Submitted:

20 April 2024

Posted:

22 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Geometry of the Experimental Setup and Measurement Procedure

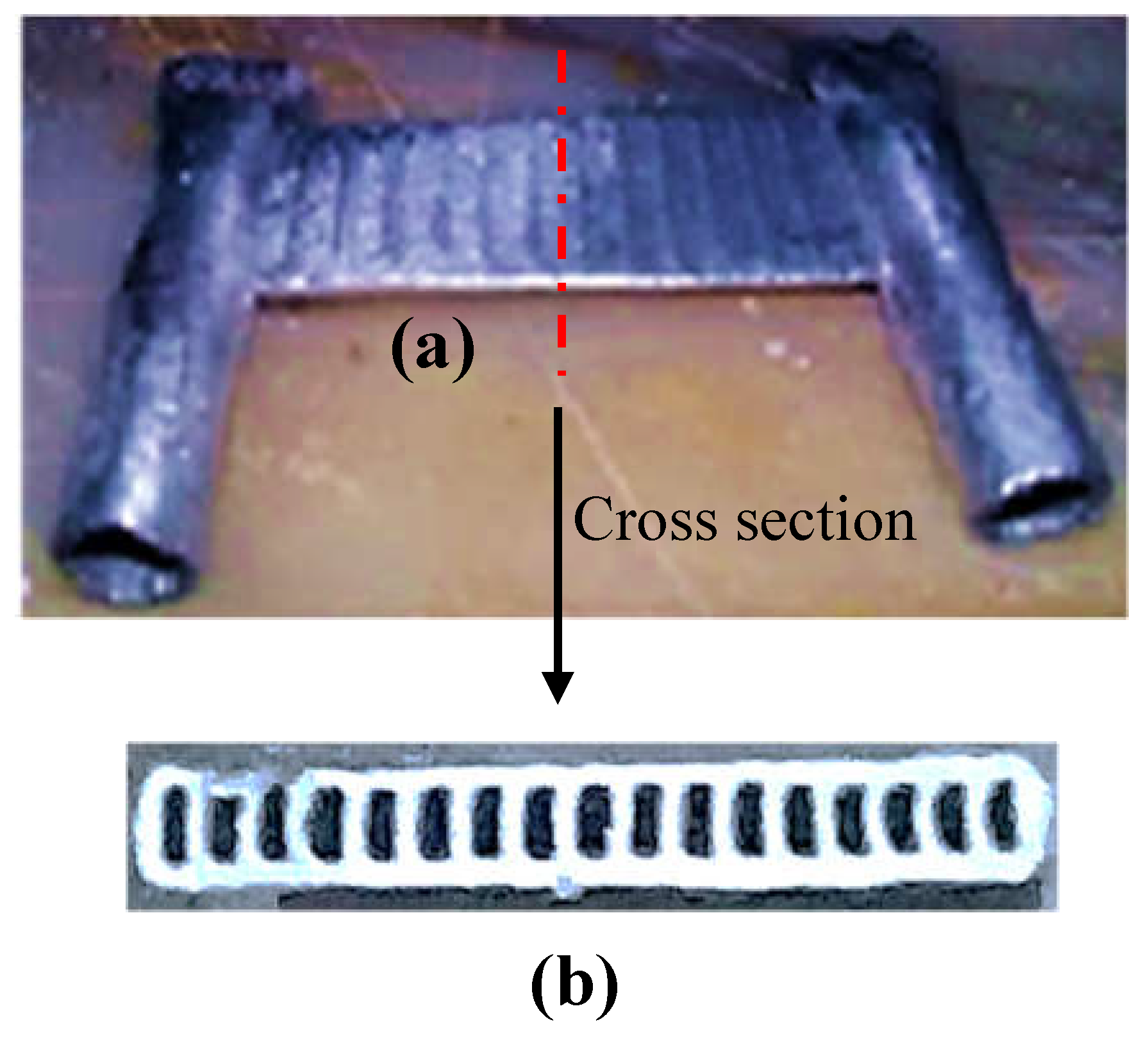

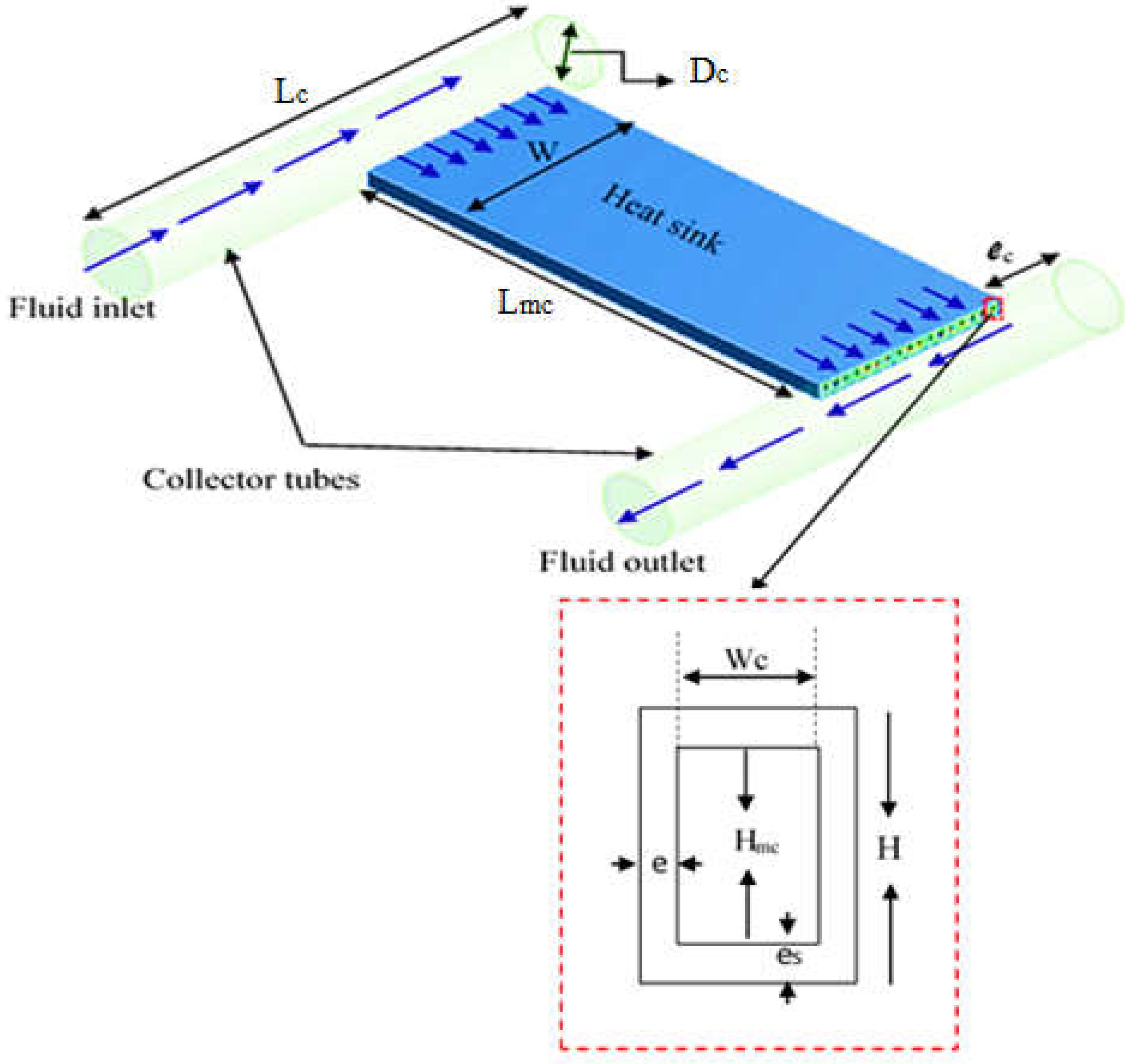

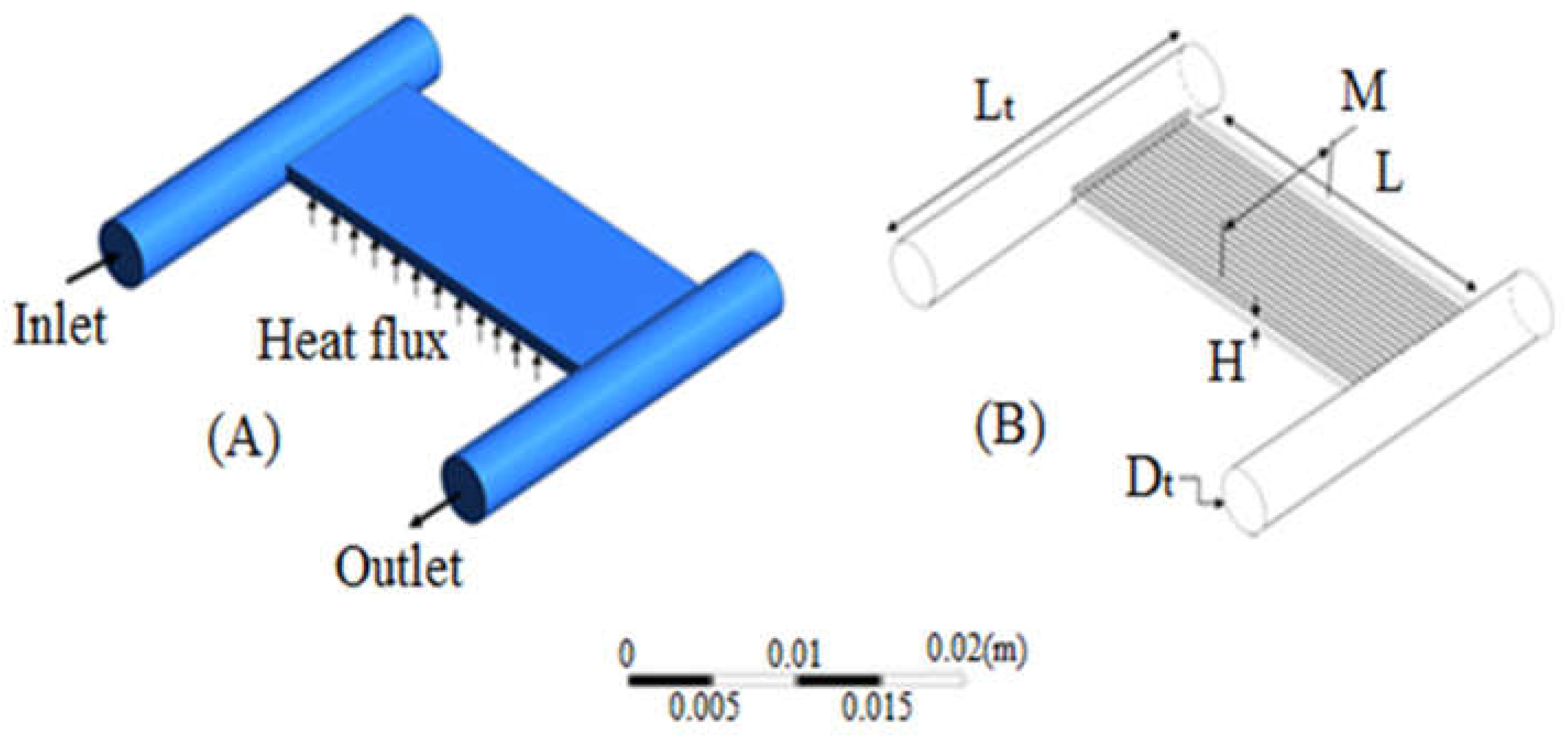

2.1. Geometry

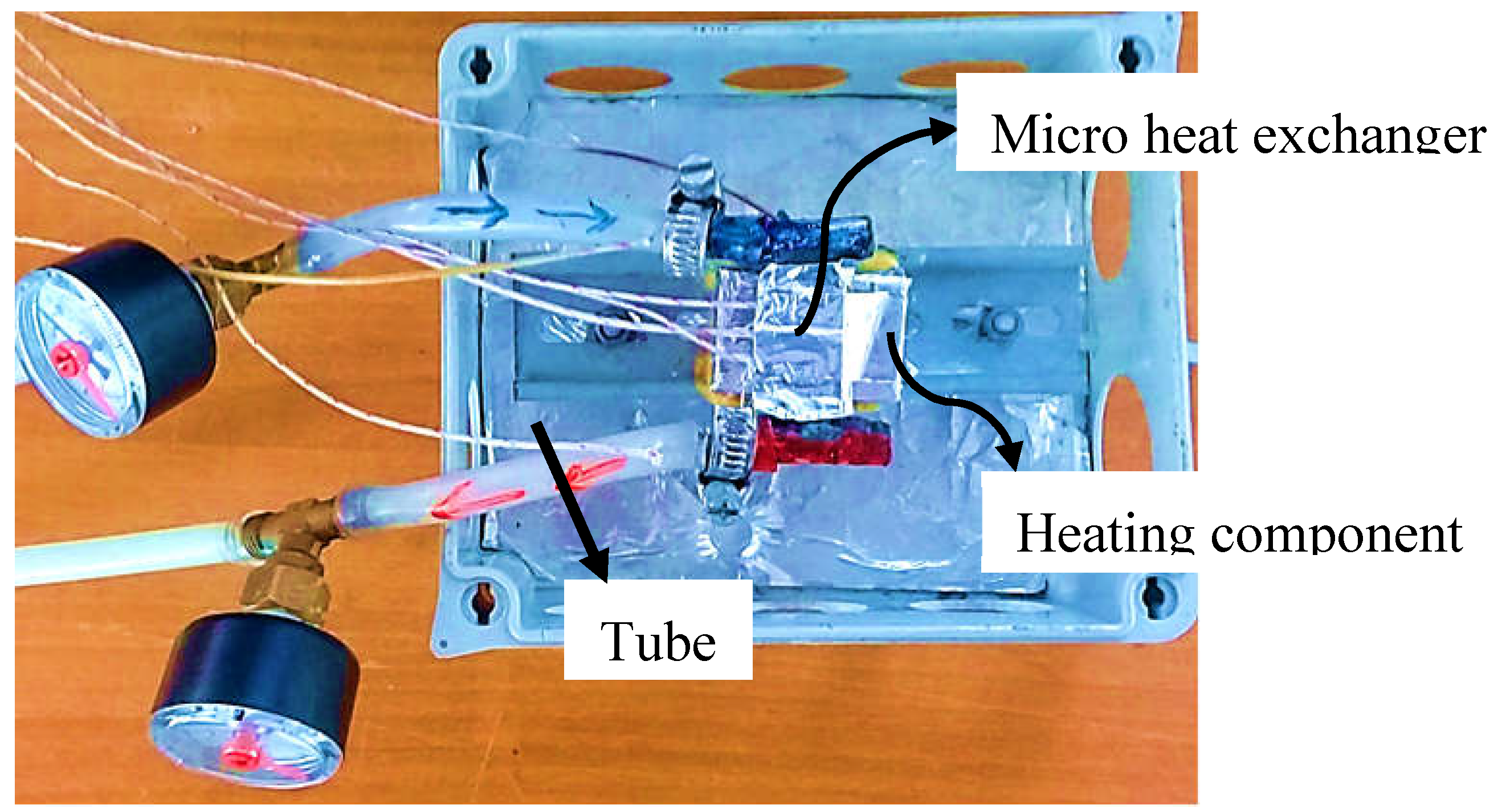

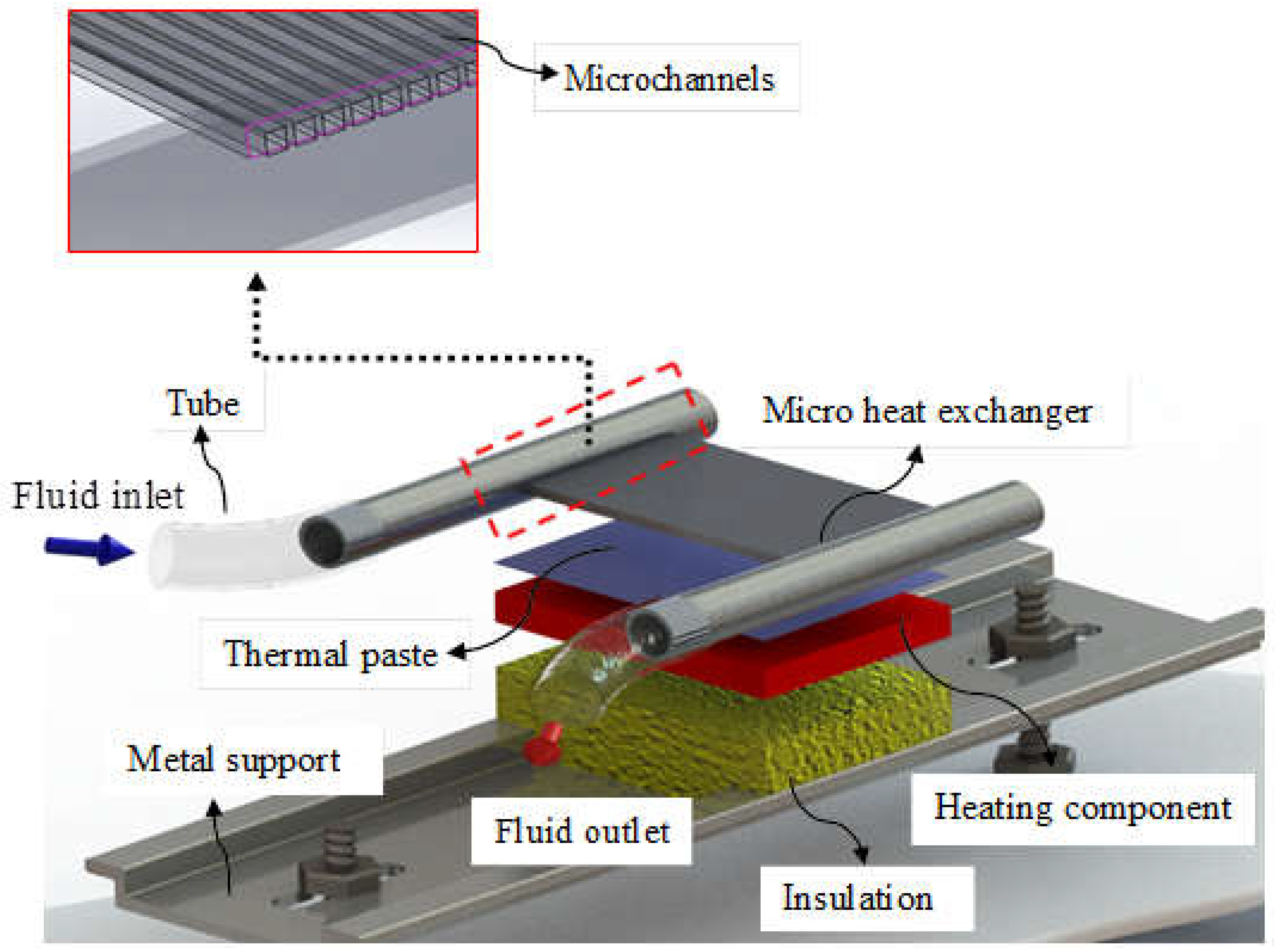

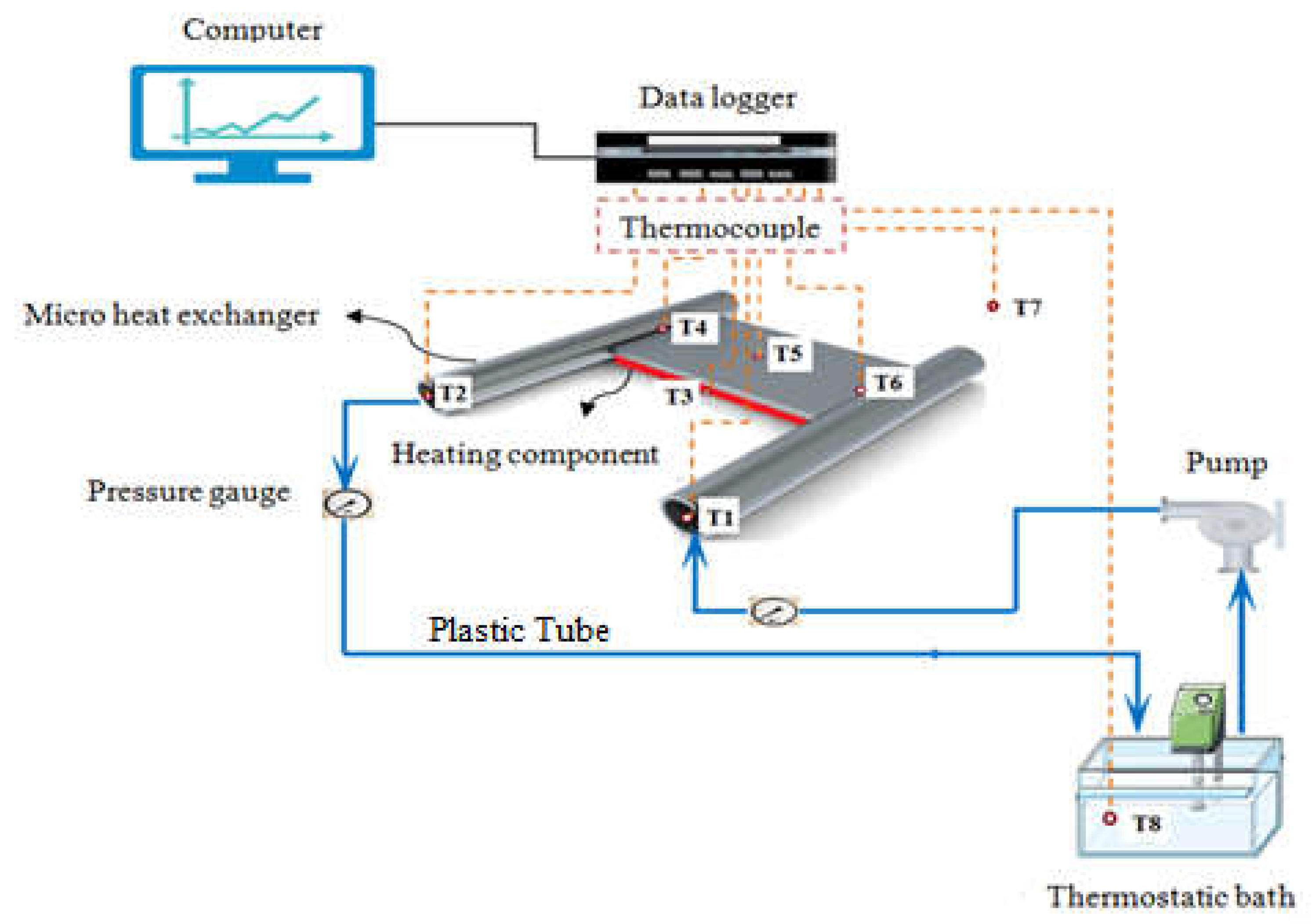

2.2. Experimental Apparatus

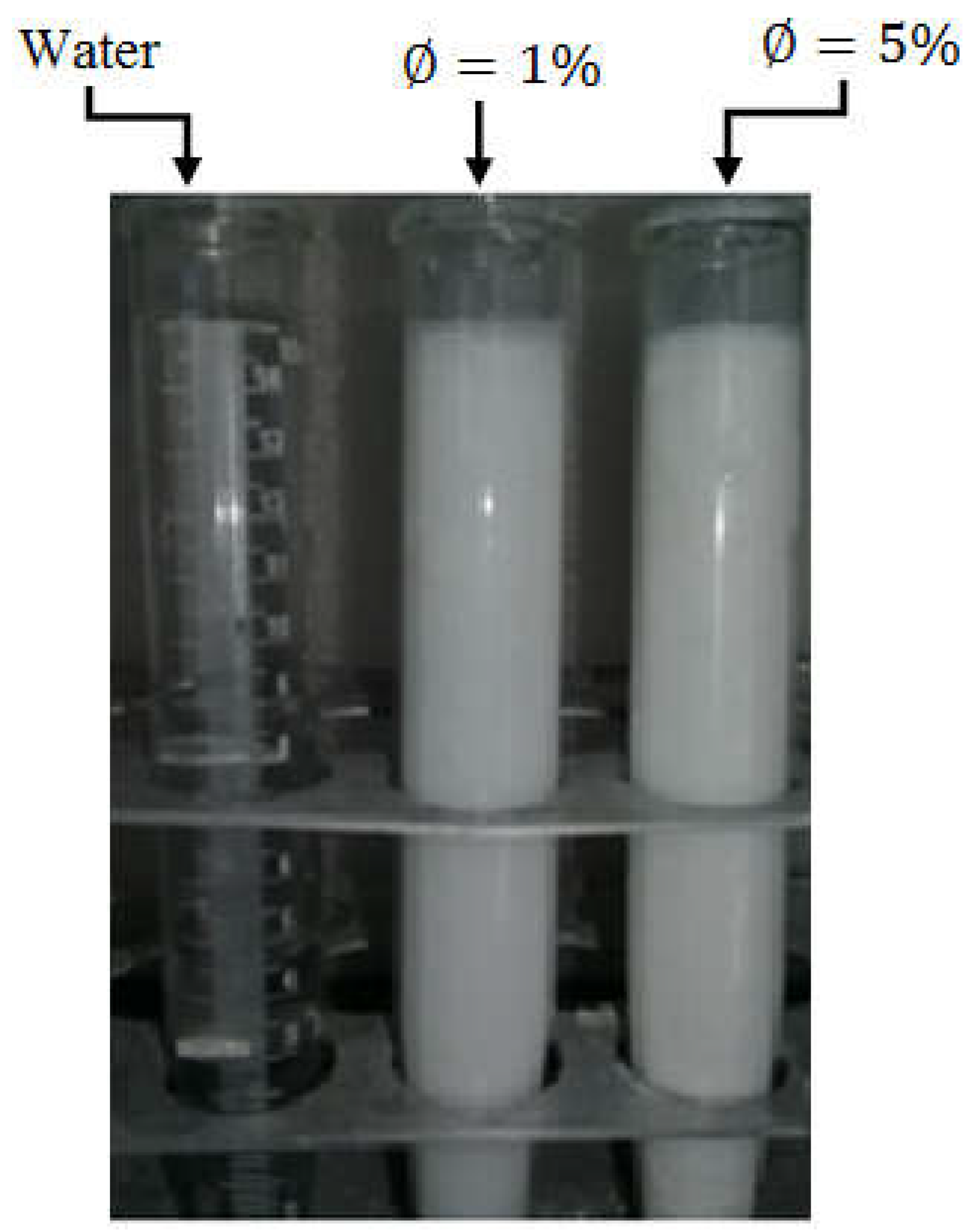

2.3. Nanofluid Preparation and Calculation of Thermophysical Properties

- -

- Density of nanofluids

- -

- Heat capacity of nanofluids

- -

- Viscosity of nanofluids

- -

- Thermal conductivity of nanofluidsWhere, n = 3 for spherical shaped nanoparticles.

3. Data Reduction of the Experimental Data

3.1. Heat Transfer

3.2. Fluid Flow

3.3. Performance Evaluation Criterion (PEC)

3.4. Uncertainty of the Experimental Data

4. Numerical Approach

4.1. Assumptions and Boundary Conditions

4.2. Governing Equations

- -

- Continuity equation:

- -

- Momentum conservation equation:

- -

- Energy conservation equation:

