1. Introduction

Natural Killer (NK) cells represent a highly specialized subpopulation of lymphoid cells (5-15%), integral to the innate immune system [

1]. These cells provide early immunoregulatory cytokines and tumor cell lysis without previous stimulation, crucial for immunological surveillance and tumor suppression. The surface antigens CD56 and CD16 antigens allow the characterization of NK cells and categorize them as regulatory and cytotoxic, depending on their expression levels [

2].

Approximately 90% of human NK cells in peripheral blood are cytotoxic, with low expression of CD56 (CD56dim/-) and high levels of the Fcγ receptor III (FcγRIII, CD16bright), while 10% are immunoregulatory, which are CD56brightCD16dim or CD16-. Of these two subpopulations, CD56dimCD16bright cells have greater cytotoxic activity, while CD56brightCD16dim favor the synthesis of inflammatory cytokines [

2,

3].

NK cells express numerous receptors on their membrane, which mediate different signals for the activation of their immune activity against infections and tumor cells. Since NK cells do not have clonal receptors, their repertoire is conformed of germline receptors, which have traditionally been classified as activating receptors (trigger the function of the NK cells) and inhibitory receptors (those that regulate the signal delivered by activating receptors and prevent NK cell activation) [

2]. In addition, NK cells express pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), such as Toll-like receptors, through which they recognize pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) as well as damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) [

4].

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) constitutes 80% of all leukemias in children [

5]. Even though the survival of patients with ALL has increased remarkably, 20% of patients are still resistant to treatment [

6]. NK cells play a central role in identifying and eradicating leukemia cells [

7,

8] however, studies have reported that peripheral blood NK cells exhibit compromised cytotoxicity towards autologous blasts [

9,

10] with altered cell surface expression of inhibitory receptors (NKp46 and NKG2A) compared to age-matched healthy control subjects [

11,

12]. Therefore, the discovery that TLRs are also expressed in NK cells has increased the interest in their immune response against tumor cells.

TLRs constitute a family of transmembrane proteins, that recognize specific molecular patterns from microorganisms, as well as endogenous ligands that produce inflammatory responses [

13]. Of the 11 TLRs recognized in humans, 10 are expressed as proteins, with TLRs 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, and 10 expressed on the cell membrane and recognizing mainly microbial components such as LPS, proteins, and lipoproteins [

14], while TLRs 3, 7, 8, and 9 are mainly expressed in endosomes where they recognize nucleic acid components such as double-stranded RNA (dsRNA), single-stranded RNA (ssRNA), and unmethylated CpG DNA motifs [

15,

16,

17]. TLR11 is considered a pseudogene [

18].The binding of TLRs to their corresponding ligand triggers a signaling pathway leading to the activation of the immune response for the elimination of pathogens [

19,

20,

21].

It has been described that NK cells express endosomal TLRs [

22]; however, even though there is evidence of the direct activation of NK cell functions through these TLRs, this activation was evaluated in healthy donors NK cells and also discovered that can only occur by the complex interaction with other cells of the immune system and the microenvironment [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]. Although different preclinical studies have shown effective activation of donor NK cells with TLR ligands to induce blast lysis [

28,

29,

30], the effects of this activation in the context of hematological disorders, such as ALL, remains unknown [

31]. Since NK cells are important for effective tumor suppression demonstrating that the activation of this cells from hematological oncological disorders are possible, would provide a new panorama for the development of antitumoral therapies.

Previously in our work group, Sánchez et al. demonstrated that the NK cells from ALL pediatric patients (bone marrow and peripheral blood), express all the endosomal TLRs (TLR3, TLR7, TLR8 and TLR9) [

22] therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate the response of the different subpopulations of human NK cells from pediatric ALL patients to stimulation through their different endosomal TLRs using synthetic TLR agonists and compare this response with those from unstimulated human NK cells from pediatric ALL patients in order to evaluate the feasibility of inducing NK cell activation as a first approach as a possible adjuvant in antitumor immunotherapy.

3. Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate the response of NK cell subpopulations from pediatric patients with ALL to endosomal TLR and compare them with those from the unstimulated NK cells with the objective of identifying the most suitable molecule(s) with potential as adjuvants in combination with cancer immunotherapy. We show that the agonists poly I:C, imiquimod, R848, and ODN2006 increase the function of NK cells, with R848 and ODN increasing the cytotoxicity. In addition, our study showed that the most sensitive NK subpopulation was the CD56+CD16-, which is considered mainly immunoregulatory, suggesting that this subpopulation may be also contributing to blast lysis.

Existing studies have shown that only NK cells derived from healthy donors or solid tumors can be directly activated by TLR agonist stimuli, increasing their immunoregulatory and cytotoxic activities [

32,

33], leaving uncertainties about the response patterns in hematological malignancies. This is the first study to assess the response of different NK subpopulations from ALL patients when are stimulated with TLR´s ligands, offering insight into the functional characteristics of NK cells in this context.

In cancer situations, including ALL, exposure to tumor cells and the tumor microenvironment components hinders NK cell functions, rendering them dysfunctional [

9,

34]. Hence we assessed the behavior of NK cells following stimulation in both PBMCs and in isolation in order to discern whether the NK cells from our patients exhibited a consistent response to stimuli both within their natural microenvironment and when isolated.

