1. Introduction

The influenza is a constant threat that causes important morbidity and mortality in the world, being responsible for one million serious cases annually in children under 5 years of age worldwide, which represents a huge public health problem with high socioeconomic implications [

1].

In 2012, the World Health Organisation (WHO) [

2] included children aged 6 to 59 months as a target population for influenza vaccination because of the high burden of disease in this age group. In the same year, the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) [

3] produced a technical report in which it took a favourable position on vaccination in this age group. The Advisory Committee in Immunization Practices (ACIP) in the USA included universal influenza vaccination for children aged 6 to 23 months in the year 2004 [

4], and for those aged 24 to 59 months later in 2006 [

5]. More than 70 countries now include influenza vaccination in their childhood and adolescent vaccination schedules [

6].

In Spain, the greatest burden of disease occurs in the group of children under 5 years of age, both due to the use of health resources and morbidity associated. Regarding the incidence, the most affected age groups were those under 15 years of age, considering both the last season prior to the COVID-19 pandemic (2019-2020) and in the previous ones. The maximum weekly incidence rate was reported in the 0-4 years group, even overcoming the incidence of the 5-14 years group. It should be noted that in the 2013-2014 to 2019-2020 seasons, the 0 to 4 years age group experienced an average of 4,239 hospital admissions, of which 822 were considered severe hospitalizations and 249 Intensive Care Unit (ICU) admissions and 8 deaths were recorded [

7]. Because of this, the Public Health Commission approved in October 2022 the document "Influenza vaccination recommendations for children aged 6 to 59 months" [

8] previously approved by the National Immunization Technical Advisory Group in July 2022, thus culminating the work that began years before, in 2019, and which was interrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic. It recommends universal vaccination of all children aged 6 to 59 months, in order to protect them because of their high burden of disease, starting in the 2023–2024 season. This recommendation was reflected in the common lifelong vaccination schedule for 2023 [

9].

Three Spanish autonomous communities, Andalusia, Galicia, and the Region of Murcia, have already started with universal vaccination in this age group in the 2022-2023 season. The Region of Murcia was the only Spanish autonomous community to use the live attenuated intranasal vaccine (LAIV) for children aged 24 to 59 months, without any contraindication for this vaccine. In this campaign the inactivated intramuscular vaccine (IIV) was used for children aged 6 to 23 months or for those with contraindication in the use of LAIV [

10]. The Vaccination Advisory Committee of the Spanish Association of Paediatrics recommends in its immunisation schedule for the year 2023, preferably, the intranasal influenza vaccine from the age of 24 months onwards [

11]

In this first campaign, the coverage objective set in the three autonomous communities was 50%, a relatively ambitious objective for a seasonal vaccination campaign restricted to certain months of the year. In this regard, the communication, information and recruitment strategies carried out by Public Health Authorities, the attitude of healthcare professionals towards influenza vaccination is fundamental due to their informative and active recruitment work, to achieve the objective vaccination coverage set. Therefore, the main objective of this study is to evaluate the attitude of healthcare professionals towards the first universal influenza vaccination campaign in children aged 6 to 59 months in our autonomous community, as well as their degree of acceptability of each of the influenza vaccines used. The secondary objective was to evaluate the attitude of healthcare professionals towards the pilot school influenza vaccination campaign and the possibility of its widespread implementation.

To our understanding, this study provides highly valuable information about healthcare professionals attitude towards universal paediatric vaccination because of the novelty of the program in our country. A detailed analysis of the opinion provided by different type of healthcare professionals involved in vaccinations campaigns may be of high interest for other Spanish or even European authorities, encouraging them to promote similar programs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Framework

The FLUTETRA study is a cross-sectional descriptive study to assess the attitude of healthcare professionals providing paediatric care (doctors and nurses) towards childhood influenza vaccination in the Region of Murcia. Once the vaccination campaign had ended, an online questionnaire was sent by e-mail three times, seven days apart, as a reminder to all Primary Care healthcare professionals, both in the public and private settings.

Aiming the higher participation possible in the study, only two inclusion criteria for participation in the study were stablished: i) to be a healthcare professional providing paediatric care, including paediatricians, family doctors and nurses, within the Primary Care setting of the autonomous community under study, the Region of Murcia and ii) ticking the box to give consent of participation in the study. No exclusion criteria were defined.

The analysis was only performed among those healthcare professionals who had directly or indirectly participated in the campaign by vaccination per se, providing counselling or recruiting patients.

2.2. Variables

After agreeing to participate in the study, the healthcare professionals completed the questionnaire designed ad-hoc (provided as a supplementary file), which gathered the following information about the responders: sociodemographic variables, type of healthcare professional, attitude towards influenza vaccination, assessment of available products and factors associated with school influenza vaccination.

