1. Introduction

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) has established itself as the main resection method for large adenomas, superficial adenocarcinomas, and small size neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) [

1]. It has a steeper learning curve when compared to endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR), has higher curative rate and similar-to-higher rates of delayed bleeding and perforation [

2].

A recent meta-analysis suggests that prophylactic closure of colorectal mucosal defects after ESD could reduce the risk of delayed bleeding, effect seen only in observational studies, but not in randomized controlled trials [

3]. The European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) guidelines recommend against prophylactic coagulation of visible vessels and do not recommend routine closure of the colorectal wall defect [

2].

PuraStat is a synthetic self-assembled peptide gel that may be applied endoscopically on a bleeding site to achieve hemostasis. Although not recommended by current guidelines, the reported pooled rate for hemostasis is 93.1% and for rebleeding is 8.9% [

4,

5].

We aimed to assess the efficacy of clip closure and PuraStat application for clinically significant delayed bleeding (CSDB) after colorectal ESD.

2. Materials and Methods

We performed a post hoc analysis of a single-center prospectively maintained consecutive ESD registry (NCT06033976), with Hospital’s Ethical Committee approval (241564/01.04.2024). All patients diagnosed or referred to our department with non-pedunculated colorectal lesions above 20mm diameter in the period of January 2020 and April 2024 to whom ESD was deemed feasible were prospectively included. We have also included residual endoscopic or surgical lesions, and lesions bordering an anastomosis or the dentate line, even if smaller than 20mm.

Lesions were analyzed in white light and narrow band imaging (NBI) using either a high definition colonoscope for colonic lesions (CF H185L, Olympus, Japan) or a high definition gastroscope for rectal lesions (GIF H185 or GIF 2TH180, Olympus, Japan). Their macroscopic appearance was expressed according to Paris classification and as laterally spreading tumors (LST) if appropriate [

6,

7]. The surface of the lesion was examined and labelled according to NBI International Colorectal Endoscopic (NICE) classification [

1].

ESD was proposed for lesions classified as Paris Is or Paris IIa and NICE type 2 as well as NICE type 3 lesions in the lower rectum. Lesions classified as Paris Ip or Paris III or NICE type 1 were excluded. In addition, we performed complementary ESD of an endoscopic scar for possible residual neuroendocrine tumor (NET) after non-curative EMR.

Anticoagulants and antiaggregants were discontinued before procedure and resumed afterwards according to latest ESGE guidelines [

8]. A colloid solution was used for submucosal elevation (hydroxyethyl starch 500ml + 1ml adrenaline 1/1000 + 1ml methylene blue). Incision and submucosal dissection were done with ESD knives (Dual Knife J, IT Nano, Olympus, Japan) using electrocautery (ENDO CUT I and FORCED COAG modes, VIO 200D, ERBE, Germany). Hemostasis was done with knife and/or forceps (Coagrasper, Olympus, Japan). Snare resection was allowed, either to remove the lesion en-bloc at the end (hybrid ESD) or to remove a part of the lesion that could not be dissected (piece-meal).

At the end of the procedure, vessels within the resection bed were prophylactically ablated with Coaggrasper and any traces of blood within the colorectal lumen were thoroughly washed and aspirated. The resection bed was closed completely with metallic clips (Instinct Plus, Cook Medical, USA) or a hemostatic peptide gel was evenly applied onto the wall defect (PuraStat, 3-D Matrix, Japan) in most of the cases.

CSDB was defined as a post ESD bleeding necessitating a prolongation of hospitalization or readmission, with a new endoscopic evaluation or a blood transfusion and occurring at least 6 hours after the ESD [

9].

Patients with non-curatively resected malignant lesions underwent complementary surgery or chemoradiotherapy [

4].

Data recorded for categorical variables was expressed as absolute values and percentages. For normally distributed quantitative variables data was presented and as mean and standard deviation, or else median and intervals. Univariate analysis was done using Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and T test for quantitative variables if normally distributed, Mann-Whitney U otherwise. Odds ratio (OR) were presented with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). SPSS 29.0 software (IBM, USA) was used for statistical analysis.

3. Results

We included 40 patients with 41 colorectal ESD performed from 2020 to 2024. The characteristics of the patients and lesions are presented in

Table 1. Of the 22 lesions in the rectum, 5 were bordering the dentate line (2 of them residual after trans-anal surgery), one was contiguous to an ileo-rectal anastomosis, and one was a residual scar after a non-curative endoscopic rectal NET resection.

