Submitted:

25 April 2024

Posted:

26 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

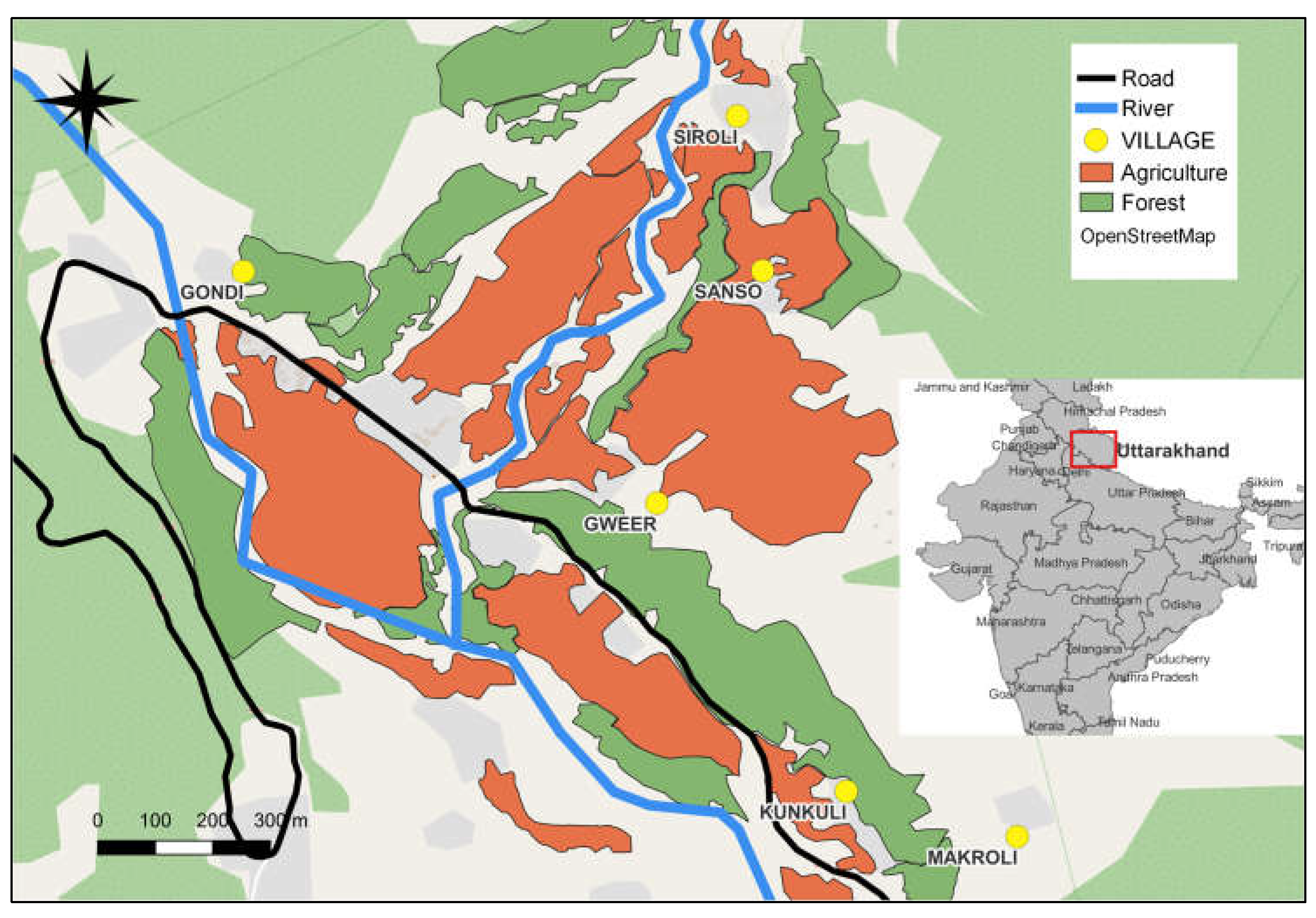

2.1. Study site and Population

2.2. Behavioral Data Collection

2.3. Behavioral Definitions

- Feeding: When an animal is ingesting or masticating food.

- Locomotion: An animal moves, at any pace, from one location to another, over a distance of more than 1 meter.

