1. Introduction

Concerns about microplastics, i.e., synthetic polymer materials smaller than 5mm, have surged since the issue was first discovered in the 1970s. Globally, many scientists have revealed the adverse effects of microplastics on marine life, which are widely distributed in marine ecosystems, establishing it as a crucial aspect of the plastic waste problem on land and sea. Particularly, research on the impacts on marine ecosystems and human health is being conducted actively, leading to increased attention in this area.

Since sewage flows into the oceans, microplastics found in sewage can have a direct impact not only on marine animals but also on human health. This underscores the need for a deep understanding of the microplastics issue and the development of practical solutions. Recognizing and accurately assessing the impact of microplastics in sewage is a crucial first step in establishing sustainable strategies for protecting marine ecosystems and human health.

Studies such as "Environmental fate and impacts of microplastics in aquatic ecosystems"[

1] and "The long legacy left behind by plastic pollution"[

2] delve deeply into the presence and effects of microplastics in aquatic environments. They provide critical information on how microplastics move and degrade within marine and freshwater ecosystems and their impacts on marine life. Particularly, these studies analyze how the ability of microplastics to absorb pollutants and transfer them through different trophic levels poses a serious threat to ecosystems.

Despite ongoing research efforts, accurately distinguishing microplastics from natural materials remains challenging. The identification of microplastics based solely on shape or color is nearly impossible, necessitating the use of advanced analytical techniques. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) and Raman Spectroscopy [

3] can be employed to separate microplastics from organic materials and sand. However, due to the small size and complexity of microplastics, methods combining Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) with Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDX) [

4] are also required. These techniques allow for the analysis of the morphological and elemental characteristics of microplastics. Additionally, Pyrolysis Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (Py-GC/MS) [

5] can be used to break down polymers into identifiable chemical markers, distinguishing microplastics from substances with similar appearances. While advanced imaging techniques and machine learning algorithms can enhance detection capabilities, ultimate confirmation relies on spectroscopic methods for accurate analysis.

Nevertheless, we aim to develop a method that leverages computer vision technology to identify and classify microplastics in wastewater environments quickly and effectively, without the need for complex analytical equipment. This approach offers an automated solution that, while sacrificing some degree of accuracy, allows for the rapid processing of microplastics. Such a technological approach can facilitate more extensive and quicker monitoring of microplastic distribution and impacts, enhancing our understanding and response to this environmental challenge.

We propose a new methodology that utilizes computer vision and deep learning technologies to recognize and quantify microplastics effectively. This approach is crucial for accurately assessing the direct impacts of microplastics found underwater on marine life and human health. Based on these assessments, serves as a vital initial step in establishing sustainable strategies for the protection of marine ecosystems and human health.

The integration of computer vision and deep learning automates identifying and classifying microplastics in complex underwater environments, overcoming the limitations of traditional methodologies and enabling faster and more accurate data collection. This technological approach allows for more precise monitoring of the distribution and impacts of microplastics, providing a foundation for using the results in environmental protection and policy-making processes.

In areas like microplastic detection, diverse research approaches significantly benefit from public datasets. Open datasets play a crucial role by offering researchers worldwide opportunities for collaboration and technological development, thereby fostering cooperation and innovation in microplastic research. This establishes a platform where researchers from various backgrounds can join forces to solve problems.

Therefore, through our research, we aim to deepen the understanding of the microplastic issue and present innovative technological approaches to address it, thereby making a practical contribution to solving microplastic pollution. To achieve this, we will introduce the development process, characteristics, and utilization methods of the dataset, and discuss the role and potential of computer vision and deep learning technologies in responding to the underwater microplastic problem.

2. Related works

2.1. The Problems of Microplastics

Regarding the environmental fate and impacts of microplastics on marine ecosystems, [

1] profoundly explores how the global distribution of microplastics can be consumed by marine life and the health effects this entails. Furthermore, this study provides an overall understanding of the microplastics issue by summarizing the major sources of various microplastics, as well as their pathways of movement and degradation in aquatic environments.

In parallel, [

2] details the process through which over 430 million tons of plastic are produced annually, with about two-thirds of it immediately turning into waste that contaminates the oceans and even enters the human food chain. This report emphasizes the severity of the issue through a comprehensive analysis of the toxicity and mechanical impacts of microplastics on marine animals and plants, highlighting the hazards of microplastics.

Thus, through various studies, a multifaceted understanding of the microplastic issue is facilitated, and by comprehensively reviewing the impacts on marine ecosystems and human health, the urgent need to address microplastic pollution is emphasized.

