1. Rare Earth Elements (REEs): an Introduction and Their Uses

Juhan Gadolin, a Finnish chemist at Abo Akademi University (Turku) in Finland, conducted the first research on, recorded, and named the rare earth elements (REEs) in 1794 [

1]. The consistency of the supply of rare earth elements (REEs) has received a lot of attention lately. The rare earth elements (REEs) are defined by the periodic table and the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) as a group of 17 metallic elements, which include Yt, Sc, and 15 lanthanides. Except for Sc, the majority of REEs are found in lanthanide element-containing ore deposits in nature [

2].

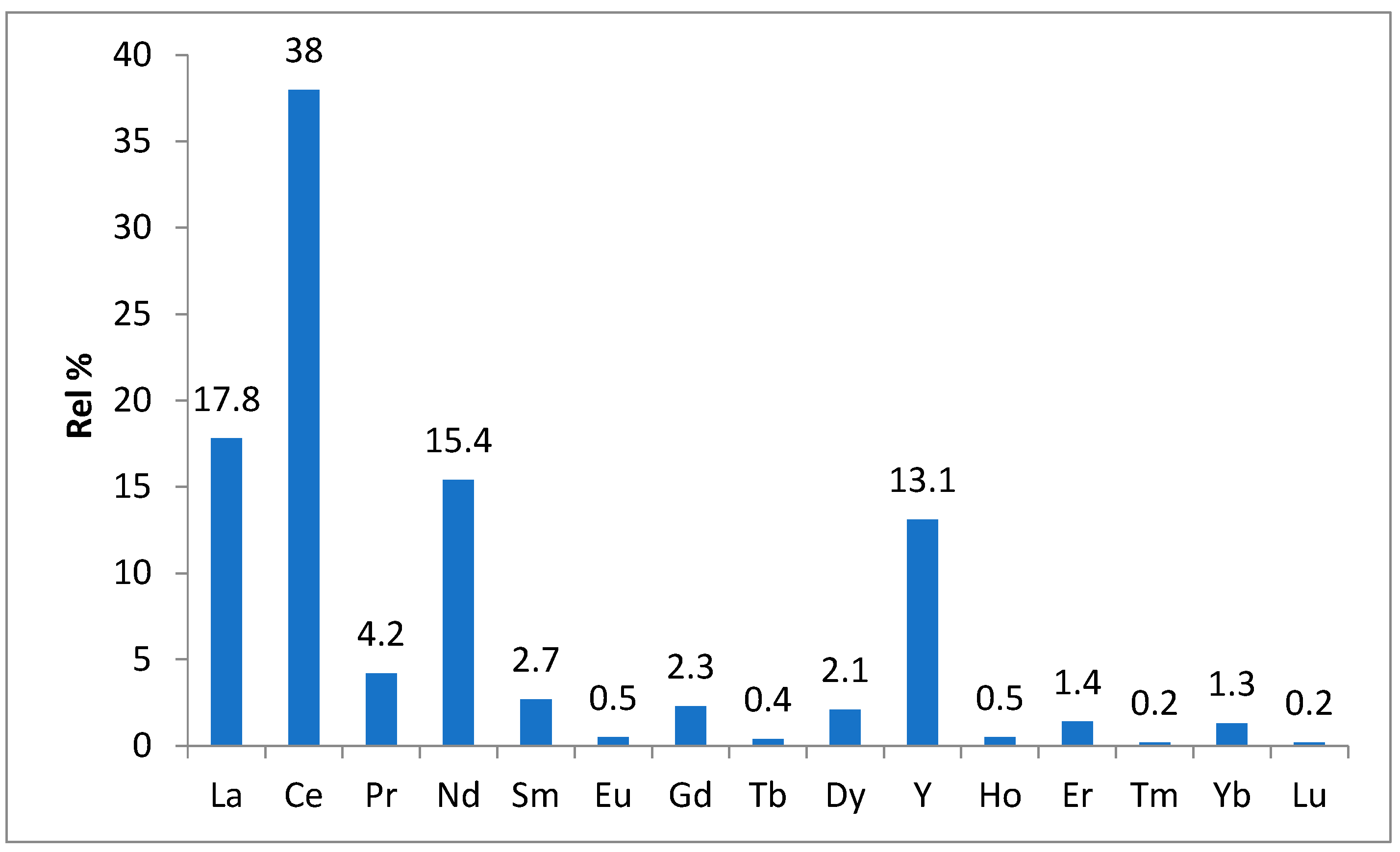

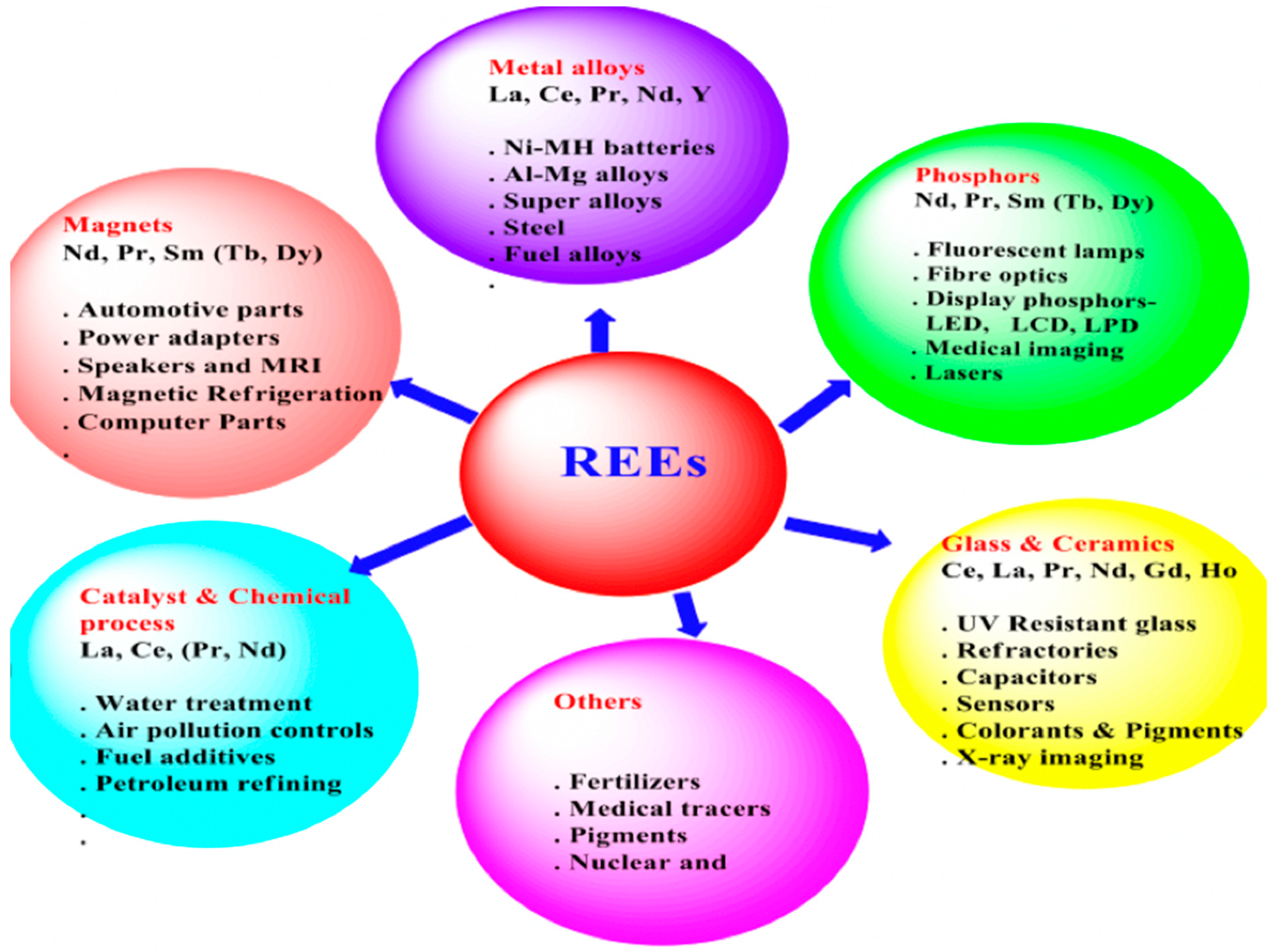

The three classes of rare earth elements (REEs) are light (LREE-La, Ce, Pr, Nd, and Sm), medium (MREE-Eu, Gd, Tb, Dy, and Y), and heavy (HREE-Ho, Er, Tm, Yb, and Lu) based on their geochemical characteristics. The REEs fall into three categories: critical (Nd, Eu, Tb, Dy, Y, and Er), uncritical (La, Pr, Sm, and Gd), and excessive (Ce, Ho, Tm, Yb, and Lu). Geochemical color and industrial shading are related, as

Figure 1 shows [

3,

4].

Rare earth elements (REEs) have distinct chemical and physical characteristics that make them useful in a range of applications, despite having similar electrical configurations. REEs offer their final products a special magnetic, brilliant, and strong quality. Because of this, REEs are utilized in a variety of modern technologies, including alloys, laptop screens, lasers, and glasses [

5]. Despite having less than 40% of the world’s known reserves, China produces about 90% of the rare earths. In addition to mining the rare earth oxides from the ores, China offers downstream facilities such as separation into individual elements, processing into rare earth metals, and manufacturing of rare earth permanent magnets and lamp phosphors. [

6]

REEs have been utilized in many high-end technologies over the past thirty years, such as computers, networks, communications, healthcare, smart electronic goods, efficient lighting, displays, and clean energy technologies (such as solar, wind, electric vehicles, and tidal power generation). Because rare earth elements are deeply ingrained in contemporary technology, their significance in society and the economy is growing [

7].

Plugs, power cords, batteries, and other parts that are attached to electronic devices are also included in the category of “e-waste,” in addition to electronic materials. Additionally, electronic and electrical equipment that is partially or entirely abandoned by producers or end users is referred to as “e-waste.” Reused, reprocessed, retrieved, or disposed of discarded EEE can also be considered E-waste.

