1. Introduction

During the last two decades, financial inclusion (FI) has appeared as a cornerstone strategy for poverty alleviation and economic development (Ozili, 2020). This focus on FI is driven by various factors, including technological advancements, government initiatives, and private sector innovation. Growing evidence suggests that FI, when combined with technological advancements, effectively reduces poverty and stimulates economic growth (Diener et al., 2021).

The primary goal of FI is to enhance access to financial products and services such as savings and checking accounts, insurance, loans, and investment opportunities. By providing people with greater economic opportunities and financial security, FI helps to alleviate poverty and promote fuller participation in the economy (Mhlanga, 2021). Recognizing its potential, FI has become a priority for governments, international organizations, and development institutions aiming to foster economic growth and reduce inequality (Ozili, 2017).

Numerous steps have been taken to enhance FI. Primarily, the implementation of digital financial services, including mobile banking and digital wallets, has been instrumental in increasing access to financial services, particularly in underdeveloped areas (Naumenkova et al., 2019). Additionally, governments have initiated financial literacy programs to educate people on utilizing financial services and making informed financial decisions. Furthermore, private sector financial institutions play a significant role in improving access to credit through initiatives like microfinance and low-interest loans, enabling low-income individuals and small businesses to secure the funds necessary for growth (Ozili, 2017).

Researchers suggest that integrating technology can significantly boost FI. Existing studies demonstrate the significant impact of technological advancements on FI. The availability of mobile phones, the internet, and other advanced gadgets has facilitated easier access to financial services, even in remote and underserved areas, leading to a reduction in financial exclusion (Broby, 2021). Digital technologies have also driven the digital transformation of the banking industry, prompting changes in its services and products. This transformation has shifted traditional processes towards more streamlined digital systems, thereby reshaping the banking sector (Diener et al., 2021).

In line with the objective of digital transformation and the promotion of financial inclusion (FI) (Noreen, Shafique, Ahmed, & Ashfaq, 2023), authorities are embracing the entry of digital banks as a much-needed catalyst for competition and innovation within the banking industry. The widespread adoption of digital banking worldwide has been greatly influenced by digital technologies, which have empowered these banks to introduce new and innovative services for their customers. To facilitate the growth of digital banking, several authorities have established specific licensing regimes (Choi, 2020).

Digital banks are emerging as a welcome infusion of competition and innovation within the banking industry, leveraging digital technologies to provide novel services to customers. Operating as deposit-taking financial institutions, digital banks employ a digital-first or digital-only business model to deliver their goods and services. Offering faster, more convenient, and often more cost-effective services than traditional banks, digital banks bridge the gap between the financially privileged and the underserved, granting equal access to financial opportunities and bolstering economic growth through increased financial inclusion (Naumenkova et al., 2019). Financial inclusion is a key driver of economic growth, with digital banks leading the charge to make it a reality (Diener et al., 2021).

Moreover, digital banks frequently enjoy lower operating costs compared to their traditional counterparts, enabling them to provide more competitive products and services such as higher interest rates on savings accounts or lower fees. In essence, digital banks offer enhanced accessibility, convenience, and cost-effectiveness, rendering them increasingly crucial in the financial sector (Shin et al., 2020).

Existing literature on FI and digital financial services has mostly focused on the positive side of technological advancement in the financial industry. However, the other side of the coin tells a different story where the advent of new financial technologies, when inadequately regulated, may also hurt customers by increasing the financial risk (Moloi et al., 2020). FI through digital banking has the potential to empower millions of unbanked individuals, but it also poses significant risk management challenges.

Although digital technology has made remarkable progress in providing financial services to specifically in developing countries, some scholars, such as Njoroge, (2016), Kikulwe et al. (2014), and Mugambi et al. (2014) believe that digital customer protection remains a significant concern. Villasenor et al. (2015) have noted that the lack of transparency and instances of fraud involving mobile money operators and telecom companies have deterred some individuals from participating in the mobile money sector and using digital financial services. Additionally, the absence of interoperability among different digital payment platforms has raised concerns regarding the privacy and security of confidential information shared across fragmented versions of digital payments platforms (Mazer et al., 2017). Furthermore, the use of key technologies, such as short message services (SMS) and unstructured supplementary service data (USSD), on mobile phones has known security vulnerabilities that could be exploited to intercept digital banking transactions.

The World Bank (2012a, 2012b, 2012c) has also suggested that protecting consumers’ data while using digital financial services and providing users with adequate information and recourse mechanisms to resolve disputes is crucial for customer protection. The Alliance for Financial Inclusion (2014) has similarly emphasized the importance of safeguarding consumers from transaction risk and ensuring that they understand mobile money and digital financial products, which could enhance their trust and confidence in the digital financial systems, leading to higher adoption and usage (Budiyono et al., 2023).

The impact of digital banks on customers’ protection is complex, with both positive and negative elements. Digital banks offer increased convenience and reduce physical interactions, but they may have limitations in protecting the customers from the various types of risks associated with digital banks (Choi, 2020). Factors associated with digital banks can put customers at risk and erode trust in digital banking services. It’s important for digital banks to address challenges and prioritize customers’ protection to build trust and promote the adoption of digital banking. As digital banks expand FI by reeling in previously unbanked individuals and businesses, the question arises: what measures are in place to ensure that the risks are managed effectively? Therefore, there is a need to understand the intensity of the risk factors that are associated with digital banks.

Despite overwhelming research work on digital financial services and FI, clarity is required on the impact of digital banks on the customers’ protection (Naumenkova et al., 2019). One aspect that needs to be taken care of is customers’ protection. Digital banks are expanding access to financial services, but with this opportunity comes the need for effective risk management to protect both customers and the institution (Chen et al., 2021).

