Introduction

Diabetes is a worrisome health problem today as nearly half a billion people worldwide suffer from diabetes, including big countries such as China and the United States. Data from the International Diabetes Federation states that 1 in 11 people aged 20-79 years has diabetes and 1 in 2 adults is at risk of undiagnosed diabetes (International Diabetes Federation, 2019). Indonesia is included in the 10 countries with the largest diabetes sufferers in the world (Pusat Data dan Informasi Kementerian Kesehatan Republik Indonesia, 2020). Studies on the effectiveness of natural extracts as antidiabetic have also been widely studied as an effort to manage the risk of diabetes with the discovery of several kinds of natural product compounds such as indole alkaloids which have been confirmed to hold specific antidiabetic effectiveness in vitro and in vivo (Zhu et al., 2021).

Exploration of natural ingredients as antidiabetic is also developed by taking attention to the potential of natural ingredients available locally. As Chinese researchers studied the Chinese Sesbania cannabina plant, as well as scientists in Africa, studied the potential of Ajuga remota Benth leaf extract as antidiabetic (Li et al., 2021; Tafesse et al., 2017). Indonesia as a country with high biodiversity has several types of herbal plants that have anti-diabetic properties such as leaf extracts of Annona muricata (Soursop), Andrographis paniculata (Sambiloto), Averrhoa bilimbi (Belimbing wuluh), Diospyros kaki (Persimmon fruit/kesemek) and Curcuma xanthorrhiza (Temulawak) (Firdausya & Amalia, 2020). The potential of Indonesia’s natural resources as antidiabetic medicine is not only limited to these commodities but also other local potentials that are unique to certain areas, such as raru (Vatica perakensis) bark extract from Sumatra.

There are several types of wood that are classified as Raru wood, including Shorea maxwelliana, Shorea faguetiana. Cotylelobium melanoxylon, Vatica songa from the family Dipterocarpaceae, and Garcinia sp. from the Guttifera family(Pasaribu, 2011). Raru (Cotylelobium sp.) bark extract is known to have antioxidant properties. This bark is usually used by the community as a mixture of tuak (traditional drinks). Local people also believe that Raru bark can be used as a glucose-lowering agent (antidiabetic) (Pasaribu & Setyawati, 2011), (Pasaribu et al., n.d.). Extract of Raru stem bark of Vatica pauciflora Blume and Cotylelobium sp. have been tested in vitro and in vivo as antidiabetic (Riris & Napitupulu, 2017).

The potential of Raru extract as an antidiabetic continues to be developed, especially with the development of research on drug formulations aimed at accelerating the effectiveness of anti-diabetic drugs through nanoparticles (NPs) loading techniques. Several research results regarding the use of nanoparticles as antidiabetic loading agents have been studied, such as nano chitosan, nano Zinc oxide, nano solid lipids, and nanofibrous scaffold (El-bagory et al., 2019; Emin et al., 2021; Iqbal et al., 2021; Zhu et al., 2021). The use of polymeric NPs acts as a carrier of drugs to target sites by reducing the adverse side effects and are used as the entrapment antidiabetic ingredients and release more selectively to target cells(Ambalavanan et al., 2020). The results revealed that the approach of the use of nanoparticles as antidiabetic loaders seems to be a promising strategy to enhance the oral efficacy of oral antidiabetics. However, pore size and morphology of the carriers are the main factors in drug loading and release (Avila et al., 2020), including in using anti-diabetic agent nanoparticles.

One of the materials that have a porous structure and high adsorption capacity is activated carbon. Activated carbon is amorphous carbon material possessing a large surface area. Activated carbon is considered inexpensive, commercially available, non-toxic (Miriyala et al., 2017) and consists of a three-dimensional interrelated pore structure in a large amount with various sizes on a nanometer scale which is classified as micropores (<2 nm), mesopores (2–50 nm) and macropores (>50 nm) (Inagaki, 2009). It has been employed as an adsorbent for the removal of smell, coloration, and impurities in the reaction mixture (Tanemura & Rohand, 2020).

The use of activated carbon as drug delivery had been studied in 1997 as an anticancer drug and applied to digestive cancer in patients in whom the operation is contraindicated (Hagiwara et al., 1997). Recently, a drug-encapsulated carbon (DECON) has been developed as an enhancer of antiviral drug delivery of acyclovir (ACV). The results showed that DECON reduced dosing frequency, shortened treatment duration, and improved therapeutic efficacy than topical or systemic antivirals alone (Yadavalli et al., 2019). Although the use of activated carbon has been extensively studied as a drug delivery agent, some studies have used carbon microparticles and have been tested to contain fever medications such as ibuprofen, paracetamol, and high blood pressure medication carvedilol (Hagiwara et al., 1997; Miriyala et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2013). However, to the best of our knowledge, a study which reported the effectiveness of activated carbon on the nanoscale and used as an antidiabetic has not been reported. In this study, we successfully elaborated the performance of nano-activated carbon and Raru (Vatica perakensis) bark extract as the antidiabetic agents which tested in vivo. This study is expected to encourage the utilization of medicinal plants from Indonesia and enrich the oral drug formulation technology with high effectiveness.

Experimental

Material and Methods

The stem bark of Raru (Vatica perakensis) was collected from the locality of Riau Province, Indonesia. Nano-activated carbon was made from tapioca flour. Sprague Dawley rats, male, aged ± 12 weeks, the weight of ± 250-350 grams were obtained from the Animal and Food Testing Center of the Food and Drug Supervisory Agency of Indonesia. Animals were placed in cages with 2-3 mice per cage in room temperature of 25°C with a humidity of 60-70%. Animals were fed with 15 gr of conventional diets/day and water ad libitum.

Ethanol and citrate buffer were purchased from Bratachem, Streptozotocin (STZ), hematoxylin-eosin, paraformaldehyde, immunohistochemistry, glibenclamide® and a test strip of Accu Check ® for observing blood glucose levels.

