Submitted:

22 April 2024

Posted:

23 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Overview of Biological Agents for Asthma

- -

- Omalizumab (Xolair®) is a recombinant monoclonal antibody specifically designed to target free IgE, preventing its interaction with the high-affinity FcεRI receptors found on the surface of basophils and mast cells [28,29]. Omalizumab treatment should be considered only for patients 6 years of age and older with asthma convincingly mediated by IgE -i.e., a positive skin test or in vitro reactivity to a perennial aeroallergen- and whose symptoms are inadequately controlled with inhaled corticosteroids [30].

- -

- Mepolizumab (Nucala®) is a humanized IgG1 monoclonal antibody that directly binds to IL-5, preventing its interaction with the alpha-chain of the IL-5 receptor from eosinophils and basophils [31,32]. First authorized in Spain in 2015, and currently indicated as additional treatment for severe refractory eosinophilic asthma in patients 6 years of age and older [33].

- -

- Reslizumab (Cinqaero®), the second available anti-IL5 biological agent in 2016, is indicated as an additional treatment in adult patients with severe eosinophilic asthma inadequately controlled with high-dose inhaled corticosteroids plus another maintenance treatment medication [34]. Reslizumab is solely designated for hospital use due to its requirement for intravenous administration.

- -

- Benralizumab (Fasenra®) is a humanized and afucosylated monoclonal antibody that binds with high affinity and specificity to the alpha-subunit of the receptors for IL-5 specifically expressed on the surface of eosinophils and basophils [35]. Authorized in Spain in 2018, it serves as an additional treatment in adult patients with severe eosinophilic asthma who are not adequately controlled despite high-dose corticosteroid treatment and long-acting beta-2 agonists [36].

- -

- Tezepelumab (Tezspire®), a human monoclonal antibody produced in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells using recombinant DNA technology that Blocks circulating thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TLSP) and prevents receptor binding. Authorized in Spain in 2022, tezepelumab is indicated as an additional maintenance treatment in adults and adolescents aged 12 years and older with severe asthma who are not adequately controlled despite high-dose inhaled corticosteroids in combination with another maintenance treatment [37].

- -

- Dupilumab (Dupixent®) is a recombinant monoclonal antibody that inhibits signaling of interleukin-4 (IL-4) and interleukin-13 (IL-13) which are involved in type-2 inflammation. Authorized in Spain in 2017, it is indicated as an additional maintenance treatment in adults and adolescents aged 12 years and older with severe asthma characterized by type-2 inflammation, evidenced by elevated blood eosinophils and/or elevated FeNO, who are not controlled with high-dose inhaled corticosteroids in combination with another maintenance treatment [38].

1.3. Post-Approval Pharmacovigilance of Biological Drug in Asthma

1.4. Justification and Aim of the Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Biological Medicines under Study

2.2. Data Source and Analysis of Cases Registered in the FEDRA Database

- Each notification of suspected ADRs does not establish certainty that the suspected drug caused the ADR; individual evaluation of each reported case is essential, considering factors like temporal sequence and positive re-exposure effect, among others, without leading to an unequivocal diagnostic judgment of causality.

- The accumulation of reported cases cannot be utilized to calculate incidence or estimate the risk of ADRS; instead, these data should be interpreted cautiously as notification rates, precluding comparisons of the safety of different drugs.

- The overall evaluation of reported cases of a drug-reaction association aims solely to identify potential signals of unknown risks within an epidemiological case history context.

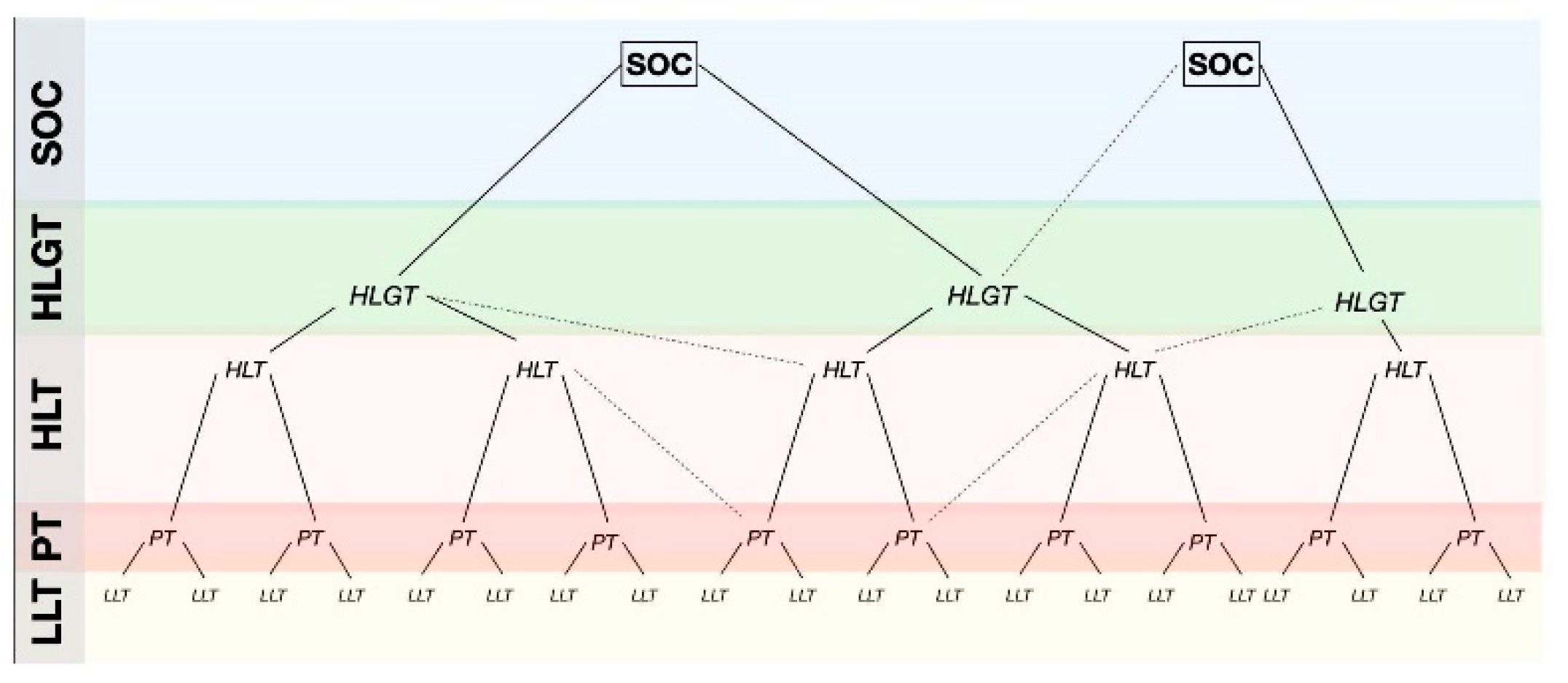

2.3. Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA)

2.4. Institutional Review Board Statement

3. Results

3.1. Global Findings from the Analysis of Overall Data

3.2. Active Ingredient

3.2.1. Omalizumab

- -

- Cutaneous Disorders were reported in 25% of cases in FEDRA: there are 166 cases (of 672) related to skin disorders. In addition to the ADRs described in SmPC, have been reported: atopic dermatitis, purpura, and hyperhidrosis.