To the best of our knowledge, there are fewer studies focusing on this negative consequence of technological advancements in the finance industry and inclusiveness of digital financial services. Our study aims to add to this strand of literature and examine the impact of digital banks on customers’ protection. Furthermore, this study explains the intensity of risk indicators that influence customers’ protection while using digital financial services. The study aims to provide a more complete picture on the impact of digital finance advancements on customers’ protection. Our study is motivated by the need to promote prudent FI and to regulate digital financial markets. Despite the growing importance of digital financial services security in Pakistan, there is a lack of research on the specific digital risk factors that impact customer protection. To address this gap, this study proposes a framework that outlines five risk factors that can influence customer protection in Pakistan digital banks platforms. The factors identified include authentication mechanism, data privacy details, encryption mechanisms, information provided and responsiveness. The model was developed based on a comprehensive review of previous research in related areas (Muhtasim et al., 2022).

This study presents a new perspective on the factors that affect customer protection in the digital banking industry in Pakistan, particularly focusing on digital risk factors. The findings of this study could be valuable for digital banks policymakers, as it sheds light on the key risk factors that need to be improved to enhance platform security and encourage greater consumer adoption. In this study, we seek answers to the questions about the intensity of risk factors affecting customers’ protection while doing transactions with digital banks. The study aims to fill the gap in the literature on the understanding of various types of risks associated with digital banks and intensity of these risks on customers’ protection. The study adds to the literature on customers’ protection in the context of evolution of digital banks by taking a practice view of the situation of the digital financial services in Pakistan. Our findings have practical implications for risk managers, banking practitioners, digital banking customers and policymakers. This study applies structural equation modeling (SEM) by using SmartPLS for data analysis.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Financial Inclusion (FI)

FI gained significant attention in the 1970s, when the World Bank began promoting access to financial services as a means to reduce poverty. In 1997, the United Nations established the Microfinance Summit, which aimed to expand access to financial services to low-income populations. In the early 2000s, FI became a key topic of discussion among policymakers and international organizations, as it was recognized as a crucial tool for economic development and poverty reduction. In 2005, the G8 leaders established the Global Partnership for FI, which aimed to promote FI in developing countries (Ozili, 2020).

Similarly, in 2005, UNCDF also made a strategic shift to focus its interventions on FI more broadly. The new approach was supporting a market development approach to make financial sectors more inclusive. It was designed to create enabling environments for a wide range of retail financial service providers and to address gaps in the policy, legal, and regulatory constraints that prevent a financial sector from being inclusive.

The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP, 2006) defines FI as the provision of various formal financial services to customers, ranging from basic credit and savings services to more advanced services such as insurance and pensions (Wang’oo et al. 2013). The definition by Leeladhar (2006) spoke of FI as the process where banking services are delivered in a manner that they become affordable to many sections of the disadvantaged groups, especially the low-income earners. Thorat (2008) also came up with a definition of FI where FI is defined as how financial services are provided at an affordable rate by the formal financial institutions to the disadvantaged groups. The other definition of FI was provided by Sarma (2008) where FI was defined as the art of making sure that there is ease of access, availability, and the usage of formal financial services to all the people in the economy. Arun and Kamath (2015) also highlighted that FI should be viewed as a situation where people have access to financial services and products of good quality which are affordable and convenient with dignity for all the clients. According to a United Nations Report, FI is the sustainable provision of affordable financial services that bring the poor into the formal economy (Ozili, 2020).

2.2. Technological Advancements in Financial Sector

In recent years, technological advancements have played a significant role in promoting FI. Mobile banking, digital wallets, digital banks and other fintech innovations have made it easier and more affordable to access financial services, particularly for those living in remote or underserved areas. Overall, the history of FI shows a gradual recognition of the importance of providing access to financial services to all individuals, regardless of their income level or location. There is another school of thought that believes that financial innovation and technology can increase financial inclusion because they can bypass existing structural and infrastructural problems in order to reach the poor thus contributing to the realization of the Sustainable Development Goals (Saqib, Mahmood, Murshed, Duran, & Douissa, 2023). Financial innovation and technology have the potential to increase FI by overcoming some of the structural and infrastructural problems that have historically excluded the poor from accessing financial services (Mudimigh et al. 2020). Financial innovation is the process of creating new financial instruments, technologies, products and services to improve the delivery of financial services.

In a study, Ouma et al. (2017) show that financial innovations and technological advancements like the availability and usage of mobile phones were used to offer financial services that promote savings at the household level and improved the amounts saved, while Chinoda and Kwenda (2019) show that mobile phone innovation improved FI in 49 countries. In Southeast Asia, Mudimigh et al. (2020) observe that the region had a large number of Internet users and high number of Fintech companies which helped to improve the level of FI especially for the unbanked population.

Since this study is focusing enhancement of financial service via digital financial services, therefore; research adopts the school of thought who believe that financial innovation and technological advancement can increase FI. In line with focus on technological advancements and to promote FI, authorities are also welcoming digital banks. Over the past decade the world has seen a rise of digital banks. Digital banks have been on the rise as digital technologies transform financial services around the world. Another objective of setting up the digital banks is to provide credit access to unserved and underserved population. Further, digital banks also provide affordable/cost effective digital financial services. Government’s objective to setup digital banks is to encourage application of financial technology and innovation in the banking sector, foster new set of customer experience and develop digital eco-system.