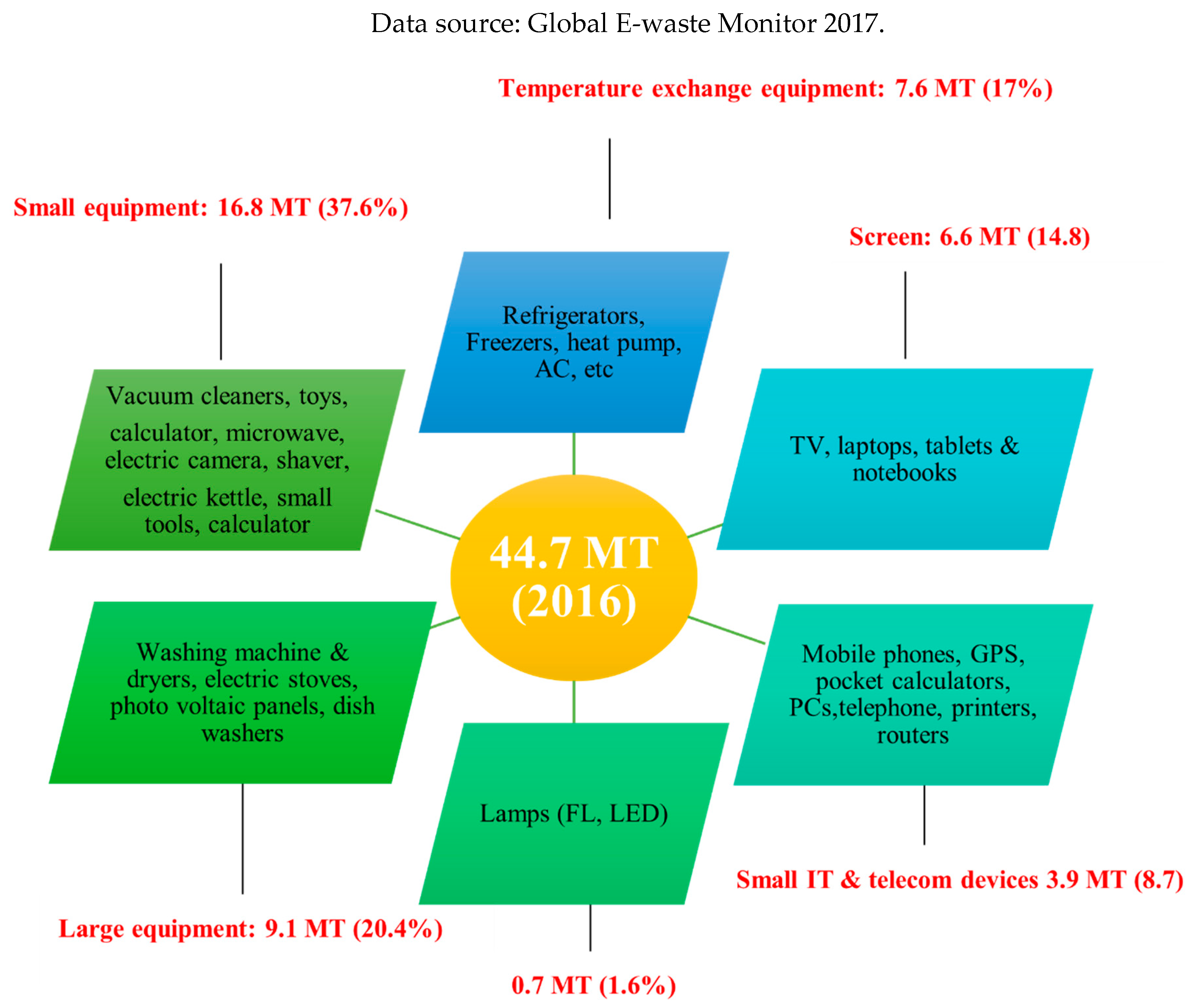

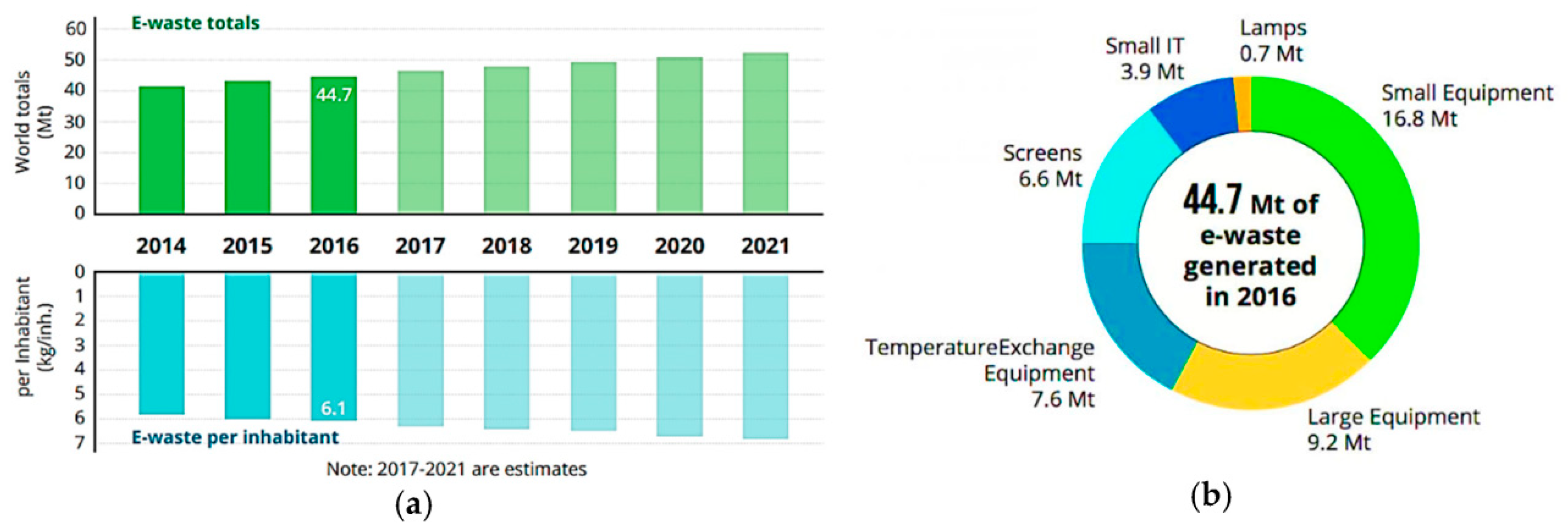

Products for homes, businesses, and consumer electronics are all included in the category of e-waste. Large equipment, small home equipment, small IIT and telecom devices, screens, lighting, and temperature exchange equipment are the six basic categories into which equipment can be broadly classified. E-waste includes various components such as batteries, lead capacitors, circuit boards, plastic casings, activated glass, and cathode-ray tubes. Even with major home appliances and HVAC systems, personal electronics like laptops, computers, monitors, cellphones, and televisions account for almost half of all e-waste. The distribution of different types of equipment and devices that were produced globally for e-waste in 2016 is shown in

Figure 2.

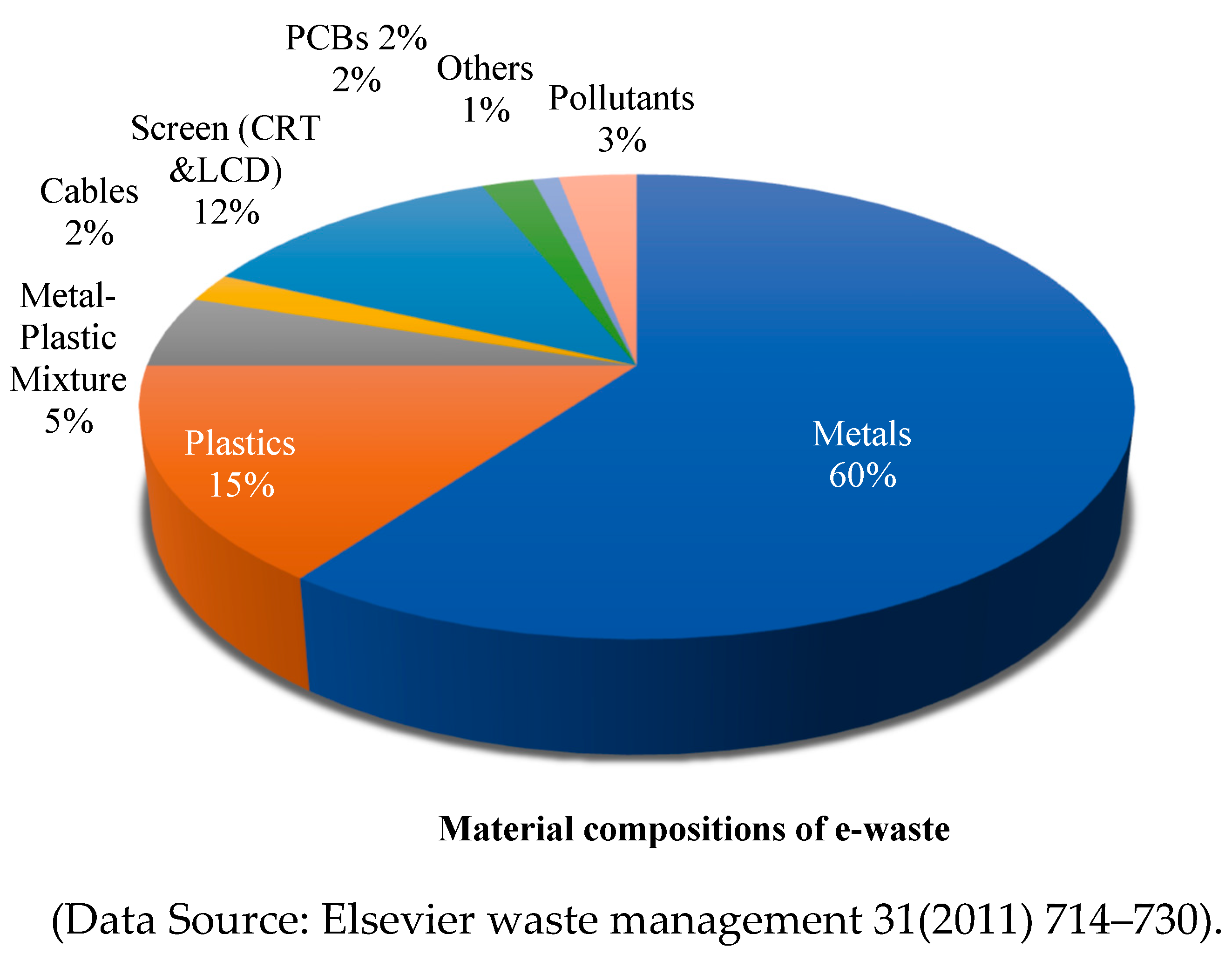

E-waste is a highly diverse and complicated waste stream that is greatly influenced by several variables, including the kind of electronic equipment, the manufacturer, the model, the year of creation, and its age. Generally speaking, e-waste consists of glass, wood, plastic, ceramic, concrete, rubber, and metals (ferrous and non-ferrous). Copper, aluminium, rare earth elements, and precious metals (such as gold, platinum, silver, etc.) are examples of non-ferrous metals. Base metals contain significant amounts of iron and aluminium. In a similar vein, rare earth elements (REEs) and valuable metals are also found in modest quantities. Toxic substances, including Pb, Hg, Cd, Se, Cr, and brominated biphenyls (a type of flame retardant), are among the metals. The typical material composition of e-waste is shown in

Figure 3.

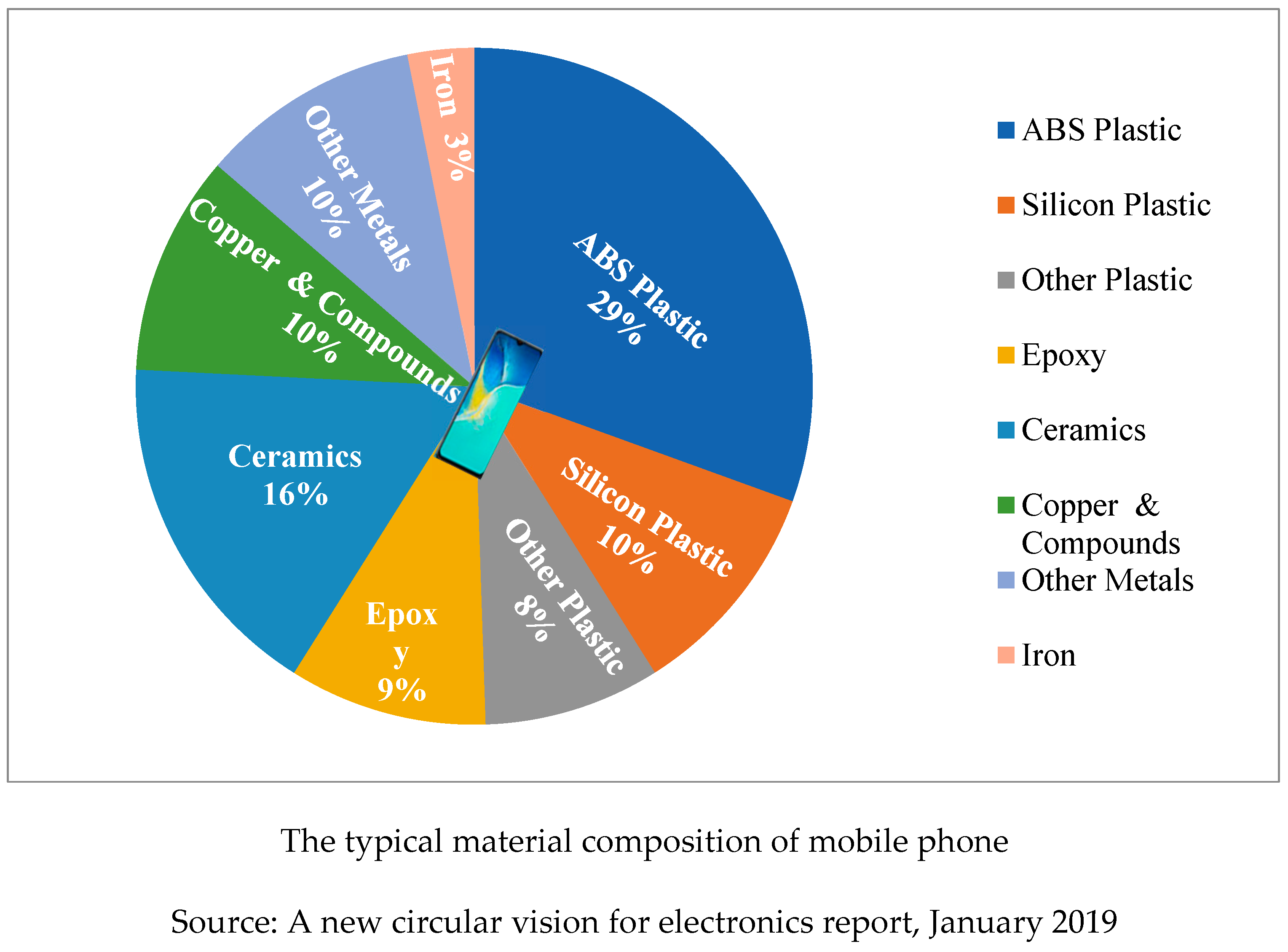

Without cell phones, modern digital technologies would not be possible. There are more than 5 billion mobile phones in use worldwide, belonging to about two-thirds of all people. Almost two-thirds of people on the planet use one of the more than 5 billion mobile phones that are in use today. One billion people use mobile phones in India. Users’ mobile phones are changing at a quick pace due to the development of new technology, producing a large amount of e-waste that contains valuable materials. The common make-up of mobile phones is depicted in

Figure 4 of the pie chart [

8].

Due to the short lifespan of electronic products like computers and mobile phones and their growing use, the amount of electronic garbage, or “e-waste,” has surged globally. The amount of electronic trash is growing and includes a variety of devices, from personal computers to large home equipment (air conditioners, freezers, refrigerators, mobile phones, and sound systems). In Asian nations experiencing rapid economic development, the 3R principle of reduce, reuse, recycle is essential for managing the transboundary movement of secondary resources. Effective management of resources, including raw materials used in industry, is necessary to reduce environmental pollution. Global plastic production in 2014 was estimated to be 0.27 billion tons, of which 0.05 billion tons were from the European Union (EU) (Plastic Europe 2017). There were 0.0028 billion tons of plastic used in the electric and electronic equipment (EEE). The EU countries use 17.4 Kg EEE per individual in 2013 [

9].

