1. Introduction

We utilized a large Danish birth cohort to ask whether the gender-specific patterns of psychiatric comorbidity reported worldwide also holds true for specific psychiatric diagnostic groups, such as Alcohol Use Disorder. If gender differences are similar for men and women across the diagnostic spectrum, that would suggest a common etiological foundation and a common platform from which to conduct research and make treatment decisions. On the other hand, if gender-related patterns of psychiatric comorbidity were found to substantially vary by primary psychiatric diagnoses, that would suggest the temporal, etiological and treatment implications of comorbid conditions may not be the same across the major diagnostic classes. Despite the similarities in phenotype, depression among patients diagnosed with schizophrenia may not function in the same manner as the depression co-morbid with the alcohol use disorders or the somatization disorders or the anxiety disorders or anti-social disorders. Possibly, these phenomenologically similar co-morbid conditions may reflect different etiologies that will necessitate different approaches to treatment and are in fact associated with different long-term outcomes.

Over the past 40 years, research based on DSM-III (1980), DSM-IV (1994) and DSM-5 (2013) has shown consistently high levels of psychiatric comorbidity among large clinical populations and community samples (Bourdon et al., 1992; Kessler et al., 1997; Kessler et al., 2005; Hasin et al., 2007; Grant et al., 2015). Individuals receiving treatment for a psychiatric illness usually have higher levels of psychiatric comorbidity than individuals recruited for community samples. Inpatients being treated for a psychiatric illness typically show the highest rate of co-occurring psychiatric disorders (Regier et al., 1990; Penick et al., 1994; Weaver et al., 2003; De ScaFani et al., 2008). Especially high rates of psychiatric comorbidity are associated with the abuse of alcohol and other drugs among treated and untreated samples. It is generally accepted that 40 to 60% of individuals who abuse alcohol also meet criteria for at least one other non-substance related comorbid psychiatric illness (Wiessman et al., 1980; Powell et al., 1982; Regier et al., 1990; Penick et al., 1994; Smith et al, 2006). Psychiatric comorbidity contributes measurably to the overall burden of illness for society in general (Kessler et al, 1994; Kranzler et al, 1996a; Kranzler et al., 1996b; Merikangas et al., 1998; Wu et al., 1999; Zilberman et al., 2003; Madarasz et al., 2012). A disproportionate share of resources used to treat the mentally ill is spent on a relatively small number of individuals who suffer from three or more co-occurring, lifetime psychiatric illnesses that often include a substance use disorder (Wu et al., 1999). Fully understanding the diagnostic and treatment implications of psychiatric comorbidity is considered of particular importance in preventing and relieving the suffering that is associated with psychiatric illness. (Castillo-Carniglia, et al., 2019)

Gender differences among what are now considered representations of psychiatric illness have been recognized since ancient times (Jackson, S. W. 1986). Contemporary research has consistently reaffirmed those ancient observations in large-scale clinic and community studies. The lifetime prevalence of depression, anxiety, somatoform and eating disorders is typically found to be higher among females than males, while alcohol and drug abuse, asocial, antisocial and developmental disabilities are more commonly found among males (Kessler et al., 1997; King et al., 2003; Hasin et al., 2007; Flensborg-Madsen et al., 2009; Greant et al., 2014). The question remains whether this widely reported pattern of gender differences found across heterogenous groups of individuals suffering from a psychiatric illness is also found among individuals who suffer from a specific psychiatric illness. Until recently, studies of gender-related differences within specific diagnostic groups have been relatively rare and often limited by: the number of major diagnostic groups compared; the range of comorbid disorders evaluated; the relatively small sample sizes; reliance on retrospective recall; and, the methodology used to formulate a diagnosis (Kessler et al., 1994; Kranzler et al., 1996; Gabe., 2000).

More recent studies have suggested that compared to men, women demonstrate higher levels of psychiatric comorbidity and greater functional impairment (Zilberman, et al., 2003; White, 2020).