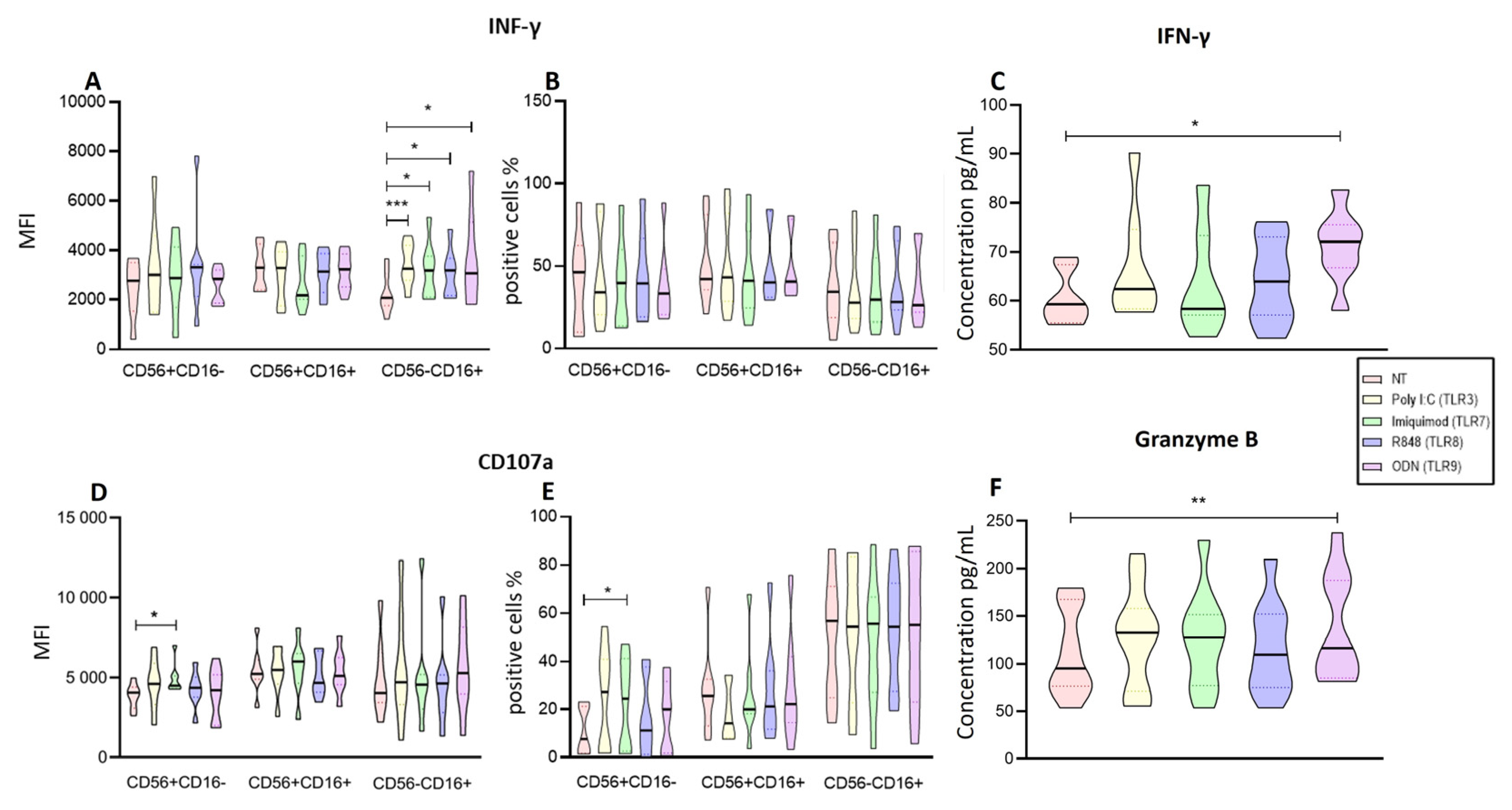

The first result of our study is that Poly I:C (TLR3) and R848 (TLR8) gives the strongest signal upregulating NK-cell functions within the PBMCs. We found that the IFN-γ positive cells of CD56+CD16- increased by both R848 and Poly I:C in NK cells. Meanwhile, we found that the four ligands upregulated the IFN-γ production of CD56-CD16+ subpopulation on isolated NK cells. These results are in agreement with the evidence that TLR agonists can increase production of IFN-γ by NK cells [

35]

Other characteristic of functional NK cells is the release of the cytotoxic granules this degranulation is measured by the expression CD107a. In our study, we observed that Poly I:C, ODN, and R848 increased NK cells CD107 expression within the PBMCs, and the percent of CD56+CD16- and CD56+CD16+ subpopulations. On the other hand, the results on isolated NK cells showed that Imiquimod (TLR7) modified the expression and proportion of cells expressing CD107a for CD56+CD16- [

36,

37]

The difference between the PBMC and isolated NK cells on the TLRs increasing their functions suggest that the activation of the PBMC by the TLR ligands may have an adding effect on the NK cells.

To further evaluate the degranulation on the isolated NK cells, we evaluated the concentration of Granzyme B on the supernatant, for this enzyme is one contained in the cytotoxic granules of NK cells. [

38] We observed that ODN was the one which stimulated the secretion of Granzyme B from these cells, this in odds with our finding regarding the expression of CD107a which increased with Imiquimod therefore, this shoud be further studied to fully understand the phenomenon.

It has been suggested that TLR7/8 activation promotes tumors by inducing robust pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion and activating NK at the tumor site [

39]. IL-1β and IL-2 have been suggested as a ptent co-stimulus for IFN-γ production by the immunoregulatory NK cells [

40,

41]. TNF-α, IFN-γ, and CXCL8 are produced by NK cell and also enhance their activation and recruitment [

42,

43]. Concordantly, we observed that R848 increased these proinflammatory cytokines on the supernatant of PBMCs. These results suggest that monocytes, T cells, and dendritic cells are being stimulated and subsequently may promote the activation of NK cells which could explain the increase in IFN-γ and CD107a observed on the CD56+CD16- subpopulation.