A 5-points Likert scale was used to score the survey, from 1 (lowest score) to 5 (higher score). The item evaluated and the response categories vary according to the question (see supplementary file)

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with SAS v9.4 software through the SAS Enterprise Guide v8.3 interface.

For the descriptive analysis of the qualitative variables, frequency distribution tables and percentages were used. Data analysis was performed both overall and stratified by profession, establishing a Nursing group and a Medical group.

To assess the comparison between qualitative variables, Chi-square test was used when applicable, and Fisher’s exact test was used for those cases of Chi-square non-applicability (i.e. for low frequencies).

Additionally, a post-hoc multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to determine if the healthcare professional characteristics were independently associated with their opinion about the utility/feasibility of extending the school vaccination through the whole Region of Murcia in the next season vaccination campaign. For this purpose, the following covariates were assessed: grade of relevance of paediatric vaccination against influenza, involvement in paediatric vaccination of children from 6 to 59 months, age, profession, sex, prior experience in vaccination against influenza, participation in the pilot experience, LAIV ease/convenience of administration, and LAIV general rating. Variables with p <0.2 in the bivariate logistic regression analysis were considered significant and included in a multivariate model with stepwise selection method, and odds ratio (OR) and 95% CIs were calculated. Test results with p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

2.4. Ethics

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee for Investigation with Medicinal Products of Hospital Clínico Universitario Virgen de la Arrixaca-Area 1 of the autonomous community where study was conducted. Participants marked a first mandatory box as acceptance of their participation in the study after due information prior to completing the online questionnaire.

The study was conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the regulations contained in the Declaration of Helsinki, which are included in the current legislation on biomedical research.

3. Results

The study survey was provided to a total of 1,140 professionals from which 339 answered the online survey, meaning that the response rate of the survey was 29.73%. Overall responders, 284 professionals (88.47% of those who answered, 95% CI 85.07-91.87%) declared that they participated in the vaccination campaign, both regularly and occasionally. Only the records of involved professionals (n=284) were considered for this analysis, which means 28.16% of the total of 1,140 professionals. The responder’s profile was a female professional, aged 40-49 years with regular experience in influenza vaccination, with a higher proportion of nurses. The detailed sociodemographic description of the participating professionals is summarized in

Table 1, with statistically significant differences (

p<0.001) between doctors and nurses with respect to age. No statistically significant differences were found regarding other sociodemographic variables, such as sex and previous experience on influenza vaccination.

Among the surveyed population involved in vaccination, most of the nursing group were paediatric nurses (54.4%), followed by family nurses (28.7%), school nurses (16.4%) and family and paediatric nurses (0.5%). Regarding the Medical group, only two types of specialists were involved: paediatricians (80.5%) and family and community doctors (19.5%).

When asked about the importance of influenza vaccination in children aged 6 to 59 months in terms of disease burden, 91.9% of the professionals assigned a score of 4 and 5 on the Likert scale, with statistically significant differences (p<0.001) in relation to profession, with a higher proportion among doctors (n=80; 97.6%) compared to nurses (n=181; 89.6%).