There are several definitions for e-waste. The term “e-waste” in this context refers to a particular type of waste that includes outdated, discarded, and/or end-of-life electronics that need power to function. Electronics (LCDs, PCs, smartphones, screens), big appliances (fridges, washers), and numerous other consumables are examples of e-waste. These consumable goods either had manufacturing defects or were thrown away by their original owners. The projected amount of e-waste in 2016 was 44.7 million tonnes, or 6.1 kg/person, and it is projected to increase to 52.2 million tonnes in 2021 (

Figure 5) [

10].

With an estimated 45 million tons generated globally in 2014 and a growth rate of 3-5%, e-waste is one of the waste streams with the quickest rate of increase in the world. To account for this change in the EEE industry, the European Union (EU) has changed CE performance standards and the waste electrical and electronic equipment (WEEE) regulation. Finland is one of the EU members that actively promotes e-waste, and since 2010, the country’s e-waste recycling rate has risen from 28.7% to 49.2%. E-waste is classified as a secondary resource due to its higher concentration of precious metals, such as REEs, compared to primary ores [

11].

According to estimates, computers produce 70% of India’s e-waste, followed by telecoms at 13%, electrical at 8%, medical at 7%, and domestic products, including e-scrap, at 3%. The growing generation of IT trash makes it challenging for developing nations like China, India, Nigeria, and others to recycle and manage e-waste. As per a study released by the Lok Sabha on September 23, 2020, the generation of e-waste in India has surged by 43% during the last three years [

12]

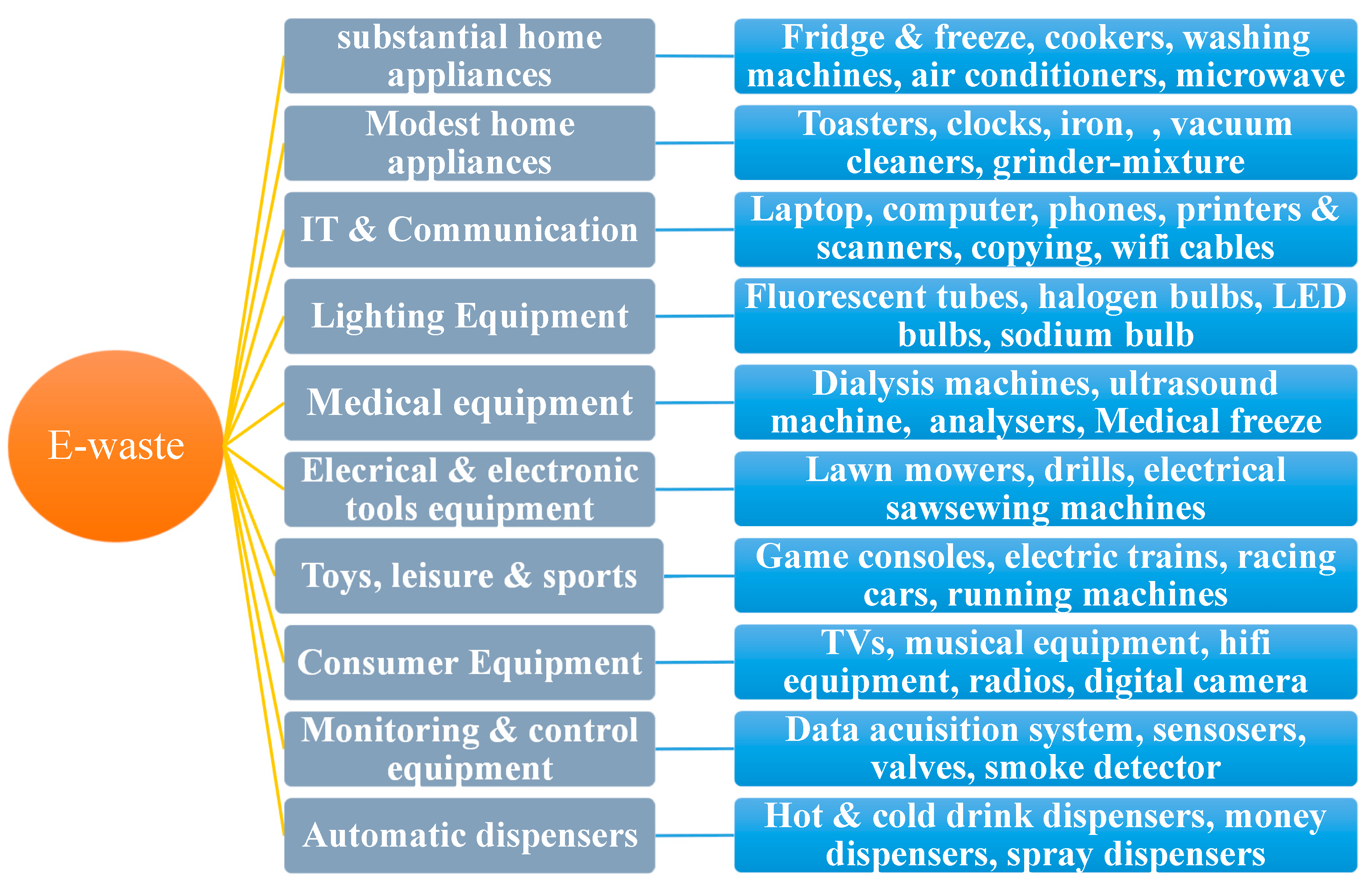

Based on its function and place of origin, electronic waste can be categorized. Ten categories of e-waste exist globally (

Figure 6). Numerous businesses and homes utilize electronic and electrical equipment (EEE), and the proportion of each category varies based on population, consumer behavior, and socioeconomic situations. However, the largest percentage of e-waste comes from household a product (42.1%), which is followed by small domestic equipment (4.7%), consumer devices (13.7%), IT and telecommunications (33.9%), and household items. Other categories—medical, electrical, lighting, and electronic tools—have smaller contributions as a result (2% against 1% for automatic dispensers, toys, control devices, and sports). In poorer nations, televisions, laptops, and mobile phones account for the majority of e-waste [

13].

1.1. E-Waste Derived Rare Earth Elements (REEs): characteristics, Sources, and Uses

e-waste, particularly from laptops, computers, electric cars, solar cells, and cell phones, which is fueling the IIT sector’s rapid expansion in electronics and improving economic rates. There is a surge in e-waste as a result of the public and private sectors replacing outdated electronic gadgets with new ones in order to introduce new technologies. Domestic e-waste is produced by institutions, PC manufacturers, small and large businesses, and other industries in addition to household gadgets. The generation that contributes most is represented by computers and mobile phones, whereas households make up the least amount. The issues with e-waste disposal are brought on by the prohibitions on disposing of these products in several nations. The key factors contributing to the rise in illegal e-waste imports include low labor costs, lower processing costs, and lax enforcement of environmental regulations. The amount of e-waste created cannot be accurately estimated, even if no one knows how much is produced, imported, or exported to other nations. It is difficult to get precise information on the amount of e-waste that is recycled by various industries in another method [

14].

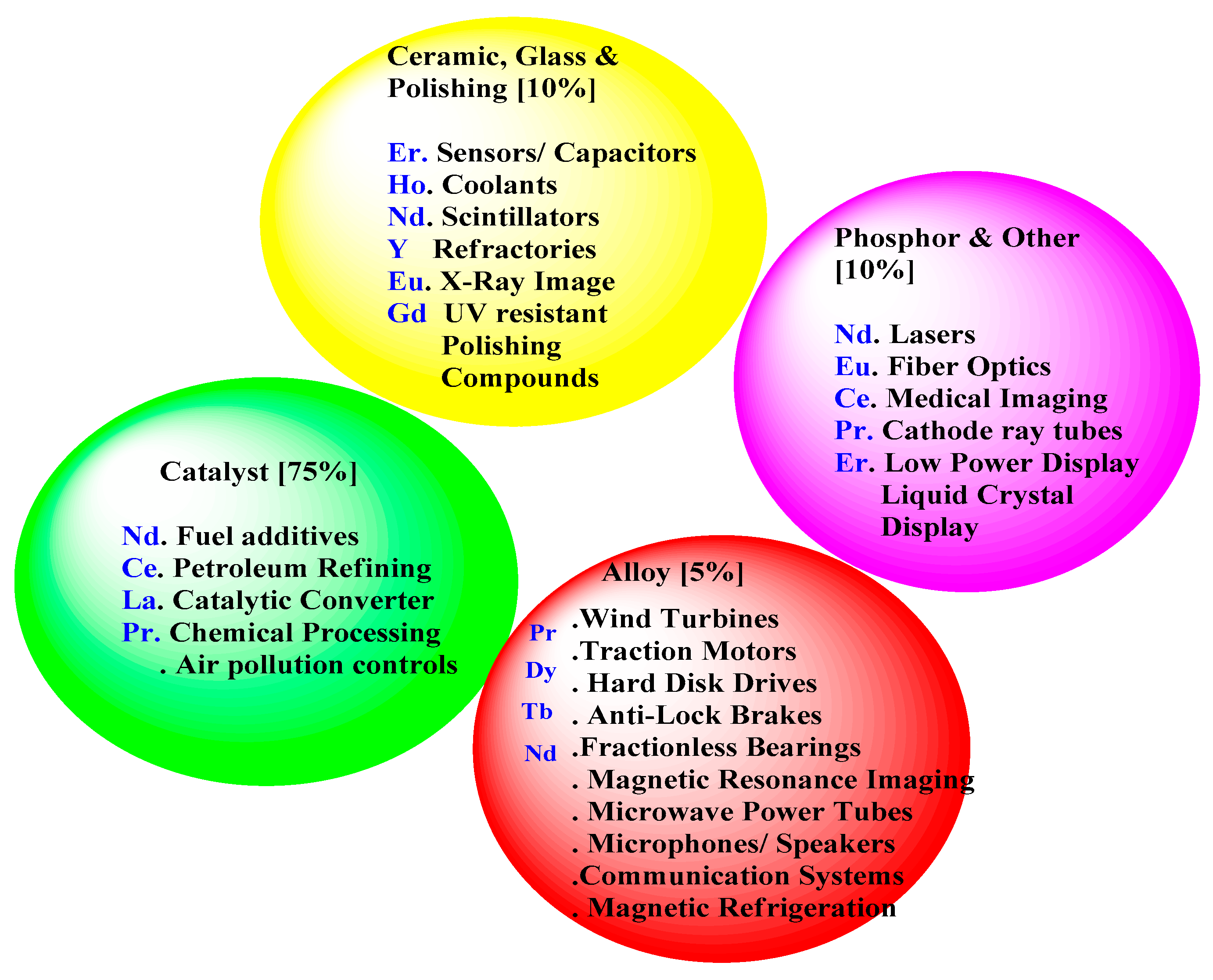

REEs are a crucial part of renewable energy technologies, such as electric cars, hydrogen storage, high-efficiency lighting, and wind turbines, because of their special chemical and physical characteristics. As a result, lasers, high-intensity magnets, and colored phosphors are the main applications for rare earth magnets. Because of their remarkable properties, which include great thermal stability, good luminous intensity, capacity to determine color when emitted, longevity, and low energy consumption, phosphors are employed in lighting applications. The current studies (such as the US Geological Survey’s Mineral Commodity Summaries 2020 report) approximate the distribution of REEs by end-use, with the following categories represented in the literature [18]: catalyst (~75%), glass, polishing, and ceramics (~10%), alloy and metallurgical application (~5%), and others (~10%) which are represented in

Figure 7 [

15].

Wastes of an industrial, electrical, or mining nature can be divided into three major groups that are useful for identifying potential sources of rare earth elements. Fly ash from the coal processing industry and trash from the mineral processing industry, such as phosphogypsum and red mud, are frequently used industrial wastes in the extraction of rare earth elements. Mine tailings and acid mine drainage are the main suppliers of mining waste for rare earth elements. For magnetic and electronic wastes, which are an important part of speakers, hard drives, phosphors, and spectrometers, NiMH batteries are a major source of rare earth elements (REEs) [

16].

In the last three decades, REE and its alloys have found extensive application in a wide range of technological devices, including but not limited to solar panels, computer memory, rechargeable batteries, LED lighting, DVDs, autocatalytic converters, super magnets, glass additives, mobile phones, superconductors, fluorescent materials, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Known as “The Vitamins of Modern Industry,” these parts are essential to all electronic equipment [

17].

