1. Introduction

The working field of healthcare can be challenging in terms of maintaining personal and structural resources and stressful working conditions [1,2,3]. The demanding nature of healthcare professions daily workload, characterised by the need for constant vigilance, critical thinking, managing high caseloads and prioritising tasks as well as the emotional toll of patient care, challenges the individual in the high-pressure work environment of healthcare settings [4]. In addition to difficulties in daily work situations, changes in demography and increases in disease prevalence are happening to which health professionals must adapt to continue providing high-quality care [5,6]. Neurodegenerative diseases like dementia are multifactorial illnesses in need of special knowledge and treatments. This appears complicated with a view to the rising prevalence of diseases like dementia in the past decades due to rising life expectancy and decreasing mortality of the population [7]. As dementia is an irreversible, neurocognitive syndrome, patients can only be supported in their existing functionality and are in need to be cared for according to the symptoms of the disease. To provide extensive and high-quality care for people with dementia while managing rising prevalence rates, it is crucial to have precise knowledge about diverse symptoms and forms of dementia to offer suitable nursing, therapeutic or psychosocial treatment options [6,7]. It is known that professional experiences and knowledge are prognostic factors of the quality of a professional’s treatment [8]. Facing demographic changes and various needs of people with dementia, it is essential for health professionals to continuously inform themselves about such diseases [9,10]. On the one hand, there is the necessity as research has represented the importance of knowledge to manage uncertainty as well as change processes which happen to be main work stressors not only in critical but daily healthcare situations [3,11,12]. On the other hand, health professionals report problems of information overload and problems of orientation regarding changing needs of patients in complex working fields [13]. Digital learning environments might help facing these challenges in healthcare by preventing filter problems of relevant information, structuring clarifying contexts of meaning for complex diseases and embedding the constant learning requirements closer in the everyday work life of health professions [14].

The implementation of digital education is a flexible solution that is already widely used in education for health care professions [6,15]. Providing digital education can help saving time, budget, and room capacities both for educating facilities and learners [6,16]. They can further facilitate the process of self-regulated learning, helping the learner implement their own learning structures [17,18]. However, the positive effects of digital learning may be diminished, when a learning programme does not match the learning preferences, learning difficulty or interests of the learner so that he or she is forced to adapt to the unusual learning structures presented. The learner may be prevented from reaching flow conditions, in which the learning process is perceived as optimal in terms of challenge and ability of the learner and task [19]. Furthermore, generic material could influence the learner’s perceived locus of control, sense of value of the material and self-esteem negatively [20].In consequence the learner (here: health professional) may be demotivated and reject the learning material or will finish learning tasks only to meet given requirements [19,20]. Learning environments should therefore fit the learner’s learning habits to reduce complexity in learning processes and keep learners motivated while assisting in transferring schemes from learning content to actual working situations, making it accessible and applicable in the daily work with patients and [21]. For specific personnel like rural and remote working health professionals, it may be further necessary to have flexible access possibilities to ensure ongoing dementia learning [22]. In conclusion, for multifactorial and transdisciplinary treated diseases like dementia there should be learning solutions flexible in reception date, location and complexity of the content which are able to depict the multi-layered behaviours, needs of communication and special personality features of persons with dementia to the extent that is needed for learner and patient [23, 24]. Hence, composing a learner-centred programme for long-term education may be a first step to ensure continued implementation of high-quality dementia care.

To establish this learning solution, a shift of overall learning culture from process-focused learning to competency-based learning, altering the focus to the learner rather than the teacher, may support the learner in his individual process [13]. It is shown that learners are likely to be intrinsically motivated from learning programmes that fit their needs, whereas generic learning tools may provoke reactance for learning behaviour [7,25]. Consequently, the learning success itself might be dependent on a personalised presentation of learning material [13]. To promote self-determined learning and support the users´ motivation to actively engage in new learning content, the learning system should analyze learning preferences in the first place and further recommend suitable learning content based on habits and previous knowledge given by the users [26]. Recommender systems as a form of AI can support the self-regulation learning process in that way [27,28]. As eliciting valuable information can be a difficult process, recommender systems help users choose information based on personal needs and previous information given. However, in the process of designing recommender systems occurs a problem that informatics call the cold-start-problem [26,27]. This problem is defined as in initial data sets, there happen to be not sufficient data points for the system to adapt to the individual needs and preferences [26].

One way to solve this cold-start-problem is the collaborative filtering method that manages to recommend items to users which were also preferred by similar users [26]. Among healthcare professionals these similar users may be held distinctive by shared learning experiences in terms of belonging to their profession as well as qualification and experience [6]. Physicians tend to learn while working and with a focus on practical experience [28,29], Nurses seem to prefer the communication with colleagues over auditory material, while nursing and medicine students prefer multimodal – and overall digital education [30]. Hence, it appears useful to cluster these various and shared preferences and make learning personae comparable in that way. Personae are models of distinct real users of a programme which are inherent of the behaviors and motivations of this kind of user regarding one topic [31]. They can be seen as hypothetical users and are lively constructed with personal attributes and goals to give an insight in the user’s needs. Instead of gathering quantitative data about each user with possible high economical costs, persona modelling can be an efficient way to create behavioral archetypes of real users in order to depict the interaction of a user with a programme or topic [32,33]. Personae are commonly built in participative ways to gather a variety of individual characteristics for one type of (here:) healthcare professionals. Participative approaches are a method to gather vivid information about personal characteristics of targeted users [34]. By sharing experiences and needs, possible future needs as well as uses of an intervention may be imaginated to ensure a tailored and effective programme in terms of behavior-adapted design [35,36]. Another advantage may be the improved inclusivity of a programme as well as the empowerment of learners as co-engineers whilst profiting from first-hand practical knowledge and further reinforcing self-regulated learning processes in learners [36,37]. In this study, participatory approaches are used to improve the congruence between the learning perceptions and needs of health professionals and theoretical insights of the interdisciplinary research team (here: as engineers) by establishing a collaborative design process of the learning material [37].

The aim of this study is to gain knowledge about learning preferences to construct didactic personae including distinct didactic requirements of various German healthcare professions. Besides didactic needs, subject to this study is to identify the main knowledge gaps and therefore most relevant learning themes in dementia care. These thematic results will be presented in another publication. In the light of the multifactorial nature of dementia and multidisciplinary treatment needs and to extend the usability of the intervention to a broad number of persons, it was found useful to gather various groups of professionals with different levels of training and experience in dementia care. The results of this qualitative study are placed in the context of an interdisciplinary project that aims to develop, implement, and evaluate a digital intervention, here, an adaptive learning platform for healthcare professionals and other personnel in dementia care. The MINDED.RUHR- project is a ministry-supported project funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) and supported by the Federal Institute for Vocational Training (BIBB). The present study is embedded in the subproject MR_UWH “Development and preparation of individual learning content using the example of challenging behaviour of people living with dementia”.

This results in the following research questions for the current study: What are the learning habits of health professions regarding ideal learning structures, challenges, and transfers to the workplace? How do various health professions differ in their learning habits and needs?

2. Materials and Methods

Ethical approval was obtained from the ethics committee of Witten Herdecke University, Germany (210/2021).

To identify the learning requirements of health professionals regarding dementia care and implement the first step of the framework for design and evaluation of digital health interventions (DEDHI), focus group interviews were conducted. This method was used to initiate the participative design process by gathering didactic information about general learning associations, learning habits, maintaining learning motivation, the handling of frustrations while learning and challenges of transferring knowledge into the daily work life of health professionals. Other methodical advantages were emerging group identification processes, which can help clarify the perspective of the group in comparison to individual survey methods [38,39]. This was done to initiate a participative design process in the character of a round table, on which opinions and values of the target group can be expressed [40].

In addition, the existing knowledge about dementia care and previous experiences were gathered out of a care science perspective. The participants of the study were health professionals with different levels of care work experience as well as thematic knowledge of dementia and related care implications to guarantee an extensive overview of the learning target group [6]. Nursing care students as well as experienced professionals in stationery and outpatient services and stationary working nursing professions of different experience levels as well as physicians represented the participants in the focus groups. In addition, relevant health professionals with more infrequent but intense points of contact to people with dementia were integrated. These were represented by physiotherapists, patient serving personnel as well as facility managers in this study.

To ensure the structure of the focus group interviews, a semi-structured interview guide was implemented. Beforehand, the guide was tested in pilot interviews by students of care science and human medicine at the Witten/Herdecke University (UW/H). This took place both digitally and in presence to ensure the fit of the structure focus group inter-views even for facilities with contact precautions due to Covid-19. However, it was planned and preferred to hold the interviews on site at the care institutions. The semi-structured interview was chosen to guarantee openly expressed viewpoints of the participants as opposed to a questionnaire or fully structured interview [41]. It contained six didactic main questions regarding previous learning habits in the workplace, ideal conceptions of learning material, information about personal learning flow moments as well as previous work situations with learning transfer possibilities. The didactic part of the interview was closed with a question to identify previous points of discontinuation while learning and challenges while trying to transfer knowledge to daily work situations. In addition, thematic questions were included regarding the specific problems and transfer possibilities of dementia care knowledge. The main questions were accompanied by sub questions to ensure specified answers and to guide the participants to their previous learning experiences and reactions. Furthermore, structural directions as well as time units for each question were defined in order to keep the focus group interview fluent.

The recruitment process took place within two German care institutions of the consortium, an elderly care institution and a hospital. Per each group of professionals one interview was held, which resulted in eight focus group interviews. After receiving instructions about the target group and information regarding the planned interviews, the care institutions recruited the participants for the focus groups and scheduled the inter-views. The interviewers were formed by a business psychologist and researcher of didactics, JN, and a researcher of nursing science, MM, from the UW/H to represent the didactic and thematic specialties of the interview, which were defined as interdependent. In addition, this was decided to ensure an economic data collection process during a global pandemic and with respect to possible cancellations. The interviews were further recorded with a tape recorder and were transcribed afterwards by an external agency with respect to data protection guidelines. The thematic analysis of the data was implemented using the Mayring method [42]. The didactic part of the emerged data was coded by the project worker and interviewer JN and the project manager JE within a coding circle. Subsequently, the gathered didactic and thematic themes were integrated in archetypical learner personae to reflect the vivid information of learning preferences and experiences of the health personnel and to demonstrate possible types of learners (here: users) to the technical consortium partners. In addition, instruction manuals based on didactic preferences and experiences were given to the technical consortium partners to initiate the generation process of the learning nuggets. The category system in the coding procedure was deducted from the described main research questions and was further extended with categories inductively. Furthermore, this system was reviewed by JN and MM and enlarged in an iterative process.

