1. Introduction

Petroleum plastics are used for various types of applications such as food packaging, household utensils, automotive industry, medical products [

1]. However, such materials have a long degradation time, which can compromise the environment [

2]. Thus, new alternatives are needed to reduce the use of petroleum plastics. Among these alternatives there are natural polymers that are widely found in nature [

3]. Natural polymers or biopolymers are generally referred to polymers derived from biomass, represented mainly by cellulose, chitosan, lignin, starch, and polypeptide [

4]. In addition to its wide availability, biopolymers have characteristics such as biodegradability, low cost and are considered environmentally friendly [

5]. In the spectrum of biopolymers, starch is an alternative polymer to petroleum plastics [

6].

Starch is a biodegradable polymer [

7,

8,

9,

10] produced by plants; starch acts as an energy reserve and may be a promising material for producing biodegradable plastics due to its availability, low cost and status as a renewable material [

11,

12,

13,

14]. Chemically, starch is formed by two polysaccharides—amylose and amylopectin—in different proportions depending on the starch, which may influence the mechanical properties of the material [

15,

16,

17]. Amylose is a glucose polymer either with a linear chain or with few branches; 20 to 30% of the starch is amylose. Amylopectin is a highly branched polymer of glucose that accounts for approximately 70–80% of starch [

10,

18].

Native starch is not a true thermoplastic, which prevents its use to replace petroleum plastic, because it has strong intermolecular and intramolecular bonds, increasing its melting point to a value higher than the degradation temperature, limiting its processability and applications [

19,

20]. However, in the presence of plasticizers and high temperatures, gelatinization occurs, in which the three-dimensional structures of native starch rupture; under controlled conditions, this rupture leads to the formation of a homogeneous amorphous material known as thermoplastic starch (TPS), which is a starch-plasticized material that is essential for producing some starch-based materials [

21,

22,

23].

One of the main roles of plasticizers is to increase the flexibility and handling properties of films [

24]; glycerol is the most common plasticizer (in addition to water) [

25,

26,

27,

28], due to the large number of hydroxyl groups present in its structure [

29]. Glycerol is a water-soluble hydrophilic plasticizer used to overcome the brittleness characteristics of films by reducing the intermolecular forces between their chains [

30,

31].

Cellulose nanofibers may have good mechanical properties when used in TPS; additionally, cellulose nanofibers are materials of plant origin that are normally obtained from lignocellulosic plants [

32]. Chemical treatment is a primary treatment for obtaining these materials, specifically through alkaline and acid hydrolysis treatments, which aim to remove some of the amorphous compounds present in the fibers [

33,

34].

Sisal (

Agave sisalana) is a species of hydrophilic plant present in the Brazilian Amazon. Sisal leaves are hard and erect, with flat surface, and sisal fruit is similar to pineapple; however, farmers are interested in its fibers [

35,

36]. These fibers are considered some of the most efficient for polymer reinforcements; in addition, their availability in some countries is advantageous and provides the opportunity for their use in developing biocomposites [

37].

Several studies using natural fibers to fabricate polymer matrix composites have been conducted. Islam et al., investigated the effect of adding

Moringa Oleifera fibers to poly (lactic acid) (PLA) on the mechanical properties of the composites. Extrusion, injection, and compression techniques were used to fabricate the composites, they found for these materials an increase of 33 and 44% in tensile stress in relation to PLA [

38]. Akindoyo et al., observed that oil palm empty fruit bunch fibers modified with poly(dimethyl siloxane) promoted an increase in tensile strength, tensile modulus, flexural strength, and flexural modulus for composites for composites with PLA in relation to the polymeric matrix [

39]. Beg et al., reported that polyamide 6.10 composites with microcrystalline cellulose fibers treated with Exxelor VA1803 exhibited better mechanical and thermomechanical properties than composites obtained with fibers treated with Bondyram 7103 [

40]. Chandrasekar et al., extracted starch, nanocellulose and bioactive compounds from banana peel, the extracted products were used to manufacture nanocomposite films [

41]. They found that addition of nanocellulose derived from banana peel promoted a 6-fold increase in tensile stress for nanocomposite films. Jumaidin et al., have reported an increase in tensile stress for thermoplastic cassava starch composites with 1.3, and 5% coconut grass fiber [

42].

Thus, the objectives of this study were to obtain sisal nanofibers using sulfuric acid at a concentration lower than that of conventional treatments (ranging from 60 to 65%), to produce corn starch films and to evaluate the behaviors of the nanofibers as reinforcing agents at different concentrations to evaluate their influences on the mechanical performance levels of the material produced.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Commercial corn starch from Maizena® was used to produce the films, and glycerol 80% from Pharmapele was used as plasticizer. Sodium hypochlorite and sodium hydroxide were supplied by Ypê and Dinâmica, respectively. Sulfuric acid was supplied by Dinâmica.

2.2. Preparations of Sisal Nanofibers

The sisal fibers underwent mechanical defibrillation and were ground in a Model MA048 Marconi Willey knife mill, reaching a length of approximately 0.50 mm. Alkaline treatment and bleaching were used to remove amorphous components of the sisal fibers. This removal facilitated the penetration of the acid solution during hydrolysis. In the alkaline treatment of the sisal fibers, a 5% (w/v) NaOH solution was prepared. The ground fibers were treated in NaOH solution (5% w/v) for 1 hour at 80 °C in a water bath under mechanical agitation; the fibers were filtered, neutralized with distilled water (pH of approximately 7) and dehydrated in an oven at 35 °C for 24 hours. In the bleaching process, the fibers were immersed in 1% NaClO solution (v/v), washed with distilled water, filtered under vacuum and dehydrated in an oven with air circulation at 35 °C for 24 hours. The role of acid hydrolysis is to remove as much of the cellulose-forming amorphous domains as possible. The bleached fibers were subjected to acid hydrolysis in H2SO4 solution (50% v/v) under 1 hour of mechanical agitation in a water bath at 55 °C. Then, 100 mL of distilled water was added to every 1 g of fiber to interrupt the hydrolysis reaction. The resulting suspension was subjected to successive centrifugation for 20 minutes at 8000 rpm (discarding the supernatant) until it reached the pH of water. The fibers were then ultrasonicated for 25 minutes and stored in the refrigerator to prevent the proliferation of fungi.

2.3. Preparation of Thermoplastic Starch Nanocomposite Films with Sisal Nanofibers

The thermoplastic starch and nanocomposites films were processed according to a casting technique. A film-forming solution was prepared by adding corn starch in distilled water (1:20 m/v). Glycerol was used as a plasticizing agent at concentrations of 18, 28 and 36% relative to the mass of the starch, which was subsequently homogenized and heated to approximately 85 °C until the gel point. The solution was filled into silicone molds and dehydrated in an oven at 35 °C for 24 hours. For the nanocomposite films, the same procedure was used with the addition of 1 and 3 % sisal nanofibers in relation to the mass of starch.

Table 1 presents the composition of the films obtained by solvent casting technique.

Figure 1 displays a scheme for the methodology used to obtain nanocomposites films in our investigation.

2.4. Chemical Characterization of the Sisal Fibers

The analysis methods used characterized the sisal fibers as neutral detergent insoluble fibers (NDFs) and acid detergent insoluble fibers (ADFs) [

43].