The present study used archival data to examine differences in the prevalence of clinical diagnoses assigned to psychiatrically treated men and women who did or did not receive an alcoholism diagnosis. We chose to begin our study with the diagnosis of alcoholism because this disorder is highly prevalent and especially costly to the individual and society. Moreover, there are hints in the literature that the psychiatric comorbidity among men and women who suffer from an Alcohol Use Disorder may differ from that found among non-substance abusing samples. For example, Helzer and Pryzbeck (1998), Compton et al. (2005), and Khan et al. (2013), reported higher-than-expected rates of antisocial behavior among females diagnosed as alcohol dependent. More recently, Goldstein et al. (2012) and Khan et al. (2013) examined gender differences among a large group of community individuals. They compared lifetime psychiatric disorders among those who did or did not meet lifetime criteria for Alcohol Dependence. Although widespread numerical differences were reported in the pattern of comorbid psychiatric disorders among men and women who did or did not meet criteria for alcohol dependence, when adjusted for sociodemographic characteristics and psychiatric co-morbidity, Goldstein et al. (2012) concluded: “few sex differences in epidemiologically assessed co-morbid association of SUDs with other psychiatric disorders…” (p. 948). We felt that adjustments of these kinds might fundamentally distort the clinical pictures observed over and over in various clinical settings. We believed that the use of a treated population of highly representative, significantly ill, individuals would provide a more accurate picture of “nature” in its truest form. Our examination of the Copenhagen Perinatal Birth Cohort at age 45 allowed us to systemically compare the prevalence of a wide range of psychiatric diagnoses for male and female patients with and without a clinical diagnosis of alcoholism, well past the age of risk for developing that psychiatric disorder. The study was approved by the Danish Scientific Ethics Committee and the Institutional Review Board of the University of Kansas Medical Center.

2. Methods

Patients

The study sample consisted of male and female subjects who are part of a large Copenhagen birth cohort that originally contained 9,125 consecutive deliveries (over 20 weeks gestation) from 1959 through 1961 (Villumsen., 1970; Zachau-Christiansen., 1972). All births took place in the maternity ward of the State University Hospital (Rigshospitalet) in Copenhagen. The original cohort contains an overrepresentation of mothers from a slightly lower social class and a predominantly urban environment who were at a modestly increased risk of pregnancy and birth complications compared to Denmark as a whole (Baker., 1984). Of the original 9,125 babies enrolled in the cohort, 728 were stillborn or died in the first year and were therefore excluded from follow-up. Another 288 subjects did not have personal identification numbers and thus could not be linked to the Central Psychiatric Register or other Danish archival sources. These subjects are presumed to have died or emigrated from Denmark as children before the centralized Civil Registry System (CRS) was created in 1968. At age 45, lifetime psychiatric outcomes were obtained for the 8,109 remaining subjects by means of record linkage to the Danish Central Psychiatric Register. This national register includes all diagnoses recorded for all admissions to an inpatient or outpatient psychiatric facility over the lifetime of the patients. Of the 8,109 eligible subjects, approximately 50% were male; 1,247 or 15 percent of the eligible patients were admitted at least once for treatment in a Danish psychiatric faculty.

Categorization of Hospital Psychiatric Diagnoses

Until 1994, diagnoses in Denmark were based upon Edition 8 of the International Classification of Diseases, (ICD-8). In 1994 the ICD-10 system was adopted in Denmark (Denmark never formally adopted ICD-9). In order to standardize study procedures, all ICD-8 diagnoses were first converted to ICD-10 diagnoses according to a crosswalk published by the World Health Organization (1992). Only the ICD-10 F diagnostic codes used to classify

Mental and Behavioral Disorders were considered for this study. ICD-10 diagnoses associated other broad medical groups, such as Neurology, were excluded from consideration. Because many of the specific ICD-10 F codes reflected variations of the same illness, they were organized into 14, mutually exclusive, summary diagnostic “families” or categories as shown in

Appendix A which operationally defines how each category was constructed.

The organization of the ICD-10, Group F codes into 14 separate and distinct summary diagnostic categories largely followed the schema of the international classification system; nevertheless, several exceptions were made to increase compatibility with the contemporary DSMs. Because the focus of this study was on the diagnosis of alcoholism, codes for Alcohol-Related Disorders were organized into a separate category, distinguished from other ICD-10 Psychoactive Substance Use diagnoses that were kept separate. The Somatization Disorders were separated into their own category as were the Eating Disorders while Dissociative Disorders were placed in the general category of “Other’. Sleep, Sexual Dysfunction, Puerperal Psychosis and similar rare conditions were also classified in the “Other” category. The ICD-10 F category representing the Personality Disorders underwent the greatest modification in our diagnostic summary schema. Those ICD-10 codes that reflect Gender Identity Disorder, Disorders of Sexual Preference, Paraphilias, Development of Orientation were placed in the “Other” category. We also placed the code for Trichotillomania in the “Other” category. The externalizing Personality Disorders were combined and placed into two groups labeled Dissocial Personality Disorders and Unstable Personality Disorders. We hypothesized that these personality subtypes would best capture differences known to strongly correlate with the substance use disorders. Several other F codes were added to the Dissocial Personality Disorder category from the ICD-10 section on Behavioral and Emotional Disorders with Onset Occurring in Childhood and Adolescence. These added childhood diagnoses included the Hyperkinetic and Conduct Disorders diagnoses. A total of 376 separate and distinct psychiatric diagnoses were assigned by treating physicians to the 1,247 patients in this study. Once converted to an ICD-10 F diagnosis, each were classified into one of the 14 summary diagnostic categories found in

