Submitted:

20 April 2024

Posted:

23 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

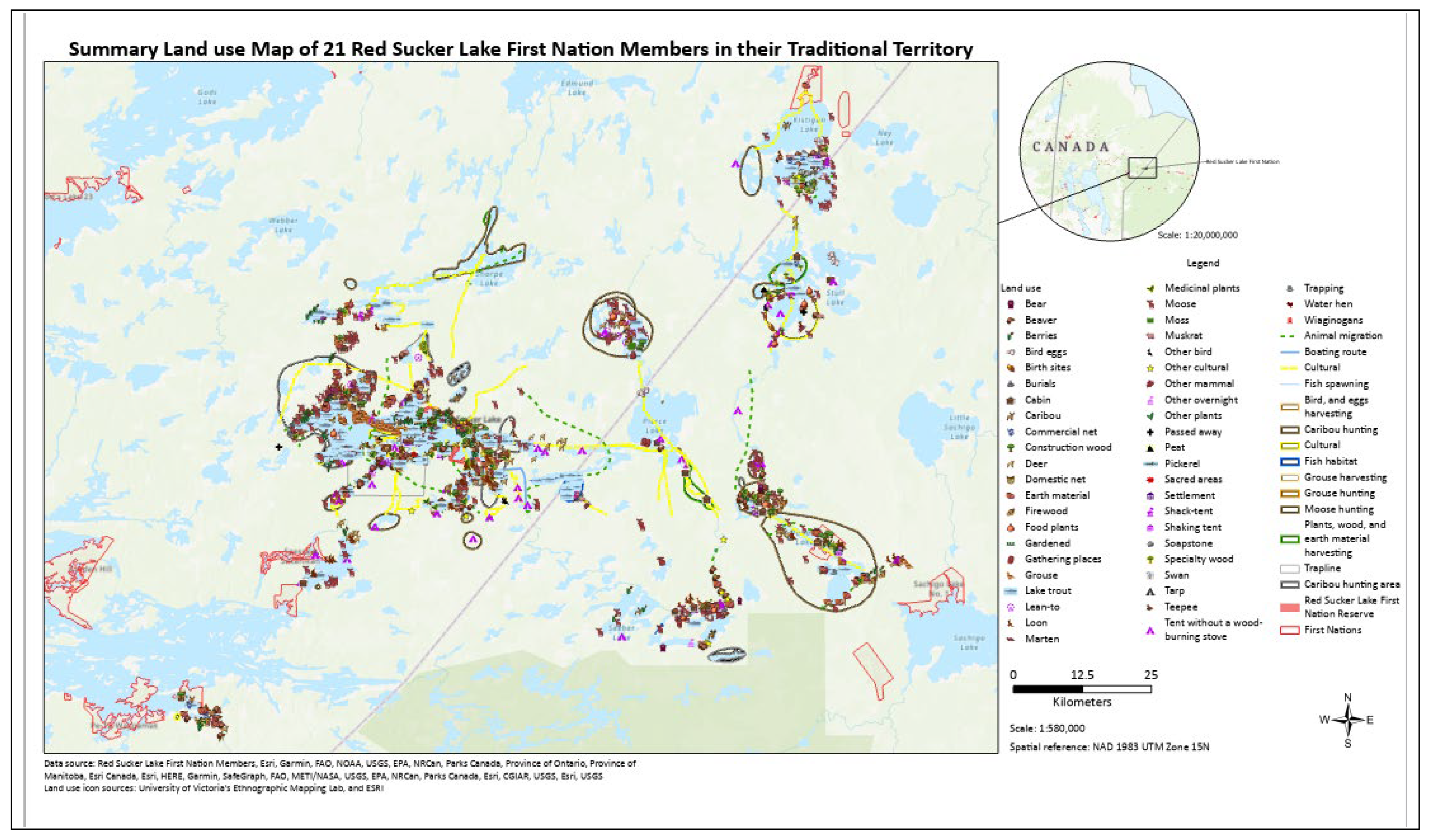

3.1. Land Use of Red Sucker Lake First Nation Community Members

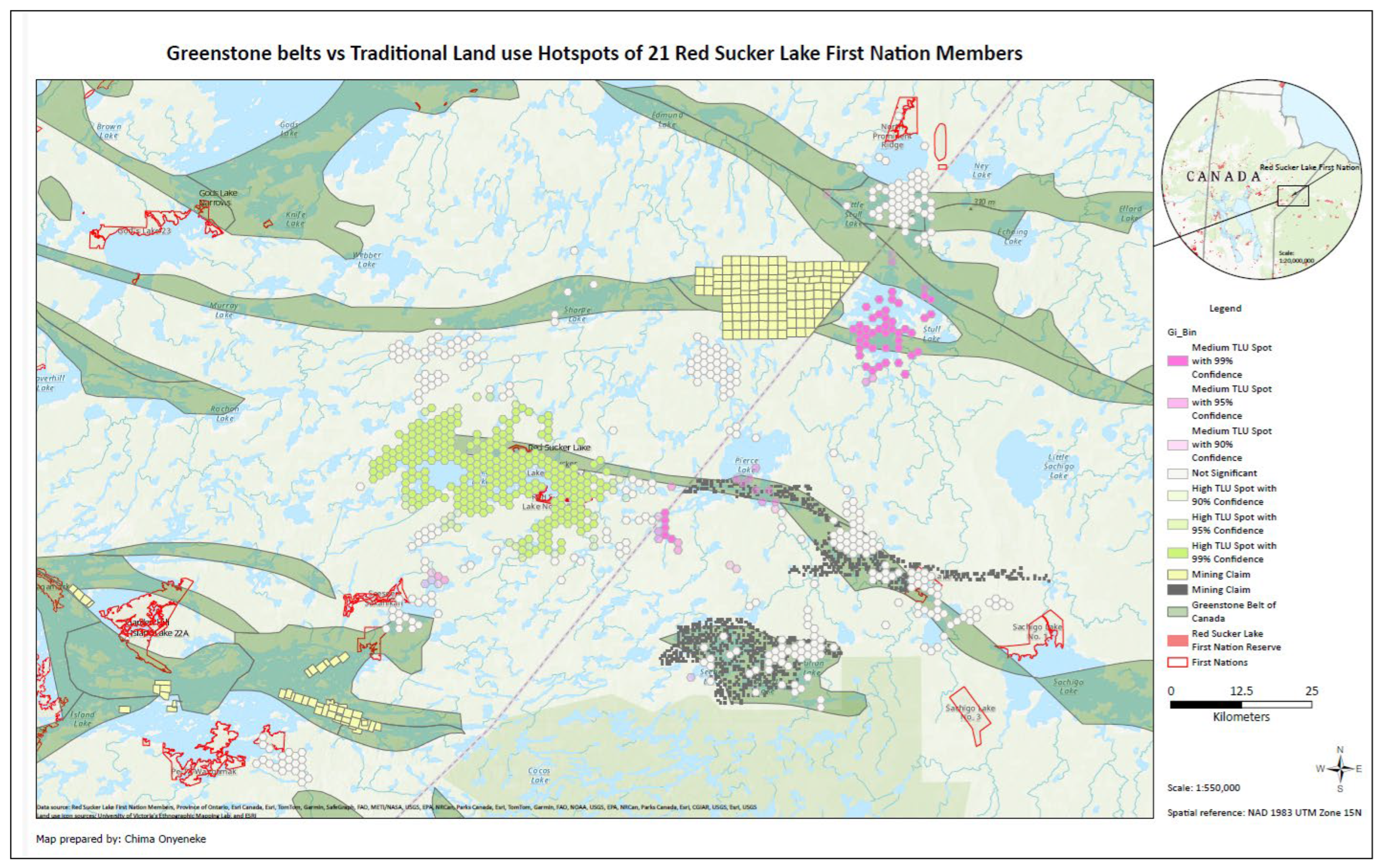

3.1.1. Traditional Land Uses Heavily Impacted by Exploration and Mining Activities

3.1.2. Overlap of Traditional LAND use Hotspots and Greenstone Belts

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Indigenous peoples defend Earth's biodiversity—but they're in danger. Available online: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/article/can-indigenous-land-stewardship-protect-biodiversity- (accessed on 23 March 2024).

- Raygorodetsky, G. Of Swiddens, snakes, and honey. Biodiversity 2018, 19(3-4), 244-247.

- Vogel, B.; Yumagulova, L.; McBean, G.; Charles Norris, K. A. Indigenous-Led Nature-Based Solutions for the Climate Crisis: Insights from Canada. Sustainability 2022, 14(11), 25–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUCN. Journeys to more equitable and effective conservation: the central role of Indigenous peoples and local communities. Available online: https://www.iucn.org/neww/202308/journeys-more-equitable-and-effective-conservation-central-role-indigenous-peoples-and (accessed on 23 March 2024).

- Hill, S. L. The Autoethnography of an Ininiw from God’s Lake, Manitoba, Canada: First Nation Water Governance Flows from Sacred Indigenous Relationships, Responsibilities and Rights to Aski. Doctorate Thesis, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Manitoba Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, S.; Harper, V.; Whiteway, N. Let’s keep our Land sacred as the Creator taught us: Wasagamack First Nation Ancestral Land Use. Winnipeg: Manitoba First Nations Education Resource Centre, Manitoba, Canada, 2020; pp. 1-63. Available online: http://ecohealthcircle.com/book-lets-keep-our-land-sacred-as-the-creator-taught-us/ (accessed on 13 July 2022).