General Procedure

Activated Carbon Preparation and Characterization

The carbonization technique used was hydrothermal carbonization. Modified tapioca flour (denoted as Mocaf) was carbonized at a temperature of 250°C for 6 h using water as media which placed as much as a third of digester volume. The resultant hydro-carbon is then rinsed with hot water until pH is 7. Activation was employed using water vapor at a temperature of 800°C for 30 minutes to obtain activated carbon-derived tapioca. The activated carbon was rinsed using distilled water until the pH reached 6-7. The morphology of activated carbon was observed using Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) Type Zeiss EVO 50 (Zeiss, Germany) and was operated at 10 kV. Crystallite structure, porosity, particle size and elemental analysis of activated carbon were observed using X-Ray Diffractometer (XRD); Surface Area Analyzer; Particle Size Analyzer (PSA), and X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF), respectively. The observed physical properties of activated carbon include moisture content, ash content, fixed carbon, volatile content, pH, iodine adsorption capacity and then compared with Indonesian National Standard (SNI).

In Vivo Antidiabetic Activity

Sprague Dawley rats were fasted for 16 h before induction using STZ streptozotocin (STZ) (Nacalai). Blood glucose levels of animals were checked using the Accu check ® test strip to determine the basal condition of the experimental animals. Animals were induced with streptozotocin (STZ) (Nacalai) at a dose of 40-45 mg/kg body weight, dissolved in Citrate Buffer 0.05 M pH 4.5, and were injected intraperitoneally. After 48 h, the sugar levels were observed using Accu Check ® and their serum was taken to check blood glucose levels.

Sprague Dawley rats were randomly divided into six groups of 7 each and the details were as follows:

- -

Group I: Normal group, the rats were orally administered distilled water and a common pellet diet (n= 7)

- -

Group II: Positive control group, rats were orally administered STZ and glibenclamide® (n=7)

- -

Group III: Negative control group, rats orally administered STZ and distilled water (n=7)

- -

Group IV: Treatment 1, rats orally administered STZ and 350 mg/kg bodyweight of Raru extract

- -

Group V: Treatment 2, rats orally administered STZ and 350 mg/kg bodyweight of Raru extract and nano-activated carbon in a ratio of 75:25 (w/w).

- -

Group VI: Treatment 3, rats orally administered STZ and 350 mg/kg bodyweight of Raru extract and nano-activated carbon in a ratio of 50:50 (w/w).

Treatments were employed for 4 weeks. At the end of treatments, rats were fasted for 16 h, and fasting blood glucose (FBG) levels were detected using Accu Check ® 6 times which are: prior to STZ induction, 48 h after STZ induction, and days 7, 14, 21, and 28 after treatments.

After 4 weeks of feeding, the animals were euthanized using the exsanguination method (anesthetized with ketamine 80 mg/kg body weight and xylazine 10 mg/kg body weight, and blood was taken as much as possible from the heart), and then the pancreas was taken for histopathological examination.

Results and Discussion

Hydrothermal and Activated Carbon Characterization

The characterization includes the physical properties of carbon generated from the hydrothermal process (hydrothermal carbon) and activated carbon produced by activation of hydrothermal carbon using the high temperature of water vapor. The results as described in

Table 1.

During the hydrothermal process, biomass-derived precursors are converted into valuable carbon materials using water as a reaction medium under self-generated pressures (C Falco et al., 2013). Therefore, the moisture content of hydrochar was relatively higher. The hydrothermal carbonization process is a low energetic impact and if we use monosaccharides as raw materials, this process produces carbon microspheres of uniform sizes under very mild process conditions (Pires & García-bordej, 2017). The yield of activated carbon was lower than hydrochar. This result was in good accordance with the previous studies that use hydrothermal carbon as a precursor of activated carbon from tapioca and cassava flour (Pari et al., 2014).

In general, the activated carbon of mocaf meets Indonesian National Standards (

Table 1). Iodine adsorption and fixed carbon of activated carbon were higher than hydrochar. The high value of iodine adsorption was related to the highly microporous activated carbon generated during the activation process (Islam et al., 2015). This porous structure is formed from residual carbon atoms which have arranged themselves into flat aromatic sheets that are cross-linked randomly and the interstices in these irregularly aromatic sheets give rise to the porosity upon which the properties of activated carbon mostly depend (Çeçen, 2014). The porosity development of activated carbon was extremely influenced by the temperature of the hydrothermal process and regardless of parent biomass, whereas the use of higher hydrothermal temperatures led to lower porosity development (C Falco et al., 2013).

The elemental analysis (

Table 2) of hydrothermal carbon exhibited lower content of carbon elements (62%) than activated carbon (86%). This result was in good accordance with the proximate analysis in

Table 1. However, the hydrogen and oxygen contents of hydrothermal carbon were higher than activated carbon. The higher oxygen content of hydrothermal carbon can be attributed to the higher degree of surface oxidation (C Falco et al., 2013). The higher loss of oxygen in activated carbon (final value= 13.55 %) is related to the aromatization process that continues when the temperature increases in the activation process and indicates that furans structures are consumed in the carbonization process (Camillo Falco et al., 2011).