These studies provide valuable information on how microplastics move and degrade within marine and freshwater ecosystems and their effects on marine life. In particular, the ability of microplastics in sewage to absorb pollutants and transfer them to other nutritional levels poses a serious threat to ecosystems. One method to measure the amount of microplastics in sewage is counting the number of microplastics, which can be done by object detection deep learning models. Additionally, segmentation deep learning models enable an easy measurement of the overall quantity of microplastics.

2.2. Approaches with Deep Learning

Along with attempts to segment microplastic fibers in digital images using deep learning methods, there is research on automatically counting and classifying microplastics of 1-5mm size [

6]. This study achieves a high accuracy of around 85% by segmenting microplastics in RGB images and evaluating various machine learning approaches such as KNN, Random Forest, and SVM RBF. Additionally, [

7] develops practical applications based on open-source computer vision and machine learning algorithms, enabling the quick and automatic counting and classification of microplastics into four shape and size categories. This research serves as a useful tool for revealing information that existing research approaches could not detect, contributing to the development of standardized methodologies in microplastic research. However, both studies use data taken in a clean state on a white background. In real environments where microplastics are collected, they are observed entangled in filters in complex states. Therefore, for practical use, the post-processing step of transferring and organizing on a white background takes too long to be a viable rapid-processing method.

Research [

8] uses neural networks to perform segmentation of microplastic particles with the intention of removing them in real-time after placing the sand from beaches on a conveyor belt. Thus, this study also deals with microplastics of a size identifiable by the naked eye. It focuses on model lightweight for mounting on mobile devices, comparing U-net and MultiResUNet, and introduces optimized versions based on kernel weight histograms: Half U-net, Half MultiResUNet, and Quarter MultiResUNet. The Half MultiResUNet showed the best performance in terms of recall-weighted F1 score and mIoU with significantly reduced computational requirements. While segmentation models for microplastics in beach sand could be used for microplastics in sewage, the form of microplastics filtered by sewage filters differs from that in sand, making direct application challenging.

3. Sewage Microplastic Collection Device

Due to organic matter contained in sewage plastic images, which can lead to misidentification of microplastics, it is necessary to remove organic matter. For this purpose, the method of effectively removing organic matter from samples using the Fenton oxidation reaction [

9] can be utilized. Applying this method and using the organic matter removal and filter device shown in

Figure 1, organic matter was removed from samples collected at a water treatment plant, and microplastics were separated. The overall configuration of the iron filter starts with a coarse filter at the top and is composed of progressively finer filters through five stages. The mesh size of the iron filter for collecting microplastics in sewage is arranged in five stages from the top where sewage enters: 500µm, 250µm, 134µm, 63µm, and 25µm. By passing sewage through this filter, microplastics of various sizes ranging from 50µm to 10mm contained in the sewage can be collected. Since the collected microplastics are too small to be seen with the naked eye, they must be imaged through a microscope.

4. Dataset Construction

A dataset focusing on microplastics filtered using iron filters in sewage is introduced. As depicted in

Figure 2, the resolution of the original microscope images collected is 2592x1944. For deep learning-based detection and segmentation tasks, these images are divided into sizes of 224x224 and 512x512, respectively.