Appendix A. A single diagnosis within a summary category was sufficient to consider that entire category as positive or present for a given individual, regardless of when or how often the diagnostic code was assigned.

Study Design and Data Analysis

Gender and the assignment of an alcoholism diagnosis served as the two major independent variables. The two dependent variables were: (1) An index of the intensity of psychiatric comorbidity as reflected by the number of diagnostic categories out of 13, that were present for each subject, excluding an alcoholism diagnosis. (2) The pattern of psychiatric comorbidity was indicated by the prevalence of nonalcohol-related disorders across the 13 categories of psychiatric conditions. The effect of gender and an alcoholism diagnosis on the number of different summary diagnostic categories assigned to each patient was examined using a 2 x 2 Analysis of Variance. The prevalence of the independent diagnostic categories was compared for patients with and without an alcoholism diagnosis by means of the Chi Square test and those data are presented as percents. We chose not to control for co-variants because this is not something clinicians ordinarily do when they see patients professionally. Instead, we hoped to provide an understandable composite clinical picture of the psychiatric comorbidity of treated patients who do or do not also suffer from an Alcohol Use Disorder.

3. Results

Total Sample

Of the 1,247 birth cohort patients found in the Central Psychiatric Register by age 45, about half were male (N=633). The mean number of positive diagnostic categories out of the 14 for the total sample was 2.06 (SD=1.47). The number of positive diagnostic categories in the total sample did not differ by gender when the sample was considered in its entirety.

Table 1 shows the percent of male and female patients who were assigned to each of the 14 ICD-10 F summary diagnostic categories when the total sample was considered.

The diagnostic categories in

Table 1 have been ordered to more clearly reflect the pattern of male-female differences in comorbidity. As universally reported, males in the total sample were significantly more likely than females to be assigned an alcoholism diagnosis (39% vs. 19.7%). A greater proportion of men also received a diagnosis for a nonalcohol-related substance abuse disorder (23.4% vs. 13.5%). Male patients, compared to female patients, were more frequently assigned the diagnosis of schizophrenia, dissocial personality disorder and developmental disorder in the total sample. Male patients were also more frequently assigned one of the rare psychiatric disorders that fell into the “Other Mental Illness” category.

In contrast, female patients in the total sample were more likely than males to receive the diagnosis of a mood disorder, anxiety disorder, unstable personality disorder, eating disorder or somatoform disorder. The incidence of organic brain syndrome, mental retardation or a non-externalizing personality disorder was not distinguished by gender. The pattern of gender differences found across the 14 broad diagnostic categories for the combined total sample is fairly typical of the pattern commonly reported for large, unselected groups of individuals as well as large heterogenous groups of psychiatric patients.

Comparison of Patients With and Without An Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD)

Twenty-nine percent of the 1,247 inpatient patients (N=368) were assigned an alcoholism diagnosis (AUD). A disproportionate number of the patients who received an AUD diagnosis were male (N=247, 67%) compared to female (N=121, 33%), a 2 to 1 ratio that is consistent with historical reports (p<.001). Eighty percent of the patients assigned an AUD diagnosis were also assigned at leastne other nonalcohol-related diagnosis. In contrast, only 40% of patients without an alcoholism diagnosis were assigned a second, separate, comorbid diagnosis. This difference was highly significant (p<.0001) and indicates the exceptionally high rates of psychiatric comorbidity among treated patients who suffered from an AUD.