2.3. Digital Banks

Globally, digital banks now number more than 100 and range from fully digital retail banks to marketplace banks to those that provide ‘banking-as-a-service’. Some prominent names of fully licensed and independently operating digital banks include: Japan’s Rakuten Bank (2000), Sony Bank (2001), and Jibun Bank (2008); Brazil’s Banco Original (2011) and Nubank (2013); UK’s Tandem (2013), Atom Bank (2014), Starling Bank (2014), Monzo (2015), and Revolut (2015); Germany’s N26 (2013) and SolarisBank (2016); China’s WeBank (2014) and MyBank (2015); Vietnam’s Timo (2015); Australia’s Volt (2017); and Israel’s Pepper (2017), Judo Bank (2018). Digital banks have grown on the back of falling trust in the traditional banking sector after the global financial crisis, advances in technology, and increasing demand from customers for lower-cost, more convenient and customer-friendly financial services (Choi, 2020).

Digital banks, also known as online banks or neo-banks, have become increasingly popular in recent years. These banks operate entirely online, without any physical branches, and offer their services through mobile apps and websites. The concept of online banking was first introduced in the 1980s and 1990s when traditional banks began offering electronic banking services to their customers. These services included online account access, bill payments, and money transfers. The first online-only banks, such as Ally Bank in the US and First Direct in the UK, were launched in the early 2000s. These banks offered competitive interest rates and low fees and were able to attract customers who were dissatisfied with traditional banks. The popularity of digital banks increased in the 2010s, with the launch of new online-only banks like Simple, Chime, and N26. These banks offered a more streamlined and user-friendly banking experience and used technology to provide personalized financial advice to their customers. In recent era, digital banks are becoming more mainstream, with traditional banks launching their own digital banking services to compete with the online-only banks. Many digital banks are also expanding their offerings beyond basic banking services, such as offering investment products and insurance (Choi, 2020).

Overall, the history of digital banks shows how technology has revolutionized the banking industry, and how consumers are increasingly turning to digital banking services for their financial needs. A digital bank, also known as an online bank or neobank, is a financial institution that provides banking services exclusively through digital channels such as mobile apps and online portals. Unlike traditional banks that have brick-and-mortar branches, digital banks do not have physical branches and operate entirely through digital platforms (Murinde et al. 2022).

According to the European Central Bank, “Digital banks refer to financial institutions that provide banking services primarily via digital channels, such as mobile apps or online portals, rather than through physical branches” (ECB, 2021). The Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC) in the United States defines digital banks as “financial institutions that conduct substantially all of their activities through the internet or other electronic channels with no physical presence” (FSOC, 2020)

According to the European Central Bank, “Digital banks refer to financial institutions that provide banking services primarily via digital channels, such as mobile apps or online portals, rather than through physical branches” (ECB, 2021). The Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC) in the United States defines digital banks as “financial institutions that conduct substantially all of their activities through the internet or other electronic channels with no physical presence” (FSOC, 2020).

While there is no standard definition of a digital bank, in this note we borrow the definition from Bank for International Settlements (BIS), digital banks are deposit-taking institutions that are members of a deposit insurance scheme, which deliver banking services primarily through electronic channels instead of physical branches.

2.4. Digital Risk and Customers Protection

Digital risk refers to the potential harm or negative impact that can arise from the use of digital technologies, including the internet, social media, and mobile devices. These risks can include cyber-attacks, data breaches, identity theft, fraud, and other forms of online crime. (Quach, et al. 2022).

Customer protection, on the other hand, refers to the measures that are put in place to safeguard the interests of consumers when using digital technologies. This can include regulations, policies, and practices designed to protect customer privacy, prevent fraud and other forms of online crime, and ensure that consumers have access to secure and reliable digital services (Niziot et al., 2021).

In his Restricted Access/Limited Control (RALC) theory, Moor (1997) emphasizes the need for strict controls to ensure privacy and prevent unauthorized access to personal information. Bongomin & Ntayi (2020b) argue that RALC provides a suitable framework for implementing online privacy policies that address privacy concerns related to digital transactions. Marano (2019) explains that digital customer protection is necessary to safeguard financial product users, including those dealing with digital financial intermediaries. According to Mazer et al. (2017), digital customer protection is a critical component of an inclusive financial system that promotes transparency and fairness to build confidence in formal financial services and providers. To measure digital customer protection variables, Bongomin & Ntayi (2020b) adapted items from previous studies by Malady & Law (2016), Mazer et al. (2017), and Park & Mercado (2018).

2.5. Theoretical Background

There are several theoretical frameworks that underpin the concept of FI, including the economic development theory, the financial sector development theory, and the social exclusion theory. These theories provide different perspectives on the drivers of FI and the role that financial services play in promoting economic growth and reducing poverty.

According to Beck et al. (2013), financial sector development is a critical driver of economic growth, and access to financial services is a key component of financial sector development. Digital banks, as financial institutions that offer banking services through digital channels, can expand access to financial services for underserved populations, including low-income households, women, and rural communities. Financial sector development theory suggests that the adoption of digital banking can lead to the development of a more inclusive financial system by expanding access to financial services for underserved and marginalized populations, including low-income households, women, and rural communities. Digital banking can also increase financial sector efficiency by reducing transaction costs and improving service delivery, leading to increased financial sector development and economic growth.