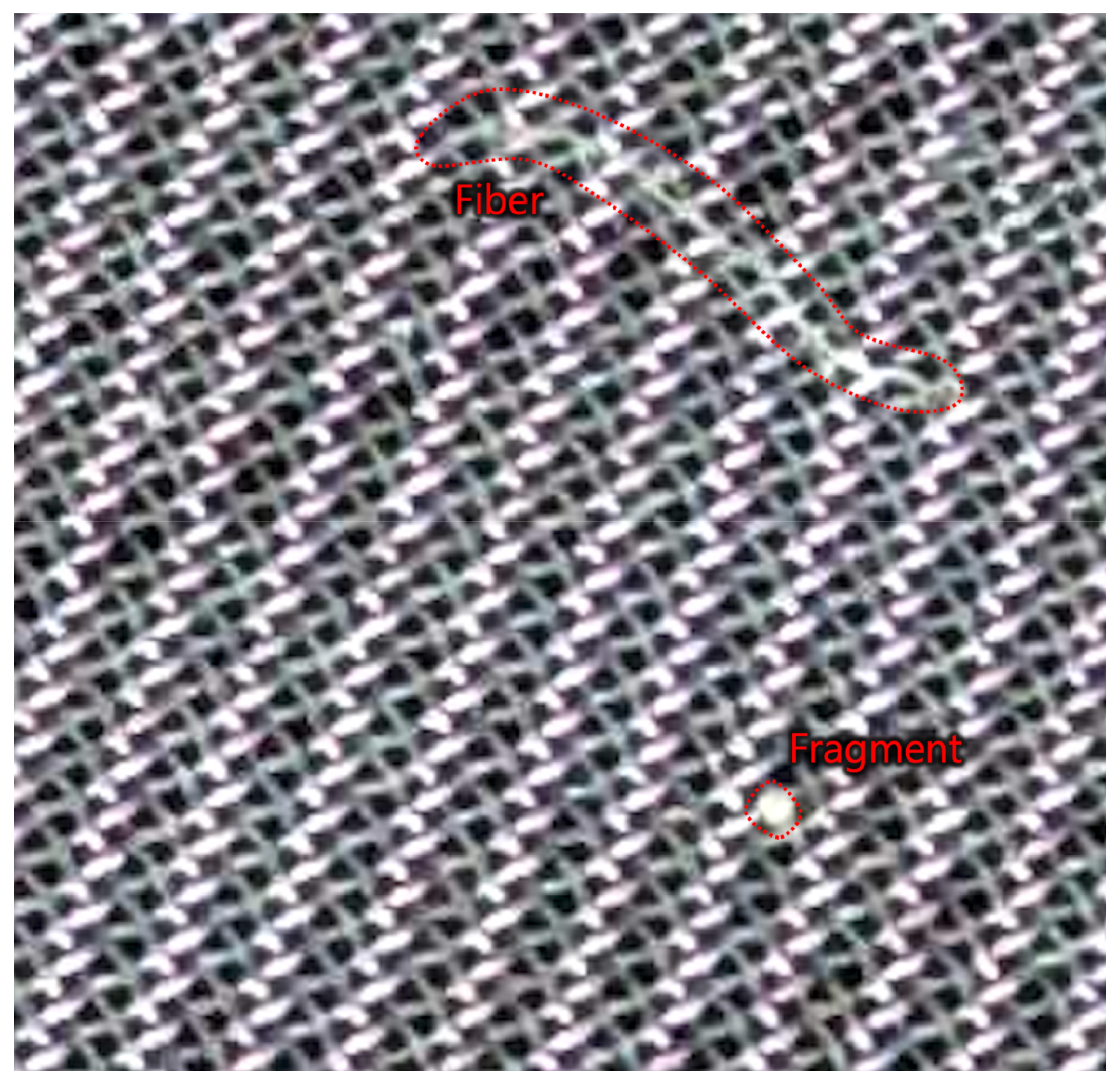

The dataset is composed as follows: For the detection task, the dataset consists of 167,195 images for training, 87,264 for validation, and 87,264 for testing. For the segmentation task, the dataset includes 31,963 images for training, 3,995 for validation, and 3,995 for testing. Microplastics are easily observed in the form of broken fragments and fibers shed from clothing. Thus, as shown in

Figure 3, classes are divided into Fiber and Fragment. Therefore, deep learning models should be designed to distinguish between fibers and fragments in the segmentation and detection processes.

The diversity and large volume of the dataset provide a foundation for the development of highly accurate models in microplastic research and are expected to promote technical advancements in the field of environmental protection and pollution monitoring.

During the dataset’s labeling process, the platform LabelBox[

10] was utilized to carry out efficient labeling tasks. Despite some microplastics being partially obscured by the filter mesh, a method was adopted that included labeling the entire area, covering even the obscured parts. This approach was essential for the accurate recognition of microplastics. Labeling was conducted in two forms: Bounding boxes for Detection and Masks for Segmentation.

The accuracy of labeling tasks is of utmost importance in the dataset construction process. In this study, an approach dividing the team into two groups, labelers, and validators, was adopted to ensure this accuracy. Labelers accurately identified the location and shape of microplastics and labeled the data for Detection and Segmentation tasks using Bounding boxes and Masks.

After the labeling tasks, the validator group reviewed the labeled data to correct mislabeled parts or missing information. This dual verification process significantly improved the accuracy of the data. The labeling platform LabelBox was utilized to facilitate efficient collaboration and data management among teams. The dataset constructed through this process was used to train deep learning models for the detection and classification of microplastics, contributing to the improvement of the models’ performance.