2.5. Film Thickness

The measurements were based on Nunes et al. [

44], in which five random points were measured around the specimens with a digital micrometer.

2.6. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

The sisal fibers and TPS were analyzed using a Hitachi TM3000 scanning electron microscope operating with 5 kV beams. The samples were adhered to aluminum supports with carbon tape and inserted into the SEM equipment.

2.7. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

Morphological characterization of the nanofiber suspension was performed with a Zeiss Leo 906 transmission electron microscope operating with an accelerating voltage of 80 kV. Before analysis, the samples were stained with tungstophosphoric acid solution (2%) for 30 seconds and dehydrated with the aid of filter paper.

2.8. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

X-ray diffraction analyses were performed using a Model D8 ADVANCE X-ray diffractometer (Bruker). The equipment operated with a voltage of 40 kV and a current of 40 mA. The acquisition time per point was 1 s, with a step of 0.02° and a wavelength of CuKα1 = 1.54 Å. Crystallinity was obtained by peak deconvolution using a Gaussian function, and the diffraction pattern of the sisal nanofiber was fitted by Rietveld refinement.

2.9. Mechanical Tensile Test

The mechanical properties of T and NCs with plant nanofibers were evaluated according to the ASTM D882-02 standard in a WDW 100E universal mechanical testing machine with a tensile speed of 10 mm/s and an initial distance between jaws of 50 mm.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Chemical Analysis of Sisal Fibers

In

Table 2, the results of the α-cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin contents of the sisal fibers are presented before treatment as crude fibers and after alkaline and bleaching chemical treatments. According to a comparison of the results of the treated and crude fibers, there were considerable increases in the percentage of cellulose and reductions in the percentages of hemicellulose and lignin. This result indicated that the chemical treatments of the sisal fibers had positive effects; this finding was expected because the purpose of the acid hydrolysis treatment was to purify the cellulose by eliminating some of the surface materials (hemicellulose, lignin and waxes) that could interfere with the cellulose drying process.

The percentages of hemicellulose and lignin obtained in this study (

Table 2) were relative to those found by some researchers, as presented in

Table 3. The study by Teodoro et al. [

45] presented hemicellulose values similar to those of this study. The results for the percentages of hemicellulose and lignin showed significant differences relative to the results obtained in this study; Faruk et al. [

46] emphasized that different factors, such as climatic conditions, age and degradation, influenced both the chemical compositions and structures of the fibers. The cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin and cellulose contents extracted from five sources (wheat straw cellulose, sugarcane cellulose, cornstalk cellulose, bamboo cellulose and rice bran cellulose) were determined after alkali treatment, sodium hypochlorite and acetic acid treatment. The authors found cellulose contents close to 90% for the five celluloses, they stated that this content was attributed to the success of the chemical treatment used, which removed lignin, hemicellulose and waxes from the raw fibers [

47]. These results are slightly higher than ours. Our findings are in good agreement with those found for oil palm empty fruit bunch fiber and banana fibers after alkaline treatment and bleaching [

48,

49]. Our results indicate the success of the alkaline treatment and bleaching used for sisal fibers in our investigation.

3.2. Effects of Alkaline Treatment and the Scanning Electron Microscopy of Sisal Fibers

To observe the effects of the alkaline treatment on the fiber surface, comparisons were performed on the macroscopic and microscopic scales, as shown in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3, respectively.

Figure 2 illustrates the ground sisal fibers (A) treated with sodium hydroxide solution and bleached with sodium hypochlorite solution (B). When observing the physical aspects of the bleached fibers, discoloration is found in relation to the fiber characteristics before treatment. To complement and reinforce the differences resulting from the treatment, scanning electron microscopy was performed on the fibers; it was observed that the alkaline treatment successfully removed much of the material, especially lignin and hemicellulose, that were present in the fiber structure.

The morphologies of the longitudinal surfaces of the fibers before and after bleaching are shown in

Figure 3. For the red demarcations, in the fibers without alkaline treatment, the bundles joined by the nonfibrous components (lignin and hemicellulose) form microfibril structures that are less exposed. However, with chemical treatment, most of these components around the bundles are removed. These SEM results are corroborated by the cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin values found for chemically treated sisal fibers (

Section 3.1), which demonstrate the increase in cellulose content after alkaline treatment and bleaching. Similar results were reported for chemically treated fibers of: sisal [

53], coconut [

54],

Furcraea foetida [

55], and

Bauhinia vahlii [

56].

3.3. SEM of TPS

Scanning electron microscopy is performed on the thermoplastic starches to observe any imperfections in the formed films and the influences of the percentage of plasticizer in their production. Initially, it is observed that many starch granules do not melt; with increasing glycerol concentration, the number of starch granules decreases, as shown in

Figure 4.

Figure 4 shows the images of the samples obtained by SEM with concentrations of 18, 28 and 36% glycerol in relation to the starch mass. Note that the film with the lowest glycerol content has several starch particles (white dots) that do not plasticize during the gelatinization process. However, with increasing concentrations of glycerol, a considerable decrease in the amount of these particles is observed. This phenomenon indicates an incomplete reaction in the formation of the film and consequent influences on the mechanical performance, especially regarding elongation, as observed in

Figure 9. In other words, at lower plasticizer concentrations, large amounts of unreacted granules appeared; their presence promotes the formation of more rigid films (slightly flexible) that gain more flexibility with the increase in the plasticizer concentration. Similar reports were described for the plasticization of arrowroot starch with 15, 30 and 45% glycerol [

57]. Yang et al., also observed similar results for the surface morphology of plasticized corn starch films with different contents of sucrose-based ionic liquid crystal [

58]. Likewise, Khoi et al., report that Vietnamese arrowroot starch films with 40% glycerol exhibited a smoother surface morphology than films with 30, 20 and 10% glycerol [

59]. Our SEM results indicate the success for the plasticization of starch with glycerol.

3.4. Suspension and TEM of Sisal Fibers.

The suspension of sisal nanofibers is analyzed by transmission electron microscopy, and the morphological characteristics of their structures (elongated and thin) are observed to be as reported in the literature.

Figure 5 shows the images of the suspension and the micrograph obtained by TEM of a drop of the sample. A relatively stable suspension is obtained after hydrolysis with sulfuric acid. This stability may occur due to the presence of sulfate groups on the cellulose surface, which produce a negative repulsion between the nanofibers that form the stable suspension [

60]. Nanocrystals are obtained using a lower acid concentration (approximately 15% less, representing a 23% reduction in acid) than the conventional amount, which is in the range of 64 to 65% [

61]. The amorphous fraction of sisal fiber can be eliminated by acid hydrolysis where the crystalline region is preserved, resulting in the formation of nanorod-shaped nanofibers [

61]. Regarding the morphology, the nanocrystals or whiskers of cellulose have elongated shapes similar to needles or rods, as portrayed by Ng et al. [

62], Adel et al. [

63] , Correa et al. [

64], and Chen et al. [

60].