- -

- In addition to headache, syncope, paresthesia, dizziness, and drowsiness, known in SmPC as ADRs of Nervous System, there were 122 cases registered with any of these in FEDRA, which represent 18% of those notified. It is worth highlighting vascular disorders of the central nervous system (Cerebrovascular accident, Transient ischemic attack, and Ischemic stroke); Tremor, Dyskinesias and movement disorders; and Seizure disorders.

- -

- Musculoskeletal and Connective Tissue Disorders are known for omalizumab (arthralgias, myalgia, swelling of the joints and systemic lupus erythematosus). In FEDRA the reactions that affect this SOC represent almost 16% n = 105. Back pain is the most reported ADR among those not described in SmPC, along with extremity pain, muscle weakness, muscle spasms, musculoskeletal stiffness, and discomfort in limbs.

- -

- Neoplastic Disorders: No formal carcinogenicity studies have been performed with omalizumab, nor are any benign or malignant adverse reactions described in the SmPC for Xolair®. However, in FEDRA there are 67 cases registered that link omalizumab with a neoplastic disorder, which represents 10% of its total cases. All these cases should be considered of interest and likely to generate a signal in pharmacovigilance. Malignant neoplasms of the breast are the most reported, although malignant neoplasms have also been reported in other locations: Colorectal neoplasms malignant; Lymphomas unspecified NEC; Respiratory tract and pleural neoplasms malignant cell type unspecified NEC.

- -

- The adverse reactions of the Immune System are known (local and systemic type I allergic reactions, anaphylaxis and anaphylactic shock, and appearance of antibodies against omalizumab). In FEDRA, it represented 9% (n = 59) of the total reported. Among those not included in SmPC, three cases of optic neuritis, three of multiple sclerosis and three cases of Sjögren's Syndrome stand out.

- -

- Complementary Explorations: The Xolair® SmPC does not contain a section on reactions linked to additional investigations, however the possibility of an increase in body weight as a consequence of treatment with omalizumab is described. In this series of cases, in FEDRA, there are 45 notifications that describe some disorder at the level of Complementary Examinations: the only term that could be of interest (n = 4) is decreased weight.

- -

- Infections or infestations are uncommon (pharyngitis) or rare (parasitic infections) according to SmPC. In FEDRA there are 43 cases of suspected ADRs to omalizumab related to the appearance of infections, which represent 6%. Herpes zoster virus infections may be of interest, as it is the most frequently reported infection.

- -

- Vascular Disorders described in SmPC with omalizumab are rare and limited to postural hypotension and flushing. But in FEDRA there are 34 cases that represent 5% of the total. Deep vein thrombosis was the most reported term not in SmPC.

- -

- Cardiac Disorders: While not mentioned in the Xolair® SmPC, omalizumab was associated with 29 cases registered in FEDRA, 4% of those reported including increased heart rate and coronary ischemic disorders (angina pectoris and myocardial infarction) as the most reported ADR terms.

- -

- Blood and Lymphatic System Disorders: The SmPC for Xolair® indicates that omalizumab may lead, with an unknown frequency, to the development of idiopathic thrombocytopenia, including severe cases. In FEDRA, a total of 25 cases (4%) were reported with suspected adverse events of omalizumab on blood parameters (anemic disorders and lymphadenopathy, not described in SmPC).

- -

- Pregnancy, puerperium, and perinatal diseases. Omalizumab crosses the placental barrier, but there is no risk of malformations or associated fetal/neonatal toxicity in SmPC, if clinically necessary, use during pregnancy may be considered. In FEDRA there are 19 cases (3%). The most numerous cases reported are related to abortion (n = 6).

- -

- Eye Disorders: Although not described in the Xolair® SmPC, 19 cases (3%) including eye and eyelid edema were reported in FEDRA.

- -

- Psychiatric Disorders. There are no adverse reactions related to any psychiatric disorder described in the Xolair® SmPC. However, there are 15 cases registered in FEDRA linking omalizumab to some psychiatric disorder, 2% of the total notifications. Anxiety-related disorders and symptoms are the most frequently reported ADRs.

- -

- In FEDRA, there are 13 cases linking the use of omalizumab to the appearance of disorders of the reproductive system and breast, 2% of the total. The Xolair® SmPC does not include terms related to this system or organ. There were found reactions that could be of interest, such as menstrual cycle disorders.

- -

- No mention of metabolic and nutritional disorders is made in the information contained in the Xolair® SmPC either. These reactions accounted for almost 2% of the cases in FEDRA (n=11). Decreased appetite was the only one to be considered of interest.

- -

- FEDRA contains 8 cases associating the use of omalizumab with some disorder of the ear and labyrinth, accounting for 1% of the total notifications of this drug. Hearing loss was the most reported ADR with 5 out of the 8 cases in this SOC. No ADRs with this type of disorder are currently described in the Xolair® SmPC.

3.2.2. Mepolizumab

- -

- Respiratory issues, constituting 30% of cases, include known reactions and exacerbation of treated conditions (n = 166).

- -

- Skin and subcutaneous reactions, also 30%, mostly align with hypersensitivity described in product info. There are 8 cases of alopecia that may be of interest.

- -

- Neurological symptoms, totaling 26%, mostly headaches and dizziness. Not specified in product info were: 15 cases of Paresthesia, Hypoesthesia or Dysesthesia (5 of them in a context of Severity); Muscle weakness and atrophy 6 cases (3 severe); Tremor 5 cases (3 severe); CNS vascular disorders: 4 cases (all 4 serious).

- -

- Regarding the Immune System, 105 cases (21%): our series predominantly included reactions already described in SmPC of hypersensitivity (systemic allergic reaction) and Anaphylaxis. But it can be explored if there is any relationship with other diseases or autoimmune symptoms (n = 5 cases): Lichen planus, Vasculitis, Telangiectasia, Pemphigoid, Disease related to immunoglobulin G4.

- -

- Musculoskeletal symptoms. There were 27 cases of arthralgia (5% of all cases reported with mepolizumab), 7 of them severe.

- -

- Cardiac issues are presently not outlined in the Mepolizumab® SmPC. Nonspecific symptoms (55 cases) whose alternative cause could be related to the underlying disease were noted, with 7 cases of arrhythmias reported as serious.

- -

- Vascular disorders (13%) exhibited 67 cases coded with 30 ADR terms including vasculitis, thrombosis, purpura, cyanosis, telangiectasia, hypertension, etc., all also described in hyper-eosinophilic conditions. In 9 cases, at least one of the following three terms were reported: Deep vein thrombosis, stroke, and /or pulmonary embolism.