- Webb, J. Indigenous-led conservation in the Amazon: A win-win-win solution. Available online: https://www.amazonfrontlines.org/chronicles/indigenous-conservation-amazon/ (accessed on 22 September 2021).

- Malcolm, M. A deeply troubling discovery: Earth may have already passed the crucial 1.50C warming limit. Available online: https://www.theconversation.com/a-deeply-troubling-discovery-earth-may-have-already-passed-the-crucial-1-5-c-warmking-limit-222601 (accessed on 23 March 2024).

- Whyte, K. Too late for indigenous climate justice: Ecological and relational tipping points. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change 2020, 11(1), e603.

- Mansuy, N.; Staley, D.; Alook, S.; Parlee, B.; Thomson, A.; Littlechild, D.B.; Munson, M.; Didzena, F. Indigenous protected and conserved areas (IPCAs): Canada's new path forward for biological and cultural conservation and Indigenous well-being. FACETS 2023, 8(): 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Nitah, S. Indigenous peoples proven to sustain biodiversity and address climate change: Now it’s time to recognize and support this leadership. One Earth 2021, 4. 907-909. 10.1016/j.oneear.2021.06.015.

- Huseman, J.; Short, D. A slow industrial genocide: tar sands and the indigenous peoples of northern Alberta. The International Journal of Human Rights 2012, 16(1), 216–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohn, M; Reddy, K. Colonialism. In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 8th ed.; Edward, N. Z., Uri N., Eds.; Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, California, United States, 2023. Available online:https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2023/entries/colonialism/.

