Submitted:

26 April 2024

Posted:

28 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- RQ1:

- What are the primary biosignals provided by wearables that can be utilized for personalized stress detection?

- RQ2:

- What are the key artificial intelligence (AI) techniques used to develop personalized stress detection models?

- RQ3:

- Are there publicly available datasets for training personalized stress detection models?

- RQ4:

- What are the wearable devices available on the market that allow the acquisition of raw data?

- RQ5:

- What are the primary challenges encountered in the practical implementation of stress detection models in the real world?

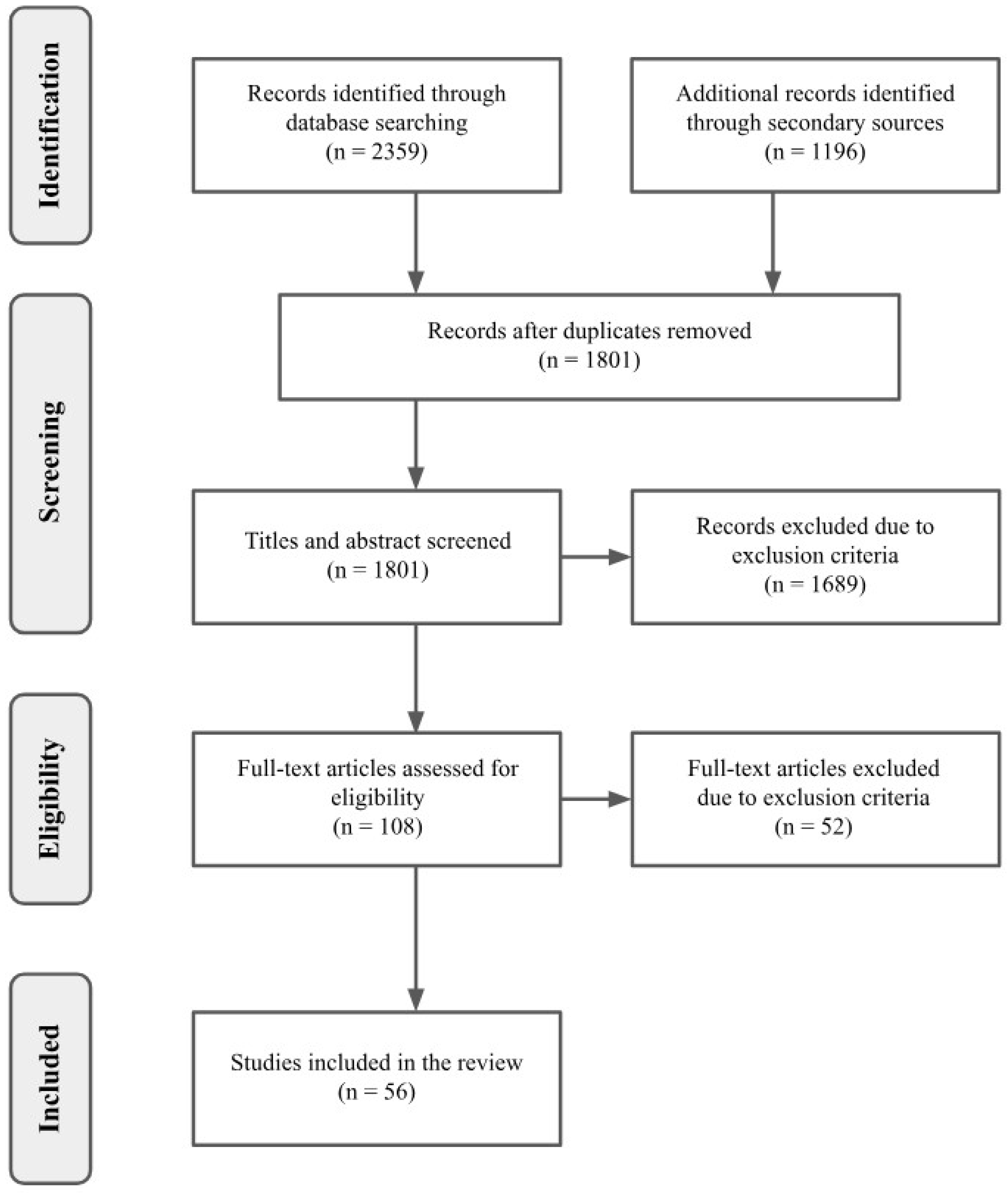

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Sources and Search Strategy

2.3. Selection of Studies

- The study was conducted from 2010 onwards 1.

- The study was conducted in laboratory settings or real-life contexts.

- The study was published in English.

- The study used mainly non-invasive 2 wearables or bands.

- The study focused on mental stress.

- The study involved creating models or datasets for personalized stress detection or investigating the challenges in real-world applications.

- The study was not a review article.

- The study did not use synthetic data produced by GANs or other generative systems.

- The study was not exclusively published as an abstract or poster at a conference.

| Research question | Queries |

|---|---|

| What are the primary biosignals provided by wearables that can be utilized for personalized stress detection? | (“personalized” OR “subject level” OR “individual”) AND (“stress”) AND (“detection” OR “prediction” OR “recognition” OR “classification”) AND (“wearable”) |

| What are the key artificial intelligence techniques used for developing models for personalized stress detection? | (“physiological”) AND (“stress”) AND (“detection” OR “prediction” OR “recognition” OR “classification”) AND (“wearable”) |

| Are there publicly available datasets for training personalized stress detection models? | ("personalized" OR "subject level" OR "individual") AND ("stress") AND ("detection" OR "prediction" OR "recognition" OR "classification") AND ("dataset") (“emotion” OR “stress”) AND (“detection” OR “recognition” OR “research” OR “classification” OR “prediction”) AND (“dataset” OR “database”) |

| What are the wearable devices available on the market that allow the acquisition of raw data? | Web search: {biosignal} AND “wearable device” |

| What are the primary challenges encountered in the practical implementation of stress detection models in the real-world? | ("wearables" OR "wearable devices") AND ("machine learning" OR "artificial intelligence" OR "monitoring") AND ("challenge" OR "challenges" OR "issues" OR "perspectives" OR "limitations" OR "topics") AND ("ethical" OR "ethics" OR "sensors") AND ("arousal" OR "distress" OR "stress" OR "physiological activity" OR "physiological reactions" OR "physiological response") ("wearables" OR "wearable devices" OR "smartwatch" OR "smartwatches") AND ("machine learning" OR "ml" OR "artificial intelligence" OR "ai" OR "monitoring" OR "prediction" OR "classification" OR "detection") AND ("challenge" OR "challenges" OR "issues" OR "perspectives" OR "limitations" OR "topics") AND ("ethical" OR "ethics" OR "sensors") AND ("arousal" OR "distress" OR "eustress" OR "stress" OR "physiological activity" OR "physiological reactions" OR "physiological response") |