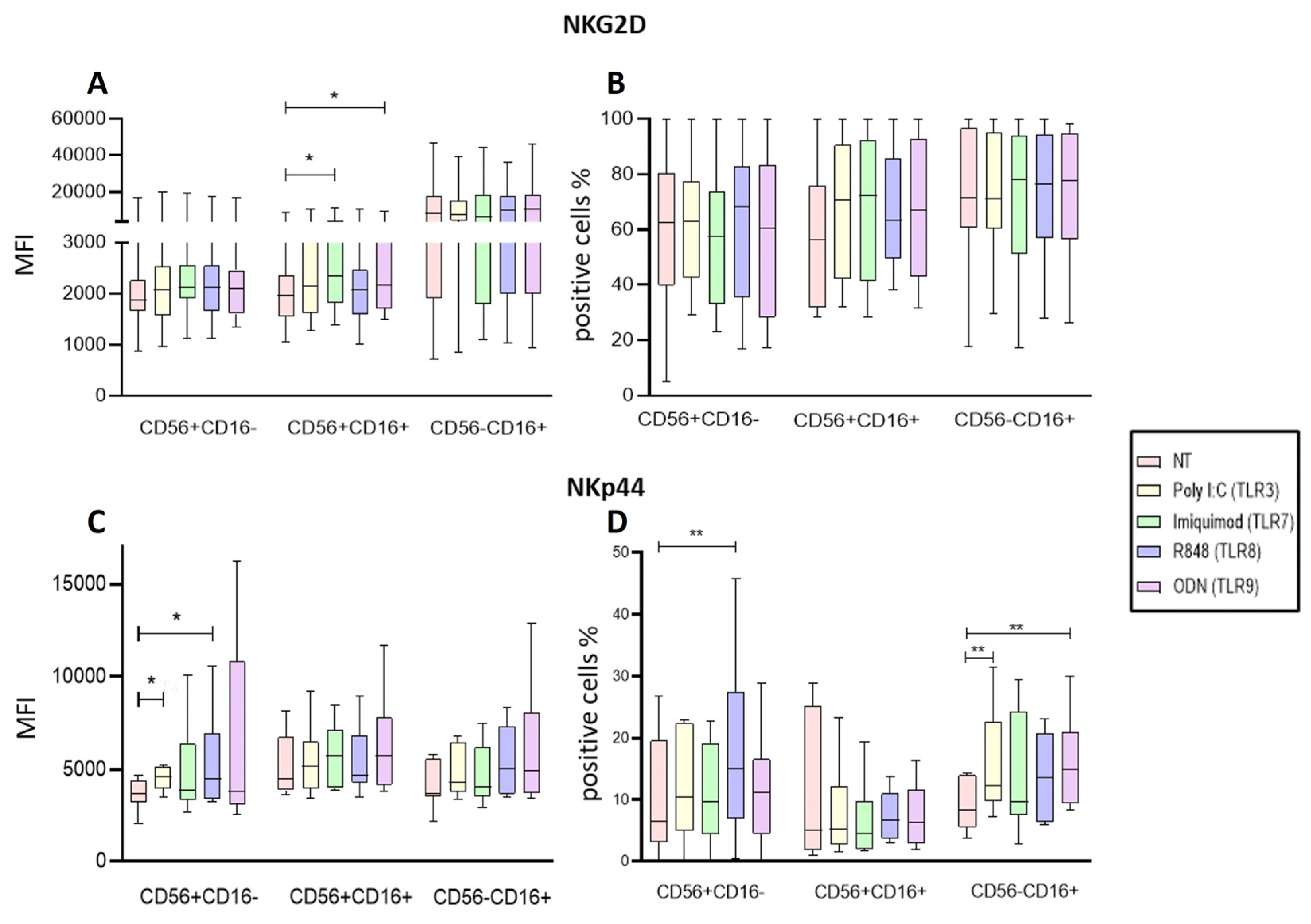

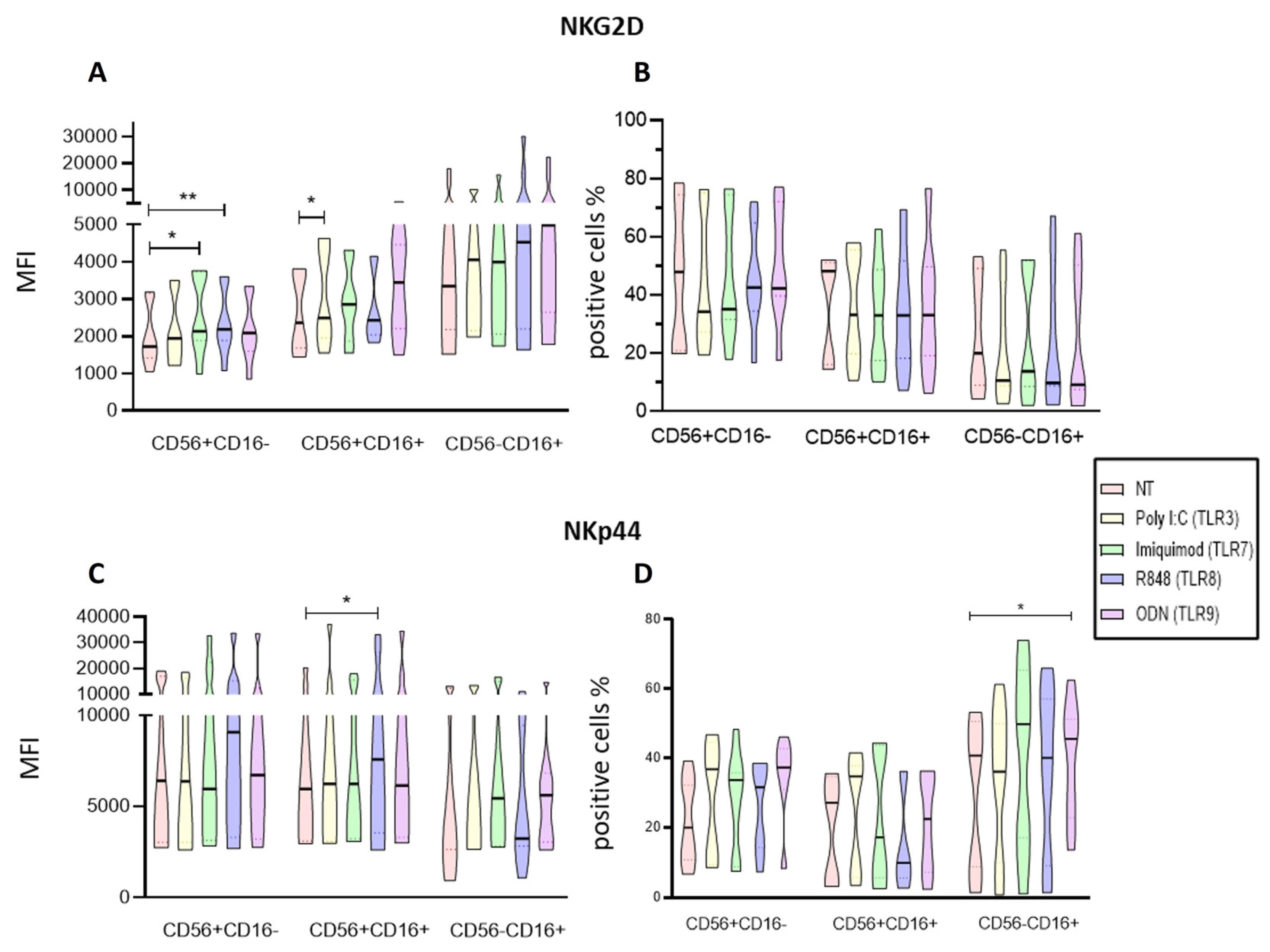

Regarding the density of activating receptors in NK cells from ALL patients our findings that Imiquimod and ODN increased the expression of the NKG2D in the CD56+CD16+ subpopulation of the PBMCs suggests that this ligands may help the NK cells to undergo a polarization towards an activated state while on the isolated NK cells Imiquimod and R848 increased the expression of NKG2D on the CD56+CD16- subpopulation and Poly I:C on the CD56+CD16+ subpopulation. Our results agree with what Girart et al. stated about the increase of NKG2D expression after stimulation through TLR7 [

44].

The other receptor, NKp44 is associated with an activated state of the NK cells [

45]. Our results show that Poly I:C, and the R848 significantly increased the expression of this receptor and the proportion of the CD56+CD16- subpopulation while Poly I:C and ODN2006 increased the proportion of NKp44 expressing cells in the CD56-CD16+ cytotoxic population of the PBMCs. Regarding the isolated NK cells, R848 increased the proportion of CD56+CD16+ cells expressing NKp44, and ODN increased the expression of NKp44 on the CD56-CD16+ subpopulation. Taking these results together, they suggest that the Poly I:C, R848 and OD2006 ligands (TLR3, TLR8, and TLR9 respectively) promote an activated status on the NK cells.

The different response to TLR of the NK cells embedded in PBMC versus the isolated NK cells in our study, confirm the microenvironment cells influence on NK responses in addition to the TLR stimulation [

34] and should be further evaluated. However, in both aspects CD56+CD16- was the most sensible to the stimulation, suggesting that this subpopulation could be less impaired and its potential for a therapeutic approach should be further analyze.

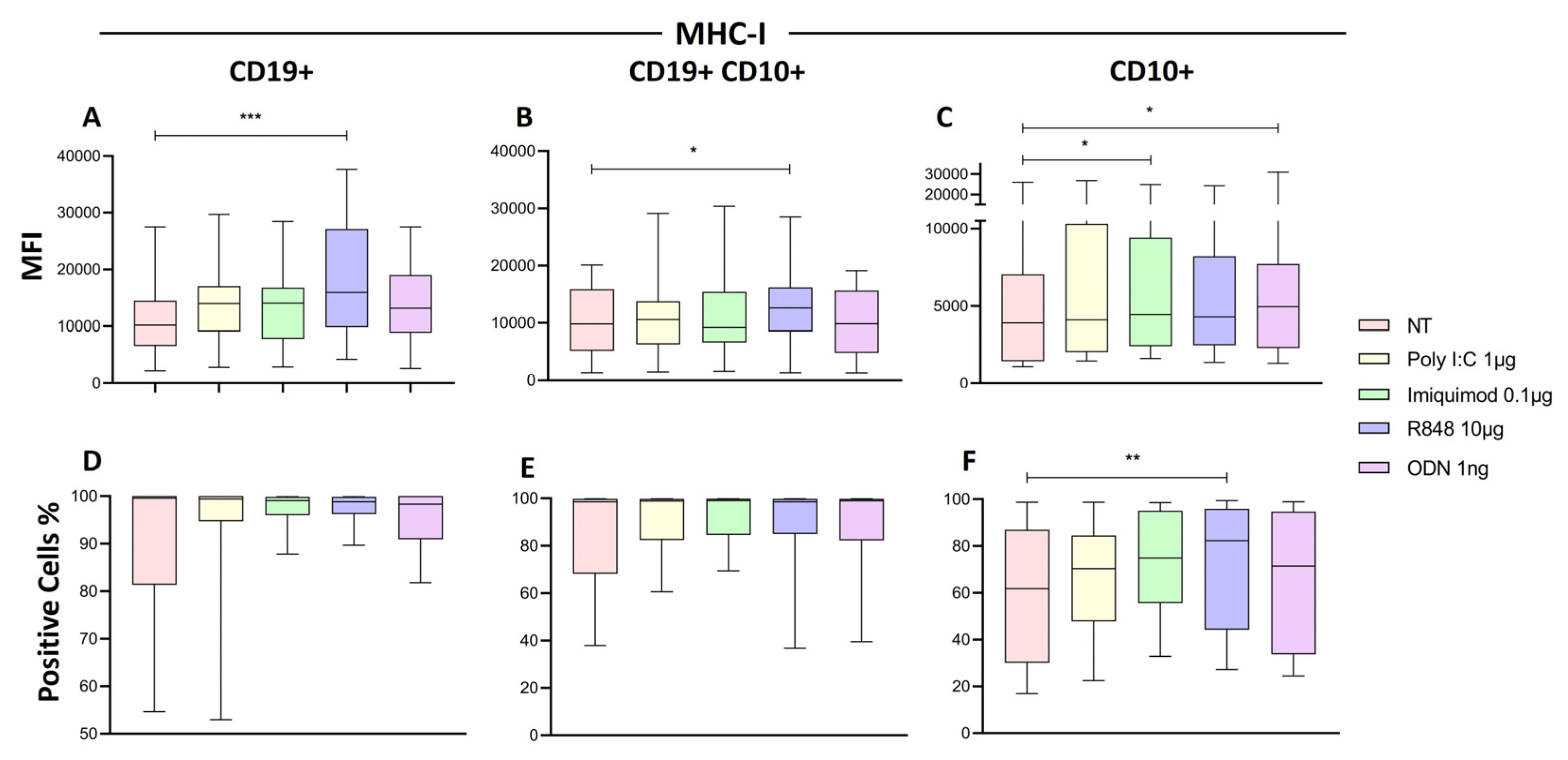

Some HLA-I molecules may play a role as ligands for activating NK receptors, such as NKG2D [

44]. The stimulation with the TLR8 ligand (R848) significantly increased the expression of HLA-I on the CD19+ B lymphocytes and CD19+CD10 blast subpopulation, while Imiquimod (TLR7) and ODN (TLR9) increased it on all CD10+ cells. This results are relevant since knowing the nature of these HLA-I (inhibitory o activating ligands) may help to understand the answer that NK cells will elicit.