3.5. XRD

Figure 6 shows the X-ray diffraction pattern of the cellulose nanofiber adjusted by Rietveld refinement. The crystal structure input data used in the refinement are from Nishiyama et al. [

65]. The reliability factors obtained after refinement are Rwp = 0.0187 and χ² = 1.12 for the goodness of fit test. The cellulose nanofiber sample exhibits triclinic symmetry and has a P1 space group, with lattice parameters a = 10.3(2) Å, b = 6.62(6) Å, c = 5.96(6) Å, α = 79.8(5) °, β = 116.1(8) °, γ = 116.4(6)°, and volume = 328.0(5) ų. According to the quality of fit that is calculated and based on the standard data, the cellulose nanofiber sample has a type Iα crystalline structure [

65]. A similar result was observed for microcrystalline cellulose [

66]. On the other hand, type Iβ cellulose was observed for cellulose nanofibers from Tinwa bamboo leaves [

67], microporous cellulosic sponge from

Gleditsia triacanthos pods functionalized with

Phytolacca americana fruit extract [

68], and cellulose nanocrystals [

69].

The relative crystallinity characteristics of the fibers are calculated before being subjected to chemical treatments to observe the increase in the crystallinity index after each treatment, as shown in

Figure 7.

Alkaline, bleaching and acid hydrolysis treatments are directly reflected in the increase in fiber crystallinity. First, alkaline and bleaching treatments remove large parts of surface materials with amorphous characteristics. Second, in the acid hydrolysis process, the disordered cellulose phase that represents the amorphous region of the material is destroyed, preserving its crystalline domains.

Figure 7 shows the results obtained by peak deconvolution applied to the diffraction patterns of untreated sisal fibers, sisal fibers with alkaline treatment, sisal fibers with alkaline and bleaching treatments, and nanofibers. For each analysis, the crystallinity indices (Ic), coefficients of determination (r

2) and the areas of the crystalline and amorphous peaks are highlighted. The crystallinity index found for the untreated fiber (

Figure 7A) is 61.06%, which is very close to the value found by Teodoro et al. [

45]; these researchers obtained 60% crystallinity for sisal fibers. Ic values around 60% were determined for crude fibers [

56]. The crystallinity result of the sisal fibers after the alkaline treatment (

Figure 7B) reveals that there is an increase in the crystallinity of the material relative to the raw fibers. These results reinforce the efficiency of the treatment that provides surface cleaning, removing amorphous materials from the fibers. These results are corroborated by the IC calculation after alkaline treatment for the fibers: Curauá [

70],

Coccinia grandis.L. [

71]

, Acacia planifrons bark [

72], and Jute [

73].

From

Figure 7C, it is observed that the crystallinity index for the fiber with alkaline treatment followed by bleaching is lower than that of the fiber applying only the alkaline treatment (

Figure 7B). This fact reveals that the bleaching conditions performed on the sisal fibers, despite having provided surface cleaning, may have affected some of the crystalline domains of the material.

The crystallinity index of the sisal nanofiber is 84.44% (

Figure 7D). Teodoro et al., when using different nanofiber extraction conditions, obtained crystallinity values that range between 78 and 82% [

45]. The increase in peak intensity at 2θ = 15.24°, which consequently increases the crystallinity of the material; this phenomenon reinforces the efficiencies of the conditions under which acid hydrolysis is employed, which allow high purity indices in the nanocrystals and preserve their state (cellulose Iα) [

74]. Our results for Ic indicate the success of the chemical treatment used to obtain sisal nanofibers, which provided the removal of most of the amorphous material present in the raw fibers.

3.6. Film Thickness

Table 4 shows the film thicknesses with their respective standard deviations. With the addition of the reinforcing agent, there was an increase in the thickness of the films. Such results were already expected because, even at relatively low concentrations, materials tend to occupy spaces proportional to their volume, even those on the nanometer scale. For some situations, thicker films tend to exhibit higher tensile stress values. In these cases, there are: a denser matrix and an effective interaction between the matrix chains, which is an obstacle to film rupture

[75]. However, in our investigation the range of variation for thickness is considered discrete, which is indicative of the low influence of thickness on tensile stress tests.

3.7. Tensile Stress Test

The mechanical tensile stress and elongation performance levels of the films with and without nanofibers and with variations in the plasticizer concentration are evaluated.

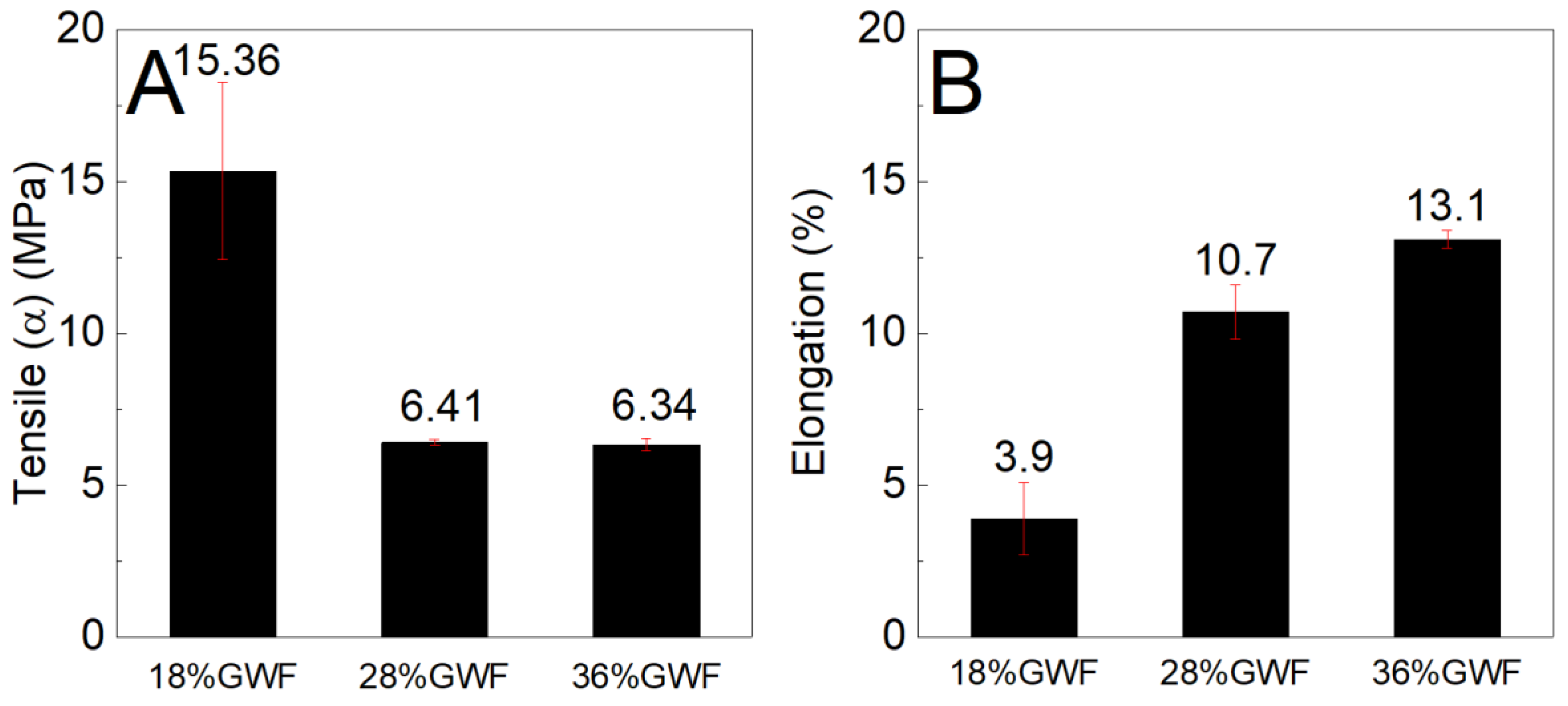

Figure 8 shows the tensile stress and elongation results of the corn starch films with concentrations of 18, 28 and 36% glycerol in relation to the dry mass of starch. The influence of the plasticizer on the mechanical results is remarkable because the film with a low glycerol concentration has a high tensile strength (approximately 15.36 MPa). With increasing concentrations of glycerol, there is a reduction in tension, indicating that the influence of glycerol content increases the reduction in mechanical strength. These results can be explained by the decrease in hydrogen bonds between the starch chains after the insertion of glycerol. These findings are consistent with those reported by Vilhena et al, where it was reported that the increase in glycerol content decreases tensile stress, due to glycerol acting by relieving the hydrogen bonds that occur in starch chains [