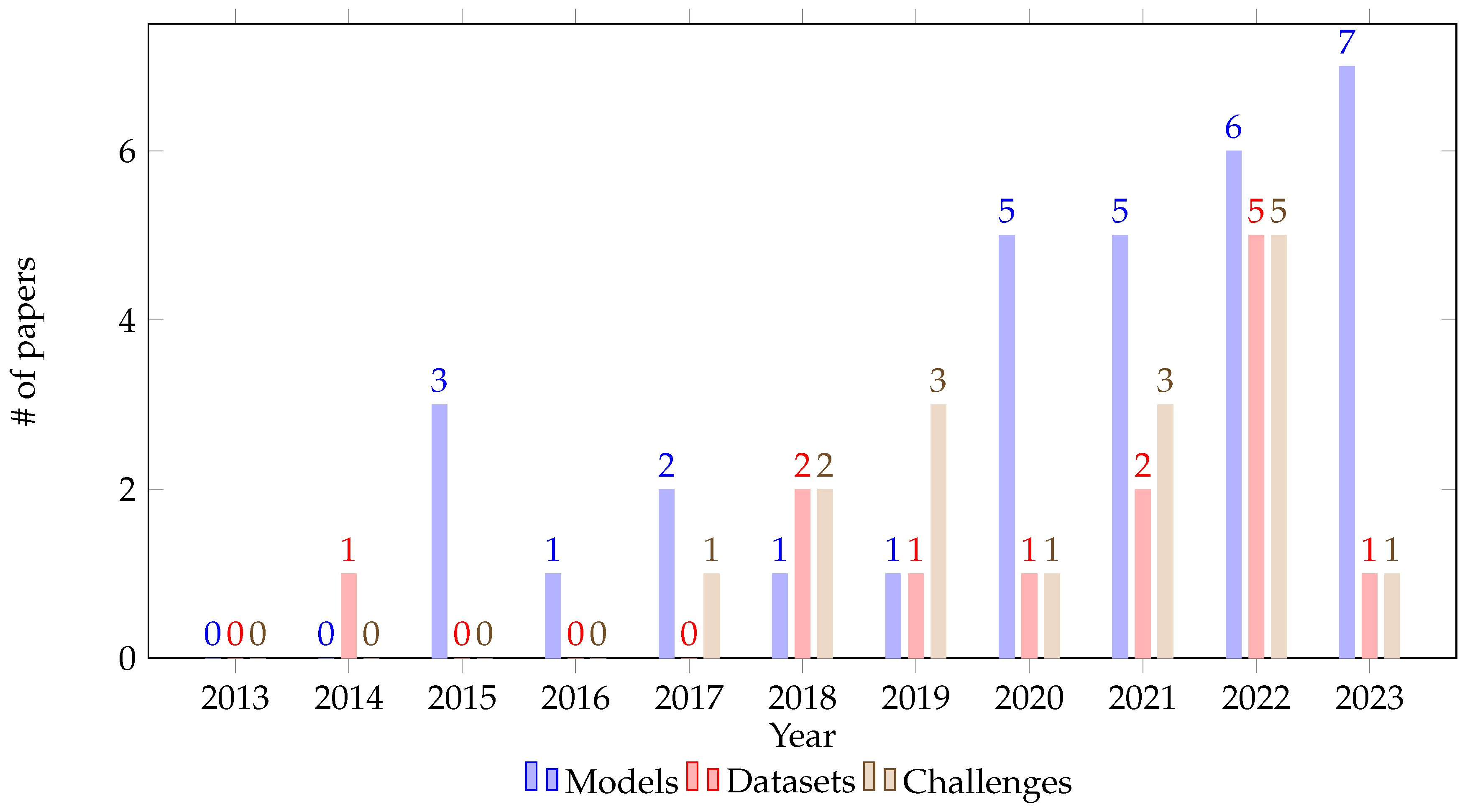

3. Results

3.1. Biosignals and Techniques for Personalized Stress Detection with Wearable Devices

3.1.1. Biosignals

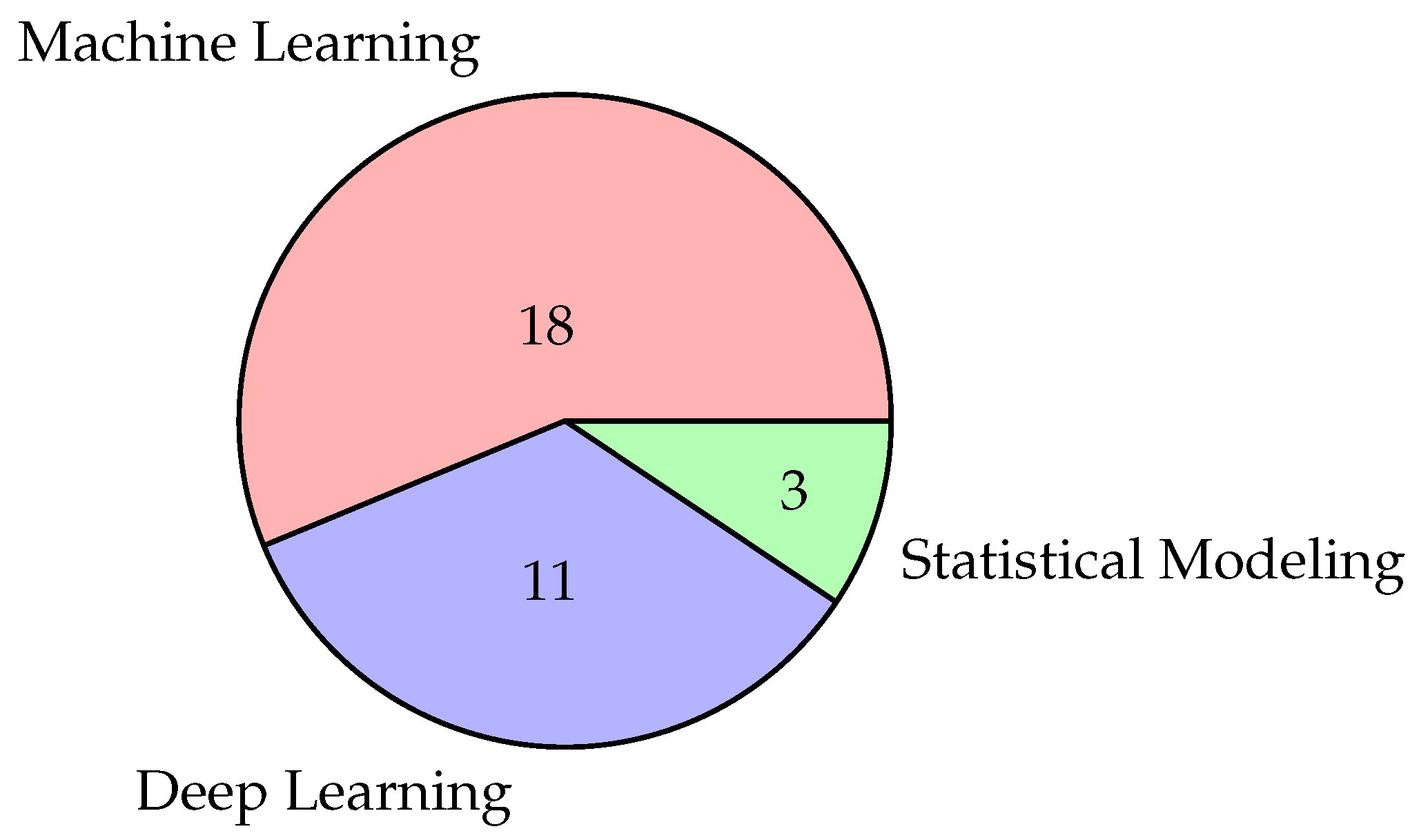

3.1.2. Techniques

- Machine Learning Approach

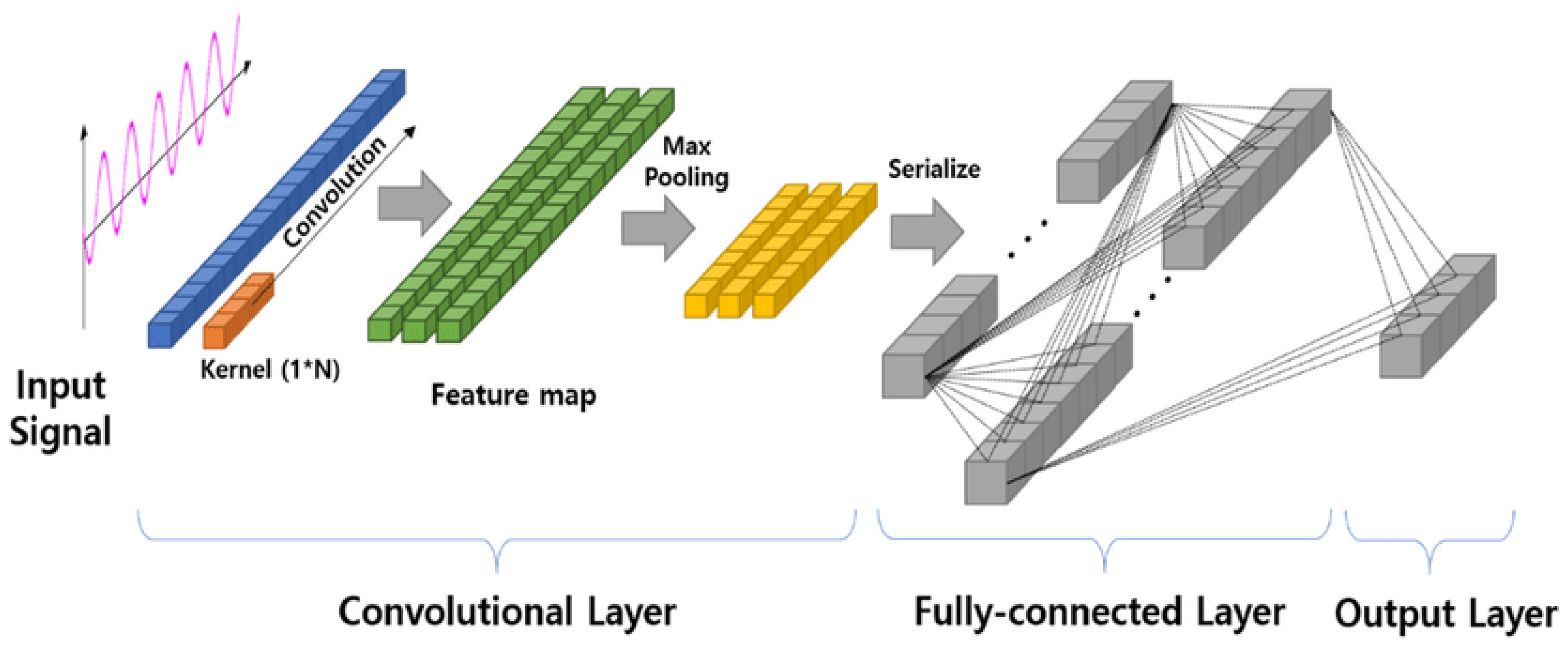

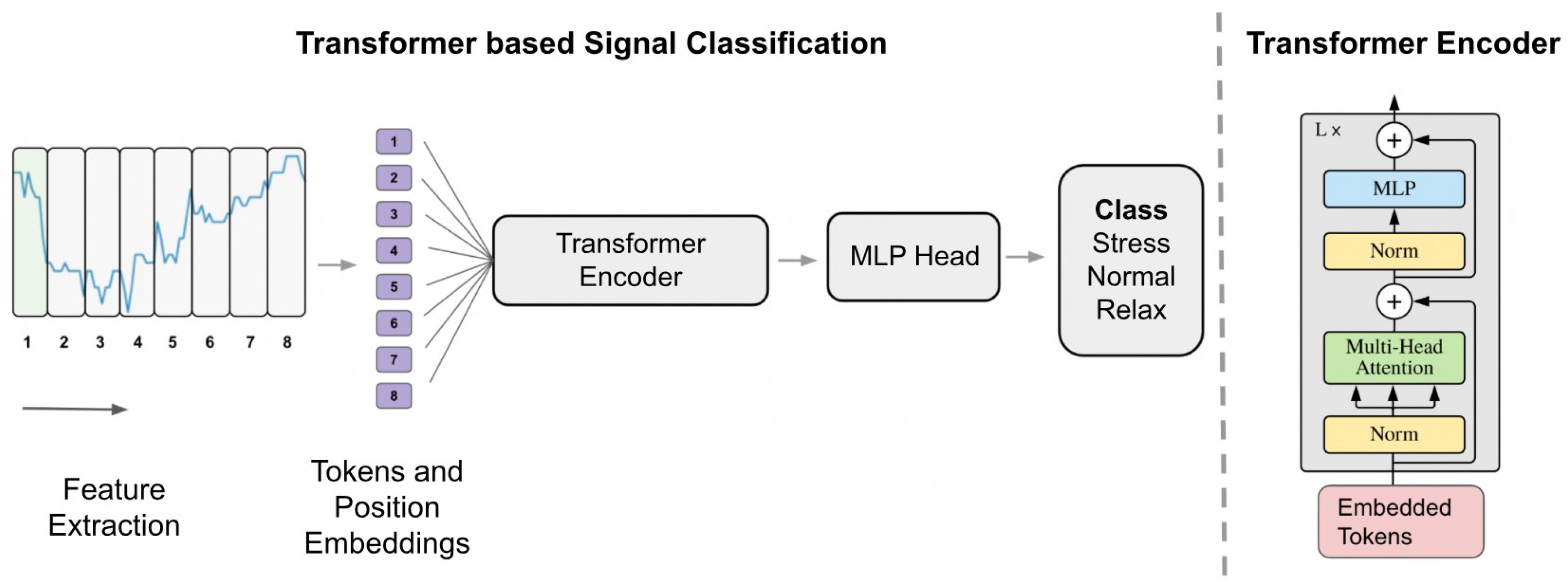

- Deep Learning Approach

- Statistical Approach

3.2. Datasets for Personalized Stress Detection

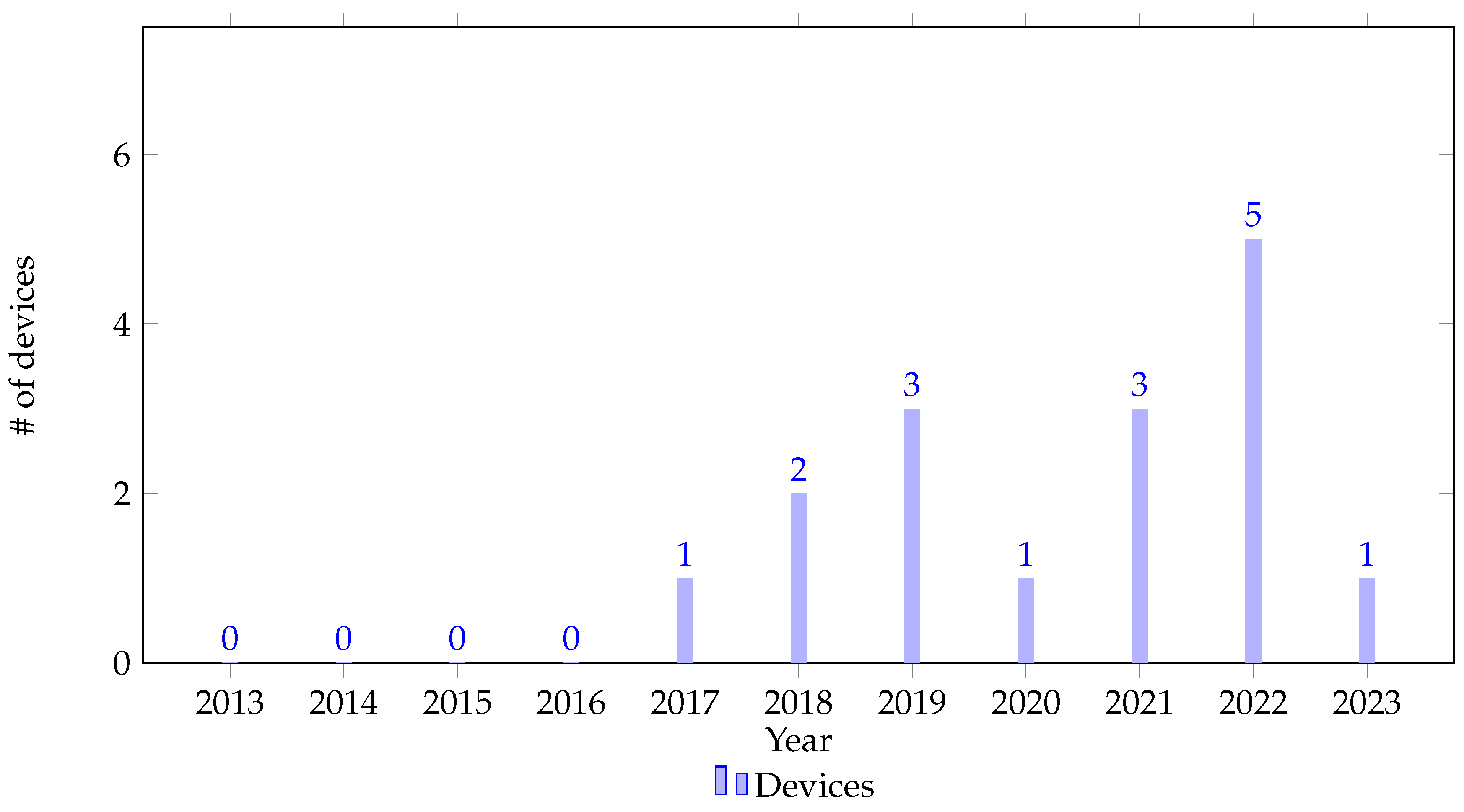

3.3. Devices for Raw Data Collection in Stress Detection Research

3.4. Real-World Challenges in Stress Detection Solutions.

| Theme | Study(s) |

|---|---|

| Data quality and signal distortion | [109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117] |

| Technical aspects related to wearable devices | [109,114,118] |

| User experience and behavior | [112,114,118,119] |

| Privacy | [118] |

| Interpretability | [116] |

3.4.1. Data Quality and Signal Distortion

3.4.2. Technical Aspects Related to Wearable Devices

3.4.3. User Experience and Behavior

3.4.4. Privacy

3.4.5. Interpretability

4. Discussion

4.1. Biosignals

4.2. AI Techniques

4.3. Datasets

4.4. Devices

4.5. Real-World Challenges

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| M | Male |

| F | Female |

| N/A | Not Available |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SCE | Controlled Scenario Environment |

| LAB | Laboratory |

| LIFE | Real-life |

| ECG | Electrocardiogram |

| EDA | Electrodermal Activity |

| RSP | Respiration |

| SKT | Peripheral Skin Temperature |

| ACC | Accelerometer |

| PPG | Photoplethysmography |

| EEG | Electroencephalogram |

| EMG | Electromyogram |

| SO2 | Peripheral Oxygen Saturation |

| MIC | Microphone |

| VS | Video Stream |

| FBT | Full Body Tracking |

| GYR | Gyroscope |

| IBI | Interbeat Interval |

| BIA | Bioelectric Impedance Analysis |

| NIBP | Non-Invasive Blood Pressure |

| EMAs | Ecological Momentary Assessment |

| STAI | State Trait Anxiety Inventory |

| PANAS | Positive and Negative Affect Schedule |

| SAM | Self-Assessment Manikin |

| SSQ | Short Stress State Questionnaire |

| PSS | Perceived Stress Scale |

| RSME | Rating Scale Mental Effort |

| ICI | Internal Control Index |

| CSAI | Competitive State Anxiety Inventory |

| NASA-TLX | NASA Task Load Index |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| GRNN | General Regression Neural Network |

| DAE | Denoising Auto Encoder |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| RBF | Radial Basis Function |

| AdaBoost | Adaptive Boosting |

| MLP | Multilayer Perceptron |

| RF | Random Forest |

| SOM | Self-Organizing Map |

| AUROC | Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| TCN | Temporal Convolutional Network |

| LR | Logistic Regression |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| SSL | Self-supervised learning |

| MFN | Modality Fusion Network |

| SAB | Self-attention Block |

References