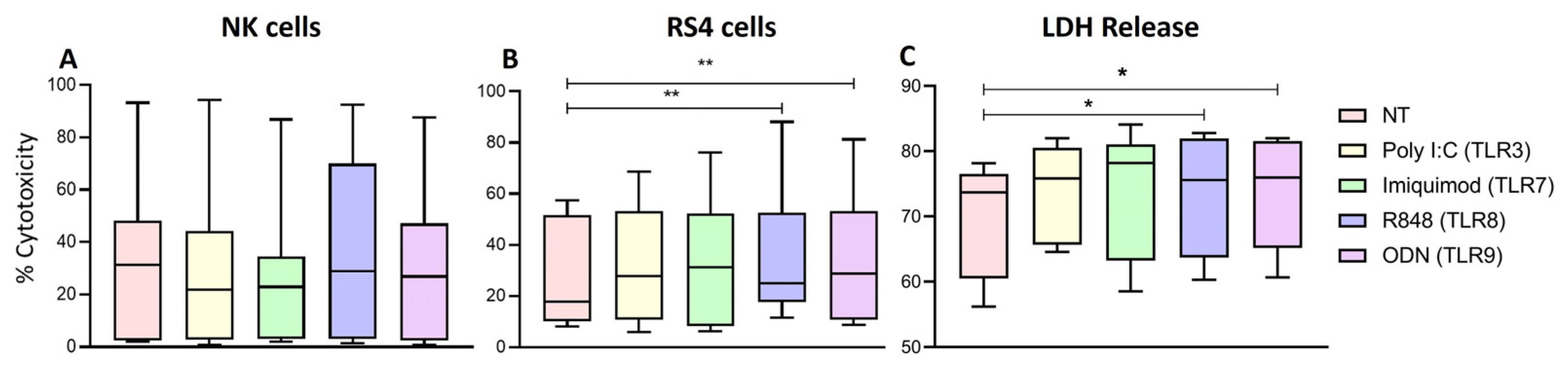

Finally, the measurement of the cytotoxic activity of NK cells through the release of LDH and by the assessment of cell death with Zombie NIR show that R848 and ODN were able to increase the cytotoxic activity of NK cells from patients with ALL against the RS4 cell line (leukemic blasts). These results aligned with those observed regarding Granzyme B, which can suggest that this is the mechanism unfolding the blast lysis, however this must be further evaluated to confirm. In addition, our results agree with Veziani et al. [

41] who demonstrated that specific TLR8 agonists increased cytokine production and cytotoxic activity.

In our work, it was evident that when the isolated CD56-CD16+ were stimulated, the increase in degranulation was not present with none of the TLR ligands, this in concordance with the literature that this subpopulation is “dysfunctional” due to the reduced cytotoxic potential, notably against tumor target cells [

46]. Recently, this population has been described in Kenyan children with Burkitt lymphoma [

47] and in non-virally Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia patients [

48] with adverse clinical outcome. A proteomic analysis showed that CD56-CD16+ shared some similarities with CD56dimCD16+ NK cells [

49], supporting the classification of this subset as NK cells. Furthermore, there has been suggested that this phenotype with a CD56 down regulated emerge in the presence of an immunosuppressive milieu [

50], even when the mechanism by which this happens remains unknow. This may explain the presence of this subpopulation in our patients with ALL and the impaired (lack of) function even after the stimulation. In our study we reported CD56-CD16+ as NK cells when isolated since we used negative selection, assuring the elimination of non-NK cells (CD14+, CD11c) and in de PBMCs due to the expression of NKG2D in 90% of this subpopulation.

Our results support the hypothesis that the activation with TLR ligand may restore the functionality and promote the expression of activation receptors of NK cell from patients with ALL. Various clinical trials with these studied ligands in solid tumors lay the groundwork for a potential translation to clinical applications in hematological malignancies. Poly I:C has been studied in combination with anti-PD1 on solid tumors (NCT03721679) [

51] and in Subjects with Unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma (NCT03732547) [

52]. Some Imiquimod trials evaluated effectiveness in cutaneous metastases of melanoma (NCT01264731) [

53] and cervical high-grade squamous intraepithelial neoplasia (NCT05405270) [

54]. One clinical trial for R848 evaluated the effect on T-cells in in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (NCT01676831) [

55] and as an adjuvant with vaccine therapy for melanoma (NCT00470379) [

56]. ODN has been studied as Injection Boosters against solid tumors (NCT04952272) [

57].

We acknowledge the limitations of our study confined to in vitro scenarios. Nonetheless, the significance of this information in literature serves as a crucial precedent. It indicates that NK cells, known to exhibit compromised functionality in hematologic neoplasms, possess the capacity to restore and enhance their cytotoxic and immunoregulatory anti-tumor functions through their endosomal TLR receptor stimulation. This sets the stage for a promising avenue of research, suggesting that these molecules warrant further exploration with an immunotherapeutic approach against hematologic neoplasms.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Patients

Twenty-four pediatric patients newly diagnosed between March 2022 and July 2023 with ALL, who had not received any prior treatment or transfusions and who had no infectious complications were included. Peripheral blood samples were taken with the prior informed consent of the patients' parents or guardians, in accordance with institutional protocols.

This study was approved by the Research, Ethics, and Biosafety Committees of the Hospital Infantil de México Federico Gómez, following the international guidelines for biomedical research in humans (approval no. CIOMS-WHO 1993).

4.2. Obtaining Mononuclear Cells, Isolating NK Cells, Culture and Activation with TLR Ligands

Mononuclear cells were isolated from peripheral blood by density gradient centrifugation with Lymphoprep™ (Axis-Shield, Boston, USA), according to the manufacturers protocol. To assess the direct activation of NK cells through TLRs, they were enriched from peripheral blood mononuclear cells using an EasySep™ Human NK Cell Isolation Kit (STEMCELL Technologies Inc. Vancouver, Canada), according to the manufacturer's protocol.

The obtained mononuclear cells (1 x106) were cultured in 1 mL of RPMI medium supplemented with 2% fetal bovine serum (FBS), in 48-well plates, and the enriched NK cells (1 x105) were cultured in 0.5 mL of RPMI medium supplemented with 2% FBS. The TLR ligands used, and their doses were: poly:IC 1 μg/mL (Sigma-Aldrich, USA), Imiquimod 0.1 μg/mL (Enzo life science, Plymouth, PA, EU), R-848 5 μg/mL (Enzo life science, Plymouth, PA, EU), and ODN 2006 1 ng/mL (Invivo, San Diego, CA, USA) (all concentrations were previously determined). Stimulation was left to proceed at 37ºC in a 5% CO2 atmosphere for 24 h.