There are now more reasons in favor of discovering workable methods for the recycling of rare earth elements due to the ongoing increase in demand across numerous industries. By taking this method to recycling REEs, we can help recover important metals, reduce environmental pollution from harmful compounds, and free up a lot of landfill space and heavy metals that have leached into the soil. In terms of REE at their specific concentration, electronic devices are considered secondary sources. REE have a significant and vital role in how well electronic gadgets operate (

Figure 8). Because of their luminous qualities, REEs are utilized in fluorescent and LED lighting, for instance. Likewise, REEs are employed by digital displays to modify both color and light. Reinforcement of permanent magnets with an increased resistance to demagnetization is another significant application of these materials. In the automobile industry, REEs support the alloy of NiMH batteries used in catalytic converters, hydrogen gas storage, and gas desorption and reabsorption. Ni-MH batteries, fluorescent lights, and permanent magnets all have the ability to contain this kind of waste as secondary REEs resources [

18].

The extensive usage of rare earth elements (REEs) in high-tech applications like catalysis, sophisticated alloys, and permanent magnets makes them significant players in contemporary global economy. These metals have been used in fields other than agriculture, such as medical contrast, fluorescent materials, and fertilizers. While most REEs are extracted in China, they are increasingly being extracted globally. REEs are hazardous to humans, animals, and plants in high quantities due to waste processing, mining, and industrial use. It has been demonstrated that REEs in industrial settings can lead to toxicities of the liver, heart, brain, and lungs. An growth in the exploitation of rare earth elements (REEs) coupled with the production of REE trash presents a significant environmental risk and may result in detrimental effects on human health and the environment [

19].

1.2. REEs Derived from City Waste

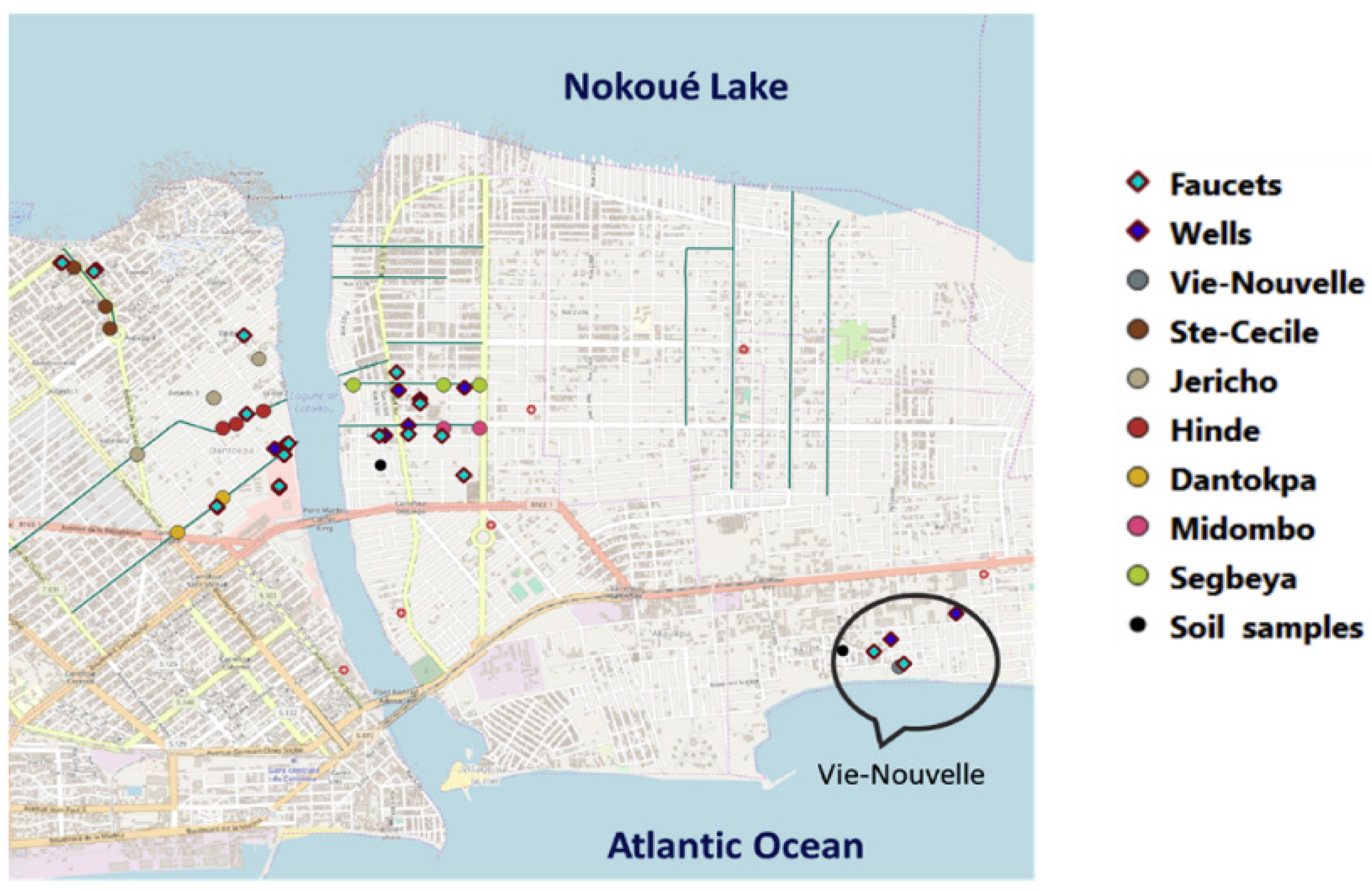

Since China has supplied more than 90% of the world’s supply of REEs up to this point, it is the leader in this regard. In 2021, just 60% of the world’s supply will be generated due to China’s recent slowdown in REE production. The glass sector is the largest user of REE raw materials, and REEs are used in numerous technical applications because many products are manufactured with them in mind [

20]. The percentages of Benin’s rural and urban populations who have access to sanitation are 17% and 61%, respectively. Household wastewater is dumped in the courtyard by 20.1% of households, and into the natural environment by 70% of households. 57% of houses in Cotonou (

Figure 9), the capital and largest city of Benin, dispose of their wastewater outdoors, whereas 9.6% dispose of it in containers. According to INSAE data from 2016, 3.5% and 7.2% of wastewater, respectively, was disposed of in open and close sewers. Nevertheless, untreated garbage from these sewers is released into the shallow or Cotonou Channel. While 21% of the population collects septic water in tanks or latrines, graywater is collected in sump pumps for those with access to individual sanitation systems. This state only partially achieves its goal of maintaining and protecting human health because Cotonou’s water table is close to the surface and easily affected by infiltration. The efficiency of the Vie Nouvelle wastewater treatment facility is not at its maximum [

21].

There are more than 30 million people living in Beijing and Tiajin, two well-known cities in North China. By 2020, 18.33 million people were living there, of which 14.81 million (80.80%) lived in cities and 3.65 million (19.91%) in rural areas. The study region is a typical urban river with low flow and little capability for self-purification. The river ecosystem has been restored by the Chinese government in recent times, but despite this, the water quality is still not good due to a lack of proper study on urban water pollution and the existence of many point and non-point pollution sources. The water quality of urban rivers and the combined toxicity of several rare earth elements (REEs) are still unknown and need more research. These investigations examined the geochemical properties of dissolved rare earth elements (REEs) in 17 samples taken from the Yongding River. There are three primary goals for the study: 1) to ascertain the variance in the Yongding River’s REEs content and its spatial distribution; 2) to pinpoint the variables such as population, hospital, land use, and others that affect the aberrant concentration of REEs. 3) The purpose of using REEs and hydro-chemical indicators is to monitor the causes of pollution in this typical urban river [

22].

REEs are now known to be possible micropollutants due to an increase in their concentration in the hydrosphere and tap water. The most well-known REE is gd, which is present in large concentrations in Europe, Australia, Asia, and North America. Over time, the amount of gadolinium found in tap water in the Garonne Estuary, Berlin, Germany, and San Francisco Bay, California, has increased. Two tributaries of the Herault River in France and certain wells that supply drinkable water have been found to contain high quantities of lead (Pb) up to 15.4 Pm (i.e., 2.4 ng/L). Anomalous results have been found for La, Sm, and Ce. Based on information gathered from Africa, it’s possible that some of the rare earth elements (REEs) found in Lagos State, Nigeria, leached from electronic waste disposal sites. Similar to other metals, rare earth elements (REEs) can build up in aquatic plants and fish, impeding fish embryo and larvagenesis. Gold leakage from chelates used in medicine is an increasing concern regarding the safety of gold in humans, especially in light of treatment facilities’ increased handling of organic micropollutants. Epidemiological surveys have been driven by recent concerns regarding the consequences of rare earth element (REE) mining on human health and agricultural output [

23].

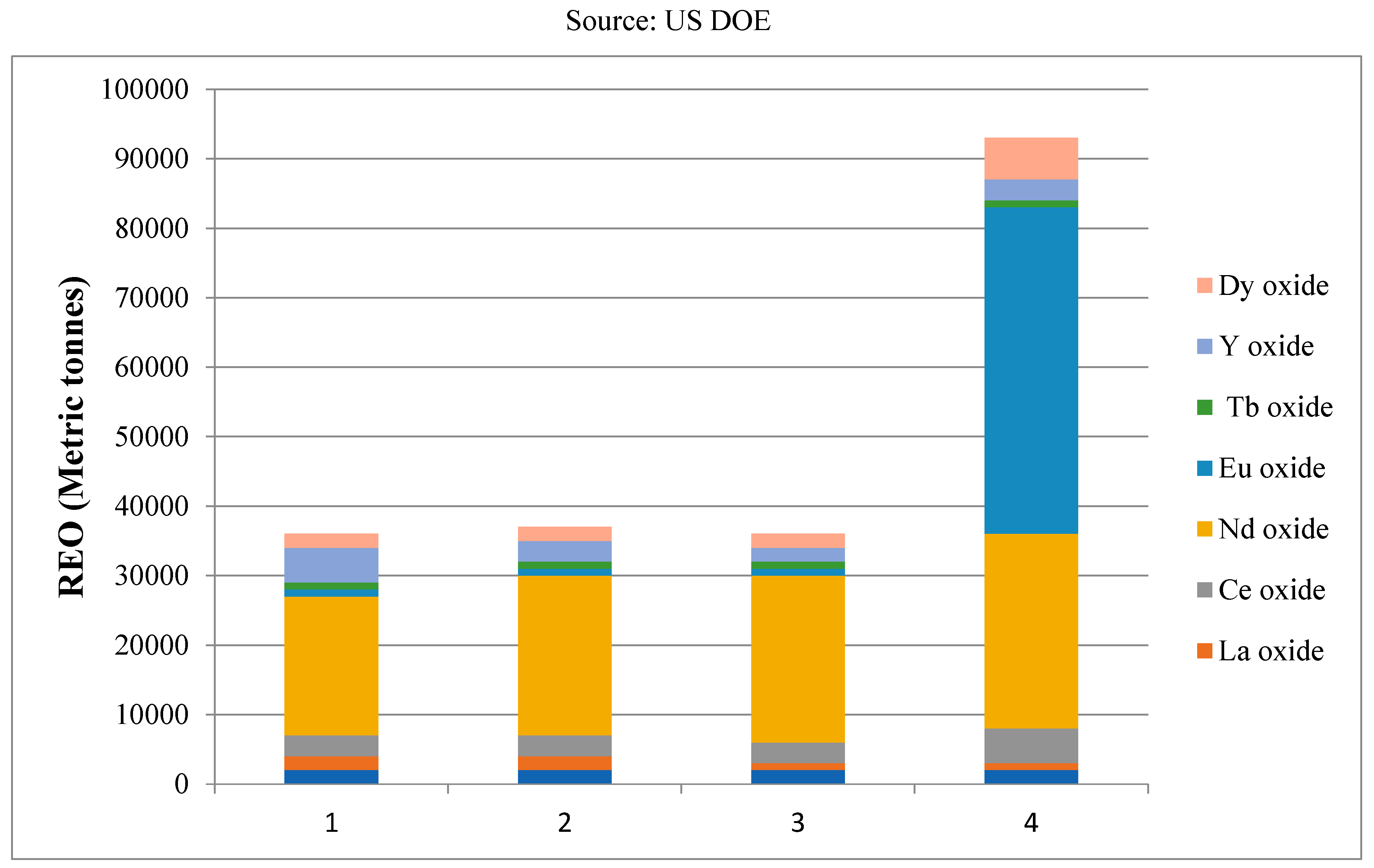

1.3. Rare Earth Elements (REEs) and Their Function in Clean and Green Energy Technologies

For green energy technologies, Tb, Dy, Nd, and Yt are the most important rare earth elements. U.S. Department of Energy (2010) claims that these elements are essential to the energy supply because of their supply and demand. In order to meet human requirements on the world today, clean and green energy is required. Future predictions indicate a steady rise in the use of renewable energy technologies (CETs), including electric cars, solar cells, wind turbines, and fluorescent lighting. Key components used in the production of these technologies include REEs (Dy, Nd, Tb, Eu, and Yt). The US Department of Energy (DOE) states that Yt, Dy, Nd, Tb, Eu, and Ce are critical, and La and Ce are almost critical. REEs are important for low-carbon technologies. According to the US Department of Energy (2010), there are a number of reasons why certain REEs are essential for supply. China is the country with the greatest reserves of rare earth elements (REEs) in the world, followed by Greenland, Australia, Canada, the USA, South Africa, Tanzania, Brazil, Vietnam, and Russia. The volume, quality, and cost of refining determine their processing, economics, and feasibility (US Department of Energy, 2010) [

24].