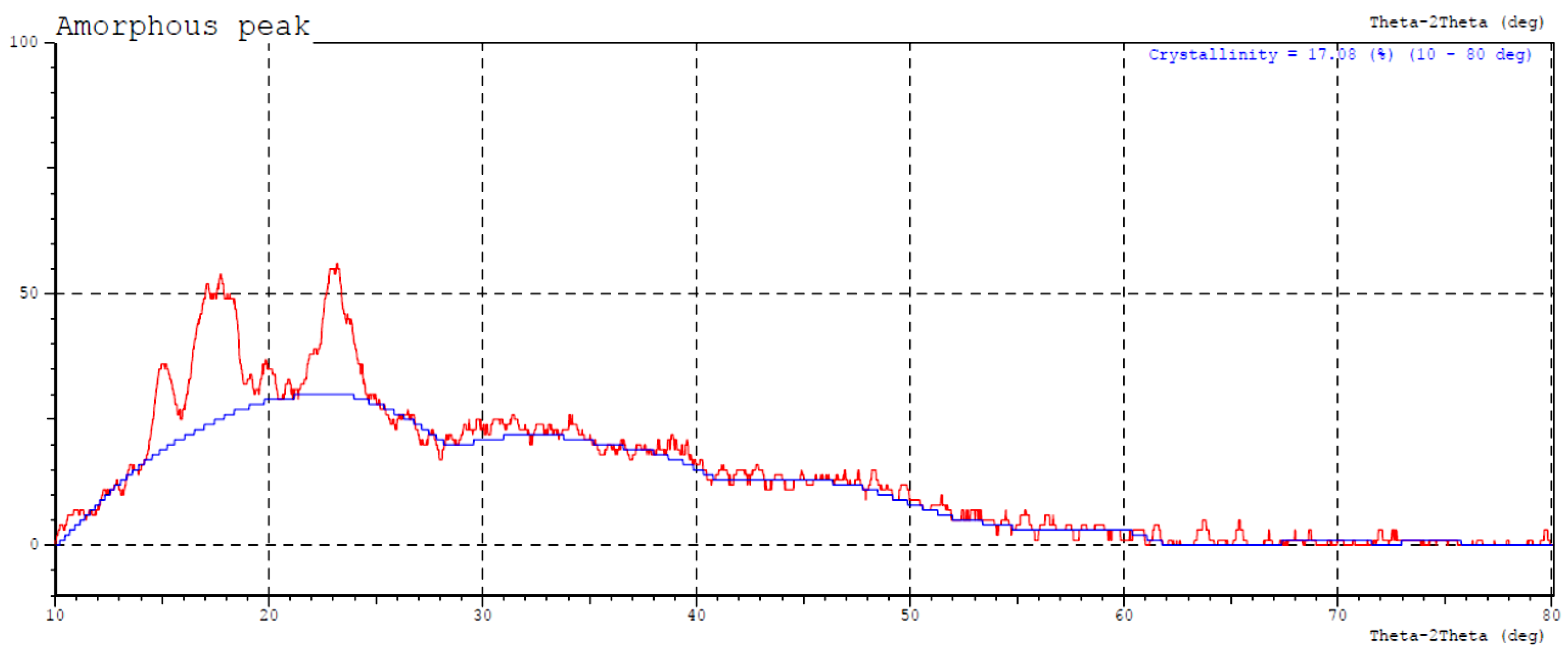

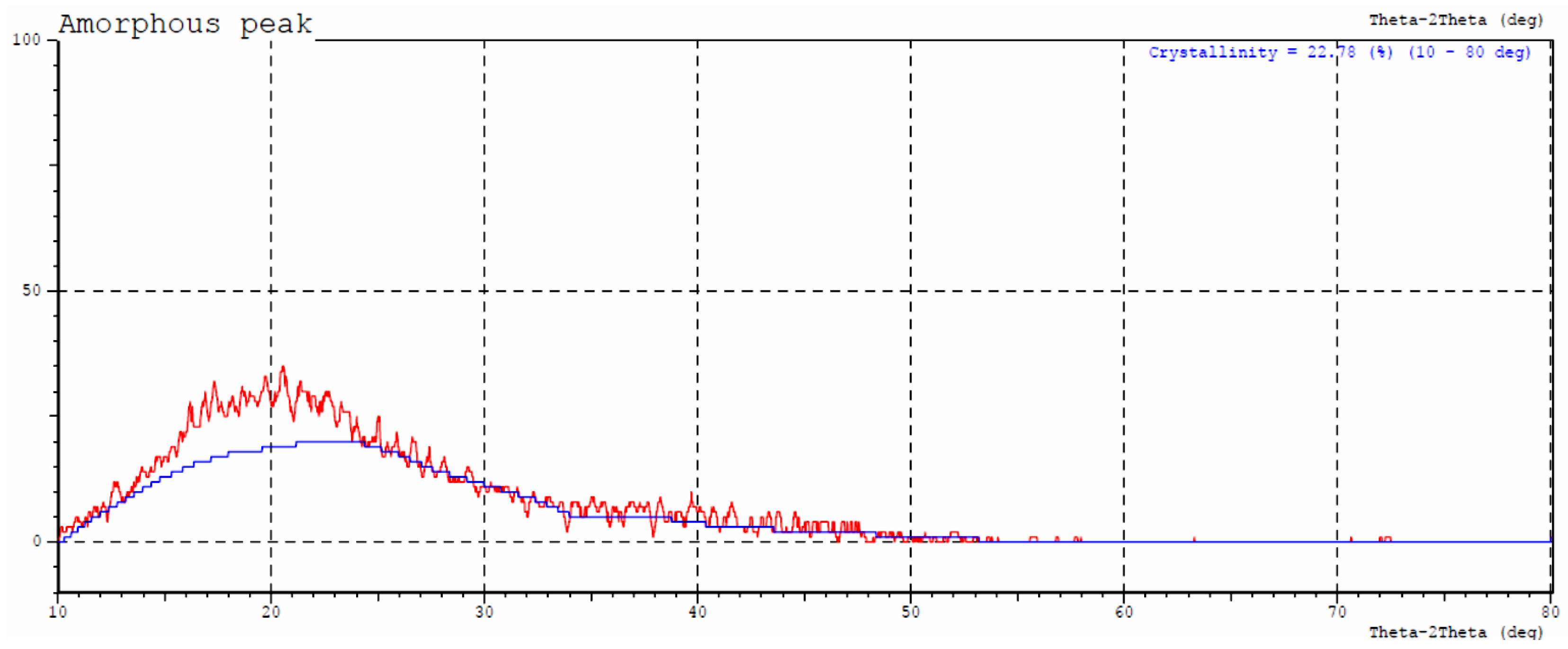

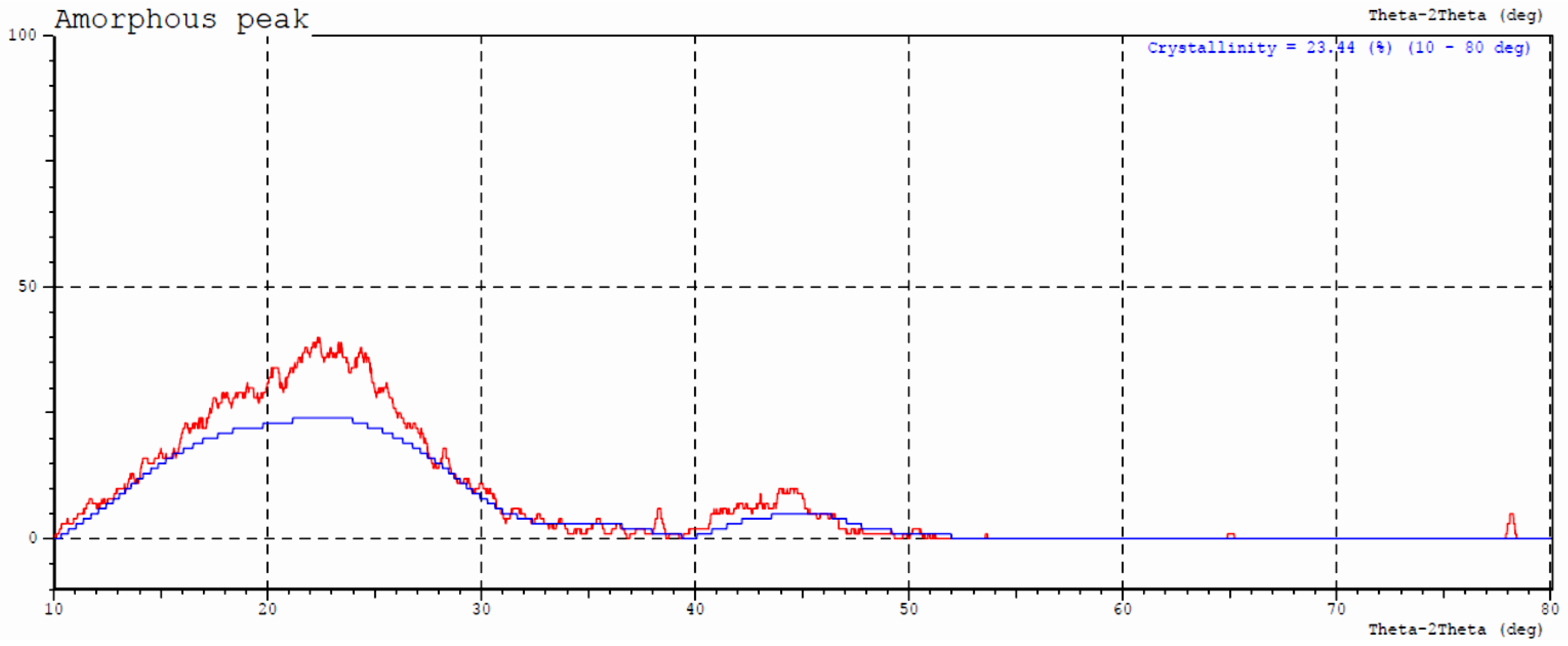

The structural changes that occurred during the carbonization process were also confirmed by XRD analysis. XRD diffractogram showed the differences among raw mocaf, hydrothermal and activated carbon (

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). Hydrothermal carbonization has changed the structure of mocaf into amorphous hydrochar. The further process through activation generated activated carbon with a hexagonal carbon structure as shown in the peak at 2 theta in angles around 24 and 43 degrees (

Figure 3). Observed diffraction peaks ranged from 20 to 46 two theta values correspond to the Braggs reflective plane values (Aravind & Amalanathan, 2021), it is often used as an approach to the analysis of the optical properties of carbon fibers composites (Holmes et al., 2021). There is two types of diffraction peaks at 2 theta values of 22.5 and 43.0 can be ascribed to reflections from the (002) and (110) crystal planes (Yuan et al., 2016).