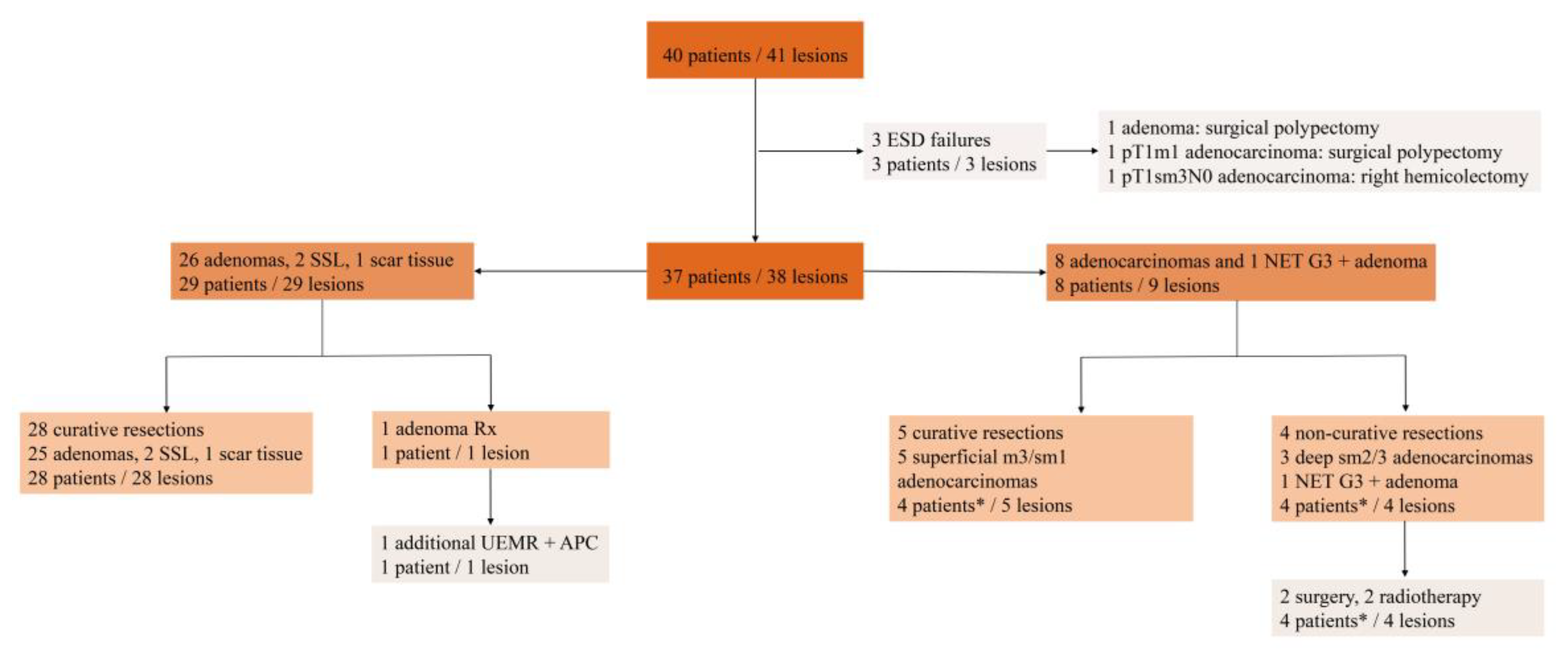

The flowchart of the patients and lesions is presented in

Figure 1. ESD failed in 3 patients who underwent curative surgical therapy in the same hospital admission: a large 100mm ascending colon adenoma and two colon adenocarcinomas exhibiting “muscle retracting sign”. One R0 resected 30mm ascending colon adenoma harbored a 4/7mm submucosal poorly differentiated (G3) NET (mixed adeno-neuroendocrine carcinoma).

ESD results are presented in

Table 2. There was one intraprocedural perforation for a curatively resected rectal T1m3 adenocarcinoma exhibiting “muscle retracting sign”, successfully managed conservatively by clip closure, antibiotics, and surveillance.

At the end of the procedure, the wall defect was closed completely with metallic clips in 14 lesions (36.8%), PuraStat was applied onto the resection bed in 18 lesions (47.4%), while the remaining 6 lesions had their post ESD wall defect untreated.

Clip closure was used more frequently in colonic lesions (12 of 16 colonic lesions vs. 2 of 22 rectal lesions, p < 0.001). Its use was not dependent on lesion diameter (clip closure 30 mm [20 – 60] vs. 37.5 mm [10 – 150], p = 0.482) and on the presence of anticoagulant therapy (clip closure in 2 of 8 patients with anticoagulant vs. 12 of 30 patients without, p = 0.684).