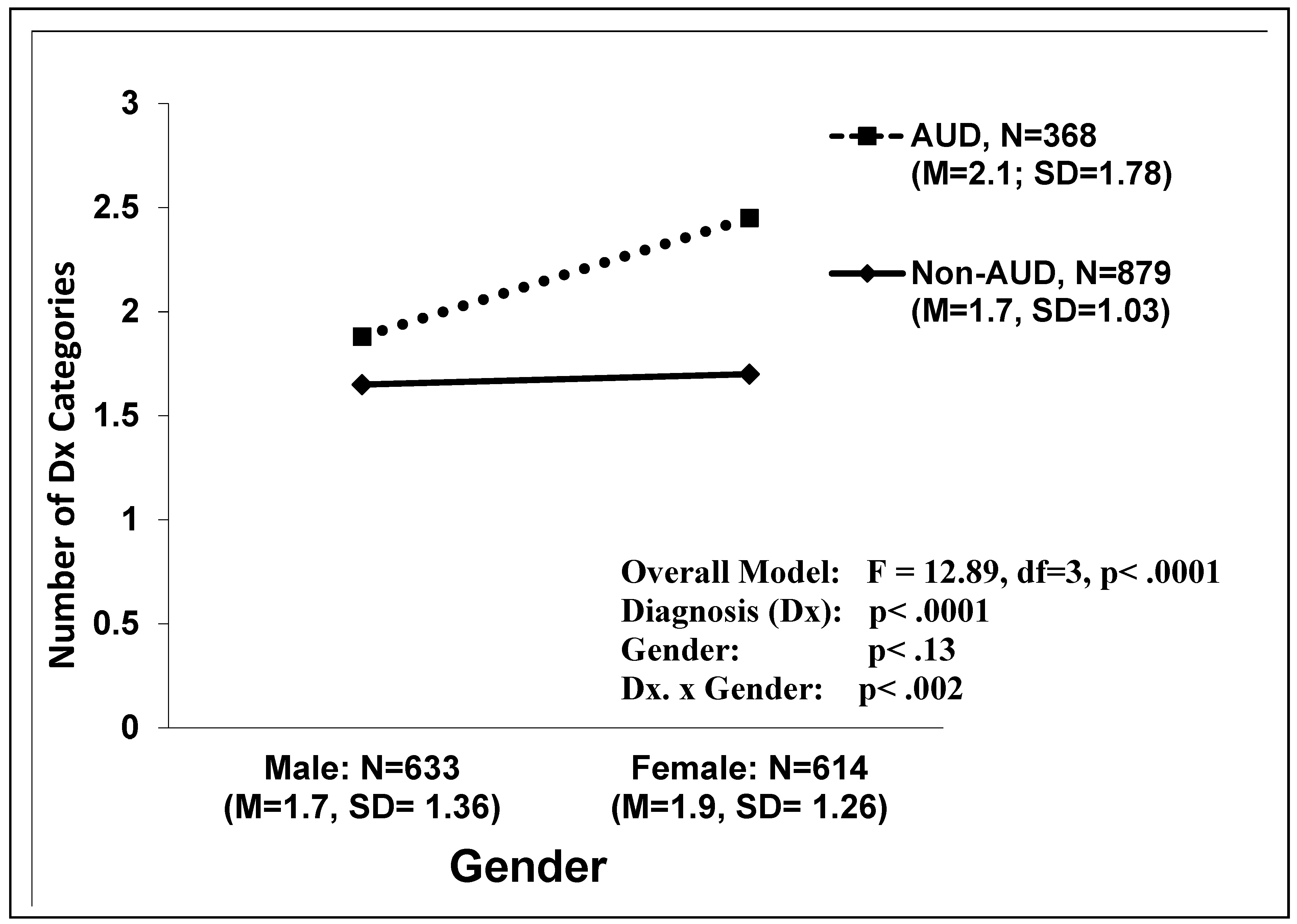

Figure 1 shows the mean number of psychiatric diagnostic categories that were assigned to the male and female inpatients with and without an AUD diagnosis. The overall ANOVA was highly significant (F=12.99, df=3, p<.0001). Patients with an AUD diagnosis received significantly more additional comorbid diagnoses than those patients without an AUD diagnosis (p<.0001), even when the alcohol diagnosis was removed from the count. Female patients as a whole were assigned more summary diagnoses than male patients, although this finding only approached significance.