- Thapa, K.; Thompson, S. Applying Density and Hotspot Analysis for Indigenous Traditional Land Use: Counter-Mapping with Wasagamack First Nation, Manitoba, Canada. Journal of Geoscience and Environment Protection 2020, 8, 285–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, S.; Thapa, K.; Whiteway, N. Sacred Harvest, Sacred Place: Mapping harvesting sites in Wasagamack First Nation. Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development 2019, 9 (1), 1-29. [CrossRef]

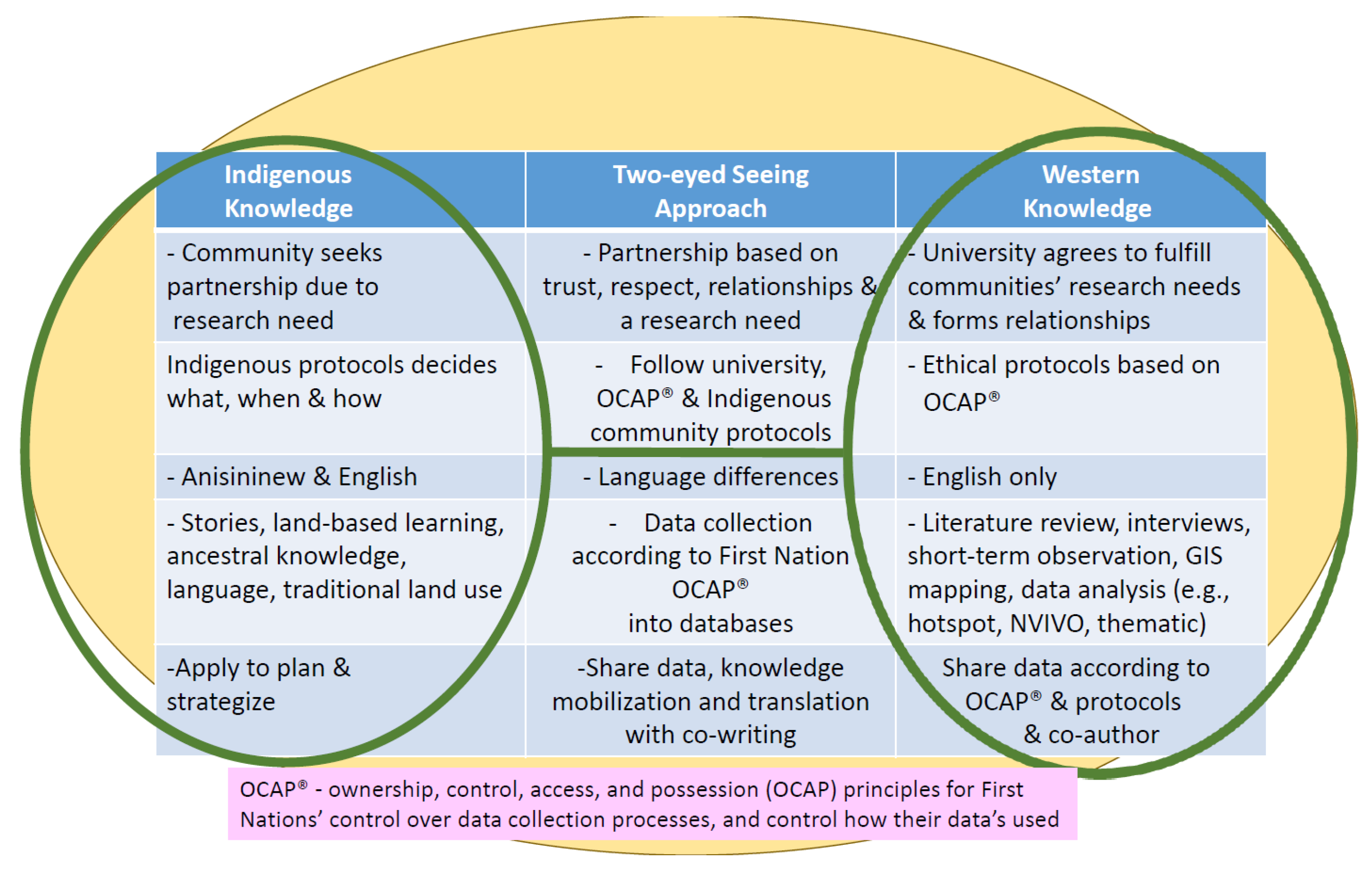

- Iwama, M.; Marshall, M.; Marshall, A.; Bartlett, C. Two-eyed seeing and the language of healing in community-based research. Canadian Journal of Native Education 2009, 32(2), 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, D. E.; Thompson, S.; Ballard, M.; Linton, J. Two-eyed seeing in research and its absence in policy: Little Saskatchewan First Nation Elders' experiences of the 2011 flood and forced displacement. The International Indigenous Policy Journal 2017, 8(4), 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltier, C. An Application of Two-Eyed Seeing: Indigenous Research Methods with Participatory Action Research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 2018, 17, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimmer, R. W. Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants. Milkweed Editions, 2013.

- Kovach, M. Indigenous Methodologies: Characteristics, Conversations, and Contexts. University of Toronto Press: Toronto, Canada, 2009; pp. 2-16.

- Wilson, S.; Hughes, M. Why Research is Reconciliation. In Research and Reconciliation: Unsettling Ways of Knowing through Indigenous Relationships, S. Wilson, A. V. Breen, & L. DuPre, Eds.; Canadian Scholars: Toronto, Canada, 2019; pp. 5–19. [Google Scholar]

- Indigenous Circle of Experts’ Report and Recommendation. We Rise Together: Achieving Pathway to Canada Target 1 through the creation of Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas in the spirit and practice of reconciliation. Available online: https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2018/pc/R62-548-2018-eng.pdf. https://doi.org/10.1139/er-2022-0087 (accessed on 22 November 2023).