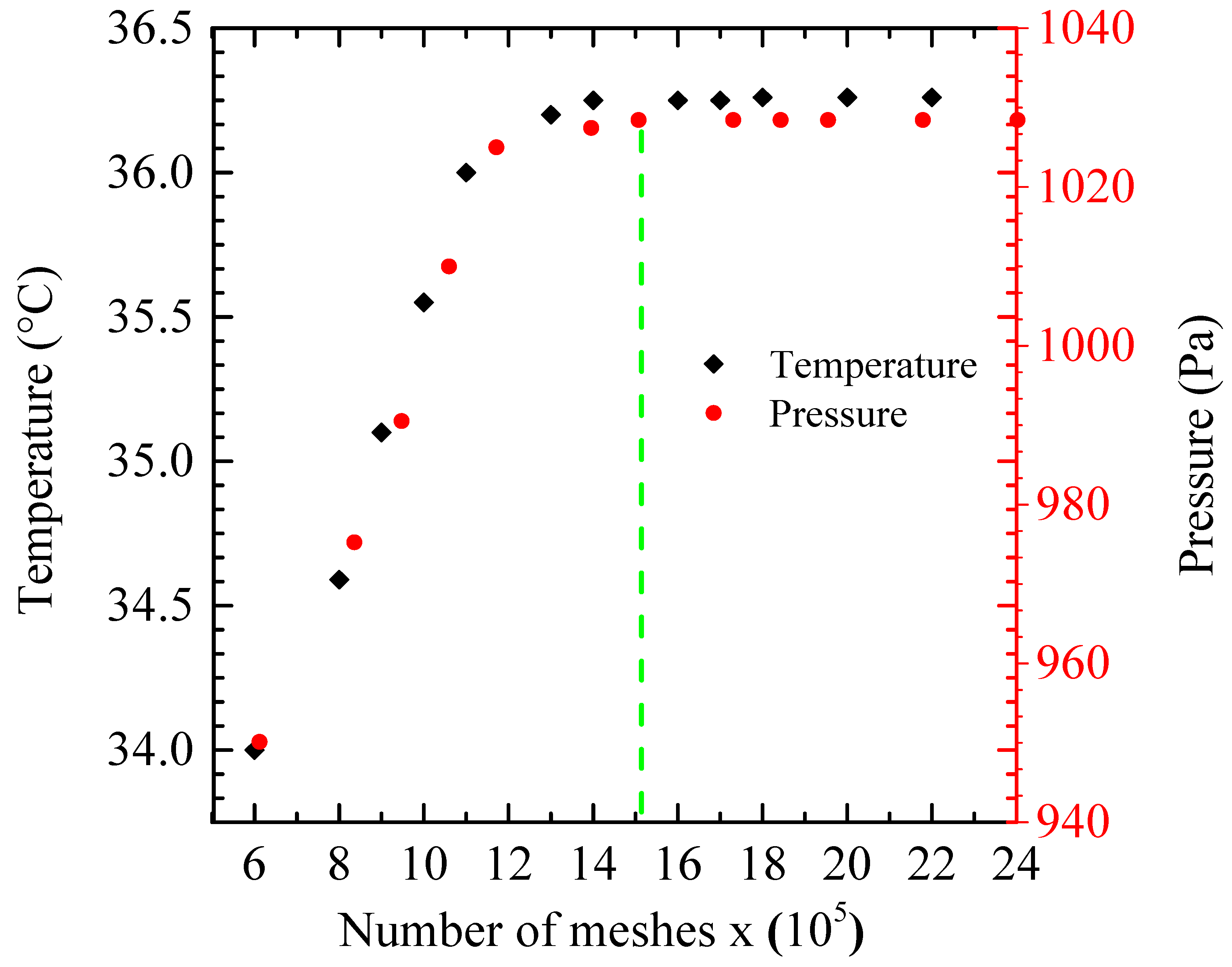

4.3. Effect of Grid Refinement

5. Results and Discussion

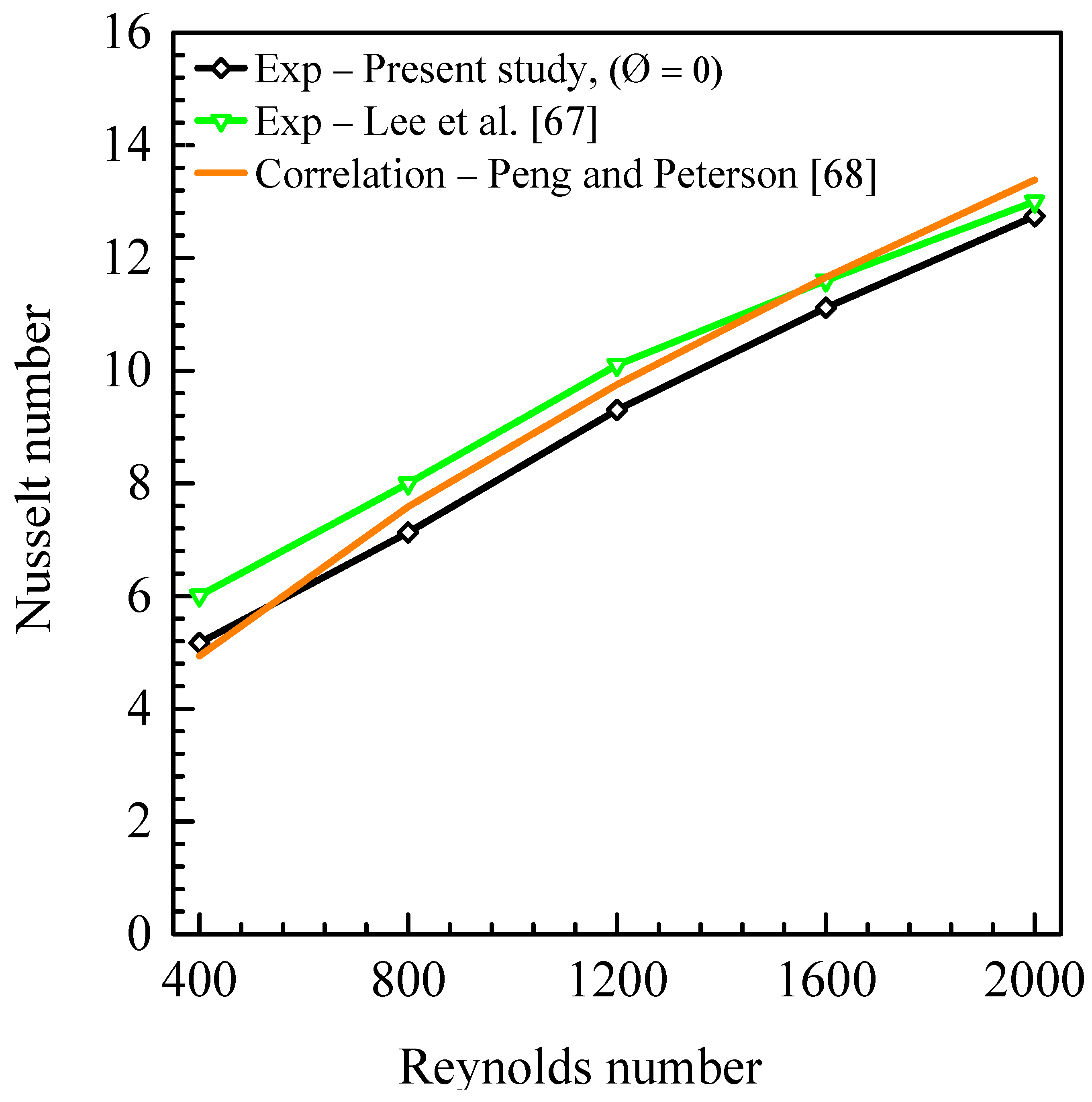

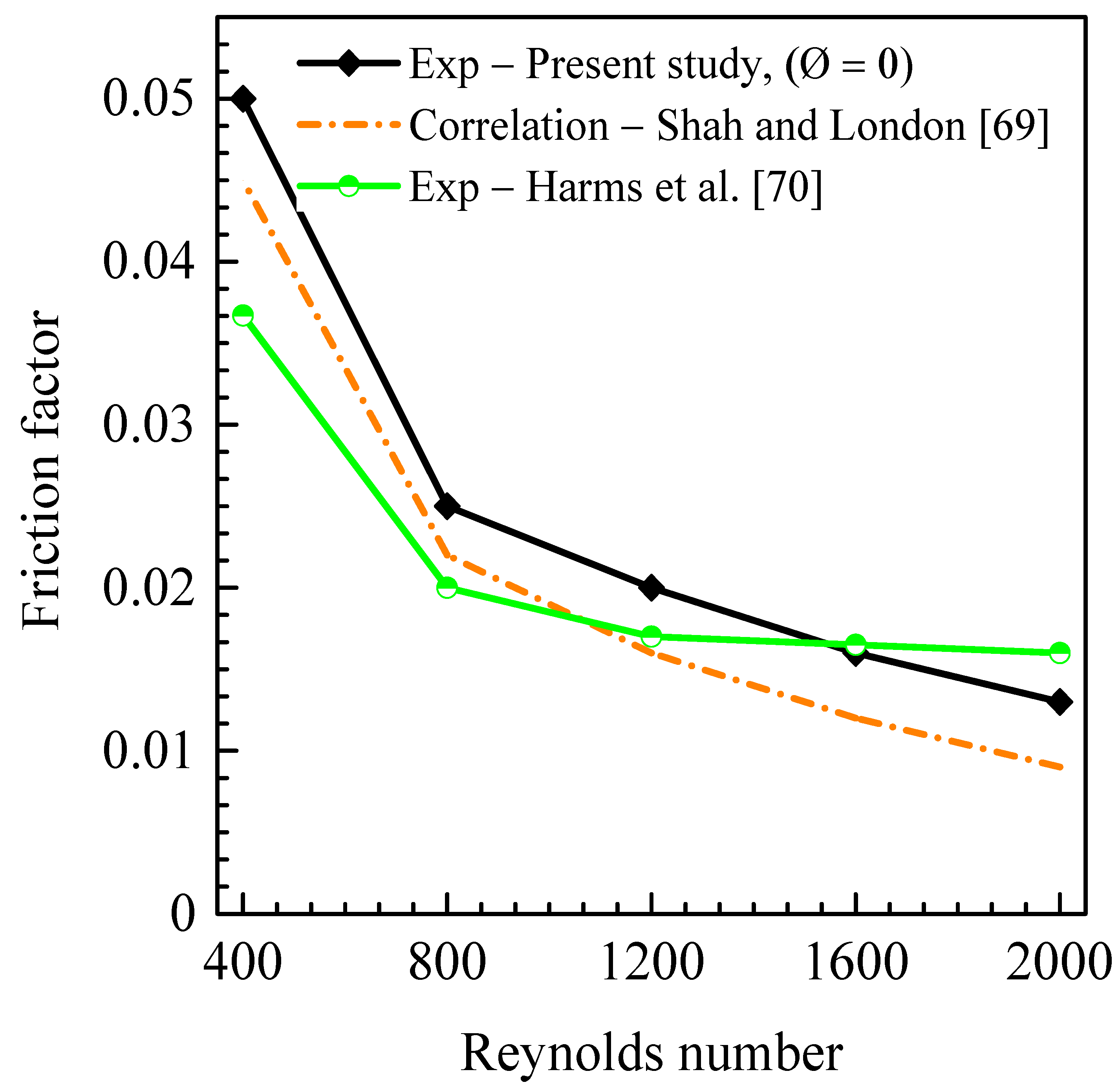

5.1. Validation of Experimental Results

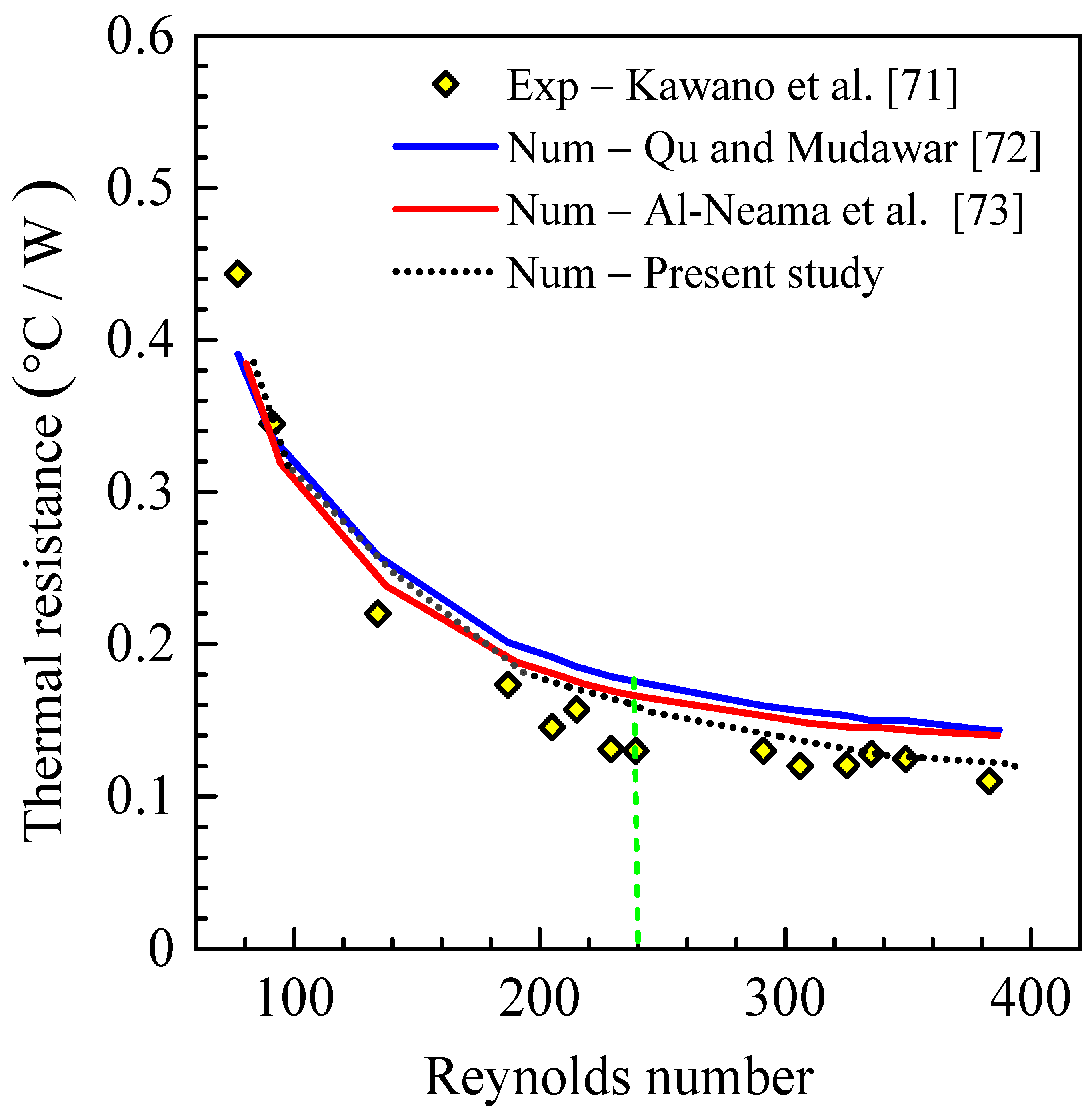

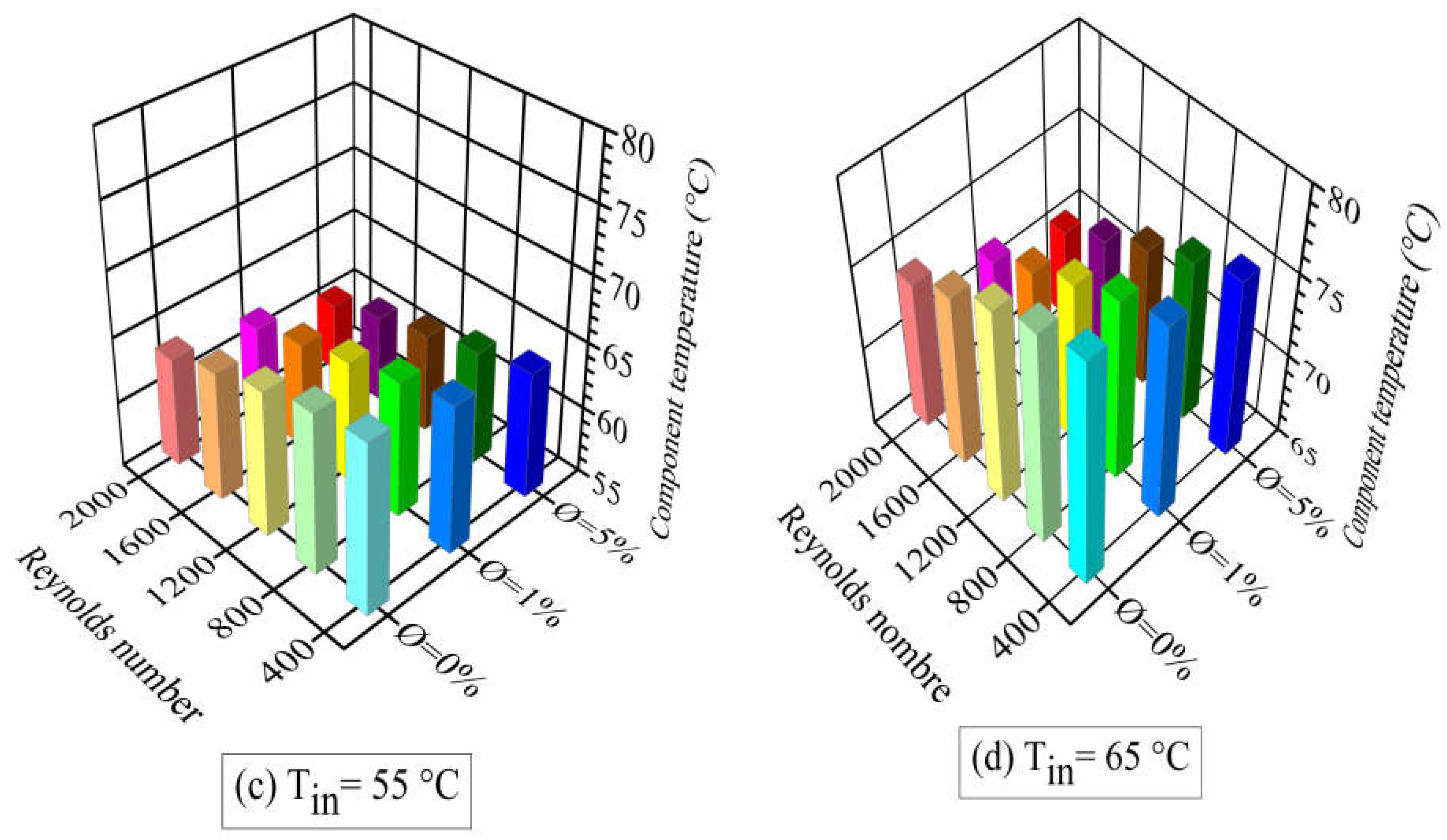

5.2. Validation of the Simulation Code

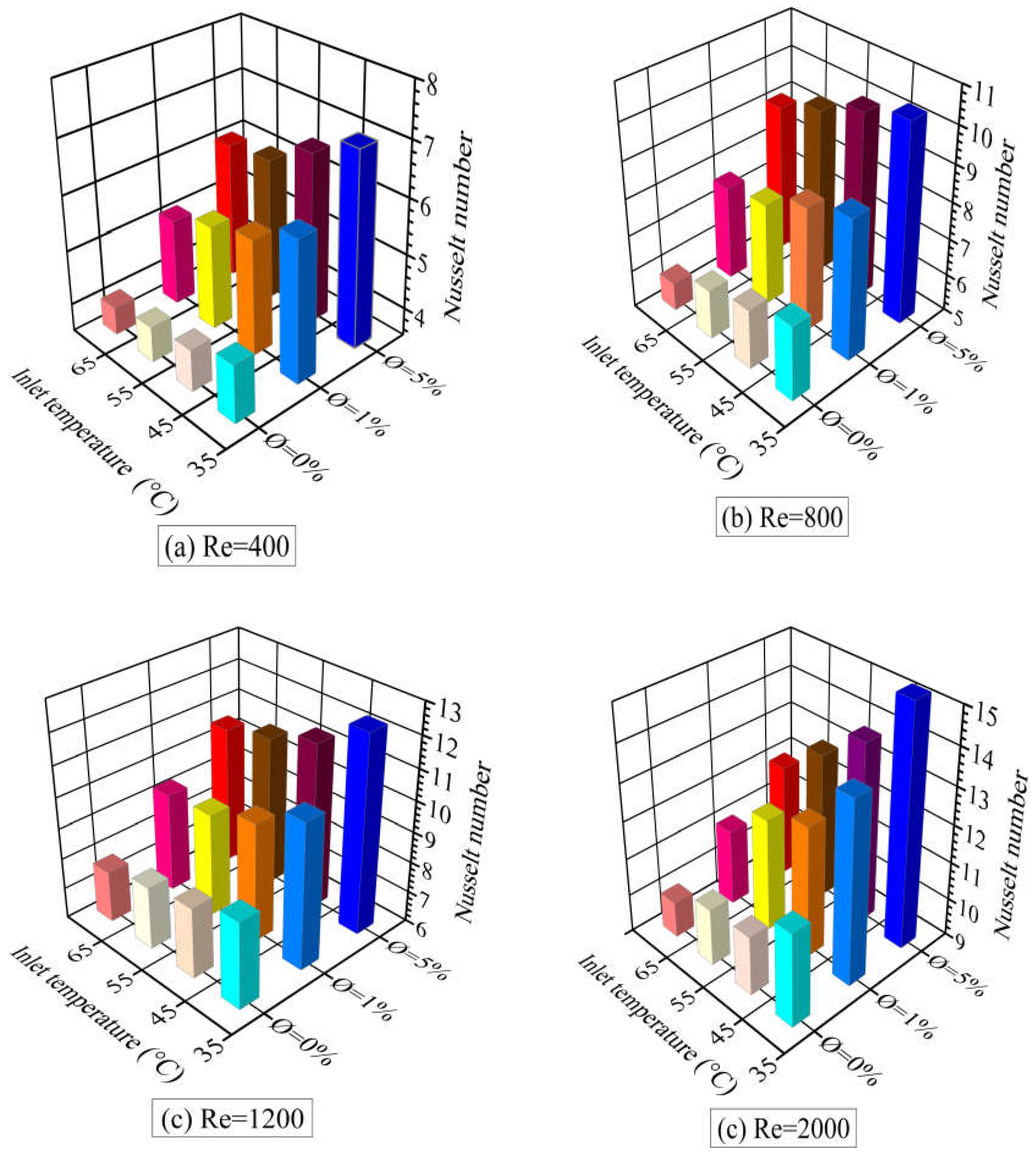

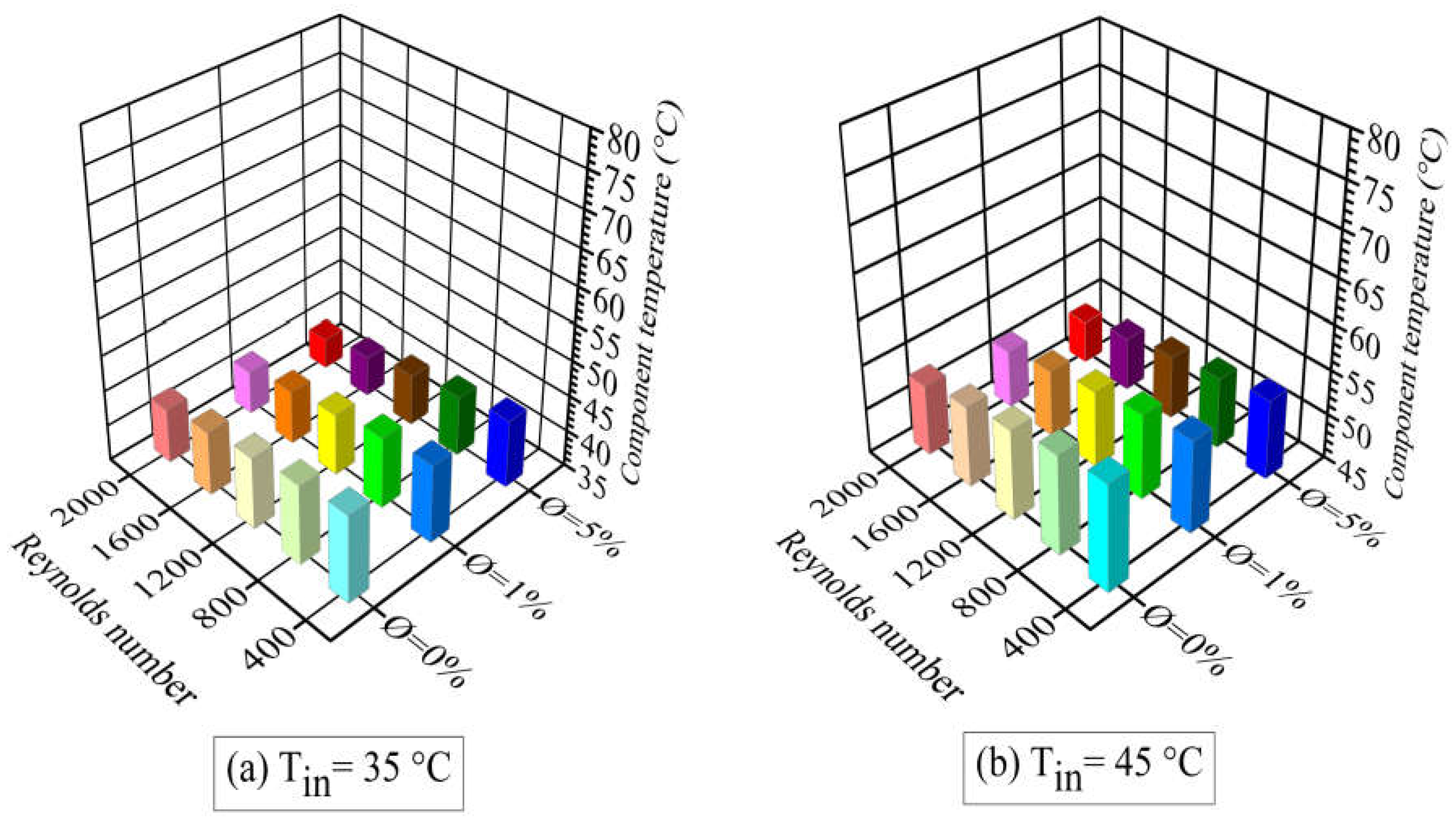