5. Experiments

5.1. Segmentation

For segmentation learning, two neural network architectures were employed to achieve precise segmentation of microplastics.

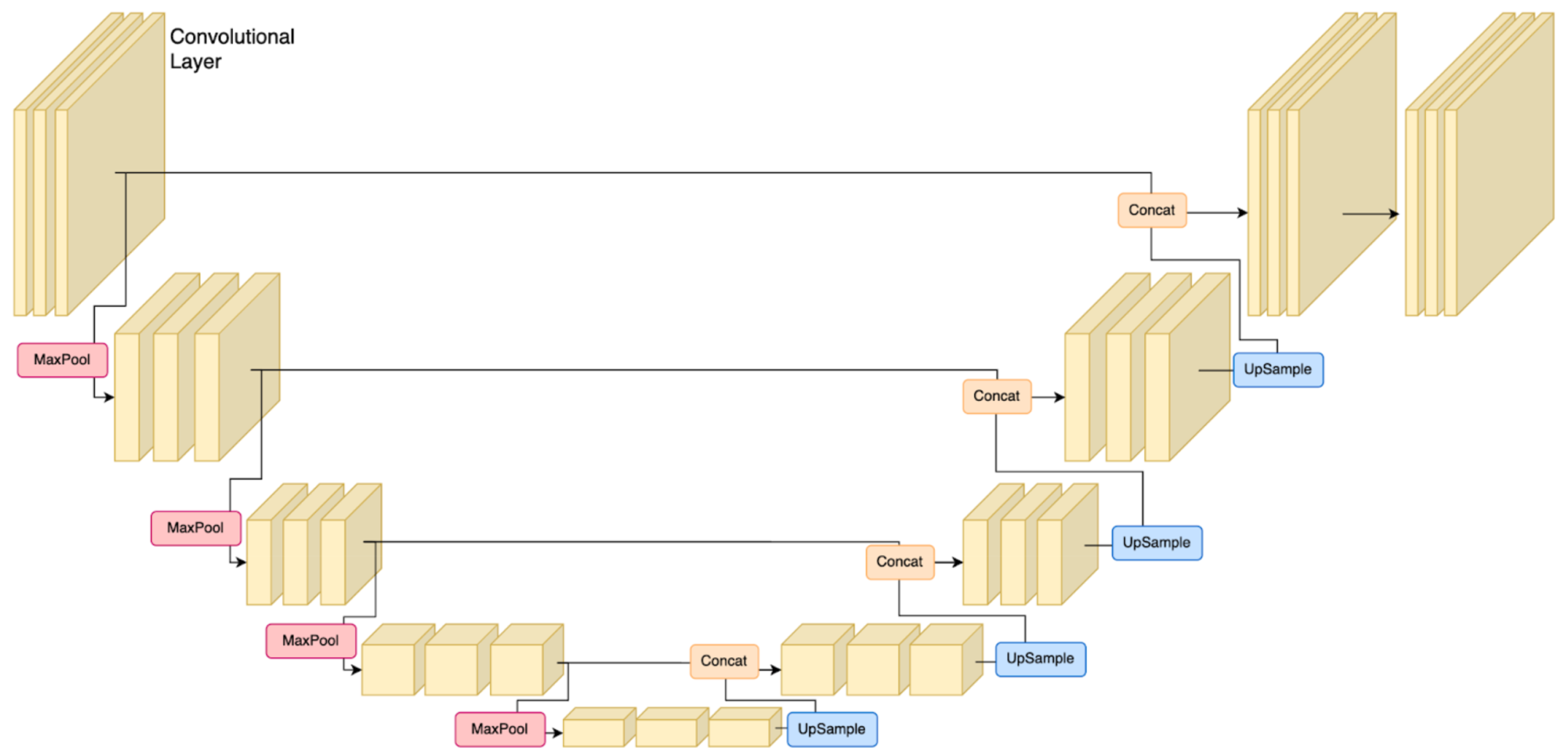

Unet[

11], as illustrated in

Figure 4, features a U-shaped architecture, indicating that the encoder and decoder parts of the model are symmetrical. The encoder extracts features from the input image, while the decoder predicts the class to which each pixel of the original image belongs based on these features. Additionally, skip connections are utilized between the encoder and decoder to provide a direct path from the encoder to the decoder. This structure assists the model in accurately restoring both the overall structure and fine details of the image.