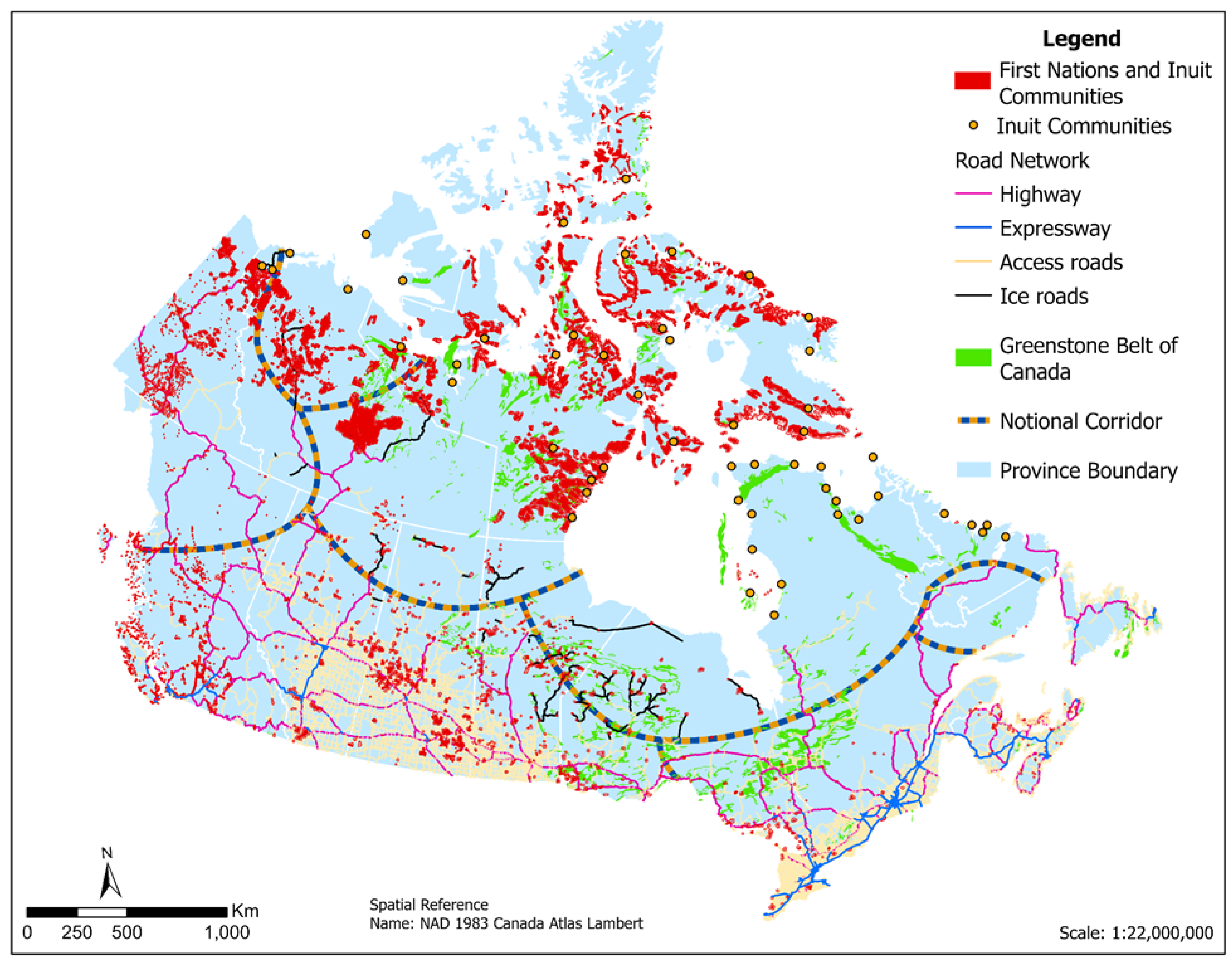

- Thompson, S.; Hill, S.; Salles, A.; Ahmed, T.; Adegun, A.; Nwankwo, U. The Northern Corridor, Food Insecurity and the Resource Curse for Indigenous Communities in Canada. The School of Public Policy Publications 2023, 15(40), pp. 1-44. [CrossRef]

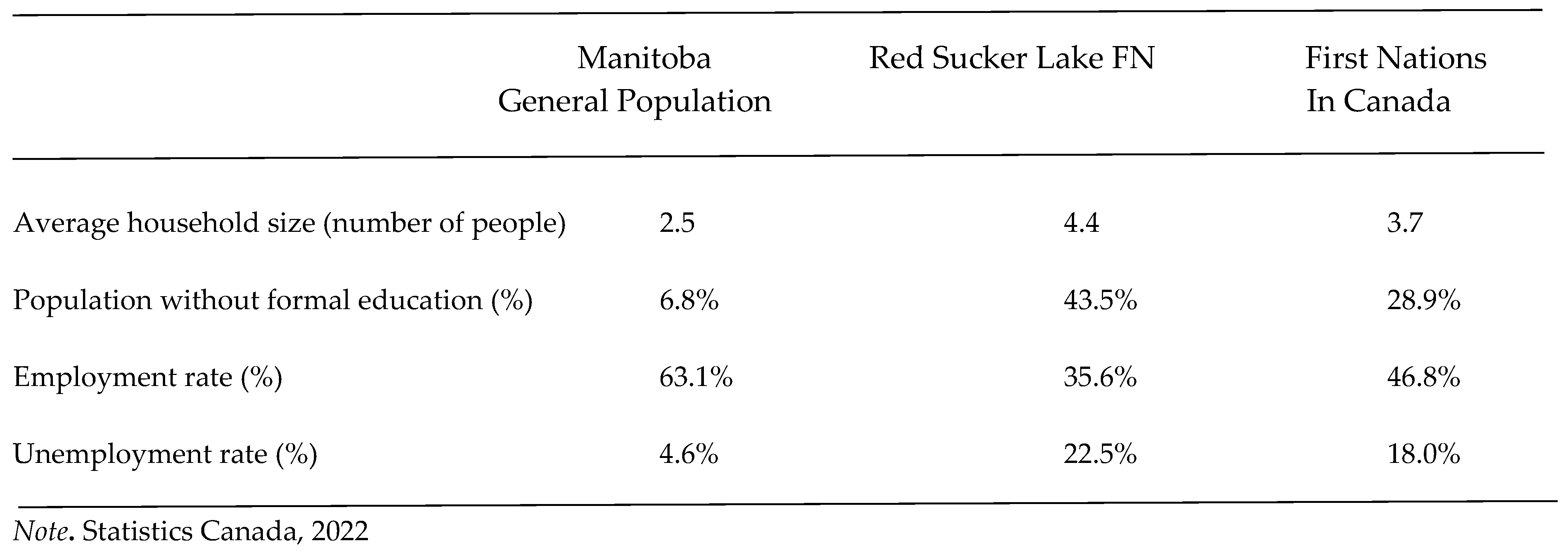

- Statistics Canada. Census Profile. 2021 Census of Population. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 98-316-X2021001. Ottawa. Released April 27, 2022. Available online: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census (accessed on 11 September 2022).