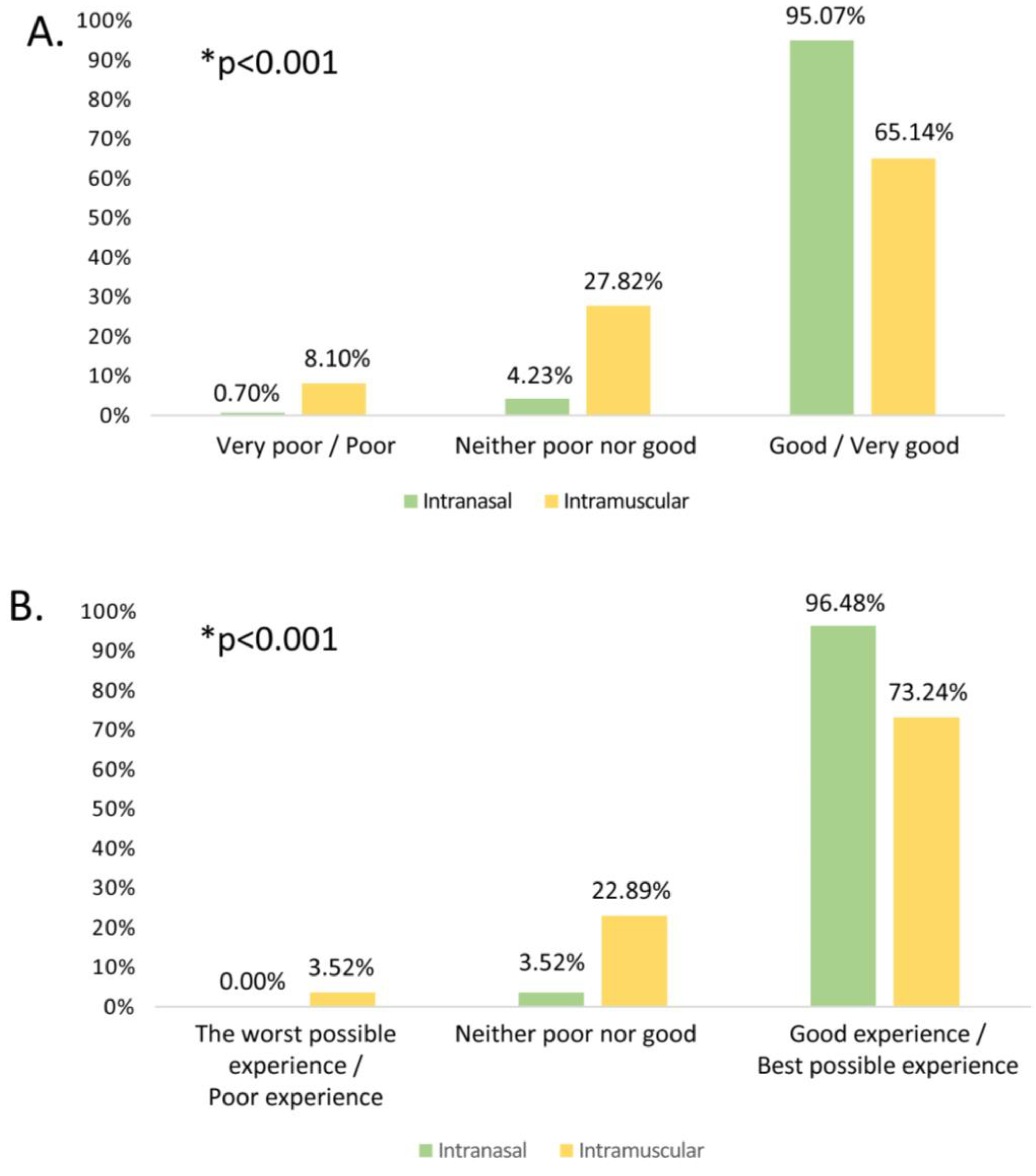

Regarding the ease/comfort of administration assessment of the type of vaccine administered, the mean (±SD) scores in the Likert scale obtained from intranasal and intramuscular vaccines were 4.65±0.6 and 3.8±0.97 respectively. A high percentage of respondents appreciated the ease/comfort of administration of the intranasal influenza vaccine, with significantly higher scores in the overall rating in comparison to intramuscular vaccines (

Figure 1).