- Resting: An animal remains stationary, hindquarters on the supporting surface, either asleep (i.e., eyes closed) or awake (i.e., alert, with eyes open). It may simultaneously engage in l vigilance behavior.

- Social: Social interactions like grooming, play, or sexual activity.

2.4. Study Variables

2.5. Model Formulation and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

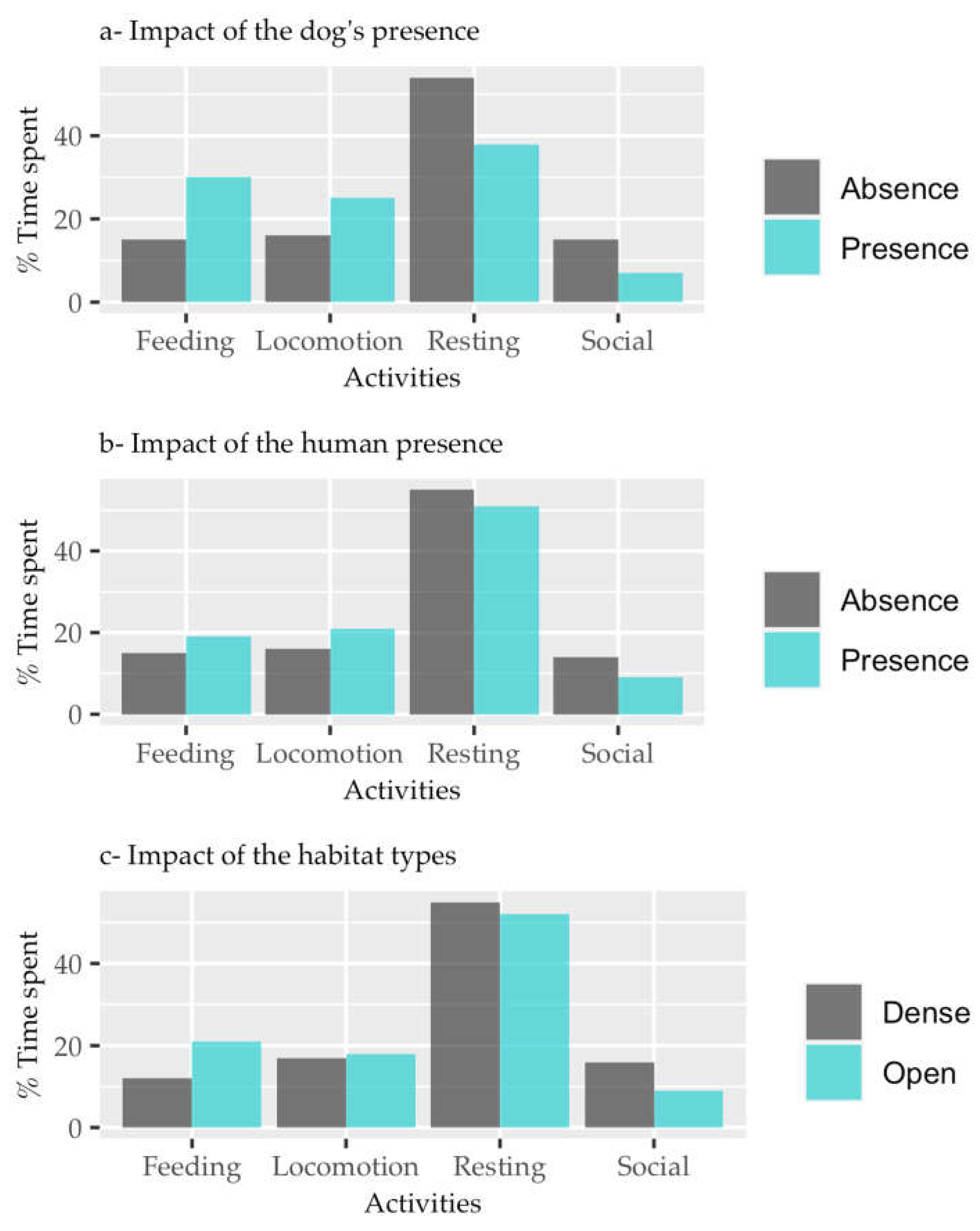

3.1. Selection of Activity Pattern

4. Discussion

4.1. Behavior Modifications in the Predator-Induced Landscape of Fear

4.2. Behavior Modifications in the Human-Induced Landscape of Fear

4.3. Behavior Modifications in the Habitats Associated with the Landscape of Fear

5. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vanak, A.T.; Gompper, M.E. Dogs Canis Familiaris as Carnivores: Their Role and Function in Intraguild Competition. Mammal Rev. 2009, 39, 265–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vila, C. Phylogenetic Relationships, Evolution, and Genetic Diversity of the Domestic Dog. J. Hered. 1999, 90, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gompper, M.E. Free-Ranging Dogs and Wildlife Conservation; 1st ed.; Oxford university press: Oxford (GB), 2014; ISBN 978-0-19-966321-7. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, J.; Macdonald, D.W. A Review of the Interactions between Free-Roaming Domestic Dogs and Wildlife. Biol. Conserv. 2013, 157, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driscoll, C.A.; Macdonald, D.W. Top Dogs: Wolf Domestication and Wealth. J. Biol. 2010, 9, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sepúlveda, M.A.; Singer, R.S.; Silva-Rodríguez, E.; Stowhas, P.; Pelican, K. Domestic Dogs in Rural Communities around Protected Areas: Conservation Problem or Conflict Solution? PLOS ONE 2014, 9, e86152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Home, C.; Bhatnagar, Y.V.; Vanak, A.T. Canine Conundrum: Domestic Dogs as an Invasive Species and Their Impacts on Wildlife in India. Anim. Conserv. 2018, 21, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldmann, B.M. The Problem of Urban Dogs. Science 1974, 185, 903–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritchie, E.G.; Dickman, C.R.; Letnic, M.; Vanak, A.T. Dogs as Predators and Trophic Regulators. In Free-Ranging Dogs and Wildlife Conservation; Gompper, M.E., Ed.; Oxford University Press, 2013; pp. 55–68 ISBN 978-0-19-966321-7.