- -

- Infections and infestations (13%) included upper respiratory infections and a case of visceral leishmaniasis. Herpes zoster infection stands out with statistical significance of notification.

- -

- Gastrointestinal symptoms (13%) are not mentioned in the mepolizumab SmPC. Of the 64 cases describing some GI symptom, 21 were regarded as serious clinical conditions.

- -

- Psychiatric issues were not covered in the mepolizumab SmPC and reported cases (n=29) in FEDRA were insufficient to delineate a clear ADR pattern.

- -

- Neoplasms reported to FEDRA included 24 cases (5%) encompassing male breast cancer (2), lung (3), and five cases gastrointestinal tract cancers that were particularly noteworthy.

3.2.3. Benralizumab

- -

- General Disorders and Administration Site Conditions: This was the most frequently reported category, comprising 42% (246 cases) of all cases. Fatigue was mentioned in 55 cases, with 9 cases being classified as severe asthenia.

- -

- Respiratory, Thoracic, and Mediastinal Disorders: These accounted for 34% (200 cases) of the total cases, but the symptoms described could be related to the underlying disease being treated, so they are not detailed.

- -

- Neurological Disorders symptoms were present in 26% of the cases (151 cases). However, most of these terms corresponded to headache (82 cases), a reaction already documented in the SmPC. The rest were too nonspecific and scattered for analysis.

- -

- Skin and Subcutaneous Tissue Disorders accounted for 16% of the cases (116 cases), with most falling under hypersensitivity reactions described in the product information. However, there were 6 cases of alopecia that may be of interest.

- -

- Musculoskeletal and Connective Tissue Disorders: They represented 15% of all cases (86 cases) with myalgia being the most notable (29 cases, 14% of them severe), followed by arthralgia (18 cases of which 22% were regarded as severe).

- -

- Gastrointestinal Disorders were 14% of all cases (85 cases), most corresponding to disorders listed in the product information or being too scattered for analysis. However, there were 14 cases with terms related to abdominal pain: 7 of abdominal discomfort, 5 of abdominal pain (one severe), and 5 of upper abdominal discomfort.

- -

- Immune System Disorders: This accounted for 13% of cases (75 cases), primarily comprising hypersensitivity reactions (systemic allergic reaction and cutaneous manifestations) and anaphylaxis.

- -

- Infections represented 11% of cases (68 cases). While many terms referred to pharyngeal infections already described in the SmPC, other infection-related terms appeared in 39 cases (more than half of all infections), with 19 of them being severe. The most relevant among them are those related to pneumonia: Unspecified pneumonia was reported in 5 cases, but it can be grouped together with other terms of specific pneumonia such as streptococcal pneumonia, fungal pneumonia, pneumonia due to COVID-19 (one case each) or even with another terms suggestive of pneumonia (pleural, productive cough...etc) reaching an important clinical meaning.

- -

- Cardiac disorders accounted for 11% of all notified cases (66 cases), with symptoms possibly related to coronary ischemia being notable: 7 cases of chest pain, 9 of chest discomfort and one Kounis´syndrome.

- -

- Vascular disorders: The terminology dispersion in this category hinders interpretation, but blood pressure disorders stand out: hypertension (5 cases) and hypotension (5 cases).

- -

- Psychiatric disorders: Although not described in the product information, there were 45 reported cases (8%), with sleep disorders being notable, accounting for 22 of the 52 terms (nearly half) grouped under psychiatric disorders. Other remarkable terms were those related to anxiety -anxiety (4), nervousness (4)- or mood disorders (4)

- -

- Not described in the SmPC were also weight increase (3 cases) and decreased appetite (3 cases)

3.2.4. Dupilumab

- -

- Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders were the most frequent suspected ADRs, with 29% (159 cases) of all notified cases. Adverse reactions not described in the SmPC included alopecia /alopecia areata with 21 cases and psoriasis with 11 cases respectively.

- -

- The second most reported category was infections and infestations, with 28% (153 cases) of the cases recorded in FEDRA. Despite the dupilumab SmPC mentions a section on infections and infestations, detailing conjunctivitis, oral herpes, and the potential impact on responses to helminthic infections, FEDRA reported additional cases such as pneumonia (11 cases), lower respiratory tract infections (3 cases), and cellulitis (3 cases).

- -

- FEDRA records 136 cases (25%) of General disorders and conditions at the local administration site. These types of disorders are addressed in the dupilumab SmPC; FEDRA highlights pyrexia (14 cases), malaise (12 cases), asthenia (9 cases) and fatigue (9 cases).

- -

- In FEDRA, 88 cases (16%) of ocular disorders secondary to dupilumab were reported, although the SmPC already lists conditions such as allergic conjunctivitis, keratitis, blepharitis, ocular pruritus, dry eye, and ulcerative keratitis. FEDRA reports additional symptoms like tearing, discomfort, and hyperemia, which may indicate the presence of already described ADRs.

- -

- FEDRA records 67 cases (12%) of nervous system disorders, not covered in the dupilumab SmPC, FEDRA highlights headaches (25 cases), dizziness (10 cases), and syncope (5 cases).

- -

- Furthermore, FEDRA lists 58 cases (10%) of musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders, with arthralgia being the most common, consistent with the SmPC. Other reported symptoms include myalgia (5 cases), bone pain (5 cases), and limb pain (5 cases).

- -

- There were also 47 cases (8%) describing abnormalities in Investigations, with decreased weight (5 cases), not mentioned in the SmPC, being noteworthy.

- -

- While gastrointestinal disorders were not listed as possible ADRs in the SmPC, FEDRA associated 35 cases (6%) with dupilumab, including vomiting and nausea (13 cases), diarrhea (5 cases), and 3 cases reported Crohn's disease as an adverse event.

- -

- Blood and lymphatic system disorders, described in the SmPC, were reported in FEDRA with 35 cases (6%), most of which involved eosinophilia (18 cases) already mentioned in the SmPC, and lymphadenopathy (11 cases) not previously described.

- -

- FEDRA also documented 23 cases (4%) of vascular disorders, including erythema (7 cases) and vasculitis (5 cases), none of which were previously reported in the SmPC.

- -

- Psychiatric disorders were noted with 21 (3%) cases, the most prevalent being anxiety, stress, and nervousness, totaling 11 cases together.

- -

- The results of immune system disorders in FEDRA included 16 cases (2%), with the most characteristic being eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA) with 3 cases.

- -

- Additionally, 11 cases (2%) of cardiac disorders were reported in FEDRA, with tachycardia (5 cases) being the most frequent.

- -

- Metabolic and nutritional disorders were described in 6 cases (1%), with abnormal weight loss (2 cases) and decreased appetite (2 cases) being notable and absent in the SmPC.

