1. Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a serious and fast-spreading disease that affects people all over the world. It is a metabolic condition marked by elevated blood glucose levels that can cause serious side effects like renal failure, heart disease, blindness, and even amputations [

1]. Diabetes mellitus, which affects people of all ages, is the most prevalent chronic non-infectious condition globally and there has been a 3% annual increase in the prevalence of diabetes mellitus in children, and this trend is predicted to continue [

1]. For T1DM patients to keep their blood glucose levels within a target range and avoid problems, they must take insulin therapy for the rest of their lives and exercise caution [

2]. The essentials of managing type 1 diabetes are insulin delivery, carb counting, and blood glucose monitoring [

2].

According to certain research, there may be even greater regional and population-level variations in T1D incidence. For instance, studies on Inuit communities in Canada have shown that their risk of T1D is significantly greater than that of non-Indigenous Canadians, with differences of up to 12 times [

3]. Comparably, research from India revealed that some ethnic groups were far more likely than others to get Type 1 Diabetes. In fact, within their community, one group was four times more likely to have the disease than the other [

4]. These results show that geographic location and ethnicity can have a significant impact on the prevalence of Type 1 Diabetes. Worldwide distribution of this illness appears to be influenced by both genetic and environmental variables, while the reasons for these variances are still a mystery to experts.

Glycemic control may be impacted by family dynamics, which can also influence a child's attitude and approach to managing their diabetes. Encouraging children with type 1 diabetes to follow treatment regimens, dietary guidelines, and exercise schedules requires the support of their families [

5,

6]. The ADA recommends parents and caregivers educate themselves about T1DM, attending diabetes education classes, learning insulin administration, blood glucose interpretation, hypoglycemia/hyperglycemia signs, ketoacidosis treatment, and carbohydrate counting [

7].

Family-centered interventions have been found to have several advantages, such as improved compliance with medical recommendations [

8]. Furthermore, they can help to reduce parental anxiety, as well as to facilitate better communication between the healthcare team and the family [

8] . Teenagers who have greater levels of self-efficacy also tend to have higher levels of self-confidence and positive self-esteem. For people with diabetes, physical health plays a significant role in determining quality of life [

9,

10].

Therefore, this study purpose to determine if the Family Centered Empowerment Model can help adolescents with Type 1 Diabetes improve their HbA1c levels, self-efficacy, and quality of life.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Settings