For the past few decades, non-renewable resources like coal, natural gas, and oil have provided the majority of the world’s energy demands. In the contemporary world, consequences like air pollution, climate change, and global warming have gained immense importance. Furthermore, the necessity to diversify the energy portfolio in the direction of a global green energy system has already arisen due to the volatility of oil prices, economic risks, geopolitical concerns, and upcoming difficulties like peak oil. In order to meet the demands of future energy, renewable energy sources including wind, solar, and tidal energy have drawn attention from all around the world. Within this framework, advanced and eco-friendly energy collecting technologies like solar panels and wind turbines are the best features of REEs, particularly HREEs [

25].

The principal energy source for the world will rise at an average annual rate of 1.3% by 2035. More than 75% of the world’s energy supply will come from fossil fuels by 2035, making them the main energy source. The fastest-growing energy source is renewable energy, which is expected to expand by more than 10% by 2035. Due to the rising demand for energy-saving and green power generation, applications of rare earth elements (REEs) in permanent magnets with wind turbines and other energy-efficient technologies will become increasingly important in the future years. Electric vehicles, catalytic converters, and NiMH batteries will all help to lower greenhouse gas emissions and slow down global warming. The demand for REEs will increase in tandem with the growth of the renewable energy sector. As a result, the demand for each unique REE will increase differently.

Table 1 displays the average amount of each particular REE used in each application, while

Figure 10 shows the global demand for clean technology-derived REE.

It is estimated that by 2016, 2020, 2025, and 2030, the demand for clean technologies will be 33.9, 33.3, 33.6, and 51.9 kt REO. LFL and CFL lighting’s market share will decrease over the next few years as LED lighting becomes more and more popular and REE demand for CFL and LFL lighting declines. In the clean market, the percentage demand share of REO (rare earth oxides) from lighting will decrease to 3.2% in 2030 from 29.2% in 2016. On the other hand, it is anticipated that the oxide demand for Tb, Yt, and Eu for lighting purposes will drop to 16.6%, 16.4%, and 17.2% of the level of 2016.

On the other hand, different levels of growth will be seen in the electric car, NIMH batteries, wind energy, and catalytic converter markets. This suggests that Nd and Dy oxides will be more important in the future development of renewable energy, while Eu and Tb will be less so. In order to predict future trends in REE production and consumption, we looked at two fundamental possibilities in our analysis. (1)A conservative growth rate of 3% per year for REE output, and (2)An enthusiastic growth rate of 5% per year for REE production. A growth scenario for the production of REEs at 3% and 5% is shown in

Table 2. The essential raw material for permanent magnets, Nd, does not fulfill the increasing demand through conservative scenarios but rather through optimistic ones. Under the conservative scenario, Tb, Y, and Eu elements will be significantly higher over the coming years. Furthermore, Dy will lose out in both situations because by 2030, production of this element can fulfil 50% to 70% of the demand from clean technologies in the two different scenarios. In the next years, Nd and Dy will be essential elements of clean technologies, and the result of any new REE project will largely depend on their performance. Additionally, there will be an imbalance in the market between the supply and demand for each unique REE [

26].

2. REE Extraction and Recovery from E-Waste

The primary driving force behind recycling electronic waste is the recovery of rare earth elements (REEs). Siderophores, bioleaching, and biosorption are the techniques used for the recovery and separation of REEs. E-waste recycling is a serious issue. REE recovery. Hydrometallurgy, pyrometallurgy, and materials derived from carbon. Every technique or treatment has benefits and drawbacks. This section discusses the many methods and procedures used to recover rare earth elements (REEs) from electrical waste.

Mesophiles, moderately thermophilic bacteria, and extremophiles are examples of microorganisms that can be used in bioleaching, an efficient method of recovering metal from primary and secondary sources. It is particularly useful in the commercial recovery of certain metals from their ores, including molybdenum (Mo), copper (Cu), zinc (Zn), nickel (Ni), arsenic (As), cobalt (Co), antimony (Sb), gallium (Ga), palladium (Pd), platinum (Pt), and osmium (Os).

Research has looked into the extraction of rare earth elements (REEs) from electronic waste using bio-recovery, which includes bio-reduction, acidolysis, biomineralization, and cyanogenic bioleaching. Bioleaching can also be applied for the extraction of metals from mines, flay ashes, contaminated soils, sludge, and spent catalysts. The results demonstrated that bio-recovery is a more economical and environmentally benign method of recovering valuable metals from waste electrical and electronic equipment (WEEE) than other techniques like hydrometallurgy and pyrometallurgy. These methods have allowed for a greater understanding of metal mobilization, toxicity processes, and biotechnological process optimization in order to recover rare earth elements (REEs) from electronic waste. Ilyas and Lee (2014) have recovered 99% of the copper metal from biomass waste by the use of bioleaching. They found that recovering copper metal from biomass results in less pollution than conventional metal processing. They further claimed that this method might be used to recover metals from their ores and other secondary sources, like electronic waste. A summary of some studies on the bioleaching technique for removing REEs from WEEE is provided in

Table 2.

Biosorption is currently one of the biological techniques that receives the most attention in the field of recovering metals from electronic waste due to its unique qualities, which include high regeneration, fast kinetics, high recovery efficiency for metals in low concentrations, and the absence of secondary residues. It is inexpensive, operates and uses in situ with great efficiency, removes impurities from aqueous solutions with high efficiency, and doesn’t create any chemical sludge. Furthermore, in contrast to traditional methods, it is simple to integrate with any system. Numerous experiments have been conducted in recent decades to recover rare earth metals from electronic trash by employing algae, fungi, and bacteria as biosorption materials. In addition, the biosorption of metals is influenced by temperature, pH, agitation rate, contact time, and beginning metal concentration, as shown in

Figure 3. The effectiveness of recovering metals from electronic trash is also influenced by the optimum process settings and the adsorbent’s technology compatibility.

Biosorption technology has made it possible and reasonably priced to extract rare earth elements (REEs) from electronic waste. To determine the precise compatibility of different biosorbents for the recovery of metals, more research must be done.

Siderophores are small, highly-affinity molecules that chelate iron and are secreted by microorganisms such as bacteria, fungi, and grasses. The chelator molecules are produced to seek for Fe+3 in the environment in order to satisfy the microbe’s metabolic needs. They are considered to be the best ligands for ferric ions. In addition, siderophores may also be particularly attractive to other metals, which may uncover fresh information on an interesting method for recovering rare earth elements that is safe for the environment and biological systems. Studies have evaluated the effectiveness of rare earth element (REE) recovery with siderophore chemical leaching. Research has shown that siderophores have a significant preference for the naturally occurring substance desferrioxamine. Siderophores are a more cost-effective, rapid, reversible, and ecologically benign method of recovering rare earth elements (REEs) than existing techniques. Tiny amounts of REEs are recovered from a variety of electronic wastes that have reached the end of their useful lives. Siderophores have a high degree of stability, similar to other end-of-life electronic wastes, which can enhance the recovery of rare earth elements (REE) from secondary sources. It has a specific application for the recovery of rare earth elements in the future and can be applied to many different environmental domains.

Pyrometallurgy is a popular thermal method that can be used to recover metals from electronic waste. In addition to smelting in a copper smelter, blast furnace, or plasma arc furnace, this procedure also entails high heat roasting in the presence of certain gases and cremation in order to recover predominantly non-ferrous metals.This technique is also notable for using a lot of energy. On the other hand, it is particularly effective at recovering specific rare earth elements from electronic waste. One relates to the environmental issue caused by dioxin production, high-tech smelting that can result in the production of slags and the development of another industrial system, and the discharge of hazardous compounds. An additional problem is the requirement for a more sophisticated, and therefore more expensive, control emission system.

Furthermore, prolonged periods are needed for the recovery and separation of valuable metals. Consequently, integration of pyrometallurgy and electrorefining is necessary for the complete extraction of metals from electronic waste.

Figure 4 depicts all product streams and the ensuing waste stream treatments, as well as the intricate processing phases based on industrial designs. Another technique is vacuum pyrometallurgy, which uses sublimation or distillation to extract rare earth elements (REEs) from electronic wastes by creating a pressure differential. However, additional study is needed to improve process performance in the future by taking into account cheaper feedstock, process intensification, and various process configurations.

One chemical technique that can be used to remove metals from electronic trash is hydrometallurgy. The technique of extracting rare earth elements (REEs) from electronic trash involves the use of a chloride solution to extract elements including gadolinium, yttrium, and lanthanum. However, there are certain disadvantages to this method, including the production of sludge, heavy metal contamination, and toxicity. There are two phases involved in the hydrometallurgy method of recovering and extracting REE elements from electronic trash. Leaching metals from electronic trash with mineral acids is the first stage. Metal leaching from electronic waste can be influenced by a wide range of variables, such as redox potential, leaching kinetics, lixiviant type, particle size, pH, temperature, and agitation. The second phase of the procedure involves employing adsorption, liquid-liquid extraction, cementation precipitation, and electro-winning to recover the dissolved metals from the leachate. This technique, which uses an ionic liquid and precipitation to recover the metals, has been proven to be quite effective. Nevertheless, secondary sludge is produced when metals are recovered by precipitation. Furthermore, numerous studies have demonstrated that the problem of sludge generation might be resolved by recovering metals through adsorption and electro-winning. In general, there are several hydrometallurgical methods for separating REEs from WEEE [

27].

3. Ionic Liquids and Their Uses in the Processing of E-Waste

Ionic liquids (ILs) are substances with a melting point below 100 °C and are composed entirely of ions. Over the past 20 years, a lot of attention has been paid to inorganic semiconductors (ILs) because of their unique combination of physicochemical properties, including low volatility, high thermal stability, strong dissolving powers, low flash points, high chemical stabilities, catalytic activities, a tunable range of polarities, and relatively high electro conductivities. A variety of anions can be added to cations to change their architectures and hence adapt the necessary physicochemical properties for a given application [

28]. ILs provides some unique features while producing inorganic compounds. ILs can aid in the dissolution of a range of precursors, including both organic and inorganic compounds, which is necessary for the synthesis of most materials. Imidazolium ions (ILs) are frequently employed to offer a distinct microphasic separation of the hydrophilic and hydrophobic fragments due to their extended alkyl chain. The diversity of ILs enables the control of nucleation and growth rates, particle sizes, and morphologies during the synthesis of compounds. In addition, ILs have several other desirable characteristics that make them an attractive alternative to conventional organic solvents in the production of inorganic substances and high-temperature reactions in melts or the solid state. These properties include high polarizability for microwave synthesis, wide electrochemical windows, high conductivity for electro deposition, and good thermal stability in ionothermal synthesis [

29].

Ionic liquids (ILs) are a class of solvent that have been proposed as volatile organic compound alternatives for various applications due to their unique properties in recent times. Chiral ionic liquids, or CILs for short, are a subclass of ionic liquids in which the cation, anion, or both have a chiral moiety. Subsequently, a great deal of information about CILs has been gathered and studied for a variety of uses, such as chiral selections, backgrounds for electrolytic ingredients, chromatographic and electrophoretic techniques, and separation processes where CILs have been used as chiral ligands. Various CILs possessing chiral recognition properties have been utilized as NMR chiral shift reagents for racial discrimination. Aqueous biphasic systems based on CILs and salts were proposed in 2015 for the enantiomeric separation of amino acids [

30].

In 1998, the use of ionic liquids for metal ion extraction was first documented. Because of their benefits over conventional organic solvents, ionic liquids are an intriguing option for extraction research. They are non-volatile because at ambient temperature they have a very little vapor pressure. In comparison to traditional organic solvents, they are also less flammable, have a wider liquidus range, and have better thermal stability. Less harmful substitutes for volatile organic solvents are being sought after, as worries about the safety and environmental effects of these solvents become more pressing. Owing to their wide range of cations and anions, which can be chosen to produce ionic liquids with the right qualities for a particular application, ionic liquids are frequently referred to as designer solvents. Ten Ionic liquids for solvent extraction can be made to dissolve the extracted metal complexes while also being immiscible with water (hydrophobic ionic liquids) [

31].

