee, G.J.; Marlowe, E. A COMPARISON OF IN VIVO AND IN VITRO TESTING OF SUNSCREENING FORMULAS. Photochem Photobiol 1979, 29, 559–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallica, F.; Leonardi, C.; Toscano, V.; Santonocito, D.; Leonardi, P.; Puglia, C. Assessment of Alcohol-Based Hand Sanitizers for Long-Term Use, Formulated with Addition of Natural Ingredients in Comparison to Who Formulation 1. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otto, A.; Du Plessis, J.; Wiechers, J.W. Formulation Effects of Topical Emulsions on Transdermal and Dermal Delivery. Int J Cosmet Sci 2009, 31, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lardy, F.; Vennat, B.; Pouget, M.P.; Pourrat, A. Functionalization of Hydrocolloids: Principal Component Analysis Applied to the Study of Correlations Between Parameters Describing the Consistency of Hydrogels. Drug Dev Ind Pharm 2000, 26, 715–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garg, A.; Aggarwal, D.; Garg, S.; Singla, A.K. Spreading of Semisolid Formulations: An Update. Pharm. Technol. 2002, 26, 84–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montenegro, L.; Parenti, C.; Turnaturi, R.; Pasquinucci, L. Resveratrol-Loaded Lipid Nanocarriers: Correlation between In Vitro Occlusion Factor and In Vivo Skin Hydrating Effect. Pharmaceutics 2017, 9, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wissing, S.A.; Müller, R.H. The Influence of the Crystallinity of Lipid Nanoparticles on Their Occlusive Properties. Int J Pharm 2002, 242, 377–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wester, R.C.; Maibach, H.I. Cutaneous Pharmacokinetics: 10 Steps to Percutaneous Absorption. Drug Metab Rev 1983, 14, 169–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INTERNATIONAL SUN PROTECTION FACTOR (SPF) TEST METHOD. COLIPA Guidelines 2006.

- Cosmetics-Sun Protection Test Methods-In Vivo Determination of the Sun Protection Factor (SPF) COPYRIGHT PROTECTED DOCUMENT; ISO 24444:2019(E) 2019.

- Sheu, M.-T.; Lin, C.-W.; Huang, M.-C.; Shen, C.-H.; Ho, H.-O. Correlation of in Vivo and in Vitro Measurements of Sun Protection Factor. J Food Drug Anal 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pissavini, M.; Tricaud, C.; Wiener, G.; Lauer, A.; Contier, M.; Kolbe, L.; Trullás Cabanas, C.; Boyer, F.; Meredith, E.; de Lapuente, J.; et al. Validation of a New in Vitro Sun Protection Factor Method to Include a Wide Range of Sunscreen Product Emulsion Types. Int J Cosmet Sci 2020, 42, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, E.P.; Freitas, Z.M.; Souza, K.R.; Garcia, S.; Vergnanini, A. In Vitro and In Vivo Determinations of Sun Protection Factors of Sunscreen Lotions with Octylmethoxycinnamate. Int J Cosmet Sci 1999, 21, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraf, S.; Kaur, C. In Vitro Sun Protection Factor Determination of Herbal Oils Used in Cosmetics. Pharmacognosy Res 2010, 2, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Netto MPharm, G.; Jose, J. Development, Characterization, and Evaluation of Sunscreen Cream Containing Solid Lipid Nanoparticles of Silymarin. J Cosmet Dermatol 2018, 17, 1073–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ácsová, A.; Hojerová, J.; Janotková, L.; Bendová, H.; Jedličková, L.; Hamranová, V.; Martiniaková, S. The Real UVB Photoprotective Efficacy of Vegetable Oils: In Vitro and in Vivo Studies. Photochemical & Photobiological Sciences 2021, 20, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.I.; Liu, S.; Brooks, G.J.; Lanctot, Y.; Gruber, J. V Reliable and Simple Spectrophotometric Determination of Sun Protection Factor: A Case Study Using Organic <scp>UV</Scp> Filter-based Sunscreen Products. J Cosmet Dermatol 2018, 17, 518–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermund, D.B.; Torsteinsen, H.; Vega, J.; Figueroa, F.L.; Jacobsen, C. Screening for New Cosmeceuticals from Brown Algae Fucus Vesiculosus with Antioxidant and Photo-Protecting Properties. Mar Drugs 2022, 20, 687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wissing, S.A.; Müller, R.H. Solid Lipid Nanoparticles (SLN)--a Novel Carrier for UV Blockers. Pharmazie 2001, 56, 783–786. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- de Araújo, M.M.; Schneid, A.C.; Oliveira, M.S.; Mussi, S. V.; de Freitas, M.N.; Carvalho, F.C.; Bernes Junior, E.A.; Faro, R.; Azevedo, H. NLC-Based Sunscreen Formulations with Optimized Proportion of Encapsulated and Free Filters Exhibit Enhanced UVA and UVB Photoprotection. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubuisson, P.; Picard, C.; Grisel, M.; Savary, G. How Does Composition Influence the Texture of Cosmetic Emulsions? Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp 2018, 536, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szulc-Musioł, B.; Siemiradzka, W.; Dolińska, B. Formulation and Evaluation of Hydrogels Based on Sodium Alginate and Cellulose Derivatives with Quercetin for Topical Application. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 7826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gore, E.; Picard, C.; Savary, G. Spreading Behavior of Cosmetic Emulsions: Impact of the Oil Phase. Biotribology 2018, 16, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, G.M.S.; Srebernich, S.M.; Souza, J.A. de M. Stability and Sensory Assessment of Emulsions Containing Propolis Extract and/or Tocopheryl Acetate. Brazilian Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2011, 47, 585–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilcast, D.; Clegg, S. Sensory Perception of Creaminess and Its Relationship with Food Structure. Food Qual Prefer 2002, 13, 609–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ingredients | Emulsion code | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A12 | A12NLC | A14 | A14NLC | A16 | A16NLC | |