PuraStat was significantly more frequently applied in rectal lesions (16 of 22 rectal lesions vs. 2 of 16 colonic lesions, p < 0.001). It was also used in larger lesions (40mm [10 – 150] vs. 30mm [20 – 60], p = 0.167, not significant) and in patients with anticoagulant therapy (6 of 8 patients with anticoagulants vs. 12 of 30 patients without, p = 0.117, not significant).

There were 3 patients who experienced CSDB after ESD for rectal lesions, their details are presented in

Table 3.

4. Discussion

We have found a higher CSDB incidence of 7.9% (3 events out of 38 cases, 95% CI [1.7 - 21.4%]) versus 2.8 - 4.3% as reported by the ESGE ESD technical guidelines [

2]. Other authors have also found similar higher incidence of delayed bleeding, of 4.1 to 17.5% [

9]. We included only 3 patients with CSDB for whom endoscopic evaluation with hemostasis by thermocoagulation was necessary. Despite of our thoroughly washing any traces of blood from the colorectal lumen at the end of the procedure, three other patients with ESD for rectosigmoid lesions exhibited some minute quantity of diluted blood per rectum at 24 hours, which stopped spontaneously. These were not considered CSDB and were not included in the analysis.

Risk factors for CSDB after ESD have been included in predictive scores: the Korean risk score (rectosigmoid location, lesion diameter > 30mm, use of antiaggregants) and the Limoges score (rectal location, lesion diameter > 50mm, antiaggregants / anticoagulants, age > 75 and III or IV American Society of Anesthesiology (ASA) risk score) [

9,

10]. In our series, no predictive risk factors for CSDB were found in univariate analysis. Multivariate analysis by binary logistic regression was not performed as the number of events was small [

11]. However, all CSDB cases occurred after ESD for rectal lesions, but the association did not reach statistical significance.

A meta-analysis of on prophylactic clip closure after colorectal ESD (3 randomized controlled trials (RCT), 2 propensity score matched trials and 5 retrospective studies) has found a significantly reduced risk for delayed bleeding (17 events of 939 ESD with clip closure vs. 69 events of 1074 ESD without clip closure, odds ratio 0.3 95% CI [0.17 – 0.52]) [

3]. But the effect was not valid for the 3 randomized controlled trials included (2 events of 194 ESD with clip closure vs. 5 events of 207 ESD without clip closure, odds ratio 0.43 95% CI [0.08 – 2.28]). In our series, clip closure was mostly used for colonic lesions and was not protective for CSDB after ESD. Similarly, clip closure was not protective for CSDB in the large prospective cohort of colorectal ESD lesions validating the Limoges bleeding score (odds ratio 1.59, 95% CI [0.73 – 4.18], p = 0.26) [

9].

There are 4 prospective publications on PuraStat application for hemostasis and delayed bleeding prevention after colorectal ESD (3 observational non-comparative trials and one RCT) [

12,

13,

14,

15]. One team of authors published 3 of the 4 publications [

13,

14,

15], two of three reporting ESD and EMR cases without differentiating them (5 patients and 31 patients respectively, no delayed bleeding) [

13,

14]. There were only two events, one in an observational study (1 event in 15 ESD) [

12] and the other in a comparative study, measured as a secondary objective (1 event in 18 ESD with PuraStat application vs. 1 event in 25 ESD without PuraStat application) [

15]. In total, there were 2 delayed bleeding in less than 69 ESD with PuraStat application (the number include colorectal EMRs). In our study, PuraStat application was significantly more frequently applied for rectal lesions and were non-significantly more frequent after ESD for larger lesions and in patients with anticoagulant therapy. This may be the explain the fact that PuraStat, not only it was not protective for delayed bleeding in univariate analysis, but all events occurred in patients with PuraStat application (3 events in 18 ESD with PuraStat application vs. 0 events in 20 ESD without PuraStat application, p = 0.097). As stated, multivariate analysis could not be of help to define independent CSDB predictive factors.

To note that few patients with colorectal EMR and PuraStat use for delayed bleeding prevention are reported to date. One series reported 2 delayed bleedings in 17 patients (11.8% bleeding rate) [

16]. The two delayed bleeding cases were in the rectum, had a 50 mm diameter and were piecemeal EMRs.

The limitations of this paper are the small number of events and the selection bias for the prophylactic method (clip closure, PuraStat application). Nevertheless, the 3 events of our paper add up real-world data to the existing 2 delayed bleeding in patients with colorectal ESD and PuraStat application reported to date, with a total of 5 events in up to 107 colorectal ESD. A future individual participant data meta-analysis based on this data may be foreseen.