- WHO. Stress. https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/stress. Accessed: 2023-10-24.

- APA. Stress. https://dictionary.apa.org/stress. Accessed: 2023-10-24.

- APA. Stress effects on the body. https://www.apa.org/topics/stress/body. Accessed: 2023-10-24.

- Sinha, R. Chronic stress, drug use, and vulnerability to addiction. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2008, 1141, 105–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marin, M.F.; Lord, C.; Andrews, J.; Juster, R.P.; Sindi, S.; Arsenault-Lapierre, G.; Fiocco, A.J.; Lupien, S.J. Chronic stress, cognitive functioning and mental health. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2011, 96, 583–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cannon, W.B. The wisdom of the body. Plan. Perspect. 1932, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, B.; Marwaha, K.; Sanvictores, T.; Ayers, D. Physiology, Stress Reaction; StatPearls Publishing, 2022.

- Godoy, L.D.; Rossignoli, M.T.; Delfino-Pereira, P.; Garcia-Cairasco, N.; de Lima Umeoka, E.H. A Comprehensive Overview on Stress Neurobiology: Basic Concepts and Clinical Implications. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Kamarck, T.; Mermelstein, R. A global measure of perceived stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1983, 24, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirschbaum, C.; Pirke, K.M.; Hellhammer, D.H. The ’Trier Social Stress Test’–a tool for investigating psychobiological stress responses in a laboratory setting. Neuropsychobiology 1993, 28, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosswell, A.D.; Lockwood, K.G. Best practices for stress measurement: How to measure psychological stress in health research. Health Psychol Open 2020, 7, 2055102920933072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epel, E.S.; Crosswell, A.D.; Mayer, S.E.; Prather, A.A.; Slavich, G.M.; Puterman, E.; Mendes, W.B. More than a feeling: A unified view of stress measurement for population science. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2018, 49, 146–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryk, A.S.; Raudenbush, S.W. Application of hierarchical linear models to assessing change. Psychol. Bull.

- Giannakakis, G.; Grigoriadis, D.; Giannakaki, K.; Simantiraki, O.; Roniotis, A.; Tsiknakis, M. Review on Psychological Stress Detection Using Biosignals. IEEE Transactions on Affective Computing 2022, 13, 440–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Hoai Nguyen, M.; Blitz, P.; French, B.; Fisk, S.; De la Torre, F.; Smailagic, A.; Siewiorek, D.; al’ Absi, M.; Ertin, E.; et al. , Personalized Stress Detection from Physiological Measurements; 2010.

- Sandulescu, V.; Andrews, S.; Ellis, D.; Bellotto, N.; Mozos, O.M. Stress Detection Using Wearable Physiological Sensors. In Artificial Computation in Biology and Medicine; Ferrández Vicente, J.M.; Álvarez-Sánchez, J.R.; De La Paz López, F.; Toledo-Moreo, F.J.; Adeli, H., Eds.; Springer International Publishing, 2015; Vol. 9107, pp. 526–532.