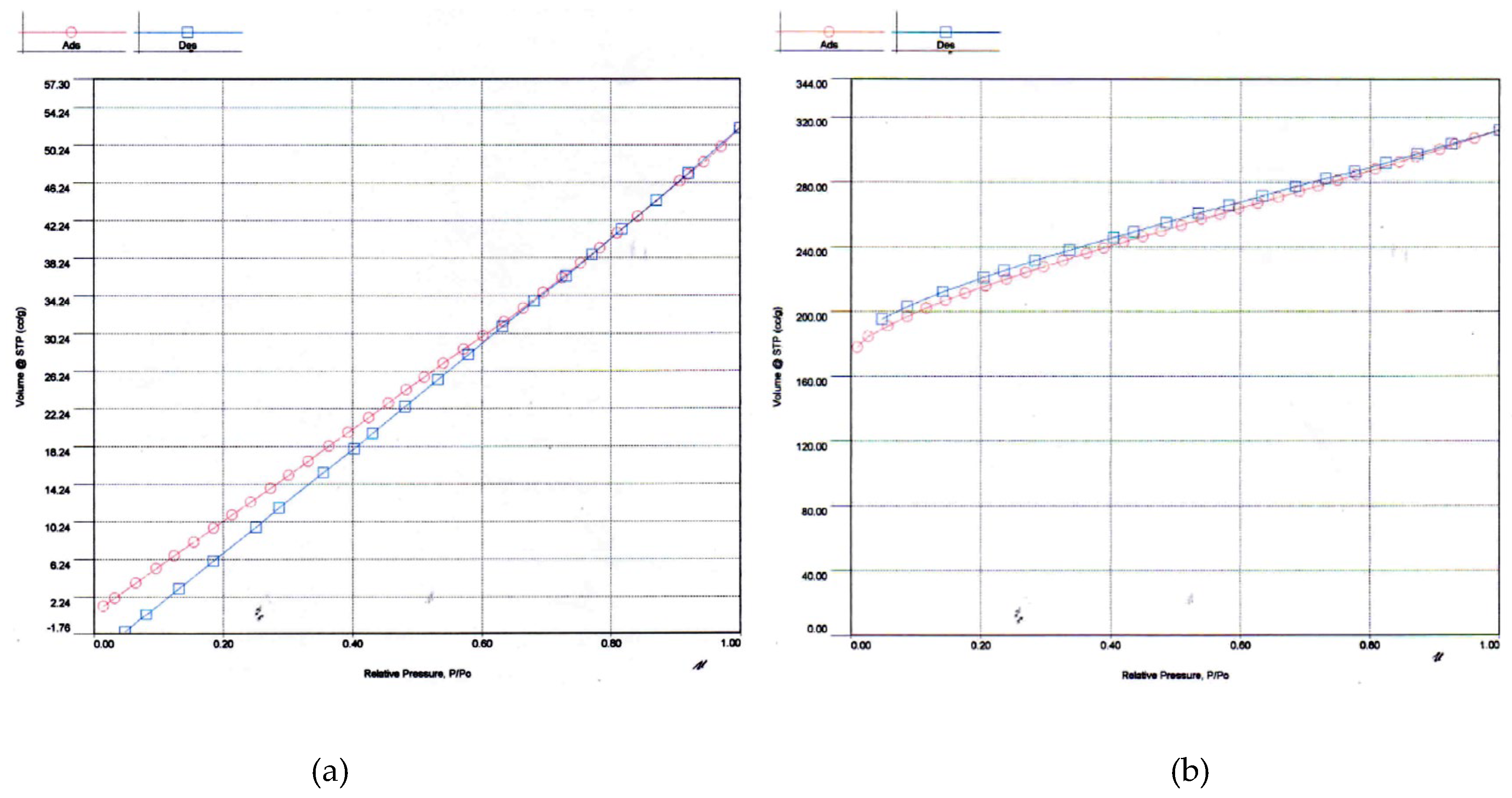

Isotherms of adsorption and desorption of N

2 were used to determine surface area, pore volume, and estimated pore diameter. Hydrothermal carbon revealed lower surface area, total pore volume, and higher pore diameter than activated carbon (

Table 3). Based on the classification of pores in solid materials, hydrothermal carbon has mesopores (2-50 nm) and activated carbon have supermicropores (0.7-2 nm) (Inagaki, 2009). The surface area of resultant activated carbon prepared by water vapor activation (690.451 m

2/g) was lower than activated carbon produced by combining hydrothermal carbonization and NaOH activation with a surface area of 1282.49 m

2/g. The total pore volume and surface area of hydrothermal carbon were lower due to during hydrothermal carbonization pore development do not occur enormously because of the recondensation of volatile substances. However, in the hydrothermal process, the major chemical components of lignocellulosic materials changed the cell wall structure and altered the surface properties (Islam et al., 2015).

The volume of micropores of activated carbon was higher than the range of micropores volume for activated carbon which ranged from 0.02-0.1 cc/g (Promdee et al., 2017). It can be assumed that activation using water vapor generated more micropores structure.

The formation of pores structure of hydrothermal and activated carbon can be observed from the isothermal adsorption/desorption curves of nitrogen.

Figure 4 revealed a slower adsorption/desorption rate which indicates the least active sites formed on hydrothermal carbon during the hydrothermal carbonization process (Liu et al., 2022).

Figure 5 exhibits type I/IV characteristics, with strong N

2 adsorption at a low relative pressure (P/P

0) and slightly steep N

2 adsorption at high relative P/P

0 indicating that micropores and mesopores/macropores coexist in activated carbon (Yuan et al., 2016).