3. Results

The focus group study took place mainly in the first quartal of 2022 in the frequency of eight interviews with two up until six participants and two interviewers each. In detail, four interviews took place at a hospital in Essen, GER and four interviews proceeded at an elderly care institution in Oberhausen, GER. These facilities were chosen due to their role as partners in the MINDED.RUHR consortium. The interviews were conducted in the period from November 2021 to August 2022. The first focus group took place with six participants among nursing students of the hospital: four female and two male participants with an age span from 22 to 32 years with two years of professional practice experience each. Four participants constituted the second focus group among nurses of the nursing home. Among these, there were three female and one male nurse with a mean of 11 years of practice experience and 31-46 years of age. At this institution one focus group interview among three housekeeper staff members was held as well as two other groups consisting of three physiotherapists and three home care nurses. The first mentioned were all female participants with a mean of eight years practice experience and 32-58 years of age. There were two male and one female physiotherapists as participants with an average practice experience of five years, varying in age from 27-32 years. The home care nurses were 31-55 years old and had a mean of 15 years of practice experience with two female and one male participant. In February 2022, another three focus group interviews were held with the contribution of five stationary nurses, four patient serving professions and two physicians respectively. Four female and one male nurse with 19 years of practice experience on average and an age span from 24-56 contributed. The patient service professions varied in age from 23-62 years, an average practice experience of four years and four female to one male gender. Two 32-year-old male physicians with four years of practice experience participated lastly. The interviews differed in length from 39 minutes up until 86 minutes. A descriptive questionnaire given to the professions afterwards demonstrated the variance of the respondents in overall age (18-61 years), gender, professional qualification, employment status, form of employment, current profession as well as experience in professional practice. The corresponding table can be viewed in the attached table SM1 (supplementary material).

To analyze the qualitative data, a Mayring coding procedure was initiated [42]. To prepare the analysis process, an initial code system was prepared, based on the semi-structured interview guide. This code system consisted of 8 main categories as well as 12 subcategories. The main categories were descriptions of learning experiences, with subcategories in positive and negative experiences as well as learning associations. Reports of previous participation in seminars were accompanied by the subcodes online and attendance meetings. The category requests according to learning was accompanied by the subcodes Video, contact persons, exchange with others, text, audio, documents for reference and revisions. The main category Information procurement, description of learning flow as well as the cancellation of learning situations were fixed further. The category of implementation of new knowledge was accompanied by the description of obstacles in this process. Lastly, general conditions of learning were set as a main category for the interview analysis process.

In the main category learning experiences, previous learning events should be described by the participants. 108 nominations were made by the participants to do so. There were 30 positive nominations of learning experiences as well as 63 negative nominations. 15 learning associations were described. An example positive statement is:

“We had a topic called epigenetics (...). And I found that super exciting at the time and got two A4 sheets of paper from school and read them very quickly. Then I also read a lot of other things on the internet because I found it so exciting. (...) I think that was the first time I really realized: Wow, somehow (...) knowledge is unlimited, and you can learn so much and found that really fascinating” (B_7, l.35).

Reports of previous participation in seminars reflects concrete learning experiences of online and presence seminars with 48 nominations. 27 of these nominations were allocated to presence seminar experiences, three reports to online seminar experiences. The sub-category blended learning was added post hoc to summarize mixed learning experiences, mostly due to Covid-19 presence restrictions. The category requests include 154 statements that specify concrete methodological wishes for seminars. In addition to the previously set subcodes Video (10 nominations), contact persons (1), exchange with others (7), text (7), audio (10), documents for reference (11) and revisions (4), 14 subcodes were added. Example subcodes were wishes for practical exercises (18 nominations), a practical topic (17), a lively design of learning material (14) as well as interactive tasks (10). The participants also mentioned wishes according to the learning platform (7) and reservations about an online learning format (11). One example quote in this subcategory is

(...) If you have a lecture and you log in, you can still switch off your screen, you can also mute yourself, you can also mute the other side [laughing] (...) I think you’re more distracted there. Overall, you’re more distracted at home than when you’re taking part in a course” (A_1, l.39).

Within the category Information procurement, 94 statements of obtaining information for problem-solving in the working life were summarized. Statements were allocated to the subcategory’s attendance of training courses (5 nominations), case discussions (8), analogue research (6), digital research (28) and asking colleagues (45). One example statement in that often-mentioned last category is

Yes, the nice thing about it is that no one is left to their own devices, but that it’s done in a collective. In that way it’s always fun and it’s also solution-oriented (A_1, l.75)”.

The category implementation of new knowledge contains 70 statements that describe how participants implement new knowledge in their work life. Within 9 subcategories such as the exchange with colleagues (19 nominations), lack of time (8), finding allies (4), the usability of knowledge (4) and motivation (4), this implementation was characterized. The conflict with colleagues was often mentioned as a subcategory of transferring knowledge to work life (25 nominations). An example statement regarding the conflict of colleagues is

“(...) You feel really pushed into the typical role of the trainee and you also try to deal openly with the fact that everyone has been trained at a different level of knowledge and that something new is always being added, but if there is no openness at all (...) then it is not possible to work in a team to ensure that you always work based on latest scientific research or, yes, keep up with the state-of-the-art in nursing science” (B_1, l.47).

Within the category of general conditions of learning 5 quotes were concluded. These were subsumed within the subcategory’s quietness (3 nominations) and time pressure (2). One sample quote regarding conditions of learning in work life is “(…) and also that it takes a lot more time when you change something, for example. Or simply because you can’t do it quite as quickly because you must be more focused” (B_3, l.70). None of the statements were made within the former set categories learning flow or cancellation of learning situations. The categories concerning the daily work life and description of preferred learning methods were added post hoc and subsume 59 and 108 nominations. For the learning methods, 12 subcategories were formed. Learning by doing (12 nominations), summaries (19), reading (16), practical visualization (10) and textualization of learning material (8) represent the most mentioned learning methods. An overview of the subsumed categories can be reviewed in Table 1.

Table 1.

- Demographic data of the participants of 8 focus groups

Table 1.

- Demographic data of the participants of 8 focus groups

| Categories |

Mentions |

Anchor quotes |

| Learning experiences |

108 |

“Learning by doing and looking at colleagues, how do they do it?” (A_1, l.60) |

| Learning associations |

15 |

|

| Negative |

63 |

“I never enjoyed learning (laughing). So, for me it was more the utility of learning (...) but having fun? Never!” (B_7, l. 37) |

| Positive |

30 |

“We had a topic called epigenetics (...). And I found that super exciting at the time and got two A4 sheets of paper from school and read them very quickly. Then I also read a lot of other things on the internet because I found it so exciting. (...) I think that was the first time I really realised: Wow, somehow (...) knowledge is unlimited, and you can learn so much and I found that really fascinating” (B_7, l.35) |

| Participation in seminars |

48 |

|

| Blended Learning |

5 |

“(…) At the beginning of last year, I completed my further training as a care supervisor. (…) Yes, it was just mixed. A lot online due to COVID. And then there were PowerPoint presentations that were simply played back to us and maybe a few sentences were said” (A_4, l.22). |

| Presence seminar |

27 |

“On the one hand, to see how it is implemented in practice and to really talk to the colleagues locally who presented it afterwards, they also did PowerPoint presentations (...) but to really experience how it is lived in everyday life, I think that was the biggest learning effect” (B_2, l.24) |

| Online seminar |

3 |

“It’s a lot of stuff that’s discussed at the beginning, where you actually have to sit and listen for hours on end and(...) often the training courses don’t take place just around the corner, you have to travel a long way to get there. (...) It would be super cool to really take the time from home to go through everything in detail (...)” (A_3, l.16). |

| Requests |

154 |

|

| Practical exercises |

18 |

“I think that’s actually the best kind of training or lecture, when it’s very practice-oriented and you don’t just sit there and get told something, but rather (...) are accompanied in such cases and are really shown: Hey, this is how you have to do it” (A_3, l.26). |

| Practical topic |

17 |

“And if they [teachers] (...) tell us stories about the patient (...) and an example, then I can listen especially well, then there’s a real suspense” (B_2, l.31). |

| Lively learning material |

14 |

“But it also must be interesting, if someone just reads out something (...), then I don’t listen at all, then I switch off very quickly, but if two people talk with interest (...) and also give examples from practice (...) then a lot remains in my head” (B_2, l.27). |

| Documents for reference |

11 |

“[would use a learning portal] to look at it again later. So, I think I would use that as a learning method” (B_1, l.26) |

| Reservations against online format |

11 |

“(...) If you have a lecture and you log in, you can still switch off your screen, you can also mute yourself, you can also mute the other side [laughing] (...) I think you’re more distracted there. Overall, you’re more distracted at home than when you’re taking part in a course” (A_1, l.39). |

| Interactive tasks |

10 |

“(...) actively think for yourself and perhaps also find examples from everyday practice” (B_2, l.32). |

| Audio |

10 |

“I also like to listen to podcasts from time to time, so I can take something away with me” (A_4, l.28). |

| Video |

10 |

“With examples from life, I also enjoy a short film (..) as it’s more likely to stick than someone standing there telling you something or reading something (...)” (A_2, l.45). |

| Information procurement |

94 |

|

| Asking colleagues |

45 |

“Yes, the nice thing about it is that no one is left to their own devices, but that it’s done in a collective. In that way it’s always fun and it’s also solution-oriented” (A_1, l.75). |

| Digital research |

28 |

“Yes, we have (digital) biographies. And if we want to have specific things - we’re working to digitize the other generations as well. And you can look up a lot of things on computers. If you don’t know what someone likes to eat (...) we have these biographies (..) Or you can also read up on whether someone has behavioural problems or not, i.e. if you can’t find anyone at all because the nursing staff are under stress or the attendance staff or the social services. Anyone can go in there, everyone has their own code, and you can read a lot of things there” (A_2, l.75). |

| Case discussion |

8 |

“That’s always really good because lots of people then have lots of information and we usually come up with a solution” (A_1, l.71). |

| Analogue research |

6 |

“What make sense is to browse through the script again when you know: Okay, you somehow had a technique for that, you just have to repeat it again” (A_3, l.42). |

| Attendance of training course |

5 |

“What I needed (...) were the training courses that take place here regularly, such as basic live support or first aid” (B_3, l.8). |

| Implementation of new knowledge |

70 |

|

| Conflict with colleagues |

25 |

“(...) You feel really pushed into the typical role of the trainee and you also try to deal openly with the fact that everyone has been trained at a different level of knowledge and that something new is always being added, but if there is no openness at all (...) then it is not possible to work in a team to ensure that you always work based on latest scientific research or, yes, keep up with the state-of-the-art in nursing science” (B_1, l.47). |

| Exchange with colleagues |

13 |

“Then you can talk about it: One person does it like this, the other like that, everyone has their preferences (...) you can try it with the other technique that the other person has used” (A_3, l.38). |

| Lack of time (for implementation) |

8 |

“And also that it takes a lot more time when you change something, for example. Or simply because you can’t do it quite as quickly because you have to be more focused” (B_3, l.70). |

| Finding allies (for implementation) |

4 |

“If you are on the ward and (...) want to present something new then it is very good that the ward manager supports you, that you are offered a setting where you can incorporate new knowledge into the team, that you say at the team meeting, for example, hey, can I have another five minutes and bring in a few more points from my further training XY, that is definitely good” (B_2, l.89). |

| Motivation |

4 |

“When you come back from a good training course, I (...) always have the feeling that I have to go straight into the company and try everything out straight away” (A_2, l.111). |

| General conditions of learning |

5 |

|

| Quietness |

3 |

“[learning happens] when I have a lot of peace and quiet, preferably at home” (A_1, l.16). |

| Time pressure |

2 |

“So, time is a factor for me. If I have to study because I have an exam or whatever coming up, I do it at the very last minute when I really have to” (A_1, l.38). |

| Learning methods |

108 |

|

| Learning by doing |

22 |

“But there is no magic formula. For me, a magic formula simply means listening, looking, and trying things out. I can just try things out for myself” (A_2, l.220). |

| Summaries |

19 |

„And I usually proceed by reading everything, crossing out the most important parts and signing them with a highlighter. In the final phase, I always write index cards to summarize everything” (A_4, l.14). |

| Reading |

16 |

“And then, just read it out loud again and again, that’s my strategy, that’s what sticks with me the most” (A_4, l.14). |

| Practical visualisation |

13 |

“When I read something (...) I can’t internalise it, I immediately forget it again. When I’m shown it, I can somehow remember it better” (A_1, l.41). |