- Wu, M.; Cao, H.; Nguyen, H.L.; Surmacz, K.; Hargrove, C. Modeling perceived stress via HRV and accelerometer sensor streams. Conf. Proc. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Soc. 2015, 2015, 1625–1628. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Q.; Nwe, T.L.; Guan, C. Cluster-Based Analysis for Personalized Stress Evaluation Using Physiological Signals. IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics 2015, 19, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikhia, B.; Stavropoulos, T.; Andreadis, S.; Karvonen, N.; Kompatsiaris, I.; Sävenstedt, S.; Pijl, M.; Melander, C. Utilizing a Wristband Sensor to Measure the Stress Level for People with Dementia. Sensors 2016, 16, 1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mozos, O.M.; Sandulescu, V.; Andrews, S.; Ellis, D.; Bellotto, N.; Dobrescu, R.; Ferrandez, J.M. Stress Detection Using Wearable Physiological and Sociometric Sensors. Int. J. Neural Syst. 2017, 27, 1650041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akmandor, A.O.; Jha, N.K. Keep the Stress Away with SoDA: Stress Detection and Alleviation System. IEEE Transactions on Multi-Scale Computing Systems 2017, 3, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, A.; Ozcelebi, T.; Lukkien, J.; Van Erp, J.B.F.; Trajanovski, S. Model Adaptation and Personalization for Physiological Stress Detection. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 5th International Conference on Data Science and Advanced Analytics (DSAA). IEEE; 2018; pp. 209–216. [Google Scholar]

- Taamneh, S.; Tsiamyrtzis, P.; Dcosta, M.; Buddharaju, P.; Khatri, A.; Manser, M.; Ferris, T.; Wunderlich, R.; Pavlidis, I. A multimodal dataset for various forms of distracted driving. Sci Data 2017, 4, 170110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Can, Y.S.; Chalabianloo, N.; Ekiz, D.; Ersoy, C. Continuous Stress Detection Using Wearable Sensors in Real Life: Algorithmic Programming Contest Case Study. Sensors 2019, 19, 1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Can, Y.S.; Chalabianloo, N.; Ekiz, D.; Fernandez-Alvarez, J.; Riva, G.; Ersoy, C. Personal Stress-Level Clustering and Decision-Level Smoothing to Enhance the Performance of Ambulatory Stress Detection With Smartwatches. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 38146–38163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indikawati, F.I.; Winiarti, S. Stress Detection from Multimodal Wearable Sensor Data. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering 2020, 771, 012028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, P.; Reiss, A.; Duerichen, R.; Marberger, C.; Van Laerhoven, K. Introducing WESAD, a Multimodal Dataset for Wearable Stress and Affect Detection. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 20th ACM International Conference on Multimodal Interaction, New York, NY, USA, 2018; ICMI ’18, pp. 400–408.

- Tervonen, J.; Puttonen, S.; Sillanpää, M.J.; Hopsu, L.; Homorodi, Z.; Keränen, J.; Pajukanta, J.; Tolonen, A.; Lämsä, A.; Mäntyjärvi, J. Personalized mental stress detection with self-organizing map: From laboratory to the field. Comput. Biol. Med. 2020, 124, 103935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Sano, A. Early versus Late Modality Fusion of Deep Wearable Sensor Features for Personalized Prediction of Tomorrow’s Mood, Health, and Stress. Conf. Proc. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Soc. 2020, 2020, 5896–5899. [Google Scholar]

- Sano, A.; Taylor, S.; McHill, A.W.; Phillips, A.J.; Barger, L.K.; Klerman, E.; Picard, R. Identifying Objective Physiological Markers and Modifiable Behaviors for Self-Reported Stress and Mental Health Status Using Wearable Sensors and Mobile Phones: Observational Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2018, 20, e210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Sano, A. Extraction and Interpretation of Deep Autoencoder-based Temporal Features from Wearables for Forecasting Personalized Mood, Health, and Stress. Proc. ACM Interact. Mob. Wearable Ubiquitous Technol. 2020, 4, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipresso, P.; Serino, S.; Borghesi, F.; Tartarisco, G.; Riva, G.; Pioggia, G.; Gaggioli, A. Continuous measurement of stress levels in naturalistic settings using heart rate variability: An experience-sampling study driving a machine learning approach. ACTA IMEKO 2021, 10, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourmohammadi, S.; Maleki, A. Continuous mental stress level assessment using electrocardiogram and electromyogram signals. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2021, 68, 102694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tazarv, A.; Labbaf, S.; Reich, S.M.; Dutt, N.; Rahmani, A.M.; Levorato, M. Personalized Stress Monitoring using Wearable Sensors in Everyday Settings. In Proceedings of the 2021 43rd Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC). IEEE, 2021, pp. 7332–7335.

- Yu, H.; Vaessen, T.; Myin-Germeys, I.; Sano, A. Modality Fusion Network and Personalized Attention in Momentary Stress Detection in the Wild. In Proceedings of the 2021 9th International Conference on Affective Computing and Intelligent Interaction (ACII), Nara, Japan; 2021; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Lisowska, A.; Wilk, S.; Peleg, M. Catching patient’s attention at the right time to help them undergo behavioural change: Stress classification experiment from blood volume pulse. In Artificial Intelligence in Medicine; Lecture notes in computer science, Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021; pp. 72–82. [Google Scholar]

- Fauzi, M.A.; Yang, B.; Blobel, B. Comparative Analysis between Individual, Centralized, and Federated Learning for Smartwatch Based Stress Detection. Journal of Personalized Medicine 2022, 12, 1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Lee, H.; Toshnazarov, K.E.; Noh, Y.; Lee, U. StressBal: Personalized Just-in-time Stress Intervention with Wearable and Phone Sensing. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2022 ACM International Joint Conference on Pervasive and Ubiquitous Computing, Cambridge United Kingdom, 2022; pp. 41–43.

- Iqbal, T.; Simpkin, A.J.; Roshan, D.; Glynn, N.; Killilea, J.; Walsh, J.; Molloy, G.; Ganly, S.; Ryman, H.; Coen, E.; et al. Stress Monitoring Using Wearable Sensors: A Pilot Study and Stress-Predict Dataset. Sensors 2022, 22, 8135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazeli, S.; Levine, L.; Beikzadeh, M.; Mirzasoleiman, B.; Zadeh, B.; Peris, T.; Sarrafzadeh, M. Passive Monitoring of Physiological Precursors of Stress Leveraging Smartwatch Data. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM). IEEE; 2022; pp. 2893–2899. [Google Scholar]

- Sah, R.K.; Cleveland, M.J.; Habibi, A.; Ghasemzadeh, H. Stressalyzer: Convolutional Neural Network Framework for Personalized Stress Classification. In Proceedings of the 2022 44th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC), Glasgow, Scotland, United Kingdom, 2022; pp. 4658–4663.

- Hasanpoor, Y.; Tarvirdizadeh, B.; Alipour, K.; Ghamari, M. Stress Assessment with Convolutional Neural Network Using PPG Signals. In Proceedings of the 2022 10th RSI International Conference on Robotics and Mechatronics (ICRoM). IEEE; 2022; pp. 472–477. [Google Scholar]

- Eom, S.; Eom, S.; Washington, P. SIM-CNN: Self-Supervised Individualized Multimodal Learning for Stress Prediction on Nurses Using Biosignals. Technical report, Health Informatics, 2023.

- Hosseini, S.; Gottumukkala, R.; Katragadda, S.; Bhupatiraju, R.T.; Ashkar, Z.; Borst, C.W.; Cochran, K. A multimodal sensor dataset for continuous stress detection of nurses in a hospital. Sci Data 2022, 9, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finseth, T.T.; Dorneich, M.C.; Vardeman, S.; Keren, N.; Franke, W.D. Real-Time Personalized Physiologically Based Stress Detection for Hazardous Operations. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 25431–25454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, T.; Washington, P. Personalization of Stress Mobile Sensing using Self-Supervised Learning 2023. arXiv:cs.LG/2308.02731].

- Li, J.; Washington, P. A Comparison of Personalized and Generalized Approaches to Emotion Recognition Using Consumer Wearable Devices: Machine Learning Study 2023. arXiv:cs.LG/2308.14245].

- Moser, M.K.; Resch, B.; Ehrhart, M. An Individual-Oriented Algorithm for Stress Detection in Wearable Sensor Measurements. IEEE Sens. J. 2023, 23, 22845–22856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriakou, K.; Resch, B.; Sagl, G.; Petutschnig, A.; Werner, C.; Niederseer, D.; Liedlgruber, M.; Wilhelm, F.; Osborne, T.; Pykett, J. Detecting Moments of Stress from Measurements of Wearable Physiological Sensors. Sensors 2019, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tazarv, A.; Labbaf, S.; Rahmani, A.; Dutt, N.; Levorato, M. Active Reinforcement Learning for Personalized Stress Monitoring in Everyday Settings. 2023 IEEE/ACM Conference on Connected Health: Applications, Systems and Engineering Technologies (CHASE), 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Tutunji, R.; Kogias, N.; Kapteijns, B.; Krentz, M.; Krause, F.; Vassena, E.; Hermans, E.J. Detecting Prolonged Stress in Real Life Using Wearable Biosensors and Ecological Momentary Assessments: Naturalistic Experimental Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e39995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enderle, J.; Bronzino, J. Introduction to Biomedical Engineering; Academic Press, 2012.

- Swapna, M.; Viswanadhula, U.M.; Aluvalu, R.; Vardharajan, V.; Kotecha, K. Bio-Signals in Medical Applications and Challenges Using Artificial Intelligence. Journal of Sensor and Actuator Networks 2022, 11, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semmlow, J. Circuits, Signals, and Systems for Bioengineers: A MATLAB-Based Introduction; Academic Press, 2017.

- Weber, J.; Angerer, P.; Apolinário-Hagen, J. Physiological reactions to acute stressors and subjective stress during daily life: A systematic review on ecological momentary assessment (EMA) studies. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0271996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noteboom, J.T.; Barnholt, K.R.; Enoka, R.M. Activation of the arousal response and impairment of performance increase with anxiety and stressor intensity. J. Appl. Physiol. 2001, 91, 2093–2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sevil, M.; Rashid, M.; Askari, M.R.; Maloney, Z.; Hajizadeh, I.; Cinar, A. Detection and Characterization of Physical Activity and Psychological Stress from Wristband Data. Signals Commun. Technol. 2020, 1, 188–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevil, M.; Rashid, M.; Hajizadeh, I.; Askari, M.R.; Hobbs, N.; Brandt, R.; Park, M.; Quinn, L.; Cinar, A. Discrimination of simultaneous psychological and physical stressors using wristband biosignals. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2021, 199, 105898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brain Mapping: An Encyclopedic Reference; Academic Press, 2015.