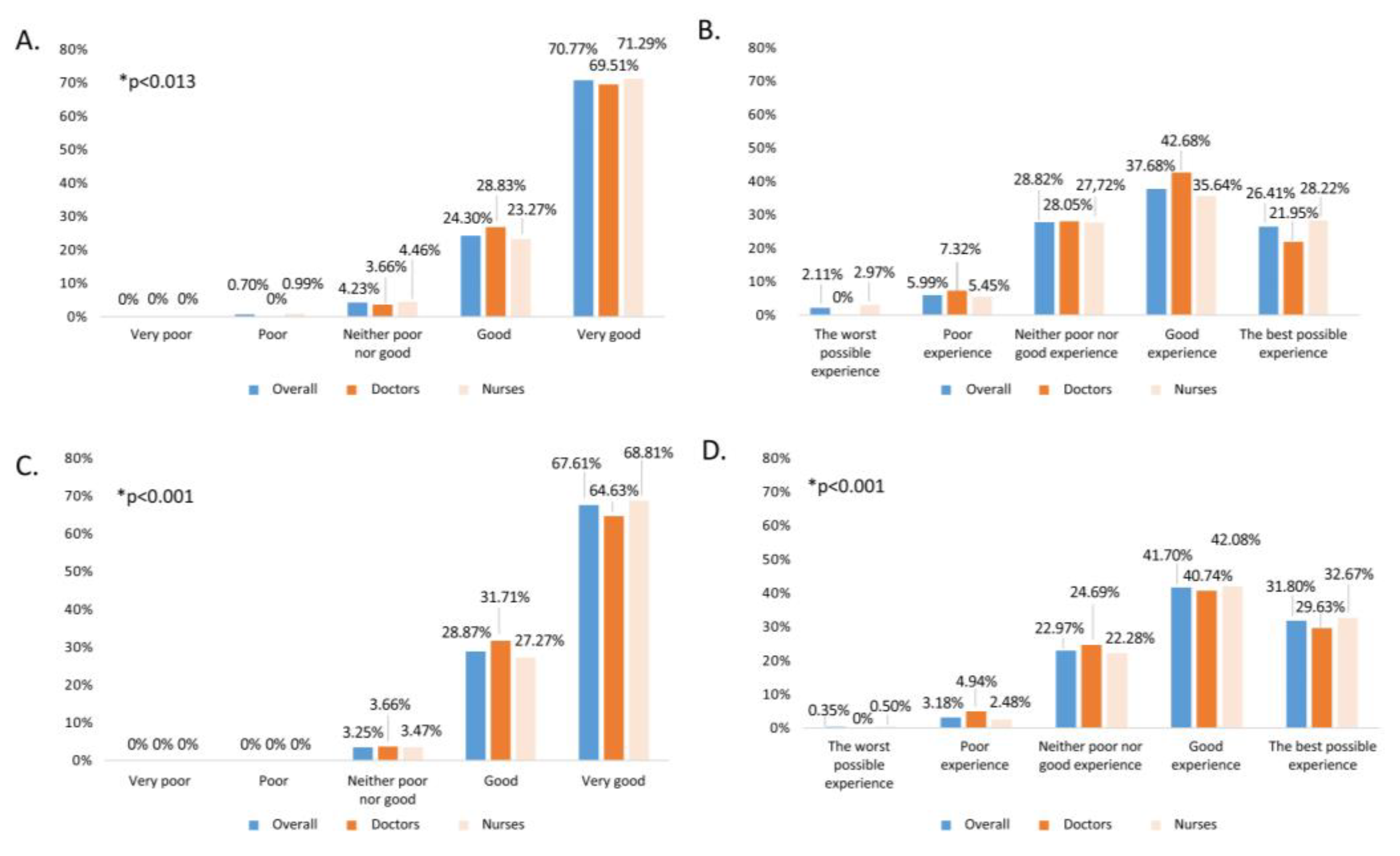

In addition, both ease/comfort and the overall assessment of each of the vaccines in the study population were evaluated in a comparative analysis by professional group, as well as the percentages of scores according to the Likert scale (

Figure 2). Overall, mean scores were 4.64±0.55 for intranasal vaccine and 4.01±0.84 for intramuscular. No statistically significant differences were found between professional groups.

In regard to the preference for using the intranasal vaccine in children aged 24 to 59 months for the next campaign in those cases indicated according to the Summary of the Product, 97.5% of the professionals affirmed that they preferred it (100% of doctors and 96.5% of nurses), with no statistically significant differences by professional category.