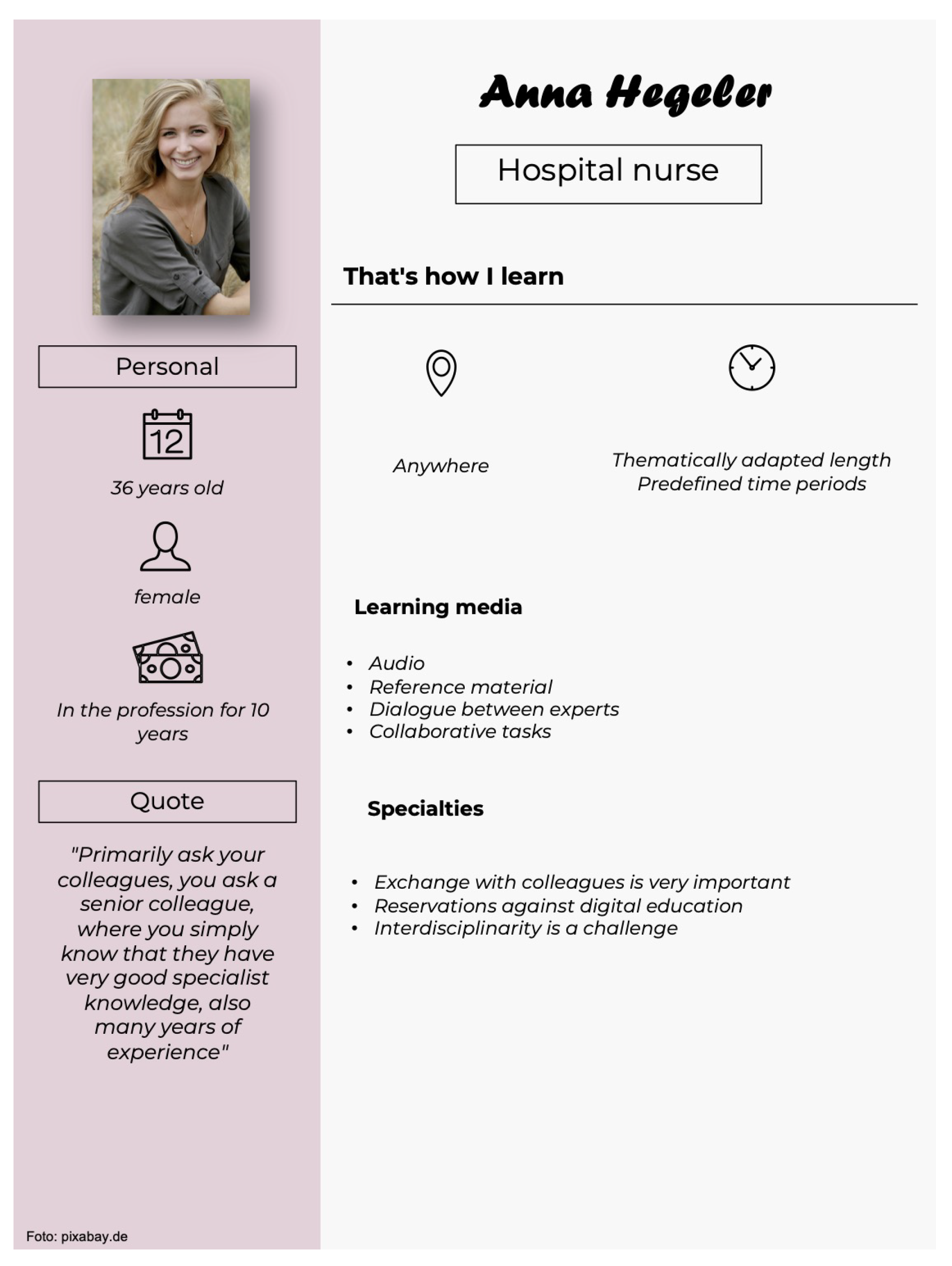

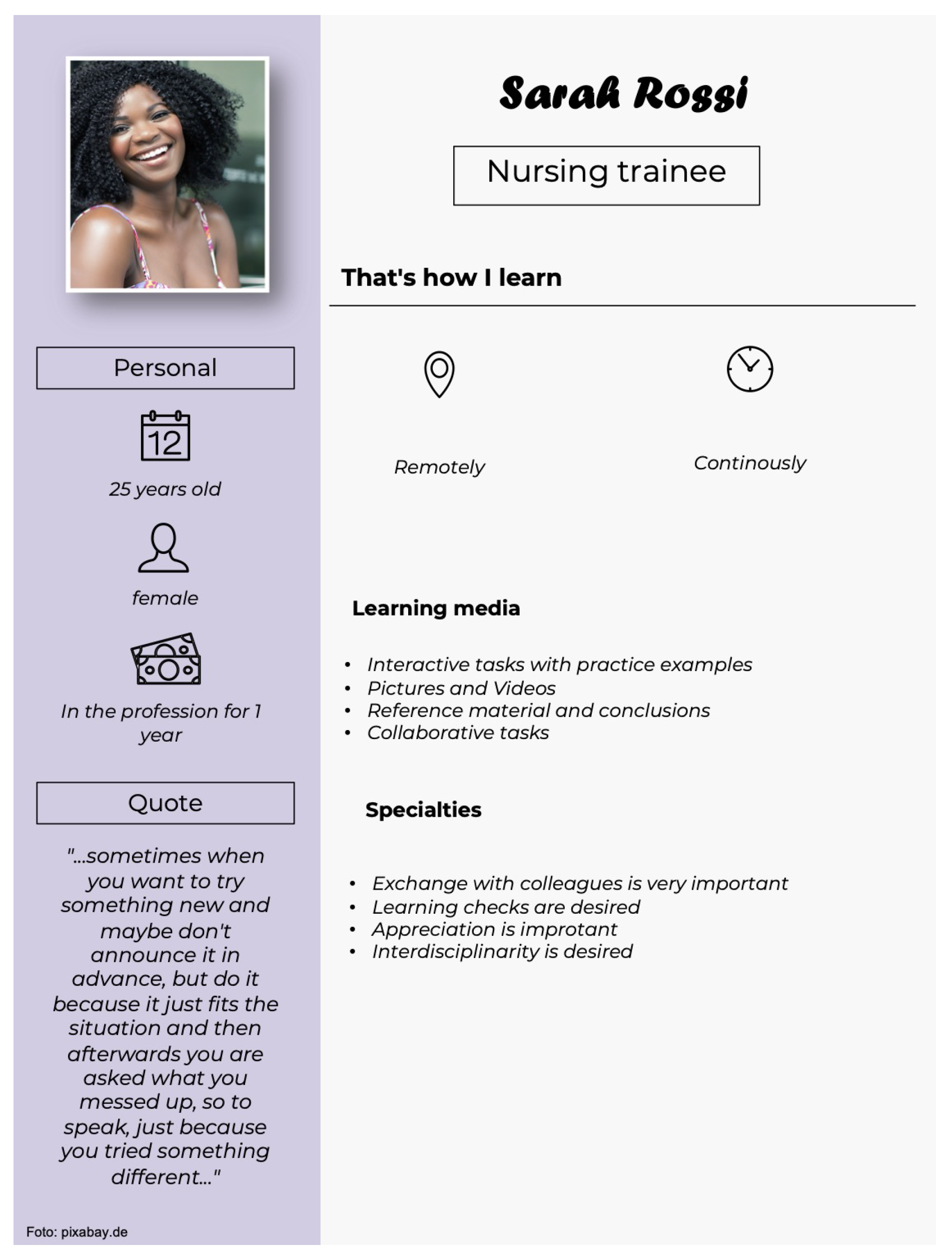

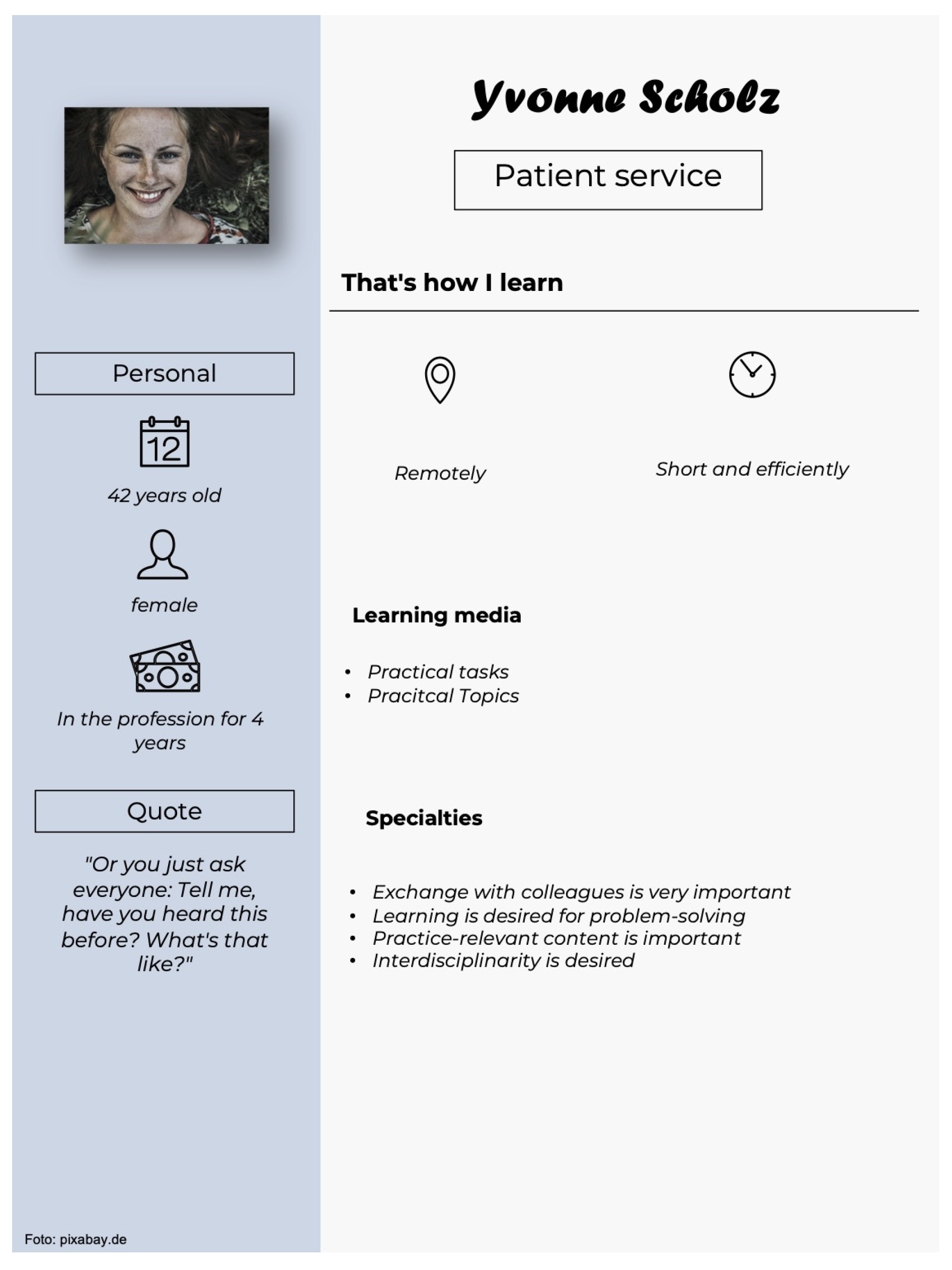

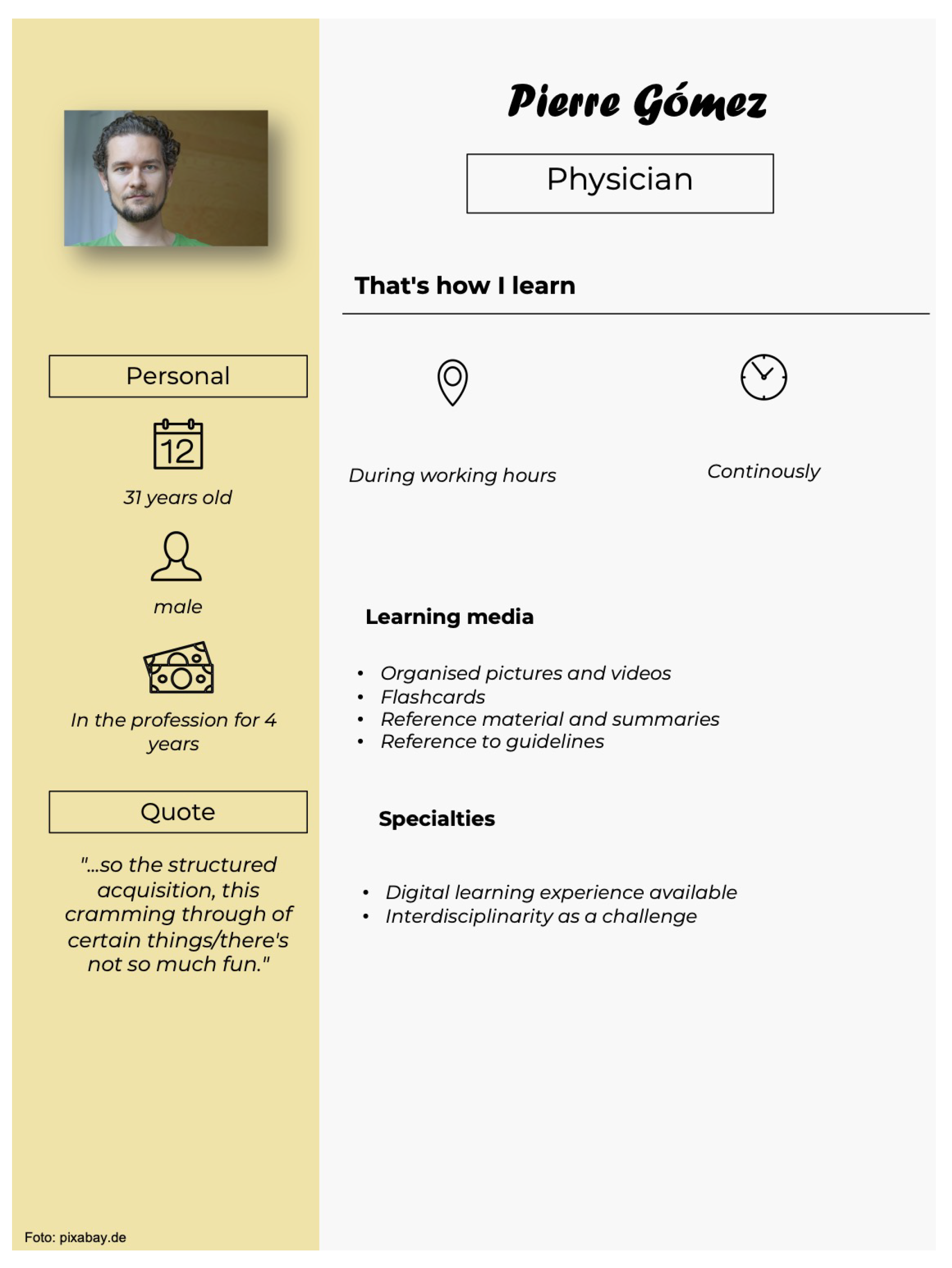

As a qualitative clustering method, the identified learning preferences and -needs of the focus group interviews were summarized in 8 personae of different health professions, illustrating the variety of individual learning experiences and didactic requirements of learners for a possible design process. Each persona reflects an exemplary type of learner in the field of healthcare, representing the usual framework of learning, learning media, didactic specialties as well as personal information regarding age, gender, and practical experience.

The first persona reflects a 36-year-old nurse with a hospital named Anna H. with 10 years practical experience, who is used to learning remotely in predetermined time slots who states previous negative learning experiences. Preferred learning media are audio, reference material, speaking with experts as well as collaborative tasks. Anna has didactic specialties in a preferred exchange with colleagues as well as reservations about digital education programmes. Furthermore, interdisciplinarity regarding health education is challenging for Anna.

Another persona is a 25-year-old-nursing trainee named Sarah R. with 1-year practical experience. She is used to learning continuously and remotely and has negative previous learning experiences as well. Preferred learning material are interactive tasks with practice examples, images and videos, reference material and summaries and further collaborative tasks. Didactic specialties for Sarah are a focus on the exchange with colleagues, desired reviews of learning outcomes and the appreciation of these outcomes. Interdisciplinarity is a desired specialty for this persona as well.