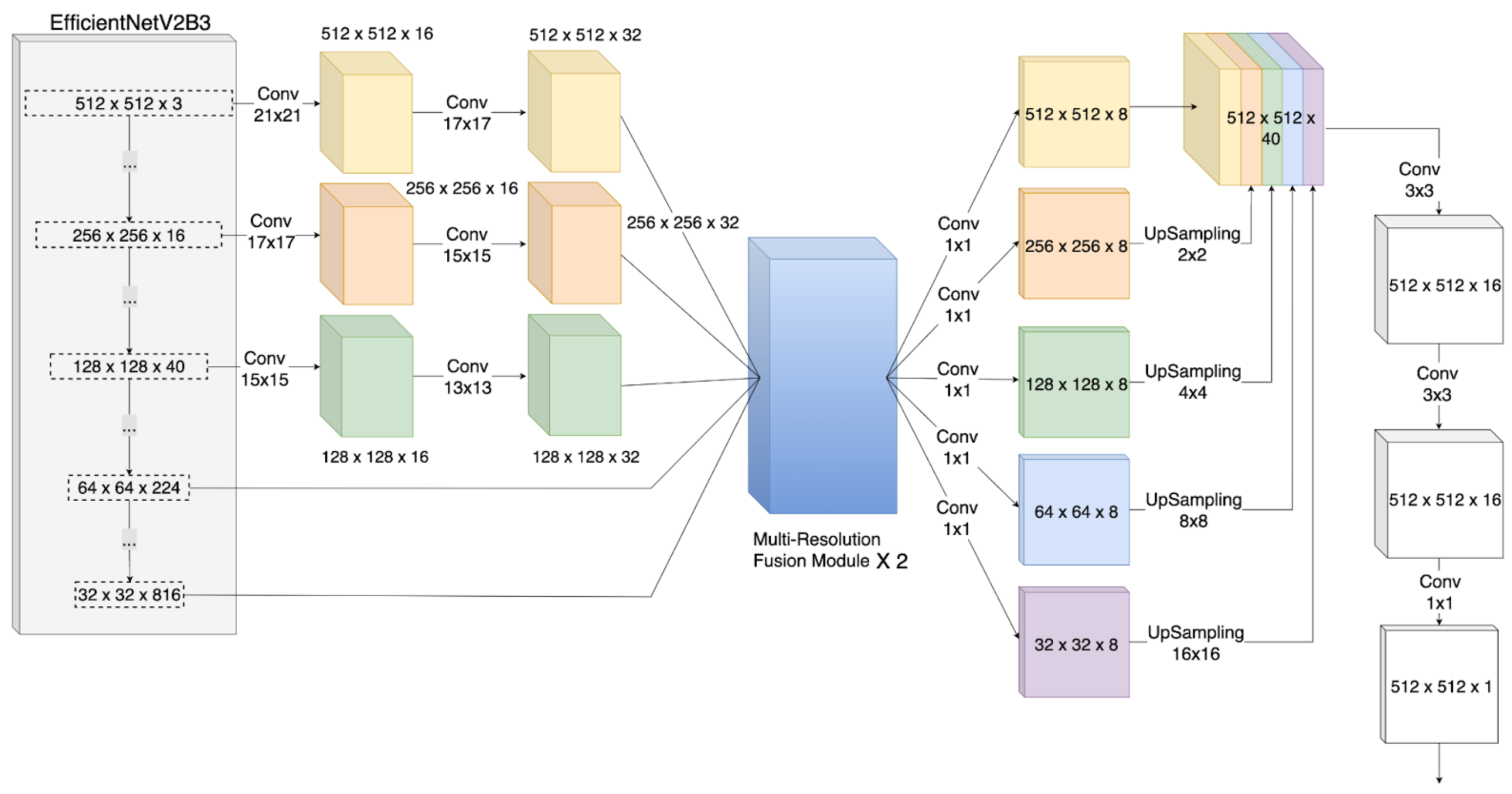

The neural network structure represented by

Figure 5, EfficientNetV2B3 + MRFM x2 [

12], is specially designed for the segmentation of microplastic particles. This innovative structure uses the EfficientNetV2B3 model [

13,

14] as its backbone, which allows for efficient feature extraction and feature fusion. Additionally, it applies the Multi-Resolution Fusion Module (MRFM) [

12] twice to integrate features obtained at various resolutions. This approach enables the capture of finer details of microplastics, achieving accurate segmentation.

For the performance evaluation of segmentation, three key metrics were used: Recall, Precision, and mIoU. These evaluation metrics comprehensively indicate how accurately the model can segment and identify microplastics.