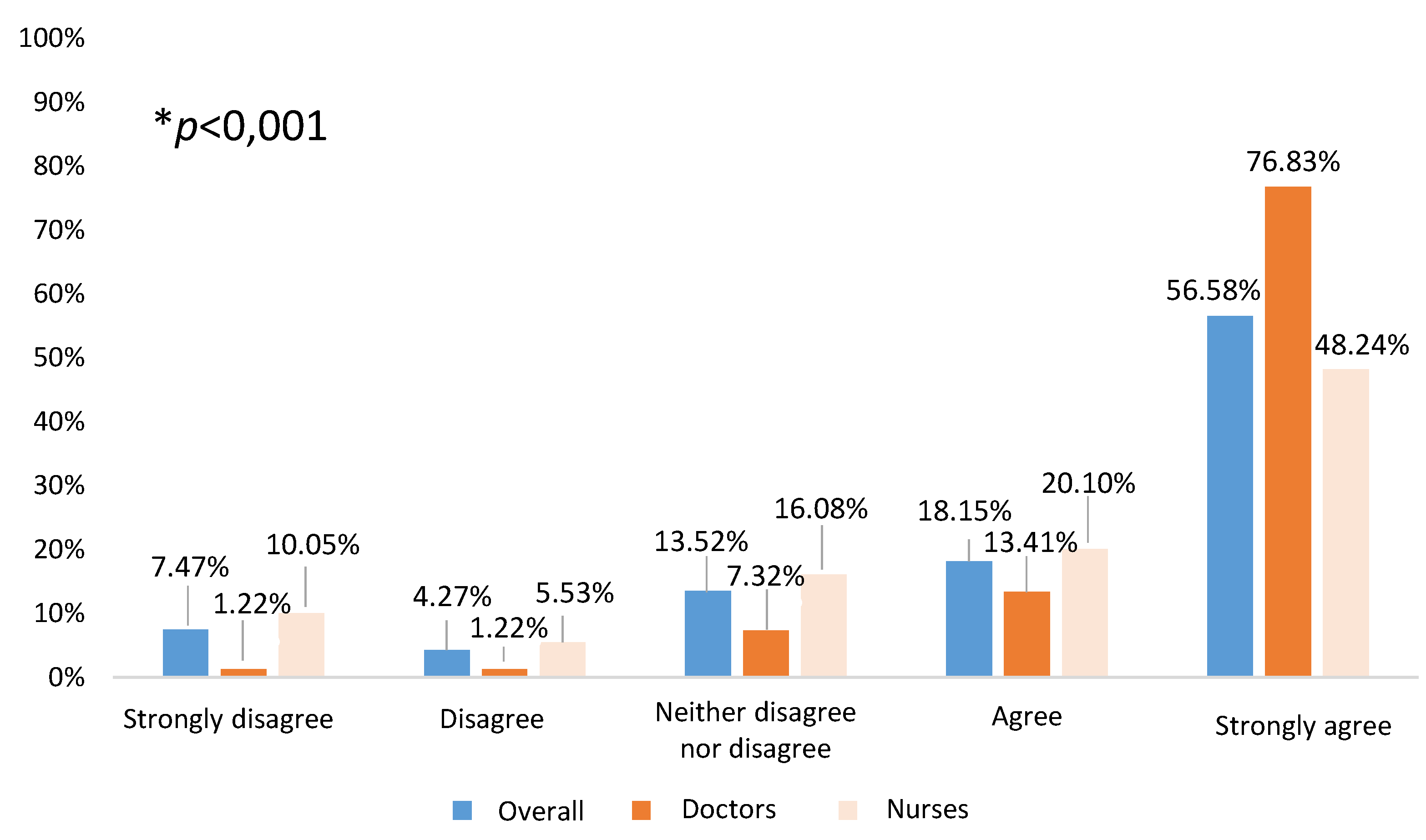

Only 13.79% (95% CI 10.12-17.46%) of the surveyed had participated in the school vaccination pilot experience. All the professionals, both participants and not participants in the pilot, were asked about the usefulness/feasibility of extending school influenza vaccination to children under 3 and 4 years of age, and most of them gave scores of 4 or 5 (74.73%). Statistically significant differences by professional category were observed (

p<0.001), as shown in

Figure 3. Stratified according to participation, a significantly higher percentage (

p=0.033) of professionals assigned a score of 4 or 5 (86.36%) in the former compared to the latter (72.27%).

In addition, participants were asked to give their opinion on the importance of the presence of a medical doctor at the school vaccination. The most chosen answer by all participants, independently of professional group, was advisable but not essential (nursing group: 47.2% and medical group: 40.2%). Answers stratified according to professional groups showed that 38.2% of the nursing group judged completely essential the presence of doctors, and only 13.6% considered that the nursing team can autonomously deal with vaccination. In contrast, medical doctors were of the opinion that the nursing team can autonomously deal with vaccination (36.6%) and their presence is only completely essential for 17.1% of the respondents. Answers stratified by professional group were statistically significant (p<0.001). When the stratification was made by those who had participated in the pilot with respect to those who had not, in relation to the recommendation or essential presence of a doctor (72.7% vs 77.6% respectively), despite no statistically significant differences between both groups, the percentage was lower in those of the pilot. However, within each of them, statistically significant differences (p<0.001) were evident by professional category (80.6% in nursing vs 53.8% in doctors in the participants in the pilot, compared to 83.9% in nursing and 62.3% in those who did not participate), also lower in those who took part in the pilot experience.

When asking about the type of vaccine used in school vaccination (intranasal or intramuscular), the vast majority considered the intranasal vaccine as the vaccine of choice for school vaccination (90.6%), evaluating it as recommended or essential for it. Only 5.0% considered the choice of the vaccine to be administered as indifferent and the rest considered the use of the intramuscular vaccine advisable or essential.

