Acne Vulgaris is a common cutaneous disorder prevalent in 35 - 90% of young adults [

1]. This inflammatory condition involves hormonally responsive sebaceous glands characterized as chronic or recurrent papules and pustules. Acne has the potential to cause hyperpigmentation and scarring, showcasing its ability to not only be medically important but also exacerbate psychosocial affects for a patient [

1]. Acne Vulgaris has an array of complex factors that influence its condition, including genetics, hormones, and hygiene practices. However, the heritability of acne fails to explain its prevalence of over 80% in western countries [

2]. This brings into question the fact that despite the wide spread of knowledge in different causes of acne, diet intake, particularly dairy is often overlooked, highlighting the significant importance of diet as a critical link to acne. Previous research has demonstrated that a patients’ dairy intake, regardless of amount and frequency were associated with higher odds ratio for acne in individuals aged 7-30 years compared to their counterparts that had no dairy intake [

2]. Dairy’s ability to cause an increase in acne flares is through its milk-derived amino acids, promoting insulin secretion and inducing hepatic insulin-like growth factor-1 that in result stimulates follicular epithelial growth and keratinization, increasing susceptibility to acne severity [

2].

Even with research linking diet to increase in acne severity, current treatment modalities focus on the usage of topical and systemic treatment formulations. Dermatologists typically begin their treatment plan by prescribing topical therapies such as retinoids and benzoyl peroxides, before taking the next step towards oral tetracyclines and spironolactone [

3]. For patients that experience severe acne that is unresponsive to the following medications, oral isotretinoin is prescribed [

4]. Isotretinoin works by reducing the sebum production in sebaceous glands [

4]. However, despite its high success rate, it is associated with severe side effects, thus patients and providers should use with caution [

4].

Although medications have been proven efficacious, the current body of research falls short in acknowledging diet modifications as an effective treatment plan. Altering a patient’s diet can provide a cost-effective and advantageous way to improve patient acne severity along with prescription medication usage. The lack of research in dairy elimination as a beneficial treatment modality hinders the ability for healthcare providers to educate patients in adopting a healthy diet to contribute to their acne resolution. This case report aims to shed light on the significant improvement of patient acne severity through dairy elimination. By examining this case study, we hope to bring awareness for healthcare providers to propose new avenues for acne treatment to enhance acne outbreaks and symptoms, improving severe resistant nodular acne and patient treatment quality.

2. Case Presentation

A 26-year-old Caucasian female, with a 15-year past medical history of cystic acne vulgaris, began to report having an onset of coinciding gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms of abdominal pain/diarrhea with severe flareups of acne breakouts for several months following the intake of certain foods. The patient reported concerns that the increase in these symptomologies correlated with consumption of inflammatory foods such as dairy, fried foods, butter, olive oil, and seed oils. These symptoms were also reported in her father, furthering her concern for the linked symptoms. In addition to the abdominal pain and diarrhea, the patient also described an intense pruritic rash that spanned across her face, scalp and shoulders that occurred simultaneously. A few days following the rash outbreak, the patient experienced an emergence of erythematous cystic acne with a predilection for the jawline, forehead, and scalp. When the patient consulted her dermatologist with these concerns of her linked symptoms, they were unaware of how to specifically target her acne in relation to her specific food consumption. The dermatologist stated that there was a little correlation to diet and acne and suggested these findings were a result of hormonal changes.

During the patients’ time diagnosed with acne vulgaris, she was treated with various treatments including chemical peels, facials, tetracycline and topical tretinoin. Many of these strategies temporarily relieved her symptoms but failed to cure her continual severe outbreaks following dairy consumption. After trying these different treatments, the dermatologist recommended a six-month treatment of oral Isotretinoin that drastically improved the patient’s skin. However, despite the vast improvement of her cystic, she continued to experience rash outbreaks and nodular acne following the consumption of dairy products, making her stubborn acne flareups difficult to eradicate.