The effect of gender on the degree of psychiatric comorbidity was accounted for by the significant interaction between gender and an AUD diagnosis (p<.002). Female patients with an AUD diagnosis received a disproportionally greater number of comorbid diagnoses than female patients without an AUD diagnosis. In contrast, males with an AUD diagnosis did not demonstrate more psychiatric comorbidity than males without an AUD diagnosis. This result suggests that women with an alcohol diagnosis suffer the greatest mental health burden, a finding alluded to by Merikangas et al (1998) in their comprehensive review of 6 international studies focused on the co-morbidity of substance abuse disorders.

Table 2 shows the effect of gender and an AUD diagnosis on the pattern or prevalence of psychiatric comorbidity across the 13 psychiatric diagnostic categories, excluding AUD. It will be noted that the pattern of gender differences across the thirteen diagnostic categories for patients

without an AUD diagnosis essentially replicates the pattern for the combined sample shown in

Table 1, as expected. However, the pattern of gender differences found across the diagnostic categories for patients with an AUD diagnosis is quite different.

Although more of the male than female patients in the non-AUD group were assigned a nonalcohol-related substances abuse diagnosis (Male=16.8%; Female=8.3%; p<.0001), no gender difference was found for substance abuse in the AUD group:33.6% of the males and 34.7% of the females among the AUD patients were assigned a nonalcohol-related substance abuse problem. The elevated prevalence of non-alcohol related substance abuse among patients assigned an AUD diagnosis (p<.0001) is not unexpected; however the failure to find a gender difference for substance abuse among the AUD male and female patients was not anticipated. All of the gender differences that were found significantly more often among males without an AUD diagnosis, failed to distinguish men from women who had been assigned an alcoholism diagnosis. Thus, schizophrenia, dissocial personality disorder, developmental disorder and other mental disorders that were more frequently associated with men in the non-AUD diagnostic group, no longer separated the men and women in the AUD diagnosis group. This result was not true for those disorders that were more frequently reported among females. Diagnostic categories that were more commonly reported among women without an AUD diagnosis, continued to be more prevalent among woman with an AUD diagnosis. The data suggest that the presence of an AUD diagnosis in women essentially neutralized male-dominant disorders.

4. Discussion

The results of this study suggested that the intensity and pattern of comorbid psychiatric illnesses among men and women with an AUD may differ from that reported for large heterogeneous psychiatric and community samples. Both the number of comorbid diagnostic categories and the pattern of comorbid disorders differed among male and female treated patients according to whether or not an alcoholism-related diagnosis had been assigned. Women with an AUD diagnosis were assigned proportionally more nonalcohol-related disorders than woman without an AUD diagnosis. Women in the AUD diagnosis group were assigned more of the male- dominant diagnoses than women in the non-AUD group. Disorders more frequently assigned to men in the non-AUD group were no longer dominant among men who were given an alcohol-related diagnosis. Disorders more frequently diagnosed among women in the nonalcohol-related group continued to be dominant among women in the AUD group. These findings suggest that the tendency to lump men and women together in large samples of unselected psychiatric patients or community participants may obscure important gender-specific differences that exist across the major diagnostic groups. In the current study, the number of patients was relatively large and representative of a general population. The diagnostic practices of Danish psychiatrists are quite uniform from institution to institution. Additionally, the diagnoses were based upon “real time” observations, not retrospective recall. Moreover, the extension of the study to middle age assures that most patients were well beyond the age of risk for developing an AUD problem. Nevertheless, because only treated in and outpatients were investigated, the generalizability of these findings is limited to those most psychiatrically ill individuals.

Given those caveats, we believe that the findings of this study may indicate a tendency toward masculinization among women who abuse alcohol which could reflect either a precursor to, or consequence of, a serious alcohol use disorder. Our results in general support those of Anthenelli and colleagues (2010) who have looked at the effect of life stressors on biologically driven sex differences in the development of alcoholism and other psychiatric disorders. They have proposed that the female pathway to alcoholism and its psychiatric comorbidities may differ from that of men. Similarly, Goldstein et al. (2012) have suggested that additional research is necessary to better understand “possible sex specificity” (p. 938) that might be associated with the intensity and pattern of psychiatric co-morbidity among alcohol abusing individuals. A previous study by our group with this same birth cohort found that premature birth predicted alcoholism decades later in men, but not in women (Manzardo., 2010). We suggest that a complete understanding of the implications of gender on psychiatric illness will require a detailed accounting about how gender impacts the onset and development of co-occurring psychiatric disorders over time across the major psychiatric disorders.