- Banks, P.B.; Bryant, J.V. Four-Legged Friend or Foe? Dog Walking Displaces Native Birds from Natural Areas. Biol. Lett. 2007, 3, 611–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, T.S.; Dickman, C.R.; Glen, A.S.; Newsome, T.M.; Nimmo, D.G.; Ritchie, E.G.; Vanak, A.T.; Wirsing, A.J. The Global Impacts of Domestic Dogs on Threatened Vertebrates. Biol. Conserv. 2017, 210, 56–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, J.K.; Olson, K.A.; Reading, R.P.; Amgalanbaatar, S.; Berger, J. Is Wildlife Going to the Dogs? Impacts of Feral and Free-Roaming Dogs on Wildlife Populations. BioScience 2011, 61, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gompper, M.E. Adding Nuance to Our Understanding of Dog–Wildlife Interactions and the Need for Management. Integr. Comp. Biol. 2021, 61, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández, D.; Kerhoas, D.; Dempsey, A.; Billany, J.; McCabe, G.; Argirova, E. The Current Status of the World’s Primates: Mapping Threats to Understand Priorities for Primate Conservation. Int. J. Primatol. 2022, 43, 15–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estrada, A.; Garber, P.A.; Chaudhary, A. Current and Future Trends in Socio-Economic, Demographic and Governance Factors Affecting Global Primate Conservation. PeerJ 2020, 8, e9816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estrada, A.; Garber, P.A.; Rylands, A.B.; Roos, C.; Fernandez-Duque, E.; Di Fiore, A.; Nekaris, K.A.-I.; Nijman, V.; Heymann, E.W.; Lambert, J.E.; et al. Impending Extinction Crisis of the World’s Primates: Why Primates Matter. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1600946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waters, S.; Watson, T.; Farris, Z.J.; Bornbusch, S.; Valenta, K.; Clarke, T.A.; Chetry, D.; Randriana, Z.; Owen, J.R.; El Harrad, A.; et al. Dogs, Primates, and People: A Review. In Primates in Anthropogenic Landscapes; McKinney, T., Waters, S., Rodrigues, M.A., Eds.; Developments in Primatology: Progress and Prospects; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2023; ISBN 978-3-031-11735-0. [Google Scholar]

- Nautiyal, H.; Tanaka, H.; Huffman, M.A. Anti-Predator Strategies of Adult Male Central Himalayan Langurs (Semnopithecus schistaceus) in Response to Domestic Dogs in a Human-Dominated Landscape. Primates 2023, 64, 361–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pihlström, H.; Rosti, H.; Lombo, B.M.; Pellikka, P. Domestic Dog Predation on White-Tailed Small-Eared Galago (Otolemur garnettii lasiotis) in the Taita Hills, Kenya.