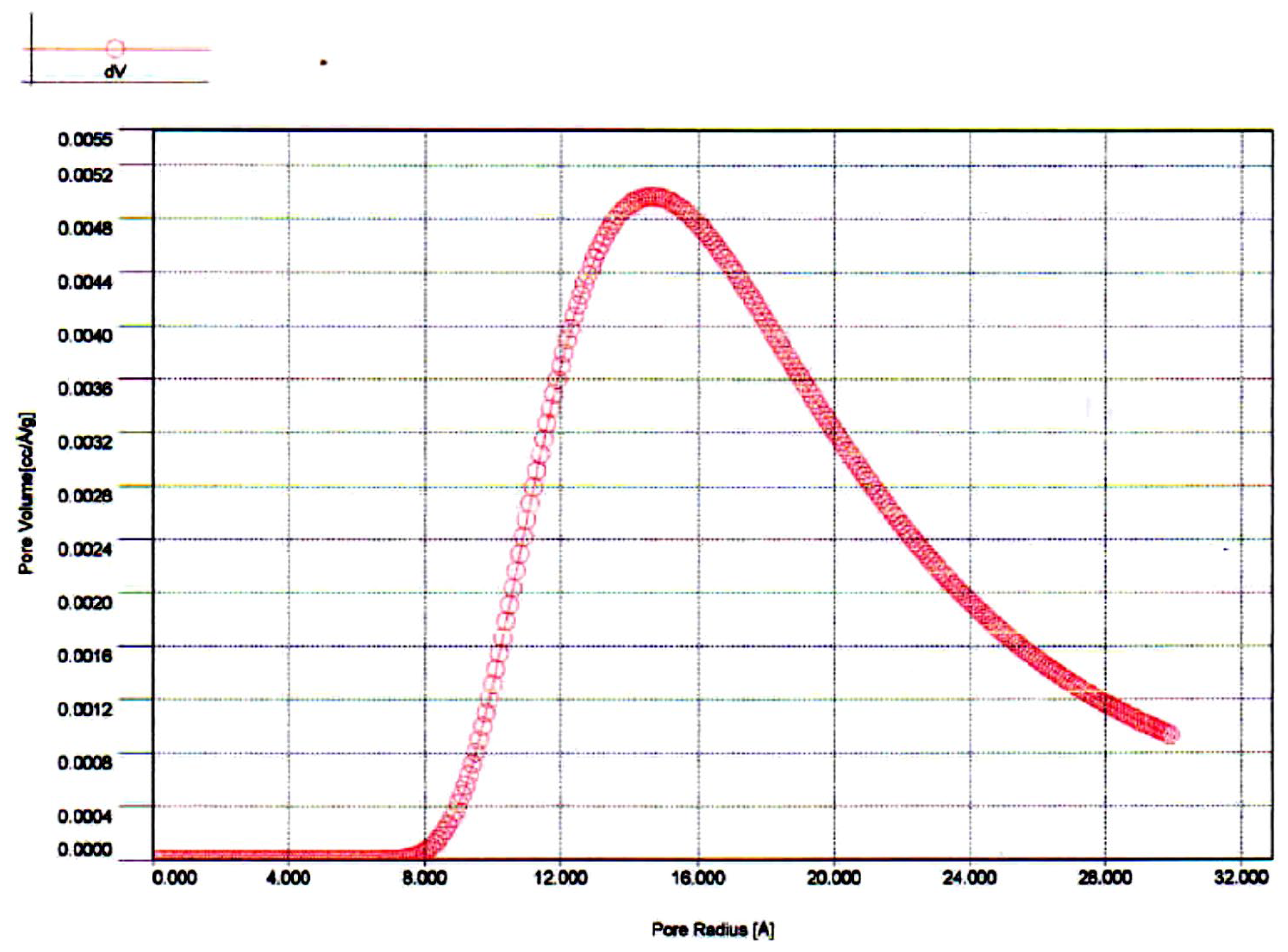

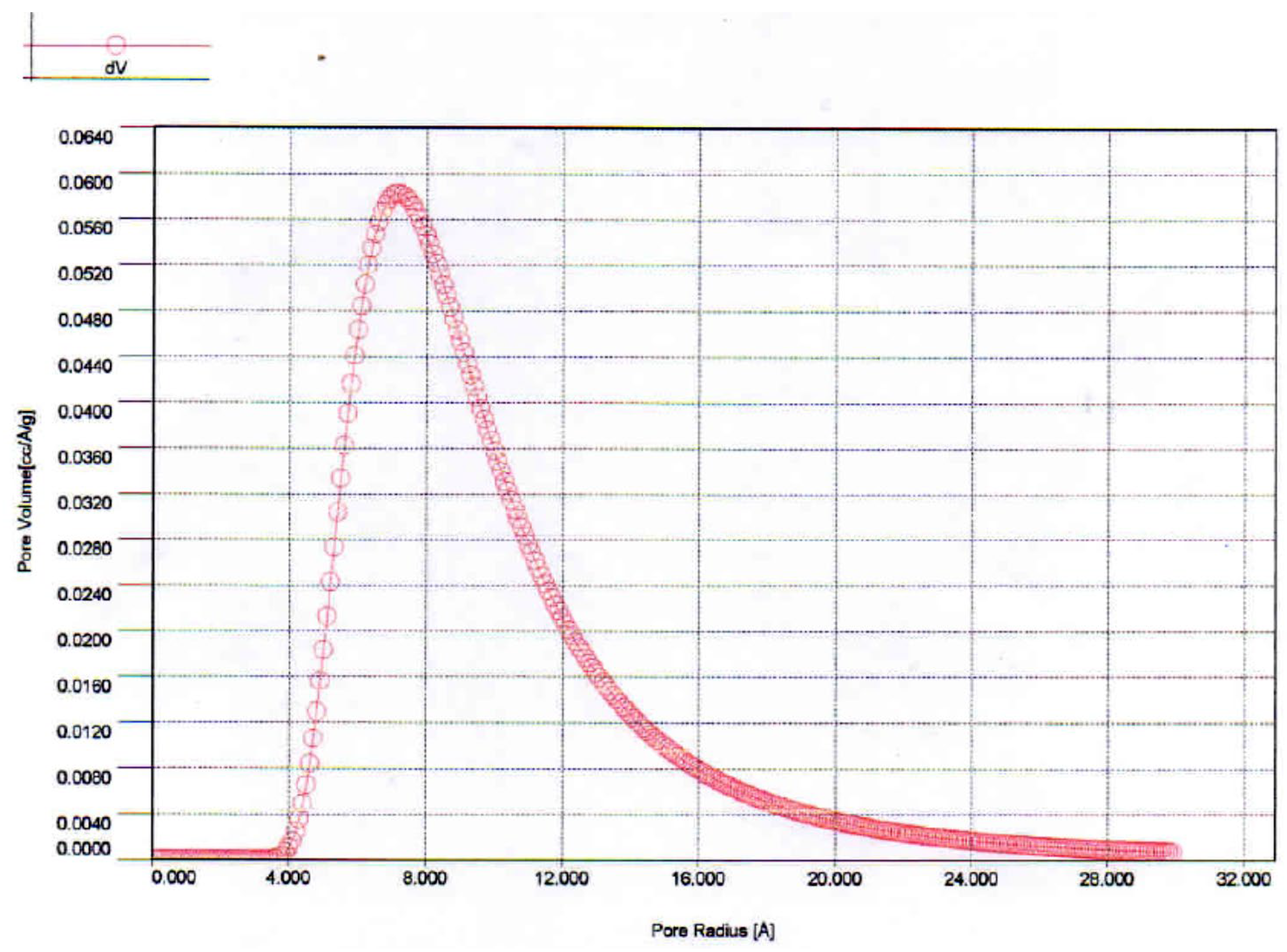

The pore distribution curves of Dubinin Astakov showed that activated carbon has a smaller pore size that dominates its surface when compared with hydrothermal carbon (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6). Based on the classification of pores in solid materials, hydrothermal carbon was predominantly mesoporous (2-50 nm) and activated carbon have supermicropores (0.7-2 nm) and ultra-micropores (< 0.7 nm) (Inagaki, 2009). Pore size distribution has been used to describe the internal structures and adsorption capacities of activated carbon. The large number of micropores on activated carbon can be attributed to the development of mesopores from hydrothermal carbon which formed during the activation process.