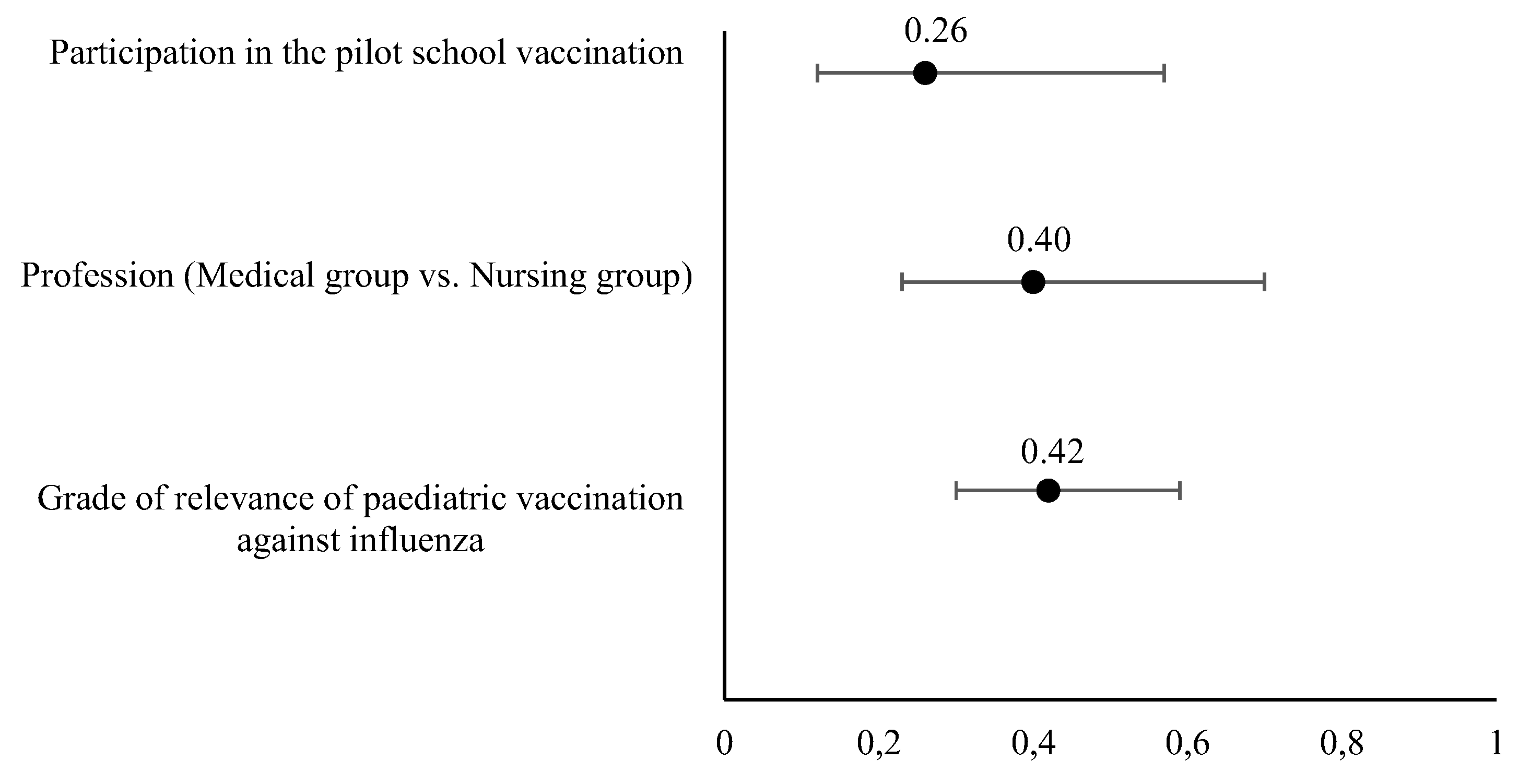

According to the logistic regression, three covariates were independently associated with a favourable opinion of extending the school vaccination pilot program. A unitary increase of the grade of relevance of paediatric vaccination (as considered by the healthcare professional) increased in a 0.42 (odds ratio, OR) the favourable opinion, as well as belonging to the Medical group (OR = 0.4). Similarly, the participation in the pilot vaccination school program was considered independently associated with the favourable opinion of extending the school program (OR= 0.26). The univariate and multivariate models extracted from the logistic regression analysis and the odds ratio are displayed in

Table 2 and

Figure 4 respectively)

4. Discussion

Healthcare professionals are one of the most important sources of information for families in making decisions about vaccination [

12,

13,

14]. This is even more important when discussing a seasonal vaccination campaign and a new vaccination strategy with a vaccine, such as the attenuated vaccine, which has established an unprecedented experience in the Region of Murcia and Spain due to its characteristics and route of administration during the 2022–2023 vaccination campaign.

Our work elicited responses from 82 physicians (paediatricians and family doctors) and 202 nurses (

Table 1). The 91.9% of surveyed professionals thought that influenza vaccination in children aged 6 to 59 months was important or very important, a view shared by doctors and nurses, with a statistically significant difference, which is probably not of practical relevance (97.6% vs. 89.6%). Similar results have been described in Quebec, where more than 90% of professionals agreed with influenza vaccination [

15], or in the USA, where 84% of paediatricians shared the opinion of the importance of vaccination [

16]. These data contrasts with the results obtained in a study carried out in Australia, which found a lack of awareness of the seriousness of influenza in children [

17]. The positive attitude detected among our professionals may be because the health authorities [

8] and scientific societies agreement on the recommendations [

18], and probably also because of the accumulated experience of childhood influenza vaccination in other countries for years.