Yvonne S., a 42-year-old patient service health professional with 4 years in practice, tends to learn remotely in a short and efficient way and further has previous negative learning experiences. She likes to learn by doing practical tasks and practice-oriented topics. Regarding didactical specialties, the exchange with colleagues has a high priority for her, too. Learning is a desired way to solve problems and practical and professionally relevant content is important as well as interdisciplinarity.

Pierre G. is a 31-year-old physician with 4 years practical experience who prefers to learn during working times. He learns continuously and reports negative previous working experiences. Clear images and videos, flashcards, reference material and summaries as well as references to medical guidelines are preferred materials. Existing digital learning experience and interdisciplinarity as a challenge can be noted as didactic specialties.

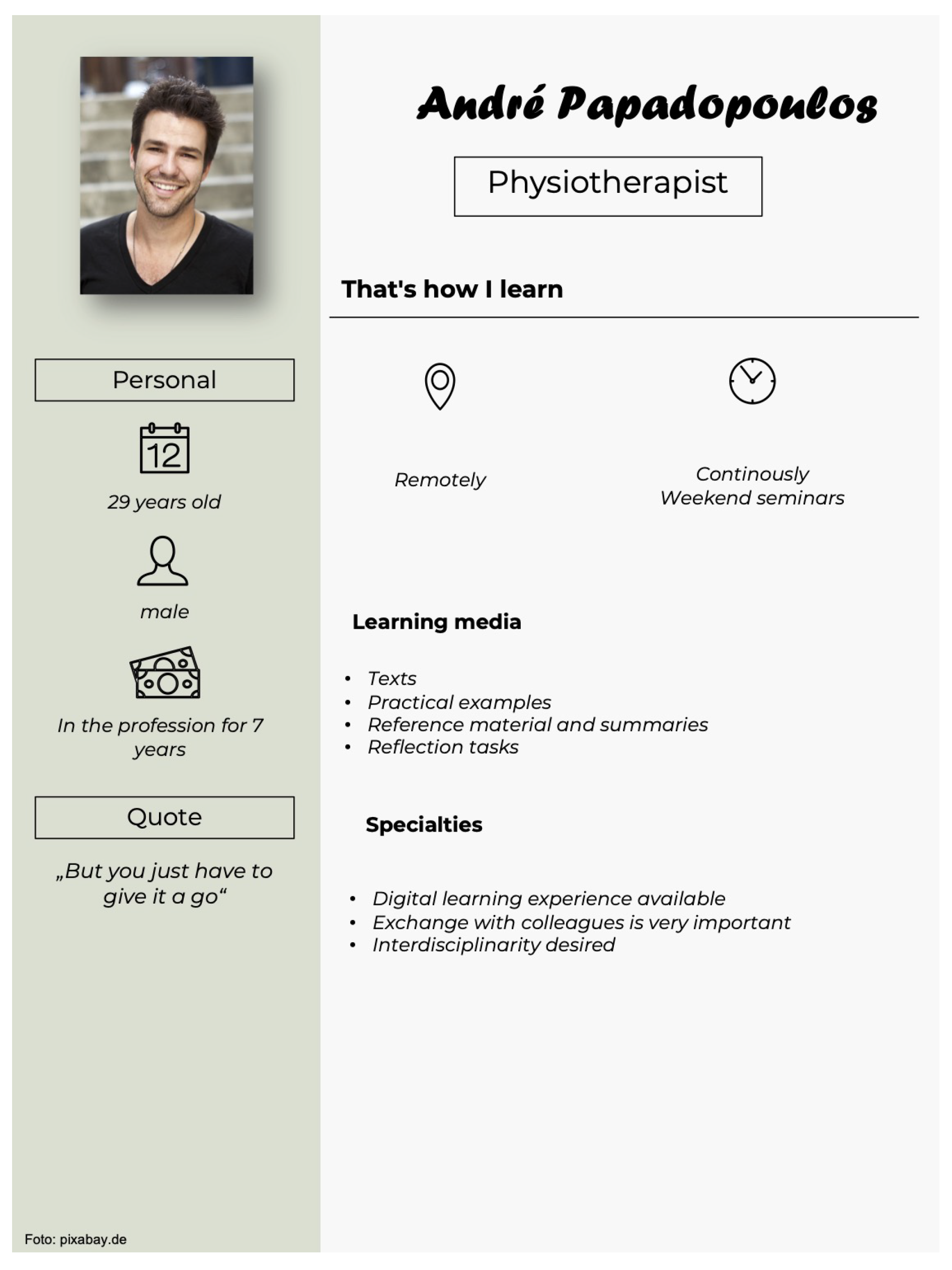

Another persona is 29-year-old physiotherapist André P with 7 years in practice, who prefers to learn remotely, continuously and in weekend seminars and reports pre-vious negative experiences. Preferred learning materials are texts, practice examples, reference material and summaries as well as questions for reflexion. As didactic spe-cialties, existing digital learning experiences, a priority for the exchange with colleagues as well as desired interdisciplinarity is desired.