4.3. Characterization of NK Cells and Determination of Activation

To characterize NK cells, they were stained for 20 min at 4°C, with 20 μL of Staning mix containing staining buffer (phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with 1% serum albumin) and the following antibodies antihuman: anti-CD3-pacific blue, (0.2 μg per 106 cells) anti-CD56-APC, (0.5 μg per 106 cells) anti-CD19-PECy7 (0.5 μg per 106 cells ) (All of them from BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA), and anti-CD16-PerCPcy5.5 (2.5 μL per 106 cells) (BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA). To determine the activation of NK cells, the change in the expression of CD107a and intracellular IFN-γ was used, as well as the expression of receptors NKG2D and NKp44; the expression of HLA class I was also determined. The cells were stained with anti-CD107a-FITC, (2.5 μL per 106 cells) anti-HLA ABC-PE, (5 μL per 106 cells) anti-NKG2D-APCCY7 (2.5 μL per 106 cells) (BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA), and anti-NKp44-VioBrightFITC (1 μg per 106 cells (Merck Millipore)). For intracellular staining, monensin (2 μM) (Biolegend, San Diego, CA, USA) was added to the culture during the last 4 hours of treatment. To detect intracellular cytokine production, cells were fixed, permeabilized with CytoFix/Cytoperm (BD bioscience) following the manufacturer’s protocol and stained with anti-IFN-γ-PECy7 (2.5 μL per 106 cells (Abcam, Cambridge United Kingdom) according to manufacturer's instructions. The maximum of staning mix volume used for tube of treatment were 20 μL the staining buffer volume varied depending of the tubes to stain

Reading was performed on the CytoFLEX flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter) and analysis was performed with the FlowJo software V.10

4.4. Granzyme B Detection

The concentration of granzyme B in the supernatants of cells cultured and treated with TLR ligands was determined using the commercial Human Granzyme B DuoSet ELISA kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis USA), following the manufacturer's instructions. The optical density of each well was measured at 450 and 570 nm in a microplate reader (Agilent BioTek™ Epoch, Santa Clara, USA) with a margin of no more than 30 minutes.

4.5. Cytokines Determination

The concentration of cytokines (IFN-γ, IL-2, IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6) and chemokines (IL-8 and MCP-1) in the supernatants of cells cultured and treated with TLR ligands was determined using the commercial kit Human Cytokine/Chemokine Magnetic Bead Panel-Immunology Multiplex Assay (Millipore, Massachusetts, USA), following the manufacturer's instructions. The optical density of each well was measured with the MagPix plate reader (Luminex, Austin, USA).

4.6. Interferon Gamma Determination

IFN-γ was determined in supernatants of enriched NK cells. After 24 h of stimulation, of the enriched NK cells, with the TLRs ligands, the supernatant was collected and stored at –20°C in aliquots until analysis. The sample was thawed only once to avoid degradation. IFN-γ was determined with the commercial ELISA IFN-γ OptEIA kit (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer´s instructions. The optical density of each well was measured at 450 nm in a microplate reader (Agilent BioTek™ Epoch, Santa Clara, USA) with a margin of no more than 30 minutes.

4.7. Cytotoxicity Assays

4.7.1. Zombie NIR Assay

The increase in cytotoxic activity of NK cells stimulated with the specific TLR ligands was measured by using a viability marker (Zombie NIR, Biolegend, San Diego, USA). Briefly: enriched NK cells from patients with leukemia were co-cultured with the RS4;11 CRL-1873 cell line from ATCC in a 1:2 ratio in RPMI medium with 2% FBS; then, they were stimulated or not with each ligand of TLR3, TLR7, TLR8, and TLR9 and incubated for 24 h at 37°C with 5% COAfter incubation, cells were harvested and stained with 100 μL of Zombie NIR (1:1000 dilution with PBS) to evaluate viability in a CytoFLEX flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter). Analysis was performed with the FlowJo software version V.10.

4.7.2. LDH Release Assay

This assay was also used to measure the cytotoxicity of the effector cells (enriched NK cells from ALL patients) against the target cells (RS4;11 CRL-1873 cell line from ATCC). We used the commercial kit CytoTox 96 non-radioactive assay (Promega, Wisconsin, EU) to measure the concentration of LDH released by the dead target cells after the co-culture with the NK cells, following the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly: stimulated enriched NK cells were co-cultured with the RS4 cell line in RPMI medium with 2% FBS, for 24 h at 37°C with 5% COAfter incubation, they were centrifuged and the supernatant was stored at -20 until used. The supernatant of co-cultures with each treatment and the supernatant of NK cells and RS4 cell lines alone were placed by triplicate in a 96-well plate. The substrate provided by the kit was added to each well and the plate was incubated for 30 min at 37ºC protected from light. Finally, stop solution was added and reading was carried out at 490 nm in a microplate reader (Agilent BioTek™ Epoch, Santa Clara, USA) with a margin of no more than 30 minutes. To determine the cytotoxic activity of the NK cells against target RS4; 11 cells, we used the following formula.

4.8. Statistical Analysis

The median frequencies of the different subpopulations of peripheral blood NK cells and enriched NK cells from patients with ALL from each treatment were compared with the non-treated cells using a Friedman test. GraphPad Prism version 8 (GraphPad Software Inc., Boston, USA) was used for the statistical analysis.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, C.MB. and J.GZ.; methodology, J.GZ.; software, J.GZ.; validation, C.MB., J.GZ. and E.PF.; formal analysis, J.GZ.; investigation, J.GZ.; resources, J.GZ.; data curation, J.GZ and E-PF.; writing—original draft preparation, J.GZ.; writing—review and editing, C.MB., J.GZ., V.OL., A.MS., E.JH. and E.O.; visualization, J.GZ.; supervision, C.MB., E.O., E.PF., V.OL., A.MS. and E.JH.; project administration, C.MB.; funding acquisition, C.MB. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