In-Vivo Antidiabetic Activity

Mocaf activated carbon (MAC) were combined with

Raru extract and then applied in reducing blood glucose level (antidiabetic) in experimental rats. The results indicate that the given treatments gave a good response in lowering the blood glucose of experimental rats (

Table 4.). Furthermore, the effects of raru extraxt and MAC on rats body weights are presented in

Table 5. The highest lowering value was found in pure

raru extract, followed by 75:25 raru extract+MAC and 50:50 raru extract+MAC. There was no significant effect of the presence of activated carbon in lowering blood glucose levels (

Table 4).

The tendency of lower effectiveness with larger doses of activated carbon was thought to be due to the incorporation of raru extract on activated carbon. In this study, raru extract was projected to be incorporated into activated charcoal pores, which is part of the passive delivery strategy, where extracts/ active compound is physically incorporated into the internal cavity and stabilized by noncovalent interactions between extracts and nanocarriers (Lu et al., 2016). The non-covalent bond that exists was very weak between the activated carbon and the raru extract which affects the delivery process and the effectiveness of the extract in the targeted cells (Lu et al., 2016; Patra et al., 2018).

Furthermore, Mirilaya and co-authors mentioned that drug compounds loaded on activated carbon had faster release which is influenced by the wettability of activated carbon and the melting process that occurred when the drug compounds interact with the surface of activated carbon which weakens the intermolecular bond between the drug compounds and activated carbon (Miriyala et al., 2017). In short, it can be said that the loading of the active compound with the physical incorporation is weaker than the chemical conjugation.

The results of this study strengthen the previous research that Vatica perakensis extract with in-vitro method can inhibit alpha glucosidase enzyme up to 92.57%. (Pasaribu, 2011)

However, this result is different from the results of Anisah’s study, which showed a trend of decreasing blood glucose from jabon leaf extract, samama peel extract, and mixing with hydro-activated carbon. The percentage decrease in glucose levels in rats treated with jabon extracts, jabon extract + hydro-activated carbon was 26.61% and 30.85%, respectively. It can be seen that there is an effect of antihyperglycemic activity with the addition of hydro-activated carbon. The same thing was seen in the samama bark extract and the samama bark extract + hydro activated carbon, which were 25.82% and 31.60%, respectively(Anisah et al., 2018).

Another study showed that the antihyperglycemic bioactivity of Melia azaderach ethanol extract and Tanacetum nubigenum ethanol extract induced by diabetic rats at dosage of 250 mg/kg were 14.8% and 15.5%, respectively (Khan et al., 2018).

Conclusion

The percentage of raru’s extract and MAC in lowering blood glucose levels (18%) was not different even slightly lower than raru’s extract treatment (21%). The mixture of raru’s extract and MAC with a 75:25 ratio is better than the 50:50 ratio. The porous structure of activated carbon has been suggested to be used as a potential drug carrier. However, it is necessary to pay attention to the physical characteristics of activated carbon which greatly affect its performance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ambalavanan R., John AD, Selvaraj AD. Nano-encapsulated Tinospora cordifolia (Willd.) using poly (D, L-lactide) nanoparticles educe effective control in streptozotocin- induced type 2 diabetic rats. IET Nanobiotechnology, 2020; 14(9), 803–808. [CrossRef]

- Anisah LN, Syafii W, Pari G, Sari RK. Antidiabetic activities and identification of chemical compound from samama (Anthocephalus macrophyllus (Roxb) Havil). Indonesian Journal of Chemistry, 2018; 18(1), 66–74. [CrossRef]

- Aravind M, Amalanathan M. Structural, morphological, and optical properties of country egg shell derived activated carbon for dye removal, Materials Today, 2021; 43, 1491–1495. [CrossRef]

- Avila MI, Alonso-Moralesn N, Gilarranz MA, Baeza A, Rodrıguez JJ, Gillaranz M. High load drug release system based on carbon porous nanocapsule carriers. Ibuprofen case study; Journal of Materials Chemistry B, 2020; 8, 5293–5304. [CrossRef]

- Çeçen, F. Activated Carbon. In Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology (Issue 1). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 2014; [CrossRef]

- El-bagory I, Alruwaili NK, Elkomy MH, Ahmad J, Afzal M, Ahmad N, Elmowafy M, Saad K, Alam S. Development of novel dapagliflozin loaded solid self-nanoemulsifying oral delivery system : Physiochemical characterization and in vivo antidiabetic activity. Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology, 2019:54. [CrossRef]

- Emin M, Ertas B, Alenezi H, Hazar-yavuz AN, Cesur S, Sinemcan G, Ekentok C, Guler E, Katsakouli C, Demirbas Z, Akakin D, Sayip M, Kabasakal L, Gunduz O. Accelerated diabetic wound healing by topical application of combination oral antidiabetic agents-loaded nanofibrous scaffolds : An in vitro and in vivo evaluation study. Materials Science & Engineering C, 2021; 119. [CrossRef]

- Falco C, Morallo E, Titirici MM. Tailoring the porosity of chemically activated hydrothermal carbons : Influence of the precursor and hydrothermal carbonization temperature. Carbon, 2013; 2. [CrossRef]

- Falco, Camillo, Caballero FP, Babonneau F, Gervais C, Laurent G, Titirici M, Baccile N. Hydrothermal Carbon from Biomass : Structural Differences between Hydrothermal and Pyrolyzed Carbons via 13 C Solid State NMR. Langmuir, 2011; 14460–14471. [CrossRef]

- Firdausya H, Amalia R. Review Jurnal: Aktivitas dan Efektivitas Antidiabetes pada Beberapa Tanaman Herbal. Farmaka, 2020; 18(1), 162–170.