- Moresco, A.; Larsen, R.S.; Sauther, M.L.; Cuozzo, F.P.; Jacky, A.Y.; Millette, J.B. Survival of a Wild Ring-Tailed Lemur (Lemur catta) with Abdominal Trauma in an Anthropogenically Disturbed Habitat. Madag. Conserv. Dev. 2012, 7, 49–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, J. Herding Monkeys to Paradise: How Macaque Troops Are Managed for Tourism in Japan. In Herding Monkeys to Paradise; Brill, 2011.

- Najmuddin, M.F.; Haris, H.; Norazlimi, N.; Md-Zain, M.; Mohd-Ridwan, A.R.; Shahrool-Anuar, R.; Husna, H.A.; Abdul-Latiff, M.A.B. Predation of Domestic Dogs (Canis lupus familiaris) on Schlegel’s Banded Langur (Presbytis neglectus) and Crested Hawk-Eagle (Nisaetus cirrhatus) on Dusky Leaf Monkey (Trachypithecus obscurus) In Malaysia. J. S.S.M. 2019, 6, 39–50. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, N.; Hrdy, S.B.; Teas, J.; Moore, J. Measures of Human Influence in Habitats of South Asian Monkeys. Int. J. Primatol. 1981, 2, 153–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, B.; Pithva, K.; Mohanty, S.; McCowan, B. Lethal Dog Attacks on Adult Rhesus Macaques (Macaca Mulatta) in an Anthropogenic Landscape. Primates 2024, 65, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isbell, L.A. Predation on Primates: Ecological Patterns and Evolutionary Consequences. Evol. Anthropol. Issues News Rev. 1994, 3, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, D. Predation on Primates: A Biogeographical Analysis. In Primate Anti-Predator Strategies; Gursky, S.L., Nekaris, K.A.I., Eds.; Springer US: Boston, MA, 2007; ISBN 978-0-387-34810-0. [Google Scholar]

- Campos, F.A.; Fedigan, L.M. Spatial Ecology of Perceived Predation Risk and Vigilance Behavior in White-Faced Capuchins. Behav. Ecol. 2014, 25, 477–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willems, E.P.; Hill, R.A. Predator-Specific Landscapes of Fear and Resource Distribution: Effects on Spatial Range Use. Ecology 2009, 90, 546–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cowlishaw, G. Trade-Offs between Foraging and Predation Risk Determine Habitat Use in a Desert Baboon Population. Anim. Behav. 1997, 53, 667–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isbell, L.A. Predation on Primates: Ecological Patterns and Evolutionary Consequences. Evol. Anthropol. Issues News Rev. 1994, 3, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, B.A.; Hutto, R.L. A Framework for Understanding Ecological Traps and an Evaluation of Existing Evidence. Ecology 2006, 87, 1075–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, B.B.M.; Candolin, U. Behavioral Responses to Changing Environments. Behav. Ecol. 2015, 26, 665–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sih, A.; Ferrari, M.C.O.; Harris, D.J. Evolution and Behavioural Responses to Human-Induced Rapid Environmental Change. Evol. Appl. 2011, 4, 367–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuomainen, U.; Candolin, U. Behavioural Responses to Human-Induced Environmental Change. Biol. Rev. 2011, 86, 640–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryson-Morrison, N.; Tzanopoulos, J.; Matsuzawa, T.; Humle, T. Activity and Habitat Use of Chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes verus) in the Anthropogenic Landscape of Bossou, Guinea, West Africa. Int. J. Primatol. 2017, 38, 282–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negrín, A.R.; Fuentes, A.C.; Espinosa, D.C.; Dias, P.A.D. The Loss of Behavioral Diversity as a Consequence of Anthropogenic Habitat Disturbance: The Social Interactions of Black Howler Monkeys. Primates 2016, 57, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinney, T. A Classification System for Describing Anthropogenic Influence on Nonhuman Primate Populations. Am. J. Primatol. 2015, 77, 715–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sih, A. Understanding Variation in Behavioural Responses to Human-Induced Rapid Environmental Change: A Conceptual Overview. Anim. Behav. 2013, 85, 1077–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrlich, P.R. Intervening in Evolution: Ethics and Actions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2001, 98, 5477–5480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nautiyal, H. Behavioral Ecology of the Central Himalayan Langur (Semnopithecus schistaceus) in a Human Dominated Landscape: Multi-Species Interactions and Conservation Implications, Kyoto University, 2020.