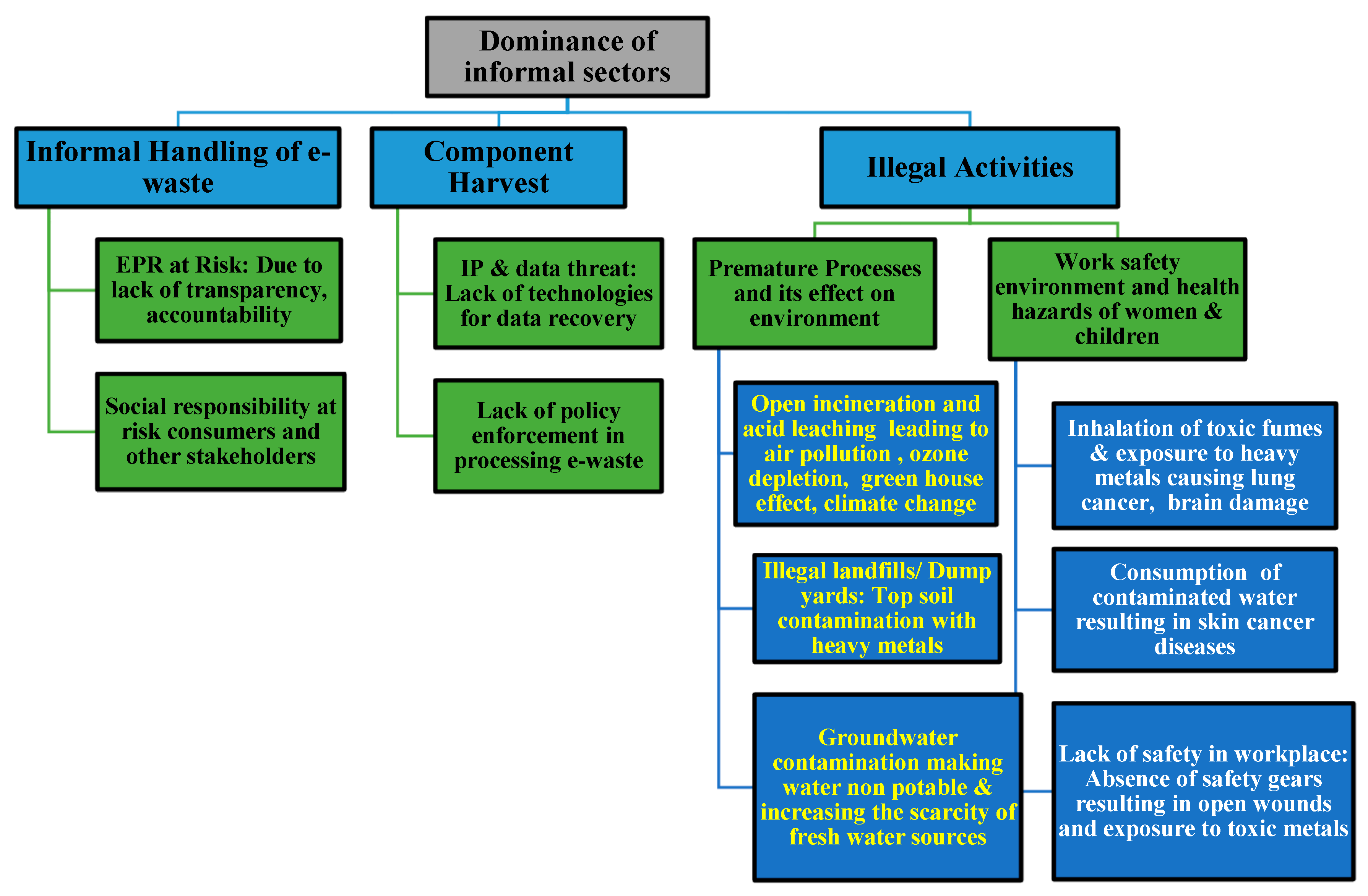

4. Health and Environmental Issues with longer-Lasting, Cleaner Solutions

The handling of e-waste in the formal sector has an irreversible impact on human health and the environment. Most EEE components include dangerous compounds that, if not handled with extreme caution, could endanger both human health and the environment. Living close to businesses that recycle and burn waste might cause major health issues for nearby residents (

Table 3). Not only does inadequate handling of e-waste have an immediate impact on human health, but it also has far-reaching effects. Additionally, there are unintended health effects from eating crops cultivated in e-waste-contaminated soil. The groundwater is contaminated by the unlawful dumps, which has an impact on the food chain and causes a number of ailments. Certain metals that end up in rivers degrade the water’s suitability for drinking. Toxic vapors can be emitted into the air as a result of the open burning and acid leaching of e-waste, which can result in death or irreversible harm to the respiratory system. The globe may experience issues like global warming and ozone layer depletion as a result of atmospheric pollution. Pollution from heavy metals will eventually make its way into the food chain and diminish soil productivity. Metal contamination causes genotoxicity, which damages genes and leads to the condition known as cancer. Children, workers at processing plants, and pregnant women are the most vulnerable groups impacted by illicit behaviors (

Figure 11) [

32].

There are numerous negative repercussions on both individuals and the environment as a result of electronic trash. The mishandling and advancement of technology has made this predicament extremely dangerous for human existence. The two primary requirements that electronic waste negatively impacts are the natural world and the well-being of humans.

Since then, air pollution has led to a rise in human exposure to dioxin, reaching levels up to 56 times the WHO’s recommended maximum. Humans can consume large amounts of dioxin through food, drink, and the air, which poses a major health concern. Humans have higher levels of dioxin in their hair and placentas. The health effects of e-waste are shown in

Table 1 in direct proportion to its harmfulness. Human health is at serious risk due to an exponential rise in e-waste generation over the past ten years. Because of e-waste, people can become unwell from a variety of sources, including eating, breathing, and most commonly by skin contact.

Table 4 describes the dangerous components of e-waste, human diseases linked to them, and the effects these components have on humans.

The impact of e-waste on human health is one of its main features. This also qualifies as a component of the environment. The air, water, and soil are among the primary environmental elements that are impacted by inappropriate management of electronic trash. Ineffective waste management leads to the creation of landfills, the discharge of hazardous chemicals into the environment and negative health consequences on people

Informal e-waste dismantling, shredding, or melting releases dust and chemicals, including dioxins, into the atmosphere that aggravate respiratory conditions and cause air pollution. Electronic garbage emits difficult-to-handle, ultrafine particles that can cause cancer and other health problems in both humans and animals. These wastes are very dangerous, especially for people handling them. Air pollution has been rising substantially as a result of this waste. Over time, pollution of the soil, water, and air causes harm to the ecosystem.

Heavy metals and flame retardants from electronic debris can contaminate groundwater and crops that are cultivated nearby or in the future by leaking into landfills and abandoned places. When heavy metals are present in the soil, crops may absorb poisons, which can lead to disease and lower agricultural productivity. Those who depend on nature also had internal problems as a result of the threat to plants and animals.

Heavy metals like mercury, lead, barium, and lithium that have contaminated soil as a result of e-waste are found in groundwater. These heavy metals eventually make their way into lakes, ponds, and rivers once they enter groundwater. Even when towns are located kilometers away from recycling facilities, these paths lead to acidification and toxicity in the water, which is dangerous for plants, animals, and people. It is also challenging to get safe drinking water. The various components of e-waste that are present and have an environment that might disturb and impact the entire ecosystem are shown in

Table 5 [

33].

This chapter describes the poisonous and hazardous materials found in e-waste as well as the harmful effects they have on the environment, including chemicals. This also introduces the environmental risks pollution and other environmental impact that come with various e-waste recycling stages.

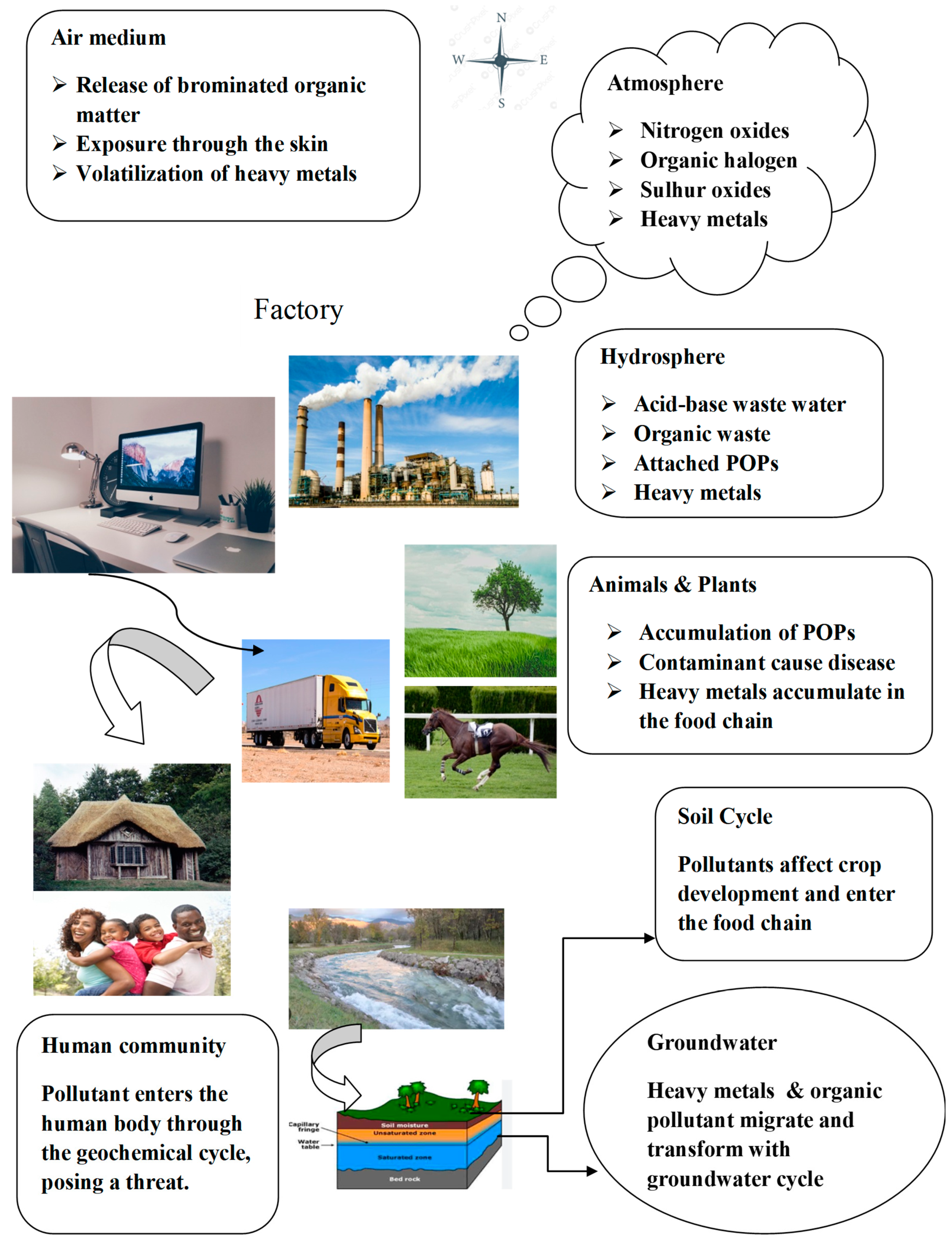

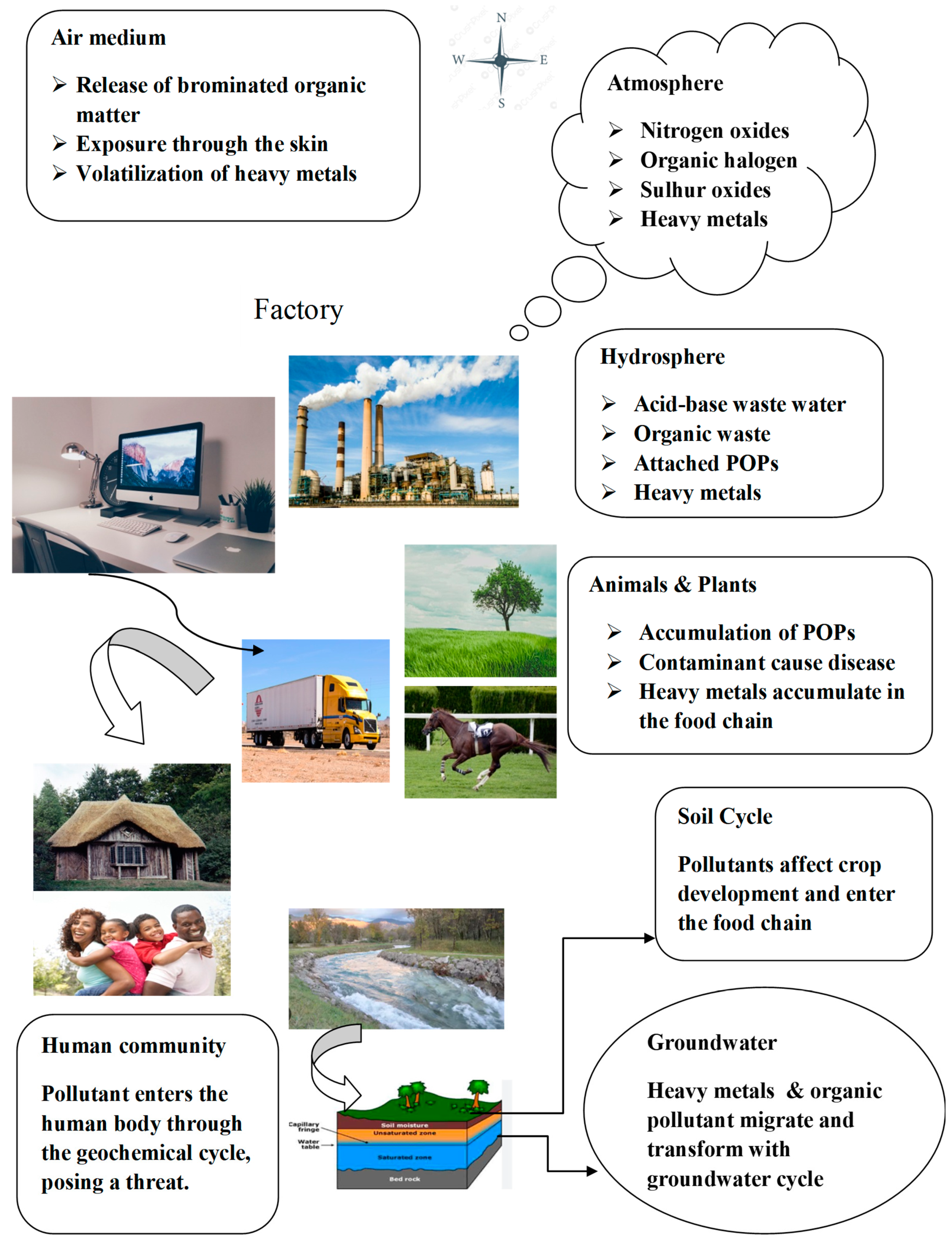

The primary dangers that e-waste presents to the environment and public health are caused by the heavy metals, organic contaminants, and other potentially dangerous materials found in it. The primary hazard is the pollution that is discharged into the atmosphere following the destruction of electrical devices during official or informal disassembly procedures. Pollutants are released into the air, dust, soil, and water during the processing of e-waste. Subsequently, these contaminants may reach the human body through biological chains and geochemical cycles (

Figure 12). Pollutants of many kinds, including heavy metals, persistent organic pollutants, and dust volatilization, can be spread through the air. Dioxins, heavy metals, and components of nitrogen and sulfur are emitted into the environment during combustion. In the end, these pollutants will build up in the groundwater, vegetation, and animal community, posing health risks to both people and animals, as shown in

Figure 12.