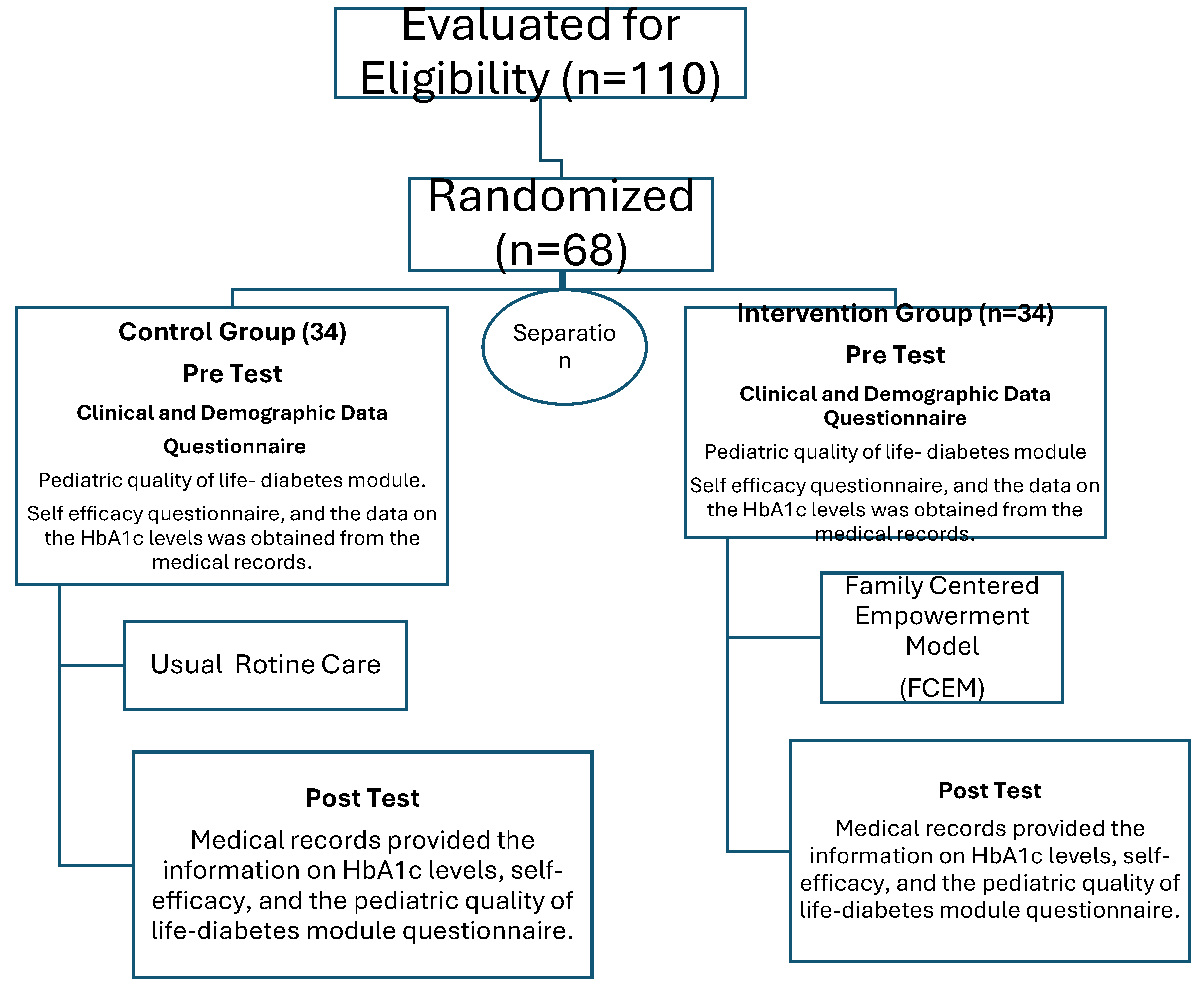

An experimental research design was carried out in Jordanian Royal Medical Services at diabetes and endocrine clinics, in Amman, Jordan. Between April and July 2023 (

Figure 1).

2.2. Study Population

This research included 68 participants with type 1 diabetes. Individuals aged 12 to 18 who had received a diagnosis at least six months prior and had not participated in any official diabetes education program up until one month before the study were included. Adolescents who had recently been diagnosed with type 1 diabetes and those with additional serious long-term illnesses were not included in the study. The intervention and control groups obtained from previous similar studies, pilot studies, or experiences [

11].

In this study, a 4-part research instrument was employed. The first section of the questionnaire was sociodemographic in nature, covering topics such as age, gender, school grade, age at diagnosis, educational background and employment of the parents, length of illness, number of daily injections, frequency of daily blood glucose checks, number of diabetes-related hospitalizations last year, and episodes of hypoglycemia reported last month. The Self-Efficacy Questionnaire, which had three subscales, was the second portion. The subscales were: academic self-efficacy (Items 1, 4, 7, 10, 13, 16, 19, and 22); social self-efficacy (Items 2, 6, 8, 11, 14, 17, 20, and 23); and emotional self-efficacy (Items 3, 5, 9, 12, 15, 18, 21, and 24). Eight components make up each subscale. The entire instrument consisted of 24 items, and each item was evaluated on a 5-point Likert scale, with a possible score range of 24 to 120 [

12]. A high score denotes a high degree of self-efficacy. The self-efficacy levels were therefore classified as low (less than 60%), moderate (between 60% and 80%), and high (more than 80%). The third section consisted of a questionnaire called the Pediatric Quality of Life-Diabetes Module. The twenty-eight items in this multidimensional tool are categorized into five domains: treatment obstacles (four items), treatment adherence (seven items), concern (three items), and diabetic symptoms (eleven items). For teenage self-report, a five-point Likert scale was employed, and total scores varied from 0 to 2800. The total number of questions divided by the total number of answers is how scale scores are calculated [

13]. Higher scores corresponded to improved quality of life. Medical records pertaining to the glucose control data comprised the fourth section.