- Nautiyal, H.; Mathur, V.; Sinha, A.; Huffman, M.A. The Banj Oak Quercus leucotrichophora as a Potential Mitigating Factor for Human-Langur Interactions in the Garhwal Himalayas, India: People’s Perceptions and Ecological Importance. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2020, 22, e00985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajare, K.H. Interaction between Feral Dogs and Central Himalayan Langur (Semnopithecus schistaceus ), Mumbai university, 2023.

- Mathur, V.; Teichroeb, J.; Nautiyal, H. Understanding Variability In Crop Foraging By Himalayan Langurs (Semnopithecus schistacesus) And Other Wildlife Species Using Direct Observation And Camera Traps In An Anthropogenic Landscape. In American Socity Of Primatology Conference, Reno, USA, 21/06/2023.

- Theuerkauf, J.; Rouys, S. Habitat Selection by Ungulates in Relation to Predation Risk by Wolves and Humans in the Białowieża Forest, Poland. For. Ecol. Manag. 2008, 256, 1325–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, K.; Wimberger, K.; Richards, S.A.; Hill, R.A.; le Roux, A. Samango Monkeys (Cercopithecus albogularis labiatus) Manage Risk in a Highly Seasonal, Human-Modified Landscape in Amathole Mountains, South Africa. Int. J. Primatol. 2017, 38, 194–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Candolin, U.; Wong, B.B.M. Behavioural Responses to a Changing World: Mechanisms and Consequences; Oxford University Press, 2012; ISBN 978-0-19-960256-8.

- Lenth, B.; Knight, R.; Brennan, M. The Effects of Dogs on Wildlife Communities. Nat. Areas J. 2008, 28, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nautiyal, H. Life in the Extreme: Time-Activity Budgets and Foraging Ecology of Central Himalayan Langur (Semnopithecus schistaceus) in the Kedarnath Wildlife Sanctuary, Uttarakhand India, Bharathidasan University, 2015.

- Mathur, V. Choice and Characteristics of Sleeping Sites in a Troop of Central Himalayan Langurs (Semnopithecus schistaceus), Indian Institute of Science Education and Research Mohali, 2019.

- Altmann, J. Observational Study of Behavior: Sampling Methods. Behaviour 1974, 49, 227–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolhinow, P. A Behavior Repertoire for the Indian Langur Monkey (Presbytis entellus). Primates 1978, 19, 449–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- William Venables; Brian Ripley Modern Applied Statistics with S; New York.

- Ripley, B.; Venables, W. Nnet: Feed-Forward Neural Networks and Multinomial Log-Linear Models 2023.

- R A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. 2022.

- Long, J.S.; Freese, J. Regression Models for Categorical Dependent Variables Using Stata, Second Edition; Stata Press, 2006; ISBN 978-1-59718-011-5.

- Davies, G.; Oates, J. Colobine Monkeys: Their Ecology, Behaviour and Evolution; Cambridge University Press, 1994; ISBN 978-0-521-33153-1.

- Agresti, A. Categorical Data Analysis; John Wiley & Sons, 2012; ISBN 978-0-470-46363-5.

- Anderson, C.J.; Rutkowski, L. Multinomial Logistic Regression. In Best Practices in Quantitative Methods; Osborne, J., Ed.; SAGE Publishing, 2008; pp. 390–409 ISBN 978-1-4129-4065-8.