3.2.5. Reslizumab

3.2.6. Tezepelumab

4. Discussion

4.1. Industry Reporting

4.2. SmPC and Risk

4.3. ADR and Underlying Disease

4.4. Eosinophilic Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis (EGPA)

4.5. Neoplastic Disorders and Biological Therapy

4.6. Vascular Disorders

4.7. ADR Comments for Specific Biological Agents in Severe Asthma

Omalizumab

Mepolizumab

Benralizumab

Dupilumab

5. Limitations of the Study

- We aimed to span our knowledge of the security profile of these approved drugs, avoiding as much as possible the bias resulting from an underlying condition.

- The biologic drug indication data are often sparsely documented. Studies focusing solely on indication may overlook a significant number of reports, potentially up to 70% in some cases) [94]. However, studies utilizing that approach failed to identify any ADR that were not already described in the present investigation. We interpret this finding as supportive evidence for our approach.

- All the elucidated facts highlight the necessity for this type of data to be routinely included by any professional in their reporting.

6. Conclusions and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

FEDRA database of the Spanish System of Pharmacovigilance of Human Medicines (SEFV-H) disclaimer

References

- Global Initiative for Asthma. Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention. 2023 [Internet]. https://ginasthma.org/.

- Ferkol T, Schraufnagel D. The Global Burden of Respiratory Disease. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014 March;11(3):404-6. [CrossRef]

- Price D, Fletcher M, van der Molen T. Asthma control and management in 8,000 European patients: the REcognise Asthma and LInk to Symptoms and Experience (REALISE) survey. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2014 June 12th d;24:14009. [CrossRef]

- Levy ML. The national review of asthma deaths: what did we learn and what needs to change? Breathe Sheff Engl. 2005 March;11(1):14-24.

- Sadatsafavi M, Rousseau R, Chen W, Zhang W, Lynd L, FitzGerald JM. The preventable burden of productivity loss due to suboptimal asthma control: a population-based study. Chest. 2014 April;145(4):787-93.

- Rogliani P, Calzetta L, Matera MG, Laitano R, Ritondo BL, Hanania NA, et al. Severe Asthma and Biological Therapy: When, Which, and for Whom. Pulm Ther. 2020 June;6(1):47-66. [CrossRef]

- Habib N, Pasha MA, Tang DD. Current Understanding of Asthma Pathogenesis and Biomarkers. Cells. 2022 September 5th;11(17):2764. [CrossRef]

- Anderson GP. Endotyping asthma: new insights into key pathogenic mechanisms in a complex, heterogeneous disease. Lancet Lond Engl. 2008 September 20th;372(9643):1107-19. [CrossRef]

- Kuruvilla ME, Lee FEH, Lee GB. Understanding Asthma Phenotypes, Endotypes, and Mechanisms of Disease. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2019 April;56(2):219-33. [CrossRef]

- Ray A, Camiolo M, Fitzpatrick A, Gauthier M, Wenzel SE. Are We Meeting the Promise of Endotypes and Precision Medicine in Asthma? Physiol Rev. 2020 July 1st;100(3):983-1017.

- McDowell PJ, Heaney LG. Different endotypes and phenotypes drive the heterogeneity in severe asthma. Allergy. 2020 February;75(2):302-10. [CrossRef]

- Espuela-Ortiz A, Martin-Gonzalez E, Poza-Guedes P, González-Pérez R, Herrera-Luis E. Genomics of Treatable Traits in Asthma. Genes. 2023 September 20th;14(9):1824. [CrossRef]

- Sze E, Bhalla A, Nair P. Mechanisms and therapeutic strategies for non-T2 asthma. Allergy. 2020 February;75(2):311-25. [CrossRef]

- Kim SR. Next-Generation Therapeutic Approaches for Uncontrolled Asthma: Insights Into the Heterogeneity of Non-Type 2 Inflammation. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2024;16(1):1.

- Xie Y, Abel PW, Casale TB, Tu Y. TH17 cells and corticosteroid insensitivity in severe asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2022 February;149(2):467-79. [CrossRef]

- Carr TF, Peters MC. Novel potential treatable traits in asthma: Where is the research taking us? J Allergy Clin Immunol Glob. 2022 May;1(2):27-36.

- Stokes JR, Casale TB. Characterization of asthma endotypes: implications for therapy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2016 August;117(2):121-5.

- Han YY, Zhang X, Wang J, Wang G, Oliver BG, Zhang HP, et al. Multidimensional Assessment of Asthma Identifies Clinically Relevant Phenotype Overlap: A Cross-Sectional Study. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract.2021 January ;9(1):349-362.e18. [CrossRef]

- Ricciardolo FLM, Guida G, Bertolini F, Di Stefano A, Carriero V. Phenotype overlap in the natural history of asthma. Eur Respir Rev. 2023 June 30th;32(168):220201. [CrossRef]

- Fouka E, Domvri K, Gkakou F, Alevizaki M, Steiropoulos P, Papakosta D, et al. Recent insights in the role of biomarkers in severe asthma management. Front Med. 2022;9:992565. [CrossRef]

- Fahy JV. Type 2 inflammation in asthma — present in most, absent in many. Nat Rev Immunol.2015 January;15(1):57-65.

- EMA medical terms simplifier [Internet]. 2023. www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/other/ema-medical-terms-simplifier_en.pdf.

- Lommatzsch M, Brusselle GG, Canonica GW, Jackson DJ, Nair P, Buhl R, et al. Disease-modifying anti-asthmatic drugs. Lancet Lond Engl. 2022 April 23th;399(10335):1664-8. [CrossRef]

- Farne HA, Wilson A, Milan S, Banchoff E, Yang F, Powell CV. Anti-IL-5 therapies for asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022 July 12th;7(7):CD010834.

- González-Pérez R, Poza-Guedes P, Mederos-Luis E, Sánchez-Machín I. Real-Life Performance of Mepolizumab in T2-High Severe Refractory Asthma with the Overlapping Eosinophilic-Allergic Phenotype. Biomedicines. 19 de octubre de 2022 October 19th;10(10):2635. [CrossRef]

- Papaioannou AI, Fouka E, Bartziokas K, Kallieri M, Vontetsianos A, Porpodis K, et al. Defining response to therapy with biologics in severe asthma: from global evaluation to super response and remission. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2023;17(6):481-93. [CrossRef]

- Thomas D, McDonald VM, Pavord ID, Gibson PG. Asthma remission: what is it and how can it be achieved? Eur Respir J. 2022 November;60(5):2102583.

- Humbert M, Beasley R, Ayres J, Slavin R, Hébert J, Bousquet J, et al. Benefits of omalizumab as add-on therapy in patients with severe persistent asthma who are inadequately controlled despite best available therapy (GINA 2002 step 4 treatment): INNOVATE. Allergy. 2005 March;60(3):309-16. [CrossRef]

- Chang TW. The pharmacological basis of anti-IgE therapy. Nat Biotechnol. febrero de 2000;18(2):157-62. [CrossRef]

- BIFIMED: Buscador de la Información sobre la situación de financiación de los medicamentos - Nomenclátor de ABRIL - 2024 [BIFIMED: Information Search Engine on the financing situation of medicines - Nomenclátor APRIL - 2024]. www.sanidad.gob.es/profesionales/medicamentos.do?metodo=verDetalle&cn=652563.