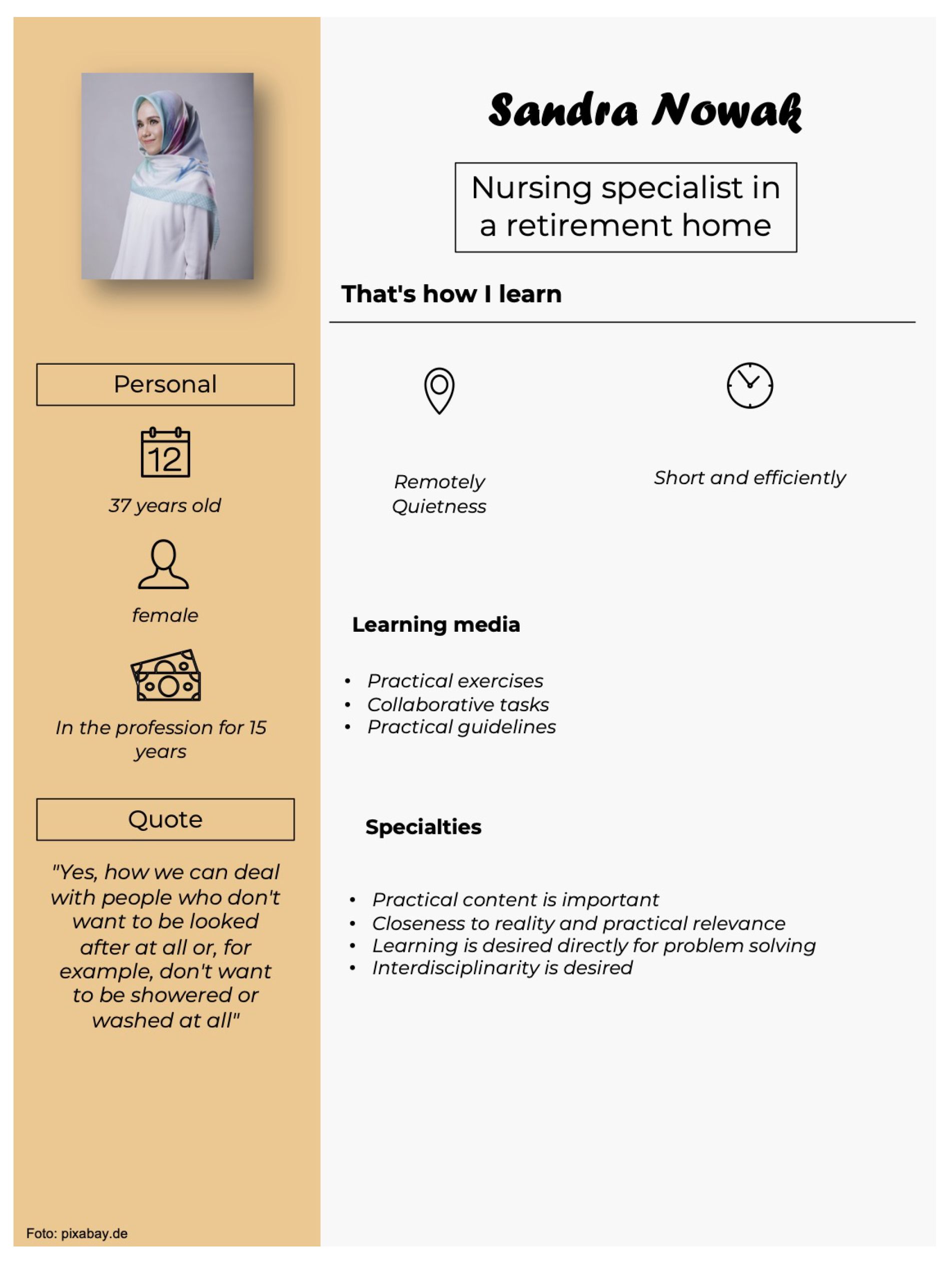

Sandra N., a 37-year-old nurse in a nursing home is another persona with extended practical experience (15 years) , who tends to learn remotely. She prefers short and effi-cient learning sessions and reports neutral learning experiences. The learning process is preferably supported by practical and collaborative tasks and operation guidelines. Sandra reports practical, professionally relevant, and realistic content as a didactic spe-cialty. She also desires learning to be a matter of problem-solving and implementing interdisciplinarity.

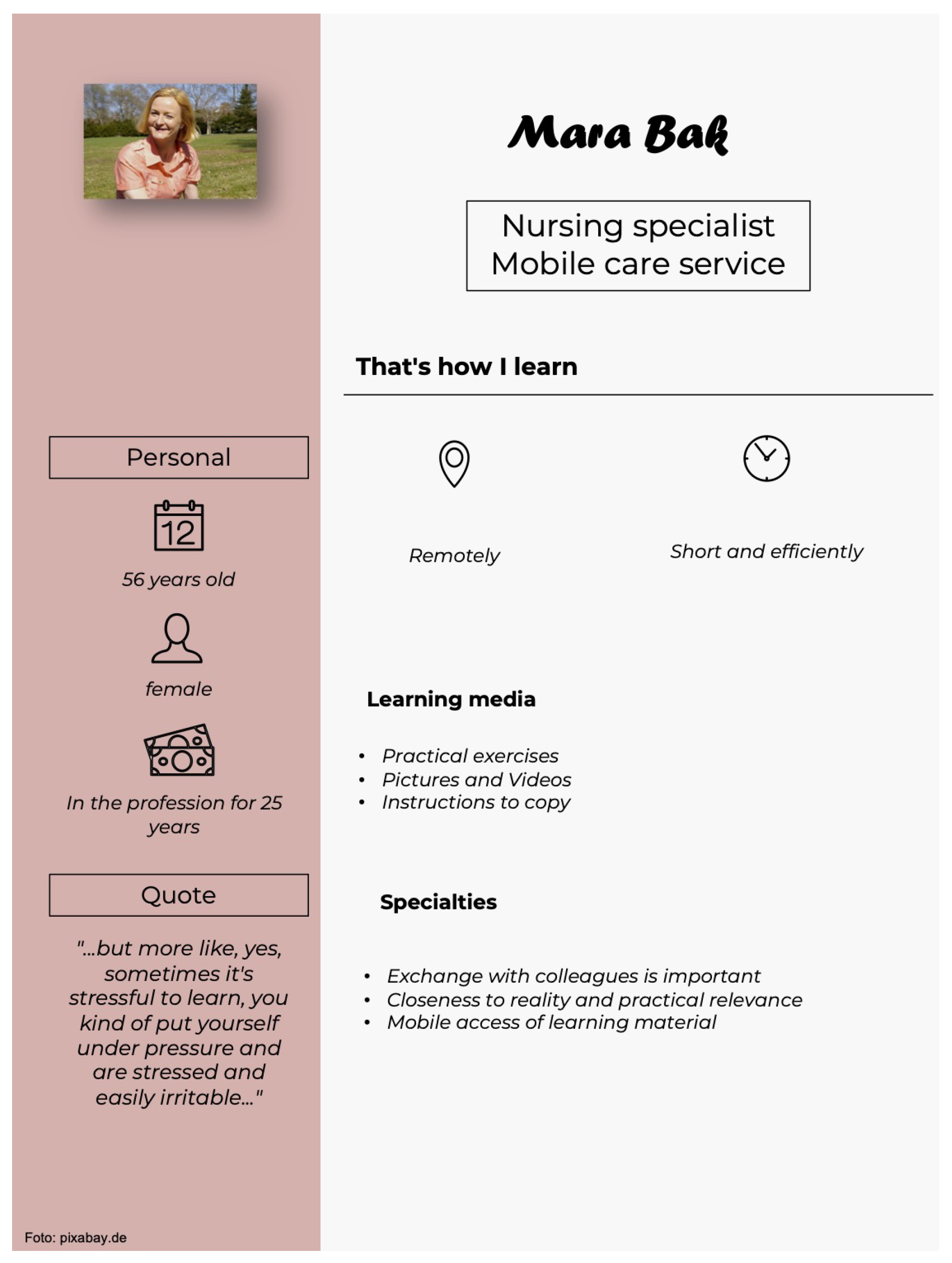

Another persona is Mara B., a 56-year-old nurse with 25 years practical experience in a mobile nursing service. She learns remotely, shortly, and efficiently and reports positive previous learning experiences. The learning process is optimally presented, when it is by practical tasks, images, and videos as well as instructions to copy. Specialties are the priority of the exchange with colleagues, a realistic and practical relevance as well as the mobile availability of learning content.