- International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. Available online: https://www.web.archive.org/web/201203030011412/https:/www2.ohchr.org/english/law/ccpr.htm Archived March 3, 2012. (accessed on 09 April 2024).

- International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. Available online: https://www.web.archive.org/web/20120303114220/https:/www2.ohchr.org/english/law/cescr.htm. Archived March 3, 2012 (accessed on 09 April 2024).

- United Nations. United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), 2007. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/wp-content/uploads/sites/19/2018/11/UNDRIP_E_web.pdf (accessed on 23 March 2024).

- Indigenous Foundations. UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Available online: https://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/un_declaration_on_the_rights_of_indigenous_peoples/ (accessed on 10 April 2024).

- Blacksmith,C.; Thompson, S.; Hill, S.; Thapa, K.; Stormhunter, T. The Indian Act Virus Worsens COVID-19 Outcomes for Canada’s Native People. Canadian Yearbook on Human Rights’ special issue on COVID-19, 2021. Ottawa: University of Ottawa Centre for Human Rights Press.

- Fontana, L. B.; Grugel, J. The politics of Indigenous participation through “free prior informed consent”: Reflections from the Bolivian case. World Development 2016, 77, 249–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations for Indigenous people. Free, Prior, and Informed Consent: An Indigenous peoples’ right and a good practice for local communities. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/publications/2016/10/free-prior-and-informed-consent-an-indigenous-peoples-right-and-a-good-practice-for-local-communities-fao/ (accessed on 14 October 2023).

- Schnarch, B. Ownership, control, access, and possession (OCAP) or self-determination applied to research: A critical analysis of contemporary First Nations research and some options for First Nations communities. International Journal of Indigenous Health 2004, 1(1), 80–95. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, L.; Barry, J. Planning for Coexistence? Recognizing Indigenous Rights Through Land-Use Planning in Canada and Australia. Routledge, New York, USA, 2016.

- Mazzocchi, F. Western science and traditional knowledge. EMBO Reports 2006, 7(5), 463–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aikenhead, G. S.; Ogawa, M. Indigenous knowledge and science revisited. Cultural Studies of Science Education 2007, 2(3), 539–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGregor, D. Coming full circle: Indigenous knowledge, environment, and our future. American Indian Quarterly 2004, 28(3/4), 385-410.

- Lines, L. A.; Jardine, C. G. Connection to the land as a youth-identified social determinant of Indigenous Peoples’ health. BMC Public Health 2019, 19(1), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquina-Márquez, A.; Virchez, J.; Ruiz-Callado, R. Postcolonial Healing Landscapes and Mental Health in a Remote Indigenous Community in Subarctic Ontario, Canada. Polar Geography 2016, 39(1), 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhnlein, H.V.; Receveur, O. Dietary Change And Traditional Food Systems Of Indigenous Peoples. Annual Review of Nutrition 1996, 16(1), 417–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Report of the First Nations Regional Health Survey. First Nations Information Governance Centre 3(1) (March). https://www.fnigc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/53b9881f96fc02e9352f7cc8b0914d7a_FNIGC_RHS-Phase-3-Volume-Two_EN_FINAL_Screen.pdf. (accessed on 9 April 2024).

- Chan, L.; Malek, B.; Tonio, S.; Tikhonov, C.; Schwartz, H.; Fediuk, K.; Ing, A.; Marushka, L.; Lindhorst, K.; Barwin, L.; Berti, P.; Singh, K.; Receveur, O. FNFNES Final Report for Eight Assembly of First Nations Regions: Draft Comprehensive Technical Report. In Proceedings of the Assembly of First Nations, University of Ottawa, Université de Montréal, Canada; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, L, Malek B; Tonio S., Tikhonov, C.; Schwartz, H.; Fediuk, K.; Ing, A.; Marushka, L.; Lindhorst, K.; Barwin, L.; Berti, P.; Singh, K.; Receveur, O. Corrigendum to the FNFNES Final Report for Eight Assembly of First Nations Regions: Draft Comprehensive Technical Report. November 2021. FNFNES. Available online: https://www.fnfnes.ca/researcher-docs/FNFNES_National_Report_Corrigenda_2021-10-27.pdf (accessed on 28 March 2024).

- Havranek, T.; Horvath, R.; Zeynalov, A. Natural Resources and Economic Growth: A Meta-Analysis. World Development 2016, 88: 134-51.

- The Indian Act, "An Act to Amend and Consolidate the Laws Respecting Indians," Ottawa: Government of Canada, 1876, sec 12. Available online: https://nctr.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/1876_Indian_Act_Reduced_Size.pdf (accessed on 29 March 2024).

- King, H. Land Back: A Yellowhead Institute Red Paper, Yellowhead Institute, 2019, pp. 8-44. Available online: https://redpaper.yellowheadinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/red-paper-report-final.pdf. (accessed on 28 March 2024).

- Bakx, K. Alberta's Bearspaw First Nation Fighting Federal Government for Right to Manage Own Savings, CBC News. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/calgary/bakx-bearspaw-first-nation-government-savings-1.6117818 (accessed on 27 July 2021).