Based on the concept, FCEM was put into practice over the course of four weeks, with four sessions that lasted each for 30 minutes. Adolescents and their families were arranged in a teaching group using smartphone applications prior to each session, and the lessons were conducted via sharing instructional materials and a video. All participants and their families participated in phone group sessions. For research samples in the case group, the four phases of the empowerment model—perceived danger, problem-solving, instructional involvement, and evaluation—were used to apply its contents. Perceived threat, which is comprised of perceived severity and perceived vulnerability, is the first stage. "Perceived severity" refers to the degree to which a person and their family recognize the dangers or difficulties associated with a sickness and believe that a condition is possible. The researcher intends to comprehend the issue using the study samples, provide answers, and put them into practice in the second stage, which is to increase self-efficacy. Third step: boosting self-esteem through instruction participation: Instruction participation was consistently provided in the first and second phases. Process and summative evaluations were part of the fourth step. During the process assessment, every session was assessed to guarantee the patient's subjective and practical involvement in the care plan and to confirm that they are adhering to the previously given instructions [

14]. The control group did not get any intervention in this area and just got standard treatment in the diabetic clinic.

2.3. Data Analysis

The data review was conducted using SPSS version 22. Initially, any necessary adjustments were performed once the data was examined for data entry problems. For descriptive data, the variables mean, percentage, and number were employed; steepness and skewness were assessed in relation to the scale data's normal distribution. The frequency distribution was employed for categorical variables, while the mean and standard deviation were used for continuous variables. The test known as the T-test was used for comparing means between a pair of continuous variables, while the Chi-square test was used to look at the connection between two categorical variables. Furthermore, the two independent sample t-test was employed to examine if there was a statistically significant difference between the experimental and control groups. We evaluated the relationship between glycemic control, SEQ, and QOL using the Pearson's correlation coefficient. A P-value of less than 0.05 indicated that the results were significant.

2.4. Ethical Considerations

This study was approved by The University's institutional review board (IRB) to carry out the study. The teenagers' and their families' informed consents were obtained.

3. Results

In the study Participating in the study were 68 teenagers with T1DM. Age (p = 0.000), weight (p = 0.006), and student level (p = 0.000) were the three categories in which there was a significant difference in the groups' mean scores. Based on maternal and paternal educational attainment, insurance, height, gender, and other factors, the statistical test findings revealed no statistically significant difference between the two groups. In addition, it shows that insulin injections were administered three times a day to both groups of T1DM patients, and most of the patients had type 1 diabetes mellitus for five years or more with no appreciable changes. A first-degree family history of diabetes mellitus was present in 26% of the intervention group and 6% of the control group, respectively, however most members of the two groups had just one hospitalization (

Table 1).