- Advanced Issues and Deeper Insights. Model Selection and Multimodel Inference: A Practical Information-Theoretic Approach; Burnham, K.P., Anderson, D.R., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, 2002; pp. 267–351. ISBN 978-0-387-22456-5. [Google Scholar]

- Burnham, K.P.; Anderson, D.R.; Huyvaert, K.P. AIC Model Selection and Multimodel Inference in Behavioral Ecology: Some Background, Observations, and Comparisons. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2011, 65, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symonds, M.R.E.; Moussalli, A. A Brief Guide to Model Selection, Multimodel Inference and Model Averaging in Behavioural Ecology Using Akaike’s Information Criterion. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2011, 65, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, S.A.; Whittingham, M.J.; Stephens, P.A. Model Selection and Model Averaging in Behavioural Ecology: The Utility of the IT-AIC Framework. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2011, 65, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazerolle, M.J. AICcmodavg: Model Selection and Multimodel Inference Based on (Q)AIC(c) 2023.

- Rushton, S.P.; Ormerod, S.J.; Kerby, G. New Paradigms for Modelling Species Distributions? J. Appl. Ecol. 2004, 41, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittingham, M.J.; Stephens, P.A.; Bradbury, R.B.; Freckleton, R.P. Why Do We Still Use Stepwise Modelling in Ecology and Behaviour? J. Anim. Ecol. 2006, 75, 1182–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, J.B.; Omland, K.S. Model Selection in Ecology and Evolution. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2004, 19, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duboscq, J.; Romano, V.; Sueur, C.; MacIntosh, A.J.J. Scratch That Itch: Revisiting Links between Self-Directed Behaviour and Parasitological, Social and Environmental Factors in a Free-Ranging Primate. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2016, 3, 160571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mercier, S.; Neumann, C.; van de Waal, E.; Chollet, E.; Meric de Bellefon, J.; Zuberbühler, K. Vervet Monkeys Greet Adult Males during High-Risk Situations. Anim. Behav. 2017, 132, 229–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonsdorf, E.V.; Wilson, M.L.; Boehm, E.; Delaney-Soesman, J.; Grebey, T.; Murray, C.; Wellens, K.; Pusey, A.E. Why Chimpanzees Carry Dead Infants: An Empirical Assessment of Existing Hypotheses. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2020, 7, 200931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rangel-Negrín, A.; Coyohua-Fuentes, A.; Chavira, R.; Canales-Espinosa, D.; Dias, P.A.D. Primates Living Outside Protected Habitats Are More Stressed: The Case of Black Howler Monkeys in the Yucatán Peninsula. PLOS ONE 2014, 9, e112329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galbany, J.; Muhire, T.; Vecellio, V.; Mudakikwa, A.; Nyiramana, A.; Cranfield, M.R.; Stoinski, T.S.; McFarlin, S.C. Incisor Tooth Wear and Age Determination in Mountain Gorillas from Volcanoes National Park, Rwanda. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 2018, 167, 930–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, J.B.; Strier, K.B. Geographic, Climatic, and Phylogenetic Drivers of Variation in Colobine Activity Budgets. Primates 2022, 63, 647–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khater, M.; Murariu, D.; Gras, R. Predation Risk Tradeoffs in Prey: Effects on Energy and Behaviour. Theor. Ecol. 2016, 9, 251–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.S.; Laundré, J.W.; Gurung, M. The Ecology of Fear: Optimal Foraging, Game Theory, and Trophic Interactions. J. Mammal. 1999, 80, 385–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaynor, K.M.; Brown, J.S.; Middleton, A.D.; Power, M.E.; Brashares, J.S. Landscapes of Fear: Spatial Patterns of Risk Perception and Response. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2019, 34, 355–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotler, B.P.; Brown, J.S.; Hasson, O. Factors Affecting Gerbil Foraging Behavior and Rates of Owl Predation. Ecology 1991, 72, 2249–2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lind, J.; Cresswell, W. Determining the Fitness Consequences of Antipredation Behavior. Behav. Ecol. 2005, 16, 945–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trussell, G.C.; Matassa, C.M.; Luttbeg, B. The Effects of Variable Predation Risk on Foraging and Growth: Less Risk Is Not Necessarily Better. Ecology 2011, 92, 1799–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisenden, B.D. Female Convict Cichlids Adjust Gonadal Investment in Current Reproduction in Response to Relative Risk of Brood Predation. Can. J. Zool. 1993, 71, 252–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, C.M.; Gairola, S.; Ghildiyal, S.K.; Suyal, S. Forest Resource Use Patterns in Relation to Socioeconomic Status. Mt. Res. Dev. 2009, 29, 308–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makino, Y. Lopping of Oaks in Central Himalaya, India. Mt. Res. Dev. 2011, 31, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valeix, M.; Loveridge, A.J.; Chamaillé-Jammes, S.; Davidson, Z.; Murindagomo, F.; Fritz, H.; Macdonald, D.W. Behavioral Adjustments of African Herbivores to Predation Risk by Lions: Spatiotemporal Variations Influence Habitat Use. Ecology 2009, 90, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciuti, S.; Northrup, J.M.; Muhly, T.B.; Simi, S.; Musiani, M.; Pitt, J.A.; Boyce, M.S. Effects of Humans on Behaviour of Wildlife Exceed Those of Natural Predators in a Landscape of Fear. PLOS ONE 2012, 7, e50611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadesse, S.A.; Kotler, B.P. Impact of Tourism on Nubian Ibex (Capra nubiana) Revealed through Assessment of Behavioral Indicators. Behav. Ecol. 2012, 23, 1257–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahato, S.; Dasgupta, S.; Todaria, N.P.; Singh, V.P. Agroforestry Mapping and Characterization in Four Districts of Garhwal Himalaya. Energy Ecol. Environ. 2016, 1, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bersacola, E.; Hill, C.M.; Hockings, K.J. Chimpanzees Balance Resources and Risk in an Anthropogenic Landscape of Fear. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 4569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLennan, M.R.; Hill, C.M. Troublesome Neighbours: Changing Attitudes towards Chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) in a Human-Dominated Landscape in Uganda. J. Nat. Conserv. 2012, 20, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Yuan, P.; Huang, H.; Tang, X.; Xu, W.; Huang, C.; Zhou, Q. Effect of Habitat Fragmentation on Ranging Behavior of White-Headed Langurs in Limestone Forests in Southwest China. Primates 2017, 58, 423–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryson-Morrison, N.; Tzanopoulos, J.; Matsuzawa, T.; Humle, T. Activity and Habitat Use of Chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes verus) in the Anthropogenic Landscape of Bossou, Guinea, West Africa. Int. J. Primatol. 2017, 38, 282–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thatcher, H.R.; Downs, C.T.; Koyama, N.F. Anthropogenic Influences on the Time Budgets of Urban Vervet Monkeys. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 181, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayapali, U.; Perera, P.; Cresswell, J.; Dayawansa, N. Does Anthropogenic Influence on Habitats Alter the Activity Budget and Home Range Size of Toque Macaques (Macaca sinica)? Insight into the Human-Macaque Conflict. Trees For. People 2023, 13, 100412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| MLR Models | K | AICc | ΔAICc | Weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PD+PH+H-OF+( 1 Year) | 12 | 154340.4 | 0 | 1 |