In addition to the above theories, Agency Theory suggests that FI initiatives must consider the incentives and motivations of different stakeholders, including financial service providers, regulators, and consumers, in order to effectively address associated risks (Akighir et al. 2022). Agency theory is a well-established economic theory that explains the relationship between principals (such as shareholders or owners) and agents (such as managers or employees) in an organization. This theory is relevant to understanding digital risks, which refer to the risks associated with the use of digital technologies, including cyber threats, data breaches, and other types of digital fraud. According to agency theory, conflicts of interest can arise between principals and agents due to differences in their objectives and incentives. For example, principals may prioritize long-term growth and profitability, while agents may focus on short-term gains or personal interests (Jensen et al. 1976). This divergence of interests can create information asymmetry and lead to agency problems, such as moral hazard and adverse selection.

Digital risks can exacerbate agency problems in several ways. For instance, the increasing reliance on digital technologies can create new vulnerabilities and expose Banks to cyber threats and data breaches. This can result in significant financial losses, reputational damage, and legal liabilities, which can undermine the long-term interests of principals. Moreover, digital risks can create incentives for agents to engage in opportunistic behavior or shirking, such as by intentionally exploiting digital vulnerabilities or neglecting cybersecurity measures (Stolowy et al., 2019). This can lead to moral hazard and adverse selection problems, as agents may prioritize their own interests over those of the principals. To mitigate agency problems associated with digital risks, principals can adopt various measures, including improved governance mechanisms, better alignment of incentives, and effective risk management strategies (Kumar and Singh, 2021). For example, Banks can implement robust cybersecurity policies, invest in cybersecurity training for employees, and establish clear accountability frameworks for managing digital risks.

2.5.1. Risk Management Theory

Plays a crucial role in the context of FI, as it enables the development and delivery of financial products and services that are tailored to the needs of underserved and marginalized communities. FI seeks to provide access to affordable financial products and services to those who are traditionally excluded from the formal financial sector, such as low-income households, women, youth, and small businesses. Effective risk management is essential for the sustainability of FI efforts, as it helps to ensure that these products and services are delivered in a responsible and transparent manner. This involves identifying and managing risks associated with the delivery of financial services, such as credit risk, operational risk, market risk, and liquidity risk (Ozili, 2017)

Risk management theory also explains that digital risks are an increasingly critical aspect of risk management in today’s digital age. Effective risk management requires a proactive approach that involves identifying potential risks, taking measures to mitigate them, monitoring for new threats, and communicating about cybersecurity risks. By adopting these strategies, organizations can better protect themselves against digital risks and ensure the security and integrity of their digital infrastructure (Moeller, 2007).

Risk management theory and agency theory lies in the fact that risk management can help mitigate agency problems by reducing information asymmetry and aligning the interests of principals and agents. By identifying and managing risks, organizations can ensure that they have adequate information to make informed decisions and reduce the chances of opportunistic behavior by agents. For example, effective risk management practices can help organizations identify and address cyber threats, data breaches, and other types of digital fraud, which are increasingly becoming a concern for principals.

Moreover, risk management can help reduce agency costs by providing incentives for agents to act in the best interests of the organization. For instance, if risk management is integrated into performance evaluation and compensation systems, agents may be motivated to engage in risk-reducing behavior and avoid excessive risk-taking, which can benefit the long-term interests of principals. Risk management theory and agency theory are closely related and can be interlinked to improve organizational performance and reduce agency problems. By integrating risk management into their governance and management practices, organizations can improve transparency, align incentives, and mitigate the adverse impact of uncertainty on their stakeholders

Similarly, according to Moor’s (1990 and 1997) theory of privacy known as “Restricted Access/Limited Control” (RALC), the establishment of private contexts or zones to limit others from accessing personal information requires strict control. To protect information in a given situation, privacy policies should restrict others from accessing that information, which in turn limits the control individuals have over their information. By adopting RALC, an online privacy policy can comprehensively address a broad range of privacy concerns related to digital transactions. Therefore, implementing RALC’s digital customer protection can create an environment conducive to transactions over mobile money platforms and promote FI.

There is a controversy in the existing literature, the extreme FI problem. Extreme FI occurs whenever access to the formal financial sector is granted to all individuals irrespective of their riskiness and income level. Extreme FI is one that opens the door to everyone so that everybody can access the formal financial sector. Extreme FI also grants financial access to convicts, criminals, hackers and fraudsters, too. Most FI studies suggest that access to finance should be granted to everybody and all barriers to financial access should be removed – but policy makers consider this to be extreme, at least in practice. Policy makers prefer the removal of some, not all, barriers to FI (Ozili, 2020). Digitalization and automation in financial services are major factors that must be addressed. Customers trust banks as a one-stop shop for their requirements because security and client protection are vital to them. However, in this digital banking era, the challenge is how far digital banking can be applied while maintaining the security of consumer transactions and the safety of customers (Kitsios et al., 2021).

Jayalath and Premarathne (2021) looked into the obstacles to digital transformation in Sri Lanka’s banking industry. They said that the banking and financial sector is one of Sri Lanka’s most competitive businesses and that as a result, the industry is facing hurdles in terms of digital growth. It was discovered that, in addition to other business development strategies, all established financial institutions are prioritizing digital transformations to achieve market diversification by developing new business opportunities while considering the generation effect with the help of emerging technologies (Jayalath & Premaratne, 2021). According to the survey, most institutions’ digital transformation projects have been hampered by a lack of a clear digital strategy, a failure to identify adequate process re-engineering needs, and a failure to pick optimum technology to offer digital business solutions. Defining a comprehensive digital strategy with strong leadership, transforming existing processes to be compatible with digital products and services, utilizing the most appropriate and cost-effective technology, customer engagement (Fatma & Khan, 2023), and customer service are just a few of the key factors that have a significant impact on delivering successful digital business solutions combining digital technology (Jayalath & Premaratne, 2021).