The experimental results, as shown in

Table 1, indicate that the Unet model achieved a Recall of 55.22%, Precision of 78.83%, and mIoU of 59.4%. This demonstrates that the Unet model has achieved considerable accuracy in microplastic segmentation. Additionally, the high Precision value suggests that the model minimizes errors when segmenting microplastics. The EfficientNetV2B3 + MRFM x2 model showed a Recall of 82.14%, Precision of 85.71%, and mIoU of 63.14%. With both Recall and Precision being high, the prediction error is low, and a high proportion of plastics is recognized. Therefore, the use of such neural network models for 3-Class Segmentation tasks—separating microplastic fibers and fragments, as well as other backgrounds—can be beneficially utilized for future microplastic analysis and monitoring.

5.2. Detection

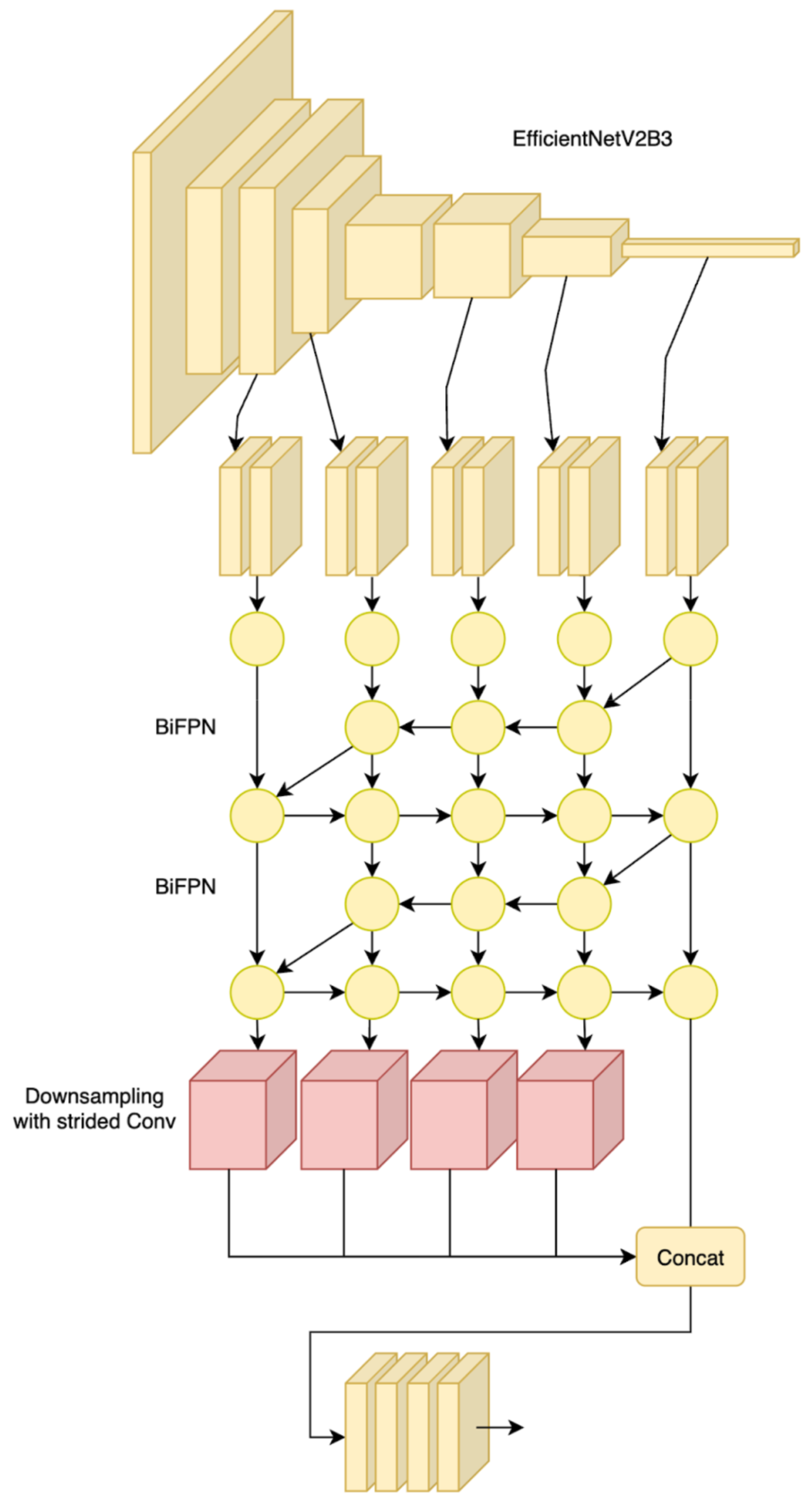

As shown in

Figure 6, the neural network structure for detection uses EfficientNetV2B3 as the Backbone and BiFPN[

15] as the Head, with the YOLO[

16,

17,

18] algorithm adopted for training. The choice of the YOLO training algorithm is specifically to utilize its unique concepts such as Grid, YOLO Loss, Default box, and Responsible.