76]. In addition, glycerol forms hydrogen bonds with the starch chains, thus reducing the interaction between the polymer chains. Plasticizers with a lower molar mass (such as glycerol), provide a good plasticization of starch due to the weakening of intermolecular interactions between starch macromolecules, which reduces stress tension [

57]. Tarique et al., have also reported that an increase in glycerol content reduces tensile stress, due to glycerol decreasing hydrogen bonds between polymer chains [

57]. However, analyzing the elongation shows that there is an increase in elongation as the percentage of glycerol increases

This increase in elongation was attributed to the decrease in hydrogen bonds between the starch chains after the addition of the plasticizer [

59]. This behavior after starch plasticization with glycerol is consistent with the study by Xie et al. [

77]. In this study they found that higher levels of glycerol and ionic liquid 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate provided an increase in the elongation of starch films. Wang et al., also reported that the use of a higher content of polymeric ionic liquid, as a starch plasticizer, increased the elongation of plasticized films [

78].

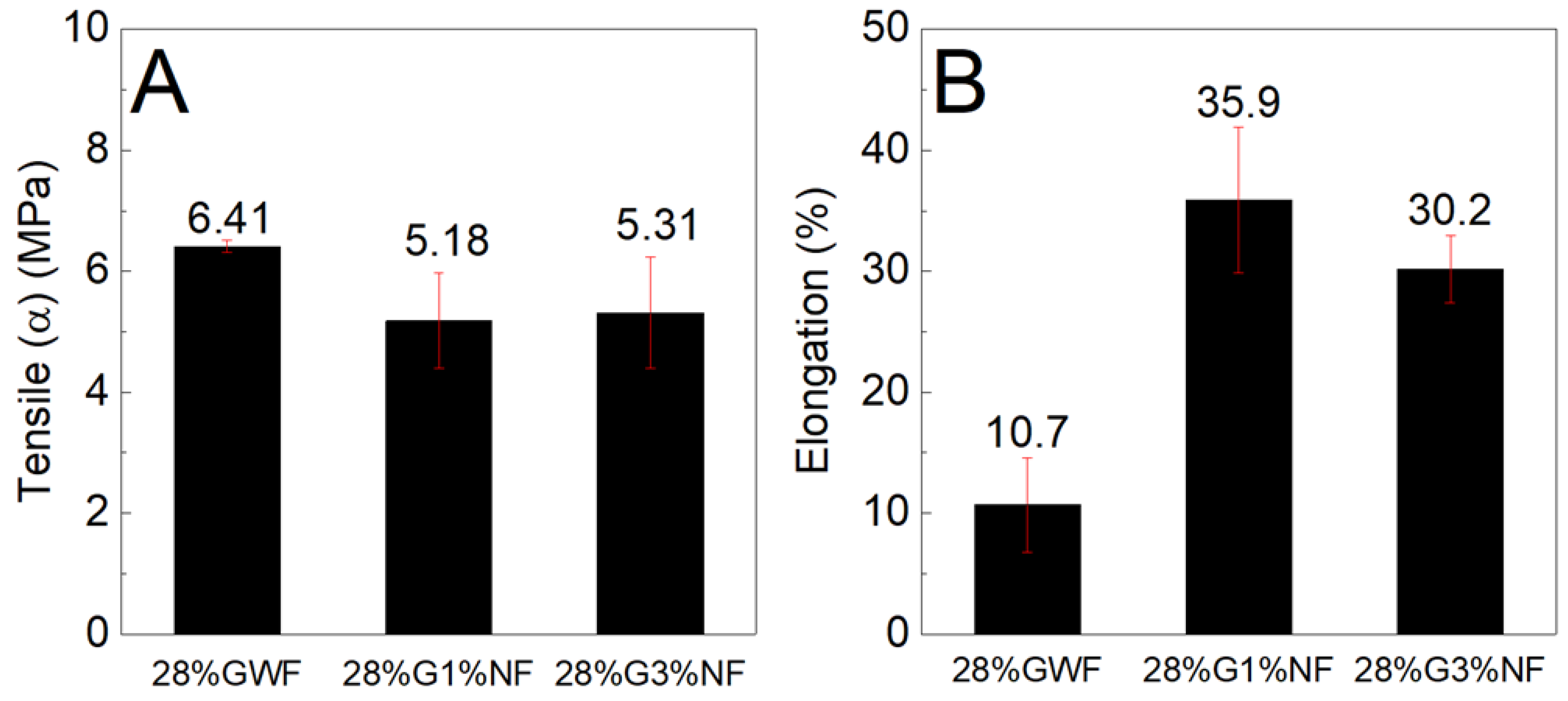

To compare the tensile stress and elongation results of the matrices without reinforcements, tests are performed on the films with nanofibers at concentrations of 1 and 3% in relation to the starch mass. The results are compared to the reference matrix (film without nanofibers). Higher levels of nanofibers can reduce tensile stress due to the agglomeration of nanomaterials, as described in an investigation conducted by Orue et al [

79].

Figure 9 shows the tensile stress and elongation results of the composites reinforced with 1 and 3% sisal nanofibers in the films with 18% glycerol. The tensile stress results of the films reinforced with 1 and 3% sisal nanofibers are lower than the pure matrix 18%GWF; it is noted that with the increase in nanofibers (from 1% to 3%) in the thermoplastic starch, there is an increase in the mechanical strength. Regarding the elongation results, there is a reduction as the concentration of nanofibers in the reference matrix 18%GWF increases.

Figure 9.

(A) Maximum tensile stress and (B) elongation characteristics of the films with 18% glycerol reinforced with 1% and 3% sisal nanofibers.

Figure 9.

(A) Maximum tensile stress and (B) elongation characteristics of the films with 18% glycerol reinforced with 1% and 3% sisal nanofibers.