- Hagiwara A, Takahashi T, Kitamura K, Sakakura C, Shirasu M, Ohgaki M, Imanishi T, Yamasaki J. Endoscopic local injection of a new drug delivery formulation, anticancer drug bound to carbon particles, for digestive cancers : Pilot study. Journal of Gastroenterology. 1997; 32: 141–147. [CrossRef]

- Holmes C, Godfrey M, John D, Dulieu-barton J. Real-time through-thickness and in-plane strain measurement in carbon fibre reinforced polymer composites using planar optical Bragg gratings. Optics and Lasers in Engineering, 2021, 133, 106111. [CrossRef]

- Inagaki M. Pores in carbon materials-importance of their control. New Carbon Materials, 2009; 24(3), 193–232. [CrossRef]

- International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas 2019 (9th Edition). 2019.

- Iqbal Y, Malik AR, Iqbal T, Aziz MH, Ahmed F, Abolaban FA, Ali SM, Ullah H. Green synthesis of ZnO and Ag-doped ZnO nanoparticles using Azadirachta indica leaves: characterization and their potential antibacterial, antidiabetic, and wound-healing activities. Materials Letters, 2021; [CrossRef]

- Islam A, Tan IAW, Benhouria A, Asif M, Hameed BH. Mesoporous and adsorptive properties of palm date seed activated carbon prepared via sequential hydrothermal carbonization and sodium hydroxide activation. Chemical Engineering Journal, 2015; 270, 187–195. [CrossRef]

- Khan MF, Rawat AK, Khatoon S, Kamil M, Mishra A, Singh D. In vitro and in vivo antidiabetic effect of extracts of Melia azedarach, Zanthoxylum alatum, and Tanacetum nubigenum. Integrative Medicine Research, 2018; 7(2), 176–183. [CrossRef]

- Li R, Tang N, Jia X, Xu Y, Cheng Y. Antidiabetic activity of galactomannan from Chinese Sesbania cannabina and its correlation of regulating intestinal microbiota. Journal of Functional Foods. 2021; 83, 104530. [CrossRef]

- Liu R, Xie Y, Cui K, Xie J, Zhang Y, Huang Y. Adsorption behavior and adsorption mechanism of glyphosate in water by amino-MIL-101 (Fe). Journal of Physical and Chemistry of Solids, 2022; 161, 110403. [CrossRef]

- Lu H, Wang J, Wang T, Zhong J, Bao Y, Hao H. Recent Progress on Nanostructures for Drug Delivery Applications. Journal of Nanomaterials, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Miriyala N, Ouyang D, Perrie Y, Lowry D, Kirby DJ. Activated carbon as a carrier for amorphous drug delivery: Effect of drug characteristics and carrier wettability. European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics. 2017; 115, 197–205. [CrossRef]

- Pari G, Darmawan S, Prihandoko B. Porous Carbon Spheres from Hydrothermal Carbonization and KOH Activation on Cassava and Tapioca Flour Raw Material. Procedia Environmental Sciences, 2014; 20, 342–351. [CrossRef]

- Pasaribu G. Inhibition Activity of Alpha Glucosidase from Several Stem Bark of Raru. Journal of Forest Products Research, 2011; 29(1), 10–19.

- Pasaribu G, Setyawati T. Antioxidant and Toxicity Activity of Raru (Cotylelobium sp.) Stem Bark. Journal of Forest Products Research, 2011; 29(4), 322–330.

- Patra JK, Das G, Fraceto LF, Vangelie E, Campos R, Rodriguez P, Susana L, Torres A, Armando L, Torres D, Grillo R. Nano based drug delivery systems: recent developments and future prospects. Journal of Nanobiotechnology, 2018; 16(71), 1–33. [CrossRef]

- Pires E, García-bordej E. Parametric study of the hydrothermal carbonization of cellulose and effect of acidic conditions. 2017; 123. [CrossRef]

- Promdee K, Chanvidhwatanakit J, Satitkune S. Characterization of carbon materials and di ff erences from activated carbon particle (ACP ) and coal briquettes product (CBP ) derived from coconut shell via rotary kiln. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2017; 75:1175–1186. [CrossRef]

- Pusat Data dan Informasi Kementerian Kesehatan Republik Indonesia. Infodatin. Pusar Data dan Informasi Kementerian Kesehatan Republik Indonesia. 2020.

- Riris DI, Napitupulu MA. Antidiabetic Activity of Methoxy Bergenin Isolated form Ethanol Extract of Raru Stem Bark (Vatica pauciflora Blume) in Alloxan Induced Diabetic Wistar Rats. Asian Journal of Chemistry, 2017; 29(4), 870–874. [CrossRef]

- Tafesse TB, Hymete A, Mekonnen Y, Tadesse M. Antidiabetic activity and phytochemical screening of extracts of the leaves of Ajuga remota Benth on alloxan-induced diabetic mice. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2017; 17, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Tanemura K, Rohand T. Activated charcoal as an effective additive for alkaline and acidic hydrolysis of esters in water. Tetrahedron Letters, 2020; 61(44), 152467. [CrossRef]

- Wang X, Liu P, Tian Y. Ordered mesoporous carbons for ibuprofen drug loading and release behavior. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials, 2011; 142(1), 334–340. [CrossRef]

- Yadavalli T, Ames J, Agelidis A, Suryawanshi R, Jaishankar D. Drug-encapsulated carbon (DECON ): A novel platform for enhanced drug delivery. Science Advances, 2019; 5, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Yuan C, Lin H, Lu H, Xing E, Zhang Y, Xie B. Synthesis of hierarchically porous MnO 2 / rice husks derived carbon composite as high-performance electrode material for supercapacitors. Applied Energy, 2016; 178, 260–268. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Zhi Z, Li X, Gao J, Song Y. Carboxylated mesoporous carbon microparticles as new approach to improve the oral bioavailability of poorly water-soluble carvedilol. International Journal of Pharmaceutics, 2013; 454(1), 403–411. [CrossRef]

- Zhu Y, Zhao J, Luo L, Gao Y, Bao H, Li P. Research progress of indole compounds with potential antidiabetic activity. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, 2021; 223, 113665. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).