- McGregor MC, Krings JG, Nair P, Castro M. Role of Biologics in Asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019 February 15th;199(4):433-45.

- Corren J. New Targeted Therapies for Uncontrolled Asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. mayo de 2019;7(5):1394-403. [CrossRef]

- Nucala: EPAR - Product Information [Internet].www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/nucala-epar-product-information_en.pdf.

- Cinqaero : EPAR - Product Information [Internet].: www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/cinqaero-epar-product-information_en.pdf.

- Fasenra : EPAR - Product Information [Internet].https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/fasenra-epar-product-information_en.pdf.

- Informe de Posicionamiento Terapéutico de benralizumab (Fasenra®) como tratamiento adicional en el asma grave no controlada eosinofílica [Internet].: /www.aemps.gob.es/medicamentosUsoHumano/informesPublicos/docs/IPT-benralizumab-Fasenra-asma_EPOC.pdf.

- Tezspire : EPAR - Product Information [Internet]. www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/tezspire-epar-product-information_en.pdf.

- Dupixent : EPAR - Product Information [Internet]. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/search?f%5B0%5D=ema_search_entity_is_document%3ADocument&search_api_fulltext=Dupixent%3A%20EPAR%20-%20Product%20Information.

- Bavbek S, Pagani M, Alvarez-Cuesta E, Castells M, Dursun AB, Hamadi S, et al. Hypersensitivity reactions to biologicals: An EAACI position paper. Allergy. 2022 January;77(1):39-54. [CrossRef]

- Sitek A, Chiarella SE, Pongdee T. Hypersensitivity reactions to biologics used in the treatment of allergic diseases: clinical features, diagnosis and management. Front Allergy. 2023 August 11th;4:1219735. [CrossRef]

- Real Decreto 577/2013, de 26 de julio, por el que se regula la farmacovigilancia de medicamentos de uso humano. [Internet]. https://www.boe.es/buscar/doc.php?id=BOE-A-2013-8191.

- Bate A, Evans SJW. Quantitative signal detection using spontaneous ADR reporting. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2009 June;18(6):427-36. [CrossRef]

- Guideline on good pharmacovigilance practices (GVP) Module IX Addendum I – Methodological aspects of signal detection from spontaneous reports of suspected adverse reactions.

- Grupo de trabajo Guía de señales del SEFV-H. Guía de señales del SEFV-H. Draft version. 2024.

- Evans SJ, Waller PC, Davis S. Use of proportional reporting ratios (PRRs) for signal generation from spontaneous adverse drug reaction reports. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2001;10(6):483-6. [CrossRef]

- ANEXO-005 Normas para la correcta interpretación y utilización de los datos del Sistema Español de Farmacovigilancia Humana (SEFV-H) [ANNEX-005 Standards for the correct interpretation and use of data from the Spanish Human Pharmacovigilance System (SEFV-H)]. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/file:///C:/Users/cboada/Downloads/ANEXO_SEFV-H-005%20v1-%20Normas%20correcta%20interpretaci%C3%B3n%20y%20utilizaci%C3%B3n%20datos%20del%20SEFV-H.pdf.

- ANEXO-008 v1- Campos que no se pueden liberar desde FEDRA 3 a personas ajenas al SEFV-H.pdf. [ANNEX-008 v1- Fields that cannot be released from FEDRA 3 to people outside the SEFV-H.pdf.].

- González-Pérez R, Poza-Guedes P, Pineda F, Galán T, Mederos-Luis E, Abel-Fernández E, et al. Molecular Mapping of Allergen Exposome among Different Atopic Phenotypes. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 June 21st;24(13):10467. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Marcos L. Grand challenges in genetics and epidemiology of allergic diseases: from genome to exposome and back. Front Allergy. 2024 February 5th;5:1368259. [CrossRef]

- Frix AN, Heaney LG, Dahlén B, Mihaltan F, Sergejeva S, Popović-Grle S, et al. Heterogeneity in the use of biologics for severe asthma in Europe: a SHARP ERS study. ERJ Open Res. 2022 October;8(4):00273-2022.

- Casas-Maldonado, F, Álvarez-Gutiérrez, FJ, Blanco-Aparicio, M, Domingo-Ribas, C, Cisneros-Serrano, C, Soto-Campos, G, et al. Monoclonal antibody treatment for severe uncontrolled asthma in Spain: analytical map. J Asthma.2022 October 3rd;59(10):1997-2007. [CrossRef]

- Nixon R, Despiney R, Pfeffer P. Case of paradoxical adverse response to mepolizumab with mepolizumab-induced alopecia in severe eosinophilic asthma. BMJ Case Rep. 2020 February 20th;13(2):e233161. [CrossRef]

- Park S. Short communication: Comments on hair disorders associated with dupilumab based on VigiBase. PLoS One. 2022;17(7).

- Suzaki I, Tanaka A, Yanai R, Maruyama Y, Kamimura S, Hirano K, et al. Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis developed after dupilumab administration in patients with eosinophilic chronic rhinosinusitis and asthma: a case report. BMC Pulm Med.2023 April 19th;23(1):130. [CrossRef]

- Flanagan K, Sperling L, Lin J. Drug-induced alopecia after dupilumab therapy. JAAD Case Rep. 2019 January;5(1):54-6. [CrossRef]

- Agache I, Beltran J, Akdis C, Akdis M, Canelo-Aybar C, Canonica GW, et al. Efficacy and safety of treatment with biologicals (benralizumab, dupilumab, mepolizumab, omalizumab and reslizumab) for severe eosinophilic asthma. A systematic review for the EAACI Guidelines - recommendations on the use of biologicals in severe asthma. Allergy. 2020 May;75(5):1023-42.

- Casas-Maldonado F, Álvarez-Gutiérrez FJ, Blanco Aparicio M, Domingo Ribas C, Cisneros Serrano C, Soto Campos G, et al. Treatment Patterns of Monoclonal Antibodies in Patients With Severe Uncontrolled Asthma Treated by Pulmonologists in Spain. Open Respir Arch. 2023 July;5(3):100252. [CrossRef]

- Caminati M, Fassio A, Alberici F, Baldini C, Bello F, Cameli P, et al. Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis onset in severe asthma patients on monoclonal antibodies targeting type 2 inflammation: Report from the European EGPA study group. Allergy.2024 February;79(2):516-9. [CrossRef]

- Bachert C, Han JK, Desrosiers MY, Gevaert P, Heffler E, Hopkins C, et al. Efficacy and safety of benralizumab in chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps: A randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2022 April;149(4):1309-1317.e12. [CrossRef]

- Yonezawa H, Ohmura S ichiro, Ohkubo Y, Otsuki Y, Miyamoto T. New-onset of eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis without eosinophilia and eosinophilic infiltration under benralizumab treatment: A case report. Mod Rheumatol Case Rep. 29 de diciembre de 2023;8(1):145-9. [CrossRef]

- Caminati M, Menzella F, Guidolin L, Senna G. Targeting eosinophils: severe asthma and beyond. Drugs Context. 2019;8:212587. [CrossRef]

- Kai M, Vion PA, Boussouar S, Cacoub P, Saadoun D, Le Joncour A. Eosinophilic granulomatosis polyangiitis (EGPA) complicated with periaortitis, precipitating role of dupilumab? A case report a review of the literature. RMD Open. 2023 September;9(3):e003300. [CrossRef]

- Mota D, Rama TA, Severo M, Moreira A. Potential cancer risk with omalizumab? A disproportionality analysis of the WHO’s VigiBase pharmacovigilance database. Allergy.2021 October;76(10):3209-11.