EfficientNetV2B3 serves as the model’s Backbone, providing high performance and efficiency, while BiFPN contributes to enhancing the accuracy of object detection by integrating features at various resolutions. Furthermore, using YOLO as the training algorithm allowed for the fast and accurate prediction of the locations of objects within each image. This played a crucial role in increasing detection accuracy through the use of Grid for image segmentation, enhancing training efficiency with YOLO Loss, and improving detection precision with the concepts of Default box and Responsible.

AP50[

19] was utilized as a comprehensive performance evaluation metric. Additionally, Recall, Precision, and F1Score were measured as additional performance metrics for the two main classes of microplastics, Fiber and Fragment.

Table 2 presents the experimental performance results. Through these results, we have demonstrated the effectiveness of the model in detecting and classifying microplastics efficiently. However, the values of Recall, Precision, and F1Score for each of the Fiber and Fragment classes suggest there is still room for improvement. Particularly, Fibers, being irregularly shaped and long, have significantly lower recognition performance, indicating a need for considerable efforts toward performance enhancement.

6. Discussion

Microplastics entering sewage systems pose a significant environmental issue that can directly impact humans and ecosystems. Given the severity of this issue, a dataset of microplastics in sewage is expected to have substantial practical effects on research in this field. Experimentally, we achieved a level of performance that allows for the practical identification and classification of sewage microplastics using computer vision technologies, namely Segmentation and Detection.

This dataset and related technologies are anticipated to contribute to environmental protection and the maintenance of ecosystem health through the accurate detection and classification of microplastics. Furthermore, this research could play a crucial role in understanding the extent and sources of microplastic pollution, providing scientific evidence necessary for developing related policies and regulations.

However, there are still limitations. Since the dataset of microplastics in sewage is collected only in Korea, it may have limitations in representing various environmental conditions worldwide. There is a need to construct a dataset that encompasses a variety of sewage environments and sources of microplastic pollution. Another limitation is the difficulty of data identification caused by the iron filtration mesh, as illustrated in

Figure 7. During the process of filtering microplastics with an iron mesh, the structure of the mesh itself can create background noise in the images, making it challenging to distinguish microplastics. This issue becomes more pronounced when the small size of the microplastics overlaps with the fine mesh structure of the filter. Microplastics that are obscured by the mesh or recognized as similar in shape to the structure of the mesh can cause errors in the identification and classification process. This can make accurate counting and classification of microplastics challenging, potentially impacting the reliability of the research findings. Therefore, further research is needed to collect data in various environments and improve recognition performance related to the filtration mesh.

7. Conclusions

Environmental issues caused by plastic have been a continuous concern, with the problem of microplastics gaining increased attention for its severity. Addressing this issue necessitates the development of technologies capable of recognizing microplastics quickly and accurately. This study explored the potential of using computer vision and deep learning to contribute to solving this problem, particularly suggesting that recognizing plastic particles in sewage rather than in beach sand is more effective.

However, difficulties in recognizing microplastics during the sampling process using metal filters were identified. This is because the filters may obscure some microplastics, making recognition challenging. Despite these limitations, the performance results obtained through this research showed a certain level of recognition capability, but suggest that further research and technological development are necessary for more accurate recognition and classification. Notably, deep learning models for detection exhibited lower performance compared to segmentation because detection models often assume a fixed shape, whereas microplastics lack a defined shape. This is especially true for fibers, which are long and linear, leading to poorer performance compared to fragments. Thus, future research on deep learning models that consider detection and segmentation may be required.