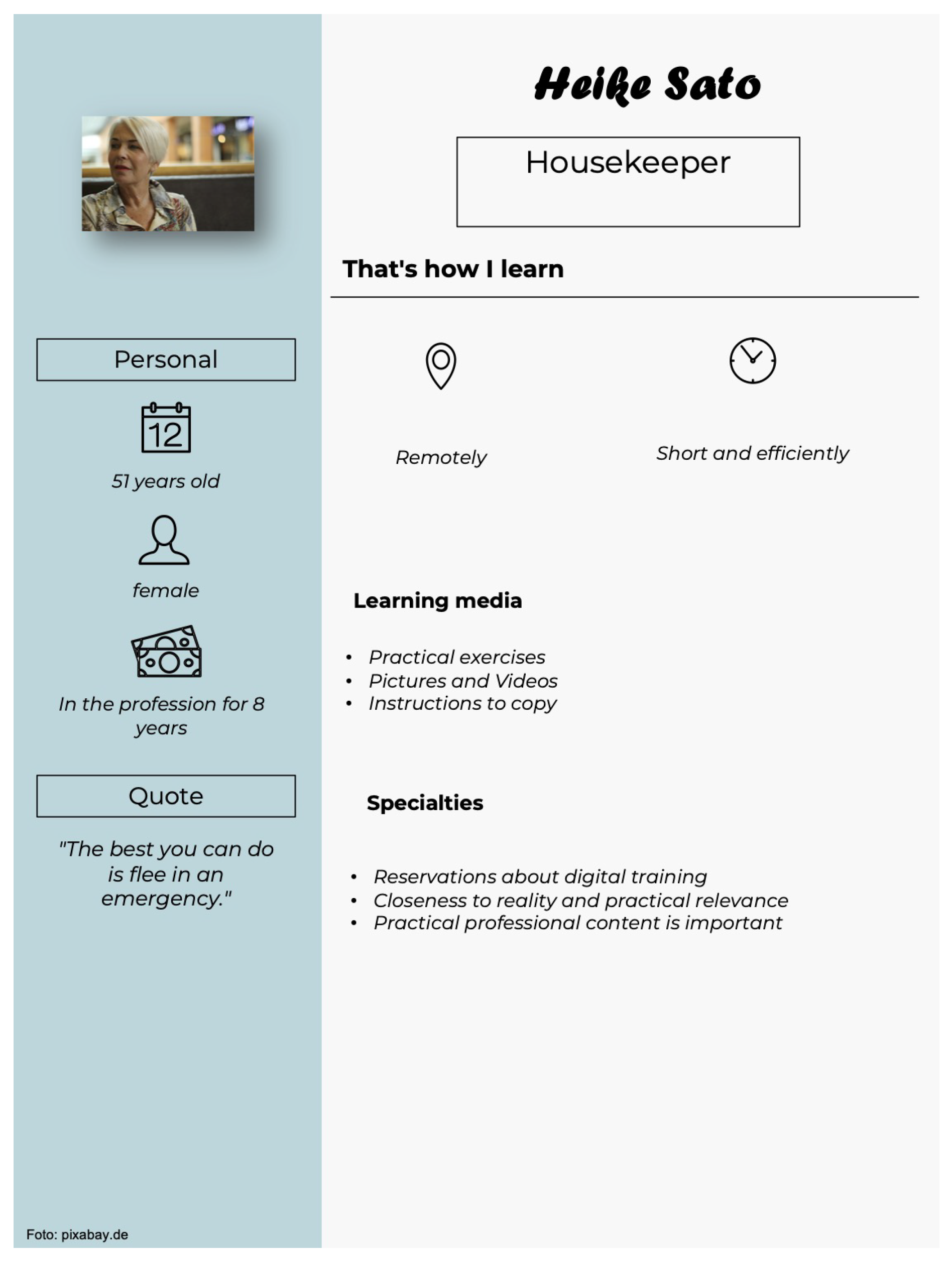

The last persona is Heike S., a 51-year-old facility manager in a nursing home with 8 years in practice. She also tends to learn remotely, shortly, and efficiently and reports both positive and negative learning experiences. She likes interactive tasks, images, and videos as well as instructions to copy as learning material. For didactic specialties, there are reservations about digital educational programmes and a preference for realistic, practical, and professional relevance of learning content. Thematic specialties according to the collaborative work with care sciences as well as quotes of the focus group interviews supplement each persona report as well (see attached SM2: Didactic personae).

4. Discussion

The eight participative focus group interviews contribute to a detailed under-standing of the previous learning experiences, preferences as well as difficulties in reception and implementation of further education in German healthcare everyday work. These distinctive features of learning behaviour among health professions in comparison to didactic literature are further examined to develop an understanding of various healthcare learner features as a foundation for needs-based learning material and suggestions for structural promotion of efficient learning experiences in healthcare further education.

Regarding previous learning experiences the negative connotation of learning among this sample of health professions is noticeable (60 mentions). Negative associations concern the time intensity besides challenging work life, redundancies in further education material, unstructured further education material, non-practical or non-activating education formats, stress due to masses of learning content as well as overload regarding priorisation for competence validation. However, for an enjoyable, successful, and sustainable learning experience, a positive attitude towards learning objects or learning in general may be crucial, suggesting a general need to support learning motivation and the restructuring of further education among health professions not only in Germany [43,44]. On the other hand, a positive attitude towards learning is reflected in 30 mentions among health professions. The character of these learning attitudes, reflecting personal enrichment and flow through new knowledge, cooperation with colleagues, practical or otherwise exciting topics as well as the successful application of knowledge for medical routines may be hints for enhancing the intrinsic learning motivation of health professions as a key quality to promote self-regulated learning and continued autonomous further education [6,15,19,20].

Concerning previous seminar and further education experiences, it is prominent that the interviewed health professions report few experiences with blended learning formats (5 mentions) or e-learning formats (3 mentions) in comparison to presence formats (27 mentions). More than a few participants even report reservations about the online format (11 mentions), addressing problems like concentration issues in longer digital seminars, insufficient memory performance due to situationally remote content, lacking commitment due to reduced social control and possible interfering disturbances in the environment of the e-learner. This attitude and lack of remote learning experience might impede efficient further education and knowledge implementation in the light of rising challenges for healthcare professions, e.g. information overload in clinical environments, lack of interprofessional exchange and time and personnel resource scarcity [6,45]. Digital education formats do have advantages to address these challenges, making further education more accessible, flexible and time and cost-efficient in healthcare [6] he general procurement of information on the contrary is preferably digital yet (28 mentions) in comparison to analogue procurement of information (6 mentions). This is comparable to the learning experiences from other healthcare professions that have already been examined in other studies [46,47]. In order to promote digital education formats by raising individual motivation for accustomed learning in and around the workplace, it seems reasonable to integrate the preferred quality of asking colleagues for information procurement (45 mentions) into the learning material to meet the learning preferences of healthcare professions, to amplify identification and the actual continued usage of the learning material as well as to facilitate the shift from analogue learning habits to digital ones for all types of health professions [17,48,49].

Another prominent specialty shown by the focus interviews in this study is the quantity of requests regarding the design, structuring, and didactical features of (154 mentions). It can be demonstrated that the target group of health professions does have a lively interest in the co-design of their learning process, indicating the acceptability of a participative procedure of further education development. This may constitute a good foundation for self-directed learning among health professions in general and an acceptability and usability of digital education material developed for these professions, supported by constructivist learning theories [15,50].Along the requests a variety of preferred multimedia learning objects are evident, regarding the transparent structure of a learning platform (7 mentions), practical tasks to internalize medical processes and empathize with residents and patients as well as interactive tasks (14 mentions; 10 mentions). Moreover, the request of documents (11 mentions) for reference, audio formats (10 mentions) and learning performance checks (4 mentions) are mentioned. These various didactic needs may reflect the initial suggestion of a need for individualized learning recommendations to keep health professions motivated with demand-oriented, multimedia learning material in their self-directed learning experience [7,21,25]. Within the domain “information procurement” it is noteworthy among health professions participating, that this process is preferably digital. Health professions do inform themselves regarding uncertain workflows or situations via clinical websites or other evidence-based digital tools and therefore in an efficient way (28 mentions) [13,51,52]. This appears beneficial concerning the immediacy of this way of information procurement and possible rapid problem solving in the situation due to access to updated, evidence-based knowledge [6]. However, most of the participants report asking colleagues to procure new information in and around daily work situations (45 mentions). This has been presented as valuable for both the health profession itself and patients’ care, not only in terms of content-specific knowledge. In fact, improved overall teamwork skills, a patient-centred focus, specific communication skills as well as shared global values are examined along with the exchange with colleagues in healthcare, especially among interprofessional ones [53]. Conveying the social aspect of information procurement when designing learning material might therefore additionally support individual competencies of health professions beneficial for patients care quality [54].

Although this appears beneficial due to the reciprocal social support and exchange of experiences, possible interpersonal conflicts might cause a gap between the procurement and the actual implementation of gathered health-related knowledge in the daily work lives of health professions participating (25 mentions). Regarding the knowledge implementation, more than a few participants report experiencing conflicts with colleagues when trying to implement new workflows or suggest updated health-related information after attending seminars or after the acquisition of new evidence-based knowledge (25 mentions). This is mainly reported due to hierarchical structures and prior work experience, established working standards, which are refused to breach, or individual accustomed working preferences, which may be hard to address for optimization. In other health-related studies and institutions, these conflicts are reported linked to updated knowledge, hierarchical structures, a challenging work environment and personal experiences of personnel [55,56]. The nature of this conflictual process is examined in fundamental learning and organizational-psychological theories as well, referring to the importance of the co-creation of cultural knowledge in health organizations [6,50]. Cognitivist knowledge theories try to represent and model processes into schematic solutions, trying to represent generic information structures and workflows based on information processing and logical reasoning [50,57]. Constructivist theories are referring to a non-universal understanding of knowledge, which is individually or systemically built and influenced by the experiences, the values and the current perception of the persons perceiving it. The information then is “true” when it is confirmed through its applicability and functionality. In this context, constructivists refer to explicit (or factual) and tacit knowledge; latter requires practice and is rather acted out than actively held conscious [50,58]. Transferring explicit knowledge into actable, tacit knowledge e.g. workflows require time and cognitive capability resources, which are utilized to capacity in health-related working fields [59]. It can be challenging for healthcare professions to integrate derived knowledge from seminars etc. into the established of cumulated organizational experiences and relations, organizational time or personal resources, history of the resident or patient as well as prior interpersonal collaboration experiences [6,50,60]. This may ex-plain the conflicts or non-compliance of colleagues reported by the surveyed professions, referring to mentions of time famine (8 mentions) and a limited applicability (4 mentions) of knowledge given the circumstances in the institution. Reported strategies to cope with these barriers are finding allies to implement new knowledge (4 mentions) as well as the open-minded exchange with colleagues (13 mentions). Within constructivist learning theories, this collaborative exchange has been described in terms of constructing a new, common knowledge culture, fusioning existing values, prior experiences to cultivate process-enriching knowledge and reflection structures [50,61]. However, an overall negative assessment of knowledge implementation is prominent among the surveyed health professions (40 mentions), putting the practical use of individual learning for some of these health professions for their working life and patients in doubt. Structural support needs e.g by the care or clinical institution or legislators in medical and care training for the implementation of new knowledge and optimizing workflows are revealed to facilitate interprofessional and overall collaboration among health colleagues as well as the cultivation of a common ground of updated knowledge and problem-solving within a hierarchical and resource-consuming working field [50,60,62].

Speaking of institutional circumstances of learning, it is shown that requested, but not existing peace and quiet as well as time pressure at the workplace are mentioned, demonstrating a possible non-optimal learning environment for at least a few health professions participating. Non-optimal further education conditions are reported by healthcare workers in other samples as well [59,62,63]. An optimal health workplace could provide marked out times and places for learning and individual process reflection, activating workspace leaders with challenging questions as well as the empowerment of personnel in terms of collaboration and participation within working structures [62,64,65]. Besides these structural improvements, implications for the design of learning material result in short learning units, a decentralized presentation and guided, structured learning material to guarantee the fit of the learning formats in challenging daily work routines [6]. Various needs of mostly practice-oriented formats (12 subcategories) are evident in this study, indicating a necessity for a needs-sensitive learning platform to include the variety of format requests in an economical way. Mostly it is to recommend developing practical tasks and storytelling (19 mentions) as well as summarizing formats (22 mentions) to meet these needs [64].