Author Contributions

ECP, JK and WM designed the study. ECP, WM , WAH, and AMM analyzed the data. ELM provided data support and consultation. WFG provided consultation. ECP, WM wrote the draft manuscript. All authors revised and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded in part by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism grants K01-AA015935, R01-03448, R01-08176, R21-AA13374; Danish Medical Research Council grant 9902952; Augustinus Foundation grant 01-203; Forsikring and Pension grant 1.0.1.8-012; Eli and Egon Larsen Foundation grant 26670002.

Institutional Review Board

The study was approved by the Danish Scientific Ethics Committee and the Institutional Review Board of the University of Kansas Medical Center (IRB: 8708).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

We encourage all authors of articles published in MDPI journals to share their research data. In this section, please provide details regarding where data supporting reported results can be found, including links to publicly archived datasets analyzed or generated during the study. Where no new data were created, or where data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions, a statement is still required. Suggested Data Availability Statements are available in section “MDPI Research Data Policies” at

https://www.mdpi.com/ethics.

Acknowledgments

We want to extend our sincere appreciation to the people of Denmark for their ongoing contributions to the advancement of research on alcoholism and other psychiatric illnesses.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Definition of 14 Summary Diagnostic Categories Created from ICD-10 F Codes

Organic Mental Disorder (F 00.0 to F 09.0)

Alcohol Use Disorder (F 10.00 to F 10.99)

Any Non-Alcohol Psychoactive Substance Use Disorder (F 11.00 to F 19.99)

Any Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective, Schizotypical or Delusional Disorder (F 20.00 to F 29.99)

Any Mood (Affective) Disorder (F 30.0 to F 39.9, F 48.0)

Any Anxiety or Stress Related Disorder (F 40.00 to F 43.99, F 48.1 to F 48.9)

Any Somatoform Disorder (F 45.00 to F 45.99)

Any Eating Disorder (F 50.0 to F 50.9)

Any Other Personality Disorder Excluding Dissocial and Unstable Personality Disorder (F 60.0 – F 60.1, F 60.5 to 60.9, F 61.0 to F 61.9, F 62.0 to F 62.9, F 68.0 to F 68.8, F 69.0)

Dissocial Personality Disorder (F 60.2, F 63.0 to F 63.2, F 63.8 to F 63.9, F 90.0 to F 90.9, F 91.0 to F 91.9, F 92.0 to F 92.9)

Unstable Personality Disorder (F 60.30, F 60.31, F 60.4)

Any Mental Retardation Diagnosis (F 70.0 to F 79.9)

Any Developmental Disorder (F 80.0 to F 89.9)

Any Other Mental and Behavior Disorder (F 44.0 to F 44.9, F 49, F 51.0 to F 52.9, F 55.9, F 58, F 59, F 63.3, F 64.0 – F 67, F 95.0 to F 95.9, F 98.0 to F 98.9, F 99.0, Z03.2)

References

- (1992) The ICD 9-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioral Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. World Health Organization, Geneva.

- Baker, R. L., Mednick, B. R. (1984). Influences on human development: A longitudinal perspective. Kluwer Nijhof Publishing, Boston MA.

- Bourdon, K. H., Rae, D. S., Locke, B. Z., Narrow, W. E., & Regier, D. A. (1992) Estimating the prevalence of mental disorders in U.S. adults from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area Survey. Public Health Reports, 107(6): 663-8. [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Castillo-Carniglia, A., Keyes, K.M., Hasin, DS, and Cerdá, M. (2019) Psychiatric comorbidities in alcohol use disorder. Lancet Psychiatry, 6(12): 1068-1080. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiSclafani, V., Finn, P., & Fein, G. (2008) Treatment-naïve active alcoholics have greater psychiatric comorbidity than normal controls but less than treated abstinent alcoholics. Drug Alcohol Dependence, 98(1-2): 115-22. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Flensborg-Madsen, T., Mortensen, E. L., Knop, J., Becker, U., Sher, L., & Grønbaek, M. (2009). Comorbidity and temporal ordering of alcohol use disorders and other psychiatric disorders: results from a Danish register-based study. Comprehensive Psychiatry. Jul-Aug;50(4):307-14. Epub 2008 Nov 21. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldstein, R. B., Dawson, D. A., Chou, P., & Grant, B. (2012). Six differences in prevalence and comorbidity of alcohol and drug sue disorders: Results from Wave 2 of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 73: 938-950. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hasin, D. S., Stinson, F. S., Ogburn, E., & Grant, B. F. (2007). Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence in the United States: results from the national Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Archives General Psychiatry. 64(7): 830-42. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, S. W. (1986). Melancholia and depression: From hippocratic times to modern times. Yale University Press.