Children in Vietnam’s unofficial e-waste treatment hamlet consumed 3.9 times as much Pd, Cd, Cr, Ni, and As per day on average as children in the reference village (p<0.001).Heavy metals were created during the dismantling process of e-waste, according to a survey conducted in Wenling, Zhejiang, China, one of the largest e-waste dismantle sites in China and a commercial grain production area. There was an increase of 0.11, 11.81, 1.01, and 6.82 mg kg-1 in the average soil concentrations of Cd, Cu, Ni, and Zn between 2006 and 2016. According to a report from Guiyu, China, the release of polychlorinated biphenyls during the recycling of electronic debris was the primary source of human exposure. Even though recycling e-waste requires advanced technologies, it can be difficult to regulate the complex contaminants created throughout the process. Because of the intricate disassembly procedure, there are problems with leftover organic residue and heavy metals in the air, land, and water. A negative pressure hood system can lessen worker exposure to dangerous particles including PBDEs, but there may still be a risk to their health. A study was conducted to determine the presence of flame retardants and organic phosphates in the soil, sewage, and outdoor air near official e-waste disposal facilities. These facilities require regular waste incineration, e-waste breakdown and recycling, and authorized waste dumping. Long-term environmental concerns may arise from some materials utilized in the recycling of e-waste. These components consist of bottom ash, floating dust, combustion fumes, leachate from hydrometallurgy, suspended particulate matter, waste water from crushing and disassembling machinery, waste lipids from various chemical operations, and cyanide leaching [

63].

5. Challenges and Perspectives

Reusing and recycling e-waste materials have increased recently in an effort to implement the circular economy (CE) idea. There is a great deal of potential to recycle REEs along with other elements including Cu, Fe, Ag, Au, Pd, and Al, even with the increasing contamination of REEs due to improper disposal of the increasing amount of e-waste. Solvent extraction (SX) is now the most widely utilized technique for removing REE from e-waste. SX has a number of drawbacks despite being widely used in commerce. For instance, it uses a lot of toxic and/or flammable solvents, which could be extremely dangerous for both human health and the environment. Due to their low volatility and non-flammability, ILs are seen as a greener solution to organic solvents for this issue. Nonetheless, a number of significant obstacles still need to be overcome, including the scarcity of true e-waste data for IL extraction, the recycling and reuse of ILs following the extraction of REEs, and the high cost of large fluorinated ILs. Thus, more investigation is required to gather information on the extraction effectiveness and selectivity of TSILs on an industrial scale, particularly in relation to actual e-waste such fluorescent powder, NdFeB magnet, and SmCo magnet. The higher extraction efficiency of acidic extratants makes them more effective than neutral ones. When using ILs as diluents, soluble extractants like DODGAA are advised. By mixing several ILs, it is possible to separate REEs selectively. Not only that, but quaternary ammonium or phosphonium based ILs, which are non-fluorinated hydrophobic and have long alkyl chains, may reduce their cost. Moreover, primary amines are better than quaternary ammonium or phosphonium-based ILs due to their extremely basic character. A certain metal can be selectively targeted by an IL by using the right cation and anion combination. Prior to commercial application, it is imperative to verify the reusability of TSILs through several loading/stripping tests, as well as their extractability and selectivity. If it is possible to distinguish LREEs from HREEs, it is imperative to separate intra-REEs for LREEs and HREEs in order to obtain high selectivity. Queen University Belfast and serne technologies recently received a patent for utilizing TSILs to extract and separate REEs, Nd, and Dy from an acidic aqueous medium [

64].

In developing nations, e-waste can contaminate towns and cities, endangering public health and the environment. Using Guiyu, China as an example, has a high concentration of dioxins, which cause cancer, and a big volume of e-waste. Numerous dangerous materials might be found in the e-waste. Hazardous procedures including burning, crushing, or acid baths are caused by the entry of poisonous compounds like Pb, Cd, Hg, and As into the environment and ground. Because of the potential for hazardous substances to represent a serious harm to both human health and the ecology, it is illegal to dispose of electronic trash in landfills in the United States and other modern countries. Furthermore, the majority of developing countries do not have these regulations and reject a significant portion of these imports. To enhance e-waste management conditions, the US Protection Agency (EPA) and the Taiwan Environmental Protection Agency arranged a workshop for 11 countries in the international E-waste management network in 2018. Their goals are to evaluate the markets for e-waste, safeguard the environment, and improve cooperation with manufacturers and other innovative technology [

65].

6. Prospects

The validation dataset included common electronic trash products such laptops, keyboards, mice, and monitors. Accurate prediction can also aid in the identification of different types of e-waste, which advances knowledge of the composition and management of e-waste. A “business as usual” scenario predicts that by 2050, there would be more than twice as much e-waste produced. To be sustainable, the processes involved in the creation, utilization, and disposal of e-waste must be greatly altered. The lack of collecting and withdrawal procedures causes a big gap between the volume of data produced and the capacity for recycling [

66].

The goal of this application is to increase human-computer interaction by transforming cognitive processes into a digital paradigm. Algorithms that learn on their own, such data mining, natural language processing, and pattern recognition, allow computers to carry out tasks formerly exclusive to humans. Through their user interfaces, machines and people can interact. Natural user interfaces, like gestures, make devices more engaging and user-friendly by enabling people to use them through instinctive and natural behaviors. The industry’s future direction places the human at the center of the system while integrating technologies.

The computational capabilities of quantum computing are derived from their collective features, including interference and amusement. Users can also better understand behavior and motivations through interaction with other users. Devices that carry out quantum computations are known as quantum computers, and their primary function is to compute the likelihood of an object state prior to measurement [

67].

7. Conclusions

Technology now has a great reliance on rare earth elements (REEs) since it is more dependent on electronics than it has ever been. Electronic devices break down too soon, creating massive amounts of e-waste annually, which calls for the creation of a waste management strategy specifically for this type of trash. Due to the growing global shortage and supply issues, the usage of rare earth elements (REEs) in a range of industries, including aerospace, healthcare, transportation, and communications, has received a lot of attention in the last 20 years. The ecosystem can be severely harmed by inappropriate treatment and storage of e-waste because aquatic habitats include REEs or even more dangerous metals (like Pb and Hg). Rare earth element demand is expected to rise sharply in the near future due to fast emerging green technologies like solar panels, wind turbines, electric car batteries, and other applications where these metals are widely used, along with rising pricing.

In terms of environmentally friendly separation and reduced hazards of toxicity and explosion, inorganic/volatile solvents (IL) show promise as a substitute for the selective recovery of rare earth elements (REEs). Recycling and recovering rare earth elements (REEs) from garbage is a crucial issue because of the growing demand for these elements and their growing use in green technologies. The most popular methods for recovering rare earth elements (REEs) from electronic trash were examined in this study. These methods included hydromettalurgical process, siderophores, pyromettalurgical process, bioleaching, and biosorption. Warm temperature recycling offers a bright future, but there are a number of clear challenges that need to be overcome, including (i) the wide variety of wastes produced; (ii) the influence of contaminants on the recycling process; (iii) optimization for mutual separation of REs (Nd, Dy, and Pr); and (iv) viability (economics and lifecycle). The need for REEs’ clean technologies will first decrease before increasing. The need for REE from clean technologies is anticipated to surpass 50 kt REO in 2030, despite the fact that it will decrease from 33 kt in 2016 to 32 kt in 2020 and then increase to 34 kt in 2025.

This study investigated the spatial properties of rare earth elements (REEs) in the Yangding River, a typical urban river, as well as the relationships between land use and human-derived REEs in river water. The presence of rare earth elements (REEs) has an impact on Cotonou wastewater, with heavy REEs being more abundant than light REEs. Europium and gadolinium were the two primary REEs. In conclusion, it is currently evident that several programs have been launched globally to address the issue of e-waste. More study should be done, in particular, to investigate creative ways to handle e-waste in order to make it more persistent, sustainable, and environmentally benign.

Acknowledgement

Under the terms of an Excellence Research Grant (Code: TU NPAR-079/080-ERG-11), AB acknowledges receiving financial support from the TU Rector Office research division.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest, either present or future, according to the writers.

References

- Omodara, L. , Pitkäaho, S., Turpeinen, E. M., Saavalainen, P., Oravisjärvi, K., & Keiski, R. L. (2019). Recycling and substitution of light rare earth elements, cerium, lanthanum, neodymium, and praseodymium from end-of-life applications - A review. In Journal of Cleaner Production (Vol. 236). Elsevier Ltd. [CrossRef]

- Akcil, A. , Ibrahim, Y. A., Meshram, P., Panda, S., & Abhilash. (2021). Hydrometallurgical recycling strategies for recovery of rare earth elements from consumer electronic scraps: a review. In Journal of Chemical Technology and Biotechnology (Vol. 96, Issue 7, pp. 1785–1797). John Wiley and Sons Ltd. [CrossRef]

- Wang, K. , Adidharma, H., Radosz, M., Wan, P., Xu, X., Russell, C. K., Tian, H., Fan, M., & Yu, J. (2017). Recovery of rare earth elements with ionic liquids. In Green Chemistry (Vol. 19, Issue 19, pp. 4469–4493). Royal Society of Chemistry. [CrossRef]

- Alonso, E. , Sherman, A. M., Wallington, T. J., Everson, M. P., Field, F. R., Roth, R., & Kirchain, R. E. Evaluating rare earth element availability: A case with revolutionary demand from clean technologies. Environmental Science and Technology 2012, 46, 3406–3414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jowitt, S. M. , Werner, T. T., Weng, Z., & Mudd, G. M. (2018). Recycling of the rare earth elements. In Current Opinion in Green and Sustainable Chemistry (Vol. 13, pp. 1–7). Elsevier B.V. [CrossRef]

- Binnemans, K. , Jones, P. T., Blanpain, B., van Gerven, T., Yang, Y., Walton, A., & Buchert, M. (2013). Recycling of rare earths: A critical review. In Journal of Cleaner Production (Vol. 51, pp. 1–22). Elsevier Ltd. [CrossRef]

- Mudali, U. K. , Patil, M., Saravanabhavan, R., & Saraswat, V. K. Review on E-waste Recycling: Part II—Technologies for Recovery of Rare Earth Metals. Transactions of the Indian National Academy of Engineering 2021, 6, 613–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudali, U. K. , Patil, M., Saravanabhavan, R., & Saraswat, V. K. Review on E-Waste Recycling: Part I—A Prospective Urban Mining Opportunity and Challenges. Transactions of the Indian National Academy of Engineering 2021, 6, 547–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, R. , Natasha, Fahad, S., Hashmi, M. Z., Wahid, A., Adnan, M., Mubeen, M., Khan, N., Rehmani, M. I. A., Awais, M., Abbas, M., Shahzad, K., Ahmad, S., Hammad, H. M., & Nasim, W. (2019). Trends of electronic waste pollution and its impact on the global environment and ecosystem. In Environmental Science and Pollution Research (Vol. 26, Issue 17, pp. 16923–16938). Springer Verlag. [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, C. E. D. , Almeida, J. C., Lopes, C. B., Trindade, T., Vale, C., & Pereira, E. (2019). Recovery of rare earth elements by carbon-based nanomaterials—a review. In Nanomaterials (Vol. 9, Issue 6). MDPI AG. [CrossRef]

- Kaim, V. , Rintala, J., & He, C. (2023). Selective recovery of rare earth elements from e-waste via ionic liquid extraction: A review. In Separation and Purification Technology (Vol. 306). Elsevier B.V. [CrossRef]