There might be limitations to the procedure in this study that might restrict the results and their scientific applicability. Although the focus group method is a widely established method in health-related research and can stimulate described common knowledge in constructivist matter, it might be possible that participants influence each other’s opinion or are influenced by the guidance of the moderator itself [38,65,66]. Group dynamics like relational experiences, invisible social hierarchies or a minority status in an opinion may hereinafter impede sharing the genuine contribution to the group due to social desirability matters. The moderator itself can bias the natural dynamic of the group and lead the discussion explicitly or implicitly into a desired direction [38,66]. By adhering to the semi-structured interview guide, this previously known risk appears minimized. The following used persona method is a widely used standard method to communicate needs in user-centered design. However, personae cannot be verified or falsified, indicating a limited validity [67]. Importances of certain personae for a sample cannot be weighted and it cannot be illustrated, if there are users “between” the personae, indicating a possible greater variability then among given archetypal types. The dimensionality of a persona is another weakness, indicating a lower probability of this actual user type among all possible users with rising features describing it and required multivariate correlations to assess the accuracy of this various features, which are not made due to a large statistical outlay. In practical matters, there are limitations linked to the interpreter’s associations of the personae, possibly biased by personal experience and context, and resulting in a subjective conclusion [67].

However, the planned construction of a variety-sensitive recommender system based on stepwise integrated user interaction data might help users build learning paths according to their individual preferences and learning experiences and therefore provide additional customization and variability to the underlying archetypical personae characteristics in the further course of the project.

5. Conclusions

The DEDHI-Framework as well as health-related, participative design studies have already initiated the applicability of the needs analysis within focus group interviews as well as the persona method to represent user- and learning specificities and to design digital education material [68,70,71,72]. It can be illustrated that healthcare professions of the surveyed institutions prefer to learn with practical or interactive tasks in various multimedia formats. Interprofessional and collegial exchange is the main source for applicable information and reservations against digital education formats are visible. The demonstrated needs for user-centred and decentralized learning are reflected in other samples of health institutions and health professions as well [56,62]. A representativity of the presented user data and an added value to the understanding of learning needs of health professions in German healthcare institutions is therefore given. It is further suggested that individual further education in healthcare needs to be systematically supported, preferably by colleagues, instructors and on the organizational level and barriers of implementation need to be identified to cultivate a positive explicit and tacit learning environment, in which all interprofessional elements of a health institution can provide optimal healthcare work collaboratively and up to the latest state of science [6,62]. In this study, the closeness to application is given by the participating consortia partners B and GH so that a room is provided for questioning existing further education structures. For implementation of this findings, the resulting archetypical personae and gathered learning experiences as well as needs from the surveyed health professions form the basis for the development of prototypical learning units for the subproject of the MINDED-Ruhr consortia project MR_UWH “Development and preparation of individual learning content using the example of challenging behavior of people living with dementia”, ensuring a user-centred design of specific learning units as well as adaptive learning paths supported by AI for the facilitation of individual further education in German healthcare.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the manuscript, reviewed, and approved the final version of the paper. All have agreed both to be personally accountable for their own contributions, and to ensure that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work, even ones in which the author was not personally involved, are appropriately investigated, resolved, and the resolution documented in the literature. The contributions are specified as it follows: Conceptualization, J.N and M.M.; Methodology, J.N and M.M.; Validation, M.S, J.N, M.M.; Formal Analysis, J.N, J.E, M.M and M.S. .; Investigation, J.N. and M.M. ; Resources, J.N.; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, M.S. and J.N.; Writing – Review & Editing, M.S, J.N, M.M.; Visualization, M.S and J.N.; Supervision, J.E. and M.H.; Project Administration, J.E. and M.H.; Funding Acquisition, J.E. and M.H.” All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study is financially funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) and supported by the Federal Institute for Vocational Training (BIBB), grant number 21INVI0301.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical approval to conduct the study was sought and granted by the Ethics Committee of UW/H (Nr. 210/2021). Written informed consent to participate and be audio-recorded are obtained from all participants. Data management and storage will be subject to the European General Data Protection Regulation [43]. Participants are assured that their personal data, data supplied in questionnaires, and audio recordings will remain anonymous during analysis and reporting. The participants are asked to respect the confidentiality of their observations about colleagues’ participation in the focus group interviews.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The materials described in this paper pertain to the focus group interview report only, and there are no raw data reported. The datasets are collected and analyzed and can be made available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to mention all consortia partners: MedEcon.RUHR (consortium leadership), DATATREE AG, Fraunhofer Institut für Software und Systemtechnik (ISST), TUTOOLIO GmbH, and Duisburg-Essen University. A special thanks goes to the consortial participants of this study of the Alfried Krupp Krankenhaus (B) as well as the Gute Hoffnung.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

6. (SM1)

The following table represents the participant demographic data of the surveyed health professions.

Table 2.

Demographic data of the participants of 8 focus groups

Table 2.

Demographic data of the participants of 8 focus groups

| Group |

Total (n) |

| Age |

|

|

| 18-24 |

6 |

|

| 25-34 |

14 |

|

| 35-44 |

3 |

|

| 45-54 |

3 |

|

| 55-64 |

7 |

|

| Gender |

|

|

| female |

24 |

|

| male |

10 |

|

| diverse |

- |

|

| Professional qualification |

|

|

| University degree |

8 |

|

| Professional-operational degree |

11 |

|

| Professional-educational degree |

9 |

|

| No degree |

5 |

|

| Other degree |

1 |

|

| Employment status |

|

|

| In training |

9 |

|

| Employed |

25 |

|

| Self-employed |

- |

|

| Civil servant |

- |

|

| Other |

- |

|

| Form of employment |

|

|

| Full-time |

22 |

|

| Part-time |

10 |

|

| Mini job |

2 |

|

| Parental leave or other leave of absence |

- |

|

| Current profession |

|

|

| Physician |

2 |

|

| Student physician assistant |

2 |

|

| Physiotherapist |

3 |

|

| Nurse |

11 |

|

| Nursing assistant |

1 |

|

| Patient serving personnel |

2 |

|

| Additional caregiver |

3 |

|

| Facility manager |

3 |

|

| In training |

7 |

|

| Experience in professional practice (by years) |

|

|

| 1-4 |

18 |

|

| 5-10 |

11 |

|

| 11-15 |

- |

|

| 16-20 |

1 |

|

| 20+ |

4 |

|

| Total (N) |

34 |

|

Appendix A. (SM2)

The following figures display the didactic personae, derived from the needs and preferences of the surveyed health professions.

Figure A1.

Persona 1 - Anna H.

Figure A1.

Persona 1 - Anna H.

Figure A2.

Persona 2 - Sarah R.

Figure A2.

Persona 2 - Sarah R.

Figure A3.

Persona 3 - Yvonne S.

Figure A3.

Persona 3 - Yvonne S.

Figure A4.

Persona 4 - Pierre G.

Figure A4.

Persona 4 - Pierre G.

Figure A5.

Persona 5 - André P.

Figure A5.

Persona 5 - André P.

Figure A6.

Persona 6 - Sandra N.

Figure A6.

Persona 6 - Sandra N.

Figure A7.

Persona 7 - Mara B.

Figure A7.

Persona 7 - Mara B.

Figure A8.

Persona 8 - Heike S.

Figure A8.

Persona 8 - Heike S.

References

- Junne, F.; Michaelis, M.; Rothermund, E.; Stuber, F.; Gündel, H.; Zipfel, S.; Rieger, M.A. The Role of Work-Related Factors in the Development of Psychological Distress and Associated Mental Disorders: Differential Views of Human Resource Managers, Occupational Physicians, Primary Care Physicians, and Psychotherapists in Germany. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, A. Establishing the boundaries between work and home. Journal of Kidney Care 2018, 3, 262–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radeva, S. CHALLENGES BEFORE THE MANAGEMENT OF HUMAN RESOURCES IN THE HEALTH ORGANIZATION. Е 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, M.; Good, V. S.; Gozal, D.; Kleinpell, R.; Sessler, C. N. A Critical Care Societies Collaborative Statement: Burnout Syndrome in Critical Care Health-care Professionals. A Call for Action. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine 2016, 194, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantel, J. Differentialdiagnose und Pathophysiologie der Demenz. In Demenz—Prävention und Therapie. Ein Handbuch der Komplementärmedizinischen und Nichtmedikamentösen Verfahren; Walach, H., Loef, M., Eds.; KVC Verlag, 2019; pp. 9–32.

- Ruggeri, K.; Farrington, C.; Brayne, C. A Global Model for Effective Use and Evaluation of e-Learning in Health. Telemed. J. E-Health 2013, 19, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thyrian, J.R.; Boekholt, M.; Hoffmann, W.; Leiz, M.; Monsees, J.; Schmachtenberg, T.; Schumacher-Schönert, F.; Stentzel, U. Die Prävalenz an Demenz erkrankter Menschen in Deutschland–eine bundesweite Analyse auf Kreisebene. Nervenarzt 2020, 91, 1058–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmboe, E.S.; Lipner, R.S.; Greiner, A.C. Assessing Quality of Care. JAMA 2008, 299, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okun, S.; Goodwin, K. Building a Learning Health Community: By the People, for the People. Learn. Health Syst. 2017, 1, e10028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, F.S.; Jackson, J.; Ware, C.; Churchyard, R.; Hanseeuw, B.; International Interdisciplinary Young Investigators Alzheimer’s & Dementia. Interdisciplinary and Transdisciplinary Perspectives: On the Road to a Holistic Approach to Dementia Prevention and Care. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. Rep. 2020, 4, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenkel, M.O.; Pollak, K.M.; Schilling, O.; Voigt, L.; Fritzsching, B.; Wrzus, C.; Egger-Lampl, S.; Merle, U.; Weigand, M.A.; Mohr, S. Stressors Faced by Healthcare Professionals and Coping Strategies During the Early Stage of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Germany. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0261502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sensky, T. The Unconscious at Work: Individual and Organizational Stress in the Human Services. BMJ 1995, 310, 608–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klass, D. Will E-Learning Improve Clinical Judgement? BMJ 2004, 328, 1147–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klerings, I.; Weinhandl, A.S.; Thaler, K.J. Information Overload in Healthcare: Too Much of a Good Thing? Z. Evid. Fortbild. Qual. Gesundhwes. 2015, 109, 285–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piotrkowicz A, Dimitrova V, Hallam J, Price R. Towards Personalisation for Learner Motivation in Healthcare: A study on using learner characteristics to personalise nudges in an e-Learning context. UMAP ’20 Adjunct, July 14–17, 2020, Genoa, Italy © 2020 Association For Computing Machinery. Published online 13. Juli 2020.