Yudi Kornelis (2022) investigated and studied the advancements and legal issues of customer protection in digital banking in Indonesia. It was discovered that digital banking and digital banking services have evolved and will continue to play an essential part in the future creation of a digital ecosystem. An “innovative and secure business; a prudent and sustainable digital banking business; adequate risk management aspects; governance and IT capability requirements for digital bank directors; customer protection of personal data and the risk of data leakage; and the contribution of digital banks to the development of the digital financial ecosystem” are among the challenges in implementing digital banking.

According to the Consultative Group to Assist the Poor (CGAP, 2017), mobile money service providers can increase the adoption of their services by offering comprehensive fraud awareness and prevention programs to sensitize consumers, staff, and agents on fraud trends and prevention measures. Similarly, Mazer et al. (2017) discovered that revealing loan terms and conditions to borrowers using KopaCash, a mobile money service provided by Jumo, in Kenya resulted in lower default rates among borrowers.

2.6. Framework and Hypotheses

Past research has shown that risk management plays a significant role in shaping customer protection while using digital financial services, but these studies have examined risk management as a general concept without identifying specific security factors unique to Pakistan’s digital banks. Consequently, the present study has proposed a risk indicators framework that includes authentication mechanism, encryption mechanisms, data privacy details, responsiveness and information provided, with each factor considered as a separate variable in the research.

Authentication Mechanism

Authentication is a crucial process that ensures the user’s identity is verified, and the activity being carried out is performed by a legitimate individual, thus minimizing the risk of identity theft. For instance, users are often required to verify their identity by entering a one-time password (OTP) to complete payment transactions. Authentication plays a vital role in shaping the user experience, and thus their decision to adopt digital wallets (Cheah et al. 2021). As trust is a crucial factor, it is essential for digital wallet providers to regulate relevant aspects such as authentication to ensure that customers feel confident and secure when using their services (Bhatt, V. 2020).

Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 1 (H1). Strong authentication mechanism has a significant positive impact on customers’ protection in digital banks.

Data Privacy Details

The restricted access/limited control (RALC) theory of privacy by Moor (1990 and 1997) posits that in setting up contexts or zones of privacy to limit or restrict others from access to one’s personal information, strict control should be implemented. The privacy policies that protect information in a particular situation by normatively restricting others from accessing that information provide individuals with limited controls. The adoption of RALC helps to frame an online privacy policy that is sufficiently comprehensive in scope to address a wide range of privacy concerns that arise in connection with digital transactions. Thus, the adoption of digital customer protection stipulated under the RALC can create conducive environment for transactions over the digital financial services platform to promote FI. Ozili (2018) observes that the wide use of digital technologies such as digital financial services increases the pervasiveness and scale of cyber-attacks that pose significant threat to the security and privacy of customers’ data on the digital channels. Similarly, customers’ awareness that their data is prone to cyber-attacks has made them lose trust in the digital channels to perform their transactions.

Privacy details refer to the information collected from customers by digital services, including private information used for registration purposes and authentication mechanisms. Several previous studies have found that the ability of digital banks to maintain customer privacy significantly impacts customer satisfaction and protection.

In today’s digital age, customers are increasingly aware of the importance of protecting their personal data. Digital banks that prioritize privacy and data protection through measures such as strong encryption, multi-factor authentication, and regular security audits can attract and retain customers who value the security of their information (Wewege et al. 2020). Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 2 (H2). Privacy and data protection have a significant positive impact on customers’ protection in digital banks.

Encryption Mechanisms

The process of encrypting data involves specific steps and procedures to safeguard information and prevent unauthorized access from third parties or hackers. This is done by converting data into a gibberish form that can only be decrypted using a unique key or mechanism that corresponds to the encryption method used. (Phuong et al. 2020). Encryption mechanisms are crucial in protecting financial institutions’ server systems from breaches by hackers. By ensuring the security of electronic payments, encryption mechanisms play a significant role in increasing consumer confidence in conducting transactions online. (Phophalia et al. 2018)

Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 3 (H3). Proper encryption mechanism has a significant positive impact on customers’ protection in digital banks.

Information provided

According to Ozili (2018), the widespread adoption of digital technologies like mobile money has led to an increase in the prevalence and magnitude of cyber-attacks, which pose a substantial risk to the security and privacy of customer data on digital platforms. Consequently, customers have become increasingly aware of the vulnerability of their data to cyber-attacks, leading to a loss of trust in digital channels for conducting transactions.

Digital wallet services can enhance customers’ knowledge about security by providing relevant information. When digital wallet users are informed of security procedures, they may feel more assured about the safety of the system. Conversely, if customers are unaware of security measures, they may not trust the digital wallet service. Furthermore, having knowledge about digital payments services has a positive and significant effect on customers’ continued use of digital wallets. Therefore, the security information shared by digital wallet services can help customers become more knowledgeable about security and boost their confidence in the system (Akhila, 2018). Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 4 (H4). Information provided has a significant positive impact on customers’ protection in digital banks.

Responsiveness

Toor et al. (2016) state that being responsive to customers, displaying a willingness to assist them, and offering prompt services are all elements of responsiveness. These factors ultimately contribute to achieving customer satisfaction which leads to customer protection.

According to the Consultative Group to Assist the Poor (CGAP, 2017), mobile money providers can significantly increase the uptake of their services by offering comprehensive fraud awareness and prevention programs to sensitize consumers, staff, and agents on fraud trends and prevention measures. A study by Mazer et al. (2016) found that disclosing loan terms and conditions to borrowers using KopaCash offered by Jumo mobile money in Kenya resulted in reduced defaults among the borrowers.

Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 5 (H5). Responsiveness has a significant positive impact on customers’ protection in digital banks.

The conceptual framework is summarized below

2.7. Conceptual Framework

3. Data and Methodology

3.1. Study Design and Approach

For this study, a cross-sectional design was employed along with a quantitative approach to gather responses from selected participants. The aim was to investigate how various risk parameters affect customer protection in the context of using digital financial services. We started by searching for literature in popular databases such as Scopus, Google scholar etc. We selected 1012 relevant research papers. After applying the PRISMA search strategy (preferred reporting elements for systematic reviews and meta-analysis, 37 literature sources were selected.

In order to categorize and organize the findings and results, we reviewed the results, identified duplicates, and used the inclusion and exclusion criteria. We generated tables of research papers (n = 37) based on their classification, allowing us to organize them. Manually comparing and contrasting search lists was performed. By referring to the inclusion/exclusion criteria, we were able to eliminate studies that did not fit our review’s objectives from the search and also discard repeated search items. Our search criteria were determined based on an analysis of the study objectives and a brainstorming session with peers to find the best words to describe the search. We set the search parameters at a high level and used the generic best-fit phrases, which led us to a number of sources. It was understood that if the initial search did not yield significant results, a narrower syntax would be commissioned. We achieved the most relevant search by implementing a specific syntax, after which we narrowed it to digital financial services and customers’ protection.

3.2. Instrumentation, Measures of Variables and Data Collection

The variables of authentication mechanism, encryption mechanisms, data privacy details and information provided were measured using items that were adapted and modified from Muhtasim et al. (2022) and the variable of responsiveness was measured using the items that were obtained and modified from Kaur et al. (2021). Besides, customer protection was measured using items obtained and modified from Bongomin, G., & Ntayi, J. M. (2020b).

3.3. Data Collection Procedure

To collect data to examine the impact of various risk factors on customer protection while using digital financial services, we created a survey. The survey consisted of 36 statements. First section of the questionnaire is relating to the respondents’ age, gender, occupation. The respondents were asked to respond to the 36 statements using a five-point Likert scale in which ‘5’ = Strongly Agree, ‘4’ = Agree, ‘3’ = Neutral, ‘2’ = Disagree, ‘1’ = Strongly Disagree.

A structured survey was conducted to gather data from customers of various banks who use digital banking services in Pakistan. The survey yielded 250 valid responses, which, as per Hinkin’s (1995) recommendation, is an optimal sample size for performing structural equation modeling. Hinkin suggests that the item to response ratio should range from 1:4 to 1:10 for each scale analyzed, which translates to 120-300 responses (Deb and Lomo-David, 2014; Hinkin, 1995).