- Park, J.; Seok, H.S.; Kim, S.S.; Shin, H. Photoplethysmogram Analysis and Applications: An Integrative Review. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 808451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyton, A.C.; Hall, J.E. Human Physiology and Mechanisms of Disease; Saunders, 1997.

- Herborn, K.A.; Graves, J.L.; Jerem, P.; Evans, N.P.; Nager, R.; McCafferty, D.J.; McKeegan, D.E.F. Skin temperature reveals the intensity of acute stress. Physiol. Behav. 2015, 152, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atterhög, J.H.; Eliasson, K.; Hjemdahl, P. Sympathoadrenal and cardiovascular responses to mental stress, isometric handgrip, and cold pressor test in asymptomatic young men with primary T wave abnormalities in the electrocardiogram. Br. Heart J. 1981, 46, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhide, A.; Durgaprasad, R.; Kasala, L.; Velam, V.; Hulikal, N. Electrocardiographic changes during acute mental stress. Int. J. Med. Sci. Public Health 2016, 5, 835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, M.L.; Butler, L.K. Endocrinology of Stress. Int. J. Comp. Psychol. 2007, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abelson, J.L.; Khan, S.; Giardino, N. HPA axis, respiration and the airways in stress–a review in search of intersections. Biol. Psychol. 2010, 84, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.J.; Webb, H.E.; Zourdos, M.C.; Acevedo, E.O. Cardiovascular reactivity, stress, and physical activity. Front. Physiol. 2013, 4, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britton, J.W.; Frey, L.C.; Hopp, J.L.; Korb, P.; Koubeissi, M.Z.; Lievens, W.E.; Pestana-Knight, E.M.; St. Louis, E.K. Electroencephalography (EEG): An Introductory Text and Atlas of Normal and Abnormal Findings in Adults, Children, and Infants; American Epilepsy Society: Chicago.

- Arthur, A.Z. Stress as a state of anticipatory vigilance. Percept. Mot. Skills 1987, 64, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwen, B.S.; Gianaros, P.J. Central role of the brain in stress and adaptation: links to socioeconomic status, health, and disease. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2010, 1186, 190–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Geem, Z.W.; Han, G.T. Hyperparameter Optimization Method Based on Harmony Search Algorithm to Improve Performance of 1D CNN Human Respiration Pattern Recognition System. Sensors 2020, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polat.; Kemal.; Öztürk.; Şaban. Diagnostic biomedical signal and image processing applications with deep learning methods; Intelligent Data-Centric Systems, Academic Press: San Diego, CA, 2023.

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30.

- Zeng, Z.; Kaur, R.; Siddagangappa, S.; Rahimi, S.; Balch, T.; Veloso, M. Financial Time Series Forecasting using CNN and Transformer 2023. arXiv:cs.LG/2304.04912].

- Benchekroun, M.; Istrate, D.; Zalc, V.; Lenne, D. Mmsd: A multi-modal dataset for real-time, continuous stress detection from physiological signals. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 15th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies. SCITEPRESS - Science and Technology Publications, 2022.

- Coşkun, B.; Ay, S.; Erol Barkana, D.; Bostanci, H.; Uzun, İ.; Oktay, A.B.; Tuncel, B.; Tarakci, D. A physiological signal database of children with different special needs for stress recognition. Sci Data 2023, 10, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koldijk, S.; Sappelli, M.; Verberne, S.; Neerincx, M.A.; Kraaij, W. The SWELL Knowledge Work Dataset for Stress and User Modeling Research. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Multimodal Interaction, New York, NY, USA, 2014; ICMI ’14, pp. 291–298.

- Haouij, N.E.; Poggi, J.M.; Sevestre-Ghalila, S.; Ghozi, R.; Jaïdane, M. AffectiveROAD system and database to assess driver’s attention. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Symposium on Applied Computing, New York, NY, USA, 2018; SAC ’18, pp. 800–803.

- Markova, V.; Ganchev, T.; Kalinkov, K. CLAS: A Database for Cognitive Load, Affect and Stress Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Biomedical Innovations and Applications (BIA). IEEE; 2019; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Parent, M.; Albuquerque, I.; Tiwari, A.; Cassani, R.; Gagnon, J.F.; Lafond, D.; Tremblay, S.; Falk, T.H. PASS: A Multimodal Database of Physical Activity and Stress for Mobile Passive Body/ Brain-Computer Interface Research. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 542934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meziati, R.; Benezeth, Y.; De Oliveira, P.; Chappé, J.; Yang, F. UBFC-Phys, 2021.

- Chen, W.; Zheng, S.; Sun, X. Introducing MDPSD, a Multimodal Dataset for Psychological Stress Detection. In Big Data; Communications in computer and information science, Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2021; pp. 59–82. [Google Scholar]

- SMILE (momentary stress labels with electrocardiogram, skin conductance, and acceleration data). https://compwell.rice.edu/workshops/embc2022/challenge, 2022. Accessed: 2023-10-24.

- Hosseini, M.; Sohrab, F.; Gottumukkala, R.; Bhupatiraju, R.T.; Katragadda, S.; Raitoharju, J.; Iosifidis, A.; Gabbouj, M. EmpathicSchool: A multimodal dataset for real-time facial expressions and physiological data analysis under different stress conditions 2022. arXiv:cs.MM/2209.13542].

- Hart, S.G.; Staveland, L.E. Development of NASA-TLX (Task Load Index): Results of Empirical and Theoretical Research. In Advances in Psychology; Hancock, P.A.; Meshkati, N., Eds.; North-Holland, 1988; Vol. 52, pp. 139–183.

- Spielberger, C.D.; Gorsuch, R.L.; Lushene, R.E. STAI Manual for the State-trait Anxiety Inventory (“Self-evaluation Questionnaire”); Consulting Psychologists Press, 1970.

- Bradley, M.M.; Lang, P.J. Measuring emotion: the Self-Assessment Manikin and the Semantic Differential. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 1994, 25, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moskowitz, D.S.; Young, S.N. Ecological momentary assessment: what it is and why it is a method of the future in clinical psychopharmacology. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2006, 31, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- EmbracePlus. https://www.empatica.com/en-eu/embraceplus/. Accessed: 2023-11-7.

- Samsung Galaxy Watch 4. https://www.samsung.com/it/watches/galaxy-watch/galaxy-watch4-black-bluetooth-sm-r860nzkaitv/buy/, 2021. Accessed: 2023-11-7.

- Samsung Galaxy Watch 5. https://www.samsung.com/it/watches/galaxy-watch/galaxy-watch5-40mm-graphite-bluetooth-sm-r900nzaaitv/, 2022. Accessed: 2023-11-7.

- Samsung Galaxy Watch 6. https://www.samsung.com/it/watches/galaxy-watch/galaxy-watch6-bluetooth-40mm-gold-bluetooth-sm-r930nzeaitv/, 2023. Accessed: 2023-11-7.

- Polar OH1+. https://www.polar.com/it/sensors/oh1-optical-heart-rate-sensor. Accessed: 2023-11-7.

- Polar H10. https://www.polar.com/it/sensors/h10-heart-rate-sensor. Accessed: 2023-11-7.

- Polar Verity Sense. https://www.polar.com/it/products/accessories/polar-verity-sense. Accessed: 2023-11-7.

- Williams, G. Bangle.Js - hackable smart watch. https://banglejs.com/. Accessed: 2023-11-7.

- Shimmer3 ECG unit. https://shimmersensing.com/product/shimmer3-ecg-unit-2/. Accessed: 2023-11-7.

- Shimmer3 GSR+ unit. https://shimmersensing.com/product/shimmer3-gsr-unit/. Accessed: 2023-11-7.

- CardioBAN Kit. https://www.pluxbiosignals.com/products/cardioban. Accessed: 2023-11-7.

- MuscleBAN Kit. https://www.pluxbiosignals.com/products/muscleban-kit. Accessed: 2023-11-7.

- Montgomery, S.M.; Nair, N.; Chen, P.; Dikker, S. Introducing EmotiBit, an open-source multi-modal sensor for measuring research-grade physiological signals. Science Talks 2023, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BrainBit Callibri. https://store.brainbit.com/collections/hardware/products/callibri-sdk. Accessed: 2023-12-5.

- BrainBit Headband. https://store.brainbit.com/collections/hardware/products/brainbit-sdk. Accessed: 2023-12-5.

- Muse S (gen 2). https://choosemuse.com/products/muse-s-gen-2. Accessed: 2023-12-5.

- Smyth, J.M.; Zawadzki, M.J.; Marcusson-Clavertz, D.; Scott, S.B.; Johnson, J.A.; Kim, J.; Toledo, M.J.; Stawski, R.S.; Sliwinski, M.J.; Almeida, D.M. Computing Components of Everyday Stress Responses: Exploring Conceptual Challenges and New Opportunities. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2023, 18, 110–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siirtola, P.; Peltonen, E.; Koskimäki, H.; Mönttinen, H.; Röning, J.; Pirttikangas, S. Wrist-worn Wearable Sensors to Understand Insides of the Human Body: Data Quality and Quantity. In Proceedings of the The 5th ACM Workshop on Wearable Systems and Applications, New York, NY, USA, 2019; WearSys ’19; pp. 17–21. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, J.Y.; Chao, Z.; Bertozzi, A.L.; Wang, W.; Young, S.D.; Needell, D. Learning to Predict Human Stress Level with Incomplete Sensor Data from Wearable Devices. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 28th ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management, New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 192773–2781.

- Bent, B.; Goldstein, B.A.; Kibbe, W.A.; Dunn, J.P. Investigating sources of inaccuracy in wearable optical heart rate sensors. NPJ Digit Med 2020, 3, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thammasan, N.; Stuldreher, I.V.; Schreuders, E.; Giletta, M.; Brouwer, A.M. A Usability Study of Physiological Measurement in School Using Wearable Sensors. Sensors 2020, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iranfar, A.; Arza, A.; Atienza, D. ReLearn: A Robust Machine Learning Framework in Presence of Missing Data for Multimodal Stress Detection from Physiological Signals. Conf. Proc. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Soc. 2021, 2021, 535–541. [Google Scholar]

- Tazarv, A.; Labbaf, S.; Rahmani, A.M.; Dutt, N.; Levorato, M. Data Collection and Labeling of Real-Time IoT-Enabled Bio-Signals in Everyday Settings for Mental Health Improvement. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Conference on Information Technology for Social Good, New York, NY, USA, 2021; GoodIT ’21, pp. 186–191.