| Phase A | ||||||

| Almond oil | 1.50 | 1.50 | 1.75 | 1.75 | 2.00 | 2.00 |

| Glycine Soja oil | 1.50 | 1.50 | 1.75 | 1.75 | 2.00 | 2.00 |

| Acemol TN | 3.60 | 3.60 | 4.20 | 4.20 | 4.80 | 4.80 |

| Cetiol SN | 1.20 | 1.20 | 1.40 | 1.40 | 1.60 | 1.60 |

| IPM | 1.20 | 1.20 | 1.40 | 1.40 | 1.60 | 1.60 |

| Montanov 68 | 2.40 | 2.40 | 2.80 | 2.80 | 3.20 | 3.20 |

| Beeswax | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.40 | 0.40 |

| Cutina MD | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.40 | 0.40 |

| BMTZ | 2.40 | --- | 2.40 | --- | 2.40 | --- |

| Phase B | ||||||

| EDTA | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Water | q.s. | q.s. | q.s. | q.s. | q.s. | q.s. |

| Phase C | ||||||

| Kemipur 100 | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.35 |

| Benzyl alcohol | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| Phase D | ||||||

| BMTZ-NLC | --- | 30.00 | --- | 30.00 | --- | 30.00 |

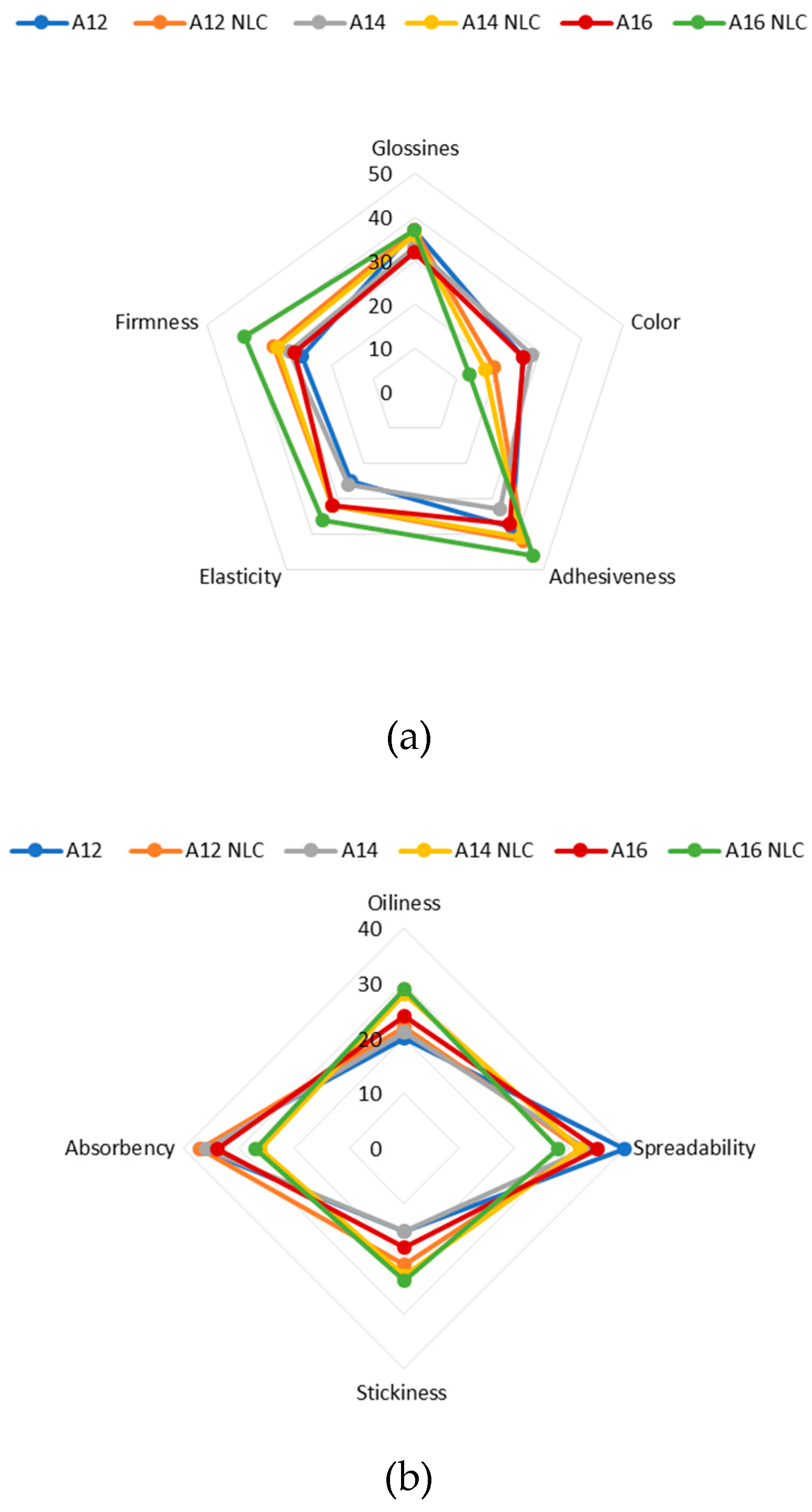

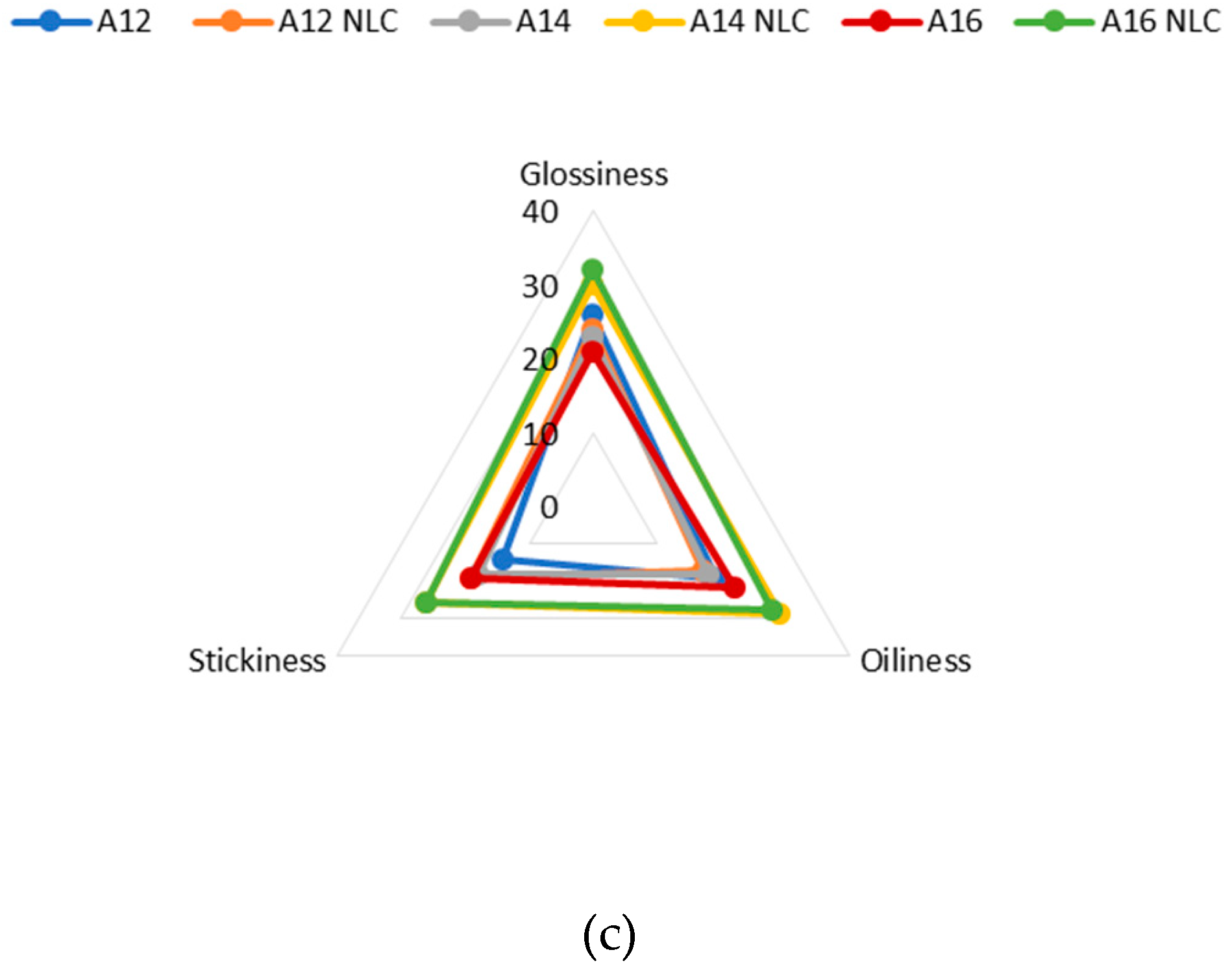