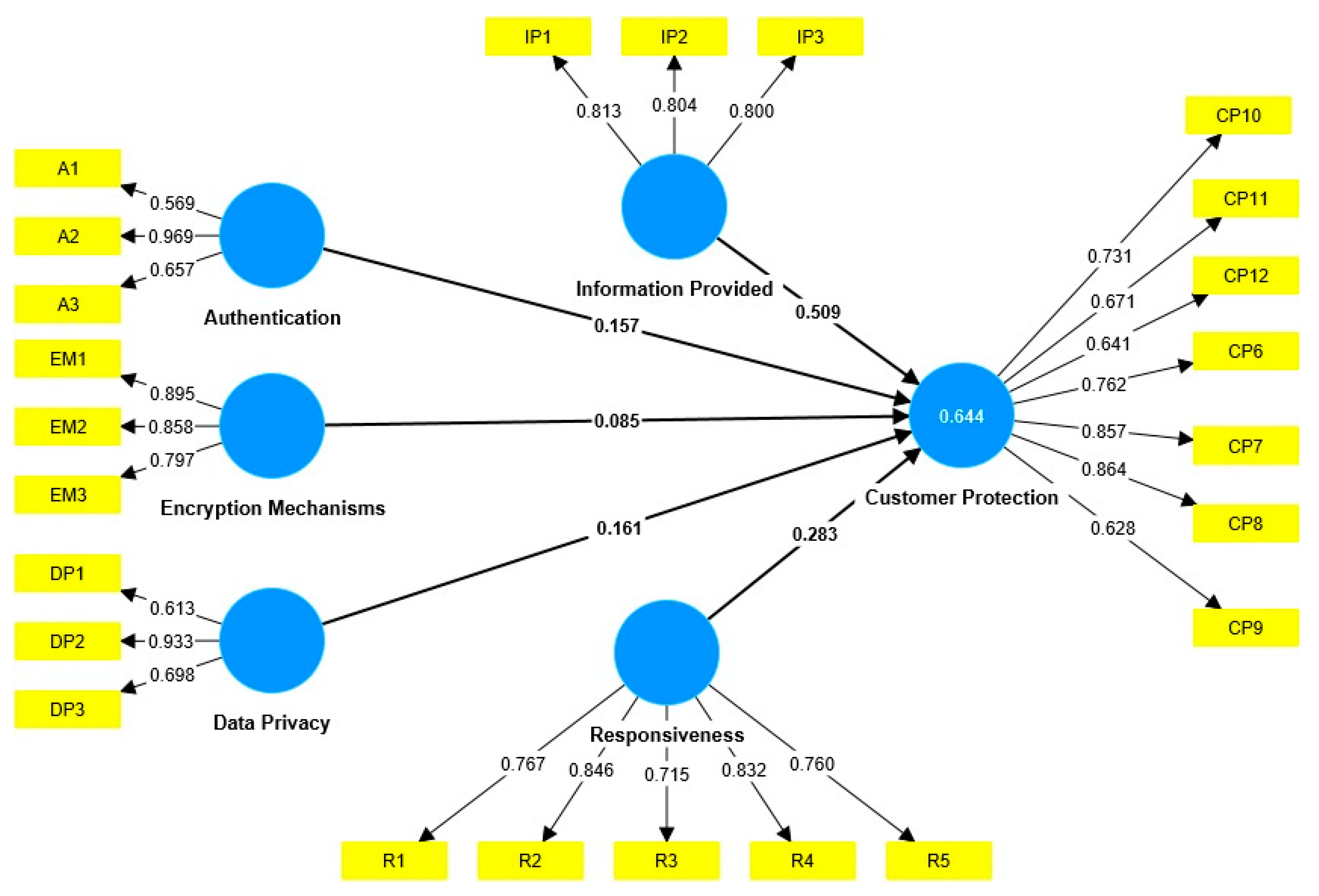

To analyze the data collected, we first used Microsoft Excel to calculate descriptive frequencies of the participant demographics. Afterwards, we employed Smart PLS (Partial Least Square), a structural equation modeling tool, to examine the relationship between the variables (Fair treatment of customers, Transparency, Privacy and data protection, Security, Complaints handling and dispute resolution, and Responsible business practices) and their impact on customer protection when using digital financial services in Pakistan.

5. Discussion & Conclusion

5.1. Discussion

The aim of this study was to offer a fresh perspective on the factors influencing customer protection in the digital banking sector in Pakistan, with a specific emphasis on digital risk factors. The subsequent discussion centers on the hypotheses generated within this study.

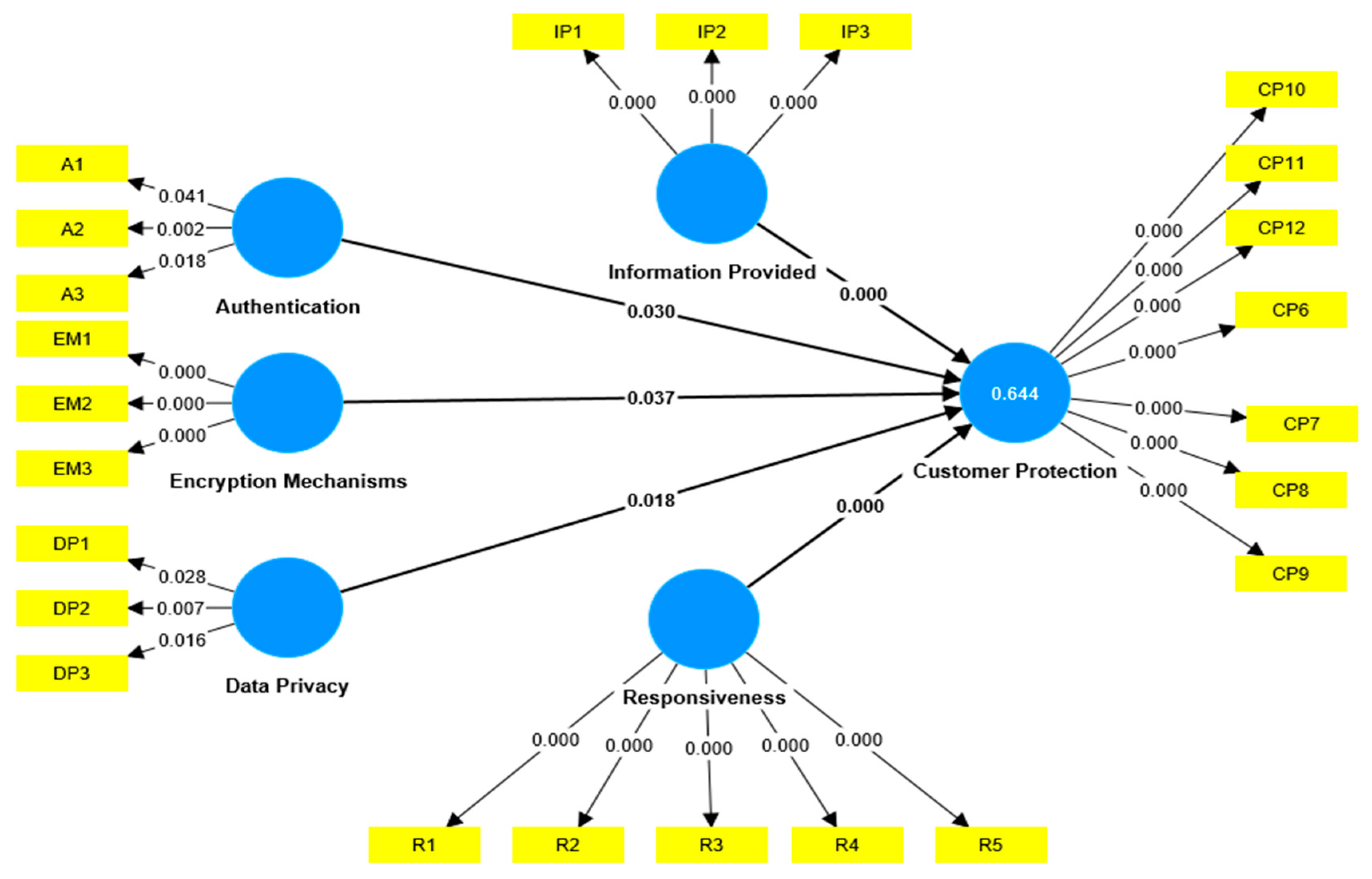

The examination of hypotheses indicates that the p-value for the positive influence of a robust authentication mechanism on customer protection when utilizing digital banking services is 0.030, which is below the threshold of 0.05. Therefore, H1 is supported. Consequently, it can be concluded that the adoption of a strong authentication mechanism by digital banks has a significant positive impact on customer protection. The findings imply that customers are more inclined to utilize digital financial services when the authentication process is robust and secure. Based on the survey results, a secure authentication process is likely to alleviate security concerns among users of digital financial services.