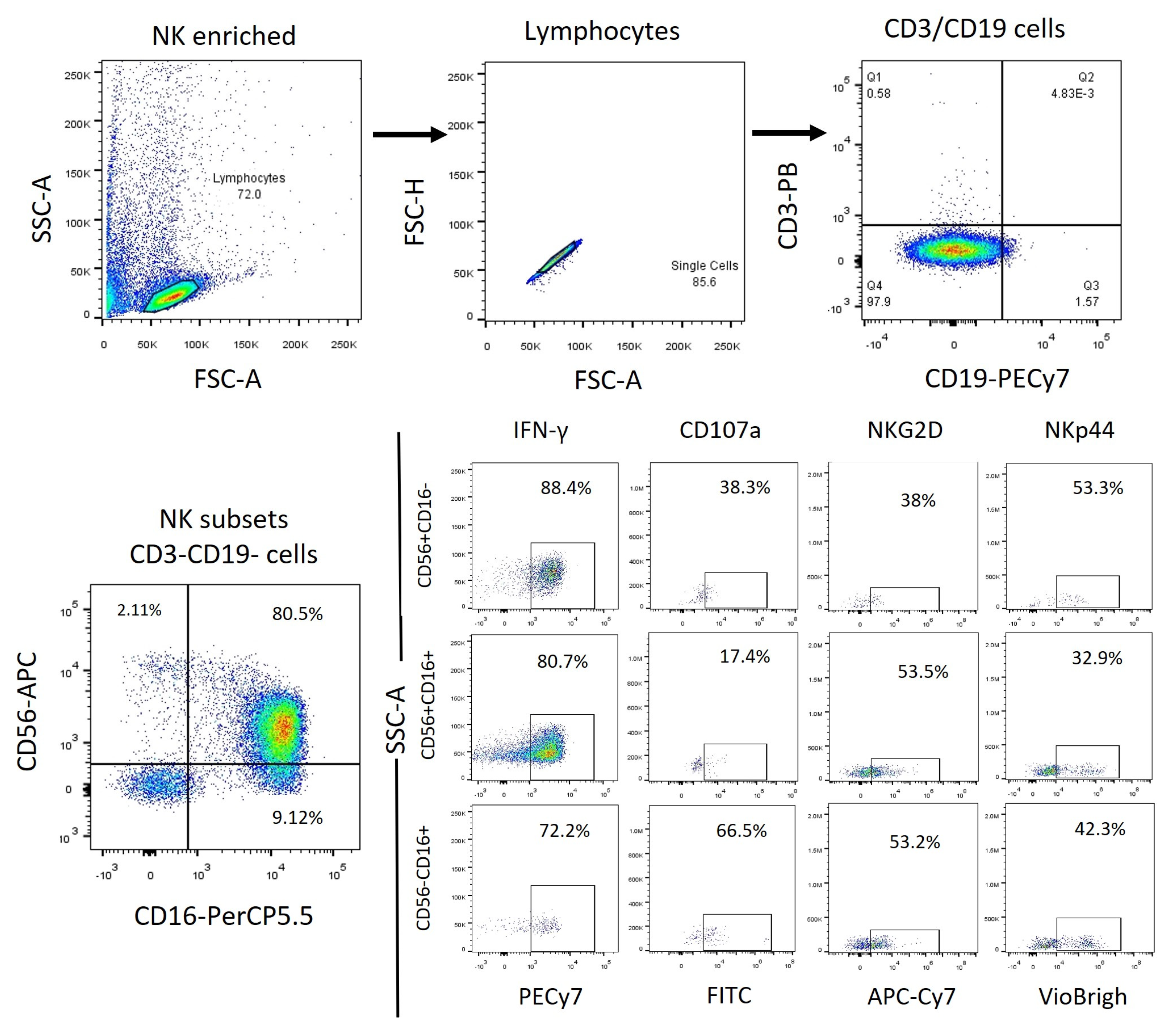

Figure 1.

PBMC Flow cytometry analysis strategy. We obtained the total NK cells (CD3-, CD19-) from the lymphocyte’s population identified by granularity-size and from this population we obtained the NK cells subpopulations depending on their expression of CD56 and CDFinally, from each subpopulation, we obtained the expression of the markers to be analyzed.

Figure 1.

PBMC Flow cytometry analysis strategy. We obtained the total NK cells (CD3-, CD19-) from the lymphocyte’s population identified by granularity-size and from this population we obtained the NK cells subpopulations depending on their expression of CD56 and CDFinally, from each subpopulation, we obtained the expression of the markers to be analyzed.

Figure 2.

Enriched NK cells Flow cytometry analysis strategy. We obtained the total NK cells (CD3-, CD19-) from the lymphocytes population identified by granularity-size and from this population we obtained the NK cell subpopulations depending on their expression of CD56 and CDFinally, from each subpopulation, we obtained the expression of the markers to be analyzed.

Figure 2.

Enriched NK cells Flow cytometry analysis strategy. We obtained the total NK cells (CD3-, CD19-) from the lymphocytes population identified by granularity-size and from this population we obtained the NK cell subpopulations depending on their expression of CD56 and CDFinally, from each subpopulation, we obtained the expression of the markers to be analyzed.

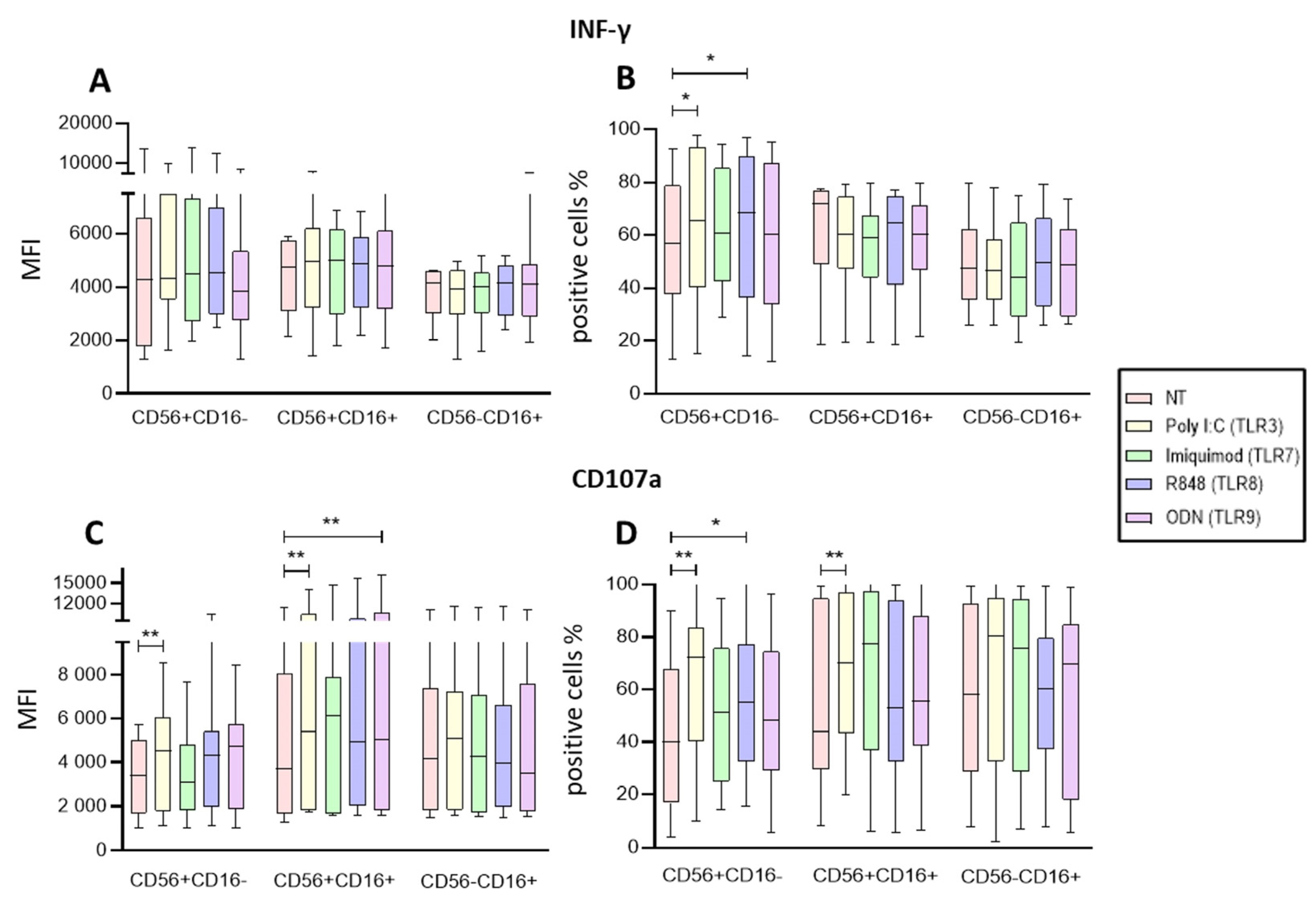

Figure 3.

Functional Activity of the NK cells within PBMCs after endosomal TLR stimulation. A The MFI of intracellular IFN-γ was determined in the three subpopulations for each treatment and compared to the MFI of non-treated cells B The median of the percentage of the IFN-γ expressing cells was determined and compared with the percentage of non-treated cells expressing IFN-γ. C The median of the Median Fluorescence Intensity (MFI) of CD107a was determined for each treatment in the three subpopulations and compared to the MFI of non-treated cells (control). D The median of the percentage of the CD107a expressing cells was determined for each treatment in the three subpopulations and compared with the percentage of non-treated cells expressing CD107a. The box and whisker plot was employed to visualize the distribution of the data, highlighting the central tendency, spread and the outlier’s values within the dataset. The Friedman test was used for the comparison. *p<0.05, **p<0.005.

Figure 3.

Functional Activity of the NK cells within PBMCs after endosomal TLR stimulation. A The MFI of intracellular IFN-γ was determined in the three subpopulations for each treatment and compared to the MFI of non-treated cells B The median of the percentage of the IFN-γ expressing cells was determined and compared with the percentage of non-treated cells expressing IFN-γ. C The median of the Median Fluorescence Intensity (MFI) of CD107a was determined for each treatment in the three subpopulations and compared to the MFI of non-treated cells (control). D The median of the percentage of the CD107a expressing cells was determined for each treatment in the three subpopulations and compared with the percentage of non-treated cells expressing CD107a. The box and whisker plot was employed to visualize the distribution of the data, highlighting the central tendency, spread and the outlier’s values within the dataset. The Friedman test was used for the comparison. *p<0.05, **p<0.005.