Limited data so far do not support yet the efficacy of PuraStat for delayed bleeding prevention after colorectal ESD. A randomized trial with delayed bleeding prevention as the main objective for PuraStat application after colorectal ESD is warranted.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.C; methodology, M.C.; software, D.C.L.; validation, D.M., A.T.; formal analysis, M.C.; investigation, M.C.; resources, D.B., A.G., A.G., E.T.; data curation, D.B.; writing—original draft preparation, M.C.; writing—review and editing, C.V.; visualization, M.C.; supervision, M.C.; project administration, M.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of “Prof. Dr. Agrippa Ionescu” Hospital, Bucharest, Romania (protocol code 241564 and date of approval 01.04.2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All research data can be found in Clinical Trials registry “Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection Registry (ESDREG)” (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT06033976).

Acknowledgments

Publication of this paper was supported by the University of Medicine and Pharmacy Carol Davila, through the institutional program Publish not Perish.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Pimentel-Nunes P, Libânio D, Bastiaansen BAJ, et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for superficial gastrointestinal lesions: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline - Update 2022. Endoscopy 2022; 54(6): 591-622. [CrossRef]

- Libânio D, Pimentel-Nunes P, Bastiaansen B, et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection techniques and technology: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Technical Review. Endoscopy. 2023; 55(4): 361-389. [CrossRef]

- Dong L, Zhu W, Zhang X, Xie X. Does Prophylactic Closure Improve Outcomes After Colorectal Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection? A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2024; 34(1): 94-100.

- Dhindsa BS, Tun KM, Scholten KJ, et al. New Alternative? Self-Assembling Peptide in Gastrointestinal Bleeding: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Dig Dis Sci. 2023; 68(9): 3694-3701. [CrossRef]

- Gralnek IM, Stanley AJ, Morris AJ, et al. Endoscopic diagnosis and management of nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage (NVUGIH): European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline - Update 2021. Endoscopy. 2021; 53(3): 300-332. [CrossRef]

- Participants in the Paris workshop. The Paris endoscopic classification of superficial neoplastic lesions: esophagus, stomach, and colon: November 30 to December 1, 2002. Gastrointest Endosc 2003; 58(6 Suppl): S3-43. [CrossRef]

- Kudo S. Endoscopic mucosal resection of flat and depressed types of early colorectal cancer. Endoscopy 1993; 25(7): 455-461. [CrossRef]

- Veitch AM, Radaelli F, Alikhan R, et al. Endoscopy in patients on antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapy: British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) and European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) guideline update. Gut 2021; 70(9): 1611-1628. [CrossRef]

- Albouys J, Montori Pina S, Boukechiche S, et al. Risk of delayed bleeding after colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection: the Limoges Bleeding Score. Endoscopy 2024; 56(2): 110-118. [CrossRef]

- Seo M, Song EM, Cho JW, et al. A risk-scoring model for the prediction of delayed bleeding after colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection. Gastrointest Endosc 2019; 89(5): 990-998.e2. [CrossRef]

- Pioche M, Camus M, Rivory J, et al. A self-assembling matrix-forming gel can be easily and safely applied to prevent delayed bleeding after endoscopic resections. Endosc Int Open. 2016; 4(4): E415-9. [CrossRef]

- Subramanian S, Chedgy, FJQ, Kandiah, K, et al. The use of a novel extracellular scaffold matrix for haemostasis during endoscopic resection in patients at high risk of bleeding: a little goes a long way. United Eur Gastroenterol J 2016; 2(Suppl. 1).

- Subramaniam S, Kandiah K, Thayalasekaran S, et al. Haemostasis and prevention of bleeding related to ER: The role of a novel self-assembling peptide. United European Gastroenterol J 2019; 7(1): 155-162. [CrossRef]

- Subramaniam S, Kandiah K, Chedgy F, et al. A novel self-assembling peptide for hemostasis during endoscopic submucosal dissection: a randomized controlled trial. Endoscopy. 2021; 53(1): 27-35. [CrossRef]

- Harris JK. Primer on binary logistic regression. Fam Med Community Health. 2021; 9(Suppl 1): e001290. [CrossRef]

- Soons E, Turan A, van Geenen E, et al. Application of a novel self-assembling peptide to prevent hemorrhage after EMR, a feasibility and safety study. Surg Endosc 2021; 35(7): 3564-3571. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).