| PH+H-OF+( 1| Year) | 9 | 154564.4 | 223.96 | 0 |

| PD+H-OF+( 1| Year) | 9 | 154569.3 | 228.96 | 0 |

| H-OF+( 1| Year) | 6 | 154959.4 | 618.97 | 0 |

| PD+PH+( 1| Year) | 9 | 155579.5 | 1239.11 | 0 |

| PD+( 1| Year) | 6 | 155833.3 | 1492.9 | 0 |

| PH+( 1| Year) | 6 | 155888.1 | 1547.76 | 0 |

| MLR~1+( 1| Year) | 3 | 156371.4 | 2030.96 | 0 |

| Predictor variable | Presence of Dog | Presence of Human | Habitat- Open Forest | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feeding | z value | 0.601 | 11.255 | 25.641 |

| p value | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | |

| *Coef (SE) | 0.016 (0.027) | 0.288 (0.026) | 0.585 (0.023) | |

| Locomotion | z value | 6.135 | 8.122 | 4.717 |

| p value | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | |

| Coef (SE) | 0.156 (0.025) | 0.202 (0.025) | 0.106 (0.022) | |

| Social | z value | 11.963 | 5.407 | 17.872 |

| p value | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | |

| Coef (SE) | 0.386 (0.032) | 0.163 (0.030) | 0.492 (0.028) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).