Furthermore, the p-value for the impact of robust data privacy controls on customer protection is below 0.05, specifically 0.018. Consequently, H2 is also supported, indicating that data privacy exerts a significant positive influence on customer protection in the context of digital financial services. This finding underscores the fact that users of digital banking services place great importance on the privacy of their data, which in turn affects the level of customer protection within the digital financial system. In today’s digital era, customers possess an increased awareness regarding the significance of safeguarding their personal data. Digital banks that prioritize privacy and data protection through measures such as robust encryption, multi-factor authentication, and regular security audits can attract and retain customers who value the security of their information.

Moreover, the p-value for the correlation between encryption mechanisms and customer protection is 0.037, indicating its significance at a level below 0.05. Hence, H3 is also supported, highlighting the substantial positive impact of encryption mechanisms on customer protection within the realm of digital banking. The survey respondents express their concerns regarding the acceptance or rejection of digital financial services based on the presence of encryption mechanisms. Similarly, participants believe that the implementation of strong encryption mechanisms serves as a preventive measure against the misuse or unauthorized access of user information when utilizing digital financial services.

Based on the table presented above, H4 is also substantiated as the p-value for the impact of information provided is 0.000, which is less than 0.05. Thus, it can be inferred that the information provided holds a significant positive influence on customer protection. The findings highlight that the information disseminated by digital financial service providers enables users of digital banking to gain a better understanding of security measures. The provision of additional security information enhances the credibility of online payment systems. Moreover, when consumers are aware of the software performance, they feel more assured about the security of the digital banking system. Consequently, the study concludes that the proposed security factors significantly impact customer protection within digital banks, based on the hypotheses that were tested.

The p-value for the impact of responsiveness on customer protection is 0.000, which is below the significant level of 0.05. Therefore, H5 is supported, indicating that being responsive to customers in digital banks has a significant effect on customer protection. The findings validate the expectation of digital banking users that financial service providers should demonstrate a willingness to assist them and provide prompt services. These factors ultimately contribute to customer satisfaction, which in turn enhances customer protection.

5.2. Conclusion

The present study has introduced a comprehensive security framework consisting of five factors that impact customer protection when utilizing digital financial services in Pakistan. In conclusion, all the factors proposed in this research exhibit a significant positive influence on customer protection. The analysis reveals that the information provided holds the greatest significance in influencing customer protection within digital financial services, followed by responsiveness, data privacy, authentication, and encryption mechanisms. Therefore, the implementation of enhanced information security management principles is crucial for the progress and development of the digital banking industry in Pakistan.

In recent years, digital banks have experienced a surge in popularity due to their provision of convenient and cashless digital financial services for daily payments and transactions. However, limited research has been conducted to systematically consider and derive security factors during the development of digital financial payment systems. Without a comprehensive understanding of these security factors, the progress of the digital banking industry may be hindered. This study aims to fill this research gap by exploring and identifying specific security factors that are crucial for digital financial service providers. Notably, these factors have not been previously analyzed in the context of customer protection, making this research contribution unique and valuable. Therefore, this study significantly enhances the theoretical literature surrounding digital banks by shedding light on previously unexplored security factors.

Customer protection is of utmost importance for the thriving digital banking industry. As the prevalence of hackers and fraudulent activities continues to rise, it is imperative to enhance the security of digital financial services. The findings of this research can serve as a valuable resource for digital financial service providers, enabling them to strengthen their system security and prioritize key security factors that contribute to enhanced customer protection within digital banks. Furthermore, this study can provide valuable guidance to future researchers who intend to delve into this field by considering the variables proposed and examined in this study.

While our study has provided valuable insights, it is important to acknowledge its limitations. Despite achieving a satisfactory response rate for our survey, it is crucial to recognize that the respondents represent only a subset of customers in Pakistan. In order to broaden the scope of research and facilitate comprehensive discussions on customer protection in the context of digital financial services in Pakistan, it would be advantageous to attract a more diverse pool of customers from various regions within the country. Furthermore, future research endeavors could explore the factors that influence customer preferences in different countries, such as the level of economic development, literacy and other relevant socio-cultural aspects. Such investigations would be intriguing and offer valuable comparative insights into the digital banking industry across diverse national contexts.

5.3. Policy Implications

The establishment of digital banks is a significant stride towards promoting FI. To ensure the success and security of digital financial services, it is crucial for the promoters of such services, as well as regulators, to focus on reinforcing the existing customer protection laws applicable to digital banking platforms. This necessitates a collaborative approach involving fintech companies, financial institutions, and regulatory bodies. By collectively strengthening the laws against digital banking fraudsters, a robust framework can be established to deter and penalize those involved in fraudulent activities within the fintech ecosystem. Additionally, it is essential to establish an efficient mechanism for recourse, compensation, and remedies to benefit the victims of frauds and cybercrimes in digital banking. Implementing stringent laws and imposing appropriate legal consequences on individuals found guilty of digital banking fraud will further contribute to safeguarding the interests of customers and maintaining the integrity of the digital banking industry.