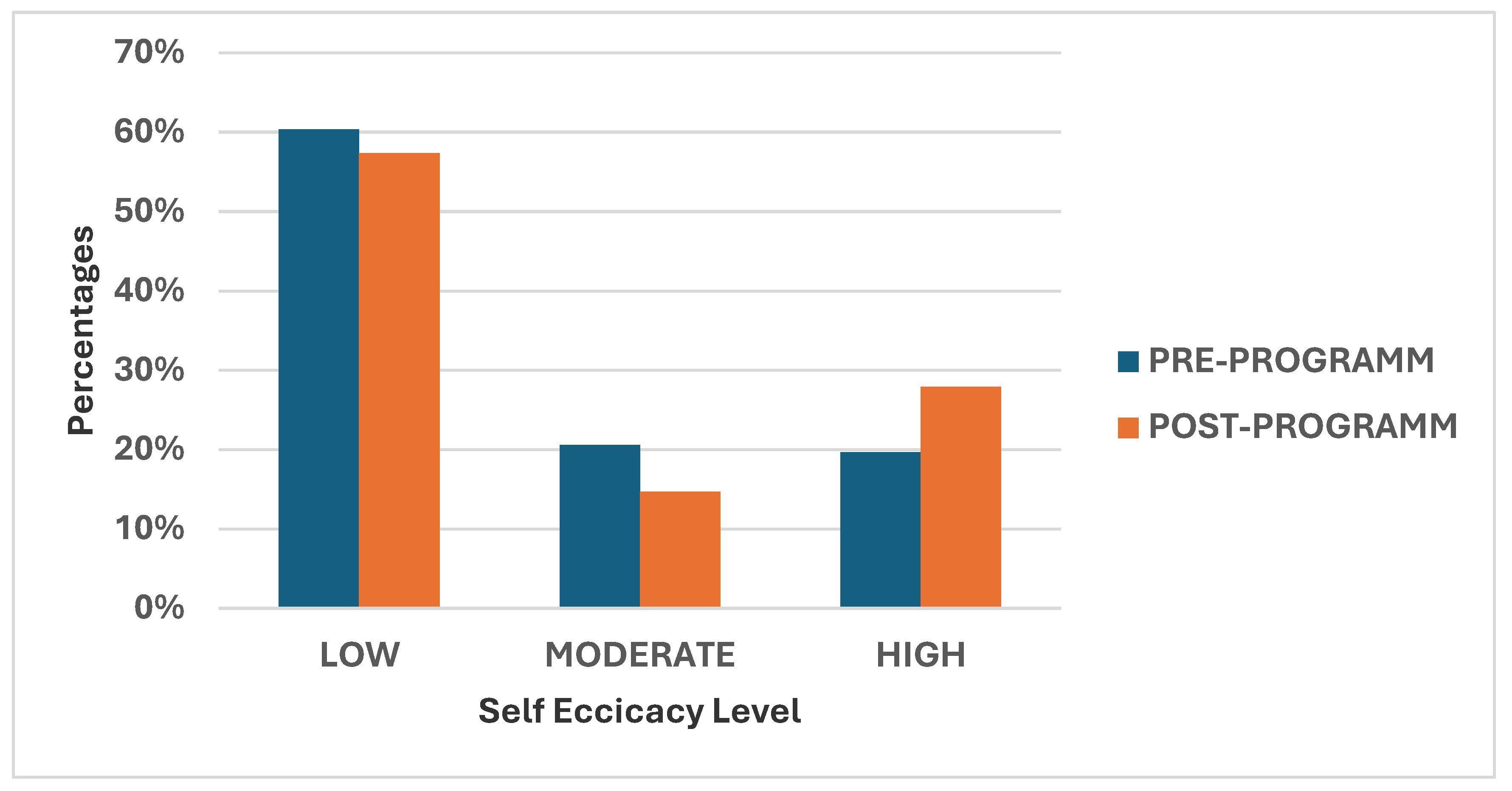

Table 2 showed that the mean score of the intellectual, social, and emotional self-efficacy categories within the intervention group changed significantly (p=0.000) from the pre-program period to the post-program follow-up assessment.

The majority of T1DM patients (60%) had low self-efficacy in the pre-program. However, 15% and over 27% of them, respectively, demonstrated moderate and high levels of self-efficacy in the post-program follow-up examination (

Figure 2).