3. Case Management and Outcomes

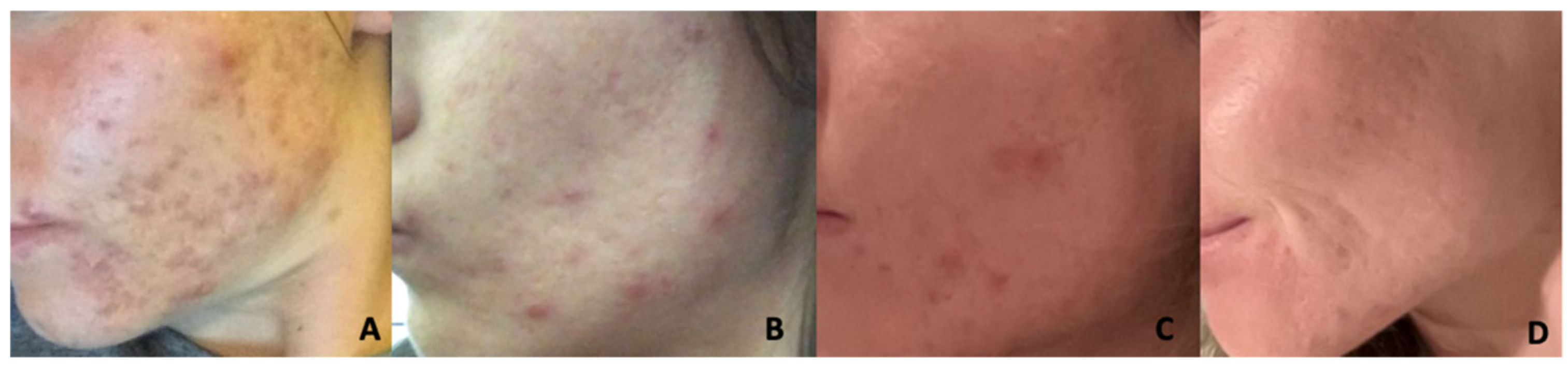

Following fourteen years of the diverse array of treatments, the patient maintained an acne photograph diary and soon discovered that the only prescription that prevented her GI and acne breakouts was maintenance of a strict diet avoidant of food high in saturated and trans-fat foods. The patients’ healthy diet consisted of substituting butter for avocado oil and noticed a resolution of facial pruritis after only a single day of clean eating and a resolution her acne outbreak within two weeks. The patient has been currently maintaining a diet void of fatty meals for the past 6 years. She focuses on incorporating many anti-inflammatory foods such as vegetables, grilled meats, fresh fruit, and minimally processed snacks. While regulating her diet, the patient also uses the Face Reality acne line, consisting of an ultra-gentle cleanser, moisturizing toner, hypochlorous acid face spray, 11% I-mandelic serum, 5% Benzol peroxide acne med, hydra balance hydrating gel, a cran-peptide moisturizing cream, and SPF 28 twice a day to help control breakouts. Additionally, she partakes in a Omnilux LED red light therapy mask once a day to control inflammation. Through these lifestyle changes the patients’ outbreaks have been more stable and demonstrate an improvement in erythema and pain (

Figure 1).

4. Discussion

Although the potential treatment of cystic acne through diet restrictions requires further research, this case study demonstrates diets’ ability to aid individuals grappling with Acne Vulgaris. Existing literature that provides our current understanding of the interplay between diet and acne emphasizes the pathogenesis of high glycemic load and dairy intake through signaling pathways of insulin/insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) and mTORC1 9 [

5,

6]. Although these findings provide background on the relationship between diet and acne, more recent research in applying these findings to patients seeking treatment has failed to be addressed. This report emphasizes how diet can be used to provide symptomatic improvement of acne through restriction of dairy. The significant observational improvement seen in

Figure 1, showcasing decrease nodular outbreaks and erythema, alongside the patient’s reported satisfaction, sets the stage for new avenues in Acne Vulgaris treatment. This warrants further exploration in examining the elimination of dairy as a viable solution to cystic acne.