| Phase | Sensory attribute | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Before and during pick-up | Color (in the container) | 1. White; 2. Whitish; 3 yellowish; 4. Pale yellow; 5. Yellow |

| Glossiness (in the container) | 1. Not glossy; 2. Slightly glossy; 3. Moderately glossy; 4. Glossy; 5. Very glossy | |

|

Adhesiveness Amount of sample that stays on forefinger after short contact (2 s) with sample in container |

1. Not adhesive; 2. Slightly adhesive; 3. Moderately adhesive; 4. Adhesive; 5. Very adhesive | |

|

Elasticity Degree to which product expands between thumb and forefinger |

1. Not elastic; 2. Slightly elastic; 3. Moderately elastic; 4. Elastic; 5. Very elastic | |

| Firmness (during pick-up) Resistance to deformation and difficulty of lifting from container. | 1. Not firm; 2. Slightly firm; 3. Moderately firm; 4. Firm; 5. Very firm | |

| During rub-in |

Oiliness Degree to which the sample feels oily |

1. Not oily; 2. Slightly oily; 3. Moderately oily; 4. Oily; 5. Very oily |

|

Spreadability Impression of the area that the sample will cover while being rubbed 8 times in a circular motion over the back of the hand |

1. Not spreadable; 2. Slightly spreadable; 3. Moderately spreadable; 4. Spreadable; 5. Very spreadable | |

|

Stickiness Degree to which the sample feels sticky (force required to separate finger from the skin) |

1. Not sticky; 2. Slightly sticky; 3. Moderately sticky; 4. Sticky; 5. Very sticky | |

|

Absorbency Impression of the rate of absorption of the sample into the skin |

1. Not absorbed; 2. Slowly absorbed; 3. Moderately absorbed; 4. Absorbed; 5. Fast absorbed | |

| After feel |

Stickiness Degree to which the sample leaves the skin feeling sticky 10 min after its application |

1. Not sticky; 2. Slightly sticky; 3. Moderately sticky; 4. Sticky; 5. Very sticky |

|

Oiliness Degree to which the sample leaves the skin feeling oily 10 min after its application |

1. Not oily; 2. Slightly oily; 3. Moderately oily; 4. Oily; 5. Very oily | |

|

Glossiness Degree to which the sample leaves the skin looking glossy 10 min after its application |