5.3. Heat Transfer Characteristics

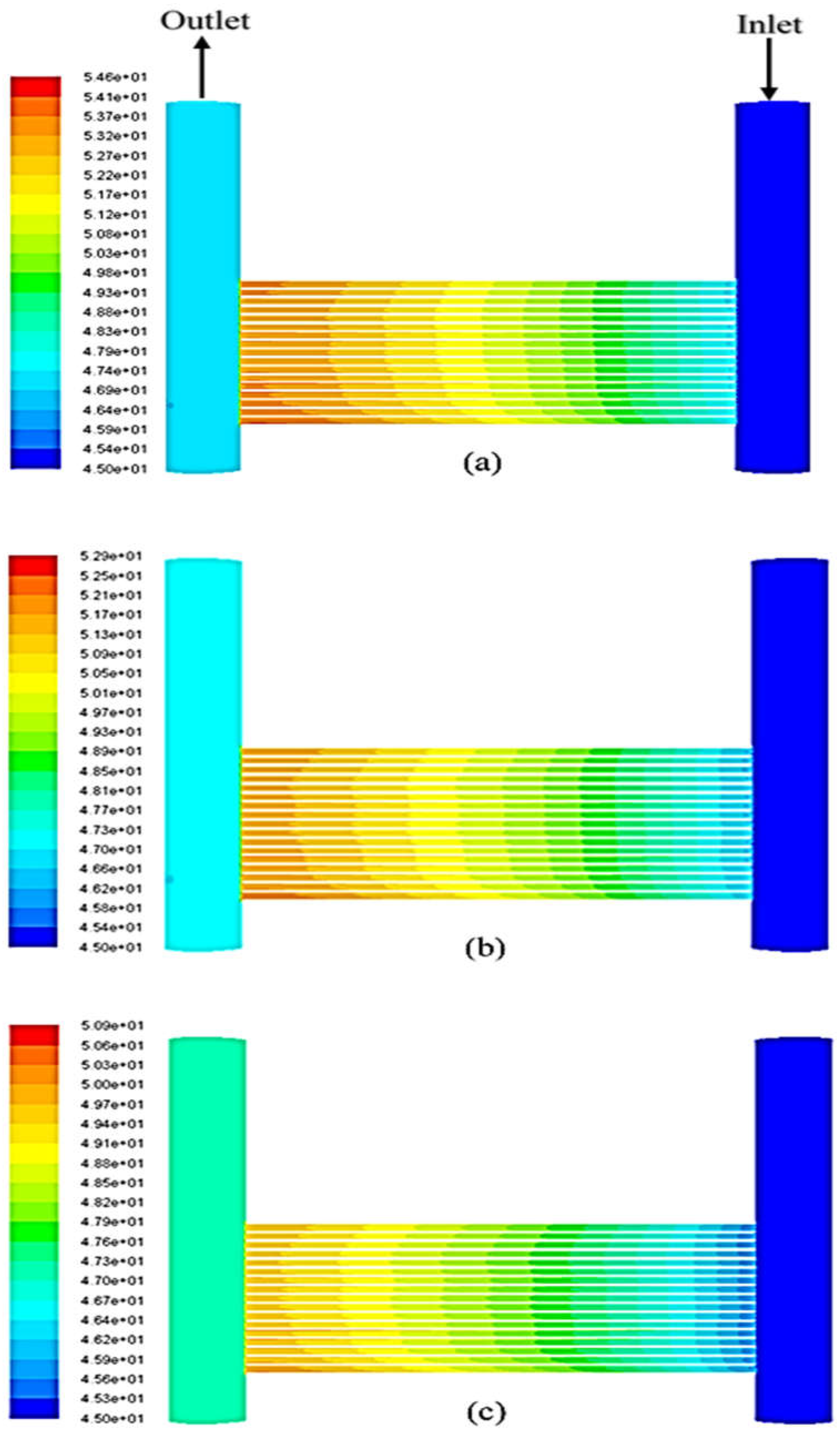

5.4. Pressure Drop Characteristics

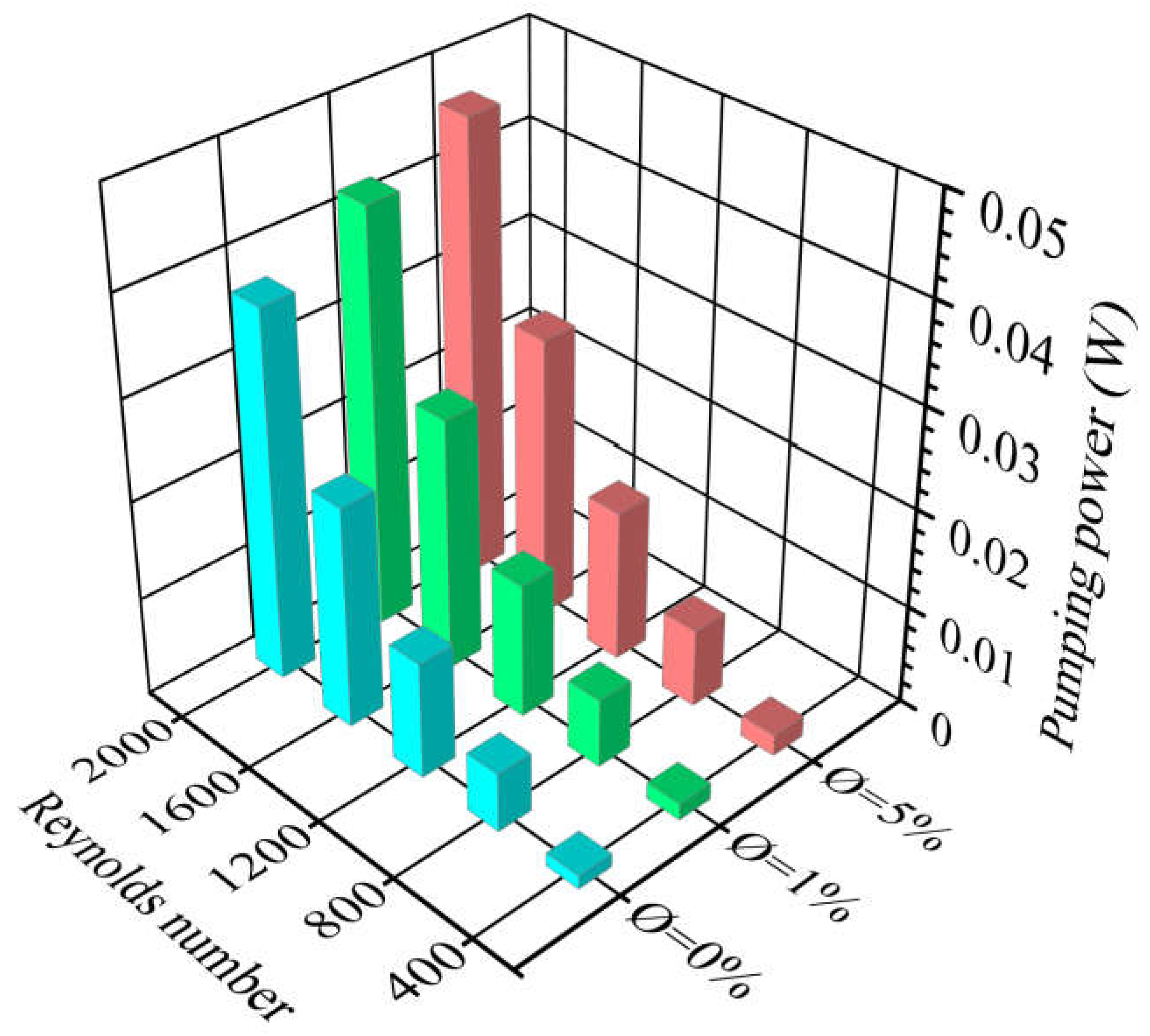

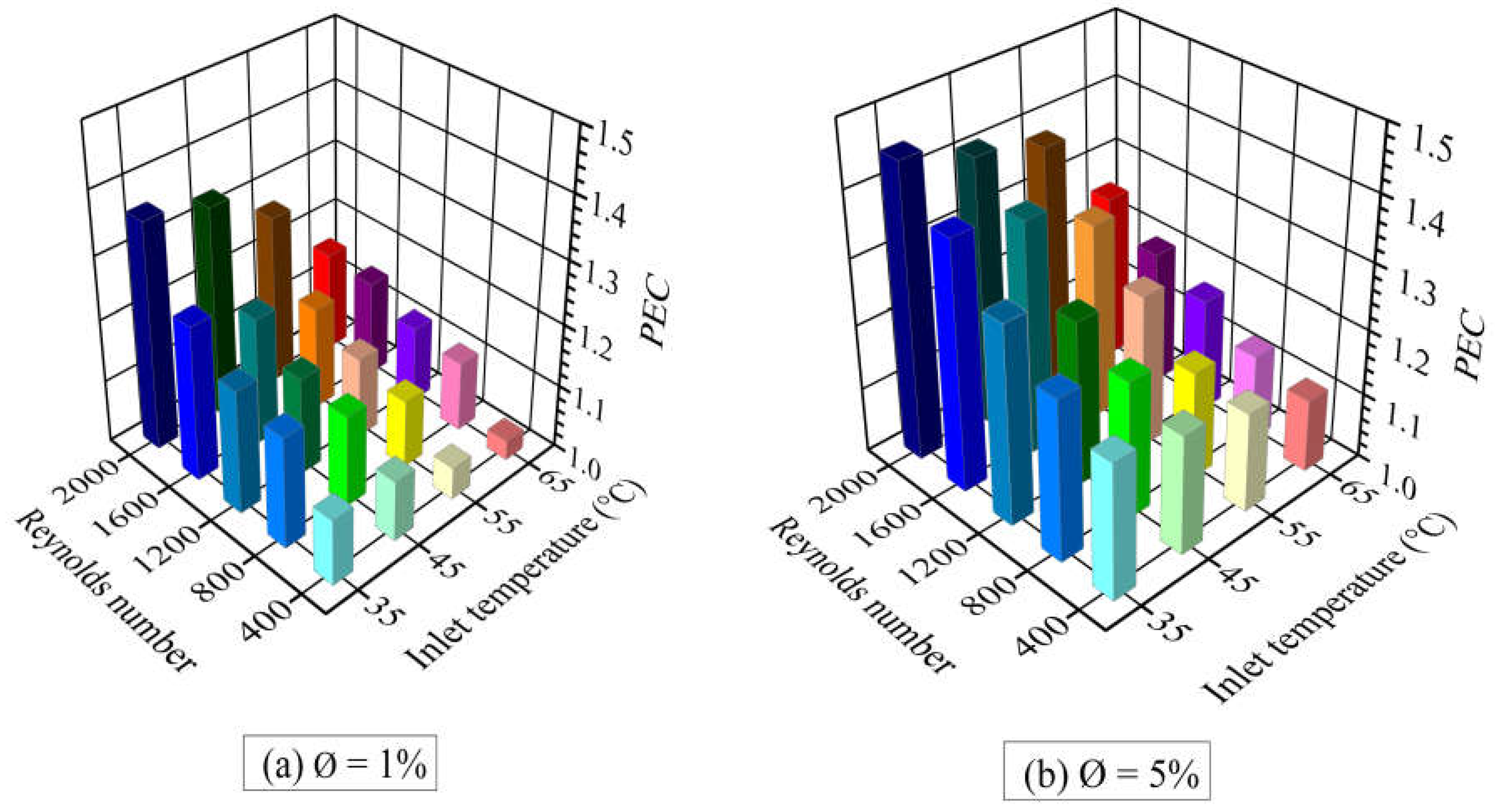

5.5. Performance Evaluation Analysis

6. Conclusions

- Both the experimental setup and the numerical simulation tool were validated using pure water, correlations, experimental data of heat transfer and pressure drop reported in the literature for laminar flows in rectangular microchannels. The deviations between the Nusselt number and the friction factor from the present work and those from the literature were between 2% and 25%.

- An enhancement in the heat transfer process was obtained with the addition of TiO2 nanoparticles to pure water (base fluid), on account of the increase in thermal conductivity. At a nanofluid inlet temperature of 55ºC and a nanoparticle concentration of 1%, the Nusselt number increased by 23% to 54% as the Reynolds number was varied between 400 and 2000. At a nanoparticle concentration of 5%, the corresponding percentages for Nusselt enhancement were 32% and 63%. The highest value of heat transfer enhancement achieved was 70%, which occurred at a Reynolds number of 2000, a nanoparticle concentration of 5%, and an inlet nanofluid temperature of 35ºC.