5. Dermatologist Role

Improved dialogue collaboration between healthcare providers, nutritionists and patients is becoming vital due to the possible treatment of acne through diet. Altering a patient’s diet can be difficult, however, it plays an important role in treating acne holistically. Healthcare providers, particularly dermatologists, should actively participate in educating patients about the potential impacts of dietary choices on their skin conditions. Educating patients on the benefits of eliminating dietary irritants, such as dairy, and maintaining a healthy diet can have a curative benefit in acne treatment. Additional research on the relationship between diet and acne could increase patients’ options for cost-effective methods to tackle their recurrent cystic acne and give dermatologists new dialogue to converse in with their patients about additional treatment avenues.

6. Future Implications

Addressing the link between acne and diet restrictions can potentially impact the approach to acne treatment. Previous studies have hinted at the pathogenesis of acne being altered through personalized dietary interventions, however, there has been a lack of clinical research analyzing data on patients’ acne in relation to their dietary intake [

5,

6]. Although this patient report clearly indicated a deep-rooted connection between dairy elimination and her acne improvement, this must also be examined in a larger patient population. The future implication of this knowledge is opening doors to further research in this field, and a possible new option for acne treatment for patients.

7. Limitations

While our case study and the referenced literature provide valuable insights, it is crucial to acknowledge the limitations. Melnik’s study may be deemed as outdated and primarily focuses on the Western diet a, therefore the generalizability of these findings to individuals with different dietary habits remains an area for further investigation. Additionally, as with any observational study, confounding variables and the potential for recall bias need consideration when interpreting the results.

8. Conclusions

The findings reported in this case study alongside previous research, highlight the need for an improved understanding of the relationship between the consumption of dairy and acne vulgaris. Our patient’s ability to decrease her facial erythema and outbreaks by eliminating dairy could be a viable option for other patients interested in alternative treatment options. As we move forward, it is important for providers to acknowledge the interplay between acne and diet as a contributing factor in acne flare-ups. The evidence from this study calls for continued research to refine our understanding and improve patient outcomes in the management of acne through dietary interventions.

Author Contributions

All authors participated in the conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing; supervision, Benjamin Brooks. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of ROCKY VISTA UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF OSTEOPATHIC MEDICINE (protocol code #2023-292 01/12/2024)

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient to publish this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

Elizabeth Tchernogrova is both an author and the subject of the case presentation described in the research paper. The authors declare no further conflicts of interest.

References

- Acne vulgaris: Management of moderate to severe acne in adolescents and adults. UpToDate. Accessed December 18, 2023. https://www-uptodate-com.proxy.rvu.edu/contents/acne-vulgaris-management-of-moderate-to-severe-acne-in-adolescents-and-adults?search=treatment+for+acne+vulgaris&source=search_result&selectedTitle=3~150&usage_type=default&display_rank=3#H2037856433.

- Pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, and diagnosis of acne vulgaris. UpToDate. Accessed December 18, 2023. https://www-uptodate-com.proxy.rvu.edu/contents/pathogenesis-clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis-of-acne-vulgaris?search=diagnosis+of+acne+vulgaris&source=search_result&selectedTitle=2~150&usage_type=default&display_rank=1.

- Sutaria AH, Masood S, Saleh HM, et al. Acne Vulgaris. [Updated 2023 Aug 17]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459173/.

- Pile HD, Sadiq NM. Isotretinoin. [Updated 2023 May 1]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK525949/.

- Juhl, C. R., Bergholdt, H. K. M., Miller, I. M., Jemec, G. B. E., Kanters, J. K., & Ellervik, C. (2018). Dairy Intake and Acne Vulgaris: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of 78,529 Children, Adolescents, and Young Adults. Nutrients, 10(8), 1049. [CrossRef]

- Melnik, B. C. (2015). Linking diet to acne metabolomics, inflammation, and comedogenesis: An update. Clinical, Cosmetic and Investigational Dermatology, 8, 371–388.

- Bowe, W. P., & Logan, A. C. (2018). Acne vulgaris, probiotics and the gut-brain-skin axis: From anecdote to translational medicine. Beneficial Microbes, 9(2), 171–183.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).