- Ferastraoaru D, Gross R, Rosenstreich D. Increased malignancy incidence in IgE deficient patients not due to concomitant Common Variable Immunodeficiency. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2017 September;119(3):267-73. [CrossRef]

- Ferastraoaru D, Rosenstreich D. IgE deficiency and prior diagnosis of malignancy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 018 November;121(5):613-8. [CrossRef]

- Bagnasco D, Canevari RF, Del Giacco S, Ferrucci S, Pigatto P, Castelnuovo P, et al. Omalizumab and cancer risk: Current evidence in allergic asthma, chronic urticaria, and chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. World Allergy Organ J. 2022 December;15(12):100721. [CrossRef]

- Jackson K, Bahna SL. Hypersensitivity and adverse reactions to biologics for asthma and allergic diseases. Expert Rev Clin Immunol.2020 March 3rd;16(3):311-9. [CrossRef]

- FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA approves label changes for asthma drug Xolair (omalizumab), including describing slightly higher risk of heart and brain adverse events [Internet]. 2014. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-drug-safety-communication-fda-approves-label-changes-asthma-drug-xolair-omalizumab-including.

- Iribarren C, Rahmaoui A, Long AA, Szefler SJ, Bradley MS, Carrigan G, et al. Cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events among patients receiving omalizumab: Results from EXCELS, a prospective cohort study in moderate to severe asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017 May;139(5):1489-1495.e5. [CrossRef]

- Oblitas CM, Galeano-Valle F, Vela-De La Cruz L, Del Toro-Cervera J, Demelo-Rodríguez P. Omalizumab as a Provoking Factor for Venous Thromboembolism. Drug Target Insights. 2019;13:1177392819861987.

- Satake Y, Sakai S, Takao T, Saeki T. A case of subarachnoid associated with MPO-ANCA-positive eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, successfully treated with glucocorticoid, cyclophosphamide, and mepolizumab. Mod Rheumatol Case Rep.2023 December 8th;rxad071.

- Mutoh T, Shirai T, Sato H, Fujii H, Ishii T, Harigae H. Multi-targeted therapy for refractory eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis characterized by intracerebral hemorrhage and cardiomyopathy: a case-based review. Rheumatol Int. 2022 November;42(11):2069-76. [CrossRef]

- Park HT, Park S, Jung YW, Choi SA. Is Omalizumab Related to Ear and Labyrinth Disorders? A Disproportionality Analysis Based on a Global Pharmacovigilance Database. Diagn Basel Switz. 8 de octubre de 2022 October 8th;12(10):2434. [CrossRef]

- Namazy JA, Blais L, Andrews EB, Scheuerle AE, Cabana MD, Thorp JM, et al. Pregnancy outcomes in the omalizumab pregnancy registry and a disease-matched comparator cohort. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020 February;145(2):528-536.e1. [CrossRef]

- Sitek AN, Li JT, Pongdee T. Risks and safety of biologics: A practical guide for allergists. World Allergy Organ J. 2023 January;16(1):100737. [CrossRef]

- Khurana S, Brusselle GG, Bel EH, FitzGerald JM, Masoli M, Korn S, et al. Long-term Safety and Clinical Benefit of Mepolizumab in Patients With the Most Severe Eosinophilic Asthma: The COSMEX Study. Clin Ther. 2019 October;41(10):2041-2056.e5. [CrossRef]

- Jackson DJ, Korn S, Mathur SK, Barker P, Meka VG, Martin UJ, et al. Safety of Eosinophil-Depleting Therapy for Severe, Eosinophilic Asthma: Focus on Benralizumab. Drug Saf. 2020 May;43(5):409-25. [CrossRef]

- Morikawa K, Toyoshima M, Koda K, Kamiya Y, Suda T. Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia after withdrawal of systemic corticosteroids for chronic eosinophilic pneumonia and severe asthma under benralizumab treatment. Respir Investig. 2024 March;62(2):231-3. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka A, Fujimura Y, Fuke S, Izumi K, Ujiie H. A case of bullous pemphigoid developing under treatment with benralizumab for bronchial asthma. J Dermatol. 2023 September;50(9):1199-202. [CrossRef]

- Akenroye A, Lassiter G, Jackson JW, Keet C, Segal J, Alexander GC, et al. Comparative efficacy of mepolizumab, benralizumab, and dupilumab in eosinophilic asthma: A Bayesian network meta-analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2022 November;150(5):1097-1105.e12.

- Korn S, Bourdin A, Chupp G, Cosio BG, Arbetter D, Shah M, et al. Integrated Safety and Efficacy Among Patients Receiving Benralizumab for Up to 5 Years. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021 December;9(12):4381-4392.e4. [CrossRef]

- Kavanagh JE, Hearn AP, Dhariwal J, d’Ancona G, Douiri A, Roxas C, et al. Real-World Effectiveness of Benralizumab in Severe Eosinophilic Asthma. Chest. 2021 February;159(2):496-506.

- Mishra AK, Sahu KK, James A. Disseminated herpes zoster following treatment with benralizumab. Clin Respir J. 2019 March;13(3):189-91. [CrossRef]

- Jackson DJ, Pavord ID. Living without eosinophils: evidence from mouse and man. Eur Respir J.2023 January;61(1):2201217. [CrossRef]

- Bylund S, Kobyletzki L, Svalstedt M, Svensson A. Prevalence and Incidence of Atopic Dermatitis: A Systematic Review. Acta Derm Venereol. 2020;100(12):adv00160. [CrossRef]

- Akinlade B, Guttman-Yassky E, de Bruin-Weller M, Simpson EL, Blauvelt A, Cork MJ, et al. Conjunctivitis in dupilumab clinical trials. Br J Dermatol. 2019 September;181(3):459-73.

- De Bruin-Weller M, Thaçi D, Smith CH, Reich K, Cork MJ, Radin A, et al. Dupilumab with concomitant topical corticosteroid treatment in adults with atopic dermatitis with an inadequate response or intolerance to ciclosporin A or when this treatment is medically inadvisable: a placebo-controlled, randomized phase III clinical t. Br J Dermatol.2018 May;178(5):1083-101.

- Blauvelt A, Teixeira HD, Simpson EL, Costanzo A, De Bruin-Weller M, Barbarot S, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Upadacitinib vs Dupilumab in Adults With Moderate-to-Severe Atopic Dermatitis: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2021 September 1st;157(9):1047-55.