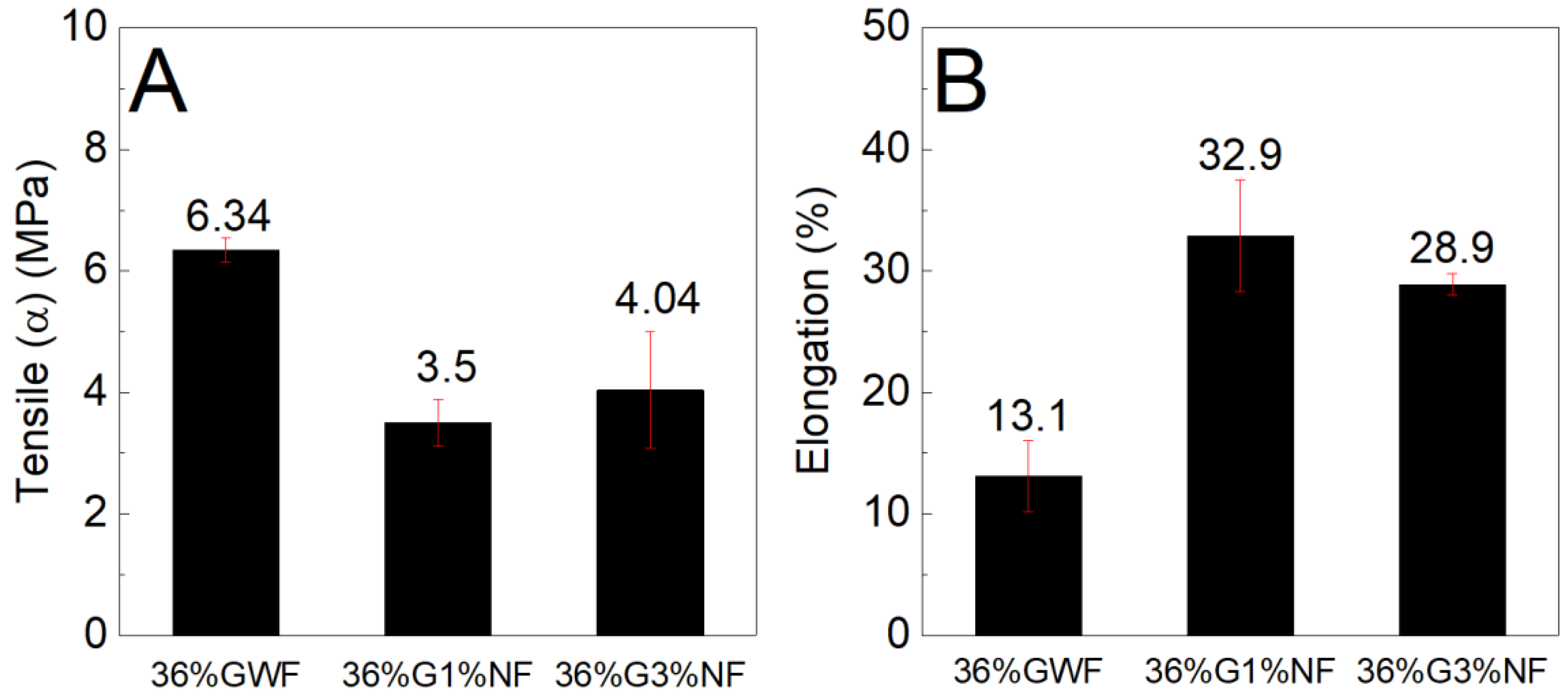

Figure 10 and

Figure 11 show the tensile stress and elongation results of composites with concentrations of 28 and 36% plasticizer (glycerol) reinforced with 1 and 3% sisal nanofibers.

Figure 10 shows that the reference matrix 28%GWF (film without nanofibers) presents a higher tensile stress than the films reinforced with nanofibers. There are no significant differences between the tensile stress results of the films reinforced with 1 and 3% nanofibers. According to the elongation results, the presence of nanofibers contributes to its elevation; there is an increase of approximately 25% in the films with 1% nanofibers and an increase of 20% for the films reinforced with 3% nanofibers.

Figure 11 shows similar findings for both the tensile stress and elongation results; the nanofibers reduce the strengths and increase the deformations of the films. Considering the results presented in

Figure 10 and

Figure 11, two hypotheses are raised. The first hypothesis concerns the dispersion of the nanofibers in the matrix, which occurs inhomogeneous; this phenomenon may have contributed to the reduction in resistance. The lack of good compatibility between the nanofibers and the thermoplastic matrix reduces the intermolecular interactions between the nanofibers and the starch chains, which compromises the dispersion of nanofibers. The poor dispersion of nanofibers in the matrix produces an inhomogeneous stress transfer, which results in a non-homogeneous stress transfer, thus reducing the tensile stress. Moreover, the relatively high length of the nanofibers (as observed by the TEM image, section 3.7) may increase their agglomeration and thus decrease the distribution of the nanofibers in the starch matrix, decreasing the tensile stress [

41]. These results are consistent with those found by Zhang et al, who stated that addition of different cellulose caused a decrease in tensile stress. They stated that this behavior also occurs due to the lack of good dispersion of fillers in the starch matrix [

47]. In addition, the redispersion of the nanofibers in the films was not highly efficient because during drying, the nanofibers tended to aggregate to form rigid plates that were difficult to disperse in aqueous media; this phenomenon could have influenced the tensile stress. The second hypothesis concerns the increases in the deformations of the films reinforced with nanofibers in relation to the reference matrix; these increases may have occurred due to the formation of a blend of the structures of starch and cellulose (which also has a polymer chain). Combined with higher concentrations of plasticizer, this phenomenon forms a material that undergoes high amounts of elongation. Our results revealed that the poor dispersion of nanofibers may have contributed to decrease the tensile stress of corn starch films with sisal nanofibers.

4. Conclusions

Based on the SEM, chemical analysis (α-cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin), and XRD analyses, the use of mechanical pretreatment followed by alkaline treatment showed satisfactory results. After mechanical treatment, most microfibrils were individualized, becoming more exposed to alkaline and bleaching treatments, which consequently enabled the removal of much of the amorphous materials (hemicellulose and lignin).

The cellulose nanofibers of the (treated) sisal fibers were obtained from acid hydrolysis using 50% (v/v) sulfuric acid (H2SO4). This concentration was much lower than the most common concentrations in the literature (from 60 to 64%), representing a 23% reduction in acid for obtaining these materials. TEM images revealed the elongated shapes (needles) of the crystalline nanocellulose; the results were similar to those presented in the literature, indicating the efficiency of the treatments for obtaining nanofibers. The diffraction pattern of the sisal nanofiber sample fitted by Rietveld refinement revealed the presence of a single crystalline phase of cellulose: phase Iα.

In general, the composites reinforced with sisal nanofibers showed lower tensile performance levels than the matrix. It was noteworthy that the redispersion of the nanofibers in the films was not highly efficient because during drying, the nanofibers tended to aggregate to form rigid plates that were difficult to disperse in aqueous media; this phenomenon could have influenced the tensile stress results of the composites.