- Kessler, R. C., Chiu, W. T., Demler, O., Merikangas, K. R., & Walters, E. E. (2005). Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replications. Archives General Psychiatry. 62(6):617-27. [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R. C., Crum, R. M., Warner, L. A/, Nelson, C. B., Schulenberg, J., & Anthony, J. C. (1997). Lifetime co-occurrence of DSM-III-R alcohol abuse and dependence with other psychiatric disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives General Psychiatry. 54(4):313-21. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, S., Okuda, M., Hasin, D. S., Secades-Villa, R., Keyes, K., Lin, K-H., Grant, B., & Blanco, C. (2013.) Gender differences in lifetime alcohol dependence: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Alcohol: Clinical Experimental Research. 2013 Oct;37(10):1696-705. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- King, A. C., Bernardy, N. C., & Hauner, K. (2003). Stressful events, personality, and mood disturbance: gender differences in alcoholics and problem drinkers. Addictive Behaviors. 28(1):171-87. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merikangas, K. R., Mehta, R. L., Molnar, B. E., Walters, E. E., Swendsen, J. D., Aguilar-Gaziola, S., Bijl, R., Borges, G., Caraveo-Anduaga, J. J., DeWit, D., Kolody, B., Vega, W. A., Wittchen, H. U., & Kessler, R. C. (1998). Comorbidity of substances use disorders with mood and anxiety disorders: results of the International Consortium in Psychiatric Epidemiology. Addictive Behaviors. 23(6):893-907. [CrossRef]

- Powell, B. J., Penick, E. C., Othmer, E., Bingham, S. F., & Rice, A. S. (1982). Prevalence of additional psychiatric syndromes among male alcoholics. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1982 Oct;43(10):404-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penick, E. C., Powell, B. J., Nickel, E. J., Bingham, S. F., Riesenmy, K. R., Read, M. R., & Campbell, J. (1994). Co-morbidity of lifetime psychiatric disorder among male alcoholic patients. Alcohol: Clinical Experimental Research. 18(6):1289-93. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regier, D. A., Farmer, M. E., Rae, D. S., Locke, B. Z., Keith, S. J., Judd, L. L., & Goodwin, F. K. (1990). Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse. Results from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) Study. Journal of the American Medical Association. 264(19):2511-8. [PubMed]

- Smith, S. M., Stinson, F. S., Dawson, D. A., Goldstein, R., Huang, B., & Grant, B. (2006). Race/ethnic differences in the prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders: Results from the national Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychological Medicine. 36(7)987-98. Epub 2006 May 2. Erratum in: Psychol Med. 2008 Apr;38(4):606. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villumsen, A. L. (1970). Environmental factors in congenital malformations (H. Cowan, Trans.). F.A.D.L.s Forlag, Copenhagen.

- Weaver, T., Madden, P., Charles, V., Stimson, G., Renton, A., Tyrer, P., Barnes, T., Bench, C., Middleton, H., Wright, N., Paterson, S., Shanahan, W., Seivewright, N., & Ford, C. (2003). Comorbidity of substance misuse and mental illness in community mental health and substance misuse services. British Journal of Psychiatry. 183:304-13. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weissman, M. M., Myers, J. K., & Harding, P. S. (1980). Prevalence and psychiatric heterogeneity of alcoholism in a United States urban community. The Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 41(7):672-81. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, A.M. (2020). Gender differences in the epidemiology of alcohol use and related harms in the United States. Alcohol Research: Current Reviews 40 (2):01. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wu, L. T., Kouzis, A. C., & Leaf, P. J. (1999). Influence of comorbid alcohol and psychiatric disorders on utilization of mental health services in the National Comorbidity Survey. American Journal of Psychiatry. 156(8):1230-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zachau-Christiansen, B. (1972). Development during the first year of life (H. Cowan, Trans). Poul A. Andersens Forlag, Helsingor.

- Zilberman, M. L., Tavares, H., Blume, S. B., & el-Guebaly, N. (2003). Substance use disorders: sex differences and psychiatric comorbidities. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 48(1):5-13. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).