By publicly sharing the developed dataset and example deep learning code, we provide other researchers with the opportunity to participate more easily in the development of technologies to address environmental problems related to microplastics. This will play a crucial role in facilitating collaboration within the research community and accelerating the advancement of microplastic detection and classification technologies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Lee.G. and Jhang.K.; methodology, Lee.G., Jung.J. and Moon.S.; software, Lee.G., Jung.J. and Moon.S.; validation, Lee.G. and Jhang.K.; formal analysis, Lee.G.; resources, Jung.J.; data curation, Jung.J.; writing—original draft preparation, Lee.G.; writing—review and editing, Jhang.K.; visualization, Lee.G.; supervision, Jhang.K.; project administration, Jhang.K.; funding acquisition, Jhang.K. and Jung.J.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

This work was partly supported by Institute of Information & communications Technology Planning & Evaluation (IITP) grant funded by the Korea government(MSIT) (No.RS-2022-00155857, Artificial Intelligence Convergence Innovation Human Resources Development (Chungnam National University)) and partly supported by the Starting growth Technological R&D Program (G21002568071) funded by the Ministry of SMEs and Startups(MSS, Korea).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Du, S.; Zhu, R.; Cai, Y.; Xu, N.; Yap, P.S.; Zhang, Y.; He, Y.; Zhang, Y. Environmental fate and impacts of microplastics in aquatic ecosystems: a review. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 15762–15784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Programme, U.N.E. Microplastics: The long legacy left behind by plastic pollution.

- Xu, J.L.; Thomas, K.V.; Luo, Z.; Gowen, A.A. FTIR and Raman imaging for microplastics analysis: State of the art, challenges and prospects. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2019, 119, 115629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiltz, J.A. Pyrolysis gas chromatography/mass spectrometry identification of poly(butadiene-acrylonitrile) rubbers. Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis 2000, 55, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermabessiere, L.; Himber, C.; Boricaud, B.; Kazour, M.; Amara, R.; Cassone, A.L.; Laurentie, M.; Paul-Pont, I.; Soudant, P.; Dehaut, A.; Duflos, G. Optimization, performance, and application of a pyrolysis-GC/MS method for the identification of microplastics. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry 2018, 410, 6663–6676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorenzo-Navarro, J.; Castrillón-Santana, M.; Santesarti, E.; De Marsico, M.; Martínez, I.; Raymond, E.; Gómez, M.; Herrera, A. SMACC: A System for Microplastics Automatic Counting and Classification. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 25249–25261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massarelli, C.; Campanale, C.; Uricchio, V.F. A Handy Open-Source Application Based on Computer Vision and Machine Learning Algorithms to Count and Classify Microplastics. Water 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.; Jhang, K. Neural Network Analysis for Microplastic Segmentation. Sensors 2021, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, Y.; Oh, J.; Lee, I.; Fan, C.; Pan, S.Y.; Jang, M.; Park, Y.K.; Kim, H. Total-organic-carbon-based quantitative estimation of microplastics in sewage. Chemical Engineering Journal 2021, 423, 130182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labelbox. Labelbox, 2024.

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation. Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention – MICCAI 2015; Navab, N., Hornegger, J., Wells, W.M., Frangi, A.F., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2015; pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, J.; Lee, G.; Jeong, J.; Kim, J.; Kim, J.; Jhang, K. Microplastic Binary Segmentation with Resolution Fusion and Large Convolution Kernels. Journal of Computing Science and Engineering 2024, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, M.; Le, Q. Efficientnet: Rethinking model scaling for convolutional neural networks. International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 2019, pp. 6105–6114.

- M.Tan., *!!! REPLACE !!!*; Le, Q. M.Tan.; Le, Q. EfficientNetV2: Smaller Models and Faster Training. Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Machine Learning; Meila, M.; Zhang, T., Eds. PMLR, 2021, Vol. 139, Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, pp. 10096–10106.

- Tan, M.; Pang, R.; Le, Q.V. Efficientdet: Scalable and efficient object detection. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2020, pp. 10781–10790.

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection. Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2016, pp. 779–788.

- Redmon, J.; Farhadi, A. YOLO9000: better, faster, stronger. Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2017, pp. 7263–7271.

- J.Redmon., *!!! REPLACE !!!*; Farhadi, A. J.Redmon.; Farhadi, A. Yolov3: An incremental improvement. arXiv preprint arXiv:1804.02767, arXiv:1804.02767 2018.

- Lin, T.Y.; Maire, M.; Belongie, S.; Hays, J.; Perona, P.; Ramanan, D.; Dollár, P.; Zitnick, C.L. Microsoft coco: Common objects in context. Computer Vision–ECCV 2014: 13th European Conference, Zurich, Switzerland, -12, 2014, Proceedings, Part V 13. Springer, 2014, pp. 740–755. 6 September.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).