- Vishwakarma, S. , Kumar, V., Arya, S., Tembhare, M., Rahul, Dutta, D., & Kumar, S. E-waste in Information and Communication Technology Sector: Existing scenario, management schemes and initiatives. Environmental Technology and Innovation, 2022; 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahabuddin, M. , Uddin, M. N., Chowdhury, J. I., Ahmed, S. F., Uddin, M. N., Mofijur, M., & Uddin, M. A. (2023). A review of the recent development, challenges, and opportunities of electronic waste (e-waste). In International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology (Vol. 20, Issue 4, pp. 4513–4520). Institute for Ionics. [CrossRef]

- Jain, M. , Kumar, D., Chaudhary, J., Kumar, S., Sharma, S., & Singh Verma, A. Review on E-waste management and its impact on the environment and society. Waste Management Bulletin 2023, 1, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opare, E. O. , Struhs, E., & Mirkouei, A. (2021). A comparative state-of-technology review and future directions for rare earth element separation. In Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews (Vol. 143). Elsevier Ltd. [CrossRef]

- Dev, S. , Sachan, A., Dehghani, F., Ghosh, T., Briggs, B. R., & Aggarwal, S. (2020). Mechanisms of biological recovery of rare-earth elements from industrial and electronic wastes: A review. In Chemical Engineering Journal (Vol. 397). Elsevier B.V. [CrossRef]

- Balaram, V. Rare earth elements: A review of applications, occurrence, exploration, analysis, recycling, and environmental impact. Geoscience Frontiers 2019, 10, 1285–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuppaladadiyam, S. S. V. , Thomas, B. S., Kundu, C., Vuppaladadiyam, A. K., Duan, H., & Bhattacharya, S. (2024). Can e-waste recycling provide a solution to the scarcity of rare earth metals? An overview of e-waste recycling methods. In Science of the Total Environment (Vol. 924). Elsevier B.V. [CrossRef]

- Brewer, A. , Dror, I., & Berkowitz, B. Electronic waste as a source of rare earth element pollution: Leaching, transport in porous media, and the effects of nanoparticles. Chemosphere, 2022; 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouziotis, A. A. , Giarra, A., Libralato, G., Pagano, G., Guida, M., & Trifuoggi, M. Toxicity of rare earth elements: An overview on human health impact. In Frontiers in Environmental Science (Vol. 10). Frontiers Media S.A. 2022; 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atinkpahoun, C. N. H. , Pons, M. N., Louis, P., Leclerc, J. P., & Soclo, H. H. Rare earth elements (REE) in the urban wastewater of Cotonou (Benin, West Africa). Chemosphere, 2020; 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X. , Han, G., Liu, J., & Zhang, S. Spatial Distribution and Sources of Rare Earth Elements in Urban River Water: The Indicators of Anthropogenic Inputs. Water (Switzerland), 2023; 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atinkpahoun, C. N. H. , Pons, M. N., Louis, P., Leclerc, J. P., & Soclo, H. H. Rare earth elements (REE) in the urban wastewater of Cotonou (Benin, West Africa). Chemosphere, 2020; 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jyothi, R. K. , Thenepalli, T., Ahn, J. W., Parhi, P. K., Chung, K. W., & Lee, J. Y. (2020). Review of rare earth elements recovery from secondary resources for clean energy technologies: Grand opportunities to create wealth from waste. In Journal of Cleaner Production (Vol. 267). Elsevier Ltd. [CrossRef]

- Dushyantha, N. , Batapola, N., Ilankoon, I. M. S. K., Rohitha, S., Premasiri, R., Abeysinghe, B., Ratnayake, N., & Dissanayake, K. (2020). The story of rare earth elements (REEs): Occurrences, global distribution, genesis, geology, mineralogy and global production. In Ore Geology Reviews (Vol. 122). Elsevier B.V. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B. , Li, Z., & Chen, C. (2017). Global potential of rare earth resources and rare earth demand from clean technologies. In Minerals (Vol. 7, Issue 11). MDPI AG. [CrossRef]

- Ambaye, T. G. , Vaccari, M., Castro, F. D., Prasad, S., & Rtimi, S. (2020). Emerging technologies for the recovery of rare earth elements (REEs) from the end-of-life electronic wastes: a review on progress, challenges, and perspectives. In Environmental Science and Pollution Research (Vol. 27, Issue 29, pp. 36052–36074). Springer. [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, M. , & Simone, M. I. Developing New Inexpensive Room-Temperature Ionic Liquids with High Thermal Stability and a Greener Synthetic Profile. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 12637–12648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T. , Doert, T., Wang, H., Zhang, S., & Ruck, M. (2021). Inorganic Synthesis Based on Reactions of Ionic Liquids and Deep Eutectic Solvents. In Angewandte Chemie - International Edition (Vol. 60, Issue 41, pp. 22148–22165). John Wiley and Sons Inc. [CrossRef]

- Sintra, T. E. , Gantman, M. G., Ventura, S. P. M., Coutinho, J. A. P., Wasserscheid, P., & Schulz, P. S. Synthesis and characterization of chiral ionic liquids based on quinine, L-proline and L-valine for enantiomeric recognition. Journal of Molecular Liquids 2019, 283, 410–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- vander Hoogerstraete, T. , & Binnemans, K. Highly efficient separation of rare earths from nickel and cobalt by solvent extraction with the ionic liquid trihexyl(tetradecyl)phosphonium nitrate: A process relevant to the recycling of rare earths from permanent magnets and nickel metal hydride batteries. Green Chemistry 2014, 16, 1594–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adel, A. (2022). Future of industry 5.0 in society: human-centric solutions, challenges and prospective research areas. In Journal of Cloud Computing (Vol. 11, Issue 1). Springer Science and Business Media Deutschland GmbH. [CrossRef]

- Jain, M. , Kumar, D., Chaudhary, J., Kumar, S., Sharma, S., & Singh Verma, A. Review on E-waste management and its impact on the environment and society. Waste Management Bulletin 2023, 1, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, V.N. E-waste hazard: The impending challenge. Indian journal of occupational and environmental medicine 2008, 12, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ari, V. 2016. A review of technology of metal recovery from electronic waste. E‐Waste in transition–From pollution to resource.

- Ari, V. 2016. A review of technology of metal recovery from electronic waste–From pollution to resource.

- Yang, H. , Huo, X. , Yekeen, T.A., Zheng, Q., Zheng, M., Xu, X. Effects of lead and cadmium exposure from electronic waste on child physical growth. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2013, 20, 4441–4447. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, K. , Goldizen, F. C., Sly, P.D., Brune, M.N., Neira, M., Van den Berg, M., Norman, R. E. Health consequences of exposure to E-waste: a systematic review. Lancet Glob Health 2013, 1, 350–361. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J. , Bertram, J. , Schettgen, T., Heitland, P., Fischer, D., Seidu, F., Felten, M., Kraus, T., Fobil, J.N., Kaifie, A. Arsenic burden in E-waste recycling workers cross-sectional study at the Agbogbloshie E-waste recycling site. Ghana. Chemosphere 2020, 261, 127712. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kumarathilaka, P. , Seneweera, S. , Meharg, A., Bundschuh, J. Arsenic speciation dynamics in paddy rice soil-water environment: sources, physicochemical, and biological factors-a review. Water Res. 2018, 140, 403–414. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- El-Ghiaty, M.A. , El-Kadi, A. O. Arsenic: Various species with different effects on cytochrome P450 regulation in humans. EXCLI J. 2021, 20, 1184. [Google Scholar]

- Debnath, B. , Saha, I., Mukherjee, T., Mitra, S., Das, A., & Das, A. 2021. Sorbents from waste materials: a circular economic approach. In Sorbents Materials for Controlling Environmental Pollution (pp. 285-322). Elsevier.

- “Disposal of Asbestos, Chemicals, Oil, Trade and e-Waste - Parkes Shire Council.” https://www.parkes.nsw.gov.au/environment/waste-recycling/waste-facilities/disposal-of-chemicals-oil-trade-and-E-waste/ (accessed Feb 14, 2022).

- Julander, A. , Lundgren, L. , Skare, L., Grandér, M., Palm, B., Vahter, M., Lidén, C. Formal recycling of E-waste leads to increased exposure to toxic metals: an occupational exposure study from Sweden. Environ. Int. 2014, 73, 243–251. [Google Scholar]

- Segev, O. , Kushmaro, A. , Brenner, A. Environmental impact of flame retardants (persistence and biodegradability). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2009, 6, 478–491. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 97% of collected E-waste recycled for useful applications - PRé Sustainability.” https:// pre-sustainability.com/articles/almost-all-collected-E-waste-recycled/ (accessed Feb. 20, 2022).

- Tue, N.M. , Matsushita, T. , Goto, A., Itai, T., Asante, K.A., Obiri, S., Mohammed, S., Tanabe, S., Kunisue, T. Complex mixtures of brominated/chlorinated diphenyl ethers and dibenzofurans in soils from the Agbogbloshie E-waste site (Ghana): Occurrence, formation, and exposure implications. Environ. Sci. Tech. 2019, 53, 3010–3017. [Google Scholar]

- Salhofer, S. E-waste collection and treatment options: A comparison of approaches in Europe, China and Vietnam. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J. , Zhang, B. Air pollution and healthcare expenditure: Implication for the benefit of air pollution control in China. Environ. Int. 2018, 120, 443–455. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, X. , Huo, X., Xu, X., Liu, D., Wu, W. E-waste lead exposure and children’s health in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 734, 139286. [Google Scholar]

- “A Closer Look: Lithium-Ion Batteries in E-waste.” https://www.simslifecycle.com/ 2019/05/21/a-closer-look-lithium-ion-batteries-in-E-waste/ (accessed Feb 20, 2022).

- Saha, L. , Kumar, V., Tiwari, J., Rawat, S., Singh, J., Bauddh, K. Electronic waste and their leachates impact on human health and environment: Global ecological threat and management. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2021, 24, 102049. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, K. , Schnoor, J.L., Zeng, E.Y. E-waste recycling: where does it go from here? Environ. Sci. Tech. 2012, 46, 10861–10867. [Google Scholar]

- Stapleton, H.M. , Allen, J., G., Kelly, S.M., Konstantinov, A., Klosterhaus, S., Watkins, D., McClean, M.D., Webster, T.F. Alternate and new brominated flame retardants detected in US house dust. Environ. Sci. Tech. 2008, 42, 6910–6916. [Google Scholar]

- Tai, W. , He, L., Zhang, X., Pu, J., Voronin, D., Jiang, S., Zhou, Y., Du, L. Characterization of the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of 2019 novel coronavirus: implication for development of RBD protein as a viral attachment inhibitor and vaccine. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2020, 17, 613–620. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- “Managing And Reducing E-Waste From PCBs| EC Electronics.” https:// ecelectronics.com/news/managing-and-reducing-E-waste-from-pcbs (accessed Feb 20, 2022).

- E-Waste – Silicon Valley Toxics Coalition.” https://svtc.org/our-work/E-waste/ (accessed Feb. 20, 2022).

- Kurup, A.R. , Senthil Kumar, K., Effect of recycled PVC fibres from electronic waste and silica powder on shear strength of concrete. Journal of Hazardous, Toxic, and Radioactive Waste 2017, 21, 06017001. [Google Scholar]

- Stapleton, H.M. , Allen, J.G., Kelly, S.M., Konstantinov, A., Klosterhaus, S., Watkins, D., McClean, M.D., Webster, T.F. Alternate and new brominated flame retardants detected in US house dust. Environ. Sci. Tech. 2008, 42, 6910–6916. [Google Scholar]

- Decharat, S. Urinary mercury levels among workers in E-waste shops in Nakhon Si Thammarat Province, Thailand. J. Prev. Med. Public Health 2018, 51, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. , Tian, Z., Zhu, H., Cheng, Z., Kang, M., Luo, C., Li, J., Zhang, G. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in soils and vegetation near an E-waste recycling site in South China: concentration, distribution, source, and risk assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 2012, 439, 187–193. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Quiles, D. , Tovar-Sánchez, A. Are sunscreens a new environmental risk associated with coastal tourism? Environ. Int. 2015, 83, 158–170. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, K. , Tan, Q., Yu, J., & Wang, M. (2023). A global perspective on e-waste recycling. In Circular Economy (Vol. 2, Issue 1). Elsevier B.V. [CrossRef]

- Kaim, V. , Rintala, J., & He, C. (2023). Selective recovery of rare earth elements from e-waste via ionic liquid extraction: A review. In Separation and Purification Technology (Vol. 306). Elsevier B.V. [CrossRef]

- Naik, S. , & Satya Eswari, J. Electrical waste management: Recent advances challenges and future outlook. Total Environment Research Themes, 2022; 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murthy, V. , & Ramakrishna, S. A Review on Global E-Waste Management: Urban Mining towards a Sustainable Future and Circular Economy. Sustainability (Switzerland), 2022; 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adel, A. (2022). Future of industry 5.0 in society: human-centric solutions, challenges and prospective research areas. In Journal of Cloud Computing (Vol. 11, Issue 1). Springer Science and Business Media Deutschland GmbH. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).