When comparing the post-program follow-up evaluation to the pre-program phase,

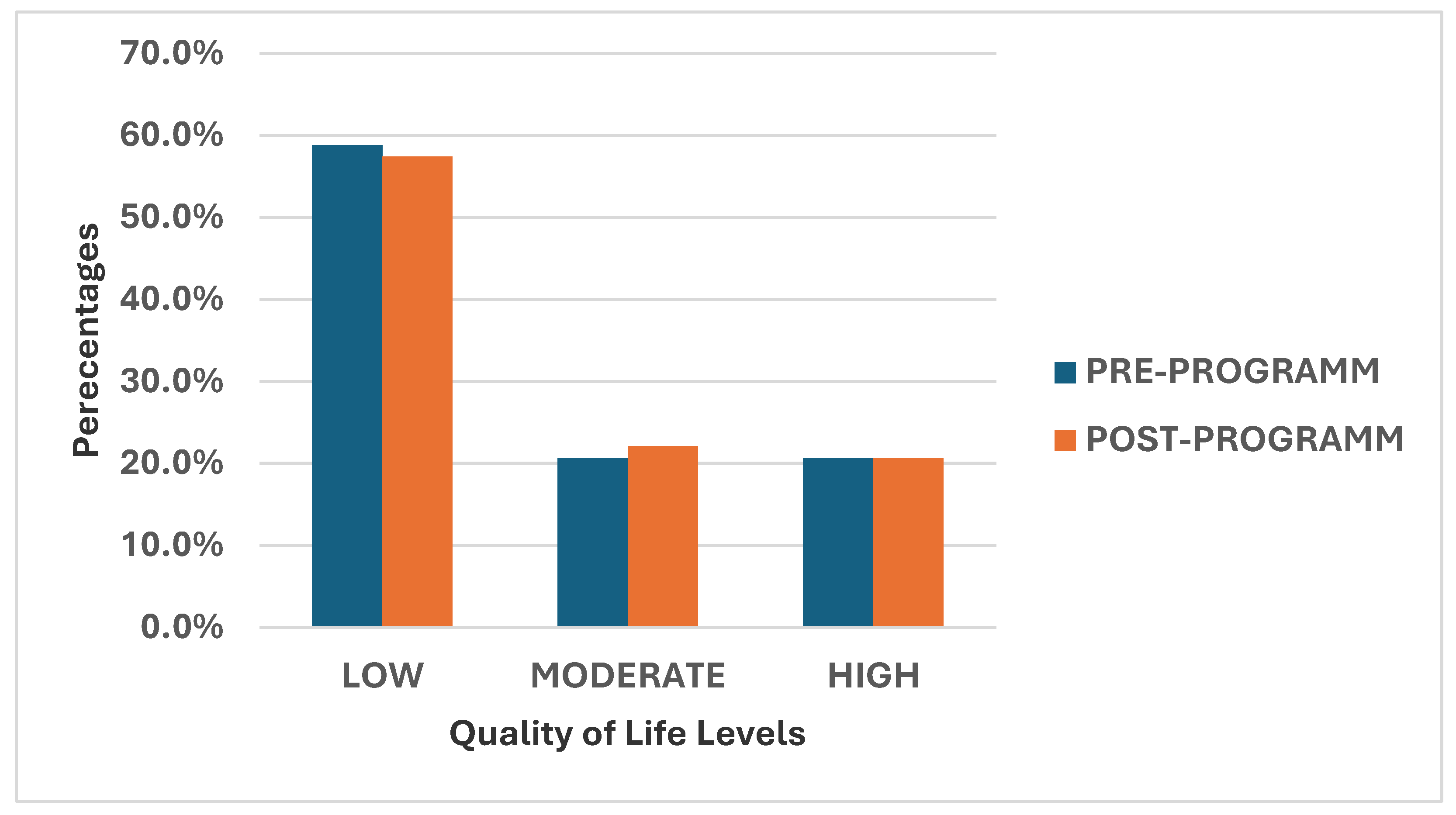

Table 3 shows a statistically significant variance in treatment barriers, treatment adherence, diabetes symptoms, communication, and stress. However, among the control group, there was no statistically significant difference in treatment barriers or diabetes symptoms between the pre- and post-program phases.

During the pre-program, 60% of T1DM patients reported having a terrible quality of life. In the post-program follow-up evaluation, however, 15% of them and more than 27% of them, respectively, reported moderate and high levels of quality of life (

Figure 3).

As shown in

Table 4. The independent t-test (p <0.001) indicated that prior to the family-centered education, the mean HbA1C value was statistically significant in both the intervention and control groups. After receiving family-centered education, the mean HbA1C score of the intervention group decreased significantly (p<0.001) compared to the control group. However, there was a statistically significant increase in the control group's difference between before and after family-centered schooling (p < 0.001).

There is a strong positive correlation between Self-efficacy Levels pre and posttest among intervention (P< 0.001), whereas there is a negative correlation between HbA1c and SEQ- levels posttest without significant values . In addition, there is a strong positive correlation between Quality of Life Pre-test and quality of Life posttest (P< 0.000) (

Table 5).

3. Discussion

The FCEM provides patients' families the tools they need to better understand their lifestyle issues, develop their patient support techniques, and alter their own living conditions. The FCEM can boost a patient's self-efficacy and self-esteem because it is linked to their self-participation. Studies have demonstrated a strong correlation between patients' better eating habits and their belief of self-efficacy [

15,

16].