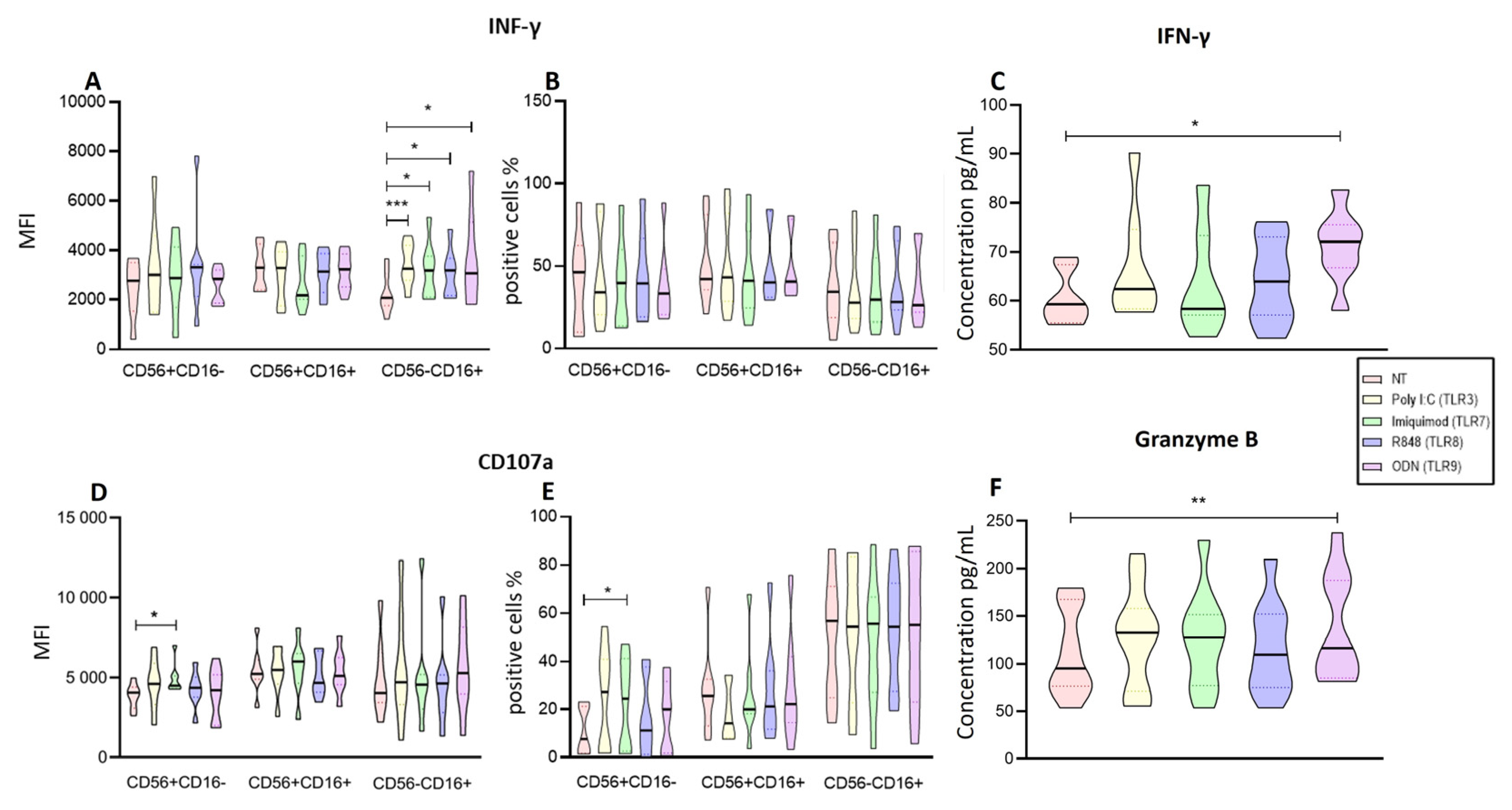

Figure 4.

Functional Activity of the enriched NK cells after endosomal TLR stimulation. A The MFI of IFN-γ was determined for each treatment in the three subpopulations and compared to the non-treated MFI. B The median of the percentage of the IFN-γ expressing cells was determined and compared with the percentage of non-treated cells expressing IFN-γ. C Concentration of IFN-γ in supernatants of enriched NK cells after endosomal TLR stimulation D The median of the Median Fluorescence Intensity (MFI) of CD107a was determined for each treatment in the three subpopulations and compared to the MFI of non-treated cells (control). E The median of the percentage of the CD107a expressing cells was determined and compared with the percentage of non-treated cells expressing CD107a. F The concentration of Granzyme B in supernatants of enriched NK cells after endosomal TLR stimulation. The violin plot was employed similar to the box-and-whiskers plot, to visualize the full distribution of the data, providing shape and density within the dataset. The Friedman test was used for the comparison. *p<0.05, **p<0.005, ***p<0.0005.

Figure 4.

Functional Activity of the enriched NK cells after endosomal TLR stimulation. A The MFI of IFN-γ was determined for each treatment in the three subpopulations and compared to the non-treated MFI. B The median of the percentage of the IFN-γ expressing cells was determined and compared with the percentage of non-treated cells expressing IFN-γ. C Concentration of IFN-γ in supernatants of enriched NK cells after endosomal TLR stimulation D The median of the Median Fluorescence Intensity (MFI) of CD107a was determined for each treatment in the three subpopulations and compared to the MFI of non-treated cells (control). E The median of the percentage of the CD107a expressing cells was determined and compared with the percentage of non-treated cells expressing CD107a. F The concentration of Granzyme B in supernatants of enriched NK cells after endosomal TLR stimulation. The violin plot was employed similar to the box-and-whiskers plot, to visualize the full distribution of the data, providing shape and density within the dataset. The Friedman test was used for the comparison. *p<0.05, **p<0.005, ***p<0.0005.