- Booth, B.M.; Vrzakova, H.; Mattingly, S.M.; Martinez, G.J.; Faust, L.; D’Mello, S.K. Toward Robust Stress Prediction in the Age of Wearables: Modeling Perceived Stress in a Longitudinal Study With Information Workers. IEEE Transactions on Affective Computing 2022, 13, 2201–2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalabianloo, N.; Can, Y.S.; Umair, M.; Sas, C.; Ersoy, C. Application level performance evaluation of wearable devices for stress classification with explainable AI. Pervasive Mob. Comput. 2022, 87, 101703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Can, Y.S. Stressed or just running? Differentiation of mental stress and physical activityby using machine learning. Turkish Journal of Electrical Engineering and Computer Sciences 2022, 30, 312–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, D.C.; Zhang, M.; Schueller, S.M. Personal Sensing: Understanding Mental Health Using Ubiquitous Sensors and Machine Learning. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2017, 13, 23–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, P.; Petitclerc, A.; Moskowitz, J.; Tandon, D.; Zhang, Y.; MacNeill, L.A.; Alshurafa, N.; Krogh-Jespersen, S.; Hamil, J.L.; Nili, A.; et al. Feasibility of Passive ECG Bio-sensing and EMA Emotion Reporting Technologies and Acceptability of Just-in-Time Content in a Well-being Intervention, Considerations for Scalability and Improved Uptake. Affect Sci 2022, 3, 849–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Cañete, F.J.; Casilari, E. A Feasibility Study of the Use of Smartwatches in Wearable Fall Detection Systems. Sensors 2021, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiffman, S.; Stone, A.A.; Hufford, M.R. Ecological momentary assessment. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2008, 4, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fradkov, A.L. Early History of Machine Learning. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2020, 53, 1385–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | We selected 2010 in accordance with the history of artificial intelligence [122], which marks its exponential growth during that period. |

| 2 | The term non-invasive refers to a device that does not cause physical discomfort to the subject. |

| Study | Year | Sample (Gender) |

Type | Signals | Stressor | Task Type | Ground Truth | Approach (Model) |

Performance (Metric) |

Dataset |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [17] | 2010 | 22 (N/A) |

SCE | ECG EDA SKT RSP |

Public Speaking Stressor Mental Arithmetic Stressors Cold Pressor Stressor |

Classification: Binary |

EMAs | ML (RBF SVM) |

68% (Precision) |

N/A |

| [18] | 2015 | 5 (N/A) |

SCE | PPG EDA |

Trier Social Stress Test | Classification: Binary |

STAI | ML (SVM) |

78.98% (Accuracy) |

N/A |

| [19] | 2015 | 8 (N/A) |

LIFE | PPG ACC |

Real-life | Classification: Binary |

EMAs | ML (REPTree) |

85.7% (Accuracy) |

N/A |

| [20] | 2015 | 44 (44M, 0F) |

LAB | PPG ECG EDA EEG EMG |

Go/No-go Visual Reaction Stroop Color Test Fast Counting PASAT speed run Visual Forward Digit Span N-back |

Classification: Binary |

STAI | ML (K-Means+GRNN) |

85.2% (Accuracy) |

N/A |

| [21] | 2016 | 6 (N/A) |

LIFE | EDA | Real-life | Classification: Binary |

Clinical Notes | STAT (Threshold-based Classifier) |

60.55% (Accuracy) |

N/A |

| [22] | 2017 | 18 (N/A) |

LAB | PPG EDA MIC ACC |

Trier Social Stress Test | Classification: Binary |

STAI | ML (AdaBoost) |

94% (Accuracy) |

N/A |

| [23] | 2017 | 33 (25M, 8F) |

LAB | PPG ECG EDA RSP NIBP |

Memory game Fly sound Image stimuli Cold Pressor Stressor |

Classification: Binary |

Experimental condition |

ML (kNN) |

95.8% (Accuracy) |

N/A |

| [24] | 2018 | 40 (N/A) |

SCE | ECG EDA EMG |

Driving Mathematical Questions Analytical Questions |

Classification: Binary |

Experimental condition |

DL (2*TCN [Shared] +1 TCN [Subject]) |

0.918 (AUROC) |

[25] |

| [26] | 2019 | 21 (18M, 3F) |

SCE | PPG EDA ACC |

Contest | Classification: 3-level |

NASA-TLX Free Stress Scale (0-100) |

ML (RF/MLP) |

97.92% (Accuracy EMP) 91.54% (Accuracy SAM) |

N/A |

| [27] | 2020 | 32 (22M, 10F) |

SCE | PPG EDA SKT ACC |

Exam | Classification: Binary 4-level |

NASA-TLX Experimental condition |

ML (RF) |

Binary: 92.5% (Accuracy) 4-level: 85.63% (Accuracy) |

N/A |

| [28] | 2020 | 15 (12M, 3F) |

LAB | PPG EDA SKT |

Trier Social Stress Test | Classification: 4-level |

PANAS STAI SAM SSSQ |

ML (RF) |

96.68% (Accuracy) |

[29] |

| [30] | 2020 | 73 (28M, 45F) |

LIFE | PPG ACC |

Real-life | Classification: Binary |

EMAs | ML (SOM) |

54.5% (Accuracy) |

N/A |

| [31] | 2020 | 255 (N/A) |

LIFE | EDA SKT ACC |

Real-life | Regression: Stress level |

EMAs | DL (LC+LSTM DAE) |

16.5 (MAE) |

[32] |

| [33] | 2020 | 255 (N/A) |

LIFE | EDA SKT ACC |

Real-life | Regression: Stress level |

EMAs | DL (LC+LSTM DAE) |

15.0 (MAE) |

[32] |

| [34] | 2021 | 15 (8M, 7F) |

LIFE | ECG | Real-life | Classification: Binary |

EMAs | ML (SOM+Fuzzy Classifier) |

95.7% (Precision) |

N/A |

| [35] | 2021 | 34 (11M, 23F) |

LAB | ECG EMG |

Stroop Color-Word Test Math Test |

Classification: 3-level |

STAI Free Stress Scale (1–5) |

ML (Fuzzy Clustering Membership based Classifier) |

75.6% (Accuracy) |

N/A |

| [36] | 2021 | 14 (N/A) |

LIFE | PPG ACC GYR |

Real-life | Classification: Binary |

EMAs | ML (RF) |

76% (F1 score) |

N/A |

| [37] | 2021 | 41 (5M, 36F) |

LIFE | ECG EDA |

Real-life | Classification: Binary |

EMAs | DL (MFN with SABs) |

77.4% (F1 score) |

N/A |

| [38] | 2021 | 15 (12M, 3F) |

LAB | PPG | Trier Social Stress Test | Classification: Binary 3-level |

PANAS STAI SAM SSSQ |

DL (1D-CNN) |

Binary: 82.2% (F1 score) 3-level: 70.5% (F1 score) |

[29] |

| [39] | 2022 | 15 (12M, 3F) |

LAB | PPG EDA SKT ACC |

Trier Social Stress Test | Classification: Binary |

PANAS STAI SAM SSSQ |

ML (LR) |

99.98% (Accuracy) |

[29] |

| [40] | 2022 | N/A (N/A) |

LIFE | PPG ACC |

Real-life | Classification: Binary |

EMAs | ML (N/A) |

N/A | N/A |

| [41] | 2022 | 35 (10M, 25F) |

LAB | PPG | Stroop Color Test Trier Social Stress Test Hyperventilation |

Classification: Binary |

STAI PSS |

STAT (Adaptive Reference Range based Classifier) |

68.63% (Accuracy) |

[41] |

| [42] | 2022 | 14 (N/A) |

LIFE | PPG | Real-life | Classification: 4-level |

EMAs | DL (LSTM) |

64.5% (Accuracy) |

N/A |

| [43] | 2022 | 15 (12M, 3F) |

LAB | EDA | Trier Social Stress Test | Classification: Binary 3-level |

PANAS STAI SAM SSSQ |

DL (2*1D-CNN+FCN) |

Binary: 90% (Accuracy) 3-level: 70% (Accuracy) |

[29] |

| [44] | 2022 | 15 (12M, 3F) |

LAB | PPG | Trier Social Stress Test | Classification: Binary 5-level |

PANAS STAI SAM SSSQ |

DL (1D-CNN) |

Binary: 96.7% (Accuracy) 5-level: 80.6% (Accuracy) |

[29] |

| [45] | 2023 | 15 (0M, 15F) |

LIFE | PPG EDA SKT ACC |

Real-life | Classification: Binary |

EMAs | DL (CNN Architecture with SSL) |

79.65% (Accuracy) |

[46] |

| [47] | 2023 | 41 (34M, 7F) |

LAB | ECG EDA RSP NIBP |

Fire Response Task in VR N-back |

Classification: Binary |

Free Stress Scale (0–100) |

ML (RF) |

82% (Accuracy VR) 98% (Accuracy N-back) |

N/A |

| [48]* | 2023 | 15 (12M, 3F) |

LAB | EDA | Trier Social Stress Test | Regression: Items in scales |

PANAS STAI SAM SSSQ |

DL (CNN Architecture with SSL) |

N/A | [29] |

| [49]* | 2023 | 15 (12M, 3F) |

LAB | ECG EDA EMG SKT RSP ACC |

Trier Social Stress Test | Classification: 3-level |

PANAS STAI SAM SSSQ |

DL (1D CNN+MLP) |

95.06% (Accuracy) |

[29] |

| [50] | 2023 | 16 (8M, 8F) |

LAB | EDA SKT |

Acoustic Stressors | Classification: Binary |

Experimental condition |

STAT (MOS Algorithm [51]) |

92.74% (Accuracy) |

N/A |

| [52] | 2023 | 20 (13M, 7F) |

LIFE | PPG ACC GYR |

Real-life | Classification: Binary |

EMAs | ML (RF) |

40-45% (Recall) |

N/A |

| [53] | 2023 | 83 (51M, 32F) |

LIFE | PPG EDA SKT ACC |

Real-life | Classification: Binary |

EMAs | ML (RF) |

66.55% (Accuracy) |

N/A |

| Signal | Description | Connection to stress | N |

|---|---|---|---|

| EDA | Electrodermal Activity (EDA), or galvanic skin response (GSR), is a biosignal that measures skin conductance, reflecting sweat gland activity. | Activation of the sympathetic nervous system during stress stimulates eccrine sweat glands through the release of neurotransmitters (especially norepinephrine) [61], leading to sweat production and changes in skin conductance. | 21 |