The data show that family-centered education improved T1DM patients' adherence to therapy and HbA1c results. This shows that improving treatment compliance and health indicators may result from incorporating families in the educational process. A typical education program and an empowerment program vary primarily in that the former is a tactic or plan, while the latter is more of a manual for patients and healthcare personnel [

17]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study in Jordan to explore the effect of family centered empowerment model on quality of life, self-efficacy, and Hba1c levels in adolescents with type 1 diabetes.

The results of the current study indicated that most of the teenagers under investigation had poor levels of self-efficacy in their pre-transition educational programs. This may be because teenagers are still learning a lot of the skills required for self-managing their diabetes and realizing how important it is to have continuous assistance from their families in order to maintain good control of HbA1c level. Our findings were consistent with other research demonstrating the link between strong control of HbA1c level and high levels of self-efficacy.

Our study showed that the mean total score of self-efficacies enhanced better in the intervention group after the intervention, compared to that in the control group. This result is consistent with the assessment conducted by Gutierrez-Colina et al. on 44 young people with type 1 diabetes and discovered that the young adolescent had lower levels of self-efficacy at the baseline evaluation [

18]. In contrary, Survonen et al. found that found that the teenagers' self-efficacy level was good at the beginning of the assessment [

19].

The mean HbA1c level was lower in the intervention group six months after the intervention as compared to the control group, as the results showed. In a comparable direction, findings of study suggest that boosting problem-solving skills and self-efficacy might help improve self-management, which in turn can improve glycemic control [

20]. In addition, another state that teenagers with type 1 diabetes mellitus who also have higher levels of self-efficacy are more likely to reach their diabetes management goals [

21].

Additionally, this finding is in accordance with research which showed that HbA1c levels were lowered by diabetes patients and their families being empowered in home-centered care [

22]. The empowerment model's contribution to greater increases in hemoglobin levels appears to be dependent on family engagement, as evidenced by the comparison of intervention and control groups. It makes sense that those with lower HbA1c levels would follow healthy diets and adjust their eating habits.

The results of this study indicate that while young people with type 1 diabetes may have difficulties in handling treatment requests from their parents, it might be advantageous for them to have parental participation in order to improve their quality of life specifically connected to diabetes. This may be explained by the fact that educational program enhances teenagers' capacity to their illness and capacity to handle stressful life situations. This result agrees with study that evaluated the impact of self-reported chronic-generic and condition-specific quality of life (QoL) on glycemic control among adolescents and showed that QoL was inversely associated with HbA1c after 3 years in the course of T1D only in patients poorly controlled at baseline [

23].

A significant relationship between glycemic control and quality of life was found in a study including 240 diabetic Emirati individuals. In particular, negative correlations are shown between the glycated hemoglobin percentage and each QoL subdomain [

24].

Research found that there is no discernible relationship between adolescents with chronic illnesses' quality of life and their overall preparedness for the move to adult care [

25]. While another one they highlight the complexity and diversity of factors affecting the transition experiences and quality of life in teenagers with chronic conditions [

26].

Several investigations have looked into the findings point to the potential significance of raising self-efficacy for raising overall quality of life in people with Type 1 DM, as there appears to be a significant correlation between the total self-efficacy and total quality of life at both short- and long-term assessments post-program.

In a prior study, Ayar et al. found that while the web-based diabetes education program had no effect on A1C levels, it was helpful in raising the self-efficacy and quality of life of diabetic teenagers. Furthermore, they discovered that the intervention group's self-efficacy levels were higher than those of those receiving only standard care. Improving self-efficacy in teenagers with type 1 diabetes is crucial for encouraging positive changes in their behavior related to optimal self-management. The adolescents with T1DM in the intervention group and the control group had significantly different QOL Mean Scores [

27].

3.1. Strength and Limitation

The current study had some limitations. First, there were just 68 participants in the sample, and they were all from the same medical facility. This might restrict how far the findings can be applied. Secondly, the brief follow-up time is recognized as a research design weakness. The complaint of the little follow-up time emphasizes how essential it is for research projects to take the length of the observation into account. A longer follow-up time is frequently required to make more firm conclusions on the long-term impact and efficacy of treatments in healthcare research, even if short-term outcomes might still provide valuable information. However, to our knowledge the main strength of our study, it is the first ever study conducted in Jordan to assess Effect of Family Centered Empowerment Model on Quality of Life, Self-Efficacy, and HbA1c levels in Adolescents with Type 1 Diabetes. When compared to other study designs, this case-control study has several advantages. They are, by contrast, easy, quick, and inexpensive.