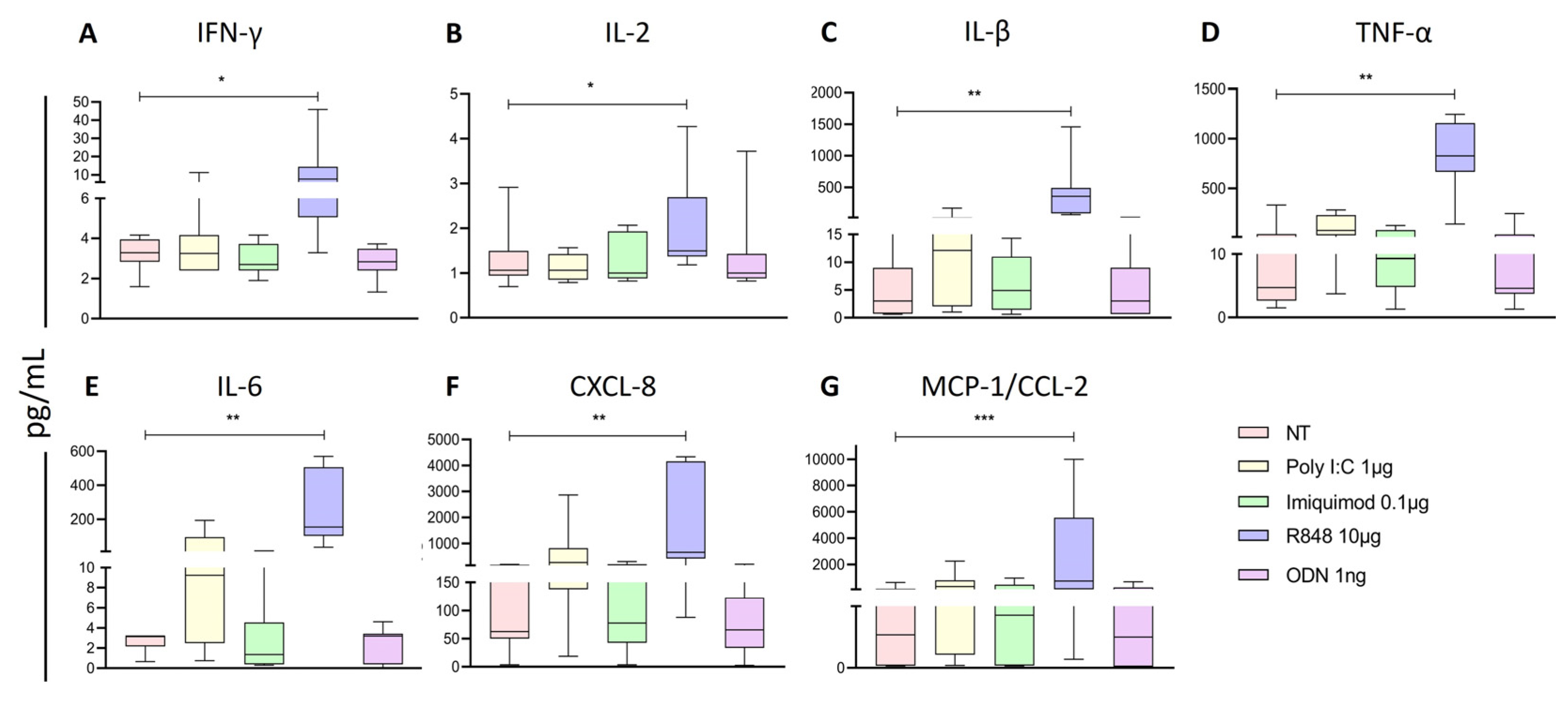

Figure 5.

C IL-2, D TNF-α, E IL-6, F IL-8, and G MCP-1 was determined for each treatment and compared to the non-treated cells. The Friedman test was used for the comparison. *p<0.05, **p<0.005.

Figure 5.

C IL-2, D TNF-α, E IL-6, F IL-8, and G MCP-1 was determined for each treatment and compared to the non-treated cells. The Friedman test was used for the comparison. *p<0.05, **p<0.005.

Figure 6.

Analysis of Activation markers of the different subpopulations of NK cells from PBMCs after endosomal TLR stimulation. A The MFI of NKG2D expression was determined for each treatment in the three subpopulations and compared to the MFI of non-treated cells. B The median of the percentage of NKG2D expressing cells after treatment with the TLRs ligands was determined and compared with the percentage of non-treated cells expressing it. C The MFI of NKp44 expression was determined for each treatment in the three subpopulations and compared to the MFI of non-treated cells. D The median of the percentage of NKp44 expressing cells after treatment with the TLR ligands was determined and compared with the percentage of non-treated cells expressing it. The box and whisker plot was employed to visualize the distribution of the data, highlighting the central tendency, spread and the outlier’s values within the dataset. The Friedman test was used for the comparison. *p<0.05, **p<0.005.

Figure 6.

Analysis of Activation markers of the different subpopulations of NK cells from PBMCs after endosomal TLR stimulation. A The MFI of NKG2D expression was determined for each treatment in the three subpopulations and compared to the MFI of non-treated cells. B The median of the percentage of NKG2D expressing cells after treatment with the TLRs ligands was determined and compared with the percentage of non-treated cells expressing it. C The MFI of NKp44 expression was determined for each treatment in the three subpopulations and compared to the MFI of non-treated cells. D The median of the percentage of NKp44 expressing cells after treatment with the TLR ligands was determined and compared with the percentage of non-treated cells expressing it. The box and whisker plot was employed to visualize the distribution of the data, highlighting the central tendency, spread and the outlier’s values within the dataset. The Friedman test was used for the comparison. *p<0.05, **p<0.005.

Figure 7.

Analysis of Activation markers of the different subpopulations of enriched NK cells after endosomal TLR stimulation. A The MFI of NKG2D expression was determined for each treatment in the three subpopulations and compared to the MFI of non-treated cells. B The median of the percentage of NKG2D expressing cells after treatment with the TLR ligands was determined and compared with the percentage of non-treated cells expressing it. C The MFI of NKp44 expression was determined for each treatment in the three subpopulations and compared to the MFI of non-treated cells. D The median of the percentage of NKp44 expressing cells after treatment with the TLR ligands was determined and compared with the percentage of non-treated cells expressing it. The violin plot was employed similar to the box-and-whiskers plot, to visualize the full distribution of the data, providing shape and density within the dataset. The Friedman test was used for the comparison. *p<0.05, **p<0.005.

Figure 7.

Analysis of Activation markers of the different subpopulations of enriched NK cells after endosomal TLR stimulation. A The MFI of NKG2D expression was determined for each treatment in the three subpopulations and compared to the MFI of non-treated cells. B The median of the percentage of NKG2D expressing cells after treatment with the TLR ligands was determined and compared with the percentage of non-treated cells expressing it. C The MFI of NKp44 expression was determined for each treatment in the three subpopulations and compared to the MFI of non-treated cells. D The median of the percentage of NKp44 expressing cells after treatment with the TLR ligands was determined and compared with the percentage of non-treated cells expressing it. The violin plot was employed similar to the box-and-whiskers plot, to visualize the full distribution of the data, providing shape and density within the dataset. The Friedman test was used for the comparison. *p<0.05, **p<0.005.

Figure 8.

represents the mature B cells, B CD10+ represents the marker of lymphoid progenitor cells, and C CD10+ CD19+ represents the pre-B cells from the patients with ALL. The median of MFI and the median of the percentage of HLA-I was determined for each treatment and compared to the non-treated cells. The box and whisker plot was employed to visualize the distribution of the data, highlighting the central tendency, spread and the outlier’s values within the dataset. The Friedman test was used for the comparison. *p<0.05, **p<0.005 ***p<0.0005.

Figure 8.

represents the mature B cells, B CD10+ represents the marker of lymphoid progenitor cells, and C CD10+ CD19+ represents the pre-B cells from the patients with ALL. The median of MFI and the median of the percentage of HLA-I was determined for each treatment and compared to the non-treated cells. The box and whisker plot was employed to visualize the distribution of the data, highlighting the central tendency, spread and the outlier’s values within the dataset. The Friedman test was used for the comparison. *p<0.05, **p<0.005 ***p<0.0005.

Figure 9.

Cytotoxic activity of NK cells. A The median of the percentage of NK cells death was determined for each treatment and compared with the percentage of non-treated cells death. B The median of the percentage of RS4 death was determined for each treatment and compared with the percentage of non-treated cells death. C Cell-mediated cytotoxic activity, the median of the percentage of LDH released into the supernatant of cocultures of RS4 cells with NK cells. The box and whisker plot was employed to visualize the distribution of the data, highlighting the central tendency, spread and the outlier’s values within the dataset. The Friedman test was used for the comparison. *p<0.05, **p<0.005 ***p<0.0005.

Figure 9.

Cytotoxic activity of NK cells. A The median of the percentage of NK cells death was determined for each treatment and compared with the percentage of non-treated cells death. B The median of the percentage of RS4 death was determined for each treatment and compared with the percentage of non-treated cells death. C Cell-mediated cytotoxic activity, the median of the percentage of LDH released into the supernatant of cocultures of RS4 cells with NK cells. The box and whisker plot was employed to visualize the distribution of the data, highlighting the central tendency, spread and the outlier’s values within the dataset. The Friedman test was used for the comparison. *p<0.05, **p<0.005 ***p<0.0005.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristic of the study group.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristic of the study group.

| Patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia |

|---|

| Characteristics |

Peripheral blood |

| N° of cases |

24 |

| Sex (M:F) |

14:10 |

| Age media (range) |

7 (1-17) years |

| Immunophenotype |

|

| Pre-B |

22 |

| not defined |

2 |

| % NK Cells (range) |

1.87 (0.4-5.97) |