Author Contributions

Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Validation, Formal analysis, M.B.V.; Validation, Investigation, Resources, E.J.S.C.; Writing – original draft , Validation, Investigation, Resources, M.V.S.P.; Validation, Investigation, B.M.V.; Validation, Investigation, D.C.E.; Validation, Investigation, E.C.R.; : Data curation, Project administration, Resources, R.C.O.; Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, E.N.M.; Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, J.A.S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially financed by the Brazilian National Council of Scientific Technological and Innovation Development (CNPq), Brazil, and Dean of Research and Graduate Studies (Propesp), Federal University of Para.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the office for research (PROPESP/UFPA, process number 23073.069827/2022-01), PPGF/UFPA, National Council for Scientifc and Technological Development (CNPq, Brazil) and Coordination of Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES, Brazil) for their financial support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Gomez-Caturla, J.; Ivorra-Martinez, J.; Fenollar, O.; Balart, R.; Garcia-Garcia, D.; Dominici, F.; Puglia, D.; Torre, L. Development of Starch-Rich Thermoplastic Polymers Based on Mango Kernel Flour and Different Plasticizers. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 264, 130773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Wang, Z.; Ren, J.; Lin, X.; Zhao, J.; Jiang, X.; Chen, Y. Molecular Dynamics Simulation and Properties of Thermoplastic Starch -- Effect of Water Content on Starch Plasticization. Polymer 2024, 290, 126571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N.; Zou, F.; Tao, H.; Guo, L.; Cui, B.; Fang, Y.; Lu, L.; Wu, Z.; Yuan, C.; Zhao, M.; et al. Effects of Primary, Secondary and Tertiary Structures on Functional Properties of Thermoplastic Starch Biopolymer Blend Films. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 236, 124006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekchanov, D.; Mukhamediev, M.; Yarmanov, S.; Lieberzeit, P.; Mujahid, A. Functionalizing Natural Polymers to Develop Green Adsorbents for Wastewater Treatment Applications. Carbohydr. Polym. 2024, 323, 121397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Tiwari, A.; Chaudhari, C.V.; Bhardwaj, Y.K. Low Cost Highly Efficient Natural Polymer-Based Radiation Grafted Adsorbent-I: Synthesis and Characterization. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2021, 182, 109377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Lei, Q.; Yang, F.; Xie, J.; Chen, C. Development of Cinnamon Essential Oil-Loaded PBAT/Thermoplastic Starch Active Packaging Films with Different Release Behavior and Antimicrobial Activity. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 263, 130048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghani, S.W.A.; Bakar, A.A.; Samsudin, S.A. Mechanical and Physical Properties of Chitosan-Compatibilized Montmorillonite-Filled Tapioca Starch Nanocomposite Films. J. Plast. Film Sheeting 2016, 32, 140–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, Z.; Ferreira, N.M.; Ferreira, P.; Nunes, C. Design of Heat Sealable Starch-Chitosan Bioplastics Reinforced with Reduced Graphene Oxide for Active Food Packaging. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 291, 119517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani, M.; Alizadeh, P. Aloe Vera Incorporated Starch-64S Bioactive Glass-Quail Egg Shell Scaffold for Promotion of Bone Regeneration. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 217, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malherbi, N.M.; Grando, R.C.; Fakhouri, F.M.; Velasco, J.I.; Tormen, L.; da Silva, G.H.R.; Yamashita, F.; Bertan, L.C. Effect of the Addition of Euterpe Oleracea Mart. Extract on the Properties of Starch-Based Sachets and the Impact on the Shelf-Life of Olive Oil. Food Chem. 2022, 394, 133503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Toro, R.; Santagata, G.; Gomez d’Ayala, G.; Cerruti, P.; Talens Oliag, P.; Chiralt Boix, M.A.; Malinconico, M. Enhancement of Interfacial Adhesion between Starch and Grafted Poly(ε-Caprolactone). Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 147, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, B.A. de M.; Junior, C.C.M.F.; Silva, E.G.P. da; Franco, M.; Santos Reis, N. dos; Ferreira Bonomo, R.C.; Almeida, P.F. de; Pontes, K.V. Biodegradable Thermoplastic Starch of Peach Palm (Bactris Gasipaes Kunth) Fruit: Production and Characterisation. Int. J. Food Prop. 2017, 20, S2429–S2440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahrami, B.; Behzad, T.; Salehinik, F.; Zamani, A.; Heidarian, P. Incorporation of Extracted Mucor Indicus Fungus Chitin Nanofibers into Starch Biopolymer: Morphological, Physical, and Mechanical Evaluation. Starch - Stärke 2021, 73, 2000218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fourati, Y.; Tarrés, Q.; Delgado-Aguilar, M.; Mutjé, P.; Boufi, S. Cellulose Nanofibrils Reinforced PBAT/TPS Blends: Mechanical and Rheological Properties. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 183, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferri, J.M.; Garcia-Garcia, D.; Sánchez-Nacher, L.; Fenollar, O.; Balart, R. The Effect of Maleinized Linseed Oil (MLO) on Mechanical Performance of Poly(Lactic Acid)-Thermoplastic Starch (PLA-TPS) Blends. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 147, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, J.F.; Paschoalin, R.T.; Carmona, V.B.; Sena Neto, A.R.; Marques, A.C.P.; Marconcini, J.M.; Mattoso, L.H.C.; Medeiros, E.S.; Oliveira, J.E. Biodegradable Polymer Blends Based on Corn Starch and Thermoplastic Chitosan Processed by Extrusion. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 137, 452–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- França, D.; Angelo, L.M.; Souza, C.F.; Faez, R. Biobased Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate)/Starch/Cellulose Nanofibrils for Nutrients Coatings. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2021, 3, 3227–3237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samper-Madrigal, M.D.; Fenollar, O.; Dominici, F.; Balart, R.; Kenny, J.M. The Effect of Sepiolite on the Compatibilization of Polyethylene–Thermoplastic Starch Blends for Environmentally Friendly Films. J. Mater. Sci. 2015, 50, 863–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rico, M.; Rodríguez-Llamazares, S.; Barral, L.; Bouza, R.; Montero, B. Processing and Characterization of Polyols Plasticized-Starch Reinforced with Microcrystalline Cellulose. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 149, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Kuo, M.; Yang, L.; Huang, C.; Wei, W.; Huang, C.-M.; Huang, K.-S.; Yeh, J. Strength Retention and Moisture Resistant Properties of Citric Acid Modified Thermoplastic Starch Resins. J. Polym. Res. 2017, 24, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Xie, F.; Zhang, T.; Chen, L.; Li, X.; Truss, R.W.; Halley, P.J.; Shamshina, J.L.; McNally, T.; Rogers, R.D. Different Characteristic Effects of Ageing on Starch-Based Films Plasticised by 1-Ethyl-3-Methylimidazolium Acetate and by Glycerol. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 146, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Chen, F.; Meng, Y.; Wang, S.; Long, Z. Oxidized Microcrystalline Cellulose Improve Thermoplastic Starch-Based Composite Films: Thermal, Mechanical and Water-Solubility Properties. Polymer 2019, 168, 228–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazerolles, T.; Heuzey, M.C.; Soliman, M.; Martens, H.; Kleppinger, R.; Huneault, M.A. Development of Co-Continuous Morphology in Blends of Thermoplastic Starch and Low-Density Polyethylene. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 206, 757–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, M.G.A.; da Silva, M.A.; dos Santos, L.O.; Beppu, M.M. Natural-Based Plasticizers and Biopolymer Films: A Review. Eur. Polym. J. 2011, 47, 254–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdanowicz, M.; Spychaj, T.; Mąka, H. Imidazole-Based Deep Eutectic Solvents for Starch Dissolution and Plasticization. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 140, 416–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paluch, M.; Ostrowska, J.; Tyński, P.; Sadurski, W.; Konkol, M. Structural and Thermal Properties of Starch Plasticized with Glycerol/Urea Mixture. J. Polym. Environ. 2022, 30, 728–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Hou, A.; Hu, X.; Lu, X.; Qu, J.-P. Effect of Elongational Rheology on Plasticization and Properties of Thermoplastic Starch Prepared by Biaxial Eccentric Rotor Extruder. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 176, 114323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, A.C.; Benze, R.; Ferrão, E.S.; Ditchfield, C.; Coelho, A.C.V.; Tadini, C.C. Cassava Starch Biodegradable Films: Influence of Glycerol and Clay Nanoparticles Content on Tensile and Barrier Properties and Glass Transition Temperature. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamus, J.; Spychaj, T.; Zdanowicz, M.; Jędrzejewski, R. Thermoplastic Starch with Deep Eutectic Solvents and Montmorillonite as a Base for Composite Materials. Ind. Crops Prod. 2018, 123, 278–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Gupta, B. Physicochemical Characteristics of Glycerol-Plasticized Dextran/Soy Protein Isolate Composite Membranes. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2016, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Sagnelli, D.; Faisal, M.; Perzon, A.; Taresco, V.; Mais, M.; Giosafatto, C.V.L.; Hebelstrup, K.H.; Ulvskov, P.; Jørgensen, B.; et al. Amylose/Cellulose Nanofiber Composites for All-Natural, Fully Biodegradable and Flexible Bioplastics. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 253, 117277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanbari, A.; Tabarsa, T.; Ashori, A.; Shakeri, A.; Mashkour, M. Preparation and Characterization of Thermoplastic Starch and Cellulose Nanofibers as Green Nanocomposites: Extrusion Processing. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 112, 442–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, P.H.M.; Bastian, F.L.; Thiré, R.M.S.M. Curaua Fibers/Epoxy Laminates with Improved Mechanical Properties: Effects of Fiber Treatment Conditions. Macromol. Symp. 2014, 344, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, R.D.; Ferreira, S.R.; Oliveira, G.E.; Silva, F.A.; Souza Jr., F.G.; Toledo Filho, R.D. Influence of Alkaline Hornification Treatment Cycles on the Mechanical Behavior in Curaua Fibers. Macromol. Symp. 2018, 381, 1800096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mothé, C.G.; de Araujo, C.R.; Wang, S.H. Thermal and Mechanical Characteristics of Polyurethane/Curaua Fiber Composites. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2009, 95, 181–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Yi, Y.; Wang, H.; Yang, Y.; Zeng, L.; Tan, Z. Light-Colored Cellulose Nanofibrils Produced from Raw Sisal Fibers without Costly Bleaching. Ind. Crops Prod. 2021, 172, 114009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samouh, Z.; Molnár, K.; Hajba, S.; Boussu, F.; Cherkaoui, O.; El Moznine, R. Elaboration and Characterization of Biocomposite Based on Polylactic Acid and Moroccan Sisal Fiber as Reinforcement. Polym. Compos. 2021, 42, 3812–3826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.R.; Isa, N.; Yahaya, A.N.; Beg, M.D.H.; Yunus, R.M. Mechanical, Interfacial, and Fracture Characteristics of Poly (Lactic Acid) and Moringa Oleifera Fiber Composites. Adv. Polym. Technol. 2018, 37, 1665–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akindoyo, J.O.; Beg, M.D.H.; Ghazali, S.; Islam, M.R. The Effects of Wettability, Shear Strength, and Weibull Characteristics of Fiber-Reinforced Poly(Lactic Acid) Composites. J. Polym. Eng. 2016, 36, 489–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beg, M.; Islam, M.R.; Mamun, A.; Heim, H.-P.; Feldmann, M. Comparative Analysis of the Properties: Microcrystalline Cellulose Fiber Polyamide Composites Filled with Ethylene Copolymer and Olefin Elastomer. Polym. Polym. Compos. 2020, 28, 242–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekar, C.M.; Krishnamachari, H.; Farris, S.; Romano, D. Development and Characterization of Starch-Based Bioactive Thermoplastic Packaging Films Derived from Banana Peels. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2023, 5, 100328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumaidin, R.; Khiruddin, M.A.A.; Asyul Sutan Saidi, Z.; Salit, M.S.; Ilyas, R.A. Effect of Cogon Grass Fibre on the Thermal, Mechanical and Biodegradation Properties of Thermoplastic Cassava Starch Biocomposite. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 146, 746–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Soest, P.J.; Robertson, J.B.; Lewis, B.A. Methods for Dietary Fiber, Neutral Detergent Fiber, and Nonstarch Polysaccharides in Relation to Animal Nutrition. J. Dairy Sci. 1991, 74, 3583–3597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunes, J.C.; Melo, P.T.S.; Aouada, F.A.; Moura, M.R. de INFLUENCE OF LEMON NANOEMULSION IN FILMS GELATIN-BASED. Quím. Nova 2018, 41, 1006–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teodoro, K.B.R.; Teixeira, E. de M.; Corrêa, A.C.; Campos, A. de; Marconcini, J.M.; Mattoso, L.H.C. Whiskers de fibra de sisal obtidos sob diferentes condições de hidrólise ácida: efeito do tempo e da temperatura de extração. Polímeros 2011, 21, 280–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faruk, O.; Bledzki, A.K.; Fink, H.-P.; Sain, M. Biocomposites Reinforced with Natural Fibers: 2000–2010. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2012, 37, 1552–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zou, F.; Tao, H.; Gao, W.; Guo, L.; Cui, B.; Yuan, C.; Liu, P.; Lu, L.; Wu, Z.; et al. Effects of Different Sources of Cellulose on Mechanical and Barrier Properties of Thermoplastic Sweet Potato Starch Films. Ind. Crops Prod. 2023, 194, 116358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuebas, L.; Bertolini Neto, J.A.; Barros, R.T.P. de; Cordeiro, A.O.T.; Rosa, D. dos S.; Martins, C.R. The Incorporation of Untreated and Alkali-Treated Banana Fiber in SEBS Composites. Polímeros 2021, 30, e2020040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ching, Y.C.; Ng, T.S. Effect of Preparation Conditions on Cellulose from Oil Palm Empty Fruit Bunch Fiber. BioResources 2014, 9, 6373–6385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathishkumar, T.; Navaneethakrishnan, P.; Shankar, S.; Rajasekar, R.; Rajini, N. Characterization of Natural Fiber and Composites – A Review. J. Reinf. Plast. Compos. 2013, 32, 1457–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, V.K.; Thakur, M.K. Processing and Characterization of Natural Cellulose Fibers/Thermoset Polymer Composites. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 109, 102–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sood, M.; Dwivedi, G. Effect of Fiber Treatment on Flexural Properties of Natural Fiber Reinforced Composites: A Review. Egypt. J. Pet. 2018, 27, 775–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vilhena, M.B.; Matos, R.M.; Ramos Junior, G.S. da S.; Viegas, B.M.; da Silva Junior, C.A.B.; Macedo, E.N.; Paula, M.V. da S.; da Silva Souza, J.A.; Candido, V.S.; de Sousa Cunha, E.J. Influence of Glycerol and SISAL Microfiber Contents on the Thermal and Tensile Properties of Thermoplastic Starch Composites. Polymers 2023, 15, 4141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsyad, M.; Wardana, I.N.G.; Pratikto; Irawan, Y.S. The Morphology of Coconut Fiber Surface under Chemical Treatment. Matér. Rio Jan. 2015, 20, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madival, A.S.; Maddasani, S.; Shetty, R.; Doreswamy, D. Influence of Chemical Treatments on the Physical and Mechanical Properties of Furcraea Foetida Fiber for Polymer Reinforcement Applications. J. Nat. Fibers 2023, 20, 2136816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, S.; Sahu, S.B.B.P.J.; Nayak, S.; Mohapatra, J.; Khuntia, S.K.; Malla, C.; Samal, P.; Patra, S.K.; Swain, S. Characterization of Natural Fiber Extracted from Bauhinia Vahlii Bast Subjected to Different Surface Treatments: A Potential Reinforcement in Polymer Composite. J. Nat. Fibers 2023, 20, 2162185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarique, J.; Sapuan, S.M.; Khalina, A. Effect of Glycerol Plasticizer Loading on the Physical, Mechanical, Thermal, and Barrier Properties of Arrowroot (Maranta Arundinacea) Starch Biopolymers. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 13900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhou, H.; Xiao, Y.; Feng, L.; Yang, L.; Mu, W.; Peng, X.; Bao, L.; Wang, J. Hydrophobic Thermoplastic Starch Supramolecularly-Induced by a Functional Sucrose Based Ionic Liquid Crystal. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 255, 117363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Khoi, N.; Tung, N.T.; Ha, P.T.T.; Trang, P.T.; Duc, N.T.; Thang, T.V.; Phuong, H.T.; Huong, N.T.; Phuong, N.T.L. Study on Characteristics of Thermoplastic Starch Based on Vietnamese Arrowroot Starch Plasticized by Glycerol. Vietnam J. Chem. 2023, 61, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Yu, H.; Liu, Y.; Chen, P.; Zhang, M.; Hai, Y. Individualization of Cellulose Nanofibers from Wood Using High-Intensity Ultrasonication Combined with Chemical Pretreatments. Carbohydr. Polym. 2011, 83, 1804–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, D.; Li, M.; Yue, J. Isolation and Characterization of Nanocellulose Crystals via Acid Hydrolysis from Agricultural Waste-Tea Stalk. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 163, 927–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, H.-M.; Sin, L.T.; Tee, T.-T.; Bee, S.-T.; Hui, D.; Low, C.-Y.; Rahmat, A.R. Extraction of Cellulose Nanocrystals from Plant Sources for Application as Reinforcing Agent in Polymers. Compos. Part B Eng. 2015, 75, 176–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adel, A.; El-Shafei, A.; Ibrahim, A.; Al-Shemy, M. Extraction of Oxidized Nanocellulose from Date Palm (Phoenix Dactylifera L.) Sheath Fibers: Influence of CI and CII Polymorphs on the Properties of Chitosan/Bionanocomposite Films. Ind. Crops Prod. 2018, 124, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrêa, A.; Teixeira, E.; Pessan, L.; Mattoso, L. Cellulose Nanofibers from Curaua Fibers. Cellulose 2010, 17, 1183–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishiyama, Y.; Sugiyama, J.; Chanzy, H.; Langan, P. Crystal Structure and Hydrogen Bonding System in Cellulose Iα from Synchrotron X-Ray and Neutron Fiber Diffraction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 14300–14306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, B.; Bucio, L. Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC) Analysis and Quantitative Phase Analysis of Ciprofloxacin/MCC Mixtures by Rietveld XRD Refinement with Physically Based Background. Cellulose 2018, 25, 2795–2815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacaphol, K.; Seraypheap, K.; Aht-Ong, D. Extraction and Silylation of Cellulose Nanofibers from Agricultural Bamboo Leaf Waste for Hydrophobic Coating on Paper. J. Nat. Fibers 2023, 20, 2178581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinas, I.C.; Gradisteanu Pircalabioru, G.; Oprea, E.; Geana, E.-I.; Zgura, I.; Romanitan, C.; Matei, E.; Angheloiu, M.; Brincoveanu, O.; Georgescu, M.; et al. Physico-Chemical and pro-Wound Healing Properties of Microporous Cellulosic Sponge from Gleditsia Triacanthos Pods Functionalized with Phytolacca Americana Fruit Extract. Cellulose 2023, 30, 10313–10339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, P.; Hsieh, Y.-L. Preparation and Properties of Cellulose Nanocrystals: Rods, Spheres, and Network. Carbohydr. Polym. 2010, 82, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, M. de F.V.; Melo, R.P.; Araujo, R. da S.; Lunz, J. do N.; Aguiar, V. de O. Improvement of Mechanical Properties of Natural Fiber–Polypropylene Composites Using Successive Alkaline Treatments. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2015, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senthamaraikannan, P.; Kathiresan, M. Characterization of Raw and Alkali Treated New Natural Cellulosic Fiber from Coccinia Grandis.L. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 186, 332–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senthamaraikannan, P.; Saravanakumar, S.S.; Sanjay, M.R.; Jawaid, M.; Siengchin, S. Physico-Chemical and Thermal Properties of Untreated and Treated Acacia Planifrons Bark Fibers for Composite Reinforcement. Mater. Lett. 2019, 240, 221–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, D.; Sarkar, B.K. Characterization of Alkali-Treated Jute Fibers for Physical and Mechanical Properties. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2001, 80, 1013–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossen, Md.T.; Kundu, C.K.; Pranto, B.R.R.; Rahi, Md.S.; Chanda, R.; Mollick, S.; Siddique, A.B.; Begum, H.A. Synthesis, Characterization, and Cytotoxicity Studies of Nanocellulose Extracted from Okra (Abelmoschus Esculentus) Fiber. Heliyon 2024, 10, e25270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galdeano, M.C.; Wilhelm, A.E.; Mali, S.; Grossmann, M.V.E. Influence of Thickness on Properties of Plasticized Oat Starch Films. Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 2013, 56, 637–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polymers | Free Full-Text | Influence of Glycerol and SISAL Microfiber Contents on the Thermal and Tensile Properties of Thermoplastic Starch Composites. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4360/15/20/4141 (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Xie, F.; Flanagan, B.M.; Li, M.; Sangwan, P.; Truss, R.W.; Halley, P.J.; Strounina, E.V.; Whittaker, A.K.; Gidley, M.J.; Dean, K.M.; et al. Characteristics of Starch-Based Films Plasticised by Glycerol and by the Ionic Liquid 1-Ethyl-3-Methylimidazolium Acetate: A Comparative Study. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 111, 841–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Liang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Ye, C.; Chen, Y.; Wei, P.; Wang, Y.; Xia, Y. Thermoplastic Starch Plasticized by Polymeric Ionic Liquid. Eur. Polym. J. 2021, 148, 110367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orue, A.; Corcuera, M.A.; Peña, C.; Eceiza, A.; Arbelaiz, A. Bionanocomposites Based on Thermoplastic Starch and Cellulose Nanofibers. J. Thermoplast. Compos. Mater. 2016, 29, 817–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).