- The National Aboriginal Economic Development Board, "Recommendations on First Nations Access to Indian Moneys," 2017, p. 16. Available online: http://www.naedb-cndea.com/reports/recommendations-on-first-nations-access-to-indian-moneys.PDF (accessed on 8 April 2024).

- Adegun, A.; Thompson, S. Higher COVID-19 rates in Manitoba's First Nations compared to non-First Nations linked to limited infrastructure on reserves. Journal of Rural and Community Development 2021, 16, 4. [Google Scholar]

- The Free Press: Judge nixes stop work order; miner forges on. Available online: https://www.winnipegfreepress.com/business/2013/07/05/judge-nixes-stop-work-order-miner-forges-on (accessed on 30 March 2024).

- IPCC. AR6 Synthesis Report: Climate Change 2023; IPCC: Geneva Switzerland, 2023. Available online: https://www.report.ipcc.ch/ar6 syr/pdf/IPCC_AR6_SYR_SPM.pdf (accessed on 3 January 2023). IPCC.

- USEPA. USEPA. Using a Total Environment Framework (Built, Natural, Social Environments) to Assess Life-long Health Effects of Chemical Exposures Request for Applications (RFA); U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/research-grants/using-total-environment-framework-built-natural-social-environments-assess-life (accessed on 13 April 2023).

- IEA. World Energy Outlook. IEA: Paris, France, 2022. Available online: https://www.iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/830fe099-5530-48f2-a7c1-11f35d510983/WorldEnergyOutlook2022.pdf (accessed on 3 January 2023).

- Thompson, S. Strategic Analysis of the Renewable Electricity Transition: Power to the World without Carbon Emissions? Energies 2023. Vol. 16 (17), 6183. [CrossRef]

- IEA (2021). The Role of Critical Minerals in Clean Energy Transitions, IEA, Paris. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/the-role-of-critical-minerals-in-clean-energy-transitions, Licence: CC BY 4.0. (accessed on 8 April 2024).

- Davies, M.; Swilling, M.; Wlokas, H.L. Towards New Configurations of Urban Energy Governance in South Africa’s Renewable Energy Procurement Programme. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2018, 36, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viebahn, P.; Soukup, O.; Samadi, S.; Teubler, J.; Wiesen, K.; Ritthoff, M. Assessing the Need for Critical Minerals to Shift the German Energy System Towards a High Proportion of Renewables. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 49, 655–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seibert, M.K.; Rees, W.E. Through the Eye of a Needle: An Eco-Heterodox Perspective on the Renewable Energy Transition. Energies 2021, 14, 4508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaux, S.P. The Mining of Minerals and the Limits to Growth; Geological Survey of Finland: Espoo, Finland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Manitoba’s mineral industry: Exploration and development highlights 2014. Available online: https://www.gov.mb.ca/iem/industry/exp-dev/highlights2014.html (accessed on 23 March 2024).

- Tükenmez, M.; Demireli, E. Renewable Energy Policy in Turkey with the New Legal Regulations. Renew. Energy 2012, 39, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackah, I.; Graham, E. Meeting the Targets of the Paris Agreement: An Analysis of Renewable Energy (RE) Governance Systems in West Africa (WA). Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2021, 23, 501–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Impact Assessment Agency of Canada. Government of Canada. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/impact-assessment-agency.html (accessed on 23 March 2024).

- Sulzenko, A.; Fellows, G.K. Planning for Infrastructure to Realize Canada’s Potential: The Corridor Concept. The School of Public Policy Publications 2016, 9(22). [CrossRef]

- Fellows, G. K.; Tombe, T. Gains from Trade for Canada’s North: The Case of a Northern Infrastructure Corridor. The School of Public Policy Publications 2016, 10(2). [CrossRef]

- Tombe, T.; Munzur, A.; Fellows, G.K. Implications of an Infrastructure Corridor for Alberta’s economy. The School of Public Policy Publications 2021, 14(1). [CrossRef]

- Mansuy, N.; Staley, D.; Alook, S.; Parlee, B.; Thomson, A.; Littlechild, D.B.; Munson, M.; Didzena, F. Indigenous protected and conserved areas (IPCAs): Canada's new path forward for biological and cultural conservation and Indigenous well-being. FACETS 2023, 8(): 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Nitah, Steve. Indigenous peoples proven to sustain biodiversity and address climate change: Now it’s time to recognize and support this leadership. One Earth 2021, 4. 907-909. 10.1016/j.oneear.2021.06.015.

- IPCC, 2019. Climate Change and Land: an IPCC special report on climate change, desertification, land degradation, sustainable land management, food security, and greenhouse gas fluxes in terrestrial ecosystems. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/srccl/ (accessed on 2 April 2024).

- Ginger, G.; Ford, R.; Firelight Group. Implementing Indigenous Protected and Conserved Area Agreements in Canada: A Review of Successes, Challenges, and Realities. Available online: https://makeway.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/Firelight-Makeway-IPAs-April-28-2023.pdf (accessed on 2 April 2023).

- Wildlife Conservation Society Canada. Northern Peatlands in Canada. An Enormous Carbon Storehouse. Available online: https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/19d24f59487b46f6a011dba140eddbe7 (accessed on 10 April 2024).

- Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada. Red Sucker Lake First Nation Detail. AANDC. https://fnp-ppn.aadnc-aandc.gc.ca/fnp/Main/Search/FNMain.aspx?BAND_NUMBER=300&lang=eng. (accessed on 25 February 2024).

- Onyeneke, C. Mining impact and Indigenous protected and conserved areas. Master's thesis, University of Manitoba, Manitoba Canada, 2023. https://mspace.lib.umanitoba.ca/server/api/core/bitstreams/a15289fe-a9b1-427c-b922-b4c974808d62/content.