- It was observed that the nanofluid inlet temperature significantly affected heat transfer. A heat transfer enhancement of about 10% was obtained when the nanofluid inlet temperature was decreased from 65°C to 45°C.

- The increase of both the Reynolds number and the nanoparticle concentration lowered the temperature of the heating components. This widened the safety margin for the critical temperature limit of 80ºC. However, at an inlet temperature of 65ºC, the operating temperature of the electronic equipment was above the safety temperature limit set at 70ºC, even with the addition of nanoparticles and applying high Reynolds numbers.

- The maximum value of pressure drop was obtained with nanofluids at a 5% nanoparticle concentration and a Reynolds number of 2000. A pressure drop increase of about 20% was observed when using (TiO2/water) nanofluids instead of base fluid (pure water).

- PEC values are always greater than the unity for both nanoparticle concentrations. This indicates that adding nanoparticles to cooling water circulating in a micro heat exchanger improves the heat transfer process. At a Reynolds number of 2000 and a nanofluid inlet temperature of 35ºC, PEC values of 1.36 and 1.45 are obtained for nanoparticle concentrations of 1% and 5%, respectively. When the nanofluid inlet temperature is increased to 65ºC, the PEC parameter goes down to 1.02-1.10 for both concentrations.

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Nomenclature

|

Aeff Ac Amc Atube Cp dp Dc Dh e es f app h H Hmc k Kc Ke K90 I Lc L m N Nu P Ṗ Q̇ Re Pr t T u, v, w W Ẇ |

Effective heat transfer area (m2) Collector area (m2) Cross-sectional area of each flow channel (m2) Tube area (m2) Specific heat (J/kg.K) Particle diameter (nm) Collector diameter (mm) Hydraulic diameter (mm) Thickness of pin fin (mm) Thickness of the upper face of heat sink (mm) Apparent friction factor Convective heat transfer coefficient (W/m2.K) Heat sink depth (mm) Micro channel depth (mm) Thermal conductivity (W/m.K) Contraction loss coefficient Expansion loss coefficient Bend loss coefficient, (=1.2) Electrical intensity (A) Collector tube length (mm) Heat sink length (mm) Mass (kg) Number of channels Nusselt number Pressure (Pa) Electric power (W) Heat transfer rate (W) Reynolds Number Prandtl number Time (s) Temperature (°C) Velocity in the directions x, y and z (m/s) Voltage (V) Volume flow (m3/s) Heat sink width (mm) Power pumping (W) |

| Symbols | |

|

ρ µ γ ϕ α LMTD PEC |

Density (kg/m3) Dynamic viscosity (kg/m.s) Convergence criterion Particle mass fraction (%) Coverage factor Channel aspect ratio Log-Mean Temperature Difference (°C) Performance Evaluation Criterion |

| Subscripts | |

|

avg bf c in f mc min max nf np out s |

Average Base fluid Collector Inlet Fluid Micro channel Minimum Maximum Nanofluid Nanoparticle Outlet Surface |

References

- S. Zimmermann, M.K. Tiwari, I. Meijer, S. Paredes, B. Michel, D. Poulikakos. Hot water cooled electronics: Exergy analysis and waste heat reuse feasibility. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, vol. 55(23-24), pp. 6391–6399, 2012. [CrossRef]

- H.Y. Zhang, D. Pinjala, T.N. Wong, K.C. Toh, Y.K. Joshi. Single-phase liquid cooled microchannel heat sink for electronic packages. Applied Thermal Engineering, vol. 25(10), pp. 1472–1487, 2005. [CrossRef]

- P. Naphon, S. Wiriyasart. Liquid cooling in the mini-rectangular fin heat sink with and without thermoelectric for CPU. International Communications in Heat and Mass Transfer, vol. 36(2), pp. 166-171, 2009. [CrossRef]

- D.B. Tuckerman, R.F.W. Pease. High-Performance Heat Sinking for VLSI. IEEE Electron Device Letters, vol. EDL-2(5), pp. 126–129, 1981; https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/1481851. [CrossRef]

- P. Gao, S. Le Person, M. Favre-Marinet. Scale effects on hydrodynamics and heat transfer in two-dimensional mini and microchannels. International Journal of Thermal Sciences, vol. 41(11), pp. 1017–1027, 2002. [CrossRef]

- G.M. Mala, D. Li. Flow characteristics of water in microtubes. International Journal of Heat and Fluid Flow, vol. 20(2), pp. 142–148, 1999. [CrossRef]

- A.G. Fedorov, R. Viskanta. Three-dimensional conjugate heat transfer in the microchannel heat sink for electronic packaging. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, vol. 43(3), pp. 399–415, 2000. [CrossRef]

- H.Y. Wu, P. Cheng. Friction factors in smooth trapezoidal silicon microchannels with different aspect ratios. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, vol. 46(14), pp. 2519–2525, 2003. [CrossRef]

- E.G. Colgan, B. Furman, A. Gaynes, W. Graham, N. LaBianca, J.H. Magerlein, R.J. Polastre, M.B. Rothwell, R.J. Bezama. A practical implementation of silicon microchannel coolers for high power chips. IEEE Transactions on Components and Packaging Technologies, vol. 30(2), pp. 218–225, 2007; https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/4214931.

- F. Hong, P. Cheng. Three dimensional numerical analyses and optimization of offset strip-fin microchannel heat sinks. International Communications in Heat and Mass Transfer, vol. 36(7), pp. 651–656, 2009. [CrossRef]

- A.J.L. Foong, N. Ramesh, T.T. Chandratilleke. Laminar convective heat transfer in a microchannel with internal longitudinal fins. International Journal of Thermal Sciences, vol. 48(10), pp. 1908–1913, 2009. [CrossRef]

- Y. Xie, Z. Shen, D. Zhang, J. Lan. Thermal performance of a water-cooled microchannel heat sink with grooves and obstacles. Journal of Electronic Packaging, Transactions of the ASME, vol. 136(2), 021001, 2014. [CrossRef]

- H. Gholami, M. Banaei, A. Eskandari. Investigation of effect of triangular rib in heat transfer of finned rectangular microchannel with extended surfaces. Life Science Journal, vol. 10(8s), pp. 206–211, 2013; http://www.Lifesciencesite.com.

- Y.S. Muzychka. Constructal design of forced convection cooled microchannel heat sinks and heat exchangers. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, vol. 48(15), pp. 3119–3127, 2005. [CrossRef]

- T. Bello-Ochende, L. Liebenberg, J.P. Meyer. Constructal cooling channels for micro-channel heat sinks. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, vol. 50(21–22), pp. 4141–4150, 2007. [CrossRef]

- M.R. Salimpour, M. Sharifhasan, E. Shirani. Constructal optimization of the geometry of an array of micro-channels. International Communications in Heat and Mass Transfer, vol. 38(1), pp. 93–99, 2011. [CrossRef]

- T. Bello-Ochende, J.P. Meyer, F.U. Ighalo. Combined numerical optimization and constructal theory for the design of microchannel heat sinks. Numerical Heat Transfer, Part A: Applications, vol. 58(11), pp. 882–899, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Olakoyejo, T. Bello-Ochende, J.P. Meyer. Mathematical optimisation of laminar forced convection heat transfer through a vascularized solid with square channels. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, vol. 55(9–10), pp. 2402–2411, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Olakoyejo, T. Bello-Ochende, J.P. Meyer. Constructal conjugate cooling channels with internal heat generation. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, vol. 55(15–16), pp. 4385–4396, 2012. [CrossRef]

- A. Bejan. Constructal-theory network of conducting paths for cooling a heat generating volume. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, vol. 40(4), pp. 799–811, 1997. [CrossRef]

- S. Kumar, A. Kumar, A.D. Kothiyal, M.S. Bisht. A review of flow and heat transfer behaviour of nanofluids in micro channel heat sinks. Thermal Science and Engineering Progress, vol. 8, pp. 477–493, 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. Zimmermann, I. Meijer, M.K. Tiwari, S. Paredes, B. Michel, D. Poulikakos. Aquasar: A hot water-cooled data center with direct energy reuse. Energy, vol. 43(1), pp. 237-245, 2012. [CrossRef]

- M.M. Sarafraz, F. Hormozi. Experimental study on the thermal performance and efficiency of a copper made thermosyphon heat pipe charged with alumina-glycol based nanofluids. Powder Technology, vol. 266, pp. 378–387, 2014. [CrossRef]

- M. Nojoomizadeh, A. Karimipour. The effects of porosity and permeability on fluid flow and heat transfer of multi walled carbon nano-tubes suspended in oil (MWCNT/Oil nano-fluid) in a microchannel filled with a porous medium. Physica E: Low-Dimensional Systems and Nanostructures, vol. 84, pp. 423–433, 2016. [CrossRef]

- X.Q. Wang, A.S. Mujumdar. Heat transfer characteristics of nanofluids: a review. International Journal of Thermal Sciences, vol. 46(1), pp. 1–19, 2007. [CrossRef]

- D. Wen, G. Lin, S. Vafaei, K. Zhang. Review of nanofluids for heat transfer applications. Particuology, vol. 7(2), pp. 141–150, 2009. [CrossRef]

- L. Godson, B. Raja, D.M. Lal, S. Wongwises. Enhancement of heat transfer using nanofluids-An overview. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, vol. 14(2), pp. 629–641, 2010. [CrossRef]

- S.M.S. Murshed, C.A. Nieto de Castro, M.J.V. Lourenço, M.L.M. Lopes, F.J.V. Santos. A review of boiling and convective heat transfer with nanofluids. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, vol. 15(5), pp. 2342–2354, 2011. [CrossRef]

- J. Barber, D. Brutin, L. Tadrist. A review on boiling heat transfer enhancement with nanofluids. Nanoscale Research Letters, vol. 6, 280, 2011. [CrossRef]

- T.I. Kim, Y.H. Jeong, S.H. Chang. An experimental study on CHF enhancement in flow boiling using Al2O3 nano-fluid. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, vol. 53(5-6), pp. 1015–1022, 2010. [CrossRef]

- J.M. Wu, J. Zhao. A review of nanofluid heat transfer and critical heat flux enhancement - Research gap to engineering application. Progress in Nuclear Energy, vol. 66, pp. 13–24, 2013. [CrossRef]

- L. Cheng, L. Liu. Boiling and two-phase flow phenomena of refrigerant-based nanofluids: Fundamentals, applications and challenges. International Journal of Refrigeration, vol. 36(2), pp. 421–446, 2013. [CrossRef]

- M. Bahiraei, M. Hangi. Flow and heat transfer characteristics of magnetic nanofluids: A review. Journal of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials, vol. 374, pp. 125–138, 2015. [CrossRef]

- X. Fang, Y. Chen, H. Zhang, W. Chen, A. Dong, R. Wang. Heat transfer and critical heat flux of nanofluid boiling: A comprehensive review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, vol. 62, pp. 924–940, 2016. [CrossRef]