- Sachdeva M. Alopecia areata related paradoxical reactions in patients on dupilumab therapy: a systematic review. J Cutan Med Surg. 2021;25(4):451-2. [CrossRef]

- Beaziz J, Bouaziz JD. Dupilumab-induced psoriasis and alopecia areata: case report and review of the literature. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2021;148(3):198-201. [CrossRef]

- Johansson EK, Ivert LU, Bradley B, Lundqvist M, Bradley M. Weight gain in patients with severe atopic dermatitis treated with dupilumab: a cohort study. BMC Dermatol. 2020 September 22th;20(1):8. [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Gonzalez C, Lopez-Gonzalez E, Herdeiro MT, Figueiras A. Strategies to improve adverse drug reaction reporting: a critical and systematic review. Drug Saf. 2013 May;36(5):317-28. [CrossRef]

- Avedillo-Salas A, Pueyo-Val J, Fanlo-Villacampa A, Navarro-Pemán C, Lanuza-Giménez FJ, Ioakeim-Skoufa I, et al. Prescribed Drugs and Self-Directed Violence: A Descriptive Study in the Spanish Pharmacovigilance Database. Pharmaceuticals.2023 May 22th;16(5):772. [CrossRef]

- Cutroneo PM, Arzenton E, Furci F, Scapini F, Bulzomì M, Luxi N, et al. Safety of Biological Therapies for Severe Asthma: An Analysis of Suspected Adverse Reactions Reported in the WHO Pharmacovigilance Database. BioDrugs Clin Immunother Biopharm Gene Ther. 2024 March 15th; [CrossRef]

| Biological Drugs (Date of Approval) |

ATC – GTER Classification | Approved Indications | Brand Name |

|---|---|---|---|

| Omalizumab (10/25/2005) |

R03DX05 -Other systemic drugs for obstructive airway diseases | Allergic asthma convincingly mediated by IgE | Xolair® |

| Mepolizumab (12/02/2015) |

R03DX09 | Severe refractory eosinophilic asthma Chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis Hypereosinophilic syndrome |

Nucala® |

| Reslizumab (05/15/2016) |

R03DX08 | Insufficiently controlled severe eosinophilic asthma | Cinqaero® ▼ |

| Benralizumab (02/12/2018) |

R03DX10 | Severe uncontrolled eosinophilic asthma | Fasenra® |

| Tezepelumab (09/19/2022) |

R03DX11 | Severe asthma | Tezspire® ▼ |

| Dupilumab (09/26/2017) |

D11AH -Agents for dermatitis, excluding corticosteroids | Moderate to severe atopic dermatitis Severe uncontrolled eosinophilic asthma Chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps Prurigo nodularis Eosinophilic esophagitis |

Dupixent® |

| Origin of Cases (n) | Non-Serious n (%) |

Serious* n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| SEFV-H (361) | 154 (43 %) | 207 (57 %) |

| MAH (1,985) | 1,506 (76 %) | 479 (24 %) |

| Unknown | Mortal | Not Recovered | Recovered with after-Effects | In Recovery | Recovered | Origin of Cases (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 17 % | 1 % | 16 % | 2 % | 25 % | 40 % | SEFV-H (361) |

| 43 % | 1 % | 22 % | 0,4 % | 8 % | 25 % | MAH (1,985) |

| Biological Drug | FEDRA (n) | Serious* Cases | Males | Females | Warning** Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Omalizumab | 672 | 61% | 27% | 65% | 10,1% |

| Mepolizumab | 497 | 32% | 24% | 66% | 3,6% |

| Reslizumab | 35 | 54% | 17% | 74% | 17% |

| Benralizumab | 588 | 18% | 23% | 75% | 2,2% |

| Tezepelumab | 3 | 33% | 33% | 66% | - |

| Dupilumab | 536 | 29% | 47% | 45% | 5,6% |

| Symptoms grouping | Omalizumab | Mepolizumab | Reslizumab | Benralizumab | Tezepelumab | Dupilumab |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood and lymphatic system disorders | Idiopathic thrombocytopenia | Eosinophilia | ||||

| Eye disorders | Allergic conjunctivitis. Keratitis Blepharitis Eye pruritus Dry eye Ulcerative keratitis |

|||||

| Gastrointestinal disorders | Upper abdominal pain | Upper abdominal pain | ||||

| General disorders and administration site conditions | Pyrexia Injection site reactions: swelling erythema, pain, and pruritus Influenza-like illness Swelling arms Weight increase Fatigue |

Pyrexia Injection site reactions Systemic non allergic administration- related reactions |

Pyrexia Injection site reactions |

Injection site reactions |

Injection site reactions: swelling, oedema, erythema, pain, hematoma, and pruritus |

|

| Immune system disorders | Anaphylactic reaction and other serious allergic conditions. Anti-omalizumab antibody development Serum sickness, may include fever lymphadenopathy |

Anaphylactic reaction and other serious allergic conditions |

Anaphylactic reaction | Anaphylactic reaction Hypersensitivity reactions |

Anaphylactic reaction and other serious allergic conditions | Anaphylactic reaction Angioedema Serum sickness |

| Infections and infestations | Pharyngitis Parasitic infection |

Pharyngitis Lower respiratory tract infection Urinary tract infections |

Pharyngitis | Pharyngitis | Conjunctivitis Oral herpes |

|

| Investigations | Blood creatine phosphokinase increased | |||||

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | Myalgia Arthralgia Joint swelling Systemic lupus erythematosus |

Myalgia Back pain |

Myalgia |

Arthralgia |

Arthralgia |

|

| Nervous system disorders | Headache Syncope Paresthesia Somnolence Dizziness |

Headache | Headache | |||

| Respiratory, thoracic, and mediastinal disorders | Allergic bronchospasm Coughing Laryngoedema Allergic granulomatous vasculitis |

Nasal congestion | ||||

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders | Photosensitivity Urticaria, Rash Pruritus Alopecia |

Eczema, Rash |

Rash |

Rash |

||

| Vascular disorders | Flushing Postural hypotension |

Flushing |

| Omalizumab | Mepolizumab | Reslizumab | Benralizumab | Dupilumab | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood and lymphatic system disorders | Anemic disorders Lymphadenopathy |

Lymphadenopathy |

|||

| Cardiac disorders |

Acute myocardial infarction Pericarditis |

Ischemic coronary artery disorders | |||

| Ear and labyrinth disorders |

Deafness Deafness. neurosensory |

||||

| Eye disorders | Eyelid oedema | ||||

| Gastrointestinal disorders | Abdominal pain or discomfort | Vomiting and nausea Diarrhea Crohn's disease |

|||

| General disorders and administration site conditions | Asthenic conditions |

|

Asthenia or Fatigue | Asthenia or Fatigue Pyrexia Malaise |

|

| Immune system disorders |

Multiple Sclerosis Sjögren Syndrome |

||||

| Infections and infestations |

Herpes viral infect. Lung and lower resp. tract infection |

Herpes viral infect* |

Pneumonia |

Infective Pneumonia Cellulitis |

|

| Metabolism and nutrition disorders | Decreased appetite Decreased weight |

Decreased appetite Decreased weight |

|||

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | Back pain Muscular weakness Muscle spasms Musculoskeletal stiffness |