1. Not glossy; 2. Slightly glossy; 3. Moderately glossy; 4. Glossy; 5. Very glossy |

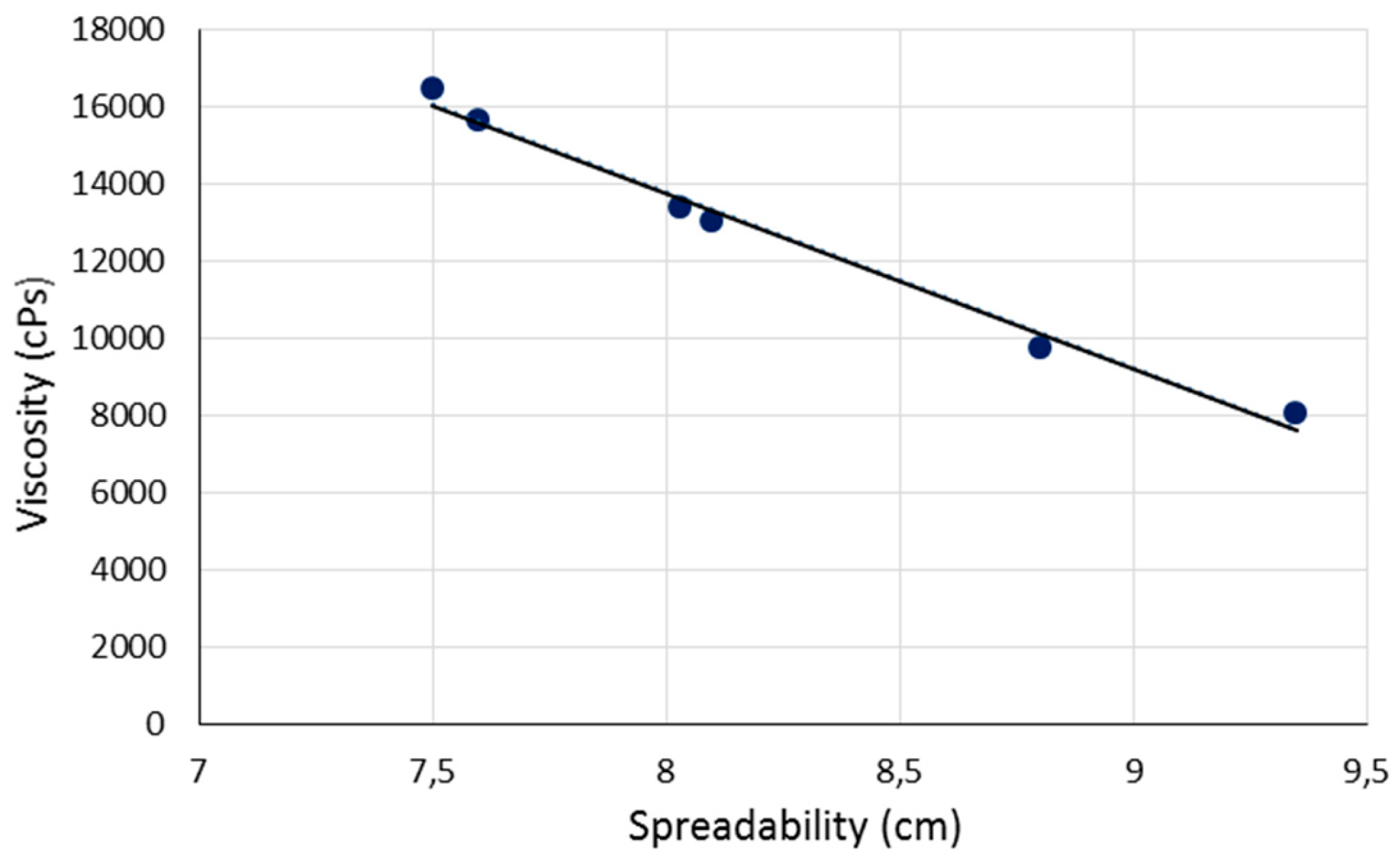

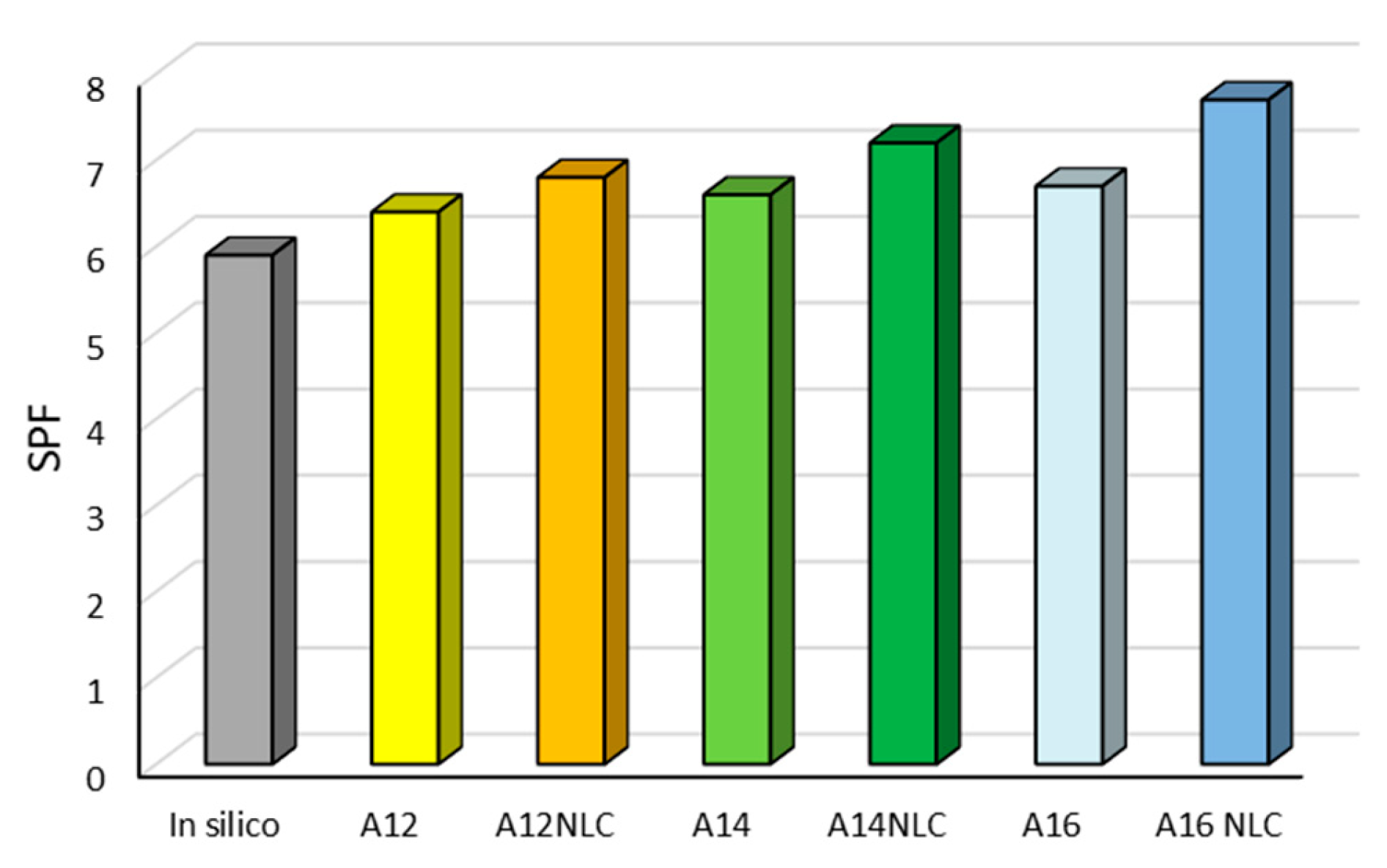

| EMULSION CODE | PH | F ± S.D. | S± S.D. (CM) |

V± S.D. (CPS) |

Q (μG/CM2) |

| A12 | 6,3 | 35,53 ± 5,69 | 8,80 ± 0,17 | 9.722 ± 1.295 | N.D. |

| A12NLC | 6,3 | 25,91 ± 1,57 | 9,35 ± 0,21 | 8.017 ± 143 | N.D. |

| A14 | 6,4 | 47,75 ± 1,16 | 8,10 ± 0,17 | 13.000 ± 441 | N.D. |

| A14NLC | 6,3 | 39,76 ± 2,99 | 8,03 ± 0,25 | 13.389 ± 1.004 | N.D. |

| A16 | 6,5 | 46,81 ± 1,55 | 7,60 ± 0,10 | 15.611 ± 1.549 | N.D. |

| A16NLC | 6,4 | 32,48 ± 2,09 | 7,50 ± 0,10 | 16.444 ± 770 | N.D. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).