Although universal paediatric influenza vaccination started in the 2022–2023 season, 89.8% of the professionals had experience of influenza vaccination with the intramuscular vaccine, while the inhaled vaccine had been scarcely available previously. When asked about ease/comfort of administration, 95% said that the intranasal vaccine is easy or very easy to administer, compared to 65.1% for the intramuscular vaccine (

Figure 1). Similarly, when rating their overall experience with the vaccines, 96.5% rated the inhaled vaccine positively or very positively, compared to only 73.2% for the intramuscular vaccine. With respect to the inhaled vaccine, it also remarkable that only 0.7% rated the convenience of its administration negatively, which would support the simplicity of its use, given that this is the first season of widespread administration, and it is expected that the ease of use will increase as experience with it increases throughout the coming seasons. This difference is illustrated when asking comparatively about the two vaccines; however, it is not observed when asking about each of the vaccines without making a comparison between them (

Figure 2), as both vaccines score positively or very positively, especially in terms of ease of administration. The intranasal vaccine was preferred by 97.5% of the professionals, who stated that they would prefer it for the next vaccination campaign.

Studies comparing the two vaccines are rare, and ours is one of the few to address this issue. In a study conducted in Quebec [

15] more than 90% of the professionals considered that the intranasal attenuated vaccine had been well received, both by parents and by themselves, and 57% rated the ease of administration very positively, a figure that was higher in our data (71%).

Another possible consequence of the preference for one vaccine over another is an eventual increase in vaccination rates in places where the vaccine is available. However, estimating the influence of the type of vaccine administered on the vaccination rate is complex, since this is influenced by multiple factors. In fact, the data available following the withdrawal of the intranasal vaccine in the US in the 2016–2017 season, which made it possible to estimate the evolution of vaccination rates compared to the previous season when the attenuated vaccine was available, are discordant. One study found no change in vaccination rates[

19], while another estimated a decrease of 1.6%, with a lower tendency to vaccinate in the second season among the most socially disadvantaged [

20].

Our work additionally addresses the acceptability of school vaccination among professionals in the Region of Murcia following a pilot study carried out in 24 schools. In this sense, school influenza vaccination programs have demonstrated an increase in vaccination rates as well as being a valid instrument for mass vaccination in countries such as the USA [

21,

22], overcoming one of the possible barriers, namely additional visits to the healthcare centre that require both time off work for the legal guardians and time off school for the children [

23]. Furthermore, it should also be considered that childhood influenza vaccination in Spain will mean almost one million additional visits to healthcare centres for children aged 6 to 59 months (estimating a vaccination rate of 60%), limited to the a short period of time of approximately 3 months (vaccination campaign estimated duration) based on the National Statistics Institute [INE] data [

24]), so incorporating alternative vaccination points can be very useful to avoid saturating the primary healthcare system. School vaccination programs have shown that the cost per dose of vaccine administered can be lower [

25] and can lead to cost savings when considering the cost of working hours lost by legal guardians for the vaccination of children [

26], and can therefore contribute not only to increasing accessibility and vaccination rates, but also to the efficiency of the system. Furthermore, according to a study published in Eurosurveillance in 2014 with data from the United Kingdom, in relation to vaccination against human papillomavirus in adolescents, the strategy of school vaccination also reduces inequities [

27]. Another advantage of school vaccination is that it allows early and rapid vaccination, allowing high vaccine coverage in the children to be vaccinated in just two weeks. This allows you to be prepared for when the flu epidemic season arrives. This is especially important in a epidemic disease that may present early, such as occurred in the United Kingdom in the 2019-20 season [

28].

In the Region of Murcia, school influenza vaccination was piloted during the 2022-2023 season in 24 schools. To this end, families were sent a letter with information on intranasal influenza vaccination and its contraindications, requesting consent from parents/legal guardians, and prior review of the medical records by the vaccination teams. In the first 4 centres evaluated, the vaccination rate was increased by 22.5% on a single day of school vaccination [