Arthralgia* |

Arthralgia |

Arthralgia Myalgia Muscle spasms |

Myalgia Bone pain Limb pain |

| Neoplasms benign, malignant, and unspecified (incl cysts and polyps) |

Breast and nipple neoplasm malignant Lymphomas unspecified Colorectal neoplasm malignant Respiratory tract neoplasm malignant cell type unspecified. |

Breast and nipple neoplasm malignant Breast cancer male Malignant neo.GI NEC Respiratory tract neoplasm malignant cell type unspecified. |

Glial tumors malignant |

Malignant neo.GI NEC Malignant Respiratory neoplasm |

|

| Nervous system disorders |

Vascular disorders CNS Gait disturbance, Gait inability, Mobility decreased and Hypokinesia Optic neuritis |

Cerebrovascular accident Paraesthesias, Dysaesthesias Hypoaesthesias Tremor |

Headaches Dizziness Syncope |

||

| Pregnancy, puerperium, and perinatal conditions | Abortion spontaneous | ||||

| Psychiatric disorders | Anxiety | Sleep disorders | Anxiety, Stress and Nervousness | ||

| Reproductive system and breast disorders | Menstrual cycle disorders | . | |||

| Respiratory, thoracic, and mediastinal disorders | Pulmonary embolism and thrombosis | Pulmonary embolism and thrombosis | Pulmonary embolism and thrombosis | Eosinophilic Pneumonia |

|

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders |

Atopic dermatitis Purpura Hyperhidrosis |

Alopecia |

Alopecia | Alopecia | Alopecia |

| Vascular disorders | Deep Vein Thrombosis | Deep Vein Thrombosis | Hypertension Hypotension |

Vasculitis |

| Association | N | Lower Limit ROR* | Lower Limit CI^ | X2` |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Omalizumab-Acute myocardial infarction (PT: acute myocardial infarction, acute coronary syndrome, Kounis´ syndrome) |

6 | 1.48 | 0.23 | 9.25 |

| Omalizumab-Angina pectoris (PT) | 4 | 2.97 | 0.45 | 23.05 |

| Omalizumab-Pericarditis (PT: pericarditis; pleuropericarditis) | 4 | 2.86 | 0.43 | 21.95 |

| Omalizumab-Deafness (PT: deafness; neurosensorial deafness) | 4 | 3.69 | 0.54 | 30.19 |

| Omalizumab-Multiple Sclerosis (PT) | 3 | 2.75 | 0.13 | 18.45 |

| Omalizumab-Sjögren Syndrome (PT) | 3 | 15.15 | 0.42 | 122.99 |

| Omalizumab-Optic Neuritis (PT) | 3 | 3.28 | 0.19 | 22.95 |

| Omalizumab-Herpes viral infection (PT: oral herpes, herpes zoster, eczema herpeticum, herpes virus infections.) |

8 | 1.10 | 0.00 | 5.7 |

| Omalizumab-Muscular weakness; Back pain; Muscle spasms; Joint stiffness. (PTs) | 18 | 1.11 | 0.09 | 5.85 |

| Omalizumab-Breast and nipple neoplasm malignant (PTs: hormone receptor-positive breast cancer, breast cancer, invasive lobular breast carcinoma, invasive breast carcinoma, invasive ductal breast cancer) |

16 |

23.33 | 2.84 | 540.78 |

| Omalizumab-Colon cancer (PT) | 7 | 12.49 | 1.62 | 162.52 |

| Omalizumab-Lymphoma (PT) | 4 | 1.64 | 0.10 | 9.78 |

| Omalizumab-Lung adenocarcinoma, Lung malignant neoplasm (PTs) | 7 | 8.27 | 1.48 | 104.16 |

| Omalizumab-Cerebrovascular accident, Ischemic stroke, Transient ischemic attack (PTs) | 8 | 2.48 | 0.82 | 24.74 |

| Omalizumab-Gait disturbance, Gait inability, Mobility decreased and Hypokinesia (PTs) | 8 | 1.44 | 0.29 | 9.54 |

| Omalizumab-Abortion spontaneous, gestational fetal death (PTs) | 8 | 4.05 | 1.21 | 48.52 |

| Omalizumab-Atopic dermatitis (PT) | 4 | 8.06 | 0.77 | 73.97 |

| Omalizumab-Deep Vein Thrombosis (PT) | 5 | 1.47 | 0.14 | 8.71 |

| Omalizumab-Embolic and thrombotic events (SMQ) | 25 | 1.51 | 0.50 | 16.69 |

| Mepolizumab-Arthralgia (PT)** | 27 | 2.22 | 0.95 | 39.15 |

| Mepolizumab-Herpes zoster (PT)** | 6 | 2.42 | 0.63 | 20.81 |

| Mepolizumab-Breast and nipple neoplasm. malignant (HLT) Breast malignant tumors (SMQ) |

3 | 5.36 | 0.32 | 40.85 |

| Mepolizumab-Gastrointestinal neoplasms malignant and unspecified (HLGT) | 4 | 5.41 | 0.67 | 47.55 |

| Mepolizumab-Respiratory and mediastinal neoplasms malignant and unspecified (HLGT) | 3 | 5.98 | 0.34 | 46.21 |

| Mepolizumab-Malignancies (SMQ) | 16 | 2.86 | 1.19 | 44.32 |

| Mepolizumab-Alopecia (PT) | 8 | 3.88 | 1.17 | 45.66 |

| Reslizumab-Arthralgia (PT) | 10 | 6.28 | 1.42 | 77.96 |

| Benralizumab-Alopecia (PT) | 4 | 2.68 | 0.38 | 20.05 |

| Dupilumab-Crohn's disease (PT) | 3 | 3.67 | 0.22 | 26.23 |

| Dupilumab-Infective Pneumonia (SMQ) [excluded COVID-19] | 7 | 1.92 | 0.52 | 15.47 |

| Dupilumab-Bone pain (PT) | 4 | 2.02 | 0.23 | 13.52 |

| Dupilumab-Alopecia (PT) | 15 | 5.00 | 1.76 | 92.92 |

| Present in SmPC | Present in Reports | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Omalizumab | Arthralgia | Myalgia | Arthralgia | Myalgia |

| Mepolizumab | Arthralgia | Myalgia | Arthralgia | Myalgia |

| Dupilumab | Arthralgia | Arthralgia | Myalgia | |

| Tezepelumab | Arthralgia | Arthralgia | Myalgia | |

| Reslizumab | Myalgia | Arthralgia | Myalgia | |

| Benralizumab | Arthralgia | Myalgia | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).