- Akyuz, S.; Yavuz, F. Digital Learning in EFL Classrooms. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 197, 766–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Shea, E. Self-directed learning in nurse education: a review of the literature. Journal Of Advanced Nursing. 2003, 43, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.H. Web-based E-Learning System Supporting an Effective Self-Directed Learning Environment. J. Korea Contents Assoc. 2011, 11, 524–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challco, G.C.; Andrade, F.R.H.; Borges, S.S.; Bittencourt, I.I.; Isotani, S. Toward a Unified Modeling of Learner’s Growth Process and Flow Theory. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2016, 19, 215–227. [Google Scholar]

- Littlejohn, A. The Tip of the Iceberg. RELC J. 2008, 39, 214–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gooding, H.C.; Mann, K.; Armstrong, E. Twelve Tips for Applying the Science of Learning to Health Professions Education. Med. Teach. 2017, 39, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosteniuk, J.G.; Morgan, D.G.; O’Connell, M.E.; Kirk, A.; Crossley, M.; Teare, G.T.; ... Quail, J.M. Simultaneous Temporal Trends in Dementia Incidence and Prevalence, 2005–2013: A Population-Based Retrospective Cohort Study in Saskatchewan, Canada.

- Malek, M.; Nitsche, J.; Dinand, C.; Ehlers, J.; Lissek, V.; Böhm, P.; Derksen, E.-M.; Halek, M. Interprofessional Needs Analysis and User-Centred Prototype Evaluation as a Foundation for Building Individualized Digital Education in Dementia Healthcare Supported by Artificial Intelligence: A Study Protocol. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scerbe, A.; O’Connell, M.E.; Astell, A.; Morgan, D.; Kosteniuk, J.; DesRoches, A. Digital Tools for Delivery of Dementia Education for Healthcare Providers: A Systematic Review. Educ. Gerontol. 2019, 45, 681–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamri, H.; Lowell, V.L.; Watson, W.R.; Watson, S.L. Using Personalized Learning as an Instructional Approach to Motivate Learners in Online Higher Education: Learner Self-Determination and Intrinsic Motivation. J. Res. Technol. Educ. 2020, 52, 322–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joy, J.; Renumol, V.G. An Ontology-Based Hybrid E-Learning Content Recommender System for Alleviating the Cold-Start Problem. Educ. Inf. Technol. Published online 30 March 2021.

- Benhamdi, S.; Babouri, A.; Chiky, R. Personalized Recommender System for e-Learning Environment. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2016, 22, 1455–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, K.G.; Donaldson, J.F. Contextual Tensions of the Clinical Environment and Their Influence on Teaching and Learning. Med. Educ. 2004, 38, 448–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van De Wiel, M.W.J.; Van Den Bossche, P.; Janßen, S.; Jossberger, H. Exploring Deliberate Practice in Medicine: How Do Physicians Learn in the Workplace? Adv. Health Sci. Educ. 2010, 16, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiakas, K.; Barakova, E.; Khan, J.V.; Markopoulos, P. BrainHood: Towards an Explainable Recommendation System for Self-Regulated Cognitive Training in Children. In Proceedings of the 13th Pervasive Technologies Related to Assistive Environments Conference (PETRA ’20), June 30-July 3, 2020, Corfu, Greece; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 6 pages.

- Cooper, A. About Face 3: The Essentials of Interaction Design, 2007.

- Showalter, J.W.; Showalter, G.L. From Form to Function and Appeal: Increasing Workplace Adoption of AI Through a Functional Framework and Persona-Based Approach. J. AI Robot. Workplace Autom. 2021, 1, 142–156. [Google Scholar]

- Casiddu, N.; Burlando, F.; Nevoso, I.; Porfirione, C.; Vacanti, A. Beyond personas. Machine Learning to personalise the project. AGATHÓN Int. J. Archit. Art Des. 2022, 12, 226–233. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales, S.; O’Keefe, L.; Gutzman, K.; Viger, G.; Wescott, A.B.; Farrow, B.; Heath, A.P.; Kim, M.C.; Taylor, D.; Champieux, R.; Yen, P.Y.; Holmes, K. Personas for the Translational Workforce. J. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2020, 4, 286–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björgvinsson, E.; Ehn, P.; Hillgren, P.A. Design Things and Design Thinking: Contemporary Participatory.

- Luck, R. Participatory Design in Architectural Practice: Changing Practices in Future Making in Uncertain Times. Des. Stud. 2018, 59, 139–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Könings, K.D.; Seidel, T.; Van Merriënboer, J.J. Participatory design of learning environments: integrating perspectives of students, teachers, and designers. Instructional Science, 2014, 42, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitzinger, J. Qualitative Research: Introducing Focus Groups.

- Tausch, A.; Menold, N. Methodological Aspects of Focus Groups in Health Research. Global Qual. Nurs. Res. 2016, 3, 233339361663046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birchall, M.A.; Lee, L.; Richardson, A. Focus Groups. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 1999, 25, 556–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Balushi, K. The Use of Online Semi-Structured Interviews in Interpretive Research. Int. J. Sci. Res. (IJSR) 2018, 7, 2319–7064. [Google Scholar]

- Mayring, P. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse. UVK Univ.-Verl. Konstanz 1994, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Kettanurak, V.; Ramamurthy, K.; Haseman, W. User Attitude as a Mediator of Learning Performance Improvement in an Interactive Multimedia Environment: An Empirical Investigation of the Degree of Interactivity and Learning Styles. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2001, 54, 541–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefkowitz, R.F. Enhancement of Achievement and Attitudes Toward Learning of Allied Health Students Presented with Traditional Versus Learning-Style Instruction on Medical/Legal Issues of Healthcare. Perspect. Health Inf. Manag. 2006, 3, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Frenk, J.; Chen, L.; Bhutta, Z.; Cohen, J.; Crisp, N.; Evans, T.; ... Zurayk, H. Health Professionals for a New Century: Transforming Education to Strengthen Health Systems in an Interdependent World. Lancet 2010, 376, 1923–1958. [CrossRef]

- Back, D.A.; Behringer, F.; Haberstroh, N.; Ehlers, J.P.; Sostmann, K.; Peters, H. Learning Management System and e-learning tools: An experience of medical students’ usage and expectations. [Journal Name] 2016, [Volume], [Page Range].

- Curran, V.; Fleet, L. A Review of Evaluation Outcomes of Web-Based Continuing Medical Education. Med. Educ. 2005, 39, 561–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertens, F.; De Groot, E.; Meijer, L.; Wens, J.; Cherry, M.G.; Deveugele, M.; Damoiseaux, R.; Stes, A.; Pype, P. Workplace Learning Through Collaboration in Primary Healthcare: A BEME Realist Review of What Works, for Whom and in What Circumstances: BEME Guide No. 46. Med. Teach. 2017, 40, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, D. Medical Students’ Perceptions and an Anatomy Teacher’s Personal Experience Using an E-Learning Platform for Tutorials During the COVID-19 Crisis. Anat. Sci. Educ. 2020, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanelli, M. Knowledge and Process Management in Health Care Organizations. Methods Inf. Med. 2004, 43, 525–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soong, A.; Car, L. Digital Education for Guidelines Adoption and Adherence: Preliminary Findings from a Systematic Review. BMJ Evid.-Based Med. 2018, 23, A16–A17. [Google Scholar]

- Pontefract, S.; Wilson, K. Using electronic patient records: defining learning outcomes for undergraduate education. BMC Medical Education 2019, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, S.K.; Langer, T.; Luff, D.; Rider, E.A.; Brandano, J.; Meyer, E.C. Interprofessional Learning to Improve Communication in Challenging Healthcare Conversations: What Clinicians Learn From Each Other. J. Contin. Educ. Health Prof. 2019, 39, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopra, V.; Flanders, S.A.; O’Malley, M.; Malani, A.N.; Prescott, H.C. Sixty-Day Outcomes Among Patients Hospitalized with COVID-19. Ann. Intern. Med. 2021, 174, 576–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, S.; MacLeod, M.; Schiller, C. ’It’s Complicated’: Staff Nurse Perceptions of Their Influence on Nursing Students’ Learning. Nurse Educ. Today 2018, 63, 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, M.; Payne, S.; Froggatt, K. All Tooled Up: An Evaluation of End-of-Life Care Tools in Care Homes in North Lancashire. End of Life Care 2009, 3, 73. [Google Scholar]

- Block, B.N. The Computer Model of Mind. In Osherson, D.H.; Smith, S.E. (Eds.), Thinking: An Invitation to Cognitive Science, Ed.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Varela, F.; Thompson, J.E.; Rosch, E. The Embodied Mind; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Attenborough, J.; Abbott, S.; Brook, J.; Knight, R. Everywhere and nowhere: Work-based learning in healthcare education. Nurse Education in Practice 2019, 36, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, R. Why Information Technology Inspired, but Cannot Deliver Knowledge Management. Calif. Manage. Rev. 1999, 41, 103–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonaka, I.; Takeuchi, H. The Knowledge-Creating Company; University Press, 1995.

- Frankel, A. Nurses’ Learning Styles: Promoting Better Integration of Theory into Practice. Nursing Times 2009, 105, 24–27. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Barton, A. Improving Environments for Learning: Implications for Nursing Faculty. The Journal of nursing education 2018, 57, 515–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, H.M.S. Hybrid E-Learning Acceptance Model: Learner Perceptions. Decis. Sci. J. Innov. Educ. 2010, 8, 313–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, A.; Tritter, J. Focus Group Method and Methodology: Current Practice and Recent Debate. Int. J. Res. Method Educ. 2006, 29, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, L.P. Focus Group Discussion: A Tool for Health and Medical Research. Singapore Med J 2008, 49. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, C.; Milham, R.P. The Personas’ New Clothes: Methodological and Practical Arguments Against a Popular Method. Proc. Hum. Factors Ergon. Soc. Annu. Meet. 2006, 50, 634–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowatsch, T.; Otto, L.; Harperink, S.; Cotti, A.; Schlieter, H. A Design and Evaluation Framework for Digital Health Interventions. IT 2019, 61, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, L.; Xiao, J. Persona Profiling: A Multi-dimensional Model to Study Learner Subgroups in Massive Open Online Courses. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2022, 27, 5521–5549. [Google Scholar]

- Schäfer, K.; Rasche, P.; Bröhl, C.; et al. Survey-based personas for a target-group-specific consideration of elderly end users of information and communication systems in the German health-care sector. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2019, 132, 103924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yström, A.; Peterson, L.; Von Sydow, B.; Malmqvist, J. Using Personas to Guide Education Needs Analysis and Program Design. Proc. 6th Int. CDIO Conf., École Polytechnique, Montreal, June 15-18, 2010.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).