29], so it seems pertinent to obtain the professionals’ opinion before extending the program. When asked about the extension of the pilot program to the entire population of children aged 3 and 4 years with intranasal vaccine, almost 75 % agreed or strongly agreed (with greater support from doctors, 90 %, but also with significant support from nurses, 68.3 %), this support was greater among professionals who had participated in the pilot project, which may express that an initial "fear" is overcome after participation in school vaccination (86.4 vs. 72.7%,

p=0.03). These data are supported by the results of the logistic regression performed post-hoc, which confirmed the fact that giving a high importance to paediatric vaccination directly correlates with a favourable opinion of extending the pilot school vaccination throughout the Region of Murcia for the next season (OR =0.42). This analysis also highlighted the support from the medical group to the extension of the pilot program, with a correlation (OR) of 0,40, and the association between the participation in the pilot program and a favourable opinion towards the extension (OR=0.26). Similar studies have been conducted in the USA. The study conducted by Keane and cols showed less support from paediatricians than that seen in Spain, with 73% support for vaccinating children aged 24 to 59 months, which rises to 96 % for children aged 5 years and older[

30]. In another study, also carried out in a sample of responders from the American Academy of Pediatrics, paediatricians’ support was 86 %, although with differences depending on the children’s age and possible conditions of risk [

31]. In general, support from paediatricians in our setting is somewhat higher, which may be due to the use of the attenuated vaccine since the US surveys did not propose using only the attenuated vaccine in the school setting. In this regard, another study carried out in the USA associated the use of the attenuated vaccine in schools with an increase in vaccination rates, an increase in the speed of administration and children who were calmer during the process [

32].

For many years, adolescents have been vaccinated against meningococcal disease and human papillomavirus at school in the Region of Murcia, and, since 2008, in a protocolised manner [

33]. As a result of the protocolized school vaccination against the human papillomavirus in girls, some healthcare professionals (predominantly nurses) have traditionally demanded the presence of a paediatrician along with the nursing professionals in charge of school vaccination, and this survey was an excellent opportunity to address this issue. Our data revealed that 2 out of 3 surveyed healthcare professionals do not consider the presence of a doctor necessary, they consider it advisable but not essential, or they have a neutral opinion. As expected according to the line of opinion that had been observed in the nursing teams dedicated to school vaccination, , our data reveal that the presence of physicians is considered completely essential by a higher number of professionals withing the nursing group than the medical group themselves (38.2% vs. 17.1%) and vice versa; doctors are most likely to think that the nursing team can autonomously deal with school vaccination in comparison with nurses themselves (36.6% vs. 13.6%). This can be interpreted as an attempt by physicians to increase the competencies of nursing professionals, considering them sufficiently qualified to lead the vaccination autonomously, as well as a lower number of immediate adverse reactions expected as it is an intranasal vaccine. Probably, the need for the presence of a physician on the part of nursing comes from the previous experience of vaccination against the intramuscular human papillomavirus in adolescents, so these data are presented as a baseline, which will have to be returned to be studied in successive campaigns in which there is more experience in school intranasal influenza vaccination, to see if the presence of a doctor is considered equally or less necessary. In fact, when analysing the data among those who had or had not participated in the pilot, a tendency (not statistically significant) was observed to give less importance to the presence of a doctor in the vaccination. Other plausible hypothesis is that both groups of professionals are indeed saturated for assuming this new responsibility and they attempt to share this emerging task with other healthcare professionals, nursing considering school vaccination a task of the primary care team, of which doctors are also part.

In relation to the type of vaccine preferred for administration in the school environment, the results obtained are expected since, for the vast majority of professionals, the vaccine of choice should be the intranasal vaccine due to its ease of administration and being painless, which makes it possible to administer it to young children in schools without incidents.

Our work has several limitations. Firstly, the response rate was 29.7%, despite having sent the information three times, each separated by 7 days, which could mean that the respondents were particularly motivated. However, there are other studies carried out in the USA that had similar response rates [

14,

30], in addition to the fact that most of the literature consulted had similar or smaller sample sizes. Secondly, the study was conducted during the first season of influenza vaccination in the paediatric population in the autonomous community under study, so we do not have our own comparative data with respect to previous campaigns. To solve this second limitation, the study is being reproduced in this second influenza vaccination season. A third limitation of our work is that we do not have a history of vaccination against the influenza nor the willingness to be vaccinated against it. In different recently published papers it has been found that the willingness of health professionals to be vaccinated against influenza varies between 52 and 54.9% [

34,

35], which contrasts with the support for vaccination of the paediatric population of our study (91.9%). Nevertheless, we might consider this comparation cautiously, because the acceptance of self-vaccination and the recommendation of paediatric vaccination, may not be correlative. It might be reasonable to expect that the non-responders were less willing to support the vaccination, and therefore to refuse to participate in the study, nevertheless we consider that other reasons for not participating are more plausible such as high workload, lack of motivation to complete the survey or even forgetfulness. We believe that the simultaneous study of support for vaccination of patients and healthcare workers themselves is an interesting endpoint for future research since it may provide a different point of view to evaluate the healthcare professionals positioning regarding influenza vaccination.