- Olson, R.; Hackett, J.; DeRoy, S. Mapping the digital terrain: towards Indigenous geographic information and spatial data quality indicators for indigenous knowledge and traditional land-use data collection. The Cartographic Journal 2016, 53(4), 348–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, K. Indigenous land rights and Indigenous land use planning: Exploring the relevance and significance to Wasagamack First Nation, northern Manitoba, Canada. Master's thesis, University of Manitoba, Manitoba Canada, 2018.

- Blair, Erik. A reflexive exploration of two qualitative data coding techniques. Journal of Methods and Measurement in the Social Sciences 2015, 6 (1) 14-29.

- Esri Canada. Optimized Hotspot Analysis. Available online: https://www.pro.arcgis.com/en/pro-app/latest/tool-reference/spatial-statistics/optimized-hot-spot-analysis.htm (accessed on 26 February 2023).

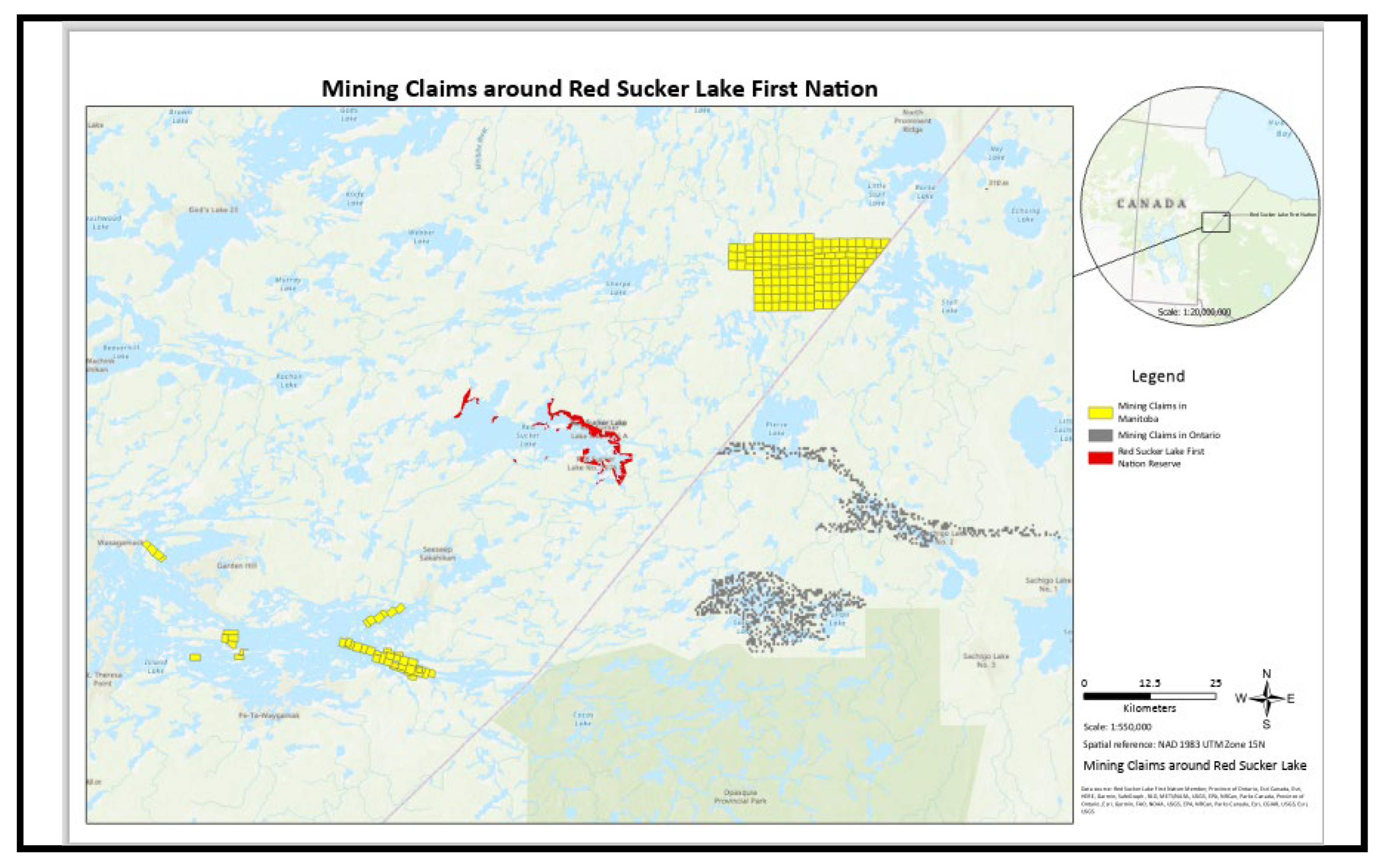

- Ministry of Northern Development and Mines. Available online: https://www.ontario.ca/page/ministry-mines (accessed on 20 May 2023).

- Integrated Mining and Quarrying System. Available online: https://web33.gov.mb.ca/imaqs/ (accessed on 11 October 2022).

- Shafabakhsh, G. A.; Famili, A.; Bahadori, M. S. GIS-based spatial analysis of urban traffic accidents: Case study in Mashhad, Iran. Journal of Traffic and Transportation Engineering (English Edition) 2017, 4(3), 290–299. [CrossRef]

- Grubesic, T. H.; Murray, A. T. Constructing the divide: Spatial disparities in broadband access. Papers in Regional Science 2002, 81, 197–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, S.; Thapa, K. Red Sucker Lake First Nation Ancestral Land Use and Traditional Activities Report. Natural Resources Institute, University of Manitoba, Manitoba Canada. Personal communication, 2018.

- Manitoba government. Manitoba’s Provincial Planning Act (81/2011). Available online: https://web2.gov.mb.ca/laws/regs/current/_pdf-regs.php?reg=81/2011 (accessed on 13 July 2023).