| PPG | Photoplethysmogram (PPG) is a biosignal that records changes in the volume of blood flow in arteries, capillaries, and any other tissue following each contraction and relaxation of the heart | Stress hormones such as cortisol and adrenaline, released during stressful situations, activate the sympathetic nervous system (SNS). This activation results in an increased heart rate, stronger cardiac contractions, and vasoconstriction, especially in the extremities [62], affecting blood flow and PPG readings. | 19 |

| SKT | Peripheral Skin Temperature (SKT) is a biosignal that measures the temperature of the skin in the peripheral area | Skin temperature is closely linked to blood flow and it is affected by peripheral vasoconstriction induced by stress hormones like cortisol and adrenaline [63]. In acute stress, a slight decrease in temperature, attributed to vasoconstriction, is expected [64]. | 10 |

| ECG | Electrocardiogram (ECG) is a biosignal that records the electrical activity of the heart on the surface of the body during the cardiac cycle. | Sympathetic nervous system activity primarily involves an increase in heart rate during stress [65]. Electrocardiogram (ECG), as PPG, provides insights into these changes, including alterations in PR interval and QRS duration [66]. | 9 |

| EMG | Electromyogram (EMG) is a biosignal that records the electrical activity produced by the muscle when it contracts. | Cortisol and adrenaline, released during stress, induce a phenomenon of muscular vasodilation, resulting in muscle tension that prepares the body for action or damage minimization [67]. | 4 |

| RSP | Respiration (RSP) is a biosignal that provides information about the patterns of inhalation and exhalation in an individual. | During stressful situations, as a component of the fight-or-flight response, the body readies itself for either escape or confrontation by dilating the airways and altering respiration patterns. These responses, as seen for other biosignals, are directed by the influence of the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis [68]. | 3 |

| NIBP | Non-Invasive Blood Pressure (NIBP) is a biosignal that measures blood pressure without the requirement for invasive procedures. | Stress impacts blood pressure patterns through the activation of the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, leading to pressure fluctuations resulting from increased heart rate and blood vessel constriction [69]. | 2 |

| EEG | Electroencephalogram (EEG) is a biosignal that measures the electrical activity of the brain, specifically detecting fluctuations in voltage resulting from ionic current flows within the neurons of the brain [70]. | Under stress conditions, the brain focuses concentration and increases alertness to enhance the body’s chances of surviving the situation [71,72]. These processes are reflected in an increase in activity and a decrease in activity. | 1 |

| Filter | Definition | Signal | Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lowpass | A lowpass filter is a filter which allows signals with frequencies below a specified cutoff frequency to pass through, attenuating higher frequencies. | EDA ECG SKT |

[21,22,31,33,47,50] [34] [50] |

| Highpass | A highpass filter is a filter which permits signals with frequencies above a defined cutoff frequency to pass through while attenuating lower frequencies. | ECG EMG |

[23] [35] |

| Bandpass | A bandpass filter is a filter which selectively allows a specific range or "band" of frequencies to pass through, attenuating frequencies outside that range. | PPG ECG EDA EMG NIBP |

[22,36,44] [35] [53] [20] [47] |

| Notch | A notch filter is a filter which attenuates a specific narrow range of frequencies, effectively creating a "notch" in the frequency response. | ECG | [34,47] |

| Algorithm | Tree-based | Unsupervised+Supervised | N |

|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest | ✓ | ✗ | 7 |

| Self-Organizing Map based Classifier | ✗ | ✓ | 3 |

| Support Vector Machine | ✗ | ✗ | 2 |

| AdaBoost | ✓ | ✗ | 1 |

| Bagging (REPTree) | ✓ | ✗ | 1 |

| K-Nearest Neighbors | ✗ | ✗ | 1 |

| K-means + GRNN | ✗ | ✓ | 1 |

| Logistic Regression | ✗ | ✗ | 1 |

| Multilayer Perceptron | ✗ | ✗ | 1 |

| Signal | Feature | Definition and connection to stress | Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| PPG ECG |

HR | Avg. heart beats per minute; reflects the physiological stress response. Changes in heart rate may indicate the body’s adaptive response to stressors. | [17,19,20,30,35,36,42,52,53] |

| RR | Mean duration between R-peaks; reflects the autonomic nervous system interplay. Variations in RR intervals may signify the dynamic balance between sympathetic and parasympathetic branches. | [19,26,27,30,34,35,36,40,52] | |

| SDNN | Standard deviation of NN intervals; signifies the balance between sympathetic and parasympathetic influences. Changes in SDNN may indicate alterations in autonomic balance and responsiveness to stress. | [19,26,27,34,35,36,52] | |

| SDSD | Standard deviation of differences in NN intervals; indicates autonomic balance and responsiveness. Variations in SDSD may reflect the regulatory influence of both sympathetic and parasympathetic branches. | [19,26,27,35,36,52] | |

| RMSSD | Square root of mean squared differences in NN intervals; reflects parasympathetic activity, adaptability, and resilience to stress. Higher RMSSD values are associated with increased adaptability and resilience. | [19,26,27,30,34,35,36,40,47,52] | |

| pNN50 | Percentage of NN intervals differing by >50ms; indicator of parasympathetic activity and heart regulation. Monitoring changes in pNN50 provides insights into the dynamic regulation of the heart and its response to stressors. | [19,20,26,27,34,35,36,47,52] | |

| HRV | Variation in time intervals between heartbeats; serves as an indicator of the body’s adaptability to stress. Higher HRV is generally associated with a more flexible autonomic nervous system and better resilience to stressors. | [18,19,20,22,26,27,40,42,47] | |

| LF | Frequency activity (0.04 - 0.15Hz); often associated with sympathetic nervous system activity. LF variations may indicate the sympathetic influence on heart rate during stress. | [17,19,20,26,27,34,35] | |

| HF | Frequency activity (0.15 - 0.40Hz); primarily associated with parasympathetic nervous system activity and respiratory influences. HF variations may indicate changes in relaxation and parasympathetic dominance. | [19,20,26,27,34,35] | |

| LF/HF | Ratio of Low Frequency to High Frequency; considered a measure of the balance between sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system activity. A higher ratio may suggest increased sympathetic dominance, potentially indicating stress. | [19,20,26,27,34,35] | |

| EDA | SCL+SCR | Average of Combined Skin Conductance Level and Response; comprehensive indicator of arousal. The combined measure reflects both the tonic (baseline) and phasic (event-related) components, providing a holistic view of skin conductance dynamics related to stress. | [18,22] |

| SCL | Average Skin Conductance Level (SCL); reflects overall arousal level. SCL provides a baseline measure of sympathetic arousal, contributing to the assessment of stress levels. | [17,23,27,47,53] | |

| SCL SD | Standard Deviation of Skin Conductance Level; indicates variability in arousal. Variations in SCL may suggest fluctuations in the autonomic nervous system’s tonic arousal, possibly linked to stress reactivity. | [17,27] | |

| SCR | Average Skin Conductance Response (SCR); represents phasic changes in arousal. SCR reflects the rapid, event-related changes in skin conductance, offering insights into acute stress responses. | [20,47] | |

| SCR Peaks | Number of Peaks in Skin Conductance Response; indicates the frequency of arousal events. The count of SCR peaks provides a quantitative measure of how frequently the individual experiences heightened arousal. | [17,27,53] | |

| SCR Peaks Ampl | Amplitude of Peaks in Skin Conductance Response; reflects the intensity or strength of arousal events. The amplitude of SCR peaks may provide information on the magnitude of physiological responses during stress. | [17,23] | |

| RSP | BR | Breathing Rate; frequency of breath cycles may indicate stress. Changes in breathing rate can be associated with stress and the body’s effort to adapt to physiological demands. | [23,36,42,52] |

| RP | Respiratory Period; duration of one respiration cycle may relate to stress. The time taken for a complete respiratory cycle may be influenced by stress-related changes in breathing patterns. | [17,23] | |

| SKT | T | Avg. Skin Temperature; deviations from the baseline skin temperature may indicate stress. Abnormal skin temperature variations can be indicative of physiological responses to stressors. | [17,53] |

| T SD | Standard Deviation of Skin Temperature; variability in skin temperature may be associated with stress. Increased T SD may suggest fluctuations in autonomic responses linked to stress reactivity. | [17] | |

| T Slope | Slope of Skin Temperature Trends; changes in slope may reflect stress-related temperature dynamics. The rate of change in skin temperature may provide insights into adaptive responses to stressors. | [53] | |

| NIBP | SBP | Systolic Blood Pressure; elevated SBP may indicate increased stress or heightened physiological response. Systolic blood pressure is sensitive to acute stressors and reflects the force exerted on arterial walls during heartbeats. | [23,47] |

| DBP | Diastolic Blood Pressure; elevated DBP may suggest sustained stress or tension in the cardiovascular system. Diastolic blood pressure reflects the pressure in the arteries when the heart is at rest, and chronic stress may contribute to sustained elevation. | [23,47] | |

| EMG | EMG | Avg. value of muscle activity (EMG); increased activity may indicate stress. EMG captures muscle activity, and elevated average values may be associated with heightened muscle tension or stress responses. | [20,35] |

| EMG SD | Standard Deviation of muscle activity (EMG); variability in muscle activity may be associated with stress. Increased EMG SD suggests fluctuations in muscle tension, potentially reflecting stress-related changes in motor activity. | [20,35] | |

| EEG | Mean , , , | Mean values of different EEG frequency bands (, , , ); variations in EEG frequencies, such as increased beta and decreased alpha, may be associated with heightened mental activity or stress. Changes in delta and theta frequencies could also indicate alterations in relaxation or arousal states. | [20] |

| Dataset | Type | Sample | Biosignals (Device) | Stressor | Ground Truth | Pros and cons |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SWELL-KW [80] |