- B.H. Salman, H.A. Mohammed, K.M. Munisamy, A.S. Kherbeet. Characteristics of heat transfer and fluid flow in microtube and microchannel using conventional fluids and nanofluids: A review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, vol. 28, pp. 848–880, 2013. [CrossRef]

- W. Daungthongsuk, S. Wongwises. A critical review of convective heat transfers of nanofluids. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, vol. 11(5), pp. 797–817, 2007. [CrossRef]

- O. Mahian, A. Kianifar, C. Kleinstreuer, M.A. Al-Nimr, I. Pop, A.Z. Sahin, S. Wongwises. A review of entropy generation in nanofluid flow. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, vol. 65, pp. 514–532, 2013. [CrossRef]

- A.M. Hussein, K.V. Sharma, R.A. Bakar, K. Kadirgama. A review of forced convection heat transfer enhancement and hydrodynamic characteristics of a nanofluid. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, vol. 29, pp. 734–743, 2014. [CrossRef]

- A.A. Hussien, M.Z. Abdullah, M.A. Al-Nimr. Single-phase heat transfer enhancement in micro/minichannels using nanofluids: Theory and applications. Applied Energy, vol. 164, pp. 733–755, 2016. [CrossRef]

- S. Kakaç, A. Pramuanjaroenkij. Review of convective heat transfer enhancement with nanofluids. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, vol. 52(13–14), pp. 3187–3196, 2009. [CrossRef]

- W. Yu, D.M. France, E.V. Timofeeva, D. Singh, J.L. Routbort. Comparative review of turbulent heat transfer of nanofluids. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, vol. 55(21–22), pp. 5380–5396, 2012. [CrossRef]

- L.S. Sundar, M.K. Singh. Convective heat transfer and friction factor correlations of nanofluid in a tube and with inserts: A review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, vol. 20, pp. 23–35, 2013. [CrossRef]

- H.A. Mohammed, G. Bhaskaran, N.H. Shuaib, R. Saidur. Heat transfer and fluid flow characteristics in microchannels heat exchanger using nanofluids: A review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, vol. 15(3), pp. 1502–1512, 2011. [CrossRef]

- S.M. Vanaki, P. Ganesan, H.A. Mohammed. Numerical study of convective heat transfer of nanofluids: A review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, vol. 54, pp. 1212–1239, 2016. [CrossRef]

- A. Sabaghan, M. Edalatpour, M.C. Moghadam, E. Roohi, H. Niazmand. Nanofluid flow and heat transfer in a microchannel with longitudinal vortex generators: Two-phase numerical simulation. Applied Thermal Engineering, vol. 100, pp. 179–189, 2016. [CrossRef]

- J. Lee, I. Mudawar. Assessment of the effectiveness of nanofluids for single-phase and two-phase heat transfer in micro-channels. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, vol. 50(3–4), pp. 452–463, 2007. [CrossRef]

- M. Kalteh, A. Abbassi, M. Saffar-Avval, A. Frijns, A. Darhuber, J. Harting. Experimental and numerical investigation of nanofluid forced convection inside a wide microchannel heat sink. Applied Thermal Engineering, vol. 36, pp. 260–268, 2012. [CrossRef]

- H.A. Mohammed, P. Gunnasegaran, N.H. Shuaib. Heat transfer in rectangular microchannels heat sink using nanofluids. International Communications in Heat and Mass Transfer, vol. 37(10), pp. 1496–1503, 2010. [CrossRef]

- E. Manay, B. Sahin. The effect of microchannel height on performance of nanofluids. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, vol. 95, pp. 307–320, 2016. [CrossRef]

- V.A. Martínez, D.A. Vasco, C.M. García-Herrera, R. Ortega-Aguilera. Numerical study of TiO2-based nanofluids flow in microchannel heat sinks: Effect of the Reynolds number and the microchannel height. Applied Thermal Engineering, vol. 161, 114130, 2019. [CrossRef]

- P. Nitiapiruk, O. Mahian, A.S. Dalkilic, S. Wongwises. Performance characteristics of a microchannel heat sink using TiO2/water nanofluid and different thermophysical models. International Communications in Heat and Mass Transfer, vol. 47, pp. 98–104, 2013. [CrossRef]

- M. Heydari, D. Toghraie, O.A. Akbari. The effect of semi-attached and offset mid-truncated ribs and Water/TiO2 nanofluid on flow and heat transfer properties in a triangular microchannel. Thermal Science and Engineering Progress, vol. 2, pp. 140–150, 2017. [CrossRef]

- N. Bouanimba, N. Laid, R. Zouaghi, T. Sehili. A Comparative Study of the Activity of TiO2 Degussa P25 and Millennium PCs in the Photocatalytic Degradation of Bromothymol Blue. International Journal of Chemical Reactor Engineering, 20170014, 2017. [CrossRef]

- N. Laid, N. Bouanimba, A. Ben Ahmede, A. Toureche, T. Sehili. Characterization of ZnO and TiO2 Nanopowders and their Application for Photocatalytic Water Treatment. ACTA PHYSICA POLONICA A, vol. 137(2), 2020. [CrossRef]

- E. Ebrahimnia-Bajestan, M. Charjouei Moghadam, H. Niazmand, W. Daungthongsuk, S. Wongwises. Experimental and numerical investigation of nanofluids heat transfer characteristics for application in solar heat exchangers. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, vol. 92, pp. 1041–1052, 2016. [CrossRef]

- W. Arshad, H.M. Ali. Experimental investigation of heat transfer and pressure drop in a straight minichannel heat sink using TiO2 nanofluid. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, vol. 110, pp. 248–256, 2017. [CrossRef]

- B.C. Pak, Y.I. Cho. Hydrodynamic and heat transfer study of dispersed fluids with submicron metallic oxide particles. Experimental Heat Transfer, vol. 11(2), pp. 151–170, 1998. [CrossRef]

- Y. Xuan, W. Roetzel. Conceptions for heat transfer correlation of nanofluids. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, vol. 43(19), pp. 3701–3707, 2000. [CrossRef]

- U. Rea, T. McKrell, L.W. Hu, J. Buongiorno. Laminar convective heat transfers and viscous pressure loss of alumina-water and zirconia-water nanofluids. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, vol. 52(7–8), pp. 2042–2048, 2009. [CrossRef]

- M. Corcione. Rayleigh-Bénard convection heat transfer in nanoparticle suspensions. International Journal of Heat and Fluid Flow, vol. 32(1), pp. 65–77, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Kandlikar, S. G. Single-phase liquid flow in minichannels and microchannels. Heat Transfer and Fluid Flow in Minichannels and Microchannels, pp.87–136, 2006. [CrossRef]

- I.E. Idelchik, Handbook of Hydraulic Resistance, Hemisphere Publishing, New York, NY; 1986.

- J. Zhang, Y. Diao, Y. Zhao, Y. Zhang. An experimental investigation of heat transfer enhancement in minichannel: Combination of nanofluid and micro fin structure techniques. Experimental Thermal and Fluid Science, vol. 81, pp. 21–32, 2017. [CrossRef]

- R.J. Moffat. Describing the uncertainties in experimental results. Experimental Thermal and Fluid Science, vol. 1(1), pp. 3–17, 1988. [CrossRef]

- M. Mokrane, M. Lounis, M. Announ, M. Ouali, M.A. Djebiret, M. Bourouis. Performance analysis of a micro heat exchanger in electronic cooling applications. Journal of Thermal Engineering, vol. 7(4), pp. 773-790, 2021; https://jten.yildiz.edu.tr/article/34.

- S.V. Patankar. Numerical heat transfer and fluid flow. CRC Press, 1980. [CrossRef]

- P.S. Lee, S.V. Garimella, D. Liu. Investigation of heat transfer in rectangular microchannels. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, vol. 48(9), pp. 1688–1704, 2005. [CrossRef]

- X.F. Peng, G.P. Peterson. Convective heat transfer and flow friction for water flow in microchannel structures. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, vol. 39(12), pp. 2599–2608, 1996. [CrossRef]

- R.K. Shah, A.L. London. Laminar flow forced convection in ducts: a source book for compact heat exchanger analytical data. Academic Press, New York, USA, 1978. [CrossRef]

- T.M. Harms, M.J. Kazmierczak, F.M. Gerner. Developing convective heat transfer in deep rectangular microchannels. International Journal of Heat and Fluid Flow, vol. 20(2), pp. 149-157, 1999. [CrossRef]

- K. Kawano, M. Sekimura, K. Minakami, H. Iwasaki, M. Ishizuka. Development of micro channel heat exchanging. JSME International Journal, Series B: Fluids and Thermal Engineering, vol. 44(4), pp. 592-598, 2001. [CrossRef]

- W. Qu, I. Mudawar. Experimental and numerical study of pressure drop and heat transfer in a single-phase micro-channel heat sink. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, vol. 45(12), pp. 2549–2565, 2002. [CrossRef]

- A.F. Al-Neama, N. Kapur, J. Summers, H.M. Thompson. An experimental and numerical investigation of the use of liquid flow in serpentine microchannels for microelectronics cooling. Applied Thermal Engineering, vol. 116, pp. 709–723, 2017. [CrossRef]

- V. Kumar, J. Sarkar. Experimental hydrothermal behavior of hybrid nanofluid for various particle ratios and comparison with other fluids in minichannel heat sink. International Communications in Heat and Mass Transfer, vol. 110, 104397, 2020. [CrossRef]

| Geometric parameter | Dimension (mm) / Number (-) |

|---|---|

| Heat sink width (W) | 16 |

| Heat sink height (H) | 1.63 |

| Heat sink length (Lmc) | 40 |

| Microchannel width (Wmc) | 0.7 |

| Microchannel height (Hmc) | 1 |

| Half thickness of the solid (es) | 0.35 |

| Thickness of fins (e) | 0.25 |

| Collector tube length (Lc) | 40 |

| Hydraulic diameter (Dh) | 0.8 |

| Collector tube diameter (Dc) | 5 |

| Number of channels (N) | 17 |

| Properties | TiO2 nanoparticles |

|---|---|

| Mean diameter, dp | 20 nm |

| Thermal conductivity, k | 8.4 W/m.K |

| Specific heat, Cp | 710 J/kg.K |

| Density, | 4157 kg/m3 |

| Sensor | Uncertainty |

|---|---|

| K-type thermocouple | ± 0.1°C |

| Pressure sensors | ±2.5 % FS |

| Peristaltic pump | ±1% |

| Heater power supply voltage and current | 0.01% and 0.1% |

| L (mm) | 2.5 |

| W (mm) | 1.25 |

| Parameter | Uncertainty (%) |

| Re | 1.54 |

| ∆P (Pa) | 0.5 |

| h (W/m2.°C) | 2 |

| Nu | 3 |

| Φ (%) | 1 | 5 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tin (°C) | 35 | 45 | 55 | 65 | 35 | 45 | 55 | 65 | |

| Re | |||||||||

| 400 | 26% | 24% | 23% | 21% | 37% | 35% | 32% | 30% | |

| 800 | 35% | 32% | 30% | 28% | 52% | 49% | 47% | 45% | |

| 1200 | 44% | 42% | 40% | 39% | 60% | 57% | 55% | 53% | |

| 2000 | 57% | 56% | 54% | 49% | 70% | 65% | 63% | 59% | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).