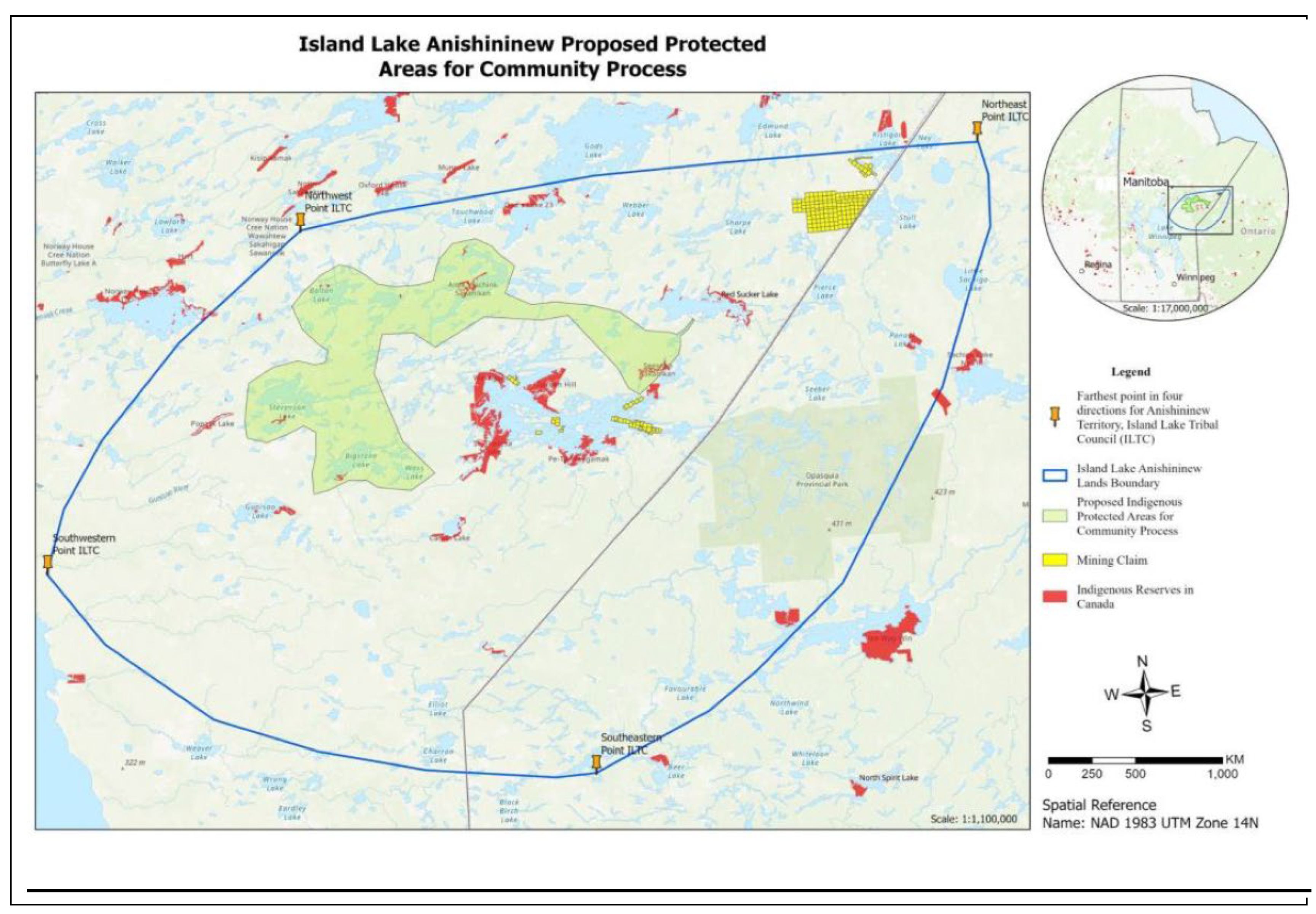

- Island Lake Tribal Council. Indigenous protected Island Lake Region Expression of Interest (EOI) for Indigenous-Led Area-Based Conservation (ILABC), Environment Canada funding application, 2023.

- Rezende, C. L.; Scarano, F. R.; Assad, E. D.; Joly, C. A.; Metzger, J. P.; Strassburg, B. B. N.; Mittermeier, R. A. From hotspot to hopespot: An opportunity for the Brazilian Atlantic Forest. Perspectives in ecology and conservation 2018, 16(4), 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huff, A. Indigenous land rights and the new self-determination. Colo. J. Int'l Envtl. L. & Pol'y 2005, 16, 295. [Google Scholar]

- Catovsky, S.; Bradford, M. A.; Hector, A. Biodiversity and ecosystem productivity: implications for carbon storage. Oikos 2002, 97(3), 443–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakharchenko, N. V.; Hasanov, S. L.; Yumashev, A. V.; Admakin, O. I.; Lintser, S. A.; Antipina, M. I. Legal Rationale of Biodiversity Regulation as a Basis of Stable Ecological. Journal of Environmental Management & Tourism 2018, 9(3 (27)), 510-523.

- Wardle, D. A.; Jonsson, M.; Bansal, S.; Bardgett, R. D.; Gundale, M. J.; Metcalfe, D. B. Linking vegetation change, carbon sequestration and biodiversity: insights from island ecosystems in a long-term natural experiment. Journal of Ecology 2012, 100(1), 16–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacArthur, J. L.; Hoicka, C. E.; Castleden, H.; Das, R.; Lieu, J. Canada's Green New Deal: Forging the socio-political foundations of climate resilient infrastructure. Energy Research & Social Science 2020, 65, 101442. [Google Scholar]

- Hayden, A. When green growth is not enough: Climate change, ecological modernization, and sufficiency. McGill-Queen's Press-MQUP: Ontario, Canada, 201.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).