4. Conclusions

our findings suggest that patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus should incorporate continuous care education sessions into regular clinic appointments with a focus on follow-up to evaluate the disease's long-term consequences. Planning programs for diabetic patients to get ready for the transition to adult care should take their self-efficacy and quality of life into consideration.

Since patients with type 1 diabetes showed lower HbA1c level after receiving self-care training, nurses should incorporate this sort of training into patients' treatment plans to provide them the knowledge they need to improve their health. Improve the quality of life for all diabetic children and adolescents by holding educational programs for children and their parents to raise awareness of and adherence to diabetes care recommendations.

5. Implications for Nursing Practiceand Policy

This study delves into the implications for nursing and health policy arising from the influence of family-centered empowerment on Jordanian adolescents with Type 1 Diabetes (T1DM). The primary focus is on the measurable outcomes of HbA1c levels, self-efficacy, and quality of life (QOL) in this specific demographic. By examining these factors, the research aims to contribute valuable insights that can inform nursing practices and health policies to better support adolescents with T1DM in Jordan.

This research aims to provide evidence-based insights into the implications of family-centered empowerment on Jordanian adolescents with T1DM. The findings will contribute to the development of targeted nursing interventions and informed health policies, ultimately improving the well-being and outcomes for this specific population.

References

- Miolski, J.; Ješić, M.; Zdravković, V. Complications Of Type 1 Diabetes Melitus In Children. Medicinski Podmladak, 2020,71(4), 49–53.

- Patterson, C. C.; Karuranga, S.; Salpea, P.; Saeedi, P.; Dahlquist, G.; Soltesz, G.; Ogle, G. D. Worldwide estimates of incidence, prevalence and mortality of type 1 diabetes in children and adolescents: Results from the International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas, 9th edition. Diabetes research and clinical practice.2019, 157, 107842.

- Zhang, R.; Cai, X. L.; Liu, L.; Han, X. Y.; Ji, L. N. Type 1 diabetes induced by immune checkpoint inhibitors. Chinese Medical Journal, 2020,133(21), 2595-2598.

- Das A., K. Type 1 diabetes in India: Overall insights. Indian journal of endocrinology and metabolism, 2015, 19(Suppl 1), S31–S33.

- McCarthy, M. M.; Whittemore, R.; Gholson, G.; Grey, M. Self-management of physical activity in adults with type 1 diabetes. Applied nursing research.2017, ANR, 35, 18–23.

- Zysberg, L.; Lang, T. Supporting parents of children with type 1 diabetes mellitus: A literature review. Patient Intelligence, 2015, 21-31.

- American Diabetes Association. 13. Children and adolescents: standards of medical care in diabetes−2020. Diabetes Care.2020,43(Suppl1):S163-S182.

- Elsbach, K. D.; van Knippenberg, D. Creating high-impact literature reviews: An argument for ‘integrative reviews’. Journal of Management Studies, 2020, 57(6), 1277-1289.

- Ebrahimi Belil, F.; Alhani, F.; Ebadi, A.; Kazemnejad, A. Self-Efficacy of People with Chronic Conditions: A Qualitative Directed Content Analysis. Journal of clinical medicine, 2018, 7(11), 411.

- Aljawarneh, Y. (2018). Associations Between Physical Activity, Health-Related Quality Of Life, Regimen Adherence, And Glycemic Control In Jordanian Adolescents With Type 1 Diabetes.

- Kang, S. L.; Hwang, Y. N.; Kwon, J. Y.; Kim, S. M. Effectiveness and safety of a model predictive control (MPC) algorithm for an artificial pancreas system in outpatients with type 1 diabetes (T1D): systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetology & metabolic syndrome, 2022, 14(1), 187.

- Muris, P. A brief questionnaire for measuring self-efficacy in youths. Journal of Psychopathology and behavioral Assessment, 2001, 23, 145-149.