SCE | Size: 25 (17M, 8F) Age: 25 (3.25) |

ECG (Movi) EDA (Movi) FBT (Kinect) VS (Camera) |

Email interruptions Time pressure |

NASA-TLX RSME SAM Free Stress Scale ICI |

+ The stress condition mirrors what can be found in real life in a work environment - Potential age and gender bias - It focuses on a specific work-related stress condition |

| AffectiveROAD [81] |

SCE | Size: 10 (5M, 5F) Age: 29.9 (3.7) |

PPG (Empatica E4) EDA (Empatica E4) ACC (Empatica E4) ECG (BioHarness 3.0) SKT (BioHarness 3.0) RSP (BioHarness 3.0) VS (Camera) |

Real-life (Driving) |

External annotation: Stress Metric (Observer) Self assessment: Label validation |

+ The presence of video streams enables the development of sensorless models (with rPPG) - Very limited sample size - Potential age bias - It focuses on driving stress - The stress metric is only validated by the driver |

| WESAD [29] |

LAB | Size: 15 (12M, 3F) Age: 27.5 (2.4) |

ECG (RespiBAN) EDA (RespiBAN) EMG (RespiBAN) SKT (RespiBAN) RSP (RespiBAN) ACC (RespiBAN) PPG (Empatica E4) EDA (Empatica E4) SKT (Empatica E4) ACC (Empatica E4) |

Trier Social Stress Test | PANAS STAI SAM SSSQ |

+ Solid protocol and assessment of the participants’ state + It includes a wide range of signals from sensors placed both on the chest and the wrist - Potential gender and age bias - The Trier Social Stress Test elicits an extreme response that may not be comparable to those experienced by a non-clinical subject in real-life |

| CLAS [82] |

LAB | Size: 62 (45M, 17F) Age: Mostly 20-27 |

PPG (Shimmer 3 GSR+) ECG (Shimmer3 ECG) EDA (Shimmer 3 GSR+) ACC (Shimmer 3 GSR+) |

Video stimuli Math problems Logic problems Stroop Test |

Stimuli label Task performance |

+ Fairly big sample size - Potential age and gender bias - No clear details on the age distribution are provided - Researchers did not implement a solid strategy for ground-truth |

| PASS [83] |

LAB | Size: 48 (N/A) Age: N/A |

ECG (BioHarness 3.0) RSP (BioHarness 3.0) PPG (Empatica E4) EDA (Empatica E4) SKT (Empatica E4) EEG (Muse Headband) |

Gaming Physical activity (Cycling) |

BORG NASA-TLX (Variant) |

+ Combining mental stress and physical activity enables the development of models that account for movement artifacts and discriminate between physical and mental stress - Very limited information about the sample - ACC data not included in the dataset |

| UBFC-Phys [84] |

LAB | Size: 56 (10M, 46F) Age: 21.8 (3.11) |

PPG (Empatica E4) EDA (Empatica E4) VS (Camera) |

Trier Social Stress Test (Variant) |

CSAI | + The presence of video streams enables the development of sensorless models (with rPPG) - Potential gender and age bias - The Trier Social Stress Test elicits an extreme response that may not be comparable to those experienced by a non-clinical subject in real-life |

| MDPSD [85] |

LAB | Size: 120 (72M, 48F) Age: 22 (N/A) |

PPG (N/A) EDA (N/A) |

Stroop Test Rotation Letter Test Kraepelin Test |

Free Stress Scale | + Fairly large sample size - Potential age bias - Limited information regarding the devices used for data collection - All the stressors elicit an extreme response that may not be comparable to those experienced by a non-clinical subject in real-life |

| SMILE [86]** |

LIFE | Size: 45 (6M, 39F) Age: 24.5 (3.0) |

EDA (IMEC Chill Band) ACC (IMEC Chill Band) ECG (IMEC Health Patch) ACC (IMEC Health Patch) |

Real-life | EMAs | + Real-life stress assessment using EMAs - Potential gender and age bias |

| EmpathicSchool [87]* |

LAB | Size: 20 (N/A) Age: 25.3 (4.3) |

PPG (Empatica E4) EDA (Empatica E4) SKT (Empatica E4) IBI (Empatica E4) ACC (Empatica E4) VS (Camera) |

IQ test Presentation Stroop Color-Word Test |

NASA-TLX | + It contains a combination of stressors, encompassing both extreme conditions and real-life challenges - Relying solely on NASA-TLX as a ground truth measure may not provide a reliable identification of stress states |

| A multimodal sensor dataset for continuous stress detection of nurses in a hospital [46] |

LIFE | Size: 15 (0M, 15F) Age: 30-55 (range) |

PPG (Empatica E4) EDA (Empatica E4) SKT (Empatica E4) IBI (Empatica E4) ACC (Empatica E4) |

Real-life (Working at the hospital during COVID-19) |

Automated labeling using an algorithm trained on AffectiveROAD Post-shift survey for label confirmation, addition, and correction |

+ Intelligent automated pre-labeling approach using a pre-trained model + Researchers also investigated the factors causing stress - Very strong gender bias - Potential recall bias - The data pertain to a specific context (a hospital during a pandemic), which may differ significantly from real-life situations |

| MMSD [78] |

LAB | Size: 74 (36M, 38F) Age M: 35 (13) Age F: 33 (12.5) |

PPG (Shimmer) ECG (Shimmer) EDA (Shimmer) EMG (Shimmer) GYR (Shimmer) |

Stroop Color-Word Test Mental Arithmetic Test Computer Work |

STAI Cortisol Test |

+ Good sample size + Sample carefully controlled to be representative of the French population + Ground truth using both a validated scale and an objective gold standard technique (cortisol sample) - All the stressors elicit an extreme response that may not be comparable to those experienced by a non-clinical subject in real-life |

| Stress-Predict Dataset [41] |

LAB | Size: 35 (10M, 25F) Age: 32 (8.2) |

PPG (Empatica E4) | Stroop Color Test Trier Social Stress Test Hyperventilation |

STAI PSS |

+ Two validated scales for stress assessment provide a solid label - Potential gender bias - All the stressors elicit an extreme response that may not be comparable to those experienced by a non-clinical subject in real-life |

| AKTIVES [79] |

LAB | Size: 25 (10M, 15F) Age: 10.2 (1.27) Clinical sample |

PPG (Empatica E4) EDA (Empatica E4) SKT (Empatica E4) VS (Camera) |

Gaming | External annotation: 3 Observers |

+ Using 3 independent annotators mitigates the risk of mislabeling + Clinical sample and control group - Age-specific dataset - External annotation might not be accurate |

| Type of stressor | Stressor | Dataset(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Daily life | Gaming Computer work Real-life Driving Video/image stimuli Email interruptions Time pressure Public speaking |

[79,83] [78,87] [46,86] [81] [82] [80] [80] [87] |

| Artificial | Stroop Test Trier Social Stress Test Mental Arithmetic Test IQ Test (Variant) Kraepelin Test Rotation Letter Test Hyperventilation Provocation Test |

[41,78,82,85,87] [29,41,84] [78,82] [82,87] [85] [85] [41] |

| Device | Type | Sensors | Connectivity | Mobile | Release | Battery life | Cost (Q4 2023) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Empatica EmbracePlus [92] | Wrist | PPG, EDA, SKT, ACC, GYR | Bluetooth | Android, iOS | 2020 | 7 days | ∼2000 EUR |

| Samsung Galaxy Watch 4 [93] | Wrist | PPG, BIA, ACC, GYR | WiFi, Bluetooth | Android | 2021 | 40 hours | ∼140 EUR |

| Samsung Galaxy Watch 5 [94] | Wrist | PPG, BIA, ACC, GYR | WiFi, Bluetooth | Android | 2022 | 50 hours | ∼200 EUR |

| Samsung Galaxy Watch 6 [95] | Wrist | PPG, BIA, SKT, ACC, GYR | WiFi, Bluetooth | Android | 2023 | 40 hours | ∼300 EUR |

| Polar OH1+ [96] | Arm | PPG, ACC | Bluetooth | Android, iOS | 2019 | 12 hours | ∼60 EUR |

| Polar H10 [97] | Chest | ECG, ACC | Bluetooth | Android, iOS | 2017 | 400 hours | ∼90 EUR |

| Polar Verity Sense [98] | Arm | PPG, ACC, GYR | Bluetooth | Android, iOS | 2021 | 20 hours | ∼100 EUR |

| Bangle.js 2 [99] | Wrist | PPG, ACC | Bluetooth | Android | 2021 | 4 days | ∼90 EUR |

| Shimmer3 ExG [100] | Multi | ECG, EMG, ACC, GYR | Bluetooth | Android | 2018 | N/A | ∼550 EUR |

| Shimmer3 GSR+ [101] | Wrist | EDA, ACC, GYR | Bluetooth | Android | 2018 | N/A | ∼520 EUR |

| PLUX cardioBAN [102] | Chest | ECG, ACC | Bluetooth | Android | 2022 | N/A | ∼500 EUR |

| PLUX muscleBAN [103] | Arm | EMG, ACC | Bluetooth | Android | 2022 | N/A | ∼320 EUR |

| EmotiBit [104] | Arm | PPG, EDA, SKT, ACC, GYR | WiFi, Bluetooth | Android | 2022 | 4-8 hours | ∼230 EUR |

| BrainBit Callibri [105] | Multi | ECG, EMG, EEG, ACC | Bluetooth | Android, iOS | 2019 | 24 hours | ∼280 EUR |

| BrainBit Headband [106] | Head | EEG | Bluetooth | Android, iOS | 2019 | 12 hours | ∼460 EUR |

| Interaxon Muse S (Gen 2) [107] | Head | PPG, EEG | Bluetooth | Android, iOS | 2022 | 10 hours | ∼310 EUR |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).