- Varni, J. W.; Burwinkle, T. M.; Jacobs, J. R.; Gottschalk, M.; Kaufman, F.; Jones, K. L. The PedsQL in type 1 and type 2 diabetes: reliability and validity of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory Generic Core Scales and type 1 Diabetes Module. Diabetes care, 2003, 26(3), 631–637.

- Ghaljaei, F.; Motamedi, M.; Saberi, N.; ArbabiSarjou, A. The Effect of the Family-Centered Empowerment Model on Family Functioning in Type 1 Diabetic Children: A Quasi-Experimental Study. Medical-Surgical Nursing Journal, 2022, 11(2).

- Madmoli, M. A systematic review study on the results of empowerment-based interventions in diabetic patients. International Research in Medical and Health Sciences,2019, 2(1), 1-7.

- Mohebi, S.; Azadbakht, L.; Feizi, A.; Sharifirad, G.; Kargar, M. (2013). Review the key role of self-efficacy in diabetes care. Journal of education and health promotion, 2013, 2, 36.

- Rezasefat Balesbaneh, A.; Mirhaghjou, N.; Jafsri Asl, M.; Kohmanaee, S.; Kazemnejad Leili, E.; Monfared, A. Correlation between self-care and self-efficacy in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Journal of Holistic Nursing And Midwifery, 2014,24(2), 18–24.

- Gutierrez-Colina, A. M.; Corathers, S.; Beal, S.; Baugh, H.; Nause, K.; Kichler, J. C. Young Adults With Type 1 Diabetes Preparing to Transition to Adult Care: Psychosocial Functioning and Associations With Self-Management and Health Outcomes. Diabetes spectrum : a publication of the American Diabetes Association, 2020, 33(3), 255–263.

- Survonen, A.; Salanterä, S.; Näntö-Salonen, K.; Sigurdardottir, A. K.; Suhonen, R. (2019). The psychosocial self-efficacy in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Nursing open, 2019, 6(2), 514–525.

- Chen, C. Y.; Lo, F. S.; Shu, S. H.; Wang, R. H. Pathways of emotional autonomy, problem-solving ability, self-efficacy, and self-management on the glycemic control of adolescents with type 1 diabetes: A prospective study. Research in Nursing & Health, 2021, 44(4), 643-652.

- Chih, A. H.; Jan, C. F.; Shu, S. G.; Lue, B. H. (2010). Self-efficacy affects blood sugar control among adolescents with type I diabetes mellitus. Journal of the Formosan Medical Association = Taiwan yi zhi, 2010,109(7), 503–510.

- Cheraghi, F.; Shamsaei, F.; Mortazavi, S. Z.; Moghimbeigi, A. The Effect of Family-centered Care on Management of Blood Glucose Levels in Adolescents with Diabetes. International journal of community based nursing and midwifery,2015, 3(3), 177–186.

- Stahl-Pehe, A.; Landwehr, S.; Lange, K. S.; Bächle, C.; Castillo, K.; Yossa, R.; Lüdtke, J.; Holl, R. W.; Rosenbauer, J. Impact of quality of life (QoL) on glycemic control (HbA1c) among adolescents and emerging adults with long-duration type 1 diabetes: A prospective cohort-study. Pediatric diabetes, 2017,18(8), 808–816.

- Al-Abadla, Z.; Elgzyri, T.; Moussa, M. The Effect of Diabetes on Health-Related Quality of Life in Emirati Patients. Dubai Diabetes and Endocrinology Journal, 2022; 28(1), 35-44.

- Gangemi, A.; Abou-Baker, N.; Wong, K. Evaluating the quality of life and transition of adolescents and young adults with asthma in an inner city. Medical Research Archives, 2020, 8(1).

- Uzark, K.; Afton, K.; Yu, S.; Lowery, R.; Smith, C.; Norris, M. D. Transition Readiness in Adolescents and Young Adults with Heart Disease: Can We Improve Quality of Life?. The Journal of pediatrics,2019, 212, 73–78.

- Ayar, D.; Öztürk, C.; Grey, M. The effect of web-based diabetes education on the metabolic control, self-efficacy and quality of life of adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus in Turkey. J Pediatr Res, 2021, 8, 131-138.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).